#i compare math and music to language often and yes they apply too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sometimes I think "German is such a grammatic hellscape" but then I think to myself "but does there truly exist a language whose grammar is not hell?"

No language will ever be not confusing

#girl help#grammar is killing meeeee#and NOT just in german mind you >:(#i compare math and music to language often and yes they apply too#piña rambles

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Fiction Writer’s Guide to English

Tips, tricks, and complaints on how to make your story sound a lot better

By a five-year-old someone not qualified to talk about writing

Disclaimer: By no means am I a writer, a linguist, or an expert on any of the subjects discussed below. However, I do read a lot (a lot), published and unpublished works alike, and this post is made to address certain syntactical, structural, grammatical, aesthetic, and linguistic issues that irk me whenever I come across them. The following is my personal opinion (albeit a well-researched one), and if I've said something horribly wrong, by all means tell me and I shall fix it post-haste. Probably.

Again, this is by no means fully comprehensive, and I doubt it is fully accurate, but from what I've read, this list could do a lot, with a few simple tips, to ameliorate fiction and fanfiction stories a thousand-fold; because, to be honest, a spelling mistake or a grammatical error is one thing that will infallibly take me out of a story and will get me to look at it with a much more critical eye.

Note: the grammar and punctuation rules below (mostly) follow the American set of rules as standard, since I am American, and most fanfiction stories use this standard as well.

I will probably, once the initial post is out there, come and update it when I come across something that would be a helpful addition; feel free also to shoot me a message or an ask if you have a question or need clarification on anything.

These tips are ordered in no specific way whatsoever, and credit goes to all the original creators of the images and posts I reference herein.

Use the passive voice wisely. You'll hear a lot of English Teachers tell you that the passive voice is bad bad bad, and should never ever ever be used. This is not the case. While one should shy away from using it too frequently, there are some cases where the passive voice is acceptable, and even preferable. As a reminder, the passive voice is when the subject of the clause receives the action: "The ball was kicked." Use the passive voice sparingly; it is best used when "the thing receiving an action is the important part of the the sentence—especially in scientific and legal contexts, times when the performer of an action is unknown, or cases where the subject is distracting or irrelevant". (For more info, go here.

Pay attention to the setting and the time period of your story. While this may seem self-explanatory, I have seen far too many stories where everything is going perfectly until the student who is supposed to be in a London primary school asks his "Mom" to help him with his "math" homework. (The correct words are, of course, "Mum" and "maths”.) Similarly, a gentleman living in 1880's New York will not greet his friends with "Yo, what's up, man? You good? Cool." (Yes, that is an actual line I have actually read.) I know that this can be hard, especially for authors who don't live in the country their story is set in, but a little bit of research goes a long way in making your story sound better. (This doesn't apply to writers who use anachronisms and the wrong words purposefully, for humor or otherwise).

Accents and dialects. When you want a person to speak in a certain accent or dialect, research that accent or dialect a bit to understand the most prevalent words and grammatical form, and use them in your dialogue, and, if in first person, your narration as well. You can also think about adding certain regionally-specific words, spellings and grammatical structures. If imitating a work written in that region, definitely watch the spellings and alternative words, and incorporate them in both your dialogue and your narration. ( “mom” vs. “mum”, “math” vs. “maths”, “color” vs. “colour”, etc.). e.g., in England: I was sitting there, laughing --> I was sat there laughing. curb (street), jail, tires, tv --> kerb, gaol (sometimes), tyres, telly, etc.

