#interlude 1957

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Interlude (1957)

#interlude#interlude 1957#douglas sirk#rossano brazzi#marianne koch#m#❤️🩹#great tapestries beautiful tapestries

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

interlude, douglas sirk 1957

#interlude#douglas sirk#1957#june allyson#rossano brazzi#marianne koch#françoise rosay#keith andes#le mépris#death of a salesman#heller wahn#about photography

0 notes

Text

Between 1957 and 1958, IT was known by the Losers Club to have killed 10 children. These included Georgie Denbrough, Betty Ripsom, Cheryl Lamonica, Matthew Clements, Veronica Grogan, Jimmy Cullum, Eddie Corcoran, Patrick Hockstetter, Victor Criss, and Belch Huggins. It is also implied that Chad Lowe, a 3-year-old boy, was killed by IT. What I have yet to see people discuss though is that in the First Interlude, Mike Hanlon says that in 1958 there were 127 reports of missing children ranging from ages 3 to 19. IT didn't just go after a few kids, it murdered a small school's worth. And as Mike Hanlon states, those were just the children whose disappearances were actually reported.

#it 1986#it 1990#it 2017#it 2019#it movie#it#syd says stuff#was just rereading the first interlude in the book to get a better feel for mike's character during the adult portion of the book#and i noticed this detail#also in 1930 there were over 170 reports of missing children#reading all of that really puts it into perspective though just how bad things were in derry

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosalind Russell - The Miracle Woman

Catherine Rosalind Russell (born in Waterbury, Connecticut on June 4, 1907) was an American actress known for playing sassy, wisecracking women in 1930s and '40s comedies. Despite going through postpartum depression, the deaths of her siblings, breast cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis, she thrived as a charismatic actress on film and the stage, earning the nickname "The Miracle Woman.”

Raised in a strict Irish-American, Catholic family. She attended Rosemont College and Marymount College, before graduating from the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, unbeknownst to her parents who believed she was studying to be a speech teacher.

Against parental objections, she began her career as a fashion model and took acting jobs in upstate New York, Connecticut, and Boston before eventually appearing in Broadway.

In 1933, Russell went to Los Angeles, where she was hired as a contract player for Universal Studios but did not appear in a movie. Unhappy at Universal, she moved to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where she broke through in the classic screwball comedy His Girl Friday (1940), directed by Howard Hawks.

She took a break after giving birth from her career, but made a comeback with RKO Pictures and then with Columbia Pictures. She continued to appear in critically acclaimed movies and Broadway shows through the mid-1960s, including the title role of the long-running stage comedy Auntie Mame (based on a Patrick Dennis novel) as well as the 1958 film version.

After years of battling breast cancer and even getting a double mastectomy, she died at her home in Beverly Hills, California at 69 years of age. Months after her death, she was honored by her acting colleagues with the “Interlude With Rosalind Russell” at the Shubert Theater in Broadway.

Legacy:

Nominated four times for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performances in My Sister Eileen (1942), Sister Kenny (1946), Mourning Becomes Electra (1947), and Auntie Mame (1958)

Won all five of her Golden Globe Award for Best Actress nominations: Sister Kenny (1946), Mourning Becomes Electra (1947), Auntie Mame (1958), A Majority of One (1961), and Gypsy (1962)

Won the 1953 Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for Wonderful Town and was nominated for the 1957 for Best Actress in a Play for Auntie Mame

Nominated for the 1959 BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress

Won the Golden Apple Award in 1942 for Most Cooperative Actress

Awarded the Look Magazine Award for Film Achievement Award in 1947

Covered Time magazine in 1953

Was the namesake of the Rosalind Russell State Theater in her hometown in 1955

Wrote the story for the film The Unguarded Moment (1956) and adapted the novel, The Unexpected Mrs. Pollifax, into the screenplay for Mrs. Pollifax-Spy in 1971, under the pen name C.A. McKnight

Won the Golden Laurel for Top Female Comedy Performance for Auntie Mame (1958) and was nominated five more times

Presented with a medallion by the National Conference of Christians and Jews in 1962

Honored for her distinguished service by the UCLA in 1964

Named the Woman of the Year by Hasty Pudding Theatricals, a student society at Harvard University, in 1964

Is the recipient of the Floyd B. Odlum Award by the Arthritis Foundation in 1971

Appointed by Congress to serve on the National Commission on Arthritis and Related Musculoskeletal Diseases during the 1970s

Received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1972

Appeared in John Springer's "Legendary Ladies" series at The Town Hall in 1973

Awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1973 by the Academy for her extensive charity work

Presented her with the National Artist Award in 1974 by the American National Theater and Academy

Awarded the Life Achievement Award in 1975 by the Screen Actors Guild Awards

Hosted by First Lady Betty Ford at the White House in 1976

Honored with the Rosalind Russell Week in 1977 by Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley

Co-authored her autobiography, Life Is a Banquet, in 1977

Is the namesake of the Rosalind Russell Medical Research Center for Arthritis at the University of California, San Francisco, created by a Congress grant in 1979

Inducted into the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame in 2005

Ranked #28 on Premiere magazine's 100 Greatest Performances of All Time in 2006 for His Girl Friday (1940)

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for July 2008

Inducted in the Online Film and Television Association Film Hall of Fame in 2014

Was the subject of a 2016 exhibit at the Mattatuck Museum in her hometown

Honored by the Berlin Film Festival‘s 27-movie tribute in 2022

Has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the 1700 block of Vine Street for motion picture

#Rosalind Russell#The Miracle Woman#Roz Russell#Auntie Mame#Silent Films#Silent Movies#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Classic Hollywood#Film Classics#Classic Films#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#Actress#hollywood actresses#hollywood icons#hollywood legend#movie stars#1900s

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

airsLLide No. 12755: N161FL, Convair 580, Contract Air Cargo, Pontiac, March 20, 1997.

N161FL was one of 21 Convair freighters operated by Contract Air Cargo out of Pontiac, Michigan. The carrier's main business case was overnight express freight services on behalf of the automotive industry in and around the greater Detroit area.

Incidentally, the automotive business dominated most of the service life of this particular Convair twin. Built as piston-powered Convair 440 in 1957, she was used as a corporate aircraft fitted with a VIP cabin from the very first day. Originally serving US Industries Inc., a major home and industry outfitter, she migrated to General Motors in 1963, after a brief interlude with business calculator manufacturer Victor Comptometer earlier the same year.

While in service for GM, she was converted to an Allison turbine powered Convair 580 in 1964. By year end 1974, she was traded to Ford Motor Co., where she served on until 1996 when IFL Group, the parent company of Contract Air Cargo, purchased her and converted her into a freighter. She was damaged beyond economical repair in a landing accident at McAllen Airport, TX, on December 4, 2004.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jane Wyatt and director Douglas Sirk during the making of INTERLUDE (1957)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

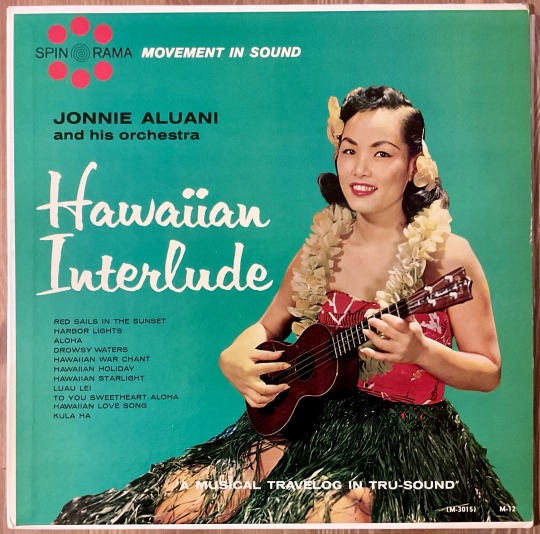

Jonnie Aluani And His Orchestra: Hawaiian Interlude (1957)

Front cover: shows title "Hawaiian Interlude"

Back cover: shows title "Hawaiian Interlude"

Labels: shows title "Hawaiian Holiday"

Artist listed is Jonnie Aluani and his Orchestra

on cover and label

Spinorama Records

#my vinyl playlist#jonnie aluani and his orchestra#spinorama records#hawaiian music#world music#folk music#50’s music#record cover#album cover#album art#vinyl records

