#i found seaweed in the gutter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

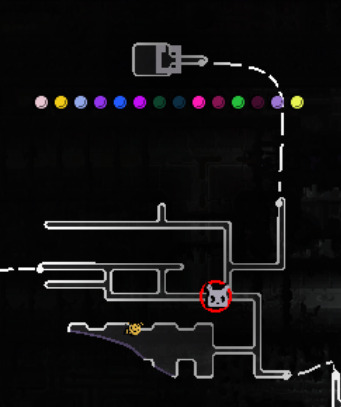

I’ve spent an absurd amount of time pearl hunting with TWO slug pups to the point to me Survivor is canonically a single mom with two kids going to college.

I’ll doodle them tomorrow for fun.

#also using feminine pronouns for surv#becahse to me#she and monk are the parallel siblings to moon and pebbles#its canon in my heart#anyway i LOOOOVE#these pups#im so attached to this run..#when those two get hurt i experience genuine panic#their names are beach ball and sea weed#i found beachball on cycle 8 so hes the big brubber#hes been with me for every pearl#i found seaweed in the gutter#and lost my mind because i thought the game would be too hard with 2 kids#but i got used to weighting 10000 pounds actually#im missing farm arrays pearls#sub and garbage wastes#and… sky islands. yuck parkouring with pups is awful

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring Acquired Skills from "Make Your Mark" Workshop.

I had recordings of humans interacting with nature on my phone, and decided to make them physical using skills acquired from Maeves's Make Your Mark Workshop.

I believed these recordings had potential and did not want them to go to waste. I used dried seaweed I found on the beach, dried autumn leaves I found on my walks (as documented with my primary photographs in previous posts) and a paintbrush with old dried paint on the bristles.

The paint I used was acrylic "Prussian Blue Hue". The sounds in the recordings are wet. Given the time of year, I gathered a cool toned blue would match the traits of wet and cold.

I chose these dry objects because the sounds were harsh. Unfortunately, Tumblr only allowed one video per post, so I will post the recordings with the correlating sounds separately.

First : cars driving in the rain.

Second : walking on wet leaves.

Third : rain falling down the side of a roof gutter.

0 notes

Note

“Hands brushing unexpectedly” maybe on one of those tourist attractions...? 👀

This was cute!! Dorian and Anders don’t have a lot of time for sight seeing, but they do their best. Some wining and pining... below the cut or here it is on AO3! --

Friends. That was what they had decided to be. Anders was satisfied with the arrangement in principle, but the problem with being friends with Dorian was… well, everything.

He was sad. Very obviously and very understandably not in a good place. But following that first meeting, he zipped himself right up, kept all that aching intensity to himself. He changed subjects ever and away from his mood, his thoughts, his desires; treating Anders more and more like a casual acquaintance as a distance spread itself, a bit belatedly, between them. They talked about politics, they talked about medicine, they talked about magic, and all the time his flawless hair would shine and his voice would cut through the air with enviable confidence and his hands would bounce about with passion. He was tall and silver-eyed and beautiful, and something in Anders desperately wanted to hold him. But he didn’t — couldn’t. Dorian was hands tied behind his back and perfect posture kept at an insurmountable distance, and Anders wasn’t about to force himself through. Friends. Every now and then, they got coffee. A minute here or there between meetings and rounds. Sometimes late at night, they’d have long conversations over text about everything and nothing at all, and Anders would try to remind himself that on the other side of that screen, Dorian was probably drunk. Emboldened by alcohol and the illusion of anonymity in a text message. The next time Anders saw him, his guard would be back up, and whatever was honest about him would get swept back underneath a thick carpet of sarcasm and flirtation.

And oh, Maker, the flirtation. It wasn’t fair, really; an apostate mage from the gutters of Kirkwall pitted in wordplay against a shining star politician of Tevinter high society. It was like he’d been born to flatter and beguile. Anders had had a reputation for sass, once, as a mouthy lad in the Circle. Later, Isabella and Varric had been fine players to practice a game of wits with, but Dorian was better than silver-tongued, rich with fine words and perfect-teeth-bearing smiles. Varric would have had a field day, mining the man for dialogue. But it was a cold sort of flirtation, more game and art than anything else. He used it with everyone; ordering coffee, thanking store clerks and cab drivers for their time, giving directions to wayward tourists, it was just his way, nothing special. Problem was, each time Dorian flashed that shining, secret-keeping smile at him, Anders felt special. Or wanted to.

“Follow me,” Dorian had met him at their usual coffee shop, standing outside with two paper cups already, Anders’ usual order and his own. He handed him his coffee and turned to march off, motioning Anders along as he headed off fast down the busy street. Anders stumbled to catch up, drinking the coffee as they went.

“I only have an hour,” he warned, brows furrowing as Dorian led them across the avenues in a straight line away from the coffee shop and the nearby hospital. He tossed his own espresso straight back and threw the cup away into the next rubbish bin they passed, pausing to separate the plastic from the paper. A small thing that something in Anders appreciated far too much.

“And I have forty-five minutes,” Dorian tossed him one of those smirks that were not, he repeated to himself, special. “So try to keep up.”

He made a sharp turn down a sloping main street, and then the ocean leapt into view. At the bottom of the hill was a small beach, one of the city’s less crowded, close as it was to the harbour. Great tankers and commercial ships sat heavily in the grey water, blocking the view of a sunny, tropical horizon, as might be found on the wider beaches further up the coast. There was a dog park, and a playground, and several ice cream trucks were sidled up to the curb by an overstuffed parking lot. Children played at the playground and obnoxiously fit people trotted along the walking path that wound around the park and then off along the coast towards those bigger, better beaches. Dorian stopped at the bottom of the hill, toes poking over the edge of the small grassy field of the park where it gave way to gritty brown sand. There were volcanic sand beaches on the islands out at sea, glowing black in the sun a day’s ferry away from the harbour, and clean white beaches spanned long lines of coast away from the city, if one drove the Imperial highway some hours out of town, or took the once-a-day train, but this beach was just brown, smelling a bit of seaweed and city smog amidst the salty breeze and the sun. Anders breathed in deep as the wind whipped up from the ocean, tasting the salt as it mingled with city grime, reminding him a little, but not enough, of home.

“Alright, stand here,” said Dorian, turning and gesturing out, his shoes sinking into the sand, “look out over there, and take this:”

Anders looked out where Dorian had pointed, across a clear swatch of sand and chirping gulls and into the waves, away from the obstructions of wharfs and ships. Dorian reached into his bag — a strappy leather briefcase that had more buckles on it than it could possibly need — and pulled out an entire bottle of red wine. He handed it to Anders.

“There, not quite the view from the cliffs, but it's the air that matters.” He gestured out at the view as Anders warily took the bottle. It was wrapped in thick, textured paper, an elegant script declaring the year and the vineyard over a label designed after a painting of the ocean under a setting sun. Anders looked between the bottle and the horizon, where the sun was just beginning to dip into a red glow. In the painting, the waves washed up against a picturesque bank of rock and sand, not seaweed and seagulls, but the sunset matched. “I can’t imagine you’ll ever find the time to actually get out of the city, so this will have to do.”

Another of those Tevinter must-sees that Anders had scandalized Dorian by having never seen: Tevinter wine country. They’d talked about the importance of wine once, and Anders had been unable to be convinced to appreciate it, much to Dorian’s chagrin. A glass of wine at one of those cliffside vineyards along the coast was, according to Dorian, akin to taking a seat at the very side of the Maker himself. Dorian waved a casual hand over the bottle as Anders held it, loosening the cork so that it slid out with a quiet pop. Anders’ eyes lingered over his fingers as they flicked out this frivolous bit of magic. He was full of little tricks like that, as self-serving and casual with his magic as a Magister was expected to be. Anders could set a bone, but Dorian had a spell for uncorking wine — of course he did.

“I don’t drink,” Anders protested, shaking the image of his dancing hands casting spells under the sunset out of his vision and redirecting his look, with a healthy show of skepticism, at the bottle. “I’m still working.”

