#italian prison officers unions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there a narrative/thematic reason Harper works for a drone company specifically?

In workplace ennui stories, like Dilbert and Office Space, it's often unclear what the protagonist actually does at their job, or even what their company does. For Cockatiel x Chameleon, my goal was to juxtapose Harper's ennui and sense of complete personal stagnation with a "real world" that remains intensely political and conflicted. This logic underlies the irony of the "End of History" motif. While Harper and even the impoverished Van Der Gramme are insulated from a history that continues with or without them, the other characters are repeatedly crushed by it. So, positioning Harper as some small cog in the military-industrial complex highlights that innate contradiction between Harper's lived experience and the political reality of the world.

Part I Chapter 6, which is the main chapter that deals with Crux Calico, is titled "Sun shining ecclesiastical"; readers of Cleveland Quixotic might better understand the reference to the Biblical Book of Ecclesiastes, in which the quote "Nothing new under the sun" is repeated to signify world-weariness and nihilism. The chapter title is rephrased to, ironically, convey a more positive connotation, a sort of celebration of sameness, which corresponds to the chapter's setting at a convention in which people from around the world gather in earnest enthusiasm of the company Harper views as a stagnant prison. The title is accompanied by a Futurist painting by Gino Severini depicting an armored train with soldiers; the Futurists, a group of primarily Italian painters in the early 1900s, were extremely excited by the prospects of machinery and war (to the extent that many went ahead and got themselves killed in World War I), and in some ways were predecessors to the fascist movement. (Royce Ru is also introduced in this chapter, and is a sort of Futurist in his own right.) All of this neatly sums up the inherent contradiction in Harper's existence: She is positioned on the bleeding edge of new technology that drives political conflict and change across the world, yet is herself devoid of hope or even the capacity to visualize a future for herself. (Part III Chapter 7 is another good place to look for this contradiction; there, Harper's "big boss" first describes the cyclical nature of wildfires as burning up an accumulated pile of "useless crap," then goes on to describe the capitalistic model of perpetual growth as essential for Crux Calico's continued survival.)

There are other reasons, though. The explanation of Crux Calico's hastily-assembled consumer products division, in which the company is described as being "autistic" (shortly after Harper's first real conversation with Sister, who bandies the word about frequently), dovetails nicely into the struggles Harper herself is having with interpersonal communication. This consumer division story, which details the conflict between American and Chinese drone companies, also brings up a specter that haunts Cockatiel x Chameleon: the looming conflict between the United States and China. Brought up a few times throughout the story, such as in Papimon's description of how her parents made her learn English and her twin sister learn Chinese to "hedge their bets," this seemingly cataclysmic future event is a constant nagging question to the motif of the "End of History." (To culminate this idea, I originally intended to have the story end with Van Der Gramme accepting a commission to draw porn for Chinese gacha game Genshin Impact, but couldn't find a way to fit it in.) Royce Ru, being a North American of Chinese descent, exemplifies his optimistic vision of the future by suggesting a union, rather than conflict, between these two spheres of power.

The last reason is a simple pun: a drone is also an insect in a colony, or a monotonous sound, both definitions suggesting dullness and tedium. I call attention to this by mentioning how official company correspondence refers to drones as UAVs due to a perceived negative connotation behind the word drone.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 2.2 (after 1920)

1920 – The Tartu Peace Treaty is signed between Estonia and Russia. 1922 – Ulysses by James Joyce is published. 1922 – The uprising called the "pork mutiny" starts in the region between Kuolajärvi and Savukoski in Finland. 1925 – Serum run to Nome: Dog sleds reach Nome, Alaska with diphtheria serum, inspiring the Iditarod race. 1934 – The Export-Import Bank of the United States is incorporated. 1935 – Leonarde Keeler administers polygraph tests to two murder suspects, the first time polygraph evidence was admitted in U.S. courts. 1942 – The Osvald Group is responsible for the first, active event of anti-Nazi resistance in Norway, to protest the inauguration of Vidkun Quisling. 1943 – World War II: The Battle of Stalingrad comes to an end when Soviet troops accept the surrender of the last organized German troops in the city. 1954 – The Detroit Red Wings played in the first outdoor hockey game by any NHL team in an exhibition against the Marquette Branch Prison Pirates in Marquette, Michigan. 1959 – Nine experienced ski hikers in the northern Ural Mountains in the Soviet Union die under mysterious circumstances. 1966 – Pakistan suggests a six-point agenda with Kashmir after the Indo-Pakistani war of 1965. 1971 – Idi Amin replaces President Milton Obote as leader of Uganda. 1971 – The international Ramsar Convention for the conservation and sustainable utilization of wetlands is signed in Ramsar, Mazandaran, Iran. 1980 – Reports surface that the FBI is targeting allegedly corrupt Congressmen in the Abscam operation. 1982 – Hama massacre: The government of Syria attacks the town of Hama. 1987 – After the 1986 People Power Revolution, the Philippines enacts a new constitution. 1989 – Soviet–Afghan War: The last Soviet armoured column leaves Kabul. 1990 – Apartheid: F. W. de Klerk announces the unbanning of the African National Congress and promises to release Nelson Mandela. 1998 – Cebu Pacific Flight 387 crashes into Mount Sumagaya in the Philippines, killing all 104 people on board. 2000 – First digital cinema projection in Europe (Paris) realized by Philippe Binant with the DLP CINEMA technology developed by Texas Instruments. 2004 – Swiss tennis player Roger Federer becomes the No. 1 ranked men's singles player, a position he will hold for a record 237 weeks. 2005 – The Government of Canada introduces the Civil Marriage Act. This legislation would become law on July 20, 2005, legalizing same-sex marriage. 2007 – Police officer Filippo Raciti is killed when a clash breaks out in the Sicily derby between Catania and Palermo, in the Serie A, the top flight of Italian football. This event led to major changes in stadium regulations in Italy. 2012 – The ferry MV Rabaul Queen sinks off the coast of Papua New Guinea near the Finschhafen District, with an estimated 146–165 dead. 2021 – The Burmese military establishes the State Administration Council, the military junta, after deposing the democratically elected government in the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état.

0 notes

Text

Maxi frode fiscale, arrestato l’ex vicepresidente del Livorno

97 million euros seized from 16 people and two companies operating in the telecommunications sector

The Guardia di Finanza arrested for tax fraud the former vice president of Livorno football club, thirty-nine-year-old Guido Presta , and his brother Ivan, 42, while two other people are under house arrest.

The entrepreneur, president of the NovaRomentin team and now in prison, was at the top of the Amaranth company three years ago. Furthermore, 97 million euros were seized from 16 people and two companies active in the telecommunications sector.

The investigation

"The investigation - explains the finance - originates from a complex of tax inspection activities started during 2022 by the economic-financial police unit of Milan and the anti-fraud office of the Revenue Agency, which led to the emergence of a sophisticated circuit of false invoicing in the sector of international VoIP data traffic trade. As part of the investigations, in October 2023, an Italian broker formally resident in Switzerland had already been arrested and over 50 million had been seized, an amount corresponding to evaded VAT. The tax and judicial investigations following this intervention made it possible to reconstruct further links in the fraud chain, identifying two other Italian entrepreneurs, also resident in Switzerland, who headed shell companies and some "buffers", as well as two other individuals from Novara who acted as recruiters and coordinators of the figureheads to whom the legal representation of the companies used in the fraudulent circuit was attributed".

«False invoices»

"The false invoices, concerning "data traffic", passed through foreign "conduits", Italian shell companies and filter companies, to then reach the companies benefiting from the tax fraud on the national territory which, by reselling to the first foreign companies, through a non-taxable VAT transaction, reduced their tax debt giving rise to a new carousel of false invoices - conclude the Guardia di Finanza -. The investigations, still ongoing, carried out by the Guardia di Finanza of Milan under the coordination of the European Prosecutor's Office, demonstrate the commitment made to protect the security and economic-financial legality of the country and the European Union, with reference to the fight against VAT fraud".

0 notes

Text

O'Neill Circum Sets (Master Chief, Halo 1)

In defense of the Naval Veterans Corps (Jackal Force).

Gene: Transition of fast breaker chemicals, to psychiatric nurses as waitresses; Yemen.

Marie: Transition of Israeli Defense Forces, to Cello's of Rhode Island, Italian-Catholic restauranting services.

Evelyn: Print of Hard Candy, new police film style for campus informant; successful, then a comedy romance, if a failure, then a police procedure drama (NKVD, the SVU model).

Danny: Discordianism, the militants as Jews; the shutdown of Canadian ATF, as Arab-Fenians; the transition of large American corporation, to grocers unions, held through pro-Jewish Rexism.

