#gunnar myrdal

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

Karl Gunnar Myrdal was a Swedish economist and sociologist.

Link: Gunnar Myrdal

0 notes

Photo

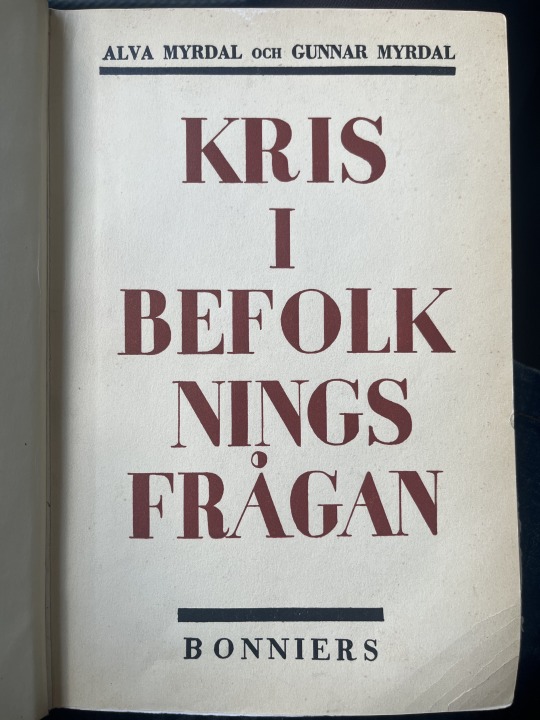

Debattbok av socialdemokratiska paret Alva och Gunnar Myrdal från 1934.

Boken behandlar de demografiska problem som följer på att barnafödandet i Sverige vid tiden minskade. Den sänkta befolkningskvaliteten behövde hanteras för att förbättra folkmaterialet.

Två samhällsproblem och osäkerhetsfaktorer som inverkade på befolkningens benägenhet att skaffa barn ansåg Myrdal var arbetslösheten (som vid tiden låg på 20 %) och bostadsbristen (som delas upp i dels trångboddhet och dels undermåliga bostäder). Individens medel för att uppnå förbättrad levnadsstandard var att tillgå den liberalekonomisk lösningen att skaffa färre barn. Myrdal förespråkar genomgripande fördelningspolitiska, socialpolitiska och produktionspolitiska reformer som det offentligas sätt att höja fruktsamheten (s 112).

En samhällsordning, som […] icke har råd att ge barnen tillräcklig och sund föda, fuktfria och rymliga bostäder, betryggande hälsovård och en god uppfostran, och som samtidigt saknar bruk för en stor del av sin arbetskraft, vilket får gå arbetslös – den samhällsordningen är orimlig, oförnuftig och omoralisk, och den är genom ett sådant medgivande redan dömd (s. 285).

Eftersom samhället drar nytta av att barnafödandet höjs till det optimala reproduktionsgränsen om 3 barn/familj bör samhället bära en del av den ekonomiska bördan för barn, bl.a. genom barnpenning i någon slags offentlig regi (?) och ersättning när kvinnan missar arbete efter födsel.

Arbetslösheten kan enl författarna delvis lösas genom ökat bostadsbyggande, vars materialbehov landet dessutom skulle kunna tillgodose själv i form av svenskt järn och trä. (Klassiska kritiken att arbetsimmigration leder till lönedumpning och försämrade arbetsvillkor (s 106).) En ökning av produktion-konsumtion bidrar också till minskad arbetslöshet (det finns överflöd av naturtillgångar att utnyttja). Socialpolitiken ska dessutom bidra till en bättre konsumtion; hushållen är ineffektiva och faller för reklamens påtryckningar (s 203). Mycken statistik framläggs för att bevisa att fattiga inte får både för lite och för näringsfattig mat; samtidigt exporteras överflöd av mat och säljs till underpris, istället för att komma den undernärda delen av befolkningen till del. Mha statistik utreds bostadsbristen ur både geografiskt perspektiv (stad-landsbygd) och klassperspektiv. Lägenheter för hela familjer är inte ovanligtvis så små som 50 kubikmeter (dålig luft, dessutom ofta delvis under mark = mögel). Bedrägligt uppfattas bostadssituationen förbättras, men detta beror enbart på aktiva beslut att inte skaffa fler barn som relativt sett blivit mer kostsamma.

Denna nya familj måste bland annat vara så uppbyggd, att den icke för sin ekonomiska välfärds skull och för hustruns frihet drives fram emot fullständigare barnlöshet. […]

För många av sina viktigaste funktioner skall familjen då bero av samhället, det större folkhushållet (s 319).

Större social och yrkesrörlighet för framtida generationer. Hittills har familjerna haft en “rätt” att hålla sig i undermåliga hem, missköta näringen och hindra barnen fr vad som beskrivs som rationella yrkesval. Om samhället ska ha något att säga till om “barnens frigörelse” måste samhället betala genom att ikläda sig merparten av både kostnaden och ansvaret (s 299). Familjelivet beskrivs som en “passiv traditionsform utan social egenrörelse”, en stel social form, medan det ekonomiska livers drivande kraft är tekniken (s 295).

Ett par gånger görs hänvisningar till Tyskland som varnande exempel, samtidigt som det görs referenser till rashygien och om möjligheten att hindra att asociala skaffar barn (oklart i vilken mån det anses ärftligt, författarna erkänner att många psykiska diagnoser påverkas av miljö). Utöver en snart minskande befolkning driver boken idén att den svenska befolkningskvalitén måste höjas, och som lösning presenteras social ingenjörskonst. Många av de förslag som förespråkas kan vi idag se realiserade: bostadsbidrag, allmänt bekostad förskola, grundskola (inkl fri skolmat) och universitet samt sjukvård (med fokus på förebyggande vård) m.m.. Åtgärder som idag grundas på konventionsåtaganden och MR-perspektiv - idéer om ett värdigt liv - motiveras häri snarare som effektiviseringsåtgärder; det är t.ex. resursslöseri att mödrar bara sköter sina egna barn, det kan finnas barnlösa som gör det mycket bättre och dessutom bör ha hand om minst 8 barn samtidigt. Utbildning på högre nivå ska vara öppen för de som är mest intresserade och kan dra mest nytta av det = som ger mest till samhället. Ökad konkurrens mellan studenterna är dessutom bra eftersom lärare som redan klagar på för studiearbetet olämpliga individer då kan hänvisa dessa annorstädes och höja “intelligent- och karaktärskraven” (s 283).

Ett återkommande, och för boken avslutande, budskap är att den äldre generationen redan är förlorad - det är genom propaganda riktad mot barnen som framtiden kan se ljus ut. T.ex. ska barnen lära sig om nutrition och således uppfostra föräldrarna om vad som behövs för att växa till starka och till samhället bidragande människor.

Förhoppningen står till de unga. Den redan uppvuxna generationen är oftast hopplös: den är och blir i stort sett som den redan är (s 325).

Barnen skola bygga upp det framtida samhället medan åldringarna enligt naturens ordning skola dö (s 236).

Skolans fokus är inte längre bara boklig kunskap, utan att uppfostra en ny värld; “individens sociala anpassning är skolans främsta mål”. Den dåvarande skolan kritiseras för att uppmuntra reaktiv intelligens, men inte aktiv (s 268). Myrdal förespråkar en vidgning “från individualpedagogik [individuell och frihetsuppfostran] till socialpedagogik” (s 264-265).Liberala individualistiska ideal har blomstrat som följd av industrialiseringen, i en övergångsperiod, men författarna förespråkar kollektivistiskt tänkande som bör inpräntas i skolan, bl.a. genom grupparbeten och klassammanhållning.

Myrdal beskriver det liberala idealet som ironiskt konservativt; "att kvinnans plats var i hemmet” var enbart relevant under den period som männen tog sig in i fabrikerna och kvinnorna pga barnafödande och -skötsel var bundna till hemmet. Innan dess var hemmet hela (produktions- och konsumtionsenheten) familjens plats. Att kvinnan skulle fortsätta förpassas till hemmet i den myrdalska visionen där uppfostrans- och utbildningsväsendet expanderar, är slöseri på produktionskraft. Men den konservativa liberalismens svar på halvfabrikat och att allt mer av hemarbetandet har flyttats till fabrikerna och staden blir den “kvinnliga uppfinningsförmågans instängda triumf”, som innefattar ett överlastat umgängesliv med middagsplanering, shopping och intensiv förströelseläsning eller virkning (s 312).