“Well, first of all, you’re getting ahead of things. You need to let it have some air, first. Just breathe it in.” Dorian instructed with a nod. Anders shook his head, but wafted a hand over the mouth of the bottle and inhaled, smelling the sea salt and spice.

It smelled good. He wasn’t homesick, with the wine in the air, and the sudden rush of warmth hitting him now felt nothing like Kirkwall. Dorian smiled, watching his face as he inhaled. Deep red of the sunset-stained sea and the dark sweetness of finely aged grapes. Bright teeth and a seductive lean to his lips. He could practically taste it.

“Feel that? Now, one sip won’t kill you.” Anders shook his head again, rolling his eyes.

“I know what wine tastes like.” He had nothing against drinking, it just seemed to filter through him while bypassing all the fun parts. And without that, wine lost most of its appeal.

“You’re Ferelden,” Dorian jabbed back, a continuation of their earlier argument on the subject, “no you don’t.”

Anders sighed and took a sip.

The gulls cawed, a ship’s horn blasted noisily across the harbour, dogs barked and swings creaked and ice cream trucks jingled out their ditties, but Anders wasn’t there. He looked out at the sunset, red across the foaming grey sea and brown sand, and held the wine on his tongue. He leaned back, free hand dropping to his side as he closed his eyes, and let the warmth soak in. Spice and cherry and old smokey oak, smooth and dry and only sweet after it had some time to linger. He swallowed, and passed the bottle back.

Dorian took a sip, and stared out over the water with all those troubles of his, eyes just as tumultuous and grey as the waves themselves as he cast them out into the sunset. Anders felt himself leaning a little closer.

“So? Do you concede?” Dorian asked, too close, after a moment too long.

“It’s good wine,” he took the bottle again, and risked himself one more very small sip before passing it back.

“I told you it mattered,” Dorian took another, larger swig, “the winery, the vintage, the air —”

“The company,” Anders added, winning himself another pleased smile, feeling special.

Dorian leaned back and closed his eyes with one more sip, each drink seeming to draw them a little closer. Anders watched the sun set and filled his lungs with a slow, careful breath of salty air. Down at his side, miles away from his conscious thought, his hand found Dorian’s and brushed against it for all of an instant; just a fleeting rush of heat and giddy inebriation before Dorian’s hand flinched itself away.

Dorian resealed the bottle and packed it back into his briefcase. He grinned with the satisfaction of having won his argument, and walked Anders back up the street with fast strides, bragging about Tevinter wines. They parted ways again at the coffee shop with nothing more than nods and waves.

The flirting was toothless, ordinary; not special. Dorian kept his sad secrets to himself, his flirting all talk. Friends, they’d agreed. Arguments about wine and quick cups of coffee, and sometimes wine-sweetened text messages that were almost vulnerable, after the sun had set.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Any Way the Wind Blows

Chapter 2, complete Word count: 3347

Shasta awoke to disorienting afternoon sun. He was laying on sand, hair salt-stiff, ratty towel under his head like a pillow and a low rusted dome over him like a roof. He blinked, rubbing the sleep from his eyes. Memories from the night before clicked into place like cogs: splashing down the flooded highway, winding his way up the cliffs, crawling into the dilapidated shell of a half-buried pre-Fever car. He rolled over, the back of his shirt caked with sand, and saw the bike wedged between the remains of the back seat and the empty window frame.

His back hurt from sleeping on uneven ground instead of his hammock. His knees were bruised from tipping off the bike on the curves of the road the night before. He didn’t even know why his neck was so sore. But waking undiscovered, safe, and far from home was more than he had expected, and his spirits were light as he rolled over and patted the bike’s dark nav screen. It flickered to life. “Fingerprints accepted. Hello, Shasta.”

“What’s the plan for today?” he yawned.

“Planning in progress. How much food and water did you bring?”

Shasta rifled through the little cargo rack, blinking. “Maybe… two days’ worth? But I have the ration stamp book, so I think we can get more food and fuel at outposts along the way.”

“Until your name and description are distributed for arrest.”

“What?!” He sat up hard, denting the roof of the car and then wincing, rubbing his scalp.

“You do realize that you just stole a valuable piece of imperial loot, don’t you?”

He groaned. “You mean I’m a thief now?”

“You took a stolen item with the intent of returning it to its rightful owner. I would call that noble,” the AI pointed out. “But yes, in the eyes of the empire, you are a criminal.”

Shasta exhaled, blowing his hair from his eyes. “So how are we going to get to the embassy without being caught?”

“The speeder’s communication system was lost in the storm. If you are correct in saying that the fisherman’s radio doesn’t function, it should take a day or two before word reaches a speeder outpost of the theft. After that, it’ll take another day or two for word to spread past Bithersee. That gives us two to four days before outpost officials will know to look out for us.”

Shasta lay back down, interlacing his fingers over his stomach. His legs stuck out through the window of the half-buried car. “The first place they’ll look for me is Bithersee. It’s the closest town, and the only one I’ve been to.” That he remembered, at least. This whole friend-of-Narnia business was stirring up questions of his birthplace that he thought he’d put to rest long ago.

“Will you be recognized if you go into Bithersee, then?”

Shasta considered. “Probably not– the fisherman never let me actually get off the boat. What are you thinking?”

“You know the empire as well as I do, Shasta,” it said. Shasta snorted. By all accounts his ignorance was hard to match. “Help me puzzle through this. You need a disguise that discourages questions, but that explains rapid travel.”

“A speeder, then,” Shasta said immediately. The AI buzzed, processing. “No one questions speeders on imperial business. And that would explain the bike, too.”

“Could you convincingly pretend to be a speeder?”

Shasta closed his eyes, picturing the speeders that travelled the highway over the sunken city. Most were old, with grey-speckled hair and fierce eyes, but he’d seen some young speeders. They had the same air about them– a haughtiness, an awareness of both their surroundings and their importance. And then of course he’d need the scarlet uniform… and boots, and maybe a helmet or headscarf to keep out dust. He imagined himself in speeder robes, shoulders thrown back, chin high. It was all glittering seaspray, a mirage in his mind, of course. But that certainly looked like someone who would get the job done. Someone other people would listen to.

“Yeah,” he said slowly. “I think I could.”

---

Shasta crawled out of the shell of the car, leaving the bike hidden. The distribution center in the middle of town, where citizens and fishermen turned in ration stamps, doubled as the last speeder outpost before the highway crossed the gulf. If any building in town had unused speeder uniforms, it would be that one. But while he could get food and water and fuel, and probably even boots and a headscarf, without raising suspicion, asking for a speeder uniform would certainly draw attention. As soon as the fisherman or the speeder got to town, his description would spread, and anyone with two brain cells to rub together could figure out that the skinny boy needing speeder gear was actually Shasta, motorcycle thief and apparent speeder impersonator. The disguise would be worthless then.

So he kept his head low as he passed the faded city limit sign, wondering how to steal a speeder uniform without being noticed. The spine of Bithersee was a single road, the pavement cracked and faded. Dirt paths curved away like ribs, twisting between scattered huts and disappearing toward the glitter of the distant harbor. In the heart of town stood the distribution center, built on stilts to protect it from the floods that came every storm cycle. A gutter wrapped around the roof, funneling rain water into the community water tank underneath the building. A storm beacon protruded from the roof, but it was off: no storm would come for another two weeks, at least.

He paused, squinting up at the storm beacon. If appearances served, it was the same make as the ones he’d maintained for years: an antenna and a bulbous lightbulb squatting on a control box. An access ladder hung next to the dilapidated wooden stairs that led to the distribution center door. Shasta mounted the steps and knocked.

“Come in,” a woman called. He stepped in, blinking as his eyes adjusted to the dim interior; the only light came from a few windows criss-crossed with narrow boards and tape. The stale smell of sawdust permeated the quiet air. A woman in a sandy-brown uniform sat behind a desk piled with papers and metal trinkets. Aluminum cans were stacked in one corner of the room. There were three doors behind her. “What are you here to collect?” she asked.

