#its something that leaves no space to argue or debate or bargain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My head hurts. my head hurts God IVE SAID THIS. I HAVE SAID THIS THEY CALLED ME CRAZY THEY LOCKED ME UP IN A DUNGEON Wilson loves amber in a way he can never love house solely because she is a version of house he can love and still sleep at night And surely house knows this too. i cannot imagine house volunteering to go through a life threatening brain surgery for any other one of wilsons girlfriends

The startling similarity between house and amber is explicitly acknowledged by countless characters in the show-- house and wilson Included.

so surely, house knows.

Surely house knows that this is all he can get The best he can get; the closest he can get to wilson's all devouring all consuming devotional unconditional unbridled love because though wilson loves house more than anything,

it is not unconditional. Because house could do anything and wilson would love him still, burningly so, but it is Not unconditional. Because the one thing keeping wilson from loving house, loving house loving him-- is the fact that he is not a woman.

It is a love wilson bars even house from-- a love wilson grants only to the women in his life. A love he can tell peers whose names he cant remember and family members whom he sees at annual gatherings about, a love that can be put up for display like the trophies that sit proudly at the shelf mounted on the walls of your doorway, lonely and collecting dust

House accepts amber because he can take comfort in the fact that if he were a woman, wilson could Love him. wilson Would Love Him. The existence of amber and wilson's relationship brings house the comfort of knowing that in another life,

in another life where house is not the man he is

is not a man with coarse hair that barbs and lines the juts of his maw

is not a man with a voice of granite and gravel and ebony lumber sanded rough and sharp and cruel

arms of wire weather-beaten vein and sinew

but instead a being of soft folds and curves that slope and flow,

wilson would love him. He'd want him. Wilson could love house

“why did wilson say he loved amber so soon” well… why wouldn’t he? it’s not her he really feels it for anyway. it’s house. he knows he loves house, and once he finds him in amber, why wouldn’t he be able to say it?

it’s implied that wilson is a bit of a flirt with the women at the hospital. but he jumps head first into that real, committed relationship with amber. he could only ever have felt so comfortable to the extent we saw him get with amber because he was projecting onto her what he wanted with house. their relationship wasn’t that great: i.e. water bed ep. but better than the others we see because she was the attainable version of what he wanted.

when she dies, we feel that grief because he did like amber as a person for sure, but he’s losing the only woman he actually felt he could feel something for. how do we know that it’s all still, at it’s root, love for house?

wilson goes off and hilson have their breakup and whatnot. but as soon as he and house come back together, what does he do? he invokes amber to pull a prank on house.

when they finally resolve that tension and go back to being “friends,” there’s such a sense of relief from both of them. we see a similar thing play out between them when house and cuddy break up. wilson marches into cuddy’s office and yells at her for leaving him (despite her valid reasons)—what does that tell us? he would never leave house. he accepts him for who he is and strives to make him better but doesn’t leave him (for good, anyway) when he fails. AKA, in the end, it’ll always be them. nothing could possibly tear them apart. and any relationship they attempt is doomed to fail because they’re… well. they’re each other’s foils. they’ve ruined each other for the rest of the world and they make sure to keep it that way because they wouldn’t want it any other way.

so, yeah, wilson said i love you too soon to amber. but, to be fair to him, it had been boiling up for about fifteen years.

#and its such a small thing but simultaneously is the nail in the fucking coffin#its something that leaves no space to argue or debate or bargain#It is something house can never overcome and it is why wilson cannot want him#its soooo sick wilsons comphet makes me so sick i need him Boiled#Mods kill this guy with rocks#house md#james wilson#amber volakis#gregory house#hilson#amber x wilson x house#wilson x amber#johan being crazy about yaoi md#house md meta#hilson meta#relationship analysis#character analysis#Also if u saw this post a couple of days ago#No. U didnt#No u didnt. u sound crazy#THEY CUT OFF MY FUCKING TAGS MAN CMON#I WAS BEING SILENCED!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

385 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝙼𝙴𝚃𝙰 𝟶𝟹: 𝙽𝙰𝙼𝚀𝙸.

