#i cried at the 2016 elections and stayed up late as if I WERE AMERICAN i aint going back to that lvl of brainrot no siree

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I posted a crime and punishment meme on instagram stories and this girl legit commented in my dm like kamala/trump?? like broo the usamerican brainrot is strong with this one shes balkan what are u doingg its not 2016 anymore we arent beholden to their politics focus on our own shitstarters in our own country like damnn.

#i cried at the 2016 elections and stayed up late as if I WERE AMERICAN i aint going back to that lvl of brainrot no siree#i am only looking at our politics#kamala trump?? what about df pokret evropa sad ii#actual.things that are going to affect my day to day#like holy shittt i need to apologise to my mother for putting up with me in 2016 i rly cosplayed an american about to lose all of my rights#my god#and if i asked an american right now if they know about why all of serbia is protesting in novi sad theyd be like *cow eyes*#so no thank you#this day is just a random day to me m#not some cataclysmic apocalypse or the election of GODs chosen#dear god get in ur lane#this turned into a vent#vent

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

SO what do you what will happen now with the whole fake Bomer guy supposedly be a trump supporter? Do you think the blue wave will restart or is it too little to late?

The most significantrevelation of the mail-bomber incident was that the Republicanmainstream – not the usual fringe kooks, but the levelheaded,respected commentators – immediately suspected it to be amanufactured “October Surprise.”

Some of those knee-jerktweets have since been deleted, likelyfor the same reason that I was more alarmed that I could entertain a“false flag” theory in the first place than I was by the possible“false flag” itself. Embracing asinine conspiracy theoriesis, to me, a hallmark of left-wing agitprop, an indelible impressionfrom my formative Bush-era youth when ~Halliburton~ and~Bush’s cabinet of puppeteers who have Jewish last names~was unceasingly invoked in anypolitical argument. And yet, despite knowing theoverwhelming odds of a lone lunatic being the perp (as indeed theywere) and my own decades-old biases against conspiracy theories, Istill found myselfmuttering dubiously.

Iwasn’t alone in that impression – the NewYork Times picked up on it too, and as is their wont managed todisclose their unique myopia as well. In their effort to equate allright-wing media to Alex “Lizardman Chemtrails” Jones’s usualconspiracytainment bullshit, theydrop this revealing paragraph:

Mr.Jones has been largely pushed tothe fringes of the internet — kicked off Twitter, Facebook and adozen other services — and his cries for attention now seem mostlypitiful. (This week, he was filmed yellingat a pile of manure outsidea rally for President Trump in Texas.) Buthis spirit lives on in the larger universe of pro-Trump media, whichhas fused the conspiratorial grandeur of Infowars with an unshakablefaith in Mr. Trump’s righteousness.

Theyautomatically equate media exposure of an idea with how manyviewers believe the idea. The thesis of the article lies inthese two sentences; Alex Jones has been silenced, but the moremainstream right-wing media has picked up his ideas, and that’s whythey’re still alive.

Thisalone speaks volumes about the media’s worldview, but to reallydrive it home see thisarticle wherein the reporter blames Trump’s attacks on themedia for their plummeting popularity, as if the Great PresidentialPumpkin can sway millions of Americans into hating themainstream media via his eldritch mind-control rays. This is why theyspeak of “an unshakable faith in Mr. Trump’s righteousness-”leftists view the world in terms of stupid mobs and the influentialdemagogues that sway and lead them. They simply cannot comprehendthat their own actions have shattered the public’s trust in them,despite the problem long predating Trump (one of my Journalism 101professors cited trust polling that consistently put Journalistsbelow used car salesmen back in 2007!) They find it easier tobelieve that their vast media empires’ combined megaphone is beingdrowned out by RumpleTrumpskien pied piping on his magical racistdogwhistle than to admit that people might think for themselves longenough to call them out on their egregious lies.

Thisdovetails nicely with recent revelations thatthe FBI leaked information to the press, then cited said “reporting”to the Justice Dept. as justification for further investigations,including FISA wiretapping warrants. Whilethe media’s lunacy is frequently amusing – reporters leaningdramatically into nonexistent wind, CNN’sfit over a panel truck blocking their stalker peephole in the hedge,or going bugfuck insane because Trumphad dinner without informing the media – nobody’s laughinganymore. And it’s precisely because of the growing understandingamong the populace of how the media has wantonly abused its power toaid the abuse of Federal power to nullify the results of a democraticelection.As Ian Miles Cheong said; “if the media can lie about somethingas insignificant as a koipond feeding ceremony, what else are they lying about?”

Well,now we know – and the people don’t seem amused.

I’vecovered the media’s worldview and demonstrable myopia before; Iaddress it in this instance to show thatthe media simply cannot adapt their message. Indeed,the NYT article on fringe-to-mainstream cites the mocking/pol/ “suspicious devices” meme without apparentunderstanding of how it undermines their implicit assumptions mereparagraphs prior of deplatforming speakers equalingthe silencing of their ideas. Theleft-wing “mobs and demagogues” is more than theory to them; it’show they organize – which is why John Oliver’s sick Friday nightburns are being repeated ad nauseam on Facebook by early Saturdaymorning. Theleft truly cannotmeme;it’s simply how they function. So when RumpleTrumpskien needles themedia into talking All About Themselves instead of the issues at handyetagain, iteffectively makes the mediathe issue at hand – and given that pollingconsistently shows that many Democrats are coming to distrust themedia of late, that’s not a strong issue for the DNC.Conversely, right-wingers will be shitposting the latest dank memeswith or without Alex Jones’s Twitterfeed, comehellor Maxine Waters.

Thusly,I conclude the mail bomber incident won’t have a significant impacton the electoral map – notjust because of widespread cynicism engendered by constant mediafalsehoods, but also because the structural problems that producedsuch alsocripple the media’s ability to exploit such incidents. In fact, themedia’s incredible blindness makes them likely to harmthe left-wing’s cause by doubling down on narratives that wereasinine the first time around. There is no bad news for the DNC thatthe media’s mental illness cannot make worse. Takethe latest example of thesynagogue shooter thatturnedout to be a Trump-hater who thought POTUSwas controlled Jews. Theusual hate-mongeringWaPo crowd actuallydug up the “star-shapedbackground graphic in a campaign ad” gem that was laughablelunacy beforeTrumpmoved the US embassy to Jerusalem and made defending Israel in the UNa cornerstone of US foreign policy. Thisis placed at the topofthe article, as if it’s a powerful and convincing lead-in to thelong-winded paranoid rambling of “troll armies” motivated by theusual mystic ~coded signals~ mentioned later on. Eventhe more sober-sounding takes likethis NYT hit-piece must open by blaming Trump for the crimes ofTrump-supporters andTrump-haters,which obliges the author to afascinating attempt in pissing up a rope without getting wet.

