#its also the fact that i do in fact know i have all these flaws/deficiencies/caveats

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

-

#i dun rly know but#some part of me is like: oh. im not hot.#my friends are all way hotter and prettier than me and i look like a fucking creature around them#and idk... i think its so natural for people to be in love with my friends#but i cannot believe someone would ever really like me. not for my looks. not for my personality.#i think. i never really was complimented. and when i was/am (by my parents) its always for an ulterior motive#its always 'ure so pretty. if only u just got thinner/put on makeup/dressed up nicer/stop being so loud'#like.... yay. glad to know no one really just likes me i guess#its always 'i like nycto but........“#theres always a fucking but in thesentence and i think that destroys me a bit inside#its also the fact that i do in fact know i have all these flaws/deficiencies/caveats#and its also just... i have a newly discovered fear of 'what if people talk to me because theyre just interested in my friend?'#which is somewhat irrational. but... gosh. my friends are just so much better hotter and cooler than me#i will just never be good enough. everyone else will always just be.... better than me#i wish i were hot. i know im aroace but fuck#i wish i didnt feel like an ugly awkward meatsack when my friends talk about their pretty privilege or when they get fawned over#because my friends ARE cool and wonderful. i rly do like them. but its with that sense of an ugly fish looking up at the most dazzling bird

0 notes

Link

At the link, or under the cut:

An important new study about global nutrition was published this week that deserves everyone’s full attention: "Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems." [Don’t let the pretentious title intimidate you: you need to know what’s inside.] This paper was commissioned and published by The Lancet—one of the world’s oldest and most respected medical journals—and penned by an international group of 37 scientists led by Dr. Walter Willett of Harvard University.

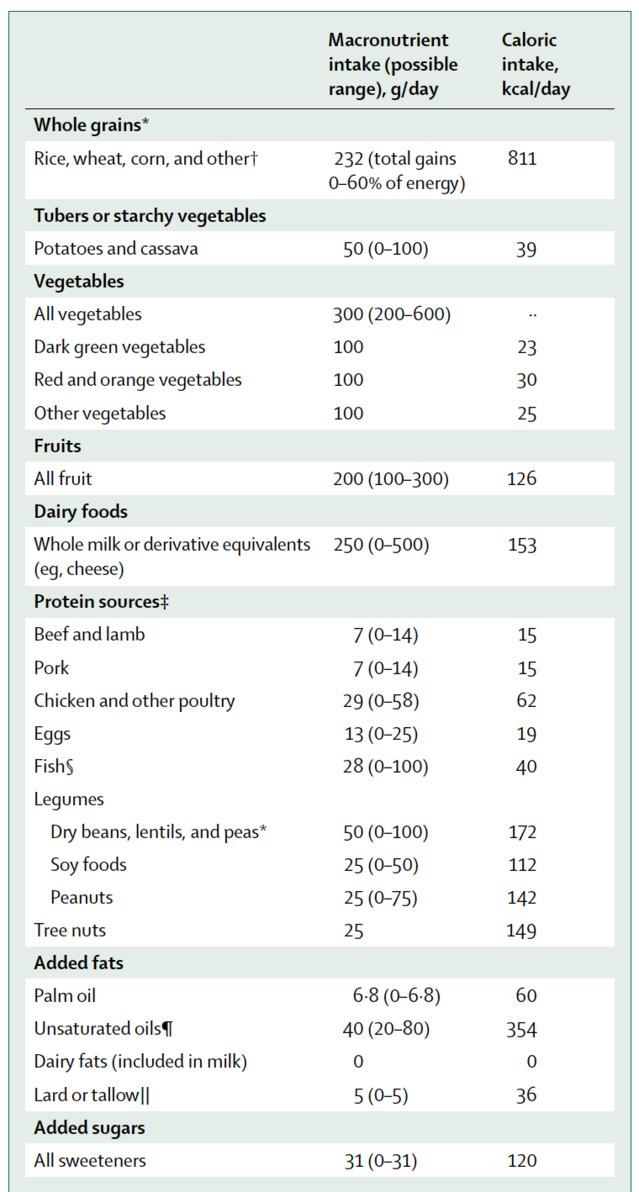

The product of three years of deliberation, this 47-page document envisions a “Great Food Transformation” which seeks to achieve an environmentally sustainable and optimally healthy diet for the world’s people by 2050. Its core recommendation is to minimize consumption of animal foods as much as possible, and replace them with whole grains, legumes and nuts:

Source: EAT-Lancet Commission report We all want to be healthy, and we need a sustainable way to feed ourselves without destroying our environment. The well-being of our planet and its people are clearly in jeopardy, therefore clear, science-based, responsible guidance about how we should move forward together is most welcome.

Unfortunately, we are going to have to look elsewhere for solutions, because the report fails to provide us with the clarity, transparency and responsible representation of the facts we need to place our trust in its authors. Instead, the Commission’s arguments are vague, inconsistent, unscientific, and downplay the serious risks to life and health posed by vegan diets.

1. Nutrition epidemiology = mythology

The vast majority of human nutrition research—including the lion share of the research cited in the EAT-Lancet report— is conducted using the tragically flawed methodology of nutrition epidemiology. Nutrition epidemiology studies are not scientific experiments; they are wildly inaccurate, questionnaire-based guesses (hypotheses) about the possible connections between foods and diseases. This approach has been widely criticized as scientifically invalid [see here and here], yet continues to be used by influential researchers at prestigious institutions, most notably Dr. Walter Willett. An epidemiologist himself, he wrote an authoritative textbook on the subject and has conducted countless such studies, including a recent, widely-publicized paper tying low-carbohydrate diets to early death. In my reaction to that study, I explain in plain English why epidemiological techniques are so untrustworthy, and include a sample from an actual food questionnaire for your amusement.

