#i used to be a gig economy driver at a company that was sued for paying less than minimum wage after expenses

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

every time doordash discourse re-emerges it gets lazier and more stupid and its proponents more self-infantilizing. the incredible excuses people come up with to defend the luxury of having their treats delivered at a tremendous premium, almost none of which ends up in the hands of the heavily exploited worker

#i've seen people call themselves disabled then reveal their disability is adhd#i've seen people ask why gig economy drivers are any different from delivery drivers employed by the restaurant often with a car provided#i've seen people argue that um actually having food dropped off at your doorstep by a rent-a-slave is communism realized#i used to be a gig economy driver at a company that was sued for paying less than minimum wage after expenses#successfully sued in a class action suit btw lol

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Proposition 22 Passes, but Uber and Lyft Are Only Delaying the Inevitable

On Tuesday night, Californians voted to pass Proposition 22, a ballot measure supported by app-based gig companies that exempts them from reclassifying their workers as employees.

Companies including Uber, Lyft, Instacart, Postmates, and more, spent big to convince voters to approve the measure. The company-funded Yes on Proposition 22 campaign spent over $200 million (including millions in donations to the California GOP), deployed a record number of lobbyists, and spread waves of misleading political mailers. At the same time, Uber’s and Lyft’s chief executives undertook a media tour featuring threats to exit the state and repeatedly attempted to exempt themselves in California’s courts. The campaign bought digital, television, radio, and billboard ads, and also sponsored academic research Meanwhile, delivery drivers were forced to use Yes on Proposition 22-branded packaging while the apps themselves told users to vote yes.

On the other side of the issue was a grassroots campaign run by driver advocacy groups and organized labor, which spent just over $20 million.

“We’re disappointed in tonight’s outcome, especially because this campaign’s success is based on lies and fear-mongering. Companies shouldn’t be able to buy elections,” Gig Workers Rising, a California-based driver advocacy group said in a press release early Wednesday morning. “But we’re still dedicated to our cause and ready to continue our fight. Gig work is real work, and gigi workers deserve fair and transparent pay, along with proper labor protections.”

As news of the results broke, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi took to Twitter to show his excitement and shared a tweet from early Uber investor Jason Calacanis calling Assemblywoman Lorena S Gonzalez, the author of AB5, a “grifter” who “failed to hand gig workers over to big-money unions”.

After some time, Khosrowshahi reversed the retweet and instead emailed drivers a more subdued message celebrating that the “future of independent work is more secure because so many drivers like you spoke up and made your voice heard—and voters across the state listened.”

This is undoubtedly a victory for capital over labor, and one that will likely allow the unprofitable gig economy to continue limping along at the expense of workers. It does not, however, change the reality that the “gig” business model is doomed in the long-term.

For years, gig companies have misclassified employees as independent contractors—a legal distinction that has allowed unprofitable enterprises to avoid expensive labor costs such as a minimum wage, health insurance, and safe working conditions, among other benefits of employment. Proposition 22 was cooked up to undo Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), a California law that codified an “ABC test” to determine if a worker was independently contracted or employed by a company and which went into effect in January.

After AB5 went into effect, attorneys for some of California’s largest cities, along with the state’s attorney general, then filed suits demanding an end to app-based gig company worker misclassification. Uber and Lyft have waged the main legal battle, but lost the case and every appeal since, making Proposition 22 a make-or-break measure.

“Prop 22 means I get no workers’ compensation, no disability, no sick pay, it would be touch and go for me,” Mekela Edwards, an Oakland-based Uber driver who hasn’t worked since March because COVID-19 poses a high health risk to her. “I have to ask how long my unemployment will last, how long I’ll have before I’m forced to go back out there and work. I don’t want to imagine it, I can’t imagine being forced to choose between my health and making a living.”

Hundreds of thousands of people work for the gig companies behind Proposition 22 and many have been devastated by the COVID-19 recession. Still, this has not stopped the gig companies from threatening to take drastic measures if they’re not allowed to have their way. Over the past few months, Uber and Lyft in particular have threatened to radically downsize where service is offered, fire most of their drivers, radically restructure into a franchise model, or leave the state entirely, if Proposition 22 fails.

California voting Yes on Prop 22—which includes fine print that any changes to it must be passed with a seven-eighths majority in the state’s legislature—is a huge setback for labor. It will trap hundreds of thousands of workers under a permanent misclassification scheme that rewards a racist business model that disproportionately hurts Black and brown workers. Despite all this, Proposition 22 is not the final say on this matter in the U.S. or internationally.

AB5 clones are being considered in New York and New Jersey, while Massachusetts’ Attorney General has already sued Uber and Lyft to reclassify drivers in the state. Despite objections from Uber’s and Lyft’s impressive lobbying operations, the PRO Act—which would grant gig workers the right to collectively bargain, as part of a massive overhaul of labor law—has passed in the House.

“This is really a story about the kind of cities we are building,” Katie Wells, a researcher at Georgetown University told Motherboard. “The kind of cities—the kind of world we’ve built—it has allowed these entities to come in and build up a workforce through an extractive and predatory system. Regulators have to keep that in mind.”

Outside of the U.S., the global 2019 strike on the day of Uber’s public offering has been followed by successive waves. Over the summer, thousands of delivery workers organized militant strikes and protests in Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and Ecuador targeting Uber Eats and other exploitative food delivery apps. These have been joined by even more strikes and protests in Nigeria, France, and India. At the same time, Uber is losing legal challenges in France, Britain, Canada, Italy, where high courts have either outright ruled Uber drivers are employees or have opened the door to lawsuits reclassifying them as such.

Governments across the world are also beginning to push Uber to pay billions in taxes that it has evaded over the past decade. In Britain, Uber will have to pay £1.5 billion ($1.9 billion) in unpaid value-added taxes it avoided by exploiting a legal loophole. In the U.S., Uber has dodged billions in taxes and wage claims through misclassification: in New Jersey it owes over $650 million in taxes, while in California drivers have filed $1.3 billion in wage claims against Uber and Lyft.

Since Uber’s only hope for survival lies in misclassifying workers and labor law, though, it won’t give up the billions to be made both domestically and globally (even if at a loss) without a fight.

“There’s a lesson here for workers of all sectors, beyond classification: companies are willing to spend massive amounts of money to take away their rights,” said Jerome Gage, a Lyft driver and organizer with Mobile Workers Alliance. “It’s incredibly important for workers to organize to protect themselves, to protect upward mobility, a minimum wage, sick leave, healthcare—to roll back a century of basic protections that try and keep Americans out of poverty.”

Proposition 22’s victory, however, can’t obscure the fact that these companies are doomed. Even with a wage guarantee that effectively pays $5.64 an hour, the companies are no closer to sustainably achieving profitability than they were yesterday. Overcrowded markets for ride-hailing and food delivery, along with vicious price wars and poor unit economics meant there was never any real hope of achieving a monopoly, erecting barriers to market entry, and raising prices to levels that, for many of these companies, would yield their first ever profits.

There’s good news for investors, however, who will finally begin to see returns on investments that have long been underwater thanks to massively inflated valuations that have tumbled in public markets. Indeed, share prices for Uber and Lyft soared in premarket trading on Wednesday morning.

For workers, though, things will be bad. It is hard to imagine how hundreds of thousands of workers earning wages just under half of the minimum wage will be able to feed themselves, maintain housing, afford medical care, or otherwise make ends meet, especially under the boot of a pandemic and with no hope of government aid until next year.

Localities, cities, states, and countries will have to begin cooperating if they’re to have any hope of weathering the storm. They’ll need to start being aggressive, experimenting with ways they can outright take over the platforms or prohibit companies from providing the service to begin with—all while figuring out ways to expand mass transit so that not only they’re not only meeting the needs of people who need transportation, both those who worked for app-based ride-hail companies previously.