@solhunt said: what does namqi mean to orin and what influence did he have on her life? @mercysought said: tell us how namqi and orin started their relationship and how was it for her to feel for the first time that she didn't want to leave

Their story is incredibly straight forward, and so is their love. Orin and Namqi meet not long after she arrived in the Last Safe City and left the Pilgrim Guard. He is Awoken, like her, which is a rare enough sight. Even rarer still, he wasn’t a Risen, but an Awoken of the Reef, a rather mysterious lot that keep to themselves, sharing their knowledge on weapons and medicine and agriculture with humanity but never revealing their home to those on Earth. Many people at this time would choose to avoid the Awoken whether they were Earthborn and Reefborn, so Namqi is surprised when Orin approaches him. She has an endless amount of questions for him, questions concerning their people, their home, and more. Over the course of two months—during which they repair his damaged Hildian together—she manages to convince him to bring her to the Reef, to break the queenslaw. Their initial connection is that strong.

“Most of all, Orin is struck by his ability to listen with empathy. He is quiet more often than not. Long silences don't frighten him. And when he speaks, he does it deftly, without condescension.” — Queenslaw, Ecdysis

This is a direct comparison to the way Orin’s own speech is described earlier in the Ecdysis book, and explains why she finds herself so drawn to Namqi in the first place. She has finally found a mirror for her own empathy, someone who can point all of her own warmth back at her in full, someone she feels utterly comfortable opening up to. For Orin—who is intensely aware of how powerful words can be and how careless people can be in wielding them—this is incredible, and the feeling is mutual considering his willingness to go against Mara Sov’s laws by smuggling an Earthborn Awoken into the Reef.

They’re caught almost instantly. Sjur Eido recognizes her old friend in Nasan in Orin, as does the Queen, who tells Orin her version of the rather tragic history of the Awoken. Namqi is given five years indentured service, wherein he gets to pick his service and negotiate his salary. Orin’s punishment is less severe, as she is not who she once was and so cannot be held accountable for her past oaths to the Queen. Instead, Mara demands a future debt of her choosing, of which Orin accepts. She is the first Guardian Mara ever trusts.

Orin returns to Earth and keeps in daily contact with Namqi, begging him to come get her when he is finally released so that they can explore and figure out what humanity was trying to achieve before the Collapse and the Dark Ages.

“They scour the inner planets in his Hildian. When parts of it break down, they work odd jobs.

They are deliriously happy.

Centuries pass.” — Debt, Ecdysis

Realizing that she never wants to leave Namqi isn’t a sudden revelation. It simply never occurs to her that she should leave, and that feeling of claustrophobia never comes. She doesn’t feel that terrifying restlessness she’s felt before—partly because they spend most of their time exploring but mostly because she feels complete with Namqi in a way she hasn’t experienced before. Their love matures, deepens, expands. They invite others to join them, in their travels and their love. They ground each other, and never spend more than a few months apart.

Eventually Mara cashes in on the debt that Orin owes her, asking Orin to search for her lover Sjur Eido’s murderer. Her search leads her to an encounter with Xûr, and the beginning of her transformation into the Emissary.

“Orin begins to experience waking hallucinations. Immaterial strangers speak to her in unrecognizable languages. When she reaches for Namqi, she feels as if she is falling into him, being pulled through him, sieved into smaller and smaller scarves of some atom-self that he breathes into the blood of his bones.” — Synesthesia, Ecdysis

When Orin tries to explain what she’s experiencing to Namqi ( and Mara and Gol ) he gives her—to her ears—empty reassurances, and tries to convince her to stop searching for the Nine. Orin does not listen, and goes on without Namqi in her search.

