#inspired by wuthering heights (1939)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

if he loved you with

all his soul for a lifetime,

he couldn’t love you

as much as i do in a single day.

#inspired by wuthering heights (1939)#arthur being jealous of gwaine is 🤌#gwaine knowing it and being a little shit about is is even more 🤌#merthur#merlin emrys#arthur pendragon#merlin x arthur#arthur x merlin#merthuredit#bbc merthur#merthur is endgame#about merthur#merthur prompt#merthur fanart#merthur kiss#merthur headcanon#merthur fic#merthur incorrect quotes#bbc merlin

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspired by @thatscarletflycatcher's list of actors who have appeared in multiple Jane Austen adaptations, I've made a list of actors who have appeared in two or more adaptations of Brontë novels. I've covered all three of the sisters' books and included radio dramas as well as screen and stage adaptations.

*Timothy Dalton played Heathcliff in the 1970 Wuthering Heights film and Rochester in the 1983 Jane Eyre miniseries.

*Toby Stephens played Gilbert Markham in the 1996 Tenant of Wildfell Hall miniseries and Rochester in the 1983 Jane Eyre miniseries.

*Tara Fitzgerald went from playing Toby Stephens' love interest to playing his love interest's childhood abuser – Helen Graham in the 1996 Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Mrs. Reed in the 2006 Jane Eyre.

*John Duttine holds the distinction of having played both Heathcliff and Hindley Earnshaw in different Wuthering Heights adaptations: Hindley in the 1978 miniseries, Heathcliff in the 1995 radio drama.

*Amanda Root played Catherine Earnshaw in the 1995 Wuthering Heights radio drama and (showing her versatility) Miss Temple in the 1996 Jane Eyre film, as well as narrating the 2004 Naxos audiobook of Jane Eyre.

*Emma Fielding is heard in both the 1995 and 2018 radio dramas of Wuthering Heights: as Catherine Linton in 1995 and as Nelly Dean in 2018. She also narrates the 1996 Naxos audiobook of Jane Eyre.

*Geoffrey Whithead played St. John Rivers in the 1973 Jane Eyre miniseries and Mr. Linton in the 1995 Wuthering Heights radio drama.

*Jean Harvey appeared in both the 1973 and 1983 Jane Eyre miniseries: as Mrs. Reed in 1973 and as Mrs. Fairfax in 1983.

*Judy Cornwell played Nelly Dean in the 1970 Wuthering Heights and Mrs. Reed in the 1983 Jane Eyre.

*David Robb played the Count de Hamal in the 1970 Villette miniseries and Edgar Linton in the 1978 Wuthering Heights miniseries.

*Bryan Marshall played Gilbert Markham in the 1968 Tenant of Wildfell Hall miniseries and Dr. John Graham Bretton in the 1970 Villette miniseries.

*Sarah Smart played Catherine Linton in the 1998 Masterpiece Theatre Wuthering Heights, and Carol Bolton, the female Heathcliff character, in the 2002 TV film Sparkhouse, a modernized, gender-flipped retelling of Wuthering Heights.

*Holliday Grainger played Lisa Bolton, the female Hareton/Linton composite character in Sparkhouse, and Diana Rivers in the 2011 Jane Eyre film.

*Sophie Ward played Isabella Linton in the 1992 Wuthering Heights film and Lady Ingram in the 2011 Jane Eyre.

*Morag Hood played Frances Earnshaw in the 1970 Wuthering Heights and Mary Rivers in the 1983 Jane Eyre.

*Angela Thornton played Isabella Linton in the 1958 TV Wuthering Heights and Blanche Ingram in the 1961 TV Jane Eyre.

*Jean Anderson played Nelly Dean in the 1963 TV version of Wuthering Heights and Mrs. Maxwell in the 1968 Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

*Barbara Keogh played two unpleasant Brontë maidservants: Zillah in the 1978 Wuthering Heights and Miss Abbot in the 1997 TV film of Jane Eyre.

*Norman Rutherford played the lawyer Mr. Green in the 1978 Wuthering Heights and Sir George Lynn in the 1983 Jane Eyre.

*Anna Bentinck narrated the 2015 Dreamscape Media audiobooks of both Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights.

*Janet McTeer played Nelly Dean in the 1992 Wuthering Heights film and reprised the role as co-narrator of the 2006 Naxos audiobook (she reading Nelly's narration, David Timson reading Lockwood's).

*Edward de Souza played Mr. Mason in two different adaptations of Jane Eyre: the 1973 miniseries and the 1996 film.

Adding Brontë family members and friends into the mix:

*Ida Lupino played Isabella Linton in the Lux Radio Theatre's 1939 adaptation of Wuthering Heights based on the 1939 film, and Emily Brontë herself in the 1946 film Devotion.

*Chloe Pirrie played Emily Brontë in the 2016 TV film To Walk Invisible and Catherine Earnshaw in the 2018 Wuthering Heights radio drama.

*Ann Penfold played Polly Home in the 1970 Villette miniseries and Anne Bontë in the 1973 miniseries The Brontës of Haworth.

*Gemma Jones played Mrs. Fairfax in the 1997 Jane Eyre and Elizabeth Branwell in the 2022 film Emily.

*Richard Kay played William Weightman in The Brontës of Haworth and Lockwood in the 1978 Wuthering Heights.

*Megan Parkinson played Catherine Earnshaw in the 2015 Ambassador Theatre stage adaptation of Wuthering Heights and Martha Brown in To Walk Invisible.

*Susan Brodrick played a barmaid in The Brontës of Haworth and Mary Rivers in the 1973 Jane Eyre.

I'm sure there are plenty more, but this list is long enough for now.

#the brontes#the bronte sisters#adaptations#actors#actresses#jane eyre#wuthering heights#the tenant of wildfell hall#villette#charlotte bronte#emily bronte#anne bronte

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's Tito's favourite movie?

If Frankie had a pet, what would it be?

Tito would struggle to pick a favorite movie. The coma made it hard to keep up with cinema, and before that he just never really had the chance. If he liked anything, it would be the old black and white re-runs that would play on TV at night when he was a kid. Maybe that's where his inspiration for the mustache comes from. Can't grow up seeing Gilbert Roland and Clark Gable without wanting to rock the look, too.

If he absolutely had to pick? He'd tell you it's Scarface (1932). He'd be lying. It's Wuthering Heights (1939).

Frankie, however, would not have a pet. Frankie is the pet. Frankie gives Lin a leash and a collar with their name on it and promptly gets thrown out on their ass.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not only has GO S2 gotten me to write more fics, but it's also inspired me to go back to reading my favorite Victorian novels. I was so hooked on them when I was studying literature at university. I need to break out my Austens and Brontes that are still dog-eared and written and highlighted in methinks.

And I recently watched the 1939 adaptation of Wuthering Heights starring Laurence Olivier and that not only spawned a GO fic from me (pre-season 2), but now I wanna re-read that one too.

Not only was the ending of E6 very Mr Darcy, there are hints of Heathcliff as well.

To reiterate, GO S2 is gentle and romantic, and Victorian romances rarely stop at the lovers separating for good (even Heathcliff joined Cathy in the afterlife). Which is prolly why I loved the ending to episode 6 even tho it's heartwrenching! There needs to be a division between the lovers before their climactic embrace at the end.

This was a ramble but God I love the emotions this season has gotten out of me.

#good omens#good omens season 2#good omens season 2 spoilers#fan fiction#Victorian#ineffable husbands

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haha, no you stupid dolt, if you wanna do something that's "all art" and "isn't accurate to life", get your bottom down and write your own work from scratch. We, as readers, viewers, and audiences, have let these a-holes have it too good for too long, smearing their finger paints all over works they have basically found warm and ready, and scribbling all over titles that their authors created to tell specific stories about specific people with, which meant something specifically to them. There is filling in the blanks, there is reading between the lines, there is being inspired, there is being "transformative" and then there's this shit.