“Boots, ma’am,” he said meekly.

“Who are you? I don’t recognize you,” she said, frowning.

His heartbeat stuttered. “Uh– I’m working on one of the fishing boats.”

“Whose?”

Shasta racked his brain for the name of a fisherman his guardian had mentioned in his long, barely coherent market day stories. “Melik?” he tried.

She nodded, apparently satisfied. “He’s getting old, then?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, holding in a sigh of relief. “Needed an extra pair of hands, so here I am.”

“He give you money for the boots, or should I write out an IOU?” she asked. A greedy part of Shasta wanted to put it on poor Melik’s tab, but he knew the panic of unexpected expenses too well to follow through. Good rubber-soled boots cost as much as gasoline for a whole storm cycle.

Instead, he pulled the fisherman’s stamp book from his pocket. “I have ration stamps to exchange.”

The woman held out one hand, fishing through the stacks of papers with the other. “Let me see the stamp book and head into the nonperishable storeroom, then we’ll get you straightened out.” He handed it to her. “Nonperishable door’s that one,” she said, motioning to the door on the far left. Shasta crossed to the door in the center, pulling it open. The room behind contained aisles of food: dented cans, bags of grain, plastic water tanks. This must be the perishable storeroom.

“On your left,” the woman called, still rifling through the forms. Shasta opened the door on the right. The smell of gasoline hit him like a wave. Dark spatters stained the walls; logbooks, bike parts, repair tools and batteries filled a row of shelves; a radio stood in the corner, and a pile of dirty speeder uniforms sat beneath a grimy window.

A hand pushed the door shut. Shasta turned to find the woman behind him, eyebrow lifted. “Other left,” she said.

He smiled sheepishly. “Sorry, ma’am.” He let her push him towards the third door. This room was filled with clothes and construction supplies, as far as he could tell– he rummaged through disordered shelves and bins until he found a pair of boots that were snug on his feet. The woman watched from the doorway as he tried them on, taking a few steps. He’d never had shoes sturdier than sandals; the weight was unfamiliar.

“You want socks to go with those?” she asked, pointing at the next bin. He ducked his head and pulled out a pair of socks, scanning the room for anything else that might be of use. A screwdriver on a nearby shelf caught his eye. He pretended to stumble on the untied laces of his new heavy shoes and bumped into the shelf, grabbing at the screwdriver and sliding it into his pocket. Heart thumping, he pulled off the shoes and returned to the doorway. “Anything else?” she asked.

“No, ma’am.” The screwdriver poked his thigh. Stealing from the empire wasn’t the same as stealing from a random fisherman, he reminded himself, feeling a twinge of guilt regardless. Watching the woman rip out enough gas stamps to fuel the boat for three weeks didn’t help. Shasta had made sure to leave enough food and water to last the fisherman through the next storm cycle at least, but the loss of his gas reserves, his ration stamp book and his source of free labor would hit the fisherman hard.

“Alright, you can take this back to Melik,” she said, handing him the booklet. “Then sign your name here and you’ll be good to go.” She gave him a form and a pen.

He tucked his new boots under one arm and scanned the paper, unable to read it. The fisherman had tried to teach him his letters when he was little, but had given up after a few weeks. The boy didn’t need to read to rake seaweed or fix storm beacons or mend nets. He could write his name and little else, but that would be a dead giveaway of his identity when the speeder came looking. He scratched an X on the dotted line and returned the paper and pen.

After he left, he paused halfway down the steps, pulling on his socks and boots, then turned his attention back to the building. He hadn’t seen any roof access aside from the ladder beside the front door. There were six windows total, three on the north side into the front room, and three on the south side, with one opening into each storeroom. He crept up the stairs on all fours, staying out of sight as he reached the access ladder and began to climb. It creaked under his weight and he froze, then continued up. Hopefully the woman was back at her desk.

This is a terrible plan, Shasta told himself as he reached the roof and crept up the slope towards the storm beacon. Failing more suitable material, the fisherman had tried to teach him to read using the storm beacon manual he got when he was promoted to roadkeeper. That was where he first saw diagrammed the workings of the control panel that he was now opening with the stolen screwdriver. Normally when a storm came, the antenna received a command from some imperial transmitter and the lightbulb began flashing red silently. But if the transmitter failed or a storm hit early, the beacon had an extra trick to alert the town to heightened danger. A manual override– with a siren. Shasta loosened a pair of screws and yanked the lever.

The lever came loose in his hand as an ear-piercing screech split the air. Set the lever on top of the control panel– throw the screws as far as possible– slam the control panel shut– stow the screwdriver. A second later, Shasta scrambled over the ridge of the roof and slid down the south side. The screws bounced off the roof and vanished as he caught his fingers on the gutter, pulling himself to a stop before he followed their fate. He glanced down at the cracked pavement– at least eight meters below his dangling feet– and gulped. This is easier than balancing on the boat in rough seas, he told himself. Just edge a little more to the right… his toes brushed a window ledge. There.

On the other side of the building, the door slammed open and the woman cursed loudly. Shasta lowered himself into a squat on the windowsill, still grasping the gutter with one hand for balance. With the other hand he shoved his screwdriver under the window pane, levering it free. He wiggled his fingers in under the window pane and pulled it up a few inches, pausing to catch his breath. Sweat beaded on his back as he held himself against the window. The access ladder creaked– she was out of the building. The siren continued wailing. He rolled the screwdriver into the room and let go of the gutter to grab the window with both hands, sliding it all the way up with a grunt. His arms ached as he climbed into the room, landing with a thump on the pile of speeder uniforms. He grabbed one, tied it around his waist, and shoved the window shut. Mercifully, the glass muffled the keening of the siren. By now the woman would be struggling to unlock the combination lock. Shasta let himself out of the room and ran to the nonperishable storeroom on the far left and grabbed a coil of rope he’d seen near the door, then went to the perishable storeroom. He knocked over buckets of dried fruit and smashed a jar of precious honey capsules, catching his finger on a shard of glass as he stuffed pills of crystallized honey into his pockets. That should provide a good motive. That done, Shasta knotted one end of the rope around the freshwater tank and yanked the window open. The screaming of the siren returned; he grimaced as he shimmied down the rope. His finger stung. His new boots thumped as they hit the ground.

Shasta stumbled over to the rainwater tank under the distribution center and flopped to the ground beside it, panting. Now he just had to wait until she realized the screws were missing and went back into the distribution center to fetch replacements so he could run without being seen. She wouldn’t search for the culprit until that infernal noise stopped, unless he had drastically misjudged the situation. Which, he thought with slightly hysterical laughter bubbling in his throat, would probably result in immediate arrest and imprisonment while the bike rusted away and Narnia fell. No pressure.

He could still hear the woman’s boots stomping on the roof. Don’t take too long to go back in or some townspeople might come investigate the siren, he thought, the new fear pricking him like broken glass. Sweat trickled down his back, dampening his shirt as he sat against the cool water tank. Were those footsteps coming from the roof or the ground?

A child’s head appeared around the water tank. “Who are you?” Shasta suppressed a yelp, his hand flying out instinctively to quiet the girl. Her eyebrows furrowed. “What are you doing here?” she whispered.

This was bad. This was very not good. He needed a distraction. “Do you like honey?” Shasta whispered. He didn’t know enough about children to guess her age, but she was young, probably waist-high if he were standing, with big curious eyes. He fished a honey capsule from his pocket, holding it out on his open palm. She popped it in her mouth, considering for a moment, then her eyes lit up.

“Yes!”

Shasta let out a relieved breath. If she had grown up at all like him, she had only heard about honey’s sweetness. With bees so rare, it was a luxury she might never taste again. He pulled out a handful of honey capsules. “Will you help me? I need you to go up and tell– wait, stick your head out and tell me if anyone’s coming.” The little girl dutifully looked around the water tank.