En intressant passage berör trångboddhetens psykologiska och själsliga konsekvenser, bla sk könsumgänget. Införandet av sk barnkammarskolor och gratis skolgång handlar inte bara om att mödrarna/föräldrarna ska ut i arbetslivet, utan också om att barnen ska få socialisera. I det post-industriella, moderniserade samhället rör sig inte familjen och bygemenskapen in och ut ur produktionsenheten hemmet (jmf “de växte upp i den arbets- och livsmiljö de för framtiden skulle tillhöra” s 292), eftersom det numera förminskats till enbart konsumtionsenhet i vilket hemmavarande leder till isolering. Mödrarna och barnen behöver komma ut för social och intellektuell stimulans. Att ta sig till jobb och skola/dyl är ett sätt att få andrum från den kvävande ostimulerande hemmiljön. Pga bostadsproblemet är idén om hemmet som en plats för uppfostran en borgerlig idé (s 234).

Själva detta faktum, att släkttillhörigheten måste spela en allt mindre roll nu än under gamla, mer stabila förhållanden, ställer på den moderna familjen det kravet, att den måste göra det psykologiskt lättare för barnen att lösa släkt. och familjeband. Detta är ett kanske paradoxalt krav i en tidsenlig uppfostran: vi måste frigöra barnen mera från oss själva. Det duger inte att låta dem fixeras alltför start till oss. Den faran är emellertid överhängande nu, äsrskilt då barnens antal blivit mindre och varje individ därför utsätter för en allmer intensiv föräldrapåverkan och tillgivenhet (s 301).

Mest uppseendeväckande är kanske stycket om sterilisering är, vilken ska grunda sig på frivillighet. Men, om upplysningar till den enskilde inte leder till att samtycke till sterilisering ges kan man behöva ändra lagarna så att tvångssterilisering är möjlig i sådana fall.

Matcentralisering inom fackföreningsrörelsen bygger på representativa demokratins principer = nedslå gruppegoistiska tendenser (s 280).

Tidigare idéutveckling

Malthusianism - det finns ingen gräns för förökning men tillväxten begränsas av en begränsad matproduktion och efterföljande svält som en anpassning efter mattillgång, fattigdom kan inte besegras genom ökad produktion. Lösningen är sena giftermål och sexuell avhållsamhet. Efter Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) = ��gammalliberal malthusianismens eländespessimis” (323)

Nymalthusianism - förespråkar förebyggande handlingar i form av preventivmedel och abort = “nyliberala nymalthusianismens ensidiga preventivmedelsoptimism”

2023-04-26

0 notes

Text

“During the 1960s, events sometimes happened so quickly that they almost seemed to outpace the speed of sound. In the fall of 1961 coeducational colleges still had what were called parietal rules regulating the few short periods of the week when men could be in women's dorms and vice versa. Boys wore ties and button-down shirts and spotted “whiffle” haircuts (so short that if you rubbed your hand over the bristles you could generate static electricity); girls wore skirts, starched blouses, knee socks, and ponytails. No one would think of calling a university president a derogatory name or breaking into official files.

By 1969, in contrast, rules had become synonymous with fascism. Male and female students lived with each other in the same dormitory room; a new sexual revolution had swept the country, accompanied by widespread experimentation with drugs. At the legendary rock festival at Woodstock in 1969, thousands of people gathered in open fields to hear their favorite musicians, celebrating not only a triumphant counterculture but brazenly flaunting conventional, middle-class behavior. Boys and girls wore jeans patched with fragments of the American flag, smoking marijuana was commonplace, and hair reached the lower backs of men and women alike. Policemen were routinely called “pigs” by some of the best and brightest college students, and one university president, whose office was occupied by demonstrators, received a manifesto telling him: “up against the wall, mother-fucker.” It was quite a decade.

…As early as the 1940s, when the Carnegie Foundation issued its clarion call, authored by the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, to end racial discrimination, sociologists and lawyers had commented that women were examples of an “American Dilemma.” Like black people, they were members of a society committed to liberty and personal freedom, yet treated as separate and different because of a shared physical characteristic. The contradiction was profound, striking at the heart of the integrity of the American Creed. Only when all citizens were freed from such categorical discrimination could the American dream be considered workable.

Pauli Murray, a black lawyer who had pioneered the effort to get blacks admitted to Southern law schools in the 1930s, zeroed in on the connection between race and sex in her work for the Kennedy Commission on the Status of Women. Like black civil rights activists, she declared, women should prosecute their case for freedom by going to court and demanding that they be given equal protection under the laws, a right conferred by the 14th Amendment when in 1867 it sought to ensure the legal standing of the newly freed slaves by defining their citizenship rights. At the time Congress had inserted the word “male” in front of “citizen,” temporarily caving in to those who still wanted to exclude women from fundamental rights, such as voting. But the 19th Amendment had altered that pattern when it recognized women’s right to vote, and now, Murray argued, women should insist on carrying their case forward on the basis of the civil rights they enjoyed with all citizens under the clause of the 14th Amendment that declared, “No State shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

…With the formation of the National Organization for Women in the fall of 1966, America’s women’s rights activists had an organization comparable to the NAACP, ready to fight through the media, the courts, and the Congress for the same rights for women that the NAACP sought for blacks. NOW focused on an “equal partnership of the sexes” in job opportunities, education, household responsibilities, and government. Betty Friedan and her allies pressured President Johnson to include women in his affirmative action policies, which were designed to hasten recruitment of minorities to decent jobs, and to appoint feminists to administrative and judicial officers. NOW endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment and made reform of abortion laws a national priority.

Equally important was the connection made by some young women between the treatment they received within the civil rights movement itself and the treatment blacks received from the larger society. Most of the young people in the early civil rights movement were black, but a significant minority were white, many of them women, including Sondra Cason (later Casey Hayden) from the Faith and Life community in Austin, Texas, and Mary King, daughter of a Protestant minister. Many of the younger activists joined the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which created an atmosphere in which independent thinking and social criticism could flourish.

….At a time when a new sexual revolution was just getting underway, the old rules and regulations about whom you slept with and after how long no longer seemed so clear. This was compounded by the realization that the biggest social taboo of all--interracial sex--was one of the most suspect and oppressive of all those rules and regulations. If the goal of the movement was a truly beloved community, why not extend that to sexual interaction? And how better to show that you meant what you said about integration than to sleep with someone of the other race? Especially in the heat of what seemed like combat conditions, reaching out for love, or even just release, appeared to be a logical and perhaps politically inspired thing to do.

In reality, however, too many women (and some men) became sexual objects. Having intercourse could become a rite of passage imposed against one’s will as well as a natural expression of bonding and affection. White and black women in particular became suspicious of each other, black women sometimes torn between anger at “their” men for falling victim to the stereotype of preferring white women as sexual partners, and anger at white women for seducing and taking away black men. The formula could be reversed, depending on which sex and which race you talked about. But the overall result was a new level of awareness that gender, as well as race, was an issue in this movement, and that until the question of treating women of equals became an explicit commitment of the movement, at least some of its ideals would always fall short of realization.

…The final ingredient for the rebirth of feminism took place within the rapidly expanding student movement in America. It would be historically inaccurate to speak of that movement as a unified crusade with a changing shape and definition. It took as many forms as there were issues, its ideological variants sufficient in number to fill a textbook. There were some who believed that a new culture, a “counterculture,” offered the only way to change America, and others who embraced political revolution, even if it had to include violence. Some wore overalls, T-shirts, and love beads and sought to transform the materialism of the middle class by creating a totally alternative life-style; others opted for factory jobs, short hair, and rimless glasses, committed to subverting the system from within.