For the sake of maintaining an illusion that they’ll one day be profitable, gig companies have waged war in California at great expense to their workers, the public, and employees in other industries whose employers may grow emboldened this moment. The fight is far from over, and there is hope for labor in the continuing coordination of driver advocates, regulators, and legislators around the world, but it will get messy as likely to harken a period of unprecedented social unrest among increasingly immiserated gig workers.

“Beyond California, we need to strike early and strike quickly to ensure swift defeat to this idea that you can change the basic nature of employment and deny benefits to your employees,” Gage told Motherboard. “I ask people not involved to try and understand the labor movement in your area. Reach out to unions and ask how you can help volunteers…Get involved with and spread the world—[money] can buy misinformation and it can deceive, but it can’t beat the solidarity between two workers or between human beings.”

Read More

https://www.covid19snews.com/2020/11/04/proposition-22-passes-but-uber-and-lyft-are-only-delaying-the-inevitable/

0 notes

Text

Independent Contractor Or Employee? Uber & Lyft, Inc. Try To Bypass The Courts

By Marshall Comia, University Of California Davis Class of 2021

October 12, 2020

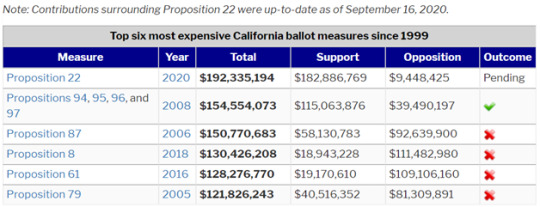

In the upcoming general elections, California voters will have to decide whether or not to pass what has become the most expensive ballot measure in California history, Proposition 22.[i] This proposition would alter the criteria that determines what classifies an employee from an independent contractor.[ii]More specifically, this proposition will determine whether or not “app-based rideshare and delivery companies[, such as Uber, Lyft, Instacart, and Doordash,] can hire drivers as independent contractors.”[iii]Distinguishing between these two worker classifications are important for a company because unlike employees, independent contractors don’t receive standard benefits and protections from their company; these include, among others, health care benefits, unemployment insurance, and workers’ compensation. By taking this expensive legal fight to the ballot box, these app-based companies are trying to bypass the courts.

In 2019, Assembly Bill 5 (A.B. 5) was passed through the California legislature and signed into law. This bill effectively mandated that app-based rideshare and delivery companies classify their workersas employees instead of independent contractors, aswell as treat these workers appropriate to their new classification. A.B. 5 does this by codifying the case of Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court of Los Angeles (2018) (Dynamex). In the Dynamex decision, the “ABC” test, which is “utilized in other [California] jurisdictions in a variety of contexts to distinguish employees from independent contractors,”[iv]was used again to make the worker distinction. Under the ABC test, a worker is considered an independent contractor and not an employee if “the hiring entity establishes:

“(A) that the worker is free from the control and direction of the hirer in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of such work and in fact;

“(B) that the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

“(C) that the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed for the hiring entity.”[v]

If any one of the three criteria cannot be adequately established by the hiring entity, then the hiring entity can’t classify the worker as an independent contractor; they have to classify the worker as an employee. In a case where a court rules that the ABC test can’t be applied, A.B. 5 says that the test from the case S. G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Department of Industrial Relations (1989)(Borello) that determines employee or independent contractor status should instead be used. The Borello test weighs a myriad of interrelated factors that can be weighed differently to principally decide “whether the person to whom service is rendered has the right to control the manner and means of accomplishing the result desired.”[vi]Despite the passage of A.B. 5, Uber and Lyft Inc. aren’t following it.

In May 2020, Uber and Lyft Inc. were sued by the Attorney General of California for continuing to violate A.B. 5 after it took effect January 1, 2020, by “misclassify[ying] their ride-hailing drivers as independent contractors rather than employees” in the case People v. Uber et al (Uber et al.).[vii] The People also tried a motion “for a preliminary injunction enjoining Defendants from classifying their drivers as independent contractors;”[viii] meaning that the court would order Uber and Lyft to immediately comply with A.B. 5 unless another court says otherwise. In this California Superior Court decision, Judge Ethan Schulman ruled that Uber and Lyft Inc. misclassified their workers as independent contractors and should be classifying their workers as employees because defendants Uber and Lyft, Inc. fail the B prong of the ABC test established in Dynamax (“that the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business.”).[ix]Uber tried to argue that their companyis a technology company rather than a transportation company, that “operate[s] as ‘matchmakers’ to facilitate transactions between drivers and passengers”[x] and their actual employees are the tech workers who do the “engineering, product development, marketing and operations ‘in order to improve the properties of the app.’”[xi]Therefore, Uber tried to make the case that Uber drivers are “outside the usual course” of the work that Uber employees do. Uber’s shot down argument was seen by the courts as a “classic example of circular reasoning: because it regards itself as a technology company and considers only tech workers to be its ‘employees,’ anybody else is outside the ordinary course of its business, and therefore is not an employee.”[xii] Uber has made this argument beforein the case O’Connor v. Uber Technologies, Inc. (2015). In this case, “Judge Edward Chen of the U.S District Court for the Northern District of California found this argument ‘flawed in numerous respects’…‘fundamentally, it is obvious drivers perform a service for Uber because Uber simply would not be a viable business without its drivers.’”[xiii]As opined, the decision in Uber et al. to classify Uber and Lyft, Inc. drivers as employees has been seen in many other court conclusions, such as Cunningham v. Lyft, Inc. (2020), Namisnak v. Uber (2020), and Crawford v. Uber Technologies, Inc. (2018).[xiv]

The defendants of Uber et al. also made two other main arguments to defend their evasion from complying with A.B. 5. Defendants first argued that A.B. 5 doesn’t apply to them at all “because they are not ‘hiring entities’ within the meaning of the legislation.”[xv] The court noted that in a previous case, Uber argued that “AB 5 targets gig economy companies and workers and treats them differently from similarly situated group,”[xvi] yet in Uber et al., Uber was trying to argue that the same piece of legislation that unfairly targeted them didn’t apply to them at all. The court decided that they couldn’t “take seriously such contradictory positions”[xvii] and ruled the defendants as subject to A.B. 5.

The second main argument that defendants made was that if they reclassified their drivers as employees in compliance with A.B. 5, they would suffer “two categories of harm: (1) the costs and other harms associated with the restructuring of Defendants’ businesses in California; and (2) the harms to Defendants’ drivers, including the risk that some may [be] unable to continue earning income if Defendants do not offer them continued work as employees, and the risk that their reclassification as employees jeopardize their eligibility for emergency federal benefits available to them as self-employed workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.”[xviii] In response to the first category of harm, the court acknowledged that the compliance to A.B. 5 will be costly because defendants “will have to change the nature of their business[es] in significant ways.”[xix] But, the court points out that defendants’ argument “at root, is fundamentally one about the financial costs of compliance.”[xx]

In response to the second category of harm, the court opined that if compliance to the People’s demands of A.B. 5 were far-reaching,

“they have only been exacerbated by Defendants’ prolonged and brazen refusal to comply with California law. Defendants may not evade legislative mandates merely because their businesses are so large that they affect the lives of many thousands of people.”[xxi]

The court points out that since Defendants’ ridership is currently lower than it’s ever been, now “may be the best time (or the least worst time) for Defendants to change their business practices to conform to California law without causing widespread adverse effects on their drivers.”[xxii]Overall, the Defendants are trying to drag out litigation until after the November 2020 election, where Uber and Lyft can become exempt from A.B. 5’s requirements through the passage of Proposition 22. Despite the motions that Defendants have made attempting “to delay or avoid a determination whether, as the People allege, they are engaged in an ongoing and widespread violation of A.B. 5…Defendants are not entitled to an indefinite postponement of their day of reckoning. Their threshold motions are groundless.”[xxiii] The court ordered that defendants are “restrained from classifying their Drivers as independent contractors.”[xxiv]

[xxv]

The contributors supporting Proposition 22 have raised over $184 million, with Lyft, Inc. and Uber as the top two contributors.[xxvi] The contributors opposing Proposition 22 have only raised around $7.5 million. In a Berkeley IGS Poll of likely voters, 39% would vote yes to Proposition 22, 36% would vote no, and 25% are undecided.[xxvii] As shown by the Proposition’s tight poll numbers, the fight for whether app-based rideshare and delivery companies will classify their workers as independent contractors or employees is going to be a close one.