Itnaturally follows, then, that breathless media polling reports citing85% and upwards chances of a “blue wave” retaking the House areabout as trustworthy as similar polling in 2016. Even Nate Silver’smuch-vaunted “538” polling agency has come under prettypointed criticism for the number of times they’ve shrugged offsimilar ���80%” predictions that haven’t come to pass – froma Harvard professor, no less. Furthermore,midterm elections are different in many ways – local issues oftenhave people more fired up (read, pissed off,) especially regardinggubernatorial elections. Since midterms are traditionally very lowturnout, a popular gubernatorial candidate can have a huge impact on“down-ballot” races – i.e. people show up to vote for thegovernor, and vote straight party ticket for alltheother candidates, US House included. In short, the polls mean jackdiddly squat, soeveryone’s simply reporting what they want (if you don’t believeme, look no further than Fox News’s reportinga nail-biting dead heat currently, then thisSeptember 22ndarticle on how dismissing “blue wave” rhetoric as the bullshit itis could suppress the Republican vote via overconfidence.A “dead heat” narrative is the safest way to turn out votes; norisk of overconfidence or hopelessness keeping people away from thepolls.) Soto evaluate the potentials, we must turn to the murkiest of allpolitical-forecastingcrystal balls - “energy levels.”

There’sbeen multiple media-exacerbated own-goals for the left in thatregard, most notably the mind-blowingly vicious smear campaignagainstJustice Kavanaugh that only managed to rile the right wing via sheeroutrage even more than the left. I could roll this one around fora while – talking about the surprising pluralities (note therelatively high numbers of Democrats and low numbers of Republicans“Very Angry” over Kavanaugh’s suffering; a surprisinglycenter-right plurality,) or how big the Republican benefit really was(Republicans being moderately more outraged than Democrats amounts toa low gain if Democrats enteredthe fray with high outrage already; but it’s likely that manyRepublicans who didn’t care at all before are outraged now).Butthere’s a larger factor to contend with – the historical realitythat the party controlling the Executive usually loses seats in theHouse in midterm elections. It happens with regularity for the samereason PoliSci101 shows you a “standardized plot” of Presidential approvalratings over time – human nature. Whoever’s in charge gets blamedfor everything bad, simply enough – so even popular Presidents willshed a few seats in the mid-terms. Combine this with the importanceof turnout in midterm elections and the oft-lamented anti-Trumpobsession on the left, and everything seems to point to Democratsbeing more motivated.

However,I’m not so sure they are.

Youtuber“Aydin Paladin,” an advanced psych student who usually talksabout psychology in a political context, did a video 11 months agotitled “LeftistLethargy and Low Energy,” specifically addressing how aconstant state of horror and outrage at every single damn Trump tweethas the inevitable consequence of emotional burnout. One cannot stayoutraged forever. At some point, you simply stop caring. Onecould debate Ayadin’s point that the left was demonstrablyhittingthis point a year ago, or posit that they’ve had time to recover –but I personally believe the lethargy lingers. Myevidence? A quick jaunt through the New York Times’ editorial page:

*A Halloween op-ed about Trump literally being worse than the fuckingbogeyman (“WhenNightmares Are Real” by Jennifer Finney Boylan,)

*An article begging Democrats not to take a usually-safe votingdemographic for granted, Native Americans

*An article on “how to turn people into voters,” featuring a modelspecific to “black Southerners,” who are a safe Democraticdemographic – but only when they actually turn up to vote,

*Andmost tellingly, an article titled“You’redisillusioned. That’sfine. Vote anyway.”

Blindand narcissistic they may be, but I trust the media to know their owntribe – and theiroutlookon the base’s revolutionary fervor looks rather dim. Once again themedia’s endless talent for own-goals is apparent. The continuingdemonizingof Trump as theworst nightmare ever onlyensures that a choir that tired of the preaching a year ago willremain so. The struggle to get black voters to actually turn out isan old and ongoing one, but pissed-off Native Americans isn’t justElizabethWarren’s fault – it was mostly the media that accepted her DNAtest showing some squillionth of a percent of native DNA asvindication,andthen gallopedover to Trump to triumphantly flaunt it at him, giving him a goldenopportunity to mock it on national TV – on their own live networkbroadcasts, even.

You’llnote that the point regarding the media’s self-sabotage of theleft-wing movement was made many paragraphs ago, but it continues torear its awful head as a salient factor in almost every exampleillustrating any otherpoint in this article – this is how pervasive it is.

There’smore to Democratic lethargy than the media pissing off key left-wingDemographics in western states with important House races, however –there’s also the overall lack of a message. Instead of coalescingon a single one, Democrats appear to be taking a local-issuesapproach, which is rather awkward given they – and the media –have spent the last two years making absolutelyeverything aboutTrump. They’re stillmaking everything about Trump (e.g.synagogue shooter) even now,inthe eleventh hour. Thenthere’s the notable and growing strain between old-schoolblue-collar union Democrats and the “progressive wing” (viz.privileged wealthy white socialists) whichdivides their messaging on the economy – especially tellingconsidering the record-low unemployment and rapidlyrising wages. (It’s hard to tell people they’re living inObama’s economy whenyou were telling them it was Trump’s climate a few months ago.)

Andof course, the cherry on this shitstorm sundae is the latest greatestmigrant caravan advancing through Mexico – seven thousandstrong, originally – which took Trump’s single greatest electionissue and slam-dunked it in the middle of the debate again. Thecaravan is significant because it tangiblyprovesTrump’s long-standing point regarding immigration problems, and isexactly the kind of thing a big wall would hinder – awall Trump can’t build if he can’t get a funding bill through theHouse.

Insum, the left still lacks a coherent message, is still desensitizingtheir electorate with constant panicked screeching, is frequentlypissing off their own key constituencies with their ham-handedagitprop, and are helping to suppress their own vote by portraying anelection that’s all but won. Meanwhile the Republicans have aPresident who’s actually delivered on many of his promises, has agreat recent event to showcase how delivering on the rest rides onthis next election, and, in general, have optimism.Somethingabout Kanye West’s recent visit to the White House stood out to me– he saidhe had nothing against Hillary’s campaign slogan, but when he puton a MAGA hat, he “felt like Superman.”

“Feltlike Superman.” That’s a sentiment of empowerment.Obamaunderstood the power of positive messaging – it’show “Hope and Change” swept him into office in his first term.Democratsthis year simply don’t.

Ican’t call it either way. But I cantell you that anyone who thinks this election is all over but for thecounting isnuts. The battle lines of 2016 have only been dug deeper, and thesimple truths of human nature make for an uphill fight – but by thesame token, Democrats have badly misplayed the hands they have, arecompletely incapable of real self-reflection on any significantscale, and Trump’s been President for two years with realsuccesses, with the much-ballyhooed Trumpocolypse yet to descend.

Insofaras I can call anything, I’d say this election is going to be close.I’d tell you to go out and vote, especiallyif you don’t want to see the party encouraging mob intimidation andstoking racial hatred controlling the House – which they’ll useto launch endless sham investigations of Trump long after Mueller’scharade finally gives up the ghost, in addition to impeaching himjust for the hell of it. If Trump loses the House he- and his agenda- will be a lame-duck for the next two years, because any seriousbill needs to be passed by both House and Senate.

Onceagain, everything is on the line.

I’mnot sick of winning yet.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unraveling of Trump policies a distant hope for separated immigrant families

Now, many immigrants are in a new phase of uncertainty, waiting to see who will win the November presidential election - Trump, or his Democratic opponent Joe Biden. Trump plans to expand and solidify his changes to the immigration system in a second term, while Biden has vowed to undo many of them if he wins.