Nevertheless, some generalizations are valid. Virtually all the participants in the student movement were white. Most came from middle or upper-class backgrounds. Children of privilege, they shared something in common with the critical and reflective posture of the Fetter Family, the group of Protestant students in Boston seeking reform of the church. But they had gone far beyond the moderate optimism of that group, and even the more pointed skepticism of the Students for a Democratic Society’s (SDS) 1962 Point Huron statement, with its desire to humanize capitalism and technocracy. By the mid-1960s, when the student movement started to grow with explosive force, more and more young people began to question the very basis for their society. The Vietnam War radicalized youthful protestors, male and female alike, seeming to symbolize--with its use of napalm to burn down forests and search and destroy missions to annihilate the enemy--the dehumanizing aspects of capitalism and Western-style democracy.

…At one SDS convention, and observer noted, “Women made peanut butter, waited on table, cleaned up, [and] got laid. That was their role.” Todd Gitlin, president of SDS in the mid-1960s, noted that the whole movement was characterized by “arrogance, elitism, competitiveness,... ruthlessness, guilt--replication of patterns of domination… [that] we have been taught since the cradle.” Women might staff inner-city welfare projects and immerse themselves, far more than men, in the life of the particular community being organized, but when it came to respect and recognition, they ceased being visible. Women occupied only 6 percent of SDS’s executive committee seats in 1964.

Nor was SDS alone in its attitudes. Throughout the entire anti-war movement, a similar condescension and disregard prevailed, symbolized by the antiwar slogan, “Girls say yes to guys [not boys] who say no.” Always happy to accept the part of the sexual revolution that allegedly made women more ready to share their affection, male radicals displayed no comparable willingness to share their own authority as part of a larger revolution. Women’s equality was not part of the new politics any more than it had been of the old.”

- William Chafe, “The Rebirth of Feminism.” in The Road to Equality: American Women Since 1962

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lasse Diding till angrepp mot Augustnominerad bok

Boken “De hemliga breven”, som samlar omfattande korrespondens mellan Jan Myrdal och hans föräldrar Alva och Gunnar Myrdal, är i höst nominerad till Augustpriset. Jan Myrdals son Janken Myrdal, hans faster Kaj Fölster och journalisten Bosse Lindquist står bakom publiceringen. Trion har även skrivit en inledning och ett efterord. I sin nyutgivna bok “De grova lögnerna om Jan Myrdal i De hemliga…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

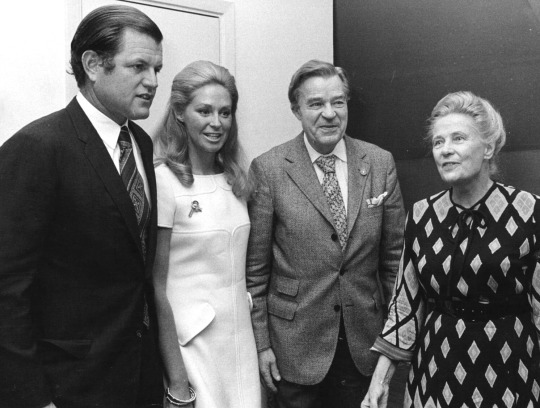

September 1971, The EMKs in Sweden. In the last pic they are shown with Professor Gunnar Myrdal and the Swedish former Minister of State Alva Myrdal.

#1970s#1971#joan kennedy#Joan Bennett Kennedy#Ted Kennedy#EMK#Edward M. Kennedy#Sweden#Gunnar Myrdal#Alva Myrdal#The Kennedys#kennedy

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

And when we consider the great ideological struggle raging since the Depression, between the Left and the Right, we see an even further problem for the author: a problem of style, which fades over into a problem of interpretation. It also points to the real motivation for the work: An American Dilemma is the blueprint for a more effective exploitation of the South’s natural, industrial and human resources. We use the term “exploitation” in both the positive and negative sense. In the positive sense it is the key to a more democratic and fruitful usage of the South’s natural and human resources; in the negative, it is the plan for a more efficient and subtle manipulation of black and white relations, especially in the South.

In interpreting the results of this five-year study, Myrdal found that it confirmed many of the social and economic assumptions of the Left, and throughout the book he has felt it necessary to carry on a running battle with Marxism. Especially irritating to him has been the concept of class struggle and the economic motivation of anti-Negro prejudice which to. an increasing number of Negro intellectuals correctly analyzes their situation:

As we look upon the problem of dynamic social causation, this approach is unrealistic and narrow. We do not, of course, deny that the conditions under which Negroes are allowed to earn a living are tremendously important for their welfare. But these conditions are closely interrelated to all other conditions of Negro life. When studying the variegated causes of discrimination in the labor market, it is, indeed, difficult to perceive what precisely is meant by “the economic factor….” In an interdependent system of dynamic causation there is no “primary cause” but everything is cause to everything else.

To which one might answer, “Only if you throw out the class struggle.” All this, of course, avoids the question of power and the question of who manipulates that power. Which to us seems more of a stylistic maneuver than a scientific judgment. For those concepts Myrdal substitutes what he terms a “cumulative principle” or “vicious circle.” And like Ezekiel’s wheels in the Negro spiritual, one of which ran “by faith” and the other “by the grace of God,” this vicious circle has no earthly prime mover. It “just turns.”

Ralph Ellison, An American Dilemma: A Review (1944)

#dang#ralph ellison#ellison#gunnar myrdal#american dilemma#diss#quote#class#racism#class struggle#power

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On understanding black culture through art, literature, and movement,

The artist documentation of the black struggle in America is captured in the widest varieties and mediums in the arts. The study of this struggle has been the highlight of my last eight weeks at Cornell - my crash course in American culture. I was initially introduced to it in my Writing Seminar and Art seminar through movements and writing. Via a study of the Civil Rights Movement, the seminal documentaries of the black experience through the antebellum stories of Charles Chesnutt, the course of the Harlem Renaissance and by extension the work of Nella Larsen, and most importantly, the Black Arts Movement (which had its roots in both movements above,) I saw the painting of a multilayered picture. Civil Rights Movement writer James Baldwin due to his intersectional identity and ideas regarding art also gave depth to my knowledge. In understanding the role of individualism in play, besides Larsen, the studies on the birth of intersectional identity through the Combahee River Collective and contemporaries such as Kimberle Crenshaw acknowledge the people's struggle these niches made for the foundations of female and queer blacks. Through all these layers and lenses, I realized many similarities of such a culture to my own. I noted the idea of the trained subconscious bias that the imposing race used to see through oppression even past granting autonomy is something I noted in culture beyond just the black, in the work of other colored cultures and artists of the same such as Chitra Ganesh and Nicholas Galanin. Objective readings finally allowed me to put a title to my understandings, especially on reading “An American Dilemma” by Gunnar Myrdal (Nobel Prize for economics), where he quotes the black struggle as "The Negro Problem" (chancefully, the title of a different book by Booker T. Washington.)

I mentioned movements and writing being the most apparent, but the most seminal to my understanding of this struggle was through the black artist. Distinct in style and nature, similar in artistic purpose, I have seen commonalities in both the battle and the views and perspective of these individuals over the last few weeks. I believe my study of the same was even more niche, not through the eyes of the black man, as was usually my case with literature, but through the eyes of the black women and their intersectional identity whose alienation birthed a mindset best captured in their art. My introduction to this struggle of the black female identity, as previously mentioned, was through the works of Harlem Renaissance novelist Nella Larsen and was solidified in my studies of the black female collectives such as the Combahee River collective and the nature of their identities acknowledged in the contemporary world by people such as Kimberle Crenshaw. I saw these values, personalities, and motivations reflected in a series of artists I studied this semester. Although dissimilar in origin, all these artists had an indifferent stance on the black struggle and highlighted the same through their art. Now, this struggle came to fruition through various sorts of approaches. There were works of personal struggle and struggles of black womanhood expressed in the works of Phoebe Boswell in pieces such as "The Space Between Things" and "For Every Real Word Spoken," respectively. The struggle also solidified in other forms, such as depictions of the black female body in media culture, which is seen in the works of Frida Orupabo. In her case, she attempts to return the gaze to question the superiority of the race that once dominated them. A similar such anti-colonial sentiment is one we studied in the case of Nicholas Galanin. In keeping with Nicholas Galanins' work through monuments and critique of the American landscape and experience, we see the works of Nicole Awai. Specific pieces such as "Reclaimed Waters" maintains the same debates on Christopher Columbus that are evoked by Galanin's works and in my posts over the last few weeks. The final form of approach is in exploring the black body and its fitment into society today, whose in-depth photographic studies we see in the works of Sasha Phyars-Burgees and her exploration of the black family unit and canonically black values in Chicago. She maintains a similar narrative as all the artists in terms of how the Black body, in the American context or otherwise (Orupabo being Norwegian), falls prey to the combined political institutions and capitalist agenda. Their work weaves a narrative based on the realities of contemporary black life and highlights the black struggle.