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

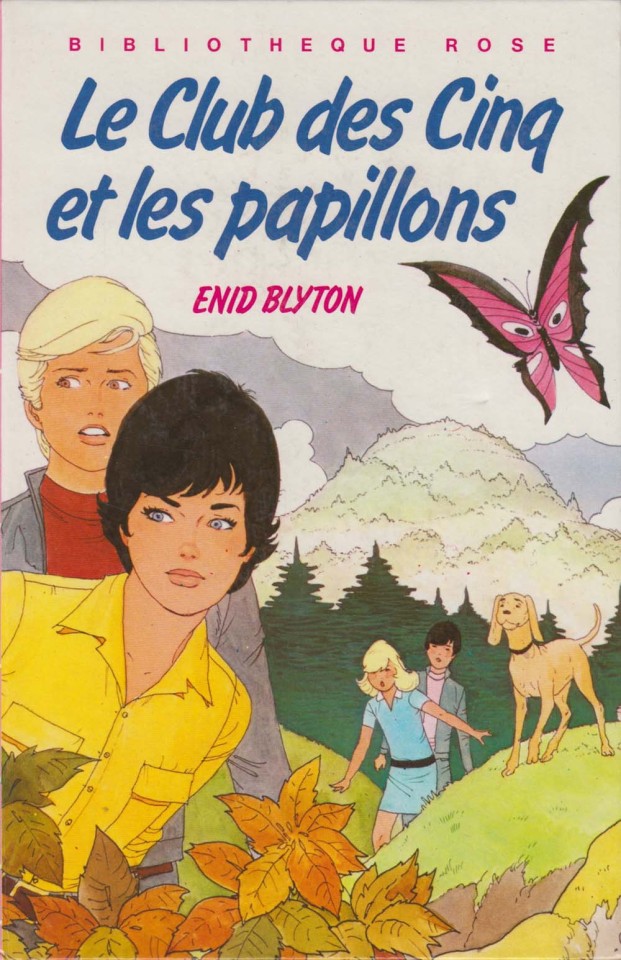

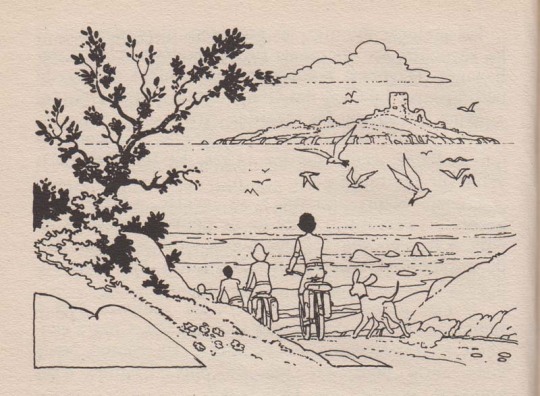

Famous Five Art Nostalgia #16 – Part 3

Introductory post

Masterpost

🛩️🦋🐷 Five Go to Billycock Hill – Le Club des Cinq et les papillons

Original publication date: 1957 (UK), 1962 (France)

(Cover art by Jean Sidobre, 1983)

Plot summary (adapted from Wikipedia):

The Five are camping on Billycock Hill, near the farm of Toby Thomas, a boy who goes to the same school as Julian and Dick and loves jokes and pranks. The Five meet Toby’s parents, who are very welcoming, as well as his little brother Benny, who never goes anywhere without his pet pigling Curly.

(Holiday planning!)

(Off to Billycock Hill)

(Five meet Toby’s adorable little brother, Benny – Timmy seems very intrigued by the little boy’s pet pigling, Curly 🐷)

(Poor little Benny is often the recipient to Toby’s practical jokes and pranks!)

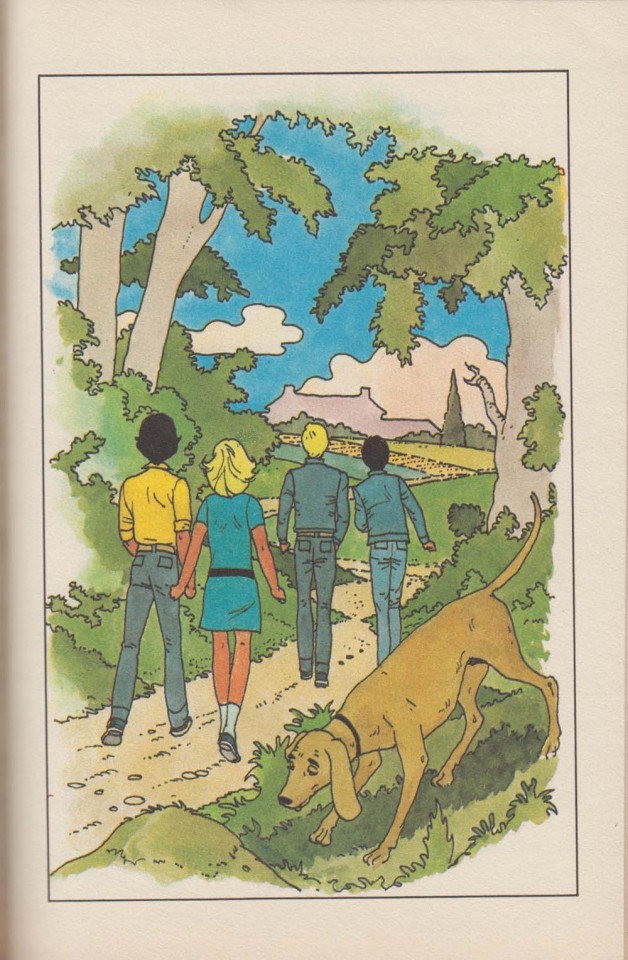

(On the way to find a nice camping place up Billycock Hill – Timmy’s heading the way along with Toby’s collie Binky [Clairon])

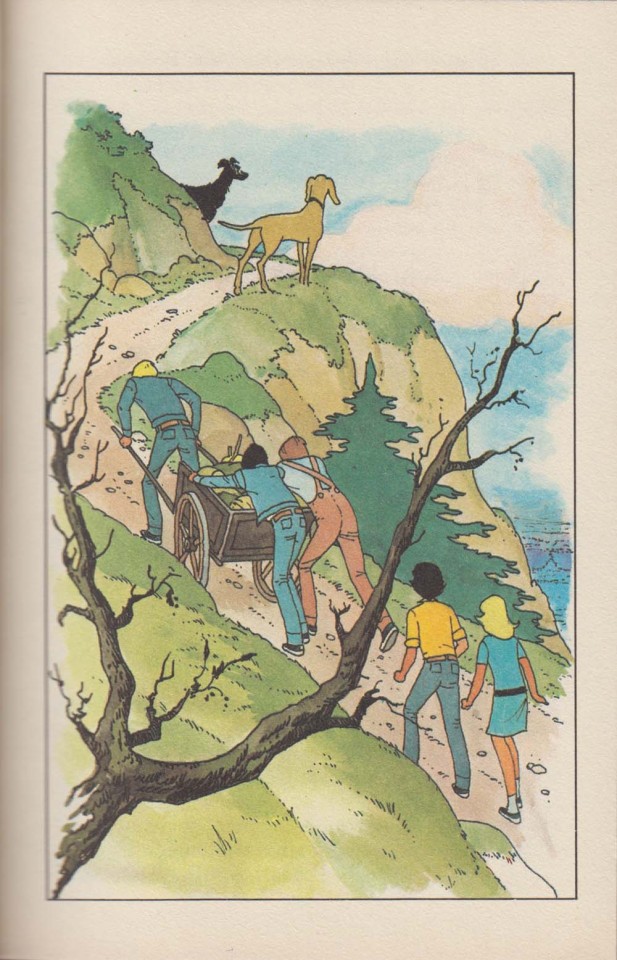

Toby is delighted with his visitors and wastes no time showing them around, such as leading them to a lovely pool where they can enjoy a refreshing swim, although they soon get told off by an Air Force officer for trespassing on military property. They also meet the eccentric Mr Gringle, one of the owners of a nearby butterfly farm, who gives them a visit.

(Meet Mr Gringle)

(Toby delights in practical jokes, in this case scaring the girls with a fake spider ��️)

(Toby brings the Five to a lovely pool, ignoring the “DANGER – KEEP OUT” sign in front of it… what could go wrong?)

Back to Billycock Farm, the Five meet Toby’s cousin Jeffrey, a flight-lieutenant at the neighbouring airfield.

(A zoological interlude: “Tea was now ready and they all drew up their chairs. Benny wandered in with his pigling 🐷 under his arm, and set it down in the cat’s basket, where it stayed quite peacefully, falling asleep and making tiny, grunting snores. / ‘Does the cat 😺 mind?’ asked George, astonished, looking at the basket. / ‘Not a bit,’ said Mrs Thomas. ‘It had to put up with two goslings 🪿🪿last year in its basket – and something the year before…’ / ‘A lamb 🐑,’ said Toby. / ‘Oh yes – and old Tabby – that’s the cat 🐈– didn’t seem to worry at all,’ said Mrs Thomas, pouring out creamy milk for everyone, even Cousin Jeff. ‘I once found her curled up round the goslings one morning, purring loudly.’”)

