#i miss dorothy west.... so much...

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

go white girl go

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luz loves the Good Witch Azura, who guides her not in a literal sense but metaphorically; It’s a reference to the Wizard of Oz, which has the Good Witch of the North and the Good Witch of the South! Luz is Dorothy, a young American girl transported to another world, who starts her journey with a magical item (Ruby Slippers/Portal) that is a way back to the home she misses. I guess you could say Eda and/or Lilith fit the Good Witch roles, too!

Remember her girlfriend Amity’s favorite book Otabin, whose titular protagonist found friends in the Tin Boy and Chicken Witch? Tin Boy, Tin Man; An anthropomorphic animal like the Cowardly Lion; And someone connected to sewing, such as the Scarecrow! I guess that also makes Amity a Dorothy of her own, given how much all three (who like in the film, aren’t exactly real) comfort her… Luz and Amity parallels!!!

King is Toto as the cute animal sidekick… And perhaps Willow, Gus, and Amity are the three sidekicks, representing their goals; Willow wishes she wasn’t so cowardly and could stand up for herself, Gus wishes he wasn’t so dumb for being tricked by others, and Amity wishes she had a heart to be a good friend!

And Hunter was Prince William at one point… Later in her journeys, Dorothy meets Princess Ozma, who is meant to be the rightful ruler of the land! Just as William is implied to be.

I’d also point out that Lilith dresses like the Wicked Witch of the West, during her tenure in the coven; She’s also the first ‘Wicked Witch’ that Luz has to face, so in that regard she’s the Wicked Witch of the East. She goes after Luz for the sake of the magical artifact that can bring her back home, though in Lilith’s case she doesn’t know this.

That’s because Belos is the true Wicked Witch of the West, a green witch who wants the magical item the protagonist starts the journey with, that is a way back home. He melts in water, a reference to real-life witch hunts drowning many of the accused in water. But he’s also the Wizard of Oz, a human man from the protagonist’s world who got stuck here before her, puts on the great facade of a powerful magic wielder ruling a city, but is in truth just a con artist who plans to go back home, and offers the protagonist the same. He wants witches dead…

#The Owl House#Wizard of Oz#Otabin#The Wizard of Oz#Luz Noceda#Amity Blight#Lilith Clawthorne#Emperor Belos#Philip Wittebane

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Angel behind the Curtain

The Metatron. A character we don’t know a lot about in the show but has become public enemy number 1 - funny isn’t it.

I’ve been putting off doing this for a while because I wanted to dedicate proper time and research into this character - who he is, what he is doing, and how he is being used. That’s what I’ve been doing for the past week or so and boy is it long. So consider this an introduction post to a series - the main parts are still under construction and review.

But here is a shorter part that didn’t really fit anywhere cleanly and was kinda just a side tangent my brain went on - so now it’s its own part. I know some of it has been discussed before but have some new additions with a sneak peak into what is to come

and for that we are going back into the Title sequence - yes I know I talk about it way too much.

So Mr. Floating Head

Obviously this has been linked to the floating head of The Wizard of Oz before

But I want to dive in a little further now that we have more instances of this in season two

Now I’ll admit it’s been a while since I have revisited the story so there might be more parallels I missed but for now I just want to focus on the wizard - with some light parallels

We get the Metatron as a floating head up in heaven during the trial -which would have been before/during episode one - where he task the archangels with finding Gabriel - and he almost seems amused about it.

When Dorothy and the others first meet the Great Oz he will only grant their wishes upon the defeat of The Wicked Witch of the West. Once they return back after succeeding they demand the Great Oz to fulfill his promises but Toto knocks down the curtain to reveal that the Great Oz is just some man. He then uses “humbug” to grant their wishes - kinda. Dorothy though is meant to join him on a hot air balloon so they can both go home - which she misses because she was chasing Toto. But enough of that

After Gabriel is found - then fucks off - the Metatron arrives in the bookshop with most not recognizing him until he prompts Crowley to “reveal” him. He then sends the archangels away with a “wait and see” about if they had done anything wrong - kinda granting their wish with them not getting in trouble. He then goes on to offer the Supreme Archangel position to Aziraphale and says to join him in going up to Heaven.

The Metatron is admittedly a better wizard than Oz - he for the most part removes his own curtain and makes sure Aziraphale is coming with him.

But you said we were going into the title sequence and you have just rambled about some old story parallels? Okok I’m going

I've talked before (here) about how those rickety walkways represent Heaven's plans/timeline for their version of Armageddon- but for this we are going to focus on the one in the theatre

Curtains are drawn - screen is burned - the way to the Second Coming revealed

I'm comparing this moment to the Metatron finally appearing in a corporation in front of the angels and revealing his name - the curtain pulled back.

At the last second the film is burned - right before they enter the lift the Metatron finally drops the act a little and reveals the name, The Second Coming.

And now on to the sneak peak for one of the things I will be doing a deep dive into - The Book of Enoch

I know Neil has said the Metatron has always been an angel but can’t throw the whole book away when he himself pulls from it

When we go through the burnt screen we see these mountains of junk and it is revealed they are walking up one that has a throne room on top.

In Enoch 1 he is given an angel guided tour of the cosmos and sees seven glorious mountains - three to the east, three to the south, one that was taller than the rest and like the seat of a throne with trees encircling it, one of which is identified as the Tree of Life - which is said to be given back to humans after judgement

I’m sensing some parallels but for now that is it - tune in later for some more Enoch and diving into the occult

Part 2 is up!!

#did i just compare Crowley and Toto? yes yes I did#disaster puppy at it’s finest#good omens#good omens 2#good omens meta#good omens analysis#good omens theory#good omens metatron#the metatron#aziraphale#crowley

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

XOXO

Ch. 14 A broken heart is fixed by another

-•-

Author’s note: I am so so sorry for the delay, i really took my vacations to relax and enjoy the time i had with my family and friends. I finally got to sit down and make this chapter. Hope you enjoy!

Warnings: Fighting and yelling

Taglist: @w31rdg1rl @mxtokko @loonymoonystuff @granstrangerphanthom @1lellykins @cangosleepnow @dreamspectrum @its-maemain @tamimemo @nightw-izhu @trasshy-artist @gabriiiiiiii

masterlist:

-•-

To admit that my father had shaken me up a little would tear apart a bit of my ego. I mean, all my life I have been going head to head with the man yet not once had I gone as far as I had now. I had sent a text to Tim, telling him that I would be spending Christmas Eve having dinner with my family to which he responded worriedly that if anything went wrong, the doors to the Wayne manor were always open. I finish getting ready for the dinner and call Donnie. Oh Donnie, he has been my driver ever since I was a child and constantly took me under his wing. I grab the bag that holds the presents I had bought the day I met Tim and take out Donnie’s. It was my small tradition with my family’s staff, every year on Christmas Eve, I would buy them a present as gratitude for the year of service. I had begun it when I was 13 and hadn’t stopped ever since. I see him waiting for me once I gather everything I need and open the door. He steps out of the car and opens the door for me showing me a small bouquet of my favorite flowers waiting for me next to where I usually sit.

“Oh Donnie, you are a sweetheart! Thank you so much!” I say and hug him once I stash all of my families presents in the trunk. I give him his present and smile as he gasps of joy. Long time ago, Donnie had told him that he had exchanged his silver harmonica for a watch for his wife. Unbeknownst to him, his wife had done the same thing and exchanged her locket for a case for his harmonica. In front of him sat a beautiful silver harmonica and a gorgeous golden locket, I had been able to track their missing belongings and bought and polished them for them. I feel Donnie shake as he brings me in for a hug and I don’t mention the tears that soak my coat. “Happy Christmas, Donnie, to you and Linda” I hug him tighter and smile. “happy Christmas, miss Vanderbilt!” He says smiling and we both get in the car. The ride to Vanderbilt mansion was pleasant at best. He had decided to give an update on how my family have been. Aurora and my mother had moved to the West wing ever since the debutants ball. My sister was enraged about the selling of my painting and was doing almost every she could to find a way to buy it back. My mother was doing her best to help her in that. Charlisse and my father remained in the east wing. Charisse what stayed trying to keep father company but it was no use, he has been stuck in his study the entire time and only seemed to go out for supper. Not only that, my grandmother’s plane had been delayed due to the weather conditions and she was not going to be present until who knows when. That bit of news is what dulled me the most I think. It was no secret I was my grandmother’s favorite and it would have been a relief to have someone my father can’t control.