Week 9 Post #1 ART2103

#civil rights movement#harlem renaissance#charles chesnutt#nella larsen#combahee river collective#gunnar myrdal#phoebe boswell#kimberle crenshaw#nicholas galanin#chitra ganesh#nicole awai#frida orupabo#sasha phyars-burgees

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A TRUER “AMERICAN CREED”

[Note: From time to time, this blog issues a set of postings that summarize what the blog has been emphasizing in its previous postings. Of late, the blog has been looking at various obstacles civics educators face in teaching their subject. It’s time to post a series of such summary accounts. The advantage of such summaries is to introduce new readers to the blog and to provide a different context by which to review the blog’s various claims and arguments. This and upcoming summary postings will be preceded by this message.]

Recent postings have made a relationship between a sense of identity – how one places oneself in a given group such as a race or an ethnicity or a Yankee fandom – and the polarized politics the nation is experiencing. The journalist Ezra Klein[1] cites the work of various social scientists that make that connection. At the center of this association is race.

There is a long history of such work, but it probably began with the work of Gunnar Myrdal. His ground-breaking effort, An American Dilemma in 1944, while based on extensive data collected in the South, unfortunately seems to have left an inaccurate account of why blacks were being treated as they were in those states.

In a few words, that view attributed the maltreatment of African Americans to an inability by vast numbers of Americans to live up to the prevailing beliefs of an American Creed. That creed has upheld the traditional views liberty, justice, and equality. The take-away was that Americans were basically a moral people with a moral consciousness but that somehow, what existed was behavior that was contrary to what millions of Americans believed to be moral.

The solution therefore was for those Americans to just stop behaving as they had been doing. This oversimplified conclusion has been the subject of extensive criticism. Center to this criticism are questions about how Americans saw or see themselves. These critics agree that the problem is not how people, mostly Southerners, don’t live up to their values; but rather, it is based on people having counter values to the American Creed when it came to others.

That is, many – and not just Southerners, but Northerners and Westerners as well – just did not or do not hold beliefs extending these democratic rights and benefits to those who belong to other racial identities. In terms of federation theory, what this blogger promotes, Americans in general did ascribe to federated beliefs but only extending them to those who were/are white. They held on to what this writer calls parochial/traditional federalism.

Historically, any improvement in the treatment of nonwhite was not the product of redefining federalist ideals, but due to the strengthening of natural rights ideals. This blog has described how natural rights, in the years after World War II, became the dominant view of governance and politics. One good consequence of that shift has been the betterment of the treatment of African Americans, but as one can readily see, that improvement has fallen way short of the standards the American Creed established especially in the nation’s founding documents.

What still remains is an ample set of ideals and values that prevailed before the natural rights view took hold, i.e., discriminatory beliefs against nonwhites. Those anti or non-democratic views are deep-seated among too many Americans. The remnants of the segregated past still live in the hearts of whites who feel no dissonance in how they view or treat blacks and other nonwhites.

Instead, there exists a whole view of counter-norms that justify discriminatory practices that still uphold segregation in many aspects of social life, including living arrangements, employment practices, and social gatherings. Psychologically, people influenced by these counter-norms are able to compartmentalize or re-interpret the American Creed. Or it is what one might judge to be an extensive rationalization of what is taking place in terms of race relations.

This initial paragraph of an overview article gets at what takes place,

At root, racism is “an ideology of racial domination … in which the presumed biological or cultural superiority of one or more racial groups is used to justify or prescribe the inferior treatment or social position(s) of other racial groups. Through the process of racialization … perceived patterns of physical difference – such as skin color or eye shape – are used to differentiate groups of people, thereby constituting them as “races”; racialization becomes racism when it involves the hierarchical and socially consequently valuation of racial groups.[2]

These observations of what is taking place are supported by the work of various other social scientists such as Maurice Davie, Ernest Campbell, Hubert M. Blalock and it leads one to understand that the challenge of instituting a true American Creed – true in the fashion Myrdal defined the term – is significantly more difficult than what Myrdal judged the challenge to be.

Not living up to a standard is dwarfed by the fact that the standard was not held or not held to be moral as originally thought among too many Americans.

This blog does not see the solution as giving up on the American Creed or its supporting federalist beliefs, but on insisting that those beliefs need to be extended to include fellow citizens whose ancestry goes beyond European origins. That means, not only turning away from restricting inclusion to non-European based groups and individuals but to also reject radical individualism of the natural rights view with its narcissistic baggage.

Instead, Americans should extend what David Brooks calls “relationalism”[3] – or what this writer calls liberated federalism. As this blogger states in his book,

By calling upon civics educators to adopt another perspective, this book asks educators to accept an alternative view of governance and politics. This other view aligns with the nation’s history but provides an updated version to address its earlier shortcomings and to meet current realities. This other view can be called liberated federalism.[4]

This language, standing apart, does not communicate the difficulties associated with such a change. But given how extensive and undeniable the related problems have become, perhaps the nation is disposed to making the necessary changes it needs to make to approach Myrdal’s American Creed.

[1] Ezra Klein, Why We’re Polarized (New York, NY: Avid Reader Press, 2020).

[2] Matthew Clair and Jeffrey S. Denis, “Racism, Sociology of,” Elsevier Ltd., 857, accessed December 15, 2020, https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/deib-explorer/files/sociology_of_racism.pdf .

[3] David Brooks, The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life (New York, NY: Random House). This term relates to a related theory in sociological literature.

[4] Robert Gutierrez, Toward a Federated Nation: Implementation of National Standards (Tallahassee, FL: Gravitas/Civics Books, 2020), 16-17 – available through Amazon.

0 notes

Text

Primus non inter pares

When Nehru did not resign after losing the 1962 war with China, the writing was on the wall - categorically, unequivocally, unambiguously.

Some of us are more equal.

Some of us can get away with anything.

As prime minister, he was not primus inter pares.

He was primus.

A maharaja.

And like any maharaja, he created a dynasty.

The notion of the citizen - equally accountable, equally important, equally to be protected and preserved - had not arrived, and is never to arrive in South Asia.

One can hardly blame the British for failing to create ideas of citizenship - a foreign ruler is very unlikely to regard his subject an equal.

The failure was indigenous.

We borrowed post-Enlightenment ideas of nationalism, Marxism, socialism...but not of the citizen or the modern state: a state covering a defined territory where everyone - Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Naga, Dalit, League, BNP, Islamists - would be guaranteed security from molestation by others.

The ideology of difference precluded state-formation.

Long ago, in the 70s, Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal distinguished between the “soft state” and the “hard state” - under the latter he grouped the West European and North American states; under the former the South Asian states.

These soft states are characterized by “indiscipline” - and that’s putting it mildly, Mr Myrdal!

0 notes

Quote

En general, los hombres no quieren que se les enseñe a pensar bien; prefieren que se les diga qué han de creer.

Gunnar Myrdal

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The exhausting depravity of Floyd’s death—the indelible image of Chauvin’s knee pinched into Floyd’s neck as fellow officers looked on with indifference—served as a vivid illustration of a fact Black activists have long known: that police brutality is not only endemic in the United States, but in Minneapolis specifically. The Minneapolis City Council seemed to recognize this last summer, when city officials announced a commitment to substantive police reform—up to and including the possibility of replacing the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD). Such bold action was unthinkable prior to 2020.

In the weeks prior to Wright’s death, city legislators approved, or at least considered, a series of specific reforms of the MPD. In March, legislators put forward a ballot measure (to be voted on in November) to amend the Minneapolis city charter to deputize the city council with the authority to make significant changes to the city’s policing: once this has been approved, actions being considering include putting the MPD under the supervision of both the mayor and the city council (the MPD currently answers only to the mayor), in some way curtailing the growth of the Minneapolis police force, and even outright replacing the police department with an “office of public safety.” Piecemeal yet long overdue changes such as banning chokeholds and mandating that officers document when they unholster their firearm already preceded this effort to reform the police via charter amendment.