________________________________________________________________

[i]“What Were the Most Expensive Ballot Measures in California.” Ballotpedia. Lucy Burns Institute. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/What_were_the_most_expensive_ballot_measures_in_California.

[ii]“Qualified Statewide Ballot Measures.” Qualified Statewide Ballot Measures :: California Secretary of State. California Secretary of State. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/ballot-measures/qualified-ballot-measures.

[iii]“Proposition 22 [Ballot].” Legislative Analyst's Office. Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC). Accessed September 29, 2020. https://lao.ca.gov/BallotAnalysis/Proposition?number=22&year=2020.

[iv]Dynamex Operations W. v. Superior Court and Charles Lee, Real Party in Interest,4 Cal.5th 903, 416 P.3d 1, 232 Cal.Rptr.3d 1 (2018).https://boehm-associates.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Dynamex-Operations-West_-Inc.-v.-Superior-Court_-4-Cal.pdf

[v]Id.

[vi]S. G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Department of Industrial Relations 48 Cal.3d 341 (1989).

[vii]People of the State of California v. Uber Technologies, Inc., A Delaware Corporation et al. https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/7032764/Judge-Ethan-Schulman-Order-on-Lyft-and-Uber.pdf.

[viii]Id at 2.

[ix]Dynamax, 4 Cal.5th at 908

[x]People of the State of California v. Uber Technologies, Inc., A Delaware Corporation et al.https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/7032764/Judge-Ethan-Schulman-Order-on-Lyft-and-Uber.pdf

[xi]Id.

[xii]Id.

[xiii]Id.

[xiv]Id.

[xv]Id.

[xvi]Lydia Olson et al v. State of California et al, 2:19-cv-10956, No. 52 (C.D.Cal. Feb. 10, 2020) (available at https://www.docketalarm.com/cases/California_Central_District_Court/2--19-cv-10956/Lydia_Olson_et_al_v._State_of_California_et_al/52/)

[xvii]Id.

[xviii]Id.

[xix]Id.

[xx]Id.

[xxi]Id.

[xxii]Id.

[xxiii]Id.

[xxiv]Id.

[xxv]“What Were the Most Expensive Ballot Measures in California.” Ballotpedia. Lucy Burns Institute. Accessed September 29, 2020. https://ballotpedia.org/What_were_the_most_expensive_ballot_measures_in_California.

[xxvi]“November 2020 General Election.” California Fair Political Practices Commission. Accessed September 29, 2020. http://www.fppc.ca.gov/transparency/top-contributors/nov-20-gen.html.

[xxvii]DiCamillo, M. (2020). Tabulations from a Mid-September 2020 Survey of California Likely Voters about Four of the Propositions on the November 2020 Statewide Election Ballot. UC Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1p22n9ws.

0 notes

Text

DoorDash and Uber Eats aren’t collecting sales tax on delivery fees in some states. That could be a problem.

Discrepancies between the sales tax practices of companies like DoorDash, as well as its competitors like Uber Eats, Postmates, and Grubhub are raising questions | Getty

It could be the latest business practice in the gig economy to raise regulatory questions.

The food delivery company Grubhub said it has collected hundreds of millions in taxes for delivery and service fees in dozens of states since at least 2011. But Recode has found that in some of those same states, Grubhub’s top rivals in the delivery space, including DoorDash, Postmates, and Uber Eats, don’t appear to be collecting a cent. This discrepancy puts those rivals in a precarious position if regulators take notice and object.

Several tax experts Recode interviewed said food delivery app companies’ tax practices could raise legal concerns. The sales taxes in question are on fees that can amount to as much as a third of the total price of food orders — or at least $120 million per year of taxable dollars on the sales of major food delivery companies in California and New York alone, based on Recode’s calculations on an estimated market size from research firm Forrester. If you account for all of the US, that could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

The experts told Recode these tax practices could be a liability not just for the food delivery apps but also for the restaurants whose food they deliver. Both the apps and the restaurants could later be on the hook for paying taxes that apps aren’t currently collecting. It’s another example of how existing laws haven’t yet adapted to the gig economy — and in the meantime, these tech companies are taking advantage of the loopholes.

“I would feel very uncomfortable if I were tax counsel for one of those companies if those taxes weren’t being collected,” said Hayes Holderness, assistant professor at the University of Richmond School of Law and a state tax policy expert. Holderness called it an “aggressive” and “risky” decision for companies not to charge sales taxes on delivery — but a “not necessarily unreasonable” stance, and one that could be debated in court. For companies in the competitive food delivery market, the immediate business benefit of keeping sales taxes lower could also outweigh the legal risks, he said.

Gig economy companies have historically loosely interpreted the law — or in some cases skirted it entirely — to benefit their business models, and regulators are increasingly examining their behavior.

The Washington, DC, attorney general announced earlier this week he’s suing DoorDash, arguing that the company misled customers and pocketed workers’ tips. Earlier this year, politicians raised concerns about wage theft when Instacart, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and several other companies were found to be using workers’ tips to subsidize their own costs (the companies all eventually revised their policies — with DoorDash being the slowest to do so — and many workers continue to report low pay). In September, Uber made a baffling argument that its drivers aren’t core to its business as part of its rationale for why a new labor law targeted at gig economy apps didn’t actually apply to the company. And ride-hail companies have similarly been accused of not doing enough to prevent and investigate sexual assaults that occur during rides.

In every case, gig economy companies have argued that they are digital marketplaces matching sellers and buyers and are therefore not financially or legally responsible for things that happen on their platforms.

When it comes to sales tax, companies have an obvious business incentive to avoid charging it: keep prices low, keep customers happy, and keep sales up. And in the food delivery space, which is an increasingly competitive industry with tight margins, that’s an acute pressure.

“Right now there’s an arms race for customer acquisition,” said Sucharita Kodali, a principal analyst at Forrester who specializes in e-commerce. “As venture capital startups, the more growth they can exhibit, that’s still the signal of success, and any lever they can use to help showcase those metrics helps.”

In the past year, DoorDash has emerged as the unexpected market leader and fastest-growing food delivery app in the US, according to research firm Edison Trends, unseating market incumbent Grubhub. The company has aggressively expanded its business, putting pressure on an already crowded market.

If tax laws were more clear, food delivery companies would probably just absorb the cost of charging sales taxes on delivery fees and “move on,” Kodali told Recode. But, Kodali said, in “an age of ambiguity, if it helps them to showcase a better result then why not?”

But it also poses a risk. If states or cities find companies liable for taxes later, they could sue for years of back taxes, several tax experts told Recode. That’s what happened to travel website Expedia, which several cities accused of avoiding as much as $847 million in taxes on room fees. The company has long been embroiled in legal battles over these cases. More recently, the state of New Jersey recently sued Uber for over $650 million in unemployment and disability insurance taxes for allegedly misclassifying its workforce as independent contractors instead of employees.