A big storm occurs that night, and the campers’ evening gets disturbed, first when they see Mr Gringle’s associate Mr Brent roaming the area, supposedly looking for moths, and then when Timmy puts up a fuss at seemingly nothing, before they all hear the sound of an aeroplane flying away.

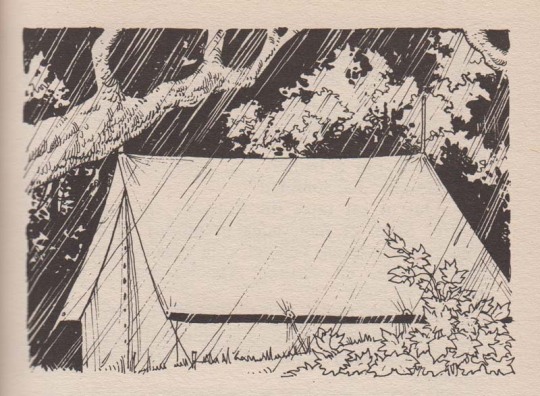

(A stormy night...)

(... really stormy!)

The weather is still rainy in the morning, so the Five decide to go visit a local tourist spot: Billycock Caves. At some point during their visit, they hear some horrible whistling noises that scare them away.

When they hear from the radio that Toby's cousin Jeff and a fellow pilot, Ray Wells, are reported to have defected and stolen the newest aeroplanes that were being developed at the airfield, the Five and Toby are shocked. The media later reports that Jeff and Ray crashed their planes and drowned at sea. Toby refuses to believe that Jeff was a spy.

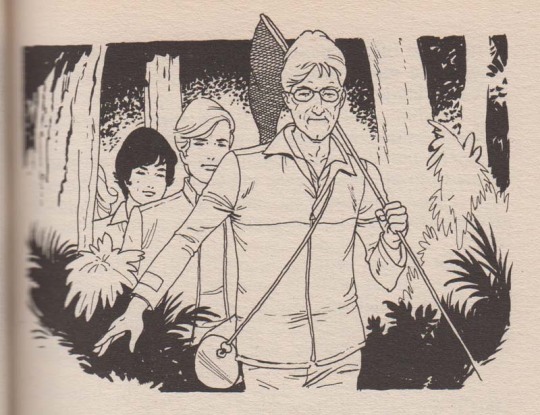

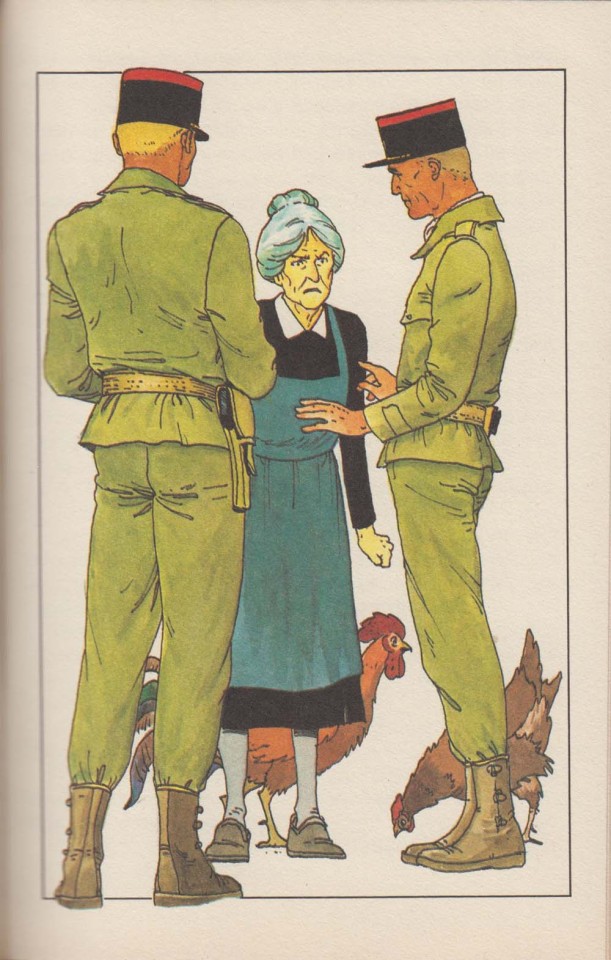

(The military police interrogate Mrs Janes, who works as a servant at the butterfly farm)

After poking around and talking to Mr Gringle, the children realise that the so-called “Mr Brent” whom they saw during the stormy night was an impostor, and that something fishy is going on at the butterfly farm. That night, Julian, Dick and Toby do some snooping around there.

(Investigators deep in discussion…)

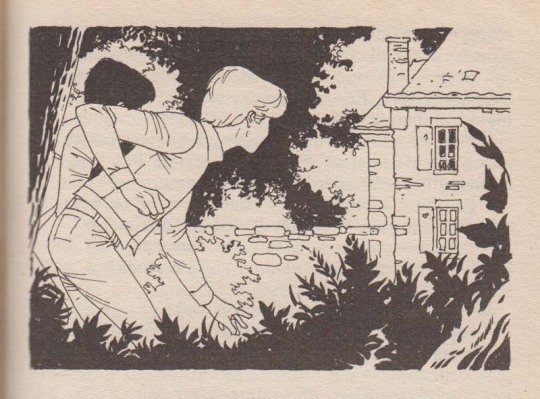

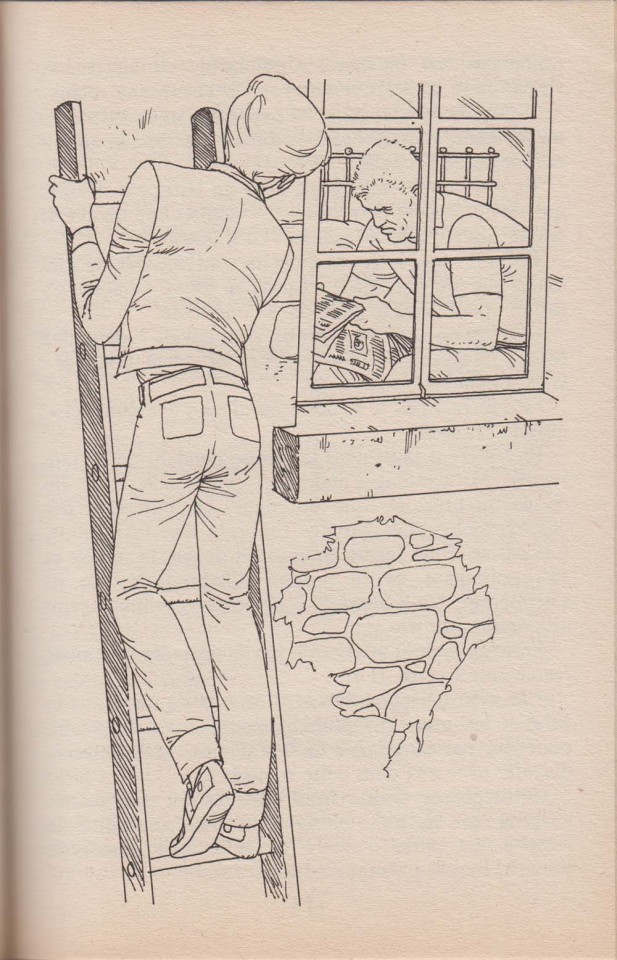

(Julian and Dick on a mission)

(Julian espies Mrs Janes’ son at the farm)

They learn from Mrs Janes, the house servant, that her layabout son Will has been hiding four men who have been watching the airfield day and night. The Five bring this information to Toby’s father, who gets in touch with the police, and it is confirmed that the two pilots who died were spies, but that Jeff and Ray are prisoners at an unknown location.

(Five on their way to Billycock Farm to bring news about their investigations)

As the Five attempt to comfort Toby while helping around at the farm, they realise that little Benny and his pigling have disappeared. They search for the missing pair all around the farm, and finally find Benny next to the entrance to Billycock Caves, upset that the pigling “runned away” inside the caves.

The pigling does find his way back to the farm on his own later on, with a message leading the children to find Jeff and Ray imprisoned in Billycock Caves. The prisoners are rescued and all ends well!