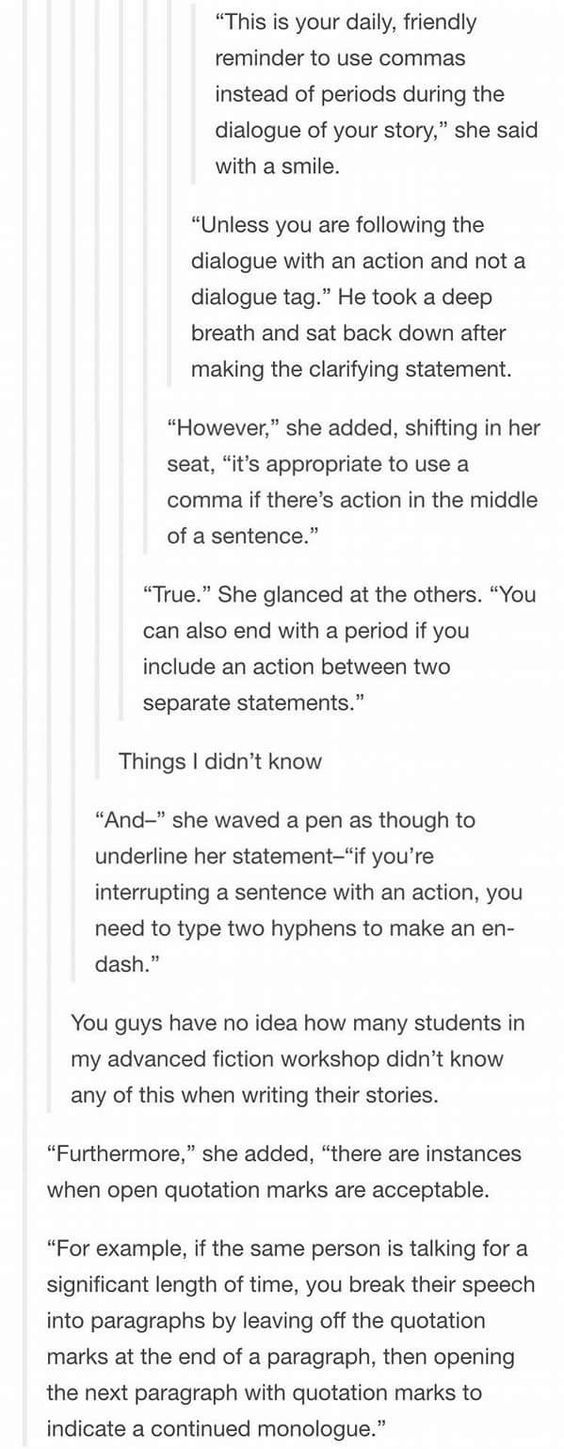

Beware punctuation with dialogue. Use commas. (NEVER EVER EVER CLOSE A DIALOGUE QUOTATION WITHOUT SOME FORM OF PUNCTUATION! There must ALWAYS be either a period, a comma, a question mark or an exclamation point, or an em-dash before the quotation marks close.) The following image perfectly illustrates the proper ways of punctuating dialogue: WARNING: Use em-dashes instead of en-dashes for interruptions. See below.

Dashes vs. hyphens "-": hyphen, used to separate parts of compound words and last names. (e.g. five-year-old; pick-me-up; short- and long-term; Lily Evans-Potter) "–": en-dash (because it has the width of an "N"), used in number and date ranges, scores, directions, and complex compound adjectives. (e.g., he works 20–30 hours per week; the years 1861–1865 were eventful; FC Barcelona beat Real Madrid 3–2; Ming Dynasty–style furniture is expensive) (Note: when you use "from" before a range of numbers, separate the numbers with "to" instead of an en-dash.) "—": em-dash ("M"), can be used instead of parentheses, commas, colons, or for interruptions in dialogue, thought, or narration. (e.g., I know I'm right, and you're — stop throwing things at me!) (For more info, go here.)

Vary sentence lengths. When your sentences are all the same length and all the same complexity, your story starts to sound monotonous. Experiment with length, clauses, commas and semicolons, etc.: “This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety. Now listen. I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length. And sometimes, when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals—sounds that say listen to this, it is important.” — Gary Provost For more on sentence and paragraph structure, see thewritersguardianangel’s post.

Don't be afraid of contractions. Contractions are common in everyday speech and in everyday writing. Use these, especially in dialogue, since contractions will be used almost all the time, unless the character is older, teaching, or speaking intentionally formally. (A college student is not going to tell his friend "You have got to do this homework assignment, or you will fail the class, and the teacher has caught on to you. He will not be lenient." It'll look more like "You've got to do this homework assignment, or you'll fail the class, and the teacher's caught on to you. He won’t be lenient.")

Avoid overly verbose and complex wording, especially in dialogue. Don't use words that are very grandiose and complicated, especially in dialogue with younger people. A teen might use "merely" once or twice, especially in more formal speech, but will very probably use "just" instead. It makes dialogue more realistic too; real conversations don't often have very hypotaxical, full-of-dependent-and-subordinate-clauses language.