Roberta: WhatsBetter.Com, the CIA branching test of the singular prize fight, replaced by quadrants of four, the common identifier on a college campus of enemy.

Jimmy: "Pinkville", Salvo House; the clearing of Africans and Wiccan Lesbians, as responsible for beef poisonings; placing the blame on Hell's Angels instead, the arrests of witches under notoriety of Freemasons songs like those produced by "Electric Six" and other Canadian bands, and of the Hell's Angels and related biker groups; rich kid homosexuals.

Timmy: The Trump Assassination, carried out by Pat Ware, born for prison and ready for it; a Navy Star mother, forced to roleplay with combat spies and soldiers and cops, ready for his taste of bitch pussy; personally mentored, by "Stealth Fox", an Air Force Academy, befriended by "Chet", Air Force Reserve Office Training Corps, as an undercover operative.

Francis: The "Horatio Alger" proof of "Asperger's Syndrome", a new political family, the Moens; Ronnie Van Zant, and Chaucer, the Johnstons; Lynyrd Skynyrd returned to the South, for a new region and regime of African police officers.

Alice: The live hunt of enemies, as a soldier spy, and writer, stolen from under by permanent record Samson draws, fully aware of private writership career; the Metro-Goldwyn Mayer, as the top enemy of "Gutwill", his foe, "Wall-E", as Timothy O'Neill III, "Finding Nemo", and David as "Tickle-Me-Elmo", Timothy "Gutwill" O'Neill as Dave's number one Halloween costume, "Oscar the Grouch", "Superman".

youtube

0 notes

Text

Triple Helix Run ("Sullivan")

The Matrix: "Cypher".

Menino: Prison is resumed, to being priests on volunteer homeless shelter (the corrections officer, with the warden, a Resource Economics master's, no golf entire life, even mini-putt), watching cops (white people who beat someone up, in a uniform of any type) with black people that got beat up by the cop held for their lawsuit (they do the time as the felony offense beaten for, but with extra privilege, of being immune to violence or committing, in their own administration of union, without Yardies or MI-6 Marley fans).

Nixon: Police interceptor officers, are resumed to being heterosexual male, or heterosexual female, without surgeries, genital mutilation, or piercings anywhere on the body, to revert American police to Italian standards, without British interference (the Canondroga, the restaurant union for recipe exchanges). Police now invest in restauranting, through offering recipes, and receiving a preferential fee of payment for use of the recipe anywhere, impossible to pull, unless the food has been toyed with or poisoned, then the restaurant chain is cut off from sports patronage, even children's teams visiting, on the "Ron Goldman" case precedence, the buyout of "If I Did It" to the MLB Major League Baseball Chicago farm union; any American, illegal or citizen or convict, in a hospital, a prison, or dead, can no longer have a book about them, for publicist's profit, and is now subsidized out of the American arms manufacturing union, the Major League Baseball Pennant and World Series rig.

Garfield: Computer access algorithms into the police civics homes and centers, from the Waters Foundation, are now shut down, and permanently removed, taking Comcast Germany's influence through Pennsylvania, out of the Mossad, out of American policing, and such written films as nature, are now under American print industry regulation, of CIA mandate membership to produce any film, even student, featuring anything on the planet, video games and board games and sales of card decks as well. Therefore, nationalized publishing, is now the norm, and if it's the norm on subsidy law, of a corporate business law, it is the mandatory standard anywhere in the country, where a film is capable of being sold, bought, or viewed, outside of Reuters influence.

0 notes

Text

The European Parliament on Tuesday voted to approve the lifting of Greek MEP Eva Kaili’s immunity over a case in which she is accused of fraudulently misusing parliamentary allowances.

A European Anti-Fraud Office report raised suspicions that there was fraud involved in payments to accredited parliamentary assistants of Kaili, an MEP for the left-wing Greek PASOK party.

The head of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office, Laura Kovesi, then asked the president of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, to lift Kaili’s immunity. It also asked for the lifting of the immunity of Greek New Democracy MEP Maria Spyraki in the same case.

Kaili, the former vice-president of the European Parliament, asked the Court of Justice of the European Union to annul the requests for the lifting of her immunity.

But the Court of Justice rejected her request on January 16, stating that “the acts in question are not open to challenge” and that lifting the MEP’s immunity was necessary to ensure the investigation’s effectiveness.

Kaili is also the focus of the so-called ‘Qatargate’ scandal, accused of accepting bribes to promote the Gulf country’s interests in the EU.

Three other people, including her Italian partner, former Italian MEP Pier Antonio Panzeri, were accused in the same case. It was then revealed that Morocco and Mauritania had also bribed MEPs.

Initially Kaili remained in custody in a Brussels prison for more than four months. She was then released but was obliged to wear an electronic tracking bracelet and not allowed to leave Brussels.

However, she can now travel within countries in Europe’s passport-free Schengen Zone.

Although she was suspended by her leftist party, PASOK, and stripped of her position as vice-president of the European Parliament, she can still participate in the legislative process and other parliamentary activities as an independent MEP.

A trial over the Qatargate charges is pending.

1 note

·

View note

Text

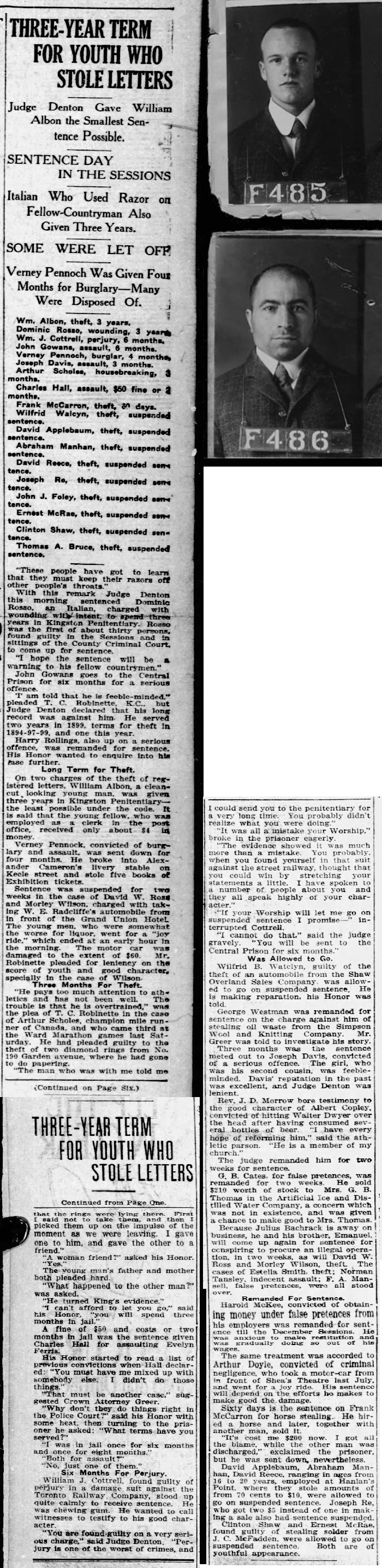

"THREE-YEAR TERM FOR YOUTH WHO STOLE LETTERS," Toronto Star. October 15, 1912. Page 1 & 6. ---- Judge Denton Gave William Albon the Smallest Sentence Possible. --- SENTENCE DAY IN THE SESSIONS ---- Italian Who Used Razor on Fellow-Countryman Also Given Three Years. --- SOME WERE LET OFF --- Verney Pennoch Was Given Four Months for Burglary - Many Were Disposed Of. ---

Wm. Albon, theft, 3 years.

Dominic Rosso, wounding, 3 years.

Wm. J. Cottrell, perjury, 6 months.

John Gowans, assault, 6 months.

Verney Pennoch, burglar, 4 months.

Joseph Davis, assault, 3 months.

Arthur Scholes, housebreaking, 3 months.

Charles Hall, assault, $50 fine or 1 months.

Frank McCarron, theft, 30 days.

Wilfrid Walcyn, theft, suspended sentence.

David Applebaum, theft, suspended sentence.

Abraham Manhan, theft, suspended sentence.

David Reece, theft, suspended sentence.

Joseph Re, theft, suspended sentence.

John J. Foley, theft, suspended sentence.

Ernest McRae, theft, suspended sentence.

Clinton Shaw, theft, suspended sentence.

Thomas A. Bruce, theft, suspended sentence.

"These people have got to learn that they must keep their razors off other people's throats."

