#i want to go volunteer with afghan refugees

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Most self improvement things are things you can do. All are really bc if it's something you are, you can't change it. There are some things about yourself you can't change, things written in your DNA. But everyone can perform kind actions.

kindness is a discipline, not a trait

#i dont want to change#i want to do more better things#theres a difference#i want to be true to myself#or i get stressed#and i know im lying which i hate#need to find what works for me#being nice to ppl in daily life#giving things#its totally doable#i cant do it all day...#other things i can do#jobs#problem is idk how much i can really do#if past is any indication#not much#for example#i want to go volunteer with afghan refugees#but i know i couldnt handle it#the driving alone would drive me insane#like the other day i was falling apart#walking around cryinf#g#from jusr driving 10 -20 miles/day and pet sitting#those dogs did pull and be kinda naughty...#imagine if it were a bunch of kids all day#but. i want to help#but my ability is. so limited#help!!!!!#maybe i do need to become a different person but idk how bc . i will fall apsrt

124K notes

·

View notes

Link

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

August 18, 2021

Heather Cox Richardson

It is still early days, and the picture of what is happening in Afghanistan now that the Taliban has regained control of the country continues to develop.

Central to affairs there is money. Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries in the world, with about half its population requiring humanitarian aid this year and about 90% of its people living below the poverty line of making $2 a day.

The country depends on foreign aid. Under the U.S.-supported Afghan government, the United States and other nations funded about 80% of Afghanistan’s budget. In 2020, foreign aid made up about 43% of Afghanistan’s GDP (the GDP, or gross domestic product, is the monetary value of all the goods and services produced in a country), down from 100% of it in 2009.

This is a huge problem for the Taliban, because their takeover of the country means that the money the country so desperately needs has dried up. The U.S. has frozen billions of dollars of Afghan government money held here in the U.S. The European Union and Germany have also suspended their financial support for the country, and today the International Monetary Fund blocked Afghanistan’s access to $460 million in currency reserves.

Adam M. Smith, who served on the National Security Council during the Obama administration, told Jeff Stein of the Washington Post that the financial squeeze is potentially “cataclysmic for Afghanistan.” It threatens to spark a humanitarian crisis that, in turn, will create a refugee crisis in central Asia. Already, the fighting in the last eight months has displaced more than half a million Afghans.

People fleeing from the Taliban threaten to destabilize the region more generally. While Russia was happy to support the Taliban in a war against the U.S., now that its fighters are in charge of the country, Russia needs to keep the Taliban’s extremism from spreading to other countries in the area. So it is tentatively saying supportive things about the Taliban, but it is also stepping up its protection of neighboring countries’ borders with Afghanistan. Other countries are also leery of refugees in the region: large numbers of refugees have, in the past, led countries to turn against immigrants, giving a leg up to right-wing governments.

Canada and Britain are each taking an additional 20,000 Afghan women leaders, reporters, LGBTQ people, and human rights workers on top of those they have already volunteered to take, but Turkey—which is governed by strongman president Recep Tayyip Erdogan—is building a wall to block refugees, and French President Emmanuel Macron asked officials in Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey to prevent migrants reaching their countries from traveling any further. The European Union has asked its member states to take more Afghan refugees.

In the U.S., the question of Afghan refugees is splitting the Republican Party, with about 30% of it following the hard anti-immigrant line of former president Donald Trump. Others, though, especially those whose districts include military installations, are saying they welcome our Afghan allies.

The people fleeing the country also present a problem for those now in control of Afghanistan. The idea that people are terrified of their rule is a foreign relations nightmare, at the same time that those leaving are the ones most likely to have the skills necessary to help govern the country. But leaders can’t really stop the outward flow—at least immediately—because they do not want to antagonize the international community so thoroughly that it continues to withhold the financial aid the country so badly needs. So, while on the streets, Taliban fighters are harassing Afghans who are trying to get away, Taliban leaders are saying they will permit people to evacuate, that they will offer blanket amnesty to those who opposed them, and also that they will defend some rights for women and girls.

The Biden administration is sending more personnel to help evacuate those who want to leave. The president has promised to evacuate all Americans in the country—as many as 15,000 people—but said only that we would evacuate as many of the estimated 65,000 Afghans who want to leave as possible. The Taliban has put up checkpoints on the roads to the airport and are not permitting everyone to pass. U.S. military leaders say they will be able to evacuate between 5000 and 9000 people a day.

Today, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark A. Milley tried to explain the frantic rush to evacuate people from Afghanistan to reporters by saying: “There was nothing that I or anyone else saw that indicated a collapse of this army and this government in 11 days.” Maybe. But military analyst Jason Dempsey condemned the whole U.S. military project in Afghanistan when he told NPR's Don Gonyea that the collapse of the Afghan government showed that the U.S. had fundamentally misunderstood the people of Afghanistan and had tried to impose a military system that simply made no sense for a society based in patronage networks and family relationships.

Even with Dempsey’s likely accurate assessment, the statement that U.S. military intelligence missed that a 300,000 person army was going to melt away still seems to me astonishing. Still, foreign policy and national security policy analyst Dr. John Gans of the University of Pennsylvania speculated on Twitter that such a lapse might be more “normal”—his word and quotation marks—than it seems, reflecting the slips possible in government bureaucracy. He points out that the Department of Defense has largely controlled Afghanistan and the way the U.S. involvement there was handled in Washington. But with the end of the military mission, the Defense Department was eager to hand off responsibility to the State Department, which was badly weakened under the previous administration and has not yet rebuilt fully enough to handle what was clearly a complicated handoff. “There have not been many transitions between an American war & an American diplomatic relationship with a sovereign, friendly country,” Gans wrote. “Fewer still when the friendly regime disintegrates so quickly.” When things started to go wrong, they snowballed.

And yet, the media portrayal of our withdrawal as a catastrophe also seems to me surprising. To date, at least as far as I have seen, there have been no reports of such atrocities as the top American diplomat in Syria reported in the chaos when the U.S. pulled out of northern Syria in 2019. Violence against our Kurdish allies there was widely expected and it indeed occurred. In a memo made public in November of that year, Ambassador William V. Roebuck wrote that “Islamist groups” paid by Turkey were deliberately engaged in ethnic cleansing of Kurds, and were committing “widely publicized, fear-inducing atrocities” even while “our military forces and diplomats were on the ground.” The memo continued: “The Turkey operation damaged our regional and international credibility and has significantly destabilized northeastern Syria.”

Reports of that ethnic cleansing in the wake of our withdrawal seemed to get very little media attention in 2019, perhaps because the former president’s first impeachment inquiry took up all the oxygen. But it strikes me that the sensibility of Roebuck’s memo is now being read onto our withdrawal from Afghanistan although conditions there are not—yet—like that.

For now, it seems, the drive to keep the door open for foreign money is reining in Taliban extremism. That caution seems unlikely to last forever, but it might hold for long enough to complete an evacuation.

Much is still unclear and the situation is changing rapidly, but my guess is that keeping an eye on the money will be crucial for understanding how this plays out.

Meanwhile, the former president of Afghanistan, Ashraf Ghani, has surfaced in the United Arab Emirates. He denies early reports that he fled the country with suitcases full of cash.