Use italics. Italics are, fortunately, available in all softwares and formatting when writing a story, so one mustn't shy away from using them. They provide a very good way to indicate emphasis, as well as to show anger or frustration without the use of capitals, which just make sentences sound like a petulant child throwing a tantrum. Compare "'I CAN'T BELIEVE YOU!' I yelled." and "'I can't believe you,' I hissed." Much more effective, no? (A good rule of thumb is: italics for everything except someone blowing their top. Think the end of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.)

Narrative Perspective. Unless using third person omniscient, stick to one narrative point of view for one section of text, and don't change the perspective style in the story. Don't start in third person close (like Harry Potter) and end in first person (like Percy Jackson). A note about third person close: you can change whose perspective the story is told in throughout the story, but separate those perspective changes, either via a new chapter or a scene break ("******"). Perspectives: First Person: usually singular, occurs when the narrator is telling the story. (Moby Dick, Percy Jackson). Can sometimes be plural (A Rose for Emily). Third Person Close/Limited: the narrator is separate from the main character but sticks close to that character’s experience and actions. The reader doesn’t know anything that the character could not know, nor does the reader get to witness any plot events when the main character isn’t there (Harry Potter). Third Person Omniscient: features a god-like narrator who is able to enter into the minds and action of all the characters (Little Women, The Scarlet Letter).

Use the subjunctive for conditionals and hypotheticals. This might be a bit of a controversial topic, so i'll make this optional, but strongly recommended. The subjunctive mood is what characterizes verbs in conditional and hypothetical situations, so wishes, dreams, hopes, predictions, etc. One should be wary of it in dialogue, though, because it isn't widely used. Use it freely in narration. Usually comes after if or that (e.g., I insist that he leaves leave now; If I was were there, I would be happy.)

Write out numbers. Don't use digits, use words. The man doesn't have 200 dollars, he has two hundred.

The verb "said". Unlike many who tell you never again to use the word "said" when constructing dialogue, I won't. "Said" is a good word, and should be used, but not over-used; find synonyms when it starts to get repetitive, and you can also use it with different adjectives to spice it up. Sometimes you don't need a dialogue tag at all. However, don't try to come up with a different synonym for "said" for every dialogue tag, since it just sounds excessively wordy and extremely trite. A mistake a lot of writers make is the above, which is to replace every single instance of the word "said" with some outlandish synonym. Also, be wary not to replace a dialogue tag with an action verb (which can also lead to a comma splice) (e.g., "I can't believe you," Mike raged, "you're such an idiot!" vs. "I can't believe you!" Mike growled. "You're such an idiot!")

Connect independent clauses correctly. Independent clauses are sentence fragments which have a subject and a verb, and can stand alone as sentences. If one wants to join them into one sentence, however, there are three ways of doing so: One can use a semicolon (as discussed in the punctuation section below), or one can use a comma + coordinating conjunction. A coordinating conjunction is a word that can, after a comma, join two independent clauses, and they are FANBOYS (For, And, Nor, But, Yet, So). (e.g., Alex went to swim in the pool, but Max couldn’t come.) The last way one can connect two independent clauses is with a conjunctive adverb. Conjunctive adverbs look like coordinating conjunctions; however, they are not as strong and they are punctuated differently. Some examples of conjunctive adverbs are: accordingly, also, besides, consequently, finally, however, indeed, instead, likewise, meanwhile, moreover, nevertheless, next, otherwise, still, therefore, then, etc. When you use a conjunctive adverb, put a semicolon (;) before it and a comma (,) after it. They can also be used in a single main clause, and a comma (,) is used to separate the conjunctive adverb from the sentence. (e.g., There are many history books; however, none of them may be accurate.; I woke up very late this morning. Nevertheless, I wasn’t late to school.) These words can be placed pretty much anywhere in the second clause after the semicolon as long as they’re separated by commas on either side (e.g., Mark was happy to have finished his essay; his dog ate it, however, before he could hand it in.)

Punctuation, Punctuation, Punctuation. Watch your punctuation closely, because it can make or break your story. Dialogue punctuation has already been discussed above, but that is for formatting quotations, not for narration and the content of the quotations themselves.

Every sentence or sentence fragment, even it it’s a single word, MUST end with either a period ("."), a question mark ("?"), or an exclamation point ("!"). It can also end with an em-dash ("—") if and only if the thought or sentence is interrupted.

