#i like philosophy get me philosophy anthologies i like linguistics get me books on linguistics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

it’s that time of year again, and i get so annoyed when my family is like “oh you’re so hard to get gifts for” and i’m just like. i’m literally not. i am so loud and open about my interests, the quickest of google searches will turn up dozens of little knickknacks i’d love. i’m not hard to get gifts for, you’re just not listening to me.

#if you don’t want to get me fandom stuff get me notebooks! or nice pens! or jewelry!#literally it doesn’t have to be expensive#one of the best gifts i ever got was a cheap pair of garnet earrings#i like philosophy get me philosophy anthologies i like linguistics get me books on linguistics#even pop linguistics is fun for me!#i’m so easy to please i really am#maybe i don’t seem happy when i get the same lotion set for the 10th year in a row (i don’t wear lotion bc sensory issues)#maybe i don’t seem happy when i get unnecessarily expensive clothing that someone in their 60s would wear#or with little hallmark toys that have nothing to do with me or my interests#but it’s because im so open about what i do like and all of that just seems so last minute like something you’d give a coworker#i don’t like sending just like a list either. because doesn’t that defeat the purpose?#if you’re just going to get me exactly what i say off a list i’d rather you just not get me anything it feels so disingenuine#personal

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I Read in 2021

#54 - The Prince and Other Writings, by Niccolo Machiavelli, translated by Wayne A. Rebhorn

Mount TBR: 51/100

Beat the Backlist Bingo: An anthology

Rating: 2/5 stars

In this case, I want to make it clear that my rating is not a reflection of how "good" the book was, but how much I got out of it. I'm not trying to trash a classic of philosophy and political thought. But I also don't read much about philosophy or political thought, and this work reminded me why.

It's dry as hell.

I admit to skimming, past a certain point, because especially in "The Prince," which leads the collection, Machiavelli follows an incredibly clear formula: open a chapter with his thesis statement, explain it a little in generalities, mention a few applicable real-world examples, and then go in-depth on one or more of those examples, before summing his point up at the end. I was able to skip most of the in-depth assessments, because they were basically meaningless to me, as I am not a student of Italian history and had no idea who most of the figures he mentioned were. Some of them continue to loom large in historical perspective today, but many don't.

What did I actually take away from this? Well, mostly, a rebuttal of the reason I read it in the first place. This is well outside my comfort zone, but I've been hearing the descriptor "Machiavellian" thrown around idly for years, and like many, I'd come to understand that it meant cruel or even flat-out evil. I thought, if this is such a foundational work that the author gets his own adjective, I should probably read it at some point, yes?

But I didn't get a sense of cruelty or evil from his philosophizing at all. Sure, he's definitely espousing "the ends justify the means" as an overall theme, and he advises duplicity in leaders, to project an image of what he considers "good" while sometimes doing bad behind the scenes in order to promote stability. So from a broadly modern perspective, he's less than perfectly moral. But he does spend a chapter pointing out that acquiring power through criminal activities isn't a strong foundation for power. And I discovered that the famous "better to be feared than loved" tidbit is a misquote.

He's not evil, or promoting evil. He's just a realist and a pragmatist, from a time in history and political structure incredibly different from ours. No, I personally don't agree with the idea that the only way for a prince to be a strong leader is to have a kick-ass military. But in context, I do understand why Machiavelli thought that, and advised his own patron thus. I don't think most of this is applicable to modern day life, but it's still useful to understand how Machiavelli changed political thought with his writing.

So I'm glad I read it, even if I didn't really enjoy it. I'm glad I have a more accurate understanding (even if it's still a basic one, because politics is Not My Thing) of what this famous person really said, versus what common knowledge claims he said. And while I don't think I was ever using it that much, I'm going to stop throwing around the term "Machiavellian," because it doesn't mean what I thought it meant, but I alone can't stop the tide of people using it incorrectly. (Or, if you want to be really pedantic, using it correctly because that's what the term has come to mean, even if that meaning is now divorced from its source. Because I can't in good descriptive faith argue that "Machiavellian" doesn't carry connotations of evil and cruelty--it does. What I am arguing is that it shouldn't, but that's not a fight linguistics will ever win.)

#booklr#book review#the prince#machiavelli#bibliophile#my photos#my reading challenges#mount tbr 2021#beat the backlist 2021

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Readerly Exploration 1.25.21

Advanced Readers in Reading First Classrooms: Who Was Really “Left Behind”? Considerations for the Field of Gifted Education

Big Take-Away

To record the progress of advanced readers over a span of 3 years in comparison to their non-advanced peers and how the Reading First classroom tended to their reading needs.

Nugget

In an attempt to determine how the needs of advanced readers were met in RF class-rooms, it is necessary to examine the research concerning the attributes of advanced readers. This is a difficult task due to the fact that reading researchers cannot come to a consensus on the definition of precocious, advanced, gifted, or fluent readers (Olson et al., 2006; Reis et al., 2004).

This explanation revealed the reading coach’s misunderstanding about the philosophy of differentiated instruction, including the erroneous belief that higher level thinking skills are reserved only for those students who are identified as advanced.

If the goal of gifted education is to develop critical and creative thinkers who are able to reason, problem solve, and critically analyze potential answers for their degree of fit, these students should be given opportunities to do so in the context of learning.

heterogeneity: the quality or state of being diverse in character or content.

precocious: (of a child) having developed certain abilities or proclivities at an earlier age than usual.

advanced: far on or ahead in development or progress.

gifted: intellectual ability significantly higher than average.

fluent readers: read in phrases and add intonation appropriately.

anthology-style: a published collection of poems or other pieces of writing.

supplementary books: a little something extra to fill in a gap, like when your teacher suggests supplementary reading material that you may or may not get around to checking out. Supplementary can be an important part of something or just extra support.

fidelity: faithfulness to a person, cause, or belief, demonstrated by continuing loyalty and support. OR the degree of exactness with which something is copied or reproduced.

Covariates: characteristics (excluding the actual treatment) of the participants in an experiment. If you collect data on characteristics before you run an experiment, you could use that data to see how your treatment affects different groups or populations. Or, you could use that data to control for the influence of any covariate. Covariates may affect the outcome in a study.

data corpus: A collection of linguistic data, either compiled as written texts or as a transcription of recorded speech. The main purpose of a corpus is to verify a hypothesis about language - for example, to determine how the usage of a particular sound, word, or syntactic construction varies.

trepidation: a feeling of fear or agitation about something that may happen.

clandestine: kept secret or done secretively, especially because illicit.

formidable: causing fear, apprehension, or dread: OR of discouraging or awesome strength, size, difficulty, etc.; intimidating: OR arousing feelings of awe or admiration because of grandeur, strength, etc. OR of great strength; forceful; powerful:

Engage in the reading process to increase the likelihood of text comprehension (pre-reading, reading, responding, exploring, applying):

Before you read, skim the assigned course reading(s) for unfamiliar terms. Then, take the time to look up the definitions of those terms.