Even if you think epidemiological methods are sound, at best they can only generate hypotheses that then need to be tested in clinical trials. Instead, these hypotheses are often prematurely trumpeted to the public as implicit fact in the form of media headlines, dietary guidelines, and well-placed commission reports like this one. Tragically, more than 80% of these guesses are later proved wrong in clinical trials. With a failure rate this high, nutrition epidemiologists would be better off flipping a coin to decide which foods cause human disease. The Commission relies heavily on this methodology, which helps to explain why their recommendations often fly in the face of biological reality.

2. Red meat causes heart disease, diabetes, cancer...and spontaneous combustion

The section of the report dedicated to protein blames red meat for heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, obesity, cancer and early death. It contains 16 references, and every single one is an epidemiological study. The World Health Organization report tying red meat to colon cancer was also mentioned, and that report is almost entirely based on epidemiology as well. [Read my full analysis of the WHO report here]. The truth is that there is no human clinical trial evidence tying red meat to any health problem. I certainly haven’t found any—and if there were, I think this Commission surely would have mentioned it.

Yet even in this “red meat is an apocalypse on a plate” section, meat’s virtues peek through:

[In sub-Saharan Africa] “...growing children often do not obtain adequate quantities of nutrients from plant source foods alone…promotion of animal source foods for children, including livestock products, can improve dietary quality, micronutrient intake, nutrient status, and overall health.” [page 10]

3. Protein is essential…but cancerous

The commissioners write:

“Protein quality (defined by effect on growth rate) reflects the amino acid composition of the food source, and animal sources of protein are of higher quality than most plant sources. High-quality protein is particularly important for growth of infants and young children, and possibly in older people losing muscle mass in later life.” [page 8]

Translation: Complete proteins are good because they contain every essential amino acid. All animal proteins are naturally complete, whereas most plant proteins are incomplete. Watch how the authors wriggle their way out of this inconvenient truth in the next sentence:

“However, a mix of amino acids that maximally stimulate cell replication and growth might not be optimal throughout most of adult life because rapid cell replication can increase cancer risk.” [page 8]

Translation: Complete proteins are bad because they cause cancer.

The sole reference for this absurd suggestion that complete proteins cause cancer is a paper about mutations causing cancer in which the terms “protein,” “amino acid,” and “meat” each occur a grand total of zero times, suggesting that the Commission’s suggestion is pure...suggestion. Furthermore, if obtaining all of the essential amino acids we need causes cancer, shouldn't we also worry about complete proteins from plant sources like tofu or beans with rice?

4. Omega-3s are essential...good luck with that

“Fish has a high content of omega-3 fatty acids, which have many essential roles…Plant sources of alpha-linolenic acid [ALA] can provide an alternative to omega-3 fatty acids, but the quantity required is not clear.” [page 11]

If the Commission doesn’t know how much plant ALA a person needs to consume to meet requirements, then how does it know that plants provide a viable alternative to omega-3s from animal sources?

The elephant in the room here is that all omega-3s are not created equal. Only animal foods (and algae, which is neither a plant nor an animal) contain the forms of omega-3s our bodies use: EPA and DHA. Plants only contain ALA, which is extremely difficult for our cells to convert into EPA and DHA. According to this 2018 review, we transform anywhere between 0% and 9% of the ALA we consume into the DHA our cells require.

Instead of being vague, why not responsibly warn people that trying to obtain omega-3 fatty acids from plants alone may place their health at risk?

“About 28 g/day (1 ounce) of fish can provide essential omega-3 fatty acids…therefore we have used this intake for the reference diet. We also suggest a range of 0 – 100 g/day because high intakes are associated with excellent health.” [page 11]

Wait…if it takes 28 grams to meet your daily requirement for omega-3s AND high intakes are associated with excellent health, why allow the range to begin at ZERO grams per day? If the Commission doesn’t feel comfortable recommending fish, it should at least recommend algae-sourced omega-3 supplements.

5. Vitamins and minerals are essential…so take supplements

The drumbeat heard throughout the report is that animal foods are dangerous and that a vegan diet is the holy grail of health, yet EAT-Lancet commissioners repeatedly find themselves in the awkward position of having to acknowledge the nutritional superiority of the very animal foods they recommend avoiding:

"Although inclusion of some animal source foods in maternal diets is widely considered important for optimal fetal growth and increased iron requirement, especially during the third trimester of pregnancy, evidence suggests that balanced vegetarian diets can support healthy fetal development, with the caveat that strict vegan diets require supplements of vitamin B12." [page 13]

“Adolescent girls are at risk of iron deficiency because of rapid growth combined with menstrual losses. Menstrual losses have sometimes been a rationale for increased consumption of red meat, but multivitamin or multimineral preparation provide an alternative that is less expensive and without the adverse consequences of high red meat intake.” [page 13]

If the commissioners are concerned that red meat is dangerous (which is only true on Planet Epidemiology), why not recommend other naturally iron-rich animal foods such as duck, oysters, or chicken liver for these growing young women, as these foods would also provide the complete proteins needed for growth? What about the 10-22% of non-teen reproductive age women in the U.S. who suffer from iron deficiency? And why a “multimineral preparation” rather than a simple iron supplement? Are they implying that other minerals may be lacking in their plant-based diet?

In changing to the EAT-Lancet diet, the Commission claims:

“The adequacy of most micronutrients increases, including several essential ones, such as iron, zinc, folate, and vitamin A, as well as calcium intake in low-income countries. The only exception is vitamin B12 that is low in animal-based diets [I believe this was an error on their part, since B12 is only found in animal foods.] Supplementation or fortification with vitamin B12 (and possibly with riboflavin [vitamin B2]) might be necessary in some circumstances.” [page 14]

Unfortunately, the nutritional inadequacy of plant-based diets goes beyond B vitamins. Plant foods lack several key nutrients, and some of the nutrients they do contain come in less bioavailable forms. Furthermore, many plant foods contain “anti-nutrients” that interfere with nutrient absorption. This means that just because a plant food contains a nutrient doesn’t mean we can access it.