Commas are for separating sentences into more manageable chunks, to separate dependent clauses, and independent clauses with coordinating conjunctions (see below), and to mark off lists. (e.g., I wanted to talk to her, but she had to go shopping for milk, eggs, bread, and cheese.)

Use the Oxford comma. For those who don't know, the Oxford comma is the last comma in a list of things, just before the last item, usually before an "and" (e.g., milk, eggs, and cheese). It helps reduce a lot of confusion, and, while this is a topic that can be controversial, use it to be safe, and to avoid sentences like this: I dedicate this to my parents, my editor and Random House Publishing.

Beware the comma splice. Never ever ever separate two independent clauses (i.e., full sentences with subject, verb, and object) with just a comma. Use a period, a semicolon, or a coordinating conjunction instead. (e.g., A comma splice walks into a bar, it has a drink and then leaves. (for this example, make the comma a period or a semicolon, or eliminate "it" from the sentence.))

Colons (":") are for denoting lists and setting up quoted text (not dialogue. Use commas for that.) (e.g., What I need is this: eggs, flour, and milk.; In Moby Dick, the main character, in the beginning of the book, says: "Call me Ishmael.")

Semicolons (";") are for separating two independent but related clauses, as discussed in the comma splice section above.

Tenses and tense agreements. This is a big one. When writing a story, choose a tense for your narration and stick with it throughout. If you start in the past, as a lot of fiction does, stay in the past until the end. Also, make sure all the tenses in your narration agree with the main tense of your story. (For flashbacks, one of two ways are possible: a blocked off section in italics, with the same tense as the main story, or within the narration, in the tense past the tense of the story (i.e. has -> had; had -> had had)) If events A, B, C happen in order, and we take B to be the "present" in the story (i.e. when the events are unfolding):

Present: B is happening. C will happen. A happened. (I walk down the aisle, happy. Hopefully nothing bad will happen. I wasn't able to cope when the incident last year happened.)

Past: B happened. C would happen. A had happened. (I walked down the aisle, happy. Hopefully nothing bad would happen. I hadn't been able to cope when the incident last year had happened.)

Give your story to someone who hasn’t read it yet. Writing and editing a story is a very comprehensive process, and both you and your beta reader will probably have read it so much that your and their eyes will be jaded and will slide over mistakes. A fresh pair of eves will always be beneficial in sussing out mistakes, typos, plot holes, and the like.

Watch for homophones, misspellings and incorrect word usage. This is the one that is most obvious, and the one that the most people catch and the most people hate. For this reason I will list the most common errors I have seen in hopes of helping those lost souls find they’re way. (See what I did their?) I’ll put in a break to not make this post any longer than it already is:

Index: v. = verb; n. = noun; adj. = adjective; prep. = preposition; adv. adverb; conj. = conjunction.

There vs. their vs. they’re There = In, at, or to that place or position (Look over there! Who’s in there?) Their = third person plural possessive pronoun (my, your, his, our, their) (This is their car, that one is mine.) They’re = contraction for they are (They’re window shopping.) ex: If you look over there, you can see the Simpsons. They’re looking for their car.

Your vs. you’re Your = second person possessive pronoun (This is your card, that one’s mine.) You’re = contraction of you are (Stop shouting! You’re so loud!) You’re insufferable when you get your report card back.

Too vs. to Too = adverb: to a higher degree than is desirable, permissible, or possible; in addition, also (It's too hot in here; You love the Beatles? I love them too!) To = (prep): expressing motion in the direction of; identifying the person or thing affected; concerning or likely to concern something; identifying a particular relationship between one person and another (walking down to the mall; he was very nice to me; a threat to world peace; he's married to that woman over there) (infinitive marker): used with the base form of a verb to indicate that the verb is in the infinitive, in particular. (He was left to die.)

-'s vs. -s vs. -s' (and similar apostrophic conundrums) -'s = a contraction for is, has, or us; possessive indicator for nouns. (it's = it is; let's = let us; he's = he is; a car's = of a car; she’s done it = she has done it); NEVER A PLURAL -s = indicator for plural nouns; with it, a possessive indicator. (phones = more than one phone; cars = more than one car; its = of it, owned by it) -s' = indicator of possessive plural nouns, and possessive for words ending in -s. (cars' = of multiple cars; Iris' = of Iris) Come on, let's go, he's not gonna come anytime soon. Iris' car's broken down, and the car's tires' air pressure is almost zero, and its exhaust pipe is clogged. The towing company workers are going to come soon.

