#glossa ordinaria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

The Glossa Ordinaria, which is Latin for "Ordinary [i.e. in a standard form] Gloss", is a collection of biblical commentaries in the form of glosses. The glosses are drawn mostly from the Church Fathers, but the text was arranged by scholars during the twelfth century. The Gloss is called "ordinary" to distinguish it from other gloss commentaries. In origin, it is not a single coherent work, but a collection of independent commentaries which were revised over time. The Glossa ordinaria was a standard reference work into the Early Modern period, although it was supplemented by the Postills attributed to Hugh of St Cher and the commentaries of Nicholas of Lyra.

Leviticus with the ordinary gloss : manuscript, [ca. 1150-ca. 1175]

MS Typ 204

Houghton Library, Harvard University

#history#christianity#catholicism#hugh of saint-cher#nicholas of lyra#bible#biblical gloss#glossa ordinaria

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snailfight. ‘The Smithfield Decretals’ (Decretals of Gregory IX with glossa ordinaria), Toulouse ca. 1300, illuminations added in London ca. 1340. British Library, Royal 10 E IV, fol. 107r.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

love going through manuscripts and finding all the little guys

all from: Decretalium compilatio cum glossa ordinaria Bernardi Parmensis de Botone, early 14th c, Ms. Barth. 11, University Library of Frankfurt

bonus:

#ok tbh i am just looking though digitised manuscripts to find little beasts and stunning decoration#that's all i'm here for#medieval art#manuscript art#illuminated manuscript#yeah ok fair there isn't much gold#but still

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

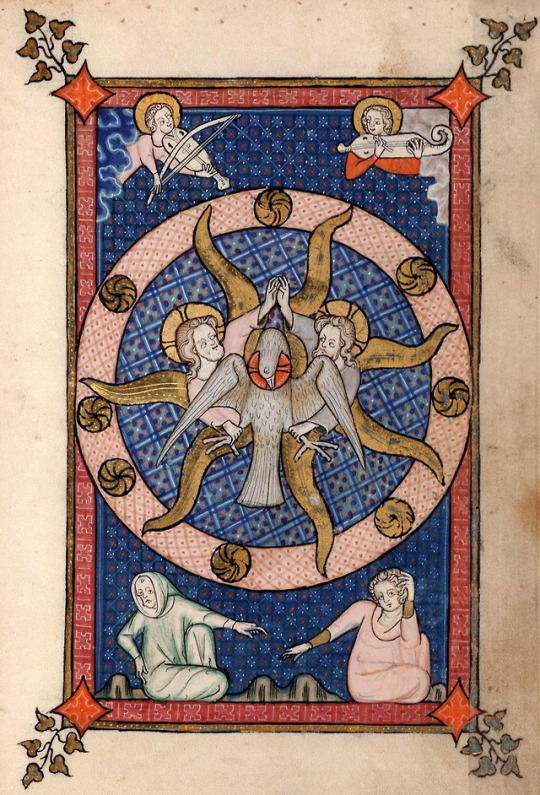

''Rothschild Canticles'', turn of the 14th century ”An intensely illustrated florilegium of meditations and prayers drawing from Song of Songs and Augustine��s De Trinitate, among other texts, the Rothschild Canticles is remarkable for its full-page miniatures, historiated initials, and drawings, which show the work of multiple artists.” Source

#rothschild canticles#illuminated manuscripts#painting miniatures#glossa ordinaria#medieval manuscripts#christianity#religious art#vintage art#song of songs#de trinitate#augustine

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Absolutely Not Yoda™ ‘The Smithfield Decretals’ (Decretals of Gregory IX with glossa ordinaria), Toulouse ca. 1300, illuminations added in London ca. 1340 British Library, Royal 10 E IV, fol. 30v @discardingimages

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

O Euchari (Hildegard von Bingen) sung by Azam Ali

First, a note on the singer who I’ve followed for decades:

Azam Ali (Persian: اعظم علی) is a well-known Iranian singer and musician. Ali has released ten albums with the bands VAS and Niyaz and friends, as well as multiple solo albums. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azam_Ali

In this video from summer 2020, she sings a famous song composed by Hildegard von Bingen. Information on the song below, including English translation of the lyrics.

youtube

+++

Azam Ali wrote about this song:

Composed by 12th Century Christian mystic, writer, composer, philosopher, Hildegard Von Bingen, a visionary who left behind a treasure trove of illuminated manuscripts, treatises on theology, medicine, botany, the arts, & above all her extraordinary music.

It is her music & this very song in fact which I heard at the age of 18, that made me want to sing. I was originally going to record this for my 2002 album "Portals of Grace" but settled on another composition of hers.

Hildegard for me is a feminist icon whose contributions to the canon of universal spirituality & mysticism, are immeasurable. Her work transcends centuries & musical, religious/mystical genres. It awakened me to the ancient philosophy of "The Music of the Spheres.” That if the human body is made entirely of elements forged by stars, then indeed we are celestial bodies & the cosmos is within us. If the rotation of heavenly spheres produce tones & harmony, then they must resonate within us. Thus, music in its most sublime form, is our participation in the harmony of the universe. That we may bring some harmony to our souls in our longing to return to our celestial home.