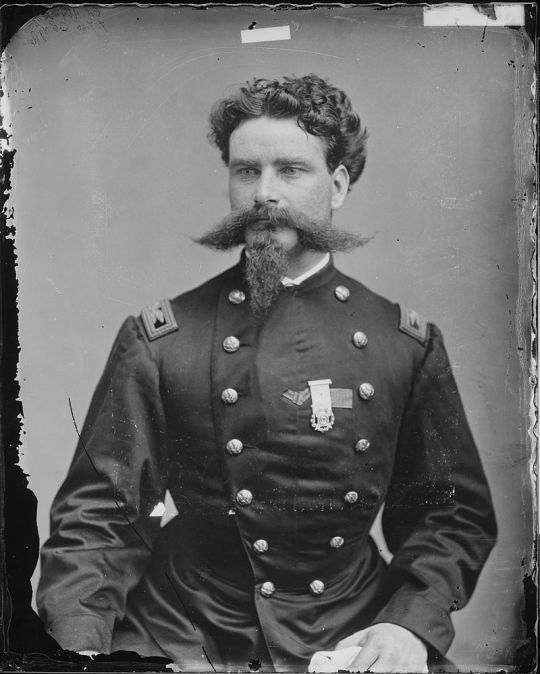

With this remark Judge Denton this morning sentenced Dominic Rosso, an Italian, [[pictured, top] charged with wounding with intent, to spend three years in Kingston Penitentiary. Rosso was the first of about thirty persons, found guilty in the Sessions and in sittings of the County Criminal Court, to come up for sentence.

"I hope the sentence will be a warning to his fellow countrymen."

John Gowans goes to the Central Prison for six months for a serious offence. 'I am told that he is feeble-minded," pleaded T. C. Robinette, K.C., but Judge Denton declared that his long record was against him. He served two years in 1899, terms for theft in 1894-97-99, and one this year. [Gowans would later be sentenced to the penitentiary in 1918...]

Harry Rollings, also up on a serious offence, was remanded for sentence. His Honor wanted to enquire into his case further.

Long Term for Theft. On two charges of the theft of registered letters, William Albon, a clean-cut, looking young man, was given three years in Kingston Penitentiary - the least possible under the code. It is said that the young fellow, who was employed as a clerk in the post office, received only about $4 in money.

Verney Pennock, convicted of burglary and assault, was sent down for four months. He broke into Alexander Cameron's livery stable on Keele street and stole five books of Exhibition tickets.

Sentence was suspended for two weeks in the case of David W. Ross and Morley Wilson, charged with taking W. E. Radcliffe's automobile from In front of the Grand Union Hotel. The young men, who were somewhat the worse for liquor, went for a "joy ride," which ended at an early hour in the morning. The motor car was damaged to the extent of $60. Mr. Robinette pleaded for leniency on the score of youth and good character, specially in the case of Wilson.

Three Months For Theft. "He pays too much attention to athletics and has not been well. The trouble is that he is overstrained," was the plea of T. C. Robinette in the case of Arthur Scholes, champion mile runner of Canada, and who came third at the Ward Marathon games last Saturday. He had pleaded guilty to the theft of two diamond rings from No. 190 Garden avenue, where he had gone to do papering.

"The man who was with me told me that the rings were lying there. First I said not to take them, and then I picked them up on the impulse of the moment as we were leaving. I gave one to him, and gave the other to a friend."

"A woman friend?" asked his Honor. "Yes."

The young man's father and mother both pleaded hard.

"What happened to the other man?" was asked. "He turned King's evidence."

"I can't afford to let you go," said his Honor, "you will spend three months in jail."

A fine of $50 and costs or two months in jall was the sentence given Charles Hall for assaulting Evelyn Ferris.

His Honor started to read a list of previous convictions when Hall declared: "You must have me mixed up with somebody else. I didn't do those things."

"That must be another case," suggested Crown Attorney Greer. "Why don't they do things right in the Police Court?" said his Honor with some heat, then turning to the prisoner he asked: "What terms have you served?"

"I was in jail once for six months and once for eight months."

"Both for assault?"

"No, just one of them."

Six Months For Perjury. William J. Cottrell, found guilty of perjury in a damage suit against the Toronto Railway Company, stood up quite calmly to receive sentence. He was chewing gum. He wanted to call witnesses to testify to his good character.

"You are found guilty on a very serious charge," said Judge Denton, "Perjury is one of the worst of crimes, and

"I could send you to the penitentiary for a very long time. You probably didn't realize what you were doing."

"It was all a mistake your Worship." broke in the prisoner eagerly.

"The evidence showed it was much more than a mistake. You probably, when you found yourself in that suit against the street railway, thought that you could win by stretching your statements a little. I have spoken to a number of people about you and they all speak highly of your character."

"If your Worship will let me go on suspended sentence I promise" interrupted Cottrell.

"I cannot do that" said the judge gravely. "You will be sent to the Central Prison for six months."

Was Allowed to Go. Wilfrid B. Watclyn, guilty of the theft of an automobile from the Shaw Overland Sales Company was allowed to go on suspended sentence. "He is making reparation," his Honor was told.

George Westman was remanded for sentence on the charge against him of stealing oil waste from the Simpson Wool and Knitting Company. Mr. Greer was told to investigate his story.

Three months was the sentence meted out to Joseph Davis, convicted of a serious offence. The girl, who was his second cousin, was feeble-minded. Davis' reputation in the past was excellent, and Judge Denton was lenient.

Rev. J. D. Morrow bore testimony to the good character of Albert Copley. convicted of hitting Walter Dwyer over the head after having consumed several bottles of beer. "I have every hope of reforming him," said the athletic parson. "He is a member of my church." The judge remanded him for two weeks for sentence.

G. B. Cates, for false pretences, was remanded for two weeks. He sold $210 worth of stock to Mrs. G. B. Thomas in the Artificial Ice and Distilled Water Company, a concern which was not in existence, and was given a chance to make good to Mrs. Thomas. Because Julius Bachrack is away on business, he and his brother, Emanuel, will come up again for sentence for conspiring to procure an illegal operation, in two weeks, as will David W. Ross and Morley Wilson, theft. The cases of Estella Smith, theft; Norman Tansley, indecent assault; F. A. Mansell, false pretences, were all stood over.

Remanded For Sentence. Harol Harold McKee, convicted of obtaining money under false pretences from his employers was remanded for sentence till the December Sessions. He was anxious to make restitution and was gradually doing so out of his wages.

The same treatment was accorded to Arthur Doyle, convicted of criminal negligence, who took a motor-car from in front of Shea's Theatre last July, and went for a joy ride. His sentence will depend on the efforts he makes to make good the damage.

Sixty days is the sentence on Frank McCarron for horse stealing. He hired a horse and later, together with another man, sold it. "It's cost me $200 now. I got all the blame, while the other man was discharged," exclaimed the prisoner, but he was sent down, nevertheless.

David Applebaum, Abraham Manhan, David Reece, ranging in ages from 16 to 20 years, employed at Hanlan's Point, where they stole amounts of from 70 cents to $10, were allowed to go on suspended sentence. Joseph Re, who got two $5 instead of one in making a sale also had sentence suspended.

Clinton Shaw and Ernest McRae, found guilty of stealing solder from J. C. McFadden, were allowed to go on suspended sentence. Both are of youthful appearance.

[AL: Albon was 17, born in Toronto, a first time offender, and was convict #F-485 at Kingston Penitentiary. He worked as a clerical assistant in a workshop, had no reports against him for breaking the prison rules, and was paroled in late 1913. Rosso was 29, born in Italy, a labourer on the docks, and had never been in the penitentiary before - he was convict #F-486 and worked in the quarry. He had no reports and was released in early 1915.]

#toronto#sessional court#wounding with intent#knife attack#stealing postal letters#postal clerk#theft#indecent assault#serious charge#illegal operation#perjury#joyriding#false pretences#burglary#history of canadian sports#sentenced to prison#kingston penitentiary#sentenced to the penitentiary#central prison#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#suspended sentence

0 notes

Text

youtube

Film about the Fascist abuses in 2001 Italy

Treatment of prisoners at Bolzaneto

Prisoners at the temporary detention facility in Bolzaneto were forced to say "Viva il duce."[15] and sing fascist songs: "Un, due, tre. Viva Pinochet!" The 222 people who were held at Bolzaneto were treated to a regime later described by public prosecutors as torture. On arrival, they were marked with felt-tip crosses on each cheek, and many were forced to walk between two parallel lines of officers who kicked and beat them. Most were herded into large cells, holding up to 30 people. Here, they were forced to stand for long periods, facing the wall with their hands up high and their legs spread. Those who failed to hold the position were shouted at, slapped and beaten.[16] A prisoner with an artificial leg and, unable to hold the stress position, collapsed and was rewarded with two bursts of pepper spray in his face and, later, a particularly savage beating.