Were vs. we're Were = plural past tense of "to be"; subjunctive of "to be" (We were really happy; If I were rich, I would do this.) We're = Contraction of "we are" (We're going out tonight!) If I were you, I would have made your announcement when we were all together. Now we're all doing our own thing.

Who’s vs. whose Who's = contraction of who is (Who's doing this?) Whose = belonging to or associated with which person (Whose pen is this?) Who's drawing on the board? Can you tell whose handwriting that is?

Who vs. whom Who = what or which person or people, the subject of a verb; used to introduce a clause giving further information (Who ate my apple?; Jack, who was my best friend) Whom = what or which person or people, the object of a verb (By whom was my apple eaten?) Who left this jacket here? To whom does it belong?

X and I vs. X and me X and I = (= we) used when both subjects are the subject of the verb. (Mike and I went to the mall.) X and me = (= us) used when both subjects are the objects of the verb. (My father took Mike and me to the shop.) A good way of figuring out which one to use is to get rid of the second person altogether, and see which pronoun you would use in that case: Mike and I went to the shop –> I went to the shop; He took Mike and me to the shop –> He took me to the shop.

Wary vs. weary Wary = (adj.) feeling or showing caution about possible dangers or problems. (Be wary of strangers.) Weary = (adj.) feeling or showing tiredness, especially as a result of excessive exertion or lack of sleep; reluctant to see any more of; (v.): to cause to become tired (He looked at me with weary, sleepless eyes.) His long day’s march had made him weary, but, wary of possible dangers, he made himself stay awake and keep watch.

Affect vs. effect (for our purposes, excluding obscure definitions) Affect = (v.) to have an effect on; to bring a difference to (The US foreign policy greatly affected European trade.) Effect = (n.) a change that is a result or consequence of an action or other cause (The US policy's effect on European trade was largely detrimental.) Judaism's effect on Christianity largely affected the New Testament.

Could of, would of, should of THESE ARE NOT WORDS. They sound like real ones, but they're not. The correct forms are: could have, would have, should have. (You can also contract them to could've, would've, should've.)

Lose vs. loose Lose = verb; to be deprived of or cease to have; to become unable to find something; to lose a game (I always lose my keys; If we don’t score soon, we’ll lose; I can’t keep losing people) Loose = adjective; not firmly or tightly fixed in place; detached or able to be detached (These pants are too loose; Let loose! You're too strung-up!) Loose shirts and pants are comfortable, but don't wear them to interviews or you'll lose your reputation and respectability.

Except vs. accept Except = (prep.): not including; other than (everything except for my socks) (conj.): used before a statement that forms an exception to one just made (I didn't tell him anything, except that I needed the money). Accept = (v.) consent to receive; give an affirmative answer to; believe or come to recognize (an opinion) as correct (he accepted a pen as a present; he accepted their offer; her explanation was accepted by her friends.) He accepted every one of her excuses, except for her claim that her dog had eaten her homework.

Peak vs. peek (vs. peaked/peaky) Peak = (n.): point or top of a mountain; point of highest activity; (v.): reach a highest point (He climbed to the peak of Mt. Everest; I peaked in sixth grade) peaked (US), peaky (UK)= (of a person) gaunt and pale from illness or fatigue. (You look a bit peaked/peaky. Are you ill?) Peek = look quickly, typically in a furtive manner; protrude slightly so as to be just visible (Faces peeked from behind the curtains; his socks were so full of holes his toes peeked through) Don't peek through the curtains!, he said, then climbed to the peak of a nearby hill.

Advice vs. advise Advice = noun: guidance or recommendations (e.g., He's in dire need of some relationship advice.) Advise = verb: offer suggestions about the best course of action to someone; to recommend; to inform. (I often advise my friends regarding their scholastic endeavors; I advise you to take this class; you will be advised of the requirements) Go, advise him about what to do for his relationship; he'll heed your advice.