Laws haven’t caught up with the gig economy

The tax codes governing food delivery apps like Grubhub, DoorDash, and Postmates vary significantly state by state, and they are changing as local governments grapple with how to adapt old laws to the new gig economy.

Generally, some laws in states like California and New York have provisions that could call for sales taxes on delivery and service fees to be collected, according to Scott Groberski, a managing director in state and local tax groups at accounting and tax firm Grant Thornton. Still, it’s very much a gray area and would vary based on the specifics of the contracts between restaurants and food delivery providers.

“With new technology, it’s extremely complicated determining what’s taxable and what’s not — I think this is something that continues to evolve even as we speak,” Groberski told Recode.

In California, for example, it depends if the company contracts with restaurants to “provide a delivery service only” or if it acts as a “retailer” of the food, according to Casey Wells at the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

Whether or not a food delivery app company is a retailer depends on the contracts it has with restaurants, Wells said, as well as if the app is marking up the price the restaurant normally charges for the food.

Wells declined to comment on whether or not the law would classify specific companies like DoorDash or Grubhub as retailers or not.

Some tax experts said it comes down to whether these companies are charging the restaurants they work with or only charging consumers. Grubhub, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Postmates all regularly partner with restaurants and charge them commission fees.

“I have a real doubt that Grubhub is overtaxing — the default rule should be that it’s taxable, that is the safer position,” said Holderness.

“In some cases, it may not be a question of tax avoidance or uncertainty so much as legitimate uncertainty about what the rules are,” said Steve Rosenthal, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Policies vary state to state, and the rules around taxing delivery fees are myriad and often outdated.

When asked about concerns tax experts raised about Uber’s sales and delivery tax policies, a spokesperson for Uber responded with the following statement:

“We collect sales tax on delivery fees where required, with particular attention to recently enacted marketplace facilitator laws. Although California has enacted similar legislation, there is an exception for delivery network companies. Accordingly, we do not believe it is appropriate for Uber Eats to collect sales tax on delivery fees from our users in California at this time. We are deeply committed to compliance, which includes ongoing assessment of developments in local legislation and state-issued guidance.”

DoorDash (which also owns Caviar) declined to comment.

In a statement to Recode, Postmates said it is in compliance with all regulations and tax laws in jurisdictions where it operates, and that it is “[w]orking with lawmakers across markets, both to ensure our operations remain consistent with evolving state-by-state guidance on the tax code, and to balance the unique nature of on-demand products with the goal of ensuring taxable revenues are always collected by the state.”

Grubhub, meanwhile, maintains that it’s in the right for collecting these sales taxes and denied that the food delivery app business models exempt companies from these collections.

“We have been audited by multiple states, multiple times, and in every case we were required to collect and remit sales tax on delivery fees,” said Grubhub’s CEO Matt Maloney.

The threat of regulation

In recent years, local lawmakers have increasingly scrutinized the tech industry. For example, more states are now charging sales tax on products that are purchased online. That’s because of a June 2018 Supreme Court Ruling, South Dakota v. Wayfair, which gave states the rights to demand more tax revenue from online companies that sell goods in their state, even if those companies don’t have a physical location in the area.

California politicians told Recode that they’re also thinking about how the gig economy collects taxes.

“I’m concerned about what appears to be a pattern of activity of these gig companies to not even find out what they should be doing by law,” said California Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, who authored the landmark labor legislation AB 5 that legally pressures companies like Uber and Lyft to reclassify contractors as employees. “It’s unfair competition. If you have a Dominos, for example, that is abiding by the rules, they’re taking the appropriate sales tax out, they’re not going to be able to compete with an app that’s doing all those things.” Dominos is one of the only major pizza chains that does its own delivery, independent of food delivery apps.

If there’s a lesson to be learned by food delivery startups from tech successes of the past, it’s that creatively interpreting outdated regulations can help them get ahead. Amazon largely skipped out on collecting sales tax for third-party seller products until a few years ago when it was facing state regulations to do so — but by then it was already the top online retailer. Uber ignored licensing rules in many states but became the leading ride-hail company in the meantime. And Airbnb delayed its obligation to collect taxes and enforce zoning rules by suing several cities where it operated.

In all those fights, regulators were slow to keep up with tech companies, which took advantage of that to quickly become market leaders, meaning they could afford costly legal battles. But in an era when tech is facing a reckoning with the public and increased political scrutiny, that might change, and regulators may start applying stricter rules to companies like DoorDash and Postmates.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2D4dPHQ

0 notes

Text

DoorDash and Uber Eats aren’t collecting sales tax on delivery fees in some states. That could be a problem.

Discrepancies between the sales tax practices of companies like DoorDash, as well as its competitors like Uber Eats, Postmates, and Grubhub are raising questions | Getty

It could be the latest business practice in the gig economy to raise regulatory questions.

The food delivery company Grubhub said it has collected hundreds of millions in taxes for delivery and service fees in dozens of states since at least 2011. But Recode has found that in some of those same states, Grubhub’s top rivals in the delivery space, including DoorDash, Postmates, and Uber Eats, don’t appear to be collecting a cent. This discrepancy puts those rivals in a precarious position if regulators take notice and object.

Several tax experts Recode interviewed said food delivery app companies’ tax practices could raise legal concerns. The sales taxes in question are on fees that can amount to as much as a third of the total price of food orders — or at least $120 million per year of taxable dollars on the sales of major food delivery companies in California and New York alone, based on Recode’s calculations on an estimated market size from research firm Forrester. If you account for all of the US, that could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

The experts told Recode these tax practices could be a liability not just for the food delivery apps but also for the restaurants whose food they deliver. Both the apps and the restaurants could later be on the hook for paying taxes that apps aren’t currently collecting. It’s another example of how existing laws haven’t yet adapted to the gig economy — and in the meantime, these tech companies are taking advantage of the loopholes.

“I would feel very uncomfortable if I were tax counsel for one of those companies if those taxes weren’t being collected,” said Hayes Holderness, assistant professor at the University of Richmond School of Law and a state tax policy expert. Holderness called it an “aggressive” and “risky” decision for companies not to charge sales taxes on delivery — but a “not necessarily unreasonable” stance, and one that could be debated in court. For companies in the competitive food delivery market, the immediate business benefit of keeping sales taxes lower could also outweigh the legal risks, he said.

Gig economy companies have historically loosely interpreted the law — or in some cases skirted it entirely — to benefit their business models, and regulators are increasingly examining their behavior.

The Washington, DC, attorney general announced earlier this week he’s suing DoorDash, arguing that the company misled customers and pocketed workers’ tips. Earlier this year, politicians raised concerns about wage theft when Instacart, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and several other companies were found to be using workers’ tips to subsidize their own costs (the companies all eventually revised their policies — with DoorDash being the slowest to do so — and many workers continue to report low pay). In September, Uber made a baffling argument that its drivers aren’t core to its business as part of its rationale for why a new labor law targeted at gig economy apps didn’t actually apply to the company. And ride-hail companies have similarly been accused of not doing enough to prevent and investigate sexual assaults that occur during rides.

In every case, gig economy companies have argued that they are digital marketplaces matching sellers and buyers and are therefore not financially or legally responsible for things that happen on their platforms.

When it comes to sales tax, companies have an obvious business incentive to avoid charging it: keep prices low, keep customers happy, and keep sales up. And in the food delivery space, which is an increasingly competitive industry with tight margins, that’s an acute pressure.

“Right now there’s an arms race for customer acquisition,” said Sucharita Kodali, a principal analyst at Forrester who specializes in e-commerce. “As venture capital startups, the more growth they can exhibit, that’s still the signal of success, and any lever they can use to help showcase those metrics helps.”