I typically have a hard time reading case studies such as this one, so I already had expectations that I would have to look up many unfamiliar terms before I even started. This thought alone gave me insight into what kind of expectations my students will bring into assignments before they attempt them. Whether those are positive or negative expectations, they both have an impact on student motivation. To my surprise, skimming the article beforehand increased my confidence when I recognized I didn’t need to look up as many words as I thought. Surely, a 37 page document would have more than a few unfamiliar terms if it was beyond my comprehension. Looking up the terms beforehand, helped me anticipate what kind of ideas I would be encountering within the text. It was especially helpful when I realized that a word I had looked up, appeared many times throughout the article. I thought the rule with vocabulary in a text was, if you don’t have to look up that many terms, then you should be able to understand the text with ease; interestingly enough, that was not the case for me. Although, I knew most of the words I was reading, it didn’t mean that I would be able to understand the text any easier than I had initially anticipated. I am assuming the format in which this information is given is probably the deciding factor in how well I retain the information I am reading. This was an interesting concept, as my students will also be faced with text that does not necessarily seem out of their reach, but it could very well be the type of text that they’re reading that hinders their comprehension.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coming and Going: Misrecognition and Identity in Flannery O’Connor’s “Everything That Rises Must Converge”

Professor Richard A. Garner The Human Situation, April 15th, 2020

Outline

I. The Best Title in All of Literature

II. Misery Like a Coastal Shelf

III. The Injury of Intelligence, the Insult of an Education

A. Intelligence is a curse

B. A Martyr to the Desire of the Other; or, that St. Sebastian Painting One More Time

C. The Terror of Identity; or, Meeting Yourself Coming and Going

Richard Sexton,Oak Avenue, Wormsloe Plantation, 2009

I. The Best Title in All of Literature

“The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

—William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

In a second, I’m going to talk to you about the literary genre called the Southern Gothic. It’s the best. It’s weird and uncanny and disturbing, and it’s all ours. After that, I’m going to talk about the cursed intellectuals of O’Connor’s stories in general, and more specifically of our story for today, “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (1961). You might want to read the last one first, as it does the most close-reading, or the second one, which has lots of maps and stuff. But first, I want to tell you that “Everything That Rises Must Converge” is the best title in all of literature.

From the moment I read it on the syllabus as an undergraduate—circa the turn of the millennium— it took on a life of its own in my head. It’s one of those phrases we encounter in life that returns over and over again, coming to mind unbidden in situations that have nothing remotely to do with the themes of the story. Indeed, every time I go back and reread the story I am struck by how the title, like many of O’Connors, creates this tiny bit of cognitive dissonance, this strangeness that makes it at once both absolutely perfect and deeply unsettling: a stark line of poetry that stands over and above the story, its own little work of art.

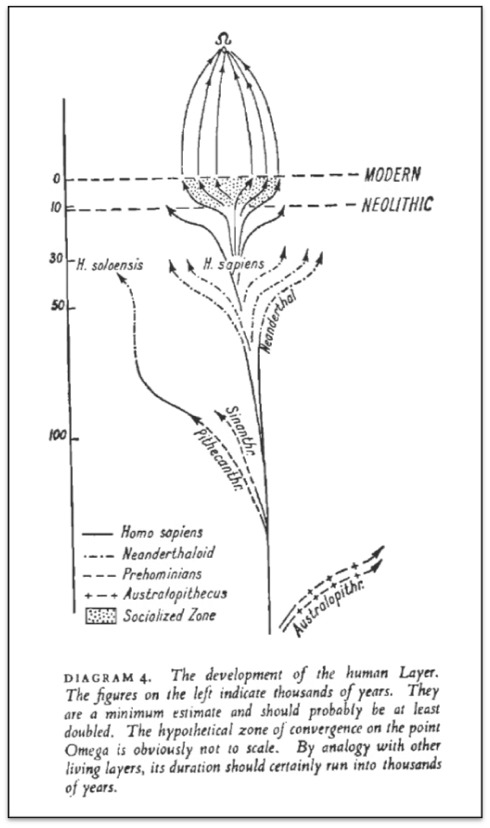

And I say this knowing—as you may as well, if you read Giroux’s introduction—that the phrase comes from the Jesuit philosopher Teilhard de Chardin: “Tout Ce Qui Monte Converge” (xv). Robert Giroux relates that the phrases appears in French, in an anthology he had sent O’Connor of the philosopher’s work. Yet, if anything, going back and reading Teilhard de Chardin and how he uses the phrase makes O’Connor’s usage of the phrase embettered, not worsened, by the repetition. Here’s the version of the passage most often quoted, which is not actually the philosopher’s but one of his students/anthologists. From Max H. Begouen’s Foreword to Building the Earth: “He gave each of them this watchword: ‘Remain true to yourselves, but move ever upward toward greater consciousness and greater love! At the summit you will find yourselves united with all those who, from every direction, have made the same ascent. For everything that rises must converge’” (13). Here’s one version in his own words, from the essay “Faith in Man,” expressing a major theme in the philosopher’s work: “Followed to their conclusion the two paths must certainly end by coming together: for in the nature of things everything that is faith must rise, and everything that rises must converge” (186). In other words, where Teilhard de Chardin is saying something about the nature of our common humanity converging in ever-greater complexity and perfection, O’Connor is injecting something insistent, something dark into this message of hope. In doing so, she is not trying to negate the utopian vision of the philosopher, but to transform it by way of adding in the full range of human experience. For O’Connor, thinking about convergence means thinking about life in a place where sectarianism is stuck on the Catholic/Protestant divide so strongly that to be a Catholic is so alien that one might as well be Jewish (and anything further afield would be meaningless to the young Church of God boys); where buses had only been desegregated in Browder v. Gayle five years before she wrote the story; and where the number of women receiving PhDs in Philosophy in the 1950s—much less in the South—was vanishingly small. In other words, O’Connor injects a certain Southern peculiarity combined with a bit of Gothic uncanniness into this convergence. Faith, theological or not, is easy when it does not have a world to contend with, and if it is easy, it is no faith at all.

But before we talk about the Southern Gothic, I want to return to the title, because I love it so much. Ultimately, beyond any particular meaning it derives from and alongside the story itself, it’s the beauty of a phrase that lingers in one’s mind, insists on coming back again and again, that I want to discuss. I want to discuss it because it gets at the heart of something about literature. For instance, when I say it’s “the best,” on what criteria am I basing that judgement? Are those objective, or purely subjective? Am I repeating a mistake we see from so many of O’Connor’s characters, of assuming that their personal preference can stand in for everyone else’s (and that those who disagree must be wrong)? Short answer: no. I’m saying this for effect. I know it’s just me. But the longer answer is that the particularity of my judgment on this title does give us a clue to the universality of something about language. Our psyches are, ultimately, linguistic; all the sense-experience, emotions, and logic that we deploy emerges out of and is filtered through language. Language makes possible what we can know of our world, and some of the greatest tragedies of our lives are marked by our inability to find a language that fits our experience—of love, of friendship, of betrayal, of death—often because someone else is imposing their language on us, or because there is no language at all for it. Sometimes we have to invent it. I don’t know what part of my self, per se, needs the phrase everything that rises must converge, but some part does. Thank you, Flannery O’Connor.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, 1955

II. Misery Like a Coastal Shelf

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

—Philip Larkin, “This Be The Verse”

What is it about the South that lends itself to the gothic? Ever since Edgar Allen Poe’s American reinvention of that European genre—of ancient curses, crumbling castles, monsters and murderers, of innocent women in distress and dark and stormy nights—Southern literature has often veered of into the uncanny and horrific as it’s modus operandi. And the answer as to why? Well, it’s not all the decaying castles scattered across the countryside. The answer is obvious: it’s slavery. The deep secret, the obscure past, the meaningless descent into gratuitous violence, the uncanny return of repressed trauma and desire: slavery.

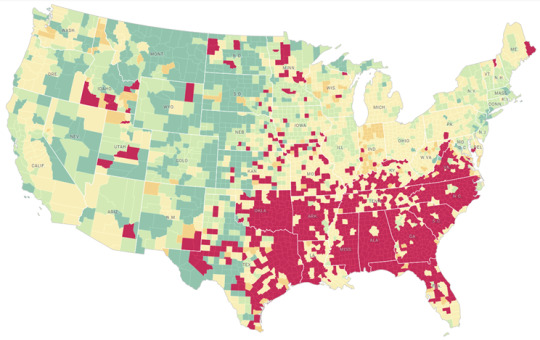

Let’s take a tour of some maps… First, what do you think this one is?