An important example is that grains, beans, nuts and seeds—the staple foods of plant-based diets—contain phytate, a mineral magnet which substantially interferes with absorption of essential minerals like zinc, calcium, iron, and magnesium. And thanks to oxalates—mineral-binding compounds found in a wide variety of plant foods—virtually none of the iron in spinach makes it into Popeye’s muscles.

Only animal foods contain every nutrient we need in its proper, most accessible form. To learn more about nutrient availability and how it affects brain health, read this article.

6. Making up numbers is fun and easy

How did the commissioners arrive at the recommended quantities of foods we should eat per day…7 grams of this, 31 grams of that? Numbers like these imply that something’s been precisely measured, but in many cases, it’s plain that they simply pulled a number out of thin air:

“Since consumption of poultry has been associated with better health outcomes than has red meat, we have concluded that the optimum consumption of poultry is 0 g/day to about 58 g/day and have used a midpoint of 29 g/day for the reference.” [page 10]

Nowhere do they say that poultry is associated with any negative health outcomes, so why limit it to a maximum of 58 grams (2 ounces) per day?

The commissioners attempt to defend themselves from criticism on this issue by stating:

“We have a high level of scientific certainty about the overall direction and magnitude of associations described in this Commission, although considerable uncertainty exists around detailed quantifications.” [page 7]

If they are this uncertain about the details, how can they in good conscienceprescribe such specific quantities of food? Why not say they don’t know? Most people will not read this report—they will interpret the values in this table as medical advice.

7. Epidemiology is gospel…unless we don’t like the results

Any researcher will tell you that clinical trials—actual scientific experiments—are considered a much higher level of evidence than epidemiological studies, yet Willett’s group not only relies heavily on epidemiological studies, it favors them over clinical trials when it suits their agenda:

“in large prospective [epidemiological] studies, high consumption of eggs, up to one a day, has not been associated with increased risk of heart disease, except in people with diabetes. “However, in low-income countries, replacing calories from a staple starchy food with an egg can substantially improve the nutritional quality of a child’s diet and reduce stunting. [randomized clinical trial]

“We have used an intake of eggs at about 13 g/day, or about 1.5 eggs per week, for the reference diet, but higher intake might be beneficial for low-income populations with poor dietary quality.” [page 11]

Why recommend only 1.5 eggs per week when epidemiological studies found that 1 egg per day was perfectly fine? And why skew your recommendations against low-income people, which make up a significant portion of the global population?

There is a remarkable paragraph on page 9 (too long to quote here) arguing that red meat was found to increase risk of death in epidemiological studies conducted in Europe and the USA, but not in Asia, where red meat (mainly pork) was associated with a decreased risk of death. Rather than grappling with this seeming contradiction, they simply dismiss the Asian findings as invalid, wondering if perhaps Asian countries haven’t been rich long enough for the risk to show up yet.

Wait, what?

8. Everyone should eat a vegan diet, except for most people

Although their diet plan is intended for all “generally healthy individuals aged two years and older,” the authors admit it falls short of providing proper nutrition for growing children, adolescent girls, pregnant women, aging adults, the malnourished, and the impoverished—and that even those not within these special categories will need to take supplements to meet their basic requirements.

Sadder still is the fact that the majority of people in this country and in many other countries around the world are no longer metabolically healthy, and this high-carbohydrate plan doesn’t take them into consideration.

"In controlled feeding studies, high carbohydrate intake increases blood triglyceride concentrations, reduces HDL [aka “good”] cholesterol concentration, and increases blood pressure, especially in people with insulin resistance.” [page 12]

For those of us with insulin resistance (aka “pre-diabetes”) whose insulin levels tend to run too high, the Commission’s high-carbohydrate diet—based on up to 60% of calories from whole grains, in addition to fruits and starchy vegetables—is potentially dangerous. The Commission half-acknowledges this by recommending that even healthy people limit consumption of starchy roots like potatoes and cassava flour due to their high glycemic index, but oddly does not mention grain and legume flours, or high glycemic index fruits, leaving the door open for processed food companies to market products like pasta, cereal and juice beverages to its plant-based planet. High insulin levels strongly increase risk for numerous chronic diseases and can mean a lifetime of medications, disability and early death. If the Commission read its own report it would find support for the notion that those of us with metabolic damage could be better off increasing our meat intake and decreasing our carbohydrate intake:

“In a large controlled feeding trial, replacing carbohydrate isocalorically with protein reduced blood pressure and blood lipid concentrations.” [page 8]

This was the 2005 OmniHeart trial, which used 50% plant protein and 50% animal protein. It would seem the only people who should eat a vegan diet are people who make the informed choice to eat a vegan diet, despite the risks.

9. Pay no attention to the money behind the curtain

As an advocate of meat-inclusive diets, I have often been assumed to have financial ties to the meat industry (which I do not), but how many people stop to question the financial (and professional) incentives that may influence doctors promoting plant-based diets? We all have personal beliefs and we all need to make a living, but honesty with oneself and transparency with the public should be paramount. The Nutrition Coalition has compiled a list of Dr. Willett's potential conflicts of interest here.

The EAT Foundation, which collaborated with The Lancet to produce this report, was founded by Norwegian billionaire and animal rights activist Gunhild Stordalen. EAT recently helped to launch "FReSH" (Food Reform for Sustainability and Health), a global partnership of about 40 corporations, including Barilla (pasta), Unilever (meat alternatives and vegetable oils), Kellogg's (cereals) and Pepsico (sugary beverages). Make of this what you will.

10. No to choices, yes to taxes?

How does EAT-Lancet propose to achieve its dream of a plant-based world? Many suggestions are put forth, but two are worth emphasizing: the elimination or restriction of consumer choices, and taxation. The EAT Foundation describes itself as:

"a non-profit startup dedicated to transforming our global food system through sound science, impatient disruption and novel partnerships.”