LOS ANGELES/NEW YORK (Reuters) - A Venezuelan father waiting in Mexico to plead his U.S. asylum case who has yet to meet his newborn daughter. An Iraqi refugee stuck in Jordan despite his past helping U.S. soldiers. A mother sent back to Honduras after being separated at the U.S.-Mexico border from her two young children. A Malian package courier deported after three decades in the United States. And an Iranian couple kept apart for years under a U.S. travel ban.

They have all experienced first-hand the effects of Republican President Donald Trump's signature domestic policy goal in his nearly four years in office - the overhaul of the U.S. immigration system. A multitude of new bureaucratic hurdles to entering or staying in the United States have upended the lives of hundreds of thousands of people around the world.

Trump says the changes were necessary to fix an immigration system he has characterized as broken and riddled with loopholes. As he campaigns for a second term, immigration is once again a key plank of his platform.

While immigrants have faced hurdles settling in the United States for generations and illegal immigration has bedeviled both Republican and Democratic administrations, critics contend no recent administration has moved faster and more aggressively to carry out a restrictive immigration agenda.

Now, many immigrants are in a new phase of uncertainty, waiting to see who will win the November presidential election - Trump, or his Democratic opponent Joe Biden. Trump plans to expand and solidify his changes to the immigration system in a second term, while Biden has vowed to undo many of them if he wins.

But the sheer number of new policies mean that many people waiting in limbo are affected by not only one new Trump measure but several layered on top of each other. Many families have been waiting years to resolve their immigration cases, and regardless of what happens in the election those waits are likely to drag out further.

"A lot of people have it in their mind that a Biden administration would come in and reverse everything," said Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington-based think tank, but "a lot of the policy changes were layered with the intent of making them difficult to walk back."

"It would be impossible for a new administration to undo everything because there is so much to do," Pierce said. "People's lives have already been altered."

Here are the stories of some of them.

DREAMS FADE AFTER TRAVEL BAN

Masoud Abdi hasn't seen his wife Shima Montakhabi since Feb. 1, 2017.

Days earlier, in one of his first acts as president, Donald Trump barred most people from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen from coming to the United States, citing the need to protect the country from "terrorist activities by foreign nationals."

The couple, who met and married in Iran, were living in Tehran and waiting for Montakhabi's visa to be approved when the ban was announced. Abdi, who is a U.S. permanent resident, had a permit that allowed him to spend up to two years outside the United States without losing that status.

But when he saw the news about the ban he panicked. While permanent residents were eventually declared unaffected, in the fog of those first few days Abdi was taking no chances.

He returned to the United States and has not left since, fearing further restrictions that could put his green card and pending U.S. naturalization application at risk. Montakhabi, a pharmaceutical researcher, remained in Iran, her visa application pending.

A physician in Iran, Abdi first came to the United States in 2010 after winning a green card through the diversity lottery. That program - which Trump has criticized - aims to accept immigrants from countries that are not normally awarded many visas.

When he and Montakhabi applied for her visa in late 2015, they had hoped to be starting a family in Champaign, Illinois within a couple of years at most. Now, they are both in their forties and that dream is beginning to fade.

The couple try to speak every few hours, Abdi said. But sometimes the internet doesn't work in Iran and they can't communicate for several days. When this happens, Abdi said, his depression worsens. "Talking to her is all that gives me motivation for living," he said.

The U.S. Supreme Court allowed a revised version of the travel ban to take effect in December 2017. It has since been expanded to additional countries.

Through August 2020, more than 41,000 people seeking immigrant and non-immigrant visas have been affected by the ban, according to the State Department. The issuance of immigrant visas to Iranians dropped almost 80% from fiscal year 2016 to 2019, State Department data shows.

Biden has said he would lift the travel ban if he is elected. But Abdi and Montakhabi are affected by other policy changes, too.

As he waits in Illinois, Abdi says he cannot afford to reduce his hours as a clinical researcher. A more stringent wealth requirement for people sponsoring their relatives to join them in the United States and a separate proclamation requiring new immigrants to have sufficient funds to cover healthcare costs worry Abdi, who fears Montakhabi may be barred if his earnings were to drop. Those measures are being challenged in court, but in the meantime, Abdi has less time to pursue his U.S. medical license.

Another new ban also affects the couple. The administration stopped issuing almost all new family-based green cards in April 2020 until the end of the year, saying the move would protect American jobs amid the pandemic. Spouses of U.S. citizens are exempt, but Abdi is still waiting for naturalization. Under Trump, naturalization processing times have nearly doubled, according to data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

"This is not the America of my childhood, the land of opportunity," he said. "It's not a land of opportunity for me. I'm stuck here and my wife is stuck in Iran."

The State Department said it could not comment on individual visa cases.

SEPARATED, NEVER REUNITED

Maynor tries to keep everyone's spirits up. He is good at it - a skill he has honed as a street vendor hustling to sell oranges in California to make enough money to feed himself and his two young sisters. But it's hard when his mother, Maria, who lives in Honduras, calls to talk to her children and just cries.

"I tell her she has to try to motivate them," Maynor, 32, said of his sisters. "But they start crying when they hear her cry."

The last time the sisters saw their mother was almost three years ago, when Michelle was 8 years old and Nicole just 3 and still breastfeeding. The family is not being identified with their last name because the girls are minors and their attorney is concerned about hurting their ongoing U.S. immigration case.

Maria and her daughters were caught crossing the U.S.-Mexico border near San Luis, Arizona, in December 2017, at a time when the Trump administration was rolling out what would become one of its most controversial policies - a crackdown on illegal crossings that led to thousands of migrant family separations.

After a few days in detention, a border agent came to take the girls away, Maria said. The 3-year-old grabbed on tight to her mother and they all sobbed, she recalled. Maria was bussed to an adult detention center and didn't know where her daughters were for nearly two weeks.

"That whole time period is just a blank," Maria said. "I didn't want to bathe, or do anything. I wanted to die."

She was eventually told by U.S. officials that her daughters had been sent to a shelter in California near where their brother Maynor lived.

Maria had been deported previously after trying to cross into the United States years earlier. During her three months in detention, Maria says she was told by an attorney her only option was deportation: either with her children or alone.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) confirmed the dates of her deportation in 2009 and the separation from her children and subsequent deportation in 2018. The Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Refugee Resettlement, which houses migrant children, said it could not comment on the cases of her daughters due to privacy concerns.

Maria said she fled Honduras after gang members threatened Michelle, and the idea of her daughters returning to one of the most violent countries in Central America made her panic.

"They gave me no real choice," she said in a telephone interview from Honduras. "I went back totally destroyed."

More than 2,700 families were separated between when Trump officially announced a 'zero tolerance' policy to prosecute all illegal border crossers in May 2018 and its abrupt reversal months later in the face of an international outcry.

But the Department of Health and Human Services inspector general said thousands of children were separated both before and after that period. Some parents were separated from their children because they were being criminally charged for illegally crossing the border, others over questions about their identities or previous records, according to court filings.