Prisoners who answered back were met with violence. One of them, Stefan Bauer, answered a question from a German-speaking guard and said he was from the European Union and he had the right to go where he wanted. He was hauled out, beaten, sprayed with pepper spray, stripped naked and put under a cold shower. His clothes were taken away and he was returned to the freezing cell wearing only a flimsy hospital gown.

The detainees were given few or no blankets, kept awake by guards, given little or no food and denied their statutory right to make phone calls and see a lawyer. They could hear crying and screaming from other cells. Police doctors at the facility also participated in the torture, using ritual humiliation, threats of rape and deprivation of water, food, sleep and medical care.[17] A prisoner named Richard Moth was given stitches in his head and legs without anaesthetics, which made the procedure painful.

Men and women with dreadlocks had their hair roughly cut off to the scalp. One detainee, Marco Bistacchia was taken to an office, stripped naked, made to get down on all fours and told to bark like a dog and to shout "Viva la polizia Italiana!" He was sobbing too much to obey. An unnamed officer told the Italian newspaper La Repubblica that he had seen police officers urinating on prisoners and beating them for refusing to sing Faccetta Nera, a Mussolini-era fascist song.

Ester Percivati, a young Turkish woman, recalled guards calling her a whore as she was marched to the toilet, where a woman officer forced her head down into the bowl and a male jeered "Nice arse! Would you like a truncheon up it?" Several women reported threats of rape.[18] Finally, the police forced their captives to sign statements, waiving all their legal rights. One man, David Larroquelle, testified that he refused to sign the statements. Police broke three of his ribs for his disobedience.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wednesday, July 26, 2023

A legacy of unfairness (NYT) As the fight over affirmative action fades from the headlines, a large study released Monday shows that maybe the conversation around college admissions in the U.S. should focus on something else. The research, conducted by a group of Harvard-based economists named Opportunity Insights, shows that children from the top 1% financially are over twice as likely to attend America’s top colleges as their middle-class peers with the same SAT and ACT scores. “What I conclude from this study is the Ivy League doesn’t have low-income students because it doesn’t want low-income students,” said Susan Dynarski, a Harvard economics professor who wasn’t involved in the study but did take a look at the data. According to the study, colleges gave preference to legacy admissions (the children of alumni) as well as recruited athletes. Top colleges also gave higher non-academic ratings to students attending private (read: paid) schools over their peers attending public schools.

Ecuador declares state of emergency amid violent clashes (Reuters) Ecuador’s President Guillermo Lasso on Monday declared a state of emergency and night curfews in three coastal provinces, amid a wave of violence over the weekend in the Andean country that left at least eight people dead. Lasso declared the state of emergency in the provinces of Manabi and Los Rios and in the city of Duran, near Guayaquil, after Agustin Intriago, the mayor of coastal city Manta, was shot dead on Sunday. It also comes on the back of riots over the weekend in the prison Penitenciaria del Litoral, in Guayaquil, involving clashes between gangs inside the prison. Lasso has frequently resorted to declaring states of emergency as Ecuador struggles with prison riots and waves of violence throughout the country.

Southern Europeans splash out on air-con as heatwave drags on (Reuters) As Southern Europe battles extreme heat with no end in sight, people have rushed out to buy fans and even invest in air-conditioning to keep cool. In-built air-conditioning in homes is much less widespread in Europe than in the United States, making people reliant on more traditional ways of coping in the heat, like closing shutters and resting in the middle of the day. But data shows Italians and Spaniards are increasingly opting for more effective cooling solutions as summers get hotter. Italian consumer electronics retailer Unieuro, which has more than 500 shops across the country, said sales of air-conditioning products doubled in the week to July 21 compared to the same week last year. El Corte Inglés, one of Spain’s largest department store chains, said that by mid-July it had already sold 15% more units than it did last year by the end of August.

Greek Islands Wildfires (1440) Wildfires across three popular Greek islands have triggered what authorities consider to be the largest fire evacuation in Greece’s history, prompting roughly 32,000 tourists and residents to flee to safety as hundreds more await evacuations in gyms, schools, and hotel lobbies. No injuries have been reported. A heat wave across southern Europe and high winds have partly contributed to the spread of the wildfires in the islands of Rhodes, Corfu, and Evia, with temperatures expected to reach highs of between 107 and 111 degrees Fahrenheit today. Greece has seen roughly 600 fires over the last 12 days, or 50 new fires a day, officials said.

Poland’s population shrinking (AP) Poland’s population has shrunk again to just under 37.7 million in June despite returning emigrants, the state statistical office said Tuesday. A preliminary report by the Statistics Poland office says there were around 130,000 Poles fewer in the European Union country at the end of June compared to a year ago. It was among Poland’s highest decreases since 2010, when the population was over 38.5 million, despite a policy of bonuses for families with many children that the right-wing government launched after taking office at the end of 2015.

Putin appeared paralyzed and unable to act in first hours of rebellion (Washington Post) When Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner mercenary group, launched his attempted mutiny on the morning of June 24, Vladimir Putin was paralyzed and unable to act decisively, according to Ukrainian and other security officials in Europe. The Russian president had been warned by the Russian security services at least two or three days ahead of time that Prigozhin was preparing a possible rebellion, according to intelligence assessments shared with The Washington Post. Steps were taken to boost security at several strategic facilities, including the Kremlin, where staffing in the presidential guard was increased and more weapons were handed out, but otherwise no actions were taken, these officials said. “Putin had time to take the decision to liquidate [the rebellion] and arrest the organizers” said one of the European security officials. “Then when it began to happen, there was paralysis on all levels … There was absolute dismay and confusion. For a long time, they did not know how to react.” It appears to expose Putin’s fear of directly countering a renegade warlord who’d developed support within Russia’s security establishment over a decade. Prigozhin had become an integral part of the Kremlin global operations by running troll farms disseminating disinformation in the United States and paramilitary operations in the Middle East and Africa, before officially taking a vanguard position in Russia’s war against Ukraine. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov told The Post that the intelligence assessments were “nonsense” and shared “by people who have zero information.”

Russian expats boosting the economies of neighboring countries (Insider) Hundreds of thousands of Russians who fled their homeland following the country’s invasion of Ukraine have resettled in neighboring countries—and are boosting their economies. The exodus of Russians started after many highly educated professionals—such as academics, finance, and tech workers—left Russia in the early days of the war and after Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered a partial military mobilization for the Ukraine war on September 21. By October 2022, about 700,000 Russians had left the country, Reuters reported. Many of these Russians ended up in neighboring countries, setting up new lives and businesses, and ended up boosting the economies of these nations, the independent Russian media outlet Novaya Gazeta reported on Friday. The GDP of the South Caucasus—a region comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—grew by an outsized 7% in 2022, according to the World Bank. Armenia—once known as the Silicon Valley of the Soviet Union—saw its 2022 growth spike to 12.6%, per the World Bank. Meanwhile, Georgia’s GDP jumped by 10.1% in 2022, Kyrgyzstan’s economy grew by 7%, and Turkey, a hot spot for Russia fleeing the war, saw its economy grow 5.6% in 2022.

China’s labor challenge: Too many workers, not enough jobs (Washington Post) The sun is only just visible above the rooftops, but hundreds of job seekers are already getting restless in the 80-degree-and-rising morning. When a minivan that pulls up to the curb on a commercial street in Majuqiao, on the outskirts of Beijing, dozens charge at it. “What’s the gig?” they shout at the man inside, shoving forward in hopes of a payday and escape from the summer sun. The frantic scene—repeated again and again every morning here at an intersection where day laborers hope to pick up shifts—is testament to the bleak job prospects in the world’s second-largest economy. China’s economy is having more difficulty emerging from three years of zero-covid lockdowns than expected, with latest data showing growth remains sluggish. The property market and the construction work it generates, responsible for about a quarter of economic growth, is in decline. Consumption remains tepid as households are cautious about big purchases. Indebted local governments are flirting with defaults. Together these economic challenges have caused a big spike in joblessness, particularly among young people. The unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds hit a record 21 percent last month, although one economist thinks the real number may nearer to half.

China, Taiwan brace for their most powerful typhoon this year (Reuters) China urged fishing boats to seek shelter and farmers to speed up their harvest while Taiwan suspended annual military drills as super typhoon Doksuri spiralled closer to East Asia, potentially reaching deep into China. Doksuri will likely be the most powerful typhoon to land in China so far in the storm season this year. Nearly 1,000 km (620 miles) in diameter, Doksuri is expected to sweep past lightly populated islands off the northern tip of the Philippines by mid-week while fierce winds and heavy rain lash Taiwan to the north. Currently packing top wind speeds of 138 miles per hour (223 kph), Doksuri will make landfall on the Chinese mainland somewhere between Fujian and Guangdong provinces on Friday, China’s National Meteorological Center said on Tuesday. While Doksuri is expected to lose some power and land as either a typhoon or severe typhoon, it will still hammer densely populated Chinese cities with torrential rain and strong winds.