—-

Notes:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/18/world/asia/ashraf-ghani-uae-afghanistan.html

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/afghanistan/overview

https://asiatimes.com/2021/08/the-root-of-russias-fears-in-afghanistan/

https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2021-07-30qr-section2-economic.pdf#page=14

https://www.reuters.com/article/usa-afghanistan-funding-int/u-s-other-aid-cuts-could-imperil-afghan-government-u-s-watchdog-idUSKBN2B72WJ

https://www.dw.com/en/eu-will-have-to-talk-to-taliban-but-wary-of-recognition/a-58890698

https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2021/08/17/treasury-taliban-money-afghanistan/

https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2021/08/18/business/afghanistan-lithium-rare-earths-mining/index.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/russia-taliban-afghanistan-putin/2021/08/17/af53a9ec-ff4c-11eb-87e0-7e07bd9ce270_story.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/08/18/afghanistan-kabul-taliban-live-updates/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/aid-groups-warn-of-possible-refugee-crisis-in-afghanistan-far-beyond-western-evacuation-plans/2021/08/18/0d7094fc-0058-11ec-825d-01701f9ded64_story.html

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/21/1008656321/how-does-the-u-s-help-afghans-hold-on-to-gains-while-withdrawing-troops

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/08/18/afghanistan-kabul-taliban-live-updates/

https://www.reuters.com/world/canada-accept-20000-vulnerable-afghans-such-women-leaders-human-rights-workers-2021-08-13

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/07/us/politics/memo-syria-trump-turkey.html

https://www.politico.com/news/2021/08/18/afghan-refugee-debate-fractures-gop-506135

https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/18/politics/us-must-rely-on-taliban-for-evacuation/index.html

John Gans @johngansjrFrom what I'm seeing and hearing, the reasons for the mess in Afghanistan might be far more 'normal' than many are suspecting/suggesting -- driven more by typical pathologies in government & Washington. More to be learned. But a few thoughts. 1/x

533 Retweets2,195 Likes

August 18th 2021

https://www.npr.org/2021/08/15/1027952034/military-analyst-u-s-trained-afghan-forces-for-a-nation-that-didnt-exist

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Today, Exarchia is a graffiti-bedecked anarchist stronghold, home to squats, cafés, bookstores, and social centers—to the self-managed Navarinou Park, where, in 2009, anarchists wrested gardens from a broken concrete parking lot, and to Steki Metanaston, the twenty-year-old bar founded by leftist organizers and immigrants. Because police seldom ventured beyond Exarchia’s outskirts, and anti-fascist groups have made the neighborhood a no-go zone for members of the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn, Exarchia’s streets have also long been an oasis for immigrants without papers. After the mass arrival of refugees in 2015, anarchists teamed up with migrant activists, to provide refugees with a roof over their heads while they waited for smugglers to help them reach the German promised land. In the years since, thousands of refugees lived in squats in and around the neighborhood. Walid, an undocumented Afghan man, told me, “Exarchia is a super-nice place. It is peaceful for me here—there is no one to arrest me.”

Recently, drug cartels began to take advantage of this freedom. Cartel leadership was largely European, but many of the dealers who worked Exarchia Square were impoverished men from North Africa and the Middle East. Ecstasy, weed, and cocaine were the drugs of choice, sold to European tourists by youths with frayed nerves and elaborately jelled hairdos. When I stayed at a hotel off the square last year, fights between rival gangs woke me up most nights. Conservative media blurred together the figures of anarchist, refugee, and dealer into a spectre of degeneration. An article in EleftherosTypos, written after the Spirou Trikoupi raid, described raids on squats and raids on drug dealers as part of a single effort to “limit the phenomena of delinquency and drug trafficking.”

[...]

Once some E.U. borders slammed shut in 2016, refugees who had hoped to eventually reach Berlin, or Stockholm, or London, were in Athens indefinitely. The squats became more than waystations; they represented the first stability that refugees had known in years. Refugee children went to school, and their parents worked, shopped, and socialized in the neighborhood. I sketched kids in Jasmine School, a squat near Exarchia, that had been shut in the latest round of raids. The building was a leaky Beaux-Arts wreck, without reliable power or water, but volunteers had provided piles of food, clothing, and medicine, and the residents cooked a collective lunch to the sounds of the Lebanese diva Fairuz. Spirou Trikoupi had a bar, a library, children’s classes, and weekly assemblies. “Ninety people were building a common life together, in a community that was alive,” one activist told me. “Day by day, we were becoming better by learning from our mistakes.”

Walid, a law-school graduate from Kabul who had spent almost two years in Trikoupi, spoke about his time there with a sense of loss. He had spent ten days sleeping on the streets with his wife and his child when a friend told him about the squat. Once installed, he took easily to the anarchist model of boss-free self-organization. Trikoupi “was like a village, but with different nationalities,” he told me, smiling gently. There were weekly assemblies, residents’ committees to clean and protect the building. “I learned many things about how to live, to help each other,” he said. “We had rules: no sexism, no racism, no fascism, no violence.”

When Walid heard the police outside Trikoupi’s door, he knew he had to run. He led a group of Eritrean girls to a nearby balcony, where they hid for hours under the hot sun, with only dirty water to drink. “They destroyed everything and showed video to media. The media says anarchists use refugees, that they put us in a bad place that is dirty. Not true!” Walid said, his voice rising with indignation. After the raid, he had nothing but the clothes he had worn. He has been staying at a space belonging to friends, along with the other refugees who escaped the raid. On social media, activists posted photos of a hastily built camp, in Corinth, where many of those who were caught were sent—white tents marooned in a mud field. “My friends in the camps miss Trikoupi a lot,” Walid told me. “We want to come back.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

adding: Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and Annunciation House

some other places to donate to for immigration rights/advocacy in addition to RAICES

Young Center for Immigrant Children's Rights

Haitian Immigrant Bail Assistance Project

Val Verde Border Humanitarian Coalition

Black Freedom Factory

Texas Civil Rights Project

and more

#hope it's okay to add a couple more op#w/ love from your friendly border city dweller who volunteers a lot with groups that are actually on the ground doing work on the border#i think they're both catholic orgs which take as you will but these are the go to's in el paso for when the city needs resources asap#especially annunciation house they're like practically an extension of the city in terms of migrant hospitality#and las americas especially is very grassroots i give all my spare money to them basically#i would also add my job's sister nonprofit which does similar work but then you might ~find me~ so just dm if you want another option#el paso has received several thousand haitian asylees to be processed since we have well-equipped cpd centers here#and in addition we have thousands of afghan refugees in camps on our local army base plus an unaccompanied minors shelter on base#and that's all in addition to the literally countless number of central american migrants being forced to wait in mexico for their asylum#cases due to title 42#you can read more about our situation on the las americas website!!

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almost every morning on my commute to work, I would blast Will Reagan and UP’s “Looking for a Saviour” on repeat, and there’s always that stand out lyric in the chorus that I never quite understood, “May a broken God be known.” Wait, but how could perfection be broken?

God is not broken in the way that He needs to be fixed. Rather, He is like a beautiful oxymoron. He is both the Lion and the Lamb. He came as fully human, but still fully God. A divine King who takes on the brokenness of man. That’s how Nathan Fray (co-founder of United Pursuit) explained it.

I take that the song is generally about the addiction to certainty, and truth. I listen to this song and I am always brought back to August 2017, when a couple of friends and I flew off to Greece. We visited Athens, but stayed on the island of Lesvos for 3 weeks, serving at a refugee camp that held the very brokenness of man.

There were days at this camp where my faith really wavered. The stories were heartwrenching, the camp was overpopulated, the tension between people groups was nerve-racking for such a reason that a fight could break out at any moment. You could feel the hopelessness linger on your skin, even when your shift was over. I was warned about what I was walking into, and I have read and seen so many photos or footage online, I thought I was prepared. They say cameras add 10 pounds, but the heaviness you felt walking through those gates was completely raw and overwhelming. I don’t think any type of warning could prepare you for the moment you enter Moria. You walk in the camp, a former prison. Gates after gates. Volunteers as guards. Barbwires. Cargo containers. Tents on the road. The scent of feces, garbage, and dust. First week in, my questions were growing more than my faith was. “Where are you God?” I expected Him to hold my hand because I needed Him to be more tangible than ever.

Then He came to me, but in the form of a 2 year old Syrian girl who actually held my hand, and begged for me to carry her. She sat with me most days when I needed to guard her gate. She played with me, and sat on my lap with her leaky poopy diaper. She’d cry to me when her older brother would be unfair. Her cunning little smirk that always meant she was about to run away to make me chase her. Her and her family moved to another camp, a safer one, thankfully. I never got to say goodbye, but she left a lasting mark. I still pray that the family is having a much a better life than the one they had to leave behind.