If you answered “a map of which parts of America started socially distancing when during the pandemic,” then you are a winner. Here’s the key I excised from the original New York Times article the map appeared in (Ganz et al).

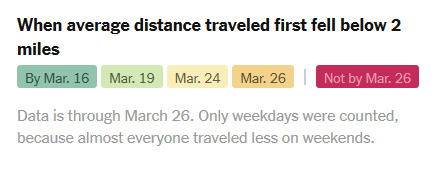

You’d be forgiven for mistaking this for a map of a lot of different things, but let’s cut to the chase. Here’s the second map:

In case you’re having difficulty reading the title, let me help with this U.S. Coast Survey from 1861: “Map showing the distribution of the slave population of the southern states of the United States.” But just in case the point is not clear yet, here’s map number three:

That, everyone, is a map of the United States as it looked during the late Cretaceous period, many millions of years ago (126-65 mya, to be geologically precise; see Krulwich). That inland sea left rich alluvial deposits that became the fertile crescent of land known as, first geologically and then politically, the Black Belt. Needless to say, the agricultural quality of the land correlates strongly with the intensity of slavery practiced in the American South.

In Sigmund Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents (a book we read often here in The Human Situation), the psychoanalyst uses the metaphor of the ruins of Rome to talk about the deep history of our own human minds. He wants us to understand how, even after they’ve been totally erased and are irretrievable, our earliest experiences shape who we are, just as the long-obliterated strata of Rome each successively dictated what was built after them. For me, when Larkin evoked misery deepening like a coastal shelf, Freud’s ruins of Rome and the cretaceous South sprang immediately to mind; I took it not as simile, but something that could be, often is, literally true.

This is what is meant in Faulkner’s famous epigraph about the past never being dead. Southern Gothic emerged as one of the most distinctive genres, blending mystery and murder and a deep sense of a looming violence in the world. Flannery O’Connor’s stories, as we have all seen, could easily be turned into horror movies, and William Faulkner’s work also includes many of the same themes. If we include Toni Morrison and Cormac McCarthy (e.g., the hauntings in Beloved or the demonic Judge of Blood Meridian), then the genre is easily the defining movement of twentieth century American literature. And it is not only slavery, but the history of violence that is the warp and weft of the institution, that colors our Southern Gothic. The Civil War is still the deadliest war in American history, and it’s not even close. Indeed, scholars have argued, often convincingly, that the region has to this day not recovered from the economic, social, and political devastation caused by the military conflict alone, not to mention its aftershocks, the devastation like a modern war fought 75-100 years before its time. “The past is never dead. It's not even past.”

III. The Injury of Intelligence, the Insult of an Education

A. Intelligence Is a Curse

As I’m sure you’ve noticed by now, O’Connor’s stories are chock full of characters for whom their intelligence is a curse. Hulga almost causes her mother an existential crisis because the pleasure- reading she leaves lying around is Heidegger’s “What Is Metaphysics?”; The Child is clearly the smartest one in the room; even The Misfit was marked off at a young age: “‘You know,’ Daddy said, ‘some that can live their whole life out without asking about it an it’s other has to know why it is, and this boy is one of the latters’” (129). So, too, Julian.

Julian is a writer who does not write. Like Hulga, whose philosophy is solely for herself, Julian’s fantasy world is solely for himself. And he seems to know that he is not a writer—he never expects to make a life/career/money out of it—which forces us to ask: why does he identify as a writer? But before we answer that question, let’s get right to the stakes. The clue is in the title, and O’Connor doesn’t make us wait too long. Immediately after she tells her son that he should be proud that his ancestors owned hundreds of slaves, Julian’s mother gets down to commentary on civil rights: “They should rise, yes, but on their own side of the fence” (408, emphasis added). So, rise: yes; converge: not so much for Julian’s mother. It is no mistake that this story takes place on a bus, the public space Rosa Parks made famous and which the Supreme Court desegregated in its 1956 ruling in Browder v. Gayle, five years before this story was published; the bus, for O’Connor, is again not a metaphor for race relations, it is the thing itself. Thus, unlike for Hulga, Julian’s fate and choices are going to extend far beyond himself—to the status of racism in America, the history of slavery, and reparations therefore—although they will extend to himself, too. Perhaps O’Connor is saying that the repercussions of the choices of the two, philosopher and writer, have different stakes. Perhaps.

Which brings us back to all these emotionally fraught intellectuals here, decaying slowly, like fish out of water, in their Southern hometowns. This theme is important for O’Connor because it argues intelligence, reason itself even, can serve not as something that enlightens, but something that closes off, distances, and deceives. The dark of reason. Like The Child in “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” they can only see the difference in all things, and not the sameness; there are parts of everyday life that they have utterly rejected, and thus cannot connect to; they are alienated on their own soil, homeless in their own homes. And often with good reason! Julian’s mother is an out and out racist, and she represents the norm. He should reject her racism. But, for some reason, he cannot reject her herself. And he cannot reconcile the one to the other. I love her: she’s a racist; I must reject racism: I must reject her. His very love for his mother is a source of immense guilt for Julian, and that right there is the essence of the Southern Gothic.

There is a deeper lesson here, one that we don’t really have time for, about how Julian is actually trying to inhabit two different symbolic worlds, ones with different rules that justify themselves in different ways and that are ultimately incompatible. It’s like he speaks two different languages, but thinks they’re the same one and so often gets hopelessly confused. And the truth is something like that, when we recognize that culture is like a language that sets up rules for what and how we make meaning of the world. Heidegger famously said: “Language is the house of Being. In its home man dwells” (217). Hulga and Julian, justifiably reacting to the smallness and violence of the world they grew up in, have learned another world, but tragically cannot see their way back across the divide they have built; they’re emotionally attached, but intellectually distant, so they take refuge in that distance and decay psychologically, along with the old plantation mansion that Julian can’t help but dream about. Perhaps this is a problem O’Connor understood all too well. Her writing teacher in the Iowa MFA program had to ask her “to write down what she had just said” the first time they met her Georgia accent was so thick (vii, all emphasis mine).

B. A Martyr to the Desire of the Other; Or, that St. Sebastian Painting One More Time

When I worked in that highly suggestive, very famous painting of St. Sebastian into my lecture on Voltaire, I had totally forgotten that our erstwhile saint figured into our story for today, even though I had been reading O’Connor again over break. Sometimes the Unconscious, to paraphrase Larkin, fucks you up, but every now and again it does you a favor.

One of Julian’s fantasies is that he is a martyr to his mother. This should right away give us some pause. Take this for instance: “Everything that gave her pleasure was small and depressed him” (405). There is something deeply wrong with Julian’s relationship to his mother here; in fact, this is not a healthy relationship to have with any human being. Why on earth does Julian care what gives his mother pleasure? Shouldn’t he be happy that she is happy, despite it being over a ridiculous hat? Why would you ever arrange it so that, in the most important relationship in your entire world, anything that makes the other person happy makes you sad? That, my friends, is a recipe for disaster, death and disaster and tragedy. You don’t even have to read to the end. This is not going to end well.

To understand characters, you have to understand their motivations. This can be tricky. We can’t assume the characters are us, or anyone else but who they are. There are many possibilities for why Julian does what he does—alien mind control, for instance—but very few plausible ones. What, then, are Julian’s plausible alternatives here to his misery. Alternative one: leave his mother and move far away. He wants to be a writer? New York City, Paris, hell Houston or Atlanta: get thee hence. Anywhere but here (Hulga, too). Why, then, does he stay? We can be very, very cynical and say that Julian is broke and his mom’s supporting him. True! But not really enough. A lot of life can be lived in cheap apartments with ramen noodles, even on the commission of a typewriter salesman. This would be an excuse he would be telling himself, though we should also assume that many of the jobs he might be qualified for he would reject because they would conflict too heavily with his identity (as a writer), or just embarrass him (as being beneath him and his college education).