At this point in their relationship it’s not unusual for them to split off from each other. Orin is a part of the Firebreak Order, and so has duties concerning the City and the defense of its people by pushing into enemy territory. Namqi is still an Awoken of the Reef, and so has his own duties to the Queen and his people. They often go weeks or even months without seeing each other, sometimes without contact when in parts of the system that don’t permit communication.

This time when they split though, Namqi doesn’t return.

“On the day that Namqi dies, no one can reach her or Gol, though they do try.

She does not find out for months.” — Synesthesia, Ecdysis

Namqi dies in what is assumed to be an aphelion attack on the RSS Armestris. The recovered transcriptions say they thought the hull was breached, and describe a “glowing creature” and something called “the stalking core” attacking the crew. The ship—examined by drones because of the high levels of radiation on the surface—shows no sign of a hull breach, no evidence of shots fired, no signs of alien or internal interference. And no survivors.

When Orin eventually visits the Reef again, she is told of Namqi’s death, and taken to a room where she can listen to Namqi’s last recorded words.

“On the day she meets Wu Ming, she is on Bamberga. She has just left a Gensym lab. She has just read a transcript of Namqi's last words. Her hands are shaking. She feels nauseous. She feels she can see herself in third-person, tottering to a safe place to sit and cry.” — Synesthesia, Ecdysis

“T-4: ORIN, IT'S ME, IT'S NAMQI. I DON'T THINK I'M COMING HOME, BABY. I'M SO SORRY. I'M, I'M, I JUST WANT TO TELL YOU THAT I LOVE [STATIC FOLLOWS]” — Bamberga, The Dreaming City

At this point the Nine are still very much “haunting” her, and between her grief and slow descent into madness, Orin finds comfort in a man named Wu Ming. She doesn’t recognize him anymore, doesn’t recognize the man she knew and loved hundreds of years ago when she was still with the Pilgrim Guard as Eli. He chooses to lean into that, at first it seems to get information about the Nine from her. It quickly evolves into something deeper, something consuming. Something ultimately built on a lie.

And eventually Wu Ming can’t keep lying to Orin and tells her the truth: that he knows her, that they once knew each other, that he pretended to know Namqi, that he pretended not to know her.

The Nine use Wu Ming’s revelation to their advantage, driving her away from him and into their grasp by exacerbating her own feelings of betrayal. Maybe even as a bargain, the Nine revealed a path to save Namqi, but that’s purely speculation.

And while Orin succumbs to the transformation, she does not forget Namqi. In her most lucid states when she is the most herself, when she speaks and debates and argues with the Nine, she is thinking of Namqi. Even speaks as if he is listening.

“SAFE HARBOR IS VERY FAR AWAY

'Dogma. I'm sick of your dogma. I'll be just a little longer, Namqi.'” — Emissary, The Awoken of the Reef

This is mostly a method of coping. Orin has always existed as a liminal sort of being but as the Emissary she is even more so, to the point of beginning to lose sight of her own humanity. This is the inevitable outcome when who you are as a person has been pared down to the bone and taken over by beings incapable of understanding humanity. Namqi is the essence of love and empathy in her life. Speaking to him as if he were there with her helps ground her within the cold strangeness of Nine space, helps ground her within herself.

“I’ll be just a little longer,” she says, and part of her believes that if he is dead then perhaps she will die soon too when the Nine are done with her, and go wherever he has gone. More likely—as Orin is not overtly spiritual and does not necessarily believe in an afterlife—she thinks she can save him.

Whether this means the Nine were responsible for his death and merely made it seem otherwise and Orin knows this, or they have given Orin more knowledge about the aphelion and what might have become of Namqi and the rest of the crew of the Armestris is hard to say, though the latter seems more likely. In any case, she believes firmly that she will see him again. Whether dead or alive—for either of them—she can’t say.

Namqi is everything to Orin. He is the first person in her many lives that she lets love her in return, fully. She’s always been open with giving her own love, but it’s always been partly used as a sort of defense mechanism. If she loves harder, when it inevitably fails, when she inevitably grows restless and leaves, it will hurt them less if she doesn’t let them love her as much as she loves them.