But I saw God in that camp. I saw Him in those men, women, and children begging for more food, more water, or more milk formula for their new borns. I saw Him in the Yemeni woman who helped translate for a stranger having a panic attack. I saw Him in the little boys wanting you to play soccer, shouting from afar, “my friend, my friend!” I saw Him in the older Afghan woman who carried her autistic child on her back up a steep hill. I saw Him in the young girl who’d greet me with a warm embrace and a kiss on the cheek. I saw Him in the man who would dance and sing to make me laugh. The man who built shade over my head when the day got hot. I saw God in the man teaching me Farsi, the man teaching me Kurdish, and the little boy teaching me Arabic. I saw Him in the face of the man who had scars on his wrists, with a little hope in his eyes. In the restless. The numb. The grieving. The joyful. The hopeful. I saw God but in that broken way, where even though He is Lord, He is also “the least of the these.”

Humanity is broken, but I acknowledge that I am merely cracked. As in, I live a very comfortable life and I complain that it is too mundane. I live in one of the most livable cities on Earth, and yet some days I’m still itching to leave. I was born into a life of privilege. I’ve never had to worry about my family or my own life being taken out by a bomb. I’ve never had to flee my country because it was safer anywhere else. It is actually easier for me to fix my “first world problems” than those whose lives have completely shattered. There’s just no reason why I would deserve any basic need more than anyone else. “I worked hard for this life” belittles the hardworking teacher I met whose classroom fell apart over his head due to a bomb attack. Or the man who was an activist and advocate for women’s rights and had to flee his country because that would have gotten him killed. The doctor, the pharmacist, or the entrepreneur of a soap company. It is not fair to the little Syrian girl who is now here, getting her ears checked almost every month because she lost her hearing at 4 years old due to a bomb that nearly took her life. I cannot look her in the eyes and tell she doesn’t deserve these treatments. It’s not fair to the Syrian family that lost their little girl to suicide due to bullying. I cannot even look her mother in the eyes, because they did not leave a place of despair only to find it again here.

We don’t need to go to a war-torn country, or volunteer in a refugee camp to realize that the time is now. We are in a time of adversity and tension. So the time is now. We start to bridge that gap, we mend that brokenness, and we end that division. That we stop holding an entire religion or people group to the poor representation on our televisions. There is still something common amongst us all and that is kindness, compassion, goodness, warmth, pain, grief, and empathy.

As countries are crying out for mercy. Christian’s, my heart is that we would bring what comes after this down, in the here and now; the beautiful picture of every tribe, every tongue, every nation. No wall, all barriers broken. Truly believing that there is beauty in the making, and firmly believing that every tear will be wiped away. We refuse to let evil get the last word and refuse to accept weariness and division be our world’s narrative. In 2020, I want to believe in the beautiful transformation of the Jericho Road to a restored Garden of Eden. Will you believe, act, and pray with me?

1 note

·

View note

Link

Washington: The nation’s top national security officials assembled at the Pentagon early on April 24 for a secret meeting to plan the final withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan. It was two weeks after President Joe Biden had announced the exit over the objection of his generals, but now they were carrying out his orders.

In a secure room in the building’s “extreme basement,” two floors below ground level, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and Gen. Mark Milley, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, met with top White House and intelligence officials. Secretary of State Antony Blinken joined by video conference. After four hours, two things were clear.

First, Pentagon officials said they could pull out the remaining 3,500 U.S. troops, almost all deployed at Bagram Airfield, by 4 July — two months earlier than the 11 September deadline Biden had set. The plan would mean closing the airfield that was the US military hub in Afghanistan, but Defense Department officials did not want a dwindling, vulnerable force and the risks of service members dying in a war declared lost.

Second, State Department officials said they would keep the US Embassy open, with more than 1,400 remaining Americans protected by 650 Marines and soldiers. An intelligence assessment presented at the meeting estimated that Afghan forces could hold off the Taliban for one to two years. There was brief talk of an emergency evacuation plan — helicopters would ferry Americans to the civilian airport in Kabul, the capital — but no one raised, let alone imagined, what the United States would do if the Taliban gained control of access to that airport, the only safe way in and out of the country once Bagram closed.

The plan was a good one, the group concluded.

Four months later, the plan is in shambles as Biden struggles to explain how a withdrawal most Americans supported went so badly wrong in its execution. On Friday, as scenes of continuing chaos and suffering at the airport were broadcast around the world, Biden went so far as to say that “I cannot promise what the final outcome will be, or what it will be — that it will be without risk of loss.”

Interviews with key participants in the last days of the war show a series of misjudgments and the failure of Biden’s calculation that pulling out US troops — prioritising their safety before evacuating US citizens and Afghan allies — would result in an orderly withdrawal.

Biden administration officials consistently believed they had the luxury of time. Military commanders overestimated the will of the Afghan forces to fight for their own country and underestimated how much the American withdrawal would destroy their confidence. The administration put too much faith in Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, who fled Kabul as it fell.

And although Biden White House officials say that they held more than 50 meetings on embassy security and evacuations and that so far no Americans have died in the operation, all the planning failed to prevent the mayhem when the Taliban took over Kabul in a matter of days.

Only in recent weeks did the administration change course from its original plan. By then it was too late.

A sinking feeling

Five days after the April meeting at the Pentagon, Milley told reporters on a flight back to Washington from Hawaii that the Afghan government’s troops were “reasonably well equipped, reasonably well trained, reasonably well led.” He declined to say whether they could stand on their own without support from the United States.

“We frankly don’t know yet,” he said. “We have to wait and see how things develop over the summer.”

Biden’s top intelligence officers echoed that uncertainty, privately offering concerns about the Afghan abilities. But they still predicted that a complete Taliban takeover was not likely for at least 18 months. One senior administration official, discussing classified intelligence information that had been presented to Biden, said there was no sense that the Taliban were on the march.

In fact, they were. Across Afghanistan, the Taliban were methodically gathering strength by threatening tribal leaders in every community they entered with warnings to surrender or die. They collected weapons, ammunition, volunteers and money as they stormed from town to town, province to province.

In May, they launched a major offensive in Helmand province in the south and six other areas of Afghanistan, including Ghazni and Kandahar. In Washington, refugee groups grew increasingly alarmed by what was happening on the ground and feared Taliban retribution against thousands of translators, interpreters and others who had helped the American war effort.

Leaders of the groups estimated that as many as 100,000 Afghans and family members were now targets for Taliban revenge. On May 6, representatives from several of the United States’ largest refugee groups, including Human Rights First, the International Refugee Assistance Project, No One Left Behind, and the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service logged onto Zoom for a call with National Security Council staff members.

The groups pleaded with the White House officials for a mass evacuation of Afghans and urged them not to rely on a backlogged special visa program that could keep Afghans waiting for months or years.

There was no time for visas, they said, and Afghans had to be removed quickly to stay alive. The response was cordial but noncommittal, according to one participant, who recalled a sinking feeling afterward that the White House had no plan.

Republican Seth Moulton, D-Mass., a veteran and an ally of Biden's, echoed those concerns in his own discussions with the administration. Moulton said he told anyone who would listen at the White House, the State Department and the Pentagon that “they need to stop processing visas in Afghanistan and just get people to safety.”

But doing what Moulton and the refugee groups wanted would have meant launching a dangerous new military mission that would probably require a surge of troops just at the moment that Biden had announced the opposite. It also ran counter to what the Afghan government wanted, because a high-profile evacuation would amount to a vote of no confidence in the government and its forces.

The State Department sped up its efforts to process visas and clear the backlog. Officials overhauled the lengthy screening and vetting process and reduced processing time — but only to under a year. Eventually, they issued more than 5,600 special visas from April to July, the largest number in the program’s history but still a small fraction of the demand.