The girls went to stay with Maynor, who was living with his girlfriend and his newborn at the time. But his girlfriend told him she didn't want the extra burden of caring for his sisters, so kicked Maynor and the girls out, he said.

"There was a time when Nicole would close herself in her room, she wouldn't eat or come out. The babysitter would call me and I would have to leave work to console her. That would happen almost every day," said Maynor.

Now the girls may try to apply for asylum or a form of relief known as Special Immigrant Juvenile status, or SIJ. But a series of changes put in place by the Trump administration has made that process more difficult. Trump's attorneys general have issued rulings to narrow who is eligible for asylum based on claims of gang violence, for example, and increased their scrutiny of SIJ cases.

Maria works cleaning houses and still sees the gang members who she said threatened her daughter. She breaks down every time she talks about being apart from her children.

"Even if they told me I could see them once a year, on a particular date, I would go and leave again," Maria said. "I would do anything, just to see them again."

A FATHER TRAPPED, YET TO MEET HIS BABY

In May, Landys Aguirre's 2-month-old daughter was admitted to an intensive care unit in Chicago with a high fever. He could see, in photos and grainy videos his wife Karla Anez sent him, that the baby's face, arms and legs were swollen.

Aguirre, alone 1,500 miles (2,400 km) away in a hotel room in Mexico under a signature Trump administration program meant to deter migration, began to sob, wishing he could be there to comfort Anez and their daughter, whom he had yet to meet.

The couple fled Venezuela in 2019 to seek political asylum as supporters of an opposition party. Aguirre said he had been kidnapped and tortured by pro-government groups. The pair presented themselves at a U.S. port of entry with copies of a forensic exam and photographic evidence of Aguirre's torture. Reuters reviewed the documents but could not independently confirm Aguirre's claims of persecution.

Aguirre said he never got a chance to present the documents to an asylum officer.

Instead, he was ordered to wait in Mexico for a U.S. court hearing under the Trump administration program known as Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) put in place in January 2019, which has sent tens of thousands of asylum seekers to wait in Mexican border towns. The administration said the program discourages "false asylum claims."

U.S. border officials make case-by-case determinations of who is placed in the program. Anez, five months pregnant at the time, was allowed in to fight her asylum case. She headed to Chicago to join her mother, who had arrived two years earlier.

She sent Aguirre pictures as she grew more heavily pregnant and when she gave birth in March. In May, when his daughter fell ill and he feared she might die, he considered swimming across the Rio Grande - the river that marks the border between the United States and Mexico - but decided against it.

He felt his asylum case was strong and he did not want to jeopardize it. After more than a week in hospital, the baby recovered.

"It's maddening, cruel, harsh and painful to be here in Mexico alone, with no help, in danger and missing my wife and my daughter, who I haven't met," Aguirre said.

"I presented myself voluntarily at a port of entry to ask for asylum, not so they could send me to Mexico like a criminal when I am a professional with two degrees fleeing political persecution."

U.S. Customs and Border Protection said it could not comment on individual cases due to privacy concerns.

Biden has pledged to end the program if he wins in November. But it is not clear what the fate of those now stuck in the program would be. Many are living in tent camps, shelters and rented rooms in dangerous neighborhoods in Mexico, risking kidnappings and extortion.

Anez and Aguirre's chances for U.S. protection also hinge on the fate of another Trump rule, one that barred asylum for almost anyone who transited through a third country and did not seek refuge elsewhere first. It was struck down in federal court and is now on hold, but that ruling could still be overturned by the Supreme Court.

And Anez, applying for asylum, could face new barriers to the issuance of a work permit and other limits proposed in new rules.

Aguirre remains in a hotel in Reynosa - one of the most violent cities in Mexico - as he waits for his asylum hearing date. Originally set for April 6, it has been delayed four times due to the pandemic.

It is now scheduled for November.

DEPORTED AFTER THREE DECADES

Ibrahima Keita was walking to his car ahead of his morning school run in the suburbs of Cincinnati on May 22, 2018, when two immigration agents pulled up and arrested him for being in the country illegally.

Keita asked if he could take his sons to school first, since his wife, Neissa Kone, did not have a driver's license. The agents told him that was not possible. They did, however, knock on the door to tell his wife and sons what was happening.

His sons, Abdul, then 5 years old, and Solomon, then 7, burst into tears. Kone fell to her knees, pleading with the ICE agents not to take her husband, she said.

Keita, 61, originally from Mali, had been in the United States since 1990.

Fleeing a dictatorship, he crossed illegally into the United States from Canada and applied for asylum. Seven years later, at a court date to plead his case, his lawyer never arrived, he said. Not knowing he was allowed to attend the hearing alone, he waited outside the courthouse for hours. The judge ordered him deported from the United States for not showing up, according to court documents seen by Reuters.

Mali would not issue Keita travel documents, so he stayed. In 2008, ICE put Keita, who has no criminal record, on an 'order of supervision,' which allowed him to work in the United States as long as he regularly checked in. ICE confirmed the dates of Keita's removal order and his subsequent supervision order.

During his later years in office, former Democratic President Barack Obama focused on deporting immigrants with criminal records, but Trump shifted that focus in an executive order on Jan. 25, 2017 so that no immigration violators would be spared automatically from enforcement.

ICE said in a statement that the implementation memo that accompanied the executive order made clear that the agency would no longer exempt "classes or categories" of immigrants from enforcement and anyone "in violation of the immigration laws may be subject to immigration arrest, detention and, if found removable by final order, removal from the United States."

The administration also said it would ramp up pressure on countries that had been uncooperative in accepting deportees.

In fiscal year 2016, the last of the Obama administration, around 14% of immigrants arrested by ICE had no criminal convictions. That percentage rose to more than 35% of all ICE arrests in 2019, according to government data.

After a year in detention, ICE chartered a plane in May 2019 and sent Keita to Bamako, Mali's capital. ICE said Keita failed to cooperate with a removal via commercial aircraft in 2018. Keita said he was doing everything he could to try to fight his deportation.

For the family, following him was not an option because Solomon, the oldest boy, has sickle cell anemia, a rare blood disorder that requires specialized care, not easily available in Mali.

After their father's deportation, Solomon internalized his grief while his younger brother Abdul "let it all out," Kone, 48, said. He cried in a way she had never heard him cry before "as if someone had died." He started cutting himself.

Keita calls them three to four times a day, Kone said, and tells them to stay hopeful. He lives in a small apartment near his parents, aged 88 and 92, in Bamako. Kone reads the news and worries: Mali's president was recently ousted in a military coup, potentially further destabilizing the West African nation.

Keita was the family's breadwinner when he worked as a package courier in Ohio. Kone, who is also from Mali and overstayed a tourist visa 20 years ago, does not have permission to work and after their savings ran out could no longer afford to pay rent. She and the boys moved to accommodation provided by a church, then to a hotel under a local effort to house homeless people in hotel rooms to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

She said she hopes that a Biden win will make "everything normal" again. But seeking the repatriation of someone who has already been deported would require an order from a judge to reopen the case, a complicated legal process, immigration attorneys said.

"We never asked for help. We had a good life, a nice house in the suburbs, he worked so hard," Kone said. "Now everything is upside down."

