#how do you woke-ify abuse ???

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

yknow youd think the plural/ramcoa community would have a better grip on cults and organized abuse but a lot of these fucks are about as dense as anyone else when it comes to poc being subjected to cults or ritual abuse. somehow its okay when we're subjected to it because somehow its our culture (just another way to say "in our blood".)

#how do you woke-ify abuse ???#by hiding it under the guise of multiculturalism.#oh and american sensationalism. these guys think the rest of the world is held under american laws and standards.#hey as someone who lives in a theocracy#no! are you stupid!#also what a shitty fucking display of racism to look me in the eye and tell me fgm is my culture so i should just let it happen#you dont know fuck about my culture fuckface#christ. this is why plurality is so associated with being white#ramcoa#ramcoa survivor#plurality#plural system#did#osdd

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! Just to tell you I loved your critique against that Achilles Song book and I agree with you that I hate how Greek (and at lesser or more degree Roman or Egyptian) classics are changed in a nonsense way just to please the modern reader and give them a progressive agenda to the characters.

Just for curiosity, what do you think about fantasy media that is inspired in ancient Greek myths and legends like Percy Jackson books or Saint Seiya?

Dunno, those were my faves when I was a kid (but I have not checked them since at least 10 years ago, lol), but, seeing how the Percy Jackson fans try to portrait themselves as all knowing about Greek culture, while actually not engaging in the classics and refusing to know about Ancient Greek history and culture. The Saint Seiya guys seem more normal, but I'm not sure if Greek people just saw the anime as a gross cultural appropiation like Hercules from Disney or they actually did not mind it.

An interesting ask to receive, thanks! And hm... I don't really know? I haven't read Percy Jackson or Saint Seiya so I can't comment. It all depends on the media in question - it's nice to see so many people like it, but our ancient legacy is kind of all Greece has right now. The economic depression, the ecological impact on the islands that's been happening, the fact that it's mainly considered a tourist destination for wealthier Europeans and the bitter state of the modern Greek youth - and yet we have this legacy we feel so connected to despite all the years between, lmao.

My family is from Sparta - a small rural village just outside it, actually - and so when the movie 300 came out the hype was unreal. Like King Leonidas is a cultural hero, there's still a monument to him in Sparta - they were making a movie about our guy! I saw it with twenty Greeks, all Spartans... and they hated it. They were yelling at the screen, they were so upset, and none of them knew what a Frank Miller comic book was. I recently tried to rewatch it and had to turn it off at the scene with the ephors and the oracle. Don't get me started on Troy, lol.

Otoh, I recently enjoyed Hades (the game) though I avoided it for a while. It's bright and colorful, the gods are strange and erratic, and it's tons of fun. Demeter grief-stricken at the loss of her daughter, Persephone avoiding Hades and Hades being angry and bitter - that was great. (I could go into a whole tangent about how people are actually erasing the voices and pain of ancient women when they woke-ify Hades and Persephone, but.)

The essential thing is this: the ancient Greeks were capable of criticizing their own culture. We invented philosophy: the art of sitting around talking about what's wrong with society and how we might fix it. They wrote plays - plays that won awards, that were preserved unto this day! - that served as a feminist critique of their classic heroic myths. Going back to the 300 film, while it's true oracles were often sexually abused, they noticed that was a problem and made changes to prevent that. There's this attitude people take to ancient cultures a lot where they think people were just... stupid, and wholly swallowed everything, and then they're gonna write their critique of their problematic beliefs without considering the humanity and knowledge of people who lived thousands of years ago.

You don't need to completely change the themes and meaning and significance of our stories, but what you can do is humanize them. Rather than hole them up in some white-walled Ivory Tower of Academia bring them out as they were - intended to be funny, intended to make you think - while preserving the historical context. I have dreams of making an Odyssey film (that some EU arts fund needs to give me a billion dollars to make. also, i am a legendary respected filmmaker in this fantasy) that would bring economic prosperity to the Greek islands and also make it /funny/, showing that Odysseus was a trickster figure who fit ancient heroic definitions of being a wild celebrity figure rather than a Hollywood Hero. Making it clear that his wife was just as smart as him and they were a love-match and making Athena buff as hell and swapping into a man's body, even making Odysseus black - none of that would be modernizing the story to suit our woke tastes. It would piss the hell off a lot of supposed "Classics" fans.

Ultimately, though, having fun with the mythos isn't actually harmful. What is harmful, what genuinely upsets me on a fundamental level, is how Le Classics have been incorporated into this great ideal of Western Civilization and then been appropriated by white supremacists. Here's a great blog doing the good work going into it in detail, but twisting ancient culture to fit your own modern ideals is just.... not good for anyone, lol.

EDIT: ...In my last post I was like "why is tumblr recommending me eurofash propaganda" and I just realized. Liking ancient greek culture and the classics is probably why 0__0

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'll Bleed For You | Part One

Group: ATEEZ

Pairing: Fem!OC x Serial Killer!Wooyoung

Word Count: 2.5k

Rating: 18+ to 21+

Genres + AUs: Non-Idol AU(kind of), Serial Killer AU, Smut, Horror, Angst

Content + Trigger Warnings: Strong language, explicit sexual language and descriptions, stalking, verbal abuse, sibling rivalry hatred, Hongjoong's really mean to OC, descriptive talk of cutting and tasting blood, brief mention of faked suicide(it's in a dream)

Tags: @kpop---scenarios @jeonrose @skittlez-area512 @umbralhelwolf @mybiasisexo @skeletor-ify @biaswreckingfics @bloopbloopkai @trashlord-007 @liliesofdreams @rdiamond2727 @naturalogre

Network pings: @cacaokpop-fics

Masterlist

«-Previous | Next-»

Kim Yangmi woke to the sound of her cell phone ringing incessantly, the noise extremely loud to her hungover brain. Groggily she reached for the offending object and answered without checking the caller ID.

"Hello?"

"Yangmi, where the hell have you been?" The voice of her best friend Kyunghee spilled into her ears. "I've been trying to call you for at least an hour!"

Yangmi sighed. "I was sleeping off my hangover. We went hard last night, shouldn't you be just as shattered?"

Kyunghee snorted. "I am, I just hide it better than you. But that's not why I called. Have you seen the news today?"

Frowning, Yangmi put the call on speaker and opened the news app on her phone. "Not since before we went out last night. Why?"

"You might want to take a look. Seems we weren't as sneaky as we thought we were."

As Kyunghee's words filtered through her phone, the news app finished loading and Yangmi saw at once what her friend was talking about.

TWIN SISTER OF FAMOUS RAPPER CAUGHT DRUNK & HIGH AT STRIP CLUB

Yangmi gulped, already imagining the fit her brother would throw when he came home.

"Shit, Kyunghee, this is really bad." She exclaimed, scanning the page with an ever-growing dread. The comments on the article were undoubtedly scathing, and Yangmi knew better than to read them.

"What're you gonna do?" Kyunghee questioned, concern lacing her voice.

"I have to post an apology before people start pulling Joong into this. Ah, damnit, what was I thinking?!"

"You should be allowed to have fun without worrying about the consequences." Kyunghee's argument was weak, and she knew it.

"Not when your brother's famous and hates your guts, sadly. Listen, I'll call you back later and let you know how he took it, okay?"

Kyunghee sighed resignedly. "Good luck Yangmi. Try not to let him strangle you, alright?"

Yangmi chuckled dryly. "I'll do my best."

After hanging up, Yangmi quickly sat down at her laptop and began to craft an apology for her actions. When she finished, she read over it to ensure it sounded as sincere as possible. Not because she felt remorse, but because her brother would be furious if she didn't. Apparently his reputation mattered more than any of Yangmi's thoughts or feelings.

Almost as soon as the apology went up it spread, people sharing it around and discussing it. As she watched the activity, she noticed that for the most part the responses were positive. Feeling relieved, she closed out the webpage, opening up YouTube to pass the time until her brother returned.

The door to the flat flew open, jerking Yangmi to attention as it slammed loudly against the wall. She took a deep breath, preparing herself for the argument that would undoubtedly come from this.

"Kim Yangmi, get the hell in here!"

"Coming!" One last deep breath, and she stood to face the storm.

Kim Hongjoong stood by the dinner table, glowering at his sister. "Would you like to explain to me what the fuck you were doing last night?"

Yangmi gave a short, humorless laugh. "Why ask me? I know you read the news."

Hongjoong let out a frustrated growl. "God, how could you be so fucking careless? I tell you not to stay out late, I tell you not to go out partying, and you just have to throw it all in my face, don't you? I saw that apology you posted and I don't believe you meant a word of it!"