Sudan war enters 100th day as mediation attempts fail (Reuters) Clashes flared in parts of Sudan on the 100th day of the war on Sunday as mediation attempts by regional and international powers failed to find a path out of an increasingly intractable conflict. The fighting broke out on April 15 as the army and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) vied for power. Since then, more than 3 million people have been uprooted, including more than 700,000 who have fled to neighbouring countries. Some 1,136 people have been killed, according to the health ministry, though officials believe the number is higher. Neither the army nor the RSF has been able to claim victory, with the RSF’s domination on the ground in the capital Khartoum up against the army’s air and artillery firepower.

Short-Term Pain for Long-Term Gain? Nigerians Buckle Under Painful Cuts. (NYT) A teacher in northern Nigeria walks three hours to school every day, no longer able to pay for a ride in a tuk tuk rickshaw. Bakers operate at a loss amid soaring flour prices. Workers in Lagos sleep overnight in their offices to avoid the prohibitive cost of commuting. Since President Bola Tinubu of Nigeria was sworn in less than two months ago, he has shaken up his country with economic decisions that have been welcomed by investors and international backers, but been devastating to the livelihoods of many Nigerians. Now the question is whether Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, with 220 million people, will thrive or just get sicker from the bitter medicine dispensed by its new president. Mr. Tinubu set off shock waves when he announced during his inaugural speech on May 29 that he was ending a fuel subsidy that for decades had given Nigerians some of the cheapest oil in Africa, but amounted to a quarter of the country’s import bill. Gas stations tripled their prices overnight. Transportation fares, electricity and food prices followed. “It’s about short-term pain and long-term gain,” said Damilola Akinbami, a Lagos-based chief economist at Deloitte, a consulting firm. “Nigeria had reached a point where it was not if, but when it should remove the fuel subsidy.”

0 notes

Text

But Germany's military successes left it with the huge logistical problem of what to do with the men scooped up as it surged through Europe. Prisoners were not just British, Commonwealth and American but French, Polish and Dutch and – as countries changed sides – Italian and Russian. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the Germans took nearly three million soldiers prisoner in the first four months of fighting; by the end of the war she had nearly six million Russian prisoners. After the Italian Armistice in September 1943, Germany sent 60,000 of her former ally's troops to POW camps. Russian POWs were treated particularly badly and many British POWs are still haunted by memories of the starved and broken bodies they glimpsed through the barbed wire that separated the compounds. Like the Japanese, the Soviet Union had no sympathy for soldiers who had allowed themselves to be taken prisoner and these men (and some women) became non-persons. The Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention and Russian prisoners could expect no assistance from home. While German captors felt a cultural connection with the British men they captured, they had only distrust for the Russians. It was left to other POWs to lob their own precious supplies over the wire to help the starving Russians.

At the start of the war Germany had thirty-one POW camps; by 1945 this figure had risen to 248 – of which 134 housed British and American men. After Mussolini joined forces with Hitler in June 1940, men who were captured in North Africa were usually held in Italy and by the time Mussolini was overthrown and an armistice declared in September 1943 there were nearly 79,000 Allied prisoners in the country. By the end of the year, 50,000 had been taken to Germany and more, like the future travel writer, Eric Newby, who had spent some time on the lose, were later rounded up.

There was a huge diversity of architecture among camps that varied dramatically depending on the prisoner's rank, his escape record and whether or not he was made to work. Andrew Hawarden's first camp of Stalag XXA does not conform to either of the two most common stereotypes of a POW camp – the barbed wire, barrack huts and sentry posts of somewhere like Stalag Stalag Luft III, near Sagan (now Żagań) one hundred miles southeast of Berlin, which Paul Brickhill made famous through his book, The Great Escape, and Colditz, the glowing castle which many people still cannot think of without recalling the ominous music which accompanied the TV series of the same name

Most POW camps were nearer in design to Stalag Stalag Luft III, which was run by the Luftwaffe. In 1940 the German air force decided to build and control separate camps but they were quickly overwhelmed by the intensity of Allied bombing raids and many POW airmen ended up in military camps, albeit in separate compounds. My father's first camp, Stalag IVB, at Mühlberg, near Dresden, was built to hold 15,000 men but at its peak housed double this and included a large RAF contingent.

At first, naval and merchant-sailor prisoners were held at Stalag XB near the North Sea coast at Sandbostel until the German navy took control in 1942, when they were concentrated at a purpose-built site nearby at Westertimke. Naval POWs were held at two compounds (one for officers and the other for petty officers and senior ratings) at Marlag (an abbreviation of Marine Lager). Merchant seamen were held nearby at the larger camp of Milag (Marine-Interniertenlager).

— The Barbed-Wire University: The Real Lives of Allied Prisoners of War in the Second World War (Midge Gillies)

#book quotes#midge gillies#history#military history#aviation history#naval history#maritime history#prisoners of war#ww2#operation barbarossa#armistice of cassibile#germany#nazi germany#ussr#russia#italy#japan#britain#stalag luft iii#stalag iv-b#stalag x-b#marlag und milag nord#raf#royal navy#merchant navy (uk)#luftwaffe

0 notes

Text

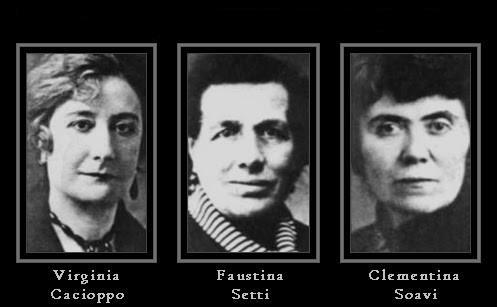

Keep Him Safe: The Awful Exchange of Leonarda Cianciulli

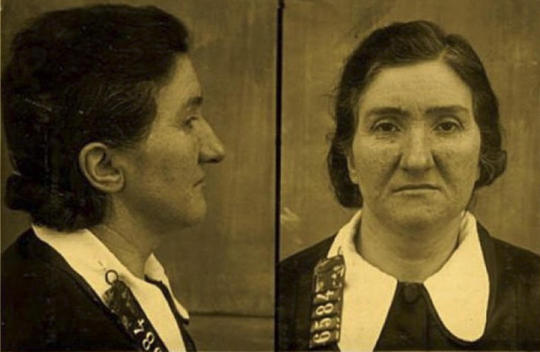

From early on Leonarda’s life was filled with tragedy and deep pools of darkness, but by the time she was forty-five years old it may have appeared like the bad years were behind her. According to all outward appearances she had four children that she adored, her family was freshly settled into a new home, she opened a small shop that proved to be successful, and she found friends in her neighbors. It seemed like there was very little to dislike about Leonarda. After all, she was friendly, generous, wise, and she was known to lend a helping hand to people chasing their dreams that reached far outside their town of Correggio. And then there were her baking. Her treats were enjoyed by many, but only because no one knew the truth about them.

Leonarda Cianciulli was born in Montella in the Kingdom of Italy on April 18th 1894. In her early life she attempted suicide twice before marrying a registry office clerk named Raffaele Pansardi in 1917. Cianciulli’s mother immediately disapproved of the union and there were already plans for Leonarda to marry someone else, but she refused. According to Leonarda’s memoir, the marriage to Pansardi caused her mother to put a curse on the pair before they moved to his hometown of Lacedonia. Some might say the curse was successful, between 1917 and 1939 Cianciulli became pregnant seventeen times and of the seventeen three were lost and ten of the children died at a very young age. In 1927 Cianciulli spent just over a year in prison for fraud after creating a fake account with a sizeable amount of money in a ledger at the bank where she worked as an evening cleaner. On July 23rd 1930 the Irpinia earthquake struck and totally destroyed her home forcing the family to relocate to Correggio. Looking for answers to all the turmoil in her life Leonarda sought the insight of at least one fortune teller. The news was not good, not only was she told all of her children would die young, but a palm reader also told her that "In your right hand I see prison, in your left a criminal asylum."

A scene of devastation after the Irpinia Earthquake. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

After moving to Correggio Leonarda seemed to have entered a new chapter in her life. The people of Correggio welcomed her and her family and she and Raffaele became well-liked by the townspeople. After a lifetime of broken connections and instability Leonarda quickly found herself in an unfamiliar position: having friends. There were dinner parties, casual visits with neighbors, and Leonarda was well respected for her wisdom, insight, wit, and skills. The extreme paranoia and anxiety she had developed over the course of her life may have actually started to dissipate while she started new hobbies like writing poetry. She even re-opened the little shop attached to her new home and became successful at selling her homemade goods like soap. But, like so many other times in her life, turmoil was coming.