The Taliban continued their advance as the embassy in Kabul urged Americans to leave. On 27 April, the embassy had ordered nearly 3,000 members of its staff to depart, and on 15 May, officials there sent the latest in a series of warnings to Americans in the country: “U.S. Embassy strongly suggests that U.S. citizens make plans to leave Afghanistan as soon as possible.”

A tense meeting with Ghani

On 25 June, Ghani met with Biden at the White House for what would become for the foreseeable future the last meeting between an American president and the Afghan leaders they had coaxed, cajoled and argued with over 20 years.

When the cameras were on at the beginning of the meeting, Ghani and Biden expressed mutual admiration even though Ghani was fuming about the decision to pull out US troops. As soon as reporters were shooed out of the room, the tension was clear.

Ghani, a former World Bank official whom Biden regarded as stubborn and arrogant, had three requests, according to an official familiar with the conversation. He wanted the United States to be “conservative” in granting exit visas to the interpreters and others, and “low key” about their leaving the country so it would not look as if America lacked faith in his government.

He also wanted to speed up security assistance and secure an agreement for the US military to continue to conduct airstrikes and provide overwatch from its planes and helicopters for his troops fighting the Taliban. US officials feared that the more they were drawn into direct combat with the militant group, the more its fighters would treat US diplomats as targets.

Biden agreed to provide air support and not make a public show of the Afghan evacuations.

Biden had his own request for Ghani. The Afghan forces were stretched too thin, Biden told him, and should not try to fight everywhere. He repeated American advice that Ghani consolidate Afghan forces around key locations, but Ghani never took it.

A week later, on 2 July, Biden, in an ebullient mood, gathered a small group of reporters to celebrate new jobs numbers that he said showed that his economic recovery plan was working. But all the questions he received were about news from Afghanistan that the United States had abandoned Bagram Airfield, with little to no notice to the Afghans.

“It’s a rational drawdown with our allies,” he insisted, “so there’s nothing unusual about it.”

But as the questions persisted, on Afghanistan rather than the economy, he grew visibly annoyed. He recalled Ghani’s visit and said, “I think they have the capacity to be able to sustain the government,” although he added that there would have to be negotiations with the Taliban.

Then, for the first time, he was pressed on what the administration would do to save Kabul if it came under direct attack. “I want to talk about happy things, man,” he said. He insisted there was a plan.

“We have worked out an over-the-horizon capacity,” he said, meaning the administration had contingency plans should things go badly. “But the Afghans are going to have to be able to do it themselves with the air force they have, which we’re helping them maintain,” he said. But by then, most of the U.S. contractors who helped keep the Afghan planes flying had been withdrawn from Bagram along with the troops. Military and intelligence officials acknowledge they were worried that the Afghans would not be able to stay in the air.

By 8 July, nearly all US forces were out of Afghanistan as the Taliban continued their surge across the country. In a speech that day from the White House defending his decision to leave, Biden was in a bind trying to express skepticism about the abilities of the Afghan forces while being careful not to undermine their government. Afterward, he angrily responded to a reporter’s comparison to Vietnam by insisting that “there’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of an embassy of the United States from Afghanistan. It is not at all comparable.”

But five days later, nearly two dozen U.S. diplomats, all in the Kabul embassy, sent a memo directly to Blinken through the State Department’s “dissent” channel. The cable, first reported by The Wall Street Journal, urged that evacuation flights for Afghans begin in two weeks and that the administration move faster to register them for visas.

The next day, in a move already underway, the White House named a stepped-up effort “Operation Allies Refuge.”

By late July, General Kenneth McKenzie Jr., head of US Central Command who overseas all military operations in the region, received permission from Austin to extend the deployment of the amphibious assault ship Iwo Jima in the Gulf of Oman, so that the Marines on board could be close enough to get to Afghanistan to evacuate Americans. A week later, Austin was concerned enough to order the expeditionary unit on the ship — about 2,000 Marines — to disembark and wait in Kuwait so that they could reach Afghanistan quickly.

By 3 August, top national security officials met in Washington and heard an updated intelligence assessment: Districts and provincial capitals across Afghanistan were falling rapidly to the Taliban and the Afghan government could collapse in “days or weeks.” It was not the most likely outcome, but it was an increasingly plausible one.

“We’re assisting the government so that the Talibs do not think this is going to be a cakewalk, that they can conquer and take over the country,” the chief US envoy to Afghan peace talks, Zalmay Khalilzad, told the Aspen Security Forum on 3 August. Days later, however, that is exactly what happened.

The end game

By 6 August, the maps in the Pentagon showed a spreading stain of areas under Taliban control. In some places, the Afghans had put up a fight, but in many others, there was just surrender.

That same day in Washington, the Pentagon reviewed worst-case scenarios. If security further deteriorated, planning — begun days after Biden’s withdrawal announcement in April — led by Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, the president’s homeland security adviser, called for flying most of the embassy personnel out of the compound, and many out of the country, while a small core group of diplomats operated from a backup site at the airport.

On its face, the Kabul airport made sense as an evacuation point. Close to the centre of the city, it could be as little as a 12-minute drive and a three-minute helicopter flight from the embassy — logistics that had helped reassure planners after the closure of Bagram, which was more than 50 miles and a far longer drive from Kabul.

By 11 August, the Taliban advances were so alarming that Biden asked his top national security advisers in the White House Situation Room if it was time to send the Marines to Kabul and to evacuate the embassy. He asked for an updated assessment of the situation and authorised the use of military planes for evacuating Afghan allies.

Overnight in Washington, Kandahar and Ghazni were falling. National security officials were awakened as early as 4 am on 12 August and told to gather for an urgent meeting a few hours later to provide options to the president. Once assembled, Avril Haines, director of national intelligence, told the group that the intelligence agencies could no longer ensure that they could provide sufficient warning if the capital was about to be under siege.

Everyone looked at one another, one participant said, and came to the same conclusion: It was time to get out. An hour later, Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, walked into the Oval Office to deliver the group’s unanimous consensus to start an evacuation and deploy 3,000 Marines and Army soldiers to the airport.

By 14 August, Biden was at Camp David for what he hoped would be the start of a 10-day vacation. Instead, he spent much of the day on dire video conference calls with his top aides.

On one of the calls, Austin urged all remaining personnel at the Kabul embassy be moved immediately to the airport.

It was a stunning turnaround from what Ned Price, the State Department spokesperson, had said two days earlier: “The embassy remains open, and we plan to continue our diplomatic work in Afghanistan.” Ross Wilson, acting US ambassador to Afghanistan and who was on the call, said the staff still needed 72 hours to leave.

“You have to move now,” Austin replied.

Blinken spoke by phone to Ghani the same day. The Afghan president was defiant, according to one official familiar with the conversation, and insisted that he would defend Afghanistan until the end. He did not tell Blinken that he was already planning to flee his country, which US officials first learned by reading news reports.

Later that day, the US Embassy in Afghanistan sent a message saying it would pay for American citizens to get out of the country, but warned that although there were reports that international commercial flights were still operating from Kabul, “seats may not be available.”

On 15 August, Ghani was gone. His departure — he would eventually turn up days later in the United Arab Emirates — and scenes of the Taliban celebrating at his presidential palace documented the collapse of the government.

By the end of the day, the Taliban addressed the news media, declaring their intention to restore the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

The evacuation of the Kabul embassy staff was by that point underway as diplomats rushed to board military helicopters for the short trip to the airport bunker.

Others stayed behind long enough to burn sensitive documents. Another official said embassy helicopters were blown up or otherwise destroyed, which sent a cloud of smoke over the compound.

Many Americans and Afghans could not reach the airport as Taliban fighters set up checkpoints on roads throughout the city and beat some people, leaving top FBI officials concerned about the possibility that the Taliban or criminal gangs might kidnap Americans, a nightmare outcome with the US military no longer in the country.

As Biden made plans the evening of 15 August to address Americans the next day about the situation, the American flag was lowered over the abandoned embassy. The Green Zone, once the heart of the American effort to remake the country, was again Taliban territory.