If you wanna tell a story the way you 100% want to tell it with no compromise and no parameters you have to work within and respect, then do as every self-respecting creator in history did, and write your own work. And let it be judged by the audience, the market and time, and, if judged positively, perserve and takes its place next to the works it's inspired by. For example, you could write your own story inspired by Wuthering Heights, and then you could write, dress it up and cast it however you'd like. Give it a different name, and go wild.

But you didn't. Because who would care about it if it didn't have "EMILY BRONTE'S WUTHERING HEIGHTS" plastered all over it? How would it make noise? How would your tiny brains (judging from the attitudes you have displayed, which mean to me much more than whether you can tilt a camera or scan through some photos, totally objectively) even begin to compete with the genius that made Emily Bronte's so beloved? Ergo, you know you are insufficient, and you try to leech off from something greater, without having to be challenged at all in actually getting into another era, another mind, and another story, and trying to make it topical or bring out the timeless points of it.

Oh. And "casting" is still a valuable and exacting part of a movie's production. And you can be a good or bad casting director, with successful or unsuccessful stories. So you mean to tell me this lady up there, who cast Edgar and Isabeella Linton, full-blooded siblings in the original novel, of the gentry class of 1780s Yorkshire, is gonna be considered at the same level as those who did the casting for...."The Godfather?" "The Crow?" "Star Wars?" Hell, "Bohemian Rhapsody?"

Hahahaha.

P.S. You wanna see an actually faithful in-spirit adaptation of Wuthering Heights, go watch the 1988 Arashi ga Oka one by Yoshishige Yoshida. Because somehow, you take it, set it in Japan, roll back to the middle ages, insert Shinto folklore and references to the supernatural, and still have it be more faithful to the book's core than 90% of what has been shot in Europe and the US over the previous century - and definitely the 1939 movie, or, I would wager, Emerald Fennell's one. Because see - respect to the point of a work is not just slavish reproduction, in case anyone tries to argue this in favor of this new one.

Also, everything the previous reblog said about Greek mythology.

Emily Brontë didn't write only one book in her life, poured her hardwork under a pen name at first because of the society she lived in, only for Hollywood to come and throw the same excuse of "it's just a book" it's so recycled.

"the greek myths are just stories who cares"

The book is fiction who cares"

"who cares-"

Many do. People that care about the source material. People that enjoy the art and soul one author or a collective ancient civilization created. People WILL care about authenticity and quality but especially when there's obvious respect to the source material.

It's not just fiction because these types of directors use it to make excuses that they'll "fix" them. Why? If you don't care about them to begin with make something of your own.

We are being seen as numbers for cash to an uncaring industry that stopped being creative or original, instead they milk dry every source material to get their money. Don't support this movie at all when the people behind the camera don't care.

#it's the first time I've seen someone so shamelessly and concisely say what exactly is the mindset behind all those adaptations#god i needed to go off like that#wuthering heights#emily bronte#cinema#movies#emerald fennell

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laurence Olivier, the legendary actor and director, left an indelible mark on the world of theater and cinema. He was a master of his craft, a performer who could captivate an audience with a single glance, a gesture, a word. His legacy lives on today, more than three decades after his passing, a testament to the power of his art and his passion.

Born in 1907 in Surrey, England, Olivier was drawn to the stage from an early age. He began performing in local productions as a teenager, and eventually made his way to London, where he studied at the Central School of Speech and Drama. His breakthrough came in 1929, when he was cast as the lead in "Private Lives" at the Garrick Theatre. From that moment on, he was destined for greatness.

Over the next several decades, Olivier would become one of the most celebrated actors of his time. He was a member of the Old Vic Company, where he starred in a series of Shakespearean plays that showcased his talent and versatility. He brought to life iconic characters like Hamlet, Henry V, and Richard III, imbuing each role with a sense of depth and complexity that was unmatched.

Olivier's talents were not limited to the stage, however. He also became a prominent figure in the world of cinema, starring in and directing some of the most memorable films of his era. His performance in "Wuthering Heights" in 1939 was a revelation, earning him his first Academy Award nomination. He followed that up with a series of unforgettable roles in films like "Henry V," "Spartacus," and "Marathon Man," among others.

But it was his work behind the camera that truly set him apart. Olivier was a visionary director, with an eye for detail and a passion for storytelling that shone through in his films. He brought his love of Shakespeare to the screen, directing adaptations of "Hamlet," "Henry V," and "Richard III," among others. His films were marked by their grandeur and their attention to detail, capturing the essence of the plays while also making them accessible to modern audiences.

Olivier's impact on the world of theater and cinema cannot be overstated. He was a pioneer, a trailblazer who paved the way for generations of actors and filmmakers to come. He was a man of great vision and passion, who poured his heart and soul into his work. He was an artist in every sense of the word, and his legacy lives on today in the hearts and minds of those who love the stage and screen.

But perhaps the greatest lesson we can learn from Olivier's life and work is the importance of following our passions. He knew from an early age that he was meant to be an actor, and he pursued that dream with all his heart. He never lost sight of his goal, even in the face of adversity and criticism. He persevered, and his dedication and hard work paid off.

In today's world, where it's easy to get caught up in the daily grind and lose sight of our dreams, Olivier's example is more important than ever. He reminds us that we all have a purpose, a reason for being, and that it's up to us to discover that purpose and pursue it with all our hearts. He shows us that with passion and dedication, anything is possible.

Laurence Olivier was a master of the stage and screen, a true icon of his time. His legacy lives on today, inspiring countless actors and filmmakers around the world. His artistry and his passion will always be remembered, a testament to the power of the human spirit and the beauty of the arts.

#LaurenceOlivier#Shakespeare#theatre#classics#acting#legend#OldHollywood#GoldenAge#BritishCinema#film#stage#art#history#cinema#performingarts#inspiration#talent#icon#drama#biography#culture#entertainment#masterpiece#OscarWinner#Knighted#SirLaurenceOlivier

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello, I adore your blog and art! I was wondering whether you had any recs for things to scratch that wuthering heights itch (for those who devoured WH) — retellings, separate standalone fiction, commentary or academia even?

Hello and thank you! Absolutely. I’ll asterisk my faves. Here’s your one-stop shop for all things Wuthering Heights:

Brontë Books: Literature, Graphic Novels, and Poetry

The Lost Child by Caryl Phillps (2015)

*Glass Town: The Imaginary World of the Brontës by Isabel Greenberg (2020)

The Glass Town Game by Catherynne M. Valente (2017)

*“The Glass Essay” by Anne Carson (1995)

Charlotte Brontë Before Jane Eyre by Glynnis Fawkes (2019)

*The Complete Poetry of Emily Jane Brontë (Columbia, 1995)

Film and TV Adaptations: There’s a lot! Here’s a few.

*Wuthering Heights (2011), dir. Andrea Arnold feat. Kaya Scodelario and James Howard

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1992), dir. Peter Kominsky feat. Juliette Binoche and Ralph Fiennes

Wuthering Heights (1939), dir. William Wyler feat. Merle Oberon and Laurence Olivier

Wuthering Heights (1970), dir. Robert Fuest feat. Anna Calder-Marshall and Timothy Dalton

Wuthering Heights BBC series (2009), dir. Coky Giedroyc feat. Charlotte Riley and Tom Hardy

*Not an adaptation but highly recommended: To Walk Invisible two-part film about the Brontë siblings (2016), dir. Sally Wainwright (director of Gentleman Jack!)