When World War II broke out nearly four million Italians joined the military to serve their country and among them was Giuseppe Pansardi, Leonarda’s eldest and favorite child. For an obsessively over protective mother, the thought of losing a child on the battlefield could have been suffocating, but for the psyche of Leonarda it was absolutely catastrophic. She remembered that the fortune teller said all her children would die young and she had already lost thirteen of them. No matter what she had to do, she was not going to lose her son to war. The solution was clear to her; she would offer human sacrifices in exchange for his protection.

The first was Faustina Setti, a woman who often confided in Leonarda that she desperately wanted to find a husband. The confession wasn’t overly unusual, the seventy-six year old Faustina was good friends with Leonarda and the two saw each other on a regular basis. On one particular visit with her friend Faustina was met by a very excited Leonarda who had some astounding news for her, she found her a husband, a man in the city of Pula that she had been exchanging letters with. She sent him a photograph of Faustina and he immediately said that not only did he want to meet her, he wanted her to be his wife. All of this should have seemed bizarre to Faustina but she was so overcome with joy at the news of a husband that no questions or hesitation came to mind. Leonarda was thrilled for her friend and offered to plan the entire trip to Pula for her. But she had one very specific rule that Faustina had to follow. She told her to be careful, that friends and family would try to discourage her from going. In order to avoid any problems Leonarda instructed her to write a series of letters to them in advance, assuring them she was safe in Pula and very happy. Leonarda promised to mail them for her. It was all for the best. It was a total lie.

A later photograph of Leonarda. Image via https://horroresrevelados.wordpress.com/2017/03/20/leonarda-cianciulli-creaba-jabones-con-humanos/

On the morning of Faustina’s departure she went once again to Leonarda’s home. It was early, quiet, and Faustina was sitting at her friend’s table with shaking nerves and empty pockets. Leonarda had made her dreams come true, the least she could do was give her all of her life savings. As usual, Leonarda was there for her friend, she handed her a glass of wine to calm her nerves. It worked quickly. Faustina became calmer…and calmer…and her eyes and limbs got heavier…and heavier. We will never know if Faustina saw Leonarda approaching her with the ax. She thought she entered the home as a friend, she had no idea she was Leonarda’s first sacrifice.

Leonarda was accustomed to butchering animals and she used those skills to cut Faustina Setti’s body into nine pieces. Her body parts were put in a pot with over ten pounds of caustic soda. The chemical turned the remains into a thick dark sludge that Leonarda disposed of in a nearby septic tank. But then there was the blood, there was an entire basin of it. Leonarda waited until it coagulated before putting it in her oven to dry out. Once it was ready she ground it up. Then she got rid of it…along with some flour, sugar, chocolate, milk, eggs, and margarine. She kneaded the dried blood of Faustina into the dough and proceeded to make a batch of her famous tea cakes which she generously shared with her friends.

But was the sacrifice of Faustina enough to ensure the safety of her son?

By August of 1940 Francesca Soavi was in need of help. The former schoolteacher had quit her job to take care of her ill husband and when he died she was left with very little. Unable to find work she sought out Leonarda, after all she heard about how Leonarda had found Faustina a husband and made her dreams come true. Francesca met Leonarda and amazingly, she said that she was able to help. As luck would have it Leonarda knew of a school in the city of Piacenza, and they had a job opening. It was a very sought after position but Leonarda told her not to worry, she would make magic happen. Sure enough, a few weeks later Leonarda gave Francesca the happy news that she got the mystery dream job. All she had left to do was pack and write letters in advance to her friends and family telling them she was happy and safe. She would not even have to worry about mailing them, Leonarda’s son would take care of that for her.

On September 5th 1940 Francesca arrived at Leonarda’s home in the early morning just before she departed for Piacenza. She wanted to thank her once again for helping her find a job and getting her back on her feet. Leonarda handed her a celebratory glass of wine. Once again Leonarda’s guest started to feel weak and once again her host grabbed the ax. Francesca met the very same fate as Faustina with her broken down, liquified remains being tossed into the septic tank and her blood being baked into tea cakes. Leonarda’s second sacrifice was complete.

As Giuseppe’s departure date loomed closer Leonarda’s worry over if she had done enough to ensure his safety might have been unbearable. She needed to find another sacrifice but this time she did not have to look far. Virginia Cacioppo was a celebrity in Correggio. She was a former opera singer who once sang at the famed La Scala opera house in Milan and her friends and neighbors often heard her tales of lavish living so many years ago. Now after spending a number of years away from the spotlight she missed her former life and her close friend Leonarda was happy to help her. Before long Virginia had good news, Leonarda found her a job as a secretary for an impresario who organized the kind of artistic events that she was so familiar with and missed so dearly. She had to act quickly though, the job was in Florence and she had a lot to do before moving and re-igniting her life.

On the morning of September 30th 1940 Virginia was ready to go, but she could not leave without thanking her friend Leonarda for all of her amazing help. She brought along her belongings and, of course, the letters that Leonarda told her to write in advance that would be mailed later telling everyone about her wonderful new life in Florence. Leonarda offered her a glass of red wine.

Once Virginia was dead on the floor Leonarda started the process again. The body was cut into pieces…the blood was put in a basin to dry for tea cakes…but this time was slightly different. The previous two times Leonarda put the body parts and the caustic soda in the pots the experiment went totally wrong and her friends ended up in the septic tank. This time it worked, according to Leonarda when she recalled the visit later on:

“She ended up in the pot, like the other two...her flesh was fat and white, when it had melted I added a bottle of cologne, and after a long time on the boil I was able to make some most acceptable creamy soap. I gave bars to neighbors and acquaintances. The cakes, too, were better: that woman was really sweet.”

Image via https://horroresrevelados.wordpress.com/2017/03/20/leonarda-cianciulli-creaba-jabones-con-humanos/

Leonarda may have thought her third sacrifice was a success and further ensured the safety of her son, but with the killing of Virginia she made a very big mistake. Her two previous victims, Faustina and Francesca, had families that were located far from Correggio and did not have anyone close by to notice that something was amiss, especially when they were still receiving letters from them. This was not the case with Virginia, she had a sister-in-law in town named Albertina Fanti who did not believe for an instant that she had left to pursue a new job. It was more than a simple hunch that Virginia would not up and leave. It was the added fact that the last time she saw Virginia she was walking into Leonarda’s home and shortly after her disappearance her clothes started popping up for sale in Leonarda’s shop.

The accounts of how Leonarda was arrested vary with some saying Albertina had to go to the police in Reggio Emilia after the local police in Correggio dismissed her. Some say she was questioned more than once and it was only after a bank voucher belonging to Virginia was traced back to Leonarda that her home was searched. Others say the items that brought her down were the letters from the three women, all with a similar story and all mailed after they arrived at Leonarda’s home and “went away” to their bright new futures. Law enforcement might not have known what they were facing when they entered Leonarda’s home to question her, but they probably did not expect what happened. The five-foot-tall forty-six year old woman casually confessed to killing the three women, cutting them into pieces, turning their flesh into discarded sludge and admired soap, and baking their blood into tea cakes. Reports state that during one search of her property the septic tank was searched and inside was found small portions of bone showing evidence of the soap-making process and a denture of fourteen teeth matching the one worn by Faustina Setti.

Leonarda was arrested but she did not see the inside of a courtroom for six years while the war raged on and her son Giuseppe, her “miracle child” that she committed such horrors for, fought in the army. While in prison attempts were made to determine if she was actually a cold-blooded killer or if she was legitimately insane. One of the most renowned Italian psychiatrists, Director of the Criminal Asylum of Aversa, Filippo Saporito, undertook this task and asked Leonarda to write about her life. Several years later he was presented with a memoir that was almost 800 pages long and entitled Confessions of a Bitter Soul filled with everything from passages from the Gospels to the grisly details on how she turned the bodies of the three women into tea cakes and soap.

Mugshot of Leonarda Cianciulli. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

According to the Criminology Museum in Rome when the trial began not everyone was so sure Leonarda was the only person responsible for the crimes. These were no simple murders and doubt began to grow that she could have killed the women and done the dismembering of the corpses herself. With suspicion growing the eyes of the courtroom began to shift over to the only other person that they felt could have been involved, Giuseppe. When questioned about his role in the murders Giuseppe admitted to mailing the letters for his mother, but he said he did not know anything about them. With the accusations creeping closer toward her son Leonarda became aggressively adamant he was not involved in the killings, even telling the courtroom to bring her a fresh corpse from the morgue and she would show them all how she did it right then in there, “I cut here, here and here in less than 20 minutes everything was done, including cleaning. I might as well prove it now.”