(Heroes of the day!)

~~~~~~

Thanks for reading!

#papillon82 reads#famous five art nostalgia#famous five#le club des cinq#enid blyton#illustrations#jean sidobre

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fannish Master Post

Since tumblr is a chaotic place I've decided to go ahead and make a master post of all the fics and other major fannish stuff I've posted on tumblr. As always you can head to FFN or AO3 and read the fics I've written over there. I've tried to present this list by fandoms and works in alphabetical order.

Avatar: The Last Airbender

Reflections of the Sun and Moon

Harry Potter

Interlude

Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel

Train to London

Star Wars

The Best Pilot in the Galaxy

Coarse Talk

The Thimblerig Plot

Mirrors (series)

Damaged Mirrors Scratched Mirrors Tarnished Mirrors

Star Wars: Rebels

Behind Her Beskar (chapters below)

Kanan's Secret 1, 2, 3, 4 At Home 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Safe and Sound 1, 2, 3, 4 Passing Moments 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Adjustments 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Family Matters 1, 2, 3, 4 Truth and Consequences 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Trials and Travails 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

A Bone to Pick

Feel You There

It's Good to be Home

Take My Hand (Take My Whole Life Too)

Days in the Wilderness (series)

This Day

You and Me Makes Us 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

X-Men

Graveside

Kitty's Unexpected Hanukkah Road Trip

Return More Than Echoes

Non-fic fannish stuff

Magneto: A Biographical Timeline, 1963-1991

When Magneto Became Romani

Zorro (1957)

A Coal Black Colt

Poinsettias for Maria

Non-fic fannish stuff

Disney's Zorro Episode 1 Transcript

#Fanfiction#Master Post#Fanfic#Zorro#X-Men#Star Wars#Star Wars: Rebels#Harry Potter#Avatar: The Last Airbender#ATLA#Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel#FFN#Fanfiction.net#AO3#Archive of Our Own#Zorro 1957#Disney's Zorro#Fandom Analysis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marianne Koch-June Allyson "Interludio de amor" (Interlude) 1957, de Douglas Sirk.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Let Dons Delight: Being Variations on a Theme in an Oxford Common Room’ (1939) by Rev Ronald Arbuthnott Knox. Traces of one Oxford Common Room over centuries, at interludes of 50 years each. Starts 1588 just before the Spanish Armada. And ends 1938 with WW II approaching when theology has been fully extruded from academia at Oxford. It is satire but also history. The zealous young dons become elderly Provosts asleep by the fire. Questions of church & state, Catholic vs. Protestant ideas, university politics, the changing role of the University. Occasional jabs at its rival Cambridge. I learned some very old words from the English language. The War Poet Siegfried Sassoon read this work 5 times. Knox later influenced the reception into the Church in 1957 of Sassoon his friend & neighbor at Mells, near Bath. Besides lecturing at Oxford on Logic, Homer, & Virgil, Knox was a leading Anglican High Churchman in demand as a preacher & a public speaker. His "Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes," first delivered to the Gryphon Club in 1911, was praised by Holmes' creator, Conan Doyle, as well as by the general public although his real purpose in the piece had been to satirize the German Biblical higher-criticism beginning to infect teachers as well as students of the Scriptures in England. After his conversion to Roman Catholicism he was appointed Chaplain to the Catholic undergraduates at Oxford (an office which his four post- Reformation predecessors had unofficially designated as Catholic Chaplain to the University). There he remained until 1939. In 1941 he was delighted at being elected an honorary Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford. When written Knox was preparing to leave Oxford after 12 years as the Roman Catholic chaplain. Combining wit, scholarship, jocularity, mimicry, and some argumentation betweenness the dons. Knox notes my earliest master & model for mimicry, G. K. Chesterton. https://www.instagram.com/p/CnnpTGFLy1o/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Country Upstairs by Colin Simpson Japan Today with a Philippine Interlude 1957 // autradingpost - shop

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday 🎂 🥳 🎉 🎈 🎁 🎊 To 1 Of The Legendary Black Actor Of The Golden Age Of Cinema 🎥 & He Has Been A Icon In Acting For More Then Several Decades

Born On January 17th, 1931

Born with a childhood stutter, He has said that poetry and acting helped him overcome the disability. A pre-med major in college, he served in the United States Army during the Korean War before pursuing a career in acting. Since his Broadway debut in 1957, he has performed in several Shakespeare plays including Othello, Hamlet, Coriolanus, and King Lear. He made his film debut in Stanley Kubrick's 1964 film Dr. Strangelove. He worked steadily in theater winning his first Tony Award in 1968 for his role in The Great White Hope, which he reprised in the 1970 film adaptation earning him Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations. He received his second Golden Globe Award nomination for his leading role opposite Diahann Carroll in the 1974 romantic comedy-drama film Claudine. He gained international fame for providing the voice of Darth Vader in the Star Wars franchise, beginning with the original 1977 film.

From Major Cultural Iconic Films 🎥

To STAR WARS, Coming To America, To The LION KING 🦁 🤴�� & MANY MORE

He been described as "ONE OF AMERICA'S MOST DISTINGUISHED AND VERSATILE" ACTORS for his performances in film, television, and theater, and "ONE OF THE GREATEST ACTORS IN AMERICAN HISTORY".

With a career spanning seven decades, He is among the few performers awarded an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony (EGOT). His voice has been praised as a "a stirring basso profondo that has lent gravel and gravitas" to his projects, including live-action acting, voice acting, and commercial voice-overs.

Please Wish Him

A Very Happy Birthday 🎂 🥳 🎉 🎈 🎁 🎊

May We All Gather Around And Honor Thos Legendary Black Man Of Highly Regarded Acting Of All Times

PRESENTING

THE 1

&

THE ONLY

MR. JAMES EARL JONES 🦁

LONG LIVE THE KING 🤴

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trouble With Writing About Vivian Maier

Biographers get distracted by the photographer’s unusual life story—to the point of diminishing her work itself.

Until 12 years ago, the photographer Vivian Maier was largely unknown. Though she shot incessantly from 1950 until about a decade before her death in 2009, she hid her pictures, literally locking them away. Often, she didn’t even bother to develop her rolls of film. She made money as a live-in nanny for families in New York and Chicago (briefly working for talk-show host Phil Donahue). As she got older, she rented storage lockers to house her overwhelming accumulation of books, magazines, newspapers, and other miscellany. The contents of those lockers were auctioned off in 2007 after she fell into arrears, which is how then-26-year-old John Maloof, a former art student, began purchasing the bulk of Maier’s archive: more than 140,000 images, most of them undeveloped and unprinted. A couple of years later, he uploaded some of the pictures to a street photography group on Flickr to immediate acclaim.

The images arrived already imbued with the aura of permanence. They sometimes evoke the wanderlust of Robert Frank’s photos, the wry self-deprecation of Lee Friedlander, or the grubbiness of Weegee, but they’re not derivative. Attentive to plaintive or absurd interludes in American life, primarily in New York City and Chicago, Maier made a piecemeal record of the sudden encounters and furtive gestures that turn any street into a guerrilla theater. She captured politicians on the campaign trail (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, LBJ); celebrities at premieres or out in the wild (Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn); laborers and commuters; drunks, criminals, and down-and-outs; flaneurs and well-coiffed women in furs. She cataloged the textures and cast-offs of the urban environment: graffiti, fire escapes, signs, garbage, shadows, abandoned newspapers, half-demolished buildings. She easily switched between registers, from gentle wit—as in a 1975 photo of an elderly trio crossing a Chicago street in rhyming yellow apparel, or a 1960s photo of an imperious dog loitering beneath a pay phone—to almost ethnographic sincerity, as in her photos from a six-month solo voyage around the world in 1959. She often photographed children, particularly when they were aggrieved or lost in adultlike introspection. Above all, she made images of casual lyricism, as in her celebrated 1957 photo of a woman in white drifting through a dark Florida night. Maier’s are the kinds of photos about which you can only say: These are the real deal.