Yangmi rolled her eyes. Of course he didn't believe it, he hardly ever believed a word she said.

"Well, I'm not surprised you didn't find it sincere. I'm not sorry for jeopardizing your career. If I was gonna be sorry for anything, I'd be sorry for sullying the family name." Yangmi huffed and shook her head. "You know, I really wish our parents were still alive. Because if they were, you'd have never become famous and I wouldn't have to put up with your shit!"

Hongjoong laughed mirthlessly. "You think you put up with shit? You can't even begin to imagine the things I have to deal with on a daily basis, and you think I'm giving you hell? Fuck that, I can't even trust you anymore Yangmi! You know what I wish? I wish that I'd been born an only child and not a twin. Then I wouldn't have to put up with your bullshit antics!"

Yangmi froze, shattered by the words that spilled from her brother's lips. Tears gathered in her eyes and she turned, intending to flee before they fell, but Hongjoong had other plans.

"Just a minute, I'm not through with you."

Yangmi stopped, gathering herself before turning back around. "What?"

"In light of your recent actions, I have no choice but to confine you to the flat for the foreseeable future. I will be locking all the windows and doors whenever I leave, and if you wish to go out I will be accompanying you to ensure you don't get up to any tomfoolery. In time, when I feel you can be trusted, you will be free to come and go as you please."

Yangmi stared at him, her mouth open in shock. "Oh, so you're my parent now as well? Last time I checked, 25 is a little too old to be grounded."

Hongjoong stared her down, face expressionless. "Act like a child and you'll get treated like a child."

Fury welled up inside her, making her clench her fists and scream "I hate you! You're a sorry excuse for a brother and I wouldn't wish this life on my worst enemy!!"

Turning around she ran to her room, slamming the door shut and sinking to the floor as hot tears spilled down her face.

The first week of Yangmi's confinement was miserable. Hongjoong had just released a new song, so he was gone all day and most of the night as well. Yangmi grew bored quickly, finding most of her usual pastimes failing to keep her entertained for long.

But with the second week came something that would soon occupy her thoughts in every waking moment.

Yangmi woke on Monday with the feeling that something was different, and not in a good way. The feeling was confirmed when she found a lavender-coloured envelope wedged in a thin crack of one of her bedroom windows.

Curious what was in the envelope, Yangmi pulled it through the crack and examined it. There was no writing on it, just skilled drawings of cherry blossom clusters in each corner. There was nothing left to do but open it, so that's what she did.

The paper was the same pretty lavender as the envelope, and written on it was a short note in neatly printed characters.

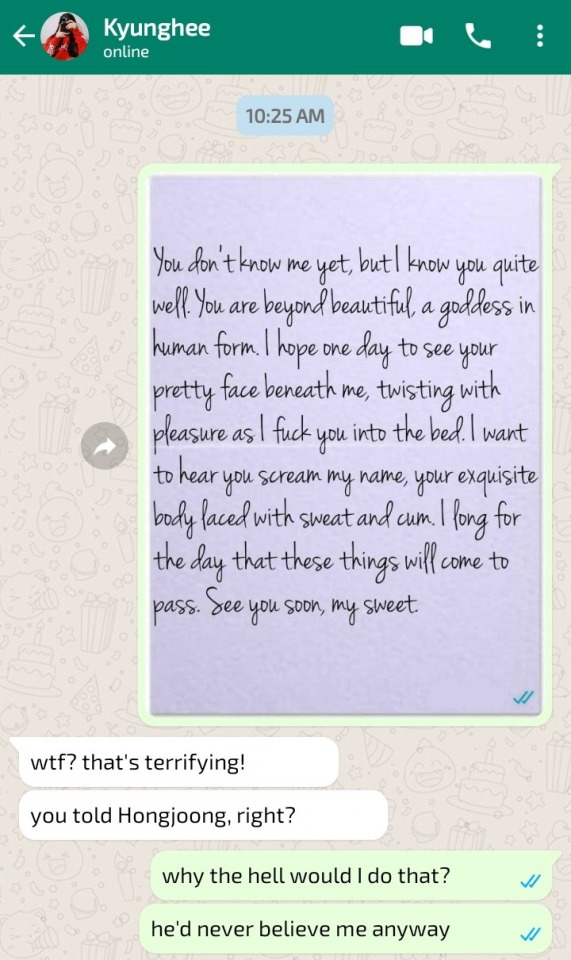

"You don't know me yet, but I know you quite well. You are beyond beautiful, a goddess in human form. I hope one day to see your pretty face beneath me, twisting with pleasure as I fuck you into the bed. I want to hear you scream my name, your exquisite body laced with sweat and cum. I long for the day that these things will come to pass. See you soon, my sweet."

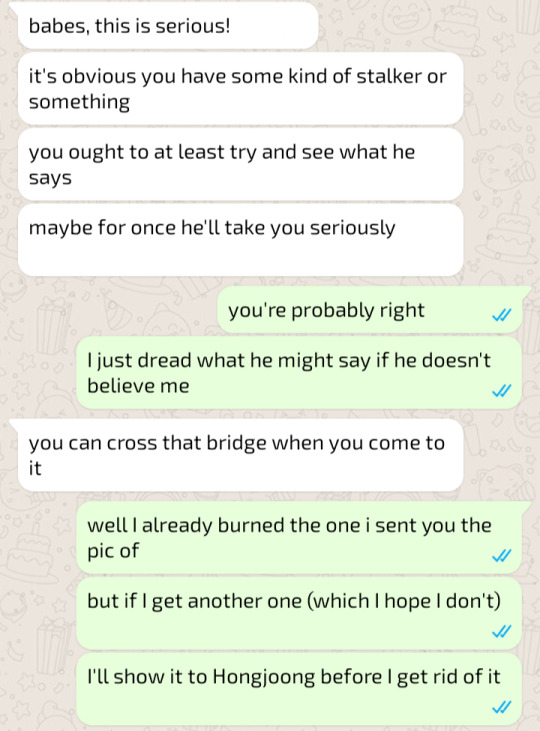

Yangmi felt nausea rise in her stomach as she took in the contents of the letter. Who could have sent her this? Was this Hongjoong's idea of a sick joke? Yangmi took a picture of the letter, intending to ask Kyunghee for advice. Then she took out a box of matches from a drawer in her nightstand and burned the letter in her bathroom, rinsing the ashes down the drain afterwards.

With that done, she sent the image to Kyunghee and explained where she found the letter.

No letter came the next day, nor the day after. Yangmi woke on the third day feeling somewhat anxious and unnerved. She moved through the day slowly, expecting at any moment to turn a corner and find another letter perched somewhere.

Around noon, Yangmi's phone rang. The call was from an unknown number, which didn't surprise her in the least. Assuming it was another crazy fan trying to get to her brother, she answered it.

"Hello?"

Silence.

"H-Hello?"

Still nothing.

"If this is some kind of prank, it's not funny."

A faint sound reached her ears and she froze, listening hard. Chills tracked down her spine when she realized it was the sound of breathing, a man's breathing to be exact.

"Wh-who the fuck are you?" She demanded, voice shaking despite her attempt to sound calm.

The only reply she recieved was the click of the call ending and the beeping of the dial tone as she stared numbly at her phone, feelings of fear and worry multiplying within her.

No further incidents marked the day, but Yangmi remained on edge throughout and had uneasy dreams that night.

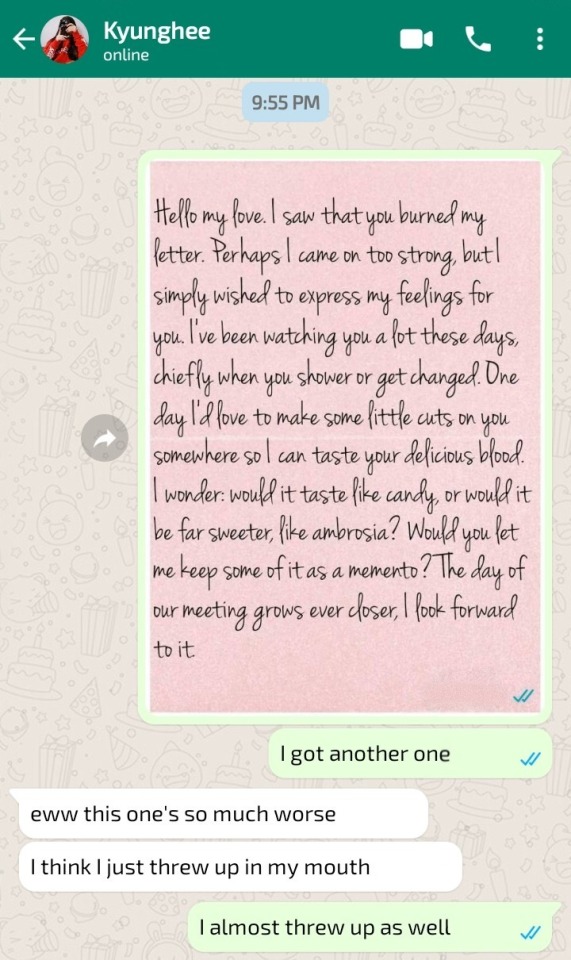

Next morning she woke to a sight that filled her with dread: another envelope shoved through the crack in her window, this one a soft pink colour. No part of her wanted to open it, but she felt she should know its contents before showing it to her brother.