Michael D Shear, David E Sanger, Helene Cooper, Eric Schmitt, Julian E Barnes and Lara Jakes c.2021 The New York Times Company

from Firstpost World Latest News https://ift.tt/3grNLui

0 notes

Photo

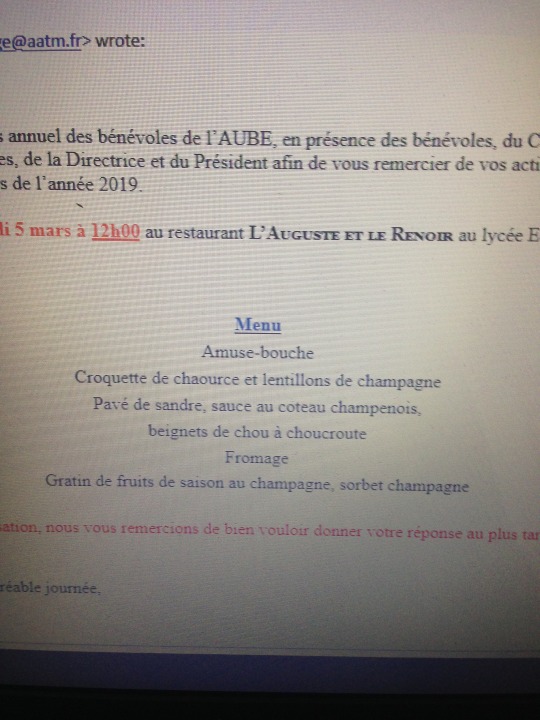

Bonjour a tous, you may well be wondering where I have been for the last two weeks. Well I have been having a well deserved beach holiday, staying in a wonderful hotel and enjoying 10 days of sunshine and heat. This was just what the doctor ordered as I have returned home feeling wonderfully refreshed and amazed by my accomplishments. Plenty of massages and a first for at least six years, I managed to walk into a pool and swim. I cannot begin to tell you how liberating that felt, to feel light, to float, to actually jump/hop in the water as well as swimming, plus being a thalassotherapy pool my whole body felt so refreshed. Then I was back home to some sun, some rain and cooler temperatures. I arrived back on Tuesday, and had a full diary for the remainder of the week. It was my knitting group on Wednesday, unfortunately, best friend Marlene was not there so no schoolgirl giggles were coming from the corner of the room. It was really lovely though to be back in a group and although my head was not into my complicated knitting, it was still a wonderful afternoon. Then it was another highlight for the week, the meal for the volunteers in Troyes. My friend Anie was the “chauffeur” and although it was absolutely pouring down with rain we arrived, just in time to be seated, and what a wonderful meal it was. I had champagne, white wine and red wine with my meal and am ashamed to say I fell asleep in the car coming home. I had been due to attend this last year with Monique, but she was unwell, so we didn’t go. I realise now what a treat I missed out on. Note to self: don’t make that mistake again! Before I knew it Friday was with us and the weekend beckoning. I had an appointment for a pedicure on the morning, my plan was pedicure, drop into the bar to say hello and have a coffee. Well as they say, the best laid plans….. I was with the podiatrist for an hour, where we talked, laughed and joked. She likes to speak English to me and I learn a lot as she gives me French words which I have to translate, as I was leaving she said that she is looking forward to me going again as we have such good chats. As a result of being there for an hour it meant that I had to forego the bar and just go home to prepare lunch as I had knitting with refugees in the afternoon. I arrived at the “knitting workshop” as it is named and at first just the Afghan lady was there, she was going to the physiotherapist but just before she left the Angolan lady came with her daughter, then the Georgian lady arrived, next was the Kuwaiti lady, with her young daughter, she arrived with a plate of wonderful hot finger food, I have no idea what it was called but it tasted delicious. The last to arrive was the Turkish lady and then there we were all talking, eating, knitting and generally just having a laugh too. This group has turned into what I had really hoped it would be, a place for these women to leave their home, husband and family and just sit and natter for an hour and a half. The fact that they bring food to share is just an added bonus and I am so happy I agreed to give my time for this. Then I hoped to catch 40 winks before I had dinner and headed off to the Orchestre Symphonique de L’Aube concert for the 250th birthday of Beethoven. 40 winks I did not have, I really hoped I would not nod off during the concert. I managed to get one of the seats with a high padded back and although Anie preferred to sit with her friend on the row in front we all managed a chat before and at the interval. The concert finished at 10pm which is very late for me to be out with the car. Saturday arrived and my plan was to go and get some fresh food and prepare something tasty. Shopping took all morning as I wanted to visit 3 shops and it was the collection day for Les Restos du Coeur (food bank). As I was driving home I decided to make a quiche, so called and got the pastry. What a lovely meal I had, broccoli, onion and fennel quiche with homemade coleslaw sans mayonaisse. I had tried, unsuccessfully, to see Anie today. I had bought her some chocolates and flowers for being the chauffeur. Well the flowers are in my vase now and the chocolates are in the car ready for when I can call to see her. Today, is l’anniversaire de ma belle-fille, and in just 9 days time her, my son and my gorgeous granddaughter will arrive. To say I am excited is an understatement. I hope she has a wonderful birthday with her family. The Graduate, has been keeping busy with the course he is doing this year. He has also downloaded “Duolingo” so that he can practice his French. I don’t want that to interfere with his studies but it is giving him an “outlet” and that must be a good thing. He is really hoping to come over and see me again in the summer. Oh while I remember “Hello to all my friends in Newcastle, keep up the good work”. Have a great week, until next week. Ciao.

0 notes

Photo

It was 16th of June 2016. In a few hours I was flying to India. It had five years away from India, home, friends and family. I wanted nothing but time to fly. ------------------------ That morning, I bumped into Sofia from Switzerland. The Japanese call it "Koi No Yokan" - The extraordinary sense upon meeting someone that you will fall in love one day. It was that kind of instant connection. We spoke for hours at a cafe. I wanted time to stand still. Then she told me, "Varun, you must go to the Afghan Park. That's where you will me Syrian, Iraqi and Afghan refugees. It's your kind of place." ----------------------- 30 Minutes later, I was there talking to refugees from the Middle East and Afghanistan. Their half-told stories were intriguing. That day, I also met Hesham, a volunteer helping the refugees. I once again wanted time to stop ticking. I wanted to hear all their stories but there was that flight back home. ---------------------- I told Hesham, "I will come back one day." — view on Instagram http://bit.ly/2YTXZbz

0 notes

Text

The quest for Britain: Away from the media spotlight, Calais reaches breaking point

By Marta Welander

A bottle-neck scenario has been unfolding in Northern France for decades, characterised by rough-sleeping, dangerous border-crossings and a heavy-handed police response. But instead of working to facilitate the safe passage for asylum seekers and seeing if they can be reunited with their family here, the British government has instead funded an inhumane approach implemented by the French state. Securitisation is pursued and barbed wire put up, instead of humanitarian aid or protection. Reports from the ground indicate that the situation is currently at crisis point. Instead of investing in much needed accommodation, the UK has just contributed additional sums to the construction of razor wire fences and increased surveillance. The French police continue to dismantle, evict and push individuals away. On March 12th, the largest encampment was evicted by French authorities, leaving hundreds of people with nowhere to go. Smaller encampments are continuously removed. Tents are destroyed and personal belongings confiscated, including much needed mobile phones and important documents. Aid groups on the ground are working ceaselessly to provide tents, sleeping bags and hot meals to the individuals in the area, but they're being stretched to their limits. The charitable supplies are continuously depleted and require increased donations to survive. One Afghan man told human rights researchers: "The police take the tents away all the time and the volunteers don't even have time to replace the tents as fast as the police takes them."

The risk of death is ever-present. On March 18th, a 19-year-old Ethiopian boy named Kiyar lost his life in a lorry in Calais, while desperately trying to reach the UK where he had extended family. Kiyar is the first known person to have died at the border this year, but it's not a rare occurrence. At least 197 deaths are reported to have occurred between 1999 and 2017. The real number is probably much higher, as many deaths go unreported. Like Kiyar, many others are trying to join loved once across the Channel in the UK. An Iranian man sleeping rough in Calais explained his predicament: "I have a child and my wife in England. Every day I hope to reach the UK."