The fact that Maier was dead by the time she became famous has proved a boon for her posthumous renown; in her absence, the mysteries around the photographer-nanny became irresistible hooks for editors and curators. Maloof has been entrepreneurial about marketing her story. At least half a dozen monographs have appeared in the last decade, bolstered by numerous exhibitions and a steady chorus of press. In 2015, Finding Vivian Maier, a documentary that Maloof co-directed, was nominated for an Oscar and burnished Maier’s legend further. If she’s not quite in the canon yet, she’s certainly wait-listed.

Maier has also been the subject of two notable biographies. The first, Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife, by Pamela Bannos, was released in 2016. The second, Vivian Maier Developed: The Untold Story of the Photographer Nanny, by Ann Marks, exemplifies the allure and risks of writing about the enigmatic Maier. Marks, a former marketing executive at Dow Jones, began to dig into Maier’s life after watching Maloof’s film. She kicks off her biography with a brassy sales pitch: “By book’s end, key questions will be answered, including the one everyone asks: ‘Who was Vivian Maier, and why didn’t she share her photographs?’ Mystery solved.”

Well, maybe, maybe not. Treating Maier like a riddle makes for good jacket copy but can also turn her into a kind of Rorschach: One sees in her whatever the critical mode du jour demands. Circa 2011, she was “the best street photographer you’ve never heard of,” to quote Mother Jones. Today, she is an aerosol of neuroses and quirks, the lonely spinster who shampooed with vinegar and slathered Vaseline on her face; who wore men’s size 12 shoes; who dumped drippings from a roast pan into a glass and drank them. As Marks describes Maier’s eccentricities, she starts to play the amateur clinician, marshaling hypotheses from medical experts whose secondhand diagnoses foreground a story of trauma and unwitting victimhood. Commercial publishers require a takeaway, and so Maier becomes here something she would have detested: an inspiration.

Maier is a tricky subject for a biographer. She spent the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s as a nanny, shuttling between families, or sometimes enjoying the reprieve of stable employment. (Her longest post was 11 years.) Whenever she moved, she locked her room and forbade anyone from entering. She seems not to have had romantic relationships, and had few personal ties. She left behind little by way of diaries or letters. Marks bases part of her portrait of Maier on the recollections of people who knew her glancingly, who remember her as an “extraterrestrial” figure. “She was … a very foreign presence in Highland Park,” recalls a friend of the Gensburgs, the family that employed Maier the longest. Marks’s physical rundown suggests why:

[Maier] dressed formally; her everyday attire consisted of a tailored suit or crisp Peter Pan–collared blouse paired with a calf-length skirt. She still wore old-fashioned rolled-down stockings, unable to make the transition to pantyhose. It was all covered up with oversize men’s coats in beiges and grays and topped with a trademark floppy hat.

Adding to the sense of foreignness was Maier’s brusqueness and penchant for French expressions. She presented a stern image that seemed at odds with the sensibility of her photos: The strict disciplinarian who insisted that her young charges address her as “Mademoiselle” and who sometimes slapped the children in her care also created a portfolio rife with humor and tenderness. More puzzling still, the woman who once traveled the world alone, who frankly espoused her opinions, and who seethed with ambition spent most of her adult life in the suburbs, anonymously plying her art. Marks begins her book with an epigraph of dichotomous terms acquaintances used to describe Maier, among them: Caring/Cold, Feminine/Masculine, Jovial/Cynical, Passionate/Frigid, Social/Solitary, Mary Poppins/Wicked Witch.

Despite her outward formality, a streak of playfulness runs through her photographs. In her more than 600 self-portraits, she finds ingenious ways to use mirrors and storefront windows to reflect her plain intensity, or else manifests as a kind of negative presence, as in more oblique shots of her shadow against sidewalks and walls. A self-portrait from the 1970s depicts her shadow against a laborer’s mud-spattered behind; another shows her shadow hovering amid a patch of buttercups (an image later used on a dress displayed in Bergdorf Goodman’s storefront). Other self-portraits are more direct: Maier reflected in a car mirror, her face neutral, aloof. According to Marks, Maier almost never let anyone else take her picture. How are we to understand these paradoxes?

In Marks’s telling, Maier inherited a split sense of self. Maier’s mother, Marie Jaussaud, was born in France in 1897, the illegitimate daughter of a teenage fling. “The baby girl was welcomed into a world where she officially didn’t exist,” Marks writes, noting that this shame “set into motion three generations of family dysfunction.” By 1919, Marie had immigrated to New York City, where she married an alcoholic steam engineer named Charles Maier. The couple gave birth to a son, Carl, in 1920, and to a daughter, Vivian, in 1926. The Maiers’ marriage was unhappy, and in 1932 Marie and Vivian fled to France, leaving young Carl behind. Mother and daughter returned to New York in 1938, where Maier eventually lodged with a widowed family friend, and found work in a doll factory (perhaps accounting for some later shots of dolls discarded in trash cans).

In 1950, Maier again returned to France. It was there she began taking photographs with a box camera: panoramas of the Alps, studies of the region’s working class, portraits of family. “It is clear from her early negatives and prints that Vivian possessed a great deal of confidence,” Marks writes. “She typically covered her subjects with just one shot, an approach that would become a trademark.” In the spring of 1951, Maier returned to New York, where she continued shooting, and even flirted with the idea of launching a picture postcard business. Most importantly, Maier revolutionized her practice by purchasing a Rolleiflex camera, which allowed her to literally shoot from the hip.

Marie almost entirely disappears from the biography after this point. “[She] stands out as disturbed and mentally unstable, even among a group of troubled individuals,” Marks writes of Maier’s mother. A doctor who examined the family records for this biography suggests that Marie had narcissistic personality disorder. She rarely held a steady job and was allergic to housework. She fabricated medical ailments, and in a letter to an officer about Carl’s care, she strikes a paranoid tone, lamenting that everyone had “plotted against” her. Although Marks acknowledges that it’s impossible to accurately diagnose Marie, this doesn’t stop her from premising the whole biography on such drive-by psychologizing. Indeed, the book is a case study for what responsible biographers shouldn’t do.

Some of Marks’s theories are more credible than others. It’s likely, for example, that Maier was a hoarder. By the time she died, she had crammed more than eight tons of possessions into storage lockers. (Her hoarding cost her at least one nanny job.) At other times, though, Marks’s hypotheses are purely speculative. “Physical and sexual abuse can contribute to trauma,” she writes, “and Vivian’s behavior suggests that she may have endured this type of exploitation.” The behavior in question—Maier’s distaste for physical intimacy, her fusty wardrobe, and her cautioning young girls against sitting on men’s laps—doesn’t strike me as compelling evidence of childhood sexual abuse so much as the traits of a reserved woman with old-fashioned notions of propriety. “[Maier’s] brother was definitively diagnosed with schizophrenia, and her mother almost certainly had a history of some sort of mental illness,” Marks writes. “Many felt Vivian’s grandfather Nicolas Baille may have also, based on his antisocial behavior and extreme paranoia.” (Marks doesn’t specify whom she means by “Many.”) She asks the same doctor who diagnosed Maier’s mother to take a crack at Maier herself. The verdict: Maier was perhaps a “classic case of schizoid disorder.”

Marks uses the fact of Carl Maier’s schizophrenia to prop up this diagnosis. One of the assets of her largely lackluster biography is the gumshoe work she does chasing down Carl’s records and filling in his story. (The book’s multiple appendixes, including one devoted to “genealogical tips,” suggests that building out a family tree is Marks’s real passion.) Carl was imprisoned at age 16 for tampering with the mail and forging a check. He joined the military but was dishonorably discharged for a drug-related offense. He bounced in and out of psychiatric hospitals as an adult and died of an aortic thrombosis at a rest home in 1977, at age 57. He and Maier had little contact with each other, although Marks portrays them as heirs to a common bloodline of mental illness. Marks takes Carl’s diagnosis at face value, despite how often the label schizophrenia was slapped onto criminalized bodies at mid-century, particularly among institutionalized drug users. Still, let’s grant that Carl had some kind of genetic psychological disturbance—what does that mean for Maier?