So, despite her fear, she opened it.

"Hello my love. I saw that you burned my letter. Perhaps I came on too strong, but I simply wished to express my feelings for you. I've been watching you a lot these days, chiefly when you shower or get changed. One day I'd love to make some little cuts on you somewhere so I can taste your delicious blood. I wonder: would it taste like candy, or would it be far sweeter, like ambrosia? Would you let me keep some of it as a memento? The day of our meeting grows ever closer, I look forward to it."

Yangmi felt her mouth drop open. Bile rose in her throat and she gagged, disgusted by what she had just read. Opening her drawer, she closed her hand around the box of matches, and then remembered she was going to show Hongjoong first. With a sigh she threw the pink paper onto her nightstand and pulled out her phone, settling in to await her brother's return.

A few hours later he returned. Yangmi pocketed her phone, grabbing the envelope and letter off her nightstand before exiting her room.

"Joong, can we talk for a minute?"

He eyed her suspiciously. "About what?"

"I found this shoved through a crack in my window this morning." She said, handing him the envelope. "I'm afraid someone might be stalking me."

Hongjoong takes the envelope, pulling out the letter and reading it in silence. When he finished, he gazed at Yangmi with obvious disgust in his eyes and she knew at once her efforts had been in vain.

"You just can't resist, can you? Acting like a fucking child seems to thrill you, but I'm telling you this childish behavior needs to stop right this instant. You think I'm fooled by your frightened act or your fake little letters? Think again!"

Yangmi gaped at him, hurt and offended that he would think such horrid things of her. She opened her mouth to protest, but Hongjoong continued speaking.

"If you ever try to take this trumped up story to the authorities, I'll make sure you're locked in an asylum for the rest of your pathetic life. This is sick, Yangmi, and it's not funny at all."

Enraged, Yangmi snatched up the letter and retreated to her room, locking the door behind her. She took a picture of the letter for Kyunghee, then burned the letter as she had the first one. After that, she pulled out her phone and filled her friend in.

Turning off her phone, Yangmi slipped into her pajamas and climbed into bed. Turning off the light she fell into a troubled dream.

In her dream it came out that the sender of the disturbing was none other than Hongjoong himself, a plot to get her certified as insane and shipped off to an asylum. She was exposed to all manner of awful tortures in that asylum, on for it to end one day when Hongjoong came to visit her little padded room and murdered her in cold blood.The last thing she saw was him placing the knife in her hand to make it look like she had ended her own life.

Yangmi woke the next morning in a cold sweat, terror clinging to her bones.

«-Previous | Next-»

#thekpoparchives#kdiarynet#cacaokpop#ateez#wooyoung x oc#ateez smut#ateez angst#ateez horror#ateez hongjoong#ateez san#ateez wooyoung#maturefanfic#21+#au#fanfic

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mansour: While Democrats Pursue Impeachment, President Trump Builds Impressive Record of Accomplishments

Unable to talk about any actual accomplishments, and fearful of blowback from voters who didn’t elect them to “impeach the motherf***er,” Democrats have decided to use endless “repetition” of certain buzzwords to convince Americans that impeachment is necessary.

In a conference call Sunday night, Democratic Caucus Chairman Hakeem Jeffries “named six words that Democrats will use — ‘betrayal, abuse of power, national security’ — as they make the case that Trump abused his office,” Politico reports.

You have to hand it to the Dems. It’s not a bad plan. When you don’t have a logically consistent argument, the best strategy is to stick to buzzwords. And if you’re a Democrat, you can get away with it because the media will accept your buzzwords at face value.

On the right, we have “free trade” kamikazes, totally divorced from reality, reciting Panglossian platitudes about the glories of unfettered capitalism while their Wall Street benefactors strip-mine our industries and sell them to China (who, for their part, have re-engineered the Opium Wars.

We send them our supply chains. They send us fentanyl to zomb-ify the masses while they partner with our elites to rob us blind.) When we complained about the loss of jobs, they told us to enjoy the cheap products at Walmart and learn to code.

When the right isn’t invading countries or lecturing us about the national debt (which they’ve done nothing to reduce and are only too happy to run up if it means giving their donors a tax cut), they’re devising ways to “reform” the pension and medical fund that American workers have paid into their entire adult lives (because, if you’re Paul Ryan, nothing says “electoral landslide” like promising to gut Social Security and Medicare.)

They call themselves conservatives, but they failed to conserve our jobs, our communities, our defense supply chain, our culture, our religious heritage, our freedom of speech, and our own country’s borders.

This is the idiotic shell game Donald Trump upended. Again, consider the record:

To fight the opioid crisis, Trump signed into law the SUPPORT Act, the largest legislative package in history addressing a single drug crisis. He’s also beefed up funding for drug treatment, cracked down on prescription-drug abuse, and pressured China to cease its fentanyl trafficking as a requirement of any trade deal.

Trump got us out of the bogus Paris Climate Agreement (i.e. a sham treaty that allowed the world’s biggest polluter, China, to go on polluting while punishing us.)

He signed an executive order defending free speech on college campuses (i.e. the Orwellian indoctrination centers for future woke apparatchiks). Universities now risk losing federal funding if they fail to uphold the First Amendment.

He’s appointing constitutional conservatives to the federal judiciary at a record pace, recently reaching 150 appointments.

He picked two good Supreme Court justices. (And if you don’t think the Kavanaugh hearings were crazy enough, just wait till you see what happens if he gets to pick another one).

Despite Democrats’ refusal to work with him on nonpartisan healthcare reforms, Trump signed executive orders that have helped lower drug prices for the first time in half a century and keep health insurance premiums—which skyrocketed under Obama—relatively stable.

His Department of Justice has launched an antitrust probe against big tech giants who are busy censoring conservatives, violating our privacy, and interfering in our elections. In fact, Trump has brought global attention to the problem of Silicon Valley’s political bias and censorship, raising the status of the issue in America’s public discourse and in his speech before the United Nations.

This list could go on and on. You get the picture.

It’s the ultimate insult to injury that the Democrats want to impeach the man who promised to “Drain the Swamp” because he was attempting to “Drain the Swamp” by getting to the bottom of Russiagate and Bidengate.

Bidengate is just Clinton Cash 2.0—you know, the scandal that inspired all those “Drain the Swamp” chants.

So, if there is any confusion about Bidengate, let me clear this one up for the Democrats:

It was an abuse of power when Joe Biden, father of Hunter, threatened to withhold loan guarantees from Ukraine if the country didn’t fire the prosecutor investigating his son. Joe Biden’s kid-glove treatment of China—while his son’s firm was getting a $1.5 billion sweetheart deal from the state-owned bank of China—was a betrayal of his office that put our national security at risk.

How do you like those buzzwords, Dems?

The Democrat-Media Complex wants you to ignore everything I’ve listed above. But no matter what they say, you cannot ignore what Trump has done.

He has been winning for America, while the Democrat-Media Complex has been plotting revenge against him for their loss. They looked like fools on November 8, 2016, and they will never forgive him for that or risk it happening again.

I say, let’s make them look stupid again.

READ MORE STORIES ABOUT:

2020 Election Economy Politics Bidengate China Deep StateDemocrat Media ComplexDonald Trump Free Trade globalism immigration impeachment Make America Great Again Manufacturing Jobs trade war USMCA

0 notes

Text

Maxine Waters' Political Career Makes Her Uniquely Suited To Take On Donald Trump

Maxine Waters spends her weekends at home. For most people, this is not an unusual habit. But for Waters, it requires extra effort: Each Monday Congress has been in session over the past 26 years, she has embarked on a 2,300-mile commute from her home in Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., where she currently serves as one of the most powerful Democrats in the House of Representatives.