“Nope, everyone’s at their house. Like I’m s’posed to be,” she said, grinning.

“You’re supposed to be at home?”

“If I ever heard the big noise,” she said. “But I wanted to come see it first.”

Shasta tried to look stern. “You should definitely go home if you hear that noise again. But this time you’re lucky.” She eyed his handful of honey capsules with bright eyes. “If you go up the stairs and yell at the lady on the roof that you saw a boy inside the building, you can have all of these,” he said. “Deal?”

She nodded quickly, sticking out her hand. Shasta poured the honey capsules– probably more than she could buy if she sold whatever shack she lived in– into her hand and watched them disappear into her pocket. “Tell her there’s a boy inside the building stealing things. And don’t tell her about me, okay? Or the honey. If you tell her about me or the honey you’ll get in trouble.”

“Only say there’s a boy inside the building stealing things,” she repeated, head bobbing, then she ran off. Her bare feet skipped up the steps. Shasta crouched, readying himself to run.

“Lady! Lady, there’s a boy in the building!” Her shrill voice rose above the siren.

“What?” the woman shouted back.

“There’s a boy! In the building! He’s taking stuff and things!” the little girl shrieked. The woman’s response was a wordless cry of frustration. Shasta felt another twinge of guilt. Imperial official or not, he hated to make her job harder. Can’t be helped, he told himself firmly, muscles tensing. The access ladder creaked. A second later, the door slammed. He took off like a shot, new boots flexing and thumping against the dusty pavement. As he ran, he stripped the speeder’s uniform off his waist and bundled it in his arms to hide the bright red fabric. His heart drummed in his chest against his clenched fingers. He crossed the road like a bullet and tore away from the distribution center, kicking up dust as he ran.

He didn’t slow until he was well and truly out of sight of the distribution center, throat and legs on fire, hidden by dunes and rocky plateaus as well as distance. The siren had dropped from a scream to a squeal to a faint whine, and then abruptly stopped. He trudged towards the car, head bent, his prize clutched against his chest. When he finally saw the ruined car where the bike was hidden, he collapsed to the ground and crawled in, not caring that he was rubbing dust all over himself and the uniform. It would add to the authenticity, or something. He needed water. Pulling his plastic canteen from the cargo rack, he gulped down water, letting it run down his chin as he gasped for breath. When he couldn’t drink any more, he slapped his hand against the AI’s nav screen and lowered himself to the ground, groaning.

“Fingerprints identified. Hello, Shasta. I take it you were successful.”

“I almost got caught,” he panted. His heartbeat still pounded in his throat. “AhhhhHHH. I could have gotten life in prison right there.”

“Did you get the disguise?” the AI asked.

“If there had been anyone besides that little girl– if the window had been locked–”

“Did you get the disguise?”

Shasta rolled over, pressing his face against the cool, dusty metal of the fender. A smile stretched his dirt-streaked face. “Yeah, I got the disguise.”

Tagged: @lasaraleen

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Freedom

Link to the first part. Prompt: There he wandered long in a dream of music that turned into running water, and then suddenly into a voice. The leather bag, neatly stitched and marked with the star of his house, was black and stiff, slimy to the touch now but it still held together, for it had been made with skill and care. Maglor pulled it from the coarse pale sand of the seafloor — it always came to rest there, so he could see it clearly — and he swam back towards the light, bursting into cold daylight and taking a breath as his hair clung around his face.

The waves pushed him back to shore, wanting nothing to do with him, and he stumbled from the foam, falling to his knees and pulling the bag open greedily, giving in one more time.

It shone brilliantly, colours of gold and silver out of childhood long lost, and he could not hold himself back from touching it for a moment, though he knew that it would burn him, and it did. The light of everything that he had known and loved would not endure his touch, for he had chosen darkness many times over.

He knelt there for a long while, wide-eyed in silence, enspelled by the Oath that bound him to the light that condemned him.

His body reminded him that the gravel beneath his knees was sharp, the wind was cold and his stomach empty. He ignored it at first, but it protested more sharply as the grey light in the sky began to fade, and he found himself shaking. Eventually he pulled himself away, got up stiffly, stretched and pulled his more or less dry cloak around him.

He left the gem lying on the rock where he could see it from the corner of his eye.

There was little food to be found along the shoreline that had until recently been the east-border of Beleriand. Celegorm would have found something easily enough, of course, but Celegorm was buried in a shallow grave scratched into the iron-hard midwinter soil outside Menegroth, out there somewhere beneath the Sea. But where the fires that had blazed from the rocks had guttered and died leaving only black ash, willowherb had sprung up, blushing tall and fair, coming down almost to the shoreline, and wild carrots followed. Amrod had told him that you could eat the willowherb, and how to tell wild carrots from the hemlock...

Maglor pulled up roots one-handed, keeping half an eye on the Silmaril as he did it. He had dazzled the Oath into silence with light for now, and so he could glance at it sideways and not be caught.

He washed the roots in seawater, added a few small mussels and handfuls of a delicate green seaweed to the pan that had been in the pack that Maedhros had abandoned on the rock, and climbed back up with them to the Silmaril to make a fire. Maedhros had carried more gear than he, since Maglor had the harp to carry... The willowherb made good kindling: Amrod had showed him that, too.

It was easier when the Silmaril was in the ocean. When the gem was there beside him, the Oath pushed at him to look at it, to wonder if it was safe, to think dark thoughts of what he might do to anyone who came to take it from him. But he could not bear to leave it in the Sea for long either.

“I should have thrown you into the fires before they went cold,” he told it bitterly, though he knew that was not something he could do. Not after Dagor Bragollach, and the rivers of fire that had taken so many friends and allies, not after Glaurung blazing in fury at Nirnaeth Arnoediad, after Ancalagon the Black belching flame across the sky.

Perhaps the Silmaril knew it too: at any rate it did not reply. It never did. He was not sure if he wanted it to reply in his father’s voice, or if he was afraid that if it did, it would speak of Eldar and of Aftercomers who had taken in hand a Silmaril.

Probably he should have taken the path that Maedhros had taken, whether that path led to the Halls of Awaiting or to the Everlasting Darkness to which they had pledged themselves. But that was not something he had been able to bring himself to do either. The treacherous voice of hope would not let him, and anyway it was Maedhros who was the brave one. Maedhros and Celegorm and Caranthir, and Maglor standing next to them, pretending that he was brave, too. If he had been brave, he would have stood with Maedhros at Losgar. But probably that would not have changed anything.

The clouds were clearing at last into the west, leaving a faint red afterglow of the vanished sunset, and stars appearing. The evening star shone in the west, echoing the light of the Silmaril. It was distant now, impossible to pick out as the ship that had slain the greatest of the Winged Dragons. Gil-Estel they had called it when first they saw it, the Star of High Hope, and that hope had proved true for almost everyone.

“It was a true hope, really,” Maglor said to Eärendil, taking a sip of thin hot salty mussel soup. “Our Enemy fell, and that was supposed to be the point. I would be honestly happy to consider you one of Fëanor’s kin and entitled to the thing that way. I suppose it’s too much to expect that you should feel the same.”

Eärendil, high in the western sky, made no answer. He was probably busy with more important matters than conversation with a lost and wandering distant cousin who had been declared an enemy both by his acts and by his Silmaril.

“No?” Maglor said. “Ah well. I don’t suppose my father would either.” He scooped a mussel from the pan. Maedhros had packed three spoons, and he wondered again if that meant that Maedhros had not planned his death all along, and who the third spoon had been for: Fingon, or their father. Or perhaps it was just a spare spoon.

The soup was finished: enough to silence the protests of his body for a little while, and so he cautiously pulled the harp from its leather cover with his left hand. He had touched the Silmaril with two fingertips this time, like a fool. Fingertip burns were the worst kind.