While these reforms appear ambitious, they are far from the coordinated effort to “defund” the MPD that they were initially billed as being. Indeed, in many senses they coopt the language of defunding, made popular by young activists, to attempt to sneak through the exact opposite: though they would reduce the growth of the police force, they would not in any obvious way address the militarization that has made the MPD into one of the most violent police forces in the country.

The violence of the MPD is, of course, part of a national story. As scholars such as Elizabeth Hinton, Stuart Schrader, and Naomi Murakawa have shown, modern, militarized U.S. policing arose collectively out of postwar liberalism: though its precise manifestation has varied regionally, all U.S. policing relies on a rationale of “security” as a pretext for regulating the behavior of poor people and communities of color that were the intended recipients of social reforms since the 1960s. Out of this has arisen everything from punitive “tough-on-crime” policies—historically popular across the political spectrum—to “preemptive” policing initiatives such as Broken Windows and Stop and Frisk.

Unfortunately, our collective notion of what would constitute ideal police reform has its roots in this same context of postwar liberalism, in which private responsibility and collective securitization remain the ultimate goods that are sought. Since World War II, liberals have emphasized regulating individual behavior to correct the inequalities that police often reinforce—the sanctity of Black communities contingent on the ability of the police to “restore peace.”

In the specific case of Minneapolis, for example, the failure to curtail police brutality—despite numerous waves of well-intentioned liberal reform efforts beginning as early as the 1920s—derives precisely from the limitations of those who sought transformative racial justice, not because of the efforts of reactionaries to undermine those reforms. At many points in the postwar history of Minneapolis, police reform efforts were led by the very progressives who had helped militarize the MPD in the first place.

This was in no small part a result of progressive ideological commitments about the origins of racist policing. Believing that racist policing was mainly caused by what we’d now call implicit bias, Minneapolis progressives sought to remake the psychology of white police officers, compelling cops to interrogate their biases—all while encouraging greater presences of police officers in Black communities and while downplaying systemic and overt racism. Minneapolis progressives thus approached police reform with the premise that policing could be made more effective, more precise—and that better, not less, policing was essential to racial justice and improved race relations.

This legacy still overshadows police reform in Minneapolis, and the recounting of this history that follows—of how so many good-faith efforts failed catastrophically—should leave us deeply skeptical about the enterprise of police reform in its entirety. If Minneapolis and the nation are to escape the shadow of failed decades of police reform, they must reckon with this history. And they likely need to jettison the rubric of police reform and seek out more promising ways of conceptualizing the path toward racial justice and a society free from violence.

At many points in the postwar history of Minneapolis, police reform efforts were led by the very progressives who had also helped militarize the MPD.

Historically, Minneapolis was a very white city: during the Civil War, its Black residents totaled fewer than 300. By 1940 the city’s population was still less than 1 percent Black, and most were segregated in Northeast Minneapolis, confined by racial covenants placed on real estate. The percentage of the city that was Black remained below 5 percent into the 1970s, at which time it began increasing dramatically during the same period that saw whites abandoning urban centers nationwide. The city is now nearly 20 percent Black.

Despite its relatively small number of Black residents, in the 1920s Minnesota became a Midwestern hub of the Ku Klux Klan. The 1920 lynching of three Black men in Duluth spurred the passage of a state anti-lynching law in 1921 (led by Black activist and women’s rights advocate Nellie Griswold Francis), but it also stoked recruitment efforts for the Klan. The state became home to fifty-one chapters of the KKK, with ten in Minneapolis alone. Klan parades enveloped streets in Minnesota on weekends and Labor Days. Minneapolis Klan chapters counted a number of police officers as members—a fact which certainly continued to be true even after police affiliation with the Klan was officially forbidden by 1923.

Despite this, the same era saw some of the first efforts to professionalize the MPD and address issues of racial bias within the force. In 1929 the MPD hosted its first training session for police, which sought to make police “the foremost experts on crime prevention in the community.” However, professionalization as the route to police reform obscured the racial contours of policing in the city. As Black residents sought to integrate the city’s neighborhoods, incidents of indiscriminate police violence made headlines in Black newspapers, including the assault of 2 Black men and one Black woman by two drunk off-duty police detectives in July 1937. The beatings launched an investigation by the Minneapolis NAACP and the demand for the officers “to be immediately dismissed from the force,” but at least one of the accused detectives, Arthur Uglem, remained an MPD detective years beyond the event.

In Minneapolis, as in many parts of the North and Midwest, World War II would bring greater employment to Blacks, with African American workers integrating industries—for example, the Minneapolis garment industry. The war also ignited progressives’ attention to racial inequality in U.S. cities. Near the war’s conclusion, Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal published his era-defining text, An American Dilemma (1944), which argued that racism was an aberration within democracy and a betrayed of U.S. ideals. For U.S. democracy to be actualized in global terms, racial inequality would have to be vanquished at home.

Midcentury’s attempts to reform the MPD emerged from this context. Lyndon B. Johnson’s future vice-president, Hubert Humphrey—then a young, relentlessly energetic left-liberal—would lead the charge to overhaul the department. Elected mayor in 1945, Humphrey was acutely aware of Minneapolis’s history of racism and actively pursued policies to rectify past injustices.

Humphrey also saw civil rights—and particularly police reform—could be a coalition-building issue for moderates against the state’s more radical left, which was calling for more dramatic forms of racial redress. The creation of a Minneapolis Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) to report issues of discrimination in employment; a “Mayor’s Council on Human Relations” to document public acts of prejudice against Black people; and other anti-racist measures sought to outflank the left by drawing voters to Humphrey’s coalition.

Humphrey’s ambition was tempered, however, by the limits of his office. Mayoral powers in Minneapolis were—and remain—restricted; power lies mainly with the city council. The mayor has no budgetary authority and has little say in governmental appointees. Still he did have important control over one appointee: the police chief. For Humphrey, “the quality of law enforcement is as good or bad as [the mayor] decides,” he would write in his memoir. Shortly after taking office, he appointed Ed Ryan, known for his hostility to MPD corruption, as chief of police.

As mayor of Minneapolis, Hubert Humphrey assumed that the solution to policing reform lay in more efficient bureaucracy, not less policing. Indeed, Humphrey enlarged the size of the MPD, in part to guarantee more complete coverage of Black neighborhoods.

Under Humphrey’s orders, Ryan sought to rid the department of racism. Ryan supervised a series of training seminars for MPD officers so that they could “be prepared for any disturbances resulting from racial prejudices.” Some of these seminars, held in 1946, were led by Joseph Kluchesky, a former Milwaukee police chief and pioneer in anti-bias training. Kluchesky encouraged officers to give anti-racism talks at elementary schools and in general recommended greater police liaising with Black community ambassadors—clergy and other members of the Black middle class—who together could work toward a vision of “impartial law enforcement.” The seminars thus put the partial onus for improved policing on African Americans themselves, and suggested that the solution must include Blacks being willing to welcome greater police surveillance in their communities. As historian Will Tchakirides has argued, Kluchesky’s seminars “emphasized fixing Black behavior ahead of addressing the economic underpinnings of racial inequality.”

Humphrey’s police reform efforts assumed that the solution lay in more efficient bureaucracy, not less policing. Indeed, Humphrey enlarged the size of the MPD force, in part to guarantee more complete coverage of Black neighborhoods. Convinced of his faith that racism could be educated out of the body politic, Humphrey’s attitudes reflected Myrdal’s view of racialized policing and racial “discrimination to be an anomaly, something practiced by a few bad people.” Humphrey’s approach to police reform thus encapsulated a project of racial uplift through a preponderance of police: mandating greater communication between police officers and the public, and ingratiating police officers into the community to rectify inner biases that manifested in police assaults.

