#harper's new monthly magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"The Withered Rose" by Edward Willard Watson, illustrated by Elenore Plaisted Abbott. From Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1901

via internet archive

#edward willard watson#elenore plaisted abbott#harper's new monthly magazine#vintage magazine#vintage illustration#illustration#illustration art#edwardian era#edwardian aesthetic#edwardian art#victorian art#victorian era#victorian aesthetic#roses#rose aesthetic#vintage poetry#vintage aesthetic#romantic aesthetic#e

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Witch’s Daughter” by Frederick Stuart Church (1842–1924), engraved by J. P. Davys. Lithograph was published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine [New York], vol. 67, issue 398 (July 1883), p. 164

#frederick stuart church#harpers new monthly magazine#witch's daughter#owl#moon#Victorian#fairy tale

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Howard Pyle - Illustration for the story "The Sword of Ahab" by James Edmund Dunning, published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine (August 1904)

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward Penfield - Poster advertising Harpers New Monthly Magazine March

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeopteryx, originally published in 'Beast, bird and fish, fourth paper. Birds of the air' by Burt G. Wiley, Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1870, 40 (237): 338-344.

https://archive.org/details/sim_harpers-magazine_1870-02_40_237/page/340/mode/2up

Reprinted mirrored in 'Footprints in the rocks' by Charles H. Hitchcock, The Popular Science Monthly, August 1873 p. 428-441.