Sound science? Clearly not. But impatient disruption—what does that mean?

Regardless of how you feel about taxation as a tool for social change, consider the Commission’s own numerous exceptions to the plant-based rules, including pregnant women, children, the malnourished and the impoverished. Should we really support making animal foods—the only nutritionally complete foods on the planet—even more expensive for vulnerable populations? The notion of taxation is followed by a vague reference to the possibility of “cash transfer” social safety nets for women and children. This section of the report is representative of its overall elitist and paternalistic tone.

I believe, because I’m convinced by the science, that animal foods are essential to optimal human health. This is an uncomfortable biological reality we all have to wrestle with as creatures of conscience. Finding ways to support excellent health and quality of life for the creatures we depend on for our sustenance and vitality is one of our most important callings as caring stewards of our planet and all of its inhabitants. But I’m also a firm believer in personal choice. We each need to become experts in what works best for our own bodies. Eat and let eat, I say. It seems clear that EAT-Lancet commissioners are neither supporters of personal choice nor the transparent distribution of accurate nutrition information that would empower people to weigh the risks and benefits of various diets for themselves.

Challenge Authority

The EAT-Lancet report has the feel of a royal decree, operating under the guise of good intentions, seeking to impose its benevolent will on all subjects of planet Earth. It is well worth challenging the presumed authority of this group of 37 “experts,” because it wields tremendous power and influence, has access to billions of dollars, and is likely to affect your choices, your health, and your checkbook in the near future.

Capitalizing on our current public health and environmental crises, the EAT-Lancet Commission pronounces itself as the authority on the science of nutrition, exploits our worst fears, and seeks to dictate our food choices in accordance with its members' personal, professional and possible commercial interests.

To the best of my knowledge, there has never been a human clinical trial designed to test the health effects of simply removing animal foods from the diet, without making any other diet or lifestyle changes such as eliminating refined carbohydrates and other processed foods. Unless and until such research is conducted demonstrating clear benefits to this strategy, the assertion that human beings would be healthier without animal foods remains an untested hypothesis with clear risks to human life and health. Prescribing plant-based diets to the planet without including straightforward warnings of these risks and offering clear guidance as to how to minimize them is scientifically irresponsible and medically unethical, and therefore should not form the basis of public health recommendations. Georgia Ede, MD, is a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and nutrition consultant practicing at Smith College. She writes about food and health on her website DiagnosisDiet.com. Online: Diagnosis:Diet

#former vegan#exvegan#links#link#georgia ede#debunked#sustainability#veganism is unhealthy for a lot of people#veganism isnt healthy for a lot of people#not everyone should be vegan#not everyone can be vegan#nutrition#important#best of

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

After a crowded and lengthy contest for the Democratic presidential nomination, the party fell in line on Super Tuesday, effectively choosing Joe Biden as the best nominee for the 2020 election. But it would be a stretch to conclude that he was the best competitor in that contest.

His debate performances in 2019 and early 2020 were uneven and punctuated with awkward gaffes. He changed stances on some high-profile issues. And he’s never been a particularly distinguished public speaker or fundraiser. Also, unlike other candidates, such as Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg, Biden lacked a passionate following.

So how did he end up defeating everyone else?

If we want to understand how Biden won the nomination, we first need to understand the Democratic Party in the aftermath of the 2016 election. Biden won the 2020 nomination, arguably, because of the way Democrats interpreted Hillary Clinton’s loss four years ago.

As detailed in my upcoming book, “Learning from Loss: The Democrats 2016-2020,” one of the most consistent and consequential lessons from my conversations with Democratic activists, Democratic National Committee members, officeholders, and other party insiders, was a post-election narrative that blamed Clinton’s loss on her use of “identity politics.”

That’s obviously a loaded term, but I am using it to refer to Clinton’s outreach to women, people of color, the LGBTQIA community, and other marginalized groups during her 2016 campaign. According to many think pieces published shortly after the election, this is why Clinton lost. The argument went that by talking about race and identity bluntly, Clinton excluded working-class white people from a party they’d previously embraced. In turn, they responded by voting for a candidate who was very explicitly courting them: Donald Trump.

Of course, “identity politics” wasn’t the only explanation for the surprisingly close results of the 2016 election. A number of other theories propagated too, including that Clinton campaigned poorly or in the wrong places, that the party’s messaging was deficient, and that Russia and other outside actors tipped the scales for Trump. “She should’ve gone to Wisconsin,” “Bernie would’ve won,” etc., were all common post-election refrains. These sorts of narratives are common when a party loses, and, in many ways, are ultimately healthy in helping a party decide how to move forward from loss.

An important caveat to these explanations, however, is that they often aren’t based on very much hard data. That is, just because a candidate had a certain message and lost doesn’t mean that the candidate lost because of that message. In fact, we know that most campaign decisions have pretty modest effects, if any, on actual voting outcomes.

Politicians and parties still crave these narratives, though, especially when they lose. Winning, explains political scientist Marjorie Hershey, has a “fairly blunt, conservatizing effect on campaigners.” As long as they’re winning, they’re going to assume that whatever they’re doing is right, and they’ll continue to do it. Conversely, Hershey argues, those who lose an election will be very open to making changes the next time around, figuring that at least one of the actions they took last time was responsible for their loss.

To understand how these explanations of the 2016 election sat with Democratic Party insiders, I spoke with 65 Democratic activists — including party leaders and staff, campaign workers and donors — in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, South Carolina and Washington, D.C. on a regular basis.1 And over the course of these conversations, a pattern emerged: Nearly a third of the party activists I spoke with cited “identity politics” as one reason for Clinton’s loss.2

Now, this doesn’t mean this was the only explanation they gave. In fact, more activists said that the campaign messaging and strategy were defective, or that Clinton herself was to blame. A separate study I conducted of newspaper coverage in the wake of the 2016 election found that about a third of news stories and op-eds argued that Clinton lost because of her focus on identity politics.