LEFT STRANDED AFTER HELPING U.S. SOLDIERS

In Iraq, Amer Hamdani worked for U.S. military contractors, providing security support for American installations. Now, he often struggles to feed his family as he waits in Jordan to gain entry to the United States as a refugee.

The 44-year-old's former job made him a high priority for resettlement under a special program for Iraqis at risk because of their association with the U.S. government since the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq.

He said he fled with his wife and three children in 2014 after friends told him that his name was on an assassination list of people who had worked with U.S. companies, compiled by followers of populist cleric Moqtada al-Sadr.

While he awaits a decision on his application for refugee status in the United States, he does not have permission to work in Jordan. He has relied on money that his brother has sent from Texas.

"The situation is miserable," he said. He lives on the outskirts of the capital Amman. "I didn't think the U.S. would abandon us like this," he said.

Due to the U.S. involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, demand for the special program Hamdani applied for dramatically expanded, leading to backlogs under previous administrations, refugee experts said.

Hamdani had already submitted his application when Trump won the presidency. But after Trump took office in January 2017 the administration began dramatically slashing the size of the refugee program.

In the 2020 fiscal year, the United States said just 18,000 refugees would be allowed in, the lowest level since the modern refugee resettlement program began in 1980. While 4,000 of those spots were carved out for Iraqis who supported U.S. interests, only 118 people in that category had been admitted as of mid-September.

In addition, 11 countries, including Iraq, faced new, extra levels of vetting. Admissions for those countries slowed to a trickle.

Now U.S. officials are weighing whether to postpone or further cut refugee admissions in the coming year, throwing Hamdani's application, which had been cleared for travel in early 2020, further into doubt.

Resettlement organizations say that while refugee applications can take many years, the delays faced by refugees from the countries selected for extra vetting have grown significantly.

In fiscal year 2016, before Trump was elected, the United States admitted 9,880 refugees from Iraq. That dropped to 144 just two years later in 2018 and 465 in the 2019 fiscal year, according to government data.

The State Department said it could not comment on specific cases but that the "steep decline" and increased processing times for Iraqis who helped U.S. forces is "due to ongoing security conditions in Iraq and travel limitations due to COVID-19."

As the number of refugees overall has dropped, the proportion of Muslim refugees compared to Christians has also declined, according to an analysis of government data shared with Reuters. In fiscal year 2017, 43% of the 53,716 admitted refugees were Muslim while 44% were Christian. In fiscal year 2020 through mid-August, 71% of the 8,310 refugees allowed were Christian and just 21% were Muslim, the data showed.

Biden's campaign has pledged to admit 125,000 refugees a year if he is elected. But the dramatic downsizing of the program could lead to longer-term backlogs even if the cap is quickly lifted.

With fewer people coming in each year under Trump, offices run by nonprofits and funded by the government that help arriving refugees have closed around the country.

Reopening them may not always be possible, resettlement organizations say, leaving new refugees with fewer services.

The Trump administration also signed an executive order mandating that local governments would have to consent to resettlement in their communities.

The measure was challenged and blocked by a court but Texas' Republican Governor Greg Abbott was the first statewide elected official to say he did not want to welcome refugees before the judge's ruling.

Hamdani is waiting to join his brother near Dallas, Texas.

(Reporting by Kristina Cooke in Los Angeles and Mica Rosenberg in New York; Additional reporting by Suleiman al-Khalidi in Amman and Katie Paul in San Francisco; Editing by Ross Colvin and Rosalba O'Brien)

Article Source

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Link

Concern over private email use while in public office is still a thing. Just swap out Hillary Clinton for Ivanka Trump.

President Donald Trump’s daughter and an adviser to the president has found herself at the center of a controversy over her digital communication habits.

The firestorm kicked off in mid-November, when Carol Leonnig and Josh Dawsey at the Washington Post reported that Ivanka Trump sent hundreds of emails to aides, Cabinet officials, and her assistant using a private email account she shares with her husband, Jared Kushner. It was reported last year that Kushner had used a private account to conduct government business as well.

Revelations about Trump’s email use immediately drew comparisons to Clinton, who during her 2016 presidential campaign was dogged by questions about her use of a private server for emails as secretary of state. Donald Trump’s supporters on the campaign trail and to this day often chant, “Lock her up!” in reference to Clinton’s emails.

Ivanka Trump says her case has nothing to do with Clinton and that concerns about her email use are unwarranted. In an interview with ABC News’s Deborah Roberts aired on Good Morning America on Wednesday, Trump said there was “no equivalency” between her actions and Clinton’s.

It may well be true that Trump’s email use wasn’t some nefarious plot to skirt government record-keeping and instead an oversight as she got adjusted to life in government. The chatter about it now may be overblown — but the same goes for Clinton.

Given all the focus on Clinton’s emails, it’s hard to imagine Trump might not have had some sense her actions were a bad idea. Trump’s email use — and her excuse — exemplify the flip-flopping role she tries to play in public life: She’s a shrewd political adviser when convenient, and a political novice and dutiful daughter when not.

According to the Post, aides to President Trump were alarmed by the volume and nature of Ivanka Trump’s email use when she joined the White House in 2017, fearing that her practices were similar to Clinton’s.

When asked about the matter, Trump told aides she wasn’t familiar with federal records rules barring such practices. That’s what her representatives told the Post as well.

Peter Mirijanian, a spokesperson for Trump’s attorney and ethics counsel, Abbe Lowell, told the publication that while transitioning into government — but after she was given a White House email account — Trump “sometimes used her personal account, almost always for logistics and scheduling concerning her family.” That took place, he said, “until the White House provided her the same guidance they had given others.”

Mirijanian said Trump has turned over all of her government-related emails already so they can be stored with White House records.

Trump told ABC’s Roberts something similar in the interview aired on Wednesday.

“All of my emails that relate to any form of government work, which was mainly scheduling and logistics and managing the fact that I have a home life and a work life, are all part of the public record,” she said. “They’re all stored on the White House system.”

When Roberts pushed back, so did Trump. “The fact is that we all have private emails and personal emails to coordinate with our family, we all receive content to those emails, and there’s no prohibition from using private email as long as it’s archived and as long as there’s nothing in it that’s classified,” she said.

Trump also took some indirect hits at Clinton, saying that she had no “intent to circumvent” the White House email system and that she didn’t engage in “mass deletions” after a subpoena was issued.

As PolitiFact explains, an employee for a company managing Clinton’s email server deleted 33,000 of her emails in 2015, a few weeks after the Benghazi committee issued a subpoena requesting her emails related to the 2012 attack in Libya, after realizing he had been requested to do so in 2014 and didn’t. The FBI found no evidence that the emails were deliberately deleted to circumvent the subpoena.

House Democrats have signaled they plan to investigate Trump’s email use when they take over the majority in Congress next year. As the New York Times notes, members of Congress last year engaged in a bipartisan inquiry into the use of private email by multiple White House officials, including Kushner. But they didn’t get very far.

Many observers have cried foul over Ivanka Trump’s email use and noted the hypocrisy of the situation: President Trump and his allies to this day claim Clinton committed criminal activity by using a private server (despite the FBI’s conclusion that she did not), but when it comes to Ivanka Trump, they say it’s no big deal.