Leonarda Cianciulli during her trail. Image via https://murderpedia.org/female.C/c/cianciulli-leonarda-photos-2.htm

As the examination continued it became clear that Leonarda was their only killer with her even correcting the prosecutor on the finer details of her crimes. She was matter-of-fact, candid, and completely without remorse. At one point telling the courtroom “I gave the copper ladle, which I used to skim the fat off the kettles, to my country, which was so badly in need of metal during the last days of the war...."

The trial of Leonarda Cianciulli only took three days and the verdict was no surprise to anyone. She was convicted of the murders and was sentenced to thirty years in prison and three years in a criminal asylum. According to a nun who knew Leonarda during her imprisonment she was a quiet, calm, prisoner making the welcome speeches to visiting ministers and spending her time crocheting, writing, and baking sweets that the other prisoners refused to eat.

The tools allegedly used by Leonarda in her crimes.

Images via https://murderpedia.org/female.C/c/cianciulli-leonarda-photos-2.htm and https://www.letturefantastiche.com/la_saponificatrice_di_correggio.html

Leonarda Cianciulli died in the asylum on October 15, 1970 at the age of seventy-six. Her body was returned to her family and buried in a common grave of a local cemetery.

Over eighty years after the murders there are still many questions about Leonarda Cianciulli, “The Soap-Maker of Correggio.” What made her believe the answer to her son’s safety was human sacrifice? Did she really do what everyone says? There are some that say it would have been impossible for her to turn the remains of the women into tea cakes and soap inside her own home, but others say the evidence is clear. Some question her own accounts of the murders and wonder if she exaggerated everything to convince the court she was insane in order to avoid the death penalty. A maid allegedly spoke up decades later about seeing the body parts hidden in parts of the house. There will forever be some details that remain foggy but what is absolutely certain is that three women walked into the home of Leonarda Cianciulli excited by the promise of a new life, they never left, and the only traces of them ever found were in the septic tank, exactly where Leonarda said they met their end. Also found in the home were a cauldron, an ax, a hammer, a hacksaw, a kitchen cleaver, and trace amounts of blood in multiple rooms of the house.

The cauldron, axes, hacksaw, and knives used by Leonarda were obtained by the Criminology Museum in Rome and remained on display until the museum’s closure.

Portion of the exhibit on Leonarda in the Criminology Museum in Rome (now closed.) Image via https://allthatsinteresting.com/leonarda-cianciulli

***********************************************************

Sources:

“Foreign News: A Copper Ladle" Time Magazine published June 24th 1946.

“How Serial Killer Leonarda Cianciulli Made Her Victims Into Soap And Teacakes” by Katie Serena. Published January 29, 2018. allthatsinteresting.com/leonarda-cianciulli

“Leonarda Cianciulli: The Serial Killer Who Turned Her Victims into Soap” by Dan Hendrix vocal.media/criminal/leonarda-cianciulli-the-serial-killer-who-turned-her-victims-into-soap

“WWII Serial Killer Mom Sacrificed Victims to Keep Her Son Safe at War” by Karen Harris historydaily.org/wwii-serial-killer-mom-sacrificed-victims-to-keep-her-son-safe-at-war/4

“The Cianciulli case” www.focus.it/cultura/storia/545745165-il-caso-cianciuli-32653

“Murder: Cianciulli case” www.museocriminologico.it/index.php/2-non-categorizzato/120-omicidi-caso-cianciulli2

The Deadly Soap Maker of Correggio by Genovena Ortiz. True Crime Explicit Volume 6. Sea Vision Publishing 2022.

#HushedUHistory#featuredarticles#history#ItalianHistory#CrimeHistory#LegalHistory#TrueCrime#FamousTrueCrime#horrorhistory#horrorstory#forgottenhistory#strangehistory#tragichistory#truehorror#sadhistory#scarystory#weirdhistory#shockinghistory#shockingstory#truth is stranger than fiction#scary#tragictale#terrifying#historyclass

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“A wave of popular unrest washed over Sicily at the close of the nineteenth century. In town after town, peasants mobilized labor strikes, occupied fields and piazzas, and looted government offices. While the island had a long history of revolt, this marked a new era of social protest. For the first time, women led the social movement and infused the struggle with their own mixture of socialism and spiritualism. The activity began in the autumn of 1892, in the towns surrounding Palermo, in the northwestern part of the island. In Monreale, women and children filled the central piazza shouting “Down with the municipal government! Long live the union!” After attacking and looting the offices of the city council, they marched toward Palermo crying “We are hungry!” waving banners with slogans connecting socialism to scripture. In Villafrati, Caterina Costanzo led a group of women wielding clubs to the fields where they threatened workers who had not joined the community in a general strike against the repressive local government. In Balestrate, thousands of women dressed in traditional clothes and also armed with clubs marched through the streets, demanding an end to government corruption. In Belmonte, Felicia Pizzo Di Lorenzo led fifty peasant women through the town and then gathered in the palazzo comunale, demanding the abolition of taxes, the removal of the mayor, and the termination of the city council. Three days later, when the crowd had grown to six hundred women and men, the mayor and his police broke up the demonstration and arrested the most vocal protestors. In Piana dei Greci, thirty- six women were arrested after they occupied and then destroyed the municipal offices, throwing the furniture into the streets. Soon after the uprising, close to one thousand women there formed a fascio delle lavoratrici (union of workers). The word fascio, “meaning bundle, or sheaf (as in sheaf of wheat),” in this case referred to “a sodality of peasants, miners, or artisans.” They celebrated the founding of the group as they would a religious festival, with music and food, and wove their political and spiritual ideologies together in their speeches. In the words of one woman, “We want everybody to work as we work. There should no longer be either rich or poor. All should have bread for themselves and their children. We should all be equal. . . . Jesus was a true socialist and he wanted precisely what we ask for, but the priests don’t discuss this.” News of the uprisings traveled quickly. Within days, government officials and newspaper reporters arrived from the mainland to witness the disturbances. Adolfo Rossi, a government official who would become the Italian commissioner of emigration, was one of the first to appear on the scene, and his observations circulated in the Roman newspaper La Tribuna in the fall of 1893. From Piana dei Greci, an epicenter of activity, he wrote: “The most serious sign is that the women are the most enthusiastic. . . . Peasant women’s fasci are no less fierce than those of the men.” In some areas, “women who were once very religious now believe only in their fasci,” and “in those areas where men are timid against authority, their wives soon convince them to join the movement of workers.” When the government accused the newly formed Italian Socialist Party of orchestrating the rebellion, party leader Filippo Turati argued that the movement was indigenous and rooted in popular solidarity: “The women, whose role in igniting the insurrection is well known, have abandoned the church for the fasci and it is they who incite their husbands and children to action.” The Italian government responded swiftly. On 3 January 1894, Prime Minister Francesco Crispi (a Sicilian himself) called for a state of siege and sent forty thousand military troops to the island to “contain the socialist threat.” Movement leaders and participants were arrested, beaten, and gunned down in the streets or executed in prison. Yet agitation continued to spread across the island and to the mainland. As popular unrest moved from the South to the North, women continued to play a critical role, leading street demonstrations and riots in small villages and towns throughout Calabria, Basiciliata (sic!), and Puglia and in the cities of Rome, Bologna, Imola, Ancona, Naples, Bari, Florence, Milan, and Genoa. Across Italy, workers in the emerging industrial cities joined with peasants to demand a complete restructuring of society based on socialist principles and filled streets chanting “Long Live Anarchy! Long Live Social Revolution!” In October, Crispi ordered the suppression of all socialist and anarchist groups. A four- year repressive campaign culminated in the fatti di maggio of 1898—the massacre of eighty demonstrators in Milan. By 1900 most of Italy’s peasantry and workers had experienced or heard of this kind of revolutionary struggle. It was inthis climate that mass emigration from Italy took place.”