Suit vs. suite Suit = (n.): outfit, set of clothes, men's outfit with jacket and pants (He's wearing a very nice suit.) (v.): be convenient for or acceptable to; act to one's own wishes; to go well with. (He lies when it suits him; suit yourself; that hat suits you.) to follow suit = conform to another's actions. (James started eating and Lily followed suit.) Suite = a set of rooms designated for one person's or family's use or for a particular purpose; a set of instrumental compositions (I rented out the honeymoon suite; I love Gustav Holst's The Planets' Suite) The man, dressed in a sharp suit, stepped out of the honeymoon suite, and his newlywed wife followed suit.

Curb vs. curve Curb = (n.): a stone or concrete edging to a street or path (He parked his car on the curb) (v.): to restrain or keep in check (Curb your enthusiasm) Curve = noun: a line or outline that gradually deviates from being straight for some or all of its length; verb: to form or cause to form a curve (The parapet wall sweeps down in a bold curve; her mouth curved down) He parked his car on the curb, just where the road started to curve into the suburbs.

Ladder vs. latter vs. later Ladder = a structure consisting of a series of bars or steps between two upright lengths of wood, metal, or rope, used for climbing up or down something (He climbed the ladder.) Latter = situated or occurring nearer to the end of something than to the beginning; denoting the second or second mentioned of two people or things (The latter half of 1946; Arthur and Richard were friends, and the former died while the latter lived.) Later = comparative of late. (I was late, he was later.) Frank and Emma, while friends, had a falling-out; the former went into the ladder-making business, and, two years later, the latter moved to France.

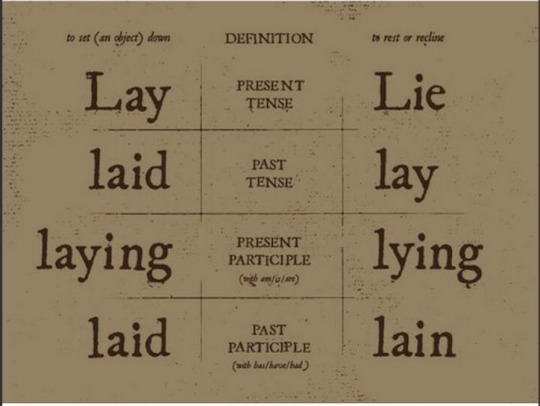

Lay vs. lie (re: the reclining or putting down definitions)

Break vs. brake Break = (v.): separate or cause to separate into pieces as a result of a blow; to interrupt (If you pull on the rope too much, it'll break.) (n.): an interruption; a pause from work (You're way too tired! Take a break!) Brake = (n., with equivalent verb) a device for slowing or stopping a moving vehicle. (If you want to stop your car, you have to press on the brakes.) Don't step on the brake so hard! You'll break both our necks!

Taught vs. taut Taught = past tense of "to teach" (I taught middle schoolers in Boston for three years.) Taut = (adj.) stretched or pulled tight, not slack; (of muscles) tense and not relaxed (The rope was pulled taut; all his muscles were taut and straining) In the fitness class my friend taught, he said that you shouldn't keep your muscles taut all the time.

Through vs. threw Through = (prep.): moving in one side and out of the other side; continuing in time toward completion of; so as to inspect all or part of; by means of (a process or intermediate stage) Threw = (v.) past tense of "to throw" I threw the ball straight through the doorway.

Retch vs. wretch Retch = (n., v.) make the sound and movement of vomiting (When I saw the blood, I retched.) Wretch = (n.) an unfortunate or unhappy person; a despicable or contemptible person. (the wretches were imprisoned; ungrateful wretches) I almost retched at the thought of being nice to that ungrateful wretch.

Ring vs. wring Ring = 1. (n.) a circular band; a group of people or things arranged in a circle. (Her engagement ring was beautiful; the men stood in a ring.) 2. (v., associated n.) make a clear resonant or vibrating sound; (of a place) resound or reverberate with (a sound or sounds) (Church bells are ringing; the room rang with laughter) Wring = (v.) squeeze and twist (something); break by twisting it forcibly (I wring the cloth out into the sink; I wrung the animal's neck) If you don't stop that alarm from ringing, I'm gonna wring your neck!

Bear vs. bare Bear = 1. (v.) To carry; to support; to endure. (He was bearing a tray with a tea service on it; weight-bearing pillars; I can't bear it!) 2. (n.) a large, heavy, mammal that walks on the soles of its feet, with thick fur (Polar bear) Bare = (adj.) not clothed or covered; basic and simple (He was bare from the waist up; the bare essentials of a plan) Apparently, men can't bear to see women's bare shoulders.