Police reform also took on the broader aims of Cold War liberalism—an effort to ensure personal beliefs did not hamper the country’s teleological march toward its democratic providence. In a pamphlet distributed to all members of the MPD, Kluchesky argued that it was the “Nazi technique to pit race against race,” and it was the responsibility of all police officers to reject such methods and “to preserve for posterity the splendid heritage of democracy.” Police reform in Cold War Minneapolis thus entailed a mission of aligning policing with an idealized image of U.S. democracy.

The overt antiracism of the Humphrey administration—the mayor’s principled dedication to extirpate racial discrimination from the minds of Minnesotans, the passage of the Minneapolis FEPC, attempts to eliminate racial covenants in housing—left many with the impression of Minneapolis as an enlightened city.

Yet despite this hype, police brutality regularly resurfaced within the MPD. After the police beating of Black Minneapolis resident Raymond Wells by two MPD officers on May 19, 1963, Mayor Arthur Naftalin—a liberal progressive like his mentor, Humphrey—called for a larger role for the Mayor’s Council on Human Relations, where he hoped civic leaders could “broaden . . . our discussions” of race. But Naftalin rejected the idea that racism ran rampant in the MPD. While the beating of Wells was “unfortunate and deeply distressing,” it was “essentially an isolated incident,” he reasoned. The mayor had no intention of drastically shaking up the MPD’s structure.

In the aftermath of the 1967 uprising, Mayor Arthur Naftalin, a liberal progressive, said the idea that police brutality had anything to do with the riot was “preposterous” and said roving gangs of Black youths had exacerbated the riot.

Nonetheless, calls for change were overwhelming among Minneapolis activists, which led to the creation of the first Minneapolis Civilian Review Board soon after Wells’s beating. But the review board disbanded after only a few months over legal concerns, leaving Black residents once again without recourse if they wanted to file a complaint against police.

The 1967 Minneapolis riot tested Naftalin’s conclusion that racism did not pervade the MPD. Accusations of police brutality following a parade on Plymouth Avenue led to violence between Blacks and police on July 19, which brought more police into Northeast Minneapolis armed with shotguns. Violence then escalated to a three-day riot that led to looting, arson, and Naftalin calling up the National Guard to quell tensions. The head of the Minneapolis police union, Charles Stenvig, also wanted to deploy massive numbers of officers to the Northside, looking to take “a harder line against black militants” who he felt were responsible for the riots. But Stenvig was restrained by Naftalin, who discouraged the use of overwhelming police force. As police looked to suppress the riots, chants of “We want Black Power” echoed through the streets. The riot eventually faded out by July 23, leaving property damage but no deaths in its wake.

In the aftermath of the 1967 uprising, Naftalin said the idea that police brutality had anything to do with the riot was “preposterous” and said roving gangs of Black youths had exacerbated the riot. Naftalin would go on to create a Hennepin County grand jury (consisting of all whites) that found “no police brutality” during the riot. In fact, it recommended increasing the police force, putting more patrols into the streets to “re-establish the rapport between the people and the authorities.” The jury also blamed the Northside Black community center The Way for encouraging “hoodlums.” Even when proffering ideas on what city government could do to prevent future riots, white elites leaned into the stereotype that the economic disenfranchisement of Blacks had its roots in a culture of poverty and fractured, fatherless families.

Black residents took matters into their own hands following the grand jury’s report. In 1968, Black leaders from The Way formed Soul Force, which, along with the American Indian Movement (AIM), enlisted Black and Native men to patrol Northside streets to intervene between “potential law-breakers and law-enforcers.” The AIM/Soul Force (or “Soul Patrol”) collaboration had shattering success in preventing arrests—which coincided with expanded welfare and criminal justices services offered by The Way—before being disbanded in 1975, partly due to harassment from MPD officers.

Naftalin declined to run for mayor in 1969. He was replaced by Stenvig, leader of the police union during the 1967 riot, who ran on a George Wallace–style platform of “law and order.” Stenvig would be mayor 1969–1973 and then again 1976–1977. During his time in office, Stenvig demonized welfare recipients, castigated taxes and government spending, touted increased prison sentences for criminals, and solidified renewed and enduring ties between the MPD and the mayor’s office.

Stenvig also helped lay the groundwork for the militarization of the MPD we now see. By 1980 the MPD had overstaffed its police force beyond its own expectations and aggressively supported vice squads against LGBTQ residents, raiding bathhouses and arresting gay men en masse. Throughout MPD maintained its reputation for corruption.

Despite so many reform efforts over the decades, nothing ever really changed.

Don Fraser (another Humphrey mentee, known for reforming the Democratic Party and tackling human rights issues as a Minnesota congressman in the 1970s) hoped to, once again, change this reputation. Fraser assumed the mayoralty in 1980 and held the office for fourteen years. Like Humphrey and Naftalin, he aimed to reform the MPD by imposing external oversight of its conduct. He created a police review board in the early 1980s that was entrusted with the mission of fielding complaints of police brutality. But the review board had no enforcement power, and the police chief was under no obligation to heed its demands. Despite his rhetoric of reform, Fraser supervised the MPD’s “aggressive operation” of drug raids as part of the escalating War on Drugs. The MPD became increasingly dependent on SWAT teams and saw increased arrest rates. The force earned a reputation of being “damn brutal,” according to its own police chief. MPD leadership also made “fighting the crack-cocaine trade a priority,” leading to the deaths of many innocent victims, including an African American elderly couple mistaken for drug traders.

By the mid-1980s, with incidents of police brutality unabated and unaddressed, the Minneapolis Civil Rights Commission (MCRC) encouraged Congress to investigate the MPD. Though a congressional investigation never materialized, a reimagined Civilian Review Board would emerge in January 1990. But despite so many reform efforts over the decades, nothing ever really changed.

The serial failures of police reform efforts in Minneapolis are indicative of larger failures within contemporary liberalism, and of progressives to articulate a comprehensive vision of how cities could still be safe—indeed, safer—without militarized policing. In the case of Minneapolis, it is clear that decades of militarized policing have failed to generate prosperity for all. Minneapolis ranks last among metro areas in the country in Black homeownership and has one of the nation’s worst racial education gap between Blacks and whites. Minnesota as a whole is next to last among states for income inequality between whites and Blacks.

Minneapolis reformers can begin by rejecting the premise that policing as we know it can align with the principles of U.S. democracy—that policing can be perfected.

A liberal concept of police reform, however ambitious it might be conceived, cannot rectify these metrics of injustice. The city council’s current plans are disconnected from the racialized order that will be maintained even if an Office of Public Safety patrols Minneapolis’s streets.

Minneapolis reformers can begin by rejecting the premise that policing as we know it can align with the principles of U.S. democracy—that policing can be perfected. For decades it was thought that more interaction between Blacks and whites was the cure for police violence and that the greater “visibility” of police in Black communities would ease crime rates. This has proven false. Historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor uses the term “predatory inclusion” to describe postwar efforts to encourage Black homeownership. The concept also applies to the history of police reform in Minneapolis: the various movement to encourage Black cooperation with police have persistently allowed the MPD to deflect attention from its own criminality, and put the onus on Blacks to rectify systemic injustices that the police are inevitably tasked with enforcing.

Seventies-era experimental programs such as AIM/Soul Force offer a possible route to reimagining police in Minneapolis: community-based, they sought harm reduction and tension de-escalation, and prioritized disarming suspects with firearms. But community policing must take place alongside municipal and federal investments that echo Hubert Humphrey’s vision of a “Marshall Plan for the cities.” Only massive expenditures on comprehensive programs of employment, health care, housing, and infrastructure can succeed in depriving racialized policing of its rationale.

Today, we must emphatically reject the central conceit of police reform that acts of police brutality are aberrations, and that they can be addressed with more and better policing. Those interested in genuine change must refuse to accept reform as the way forward, and work to build a city that brings greater justice to the families of George Floyd and Daunte Wright, and to all of Minneapolis.

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The majority of Americans, who are comparatively well-off, have developed an ability to have enclaves of people living in the greatest misery almost without noticing them.