https://archive.org/details/popularsciencemo03newy/page/434/mode/2up

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

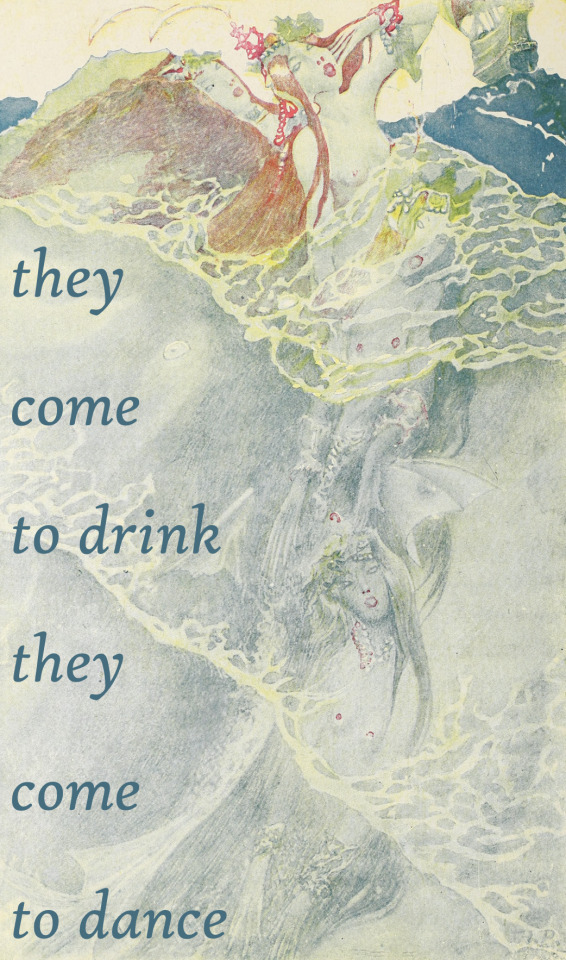

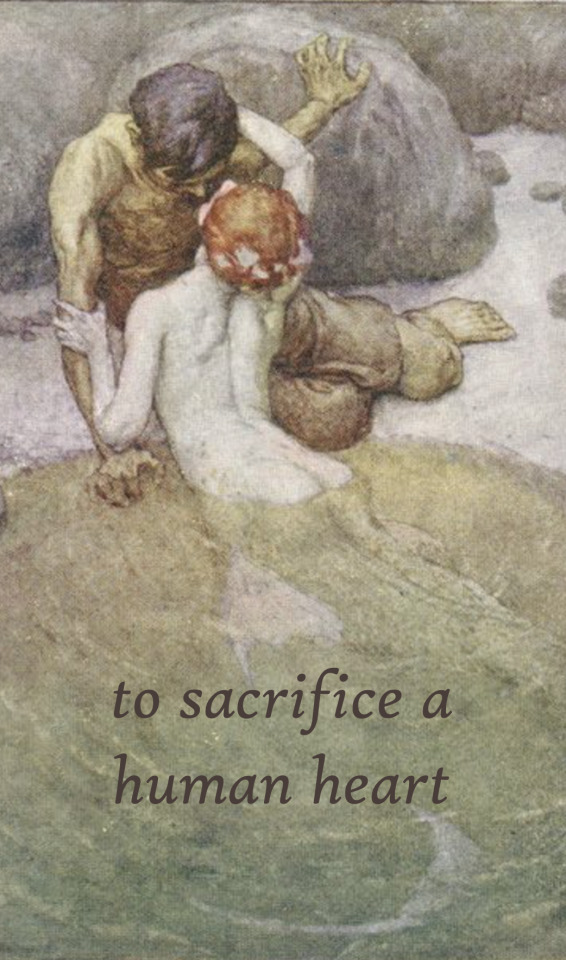

Illustration from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1901-1902 - unknown artist // Mermaid Illustration for Goethe's "Der Fischer" - Erich Schütz // Mermaids - Florence + the Machine

#mermaid#mermaids#mermaids song#mermaids florence + the machine#mermaids florence#dance fever#florence + the machine#florence and the machine#fatm#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art

166 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Władysław T. Benda. Two women seated facing each other. Harper's Bazaar, between 1890 and 1934.

Harper's Bazaar is an American monthly women's fashion magazine. It was first published in New York City on November 2, 1867, as the weekly Harper's Bazar.

#władysław t. benda#cosmetics#cosmetics ad#cosmetics advertisement#interiors#women#drawings#periodical illustrations#periodical illustration#harper's bazaar#interioirs

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

These Are Her Letters To The World

Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell have edited a new edition of Emily Dickinson’s letter. The New Yorker published an article about their book this week, here:

“A Letter always feels to me like immortality because it is the mind alone without corporeal friend,” wrote Dickinson to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in 1869 – and in her lifetime she wrote hundreds of letters.

However, following Dickinson’s death, her sister Lavinia destroyed much of Emily’s correspondences as per “Emily’s direction.”

In 1930, Mabel Loomis Todd, co-editor of the first posthumous edition of Dickinson’s poems, wrote this in an article about "Emily Dickinson’s Literary Debut" for Harper’s Monthly Magazine:

“Soon after her death her sister Lavinia came to me, as usual in late evening, actually trembling with excitement. She told me she had discovered a veritable treasure – quantities of Emily’s poems which she had had no instructions to destroy. She had already burned without examination hundreds of manuscripts, and letters to Emily, many of them from nationally known persons, thus, she believed, carrying out her sister’s partly expressed wishes, but without intelligent discrimination. Later she bitterly regretted such inordinate haste. But these poems, she told me, must be printed at once.”

In 1958, Thomas H. Johnson published an edition of Dickinson’s letters where, in his introduction, he stated that – due to the poet’s reclusiveness – Dickinson “did not live in history and held no view of it.”

Fast forward to the New Yorker’s article. Its writer Kamran Javadizadeh points out that “Writing letters could…be for Dickinson not only a withdrawal from the world but also a way of extending herself into many worlds, all at once.”

In addition, “The nearly seven decades of scholarship that have followed Johnson’s pronouncement of Dickinson’s reclusiveness—scholarship to which Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell, the new volume’s editors, have contributed and from which they adroitly draw—have revealed it to be a crude caricature, one that says as much about men’s fantasies about women (and about poetry readers’ fantasies about poets) as it does about the actual person who wrote those thousand-odd letters.”

One topic not covered in the article is Dickinson’s “Master Letters,” a set of three emotionally laden notes addressed to a figure whom Dickinson calls “Master,” but never names.

Are the Master letters included in the updated edition “The Letters of Emily Dickinson”?

Yes.

Here’s info from an appendix of the book:

“Dickinson referred to various people in letters and poems as ‘Master,’ including *Leonard Humphrey; *Thomas Wentworth Higginson (multiple times); and (once humorously) Austin. She also uses ‘Master’ to refer to God or Christ. Whether ED was writing a person, a fictitious character, or experimenting with language of desire and devotion in these drafts remains in debate.”

The letters are numbered 192 (on page 268), 282 (on page 324), and 299 (on page 332).

#poetry#Emily Dickinson#Thomas Wentworth Higginson#Cristanne Miller#Letters#Mabel Loomis Todd#Master Letters#New Yorker

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A drawing of the garden of the Pensionnat Heger as Charlotte Brontë knew it made on occasion of one of the first visits (in 1857) to the Pensionnat by an American who'd read both Villette and The Professor and, according to their account, recognised M. Heger as 'M. Paul' and Mme Heger as 'Mme Beck'. The full article can be found at the link below (the part concerning the Pensionnat is at the very end).