In the past year, DoorDash has emerged as the unexpected market leader and fastest-growing food delivery app in the US, according to research firm Edison Trends, unseating market incumbent Grubhub. The company has aggressively expanded its business, putting pressure on an already crowded market.

If tax laws were more clear, food delivery companies would probably just absorb the cost of charging sales taxes on delivery fees and “move on,” Kodali told Recode. But, Kodali said, in “an age of ambiguity, if it helps them to showcase a better result then why not?”

But it also poses a risk. If states or cities find companies liable for taxes later, they could sue for years of back taxes, several tax experts told Recode. That’s what happened to travel website Expedia, which several cities accused of avoiding as much as $847 million in taxes on room fees. The company has long been embroiled in legal battles over these cases. More recently, the state of New Jersey recently sued Uber for over $650 million in unemployment and disability insurance taxes for allegedly misclassifying its workforce as independent contractors instead of employees.

Laws haven’t caught up with the gig economy

The tax codes governing food delivery apps like Grubhub, DoorDash, and Postmates vary significantly state by state, and they are changing as local governments grapple with how to adapt old laws to the new gig economy.

Generally, some laws in states like California and New York have provisions that could call for sales taxes on delivery and service fees to be collected, according to Scott Groberski, a managing director in state and local tax groups at accounting and tax firm Grant Thornton. Still, it’s very much a gray area and would vary based on the specifics of the contracts between restaurants and food delivery providers.

“With new technology, it’s extremely complicated determining what’s taxable and what’s not — I think this is something that continues to evolve even as we speak,” Groberski told Recode.

In California, for example, it depends if the company contracts with restaurants to “provide a delivery service only” or if it acts as a “retailer” of the food, according to Casey Wells at the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

Whether or not a food delivery app company is a retailer depends on the contracts it has with restaurants, Wells said, as well as if the app is marking up the price the restaurant normally charges for the food.

Wells declined to comment on whether or not the law would classify specific companies like DoorDash or Grubhub as retailers or not.

Some tax experts said it comes down to whether these companies are charging the restaurants they work with or only charging consumers. Grubhub, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Postmates all regularly partner with restaurants and charge them commission fees.

“I have a real doubt that Grubhub is overtaxing — the default rule should be that it’s taxable, that is the safer position,” said Holderness.

“In some cases, it may not be a question of tax avoidance or uncertainty so much as legitimate uncertainty about what the rules are,” said Steve Rosenthal, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Policies vary state to state, and the rules around taxing delivery fees are myriad and often outdated.

When asked about concerns tax experts raised about Uber’s sales and delivery tax policies, a spokesperson for Uber responded with the following statement:

“We collect sales tax on delivery fees where required, with particular attention to recently enacted marketplace facilitator laws. Although California has enacted similar legislation, there is an exception for delivery network companies. Accordingly, we do not believe it is appropriate for Uber Eats to collect sales tax on delivery fees from our users in California at this time. We are deeply committed to compliance, which includes ongoing assessment of developments in local legislation and state-issued guidance.”

DoorDash (which also owns Caviar) declined to comment.

In a statement to Recode, Postmates said it is in compliance with all regulations and tax laws in jurisdictions where it operates, and that it is “[w]orking with lawmakers across markets, both to ensure our operations remain consistent with evolving state-by-state guidance on the tax code, and to balance the unique nature of on-demand products with the goal of ensuring taxable revenues are always collected by the state.”

Grubhub, meanwhile, maintains that it’s in the right for collecting these sales taxes and denied that the food delivery app business models exempt companies from these collections.

“We have been audited by multiple states, multiple times, and in every case we were required to collect and remit sales tax on delivery fees,” said Grubhub’s CEO Matt Maloney.

The threat of regulation

In recent years, local lawmakers have increasingly scrutinized the tech industry. For example, more states are now charging sales tax on products that are purchased online. That’s because of a June 2018 Supreme Court Ruling, South Dakota v. Wayfair, which gave states the rights to demand more tax revenue from online companies that sell goods in their state, even if those companies don’t have a physical location in the area.

California politicians told Recode that they’re also thinking about how the gig economy collects taxes.

“I’m concerned about what appears to be a pattern of activity of these gig companies to not even find out what they should be doing by law,” said California Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, who authored the landmark labor legislation AB 5 that legally pressures companies like Uber and Lyft to reclassify contractors as employees. “It’s unfair competition. If you have a Dominos, for example, that is abiding by the rules, they’re taking the appropriate sales tax out, they’re not going to be able to compete with an app that’s doing all those things.” Dominos is one of the only major pizza chains that does its own delivery, independent of food delivery apps.

If there’s a lesson to be learned by food delivery startups from tech successes of the past, it’s that creatively interpreting outdated regulations can help them get ahead. Amazon largely skipped out on collecting sales tax for third-party seller products until a few years ago when it was facing state regulations to do so — but by then it was already the top online retailer. Uber ignored licensing rules in many states but became the leading ride-hail company in the meantime. And Airbnb delayed its obligation to collect taxes and enforce zoning rules by suing several cities where it operated.

In all those fights, regulators were slow to keep up with tech companies, which took advantage of that to quickly become market leaders, meaning they could afford costly legal battles. But in an era when tech is facing a reckoning with the public and increased political scrutiny, that might change, and regulators may start applying stricter rules to companies like DoorDash and Postmates.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2D4dPHQ

0 notes

Text

DoorDash and Uber Eats aren’t collecting sales tax on delivery fees in some states. That could be a problem.

Discrepancies between the sales tax practices of companies like DoorDash, as well as its competitors like Uber Eats, Postmates, and Grubhub are raising questions | Getty

It could be the latest business practice in the gig economy to raise regulatory questions.

The food delivery company Grubhub said it has collected hundreds of millions in taxes for delivery and service fees in dozens of states since at least 2011. But Recode has found that in some of those same states, Grubhub’s top rivals in the delivery space, including DoorDash, Postmates, and Uber Eats, don’t appear to be collecting a cent. This discrepancy puts those rivals in a precarious position if regulators take notice and object.

Several tax experts Recode interviewed said food delivery app companies’ tax practices could raise legal concerns. The sales taxes in question are on fees that can amount to as much as a third of the total price of food orders — or at least $120 million per year of taxable dollars on the sales of major food delivery companies in California and New York alone, based on Recode’s calculations on an estimated market size from research firm Forrester. If you account for all of the US, that could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

The experts told Recode these tax practices could be a liability not just for the food delivery apps but also for the restaurants whose food they deliver. Both the apps and the restaurants could later be on the hook for paying taxes that apps aren’t currently collecting. It’s another example of how existing laws haven’t yet adapted to the gig economy — and in the meantime, these tech companies are taking advantage of the loopholes.

“I would feel very uncomfortable if I were tax counsel for one of those companies if those taxes weren’t being collected,” said Hayes Holderness, assistant professor at the University of Richmond School of Law and a state tax policy expert. Holderness called it an “aggressive” and “risky” decision for companies not to charge sales taxes on delivery — but a “not necessarily unreasonable” stance, and one that could be debated in court. For companies in the competitive food delivery market, the immediate business benefit of keeping sales taxes lower could also outweigh the legal risks, he said.

Gig economy companies have historically loosely interpreted the law — or in some cases skirted it entirely — to benefit their business models, and regulators are increasingly examining their behavior.