President Trump said last week his daughter “did some emails” in a timeframe he described as “early on and for a little period of time.”

“It’s all in the presidential records. Everything is there. There was no deleting. There was no nothing,” Trump continued. “What it is is a false story.”

Clinton’s email use was a huge point of focus during the 2016 election, even after the FBI said there would be no charges brought against her, though the bureau also deemed her actions “extremely careless.” The matter often dominated the news cycle and is still often featured on Fox News and invoked by the president.

One study earlier this year focusing on the New York Times’s election coverage found that in the span of just six days during the final leg of the 2016 campaign, the Times ran as many cover stories about Clinton’s emails they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election.

Ivanka Trump apparently didn’t learn the lesson of Clinton’s email use and apply it to her own actions. She’s not the only one in the Trump administration to have fallen short on that front — the Times last year reported that multiple others, including Steve Bannon, Reince Priebus, Gary Cohn, and Stephen Miller also occasionally used private email addresses for government business.

If Clinton’s emails mattered so much, why shouldn’t Ivanka’s? Or, conversely, if we’re now recognizing that Ivanka’s emails aren’t that big of a deal, doesn’t that shed light on the possibility that Clinton’s probably weren’t, either?

Late night hosts were quick to point out the hypocrisy when the emails story first broke.

“This is really damaging — if anything mattered anymore,” the Late Show’s Stephen Colbert quipped.

“Hillary, meanwhile, is having a good laugh today,” Jimmy Kimmel at Live! said.

Colbert’s team also put together a segment comparison Fox News’ breathless coverage of Clinton’s email with its silence on Ivanka Trump.

[embedded content]

Ivanka Trump has sought to cast herself as a reluctant member of the Trump administration, as a figure who has been swept up in her father’s surprise political ascendance and is just there to lend a hand.

She took an official role at the White House in March 2017 and over the summer closed her eponymous fashion brand, signaling she’s moving more in the direction of politics. Still, she tries to play the other side when convenient.

In June 2017, months after joining the White House in an official capacity, Trump said in an interview with Fox & Friends that she really tries to “stay out of politics” and that she’s not a “political savant.”

In September of that year, Trump told the Financial Times that people have “unrealistic expectations” of her as a moderating force for her father. “That my presence in and of itself would carry so much weight with my father that he would abandon his core values and the agenda that the American people voted for when they elected him,” she said.

In a February interview with NBC News’s Peter Alexander, she scolded the interviewer for asking about the multiple women who have accused her father of sexual harassment and assault. She said it was a “pretty inappropriate question to ask a daughter.”

Trump has positioned herself as a fierce advocate of families and women, but during the family separation crisis, she was publicly silent, speaking out only after the president said he would put an end to it.

But at other times, Trump acts as though she knows exactly what she’s doing.

She sat in for her father at the G20 summit last year, and this year, there were rumblings she might replace Nikki Haley as US ambassador to the United Nations (Trump shot down those rumors). In the same interview where Trump chided Alexander for asking her about the allegations against her father, she discussed US-North Korea relations.

In November, Trump appeared at a campaign rally with her father in Cleveland. When he mentioned Clinton, the crowd chanted, predictably, “Lock her up.”

Roberts in the ABC interview asked Ivanka Trump whether the “lock her up” mantra applies to her, given her email use.

“No,” Trump replied, laughing.

Original Source -> The Ivanka Trump email controversy, explained

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

The Rohingya lists: refugees compile their own record of those killed in Myanmar

New Post has been published on http://newsintoday.info/2018/08/17/the-rohingya-lists-refugees-compile-their-own-record-of-those-killed-in-myanmar/

The Rohingya lists: refugees compile their own record of those killed in Myanmar

KUTUPALONG REFUGEE CAMP, Bangladesh (Reuters) – Mohib Bullah is not your typical human rights investigator. He chews betel and he lives in a rickety hut made of plastic and bamboo. Sometimes, he can be found standing in a line for rations at the Rohingya refugee camp where he lives in Bangladesh.

Mohib Bullah, a member of Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, writes after collecting data about victims of a military crackdown in Myanmar, at Kutupalong camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, April 21, 2018. REUTERS/Mohammad Ponir Hossain

Yet Mohib Bullah is among a group of refugees who have achieved something that aid groups, foreign governments and journalists have not. They have painstakingly pieced together, name-by-name, the only record of Rohingya Muslims who were allegedly killed in a brutal crackdown by Myanmar’s military.

The bloody assault in the western state of Rakhine drove more than 700,000 of the minority Rohingya people across the border into Bangladesh, and left thousands of dead behind.

Aid agency Médecins Sans Frontières, working in Cox’s Bazar at the southern tip of Bangladesh, estimated in the first month of violence, beginning at the end of August 2017, that at least 6,700 Rohingya were killed. But the survey, in what is now the largest refugee camp in the world, was limited to the one month and didn’t identify individuals.

The Rohingya list makers pressed on and their final tally put the number killed at more than 10,000. Their lists, which include the toll from a previous bout of violence in October 2016, catalog victims by name, age, father’s name, address in Myanmar, and how they were killed.

“When I became a refugee I felt I had to do something,” says Mohib Bullah, 43, who believes that the lists will be historical evidence of atrocities that could otherwise be forgotten.

Myanmar government officials did not answer phone calls seeking comment on the Rohingya lists. Late last year, Myanmar’s military said that 13 members of the security forces had been killed. It also said it recovered the bodies of 376 Rohingya militants between Aug. 25 and Sept. 5, which is the day the army says its offensive against the militants officially ended.

Rohingya regard themselves as native to Rakhine State. But a 1982 law restricts citizenship for the Rohingya and other minorities not considered members of one of Myanmar’s “national races”. Rohingya were excluded from Myanmar’s last nationwide census in 2014, and many have had their identity documents stripped from them or nullified, blocking them from voting in the landmark 2015 elections. The government refuses even to use the word “Rohingya,” instead calling them “Bengali” or “Muslim.”

Now in Bangladesh and able to organize without being closely monitored by Myanmar’s security forces, the Rohingya have armed themselves with lists of the dead and pictures and video of atrocities recorded on their mobile phones, in a struggle against attempts to erase their history in Myanmar.

The Rohingya accuse the Myanmar army of rapes and killings across northern Rakhine, where scores of villages were burnt to the ground and bulldozed after attacks on security forces by Rohingya insurgents. The United Nations has said Myanmar’s military may have committed genocide.

Myanmar says what it calls a “clearance operation” in the state was a legitimate response to terrorist attacks.

Mohib Bullah, a member of Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, helps a boy during data entry on a laptop given by Human Rights Watch in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, April 21, 2018. REUTERS/Mohammad Ponir Hossain

“NAME BY NAME”

Clad in longyis, traditional Burmese wrap-arounds tied at the waist, and calling themselves the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace & Human Rights, the list makers say they are all too aware of accusations by the Myanmar authorities and some foreigners that Rohingya refugees invent stories of tragedy to win global support.

But they insist that when listing the dead they err on the side of under-estimation.

Mohib Bullah, who was previously an aid worker, gives as an example the riverside village of Tula Toli in Maungdaw district, where – according to Rohingya who fled – more than 1,000 were killed. “We could only get 750 names, so we went with 750,” he said.