He turned his back upon the Silmaril, settled the harp on his knee, balanced it carefully in the crook of his right arm, well away from his aching hand, and began to play one-handed, thoughtlessly, wandering into a dream made of music as he let the notes spill out unplanned and fall like golden light of Laurelin through rain, down to the endlessly surging sea.

#maglor#silmarillion#b2mem#I'm really not doing this#honestly I was working#LIES#maglor is one of the least qualified brothers to feed himself#he could be doing much worse.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

47

A storm journeyed over Old Ebonheart and its first herald was rain.

Gutters overflowed and water crashed from the rooftops. The streets below were in flood, in flow, adrift with a scum of forgotten things. Dry leaves leftover from Autumn, winkled out of the corners they’d hid in. An enamelled tray, painted with a pattern of an ocean bed, with weeds framing the ripples and fish-shoals it showed underwater — a sea within a sea. Buckets and cups, wooden tableware, vessels of clay and glass.

From the hang of a balcony I fished into the flowpast sometimes, trying to snag what I could with a shopkeep’s weight attached to the end of a rope. I didn’t catch much. I wondered about walking the rooftops til I got to the waterfront; exploring the piers and warehouses to see if I might find a fisherman’s hook, a dockworker’s gaffe, a netchiman’s staff — something better suited to this new kind of fishing. But I had seen lights along the docks by night, and the drift of shouts and music, and wasn’t ready to brave it. In the main I watched things go by. I presumed at least the things I didn’t catch would end up at the harbour and out to sea, even if I didn’t. Old Ebonheart, I thought, getting leaner down the years as the weather washed it clean, and the pickers in the ruins ate up its scraps.

I saw papers go by, and scrolls, and tablets of wax and slate. They were the worst of the things I couldn’t catch. Just bills, probably, and contracts, or lists of things no longer needful. Still it thistled at me to see ink run and paper go to waste. Words lost, and curiosity gone to a strange fool sadness.

But the storm took more than the things it showed me, but wouldn’t let me keep. Wind and cold screamed in the high places and drove me from the warehouse tower. Rain flooded the colour shop in water the colour of mud, and I waded in, knee-deep, to save what I could from the damp. The sea surged on the long grey horizon and the spray of it rose spire-high, finally showing me why I had found saltlicks and dead seaweed even in the city’s highest heights. And in the clutch of the storm, all the shelter left to me was the dyery, the factor’s pits. So I buried myself there, where the air, the dust, the long-caked colours were always dark and dry, and I still had a chance at staying warm.

A heavy roof overhead, but still I heard the rain on it. Felt the thunder, as much from below as above, like it shook the earth with its every shout. Hid as I was, I braved a fire, and sat blinking from its thin close smoke, watching the dustmotes dance gold by its light. And I wondered, is that rain I hear, or the first hungry waves, tall as high towers, come to swamp and swallow and topple the city for good? The night was cold and creeping, beneath the hammering storm, and I feared what I would wake to when daylight came again.

And that was where Tepa found me. Perhaps they’d tracked me. Waited, biding their time. In the tower I’d have been safe from them but not from the storm. In the colour shop I might have had space on my side, and the rusty grate’s shriek of warning. Here I wasn’t so safe. A badger tracked down its hole, and the hounds on the way. Perhaps it was all planning on Tepa’s part, or perhaps they got lucky as my luck failed. Anycase, they’d scented me out. Though the storm had kept me awake, or sleeping light, it masked the sound of their coming. Too late by then. Close and loud and coming.

The click and crackle of nix came through the dyery, hard to tell at first from the snap and wheeze of my fire. Wet wood, complaining as it took the flame. Then the boiling whistle through their shells as they breathed quick, sharing their eagerness out through the pack. And beneath that, the shuffling feet and shudder-hissing breath of someone cold, moving more than they need to, all for the sake of warmth.

I thrashed free of my bedding. A tangle of legs and arms, then a creature of hands and knees, and hearthdust grit on my skin. I scrabbled amongst the things I’d gathered – jars and baskets; bottles and bags – finding my feet, finding my knife, any knife. Hearing all the while the shuffle of footsteps, the creak and hiss of carapace and long air-tasting tongues. I touched fingers to steel. The familiar cloth-wrapped handle of my spearhead knife, and the metal warm from living close to my skin.

“Hey, Firecaller..?”

I froze in a crouch, still as a crab in a pot-trap’s belly, waiting for the fisher to come. The voice was Tepa’s: hissing one moment and wet the next, clumsy at the corners, as if tripping from a tongue too thin to shape the words. They were speaking Tamrielic.

“Hey now. Hey!” Not words for me anymore. The scuffle of a nix-hound’s sharp small feet on the workshop floor. A pop and whining trill. “You’ve done your job. Now be easy… See, Dunmer? They’re not here to hurt you. Nor me. Just to find you.”

Their face showed over the edge of the pit. A strange round newt-face, spread between two wide unblinking eyes, bulging and black and far-set from each other. The smooth sleek skin of something unused to being too long dry, motleyed in pale greys and clouds and spatters of blue and sullen red, all drenched in rain and chased with firelit gold. Spines so thin they looked like feathers and moved like grass, fanning around their neck.

I didn’t straighten. Only stared up, face still half-fixed to snarl. But my fingers unstilled themselves, twitching on the handle of my knife. “You corner me. Come in the night. And you expect me to believe…”

“Yes, yes, yes,” Tepa chattered. “That I haven’t come to kill you? Hard to believe, but wouldn’t you rather believe it?”

One of the nix whistled again, and settled into a kind of rattling purr. Tongue searching the air, it looked down the pit at me, staring curious out of its eyeless long muzzle of a face. It had a strike of yellow daubed onto the hump of shell where head met shoulders. My eyes raced from Tepa to the nix and back.

Tepa settled first into a squat, moving strange and boneless, like every action was a kind of bending. Then they sat on the edge of the factor pit. Legs bundled in layers of hide and cloth all bound and wrapped eachover with rope. They swung their feet in the empty air and held out their empty hands. Clumpy mittens, three long and pad-tipped fingers and a thumb sticking blue-grey out of each.

“I saw what you did to Guls. Found what you did to Drosi. Think I want to chance what you could do to my hide, my hounds? I’d rather not. I’d rather, really rather not.”

“Wise of you,” I glared. “But way I see it, you’re still chancing it.” All thunder and no lightning, though. Half-starved and tired and cold for so long I’d not been on talking terms with my toes for weeks, I had no chance against Tepa and two nix. Not with nothing but a knife, and magic I was half-sure would kill me if I reached for it. “Must have a good reason.”

A kind of gurgling hum from somewhere inside Tepa’s head. The other nix, head-hump splashed with blue, peered over the edge of the pit and then slumped down, muzzle in Tepa’s lap and mouthparts chewing the air. Be easy, Tepa had said. “I brought fish,” they said now.

I blinked. Let myself, for what felt like the first time in a long and breathless stretch of staring. “What?”

“Catshark, salted. Got any milk? It’s good boiled in milk, I swear.”

Tepa slouched down from the ledge and into the pit. I flinched back, skittering away till I stubbed my heels on my jars, my sacks, my baggage.

“What’s that face?” Tepa asked. “Talk with words, Dunmer. Can’t read you people.”

“I killed your friends…”

“People I lived with,” Tepa corrected me. “Worked and ate with. Does that mean fondness? Tsscheh. My heart beats just fine without Drosi or Guls. They were closer friends with each other than they ever were to me. The mine though — I can farm that alone, fine, fine, more eating for me. But keep it? Guard it? No. No, I can’t. And you?” That head-deep hum once again. I wondered if it was something like a smile. “You seem good enough at threats. Murder. And you speak Dunmer, I think. You do, don’t you? Speak it?”

My belly growled, rattling empty, like the bezoar at the bottom of a finished sujamma flask. I nodded. “You came for help, then?”