The Washington, DC, attorney general announced earlier this week he’s suing DoorDash, arguing that the company misled customers and pocketed workers’ tips. Earlier this year, politicians raised concerns about wage theft when Instacart, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and several other companies were found to be using workers’ tips to subsidize their own costs (the companies all eventually revised their policies — with DoorDash being the slowest to do so — and many workers continue to report low pay). In September, Uber made a baffling argument that its drivers aren’t core to its business as part of its rationale for why a new labor law targeted at gig economy apps didn’t actually apply to the company. And ride-hail companies have similarly been accused of not doing enough to prevent and investigate sexual assaults that occur during rides.

In every case, gig economy companies have argued that they are digital marketplaces matching sellers and buyers and are therefore not financially or legally responsible for things that happen on their platforms.

When it comes to sales tax, companies have an obvious business incentive to avoid charging it: keep prices low, keep customers happy, and keep sales up. And in the food delivery space, which is an increasingly competitive industry with tight margins, that’s an acute pressure.

“Right now there’s an arms race for customer acquisition,” said Sucharita Kodali, a principal analyst at Forrester who specializes in e-commerce. “As venture capital startups, the more growth they can exhibit, that’s still the signal of success, and any lever they can use to help showcase those metrics helps.”

In the past year, DoorDash has emerged as the unexpected market leader and fastest-growing food delivery app in the US, according to research firm Edison Trends, unseating market incumbent Grubhub. The company has aggressively expanded its business, putting pressure on an already crowded market.

If tax laws were more clear, food delivery companies would probably just absorb the cost of charging sales taxes on delivery fees and “move on,” Kodali told Recode. But, Kodali said, in “an age of ambiguity, if it helps them to showcase a better result then why not?”

But it also poses a risk. If states or cities find companies liable for taxes later, they could sue for years of back taxes, several tax experts told Recode. That’s what happened to travel website Expedia, which several cities accused of avoiding as much as $847 million in taxes on room fees. The company has long been embroiled in legal battles over these cases. More recently, the state of New Jersey recently sued Uber for over $650 million in unemployment and disability insurance taxes for allegedly misclassifying its workforce as independent contractors instead of employees.

Laws haven’t caught up with the gig economy

The tax codes governing food delivery apps like Grubhub, DoorDash, and Postmates vary significantly state by state, and they are changing as local governments grapple with how to adapt old laws to the new gig economy.

Generally, some laws in states like California and New York have provisions that could call for sales taxes on delivery and service fees to be collected, according to Scott Groberski, a managing director in state and local tax groups at accounting and tax firm Grant Thornton. Still, it’s very much a gray area and would vary based on the specifics of the contracts between restaurants and food delivery providers.

“With new technology, it’s extremely complicated determining what’s taxable and what’s not — I think this is something that continues to evolve even as we speak,” Groberski told Recode.

In California, for example, it depends if the company contracts with restaurants to “provide a delivery service only” or if it acts as a “retailer” of the food, according to Casey Wells at the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

Whether or not a food delivery app company is a retailer depends on the contracts it has with restaurants, Wells said, as well as if the app is marking up the price the restaurant normally charges for the food.

Wells declined to comment on whether or not the law would classify specific companies like DoorDash or Grubhub as retailers or not.

Some tax experts said it comes down to whether these companies are charging the restaurants they work with or only charging consumers. Grubhub, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Postmates all regularly partner with restaurants and charge them commission fees.

“I have a real doubt that Grubhub is overtaxing — the default rule should be that it’s taxable, that is the safer position,” said Holderness.

“In some cases, it may not be a question of tax avoidance or uncertainty so much as legitimate uncertainty about what the rules are,” said Steve Rosenthal, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Policies vary state to state, and the rules around taxing delivery fees are myriad and often outdated.

When asked about concerns tax experts raised about Uber’s sales and delivery tax policies, a spokesperson for Uber responded with the following statement:

“We collect sales tax on delivery fees where required, with particular attention to recently enacted marketplace facilitator laws. Although California has enacted similar legislation, there is an exception for delivery network companies. Accordingly, we do not believe it is appropriate for Uber Eats to collect sales tax on delivery fees from our users in California at this time. We are deeply committed to compliance, which includes ongoing assessment of developments in local legislation and state-issued guidance.”

DoorDash (which also owns Caviar) declined to comment.

In a statement to Recode, Postmates said it is in compliance with all regulations and tax laws in jurisdictions where it operates, and that it is “[w]orking with lawmakers across markets, both to ensure our operations remain consistent with evolving state-by-state guidance on the tax code, and to balance the unique nature of on-demand products with the goal of ensuring taxable revenues are always collected by the state.”

Grubhub, meanwhile, maintains that it’s in the right for collecting these sales taxes and denied that the food delivery app business models exempt companies from these collections.

“We have been audited by multiple states, multiple times, and in every case we were required to collect and remit sales tax on delivery fees,” said Grubhub’s CEO Matt Maloney.

The threat of regulation

In recent years, local lawmakers have increasingly scrutinized the tech industry. For example, more states are now charging sales tax on products that are purchased online. That’s because of a June 2018 Supreme Court Ruling, South Dakota v. Wayfair, which gave states the rights to demand more tax revenue from online companies that sell goods in their state, even if those companies don’t have a physical location in the area.

California politicians told Recode that they’re also thinking about how the gig economy collects taxes.

“I’m concerned about what appears to be a pattern of activity of these gig companies to not even find out what they should be doing by law,” said California Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, who authored the landmark labor legislation AB 5 that legally pressures companies like Uber and Lyft to reclassify contractors as employees. “It’s unfair competition. If you have a Dominos, for example, that is abiding by the rules, they’re taking the appropriate sales tax out, they’re not going to be able to compete with an app that’s doing all those things.” Dominos is one of the only major pizza chains that does its own delivery, independent of food delivery apps.

If there’s a lesson to be learned by food delivery startups from tech successes of the past, it’s that creatively interpreting outdated regulations can help them get ahead. Amazon largely skipped out on collecting sales tax for third-party seller products until a few years ago when it was facing state regulations to do so — but by then it was already the top online retailer. Uber ignored licensing rules in many states but became the leading ride-hail company in the meantime. And Airbnb delayed its obligation to collect taxes and enforce zoning rules by suing several cities where it operated.

In all those fights, regulators were slow to keep up with tech companies, which took advantage of that to quickly become market leaders, meaning they could afford costly legal battles. But in an era when tech is facing a reckoning with the public and increased political scrutiny, that might change, and regulators may start applying stricter rules to companies like DoorDash and Postmates.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2D4dPHQ

0 notes

Text

DoorDash and Uber Eats aren’t collecting sales tax on delivery fees in some states. That could be a problem.

Discrepancies between the sales tax practices of companies like DoorDash, as well as its competitors like Uber Eats, Postmates, and Grubhub are raising questions | Getty

It could be the latest business practice in the gig economy to raise regulatory questions.

The food delivery company Grubhub said it has collected hundreds of millions in taxes for delivery and service fees in dozens of states since at least 2011. But Recode has found that in some of those same states, Grubhub’s top rivals in the delivery space, including DoorDash, Postmates, and Uber Eats, don’t appear to be collecting a cent. This discrepancy puts those rivals in a precarious position if regulators take notice and object.

Several tax experts Recode interviewed said food delivery app companies’ tax practices could raise legal concerns. The sales taxes in question are on fees that can amount to as much as a third of the total price of food orders — or at least $120 million per year of taxable dollars on the sales of major food delivery companies in California and New York alone, based on Recode’s calculations on an estimated market size from research firm Forrester. If you account for all of the US, that could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

The experts told Recode these tax practices could be a liability not just for the food delivery apps but also for the restaurants whose food they deliver. Both the apps and the restaurants could later be on the hook for paying taxes that apps aren’t currently collecting. It’s another example of how existing laws haven’t yet adapted to the gig economy — and in the meantime, these tech companies are taking advantage of the loopholes.