Academia You Can Actually Digest: It Exists!

*The Brontë Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects by Deborah Lutz (2015)

“The real Emily Brontë was red in tooth and claw, forget the on-screen romance” by Hila Shachar (2018)

“Was Emily Brontë’s Heathcliff Black?” by Corinne Fowler (2017)

“The Radical Politics of Wuthering Heights” by yours truly (2020)

There is tons of scholarship on WH from Marxist theory to gender studies to postcolonialism so if you want to dive deeper into a topic let me know and I’ll point you in a good direction!

Illustrations of Wuthering Heights: All-Ladies Edition

Clare Leighton (1898–1989)

Edna Clarke Hall (1879–1979)

Some Other Things: Why Not?

Take some time to peruse the Brontë Society website.

Look into some locations around Haworth: Top Withens (sometimes spelled Withins), Brontë Falls, the Brontë Bridge, Haworth Village, the Parsonage Museum which was their home, etc. It’s cool to see the paths they regularly hiked. Top Withens is said to be an inspiration for the eponymous farmhouse in WH (tho more likely the view than anything).

Some very funny Kate Beaton comics about Wuthering Heights

Ofc, the Kate Bush song but also Noel Fielding dressed like her and dancing to the song

Some photos I took of my hike in Brontë Country

If there’s anything else Wuthering Heights you’re interested in, lmk! :)

#rebecca-dewinters#wuthering heights#emily bronte#lit#answered#i have NO idea how or why that read more got in the question lmao???

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Bamfsteel! Is there any actress/actors you would fancast as members of Blackfyre family? I think young Keri Russell will make a splendid Daena Targaryen, she has heart shaped face and curly blonde hair!

Hi, friendly anon! I’m actually not very good with fancasts because I don’t watch a lot of TV/movies. I mean, I’ve jokingly suggested that Dolph Lundgren should play Daemon Blackfyre, because he’s the only actor I know that is blonde and notoriously shredded. I only know about Keri Russell from her recent Star Wars role, but I agree she would be a better Daena than some other choices, as she could do her physical stunts (Daena was a rider and archer).

However, GRRM actually told his artist Amoka that in drawing some of his characters, to have an actor in a specific role in mind. Considering he was born in the 40s, these movies tend to be “older” even in black and white; some examples include: Ashara Dayne resembles Elizabeth Taylor’s Cleopatra in the 1963 film Cleopatra, Alysanne Targaryen looks like Katharine Hepburn’s Eleanor of Aquitaine from the 1968 film The Lion in Winter, and Brynden Rivers’ high cheekbones, long face, and pale hair are inspired by Max von Sydow’s appearance as Sir Antonius Block from the 1957 film The Seventh Seal. von Sydow would later play the 3-eyed Raven (Brynden as a semi-immortal greenseer) in GOT, which I’m sure GRRM loved.

I’m going to take a leaf out of GRRM’s book and do my best to fancast from some of my favorite old movies:

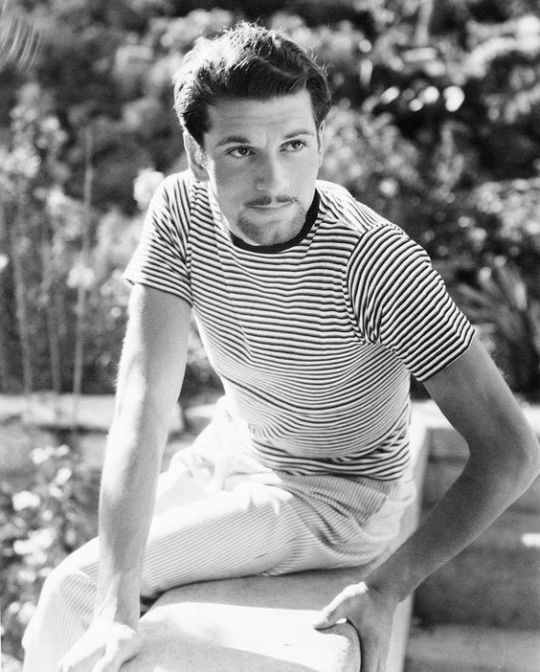

Laurence Olivier from 1939 Wuthering Heights as Aegor Rivers (and not just because Aegor is my most personally relatable character in the era and Sir O is one of my favorite actors). Young!Olivier has Rivers’ black hair and tall lithe figure (as shown when he stands next to Merle Oberon), but more importantly, he’s famous for playing Shakespearean characters and Byronic villains. In the film, his anger as Heathcliff is characterized not by snarling or shouting, but by terrifying, deliberate stillness with moments of violence. At the same time, he can play the part of the man in love (the .gif is him looking at Cathy), and the naive dreamer. So I feel like he’s perfect for portraying those contradictions I see in Aegor.

Britt Ekland from 1973′s The Wicker Man as Shiera Seastar. A notorious sex symbol of her day, Ekland here plays Willow, “the fairest woman on the island” of the pagan Scottish Summerisle. She’s best known for the scene where she dances naked to tempt the chaste hero Sergeant Howie (she has a touch of moral ambiguity here since Howie ‘giving in’ would’ve made him an unfit sacrifice for the cult); the scene is shot in a deliberately ethereal way to imply that she has magical powers. She has a slow smile and mischievous eyes I can imagine on Shiera.

Katharine Hepburn in 1940′s The Philadelphia Story for Daena Targaryen. If according to GRRM older!Hepburn is Alysanne for her wit. elegance, and haunted past, then I feel younger!Hepburn is Daena for her independent spirit, refusal to be tied down, athleticism, and rebelliousness. Despite her sometimes thoughtless and egotistical nature, her character has a strong sense of duty and familial love, and does end up maturing over the course of the plot. (Also, I can imagine Daena in a white nightgown breaking Baelor’s golf clubs in front of him)

It is very important that Rohanne have a Lebanese actress as a fancast, but I couldn’t find a .gif of Majida El Roumi, who is a singer but has acted in a movie (1976 The Prodigal Son Returns). (really I imagine Rohanne as my 2nd grade teacher but that doesn’t really work for faceclaims!) Her family is originally from Tyre, the inspiration for Tyrosh. I feel her round face and motherly, warm eyes are good for showing Rohanne’s softer side. Her black, curly hair was really my only 'must’ for a Rohanne fancast, but I figure Rohanne could have washed out the dye, cut it short and tried to straighten it as an attempt to assimilate into Westerosi culture.

Simonetta Stefanelli in 1972′s The Godfather Part I as young Calla Blackfyre is really the only strong fancast I have for any of the Blackfyre children. I imagine since Rohanne is Fantasy Lebanese and Daemon is Fantasy North Italian, at least some of their children might appear to be a mixture of the two, so here is an Italian actress. I headcanon Calla taking more after her mother in looks (my facial recognition is bad, but she has a similar round face, hair, and smile to Majida?) and having large, intense dark brown eyes that can make her appear sweet and innocent (she gets those dreamy eyes and fuller lips from her father). She’s mostly very serious and is shy with her smiles, but she is intelligent and dislikes when people act like they know better about her future than she does. Despite her character’s tragic status, she’s by no means a fatalist.

These are all of the fancasts I can think of right now without sounding like a complete idiot (my brain is telling me notorious pretty-boy Rudolph Valentino is a Blackfyre but I have no idea who). I’m not convinced it’s possible to fancast Daemon I Blackfyre convincingly (he has to be ‘unearthly beautiful’, shredded, long silvery-haired, have women drawn to him, be an amazing knight/military commander/loving husband, but also clever and manipulative) because his canon portrayals are so contradictory (Sworn Sword versus Twoiaf) it’s difficult to think of an actor who is associated with a role similar to his (...Clark Gable and Mutiny on the Bounty?). I welcome any criticism as, like I said, I don’t have a lot of experience with fancasts or newer films in general.