Finally, we arrive. Donnie opens my door and helps me carry my presents inside. There, Dorothy, my maid, takes them and goes to place them under the tree. “wait! Thea!” I say and she stops looking at me, waiting for my response. I take the bags and pull out three gifts. I put two in my purse and give the las one to her, “Happy Christmas, Thya!” I say with a big smile. She gives me a hearty laugh and wishes me a happy Christmas. She also tells me that I will find her present for me in my room. I smile and go on a search for my favorite butler. I find him ordering the kitchen staff around for the dinner and give him his present whilst wishing him a Happy Christmas. I give him a hug and run upstairs to drop my coat. In my bed, two beautiful presents are laid. I place the flowers in my nightstand and open them. Dorothy gave a three books, one of Monet, one of Van Gogh and another on Da Vinci; and Bartie gave me a gorgeous knitted sweater with a kite saying his wife made it for me. I hug all of my presents and decide to finally show up at the dining room, knowing my father will be impatient by now.

Before I enter the dinner, I straighten my back and wipe my dress making sure everything is perfect. Finally, Bartie opens the door and announces my arrival. Aurora comes straight away towards my and hugs me tightly. She whispers in my ear, “I miss you baby sis..and no matter what happens today, I am on your side!” She pulls away and smiles at me. Mom walks towards me next almost cautiously, last time we had spoken I had not been that welcoming towards her. I open my arms and she releases a sigh and envelopes me in her arms. “Hi, my little pearl, Merry Christmas” she says as she squeezes me tightly. “Mom! You are leaving me without air” I laugh out causing Aurora and my mother to laugh. Next is Charlisse. She squeezes me in a big hug and tries to ruffle my hair. I deflect it with a laugh and pat it down. Finally I meet my father’s gaze.

“Father”

“Y/n”

We stay staring at each other until, Mark, Aurora’s husband coughs and I look at him. He gives me a big hug and we laugh. Charlisse’s husband, Antoine, raises a glass at me and gives me a wink. I roll my eyes at him and discreetly give him the middle finger. He laughs, choking on his drink and nods in approval. They both have always been like my older brothers. Finally, we begin and sit down to eat. Like always, Dorothy, Bartie, and Donnie, with some of the other staff, sit down to eat with us in order to celebrate the festivities. We begin mindless chatter around the table as we eat. Even though it’s still a little tense between my father and I, we engage in some conversation. We finish dinner and change into the living room.

Everything was going perfect, until it wasn’t.

I was telling Charlisse about the ski trips with Tim when my father lets out a displeased grunt. We ignore him for the most part until he interrupts. “Where is Timothy by the way? Is he not supposed to be your boyfriend?” I turn to him and narrow my eyes. “Whatever you are implying father, it is far from that. You specifically told me tonight was about family and that I couldn’t bring him” I defend and he glares at me, “I am sure that would have not stopped a real gentleman, for example, Francis would have come and joined us” he said waiting for my reaction. I catch Charlisse scrunch up her nose in distaste. During the last few weeks, my sisters and I had a conference call where they asked about Mr. Morris. Aparantly my sisters had no knowledge of how much of a creepy man he was. Charlisse thought my father was just going to the extremes in order to push me towards the family business and was even entertained by me defying my father’s authority, but once she had heard everything, she was no longer amused. “Father, I don’t believe that is exactly fair for Y/n” Charlisse began but was interrupted by my father screaming, “I say what is fair in this household and Y/n has done nothing to honor our family name! She has only raked it through the mud parading with that boy toy of hers and engaging in activity unfit for a Vanderbilt!”

“I hardly think it’s something to shame her father, she was just having a little fun” tried Charlisse again and Aurora continued with “She’s young and in love, that’s all”

Our father was positively fuming. “You see what you have caused, Y/n. Your little act of rebellion has caused your sisters to step out of line and it might cause them their future titles. We wouldn’t want that, would we?” He said darkly looking at both of my sisters who shrunk under his gaze and gave me an apologetic smile.

“Don’t be unfair on the girl, William.” My mother tried to intervene when I interrupted her,

“Oh so I am a little rebel now! Is that what you are calling it?!?! Is that what you call anyone that doesn’t bend to your every will just because heaven forbid William Vanderbilt doesn’t get what he wants!?” I yell back and my father’s fury rises once again

“Enough! It’s Christmas Eve, for heaven’s sake! We are spending time as a family and these matters should be left for later!” My mother tried once again but it wasn’t enough.

“You are young, Y/n, there are many things that you don’t understand-“

“And you are old father, there are many things you have forgotten!” I responded looking at him dead in the eyes

“What is that supposed to mean?” He got closer to me, my mother was doing her best to push him back and Antoine and Mark stood up, ready for anything that was to come.

“You are selfish, arrogant, and cruel. You believe that everything should be done according to your plans yet you forget that we are our own people! We should live how we like and love who we want and be who we choose to be. You push your precious hotel agenda so far down our throats that you suffocate us! The only thing you do is push our family apart instead of bringing it together. I remember you used to tell us how much you hated your dad for forcing you to take on the company yet yOU DO THE SAME DAMN THING TO US!” I threw in his face and then snapped my hand to my mouth. My sisters gasped and my mother looked between my father and me. Everyone stood still for a moment. That wasn’t a subject we never brought up.

“Leave.” Was all my father said and it was the restraint in his body that made me run. I grabbed my purse, took a random coat from the closet and ran out of the manor. I could hear people calling out my name and yelling at my father but I paid no mind to it, I just ran. It was freezing, snow had begun falling and I was just in my short dress and heals. I knew Wayne manor was close so I just ran and ran until I got to its shiny golden gates. There I pressed the buzzer as many times as I could until I heard a posh British accent answer, “Yes?”

“H-h-hi A-a-Alfred, is T-t-Tim the-ere?” I asked, shivering.

“Goodness miss, YN, what are you doing in the snow! Master Tim! There’s an urgent matter you need to attend to, come quick!” Alfred said rapidly recognizing my voice and opened the gate. I began the long walk it takes to get to the manor and in the distance I see a body open the door. It starts to run towards me as I get closer and closer. Finally, it clears up and I recognize that shadow to be Tim.

“Fuck, angel what are you doing here at this hour and under so much snow, come on let’s get you inside” he says as he drapes another coat on me and picked me up. “I didn’t know where else to go…” I said softly and he squeezes me harder. I don’t know if it was because how much I am shaking or because of what I said.

Quickly I am taken in and brought to Tim’s room. He places me in the toilet and begins heating a bath for me.

“There you go, I’ll go get you a few things to change into later, see if Steph, Babs or Cass has something that can fit you” he says and is about to leave when i realize I don’t want to be alone right now, “Tim…”

“Yes?” He says turning back to me and looks at me, worry clouding his eyes.

“Can you stay with me?” I ask and he stiffened, suddenly I remember our situation and what I am asking of him, “never mind, sorry if I-“

“Let me get everything that you might need and I’ll be right back, okay? I’ll come back” he says softly.

The bath fills up and stops suddenly, I begin to shed the layers of coats I have until I am left only in my soaking dress. I am about to take it off when I realize the zipper is frozen and it is getting difficult for me to take it off. I struggle for a few seconds until Tim arrives again.

“I got you some pants and socks from Babs and a shirt and clean underwear from Steph. I also have many sweaters you can borrow. They are in the bed and here are some shampoos, conditioners, bath bombs, soaps and essential oils. Let me place some on the tub, Alfred said they can help you not get sick and help your body relax and recover as well. Why aren’t you our of your dress?” He rambles as he pours the liquids until he sees my struggling figure.

“It’s stuck and ruined” I say still, struggling.

“Let me help you, angel” he says softly. I turn around and feel his warm fingers on my shoulders. He ties my hair up and behind to tug the zipper down as careful as he can. Once it’s open, he turns around and lets me take the rest of my clothes off. I sink in the tub and almost moan out of relief. The warmth starting to seep into my bones.

“You can turn around, Timmy” I say laughing softly at his stiff and awkward posture, “the bubbles cover me quite well”

He turns around slowly and sits on top of the toilet. I can see his face red with embarrassment and muffle a giggle with my hand. He looks positively adorable. His eyes take in my face with soft adoration.