It means that her creativity, her art, is inextricable from mental illness. That’s a generic enough argument, but in Marks’s hands, it turns cloying. Her interpretations of Maier’s work sometimes take unfortunate cues from clinical analyses. She quotes a father-son duo of Freudian therapists who posit that “the negative themes that surface in Vivian’s portfolio—including death, violent crime, demolition, and garbage—represent subconscious reflections of her low self-esteem.” Name any worthwhile photographer—any worthwhile artist—and you’ll encounter “negative themes.” This is vapid psychoanalysis and even worse critical writing.

As I read, I was increasingly irritated by this reductive and patronizing portrayal of Maier. (This is underscored by how Marks refers to Maier as “Vivian.” “I use her first name throughout because this is how most people know and speak about her,” Marks writes by way of explanation. She doesn’t consider that Maier, who worked in a service capacity all of her life, was unlikely to be addressed by her surname.) “With immense strength of character and perseverance,” Marks writes, “Vivian developed compensatory qualities and coping mechanisms, like photography, to manage her mental health issues.” In Marks’s account, Maier is a mentally ill woman who took photos almost as a therapeutic tic rather than a full-fledged artist with (perhaps) a mental illness. Maier’s self-portraits, according to Marks, are simply ways to substantiate herself in the world—signposts of a woman who was forever unmoored. Even Maier’s prolificness is evidence of a compulsion, as if her taking pictures was of a piece with her hoarding of newspapers. Marks never considers that perhaps Maier just enjoyed being a photographer, and that the act of framing a shot was itself creatively fulfilling. Would anyone point to a writer’s pile of false starts and trashed drafts as signs of a mental disorder?

Just because Maier often didn’t develop her rolls of film and rarely produced prints (and almost never exhibited them) doesn’t mean that her creative practice was somehow stunted or insular. That’s a careerist view of how a photographer should operate. Maier was undoubtedly a serious, dedicated, and consummate artist, largely self-taught, who honed her craft over decades. As Marks herself notes, Maier was more than a hobbyist, even from the beginning: “Altogether, the thousands of early images … confirm how intensely Vivian worked to master the basics of photography during her time in [France].” In New York, Maier sought out “colleagues to learn from, collaborate with, and engage in shoptalk.” She assiduously cropped images and experimented with color film. Even by the end of her career, Maier was known to leave precise instructions for the technicians entrusted with developing her images. But by pressing her into a queasy Hallmark narrative of a woman triumphing over her demons, Marks’s biography unintentionally undervalues Maier’s achievement. Photography wasn’t a “coping mechanism” but her life’s work.

“I’m sort of a spy,” Maier once told someone who asked about her profession. She was being cheeky, but the remark indicates how she saw herself: as a witness and a trespasser, a woman interested in momentary revelations of truth, no matter how painful or embarrassing or fraught. Her photographs represent a vast album of American street life across five decades, and, parallel to that, a chronicle of Maier’s own place in that landscape. It’s a body of work that’s simultaneously objective and subjective, in which Maier is both the author and a recurrent, ambiguous protagonist who lends the entire undertaking a kind of self-referential weight. Contrary to Marks’s argument, I see no meaningful distinction between the photographer and the world in Maier’s work. She doesn’t appear to me as an isolated woman trying to fix her coordinates in a universe from which she was somehow estranged. She looks, instead, like a woman who was profoundly and intuitively present.

If you read enough biographies, you realize that the genre has a fatal flaw, a system error: Every person is unknowable, not least of all to themselves. There is, in everyone, some small cinder of truth that never sees the light of day. Biographers pretend that this cinder can be revealed, and that order can be imposed upon an unruly life. That’s a lie. Ann Marks hasn’t solved the mystery of Maier—why would we want her to? The photographer’s mystery remains intact, suffusing the thousands of indelible images she left behind in those storage lockers. It’s better to look there for the truth of her life, in those pictures of the world that she put away, as if she saw, and understood, what the rest of us never would. ~ Jeremy Lybarger · Dec 21, 2021.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#ProyeccionDeVida

🎥🎼 La Música en el Cine, presenta:

🎬 “INTERLUDIO DE AMOR” [Interlude]

🔎 Género: Romance / Drama / Remake / Melodrama

⌛️ Duración: 90 minutos

✍️ Guión: Franklin Coen, Daniel Fuchs, Dwight Taylor e Inez Cocke

📕 Historia: James M. Cain

🎶 Música: Frank Skinner

📷 Fotografía: William H. Daniels

🗯 Argumento: Helen Banning es una joven estadounidense que llega a Europa para ocupar un puesto de bibliotecaria en la Casa de América de Munich. Gracias a una serie de circunstancias conoce a Tonio Fischer, un famoso director de orquesta, con quien inicia una relación.

👥 Reparto: June Allyson (Helen Banning), Rossano Brazzi (Tonio Fischer), Keith Andes (Dr. Morley Dwyer), Marianne Koch (Reni Fischer), Françoise Rosay (Countess Reinhart), Jane Wyatt (Prue Stubbins), Frances Bergen (Gertrude Kirk), Herman Schwedt (Henig), Lisa Helwig (Housekeeper) y John Stein (Dr. Stein).

📢 Dirección: Douglas Sirk

© Productora: Universal International Pictures (UI)

🌏 País: Estados Unidos

📅 Año: 1957

📽 Proyección:

📆 Sábado 25 de Mayo

🕚 11:00am.

🏪 Sala Azul del Centro Cultural PUCP (av. Camino Real 1075 San Isidro)

⭐ Organiza: Sociedad Filarmónica de Lima

🚶♀️🚶♂️ Ingreso libre

0 notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

LA MUSIQUE AU SERVICE DU CHANGEMENT SOCIAL : CHARLIE HADEN

Né le 6 août 1937 à Shenandoah, en Iowa, Charles Edward Haden avait grandi dans un environnement musical. La famille Haden aimait beaucoup la musique et jouait de la musique country et du folk sur les ondes de la radio KMA sous le nom de Haden Family. Charlie a d’ailleurs fait ses débuts professionnels comme chanteur sur l’émission de radio de sa famille alors qu’il avait seulement deux ans. Charlie chantait aussi du yodle, ce qui lui avait mérité le surnom de ‘’Yodle Charlie.’’ Charlie avait continué de chanter avec sa famille jusqu’à l’âge de quinze ans lorsqu’il avait été atteint d’une forme de poliomyélite qui avait paralysé ses cordes vocales.

Charlie était âgé de quatorze ans lorsqu’il avait commencé à s’intéresser au jazz après avoir entendu Charlie Parker jouer dans l’orchestre de Stan Kenton. Après avoir recouvré la santé, Charlie avait commencé à étudier la contrebasse. L’intérêt de Charlie pour la contrebasse était loin d’être limité au jazz, puisqu’il se passionnait aussi pour les harmonies et les cordes qu’il avait entendues dans les compositions de Jean-Sébastien Bach. Déterminé à s’installer à Los Angeles afin de devenir musicien de jazz, Haden avait décidé de se trouver un emploi afin de financer son déménagement. Haden se fit éventuellement embaucher comme bassiste-maison à l’émission ‘’Ozark Jubilee’’ qui était diffusée l’antenne du réseau ABC à Springfield, au Missouri.

LA NAISSANCE DU FREE JAZZ

Haden avait souvent déclaré qu’il était déménagé à Los Angeles en 1957 afin de rencontrer le pianiste Hampton Hawes. Après avoir refusé une bourse du Oberlin College (celui-ci ne disposait pas de programme de jazz à l’époque), Haden s’était inscrit au Westlake College of Music à Los Angeles. Haden avait fait ses débuts sur disques avec le pianiste Paul Bley. Les deux musiciens avaient travaillé ensemble jusqu’en 1959. Haden avait aussi collaboré avec Art Pepper durant quatre semaines en 1957.

En 1958-1959, Haden avait enfin réalisé son rêve de jouer avec Hampton Hawes. Haden avait rencontré Hawes par l’entremise de son ami, le contrebassiste Red Mitchell. Pendant un certain temps, Haden avait partagé un appartement avec un autre contrebassiste, le légendaire Scott LaFaro. En mai 1959, Haden avait enregistré un album au titre prophétique, ‘’The Shape of Jazz To Come’’, avec le quartet du saxophoniste Ornette Coleman. D’une certaine façon, les influences folk d’Haden étaient complémentaires des influences blues de Coleman. Plus tard la même année, le quartet de Coleman avait déménagé ses pénates à New York où il avait décroché un contrat de six semaines au Five Spot Café. C’est lors de cette période cruciale que le free jazz était né.