#ask#asoiaf#fancast#brynden rivers#Aegor Rivers#Daena Targaryen#Rohanne of Tyrosh#calla blackfyre#shiera seastar#Silly Things

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 3 classic literature books <3

thanks for the ask! Good question!

I’ll leave off Shakespeare because obviously those are plays and sonnets, but for the record my top 3 Shakespeare plays are Much Ado about Nothing, Antony and Cleopatra, and The Winter’s Tale. (though I do love others! I can’t pick! Those are the ones I quote the most!) And I think the definition of “classic literature” is actually kind of expanding. However, here’s some “classic lit” I’ve read and really liked:

1. Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser. this book is so interesting, and actually really inspired me for my red dead fic, oddly enough. (It takes place in Chicago around the same time as the game, and as the main female character Charlotte is from Chicago, so I inserted some things from the book in her backstory, like going to the Palmer House, seeing plays at certain theatres, etc. Also talks a lot about the factories and textile mills in Chicago at the time, so I was able to visualize the world she grew up in.) Anyway it’s not about a nun, lol, but a woman named Carrie who ends up as a kept women by a guy named charlie, and eventually a guy named george hurstwood who ruins his life. Also, Carrie ends up as an actress, and an author making a female character an actress was a pretty big deal back then. Also, the history of this books censorship is pretty wild, something I did a project on. A lot of descriptions of Carrie’s corset and “wide forehead” was cut (later restored) because...foreheads are spicy I guess, lol. Also, book doesn’t shame her for having sex, which I think is pretty cool. Books is also a movie with Jennifer Jones and Laurence Olivier, and it’s really good but really obscure. Shame because the acting is well done.

2. Wuthering Heights. So, full transparency....when I was young I saw the movie with Laurence Olivier that was made in 1939 and it made an impression on me. Actually one of my favorite movies. so much so that when I read the book I went easier on it than a lot of my classmates. People hate this book, and I kind of get it, but also how can you not just enjoy the sheer melodrama?

3. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. The book is truly that good. I recommend it, it’s also very accessible.

I did...not expect to pop off on Sister Carrie that much, but I guess I like it more than I remembered, lol.

Sleepover Saturday, send me asks

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merle Oberon: a Life of Passing

Phyllis Chan

In 1978, Merle Oberon was invited to a reception with the Lord Mayor of Hobart, Tasmania, where a theatre had been named in her honour in her hometown. A film star of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Oberon had starred in The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934) and Wuthering Heights (1939), receiving an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for her role in The Dark Angel (1935).

Strangely, after her arrival, she denied she had been born there, excused herself, and declined questions about the truth of her background. For the rest of her stay in Hobart she remained ensconced in her hotel and never visited the theatre named after her. She died the following year in Malibu at the age of sixty-eight.

Oberon had claimed throughout her career that she had been born and raised in Tasmania, and that records of her birth had been destroyed in a fire. After her death, however, the truth began to emerge, especially after her nephew Michael Korda, editor-in-chief at the American publishers Simon & Schuster, wrote a novel based on his aunt’s story, called Queenie in reference to her childhood nickname. He asserted to the Los Angeles Times that Oberon had been an Anglo-Indian, i.e. of mixed parentage, born in Bombay (Mumbai).

Over the decades, rumours spiraled as various biographers attempted to find out the truth of Oberon’s parentage, or, to put it more bluntly, her race. Throughout her career her beauty had been described as ‘exotic’, a term that was used similarly for actresses of colour, such as Puerto Rican Rita Moreno. Due to US law at the time Oberon was being cast in leading romantic roles, it was illegal for interracial kisses to be depicted onscreen (alongside widespread laws against interracial marriage until 1967). It would have been impossible had the truth been known for Oberon to have starred alongside Leslie Howard or Laurence Olivier in her most famous films.

Biographer Charles Higham in the 1980s noted of how difficult it was for him to gain any information on Oberon’s early life before her arrival in England, aged seventeen. He went as far as requesting birth records from the Tasmanian government before receiving a letter from a Mrs Frieda Syer in India, who claimed she had known her and her half-sister Constance.

Some continued to believe she was Tasmanian. As late as 2008 a publisher and art dealer in Hobart, Nevin Hurst, offered a reward of $10,000 Australian dollars for ‘convincing proof’ she was indeed born there. Others insisted she was Tasmanian-Chinese. Shortly after, another biography, this one called Merle Oberon: Face of Mystery, was released, penned by Bob Casey. The story of Merle Oberon had become a Hollywood enthusiast’s puzzle, made all the more mysterious and alluring due to her renowned beauty and glamour, with that acceptable tinge of the ‘exotic’.

In 2014, the British Library collaborated with the genealogy website findmypast.co.uk to publish over 2.4 million records from the India Office Collection online. Amongst these was Oberon’s birth certificate, which confirmed a tragic, lurid story seized immediately upon by the Daily Mail.

According to the certificate, Estelle Merle O’Brien Thompson was born in Bombay on the 19th of February, 1911 to Constance Selby and Arthur Thompson, a British railway engineer. Selby was only twelve years old at the time of Oberon’s birth. After Thompson died after enlisting in the First World War, Oberon was brought up by her grandmother Charlotte, herself a Ceylonese Burgher of mixed descent, including partial Maori ancestry. She had given birth to Constance herself at the age of fourteen after a ‘relationship’ with an Anglo-Irish foreman on a tea plantation.

It is clear that Oberon knew the social stigma of her unconventional birth as well as her race. While Anglo-Indian relationships had been commonplace in the early part of the nineteenth century, ideas of racial ‘purity’ and the protection of ‘whiteness’ soon permeated the colonial world. Oberon’s mother and grandmother are described in various articles as being in relationships with older white men at highly precocious ages. While we have to be cautious about anachronism, it is easy to fill in the blanks here as to the trauma Oberon and her family suffered.

Various details about Oberon’s attitude towards her identity reveal the painful reasons she hid the truth for so long; her embarrassment at her ‘mother’ picking her up from school, so much ‘darker’ than she; a relationship that ended after the man in question saw her mother’s skin tone. While Oberon’s rags-to-riches story has doubtless inspired many of mixed-race and Indian descent, it clearly pained her that so many attempted to peel back her façade to the end of her life, all for a salacious story. Perhaps rather than searching for painful stories asserting tropes of mixed-race ‘exoticism’, we should be focusing on deconstructing them and respecting the individuals behind them.

Below: a headline pulled from the top ten results for ‘Merle Oberon’ on Google.

#indianhistory#hollywood#goldenage#merle oberon#classichollywood#eurasian#woc#mixed#americanhistory#colonial history#imperial history#decolonize#white passing

1 note

·

View note

Text

I just reread Wuthering Heights for the first time since high school. Thanks to @theheightsthatwuthered, @wuthering-valleys, @astrangechoiceoffavourites and others for inspiring me to do it!

Here are some of the things that stood out the most for me.