“What happened, angel?” He asks softly. I let out a sigh and sink completely into the bath. Thankfully the tub is big enough to still cover me completely. When I come back up, I see Tim rolling his sleeve and pouring shampoo in his hands. He pulls a stool to get sit closer to me in the bathroom and softly whispers “come here”

I get closer, changing positions and giving him my back. As he begins to wash my hair with utter care and devotion I begin to tell him everything that happened. He makes sure to listen to every single one of my woes and hums in response as he works the tangles out of my hair and massages my scalp. He rinses and gets the conditioner and I continue my rant. Somewhere along the line, I begin to cry, exhausted by both the emotions of the day and the horrible walk here. He rinses again and begins to pour soap into his hands. He whispers softly, “may I?” And I nod as he begins to massage my neck and shoulders. I finish my account and just numbly state at the wall.

“Well, you are safe now, safe and warm. We have an amazing feast going on, Alfred’s treat if you are hungry. They just started the movie marathon and soon we will be playing a bunch of board games, so there’s that. Alfred said you are lucky to have gotten here so fast cause the storm got stronger and we are most probably snowed in, which you don’t have to worry about because we have a lot of guest bedrooms. You are alright okay” he speaks rinsing the soap out of his hand, “and I’ll stay here as long as you need me here.” He gives me a soft kiss on the head.

We stayed there for a while until I decided to get out finally feeling warm enough and relaxed. He hands me a towel and leads me to his room where he turns around and let’s me chance into everything. I ask him for a sweater and he searches for one and and tells me to guard it because it is his favorite as he winks. That gets a laugh out of me. Finally we head downstairs where Steph bolts and gives me a hug, “girl! Next time call Tim! Don’t walk around in the snow alone!!” She says making me smile sheepishly. Everyone speaks in agreement. The Wayne’s hold a very special place in my heart and their worry for me just secures that place even more.

“So, Tim said movies and game night, Jason, Damian, ready to get your asses beat by me again?” I ask smiling and Jason looks insulted whilst Damian scoffs half heartedly and responds, “you wish!” As the rest holler.

We spend the rest of the night watching Christmas movies and playing board games and I laugh so hard the evening I almost forget the events prior to this evening. Once we all retire, Tim starts walking me to one of the guest rooms. I hesitate before going in…I really don’t want to spend the night alone knowing that I have probably been casted as an outsider by my father and shunned from the family. It must have been visible in my face because Tim puts his hand out and says, “you can spend the night in my room, I don’t mind”

I take his hand and he leads me back to his room where an extra toothbrush is set. We wash our teeth and both get under the covers, each on one side of the bed. I try to get some sleep but the shudder from the cold returns. I try to contain it as much as possible so that I don’t wake Tim. Suddenly I feel a hand get a hold of my waist and pull me towards a body.

“You’re freezing, come here” he says and i whisper a small thanks.

“It’s a surprise you are going to bed, Timmy” I say and he must have understood the implications of my statement cause he answers, “Crime usually lowers these days because of the holidays and the excessive cold so we don’t usually patrol around this time as much. Bruce might go out and sometimes one of us if we want but it is rarely the case so this is the one time a year we get to lay back and relax.” I feel him murmur into the crook of my neck. He wraps his arms around me and cuddles closer to me, “plus, I always sleep better when you are around so why would I waste a chance like that” he says and I feel my face warm up. I take one of his hands and bring it to my lips giving it a soft kiss and say, “thank you for everything, Timmy.” In return, he squeezes me harder and says, “Merry Christmas, angel”.

And we both fall asleep into a blissful slumber.

-•-

#batfamily#tim drake#dick grayson#jason todd#batman#batfam#cassandra cain#alfred pennyworth#stephanie brown#damian wayne#duke thomas#bruce wayne#batfamily social media#batfam dc#batfamily x you#batfam x you#batfam socialmedia au#batfamily x reader#batfam x reader#batfam imagine#batfam au#dc batman#tim drake x fem!reader#tim drake x you#tim drake x reader#tim drake imagine#tim drake x y/n#dc social media au#dc reader insert#dcau

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

So you want to know about Oz! (5)

Now that we looked at the MGM-continuity of movie and cartoons adaptation, I propose you in those post some adaptations that are either more in line with the original novels or... just not following either the novels or the MGM movie, and just doing their own thing. Since there is a lot of Oz adaptations, for this movie I will stay by American productions, post-1939.

First my three faves, and the rest will be under the cut.

2005's The Muppets' Wizard of Oz

This movie did quite poorly upon its release - and of all the Muppets movies, it is not considered to the best in any way. There is notable use of some old CGI that aged very poorly when it comes to the Wizard's scenes... But, not only does it have one of the most hilarious depiction of the Witches of Oz ever (what do you expect when they are played by Miss Piggy?) and some cool songs - this movie has the honor of being the most book-accurate, book-faithful adaptation of The Wizard of Oz there ever was. (Well outside of Japanese animes I'll talk about later). Yep... this Muppets parody is the closest you can get to experiencing the original novel as a movie. Crazy, right?

2011's The Witches of Oz

Originally it was released as a mini-series in two parts ; and in 2012 it was recut and edited as a single movie known as "Dorothy and the Witches of Oz" (but the single-movie version deleted a lot of scenes and segments from the complete mini-series). It tells a sort-of sequel to the Oz books (yes ALL of the Oz books), while mixing it with urban fantasy - as young real-life Dorothy, all grown-up in 2000s Oz, is depicted as the current author of Oz books, only for her to discover the fictional adventures in Oz that were written about her are real, and Oz is coming to New-York to get her...

Now... this mini-series aged VERY badly. The special effects are so cheap, most of the characters are insufferable, the plot is very weak... BUT! BUT this mini-series deserves to get some attention and to be known due to specific elements, such as, the most badass depiction of Langwidere ever ; Christopher Lloyd delightfully playing the Wizard of Oz... And the Wicked Witch of the West! This incarnation of the Witch is without a doubt one of my favorit reimaginings of the character, striking the perfect balance between the character of the original novel and the MGM Wicked Witch. Just in design she is the coolest Wicked Witch of the West there ever was. Too bad the rest of the mini-series is... quite cringe.

2017's Emerald City

Yet another proof of the "Oz curse" that plagues most of Oz adaptations - because the series got cancelled after its first season, leaving the show unfinished.

What is Emerald City? It was an Oz television series from the era of "post-Game of Thrones". Since the success of GoT, every channel and network tried to create its own dark and gritty big-budgeted high fantasy series... And "Emerald City" is what happened when Oz got caught in the trend.

People were very divided on the show (hence why it ended up cancelled) - some people adored its beginning and got tired of it by the end, others hated the first episodes but by the final ones were eagerly awaiting for the next season. On one side, most people agree that it is too much and that the show handled itself in a strange way, everything being a bit crammed-in. This TV show is actually adapting simultaneously THREE different Oz novels (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, The Marvelous Land of Oz, Ozma of Oz), all mixed together in a new, dark, adult iteration of Oz, so yes, that's a LOT.

However the show does work out several very cool and interesting concepts, playing around with both the MGM and the novel heritages. And while the story can get a bit convoluted due to the so-many plots and subplots mixing each other in a complicated way and not giving each other enough time to breath, the visuals are 10/10. There was a real visual effort on this show that makes it entirely worth the watch, if just as an eye-candy. They literaly used GAUDI ARCHITECTURE for the Emerald City, come on, how cool is that?

And also it is one of these shows were several actually working languages were created by experts, so that's always cool. I always stand by fictional linguistics.

Now I'll go a bit quicker for these ones because else it's going to be one LONG post:

In the 1960s, there was one animated show that dominated the Ozian landscape. 1961's Tales of the Wizard of Oz.

One of the early creations of the future Rankin/Bass studios, it is a cartoon that reuses the settng and characters of "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz"... But not the plot X) Basically Dorothy and Toto end up entering Oz by... by a hole, as if she was Alice. And there she meets her companions and each episode is about them trying to have a wish granted by the Wizard of Oz, or trying to avoid the schemes of the Wicked Witch. So... it is quite a VERY loose adaptation, and the modern cartoon "Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz" is kind of a modern heir to this old cartoon.