I think the real clue is in the saint imagery. But it’s not him who’s the saint, it’s his mother—a fair description for her achievements vis-à-vis Julian, which are not small, and which she is justly proud of. Even if taken literally, if he is suffering for his mother, as a saint, that means his mother is Jesus! His non-sacrifice of riding on a bus with his mother—“the time he would be sacrificed to her pleasure” (406)— is really her sacrifice. The problem is that, in this twisted relationship, his mother-the-saint is also a racist. Moreover, he knows that she’s not doing this for her pleasure: her doctor has told her she might die if she doesn’t become more active. Yet that’s how he frames it, which makes no sense … unless, here again, we should take this more literally than he means it: she’s staving off death, and as long as she is alive and enjoying life, then of course he cannot enjoy it. Ipso facto, he wants her to die, so he can move on. Again, her very existence is a source of guilt for him. Not because he hates her, but because he loves her.

C. The Terror of Identity; Or, Meeting Yourself Coming and Going

What does the phrase “you won’t meet yourself coming and going” (407) even mean? I had to pause at this phrase after O’Connor repeats it in the story, making sure to remember, as Professor Charara reminded us, that just because it is a cliché for the characters doesn’t mean that it is one for O’Connor. In short, it signifies a desire for uniqueness. If you do not meet yourself coming or going, you will not see someone else that looks like you on your journey.

This desire—to be singular, unique—is a pretty basic one. We all need some manner of distinguishing ourselves from others, otherwise the difference between self and other breaks down, and what it means to be uniquely our self does with it. This loss of self is, in almost all cases, terrifying for us. It is terrifying for Julian, because it is precisely what he fears in relation to his mother: he will never have his own desires, his own identity, but merely be an extension of hers, subsumed by his mother’s identity, her view of him. He will always be, as Professor Wallace discussed, an object and never a subject. (At the same time, to have nothing in common with other human beings is an opposite extreme, untenable as well. What it would even mean, to share no qualities with other people, no common bond over which you could unite, no language, aspirations, or anything else? Nothing.)

Of course, his mother does indeed meet herself going to the reducing class, in the form of a black woman with her child, angered about … something. Long story short, this woman hits Julian’s mother and storms off when she tries to give her child a penny. There is much to be wrung interpretively from whether or not it is this blow that causes his mother’s death, or Julian’s reaction to it. But I think this is a bit beside the point, much as the hat is. The truth of the situation is in Julian’s belated realization of his unacknowledged love for his mother—he calls out to her as a mother would to a child, or even a lover to their beloved, at the end, “Darling, sweetheart, wait!” (420)—and with that, his imminent “entry into the world of guilt and sorrow” (420). His coded wish for his mother’s death has been granted, but in so doing all the compromises he has made will no longer be tenable. He will, of course, blame himself for the way he acted vindictively toward her, even in her last moments, and he might even blame himself for her death.

Most of all, though, he will lose his ability to maintain that ironic distance that he has adopted toward the world, the one that has kept him locked into a fantasy world. There is compensation here: that fantasy allows him to live the life he secretly desires—not incidentally, the one where he can acknowledge his mother’s love and sacrifice, if not in word, then in deed. He does devote himself to his mother; despite what he says he is on that bus. The “in word” part is crucial here. Julian wants to be a writer because it allows him to keep an ironic distance toward the world as the detached observer who can catalogue all the worlds foibles while imagining that he is the hero setting them aright. But not in the real world, which is a bit too messy. When he imagines marrying a black woman, he tempers this fantasy by writing his fictional lover as not too black, her race only a suspicion (414). When he befriends black folk in his fantasies, it is only “the better types” (414). And when he imagines joining a sit-in, this is “possible but he did not linger with it” (414). Of course the possible is not something he lingers with! There is no ironic distance in the possible. Only jail, maybe even death. In fact, in a very real sense, Julian needs injustice to continue, because if it disappeared he would be forced to confront everything that he is fobbing off. Thus: “It gave him a certain satisfaction to see injustice in daily operation. It confirmed his view that with a few exceptions there was no one worth knowing within a radius of three hundred miles” (412).

I think a more interesting question than whether or not the child’s mother is responsible for Julian’s mother’s death is why she is angry to begin with. Julian is probably not wrong, that negotiating the casual violence of an antiblack society has shaped her outlook, and primed her for confrontation as an understandable survival strategy (compare her to the man who buries his nose in a newspaper, learning about the world at large while ignoring the world at hand). But perhaps we should look closer to home. If you were a mother negotiating public transit with your child, might you be annoyed if a grown man—a white man, in this very specific instance—forced you to split yourself off from your young child? And, assuming that she’s as good a reader of the world as Julian is, when you realize that he’s forced you into this situation because of some tiff he’s having with his mother? Julian delights in the fact that the children have been split from their mothers; he is himself keenly aware of the dynamic at play here. But because he is trapped in his own bubble—his own decaying mansion of the mind—he cannot see that maybe she does, too. And if Julian’s desire to separate himself from his own mother is achieved in this awkward social situation, it is imposed upon the mother and her child. Yet the stakes for each are different, and Julian knows this, too. He sees it coming from a mile away, but what he can’t see is that the cause is not his mother, but himself, and he cannot see it because then he would be the one thing he cannot be, his mother. He would see himself coming and going, in her.

Bibliography

Femia, Will. “Paleo-Politics: The Really Long View.” MSNBC, 24 Aug. 2012. Msnbc.com, http://www.msnbc.com/rachel-maddow-show/paleo-politics-the-really-long-view.

Glanz, James, et al. “Where America Didn’t Stay Home Even as the Virus Spread.” The New York Times, 2 Apr. 2020. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/02/us/coronavirus-social-distancing.html.

Heidegger, Martin. Basic Writings: From Being and Time (1927) to The Task of Thinking (1964). Rev. and Expanded ed, San Francisco: Harper, 1993.

Helms, Douglas. “Soil and Southern History.” Agricultural History, vol. 74, no. 4, Agricultural History Society, 2000, pp. 723–58. JSTOR.

Krulwich, Robert. “Obama’s Secret Weapon In The South: Small, Dead, But Still Kickin’.” Krulwich Wonders. NPR.Org. 10 Oct 2012. https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2012/10/02/162163801/obama-s-secret-weapon-in-the-south-small-dead-but-still-kickin. Accessed 14 Apr. 2020.

Mullen, Lincoln. “These Maps Reveal How Slavery Expanded Across the United States.” Smithsonian Magazine. www.smithsonianmag.com,

Faulkner, William. Novels, 1942-1954. New York: Library of America, 1994.

O’Connor, Flannery. The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1972.

Reni, Guido. Saint Sebastian. Circa 1615. Musei di Strada Nuova, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guido_Reni_-_Saint_Sebastian_-_Google_Art_Project_(27740148).jpg.

Sexton, Richard. Oak Avenue, Wormsloe Plantation. 2009, https://richardsextonstudio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/19-c070.jpg.

Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. Building the Earth. Wilkes-Barre, Pa. : Dimension Books, 1965. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/buildingearth0000teil_y0u0.

——. The Future of Man. New York: Doubleday, 2004.

——. The Phenomenon of Man. New York: Harper Perennial, 1955.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dimepiece :: Chimwemwe Undi

Why poetry?

Audre Lorde writes that poetry is “the quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives”. Co-sign! Toying around with language, making writing good and fun, surprising and necessary is not a luxury but it is a pleasure. It’s best thing you can do with words besides ordering food and thanking Black women.

What are you working on right now?

I’m working on writing more about things that make me want to dance, and less about things I am certain will kill me and those I love, but the world makes that difficult. I’m also writing my master’s thesis.

What is your routine for writing? Do you have one?