Pose vs. poise Pose = 1. (v., w/ associated n.) assume a particular attitude or position in order to be photographed, painted, or drawn (She posed for the camera). 2. (v.) to present or constitute (a problem, danger, or difficulty); to raise (a question) (This storm is posing a threat to our summer plans; a statement that posed more questions than it answered) Poise = (n.) graceful and elegant bearing in a person. (Poise and good manners can be cultivated.) Poise is not just striking a haughty pose; it's about how you hold yourself.

Pore vs. pour Pore = 1. (n.) a minute opening in a surface (this opens up the pores in your skin) 2. (v.) be absorbed in the reading or study of (I spent hours poring over my physics textbook). Pour = (v.) (especially of a liquid) flow rapidly in a steady stream; to cause a liquid to do so (The water poured off the roof; I poured myself a glass of milk). As I was cleansing my pores with a face mask and poring over my favorite book, I accidentally spilled the water I had poured myself all over my pants.

Breech vs. breeches vs. breach Breech = the part of a cannon behind the bore. Breeches = short trousers fastened just below the knee Breach = an act of breaking; failing to observe a law, agreement, or code of conduct, or the action of doing so (A breach of contract; the river breached its banks) (Come on, guys, no one wants to hear about an army trouser-ing the perimeter.)

Rend vs. render Rend = (v.) tear (something) into two or more pieces (teeth that would rend human flesh to shreds) — Note: the correct term is heartrending, since whatever does that rips the heart in two. Render = (v.) provide or give (a service, help, etc.); cause to be or become; represent or depict artistically (A reward for services rendered; the rain rendered my escape impossible; the eyes are exceptionally well rendered) The artist's rendering of the wolf's fangs, which would easily rend human flesh to shreds, was amazingly realistic.

Damnit It's either dammit or damn it. The "n" disappears if it merges into one word, but stays if it's two.

Conclusion: Look. Writing is hard. I know. Some of the above tips seem fairly obvious, and I know that mistakes, errors, and typos happen and go unnoticed. That being said, if you apply these tips regularly, and devote a bit more time to proofreading and editing, the quality of your story and the satisfaction of a lot of your readers will increase tremendously. Authors, I know writing is a thankless job, and many of you are sacrificing your own time to satisfy your followers and your readers; and for that, on behalf of your readers, and even on behalf of those that read and don’t leave reviews, thank you. Do not ever think that this post is meant to belittle you or your devotion to your craft; it is just a list of hopefully helpful suggestions that can help you and, with it, please those readers — like me — who are unfortunately too picky for their own good. And again, use these tips freely (I take credit only for putting them together), good luck, and know that you are universally loved for your efforts, past, continuing, stopped, or postponed. Thank you.

#writing#writing tips#grammar#english#english language#fanfiction#fiction#tips#vocabulary#punctuation#words#literature#perspective#verbs#verb tenses#orthography#homophones#misspellings#typos#errors#narration#narrative perspective#narrative voice#dialogue#authors#writing suggestions#dialogue punctuation#why did i make this

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

🐼 = 🐈 + 🐻

Over the past few days I’ve finally understood why I’m learning Chinese: to converse with Chinese people.

“Well, duh,” you might be thinking.

But up until this week I’ve mostly viewed learning Chinese as a game, a real life word puzzle, not unlike your weekly Sunday paper’s. See, I adore puzzles, especially language ones. Scrambled jumbles, encrypted criptoquips, punny crosswords? Yes, yes, and yes. I haven’t studied any other foreign languages so I don’t know if they’re in the same boat or not, but Chinese has the right balance of structure and imagination for me to have fun learning it as if I were sitting at my kitchen table, eating brunch in my pajamas, while hunched over the New York Times.