1. I can’t believe how ambiguous all the characters are! “Morally gray” doesn’t begin to describe it. Even the most sympathetic characters are deeply, deeply flawed, yet just when a character seems unredeemable, they’ll show their capacity for love and altruism. It’s hard to say how Brontë meant us to feel about any of them. I won’t even touch on Heathcliff or the other leads: the example I’ll use is the short-lived yet important figure of Mr. Earnshaw. On the one hand, he’s framed both by Nelly Dean’s narration and by Cathy I’s diary as a kind, benevolent man. He takes in the homeless, orphaned young Heathcliff, raises and loves him as his own, treats his servants almost like family, is reasonably warm and indulgent to his children before his illness worsens his temper, and is very much loved by little Cathy in particular. After he dies and Hindley becomes the tyrannical new master, Cathy and Nelly remember his lifetime as a paradise lost. But he blatantly favors Heathcliff over his own children, sewing the seeds for Hindley’s abuse and degradation of Heathcliff, and during his illness, the disparaging way he talks to and about Hindley and Cathy definitely feels like emotional abuse, at least by modern standards. His harsh words to Cathy are especially heartbreaking given how clearly she worships him and it makes you wonder if her future arrogance is really a cover for self-doubt. But since Nelly depicts Hindley and Cathy as difficult and bratty from childhood, and both become truly toxic adults, maybe their father’s harshness is meant to be justified or at least understandable, and since Heathcliff was a poor orphan who faced who-knows-what horrors in his first seven years, we might argue that he needed more care and affection. But Heathcliff also becomes a toxic adult and Nelly implies that being the favored child made him spoiled and arrogant. And none of the above even touches on the theory that Heathcliff might be Mr. Earnshaw’s illegitimate son, which would definitely cast the latter in a less favorable light. Any claim of “This is how we’re supposed to feel about this character” can only fall flat, because there’s so much ambiguity.

2. The recent reviews by @astrangechoiceoffavourites of the 1939 and 1970 film versions point out something interesting: that in both of those versions, which only adapt only the first half of the book, Cathy (I) is more of the protagonist than Heathcliff. This insight raises a good question: who really is the protagonist of the book? Of course the traditional answer is Heathcliff. He’s the character we follow from beginning to end, whose actions drive the entire plot. But he’s not the viewpoint character; we mostly see him from Nelly Dean’s perspective, and Heathcliff sometimes disappears for months or years at a time from her narrative. Yet Nelly can’t be called the protagonist because she’s more of an observer than an active participant. I think we can argue that, at least in terms of plot structure, the two Cathys are the book’s real protagonists: Cathy I leads the first half, with Heathcliff as the deuteragonist/love interest, while Cathy II leads the second half, with Heathcliff as the villain. Of course this is debatable, but so is nearly everything else about this book.

3. I never realized until now what a perfect inversion Cathy II’s character arc is of her mother’s arc. There are so many parallels, but they happen in the opposite order. Just look:

** Cathy I is born and raised at Wuthering Heights, but as a young girl she ventures to Thrushcross Grange, meets her future husband and ultimately lives there./Cathy II is born and raised at Thrushcross Grange, but as a young girl she ventures to Wuthering Heights, meets her future husband and ultimately lives there.

** Both are raised by widowed fathers whom they adore, although Mr. Earnshaw is stern and critical to Cathy I while Edgar dotes on Cathy II; eventually both fathers die prematurely, leaving their daughters in a tyrannical new patriarch’s hands (Hindley/Heathcliff).

** Cathy I initially loves the rugged, dark haired Heathcliff, who lives as a servant at Wuthering Heights; she helps to educate him and they wander the moors together. But as she spends more time at Thrushcross Grange, she absorbs its snobbery, treats him with increasing disdain (though she really does still love him), and favors the refined, prissy, blond haired Edgar, whom she eventually marries./Cathy II initially loves (or at least cares for) the refined, prissy, blond haired Linton, whom she eventually marries. Having been raised with Thrushcross Grange’s snobbery, she initially disdains the rugged, dark haired Hareton, who lives as a servant at Wuthering Heights. But as she lives at the Heights after Linton dies, she looses her snobbery and becomes increasingly drawn to Hareton; ultimately they fall in love, she helps to educate him and they wander the moors together.

** Because of the above, Cathy I’s story ends tragically, while Cathy II’s story ends happily.

It really is too bad that most screen and stage adaptations only adapt the first half and leave out Cathy II, because it seems to me that Cathy I’s story was always meant to be juxtaposed with her daughter’s mirror-image arc.

4. If I was ever half-tempted to believe the theory that Branwell Brontë was the book’s real author, I don’t believe it anymore. There’s no way a 19th century man, especially one who was allegedly a bit of a womanizer, could have written such nuanced, realistic, non-objectified female characters. Even male authors whose characterizations of women I respect, both of the past and of today, tend to have problems with sexualization, madonna-whore stereotyping, etc. But the women in Wuthering Heights are thoroughly non-sexualized three-dimensional characters: all of them flawed yet (arguably) all sympathetic, no better yet no worse than the men around them, all fully human.

5. The circumstances of Cathy I’s mental and physical breakdown are different than I remembered from high school. I was under the impression that Heathcliff married Isabella to hurt Cathy the way she had hurt him and that Cathy’s brain fever was caused by jealousy and heartbreak at being “rejected” for another woman. I think the screen adaptations tend to frame it more that way. But really, Heathcliff marries Isabella less to hurt Cathy emotionally than to gain power over her husband by gaining a claim to inherit his property and fortune. Nor is Cathy’s breakdown caused by jealousy (she knows Heathcliff doesn’t really love Isabella, after all), but by the conflict between Heathcliff and Edgar that the Isabella scandal triggers, which culminates in Edgar punching Heathcliff, making him flee for his life, and demanding that Cathy choose between them. It’s the crumbling of Cathy’s attempted double life with both men that breaks her, not rivalry with Isabella.

6. When I first started the reread, my dad suggested that I try to see if I could find more sexual tension between Heathcliff and Cathy I than I did in high school. But I didn’t. Their love is just as strangely, fascinatingly sexless as I thought it was. I suppose the question remains: did Brontë purposefully write it as sexless, or does it just reflect her own lack of sexual experience?

7. If I were to write the screenplay for a new film version of Wuthering Heights, I think I’d present it in anachronic order, similar to Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. Scenes from the first half would alternate with scenes from the second half. This way the second half would really be given its due, the mirror-imagery between Cathy I and Cathy II’s character arcs would be especially apparent, and the Hareton/Cathy II romance could be highlighted as a healthy alternative to Heathcliff/Cathy I. I would also make a definite point to de-romanticize Heathcliff, not only by portraying him as a tragic man-turned-monster and not downplaying his cruelty, but by leaving it ambiguous, as I think it is in the book, whether the love he shares with Cathy I really is romantic love or a strangely intense, codependent brother/sister bond. I definitely wouldn’t age them into young adult lovers on the moors the way most screen versions do; I’d portray them at their correct ages, just 12/13 when they roam the moors together and still just 15/16 when Cathy accepts Edgar’s proposal, and highlight that they were only truly happy together as children. That in some ways their love is always the love of two children, both in its selfishness and in its purity. Cathy’s ghost at the window would be portrayed as a child, as in the book, and if I were to show Heathcliff’s ghost joining her in the end, I just might have them both transform back into their 12/13-year-old selves. That could make for an interesting contrast with Hareton and Cathy II in the end: Heathcliff and Cathy I reunited as free, half-savage children, while their foster-son and daughter appear as a mature romantic couple embracing civilization and adulthood.