This is significant because post-election narratives are one way a losing party can reassess its strategy. If a party believes, for instance, that Clinton lost because she was a bad candidate or because her campaign was flawed, it can pick a different candidate or improve its campaign tactics without needing to dramatically rethink what the party stands for. But believing Clinton lost because of identity politics is a much harder pill to swallow. Namely, because accepting that means undermining something many Democrats believe in — the importance of promoting diversity and enhancing the power of underrepresented groups.

There’s a long history of this narrative being used to explain loss within the modern Democratic Party, too. Pretty much any time it has lost at the presidential level, a substantial segment of the party is quick to blame its focus on diversity, and, in turn, urges the party to refocus on working-class white voters, who have been part of the Democratic coalition since the New Deal. After Walter Mondale’s loss to Ronald Reagan in 1984, for example, Tennessee’s Democratic Party chair said, “The perception is that we are the party that can’t say no, that caters to special interests and that does not have the interests of the middle class at heart.” A national Democratic leader complained about the emphasis the party placed on Black voters, lamenting that “White Protestant male Democrats are an endangered species.” The post-2016 environment was no exception, with Democratic leaders warning the party not to abandon the white working class.

Even the Democratic activists and insiders I spoke with who strongly support the party’s historical role in advancing underrepresented groups emerged from the 2016 election frightened and confused by its results. As one New Hampshire activist — a lifelong feminist — told me in early 2017, “Based on what happened with Hillary, I think we now need to nominate a man.” She added, “[Former President] Barack Obama is an incredibly strong man. He can’t do what he did and not be a strong man. But he didn’t project raging masculinity, and I think you kind of have to do that [to go up against Trump]. I hate to say that … I’m gonna get kicked out of the women’s club.”

Biden, then, was in many ways a logical choice for a party in this condition.

Surveys among Democratic voters and activists repeatedly showed that, even when they didn’t see Biden as their top candidate, they saw him as the most electable, and overall, they prioritized electability to a far greater degree than they had in recent elections.

Biden was also, in some ways, a relatively easy choice for party insiders — he was broadly popular among the party’s voters, performed well in general election matchup polls, was closely tied to the Obama administration as its former VP, and was one of the only candidates who received widespread support from Black voters. But, at the end of the day, Biden also represented a safe choice for a party that had tried something new in 2016 and, in the eyes of many, had been punished for it.

0 notes

Text

The NFL Is Drafting Quarterbacks All Wrong

No position in professional sports is more important or more misunderstood than the quarterback. NFL scouts, coaches and general managers — the world’s foremost experts on football player evaluation — have been notoriously terrible at separating good QB prospects from the bad through the years. No franchise or GM has shown the ability to beat the draft over time, and economists Cade Massey and Richard Thaler have convincingly shown that the league’s lack of consistent draft success is likely due to overconfidence rather than an efficient market. Throw in the fact that young QBs are sometimes placed in schemes that fail to take advantage of their skills,1 that red flags regarding character go unidentified or ignored2 and that prospects often lack stable coaching environments, and there is no shortage of explanations for the recurring evaluation failures.

All of this uncertainty makes the NFL draft extremely exciting: You never know for certain who will be good and who will be an absolute bust. Last year, much of the pre-draft speculation surrounded where current Buffalo Bills starting QB Josh Allen — who is tall and can hit an upright from his knees from 50 yards away — would be selected. This year, when Oklahoma’s Kyler Murray decided to forgo a career in baseball for a chance to become a top pick in the 2019 NFL draft, his measurables captured attention in a different way. Murray, listed at 5-foot-10 and 194 pounds, is 7 inches shorter and more than 40 pounds lighter than Allen, and he’s the the smallest top QB prospect in recent memory. While some scouts and NFL decision makers think Murray’s odds for NFL success are long — or have him off their draft boards entirely because of his lack of size — there is strong evidence in the form of metrics and models that he is actually a good bet to succeed.

Like the rest of the league, practitioners of analytics have a pretty poor track record at predicting QB success. It wasn’t just Browns fans who were high on Johnny Manziel — many predictive performance metrics liked him as well. If some of the world’s best football talent evaluators are convinced that Murray’s height is at least a minor red flag, how can we be confident that a 5-foot-10 college QB will be productive in the NFL? When it comes to the draft, deep humility is warranted. Still, there are solid reasons to be excited about Murray.

Completion percentage is the performance measurable that best translates from college to the NFL. The metric’s shortcomings — players can pad their completion percentage with short, safe passes, for instance — are well-known. But even in its raw form, it’s a useful predictive tool.

Completion percentage translates from college to the NFL

Share of NFL quarterback performance predicted by college performance in seven measures, 2011-18

share predicted Completion percentage 17.9%

–

Average depth of target 16.7

–

ESPN’s Total QBR 12.1

–

Yards per game 9.2

–

Touchdown rate 8.5

–

Yards per attempt 7.0

–

Adjusted yards per attempt 4.2

–

For players who attempted at least 100 passes in the NFL.

“Share predicted” here refers to the amount of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable in a bivariate regression.

Source: ESPN Stats & information group

Its kissing cousin in the pantheon of stats that translate from college to the pros is average depth of target: Passers who throw short (or deep) in college tend to continue that pattern in the NFL. These two metrics can be combined3 to create an expected completion percentage, which helps correct the deficiencies in raw completion percentage. If you give more credit to players who routinely complete deeper passes — and dock passers who dump off and check down more frequently — you can get a clearer picture of a player’s true accuracy and decision-making.