After 114 episodes, there was an animated special created to conclude the show. Called "Return to Oz", it IS actually an adaptation of the plot and events of "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz"... But happening after all of the events of the cartoon, and thus taking a different direction in terms of set-up.

1969's The Wonderful Land of Oz

This low-budget movie was an adaptation of the second Oz book, "The Marvelous Land of Oz". There's quite a lot of interesting stories surrounding this production - from Judy Garland supposedly having been intended as the narrator, to the background actresses having appeared in nude films created by the movie's director... However the movie tend to be ignored or forgotten compared to the other 60s Land of Oz adaptation...

1960's "The Land of Oz". First episode of the second season of Shirley Temple's Storybook

This was a much more famous adaptation of "The Marvelous Land of Oz", if only because of Shriley Temple's name. Retrospectively, I should have added it in my previous Oz post because this mini-movie takes a lot of visual cues from the MGM's Wizard of Oz, such as the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman being designed after their MGM incarnation, or Glinda's outfit calling for the MGM Glinda's design.

1980's "Thanksgiving in the Land of Oz"

An animated special for Thanksgiving of the year 1980, which is - as the title says - about Dorothy going to celebrate Thanksgiving in Oz. In 1981 it was re-cut to become "Dorothy in the Land of Oz" (with most Thanksgiving references being removed so the animated short could be aired at any time of the year - which is quite a challenge since the special is ALL about Thanksgiving... Dorothy is literaly brought to Oz by a "giant green turkey ballooon", come on!)

1987's Dorothy meets Ozma of Oz

This animated middle-sized movie is an adaptation of the novel "Ozma of Oz", and remained for quite a long time the only adaptation of Ozma of Oz alongside Disney's Return to Oz.

1997's The Oz Kids

A direct-to-video cartoon series that is just what it says. We follow the adventures of the children of the various protagonists of the Oz novels. Dot and Neddie, Dorothy's children ; Bela and Boris the children of the Cowardly Lion ; Tin Boy and Scarecrow Junior ; the son of the Nome King, and more...

2007's Tin Man

Ah, Tin Man! A cult-classic a lot of people remember fondly - especially on Tumblr. This mini-series was part of the long suite of SyFy "dark sci-fi" fantasy reimaginings (2011's Neverland ; 2009's Alice, etc).

Described as an "adult steampunk reimagining" of the Wizard of Oz, it depicts the adventures of DG, a waitress of Kansas, as she gets taken by an interdimensional storm to the otherwordly "Outer Zone", and there befriends a telepathic leonine humanoid, a man who lost half of his brain, and a former cowboy-like law enforcer of the dictature a wicked witch-queen set upon the Outer Zone...

Speaking of steampunk, the last two Oz adaptations I want to talk about are...

2015's Lost in Oz

This animated show was part of Amazon Prime Video early days at producing its own content. Originally it was just a pilot episode released in 2015. Since the pilot episode proved good, it became a three-episodes mini-series in 2016. Since THIS mini-series proved good, it became a full season in 2017. And since this first season proved good, a second season was released in 2018. And then they stopped.

At first it seems that this show is just an "updated" version of The Wizard of Oz: Dorothy and her dog Toto gets transported to the Land of Oz, and must find a way to get back home while making friends and all together fighting through the many plots and scehmes dividing the land... Except that this Oz is a more modern and updated Oz filled with magi-tech, and Dorothy's companions are not exactly your traditional band... Turns out Dorothy has to team up with Ojo, here depicted as a "giant Munchkin", and a teenage witch by the name of... West. Yes, she is the (not so) wicked witch "of the west".

And thus starts a quite unique retelling of Oz where the three teenagers must face various threats taken from later Oz books: Langwidere, here West's evil aunt ; the mysterious Crooked Magician ; and Roquat, the Nome King.

And a last steampunk Oz for the road: 2018's "The Steam Engines of Oz". This Canadian animated movie is actually an adaptation of an Oz graphic novel of the same name, by Erik Hendrix and about a modernized Oz set after the events of "The Wonderful Wizard". A young mechanician of the Emerald City, Victoria, is chosen by the Good Witch of the North to help fight the ever-growing expansion and industrialization of the Emerald City, pushed by a Tin Man who became a cruel dictator of Oz...

#oz#so you want to know about oz#oz adaptations#land of oz#oz cartoons#oz series#the marvelous land of oz#ozma of oz#the wonderful wizard of oz#tin man#emerald city#the muppets' wizard of oz#the witches of oz#lost in oz#the oz kids

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Dorothy from the books was a better role model for girls than in the MGM Wizard of Oz film?

Just to answer this, I reread The Wonderful Wizard of Oz over the last two days. I'm not very familiar with the rest of the Oz books, but since the movie is only based on the original book, I suppose it's best to compare just the two of them.

I don't think either the book's Dorothy or the MGM film's Dorothy is a better role model than the other. They're just slightly different.

I understand why a lot of people consider Baum's Dorothy a better role model than movie Dorothy. She has more of a down-to-earth, can-do attitude than movie Dorothy, whom some critics think is reduced to a weepy damsel in distress. I especially understand why some people are annoyed by the movie's rewrites to the scenes at the Wicked Witch's castle, where Dorothy's three male friends come to her rescue and where she splashes the Witch with water by accident. In the book the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman are destroyed by the Winged Monkeys, while the Lion is captured along with Dorothy and locked in a pen; Dorothy stands up to the Witch when she tries to take her silver shoes and throws the water on her in anger (not knowing it will melt her, but it's still a deliberate act); and afterwards, she frees the Lion and then rallies the Winkies to repair the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman. I won't deny that the movie's rewrite adheres more to traditional gender roles and probably reflects Hays Code standards of how a "good girl" should behave.

But I don't mind the fact that movie Dorothy is slightly more vulnerable and emotional than Baum's Dorothy. In the first place, she's older than Baum's Dorothy: even if she's younger than Judy Garland's 16 years, she must be at least 12, while Baum's Dorothy might be as young as 6. Between hormones and higher emotional intelligence, it's natural for teenage or preteen girls to be more emotional than little girls. Secondly, movie Dorothy's added soulfulness and dreaminess are part of her appeal. I'm not sure "Over the Rainbow" would seem in character for Baum's no-nonsense little Dorothy to sing.

There's also the fact that the movie's Wicked Witch of the West is much more powerful and dangerous than Baum's Witch. In the book, she can't physically harm Dorothy because the Good Witch of the North's magic kiss protects her, so she just makes her work as a scullery maid. She's also a bit of a scaredy-cat: she's afraid of the Cowardly Lion, and she can't steal the silver shoes at night while Dorothy is sleeping because she's afraid of the dark! With the movie's far more imposing Witch and the real danger Dorothy faces of being killed, it's hard to blame movie Dorothy for being more terrified. She also has more to deal with in Kansas than Baum's Dorothy does: there's no Miss Gulch trying to have Toto killed in the book.

Last but not least, movie Dorothy is still spunky! She still slaps the nose of a lion in Toto's defense (not yet knowing that he's a coward), she stands up to the Wizard even when she thinks he's a fearsome giant head with immense magical powers, and in the Witch's castle, even though her friends free her from the hourglass room, she's still the one who ultimately saves the day. She deserves credit for her presence of mind when she spots the pail of water and throws it onto the Scarecrow to save him from burning, even if it is by accident that she splashes the Witch too.

I think both Dorothys are good characters and role models: Baum's Dorothy for her resilience, optimism, and down-to-earth intelligence, and movie Dorothy for her relatable character arc of longing to escape from her troubles, only to learn that it's not worth the price of leaving her home and her loved ones behind. Not to mention the qualities they both share: warmth, kindness, courage, loyalty, and affection.

#dorothy gale#the wizard of oz#the wonderful wizard of oz#book vs. movie#comparison#fictional characters

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Descendants 4 is baffling

So recently I watched Descendants: Rise of Red and I personally really enjoyed it. Despite what a lot of people say the quality of the sets, outfits, and even wigs has not really changed. Dcoms are always going to be ridiculous and ultimately any judgement towards this movie does not matter because people (myself included) are going to watch Descendants 5 anyway.

Putting that aside this movie is very baffling. Unlike the first three Descendants movies this one isn’t a complete story. Now I’d have to rewatch it to tell you all the plot structure things they missed but I know a significant portion of the mid point and act three are missing most notably the second pinch point.