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the biggest movie stars of the 1930s, India-born Merle Oberon, was Hollywood's first #Indian actress. She is famous for her role as Cathy in the movie Wuthering Heights (1939). She was born in Bombay, British India in 1911 to a 12-year-old mother who was #Eurasian, her father was #British. For most of her life she protected herself by concealing the truth about her parentage, claiming that she had been born in Australia, & that her birth records had been destroyed. Her birth certificate listed her maternal grandmother as her mother. To avoid scandal she raised her 12 year old daughter & Merle as sisters instead. The identity of her father is unknown. Before starting her career as an actress, she used to perform with the Calcutta Amateur Dramatic Society. She arrived in England in 1928, at 17. In 1929, Merle dated an actor, Colonel Ben Finney; however, when he saw her dark-skinned mother one night at her flat, he realised she was of #mixedancestry & ended the relationship. He had already helped her network by this time though & she soon started to land roles. It was her “exotic appearance” that got her a role in the film The Three Passions. She went on to play Ann Boleyn in the Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). She moved to Hollywood after her stellar performance in The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934). She was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actress in The Dark Angel (1935). She was in a car accident in 1937 and it almost ended her career due to her face being injured. She suffered even further damage to her complexion in 1940 from a combination of cosmetic poisoning & an allergic reaction. She didn’t let these incidents stop her & worked for another 30 years. She died in 1979 at age 68. She hid her Indian heritage until a year before her death. She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Margo Taft, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon was based on her. Her hidden heritage inspired a 2002 documentary, The Trouble With Merle & the novel White Lies which became a film in 2013. 🎭🎬 🇮🇳🇬🇧 #womenshistorymonth #mixedgirl https://www.instagram.com/p/B9iUuuMlJUv/?igshid=uj7qc8hmvr1d

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noirvember the 4th: The Lodger (1944)

The Lodger (1944)

19 January 1944 | 84 min. | B&W

Director: John Brahm

Writer: Barre Lyndon (screenplay) and Marie Belloc Lowndes (novel)

Cinematography: Lucien Ballard

A Jack the Ripper Tale, The Lodger takes place in London, Whitechapel to be specific, around the 1880s. A man called Slade (Laird Cregar) takes a room with a well-to-do, but currently hard-up older couple. Slade exhibits some strange behaviors and fixations but the family is understanding and chalks it up to idiosyncrasy. The couple’s niece, Kitty Langley (Merle Oberon), is newly returned from Paris bringing her successful song-and-dance act to the London stage. As the hints that Slade might actually be the Ripper start piling up, the family gets more and more suspicious that their lodger might not be a garden-variety weirdo.

This post is a bit longer than the others so READ ON BELOW THE JUMP!

When I saw The Lodger in the Film Noir section at Movie Madness, I thought I’d give it a go! As with The Red House (1947), this was an intriguing movie I missed on television a while back. Honestly, after seeing The Lodger, it’s categorization as noir is a little shaky. It has a few hallmarks–mostly the creative, chiaroscuro-inspired lighting and some expressionistic shots and camera angles. All in all, this feels more like a horror-thriller to me. That is in no way a knock on the film btw–I loved it! The Lodger probably most reminded me of Peeping Tom (1960).

Every shot in The Lodger is perfectly constructed for the emotion of its scene. The filmmakers create humour, tension, or convey practical information as needed via the combination of the way people are packed into each shot, how that shot is lit, and camera movement. The Lodger puts on display a huge amount of technical skill in visual storytelling.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised as a huge Twilight Zone fan. I was cool to finally see a John Brahm feature film. Brahm directed one of The Twilight Zone’s most famous episodes, “Time Enough at Last,” and also two of my personal favorites “Mirror Image” and “Shadow Play.” Looking through his filmography, I think I’ll check out The Locket (1946) next, which appears to be a more traditional noir.

The cinematographer, Lucien Ballard, makes every shot of Merle Oberon exquisite. You may well come away from this film thinking she’s the most beautiful woman who has ever lived. Apparently Ballard did as they married after not long after making The Lodger. There was a practical reason as well for Oberon’s shots looking so ethereal: Oberon was dealing with facial scarring at the time of filming and Ballard himself devised a method of photographing her to camouflage it.

Continuing on Oberon, she is fantastic in this movie. It might be one of my favorite performances of hers–up there with Kathy in Wuthering Heights (1939). Her character is quite unique–she’s filled with no end of kindness and patience even after she begins suspecting Slade is The Ripper. In one scene, in a single shot, Oberon registers pleasantness in light conversation to apprehension to poorly concealed panic gradually and naturally. It’s stunning. Side note: it’s also pretty endearing that Oberon is only okay at dancing.

The Lodger took me a bit off guard by following a monster-movie plot. However, where the women in peril is often one-note in many earlier monster films, it’s Oberon who is charismatic and interesting. The male “savior” character gets little attention here (which is fine because he’s George Sanders and you could give him nothing and he’d make it memorable).

That leaves the monster: Laird Cregar’s Slade. Cregar puts in a great performance here. His delivery and posture make him pathetic and intimidating in turn. I genuinely thought throughout the film that he could very well be an awkward person afraid of being implicated–as a weird loner would be in this situation. It’s so tragic that the future was so bright for Cregar following the success of this film, but that he would die not long after The Lodger’s completion.

I don’t know that I’d recommend The Lodger specifically for Noirvember, but I do think it’s necessary viewing for my fellow horror enthusiasts. The Lodger is one of the more significant films I’ve seen bridging the gap between the Universal-style horror that set the trend from the pre-code era into the 1940s and the next big stylistic wave that followed Peeping Tom and Psycho (1960). Check this one out!

Previous Noirvember 2018 Posts:

The Red House (1947) | Fury (1936) | Out of the Past (1947)

#noirvember#film noir#noir#1940s#The Lodger#john brahm#laird cregar#merle oberon#george sanders#classic film#classic movies#horror#horror film#Horror Movies#jack the ripper#Film Review#film recs#movie recommendations#movie review#movies#film#film blog#film blogger

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#153: Wuthering Heights (1939) with Kristen Lopez

https://www.podbean.com/media/share/pb-6x4y6-1397abe That’s right, our host Kristen Lopez is the guest as we celebrate the upcoming release of her first book, But Have You Read the Book: 52 Literary Gems That Inspired Our Favorite Films. We’re talking about 1939’s adaptation of Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Along for the ride is Patron Jacob Haller, helping Samantha and Kristen deconstruct…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

HELLO!!! - SRS

Hope your day is going awesome! Hope you’re enjoying the weather, wherever you may be! For me, it’s rainy and cold 🌧 but that’s some of my favorite weather!!

To answer your questions from yesterday, my favorite Simon and Garfunkel song is probably The Boxer, my fav Lana song is National Anthem, and my fav Beatles song is BLUE JAY WAY!!

I got into most of my favorite bands from my dad or from my friends!! Woohoo!!!

DO U HAVE A FAV FACT ABOUT KATE BUSH! she is AMAZING and Id love to know what you know!! 🥰🥰🥰🥰🥰

Hope your day is going well too ❤❤❤ I love cold weather too, and here it is finally getting cold enough that one needs to wear gloves. Where do you live btw, if you're OK with sharing.

The Boxer is great and always makes me feel a bit emotional too. I'm glad we both love the psychedelic Beatles songs. My dad also got me a bit in classic rock but a lot of it was me finding music by myself through music channels on TV and the Internet 😌 I haven't listened to the radio since 2013, I imagine there is good stuff but I'm simply to used to not care lol. What about you, do you keep up with modern music? 🤔

I haven't read up on Kate much recently but as a teen I was obsessed with the fact that Prince said that she is one of his favourite women. He has backing vocals in her song "Why should I love you" which is such a melodious song. I was also obsessed with how young she wrote Wuthering Heights and started her career. Because of her I became obsessed with the book and films versions. Especially the 1939 version which I think inspired her plus is amongst one of my favourite films ever ❤❤❤ What songs of hers do you like? 😊

0 notes

Text

Gothic Film in the ‘40s: Doomed Romance and Murderous Melodrama

Posted by: Samm Deighan for Diabolique Magazine

Secret Beyond the Door (1947)

In many respects, the ‘40s were a strange time for horror films. With a few notable exceptions, like Le main du diable (1943) or Dead of Night (1945), the British and European nations avoided the genre thanks to the preoccupation of war. But that wasn’t the case with American cinema, which continued to churn out cheap, escapist fare in droves, ranging from comedies and musicals to horror films. In general though, genre efforts were comic or overtly campy; Universal, the country’s biggest producer of horror films, resorted primarily to sequels, remakes, and monster mash ups during the decade, or ludicrous low budget films centered on half-cocked mad scientists (roles often hoisted on a fading Bela Lugosi).