But Namqi is the first instance of Orin opening herself to the terrifying notion of being completely known and fully loved. The first time she never worries about being made into something she’s not, something bigger than herself. The first time she doesn’t feel shackled by some nameless weight. He knows her, better than she knows herself. And she knows him the same way.

Even in death he’s one of the only reasons she remains human.

#meta.#when it’s over you’re the start / namqi.#a.#hi i'm emo about Them#and wrote way more than i expected lmao#HE'S JUST SUCH A BIG PART OF HER LIFEEEE#bungie i need to know more about him#long post#also i only skimmed this in terms of proofreading so if something is like SUPER bad please let me know ;asldkfj

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPAM Digest #2 (Oct 2018)

A quick list of the editors’ current favourite critical essays, post-internet think pieces, and literature reviews that have influenced the way we think about contemporary poetics, technology and storytelling.

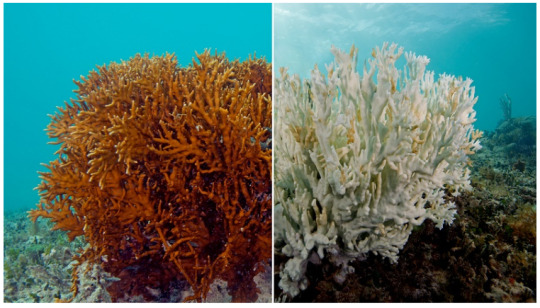

‘How to Write About a Vanishing World’, by Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker

Like many others, I’ve spent a week in a state of grief about the recent IPCC report. I’m all over The Guardian like a traumatised fungus, trying to find nourishment in the form of answers, devouring data I don’t understand. I sense the dyspeptic effects of all those figures. Thank goodness for Elizabeth Kolbert, author of The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (2014), who draws us back to the role of narrative in making sense of our vanishing world. Provocatively she opens with the familiar trope of the ‘stormy night’ and tells of ‘an American herpetologist named Marty Crump’ who, after a neighbourly tip, discovers the emergence of golden toads not far from her home in northwest Costa Rica. This is in the late eighties. These strange and beautiful creatures are part of the biospheric treasure trove whose loss Kolbert then documents across the intervening decades, up to the present. By the turn of the century, she suggests, biology had become a practice of living elegia: ‘A biologist could now choose a species to study and watch it disappear, all within the course of a few field seasons’.

Her article collects numerous other stories of scientists losing their subject — from Arctic ice to Great Barrier corals — until extinction becomes the presiding litany of our times. She notes how researchers find themselves paralysed, unsure of intended outcomes when faced with such scales of ecological loss. Even as scientific projects to assist vulnerable ecosystems gather in nuance and strength, there’s a sense that we’re already fighting a losing game. Science becomes a question of narrative transmission, as much as active intervention; by doing research, you’re sending some sort of message of hope. As Kolbert puts it, ‘Hope and its doleful twin, Hopelessness, might be thought of as the co-muses of the modern eco-narrative’, inspiring nature writers and scientists alike. The central question is ‘how we relate to that loss’: is it a question of elegy and mourning, or sparking a call to arms? Even those writers who urge us to act, who celebrate the potentials of direct intervention, admit that none of this will happen fast enough to make a lasting difference. Ending on the phrase ‘Lalalalalala, can’t hear you!’, Kolbert sardonically evokes that familiar, Trumpian stage of climate denial which has been rearing its all-too-human, deluded head of late. But what persists is the value of keeping on — ‘Narrating the disaster becomes a way to try to avert it’ (and here I am reminded of Maurice Blanchot’s writing of the disaster as a polysemous, irreducible event) — writing, as Kolbert does in this piece, our stories in the face of defeat. An earnest act in the face of inevitable cynicism, a careful digestion of failure. Maybe ecological writing just needs to be more metamodern.

M.S.