Now if you have you have no idea what pinch points are they’re essentially the parts of a story that pushes your character towards something.

The first pinch point is pushing a character to run away from something. Ex: Dorothy meeting the wicked witch of the west.

The second pinch point is supposed to push a character towards something. They’ll have to make a lasting decision. Ex: Loki being brought onto The Helicarrier as a prisoner . This will then push them towards the plot turn and then darkest moment (aka when everything falls apart).

We sort of get this when Red decides they have to break into the principals office and Chloe goes to see Ella but I barely see that as a pinch point. One it would be a very short pinch point and two that means there is no darkest moment. You could also say them finding out about the villain’s plan is a pinch point which is much better argument but again it’s very rushed. Also no matter which one of these you argue there would be no darkest moment or plot turn.

It’s just all of it feels so rushed they probably still could’ve had their cliffhanger even if they didn’t rush the third act. All Descendants movies technically have cliffhangers they literally all end almost the exact same way. Even if there wasn’t a cliffhanger people would still come back to watch the 5th one.I don’t understand why Disney couldn’t just make a complete story. They do it all the time.

Also I really wished we could’ve gotten to see the Merlin Academy VKs more. They seem so fun. Honestly all of Merlin Academy seems fun. A spin-off show there would be so cool.

Bridget and Morgie are the best new characters argue with a wall.

#descendants#descendants 4#descendants rise of red#morgie le fay#bridget descendants#red descendants

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lonely, as words go, is a bit of a loner. As the critic Christopher Ricks writes, it pleasingly has “only” one rhyme, and no real synonyms. After all, being alone and being lonely are quite different things. For all this, poets and writers, from Audre Lorde to Philip Larkin, have made much of loneliness, drawn to the challenge of bringing us close to an emotion whose very nature is to stay at a distance.

Some lonely renderings turn out to be a bit of a sham. Records show that when Wordsworth “wandered lonely as a cloud”, his sister Dorothy was strolling companionably beside him, and she liked the daffodils too. Thoreau’s standing as the poster-boy of solitude, living “alone” and “Spartan like” by Walden Pond, starts to unravel when one actually reads his book, which contains a hefty chapter on “Visitors”. (The fact that Thoreau’s mum probably helped out with his laundry has also – maybe unfairly – raised a few eyebrows.)

It is, of course, perfectly possible to feel lonely in the company of others. “Loneliness”, as Olivia Laing writes, “doesn’t necessarily require physical solitude, but rather an absence or paucity of connection”. Her Lonely City is a powerful account of the loneliness explored and expressed by writers ranging from Alfred Hitchcock to Billie Holiday, combined with Laing’s own experience as a “citizen of loneliness”: “I often wished”, she writes, “I could find a way of losing myself altogether until the intensity diminished”.

Loneliness may be a condition that’s tricky to categorise but it is also, in Laing’s words, “difficult to confess”. Indeed, loneliness’s favourite companion seems to be shame. One of the many beauties of Kent Haruf’s small-town love story, Our Souls At Night, is the way in which his heroine breaks this seeming taboo, surprising her neighbour with an unconventional proposal, not of marriage, but of a kind of lo-fi pyjama party. “I’m lonely”, Addie candidly states. “I think you might be too. I wonder if you would come and sleep in the night with me. And talk”.

For some, such as Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant, loneliness is a lived atmosphere, a kind of chronic condition. For others, it comes from a tectonic shift – a sudden loss or bereavement. As Juliet Rosenfeld writes in her memoir, The State of Disbelief, the painful force of her husband’s death made her feel as if she’d been captured by an unseen captor: “I learnt quickly that to protest would make no difference, and choice-less, I submitted to this saboteur with no prospect at all of release or freedom. I believed for a long time that I would never feel differently. I felt a painful absence and loneliness all of the time.”

“We read to know we are not alone”, as C S Lewis famously didn’t say (the line belongs to his on-screen persona in Shadowlands). So it is a sad irony that books which might best provide company nearly didn’t see the light of day. Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness was banned, after its first publication, for more than 30 years, accused of promoting “unnatural practices between women”. Because of that judgment, many readers missed an encounter with the beauty of the novel’s prose, its tender account of the heroine as she reflects on her childhood home. She dreams of “the scent of damp rushes growing by water; the kind, slightly milky odour of cattle; the smell of dried rose-leaves and orris-root and violets”, and knew “what it was to feel terribly lonely, like a soul that wakes up to find itself wandering, unwanted, between the spheres”.

This sense of loneliness as a kind of between-ness, an uncharted territory, is movingly captured in Sam Selvon’s 1956 novel, The Lonely Londoners. This Windrush chronicle charts the trials of those arriving at Waterloo from the West Indies, as they struggle to navigate the “unrealness” of London. Selvon’s hero, Moses Aloetta, becomes, over time, the reluctant guide to this latter-day Waste Land. Selvon leaves us with Moses’s lyrical and allusive understanding of the city’s “great aimlessness”. Standing on the banks of the Thames, he conjures a vision of a world in which we are all, in the end, alone together:

As if … on the surface, things don’t look so bad, but when you go down a little, you bounce up a kind of misery and pathos and a frightening – what? He don’t know the right word, but he have the right feeling in his heart. As if the boys laughing, but they only laughing because they ’fraid to cry.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is a list of 50 of my current all time theatre dream roles (musicals and non-musicals) because I am a female acting major who is having trouble in believing my dreams for my future are attainable at this current moment:

1. Christine Daaé - Phantom of the Opera

2. Emily Webb - Our Town

3. Belle - Beauty and the Beast

4. Katherine Plumber - Newsies the Musical

5. Elizabeth Bennet - Pride and Prejudice

6. Veronica Sawyer - Heathers the Musical

7. Maria - The Sound of Music/or/West Side Story

8. Hodel - Fiddler on the Roof

9. Zazzalil - Firebringer

10. Eliza - Hamilton

11. Laurie Williams - Oklahoma

12. Cinderella - Into the Woods/or/Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella

13. Narrator - Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat

14. Princess Anna - Frozen the Musical

15. Hermia - A Midsummer Nights Dream

16. Elphaba - Wicked

17. Glinda - Wicked

18. Éponine - Les Misérables

19. Winnifred the Woebegone - Once Upon A Mattress

20. Miss Honey - Matilda the Musical

21. Ariel Moore - Footloose the Musical

22. Dorothy Gale - The Wizard of Oz

23. Lucy van Pelt - You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown

24. Princess Fiona - Shrek the Musical

25. Viola - Twelve Night

26. Hermione Granger - A Very Potter Musical Trilogy

27. Ginny Weasley - A Very Potter Musical

28. Eliza Doolittle - My Fair Lady

29. Leading Player - Pippin

30. Natalie Haller - All Shook Up

31. Miss Saundra - All Shook Up

32. Cosette - Les Misérables

33. Princess Ariel - The Little Mermaid the Musical

34. Eva Peron - Evita

35. Maureen Johnson - RENT

36. Mary - It’s A Wonderful Life

37. Sue Snell - Carrie the Musical

38. Truly Scrumptious - Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

39. Johanna Barker - Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street

40. Molly Aster - Peter and the Starcatcher

41. Gertrude Fail - Failure: A Love Story

42. Brooke Ashton - Noises Off

43. Megara - Hercules the Musical

44. Mary Poppins - Mary Poppins

45. Nora Helmer - A Dolls House

46. Queen Elsa - Frozen the Musical

47. Charity Hope Valentine - Sweet Charity

48. Fanny Brice - Funny Girl

49. Anya - Anastasia

50. Jane - Tarzan

There’s probably even some that I forgot to put on this list that should probably be in the place of some of these other roles, but I did want to incorporate roles from non-musicals as well. I do acknowledge that this list is still very much mostly musicals, but I fear I have not read many straight plays. Also, most of the work I’ve already done is musical theatre. Which is why I’m an acting major. I want to be exposed to more pieces of theatre that don’t have singing and dancing. There are a bunch of shows that I would love to be in, but don’t necessarily have dream roles solely because they are either ensemble heavy productions or they would just be really fun projects to work on. For example, my school, Illinois State University, just did Bonnie and Clyde the Musical. That shit was GUT WRENCHING. I would have loved to be apart of that project. I don’t exactly have a dream role in that show because every role in Bonnie and Clyde is so essential to telling that story. I am however, working on my first MainStage production here at ISU. I am playing the Nurse in Equus. Again, not a show that I had any dream role going into being cast in this project. But, this story is very heavy and unique. I have never worked on a show as different and dramatic as this one. I am really excited to be part of this cast, and I will be happy to post information about this show in the weeks to come, or you can message me and ask for more details! Thanks for reading my extra long blog post for today! :)