There are some exceptions: the emergence of grim-toned serial killer thrillers helmed by European emigres like Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Ulmer’s Bluebeard(1944), Siodmak’s The Spiral Staircase (1945), or John Brahm’s Hangover Square(1945); the series of expressionistic moody horror film produced by auteur Val Lewton, such as Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943); and a handful of strange outliers like the eerie She-Wolf of London (1946) or the totally off-the-rails Peter Lorre vehicle, The Beast with Five Fingers (1946).

Thanks to the emergence of film noir and a new emphasis on psychological themes within suspense films, horror’s sibling — arguably even its precursor — the Gothic, was also a prominent cinematic force during the decade. One of the biggest producers of Gothic cinema came from the literary genre’s parent country, England. Initially this was a way to present some horror tropes and darker subject matter at a time when genre films were embargoed by a country at war, but Hollywood was undoubtedly attempting to compete with Britain’s strong trend of Gothic cinema: classic films like Thorold Dickinson’s original Gaslight (1940); a series of brooding Gothic romances starring a homicidal-looking James Mason, like The Night Has Eyes (1942), The Man in Grey(1943), The Seventh Veil (1945), and Fanny by Gaslight (1944); David Lean’s two best films and possibly the greatest Dickens adaptations ever made, Great Expectations(1946) and Oliver Twist (1948); and other excellent, yet forgotten literary adaptations like Uncle Silas (1947) and Queen of Spades (1949).

The American films, which not only responded to their British counterparts but helped shape the Gothic genre in their own right, tended towards three themes in particular (often combining them): doomed romance, dark family inheritances often connected to greed and madness, and the supernatural melodrama. Certainly, these film borrowed horror tropes, like the fear of the dark, nightmares, haunted houses, thick cobwebs, and fog-drenched cemeteries. The home was often set as the central location, a site of both domesticity and terror — speaking to the genre’s overall themes of social order, repressed sexuality, and death — and this location was of course of equal importance to horror films and the “woman’s film” of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Like the latter, these Gothic films often featured female protagonists and plots that revolved around a troubled romantic relationship or domestic turmoil.

Wuthering Heights (1939)

Two of the earliest examples, and certainly two films that kicked off the wave of Gothic romance films in America, are also two of the genre’s most enduring classics: William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights (1939) and Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940). Based on Emily Brontë’s novel of the same name (one of my favorites), Wyler and celebrated screenwriter Ben Hecht (with script input from director and writer John Huston) transformed Wuthering Heights from a tale of multigenerational doom and bitterness set on the unforgiving moors into a more streamlined romantic tragedy about the love affair between Cathy (Merle Oberon) and Heathcliffe (Laurence Olivier) that completely removes the conclusion that focuses on their children. In the film, the couple are effectively separated by social constraints, poverty, a harsh upbringing, and the fact that Cathy is forced to choose between her wild, adopted brother Heathcliffe and her debonair neighbor, Edgar Linton (David Niven).

Wuthering Heights is actually less Gothic than the films it inspired, primarily because of the fact that Hollywood neutered many of Brontë’s themes. In The History of British Literature on Film, 1895-2015, Greg Semenza and Bob Hasenfratz wrote, “Hecht and Wyler together manage to transfer the narrative from its original literary genre (Gothic romance) and embed it in a film genre (the Hollywood romance, which would evolve into the so-called ‘women’s films’ of the 1940s)… [To accomplish this,] Hecht and Wyler needed to remove or tone down elements of the macabre, the novel’s suggestions of necrophilia in chapter 29, and its portrayal of Heathcliffe as a kind of Miltonic Satan” (185).

This results in sort of watered down versions of Cathy — who is selfish and cruel as a general rule in the novel — and, in particular, Heathcliffe, whose brutish behavior includes physical violence, spousal abuse, and a drawn out, well-plotted revenge that becomes his sole reason for living. It is thus in a somewhat different — and arguably both more terrifying and more romantic — context that the novel’s Heathcliffe declares to a dying Cathy, “Catherine Earnshaw, may you not rest as long as I am living. You said I killed you–haunt me then. The murdered do haunt their murderers. I believe–I know that ghosts have wandered the earth. Be with me always–take any form–drive me mad. Only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you! Oh, God! It is unutterable! I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!” (145).

Despite Hollywood’s intervention, the novel’s Gothic flavor was not scrubbed entirely and Wuthering Heights still includes themes of ghosts, haunting, and just the faintest touch of damnation, though it ends with a spectral reunion for Cathy and Heathcliffe, whose spirits set off together across the snow-covered moors. These elements of a studio meddling with a film’s source novel, doomed romance, and supernatural tones also appeared in the following year’s Rebecca, possibly the single most influential Gothic film from the period. This was actually Hitchcock’s first film on American shores after his emigration due to WWII, and his first major battle with a producer in the form of David O. Selznick.

Rebecca (1940)

Based on Daphne du Maurier’s novel of the same name, Rebecca marks the return of Laurence Olivier as brooding romantic hero Maxim de Winter, the love interest of an innocent young woman (Joan Fontaine) traveling through Europe as a paid companion. She and de Winter meet, fall in love, and are quickly married, though things take a dark turn when they move to his ancestral home in England, Manderlay, which is everywhere marked with the overwhelming presence of his former wife, Rebecca. The hostile housekeeper (Judith Anderson) is still obviously obsessed with her former mistress, Maxim begins to act strangely and has a few violent outbursts, and the new Mrs. de Winter begins to suspect that Rebecca’s death was the result of a homicidal act…

The wanton or mad wife was a feature not only of Rebecca, but of earlier Gothic fiction from Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre to “The Yellow Wallpaper.” In the same way that Cathy of Wuthering Heights is an example of the feminine resistance to a claustrophobic social structure, Rebecca is a similar figure, made monstrous by her refusal to conform. The dark secret that Maxim’s new wife learns is that Rebecca was privately promiscuous, agreeing only to appear to be the perfect wife in public after de Winter already married her. She pretends she is pregnant with another man’s child and tries to goad her husband into murdering her, seemingly out of sheer spite, but it is revealed that she was dying of cancer.

A surprisingly faithful adaptation of the novel, Rebecca presents the titular character’s death as a suicide, rather than a murder, thanks to the Production Code’s insistence that murderers had to be punished, contrary to the film’s apparent happy ending, and restricted the (now somewhat obvious) housekeeper’s lesbian infatuation for Rebecca. Despite these restrictions, Hitchcock managed to introduce some of the bold, controversial themes that would carry him through films like Marnie (1964). For Criterion, Robin Wood wrote, “it is in Rebecca that his unifying theme receives its first definitive statement: the masculinist drive to dominate, control, and (if necessary) punish women; the corresponding dread of powerful women, and especially of women who assert their sexual freedom, for what, above all, the male (in his position of dominant vulnerability, or vulnerable dominance) cannot tolerate is the sense that another male might be “better” than he was. Rebecca is killed because she defies the patriarchal order, the prohibition of infidelity.”

Wood also got to the crux of many of these early Gothic films (and the Romantic/romantic novels that inspired them) when he wrote, “The antagonism toward Maxim we feel today (in the aftermath of the Women’s Movement) is due at least in part to the casting of Olivier; without that antagonism something of the film’s continuing force and fascination would be weakened.” Heathcliffe and de Winter are similarly contradictory figures: romantic, but also repulsive, objects of love and fear in equal measures, they mirror the character type popularized in England by a young, brooding James Mason — an antagonistic, almost villainous (and sometimes actually so) male romantic lead — that would appear in a number of other titles throughout the decade.