Chinese’s structure comes from sentence patterns, or grammatical fill-in-the-blanks. I guess English also has these, but since I haven’t studied English as a foreign language I can’t really give an example. But once you learn a Chinese sentence pattern the customizable possibilities are endless! As you acquire new vocabulary you can “plug and chug,” as my high school math teacher Mr. Callesen used to say. Come to think of it, sentence patterns are a lot like mathematical formulas, except with vocabulary, not numbers, as the input. (Side note, four of this program’s students, myself included, all study math at their home colleges. Math and Chinese have a surprising amount of similarities…)

The imaginative side of Chinese for me arises from encountering new vocabulary words and guessing their meanings. Chinese nouns are a lot more explicitly named than English nouns. A few examples, for clarification: panda = 熊猫 = “cat bear”; illiterate = 文盲 = “writing blind”; size = 大小 = “big small”; intensity = 强弱 = “strong weak”; proportion = 比例 = “comparing instances”. So once you’ve accumulated enough characters in your vocabulary you can read a new text with many unfamiliar words and more or less comprehend the gist of the content. Unless you’ve intensively studied Greek and Latin roots, this is a lot harder to do in English.

I also love playing board games like Scattergories and Taboo. And since my vocabulary isn’t yet extensive I have to play these games a lot when I’m having a conversation with someone. “Apply” becomes “giving your grades and written essays to a college because you hope they will allow you to take their classes”; “fog” becomes “that white water in the sky at the top of a mountain that gives you a spooky feeling” except I don’t actually know the word for “spooky” so I make a ghost “ooOOo00o” sound effect and undulate my arms. So. many. sound effects.

My closest friends here in Harbin so far are all American students, and it’s only natural that I spend the most amount of time with the people I’m closest with. However, due to my program’s language pledge, we aren’t allowed to speak English to each other. I thought this requirement would be a lot more of a hassle than it actually is; yeah, there are struggles, especially when you’re in a horrible mood and need to angrily rant, but your lack of loquaciousness just makes you even more frustrated. I also thought that I would completely lose my personality in this foreign language, condemned to forever rehashing mundane textbook phrases. Definitely not true! People’s personalities are the same in any language they’re speaking, body language included. Sure, some jokes don’t land when you’re not yet a master of the language. But I amaze myself with how much I am able to convey and, conversely, how much I am able to understand.

So I’ve been spending a lot of time hanging out with American students, but why? I’ve already spent a vast majority of my life dealing with Americans, those who share more or less the same experiences and points of view as I do. I’m still pretty embarrassed when using Chinese with native speakers, but my recent revelation was that my Chinese isn’t going to improve if I only speak with other Americans — we all make the same grammatical mistakes influenced by our shared native tongue’s linguistic customs. So I’m trying to put myself out there more often by speaking with Chinese people. But when yesterday’s newspaper class’s homework was to ask multiple Chinese people their own views about China’s 户口 system, I was terrified.

This system doesn’t really have an American counterpart, so it’s difficult to understand. Even many Chinese people seem to not fully understand the policies and restrictions. But, from what I understand, it goes like this: When you are born in one of China’s 32 provinces (equivalent to America’s 50 states) you hold papers identifying you as that province’s resident. If you to move to another province you must decide whether or not to switch your 户口. If you hold a province’s 户口 you receive the services that province has to offer: access to schools, hospitals, jobs, etc. One American equivalent is “in-state tuition” for students who attend their home state’s public universities. But there is also a difference between urban city 户口s and rural farm 户口s. So one pressing issue today is the difficulty rural people face when attempting to move to an urban city with a higher quality of life; due to government quotas and allocations, everyone who applies for a new 户口 is not necessarily approved.

This topic isn’t your typical conversation of, “How’s the weather today?” and “Oh yeah, I’m exhausted, too.” So I was dreading asking our Chinese roommates their own opinions about the 户口 system because I knew I wouldn’t understand a single bit of their replies to this lofty subject. But I was wrong! I asked three or four people and I was able to understand about 80-85% of what they were saying! How exciting it was to be able to ask actual people their opinions, and not only rely on what I might read in the media.

Every day I am delightfully surprised by how attuned my ears have become to attentively listening to native speakers. But it’s funny, my English listening skills have also exponentially improved. When I listen to a music album I’ve heard a thousand times before (yeah, I know, language pledge: I should be completely immersing myself in Chinese, even with the music I listen to. But I only listen — oh how I miss singing in the shower!!) without even consciously trying I understand the singer’s words. I’m already disappointed by the thought of returning to America and once again being surrounded by my native language, not constantly being challenged to listen and speak throughout the day. But I’ll still be in Harbin until December, so I’m mostly just excited to see how much my Chinese can improve throughout the next five months.

0 notes