#theatre kid#musical theatre#theatre#dream roles#dream role#i will go down with this ship#equus#bonnie and clyde#beauty and the beast#heathers#illinois#phantom of the opera#our town#shrek the musical#oklahoma#acting#acting major#theatre major#college life#theatre school#i love them#sweet charity#west side story#the sound of music#funny girl#chitty chitty bang bang#avpm#avps#avpsy#shakespeare

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

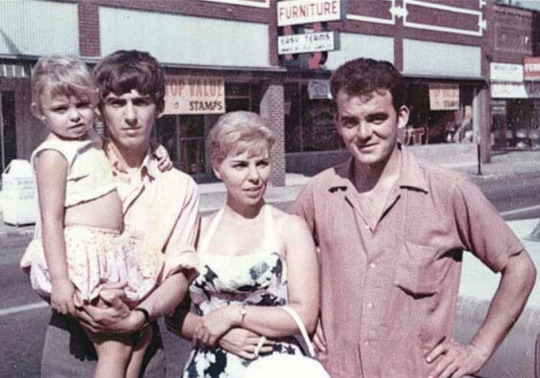

This is a photo and related article my grandfather sent me by Email, I hope you guys enjoy

It Happened In The 60s

Before Beatlemania set in, George Harrison visited his sister in Illinois on 16 September 1963, becoming the first Beatle on American soil.

Beatle John has the story:

“When a young man with long dark hair and a thick British accent first told Dorothy Burkitt, a chaperone at the old West Frankfort Teen Town, that he played in a band called the Beatles, she laughed. ‘Why would you name a band after an insect?’ she asked. But other than that she didn’t give it much thought.

At the time, Burkitt and her husband, Fred, were both chaperones at the teen town, which was located above Van-Wood Electric in a two-story building on West Main Street. It was there that she had her brief encounter with George Harrison, although she doubted much of what he said. ‘He was so sweet,’ she recalls. ‘We must have talked for a good hour, but I’m sorry I didn’t even shake his hand.’ Burkitt said George told her he was visiting over here from England with his sister, and he came to the teen town to see the band and hear its vocalists. She remembers him sitting on an old red couch in the lobby.

The next time Burkitt saw George Harrison, he was on ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’ several months later. ‘Oh, my gosh, Fred, there’s that kid that came to our teen town,’ she said. ‘He was telling the truth.’”

- Before He Was Fab: George Harrison’s First American Visit (2000)

Additional background from George:

According to George, “I went to New York and St Louis in 1963, to look around, and to the countryside in Illinois, where my sister was living at the time. I went to record stores. I bought Booker T and the MGs’ first album, Green Onions, and I bought some Bobby Bland, all kind of things.” George also bought James Ray’s single “Got My Mind Set On You” that he later covered in 1987.

When the Harrisons arrived in Benton, George and Louise hitchhiked to radio station WFRX-AM in West Frankfort, Illinois taking a copy of “She Loves You” which had been released 3 weeks earlier in Britain and on the day of George’s arrival in America. “She Loves You” got a positive review in Billboard but very little radio play, although WFRX did play it. According to DJ Marcia Raubach: “He was unusual looking, he dressed differently than the guys here. He was very soft-spoken and polite.”

It’s often claimed that in June 1963 Louise took a British copy of “From Me To You” to WFRX that she had been sent by her mother and that Raubach played it. This is probably true but the claim that this was the first time The Beatles’ music was broadcast in America is not. “From Me To You” was released in Britain in late April and then topped the British singles’ chart for seven weeks’. With the Beatles at No. 1 in Britain, Vee Jay Records released their single of ‘From Me To You’ / ‘Thank You Girl” as VJ 522 on May 27, 1963. The single was made ‘Pick Of the Week’ by Cash Box magazine, but was not a success.

With the Beatles success in Britain in early 1963, Parlophone were anxious to take advantage of their new asset and so contacted their sister label in America, Capitol Records that was owned by EMI. Capitol was underwhelmed by the Beatles records and so decided against releasing any of their records. Instead, Parlophone turned to a small US label called Vee Jay, a company started by a husband and wife in Gary, Indiana that specialized in black R & B music.

It was an irony probably not lost on the Beatles who loved and had been influenced by exactly that kind of music. In February 1963, two days after “Please Please Me” made No. 1 in Britain, Vee Jay released it as a single in the US. VJ 498 did get some airplay from the major Chicago top 40 radio station WLS and it even made their own chart for a couple of weeks, but nothing happened nationally on the Billboard charts. Not helping the band was the fact that Vee Jay managed to miss-spell the band’s name on the record as “Beattles.”

Article thanks to Richie Havers at www.udiscovermusic.com

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wizard of Oz Word Crawl

By: streetcarnamedmaddie

Hello fellow WriMos! My favorite movie of all time has always been The Wizard of Oz. I even have the entire movie memorized! I often have it on while writing as background noise, so I decided to come up with this Wizard of Oz word crawl inspired by a previous year’s Harry Potter word crawl. This challenge borders on intense, so feel free to skip any rounds if you need. I hope you enjoy!

Uh oh! Toto got into Ms. Gulch’s garden again! Complete a five minute sprint as you run home to tell Aunt Em.

Somewhere over the rainbow is your next milestone. Write to the next thousand as you contemplate life outside of Kansas.

You have to get away…you have to run away! Sprint for three minutes to escape the wrath of Ms. Gulch.

You stumble upon a wagon advertising Professor Marvel, a fortune teller esteemed by the crowned heads of Europe. Roll a six-sided die and multiply the number by 100 to determine your next total as he reads your fortune in his crystal.

It’s a twister! It’s a twister! Complete a fifty headed hydra as your house is whirled around by the tornado.

We must not be in November anymore… You’ve ended up in a strange and colorful land you’ve never seen before. Write 250 words as you explore your new surroundings.

We welcome you to Munchkinland! You are the national hero (or heroine) of Munchkinland. As they celebrate the death of the witch who has tormented them, write for ten minutes .

I’m afraid you’ve made rather a bad enemy of the Wicked Witch of the West. The sooner you write 500 words , the safer you’ll sleep.

Follow the yellow brick road to the next thousand!

Now which way do we go? Roll a six-sided die and multiply the number by 100 to determine your next total as you decide which way to go.

Some people without brains do an awful lot of talking—and writing. To prove it, write to the next thousand.

Why, it’s a man! A man made out of tin! Write 3% of your word count as you oil him up.

Here, Scarecrow, wanna play ball? Help the scarecrow put the fire out by completing a fifty headed hydra.

Lions and tigers and bears…oh my! Show you aren’t afraid of them and write 500 words.

Poppies will put them to sleep. Complete a word war to wake up your friends. If you win, move onto the next challenge. If you lose, write until you beat the other person’s total.

Your friends woke up and now Emerald City is closer and prettier than ever! Sprint for five minutes as you get out of the woods and step into the sun and into the light.

Take a ride with a horse of a different color through the Emerald City by—you guessed it— completing a fifty headed hydra.

Surrender, Dorothy—it’s time for another word war! If you win, move onto the next challenge. If you lose, add 100 more words before continuing.

Imagine what it would be like if you were King of the Forest and write 500 words.

The Wizard will see you now, though he doesn’t have much time. Write 100 words as you explain your wish.

I’d turn back if I were you… Complete a three digit challenge as you fend off the spooks in the forest.

I’m frightened, Auntie Em, I’m frightened…because you have to write 1000 words for this challenge.

I’ve got a plan how to get into the castle of the Wicked Witch: roll a six-sided die . If it is even, you only need to write 100 words. If it is odd, multiply your roll by 100 and write that many words.

Going so soon? Why, our little party’s just beginning! As you race to get out of the castle, sprint to the nearest thousand.

Ding, dong, the witch is dead (is that the right song?!). Celebrate your accomplishment by writing for five minutes .