“We went family by family, name by name,” he added. “Most information came from the affected family, a few dozen cases came from a neighbor, and a few came from people from other villages when we couldn’t find the relatives.”

In their former lives, the Rohingya list makers were aid workers, teachers and religious scholars. Now after escaping to become refugees, they say they are best placed to chronicle the events that took place in northern Rakhine, which is out-of-bounds for foreign media, except on government-organized trips.

“Our people are uneducated and some people may be confused during the interviews and investigations,” said Mohammed Rafee, a former administrator in the village of Kyauk Pan Du who has worked on the lists. But taken as a whole, he said, the information collected was “very reliable and credible.”

SPRAWLING PROJECT

Getting the full picture is difficult in the teeming dirt lanes of the refugee camps. Crowds of people gather to listen – and add their comments – amid booming calls to prayer from makeshift mosques and deafening downpours of rain. Even something as simple as a date can prompt an argument.

What began tentatively in the courtyard of a mosque after Friday prayers one day last November became a sprawling project that drew in dozens of people and lasted months.

The project has its flaws. The handwritten lists were compiled by volunteers, photocopied, and passed from person to person. The list makers asked questions in Rohingya about villages whose official names were Burmese, and then recorded the information in English. The result was a jumble of names: for example, there were about 30 different spellings for the village of Tula Toli.

Wrapped in newspaper pages and stored on a shelf in the backroom of a clinic, the lists that Reuters reviewed were labeled as beginning in October 2016, the date of a previous exodus of Rohingya from Rakhine. There were also a handful of entries dated 2015 and 2012. And while most of the dates were European-style, with the day first and then the month, some were American-style, the other way around. So it wasn’t possible to be sure if an entry was, say, May 9 or September 5.

It is also unclear how many versions of the lists there are. During interviews with Reuters, Rohingya refugees sometimes produced crumpled, handwritten or photocopied papers from shirt pockets or folds of their longyis.

The list makers say they have given summaries of their findings, along with repatriation demands, to most foreign delegations, including those from the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission, who have visited the refugee camps.

Slideshow (3 Images)

A LEGACY FOR SURVIVORS

The list makers became more organized as weeks of labor rolled into months. They took over three huts and held meetings, bringing in a table, plastic chairs, a laptop and a large banner carrying the group’s name.

The MSF survey was carried out to determine how many people might need medical care, so the number of people killed and injured mattered, and the identity of those killed was not the focus. It is nothing like the mini-genealogy with many individual details that was produced by the Rohingya.

Mohib Bullah and some of his friends say they drew up the lists as evidence of crimes against humanity they hope will eventually be used by the International Criminal Court, but others simply hope that the endeavor will return them to the homes they lost in Myanmar.

“If I stay here a long time my children will wear jeans. I want them to wear longyi. I do not want to lose my traditions. I do not want to lose my culture,” said Mohammed Zubair, one of the list makers. “We made the documents to give to the U.N. We want justice so we can go back to Myanmar.”

Matt Wells, a senior crisis advisor for Amnesty International, said he has seen refugees in some conflict-ridden African countries make similar lists of the dead and arrested but the Rohingya undertaking was more systematic. “I think that’s explained by the fact that basically the entire displaced population is in one confined location,” he said.

Wells said he believes the lists will have value for investigators into possible crimes against humanity.

“In villages where we’ve documented military attacks in detail, the lists we’ve seen line up with witness testimonies and other information,” he said.

Spokespeople at the ICC’s registry and prosecutors’ offices, which are closed for summer recess, did not immediately provide comment in response to phone calls and emails from Reuters.

The U.S. State Department also documented alleged atrocities against Rohingya in an investigation that could be used to prosecute Myanmar’s military for crimes against humanity, U.S. officials have told Reuters. For that and the MSF survey only a small number of the refugees were interviewed, according to a person who worked on the State Department survey and based on published MSF methodology.

MSF did not respond to requests for comment on the Rohingya lists. The U.S. State Department declined to share details of its survey and said it wouldn’t speculate on how findings from any organization might be used.

For Mohammed Suleman, a shopkeeper from Tula Toli, the Rohingya lists are a legacy for his five-year-old daughter. He collapsed, sobbing, as he described how she cries every day for her mother, who was killed along with four other daughters.

“One day she will grow up. She may be educated and want to know what happened and when. At that time I may also have died,” he said. “If it is written in a document, and kept safely, she will know what happened to her family.”

Additional reporting by Shoon Naing and Poppy Elena McPherson in YANGON and Toby Sterling in AMSTERDAM; Editing by John Chalmers and Martin Howell

Our Standards:The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

Source link

0 notes

Text

Time to #WalkAway: The Exodus of Blacks and Free Thinkers from the Democrat Party - PEER NEWS

New Post has been published on https://citizentruth.org/time-to-walkaway-the-exodus-of-blacks-and-free-thinkers-from-the-democrat-party/

Time to #WalkAway: The Exodus of Blacks and Free Thinkers from the Democrat Party

African Americans and free thinkers are finally leaving the left in droves.

Candace Owens, director of Turning Point USA, has been the victim of vicious liberal attacks because she is a black woman who supports President Trump.

On a recent Fox News interview, she said, “I think the black vote is going to become the most relevant by 2020” and “we’re already seeing a major shift,” referring to the exodus of African Americans from the Democrat Party. The conversation is changing. The black voters of America are no longer remaining stuck in that victim mentality courtesy of the Democrats and are opening up to the choice they have between a party that holds them back and a party that was initiated to put a stop to slavery.

Digital media has allowed for all of this to happen. Social media has given everyday people and insightful influencers alike a voice. We no longer have to stay trapped in the fake reality that CNN and others portray to us. Today, we are hearing different voices and convincing ideas from all kinds of people. And because of this, people like Owens and Kanye West are speaking out about how the Democrats have betrayed them and left them behind in their pursuit of illegal immigration, uninspiring anti-Trumpism, and open borders.

“There is going to be a major black exit from the Democrat Party, and they are going to have to actually compete for their votes in 2020,” Owens stated.

youtube

Fox News’ Laura Ingraham had Brandon Straka on her show recently. Straka is the founder of the #WalkAway Campaign freeing disgusted Democrats to leave their party and join the winning side. He had a red pill experience in 2017 after the Donald was elected which was after he cried when Hillary Clinton lost two Novembers ago. And he decided to walk away from the Democrats because of their nasty rhetoric, incessant intolerance, name-calling and hypocritical judgment. Now, he’s not only worried about all that, but he also now fears outright violence from his former party.

“Their party has no future. It’s over,” Straka said. “People are leaving the left by tens of thousands.” He receives thousands of authentic testimonials from former Democrats regarding how the left has become intolerable to them. They don’t recognize their party anymore. What do they stand for? They hate Trump and love illegal immigrants. Anything else? Please email me or comment below and let me know!