A pre-dawn, cross-country flight to head to work in D.C. is irritating business. Former staffers say the six-hour journey suits the 78-year-old congresswoman just about as well as you’d expect. Her 5 p.m. Monday meetings are notoriously abusive. Aides who have spent the weekend gathering Capitol Hill intelligence, studying the intricacies of securities law and trying to win new political allies report to the full staff in front of a one-woman firing squad.

“It’s definitely a situation that can be slightly intimidating,” said one former staffer, comparing the grillings to the Trump administration’s televised press conferences. “She interrupts, doesn’t let them finish, scolds them. These are people who are just trying to get her up to speed on what’s happening.”

Waters yells at staffers for things like making eye contact with other aides. She unceremoniously fires people who give presentations that don’t live up to her standards.

The scene, at first, might clash with the image of Waters that has taken off on the internet since the election of Donald Trump. The meme-ified image of “Auntie Maxine” ― a fearless, quirky black woman who may not be related to you, but whom you love and respect for her straight talk just the same ― has become a favorite of millennials and brought Waters’ Twitter account up to hundreds of thousands of followers. But, at a closer look, her staff meetings actually fit with her internet persona: Auntie Maxine, like many black women when it’s time to buckle down at work, isn’t about to play with you.

“There’s a genuineness,” said R. Eric Thomas, a columnist for Elle.com who has written several viral articles with headlines like “You Will Never, In Your Entire Life, Get The Best Of Maxine Waters.”

“With Maxine, she’s talking like everyone you respect in your life talks, but whom you wouldn’t expect to be in Washington,” he said. “If my mom and my aunt were running Washington, everyone would straighten up and fly right. I think a lot of people feel that way.”

And Waters’ comments about Trump have fit that bill.

“I think that he is disrespectful of most people,” Waters told The Huffington Post. “He has no respect for other human beings. He lies, he cannot be trusted, I don’t know what it means to sit down with someone like that who you cannot believe one word that they say once you get up by talking to them. I have no trust and no faith in him whatsoever.”

Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) said he helped coax Waters to come to Georgia for an upcoming event, given her overwhelming popularity in the black community. “She’s hard-edged, hard-nosed, hard-driving, firm in her beliefs, and she is an institution unto herself. African Americans adore her,” Johnson said.

Waters’ experience as a black woman in America gives the rage in her voice an added dose of authenticity. Waters has come about that anger honestly: Black people, particularly women, have generally been treated horribly throughout American history. Black men began serving as sheriffs, congressmen and senators as early as 1870, and black women often did a bulk of the work necessary to advance men into those positions and support them while in office. But it wasn’t until 1968 ― when Maxine Waters was 30 ― that Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman elected to Congress.

When Trump or his surrogates take on Waters, as they have since she began speaking out against his policies, the attacks come with a barely sheathed racist edge. Fox News host Bill O’Reilly recently mocked her “James Brown wig,” saying he wouldn’t listen to her concerns about Trump’s politics because of it.

In a viral response, Waters made clear who she is. “I’m a strong black woman, and I cannot be intimidated,” she said. “I cannot be thought to be afraid of Bill O’Reilly or anybody. And I’d like to say to women out there everywhere: Don’t allow these right-wing talking heads, these dishonorable people, to intimidate you or scare you. Be who you are. Do what you do. And let us get on with discussing the real issues of this country.”

The O’Reillys of the world see Waters as nothing but an angry black woman. And she is, indeed, an angry black woman ― rightfully and unapologetically so.

youtube

“It’s not good advice to get in a fight with Maxine Waters,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, a former LA county supervisor who has known Waters for decades and who noted that O’Reilly apologized with uncharacteristic speed. “What’s the ‘Man of La Mancha’ quote? ‘Whether the stone hits the pitcher or the pitcher hits the stone, it’s going to be bad for the pitcher.’”

Waters’ anger wards off rivals. It enhances her moral authority. And it comforts and amplifies her often equally angry constituents.

“She can sometimes be animated, and I think people might think that that is evidence of lack of control,” said Rep. Stephen Lynch (D-Mass.), who has long served with Waters on the Financial Services Committee. “But it is not. It is quite calculated, and most of the time, it is very effective.”

* * *

Maxine Waters, one of 13 children, was born in 1938 in St. Louis, a city that was a capital of black culture and politics at the time. Waters’ high school yearbook predicted she’d become speaker of the House ― an impressively optimistic prediction, given that she graduated a decade before the Voting Rights Act mandated African Americans’ right to vote.

Waters started her family at a young age and had two children before moving west to LA and finding a gig as a service representative for Pacific Telephone, while working her way slowly toward a sociology degree. She later became a supervisor for a head start program in Watts, a black working-class neighborhood in South Los Angeles ― her first foray into professional public service.

One night in August 1965, cops pulled over an African-American motorist in Watts and beat him badly. Then, as now, police violence was a not-unheard-of occurrence. But there’s no telling when a single moment becomes a spark that lights a fire, and this one lit up Watts. The neighborhood erupted in protest, leading to what became known as the Watts Rebellion — or, to white America, the Watts Riots.

Following the rebellion, a small group of black politicians and organizers came together at a crucial meeting in Bakersfield in 1966. Waters, whose activism in the community was becoming increasingly high profile, was among them. From that meeting came a long-term, statewide wave of black politicians from California, focused on improving conditions for communities of color.

“Anybody who became ‘somebody’ was there,” James Richardson, a Sacramento Bee reporter who covered much of Waters’ early career, said of the Bakersfield summit. “They plotted over how to gain electoral power and it was a watershed moment that wasn’t really seen.”

Waters’ work in the community eventually led to a gig that would define her approach to politics the rest of her life: serving as a top aide to LA Councilman David Cunningham Jr. When she’s been asked since why she continues flying cross-country every single week, despite facing no political threat to her seat, she recalls what she learned as a chief deputy to Cunningham: the importance of constituent service. In 1976, Waters ran for and won a seat in the California State Assembly. She has been in elected office ever since.

“It’s as if she never left the public housing projects in Watts in all of her life,” said her longtime ally Willie Brown, a speaker of the Assembly who went on to become mayor of San Francisco.

* * *

Waters has been in political life long enough to see the Democratic Party transform several times over. She is, in many ways, a holdover from another time. But the world seems to be coming full circle. Today, nearly every Democrat identifies as “progressive,” but decades ago the word had a specific meaning and referred to a movement launched in opposition to urban machine politicians who relied on transactional politics and constituent service to consolidate power.

Progressives prioritized anti-corruption and the integrity of the political process. The penny-ante palm greasing of the city machine gave way to the sanitized, large-scale corruption of national politics by corporate money. With government watchdogs on the prowl, politicians lost the ability to bestow jobs and other benefits on supporters in the community. It was all well-intentioned, but as the power to better the community moved to the private sector and out of politicians’ hands, quality of life in the community steadily declined.

Waters is not a good-government progressive. She is an old-school liberal, one who believes that outcomes matter more than process. She prides herself on constituent service. And she often wins.

“It is hard to think of any single member of Congress who has done more than Maxine to protect the financial reforms and prevent another financial crisis,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). “Her work touches every family in America. She’s really been good.”

* * *

Waters’ keen sense of public opinion is as strong as that of any member of Congress. She has leaned right into the Auntie Maxine persona as yet another method of relating to constituents. At a private meeting of her House colleagues earlier this year, Democrats were debating the stunning level of grassroots energy around the country — and how it could be harnessed to regain power. Waters rose to address her colleagues, stressing the importance of learning the language the kids use today — and explained the meaning of the phrase ��stay woke.” (The phrase originated as a way for black activists to remind each other of systemic inequality; it has since evolved to describe anybody who professes concern for social justice ― up to and including ride-share companies.)

Waters’ grassroots touch — combined with her grueling work ethic and endless frequent flyer miles — is what allowed Waters to know long before national groups, and before federal regulators, that big banks were engaging in rampant mortgage servicing fraud and foreclosure scams. It has helped her stay far ahead of the national curve on issues such as mass incarceration, the drug war and police brutality. And by sensing — and leaping to satiate — a tremendous hunger among the Democratic base to not only delegitimize and de-normalize Trump, but to actually impeach him, she’s fueled her latest star turn.

“Maxine is a grassroots person,” said Yaroslavsky, the former LA county supervisor. “She’s as comfortable in the district as she is in the committee. ... You learn to take care of the people who pay your salary. And sometimes she steps on toes doing that, but usually she takes the populist position because that’s what she thinks is her role.”