‘Your favorite Twitter bots are about die, thanks to upcoming rule changes’, By Oscar Schwartz, Quartz

Twitter bots fans, you might want to take a seat: there could be some terrible news out there. According to Oscar Schwartz and his article on Quartz, many of our favourite sources of coded linguistic beauty might disappear in the coming months due to what he calls ‘a company-wide attempt to eradicate malicious bots from the platform.’ A couple months ago, Twitter announced that they would start requiring bot developers to undergo a thorough vetting process in order to gain access to Twitter’s programming interface (where the essence of a Twitter bot lies) - an amount of bureaucratic load that prolific bot artists have told Schwartz would simply be too much work to keep up with.

Regardless of the bleak prediction, the think piece reads less like a eulogy for Twitter bots, and more like a defense of them. Schwartz provides us here with a real goldmine for Twitter bots to follow - from Jia Zhang’s @censusAmericans, which composes little biographies of nameless Americans by compiling information provided to the open census database, to Allison Parrish's @the_ephemerides, which couples images of distant planets from NASA’s archive with computer-generated poetry. In a statement to Schwartz, Parrish (a poet, computer-programmer, and educator as well as a Twitter-botter) states that ‘asking permission to make a bot is like asking someone permission to do graffiti on a wall (...) It undermines everything that is interesting about bot-making.” - a point that is not only rhetorically effective, but possibly a very productive way of conceptualising Twitter-bots as an art form.

‘For these bot-makers, letting their creations die off on Twitter is an act of protest. It’s not so much directed at the new developer rules, but at the platform’s broader ideology. “For me it’s becoming clear that Twitter is driven by a kind of metrics mindset that is antithetical to quality communication,” Parrish says. “These recent changes have nothing to do with limiting violent or racist language on the platform and are all about making it more financially viable.”

[Darius] Kazemi [another prominent bot artist] agrees, adding that to continue making creative bots on Twitter is making a bargain with the devil. “We’re being asked to trade in our creative freedom for exposure to a large audience,” he says. “But I am beginning to suspect that once we all leave Twitter, they will realize that we represent a lot of what made Twitter good, and that maybe the platform needs fun bot makers more than we need Twitter.”’

D.B.

‘Erasing the signs of labour under the signs of happiness: “joy” and “fidelity” as bromides in literary translation’, by Sophie Collins, The Poetry Society

Some of our most significant intellectual epiphanies occur in lecture theatres, often in resistance to the lecture in question. Maybe this is a form of vicarious translation. In her piece, Collins begins with an anecdote about a lecture she was looking forward to leaving her cold. The speaker’s takeaway slogan, the ‘joy of translation’, rang hollow as a company ‘mission statement’. Against this platitude from the corporate happiness factory, Collins explores the affective entanglements of reading translation through various types of negativity, the disciplinary disparities around its process, intentions and attendant critical debates. Drawing upon her own experience in translating literature from the Dutch, Collins explores the value of acknowledging struggle in translation — from ‘uncertainty and self-consciousness’ to ‘breakdown and frustration’. She makes room for the translator’s own vexed identity to be critically recognised in the process, and thus asks for analytic frameworks which keep in mind the theories around hybridity posited by thinkers such as Gayatri Spivak, Homi K. Bhaba and Julia Kristeva.

Working through the negative space of translation, Collins goes on to deconstruct the concept of ‘joy’ itself, upon whose insistence various arms of society’s ideological apparatus are able to keep us in stasis and check: ‘Given that the desire for happiness can cover signs of its negation, a revolutionary politics has to work hard to stay proximate to unhappiness’. Joy becomes less a personal experience than ‘something more like obedience to a collective cause’. Translation might allow us to notice relationality and difference between cultures; but as a creative act in itself, translation also provides a discursive technology for intervention in structures of power. Often denigrated as secondary or indeed ‘women’s work’, translation occupies a precarious position in the ‘creative hierarchy’, and this is reinforced by vacuous proclamations about its joy. Whose joy are we reveering here anyway? What we need, Collins argues, is a more complex set of theories around translation, which bring into play its disruptive, ‘negative’ aspects. Her productive alternative to ‘fidelity’ or ‘faithfulness’ as the goal or logic for translation is that of ‘intimacy’: a translation process that ‘exhibits a heightened contextualisation of its source text for the reader’; one that bears with it the often fraught emotional truths around the act of moving between texts, times, cultural tones and affective states. Emotional truths whose discernment opens a space for seriously ‘affirm[ing] the possibility of change’:

As a proposed ideal for translations, ‘intimacy’ brings with it its own questions, problematics and risks. Ultimately, however, my application of the term is intended to shift the translation relationship from a place of universality, heteronormacy, authority and centralised power, towards a particularised space whose aesthetics are determined by the two or more people involved, in this way amplifying and promoting creativity and deviant aesthetics in translations between national languages.

M.S.

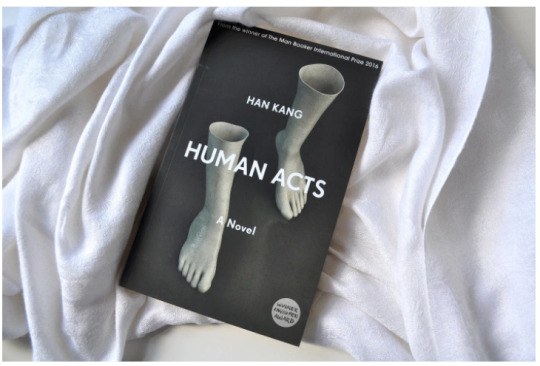

‘On Translating Human Acts’ by Han Kang - By Deborah Smith in Asymptote

Han Kang plays language with the kind of near-unbearable intensity which Jacqueline du Pré applied to the cello, exploring its sensory possibilities through a continual detailing of the minutely physical—a bead of sweat trickling down the nape of a neck, the rasp of even the softest fabric against skin—which builds to such a pitch that even the slightest physical contact, no matter how intentionally tender or gently performed, is felt as violence, as violation.

As someone who works in the field, I'm always eager to read the translator's note before commencing my reading of the work. Translators' introductions, beyond outlining the context of any novel, tend to reveal the hyper-specific difficulties they faced when attempting to replicate linguistic nuances of the source language into the target language. In this case, one example given was the 'brick-thick Gwangju dialect', as Korean dialects are distinguished by grammatical differences rather than individual words. Looking to avoid 'translationese', Smith identifies that her primary concern was the effect the text had over the reader, rather than specific syntactic structures, aiming for 'a non specific colloquialism that would carry the warmth Han intended'.

Already intrigued by Smith's introduction, and after having finished Human Acts, I continued my research of Smith, coming across much of the criticism she received by many academics for her translations of both The Vegetarian (she had been studying Korean for only three years before commencing this work) and Human Acts. In this essay, Smith takes us on a journey through the complexities and challenges she faced as a translator. One that really stuck out to me was the necessity to find as many possible synonyms for the verb 'to erase'. This word continued to resurface in the original often as a straight repetition. As Smith notes, Korean is 'far more tolerant' of this than English. I had once encountered a similar issue myself when translating a memoir based in one Rio de Janeiro's jails. The prisoners in that text frequently used the word 'parada', a local slang that can mean 'thing', 'business', 'occurrence', but is context specific. The heavy repetition of any of these options in English didn't read well, making the text clunky and awkward. Only through methodically finding specific synonyms to match with each context was I able to resolve this.

Out of all the nuances and subtleties Smith had to work through, none can be more thought-provoking than the title itself, 'Human Acts'. As Smith notes, a literal translation of the Korean would have resulted in the slightly awkward title 'The boy is coming', leaving her with the tricky task of finding a captivating title that retained the neutrality of the original. Read the full article to hear about which elements Smith had to keep in mind when deciding how to translate Kang's 'restrained Korean'.

M.P.

0 notes