“To ask and offer,” Tepa gave me back a vigorous nod. “No one stays alive long in Old Ebonheart without a tong. Don’t have things, you starve. Have things, you’ll die soon as someone stronger wants them. But with a tong..? Things stay still. Safe. You killed mine, and don’t have one yourself. The rest’s just common sense. Fish?”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m reblogging so this is easier to use! But here are some potential ideas? Let me know if these suit you! I’ll also link some resources ^^ but honestly I find eliminating what Google considers “buzzwords” to help. So instead of, in your case, putting in the terms autism or sensory issues which will pull up warrior mommy articles (sadly) I googled “crunchy healthy meals” because then Google just sees that you’re looking for recipes that don’t feel like slop. It’s kinda sad it works that way, but it helps

Food ideas

Kale chips (lots of variants and super easy!)

Here’s a link to a bunch of mostly easy recipes and ideas you can cook that are for snacking, including crunchy chickpeas, avocado fries, and cauliflower tater tots which are supposed to be really crispy :)

Some products (depending on your tastes and sensitivity) that might be good are roasted edamame, dried seaweed, cauliflower crisps, and sometimes Costco has these amazing almonds covered in lemon chocolate called Lemoncello Almonds and they are to die for. They sell a lot of crunchy foods in bulk! Including chocolate covered blueberries

As for meals, I found Buffalo cauliflower is really good. It doesn’t taste much like cauliflower and more like hot wings, and it has Crunch

Also potato pancakes, which are like hash browns but cool. They pair well with ham steaks if you eat meat! Though those can be a little greasy if you’re not careful

Let me know if im on the right track! My reading comprehension is in the gutter right now unfortunately

Me: *tries to research food options for autistic people who have trouble eating food with certain textures because I want to expand my diet*

The shit that pops up: "HOW to help your CRYING KID with AUTISM eat FOOOD!""A list of FOODS that make AUTISM WORSE""AUTISM SPEAKS"

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

I GET MY FIRST SOCIAL SECURITY CHECK TOMORROW

I have heard the term southern hospitality my whole life. It is true! This past week proof.

Jean and Joe the most hospitable without question. Opened their home, refrigerator, etc. to us. Jean just took my dirty clothes and threw them in the washer.

They can never be repaid. Nor do they expect it. They will be remembered, however.

Then there are Jean’s neighbors. Three full dinner meals prepared. Desserts and breakfast food. Even a few bottles of booze and wine.

All because they were friends of Jean and Joe and felt sorry for us.

Last night’s benefactor was Cindy. A cheerful woman. Widowed some 40 years. Prepared Greek chicken and accompanying dishes. Outstanding!

Cindy a die hard Democrat. Hard to find in this Republican state. Very outspoken in her opposition to Trump and Republicans. Loved her!

Cindy was all excited. She told us that tomorrow (today) she would receive her first Social Security check. An event! I recall when I received my first. A return on something you paid for and had to wait a long time to receive.

We ran out of wine at dinner. Eight bottles.

This hurricane evacuation thing is emotional. Very much so. All of us are just coming down. The knowledge Irma did not hit Key West as hard as expected, the knowledge that our homes sustained little damage helps.

Peter Petro called me last night. We now have cell phone service. He is the realtor who takes care of my home. I lost 3 trees. Two in front and one in the back. A dented rain gutter. No water damage. House stinks because I left food in the freezer and refrigerator.

Talked with Anna this morning. The roads in Key West itself are open. She is going to the house today to clean out the freezer and refrigerator.

Spoke with Lisa last night. Still in Jupiter. Their home looks ok. From the air. Roof still on.

The family’s first report was from two of Ally’s girl friends. Note Ally and the girl friends are in the seventh grade and 12 years old. The two young ladies walked over to Ally’s house, checked things out and reported to Ally everything looked ok.

There is humor in tragedy.

Mark Watson reported on Facebook this morning that “I got to sleep butt ass naked in a/c…..I lived like a free man!”

Key West has a For Sale column that runs daily on Facebook. free. Someone from Ramrod Key advertised yesterday…..House for sale free. A picture accompanied the ad. The home totally destroyed. Flat on the ground.

Tragedy without humor, also.

Carol Schreck lives on a 53′ Defever trawler docked at the Key West Yacht Club. The vessel sunk in its slip. Even though Carol and friends securely tied it to posts, etc.

Carol had planned to stay. Her boat strong and properly secured. Fortunate she did not.

The boat began jumping around when Irma hit. A few men from the Yacht Club jumped in the water to further secure it. Could not. The water too rough. Dangerous. Had to get out.

The Garrison Bight Pier is roughly a quarter a mile away across the inlet. Carole’s trawler has large pieces of concrete jetty material attached or in the trawler which it is assumed came from the Garrison Bight job.

Hers was the only boat to sink at the Yacht Club.

I have a negative comment to retract.

I mentioned a few days ago that people were lighting candles at the St. Mary of the Sea outdoor Grotto. Tradition tells us praying and lighting candles at the Grotto will prevent significant storm damage to Key West.

Many prayed once again. I questioned and doubted.

I have read several reports today where persons attribute the lack of bad damage to Key West to the candle lighting and praying.

Maybe it works. Real devastation was only 15 and 25 miles away in Cudjoe and Big Pine

I plan on visiting the Grotto, lighting a candle and saying a prayer of thanks when I return.

I suspect I will not be leaving till monday. Perhaps later.

Power presently limited to 16 percent of Key West. Water limited to 4 hours a day. Must be boiled. Medical services available on a very limited basis at the Community College. Hospital still closed. Search and rescue on Cudjoe Key and Big Pine still ongoing. Only food is that government is bringing in. Stores still closed. a few gas stations open. Curfew dusk to dawn continues. Call service spotty. AT&T and Verizon up and running.

Perhaps the worst problem from a practical perspective is the stink. Got a call this morning. Told don’t hurry home. Key West stinks! Seaweed, fish, garbage and trash all over. Waste Management not able to clean yet.

Cathy Hakola wrote me yesterday. Facebook, I believe. Told an interesting story. I cannot find it this morning to recite in detail and correctness as received.

Her story has to do with ghosts. Key West has several ghost stories. Most probably false. I suspect a couple true.

One of the true ones involves the Gato House which once was a hospital. Now an apartment house.

Cathy a nurse. A nurse who also rented an apartment in the Gato House after the hospital closed.

History tells us the hospital was run by a very dedicated nurse. Well respected by all.

The claim is her ghost still resides in the Gato House.

Cathy was sick. She woke in the middle of the night to discover someone holding her hand and rubbing her arm. A woman. The ghost.

This went on for several minutes. Cathy says she was not afraid. Found the episode comforting. Woke the next morning much better.

Enjoy your day!

I GET MY FIRST SOCIAL SECURITY CHECK TOMORROW was originally published on Key West Lou

#53' Defever Trawler#Ally#Anna#Blessed Virgin#Carol Schreck#Cathy Hakola#Cindy#Facebook#Gato House#German Jews#Grotto#Irma Emotional#Key West#Key West Lou#Key West Lou Blog Talk Radio#Key West Lou COMMENTARY#Key West Lou Live#Key West Lou Live Video#Key West Update#Key West Yacht Club#Lisa#Mark Watson#Naples Estates#Netanyahu#Nuemberg#Peter Petro#Ramrod Key#St. Mary's of the Sea#Subjects of the State#Trump and Pruett

0 notes

Text

Terror At Castle Pyke

The Damphair gets closer to the Drowned God.

“I hope you have not taken me from my sacred duties that you might read to me.”

Rodrik Harlaw glanced up from the scroll before him long enough to cast a wry look his way. “I would not have requested you here if I did not think my reading would interest you, Damphair,” he replied politely. Aeron remained unconvinced, yet he sat down opposite the Reader nonetheless.

He did not oft visit Ten Towers; the people of the area, large and small, seemed to have little interest in the Drowned God. The castle’s lord was the worst of them in his opinion, a man who would squint over dusty papers while his Sea Song gathered barnacles and algae. Still, he felt a certain obligation to answer the Reader’s call, if only to press the weight of his judgment upon the man.