“Maxine was a tough person. You didn’t cross her. She could give a fiery speech on the floor and send your bill to the dumper. Some nicknamed her ‘Mad Max’ behind her back,” Richardson said of her state Assembly years. “She would represent [Assembly Speaker Willie Brown] in budget meetings, so everyone knew that Maxine was to be taken seriously because she was speaking for him. And for herself.”

youtube

Waters’ crowning achievement in the Assembly was a bill she co-authored with Brown, who’d also been at the Bakersfield meeting, and convinced Republican Gov. George Deukmejian to sign. It divested California’s mammoth pension system from South African interests in protest of apartheid. Convincing the governor was difficult, Brown reported, but Waters got to work, demonstrating an interest in issues that Deukmejian cared about, such as farming regulations in California’s Central Valley, coastline and water resources in Los Angeles. She was able to demonstrate her commitment to his issues enough to engender the goodwill necessary to receive his support, Brown said. It was in stark contrast to the image of the blustering demagogue, and it’s one colleagues said they’ve seen over and over in the years since. The coastal and farming policy insights she picked up in pursuit of Nelson Mandela’s freedom, indeed, would become handy as she helped shape a flood insurance bill 30 years later.

(Brown is selling himself a bit short, as he always played a major role. Richardson notes that the speaker effectively appealed to Deukmejian’s family history. The governor, who was of Armenian descent, lost family in the Armenian genocide.)

California blocked its huge pension fund from investing in South African interests in 1986. It was a watershed moment in the anti-apartheid movement, and Mandela was released in 1990. Brown said Mandela traveled to California during his first United States tour following his release to thank Waters for her part in freeing him. “Maxine’s history is replete with successes, but none greater than freeing Nelson Mandela,” Brown said.

That may sound like too much credit for a collective action, but Brown says Waters’ move set off a chain reaction ― as she hoped it would ― that led to his release. “Nelson Mandela was freed because Maxine Waters orchestrated a process in the legislature to divest our pension fund on the basis of apartheid,” Brown said. “This was quickly followed by Congress and other municipalities and it led clearly to the ultimate freedom of Nelson Mandela.”

Indeed, Waters’ dominance of the Assembly in the 1980s is hard to overstate. Nobody who saw the authority the diminutive young woman wielded in the chamber is surprised at what she has become today. “The things going on in California in the ‘80s make DC look like nothing,” Richardson said. “We’d go months without a government, everything shut down, over pensions and benefits for teachers and the poor.”

Waters withstood all of that. Persisted, even, you could say.

“That’s her style. She will not be intimidated,” Richardson said, echoing language Waters used in response to O’Reilly’s recent racist attack on her.

Although Waters worked the inside game in the Assembly, she held on to her outsider status throughout the 1980s, twice going against the party establishment in backing Jesse Jackson’s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. When he fell short, she floated the possibility that black voters should support a third party if Democrats remained unresponsive to their concerns. And so when she ran for Congress in 1990, the party endorsed her primary opponent ― but Waters won anyway.

She has been fighting established power ever since, and her natural impulse with Trump taking the White House this year was to charge right at him. Immediately after the election, the Democratic Party was caught in a debate over how to approach a Trump presidency. Would they try to work with him where possible, or resist his agenda across the board? Waters, who boycotted his inauguration, seems to see the answer as simple and has promised a full-blown rejection of Trump.

“As I said earlier to someone I was talking to,” Waters told HuffPost, “I became very offended by him during his campaign the way he mocked disabled journalists, the way he talked about grabbing women by their private parts ... the way he stalked Hillary Clinton at the debate that I attended in Missouri where he circled her as she was standing trying to give her petition on the issues. The way he has praised [Russian President Vladimir] Putin and talked about the great leader he was. And the way that he pushed back even on Bill O’Reilly on the Fox show when Bill O’Reilly said in so many words, ‘Why are you so supportive of Putin? He’s a killer.’ And he said, ‘so what,’ in so many words, ‘[it’s] the United States, people get killed here all the time’ or something like that.”

“I think that for the future, we have to deal with this administration and organizing to try and take back the House and the White House,” she continued.

Mikael Moore, Waters’ grandson who served as a longtime aide to her in Congress, put it succinctly: “She runs toward the fight.”

I never ever contemplated attending the inauguration or any activities associated w/ @realDonaldTrump. I wouldn't waste my time.

— Maxine Waters (@MaxineWaters) January 15, 2017

“She is operating no differently than she did prior to Trump’s arrival,” Brown said. “She generated just as much attention during the Bush years. [During Obama’s and Clinton’s terms] she had the great joy of not having to do that.”

During the 2016 election, Waters clashed with Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders when she backed Hillary Clinton in the primary instead. Some of her staffers were frustrated by Waters’ early enthusiasm for Clinton, whom they saw as much weaker on Waters’ signature issue of bank reform. When Sanders was invited to address the Democratic caucus in July 2016 — after the primary was effectively over, but while Sanders was continuing to campaign — some members of the Congressional Black Caucus, of which Waters is a member, heckled him.

The CBC has a long, fraught relationship with Wall Street, often allying with big banks for fundraising purposes (much like the rest of the party). And since 2013, Waters had been the banks’ chief adversary in leadership, warning members of the caucus that helping Wall Street could result in a lot of pain for their black constituents a few years down the line. But at the Sanders address, Waters gave her colleagues cover by taking on Sanders.

“Basically her question was, ‘Why do you keep talking about breaking up the banks when we already fixed this with Dodd-Frank?’” recalls one Democratic staffer who witnessed the confrontation.

This fed a narrative the Clinton campaign was trying to foster — Bernie was a dreamer who didn’t understand policy. Most members of Congress, of course, do not understand financial policy ― they defer to leaders on the Financial Services Committee. Here was the top Democrat on that committee saying Sanders didn’t get it. It was powerful. But Waters’ own staffers knew their boss was twisting the policy. “Too big to fail” is alive and well in American banking.

Dodd-Frank gave regulators the tools to fix the problem, but they haven’t used them, and Sanders wanted to force their hands. “It was pretty deflating,” one former Waters staffer says.

* * *

Waters combined her fierce nature with her constituent savvy after the 1992 LA riots, with a response that would come to define her career: She took a hard line with colleagues, but used a soft touch with her those who would vote for her.

In April 1992, communities across South Los Angeles, enraged by the acquittals of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, launched what locals still refer to as an uprising — known nationally as the LA riots.

In the wake of the chaos, Waters, who was then in her first term in Congress, showed up uninvited to a meeting President George H.W. Bush had called to discuss “urban problems,” according to a New York Times report.

“I’ve been out here trying to define these issues,” she told Speaker Thomas S. Foley. “I don’t intend to be excluded or dismissed. We have an awful lot to say.”

Back home, she struck a more poetic note, addressing constituents in a letter reprinted by the Los Angeles Times. In it, she employed a canny understanding of the zeitgeist and the language of the moment:

My dear children, my friends, my brothers, life is sometimes cold-blooded and rotten. And it seems nobody, nobody cares.

But there are the good times, the happy moments.

I’m talking about the special times when a baby is born and when gospel music sounds good on Sunday morning. When Cube is kickin’ and Public Enemy is runnin’ it. When peach cobbler and ice cream tastes too good, the down-home blues makes you sing and shout, and someone simply saying, ‘I love you’ makes you want to cry.

Her letter went on to condemn police brutality, predatory lending in communities of color, for-profit schools and a racist justice system. Save a few names, it could have been written today.

In 1994, Republicans won control of Congress and Waters immediately joined the resistance. When activists from the affordable housing group ACORN..

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oKtPbP

0 notes

Text

Maxine Waters' Political Career Makes Her Uniquely Suited To Take On Donald Trump

Maxine Waters spends her weekends at home. For most people, this is not an unusual habit. But for Waters, it requires extra effort: Each Monday Congress has been in session over the past 26 years, she has embarked on a 2,300-mile commute from her home in Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., where she currently serves as one of the most powerful Democrats in the House of Representatives.

A pre-dawn, cross-country flight to head to work in D.C. is irritating business. Former staffers say the six-hour journey suits the 78-year-old congresswoman just about as well as you’d expect. Her 5 p.m. Monday meetings are notoriously abusive. Aides who have spent the weekend gathering Capitol Hill intelligence, studying the intricacies of securities law and trying to win new political allies report to the full staff in front of a one-woman firing squad.

“It’s definitely a situation that can be slightly intimidating,” said one former staffer, comparing the grillings to the Trump administration’s televised press conferences. “She interrupts, doesn’t let them finish, scolds them. These are people who are just trying to get her up to speed on what’s happening.”

Waters yells at staffers for things like making eye contact with other aides. She unceremoniously fires people who give presentations that don’t live up to her standards.