It's interesting to note how M. Heger seemed to have fully embraced Charlotte's portrayal of him and the notoriety that came with it.

From "Vagabondizing in Belgium", Harper's New Monthly Magazine (Vol.17, issue 99, August 1858) pp 323-336.

#im sorry but if their portrayals by Charlotte were 100% accurate I find it very hard to believe the plot of villette was completely untrue#it's certainly giving credit to other contemporaries who met heger saying that villette was truer than Gaskell's biography#charlotte bronte#charlotte brontë#constantin heger#villette

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Navigation

✧ Blondie | Artist, Writer, Reborn Fashion Girl, Sagittarius

Born and raised in Dallas, Texas, Blondie moved to NYC to attend the Fashion Institute of Technology, where she received a degree in Fashion Design and Fabric Styling (Styling & Digital Media) with minors in Art History and Psychology. She has worked for fashion magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar and Nylon and brands such as Lasette Lingerie. After taking a short-term hiatus in Colorado, where she studied Cognitive Psychology, Blondie has now returned to New York City, where she can be found in her apartment editing her upcoming podcast, Airhead!, or making collage journals.

________________________________

masterlist | about me | portfolio | tiktok | insta | pinterest | substack

I try to post a new blog every month (or every other month when I'm desperate for time) - but fret not because there will always be a monthly playlist.

My inbox is open, talk to me! (Just don't be weird!)

________________________________

Everything I write is original, I do not consent to having my writing published anywhere else.

disclaimer | privacy policy | contact

#blondie#spotify#blogger#blondie has thoughts#blog#blog post#journalism#my post#self discovery#Spotify#self healing#self love#new york#colorado#mental health#music#writing#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#writerscommunity#journal#journey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Howard Pyle, "The Duel between John Bulmer and Cazaio", from "In the Second April", Harper's New Monthly Magazine, April 1907

https://m.facebook.com/groups/487520944655933/permalink/9430318373709434/

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

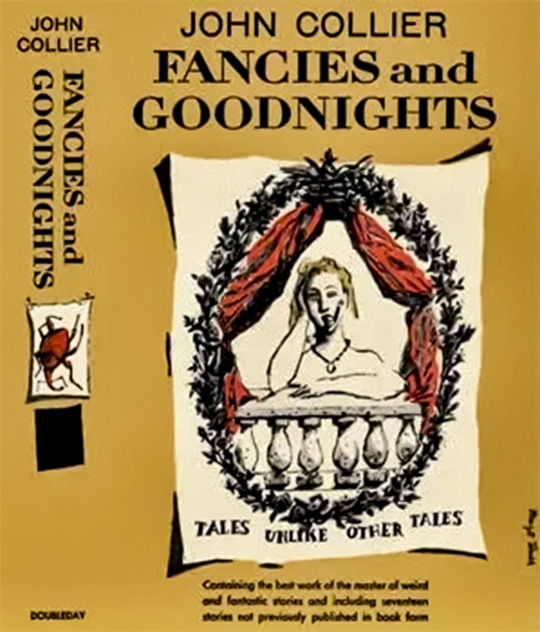

FANCIES AND GOODNIGHTS: Tales Unlike Other Tales by John Collier. (New York: Doubleday, 1951) Cover by Margot Tomes.

"Bottle Party" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1939)

"De Mortuis" (The New Yorker 1942)

"Evening Primrose" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"Witch's Money" (The New Yorker 1939)

"Are You Too Late or Was I Too Early?" (The New Yorker 1951)

"Fallen Star"

"The Touch of Nutmeg Makes It" (The New Yorker 1941)

"Three Bears Cottage"

"Pictures in the Fire"

"Wet Saturday" (The New Yorker 1938)

"Squirrels Have Bright Eyes" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"Halfway to Hell" from THE DEVIL AND ALL (1934)

"The Lady on the Grey" (The New Yorker 1951)

"Incident on a Lake" (The New Yorker 1941)

"Over Insurance" [… cont’d]