I try to write everyday, even if it’s bad and it often is. It’s less a routine than a philosophy, rejecting the notion of writers block and viewing writing as a craft that I work on, even when I don’t feel inspired or moved and it’s not as fun. It’s like keeping the faucet running until the hot water comes out. I edit afterwards. I read a lot, so I don’t have to figure everything out by myself, and because books are good.

What is the best advice you've received as a poet?

Read! And be kind to people.

Why do you live where you do?

I like it here. I’ve been a guest on Treaty One for a decade now, and I feel privileged to be party to so much of the hard, important work happening here. Winnipeg is like a kid who wasn’t very cool or good at sports and so has been forced to master comedy and compassion. It’s a small city and people collaborate on art and buy tickets to parties to help people pay for weddings they aren’t invited to.

Where is the wildest place poetry has taken you?

I did three performances at the Edinburgh International Book Festival (in Scotland) last summer, and spent the whole time like a human embodiment of the sax riff in that Carly Rae song.

What artists most inspire you, and why?

I struggle to rank inspiration, or to trace it. I’m thinking a lot lately about Missy Elliott, and always about Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, of course, and the song they did together that taught me the zodiac signs. I return frequently to work by Jillian Christmas, Dionne Brand, Vivek Shraya, Amber Dawn, Joshua Whitehead, Sleater-Kinney, Ross Gay. I copied out Terrance Hayes’ How to Draw a Perfect Circle and put it in my backpack so I could feel it there. I saw a Dineo Seshee Bopape exhibit in France last year and it keeps appearing in my head, Nina Simone, a pile of rubble, this red, red, room.

What was the last book you finished reading?

My chapbook was published alongside 9 brilliant chapbooks by young African poets, and they’ve been on backpack rotation. Katherena Vermette’s The Break is fantastic and necessary. I also just finished Priscilla Hayner’s Unspeakable Truths, which is about transitional justice, and was reminded that good analysis is truly poetic.

What has been one of your favorite moments on stage?

This filthily blasphemous performance I did with (shadow) puppeteer A Raven Called Crow, a banjo player named Adam, and a poem I had written that afternoon at the Victoria Spoken Word Festival in 2014. I was breathless and terrified that entire week, and I did things anyway.

What would you like to be doing five years from now?

Still writing in every way I like to, still taking too long to get ready because I’m dancing too hard, still reading poems that remind me why I write them. Oh, and done with school, finally. A full-length would be pretty neat, too.

Chimwemwe Undi is a poet and linguist based on Treaty One territory, Winnipeg, Manitoba. She has performed at the Canadian Festival of Spoken Word and the Edinburgh International Book Festival, and been published in CV2, Prairie Fire and Room Magazine’s 40th anniversary anthology, Making Room, along others. Her debut chapbook, The Habitual Be, is out from University of Nebraska Press.

[photo: Derek Ford]

1 note

·

View note

Text

when inside feels outside and outside feels inside

m-est.org, June 2015

Conversation: Nancy Atakan with Merve Ünsal

An earlier version of this text was published in Turkish in Cin Ayşe Fanzin.

“Women, then, stands in patriarchal culture as signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his fantasies and obsessions through linguistic command by imposing them on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning.” —Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Blackwell Oxford UK & Cambridge USA, 1993, p. 964.

Lucy Lippard’s 1974 touring show called “7,500” helped legitimize work by 27 female artists. Even though marginalized in the 1970s, work by such artists Hanne Darboven, Adrian Piper, Laurie Anderson, and Martha Rosler now serve as important models for a later generation of male and female artists. Their approaches that included everyday gestures concentrated on subjective issues about identity.

What was the initial situation in Turkey in regard to the questioning of modernism? Between 1977 and 1987, the Fine Arts Academy within the Istanbul Art Festival agenda sponsored bi-annual exhibitions entitled “Yeni Eğilimler (New Directions).” Many of the artists, even the female artists, who participated in these shows, Şükrü Aysan, Osman Dinç, Serhat Kiraz, Cengiz Çekil, Canan Beykal, Alparslan Baloğlu, Ergül Özkutan, Ayşe Erkmen, Füsun Onur, Gürel Yontan, İsmail Saray, Gülsün Karamustafa, Handan Börüteçene, and Yılmaz Aysan, did not work outside the painting and sculpture tradition, but most of their work questioned modern art theory, experiment with contemporary art approaches, and emphasize idea.

In the 1990s, I did my doctoral thesis about alternatives to painting and sculpture in Turkey. After completing my research, I rejected painting as an acceptable technique while I re-formulated my artistic aims and approach. Perhaps in some respects, as role models, I chose the work of Canan Beykal, Ayşe Erkmen, Füsun Onur, and Gülsüm Karamustafa. Perhaps they were not exactly role models, but female artists about whom I researched before I began to make what I call “Art as dialogue.” These are artists I respect and their existence made me confident that the way I wanted to work was legitimate. While using contemporary modes of communication and envisioning all types of collaboration both for the materialization and presentation of art objects in art events, I took dialogue, human interaction and social context as a theoretical base. I used the term “Art as Dialogue” to describe my way of working. Today I see the art process as a place to ask questions, to solve problems, as well as to create models for working and living together; models for learning to interact, to communicate, to network, to live side by side with polarity and to establish relationships. I see the art space, 5533, which I opened together with Volkan Aslan in 2008 as a continuation of my art practice. I make neon signs, digital videos, photographic work, digital prints, installations, and artist books that explore the relationship between image and word as well as deal with psychological, social, linguistic, gender and personal topics.

I asked an artist from a younger generation, Merve Ünsal, to carry on an email conversation with me about our respective art practices. I was first drawn to Merve’s work during our initial encounter at her 2013 CDA-Projects Grant Lecture Performance, “A text begins and ends.” Our relationship deepened after Özge Ersoy invited Merve to do collaborative work during the spring of 2014 at 5533. At the core of our work, I see numerous similar aims. —Nancy Atakan

Nancy:

I started looking at books I have that mention conceptual art and women. I am wondering if we could focus on a text, a paragraph, or a sentence and come up with something else. Do you have any favorite text about women and conceptual art?

Also, your “Tip-ex” work [1] reminds me of Lawrence Weiner’s square that he dug into the wall. Wherever he dug and wherever you wrote the results are always different. Also, there is the trace of handiwork in both. And of course you chose a white square, sort of Malevich, but you use an everyday material that is sort of out of date and more from the 60s or 70s. These are just things that popped into my mind.

Then your work about the idea of measuring Istanbul Modern with lipstick and with no documentation but just a security guard as witness [2], I want to think more about this.

I like this idea of a dialogue.

I also like the use of Cin Ayşe [as a platform] because it was Cin Ali (masculine) teaching generations to read and this is like its imagined feminine. Conceptual art was masculine and about language but we transformed it… or did we?

Merve:

I think a lot about the relationship between conceptualism and femininity and what that means. Whether there can be masculine or feminine art and what we think about the gender, the age of the person who made the work when we look at something. And I also wonder how this ties into the way we think and do things, as in, the way we code gender before even producing it.

I do really like this idea of dialogue as well and perhaps it can be in the form of these e-mails edited somehow, going back and forth. We can set certain parameters.

Nancy:

I am most interested in your work for 5533 entitled “Almost done.”

You did it exactly one year after Gülçin Aksoy and I did our 5533 project that we called “While thinking about all of this…” [3] I see that you are extremely focused and minimal when you materialize a project. Gülçin and I cannot seem to be. We understand each other but our work spreads and meanders like oil.

Merve:

I criticize myself often for exactly the same reasons that you mentioned as I feel that I cannot just let go and be a free artistic spirit. Perhaps we could start with the relationship between process and product and what that means for our mutual practices?

Nancy:

This is interesting. You made me realize that I criticize myself for lack of focus. I always do too much, have too many levels, too many thoughts, too many ideas, and I want to keep everything; elimination to just the essential, minimal is next to impossible. I praised in your work, I admire, what I see as my lack.