The scene, at first, might clash with the image of Waters that has taken off on the internet since the election of Donald Trump. The meme-ified image of “Auntie Maxine” ― a fearless, quirky black woman who may not be related to you, but whom you love and respect for her straight talk just the same ― has become a favorite of millennials and brought Waters’ Twitter account up to hundreds of thousands of followers. But, at a closer look, her staff meetings actually fit with her internet persona: Auntie Maxine, like many black women when it’s time to buckle down at work, isn’t about to play with you.

“There’s a genuineness,” said R. Eric Thomas, a columnist for Elle.com who has written several viral articles with headlines like “You Will Never, In Your Entire Life, Get The Best Of Maxine Waters.”

“With Maxine, she’s talking like everyone you respect in your life talks, but whom you wouldn’t expect to be in Washington,” he said. “If my mom and my aunt were running Washington, everyone would straighten up and fly right. I think a lot of people feel that way.”

And Waters’ comments about Trump have fit that bill.

“I think that he is disrespectful of most people,” Waters told The Huffington Post. “He has no respect for other human beings. He lies, he cannot be trusted, I don’t know what it means to sit down with someone like that who you cannot believe one word that they say once you get up by talking to them. I have no trust and no faith in him whatsoever.”

Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) said he helped coax Waters to come to Georgia for an upcoming event, given her overwhelming popularity in the black community. “She’s hard-edged, hard-nosed, hard-driving, firm in her beliefs, and she is an institution unto herself. African Americans adore her,” Johnson said.

Waters’ experience as a black woman in America gives the rage in her voice an added dose of authenticity. Waters has come about that anger honestly: Black people, particularly women, have generally been treated horribly throughout American history. Black men began serving as sheriffs, congressmen and senators as early as 1870, and black women often did a bulk of the work necessary to advance men into those positions and support them while in office. But it wasn’t until 1968 ― when Maxine Waters was 30 ― that Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman elected to Congress.

When Trump or his surrogates take on Waters, as they have since she began speaking out against his policies, the attacks come with a barely sheathed racist edge. Fox News host Bill O’Reilly recently mocked her “James Brown wig,” saying he wouldn’t listen to her concerns about Trump’s politics because of it.

In a viral response, Waters made clear who she is. “I’m a strong black woman, and I cannot be intimidated,” she said. “I cannot be thought to be afraid of Bill O’Reilly or anybody. And I’d like to say to women out there everywhere: Don’t allow these right-wing talking heads, these dishonorable people, to intimidate you or scare you. Be who you are. Do what you do. And let us get on with discussing the real issues of this country.”

The O’Reillys of the world see Waters as nothing but an angry black woman. And she is, indeed, an angry black woman ― rightfully and unapologetically so.

youtube

“It’s not good advice to get in a fight with Maxine Waters,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, a former LA county supervisor who has known Waters for decades and who noted that O’Reilly apologized with uncharacteristic speed. “What’s the ‘Man of La Mancha’ quote? ‘Whether the stone hits the pitcher or the pitcher hits the stone, it’s going to be bad for the pitcher.’”

Waters’ anger wards off rivals. It enhances her moral authority. And it comforts and amplifies her often equally angry constituents.

“She can sometimes be animated, and I think people might think that that is evidence of lack of control,” said Rep. Stephen Lynch (D-Mass.), who has long served with Waters on the Financial Services Committee. “But it is not. It is quite calculated, and most of the time, it is very effective.”

* * *

Maxine Waters, one of 13 children, was born in 1938 in St. Louis, a city that was a capital of black culture and politics at the time. Waters’ high school yearbook predicted she’d become speaker of the House ― an impressively optimistic prediction, given that she graduated a decade before the Voting Rights Act mandated African Americans’ right to vote.

Waters started her family at a young age and had two children before moving west to LA and finding a gig as a service representative for Pacific Telephone, while working her way slowly toward a sociology degree. She later became a supervisor for a head start program in Watts, a black working-class neighborhood in South Los Angeles ― her first foray into professional public service.

One night in August 1965, cops pulled over an African-American motorist in Watts and beat him badly. Then, as now, police violence was a not-unheard-of occurrence. But there’s no telling when a single moment becomes a spark that lights a fire, and this one lit up Watts. The neighborhood erupted in protest, leading to what became known as the Watts Rebellion — or, to white America, the Watts Riots.

Following the rebellion, a small group of black politicians and organizers came together at a crucial meeting in Bakersfield in 1966. Waters, whose activism in the community was becoming increasingly high profile, was among them. From that meeting came a long-term, statewide wave of black politicians from California, focused on improving conditions for communities of color.

“Anybody who became ‘somebody’ was there,” James Richardson, a Sacramento Bee reporter who covered much of Waters’ early career, said of the Bakersfield summit. “They plotted over how to gain electoral power and it was a watershed moment that wasn’t really seen.”

Waters’ work in the community eventually led to a gig that would define her approach to politics the rest of her life: serving as a top aide to LA Councilman David Cunningham Jr. When she’s been asked since why she continues flying cross-country every single week, despite facing no political threat to her seat, she recalls what she learned as a chief deputy to Cunningham: the importance of constituent service. In 1976, Waters ran for and won a seat in the California State Assembly. She has been in elected office ever since.

“It’s as if she never left the public housing projects in Watts in all of her life,” said her longtime ally Willie Brown, a speaker of the Assembly who went on to become mayor of San Francisco.

* * *

Waters has been in political life long enough to see the Democratic Party transform several times over. She is, in many ways, a holdover from another time. But the world seems to be coming full circle. Today, nearly every Democrat identifies as “progressive,” but decades ago the word had a specific meaning and referred to a movement launched in opposition to urban machine politicians who relied on transactional politics and constituent service to consolidate power.

Progressives prioritized anti-corruption and the integrity of the political process. The penny-ante palm greasing of the city machine gave way to the sanitized, large-scale corruption of national politics by corporate money. With government watchdogs on the prowl, politicians lost the ability to bestow jobs and other benefits on supporters in the community. It was all well-intentioned, but as the power to better the community moved to the private sector and out of politicians’ hands, quality of life in the community steadily declined.

Waters is not a good-government progressive. She is an old-school liberal, one who believes that outcomes matter more than process. She prides herself on constituent service. And she often wins.

“It is hard to think of any single member of Congress who has done more than Maxine to protect the financial reforms and prevent another financial crisis,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). “Her work touches every family in America. She’s really been good.”

* * *

Waters’ keen sense of public opinion is as strong as that of any member of Congress. She has leaned right into the Auntie Maxine persona as yet another method of relating to constituents. At a private meeting of her House colleagues earlier this year, Democrats were debating the stunning level of grassroots energy around the country — and how it could be harnessed to regain power. Waters rose to address her colleagues, stressing the importance of learning the language the kids use today — and explained the meaning of the phrase “stay woke.” (The phrase originated as a way for black activists to remind each other of systemic inequality; it has since evolved to describe anybody who professes concern for social justice ― up to and including ride-share companies.)

Waters’ grassroots touch — combined with her grueling work ethic and endless frequent flyer miles — is what allowed Waters to know long before national groups, and before federal regulators, that big banks were engaging in rampant mortgage servicing fraud and foreclosure scams. It has helped her stay far ahead of the national curve on issues such as mass incarceration, the drug war and police brutality. And by sensing — and leaping to satiate — a tremendous hunger among the Democratic base to not only delegitimize and de-normalize Trump, but to actually impeach him, she’s fueled her latest star turn.

“Maxine is a grassroots person,” said Yaroslavsky, the former LA county supervisor. “She’s as comfortable in the district as she is in the committee. ... You learn to take care of the people who pay your salary. And sometimes she steps on toes doing that, but usually she takes the populist position because that’s what she thinks is her role.”

“Maxine was a tough person. You didn’t cross her. She could give a fiery speech on the floor and send your bill to the dumper. Some nicknamed her ‘Mad Max’ behind her back,” Richardson said of her state Assembly years. “She would represent [Assembly Speaker Willie Brown] in budget meetings, so everyone knew that Maxine was to be taken seriously because she was speaking for him. And for herself.”

youtube

Waters’ crowning achievement in the Assembly was a bill she co-authored with Brown, who’d also been at the Bakersfield meeting, and convinced Republican Gov. George Deukmejian to sign. It divested California’s mammoth pension system from South African interests in protest of apartheid. Convincing the governor was difficult, Brown reported, but Waters got to work, demonstrating an interest in issues that Deukmejian cared about, such as farming regulations in California’s Central Valley, coastline and water resources in Los Angeles. She was able to demonstrate her commitment to his issues enough to engender the goodwill necessary to receive his support, Brown said. It was in stark contrast to the image of the blustering demagogue, and it’s one colleagues said they’ve seen over and over in the years since. The coastal and farming policy insights she picked up in pursuit of Nelson Mandela’s freedom, indeed, would become handy as she helped shape a flood insurance bill 30 years later.