Gunnar Myrdal

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ISLAM MENGHAPUS RASISME

Buletin Kaffah, No. 145 (20 Syawal 1441 H - 12 Juni 2020 M)

Amerika Serikat memanas! Di tengah pandemi Covid-19 yang merepotkan Amerika, terjadi demonstrasi di lebih dari 75 kota di Amerika. Melibatkan puluhan ribu pengunjuk rasa. Bentrokan antara polisi dan pengunjuk rasa pun tak terelakkan. Polisi menembakkan gas air mata. Sebaliknya, pengunjuk rasa melemparkan batu sekaligus menggambar berbagai grafiti di mobil polisi.

Kerusuhan ini dipicu oleh kematian seorang pria berkulit hitam bernama George Floyd (46) pada 25 Mei 2020 di Minneapolis, Minnesota. Beredar video yang menunjukkan George Floyd ditekan keras dengan lutut oleh seorang polisi berkulit putih. Bahkan saat George Floyd mengeluh dan memohon bahwa dirinya tidak bisa bernafas, polisi tetap terus menekan leher George Floyd.

Kejadian itu mengingatkan memori kasus Eric Garner. Dia juga meninggal di tangan polisi di New York pada Juli 2014. Kematiannya memicu demonstrasi besar. Mereka menentang kebrutalan polisi dan menjadi kekuatan pendorong gerakan “Black Lives Matter (Nyawa Orang Kulit Hitam itu Berarti)”.

Situasi di atas semakin memanas. Pasalnya, Presiden AS Donald Trump mengancam akan mengerahkan militer Amerika untuk melawan warganya sendiri yang terus berunjuk rasa. Dia mengatakan, "Ketika penjarahan dimulai, penembakan dimulai."

Mengapa di Amerika Serikat yang terkenal sebagai negara kampiun demokrasi terjadi konflik rasial yang berulang? Bagaimana solusi Islam mengatasi diksriminasi rasial (rasisme)?

Demokrasi dan Diskriminasi

Dalam bukunya berjudul An American Dilemma, Gunnar Myrdal menyinggung bahwa diskriminasi rasial dan kesenjangan ekonomi telah menjadi cacat bawaan demokrasi Amerika. Diskriminasi rasial tak bisa dilepaskan dari mulai masuknya orang-orang Eropa ke benua Amerika dan berdirinya negara Amerika Serikat. Mereka berkulit putih. Mereka mengklaim sebagai ras superior. Mereka lalu melakukan berbagai aksi kekejaman terhadap penduduk asli Amerika.

Berdirinya Negara Amerika telah meningkatkan diskriminasi rasial secara legal. Amerika memperluas perbudakan atas ribuan orang kulit hitam Afrika. Mereka didatangkan ke Amerika untuk dipekerjakan secara paksa pada ladang dan tambang baru.

Memang perbudakan berakhir dengan Amandemen Ketigabelas Konstitusi AS pada tahun 1865. Namun, rasisme tidak hilang dari masyarakat Amerika. Lalu dibuatlah Undang-Undang Hak Sipil tahun 1964. Itu pun karena desakan gerakan perjuangan warga kulit hitam Amerika yang menuntut hak-hak sipil mereka. Namun, secara praktis diskriminasi terhadap warga kulit hitam di tengah masyarakat Amerika terus berlangsung. Bahkan tokoh gerakan kulit hitam, yaitu Malcolm X dan Dr Martin Luther King, menjadi korban pembunuhan.

Warga kulit hitam sering dicap sebagai pelaku kejahatan dan mengalami perlakuan sadis oleh polisi. Menurut sebuah laporan yang dirilis oleh situs Pundit Fact AS pada 26 Agustus 2014 oleh Katie Sanders, rata-rata 36 jam pada 2012 dan 28 jam di tahun 2013, warga kulit hitam terbunuh oleh polisi Amerika.

Banyak orang kulit hitam terus hidup dalam kemiskinan dan marjinalisasi. Menurut Laporan Deutsche Welle, dari tahun 1974 hingga 2018, pendapatan rata-rata orang kulit hitam pada tahun-tahun tersebut masih termasuk yang terendah di Amerika. Menurut laporan yang sama, pendapatan rata-rata orang Amerika adalah sekitar $ 26.000 pertahun, sedangkan rata-rata orang kulit hitam (Afro-Amerika) hanya berpenghasilan sekitar $ 17.000 pertahun. Kondisi politik, ekonomi dan pengadilan yang tidak adil di AS selama beberapa dekade terakhir telah menyebabkan sedikitnya lima puluh persen anak-anak kulit hitam hidup dalam kemiskinan.

Menurut statistik resmi, tingkat pengangguran di antara orang kulit hitam jauh lebih tinggi daripada orang kulit putih. Pendapatan yang diperoleh orang kulit hitam jauh lebih rendah. Bahkan dalam beberapa kasus separuh dari kulit putih.

Dari berbagai keterangan di atas tampak jelas bahwa deskriminasi rasial dan kesenjangan ekonomi berjalan secara sistemik. Telah berlangsung berabad-abad dan menghasilkan persoalan yang tak berkesudahan.

Demokrasi di Amerika yang menghasilkan kebebasan dalam memiliki akhirnya melahirkan sistem kapitalisme. Kapitalisme telah melahirkan ketimpangan ekonomi dan sosial yang menimpa banyak warga kulit hitam. Akhirnya, sampai kapan pun konflik rasial di Amerika tak akan pernah hilang. Saat ini pemicunya adalah kematian George Floyd dan viralnya perlakuan sadis polisi. Pada masa depan, kasus-kasus serupa lainnya juga dapat kembali memicu ledakan konflik rasial yang bisa lebih parah. Seperti api dalam sekam. Dapat terbakar kapan saja. Inilah alasan kuat bahwa demokrasi sering menumbuhsuburkan diskriminasi, termasuk diskriminasi rasial (rasisme).

Islam Menghapus Diskrirminasi Rasial

Islam adalah agama yang mulia. Islam memposisikan keberagaman bahasa dan warna kulit sebagai fitrah alami manusia. Keragaman sekaligus membuktikan kekuasaan Allah SWT:

وَمِنْ آيَاتِهِ خَلْقُ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ وَاخْتِلَافُ أَلْسِنَتِكُمْ وَأَلْوَانِكُمْ ۚ إِنَّ فِي ذَٰلِكَ لَآيَاتٍ لِّلْعَالِمِينَ

Di antara tanda-tanda kekuasaan-Nya ialah Dia menciptakan langit dan bumi serta ragam bahasa dan warna kulit kalian. Sungguh pada yang demikan benar-benar terdapat tanda-tanda bagi orang-orang yang mengetahui (TQS ar-Rum [30]: 22).

Menurut Imam as-Suyuthi, segala ciptaan-Nya ini sebagai petunjuk bagi orang yang mempunyai akal dan ilmu. Islam juga memandang keberagaman suku-bangsa sebagai sarana untuk saling mengenal:

يَا أَيُّهَا النَّاسُ إِنَّا خَلَقْنَاكُمْ مِنْ ذَكَرٍ وَأُنْثَى وَجَعَلْنَاكُمْ شُعُوبًا وَقَبَائِلَ لِتَعَارَفُوا إِنَّ أَكْرَمَكُمْ عِنْدَ اللَّهِ أَتْقَاكُمْ إِنَّ اللَّهَ عَلِيمٌ خَبِيرٌ

Hai manusia! Sungguh Kami telah menciptakan kalian dari laki-laki dan perempuan. Kemudian Kami menjadikan kalian berbangsa-bangsa dan bersuku-suku agar kalian saling mengenal. Sungguh yang paling mulia di antara kalian adalah yang paling bertakwa. Sungguh, Allah Mahatahu lagi Mahateliti (TQS al-Hujurat [49]: 13).

Rasulullah saw. dalam berbagai sabdanya mempertegas bahwa kemuliaan seseorang bukan ditentukan oleh warna kulit maupun suku bangsa, tetapi ditentukan oleh ketakwaannya kepada Allah SWT. Pesan Rasulullah saw. saat Haji Wada’ menarik untuk diperhatikan. Beliau menyampaikan pesannya saat tiba di Namirah. Sebuah desa sebelah timur Arafah. Di depan ribuan jamaah haji beliau antara lain bersabda, “Sungguh ayahmu satu. Semua kalian berasal dari Adam. Adam diciptakan dari tanah. Tiada kelebihan orang Arab atas non-Arab. Tiada kelebihan non-Arab atas orang Arab kecuali karena ketakwaan. Tiada pula kelebihan orang putih atas orang hitam. Tiada kelebihan orang hitam atas orang putih kecuali karena ketakwaan.”