The relationship of process and product. I am definitely strong on the process side of this equation. I did my masters degree in psychology. I had to conduct “scientific” research projects and take statistics. What did I learn? That for me these tools and methods don’t work. I want to understand, but intuitively, through my own personal process of investigation that includes random encounters. While writing my thesis I discovered philosophy. As I live from day to day, as I read, listen, hear, feel, experience, walk, etc. questions arise. The question may appear new, but it is generally connected to an ongoing theme, but I can only see that later. Many questions start from a gut feeling. Do I find answers…generally I do not but I learn a lot as I deal with the process of questioning. And nothing is linear, nothing proceeds from “a” to “b”. It goes “a” to “u” back to “c” and then another look at “a.” I collect a lot of data, nothing systematically. I chance upon an article in a book that I just happened to pick up. A friend asks me to accompany her on a trip and it all of a sudden brings with it the visual images I needed.

This process can take years. This is the fun part.

Then to transform all my data into a form into a product involves for me a lot of work and sleepless nights. It is painful and not fun at all. How to zoom in? How to focus? How to simplify from all the clutter and noise in my head? Generally, I begin by talking with one or two artists I admire and trust. I can talk with many, Gül Ilgaz, Gülçin Aksoy, Ipek Duben, Volkan Aslan, Kalliopi Lemos. My family, my sons, daughter in laws, husband until they get tired of my “sharing.” I talk with friends too. Procrastination? Perhaps. Slowly a route appears. A lot of experimentation, many failures, much frustration, but finally a solution, perhaps.

There is so much involved. Everything very complicated. I can use whatever material or methodology I find necessary but I quit painting in 1990 and I do not plan to use that “male” dominated methodology again, but drawing is okay.

Merve:

I have a tendency to think in terms of words, situations, scenarios, abstractions rather than images. Although I come from studio photography and art history, I have always thought of what I wanted to in terms of language rather than in terms of the image. I remember juxtaposing negatives (“sandwiching” negatives) with predetermined formulas rather than just printing them, when I first started to make photographs. In this sense, I make rather than find or create. I think there is somewhat of a distinction there.

I like distilling ideas to the point they are pulp. I don’t have an experiment-based process or rather, I really don’t experiment with materials in the traditional sense. My work is primarily based on gestures, whether this is a gesture of doing something or making something—they are one and the same to me, action and product.

Could you draw a map of your process?

Nancy:

First of all, thinking in terms of words rather than images is fascinating. I ask myself if I do the same. The answer is sometimes. Sometimes I start from words and sometimes from images. That is why I have sometimes explored the relationship between word and image. When is image in control? When is word in control? Can they be equal rather than one being a support to the other? Then there is translation, can one be translated into the other? Is something always lost in translation? This line of experimentation can go on and on and runs throughout my work. If you do not understand a language, then words become an image. It seems to me that Turkish is mathematical and logical while English is pictorial.

Make, find, create…yes make is the right word, but I may make from things I find by re-arranging, transposing, connecting, eliminating, translating, combining etc. Nothing is created out of nothing.

Action and product are one in the same sometimes for me but not always. Most of the time not, but yes if it is a performance like ” I believe I don’t believe” or the performance I did with Gülçin Aksoy at 5533 last year or even “Silent Scream.”

Now draw a map! A map means moving up and distancing and distilling and abstracting and then naming. It is easier for me to tell a story. But idea would be in the middle and then there would be moving outwards in all directions. Sometimes ending, sometimes converging. It would look like the grounds in a coffee cup ready for fortune telling. There would be roads, flights, things, random planning, a lot of sprawl like Istanbul. This would be the process map… then we would have to put a piece of transparent paper on top to select what will be used for production. Everything must be drawn in pencil because there would be a lot of erasing.

In reality, I only have a few central themes that I investigate over and over but in different ways. I want to understand myself, my environment, lived experience… I am continuously in search of a role model, a female role model. I investigate women who have influenced my life to understand them and myself. The women from the early Turkish Republic fascinate me. They were between two cultures, two languages, looking for role models in a male dominated world. They took their fathers as role models and their mother’s disappeared. Luce Irigaray’s writings have helped me think about our lack of female role models. I ask where is our pink goddess where are our female heroes. And then when we come to language there are other issues… Like Julia Kristiva wrote, functioning in a world using a language other than your mother tongue is like continually having a fist shoved down your throat.

Do you have central themes that you return to over and over?

Merve:

I also think a lot about the idea of transliteration. From what I know or understand, translation is between languages whereas transliteration acknowledges from the beginning that the two things that you are going between are essentially different forms. I have noticed that I use transliteration quite often in my writing and I think a lot in terms of transliteration as well. A sentiment or a sensation or a situation gets transliterated into a work, sometimes. Hale Tenger’s image of the balloons that you shoot at in Kadıköy come to mind, recently shown at Depo. It is about that feeling of walking by the people who market the shooting with their colorful balloons and their perfect mis-en-scene and that wistfulness. Perhaps I’m being sentimental, but I do think a lot about that going back and forth between the image and language and what happens in between and how, when this transliteration works, it just works and you’ve got it.

In terms of themes, one of the things that I wonder about often is the functionality of the art and the artist. There is the concept of “arte util” as developed by Tania Brueguera that I was exposed to recently, a tongue-in-cheek take on what it means to make functional, useful art. While I think this is a very important definition, my thinking veers into the direction of what it means to make art and where that action begins and ends. When you look at gesture-based things, such as cleaning the front steps of a museum, there is also a very useful element that would not perhaps fall into the category of arte util. The functionality of the artist is something that is inherently linked to the idea of functional art but that also is my research on what it means to be an artist—as studio practices disappear, what defines our role or profession? Is it some sort of glorified amateurism? Is it a visual way of thinking? Is it about research?

I also wonder the point you made about role models and their importance in your practice – role models are crucial for anybody’s personal, professional, emotional development, but how do you provide a fertile ground on which artists and women can find their role models? Especially in an under-historicized context like Turkey, I find it very important to see more of women of older generations, specifically within the art context, speaking up about their experiences of making work, and just being.

Nancy:

I love your bringing everything down to pulp possibly because it is something that I cannot possibly manage, but you have brought in another element (one that I think is particularly feminine) of collaboration (işbirliği).[5]

While Gülçin Aksoy and I are more sprawling and never can bring things down to pulp, our collaboration about research based art and the contrasting global value placed on humans and objects and their ability to travel could be seen in juxtaposition with your exhibition. We have this messy circular way of working and experiencing and traveling around while working and understanding. In our own way we made a tautology in that we illustrated research based art while it was being discussed in a panel.

Merve:

I love that you call it a tautology as your practice seems to be built outside of tautologies and major statements; I don’t by any means say this to mean that there are no statements. On the contrary, the statements are there and are repeated through your practice, rather than becoming the kind of statement that becomes hollow with repetition.

All exhibitions mimic maps in my mind, somehow. There are different coordinates, paths around the same idea, or a cluster of ideas, that you try to drive home in the form of an exhibition. An exhibition is a sentence while a work is like a one-word poem—it’s possible to write a one-word poem but there is something also so alluring about sentences or clusters of words…

Merve:

One thing I forgot to mention in a previous e-mail is the idea of collaboration, which is also very dear to my practice, but not directly for my art works. It’s also very significant, for me that we somehow met through 5533 and now this collaboration is taking on other forms. My collaboration with Özge is central to everything that I do, whether this is her curating my exhibition or our writing together or just thinking together. I wonder what this means to collaborate with a curator rather than another artist?

Nancy:

In conclusion I will write:

As shown in our “art as dialogue email conversation”, with our art practices, Merve and I strive to become our own “makers of meaning” in our gestures and our working process, as we both present with equal importance our writing about art, our art-based research about translation and transliteration, our emphasis on collaboration, our fascination with words and our use of dialogue.