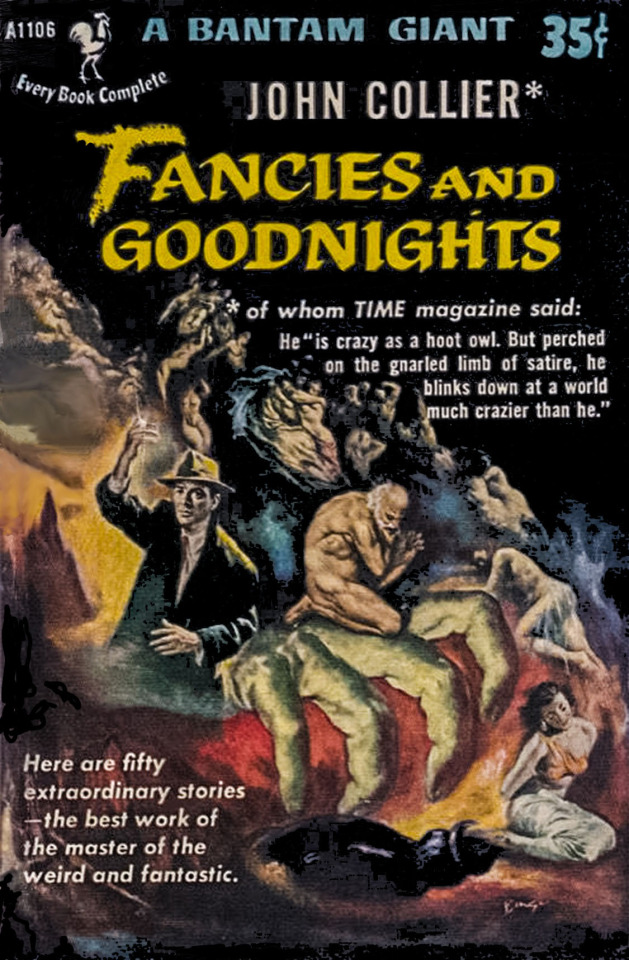

(New York: Bantam, 1953) Cover by Charles Binger. • (New York: Bantam, 1957) Cover uncredited.

"Old Acquaintance" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"The Frog Prince" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"Season of Mists"

"Great Possibilities"

"Without Benefit of Galsworthy" (The New Yorker 1939)

"The Devil, George, and Rosie" from THE DEVIL AND ALL (1934)

"Ah the University" (The New Yorker 1939)

"Back for Christmas" (The New Yorker 1939)

"Another American Tragedy" (The New Yorker 1940)

"Collaboration" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"Midnight Blue" (The New Yorker 1938)

"Gavin O'Leary" [chapbook, 1945]

"If Youth Knew, If Age Could" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"Thus I Refute Beelzy" (Atlantic Monthly 1940)

"Special Delivery" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"Rope Enough" (The New Yorker 1939)

"Little Memento" (The New Yorker 1938)

"Green Thoughts" (Harper's Magazine 1931)

"Romance Lingers Adventure Lives"

"Bird of Prey" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941) [… cont’d]

(New York: Time, 1965) Cover by Seymour Chywast.

"Variation on a Theme" [chapbook 1935]

"Night! Youth! Paris! and the Moon!" (The New Yorker 1938)

"The Steel Cat" from LILIPUT (1941)

"Sleeping Beauty" (Harper’s Bazaar (UK edition) 1938)

"Interpretation of a Dream" (The New Yorker 1951)

"Mary" (Harper’s Bazaar 1939)

"Hell Hath No Fury" from THE DEVIL AND ALL (1934)

"In the Cards"

"The Invisible Dove Dancer of Strathpheen Island" from PRESENTING MOONSHINE (1941)

"The Right Side" from THE DEVIL AND ALL (1934)

"Spring Fever"

"Youth from Vienna"

"Possession of Angela Bradshaw" from THE DEVIL AND ALL (1934)

"Cancel All I Said"

"The Chaser" (The New Yorker 1940)

source

#book blog#books#books books books#book cover#suspense#john collier#new yorker#seymour chwast#charles binger#margot tomes#bizarre

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“On February 22, 1876, Thaté Iyóhiwiŋ, a Yankton Dakota woman living on the Yankton Indiana Reservation in South Dakota, and her European American mate, Felker Simmons, brought their daughter, Zitkála-Šá, into the world. Simmons would abandon mother and child, yet Zitkála-Šá describes the first 8 years of her life on the reservation as happy and safe. All that changed in 1884 when missionaries came to “save” the children.

Even though White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute was a Quaker project, it still forced the children who attended to adapt to the Quaker way of doing things, including taking new names. Zitkála-Šá was renamed Gertrude Simmons. In her biographies, Zitkála-Šá describes deep conflict between her native identity and the dominant white culture, the sorrow of being separated from her mother, and her joy in learning to read, write, and play the violin.