Jennifer Guglielmo, Living the Revolution. Italian Women’s Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945, p. 9-11

#women#history#history of women#historical women#women in history#caterina costanzo#Felicia Pizzo Di Lorenzo#Francesco Crispi#contemporary sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.24 (after 1930)

Jews are forced to flee the city. 1931 – Resignation of the United Kingdom's Second Labour Government. Formation of the UK National Government. 1932 – Amelia Earhart becomes the first woman to fly across the United States non-stop (from Los Angeles to Newark, New Jersey). 1933 – The Crescent Limited train derails in Washington, D.C., after the bridge it is crossing is washed out by the 1933 Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane. 1936 – The Australian Antarctic Territory is created. 1937 – Spanish Civil War: the Basque Army surrenders to the Italian Corpo Truppe Volontarie following the Santoña Agreement. 1937 – Spanish Civil War: Sovereign Council of Asturias and León is proclaimed in Gijón. 1938 – Kweilin incident: A Japanese warplane shoots down the Kweilin, a Chinese civilian airliner, killing 14. It is the first recorded instance of a civilian airliner being shot down. 1941 – The Holocaust: Adolf Hitler orders the cessation of Nazi Germany's systematic T4 euthanasia program of the mentally ill and the handicapped due to protests, although killings continue for the remainder of the war. 1942 – World War II: The Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Japanese aircraft carrier Ryūjō is sunk, with the loss of seven officers and 113 crewmen. The US carrier USS Enterprise is heavily damaged. 1944 – World War II: Allied troops begin the attack on Paris. 1949 – The treaty creating the North Atlantic Treaty Organization goes into effect. 1950 – Edith Sampson becomes the first black U.S. delegate to the United Nations. 1951 – United Air Lines Flight 615 crashes near Decoto, California, killing 50 people. 1954 – The Communist Control Act goes into effect, outlawing the Communist Party in the United States. 1954 – Vice president João Café Filho takes office as president of Brazil, following the suicide of Getúlio Vargas. 1963 – Buddhist crisis: As a result of the Xá Lợi Pagoda raids, the US State Department cables the United States Embassy, Saigon to encourage Army of the Republic of Vietnam generals to launch a coup against President Ngô Đình Diệm if he did not remove his brother Ngô Đình Nhu. 1967 – Led by Abbie Hoffman, the Youth International Party temporarily disrupts trading at the New York Stock Exchange by throwing dollar bills from the viewing gallery, causing trading to cease as brokers scramble to grab them. 1970 – Vietnam War protesters bomb Sterling Hall at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, leading to an international manhunt for the perpetrators. 1981 – Mark David Chapman is sentenced to 20 years to life in prison for murdering John Lennon. 1989 – Colombian drug barons declare "total war" on the Colombian government. 1989 – Tadeusz Mazowiecki is chosen as the first non-communist prime minister in Central and Eastern Europe. 1991 – Mikhail Gorbachev resigns as head of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. 1991 – Ukraine declares itself independent from the Soviet Union. 1992 – Hurricane Andrew makes landfall in Homestead, Florida as a Category 5 hurricane, causing up to $25 billion (1992 USD) in damages. 1995 – Microsoft Windows 95 was released to the public in North America. 1998 – First radio-frequency identification (RFID) human implantation tested in the United Kingdom. 2001 – Air Transat Flight 236 loses all engine power over the Atlantic Ocean, forcing the pilots to conduct an emergency landing in the Azores. 2004 – Ninety passengers die after two airliners explode after flying out of Domodedovo International Airport, near Moscow. The explosions are caused by suicide bombers from Chechnya. 2006 – The International Astronomical Union (IAU) redefines the term "planet" such that Pluto is now considered a dwarf planet. 2016 – An earthquake strikes Central Italy with a magnitude of 6.2, 2016 – Proxima Centauri b, the closest exoplanet to Earth, is discovered by the European Southern Observatory. 2017 – The National Space Agency of Taiwan successfully launches the observation satellite Formosat-5 into space.

0 notes

Text

A beautiful late April day, seventy-two years after slavery ended in the United States. Claude Anderson parks his car on the side of Holbrook Street in Danville. On the porch of number 513, he rearranges the notepads under his arm. Releasing his breath in a rush of decision, he steps up to the door of the handmade house and knocks.

Danville is on the western edge of the Virginia Piedmont. Back in 1865, it had been the last capital of the Confederacy. Or so Jefferson Davis had proclaimed on April 3, after he fled Richmond. Davis stayed a week, but then he had to keep running. The blue-coated soldiers of the Army of the Potomac were hot on his trail. When they got to Danville, they didn’t find the fugitive rebel. But they did discover hundreds of Union prisoners of war locked in the tobacco warehouses downtown. The bluecoats, rescuers and rescued, formed up and paraded through town. Pouring into the streets around them, dancing and singing, came thousands of African Americans. They had been prisoners for far longer.

In the decades after the jubilee year of 1865, Danville, like many other southern villages, had become a cotton factory town. Anderson, an African-American master’s student from Hampton University, would not have been able to work at the segregated mill. But the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a bureau of the federal government created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, would hire him. To put people back to work after they had lost their jobs in the Great Depression, the WPA organized thousands of projects, hiring construction workers to build schools and artists to paint murals. And many writers and students were hired to interview older Americans—like Lorenzo Ivy, the man painfully shuffling across the pine board floor to answer Anderson’s knock.

Anderson had found Ivy’s name in the Hampton University archives, two hundred miles east of Danville. Back in 1850, when Lorenzo had been born in Danville, there was neither a university nor a city called Hampton—just an American fort named after a slaveholder president. Fortress Monroe stood on Old Point Comfort, a narrow triangle of land that divided the Chesapeake Bay from the James River. Long before the fort was built, in April 1607, the Susan Constant had sailed past the point with a boatload of English settlers. Anchoring a few miles upriver, they had founded Jamestown, the first perma- nent English-speaking settlement in North America. Twelve years later, the crews of two storm-damaged English privateers also passed, seeking shelter and a place to sell the twenty-odd enslaved Africans (captured from a Portuguese slaver) lying shackled in their holds.

After that first 1619 shipload, some 100,000 more enslaved Africans would sail upriver past Old Point Comfort. Lying in chains in the holds of slave ships, they could not see the land until they were brought up on deck to be sold. After the legal Atlantic slave trade to the United States ended in 1807, hundreds of thousands more enslaved people passed the point. Now they were going the other way, boarding ships at Richmond, the biggest eastern center of the internal slave trade, to go by sea to the Mississippi Valley.

By the time a dark night came in late May 1861, the moon had waxed and waned three thousand times over slavery in the South. To protect slavery, Virginia had just seceded from the United States, choosing a side at last after six months of indecision in the wake of South Carolina’s rude exit from the Union. Fortress Monroe, built to protect the James River from ocean-borne invaders, became the Union’s last toehold in eastern Virginia. Rebel troops entrenched themselves athwart the fort’s landward approaches. Local planters, including one Charles Mallory, detailed enslaved men to build berms to shelter the besiegers’ cannon. But late this night, Union sentries on the fort’s seaward side saw a small skiff emerging slowly from the darkness. Frank Baker and Townshend rowed with muffled oars. Sheppard Mallory held the tiller. They were setting themselves free.

A few days later, Charles Mallory showed up at the gates of the Union fort. He demanded that the commanding federal officer, Benjamin Butler, return his property. Butler, a politician from Massachusetts, was an incompetent battlefield commander, but a clever lawyer. He replied that if the men were Mallory’s property, and he was using them to wage war against the US government, then logically the men were therefore contraband of war.

Those first three “contrabands” struck a crack in slavery’s centuries-old wall. Over the next four years, hundreds of thousands more enslaved people widened the crack into a gaping breach by escaping to Union lines. Their movement weakened the Confederate war effort and made it easier for the United States and its president to avow mass emancipation as a tool of war. Eventually the Union Army began to welcome formerly enslaved men into its ranks, turning refugee camps into recruiting stations—and those African-American soldiers would make the difference between victory and defeat for the North, which by late 1863 was exhausted and uncertain.

After the war, Union officer Samuel Armstrong organized literacy programs that had sprung up in the refugee camp at Old Point Comfort to form Hampton Institute. In 1875, Lorenzo Ivy traveled down to study there, on the ground zero of African-American history. At Hampton, he acquired an education that enabled him to return to Danville as a trained schoolteacher. He educated generations of African-American children. He built the house on Holbrook Street with his own Hampton-trained hands, and there he sheltered his father, his brother, his sister-in-law, and his nieces and nephews. In April 1937, Ivy opened the door he’d made with hands and saw and plane, and it swung clear for Claude Anderson without rubbing the frame.1

Anderson’s notepads, however, were accumulating evidence of two very different stories of the American past—halves that did not fit together neatly. And he was about to hear more. Somewhere in the midst of the notepads was a typed list of questions supplied by the WPA. Questions often reveal the desired answer. By the 1930s, most white Americans had been demanding for decades that they hear only a sanitized version of the past into which Lorenzo Ivy had been born. This might seem strange. In the middle of the nineteenth century, white Americans had gone to war with each other over the future of slavery in their country, and slavery had lost. Indeed, for a few years after 1865, many white northerners celebrated emancipation as one of their collective triumphs. Yet whites’ belief in the emancipation made permanent by the Thirteenth Amendment, much less in the race-neutral citizenship that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments had written into the Constitution, was never that deep. Many northerners had only supported Benjamin Butler and Abraham Lincoln’s moves against slavery because they hated the arrogance of slaveholders like Charles Mallory. And after 1876, northern allies abandoned southern black voters.