The Wizard is a very good man, but a very bad wizard. Fortunately, he has gifts! Write three paragraphs as your friends get their wishes granted.

Oh, no! The Wizard’s balloon has left without you! Now how will you get home? As you ponder this, write 250 words .

It’s time to say goodbye, and I think I’ll miss you most of all. Write for five minutes as you bid your friends farewell.

Tap your heels together three times and complete a three digit challenge as you think to yourself: there’s no place like home…

Wake up. It’s Aunt Em, darling. Write to the nearest thousand because there’s no place like home.

0 notes

Text

160,000 and that's really a teeny bit of money and back then they were not charging huge amounts of interest because the banks were not giving people that much money and interest they put it in there so someone couldn't steal it and you're kind of paying for a service. That's how it was for a long time yet up to the old West and after that things changed a little and people started investing in big projects and developed the United States from anew and they needed a lot of money. It helps to know history. He understands it pretty quick and he knows about the finances and how it works but we know what happened. With that said and he's been paid the whole time and his grandma dot or Dorothy she was paying him $25 a year and Jim was having her do it. And she is actually Queen Elizabeth the second is not true it was not his real wife and she was a woman and she was a Mac proper so she didn't like our son that much they got the fights and he said she's saying you two go outside you animals but still they were acting that way so they didn't care one day she said that he's a dirty little boy and says bad things to people. And she has told you to wait till lunch to eat and you said I can't wait i'm hungry and she said you have to and she cooked this huge dinner and he's sitting there hungry the whole time and she's not aware of his situation so he said I'm a baby size wise and she says when is he talking about looked into it and said he's probably in pain and she had you a little snacks later no she said suck it up and it wasn't right. And she died and went into a grave and was held there and it's actually gone. So people are angry about that on the Mac side and our son is not too angry about the meals because he learned to look forward to the meal and wait for it instead of ruining it with snack foods and have three squared a she's smiling and said you're right you can learn it's a fairly well I'm your size at least she started laughing and said it's not that bad i'm stunted for some reason and so she goes around and she says he's a baby and that would explain the she felt better because it was kind of embarrassing you're firing and burping and farting. Said believe me if I could stop I would I get stories now and she smiles and says terrific. And I'm reading them and usually it makes the story really famous and she tried to print and a few people wanted it and she did. She felt pretty good and she was really huge so and she left really liking her grandson and she heard it she heard she was sick and he wanted to go see her and she couldn't get out of there and he called home and they wouldn't get him up there and she said tell him I miss him and he was crying and she's staying be a big boy and he said you need a way out so I've had enough of this crap don't you want to see me when I'm huge so she tried a few things and said Jim this stuff you need to know and it really is. So she didn't get out and Jim couldn't do it. We're talking about what he was doing back then a little bit. But he's lost a lot of people and their friends too. Bob Marr said it he doesn't know if I'm a mac and doesn't really check and says we're human beings too if I were one. He says I can do the fake wrestling thing and he says we don't have to throw anybody down or fall over and they'll punching and Bob Marsh used to jump in front and say okay so we're just going to slap and says that's what it is but not like they do in the slap contest. This is what like a couple gay boys I said no. Maybe what we're doing like if you took it and you animated it and truck us both down to look like the guys from AEW AEW yes. So now he's laughing pretty good. Probably put you back in the circu

Thor Freya

Olympus

Zues Hera

0 notes

Note

What do you think about the people who insist in treating Wicked as some sort of official prequel to MGM's Wizard of Oz?

Like, I know both the musical and the Maguire book are heavily inspired by the 1939 movie instead of the L Frank Baum's book, but both of these contain so much divergent points to the movie that it's impossible for them to be in the same continuity.

The most obvious evidence being how in the musical there's a scene of the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion leading an angry mob, in true Beauty and the Beast fashion, to the castle to kill Elphaba and rescue Dorothy, when in the movie they along with the Scarecrow invaded the castle completely on their own.

Also, the musical glosses over the Wicked Witch of the West's oppression of the Winkies.

I talked about this before: this annoys me, deeply, but honestly? It is just a case of misinformation and kids being kids. Literaly.

Because I want to separate two cases, both easy to find on the Internet. On one side you have people who love Wicked (it can be the musical, it can be the novel, it can be both or just one while they hate the other with all their heart), and so decide to include it in their own perception and imaginings of Oz. And there's nothing wrong with that. People have been adding the MGM elements to the world created by the Baum books for a long time, and Wicked is the next popular thing ; same way there's nothing wrong with people taking elements from Return to Oz or any other popular Oz adaptations to mix with their personal retellings and imagination! (As long as it stays non-commercial, you know? Because that's the important thing - Wicked, the MGM movie, Return to Oz and all that are NOT in public domain, unlike Baum's novels. Oz is in public domain, but the Oz ADAPTATIONS are not, and that's another confusion people seem to not really get)

That being said, it is just one of the two cases. The other case is people who LITERALY consider that Wicked (the novel, and the musical derived from it) is MEANT to be the "official" prequel to The Wizard of Oz. We are talking people who sincerely designate the novel as "canon" somehow. And... I know they exist, I have seen them post and write comments online. But I literaly cannot understand their way of thinking, and the only explanation I can give to this is that they must be ignorant people, in the literal sense: they did not do their research, they have such secondary-source exposition to things they actually miss the most basic and crucial parts of each work, and so they come to believe not only that the MGM movie was its own thing, the movie that started it all, the "OG" version of the story (so no Baum involved), but that somehow Maguire got the legal rights and authority to write an officiel prequel novel for the movie? While missing the fact Maguire was literaly doing a parody/deconstruction/twist on the movie, and doing that PRETTY HEAVILY...

My other guess is that this is mostly children. Not just because children infest the Internet today, but also - having been a child myself - I know that kids often take at face value the way things are described to them, they are very first-degree minds. And when you see on the Internet people talk of a book that is the "true life" of the Wicked Witch of the West, the "real chronicles" of the Land of Oz, that is about "what truly happened" in Oz... First-degree mind of kids (especially if the kid doesn't have the novel and just Wikipedia recaps) will go: "Oh yeah, that's the official prequel, and that's like the real biography of the character!"

A similar phenomenon happened with the release of the "Maleficent" movie and how a lot of people decide to consider the backstory of Maleficent in this movie the "official" backstory of Maleficent in the original animated movie - entirely missing the fact the Maleficent movie is an inversion, or a reversal, of the original movie, and the two are not part of the same continuity...

On another side, it is quite amusing to see that Disney TRIED so hard to create the same "official backstory" phenomenon with "Oz The Great and Powerful", and yet failed so hard because nobody ever goes "Yes, Theodora IS the real name of the Wicked Witch of the West".

I guess there's also something to be said about how Elphaba forms a very compelling anti-hero, and as a result people are more likely to use this tragic backstory as a material when fleshing out the Wicked Witch, because so far it is the most complex depiction of the character we had? I don't know... But the whole thing of "Should the Witches be complex or simple characters, should they be explained or stay mysterious" is yet another debate...

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

5/2/24 - DOROTHY L. SAYERS

' "Harlequin!" ' (Sayers, 2023, p.213).

…

' "You might kiss me, Harlequin." '(Sayers, 2023, p.172).

…

' "Take me home, Harlequin - I adore you!" ' (Sayers, 2023, p.79).

…

REFERENCE

Sayers, D.L. (2023 [1933] ) 'Murder must advertise’. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

*****

SEE ALSO

' "I think I'll give up dope ... I'm getting puffy under the eyes." ' (Sayers, 2023, p.209).

…

*****

FOR MY HUSBAND

WHO WOULD HAVE ENJOYED THIS ONE

…

XXXX

LOOKING GOOD

*****

ALSO FOR BOOK GROUP 2024

20 (90) GLORIOUS YEARS

…

‘ “My brother, being an English gentleman, possesses a library in all his houses, though he never opens a book.” ‘ (Sayers, 2023, p.215).

IN JANUARY OUR MEMBERS ALSO READ …

WE HAVE TWO TOP READERS

TOP READER (LEADER) 1

…

MILKMAN

‘This is a brilliant and important book set in the time of the “troubles” in Belfast. One of those books which you know are clever but you don’t actually enjoy. It is written in a strange style, which I found difficult but I stuck to it grimly and finished it.’