“I found an interesting treatise from Archmaester Haereg from before he reversed his stance in his History of the Ironborn,” he continued, speaking as though the priest was as familiar with the text as he. “He had theorized that our people came of adventurers from across the Sunset Sea, even before the First Men crossed the arm of Dorne.”

Aeron frowned. “He sounds as mad as the Farwynd of Lonely Light,” he replied flatly. “We came from the sea, by the grace of God.” What did this man hope to accomplish, repeating the words of some long-dead green land scholar? My faith is not so fragile as that. Your words will not stir me.

Lord Harlaw seemed to ignore the comment. “I found a rare scroll in our libraries, where Haereg once expounded on this. He lent credence to old Maester Theron’s writings, saying that these men from the west found an old race of beings living on the Isles, who were scaly like fish, hewed their homes from chunks of black stone, and worshiped titanic creatures from the sea.

“He disputed Theron’s account of this interaction, however. Haereg seemed to believe that the men from the Sunset Sea had put these so-called Deep Ones to the sword, slaughtering the men and taking their women as concubines. They even tore down their stone houses and cast the rubble into the sea. Afterward, their dispositions seemed to change, and they began to revere what little was left of the Deep Ones’ culture.”

Aeron was losing patience quickly. “The theories of milk-veined men from the Citadel are as nothing to me,” he interjected bluntly, picking at a splinter on the desk before him. “If there is nothing else, Reader, I will be leaving.”

“Both men were Ironborn by birth,” the Harlaw replied, placid as ever, “but that is neither here or there.” He unrolled another scroll, this one drier than the rest, and indicated a passage near the center. “Haereg cites the Seastone Chair as evidence for this theory. He said it was found on Old Wyk, but was later brought to Pyke, where a castle was built in its honor.

“’A task in the name of the Deep Ones’ God,’ he called it, ‘to rest the Chair above a holy site deep within the grottoes of the isle.’ It is not clear where this idea came from, but he did propose a thorough excavation of Castle Pyke, to determine the veracity of his research. These fell through, however, due to lack of funding from the Citadel and writ of refusal from Talon Greyjoy, the Lord of Pyke at the time. Haereg later gave up on these notions and returned to the popular belief of First Men ancestry.”

The older man met Aeron’s eyes, raising his brows expectantly. He offered a grimace in return. “What is it you want of me, Reader? Your facts are at odds. Old Wyk is the holiest site of the Isles, and where the Seastone Chair remained until the Grey King’s eldest son took it to Pyke for his own seat. Even the simplest child knows this. I wish to hear no more of your nonsense; it draws near to sacrilege.” He gave the lord a cold look, one he had used to chastise thrall and captain alike.

Yet Rodrik stared back at him, unaffected. “I simply wanted to tell you of it,” he replied calmly, “and to hear what your thoughts were on the matter. I am sorry to have wasted your time, Damphair. You are welcome to take supper in my hall this night if you wish, and there are beds available should you want to depart by morning.”

He has reverence enough to be courteous, Aeron decided and he accepted the offer with hollow gratitude. He thought no more of Deep Ones or seafarers from the west that night, nor the next day when he departed the castle to return to the work of a Drowned Priest.

As the days passed, however, some of the words they exchanged in the Book Tower came back to him. They resonated in some of his litanies by day and framed his dreams by night. What started as a chill in the air of his mind grew to a howling gale by a moon’s turn. It was then that he found himself boarding a ship to return him to the Lordsport of Pyke.

The Reader is a fool and I am more a fool in heeding him, the man thought sourly. He waved away a Drowned Man who offered him a horse and walked to the castle of his birth. Gulls screeched, rocks bit into his bare feet, and the melange of salt and rotting seaweed filled the air, but the Damphair was lost in his thoughts. I do this only to prove that he has grown mad and soft in his tower, Aeron promised, the Drowned God has shown me the truth one thousand times over.

Helya, the wizened steward, found him not long after entering the Great Keep. “What an honor to have a Drowned Priest in our halls again,” she called upon seeing him, her voice as creaky as the planks of an old ship. “Shall I escort you to m’lord’s solar?”

“No,” Aeron said swiftly, waving her away. Before she could hobble out of the antechamber, however, he called, “I would... I would rather you not let the Lord Reaper know that I am here.” The last thing he wanted was for Balon to chide him as though he were still the young lout he had been in another life.

The Great Keep’s basements yielded little other than mildew and crabs. They were as dark and wet and empty as he expected. Aeron permitted himself a smile as he imagined an army of maesters crawling through the dark like the grey rats they were. “Nothing is here,” he called mockingly into the unused halls. Nothing answered.

From there, Aeron crossed the stone walkway that led into the Bloody Keep, scowling thralls and guards alike into silence. The corridors of this section were lit as poorly as the Great Keep’s underchambers and the walls were padded with grey-green lichen. Its very existence had puzzled him as a boy. He had once asked his father why the greatest and richest of their island keeps was left unused. “The Hoares broke guest right in this keep,” his father had replied, “and the foulness hangs over its halls like sea-fog.” It was hardly an answer, and certainly not something their ancestors would have cared about.

The Damphair took a torch from a sconce and descended a staircase into the depths of the keep. The damned thing had nearly guttered out twice has he caught it on the layers of damp cobweb that festooned the ceiling, and he had stopped as many times, wondering why he continued. Nothing will be there, he told himself, why do I press on? Yet down he descended until it seemed that light and sound alike were swallowed by the darkness. There he found an oaken door fixed with a rusted iron handle.

Though the door was almost white with rot, he could discern impressions of what had once ben intricate carving. The full design had been lost to time, but elements of it still remained: stretching arms of a Kraken, the long legs of a spider crab, a face twisted half in agony and half in ecstasy. He opened the door slowly and was startled despite himself at the closeness of the wall on the other side. Beyond the doorway stretched a mere five feet of hallway before it turned right sharply into the next corridor.

Aeron entered the hall and turned, allowing the door to close on its own. Its hinges protested with a sound that made him feel nauseous with recollection. His pace quickened as he walked down the short passage and turned right again.

Another short corridor, another sharp right turn.

He kept walking and turning, turning and walking, until his senses caught up with him. Why have I continued to follow this path, the prophet wondered again, angry at himself. Why have I entertained this madness for even this long? How many times have I rounded a corner: three, or thirty?

Aeron’s sense told him to abandon this folly and never give it life again, and yet he found himself peeking around the corner all the same. Instead of yet another hall, a door terminated the path. This one was well kept, dark with many layers of varnish. The carvings were clear-cut and exquisite here, depicting a scene out of a nightmare.

A giant crab, a Kraken, and two beasts that the Damphair could not identify stood around a man. One of the unknown appeared as a sickening mass of fins and flippers, while the other was a sort of serpent with the rubbery wings of a ray and a brutal, serrated tail. Each of them had a limb of the man in their grasp, seeming to pull him apart. The man was naked and covered in scales, and his face was the grotesque mask he had seen previously. This time, however, the features were better-defined and far more unsettling. The sea monsters had faces of their own, though they looked neither human nor bestial.

“I must turn back,” the Greyjoy said loudly to himself, but his hand was on the door handle and he was pulling it back. A blast of cold, wet, salty air invigorated him as he faced yet another deep staircase. This one spiraled on and on, but a dull roar and a dim green glow lay waiting at the foot. The sea, he thought with relief, I have found the sea again.

Aeron nearly skipped down the ancient stone steps, all but deaf to the door slamming shut behind him. The waters of Pyke were close enough to taste now, and he would rather swim to the shore than make his way through that hellish maze of stone. I will brand Rodrik Harlaw a dangerous madman for this, he promised.

His excitement twisted into confusion as he found the end of the staircase. Before him yawned an expansive grotto, with walls of black stone that seemed to melt into the darkness beyond. What he had thought was the reflection of sunlight off of the water was the water itself, casting a queer green light that came from nowhere and everywhere at once. It clung to the stones in such a way that they appeared oily and vile as if dripping with some dark humor.