Rebecca (1940)

In “‘At Last I Can Tell It to Someone!’: Feminine Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s” for Cinema Journal, Diane Waldman wrote, “The plots of films like Rebecca, Suspicion, Gaslight, and their lesser-known counterparts like Undercurrent and Sleep My Love fall under the rubric of the Gothic designation: a young inexperienced woman meets a handsome older man to whom she is alternately attracted and repelled. After a whirlwind courtship (72 hours in Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door, two weeks is more typical), she marries him. After returning to the ancestral mansion of one of the pair, the heroine experiences a series of bizarre and uncanny incidents, open to ambiguous interpretation, revolving around the question of whether or not the Gothic male really loves her. She begins to suspect that he may be a murderer” (29-30).

As Waldman suggests, there are many films from the decade that fit into this type: notable examples include Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941), where Joan Fontaine again stars as an innocent, wealthy young woman who marries an unscrupulous gambler (Cary Grant) who may be trying to kill her for her fortune; Robert Stevenson’s Jane Eyre (1943) yet again starred Fontaine as the innocent titular governess, who falls in love with her gloomy, yet charismatic employer, Mr. Rochester (Orson Welles); George Cukor’s remake of Gaslight (1944) starred Ingrid Bergman as a young singer driven slowly insane by her seemingly charming husband (Charles Boyer), who is only out to conceal a past crime; and so on.

Another interesting, somewhat unusual interpretations of this subgenre is Experiment Perilous (1944), helmed by a director also responsible for key film noir and horror titles such as Out of the Past, Cat People, and Curse of the Demon: Jacques Tourneur. Based on a novel by Margaret Carpenter and set in turn of the century New York, Experiment Perilous is a cross between Gothic melodrama and film noir and expands upon the loose plot of Gaslight, where a controlling husband (here played by Paul Lukas) is trying to drive his younger wife (the gorgeous Hedy Lamarr) insane. The film bucks the Gothic tradition of the ‘40s in the sense that the wife, Allida, is not the protagonist, but rather it is a psychiatrist, Dr. Bailey (George Brent). He encounters the couple because he befriended the husband’s sister (Olive Blakeney) on a train and when she passes away, he goes to pay his respects. While there, he he falls in love with Allida and refuses to believe her husband’s assertions that she is insane and must be kept prisoner in their home.

In some ways evocative of Hitchcock (a fateful train ride, a psychiatrist who falls in love with a patient and refuses to believe he or she is insane), Experiment Perilous is a neglected, curious film, and it’s interesting to imagine what it would have been if Cary Grant starred, as intended. It does mimic the elements of female paranoia found in films like Rebecca and Gaslight, in the sense that Allida believes she has a mysterious admirer and, as with the later Secret Beyond the Door, she’s tormented by the presence of a disturbed child; though Lamarr never plays to the level of hysteria usually found in this type of role and her performance is both understated and underrated.

Experiment Perilous (1944)

Tourneur was an expert at playing with moral ambiguities, a quality certainly expressed in Experiment Perilous, and the decision to follow the psychiatrist, rather than the wife, makes this a compelling mystery. Like Laura, The Woman in the Window, Vertigo, and other films, the mesmerizing portrait of a beautiful woman is responsible for the protagonist becoming morally compromised, and for most of the running time it’s not quite clear if Bailey is acting from a rational, medical premise, or a wholly irrational one motivated by sexual desire. Rife with strange diary entries, disturbing letters, stories of madness, death, and psychological decay, and a torrid family history are at the heart of the delightfully titled Experiment Perilous. Like many films in the genre, it concludes with a spectacular sequence where the house itself is in a state of chaos, the most striking symbol of which is a series of exploding fish tanks.

But arguably the most Gothic of all these films — and certainly my favorite — is Fritz Lang’s The Secret Beyond the Door (1947). On an adventure in Mexico, Celia (Joan Bennett), a young heiress, meets Mark Lamphere (Michael Redgrave), a dashing architect. They have a whirlwind romance before marrying, but on their honeymoon, Mark is frustrated by Celia’s locked bedroom door and takes off in the middle of the night, allegedly for business. Things worsen when they move to his mansion in New England, where she is horrified to learn that she is his second wife, his first died mysteriously, and he has a very strange family, including an odd secretary who covers her face with a scarf after it was disfigured in a fire; he also has serious financial problems. During a welcoming party, Mark shows their friends his hobby, personally designed rooms in the house that mimic the settings of famous murders. Repulsed, Celia also learns that there is one locked room that Mark keeps secret. As his behavior becomes increasingly cold and disturbed she comes to fear that he killed the first Mrs. Lamphere and is planning to kill her, too.

A blend of “Bluebeard,” Rebecca, and Jane Eyre, Secret Beyond the Door is quite an odd film. Though it relies on some frustrating Freudian plot devices and has a number of script issues, there is something truly magical and eerie about it and it deserves as far more elevated reputation. Though this falls in with the “woman’s films” popular at the time, Bennett’s Celia is far removed from the sort of innocent, earnest, and vulnerable characters played by Fontaine. Lang, and his one-time protege, screenwriter Silvia Richards, acknowledge that she has flaws of her own, as well as the strength, perseverance, and sheer sexual desire to pursue Mark, despite his potential psychosis.

This was Joan Bennett’s fourth film with Fritz Lang – after titles like Man Hunt (1941), The Woman in the Window (1944), and Scarlet Street (1945) — and it was to be her last with the director. While her earlier characters were prostitutes, gold diggers, or arch-manipulators, Celia is more complex; she is essentially a spoiled heiress and socialite bored with her life of pleasure and looking to settle down, but used to getting her own way and not conforming to the needs of any particular man. (Gloria Grahame would go on to play slightly similar characters for Lang in films like The Big Heat and Human Desire.) In one of Celia’s introductory scenes, she’s witness to a deadly knife fight in a Mexican market. Instead of running in terror, she is clearly invigorated, if not openly aroused by the scene, despite the fact that a stray knife lands mere inches from her.

Secret Beyond the Door (1947)

Like some of Lang’s other films with Bennett, much of this film is spent in or near beds and the bedroom. The hidden bedroom also provides a rich symbolic subtext, one tied in to Mark’s murder-themed rooms, the titular secret room (where his first wife died), and the burning of the house at the film’s conclusion. Due to the involvement of the Production Code, sex is only implied, but modern audiences may miss this. It is at least relatively clear that Mark and Celia’s powerful attraction is a blend of sex and violence, affection and neurosis. As with Rebecca and Jane Eyre, it is implied that the fire — the act of burning down the house and the memory of the former love (or in Jane Eyre’scase, the actual woman) — has cleansing properties that restore Mark to sanity. It is revealed that though he did not commit an actual murder, the guilt of his first wife’s death, brought on by a broken heart, has driven him to madness and obsession.

This really is a marvelous film, thanks Lang’s return to German expressionism blended with Gothic literary themes. There is some absolutely lovely cinematography from Stanley Cortez that prefigured his similar work on Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter. In particular, a woodland set – where Celia runs when she thinks Mark is going to murder her – is breathtaking, eerie, and nightmarish, and puts a marked emphasis on the fairy-tale influence. But the house is where the film really shines with lighting sources often reduced to candlelight, reflections in ornate mirrors, or the beam of a single flashlight. The camera absolutely worships Bennett, who is framed by long, dark hallways, foreboding corridors, and that staple of film noir, the winding staircase.

3 notes

·

View notes