Les musiciens du quartet de Coleman jouaient tout par oreille, car aucune pièce n’était écrite. Comme Haden l’avait expliqué plus tard:

“At first when we were playing and improvising, we kind of followed the pattern of the song, sometimes. Then, when we got to New York, Ornette wasn’t playing on the song patterns, like the bridge and the interlude and stuff like that. He would just play. And that's when I started just following him and playing the chord changes that he was playing: on-the-spot new chord structures made up according to how he felt at any given moment.”

En 1960, Haden, qui avait développé une dépendance envers les narcotiques, avaient dû se retirer du quintet de Coleman. En septembre 1963, Haden s’était fait désintoxiquer dans les différentes branches de Synanon House à Santa Monica et à San Francisco, en Californie. C’est durant son séjour à Synanon House que Charlie avait rencontré sa première épouse, Ellen David. Le couple s’est installé dans le quartier Upper West Side de New York où leurs quatre enfants étaient nés. Vint d’abord un fils, Josh, né en 1968, puis des triplettes, Petra, Rachel et Tanya. Charlie et Ellen s’étaient séparés en 1975 et avaient divorcé un peu plus tard.

En 1984, Haden avait rencontré la chanteuse et ancienne actrice Ruth Cameron. Le couple s’était marié à New York. En plus de devenir la gérante d’Haden, Ruth avait co-produit plusieurs de ses projets avec lui. Le couple était demeuré ensemble jusqu’à la mort d’Haden en 2014.

Après avoir repris sa carrière en 1964, Haden avait travaillé avec le saxophoniste John Handy et le trio du pianiste Denny Zeitlin. Il avait aussi joué avec Archie Shepp en Californie et en Europe. En 1966-1967, Haden avait collaboré avec Henry ‘’Red’’ Allen, Pee Wee Russell, Attila Zoller, Bobby Timmons, Tony Scott et le Thad Jones|Mel Lewis Orchestra. Après avoir enregistré avec Roswell Rudd en 1966, Haden était retourné jouer avec le groupe de Coleman l’année suivante. Le groupe avait poursuivi ses activités jusqu’au début des années 1970. Le quartet de Coleman avait sans doute cruellement ressenti l’absence de Haden, car celui-ci était connu pour savoir lire dans les intentions de Coleman dont la musique était dans la plupart des cas improvisée et non écrite.

De 1967 à 1976, Haden était devenu membre du trio du pianiste Keith Jarrett et de son ‘’American Quartet’’ formé du batteur Paul Motian, du saxophoniste Dewey Redman et du percussionniste Guilherme Franco. Haden avait aussi été un des membres fondateurs en 1976 du collectif Old and New Dreams, avec Don Cherry, Dewey Redman et Ed Blackwell, tous des anciens membres du groupe de Coleman. Le collectif devait son nom au fait qu’il jouait des compositions de Coleman en plus de ses propres compositions.

LE LIBERATION MUSIC ORCHESTRA

En 1970, sur la recommandation du chef d’orchestre Leonard Bernstein, Haden avait obtenu une bourse de la Guggenheim Fellowship for Music Composition. Au fil des années, Haden avait d’ailleurs reçu plusieurs prix de composition.

Ce n’est qu’en 1969 qu’Haden avait fondé son premier groupe, le Liberation Music Orchestra, avec la pianiste et arrangeuse Carla Bley. La version originale du groupe était composée de Haden, de Bley, des saxophonistes Gato Barbieri et Dewey Redman, des trompettistes Don Cherry et Mike Mantler, du batteur Andrew Cyrille, du joueur de trombone Roswell Rudd, de Bob Northern (au cornet et au tuba), d’Howard Johnson (au tuba et au saxophone basse), du clarinettiste Perry Robinson et du guitariste et luthiste Sam Brown.

Comme son nom l’indique, la musique de l’orchestre était expérimentale, et explorait tant les frontières du free jazz que de la musique traditionnelle ou politiquement engagée. Le premier album de l’orchestre traitait de la guerre civile espagnole. Cette dernière avait particulièrement marqué Haden. Charlie, qui avait été inspiré par la turbulente convention du Parti démocrate de 1968 à Chicago, avait superposé des pièces comme ‘’You’re a Grand Old Flag’’ et ‘’Happy Days are Here Again’’ à des morceaux traditionnels comme ‘’We Shall Overcome’’ (Nous vaincrons).

Un si grand nombre de musiciens avaient collaboré avec le Liberation Music Orchestra qu’il était devenu avec le temps un véritable ‘’who’s who’’ du jazz. Les membres de l’orchestre provenaient aussi souvent d’horizons culturels différents, reflétant ainsi les préoccupations internationalistes de Haden pour l’avenir de la planète. Parmi les autres musiciens qui avaient fait partie de l’orchestre, on remarquait les noms d’Ahnee Sharon Freeman et de Vincent Chancey au cor français, de Tony Malaby et de Chris Cheek au saxophone ténor, de Miguel Zenon au saxophone alto, de Joseph Daley au tuba, de Seneca Black et de Michael Rodriguez à la trompette, de Curtis Fowlkes au trombone, de Steve Cardenas à la guitare et de Matt Wilson à la batterie. L’orchestre s’était mérité plusieurs prix en 1970, plus particulièrement en France, où il avait remporté le Grand Prix du Disque de l’Académie Charles Cros, et au Japon, où il avait décroché le Gold Disc Award décerné par le Swing Journal.

Haden était en tournée avec Ornette Coleman au Portugal (ce pays vivait alors sous une dictature militaire) en 1971 lorsqu’il avait dédicacé sa pièce ‘’Song for Che’’ aux révolutions anticolonialistes qui avaient lieu dans les colonies portugaises de Mozambique, d’Angola et de Guinée. Le lendemain, Haden avait été arrêté à l’aéroport de Lisbonne, mis en prison et interrogé par la police secrète portugaise, la DGS. Hadem n’avait été libéré qu’après que Coleman et les autres musiciens aient porté plainte devant l’attaché culturel américain. À son retour aux États-Unis, Haden avait été interrogé par le FBI.

La dédicace de Haden n’était certainement pas innocente. Haden avait décidé de fonder le Liberation Music Orchestra au milieu de la guerre du Vietnam, car il était furieux que son gouvernement consacre autant de temps, d’argent et d’énergie à faire la guerre alors qu’il faisait face à plusieurs problèmes sociaux sur son propre sol comme la pauvreté, la lutte pour les droits civils, les problèmes de santé mentale, la dépendance face aux narcotiques ou le chômage. Le but de Haden en fondant le Liberation Music Orchestra était de s’en servir comme moyen d’expression des peuples opprimés qui n’avaient souvent pas de voix pour se faire entendre. Haden voulait aussi exprimer sa solidarité envers les mouvements politiques progressistes à travers le monde en jouant une musique qui encourageait le changement social.

L’album de 1982 ‘’The Ballad of the Fallen’’, publié sur l’étiquette ECM, avait de nouveau abordé la guerre civile espagnole, tout en dénonçant l’intervention américaine en Amérique latine. Le Liberation Music Orchestra avait fait d’importantes tournées à travers le monde durant les années 1980 et 1990. En 1990, l’orchestre était retourné en studio pour enregistrer ‘’Dream Keeper’’. La pièce-titre, qui était basée sur un poème de Langston Hughes, faisait aussi appel à la musique gospel américaine et à la musique sud-africaine afin de dénoncer le racisme aux États-Unis et le système d’Apartheid toujours en vigueur en en Afrique du Sud. Le Oakland Youth Chorus participait également à l’album. En 2005, l’orchestre avait enregistré un quatrième album intitulé ‘’Not In Our Name’’, une protestation contre l’invasion et l’occupation américaine en Irak.

Grand pédagogue, Haden avait aussi fondé en 1982 le Jazz Studies Program au California Institute of the Arts à Valencia, en Californie. Ce programme, qui mettait particulièrement l’accent sur les petites formations, insistait particulièrement sur le caractère spirituel de la création artistique. Il encourageait aussi les étudiants à découvrir leur propre son et à développer leurs propres mélodies et harmonies. Haden avait éventuellement été élu ‘’Jazz Eductation of the Year’’ par la Los Angeles Jazz Society pour son implication dans le programme. Les étudiants d’Haden à Valencia comprenaient le fils de John Coltrane, le saxophoniste ténor Ravi Coltrane, le trompettiste Ralph Alessi, ainsi que le pianiste et compositeur James Carney et le contrebassiste Scott Colley.

DES COLLABORATIONS DIVERSIFIÉES

À la suggestion de son épouse Ruth, Haden avait formé en 1986 le groupe Quartet West. L’alignement original du groupe était composée d’Ernie Watts au saxophone, d’Alan Broadbent au piano et de Billy Higgins à la batterie. Higgins, un collaborateur de longue date d’Haden, avait été remplacé plus tard par Laurance Marable. Lorsque Marable était devenu trop malade pour performer, le batteur Rodney Green avait été ajouté à la formation. En plus des compositions d’Haden et de Broadbent, le répertoire du groupe comprenait des ballades populaires des années 1940 qui avaient été réinterprétées dans un style bop. Une brève collaboration avec le saxophoniste ténor Joe Henderson et le batteur Al Foster avait aussi contribué à replacer le groupe d’Haden dans un contexte plus jazz. En 2010, le quartet avait enregistré l’album ‘’Sophisticated Ladies’’, qui mettait en vedette des chanteuses issues à la fois du jazz, de la musique classique et de la musique populaire. En tout et pour tout, le quartet a enregistré quatre albums de 1987 à 1993.