The roar that Aeron had heard from the top of the stairs had grown into a whirlwind of sound at the grotto’s shore, but it was not the call of the sea. In fact, the glowing waters seemed as still as glass. The cacophony was punctuated with clicks and wet squelches and other sounds that he could not name. Everything about this place is wrong, he thought with disquiet, I should never have come. He turned to track back up the staircase...

But the staircase wasn’t there.

He glanced around frantically, but only glistening stone walls greeted him. The fear sunk in then; worse than it had in his youth and even worse than it had during his drowning. “The Drowned God is with me,” he called into the howling cavern, closing his eyes. “I am by His waters, below His isle, nothing can hurt me.” He opened his eyes anew. Still, no staircase.

Folded within the layers of noise was a slithering, soft and subtle. The priest whipped his head around to locate the source. The green pool had been disturbed, shallow ripples reaching out to the cave walls. He heard the slithering sound again, and a small crop of bubbles rose lazily from the lit depths.

It was more than he could take: Aeron began to sprint across the stone, groping the nearest jutting rock to climb. It was no easy feat, for the profane outcrops were as slippery as they looked. Bare hands and feet scrambled along the smooth surface as he tried to bring himself higher, away from the terrible unknown. He had almost reached a black cliff that hung above the rippling lake when his foot caught on something.

It was a hand.

The hand was an eldritch thing: black, cracked nails on spindly, webbed fingers covered in grey, squamous skin. It was attached to an arm, similarly grey and scaly, from which hung a loose membrane of leathery skin. The appendage was emaciated, yet it held fast to him with an uncanny strength that he could not shake off. It was hideous, yet human enough to appear all the more unnatural.

“Unhand me!” Aeron spat. “I am a servant of the Drowned God!” The hand and its owner took no heed of his words and pulled all the harder. He clung desperately to the rocks and begun to strike his captured limb against the wall in a last-ditch effort to escape. His flailing was savage enough to maim himself and the creature alike, and his own red blood trickled down to mingle with the matte grey life-fluid of his assailant.

Finally, with a final violent jerk, he managed to crush its fingers between his heel and the wall with a sound like the snapping of a soggy carrot. Agony shot up Aeron’s leg and he almost fell from his tenuous hold, but the hand had relinquished its vice grip and retreated into the murky glow. Without sparing another thought, the Damphair continued his climb, hands scrambling desperately for purchase until he had lifted himself enough to see over the cliff.

“Please, Drowned God, no...”

Nine of the manbeasts crouched in wait for him at the top of the cliff, dragging him up and casting a net over him. Their legs were as fishlike as their arms, and terminated in two meaty flippers, not unlike the hind parts of a seal. Their torsos were mottled and scaly, sexless and naked save for patches of slimy barnacles that waved their vermiform innards in the open air.

The worst of them was the faces. They were stretched over thin yet protruding skulls, with flat, glassy eyes and pouting, rubbery lips. They had no nose save for slits that seemed to run from just under the eyes all the way to their necks, where ruffly, blue exposed gills opened and closed with a gentle sucking sound. From the tops of their heads hung whiplike tendrils that ended in greasy bulbs that seemed to pulse and shimmer with the same green light that illuminated the waters below.

They were chattering in some obscene tongue, all popping lips and gurgling throats, as they carried him through a passage atop the cliff. Aeron thrashed and struggled, but his limbs were tangled in the wet, leathery ropes of the net. “You must be the Deep Ones!” he cried out to them. “Your God and my own are the same, it is said! I am his priest, we have no quarrel!.”

If they could understand him, they made no indication. The beings kept moving forward, down and down until they reached a capacious chamber. It was ringed with torches that burned blue and green, fixed to the walls in sconces made of pale coral, though one had no flame. Beside each torch were seats made of the same oily black stone that comprised the grotto, where more of the deep denizens had perched themselves. The thrones were carved in the likeness of malformed sea creatures; he could see a razor conch, a horned whale, and others too frightening to guess at. The unlit brand had no chair to accompany it, and the absence filled him with dreadful realization. At the center of the room was a well, simple and austere. “What are you doing?” the Damphair screeched. “What will you do to me?!”

They approached the well and unfurled the net. Four of them descended upon him, each grabbing a limb as they lifted him over the mouth of the well and chanted in their profane tongue. He continued to scream and thrash, ropes of his hair whipping against his captors. Aeron could feel the rim against his wrists and ankles; he knew what then these Deep Ones would do. “No! No! Noooo!” he pleaded. The well cast his supplications back up at him from its wet and hollow throat.

Suddenly, the chanting stopped, and his terror was the only sound. One of the observers came forth and stood over him. It was wearing a necklace of brown, fetid seaweed, and looked to be leader or priest to the others. It raked a single black talon along Aeron’s side, ripping the fabric of his robe, and then removed it. He was exposed, save for his breechclout, and he could feel the moist current from below him.

The leader whispered something to the others, and Aeron fell.

He was momentarily stunned by the impact of the water's surface, and it washed into his open mouth. His eyes stung and his stomach knotted from the bitter salinity. You are drowning, a voice somewhere deep within him called, but it brought him no comfort. He sunk like one chained to an anchor, even as he flailed his arms upward. Further and further he dropped until caliginosity became illumination, and sea became air.

The change shocked his senses, and it felt like an age before he had come to. The priest found himself suspended in liquid as viscous as jelly, yet his lungs took the medium in and out. There was no time to find comfort in this, however, for he discovered that he was not alone. Caught in the pulp with him were other men, other bodies. Some wore iron armor, others were as naked as he, and a few even had crowns of driftwood floating near them. All shared one thing in common: faces that were contorted into an abhorrent expression of dread and anguish and exultation. It was terribly familiar to Aeron.

In the brown haze of this man-trap, a shadow began to grow. Amorphous and distant at first, it began to take shape and grow until only his periphery remained uneclipsed. It was a monstrous shade, rippling with limbs that belonged to man and beast and beings unknowable. It glided forward with a gravity that jostled the Damphair like a fly in a web. He wanted to shut his eyes, to die quietly and avoid whatever fate had befallen the corpses around him, but he found his eyelids pinned open.

And then he saw its face.

It was to look into his brother’s black eye. To gaze into the center of a maelstrom. To peer into the abyssal depths even further than where Krakens and leviathans dwell. The thing wrapped one long tentacle around his legs and it was then that he knew. This is the Watery Hall. This is the Drowned God. He screamed, his face warping from the exertion, but no sound came out.

He was discovered by a group of Drowned Men, who were preparing to commune with their God on the shores of Iron Holt. It had been three days since anyone had seen the Damphair last, and most had assumed him dead, carried off by the high tide during one of his long reflections beyond the shore. He was half a corpse, as cold and blue as the sea, but he spat up water and seaweed and substances more unsavory after one of his own gave the Kiss of Life. His face had been a nightmare to look upon in that moment, but it suddenly slackened, and Aeron Greyjoy gazed cheerfully around him.

“Where were you, Damphair?” One among them asked. “We had looked for you for some time. No one knew-”

“Under the sea, the fish catch men in their nets,” he interrupted, turning the words into a sort of lilting song. “I know, I know! Oh, oh, oh!”

#The Damphair [Aeron POV]#aeron greyjoy#tw: cosmic horror#anyone who reads this deserves a cookie#but this was fun to write

1 note

·

View note

Text

Survivor on her pearl hunting journey is too scared to admit she found another family in fear of losing it again on the way back hehe

I've been pearl hunting with those rascals for so long dear god. Their names are Beach ball (round light blue pup) and Seaweed (dark green)

#rainworld#rain world#my art#rw survivor#looks to the moon#this was a lil fun fun break comic#phew#i love drawing pups so much#theyre just cute lil balls#i found beach ball first and had him for a long while#and i found seaweed in the gutter#motherhood is so scary but we ball#poor moon has witnessed me go back and ffourth with these twerps sooo many times

789 notes

·

View notes