(Brown is selling himself a bit short, as he always played a major role. Richardson notes that the speaker effectively appealed to Deukmejian’s family history. The governor, who was of Armenian descent, lost family in the Armenian genocide.)

California blocked its huge pension fund from investing in South African interests in 1986. It was a watershed moment in the anti-apartheid movement, and Mandela was released in 1990. Brown said Mandela traveled to California during his first United States tour following his release to thank Waters for her part in freeing him. “Maxine’s history is replete with successes, but none greater than freeing Nelson Mandela,” Brown said.

That may sound like too much credit for a collective action, but Brown says Waters’ move set off a chain reaction ― as she hoped it would ― that led to his release. “Nelson Mandela was freed because Maxine Waters orchestrated a process in the legislature to divest our pension fund on the basis of apartheid,” Brown said. “This was quickly followed by Congress and other municipalities and it led clearly to the ultimate freedom of Nelson Mandela.”

Indeed, Waters’ dominance of the Assembly in the 1980s is hard to overstate. Nobody who saw the authority the diminutive young woman wielded in the chamber is surprised at what she has become today. “The things going on in California in the ‘80s make DC look like nothing,” Richardson said. “We’d go months without a government, everything shut down, over pensions and benefits for teachers and the poor.”

Waters withstood all of that. Persisted, even, you could say.

“That’s her style. She will not be intimidated,” Richardson said, echoing language Waters used in response to O’Reilly’s recent racist attack on her.

Although Waters worked the inside game in the Assembly, she held on to her outsider status throughout the 1980s, twice going against the party establishment in backing Jesse Jackson’s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. When he fell short, she floated the possibility that black voters should support a third party if Democrats remained unresponsive to their concerns. And so when she ran for Congress in 1990, the party endorsed her primary opponent ― but Waters won anyway.

She has been fighting established power ever since, and her natural impulse with Trump taking the White House this year was to charge right at him. Immediately after the election, the Democratic Party was caught in a debate over how to approach a Trump presidency. Would they try to work with him where possible, or resist his agenda across the board? Waters, who boycotted his inauguration, seems to see the answer as simple and has promised a full-blown rejection of Trump.

“As I said earlier to someone I was talking to,” Waters told HuffPost, “I became very offended by him during his campaign the way he mocked disabled journalists, the way he talked about grabbing women by their private parts ... the way he stalked Hillary Clinton at the debate that I attended in Missouri where he circled her as she was standing trying to give her petition on the issues. The way he has praised [Russian President Vladimir] Putin and talked about the great leader he was. And the way that he pushed back even on Bill O’Reilly on the Fox show when Bill O’Reilly said in so many words, ‘Why are you so supportive of Putin? He’s a killer.’ And he said, ‘so what,’ in so many words, ‘[it’s] the United States, people get killed here all the time’ or something like that.”

“I think that for the future, we have to deal with this administration and organizing to try and take back the House and the White House,” she continued.

Mikael Moore, Waters’ grandson who served as a longtime aide to her in Congress, put it succinctly: “She runs toward the fight.”

I never ever contemplated attending the inauguration or any activities associated w/ @realDonaldTrump. I wouldn't waste my time.

— Maxine Waters (@MaxineWaters) January 15, 2017

“She is operating no differently than she did prior to Trump’s arrival,” Brown said. “She generated just as much attention during the Bush years. [During Obama’s and Clinton’s terms] she had the great joy of not having to do that.”

During the 2016 election, Waters clashed with Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders when she backed Hillary Clinton in the primary instead. Some of her staffers were frustrated by Waters’ early enthusiasm for Clinton, whom they saw as much weaker on Waters’ signature issue of bank reform. When Sanders was invited to address the Democratic caucus in July 2016 — after the primary was effectively over, but while Sanders was continuing to campaign — some members of the Congressional Black Caucus, of which Waters is a member, heckled him.

The CBC has a long, fraught relationship with Wall Street, often allying with big banks for fundraising purposes (much like the rest of the party). And since 2013, Waters had been the banks’ chief adversary in leadership, warning members of the caucus that helping Wall Street could result in a lot of pain for their black constituents a few years down the line. But at the Sanders address, Waters gave her colleagues cover by taking on Sanders.

“Basically her question was, ‘Why do you keep talking about breaking up the banks when we already fixed this with Dodd-Frank?’” recalls one Democratic staffer who witnessed the confrontation.

This fed a narrative the Clinton campaign was trying to foster — Bernie was a dreamer who didn’t understand policy. Most members of Congress, of course, do not understand financial policy ― they defer to leaders on the Financial Services Committee. Here was the top Democrat on that committee saying Sanders didn’t get it. It was powerful. But Waters’ own staffers knew their boss was twisting the policy. “Too big to fail” is alive and well in American banking.

Dodd-Frank gave regulators the tools to fix the problem, but they haven’t used them, and Sanders wanted to force their hands. “It was pretty deflating,” one former Waters staffer says.

* * *

Waters combined her fierce nature with her constituent savvy after the 1992 LA riots, with a response that would come to define her career: She took a hard line with colleagues, but used a soft touch with her those who would vote for her.

In April 1992, communities across South Los Angeles, enraged by the acquittals of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, launched what locals still refer to as an uprising — known nationally as the LA riots.

In the wake of the chaos, Waters, who was then in her first term in Congress, showed up uninvited to a meeting President George H.W. Bush had called to discuss “urban problems,” according to a New York Times report.

“I’ve been out here trying to define these issues,” she told Speaker Thomas S. Foley. “I don’t intend to be excluded or dismissed. We have an awful lot to say.”

Back home, she struck a more poetic note, addressing constituents in a letter reprinted by the Los Angeles Times. In it, she employed a canny understanding of the zeitgeist and the language of the moment:

My dear children, my friends, my brothers, life is sometimes cold-blooded and rotten. And it seems nobody, nobody cares.

But there are the good times, the happy moments.

I’m talking about the special times when a baby is born and when gospel music sounds good on Sunday morning. When Cube is kickin’ and Public Enemy is runnin’ it. When peach cobbler and ice cream tastes too good, the down-home blues makes you sing and shout, and someone simply saying, ‘I love you’ makes you want to cry.

Her letter went on to condemn police brutality, predatory lending in communities of color, for-profit schools and a racist justice system. Save a few names, it could have been written today.

In 1994, Republicans won control of Congress and Waters immediately joined the resistance. When activists from the affordable housing group ACORN..

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oKtPbP

0 notes

Text

Maxine Waters' Political Career Makes Her Uniquely Suited To Take On Donald Trump

Maxine Waters spends her weekends at home. For most people, this is not an unusual habit. But for Waters, it requires extra effort: Each Monday Congress has been in session over the past 26 years, she has embarked on a 2,300-mile commute from her home in Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., where she currently serves as one of the most powerful Democrats in the House of Representatives.

A pre-dawn, cross-country flight to head to work in D.C. is irritating business. Former staffers say the six-hour journey suits the 78-year-old congresswoman just about as well as you’d expect. Her 5 p.m. Monday meetings are notoriously abusive. Aides who have spent the weekend gathering Capitol Hill intelligence, studying the intricacies of securities law and trying to win new political allies report to the full staff in front of a one-woman firing squad.

“It’s definitely a situation that can be slightly intimidating,” said one former staffer, comparing the grillings to the Trump administration’s televised press conferences. “She interrupts, doesn’t let them finish, scolds them. These are people who are just trying to get her up to speed on what’s happening.”

Waters yells at staffers for things like making eye contact with other aides. She unceremoniously fires people who give presentations that don’t live up to her standards.

The scene, at first, might clash with the image of Waters that has taken off on the internet since the election of Donald Trump. The meme-ified image of “Auntie Maxine” ― a fearless, quirky black woman who may not be related to you, but whom you love and respect for her straight talk just the same ― has become a favorite of millennials and brought Waters’ Twitter account up to hundreds of thousands of followers. But, at a closer look, her staff meetings actually fit with her internet persona: Auntie Maxine, like many black women when it’s time to buckle down at work, isn’t about to play with you.

“There’s a genuineness,” said R. Eric Thomas, a columnist for Elle.com who has written several viral articles with headlines like “You Will Never, In Your Entire Life, Get The Best Of Maxine Waters.”

“With Maxine, she’s talking like everyone you respect in your life talks, but whom you wouldn’t expect to be in Washington,” he said. “If my mom and my aunt were running Washington, everyone would straighten up and fly right. I think a lot of people feel that way.”