“I want gay people, I want all people, but particularly minorities, in America to note that you have a choice. You don’t have to vote Democrat just because you’re a gay person. You don’t have to vote Democrat because you’re a black person. If you’re a minority, you have a choice, and that’s what this campaign’s about,” Straka finished.

youtube

Rob Smith is a black, gay former Democrat. He is also an author who has become one of the many strong voices online decrying what the left has become. He calls this the “I Don’t Have to be a Democrat Just Because I’m Black Movement,” which embraces traditional values as Democrats move farther left, defending illegal aliens while taking African Americans for granted and leaving them stranded in poverty and perpetual victimhood.

“There is a movement right now of black people standing up because we are always expected to be Democrats,” Smith said. “And there is a movement right now of younger black conservatives, which I am becoming a part of, that is saying, ‘No, you don’t define who we are, you don’t define how we think; you don’t get to control and own our voices.’” As I mentioned in an article in late April, free thinking is on the rise, and many African Americans are getting red pilled with Trump in the White House and Democrats becoming the party of MS-13 and illegal aliens.

Democrats are not looking to better America in any way. As they proved by their lack of patriotism over July 4th, they despise our country and would welcome a second civil war as they did the first one. Instead of devising a winning strategy and an optimistic message to counter Trump’s rising America First voting bloc, they are attempting to legalize a swath of illegal immigrants to ensure another reliable group of Democrat voters for decades to come, just like they did with African Americans in the second half of the 20th century.

The summer of 2018 has been inspirational in many ways. In the face of liberals melting down over every Trump win and Supreme Court nominee, we have also witnessed a rise of black influencers coming out of their closet of shame in support of Donald Trump. The Democrats’ stranglehold of blacks voting unanimously for their party of hate is finally coming to an end.

This has been a long time coming.

It all started in the spring with Kanye’s internet-breaking tweet stating that he loved the way Candace Owens thinks. In another tweet on April 25th, West said, “You don’t have to agree with Trump, but the mob can’t make me not love him. We are both dragon energy. He is my brother. I love everyone. I don’t agree with everything anyone does. That’s what makes us individuals. And we have the right to independent thought.” The color of your skin does not mean you have to vote for one party or another. We need to be a country of individuals and free thinkers. If we all do what’s best for ourselves and our families, we will all be better off for it. Black people are not owned by the Democrats. They are no longer slaves to their lies.

The Democrats keep pushing 'Resist" so that America will no longer "Exist" Don't Wait until Later; Do It Now#WalkAway #RunLikeHell #DitchandSwitchNow Vote Them All Out!

— Diamond and Silk® (@DiamondandSilk) July 9, 2018

“I think there was a tripling in Trump’s approval rating when Kanye came out,” declared Ali Alexander, a 32-year-old political consultant born to an African-American mother and Arab father who saw the beginnings of this movement back in 2012 when the largest sub-demographic of blacks who voted for Romney were black men in their 20s and early 30s. According to a Pew Research exit poll, Romney achieved double-digits in the black vote against a black president. A cultural and demographic shift is underway that cannot be undone if the Democrats continue on their divisive path.

“So I knew that something bad was coming for the Democrats, and Kanye, I think, is the ball that’s bursting,” Alexander said. “It’s like, wait, when this economic pie is growing, are black people gonna have a piece of that? These demographics have been happening for decades.” To Alexander, West’s tweet was a wonderful moment that caused blacks to wonder what the welfare state does for them if they don’t plan to be on welfare. “And I think that Kanye dived on a grenade for the rest of the black community, to have them start flirting with the idea of that.”

While black unemployment is at an all-time low and jobs are available to anyone who wants to work, we are being barraged with how Trump is the new Hitler and a racist dictator who is in league with Russia. But how can Trump be a racist when he kisses black babies, and black women hug him and black men praise him for his pro-job policies? How can more and more blacks be coming around in support of Trump if he is a racist trying to keep minorities down?

Yep, #trump is a racist…. #LiberalSickness#LiberalLogic#MAGA #WalkAway #TrumpTrain pic.twitter.com/pzvLxxlhaU

— Tim Tim (@timnexis) July 9, 2018

“It has all been a lie,” said conservative black YouTuber “Uncle Hotep,” a father of two from Pennsylvania. “It’s unfortunate because a lot of us believed it blindly.” He points to the simple fact that each paycheck he gets is $100 higher than it was before the tax cut. Trump is helping not just African Americans, but all Americans. “He’s put money in my pocket.”

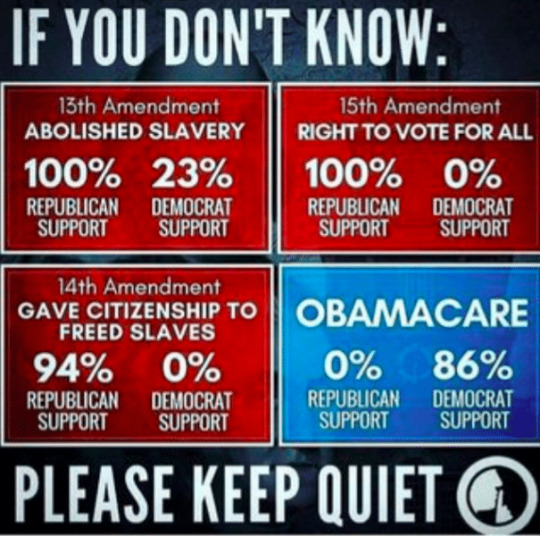

“I voted for Barack Obama his second term,” began conservative “Uncle Hotep,” who went on to say, “The Democrats, in my honest opinion, based on my research, I believe the Democrats have historically hated black people. And I think they still hate black people today.” It is historically accurate that Democrats defended slavery as long as possible and lamented integration of white and black society in the 1960s. They voted against not only women’s suffrage but also black citizenship. The Democrats in Congress were also mostly against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 despite the Kennedy administration’s push for it. The Republican Party was started in the mid-19th century to demolish slavery and defend individual rights for all Americans. Abraham Lincoln was the first Republican president, and he promised to free the slaves and even went to war against a slavery-loving south run by Democrats. Don’t let revisionist history fool you!

“Hotep Jesus” is a black conservative comedian and author who became an internet sensation when he went into a Starbucks and demanded a free cup of coffee, as “reparations” for slavery, since he “heard y’all was racist.” The clip is hilarious and so poignant for these politically correct times.

The African American Pastor Darrell Scott put it best during his 2016 Republican National Convention speech endorsing Trump when he said: “The truth is, the Democratic Party has failed us. America is a melting pot. We’re a country of diversity. And we stand poised to make history by standing together as Americans.” Diversity is our greatest strength not because we are all different but because we are all individuals who mostly love America and have the right to think and choose for ourselves.

As Owens recently told Fox, “I really do believe we are seeing the end of the Democratic Party as we know it.” I think there is ample evidence to prove this is surely the case.

Despite almost a month of continuous Trump is Hitler incarnate and our racist in chief coverage from the mainstream media following the separation of illegal immigrant children at the border, the president’s job approval rating has remained well above 43 percent, according to the Real Clear Politics average.

Prepare for another Trump landslide in 2020 my liberal friends.

Follow me @BobShanahanMan

FBI Jailed Black Activist 6 Months over Anti-Police Brutality Facebook Posts

#African Americans#Culture#democrats#donald trump#Free Thinkers#History#politics#Republicans#Walk Away

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Untold Story of Robert Mueller’s Time in Combat