“I would feel very uncomfortable if I were tax counsel for one of those companies if those taxes weren’t being collected,” said Hayes Holderness, assistant professor at the University of Richmond School of Law and a state tax policy expert. Holderness called it an “aggressive” and “risky” decision for companies not to charge sales taxes on delivery — but a “not necessarily unreasonable” stance, and one that could be debated in court. For companies in the competitive food delivery market, the immediate business benefit of keeping sales taxes lower could also outweigh the legal risks, he said.

Gig economy companies have historically loosely interpreted the law — or in some cases skirted it entirely — to benefit their business models, and regulators are increasingly examining their behavior.

The Washington, DC, attorney general announced earlier this week he’s suing DoorDash, arguing that the company misled customers and pocketed workers’ tips. Earlier this year, politicians raised concerns about wage theft when Instacart, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and several other companies were found to be using workers’ tips to subsidize their own costs (the companies all eventually revised their policies — with DoorDash being the slowest to do so — and many workers continue to report low pay). In September, Uber made a baffling argument that its drivers aren’t core to its business as part of its rationale for why a new labor law targeted at gig economy apps didn’t actually apply to the company. And ride-hail companies have similarly been accused of not doing enough to prevent and investigate sexual assaults that occur during rides.

In every case, gig economy companies have argued that they are digital marketplaces matching sellers and buyers and are therefore not financially or legally responsible for things that happen on their platforms.

When it comes to sales tax, companies have an obvious business incentive to avoid charging it: keep prices low, keep customers happy, and keep sales up. And in the food delivery space, which is an increasingly competitive industry with tight margins, that’s an acute pressure.

“Right now there’s an arms race for customer acquisition,” said Sucharita Kodali, a principal analyst at Forrester who specializes in e-commerce. “As venture capital startups, the more growth they can exhibit, that’s still the signal of success, and any lever they can use to help showcase those metrics helps.”

In the past year, DoorDash has emerged as the unexpected market leader and fastest-growing food delivery app in the US, according to research firm Edison Trends, unseating market incumbent Grubhub. The company has aggressively expanded its business, putting pressure on an already crowded market.

If tax laws were more clear, food delivery companies would probably just absorb the cost of charging sales taxes on delivery fees and “move on,” Kodali told Recode. But, Kodali said, in “an age of ambiguity, if it helps them to showcase a better result then why not?”

But it also poses a risk. If states or cities find companies liable for taxes later, they could sue for years of back taxes, several tax experts told Recode. That’s what happened to travel website Expedia, which several cities accused of avoiding as much as $847 million in taxes on room fees. The company has long been embroiled in legal battles over these cases. More recently, the state of New Jersey recently sued Uber for over $650 million in unemployment and disability insurance taxes for allegedly misclassifying its workforce as independent contractors instead of employees.

Laws haven’t caught up with the gig economy

The tax codes governing food delivery apps like Grubhub, DoorDash, and Postmates vary significantly state by state, and they are changing as local governments grapple with how to adapt old laws to the new gig economy.

Generally, some laws in states like California and New York have provisions that could call for sales taxes on delivery and service fees to be collected, according to Scott Groberski, a managing director in state and local tax groups at accounting and tax firm Grant Thornton. Still, it’s very much a gray area and would vary based on the specifics of the contracts between restaurants and food delivery providers.

“With new technology, it’s extremely complicated determining what’s taxable and what’s not — I think this is something that continues to evolve even as we speak,” Groberski told Recode.

In California, for example, it depends if the company contracts with restaurants to “provide a delivery service only” or if it acts as a “retailer” of the food, according to Casey Wells at the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

Whether or not a food delivery app company is a retailer depends on the contracts it has with restaurants, Wells said, as well as if the app is marking up the price the restaurant normally charges for the food.

Wells declined to comment on whether or not the law would classify specific companies like DoorDash or Grubhub as retailers or not.

Some tax experts said it comes down to whether these companies are charging the restaurants they work with or only charging consumers. Grubhub, DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Postmates all regularly partner with restaurants and charge them commission fees.

“I have a real doubt that Grubhub is overtaxing — the default rule should be that it’s taxable, that is the safer position,” said Holderness.

“In some cases, it may not be a question of tax avoidance or uncertainty so much as legitimate uncertainty about what the rules are,” said Steve Rosenthal, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. Policies vary state to state, and the rules around taxing delivery fees are myriad and often outdated.

When asked about concerns tax experts raised about Uber’s sales and delivery tax policies, a spokesperson for Uber responded with the following statement:

“We collect sales tax on delivery fees where required, with particular attention to recently enacted marketplace facilitator laws. Although California has enacted similar legislation, there is an exception for delivery network companies. Accordingly, we do not believe it is appropriate for Uber Eats to collect sales tax on delivery fees from our users in California at this time. We are deeply committed to compliance, which includes ongoing assessment of developments in local legislation and state-issued guidance.”

DoorDash (which also owns Caviar) declined to comment.

In a statement to Recode, Postmates said it is in compliance with all regulations and tax laws in jurisdictions where it operates, and that it is “[w]orking with lawmakers across markets, both to ensure our operations remain consistent with evolving state-by-state guidance on the tax code, and to balance the unique nature of on-demand products with the goal of ensuring taxable revenues are always collected by the state.”

Grubhub, meanwhile, maintains that it’s in the right for collecting these sales taxes and denied that the food delivery app business models exempt companies from these collections.

“We have been audited by multiple states, multiple times, and in every case we were required to collect and remit sales tax on delivery fees,” said Grubhub’s CEO Matt Maloney.

The threat of regulation

In recent years, local lawmakers have increasingly scrutinized the tech industry. For example, more states are now charging sales tax on products that are purchased online. That’s because of a June 2018 Supreme Court Ruling, South Dakota v. Wayfair, which gave states the rights to demand more tax revenue from online companies that sell goods in their state, even if those companies don’t have a physical location in the area.

California politicians told Recode that they’re also thinking about how the gig economy collects taxes.

“I’m concerned about what appears to be a pattern of activity of these gig companies to not even find out what they should be doing by law,” said California Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, who authored the landmark labor legislation AB 5 that legally pressures companies like Uber and Lyft to reclassify contractors as employees. “It’s unfair competition. If you have a Dominos, for example, that is abiding by the rules, they’re taking the appropriate sales tax out, they’re not going to be able to compete with an app that’s doing all those things.” Dominos is one of the only major pizza chains that does its own delivery, independent of food delivery apps.

If there’s a lesson to be learned by food delivery startups from tech successes of the past, it’s that creatively interpreting outdated regulations can help them get ahead. Amazon largely skipped out on collecting sales tax for third-party seller products until a few years ago when it was facing state regulations to do so — but by then it was already the top online retailer. Uber ignored licensing rules in many states but became the leading ride-hail company in the meantime. And Airbnb delayed its obligation to collect taxes and enforce zoning rules by suing several cities where it operated.

In all those fights, regulators were slow to keep up with tech companies, which took advantage of that to quickly become market leaders, meaning they could afford costly legal battles. But in an era when tech is facing a reckoning with the public and increased political scrutiny, that might change, and regulators may start applying stricter rules to companies like DoorDash and Postmates.

from Vox - All https://ift.tt/2D4dPHQ

0 notes

Text

Michael Hiltzik: Uber, Lyft face a gig labor law reckoning

If there were any doubt that California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra and his fellow regulators were getting fed up with the continued flouting by Uber and Lyft of the state’s new gig worker law, it was dispelled by their recent legal motion to force the companies into compliance.

In their June 24 filing, Becerra and the city attorneys of Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco asked a state judge in San Francisco to issue a preliminary injunction ordering the companies to immediately classify their drivers as employees rather than independent contractors.