Zitkála-Šá returned to the reservation in 1887, but after 3 years she decided she wanted to further her education and returned to the Institute again. She taught music while attending school from 1891 to 1895, when she earned her first diploma. Her speech at graduation tackled the issue of women’s inequality and was praised in local newspapers. She had a gift of public speaking and music, and put both to good use during her life.

In 1895 Zitkála-Šá earned a scholarship to attend Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. While in college she gave public speeches and even translated Native American legends into Latin and English for children. In 1887, mere weeks from graduation, her health took a turn for the worse; her scholarship did not cover all expenses, so she had to drop out.

After college Zitkála-Šá used her musical talents to make a living. From 1897-1899, she played violin with the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. She then took a job teaching music at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where she also hosted debates on the issue of Native American treatment. The school used her to recruit students and impress the world, but her speaking out against their rigid indoctrination of native children into white culture resulted in her dismissal in 1901.

Concerned about her mother’s health, Zitkála-Šá returned to the reservation. While there she began to collect the stories of her people and translate them into English. She found a publisher in Ginn and Company, and they put out her collection of these stories as Old Indian Legends in 1901. Like most authors, she took another job at the Bureau of Indian Affairs as her principal support. It was at this job in 1902 that she met and married Captain Raymond Bonnin, a mixed-race Nakota man.

The couple moved to work on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah for the next 14 years. They had one son, named Ohiya. Zitkála-Šá met and began to collaborate with William F. Hanson, a composer at Brigham Young University. Together they created The Sun Dance, the first opera co-written by a Native American. The opera used the backdrop of the Ute Sun Dance to explore Ute and Yankton Dakota cultures. It premiered in 1913 and was originally performed by Ute actors and singers. Choosing such a topic for the opera would have been a way to strike back at forced enculturation, because the ritual itself had been outlawed by the Federal Government in 1883 and remained so until 1933. Much later, in 1938, The Sun Dance came to The Broadway Theatre in New York City.

From 1902-1916, Zitkála-Šá published several articles about her life and native legends for English readers. Her works appeared in Atlantic Monthly and Harper’s Monthly, magazines with primarily a white readership. Her essays also appeared in American Indian Magazine. While these pieces were often autobiographical, they were still political and social commentary that showed her increased frustration with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which fired the couple in 1916.

In 1916, the couple moved to Washington D.C., where Zitkála-Šá served as the secretary of the Society of the American Indian. In 1926, she founded the National Council of American Indians, an organization that worked to improve the treatment and lives of Native Americans. By 1928, she was an advisor to the Meriam Commission, which would lead to several improvements in how the Federal Government treated native peoples.

Zitkála-Šá continued writing, and her books and essays became more political in such works as American Indian Stories (1921) and “Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians,” published in 1923 by the Indian Rights Association. She spoke out for Indian’s rights and women’s rights up until her death in 1938 at the age of 61"

📷: Gertrude Kasebier's photos of Zitkala-Ša, AKA Red Bird, from BUFFALO BILL'S WILD WEST WARRIORS. You can read about her in the book INDIGENOUS INTELLECTUALS by Kiara M. Vigil.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Burdett Frost - Sorcery, “Harper’s New Monthly Magazine”, 1892.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun Fact: Chapter 54 of Moby-Dick was not in the first original copies and was in fact published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine while Moby-Dick was being sent out for publishing.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Carpet Caper"

All they’ve been able to learn is that the expression can be traced to 19th-century America. But “Betsy” herself remains stubbornly anonymous. As the Oxford English Dictionary comments: “The origin of the exclamation Heavens to Betsy is unknown.”

The earliest published reference found so far, according to the OED, comes from an 1857 issue of Ballou’s Dollar Monthly Magazine: “ ‘Heavens to Betsy!’ he exclaims, clapping his hand to his throat, ‘I’ve cut my head off!’ ”

Fred Shapiro, editor of the Yale Dictionary of Quotations, found this hyphenated example in an an 1878 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine: “Heavens-to-Betsy! You don’t think I ever see a copper o’ her cash, do ye?”

And the OED has this one from a short-story collection by Rose Terry Cooke, Huckleberries Gathered From New England Hills (1892): “’Heavens to Betsey!’ gasped Josiah.” (“Betsy,” as you can see, is spelled there with a second “e.”)

On the identity of Betsy, speculation goes Betsy Ross, but another line of thought is it was just a common feminine name.

#Archie Comics#Jughead#Ethel Muggs#Expressions#Etymology#Heaven's to Betsy#In this narrative universe Jughead reads comic books about his best pal#1971

6 notes

·

View notes