Another important adjustment is to account for the level of competition a player faced. ESPN’s Total Quarterback Rating does this, and we’re doing it, too. For instance, passes in the Big Ten are completed at a lower rate than in the Big 12 and the Pac-12. We should boost players from conferences where it is tougher to complete a pass and ding players whose numbers are generated in conferences where passing is easier.

When we make these adjustments, and then subtract expected completion percentage from a QB’s actual completion percentage, we get a new metric: completion percentage over expected, or CPOE. An example: In 2011 at Wisconsin, Russell Wilson had a raw completion percentage of 73 percent. We would expect an average QB in the same conference who attempted the same number of passes at the same depths that Wilson attempted to have a completion percentage of just 57 percent. So Wilson posted an incredible CPOE of +16 percentage points in his last year of college. CPOE translates slightly less to the NFL than either raw completion percentage or average depth of target,4 but it does a substantially better job of predicting on-field production. In stat nerd parlance, we’ve traded a little stability for increased relevance.

CPOE best predicts yards per attempt in the NFL

Share of an NFL quarterback’s yards per attempt predicted by college performance measures, 2011-18

share predicted Completion percentage over expected 15.5%

–

Completion percentage 13.5

–

ESPN’s Total QBR 13.2

–

Yards per attempt 7.0

–

Average depth of target 0.0

For players who attempted at least 100 passes in the NFL.

“Share predicted” here refers to the amount of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable in a bivariate regression.

Source: ESPN Stats & Information group

The test of a good metric is that it is stable over time (for example from college to the NFL) and that it correlates with something important or valuable. Completion percentage over expected is slightly more stable than other advanced metrics like QBR. CPOE is also the best predictor of NFL yards per attempt. Since yards per attempt correlates well with NFL wins, and winning is both important and valuable, we’ve found a solid metric. It should help us identify NFL prospects likely to be good — so long as they are drafted and see enough playing time to accumulate 100 or more passing attempts.5

But before we stuff the metric into a model and start ranking this year’s quarterback prospects, it’s worth asking why CPOE in college might be a good measure of QB skill. One possible explanation is that it’s measuring not just accuracy but also the signal from other qualities that are crucial to pro success. The ability to consistently find the open receiver and complete a pass to him requires a quarterback first to read a defense and then to throw on time and on target. Throwing with anticipation and football IQ are both crucial to playing in the NFL at a high level, and they are likely both a part of the success signal in the metric.

CPOE is also probably capturing the ability to execute a system efficiently. A quarterback who understands how each piece of the offense complements the others and constrains the opposing defense is a huge asset for his team. The term “system QB” has a negative connotation in player evaluation circles that is probably unwarranted. If a quarterback is operating at a high level, he is inseparable from the system he’s being asked to run. It’s also likely the case that the mental and physical abilities to run any system efficiently are traits that translate — even if only imperfectly — to the pro game.

CPOE also measures accuracy, of course — which many believe is the most important trait a QB can posses. Some coaches believe accuracy is an innate skill and not something that can be taught once a player has reached college. Others believe that mechanical flaws can be corrected if other traits like arm strength are present. The Bills clearly hold this view or they wouldn’t have drafted Allen, a player with an incredibly live arm but who had a college completion rate 9.2 percentage points below expected. But regardless of whether accuracy can be taught at the NFL level, all evaluators acknowledge its importance.

With all this in mind, I built a simple logistic regression model that attempts to identify players who will go on to establish a career mark of at least 7.1 yards per attempt in the NFL — the league average from 2009 to 2018. The model took into account CPOE and six other metrics, all calculated for the player’s college career.6 There are 49 quarterbacks who have entered the NFL since 2012 who have also attempted at least 100 passes — except for small-school QBs for whom advanced college data wasn’t available. I randomly split those players into two sets and used one set to build the model and the second set to test to see if the model is any better than random chance at identifying which prospects will go on to play productive NFL football. Though the model is relatively simple — and it would be wonderful if the sample size were larger — the results are promising. The model correctly identified many players who went on to have NFL success and many more who didn’t. The best estimate for its generalized accuracy is that it will correctly identify a QB prospect as a hit or a bust in around 74 percent of cases.7 The table below shows the results of the model, labeled Predict, and includes players’ college stats.

Results from the quarterback prospect model

A random sample of the 49 quarterbacks who were drafted since 2012* by model probability, along with college stats including completion percentage over expected (CPOE)

College stats name CPOE YPA Avg. depth of target Total QBR Predicted prob.† Career NFL YPA Russell Wilson +16 10.3 10.4 94 >99% 7.9 Johnny Manziel +9 9.1 8.8 89 99 6.5 Jameis Winston +8 9.4 9.6 83 98 7.6 Kellen Moore +10 8.7 7.8 86 97 7.5 Deshaun Watson +5 8.4 8.8 86 93 8.3 Sam Darnold +5 8.5 9.5 80 77 6.9 Matt Barkley +4 8.2 8.1 77 73 7.4 Jared Goff +1 7.8 9.0 74 61 7.7 Kevin Hogan +4 8.5 9.3 80 37 6.1 Marcus Mariota +4 9.3 8.2 90 33 7.2 Kirk Cousins +4 7.9 8.5 58 29 7.6 Paxton Lynch +2 7.4 7.9 59 14 6.2 Geno Smith +3 8.2 7.3 74 5 6.8 Nathan Peterman +1 7.9 8.9 71 4 4.3 Zach Mettenberger +4 8.8 10.5 71 4 6.8 Trevor Siemian 0 6.4 8.2 53 3 6.8 Matt McGloin -2 7.2 8.5 60 2 6.7 Blake Bortles +4 8.5 7.5 78 1 6.7 Lamar Jackson 0 8.3 11.0 82 0 7.1

*And have attempted at least 100 passes in the NFL.

†Probability the player will meet or exceed a career yards per passing attempt average of 7.1.