That’s what’s required by the state’s gig worker law, known as AB 5. “It’s time for Uber and Lyft to own up to their responsibilities and the people who make them successful: their workers,” Becerra said the day the motion was filed.

After eight years of looking the other way, California officials are finally enforcing the rule of law against these so-called gig companies.

Veena Dubal, UC Hastings School of Law

It should surprise no one that Uber, Lyft and other gig economy companies see it differently and are girding for a fight — including a multimillion-dollar ballot initiative campaign — in which their survival may be at stake.

Designated as independent contractors, drivers are unprotected by minimum wage and overtime rules, receive no workers’ compensation or unemployment insurance benefits, and have to pay for their own gas, insurance, vehicle maintenance and Social Security taxes. They have no right to join or organize into a union.

The dodge of designating employees as independent contractors isn’t new. It was born in the notoriously anti-labor Taft-Hartley amendments of 1947, which first carved out the exception.

But it has become common in an entrepreneurial economy in which high start-up costs prompt business owners to search out savings in a marketplace in which “employment taxes and other workplace liabilities appear to be low-hanging fruit,” as Elizabeth J. Kennedy of Loyola University in Maryland has observed.

Uber, Lyft and other gig economy companies have exploited America’s lax workplace regulations to build businesses addicted to forcing the cost of business onto the shoulders of essential workers.

Even so, it’s unclear that their exploitation of workers has yielded a sustainable business model. Uber and Lyft acknowledge in financial disclosures that they might never become profitable under current circumstances and that things would become worse if they had to classify their drivers as employees. (Uber has lost $15.7 billion and Lyft $4.2 billion in the last three calendar years.)

Becerra’s action — the latest chess move in a lawsuit he originally filed May 22 — is just one of several prongs California officials have aimed against gig employers over alleged misclassification of employees in recent weeks. San Francisco Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin sued the delivery service DoorDash on June 16 for classifying its delivery workers as independent contractors.

One week earlier, the California Public Utilities Commission, which had carved out a special regulatory designation for “transportation network companies,” informed the companies that as of last Jan. 1 their drivers “are presumed to be employees” and advised that the law requires them to provide the drivers with workers compensation benefits starting July 1.

Today my office initiated a lawsuit against @doordash for illegally misclassifying employees as independent contractors.

“I assure you this is just the first step among many to fight for worker safety and equal enforcement of the law”#PromisesKept

https://t.co/srO3agGWTa

— Chesa Boudin 博徹思 (@chesaboudin) June 16, 2020

Becerra’s action has been lauded as an overdue initiative to protect workers’ rights.

“After eight years of looking the other way, California officials are finally enforcing the rule of law against these so-called gig companies,” Veena Dubal, a labor law expert at UC’s Hastings School of Law, told me. “Because regulators chose not to enforce existing labor laws against the companies, they were allowed to grow precarious work — not just in this state, but all over the world.”

This isn’t a one-sided battle. The companies are fighting Becerra’s lawsuit and, perhaps more consequentially, have placed a measure on the November ballot to overturn AB 5.

Their measure, which will appear as Proposition 22, would effectively designate app-based drivers such as those working for Uber and Lyft permanently as independent contractors and forbid the state or localities to enact ordinances to treat them as employees.

The companies have provided the initiative campaign with a war chest of $110 million so far — $30 million each from Uber, Lyft and DoorDash and $10 million each from Postmates and Instacart, two other delivery services. So it behooves us to take a closer look at the measure.

Proposition 22 attempts to establish a new workplace model — a hybrid of the independent contractor and employment models.

The companies say it would preserve the “flexibility” to set one’s own work days and hours they say is valued by drivers who wish to work around school, caregiving and other work, while guaranteeing minimum pay and access to health coverage.

The measure would guarantee drivers earnings of at least 120% of prevailing hourly minimum wages, a subsidy for health coverage and protection against arbitrary firing.

The companies maintain that the vast majority of their drivers favor remaining independent contractors. Yet that’s misleading because drivers fall into two discrete camps. One is composed of true part-timers who record minimal hours, often abandon the work entirely after a few months, and appreciated the vaunted flexibility. The other is full-time drivers who may be spending 40 to 50 hours a week on the road.

Some 70% to 80% of drivers may drive 20 hours a week or less, says Harry Campbell, a former driver for Uber and Lyft who now runs therideshareguy blog, an information service for drivers. Full-timers, while less numerous, account for more than 50% of the hours worked through the companies’ app.

“For a majority of the drivers this isn’t a full-time income, so it shouldn’t be shocking that they want to stay independent contractors,” Campbell says. “But the drivers working 40 to 50 hours a week are basically working like employees without any of the benefits or protections. They’re the ones spearheading the effort to hold the companies accountable to treat drivers like employees.”

And they’re the drivers who would bear the brunt of the changes wrought by Proposition 22. Campbell says, however, that when even part-timers become educated about what AB 5 would do for them and that the law wouldn’t prevent the companies from allowing them some of the flexibility they crave, “some of them change their opinion of the law.”

There can be no doubt that the principal beneficiaries of Proposition 22 would be the companies themselves. If they were forced to classify their drivers as employees, according to the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, the resulting higher costs would “decrease these companies’ long-term profitability, which could reduce these companies’ stock market values and stock prices.”

The measure would impose some new costs on the companies, but those costs would probably be “minor,” the Legislative Analyst’s Office reckons.

Indeed, the compensation and benefits the companies would pay under Proposition 22 would fall far short of the costs their drivers must shoulder. The UC Berkeley Labor Center estimated in October that 120% of the California hourly minimum wage of $13 in 2021, or $15.60, would effectively shrink to $5.64 an hour because of provisions in the initiative.

For example, drivers would be paid only for “engaged” time, from when they are en route to pick up a passenger or delivery to when they drop off the rider or package, not for waiting time between assignments. That constitutes as much a one-third of their work time, Berkeley estimated, reducing the $15.60 to only $10.45.

Some drivers would gain from a stipend of up to about $367 a month for health insurance, which could be applied to Affordable Care Act plans from Covered California or other plans. But that would be granted only to drivers averaging 25 engaged hours a week or more. Those with 15 to 25 hours would receive half as much, and those with fewer than 15 hours would receive nothing.

“The vast majority of drivers would not qualify” for the benefit, Berkeley says.

Uber and Lyft have chosen to emphasize the purported consequences of enforcing AB 5, rather than the plain facts of their labor relationships. They , paint a picture of an army of disenfranchised drivers cast aside and unable to ply their trade.

They even hint that AB 5 could put them out of business entirely. Stacey Wells, a spokeswoman for the Proposition 22 campaign, said that if the initiative fails the companies might have to pare their driver ranks, which number as many as 400,000 in California, by as much as 90% to accommodate the added costs of treating drivers as employees.

Yet by any reasonable definition, the companies’ drivers are employees. According to rules set down by the California Supreme Court in a 2018 decision and codified in AB 5, businesses must consider workers employees unless they can meet a three-part test showing that the workers are free from the control and direction of the hiring business, that they’re performing work outside the normal course of the hirer’s business, and they customarily work independently in the same trade or occupation as the work they’re doing.

UC Berkeley calculates that hidden costs would reduce the minimum earnings guaranteed drivers by Uber and Lyft in Proposition 22 by nearly two-thirds.

(UC Berkeley Labor Center)

Becerra maintains that Uber and Lyft can’t meet any of those elements. The drivers are engaged in the companies’ main business of transportation; their compensation is set by the companies, which can change it unilaterally; their performance is monitored by the companies; with the exception of the choice of the hours they wish to drive, all other terms and conditions of their work are set by the companies.