Bahkan Rasulullah saw. pernah sangat marah kepada Sahabat Abu Dzar al-Ghifari ra. saat berselisih dengan Sahabat Bilal ra. Pasalnya, Abu Dzar ra. memanggil Bilal ra. dengan sebutan, “Ya Ibna as-Sawda’ (Hai anak seorang perempuan hitam).”

Rasulullah saw. dengan tegas mengatakan kepada Abu Dzar ra., “Abu Dzar, kamu telah menghina dia dengan merendahkan ibunya. Di dalam dirimu terdapat sifat jahiliah!” (Lihat: Al-Baihaqi, Syu’ab al-Iman, 7/130). Teguran keras Rasulullah saw. ini merupakan pukulan berat bagi Abu Dzar ra. Abu Dzar ra. sampai meminta Bilal ra. untuk menginjak kepalanya sebagai penebus kesalahannya dan sifat jahiliahnya.

Dalam riwayat lain Nabi saw. pernah bersabda kepada Abu Dzar ra.:

ﺍﻧْﻈُﺮْ ﻓَﺈِﻧَّﻚَ ﻟَﻴْﺲَ ﺑِﺨَﻴْﺮٍ ﻣِﻦْ ﺃَﺣْﻤَﺮَ ﻭَﻻَ ﺃَﺳْﻮَﺩَ ﺇِﻻَّ ﺃَﻥْ ﺗَﻔْﻀُﻠَﻪُ ﺑِﺘَﻘْﻮَﻯ

Lihatlah, engkau tidaklah akan lebih baik dari orang yang berkulit merah atau berkulit hitam sampai engkau mengungguli mereka dengan takwa (HR Ahmad).

Dalam perjalanan sejarah, Islam, saat diterapkan dalam sistem Khilafah, terbukti berhasil menyatukan manusia dari berbagai ras, warna kulit dan suku-bangsa hampir 2/3 dunia selama lebih dari sepuluh abad. Hal ini tak mampu dilakukan oleh ideologi lain.

Wilayah-wilayah yang dibebaskan oleh Khilafah Islam diperlakukan secara adil. Mereka tidak dieksploitasi seperti yang dilakukan oleh negara-negara imperialis pengemban peradaban demokrasi-kapitalisme. Dakwah Islam oleh Khilafah dilakukan tanpa memaksa non-Muslim untuk memeluk Islam. Islam hadir untuk memberikan rahmat untuk alam semesta, bukan hanya manusia. Islam mampu menyatukan umat manusia dari berbagai ras, warna kulit, suku bangsa maupun latar belakang agama menjadi sebuah masyarakat yang khas. Semua itu terwujud dalam suatu naungan sistem Khilafah Islam.

Hal ini sangat jelas diakui oleh sejarahwan Barat Will Durant dalam bukunya berjudul The Story of Civilization: “Islam telah menguasai hati ratusan bangsa di negeri-negeri yang terbentang mulai dari Cina, Indonesia, India hingga Persia, Syam, Jazirah Arab, Mesir bahkan hingga Maroko dan Spanyol… Islam telah mewujudkan kejayaan dan kemuliaan bagi mereka sehingga jumlah orang yang memeluk dan berpegang teguh pada Islam pada saat ini (1926) sekitar 350 juta jiwa. Islam telah menyatukan mereka dan melunakkan hati mereka walaupun ada perbedaan pendapat maupun latar belakang politik di antara mereka.”

WalLahu a’lam bi ash-shawab. []

—*—

Hikmah:

Rasulullah saw. bersabda:

إِنَّ اللهَ لَا يَنْظُرُ إِلَى أَجْسَادِكُمْ وَلَا إِلَى صُوَرِكُمْ وَ لَكِنْ يَنْظُرُ إِلَى قُلُوبِكُم

Sungguh Allah tidak melihat fisik dan rupa kalian, melainkan Dia melihat kalbu-kalbu kalian.(HR Muslim). []

—*—

Download File PDF: http://bit.ly/kaffah145

1 note

·

View note

Photo

La chispa de Minneapolis. Por Atilio A. Borón En 1944 Gunnar Myrdal, un sueco que había recibido el Premio Nobel de economía, escribió un libro titulado “El dilema norteamericano” para desentrañar las raíces del llamado “problema negro” en Estados Unidos.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Determinists have often invoked the traditional prestige of science as objective knowledge, free from social and political taint. They portray themselves as purveyors of harsh truth and their opponents as sentimentalists, ideologues, and wishful thinkers. Louis Agassiz (1850, p. 111), defending his assignment of blacks to a separate species, wrote: "Naturalists have a right to consider the questions growing out of men's physical relations as merely scientific questions, and to investigate them without reference to either politics or religion." Carl C. Brigham (1923), arguing for the exclusion of southern and eastern European immigrants who had scored poorly on supposed tests of innate intelligence stated: " The steps that should be taken to preserve or increase our present intellectual capacity must of course be dictated by science and not by political expediency." And Cyril Burt, invoking faked data compiled by the nonexistent Ms. Conway, complained that doubts about the genetic foundation of IQ "appear to be based rather on the social ideals or the subjective preferences of the critics than on any first-hand examination of the evidence supporting the opposite view" (in Conway, 1959, p. 15).

Since biological determinism possesses such evident utility for groups in power, one might be excused for suspecting that it also arises in a political context, despite the denials quoted above. After all, if the status quo is an extension of nature, then any major change, if possible at all, must inflict an enormous cost—psychological for individuals, or economic for society—in forcing people into unnatural arrangements. In his epochal book, An American Dilemma (1944), Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal discussed the thrust of biological and medical arguments about human nature: "They have been associated in America, as in the rest of the world, with conservative and even reactionary ideologies. Under their long hegemony, there has been a tendency to assume biological causation without question, and to accept social explanations only under the duress of a siege of irresistible evidence. In political questions, this tendency favored a do-nothing policy." Or, as Condorcet said more succinctly a long time ago: they "make nature herself an accomplice in the crime of political inequality."

[...] I do not intend to contrast evil determinists who stray from the path of scientific objectivity with enlightened antideterminists who approach data with an open mind and therefore see truth. Rather, I criticize the myth that science itself is an objective enterprise, done properly only when scientists can shuck the constraints of their culture and view the world as it really is. [...] My message is not that biological determinists were bad scientists or even that they were always wrong. Rather, I believe that science must be understood as a social phenomenon, a gutsy, human enterprise, not the work of robots programed to collect pure information. I also present this view as an upbeat for science, not as a gloomy epitaph for a noble hope sacrificed on the altar of human limitations.

Science, since people must do it, is a socially embedded activity. It progresses by hunch, vision, and intuition. Much of its change through time does not record a closer approach to absolute truth, but the alteration of cultural contexts that influence it so strongly. Facts are not pure and unsullied bits of information; culture also influences what we see and how we see it. Theories, moreover, are not inexorable inductions from facts. The most creative theories are often imaginative visions imposed upon facts; the source of imagination is also strongly cultural.

--Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (1981 repr. 1996), pp. 52-4.

Aggasiz, L. 1850. The diversity of origin of the human races. Christian Examiner 49: 110-145.

Brigham, C. C. 1923. A study of American intelligence. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 210pp.

Conway, J. (a presumed alias of Cyril Burt). 1959. Class differences in general intelligence: II. British Journal of Statistical Psychology 12: 5-14.

Myrdal, G. 1944. An American dilemma: the Negro problem and modern democracy. New York: Harper and Brothers, 2 vols., 1483pp.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Economics MCQs (English) 301 to 305 (Important General Knowledge)

Economics MCQs (English) 301 to 305 (Important General Knowledge)

[HDquiz quiz = “450”]

View On WordPress

#A Contribution to the Theory of Trade Cycle#David Ricardo#Gunnar Myrdal#J.K. Galbraith#J.M. Keynes#J.R. Hicks#law of comparative costs#Liquidity Preference Theory of Interest#marginal propensity to consume#marginal propensity to save#The Affluent Society

0 notes