Source: ESPN stats & information group

Humility is warranted at this moment, so let’s point and laugh at the failures first. After all, all models are universally wrong, but some can be useful. This one was wrong about Johnny Football, as it practically guaranteed Manziel to be an above-average NFL quarterback. What it didn’t know about was Johnny’s love of all-night parties and other off-field shenanigans. Kellen Moore, a lefty passer who had a decorated career at Boise State, is another hiccup for the model. Moore is an interesting case of a player who just barely reached the 100 passing attempt threshold and eclipsed 7.1 yards per attempt for his NFL career but still bounced around the league and never found success or even a starting job. So the model predicted his statistical success in yards per attempt but not his actual success on the field. The problem here is that our success metric — career yards per attempt over 7.1 — doesn’t perfectly discriminate between good and bad NFL QBs. Much like human evaluators, models can sometimes be right for the wrong reasons, and Moore is a prime example.8

The model was also suspiciously bad at predicting Lamar Jackson, ranking him as an almost sure bust as a passer. Jackson’s career yards per attempt — most of those attempts coming in just seven games — is right at the 7.1 threshold, and while he is no one’s idea of Drew Brees, a success probability of zero seems an overly harsh assessment for a player that has clear talent — especially running the ball — and has already helped his team to the playoffs.

Still, the good outweighs the bad. The only other false negatives in the bunch are Kirk Cousins and Marcus Mariota, both of whom have career yards per attempt figures above 7.1. Meanwhile the low probabilities assigned to passers like Nate Peterman, Zach Mettenberger, Paxton Lynch, Geno Smith and Blake Bortles all appear reasonably prescient.

Looking forward and applying the model to the current draft class, we find a few surprises. Kyler Murray sits comfortably at the top with a 97 percent probability of being an above-average pro quarterback. Murray’s physical and statistical production comps with Russell Wilson are especially striking. Wilson and Murray had roughly the same yards per attempt in college, identical average depth of target and similar Total QBR.9 Both are also under 6 feet tall and played baseball at a high level. As far as comps go for short QBs, you really can’t do any better.

Murray isn’t just a scrambler who excels working outside of the pocket and on broken plays, either. According to the ESPN Stats & Information Group, 91 percent of Murray’s 377 pass attempts in 2018 came inside the pocket, and 81.6 percent of those throws were on target and catchable. Murray faced five or more defensive backs on 82 percent of his passing attempts and threw a catchable pass 78.8 percent of the time. Against nickel and dime packages, he was even better when blitzed, with 79.1 percent of his passes charted as catchable when the defense brought pressure. And Murray didn’t just check down to the outlet receiver when the other team sent heat. Kyler pushed the ball downfield at depths of 20 yards or greater 21 percent of the time vs. a blitzing defender.

Meanwhile the other consensus first-round talent, Ohio State’s Dwayne Haskins, is viewed as much less of a sure thing by the model. While his CPOE is identical to Murray’s and his QBR is similar, the model rates his yards per attempt and low average depth of target as red flags that drag down his probability of success. Nickel is the base defense in the NFL, so a quarterback’s performance against it is important, and Haskins faced five or more defensive backs far less often than Murray, dropping back against nickel or dime on just 63 percent of his pass attempts. And when Haskins was blitzed out of those looks, he was not as adept at delivering on-target passes, with 76.4 percent charted as catchable despite only 6.6 percent traveling 20 yards or more in the air.

Kyler Murray’s accuracy and rushing put him atop his class

College quarterbacks invited to the 2019 NFL combine by their career statistics and predicted probability of success*

College stats Player CPOE YPA Avg. depth of target Total QBR Predicted Prob.† Kyler Murray +9% 10.4 10.4 92 97% Will Grier +6 9.0 10.2 78 90 Ryan Finley +4 7.6 8.5 76 78 Jordan Ta’amu +6 9.5 10.1 72 72 Dwayne Haskins +9 9.1 7.8 87 63 Brett Rypien +5 8.4 9.9 67 39 Jake Browning +3 8.3 8.8 73 38 Clayton Thorson 0 6.3 7.9 61 29 Trace McSorley +3 8.1 9.7 73 22 Daniel Jones -2 6.4 7.7 62 17 Gardner Minshew +2 7.1 6.8 70 4 Jarrett Stidham +3 8.5 8.3 69 3 Kyle Shurmur -3 7.0 9.0 59 1 Drew Lock -1 7.9 10.3 66 <1 Tyree Jackson -2 7.3 10.4 59 <1 Nick Fitzgerald -4 6.6 10.2 72 <1

*Excluding Easton Stick because of lack of data

†Probability the player will meet or exceed a career average of 7.1 yards per passing attempt

Source: ESPN Stats & Information Group

Other surprises from the consensus top-four prospects are the rankings of Duke’s Daniel Jones and Missouri’s Drew Lock — both of whom completed fewer passes than we would expect, and both of whom were assigned a low probability of NFL success. Teams should probably be very wary of both players. Since 2011, college QB prospects with completion percentages under expected — a list that includes Brock Osweiler, Trevor Siemian, Mike Glennon, Matt McGloin and Jacoby Brissett — have all failed to post career yards per attempt above the league average of 7.1. Meanwhile West Virginia’s Will Grier — a player few experts have mocked to go in the first round — looks to be the second-best QB prospect of the class. With his excellent college production and nearly prototypical size at 6-foot-3 and 217 pounds, Grier is a player whose stock could rise with a good performance on and off the field at the combine.

There are many weeks of interviews, testing and evaluation left to come for each of these prospects, and analytics are just one piece of the process. Models are certainly not a player’s destiny. Murray might end up profiling as a selfish diva who can’t play well with others. Lock could somehow morph into Patrick Mahomes. But ultimately the model and the metrics agree with Arizona Cardinals coach Kliff Kingsbury’s assessment that Murray is worthy of the top overall pick in the draft. Ship him off to a team with an early pick and a creative play-caller, and enjoy the air raid fever dream that follows.

from News About Sports https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-nfl-is-drafting-quarterbacks-all-wrong/

0 notes

Text

Diabetes Myths that Confuse People

Being diabetic, you may come across misplaced information or diabetes myths from friends and relative, who have no first-hand experience of this illness. I don't know why people always want to make point of something that they don't understand fully; They don't understand that this half-baked information will only harm the patient and will make his condition worse.