Human rights groups such as Refugee Rights Europe (RRE) have raised widespread concerns regarding the individuals held in the Centre Administratif De Rétention detention centre in Coquelles. One former Sudanese detainee interviewed by the rights group said: "They wanted me to give my fingerprints and ask for asylum in France but I think they just want to have a fast process and send me back to Sudan. I want to go to UK where I have family members. In detention, I did not eat for several days. I was exhausted and my morale was going down every day." RRE reported that detainees have gone on hunger strike, with a number attempting suicide in early April.

Just behind the heavy-handed and inhumane French approach lies vast quantities of British funding. In January 2018, an unpublished government briefing estimated that around £100 million had been spent on security measures at French Channel border points in the previous three years. As part of the Sandhurst agreement in January 2018, another £44.5 was allocated to "reinforce the security infrastructure", bringing the total figure to around £150 million.

The approach has been incredibly costly and almost completely ineffective. It is high time for meaningful change. The UK government has a responsibility to uphold the human rights of displaced people in Northern France, many of whom have a legal right to come to the UK, and ensure that British funding is under no circumstances used to violate human rights. It also has a duty to uphold the right to claim asylum under national and international law and offer protection to those who need it.

We need a new approach centred around finding constructive solutions through effective communication channels, legal guidance and health and safety provisions. It is possible. But the government seems set instead on expensive and inhumane alternatives.

0 notes

Text

The Sick Old Man of Europe

Its about time that Recep Tayyip Erdogan must be put into his proper place

I’ve posted before how the Christchurch tragedy would have huge consequences due people using it to advance their personal agenda, but I must admit: I was rather shocked at what selfish lows Erdogan would go. During an election rally in Izmir, the Turkish dictator showed video footage of the massacre to an open crowd, something which the Western media has been trying to censor desperately for good reason. His reasoning is that the NZ terrorist wanted Turks removed from Europe, thereby presenting the voters with an “us vs them” mentality and essentially telling them “I am the only one who can protect you from this, so if you know what is good for you, then vote for me”. Not content with this, he has pressured New Zealand to execute the terrorist in custody and has basically threatened any New Zealander tourists with we will send you back home in coffins like we done to your ancestors in Gallipoli.

He probably took it more personally this time since the terrorist called for his death in his manifesto and he is in full-blown panic mode knowing that someone who wanted him dead slipped inside his country - oh the horror, nevermind the possibility of an white supremacist actually killing him is less likely than a radicalized Kurdish militant. He really wants that nutter dead despite him being in no position to harm anyone else or ever getting out and that is not if someone actually kills him inside and promised that he will take necessary action if New Zealand doesn’t cave to his demands. Many outsiders will say that he is just spewing a lot of hot air, but I think many outsiders - even those who are also critical of him - really underestimate the real danger he represents.

Coming from an Islamist background, Erdogan’s greatest dream was to relive the glories of the Ottoman Empire’s past which is reflected on his policy referred to as “Neo-Ottomanism”. After the Turkish sultan Selim the Grim defeated the Mamluks in 1517, the Ottoman Empire was elevated from an realm at the margins of the Islamic world from being in charge of it, ruling their most important seats of power such as Cairo, Aleppo, Mecca and Medina. As such they were recognized as a caliphate and their leader was regarded as the successor of the Prophet Muhammad and the spiritual leader of Muslims worldwide.

Despite their prestigious position, it was just a nice new title the Ottomans held in their long list and even then their authority was questioned for a number of reasons: for one, the caliph is supposed to be elected among the most capable and pious leaders while the Ottomans were infamous for relying on fratricide, having the prospective sultans killing their brothers to get to the throne (they later changed it to imprisonment or exile). Otherwise, they functioned like a typical Islamic absolute monarchy and they really wouldn’t adopt a policy of pan-Islamism until much later after their decline really began and they were referred to as the “sick old man of Europe”. Despite being in charge of the Empire, Turks only compromised a minority of its Muslim population while Arabs were the majority and they promoted Islam as the one thing tying them together in an attempt to counter nationalism in Europe.

Rather than trying to restore the House of Osmanoglu (the descendants of Osman who founded the dynasty that ruled over an uninterrupted line over the empire since its foundation until Ataturk abolished the caliphate) back to power, Erdogan wants to do right what his predecessors have failed and recreate an Neo-Ottoman Empire based on what should have been and declare himself caliph by the correct application of Islam. He has worked all of his life with Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood and some pleasant people like Afghan warlord Gulbuldin Hekmatyar (an well-known genocide perpetrator against the Hazara people and responsible for spraying acid on women for being unveiled) to plant the seeds necessary so that he could be recognized as the new caliph of all Muslims. He had spent a good time also antagonizing the Gulf States specially Saudi Arabia whose kings serve as Custodians of the Two Holy Places. But make no mistake, just because the Saudis are promoters of a fundamentalist brand of Islam it doesn’t make Erdogan less of an fundamentalist himself - he just sees Wahhabism/Salafism as a rivals to his conservative Islam.

That opportunity finally came when the Arab Spring erupted. Erdogan was part of the international powers that formed an alliance to strike Libya. When Libya fell, followed by Tunisia and Egypt falling into the hands of Islamists, he rushed to pay these countries a visit and portraying himself as defender of all Muslims to get into their good graces. He spread his influence even further offering to build mosques in Albania, something which local Muslims found outrageous because they despise the memories of being under Ottoman occupation.

However, he left all pretense and reason behind when it became obvious that Syria was not easily succumbing to the Muslim Brotherhood. He turned Turkey’s borders with Syria into an assembly of hardened terrorists brought in from all over the world, equipped with weapons and funds and aiming to bring Bashar Al-Assad down. Finally, the collapse of the Muslim Brotherhood rule in Egypt seemed to have pushed him over the edge.

Most realists will coincide that he is a necessary evil since as a NATO member the West can’t afford to have him as an enemy - case in point, the main reason why Israel hasn’t recognized the Armenian Genocide is because Turkey is one of the few Muslim nations they consider as allies in the region. I really must question Erdogan’s reliability as an ally:

Consider that Turkey has avoided confronting ISIS directly in order to let them fight the Kurds and the Assad government.

Consider that Turkey has allowed Western volunteers to cross the border to join ISIS.

Consider Turkey has also supported jihadist groups that are no different than ISIS.

Consider that several people (such as Iraq’s Prime Minister, the King of Jordan and the Hezbollah leader) have accused Turkey of outright backing ISIS.

Consider that Hamas implied that Turkey backs ISIS when they refused to denounce them when they burned the Jordanian pilot alive saying that Jordan had no business fighting them and they should have taken Turkey’s position instead.

Of course, I will admit this is circumstantial evidence and conjectural “he said, she said”. Some will point out that Turkey held the biggest number of Syrian refugees since the civil war more so than Europe itself which has struggled with the migrant crisis, but its clear that Erdogan doesn’t hesitate to weaponize them when it suits him such as when he threatened to evict all refugees into Europe in case they don’t play ball with him. And this is the reason why I made this blog. He must be disciplined for his arrogance and short temper.

Its pretty self-evident to outsiders that he is a dictator. His apologists will quickly come to his defense and say that he was democratically elected with 80% of the public support, which is a really tepid response. Nevermind how the electoral race was heavily skewed in one’s favor, I find almost comical that Erdogan supporters would hold democracy as an valid argument for him considering that he once served time in jail for declaring:

"Democracy is merely a train that we ride until we reach our goal. Mosques are our military barracks, minarets are our spears, and domes are our helmets.”

Looking at today’s Turkey, it’s very hard to believe that he regrets saying these words when he was mayor of Constantinople. Furthermore, the mark of an dictatorial regime is authoritarianism. Political dissidents, critics and journalists are jailed with staggering frequency, subjected to torture, rape and abuse that honestly makes the abuse in Abu Ghurab look tame and his outrage at it hypocritical in hindsight. Just imagine: Turkey arrests more journos than Saudi Arabia itself.