And Waters’ comments about Trump have fit that bill.

“I think that he is disrespectful of most people,” Waters told The Huffington Post. “He has no respect for other human beings. He lies, he cannot be trusted, I don’t know what it means to sit down with someone like that who you cannot believe one word that they say once you get up by talking to them. I have no trust and no faith in him whatsoever.”

Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) said he helped coax Waters to come to Georgia for an upcoming event, given her overwhelming popularity in the black community. “She’s hard-edged, hard-nosed, hard-driving, firm in her beliefs, and she is an institution unto herself. African Americans adore her,” Johnson said.

Waters’ experience as a black woman in America gives the rage in her voice an added dose of authenticity. Waters has come about that anger honestly: Black people, particularly women, have generally been treated horribly throughout American history. Black men began serving as sheriffs, congressmen and senators as early as 1870, and black women often did a bulk of the work necessary to advance men into those positions and support them while in office. But it wasn’t until 1968 ― when Maxine Waters was 30 ― that Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman elected to Congress.

When Trump or his surrogates take on Waters, as they have since she began speaking out against his policies, the attacks come with a barely sheathed racist edge. Fox News host Bill O’Reilly recently mocked her “James Brown wig,” saying he wouldn’t listen to her concerns about Trump’s politics because of it.

In a viral response, Waters made clear who she is. “I’m a strong black woman, and I cannot be intimidated,” she said. “I cannot be thought to be afraid of Bill O’Reilly or anybody. And I’d like to say to women out there everywhere: Don’t allow these right-wing talking heads, these dishonorable people, to intimidate you or scare you. Be who you are. Do what you do. And let us get on with discussing the real issues of this country.”

The O’Reillys of the world see Waters as nothing but an angry black woman. And she is, indeed, an angry black woman ― rightfully and unapologetically so.

youtube

“It’s not good advice to get in a fight with Maxine Waters,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, a former LA county supervisor who has known Waters for decades and who noted that O’Reilly apologized with uncharacteristic speed. “What’s the ‘Man of La Mancha’ quote? ‘Whether the stone hits the pitcher or the pitcher hits the stone, it’s going to be bad for the pitcher.’”

Waters’ anger wards off rivals. It enhances her moral authority. And it comforts and amplifies her often equally angry constituents.

“She can sometimes be animated, and I think people might think that that is evidence of lack of control,” said Rep. Stephen Lynch (D-Mass.), who has long served with Waters on the Financial Services Committee. “But it is not. It is quite calculated, and most of the time, it is very effective.”

* * *

Maxine Waters, one of 13 children, was born in 1938 in St. Louis, a city that was a capital of black culture and politics at the time. Waters’ high school yearbook predicted she’d become speaker of the House ― an impressively optimistic prediction, given that she graduated a decade before the Voting Rights Act mandated African Americans’ right to vote.

Waters started her family at a young age and had two children before moving west to LA and finding a gig as a service representative for Pacific Telephone, while working her way slowly toward a sociology degree. She later became a supervisor for a head start program in Watts, a black working-class neighborhood in South Los Angeles ― her first foray into professional public service.

One night in August 1965, cops pulled over an African-American motorist in Watts and beat him badly. Then, as now, police violence was a not-unheard-of occurrence. But there’s no telling when a single moment becomes a spark that lights a fire, and this one lit up Watts. The neighborhood erupted in protest, leading to what became known as the Watts Rebellion — or, to white America, the Watts Riots.

Following the rebellion, a small group of black politicians and organizers came together at a crucial meeting in Bakersfield in 1966. Waters, whose activism in the community was becoming increasingly high profile, was among them. From that meeting came a long-term, statewide wave of black politicians from California, focused on improving conditions for communities of color.

“Anybody who became ‘somebody’ was there,” James Richardson, a Sacramento Bee reporter who covered much of Waters’ early career, said of the Bakersfield summit. “They plotted over how to gain electoral power and it was a watershed moment that wasn’t really seen.”

Waters’ work in the community eventually led to a gig that would define her approach to politics the rest of her life: serving as a top aide to LA Councilman David Cunningham Jr. When she’s been asked since why she continues flying cross-country every single week, despite facing no political threat to her seat, she recalls what she learned as a chief deputy to Cunningham: the importance of constituent service. In 1976, Waters ran for and won a seat in the California State Assembly. She has been in elected office ever since.

“It’s as if she never left the public housing projects in Watts in all of her life,” said her longtime ally Willie Brown, a speaker of the Assembly who went on to become mayor of San Francisco.

* * *

Waters has been in political life long enough to see the Democratic Party transform several times over. She is, in many ways, a holdover from another time. But the world seems to be coming full circle. Today, nearly every Democrat identifies as “progressive,” but decades ago the word had a specific meaning and referred to a movement launched in opposition to urban machine politicians who relied on transactional politics and constituent service to consolidate power.

Progressives prioritized anti-corruption and the integrity of the political process. The penny-ante palm greasing of the city machine gave way to the sanitized, large-scale corruption of national politics by corporate money. With government watchdogs on the prowl, politicians lost the ability to bestow jobs and other benefits on supporters in the community. It was all well-intentioned, but as the power to better the community moved to the private sector and out of politicians’ hands, quality of life in the community steadily declined.

Waters is not a good-government progressive. She is an old-school liberal, one who believes that outcomes matter more than process. She prides herself on constituent service. And she often wins.

“It is hard to think of any single member of Congress who has done more than Maxine to protect the financial reforms and prevent another financial crisis,” said Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.). “Her work touches every family in America. She’s really been good.”

* * *

Waters’ keen sense of public opinion is as strong as that of any member of Congress. She has leaned right into the Auntie Maxine persona as yet another method of relating to constituents. At a private meeting of her House colleagues earlier this year, Democrats were debating the stunning level of grassroots energy around the country — and how it could be harnessed to regain power. Waters rose to address her colleagues, stressing the importance of learning the language the kids use today — and explained the meaning of the phrase “stay woke.” (The phrase originated as a way for black activists to remind each other of systemic inequality; it has since evolved to describe anybody who professes concern for social justice ― up to and including ride-share companies.)

Waters’ grassroots touch — combined with her grueling work ethic and endless frequent flyer miles — is what allowed Waters to know long before national groups, and before federal regulators, that big banks were engaging in rampant mortgage servicing fraud and foreclosure scams. It has helped her stay far ahead of the national curve on issues such as mass incarceration, the drug war and police brutality. And by sensing — and leaping to satiate — a tremendous hunger among the Democratic base to not only delegitimize and de-normalize Trump, but to actually impeach him, she’s fueled her latest star turn.

“Maxine is a grassroots person,” said Yaroslavsky, the former LA county supervisor. “She’s as comfortable in the district as she is in the committee. ... You learn to take care of the people who pay your salary. And sometimes she steps on toes doing that, but usually she takes the populist position because that’s what she thinks is her role.”

“Maxine was a tough person. You didn’t cross her. She could give a fiery speech on the floor and send your bill to the dumper. Some nicknamed her ‘Mad Max’ behind her back,” Richardson said of her state Assembly years. “She would represent [Assembly Speaker Willie Brown] in budget meetings, so everyone knew that Maxine was to be taken seriously because she was speaking for him. And for herself.”

youtube

Waters’ crowning achievement in the Assembly was a bill she co-authored with Brown, who’d also been at the Bakersfield meeting, and convinced Republican Gov. George Deukmejian to sign. It divested California’s mammoth pension system from South African interests in protest of apartheid. Convincing the governor was difficult, Brown reported, but Waters got to work, demonstrating an interest in issues that Deukmejian cared about, such as farming regulations in California’s Central Valley, coastline and water resources in Los Angeles. She was able to demonstrate her commitment to his issues enough to engender the goodwill necessary to receive his support, Brown said. It was in stark contrast to the image of the blustering demagogue, and it’s one colleagues said they’ve seen over and over in the years since. The coastal and farming policy insights she picked up in pursuit of Nelson Mandela’s freedom, indeed, would become handy as she helped shape a flood insurance bill 30 years later.

(Brown is selling himself a bit short, as he always played a major role. Richardson notes that the speaker effectively appealed to Deukmejian’s family history. The governor, who was of Armenian descent, lost family in the Armenian genocide.)

California blocked its huge pension fund from investing in South African interests in 1986. It was a watershed moment in the anti-apartheid movement, and Mandela was released in 1990. Brown said Mandela traveled to California during his first United States tour following his release to thank Waters for her part in freeing him. “Maxine’s history is replete with successes, but none greater than freeing Nelson Mandela,” Brown said.