Even the internet is not spared, you can find lots of information that are poorly researched. In the 21st century, we are living in an information world where every data is available in a single click; but whose gonna validate the information, there is so much information available which has potential to harm the society rather than doing good. In this article, we will try to address the common diabetes myths and find out the real truth with proper reasoning. MYTH#1 Eating Sugar food can make you diabetic Most of the people who get diagnosed are always told that they should have taken care of their diet. I have experienced this situation firsthand, where people came to preach me about the healthy lifestyle; some of the people go the extent of blaming me for the condition. Let me tell you that, even before the diagnosis I was very particular of my diet, I used to stay away from the sugary soft drinks, used to eat home-based food most of the time. Yes, I had my weak days when I use to savor my favorite ice cream, but who doesn't!! Not everybody ends up getting diabetes. The truth is that a large number of factors come into play to get this condition and eating unhealthy diet is one of them. Eating foods that are high in carbs can put a lot of pressure in your pancreas that can end up giving you Type 2 diabetes, but it is not a universal rule. There are people who were extremely careful about their food, used to exercise daily, but still end up getting this problem. WHY? Because there are multiple factors coming into play. Factors like genetic susceptibility, Vitamin D deficiency, stress, family background. infection etc are some of many. So before you feel guilty about yourself, remember that getting diabetes may not be your fault. Read about different forms of diabetes by clicking here

MYTH#2 Only fat people get affected by Type 2 diabetes This is the ridiculous thing I have ever heard. Please note that around 20% of people with type 2 diabetes are of normal weight. In other statistical data, around one-third of American adults are obese, but the diabetes rate is just under 10%. If obesity would have been the necessary condition for getting diabetes, the rate would have closely matched the data. As I have said earlier, there are multiple factors that come into play which give birth to this problem and obesity is just one of those factors. Click here to find if you are Type 1 or Type 2 MYTH#3 Okra (ladyfinger) can make you diabetic free Let me state you for once and all. Okra doesn't cure diabetes!!!!!!!!!!! If you are diabetic and looking for ways to cure it, sorry to disappoint you, but there is no cure available for this problem till date. I have been researching on this subject for quite some time now and can confirm you that any claim coming across for cure is just baseless and is placed on the intention to loot money from this lucrative market. But this doesn't mean that Okra is useless for you. Just like any other vegetable, this food also has a lot of nutrients to offer. This vegetable has been packed with essential vitamins and nutrients that not only nourish your body but also helps diabetic to reduce fasting blood sugar. Read about the foods that are diabetic friendly by clicking this link MYTH#4: People with diabetics tend to face lot of problems and they die early In a research, it has been found that people with diabetes have 10 years short life as compared to the normal individual. Please note that the result is an average number which includes people who are not managing their diabetic effectively. Sure, Diabetes can be very dangerous and there is always a risk of diabetic complication. But if you are serious about your illness and have determined that you will manage your blood sugar properly you will live an active life as any other normal person. People with diabetes do not die because of this illness, they die due to poorly managed blood sugar. Try to maintain your blood sugar as close to normal and you will stay away from the complications. Read about blood sugar level that diabetic should target by clicking here MYTH#5: People with diabetes shouldn't play any sport What if I tell you that there are diabetic sports personalities who are performing exceptionally well in the world forum. In fact, there is a team called Team Novo Nordisk where all the athletes are Type 1 diabetic. They have not only participated in various sporting events but has won numerous accolades in the global platform.

But there is one caveat; whenever you participate in an event that is physically demanding, make sure to check your blood sugar before and after the game. WHY? Because there is a possibility for a diabetic, especially for Type 1, to run into Hypoglycemia. Hence it's wise to have some glucose before participating in any sport. Also, don't forget to keep glucose bar in your pocket in case of emergency strike during mid-sport. Read about the famous personalities that are diabetic MYTH#6: Diabetes is only for old people Most of the people I talk to only know diabetes as a lifestyle disorder which occurs only to old people. I think that its now a high time for people to understand that diabetes is not only related to lifestyle problem, there are multiple factors involve and can happen at any age. Even Type 2 diabetes which was earlier know to affect aged population is on the rise among the youth. So, if you get to meet any young diabetic, don't embarrass him by saying that "you are too young for it" 5 Things not to say to diabetic person MYTH#7: Diabetics are not fit for marriage Especially in a country like India where arranged marriage is a norm, diabetics find difficult to find a marriage partner. WHY? Because people think that the person may not be suitable for this nuptial ties and whose gonna struggle with a partner who is facing chronic medical condition. I think the argument made by the society is completely flawed. Diabetics are just like a normal person who just had an additional responsibility to manage the blood sugar. They can be as loving and may be more compassionate with their partner. I think that diabetics are more realistic about their life; they understand that life is short and anything can happen to any of us; this understanding make them more caring as a person. And argument about suffering from this lifelong illness; Is there any guarantee that your perfect healthy partner may not develop any illness after the marriage? Diabetes is on rise, though one may not have it now, according to current statistics, there are high chances to develop in any individual. So can you be so sure that the dream partner you are looking for, may not develop diabetes in future? I think we all going in the wrong direction. If you love any person and you believe that he is your soulmate, don't hesitate to get married to that person. FINAL WORD Those were the top 7 myths that I felt should be dispersed. If you have come across such misinformation, feel free to share with us in the comment below. Also, if you liked the article, make sure to share it across your community. Your sharing will motivate us to write more article in the future. Thanks Read the full article

0 notes