Erdogan is incapable of taking criticism, which is why he gives a platform for the Muslim Brotherhood members to criticize the current Egyptian government for overthrowing Mohammed Morsi because they pay lip service to him, all while jailing any journalist that publishes anything he dislikes on the excuse of “promoting terrorism” and it must strike him something fierce knowing not being able to do as he wills wherever he wants.

For all the shit that people pins on Donald Trump, Erdogan manages to be even less tactless and diplomatic than him. Remember how much scrutiny Trump got for describing third world countries as “shitholes” in a closed meeting? Can you imagine the cataclysm that would ensue if he made the same kind of comment as Erdogan? Or if he even showed footage of the Islamic terrorist attacks on Europe to prove a point? Now don’t get me wrong: you are in no way obligated to like Trump, you can certainly criticize both him and Erdogan for different reasons. But its really sad how American journalists live on easy mode when Turkish journalists constantly have to look over their shoulder to not post anything that the regime finds objectionable.

I realize that not all Turks support Erdogan, but a significant number of them (including a former friend of mine) voted to place him into power and are fine with living under his autocratic rule. This speaks something truly depressing about the Turkish people that for all the pretense they were once the secular model that all Muslim peoples should aspire to be, if the statistic of support for Erdogan are correct, it means things must be worse than imagined.

To conclude this text with an anecdote, it seems that that not only Erdogan’s long-life dream appears to have been for naught with Assad still standing in Syria, Morsi gone, the Kurds are on the rise and Turkey’s economy being on the toilet and only being bailed out by Qatar, it seems Erdogan doesn’t have much time left on his planet and not only because of his advanced age. Wikileaks has reported that he has been diagnosed with cancer, and while he has officially denied it, his oncologist has been arrested too which is a very interesting development. As of the time of writing, the man doesn’t appear to be any worse than before so we should see how this pans out. But it should be interesting what kind of succession will be in place or if Erdogan actually planned that long enough. Its a luxury that dictators very rarely afford it for themselves.

I find it very fitting: that the actual sick old man of Europe would want to restore the previous sick old man of Europe that was the Ottoman Empire that he identified the most, the pan-Islamist one trying desperately to survive in a changing world only to live long enough to see political Islam fall flat on its face and become discredited as a viable ideology.

0 notes

Photo

In A Greek Refugee Camp: A Volunteer's Notebook

By Mai El-Mahdy

Licensed as Creative Commons Attribution 3.0.

Syrian refugees in Greece. By now there are thousands of blog posts, newspaper articles and eyewitness accounts that tell the stories of entire families drowning in the ocean, in desperate hope for a life free of warfare and poverty. I’m sure there are even more on those who eventually survived the ferocious waves, only to move into inhumane, “temporary” camps where they end up spending years. But for better or for worse, I’m not going to talk about the refugees, the lives they left behind in Syria or how they ended up in Greece. I want to talk about the current conditions and the role—or lack thereof—of those of us who try to help them, in bringing an end to this humanitarian crisis.

Recently I spent a couple of weeks at Greece’s Ritsona camp, a hub for five different humanitarian NGOs, alongside the UN operations. Ritsona is an old military base located outside Chalkida, the chief town on the island of Euboea, about an hour’s drive north of the centre of Athens. Its population is roughly two-thirds Syrian, with the remaining third made up of Kurds, Iraqis, and Afghans.

Sunken dignity

One of the harsh realities about life in the camps that is hard to fathom, let alone survive, is the absence of self-respect—dignity that has dropped so low it’s as if it was eaten up by the fierce waves before sinking to the bottom. It’s the dented sense of dignity that makes a person happy to move out of a tent into some makeshift caravan container box that becomes your “temporary” shelter for months and months. It’s the type of dignity that is all but lost when your entire livelihood is at the mercy of NGO workers who, through their authority and the decisions they make on people’s behalf, teach the refugees to accept the little they get, and be happy. Why do this, when these people are already broken? Do we volunteers always know what’s best for them? Would we allow others to make similar decisions on our behalf?

It’s not about freedom of choice; it’s not about allowing people the space to make their own decisions and mistakes. It’s about self-determination. Refugees take every single imaginable risk, relying on factors way beyond anyone’s control, only to arrive—miraculously—at a camp and submit to someone else’s decision-making, regardless of how good or bad those decisions are.

“Let’s teach English!” Everyone needs and wants to learn English, right? “Let’s buy toys for children,” overlooking the desires of parents, and the children themselves. Queuing up for food or clothes is part of the harsh reality of accepting that, due to circumstances beyond your control, you have become less valuable of a human being.

Refugees don’t want to queue for ages for food or clothes: they want to be treated as human beings, just like a black man in Apartheid South Africa, a Palestinian in the face of the Israeli occupation, or a woman anywhere in the world today. Part of the pain is acknowledging, while you stand in line, that few outside of your war zone would ever have to endure this or even entertain the thought. It is the frustration of being offered the non-choice of either being grateful that you’re in a queue with food at the end of it, or of being featured in a photo shared on social media that makes people feel sorry for you.

Perhaps we should look at the treatment of refugees as a right they have earned for themselves, not as charity that we choose to give to them. Perhaps we should focus our efforts on allowing them to fight for themselves. Perhaps it is simply about paving the way for their self-emancipation, regardless of where it leads them, and especially regardless of where it leaves us. We need to focus on educating them about their rights based on the country they are relocated, caring for their health, providing education for them and their children, etc.

Perhaps we should look at them the way we want them to look at us: with dignity and self-respect.

Are we really helping?

It’s funny how, as volunteers, we’re expected to arrive on the scene and push, along with everyone else, to get the wheels in motion. As though we’re not part of the story, but instead temporary outsiders brought in to perform a specific mission. But whether we like it or not, we are part of the narrative and influence it, significantly.

As individuals, we struggle with our egos. It’s one thing to recognize that—and in fact, very few volunteers are strong enough to do even that. Suppressing our egos, however, is a totally different story. It’s probably inevitable that volunteers find it easier to feed their egos than feed the needy. And the reward is so tempting that many forget to stop for a minute and ask themselves: are we really helping?

It’s no wonder so many volunteers pay special attention to children, who become quickly attached. But how does that help?

Volunteers can’t help but feel superior. In the camps they stand out like a sore thumb, and that’s not always unintentional. Volunteers often see themselves as providers of a valuable service, as making a great sacrifice of time and expertise. And they expect others to be gracious and remind them what great human beings they are for doing what they do.

But it’s not a service—it’s the refugees’ right. And this shouldn’t be debatable.

Once, at one of the stores where we shopped for the people of Ritsona camp with donated funds, I tried to bargain with the cashier to get more for my donated buck. The cashier, a fellow Egyptian making a living across the Mediterranean, agreed to “hook me up.” But instead of reducing the cost, she offered to write me an invoice for a higher sum. According to her, many volunteers and NGO workers accepted the fake invoices and pocketed the difference, so it was clear to her that I was new to this. And no, she did not budge on the price.

That’s only the tip of the iceberg. Some volunteers finance their travel out of the donations they receive. In spite of pleas for greater transparency, few NGOs actually publish the details of their finances. And even fewer donors ask for the details. If it’s change we’re after, this is probably a good place to start.

In my opinion, the best way to help refugees is by bypassing the NGOs altogether. It’s not difficult for us to connect directly with refugees. They’re human, just like us, just with different circumstances that suck. Treating them as patients with some disease or disability doesn’t help.

A friend of mine has a different take on this. He relates the story of a German doctor, an older gentleman, extremely professional and meticulous about his work. It’s his job to treat patients to the best of his ability given the facilities provided. From morning till night this doctor receives patients, diagnoses them, treats them. He doesn’t speak the language of the country where he works, and is very distant, almost cold. But he treats every single person he comes across, and he sets up and develops the medical facility and trains the workers so that the project can sustain itself after his departure. Many might not know him, care about him, or even remember him, though he is the one who directly helped and advanced the community. No credit. No showiness. No emotion. Just pure problem-solving.