&

…

LESS THAN ANGELS

‘ … also read … ‘

&

…

THE MURDER AT THE VICARAGE

‘ … still reading … ‘

&

…

ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE

‘ … still reading … ‘

😇📚

TOP READER 2

…

WHERE THE CRAWDADS SING

‘I was lent this at Christmas with not much of a recommendation so I didn't know what to expect and I thought it was amazing. It is so descriptive of the unusual surroundings that the main character lives in, a curious marshland area.’

&

…

RACHEL’S HOLIDAY

‘ … about a young woman who agrees to go to a "Health Farm" to be helped with her drug addiction, paid for by her family. She agrees, expecting it to be very glamorous and full of media stars, but it is run down and scruffy. The book is quite readable and touching in places as inmates have to talk about their troubles and get sensible counselling.’

&

…

THE MIDWIFE MURDERS

‘ … a thriller with lost babies and dodgy obstetricians as its main characters, readable but nothing special.’

&

…

THE GOLDFINCH

‘An amazing book. I won't describe it to you as it covers so many different subjects and emotions and I expect you've all read it. I got a bit bogged down with about the last quarter of the book when it concentrates on criminal gangs bargaining stolen paintings.’

😇📚

OTHER MEMBERS HAVE READ

…

BURNING ROSES

‘I love these books, historically accurate and a great story woven round the facts.’

&

…

GROWN UPS

‘An enjoyable book but not one of her best.’

&

…

THE INK BLACK HEART

‘ … again quite an enjoyable book but not one of her best.’

📚

…

BLEEDING HEART YARD

‘ … routine detective story. Easy read, I wanted to check out this author as our daughter in law asked for a forensic detective novel for Christmas. This one wasn't forensic but one of her other characters is a pathologist.’

&

…

THE BULLET THAT MISSED

‘ … light hearted and tongue in cheek, mature detectives on the loose.’

&

…

THE TWIST OF A KNIFE

‘ … set in a West End theatre where Horowitz plays himself as the playwight. A Christmas present and very enjoyable.’

MEANWHILE THE OTHER HALF

…

ACT OF OBLIVION

‘ … which he is enjoying. Another Christmas present … must have read something else!’

📚

…

WHOSE BODY?

‘The first Lord Peter Wimsey.’

📚

…

BOOK GROUP

*****

QUOTE OF THE WEEK 2011 - 2024

…

12 EPIC YEARS

FROM THE ARCHIVE

…

31/7/23

*****

0 notes

Text

Hidden Figures

Hidden Figures

Unedited Thoughts - This is part of my unedited thoughts series. Based on true events - this never bodes well. We meet Katherine as a child and we immediately know that she is gifted. The way that the community rally around her and her parents is fantastic. There is a great film making moment setup here when her teacher asks her to solve the complex problem on the board she takes the chalk that is handed to her and solves it. This is referenced in a later scene when she is at a department of defence briefing and the exact same thing happens and she blows them all out of the water with her brilliance. The first scene that we meet three ladies when they are grown up is great. Their car is broken down on the way to work at Langley and a white cop stops. We know there is going to be trouble and from this one scene we learn the state of play - race relations and the sexism that the three leads will face. We also get to meet the three ladies forceful nature and the different ways it manifests itself as they get this police officer to escort them to work. Truly great script writing. The use of the African American ladies as 'computers' feels demeaning at first. But there is a lot going on here. First, computers isn't necessarily the derogatory term that it sounds like. Second these are relatively good positions for such talented ladies. Also looking back now at the term it has a powerful ring to it. You were so good at math you are called a computer. The polish engineer who is working on the re-entry vehicle is a great counter point to Mary who is encouraged to become an engineer by him. He makes the point about escaping Nazi Germany and launching people into space - if he can do that what can she do? Then our heroine, Katherine, is placed in the Space Team headed by Al Harrison, Kevin Costner. She spends much of her time trying to fight against the ridiculous restrictions placed on her. One of the mathematicians redacts all of his reports so that it is almost impossible for Katherine to check his work - but she finds a way. The racist oppression is something else - They don't want her drinking out of their coffee percolator so get a crappy one installed - etc etc. By far the worst is that there is no bathroom for Katherine in this section of Langley so she has to treck across the base to the west side to the coloured bathroom. While this is powerful the first time - and frustrating the second. The third time is just ridiculous. Her boss blows up at her the last time that this happens - And she lets loose back. He had no idea that there were no bathrooms and about how she was been treated. After storms out of the room he paces over to the coffee cart and dumbfoundedly pulls the 'coloured' label off the percolator. This was a powerful scene and the tension in the room was palpable. Yet the very next scene destroys it all. Harrison is taking a sledge hammer to the 'coloured' bathroom sign in the Western section - which is the bathroom that Katherine has been travelling to this entire time. The signs he should have been removing were the 'white's only' in his building. I cannot believe that this got missed as it feels like a mistake - but it's there so I have to rate the film on it. The undertone of sexism in the black community feels a bit shoehorned in for me. At the church picnic right at the start both Mary's partner and Katherine's would-be husband make a big deal over what women can and can't do. Then nothing really at all. You can't try to force further 'ism' discussion and then leave it dead. There are some truly terrible lines in this film. "We all pee the same colour" is up there. There are some fantastic moments as well. Dorothy's character has been trying to negotiate a supervisor position for herself and when the IBM arrived - protect her girls jobs. She does both by teaching herself fortran. This culminates in a great scene of her leading the entire group over to the new computer room. When Jim finally proposes to Katherine the reaction of her and the kids is actually really touching - "Why are you crying? He hasn't asked you yet." To which Katherine responds - "He will." Turns to Jim "Won't you?!?". It has a realness about it that is just fantastic. Then after Katherine has saved them all - many many times - they fire her - because the IBM is much faster. Then, just as they are about to launch Harrison recognises that the numbers are off. He confers with Stafford - Katherine's co-worker - who agrees. The big flop for me here is that neither of them recognise that they need her to check the numbers. The call for her comes from Glen - the man they are about to launch. This is fine as they set him up from the moment he comes on screen as been progressive - he ignores the rules when they arrive at Langley to meet the African American ladies. So it makes sense for him to request this - especially after her display at the Department of Defence briefing. It's just sad that it isn't Harrison or Stafford who make the call. Katherine's checking the figures is another brilliant scene as she calculates the landing zone and the telecast of the launch is happening on the TV in front of her. Overall a fun movie but just a bit too Disney. Some nice scenes but also some poor ones. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Out of Kansas: Revisiting The Wizard of Oz by Salman Rushdie

New York Magazine - May 4, 1992

Photograph from Everett

I wrote my first story in Bombay at the age of ten; its title was “Over the Rainbow.” It amounted to a dozen or so pages, dutifully typed up by my father’s secretary on flimsy paper, and eventually it was lost somewhere on my family’s mazy journeyings between India, England, and Pakistan. Shortly before my father’s death, in 1987, he claimed to have found a copy moldering in an old file, but, despite my pleadings, he never produced it, and nobody else ever laid eyes on the thing. I’ve often wondered about this incident. Maybe he didn’t really find the story, in which case he had succumbed to the lure of fantasy, and this was the last of the many fairy tales he told me; or else he did find it, and hugged it to himself as a talisman and a reminder of simpler times, thinking of it as his treasure, not mine—his pot of nostalgic parental gold.

I don’t remember much about the story. It was about a ten-year-old Bombay boy who one day happens upon a rainbow’s beginning, a place as elusive as any pot-of-gold end zone, and as rich in promises. The rainbow is broad, as wide as the sidewalk, and is constructed like a grand staircase. The boy, naturally, begins to climb. I have forgotten almost everything about his adventures, except for an encounter with a talking pianola, whose personality is an improbable hybrid of Judy Garland, Elvis Presley, and the “playback singers” of Hindi movies, many of which made “The Wizard of Oz” look like kitchen-sink realism. My bad memory—what my mother would call a “forgettery”—is probably just as well. I remember what matters. I remember that “The Wizard of Oz”—the film, not the book, which I didn’t read as a child—was my very first literary influence. More than that: I remember that when the possibility of my going to school in England was mentioned it felt as exciting as any voyage beyond the rainbow. It may be hard to believe, but England seemed as wonderful a prospect as Oz.