Endnotes:

[1] 1 m x 1 m, Tip-ex on wall, applied in situ, 2014. Tip-ex is applied directly to the wall. The emphasis thus becomes the contribution to a group exhibition, putting something on the wall that is similar in size to everything else that is exhibited, which cannot be moved. The work has been realized twice so far, for the first time in 5533 and the second time in Galeri Zilberman, both in Istanbul.

[2] Unrealized performance proposal, 2014. The proposal is to measure the periphery of the Istanbul Modern building with a lipstick. The unit of measurement is thus not centimeters, meters, yards, or feet, but a lipstick. I use one tube of lipstick and the whole periphery of the building will be measured, including the private areas and the dock. This performance is to be realized once, not to be recorded, and in the presence of a security guard if needed.

[3] Aksoy and Atakan co-produced an artwork “Retaining People, Circulating Objects”, at 5533. After researchıng types of power systems that control human interaction and mobility, Aksoy and Atakan problematize the often insurmountable barriers non-westerners face with movement restrictions. Parallel to this, they invited Prof. Dr. Leyla Neyzi (researcher, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Sabancı University), Asena Günal (ProjectCoordinator for Depo), Merve Elveren (Research and Programs at SALT), Ayfer Karabıyık (Doctoral student at Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts) and Filiz Avunduk (program director 5533) to discuss related issues and investigate different artistic research-based approaches. During the discussion, Aksoy and Atakan demonstrated artistic research in real time.

[4] I [Nancy] find it paradoxical that these images, Ingres’s 1908 oil portrait of Francois Marius Granet and a 1930 snapshot of an Istanbul lady, resemble one another. With this work I point out that trying to be someone we are not, trying to become Western when we are not, trying to be Eastern when we are not, trying to be western when we are not, imitating the “other” without understanding, trying to fit into an alien environment, only brings sadness and melancholy and confusion.

[5] The work plays on the word for collaboration in Turkish. Literally broken apart into two parts, ʻişbirliğiʼ can be read as ʻiş birliğiʼ, which means the oneness or unity of work. Putting the ʻonenessʼ into parantheses, the word ʻişʼ, meaning ʻworkʼ is left outside, referring to the art work itself. The first edition of this work was initially produced for Özge Ersoy, a frequent collaborator. The work is an endless edition, produced upon demand.

0 notes

Text

Meghan Saul’s Interview with Rosemarie

The night I first met Rosemarie Dombrowski, she paired a black high-waisted pencil skirt with bold white dots and a white button-up with short sleeves and black polka dots the size a Sharpie would make. Her hair was pulled back; bright eyes behind dark rimmed glasses looked up energetically as she spoke about poetry to an audience of Community College faculty, family members, and creative award winners.

Rosemarie Dombrowski has a life centered around poetry: learning, teaching, and emotional exposing herself around the Valley and the world. (She studied West African dance as a graduate student at ASU - integrating studies of poetry and dance at the University of Ghana in ‘96.) Dombrowski also headed a poetry journal called Merge from 2005-2011, is the editor-and-chief of Rinky Dink Press (a poetry mini-zine,) and serves on the poetry board of Four Chambers. Outside of those credits, she is also a well-regarded writer, teacher, mother, partner, and, of course, an abundance of fun.