I don’t necessarily disagree. NGOs impose strict rules on volunteers, one of which prohibits staying at the camp past 5pm. I hated this rule, so after a couple of weeks, I moved out of NGO housing and into the camp. I stayed with a refugee friend and her two daughters in their container. I would never argue that I was living their life, but I will say that I was observing it through a sharper lens.

While I agree that being distant and professional may be highly efficient and effective, I think that closeness also helps. Yes, we eventually leave; and sure, we may invest more time and effort in forming emotional bonds with the refugees than in providing tangible deliverables. And I won’t deny that I’ve learned more from the refugees about the Syrian cultural and political context than I’ve shared my own knowledge.

But by establishing close bonds we remind others—and ourselves—that they are human. And we become more human in the process.

Hospitals Don't Always Speak Your Language

The day to-day medical needs of Ritsona camp residents, of which there was an abundance, were left pretty much unattended. In emergencies, however, the Greek National Emergency Medical Services (EKAB, Ethniko Kentro Amesis Voitheias) would transport residents of the camp to and from the nearest hospital.

No one likes to go to the hospital, but when you’re a Syrian in a foreign country, it’s even worse than you imagine. Refugees are immersed in a sea of loneliness and fear of the unknown. You can see it in their eyes. And the harsh conditions of the journey to the camp leaves the majority of children, especially, with severe respiratory problems.

Many of the Greek doctors, however, didn’t even speak English nor did they have translators, and most patients could express themselves only in either Arabic or Kurdish. Often, residents would spend hours awaiting emergency care at the hospital, only to lose hope of ever understanding what they needed to do to get treatment, and leave.

At the camp my Arabic came in handy, as my job was to accompany the patients. Last May one of the NGOs at Ritsona pioneered a unique initiative dubbed “Hospital Runs”; that was the team I worked with. It’s a program organized in collaboration with the Red Cross that operates under the license of the Greek Army. They provide medical transportation, English, Greek and Arabic interpretation, and intercultural and medical assistance. The team also helps with bureaucratic procedures.

I was proud to be a member of that team. Each day we’d hop over to Chalkida or trek all the way to Athens, returning in the evening after having handled whatever problems, cases and complications had been thrown at us.

Sometimes the hospital staff made us feel unwelcome, scolding us about coming in with muddy shoes, indifferent to the fact that the camp is basically built on mud. I remember arriving at the hospital one day to find a young woman, clearly Arab and most probably from the camp, all alone, with nobody attending to her. She had clearly given up on trying to communicate or to save herself from whatever pain had piled on top of everything she had brought over to the continent. She gave me her details and the number of a loved one, so that I could communicate to them in the event she didn’t make it. Thankfully, and against the odds, she survived.

I guess I just can't fathom how borders and bodies of water can ultimately decide who's granted the opportunity to climb to the top, and who will be left to drown, and sink to the bottom.

Mai El-Mahdy is an Ireland-based Egyptian who works in tech. She was one of the millions who took part in the #Jan25 revolution, and she looks forward to being part of the next one.

26 notes

·

View notes

Link

http://ift.tt/2hZOxgO

January 5, 2017 Kabul, Afghanistan—It is Friday noon in Kabul, Afghanistan, and men dressed in traditional clothes hurry to mosques to pray in congregation. Friday prayers are usually men’s business, and during the Taliban rule in the 1990s, women were not allowed in mosques. But in one neighborhood in the city, an imam has kept the doors of his mosque open to women for 12 years now. He often preaches about women’s rights in Islam – that women are equal to men and have the right to work and study.

This is all because of a woman named Jamila Afghani and the gender-sensitivity training program she has created.

Ms. Afghani has a friendly smile that hides all that she has had to endure in life. A women’s rights activist and Islamic scholar in Afghanistan, she has battled discrimination, as well as disability, since childhood. But it was access to education and being able to read the Quran herself that made her realize Islam could be used to empower women in Afghanistan.

Today, according to Afghani, about 20 percent of Kabul’s mosques have special prayer areas for women, whereas only 15 years ago there were none. The sermons delivered by imams about the importance of education have also helped many women persuade their families to let them study. In fact, some 6,000 imams in Afghanistan have participated in Afghani’s training program.

Afghani was born in Kabul in 1974, a few years before the Soviet invasion of the country. When she was only a few months old, she contracted polio, which left one of her legs disabled. But for Afghani the disability became a blessing in disguise. Her family was conservative and did not approve of education for girls. Her sisters played outside, but Afghani was not able to; she became easily bored and spent her days crying. Finally, at the suggestion of her doctor, her father enrolled her in first grade.

“I became very happy. When I got to school, it was my whole world,” she says.

Afghani was in fifth grade when the fighting between the mujahideen and the Soviet Union became so fierce that her family left Afghanistan for Pakistan. In Peshawar, she enrolled in master’s-level classes in Islamic studies and began learning Arabic. Once there, she came to see an Islam that was not what she had been familiar with.

“When I started learning Arabic and studying by myself, I found out that Islam is totally different from what my family was saying, what my environment was teaching,” she says.

“Everything was always a discrimination in our family,” says Afghani, who observed how her brothers behaved with their wives. “They were educated women, but my brothers stopped them from continuing their education and working,” she recounts. “I thought, if [my brothers] can go outside, why not my sisters-in-law?”

Gradually, Afghani got involved with an Afghan women’s rights group in Peshawar. And over time, she formed her own organization, later named the Noor Educational and Capacity Development Organization (NECDO). She decided to take an Islamic approach, which made it possible for her to teach literacy classes for women in refugee camps. “It was not easy to enter into those communities,” she explains. “But when we used Islamic education as an entry point, we had a very good experience.”

Returning to Afghanistan

After 2001, when the Taliban were ousted from power in Afghanistan, scores of refugees started returning to the country, Afghani among them. She began setting up women’s centers where literacy was taught.

But when the project was taken to Afghani’s native Ghazni province, she ran into problems with the community – especially the imams of the mosques. She decided to invite one of the imams to her center, but he was embarrassed to meet a woman and said he wished nobody would find out. Afghani couldn’t believe his attitude: “I thought, my God, what is this?” But she chose to take a respectful approach and explained that she was educating women about Islam. “I said, ‘If you can find a single verse from the Quran or the hadith that education is bad, then I’ll stop right now and hand over the key of this center to you.’ ”

Slowly, she says, the imam became impressed with Afghani’s knowledge of Islam, and he started encouraging men to let their wives and daughters go to the center. Suddenly, the space was crowded with women hungry for education.

In 2008, Afghani was invited to a conference in Malaysia organized by the Women’s Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality (WISE), a network for Muslim women. There she learned about a Filipina woman who was writing Friday sermons for imams about women’s rights. This gave Afghani the idea about gender-sensitivity training for imams. With the support of WISE and female Muslim scholars, “we developed a manual for the training,” she says.

A clever approach

Afghani knew the task ahead was not going to be easy. Initially, imams were shown the manual without them knowing it would be used for their own training. Afghani and her colleagues told the imams they wanted input on what they had developed. This is how the discussions began, and suddenly the training was in full swing. “Sometimes women are very clever. More than men,” Afghani laughs.

Some of the imams were immediately receptive to Afghani’s ideas. But with others, some issues proved very difficult. “Women’s political participation was the hardest thing,” she says. “Even ... now, some of the imams are not on the same page as [us].”

Of the 6,000 imams who have been trained by NECDO, one is Mohammed Ehsan Saikal, the imam in Kabul who has kept his mosque open to women for 12 years. He has been working with Afghani during this time and often preaches about the importance of education for girls. “I have three daughters, and all of them are highly educated and go to work,” he says. “The best thing I have received from this organization is enlightenment and awareness.”