Déterminé à conduire le Quartet West jusqu’au prochain millénaire, Charlie avait écrit sur son site web: "We have developed an intuitive sense musically and spiritually. Just like the Modern Jazz Quartet, we've developed a sound that has come from playing together for a long time." Lorsque le quartet avait enregistré ‘’The Art of Song’’ en 1999, Charlie avait déclaré: "I wanted to gather together a collection of complete melodies that tell a story in the music and the lyric and that have rarely been recorded. Plus, I wanted them to be sung by vocalists who are masters at exploring the depth of a song. I'd always hoped to work with Shirley [Horn] and Bill [Henderson], who are both singers who perform at the creative level of Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker."

En 1989, Haden avait inauguré la série ‘’Invitation’’ du Festival international de jazz de Montréal avec une série de huit concerts mettant en vedette des musiciens qu’il avait lui-même choisis. Les concerts avaient été enregistrés et furent publiés plus tard dans un coffret intitulé ‘’The Montreal Tapes.’’ En 1994, Ginger Baker, le batteur légendaire du groupe rock Cream, avait fondé le Ginger Baker Trio avec Haden et le guitariste Bill Frisell.

Haden a souvent joué en duo, car il adorait l’intimité procurée des petites formations. En 1995, Haden avait enregistré l’album ‘’Steal Away: Spirituals, Hymns and Folk Songs’’ avec le vétéran pianiste Hank Jones. Le disque était basé sur des chansons de gospel traditionnelles et sur des chansons folkloriques. En plus de jouer sur l’album, Haden avait également agi comme producteur. À la fin de 1996, Haden avait collaboré avec le guitariste Pat Metheny dans le cadre de l’album ‘’Beyond the Missouri Sky’’. Sur ce disque, les deux musiciens avaient exploré la musique qui avaient influencé leurs enfances respectives en Iowa et au Missouri. Haden a remporté le premier prix Emmy de sa carrière pour sa participation à l’album dans la catégorie de la meilleure performance de jazz instrumentale. Ce n’était d’ailleurs pas la première fois qu’Haden collaborait avec Metheny, puisqu’il avait participé notamment à l’enregistrement des albums ‘’80|81’’ et ‘’Rejoicing’’, un album en trio avec le batteur Billy Higgins enregistré en 1984 et mettant en vedette les compositions d’Ornette Coleman.

En 1997, le compositeur classique Gavin Bryars avait écrit un adagio spécialement destiné à Haden. Intitulée ‘’By the Vaar’’, la pièce comprenait une instrumentation diversifiée incluant notamment des cordes, une clarinette basse et des percussions. La pièce avait été enregistrée avec l’English Chamber Orchestra et avait été incluse sur un album intitulé ‘’Farewell to Philosophy’’ (Adieu à la Philosophie). L’adagio était une sythèse de jazz et de musique de chambre et imitait le jeu d’Haden à la contrebasse. En 2001, Haden avait remporté un Latin Grammy Award pour le meilleur CD de jazz latin. Le prix lui avait été remis pour son album ‘’Nocturne’’ qui contenait des boléros de Cuba et du Mexique. Deux ans plus tard, Haden s’était mérité un second Latin Grammy Award pour la meilleur performance de jazz latin sur son album ‘’Land of the Sun.’’

Haden avait reformé le Liberation Music Orchestra en 2005 pour l’enregistrement de l’album ‘’Not In Our Name’’ réalisé sur étiquette Verve. L’album, qui avait été enregistré principalement avec de nouveaux musiciens, abordait surtout la situation politique aux États-Unis sous les gouvernements de Ronald Reagan, de George Bush Sr. et de George Bush Jr.

En 2008, Haden avait co-produit avec son épouse Ruth Cameron Haden l’album ‘’Charlie Haden Family and Friends : Rambling Boy.’’ Comme son titre l’indique, l’album mettait en vedette des membres de la famille immédiate d’Haden. Parmi ceux-ci, on retrouvait son épouse Ruth Cameron, ses trois filles musiciennes, les triplettes Petra, Tanya et Rachel, son fils Josh, et le mari de sa fille Tanya, le chanteur et multi-instrumentiste Jack Black. Le banjoéiste Béla Fleck, les guitaristes Vince Gill, Pat Metheny, Elvis Costello et Rosanne Cash, et le claviériste Bruce Hornsby participaient à l’album avec d’autres musiciens importants de Nashville. Le disque avait permis à Haden de faire revivre l’époque où il jouait de la musique country sur l’émission de radio de ses parents. L’idée d’enregistrer ce genre d’album était venue à Charlie lorsque sa femme Ruth avait réuni la famille Haden pour le 80e anniversaire de naissance de sa mère et avait suggéré de chanter la chanson ‘’You Are My Sunshine’’ dans le salon. L’enregistrement de l’album avait aussi pour but de rapprocher les différentes générations de la famille Haden. Le disque comprenait des chansons popularisées par les frères Stanley, la famille Carter ainsi que par Hank Williams, en plus de chansons traditionnelles et de compositions originales.

En 2009, le réalisateur de cinéma suisse Reto Caduff avait produit un film sur la vie d’Haden intitulé ‘’Rambling Boy.’’ Le film avait été présenté au Festival du film de Telluride et au Festival international du film de Vancouver en 2009. À l’été 2009, Haden avait retrouvé son ancien partenaire Ornette Coleman au festival de Meltdown à Southbank, près de Londres. Au cours de cette période, Haden a aussi produit et enregistré des albums en solo avec le pianiste Kenny Barron, avec qui il avait enregistré l’album ‘’Night and the City.’’ En février 2010, Haden et le pianiste Hank Jones avaient collaboré dans le cadre de la production de l’album ‘’Come Sunday’’, une sorte de suite au disque ‘’Steal Away : Spirituals, Hymns and Folk Songs.’’ Jones est mort trois mois après l’enregistrement de l’album.

En plus de souffrir de la poliomyélite depuis son plus jeune âge, Haden avait de fréquents acouphènes, une maladie qu’il avait attribué à une exposition constante à la batterie et au son élevé des concerts auxquels il avait participé à la fin des années 1960. On avait découvert plus tard qu’Haden souffrait d’hyperacusis, une hyper-sensibilité au bruit qui l’obligeait à placer un Plexiglass entre lui et le batteur. Charlie Haden est mort à Los Angeles le 11 juillet 2014 à l’âge de soixante-seize ans. Les causes de sa mort ont été attribuées à un syndrome post-polio et à des complications consécutives à une maladie du foie. Il laissait dans le deuil sa femme Ruth, son frère Carl Jr., sa soeur Mary Davidson, ses enfants Josh, Petra, Rachel et Tanya, ainsi que trois petits-enfants.

On a rendu hommage à Charlie Haden lors d’un concert tenu au New York City's Town Hall le 13 janvier 2015. Le concert avait été produit et organisé par sa femme Ruth. Haden avait su transmetre sa passion de la musique à ses enfants. Le fils de Charlie, Josh Haden, est bassiste et chanteur du groupe Spain. Ses filles Petra, Tanya et Rachel Haden, sont toutes trois chanteuses et instrumentistes. Petra joue du violon et Rachel joue du piano et de la basse électrique. Quant à Tanya, qui est artiste visuelle, elle joue du violoncelle. Les trois soeurs, qui se produisent dans un groupe surnommé The Haden Triplets, ont enregistré un album éponyme en 2012. Le comédien, acteur et musicien Jack Black est le gendre de Tanya.

Charlie Haden a remporté de nombreux honneurs au cours de sa carrière, dont un Jazz Masters Award. En 2013, la carrière d’Haden avait été couronnée par la remise d’un Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. Haden a aussi été reconnu‘’Jazz Master’’ par la National Endowment for the Arts en 2012. En 2014, Haden avait également été nommé Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres par le ministre de la Culture de France. Une cérémonie posthume en son son honneur avait eu lieu en janvier 2015 à New York.

En septembre 2014, trois mois après la mort de Charlie, les disques Impulse, qui venaient de renaître de leurs cendres, avaient publié l’album ‘’Charlie Haden-Jim Hall’’, un enregistrement de son concert en duo de 1990 au festival international de jazz de Montréal. Même s’il était mourant, Haden avait contribué à la réalisation de l’album. En juin 2015, les disques Impulse avaient récidivé avec l’album ‘’Tokyo Adagio’’, un disque en duo avec le pianiste cubain Gonzalo Rubalcaba. Haden avait également collaboré à la publication de l’album.

Même si Charlie Haden n’avait jamais été d’adepte d’une religion en particulier, il s’était toujours intéressé à la spiritualité, car il croyait que comme musicien, c’était sa responsabilité de rendre le monde meilleur.

Un peu comme Archie Shepp, Haden s’était servi de sa musique pour faire progresser les causes qui lui tenaient à coeur, sauf que contrairement à Shepp, Charlie Haden se préoccupait davantage du sort de la planète et de l’humanité en général que de celui des Afro-Américains. c-2023-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l'Imaginaire historique. SOURCES

‘’Charlie Haden.’’ Wikipedia, 2022.

‘’Charlie Haden Biography.’’ Net Industries, 2023.

JARENWATTANANON, Patrick. ‘’Remembering Jazz Legend Charlie Haden, Who Crafted His Voice In Bass.’’ NPR, 11 juillet 2014.

0 notes