Poetic activities and events throughout the Valley have always been a passion for RD (as her students call her.) She was named Phoenix’ Poet Laureate in December 2016, and now enjoys said events as a dutiful contribution to her role with the city. As an emerging writer, I was ecstatic to find that RD was both approachable and willing to sit down with me. We met on a Monday afternoon at the steel counter of Sip Coffee & Beer Garage (<hyperlink) where RD ordered a large black coffee, which she spruced at our table with goodies from her oversized purse. She laughed genuinely as she obliged my request to pin a microphone to her strapless, cotton-maxi - calling our interview “so official,” even Cronkite like. I’m flattered that any of this seems remotely professional to her, as we’re seated at a high-top table with backless barstools. Immediately, RD blends casual conversation with authentic details. She speaks matter-of-factly about her life, work, and family in the two hours we are together and wears her metal-framed coral sunglasses the entire time. I learn that while the country maintains a Poet Laureate (Juan Felipe Herrera) most states also select their own. (Arizona’s is Alberto Rios.) The Navajo Nation appointed Laura Tohe, a professor at ASU in September 2015 as their Poet Laureate, and a handful of major cities around the country have begun to do the same. RD: Each week, I’m fielding somewhere in the neighborhood of five requests [or more] from teachers, educators, and otherwise. Saul: To do what? RD: Anything, really. I didn’t really think anyone would know that a poet laureateship had been created for the city of Phoenix. I mean how many people are listening to NPR at lunchtime? Saul: A lot... RD: (She smiles) I felt like maybe twenty people outside of the University would know. I felt it was a big deal, in my heart. I didn’t think that it was going to be a big deal, and then, when it really became a big deal, you know, behind the scenes, I was panicking. Lots of anxiety… I was constantly feeling the pressure to live up to whatever people’s expectations were. I didn’t know what they were, but I figured they were high. People knew about the position, suddenly they knew who I was and all of these personal things were being written about me. I thought, Oh my God; what if I fail? Even if I just fail at one event, that’s failure - in the public eye. I don’t know if I could handle that. I was putting a lot of pressure on myself. Saul: Are you used to being more in the public eye now? RD: Yes, I am. I feel like I know… Well, I don’t know what people expect of me, but I know what I expect of myself. I know what my bar is for the Poet Laureateship and I know that I can meet, even exceed that. In addition to a heavy rotation of speaking engagements and school visits, RD recently won a fellowship through the Lincoln Center through which she will create community gardens with lyrical art on the walls. Dombrowski has a number of other projects in mind for the city that she believes “will have long term impact.” Her passion is almost visible as she talks about visiting inner city schools and stimulating the minds of young people who have not been educated on various works she finds fundamental, as well as laws that might affect them. ---- SB1070 - u of a anthology - maya angelous --- Find/insert quote. Saul: What about the people who say poetry is not for them - that they can’t understand it? RD: The thing that intimidates people about poetry is that it’s written in verse form, with stanzas, that stop in the middle of the page instead of lines and sentences going to the end, as our eyes are sort of trained to read or process. If a poem were to look like a piece of prose, 90% of those people would approach [the same] text with almost no anxiety. I try to expose people to very narrative poetry. Very contemporary. I read it and give them a copy to follow along, so they can see that there may be a reason for the line breaks, but also, it is just a story. The thing I love about poetry; I call it the ubiquitous container. It’s fact, it’s fiction, it is history, it is culture, it’s autobiography, biography, it is self and others. It has no rules. Fiction has very specific rules; so does nonfiction. When people say poetry has too many rules? It has no fucking rules; thematic or topical. People don’t understand the line breaks. Saul: But there’s a cerebral aspect to it. RD: Every word has to be purposeful. It’s about concision, so it’s about excision as well. Economy of words, which I love. I think almost everyone in this day and age is attracted to economy of words. Again, it’s the visual that they are not attracted to. Saul: So, do you also consider yourself more cerebral than creative or more creative than cerebral? RD: No. God, no. (laughing) I’m not more cerebral. Saul: You use really big words... RD: I’m definitely not more cerebral. I’m in the low end of cerebral-ity… No, I am. (She offers reassurance in response to my eye roll.) Saul: Okay... RD: I mean, for an academic, I shudder to even use the term… For an academic, I am not. I’m not top-notch, not even close. I don’t think that I was a terribly studious student. Things came naturally to me when I was young. I always cut corners – because I needed to spend more time on dance. I think it just came innately to me; I would cut the academic corners in order to have more time to do the creative stuff. My priority has always been to have plenty of time for classes, rehearsal, choreography – which is still how I am. I’m a spin instructor. I spend a lot of time choreographing my schedule so that I can have time for my spin classes, for teaching spin classes, for writing and revising my manuscripts. Sometimes in the summer, I paint. I love repurposing antiques, so, I’m always trying to construct a schedule around that. ( check quote wording) Saul: And are you actually chiseling out chunks? Like: I’m going to paint here, this is when I spin, today, I’m going to write… RD: Spin is always on there. It is. But if I see a day, when there’s nothing, I’m definitely going to open the document entitled that month and write. Or I’m going to open up a manuscript that I’m working on; write and revise. If I see nothing on a day but online summer school, all of my documents are open. I also run Rinky Dink. (<insert hyperlink) That’s another thing that I do on my off days. If I see a day that doesn’t have anything on it – what I’m going to do on those off days, is have a Post-it note or something and I’m going to be like: Rinky Dink, manuscripts, my manuscript, Vitacost (<insert hyperlink) shopping…You know, whatever. Saul: Is spin how you keep your dancer self alive? RD: (Nods while laughing) It is, to some extent. [Also,] poetry, because poetry is linguistic lyricality. You just sort of transfer it from the body into the mind and the mouth. Saul: I love that. RD: (continuing) Years ago, that happened for me. When I stopped dancing at the high level [after] college, all of that energy, all of that creative, lyrical, bodily energy went into the poetry. I think, if anything, I’m very visceral in my poetry. Visceral, bodily, autobiographical. I’m very sort of, self and self into society oriented, if that makes sense. The self has to begin the composition and then the self can move in space and enter into other conversational, social, or cultural spaces. Maybe I do move like a dancer in my poems somehow, because I don’t think the two have ever really been separate for me. Rosemarie Dombrowski has two anthologies published. This year she released The Philosophy of Unclean Things (<insert hyperlink) with Finishing Line Press, in which her words delve readers into imagery related to fears, phobias, and other topics deemed unclean. The Book of Emergencies (<insert hyperlink) was published by Five Oaks Press and catalogs Dombrowski’s life as a single mother to her son on the Autism spectrum. Other pieces of her work have appeared in numerous journals and publications yet despite a CV that spans sixteen packed pages, RD comes across modest yet confident, ambitious and excited about the works she’s accomplished and what the future may hold. RD: The other thing I’ve been working on is called 17 Letters. They were epistolary poems, now they’re like flashes. Seventeen epistolary flashes written to my nonverbal seventeen-year-old son. They’re rough. They’re rough to get through. I’ve gone back into that highly confessional mode. Saul: I was going to ask you about that because that’s sort of what Saul She Wrote is all about. [Confessionalism] is authenticity at its core. There’s so much strength in being able to own your story, to work through it, and bring what you bring to the page. Is there a double edge sword to that, do you think? Is it fully freeing for you or is it as self-deprecating as it is may be freeing? RD: I’ve been writing in that mode for so long now. The Book of Emergencies was published in December of 2014, but, those poems span almost my son’s entire life. Saul: So, these started really upon the emergence of motherhood and his diagnosis? RD: Yes, and honestly, some of the earliest ones have not been revised. That’s just always been my natural mode - to be confessional and to tell a story in that way. They are narrative and confessional; it’s like a lyrical narrative if that makes sense. There’s always pieces of the narrative missing because I still privilege the lyrical composition over the narrative cohesion [which] also works for the world of autism because there is little that is cohesive or linear. Saul: They are so raw and real. When you go back and read them do you still feel true to the words? Do you critique them or desire to make them different? RD: I edited a lot of line breaks. I think only two poems underwent revisions. There’s not much that has changed for me there. I still read them and when I read them (not on the screen, because then I read them as a writer and start editing,) in the book themselves, I usually can't get through them without crying. That's how much of me, that’s how much of my life, my son’s culture, and the culture I feel like I am now a part of - voicing and giving agency to, is in those poems. I don't think that there could ever be anything that I will do, as a writer, that is going to be more authentic or more important. I feel like, they redeem, in some way, the flaws of my mothering. I mean this could be because I was raised Catholic, but they do feel like a confession to me. In some way, I feel very redeemed when i go back and read them. I feel absolved in some way. It is like the literal act of confession that I was raised on. You were asking about self-deprecation; there is a self-flagellation process embedded in the process of writing them as well. It’s that admission of “sin” that is the first step in the process. That has to be there and it has to be authentic. I think, if it’s not painful, in some way, then it’s not really a confession. Despite how improved my son’s behavior is, and despite how improved our relationship is, despite how much I want to tell that version of the story, there’s still so much ugly in the story, even [now] that unfolds on a daily basis. There are many times I think, I can’t take another minute of this. There’s no reprieve, no one who understands how hard I work on these sixteen hour cycles to be who I am. To be his mother, and the provider, to keep up the house, buy all organic food, keep him on his supplements, and do all this cooking each night for his breakfast and lunch. There can be bitterness about that. Saul: It’s a thankless job. RD: Funny that you would say thankless because I did write a line in one of the letters that says something about him teaching me that love is neither a solvable nor reciprocal equation. He’s Autistic, you know. Saul: It’s crazy that you are this literary academic and poet - don’t roll your eyes… Language is your art, it’s your dance, it’s your everything and then you are given this son who is nonverbal. What does that teach you or how does that change how you feel about communication? RD: It’s ironic, I know, but it takes me back to those years of dance. All those years of nonverbal communication, you know, where you use the body to express, not just emotions, but ideas and stories. Everything that I know about dance, all that it has taught me of communication is what I rely on: the art of movement, of touch, contact with the floor, with other people, proximity, distance. I dance with my son a lot. We go to music shows a lot and dance together. He gets very upset if I tell him there’s not enough room for us to dance. RD handed me her copy of (fill me out) at the start of our conversation. At a natural break in our conversation, I handed it back and asked her to read it aloud.

Saul: So good. RD: I’m so glad you think so. Though society continually shows appreciation for Rosemarie Dombrowski’s skillful composition, she maintains a humility that allows her to still appreciate my approval of how she’s approached our modern day Mad Lib. My favorite tidbits were when she spoke of “truth telling.” She writes that authenticity is “truth telling” with an asterisk to define the phrase as: “laying yourself bare/being vulnerable/telling your story in the hopes of eliciting compassion for yourself and others.” RD: My big thing right now comes from Jane Hirshfield. It’s in an essay that comes from her collection Nine Gates. She’s one of my favorite poets and she argues in one of these essays that creativity is less about a unique sort of aesthetic style than it is about truth telling. Creativity is truth telling - is what her argument is… I think that’s part of the message that I am trying to convey to the kids [when I speak.] Even if you don’t think you’re creative, if you tell your truth, your story (which is just like your fingerprint, no two are alike,) then you are creative. That is uniqueness right there. As she continued talking, I kept an eye on the clock, not wanting to be the reason she was late to pick up her son while secretly also wishing we could continue talking all day. Two hours was hardly enough time to absorb the powerful ways that Rosemarie Dombrowski’s story, passions, and struggles shape the way she navigates her life while simultaneously inspiring those around her. Hours and weeks after our interview, RD is still teaching me through the many names, and readings she mentioned; links and resources for which are listed below. Links to cool persons / things: Roxane Gay: Pank Magazine: Anne Sexton: Abortion Poem: Poetry of Resistance, Voices for Social Justice: Rinky Dink Press: Jane Hirschfield: Nine Gates: Alberto Rios: Laura Tohe: Haymarket Squares: _____ = poet who made first mini-zine Vitacost.com: Vocabulary Words: Epistolary Visceral Flagellation Anthology Ubiquitous Gregarious

https://www.facebook.com/saulshewrote/?pnref=lhc

0 notes