+++

For the Latin lyrics, go to https://lyricstranslate.com/en/o-euchari-leta-o-st-eucharius.html which is also the source for this English translation:

1a. O St. Eucharius, you walked upon the blessed way when with the Son of God you stayed— you touched the man and saw with your own eyes his miracles.

1b. You loved him perfectly while your companions trembled, frightened by their mere humanity, unable as they were to gaze entirely upon the good.

2a. But you embraced him in the ardent love of fullest charity— you gathered to yourself the bundles of his sweet commands.

2b. O St. Eucharius, so deeply blessed you were when God’s Word drenched you in the fire of the dove illumined like the dawn you laid and built upon the Church’s one foundation.

3a. And in your breast burst forth the light of day— the gleam in which three tents upon a marble pillar stand within the City of our God.

3b. For through your mouth the Church can savor the wine both old and new— the cup of sanctity.

4a. Yet in your teaching, too, the Church embraced her rationality— her voice cried out above the peaks to call the hills and woods to be laid low, to suck upon her breasts.

4b. Now in your crystal voice pray to the Son of God for this community, lest it should fail in serving God, but rather as a living sacrifice might burn before the altar of our God.

+++

Some of the meaning:

O Euchari, like Columba aspexit, was almost certainly written for the clergy at Trier. Saint Eucharius was a third-century missionary who became the bishop of the city. Stanza one evokes his years as an itinerant preacher (during which he performed miracles). The ‘fellow-travellers’ of stanza two are presumably Valerius and Maternus, his companions in the missionary work. The ‘three shrines’ of stanza five (compare Matthew 17: 4) represent the Trinity and perhaps, if we follow the Glossa Ordinaria, the triple piety of words, thoughts and deeds. The ‘old and the new wine’ of stanza six represent the Testaments: Ecclesia savours both, but the Synagogue, like the ‘old bottles’ of Christ’s parable, cannot sustain the New. Hildegard closes the Sequence with a prayer that the people of Trier may never revert to the paganism in which Eucharius found them, but may always re-enact the redemptive sacrifice of Christ in the form of the Mass.

from notes by Christopher Page © 1982 https://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/dw.asp?dc=W2933_GBAJY8403905

+++

+++

The first version of this song that I heard was on the highly innovative album of Hildegard’s songs arranged with “worldbeat music” by Richard Souther, now an acquaintance. The album is ‘Vision’ and here is that version of the same song:

youtube

I like both versions of the song a great deal, and you’ll find many more on Youtube.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

But turning to sources of Islamic Qur’ān exegesis would have been a natural act not only because of the difficulties of the Qur’ān almost demanded it; it was natural also because these Latin translators had been taught not merely to read text together with authoritative commentaries on them, but, in fact, to view the boundaries between text and commentary less rigidly than modern readers would. Writing commentaries was an essential part of scholarly education in the Latin West throughout the whole period in question, and one read the canonical texts together with nearly canonical commentaries on them: the Bible together with the Glossa ordinaria, or, later, the Postillae of Nicholas of Lyra; Virgil alongside Servius's commentary; Aristotle in conjunction with the brilliant commentaries of the Arab Muslim Ibn Rushd (Averroes). This "hermeneutical" nature of medieval culture brought with it a tendency to conflate text and commentary. Martin Irvine has written that "the divisions between text and commentary ... were not clearly defined ... and it is clear that for a medieval reader everything on a page -layout, changes in script, glosses, construe marks, corrections ... was experienced as an integral feature of the system of meaning that constituted the book." Though he was speaking of the early Middle Ages, the same could be said of the later medieval culture

Thomas E. Burman (Reading the Qur’ān in Latin Christendom, 1140-1560, page 45)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bible, with glossa ordinaria, Free Library of Philadelphia, c. 1250 (Lewis E 45)

BiblioPhilly is LIVE!

http://bibliophilly.library.upenn.edu/

#bibliophilly#bible#medieval#medievalmanuscript#illuminatedmanuscript#specialcollections#rare books#books#pacscl#philadelphia#philly#free library of philadelphia#christianity

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Decretals of Pope Gregory IX with the glossa ordinaria single leaves Italy, Bologna, 1330-1335

Source

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lord’s Prayer – Part 3 of 10

“Thy kingdom come” “It follows suitably, that after our adoption as sons, we should ask a kingdom which is due to sons.” -Glossa Ordinaria “This is not so said as though God did not now reign on earth, or had not reigned over it always. . . . None shall then be ignorant of His […]The Lord’s Prayer – Part 3 of 10

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A "Tree" of Genealogy

The quest for the first "family tree" has been one of my scholarly interests for years. Readers of this blog will know by now that stemmata, ramifying diagrams with ancestors at the top, were invented in antiquity (provedly before 427 CE). The inversion of those diagrams into family trees with ancestors as the roots and their descendants as boughs and leaves was a slow transformation that took well over a thousand years. One of the most interesting way-stations in that process is the invention of the term "family tree," where "tree" in its medieval sense simply meant a diagram that could be scaled up at will (just as a tree or a crystal grows) without specifically denoting that the diagram must visually resemble a natural tree. Christine Klapisch-Zuber in her major work, L'Ombre des Ancêtres, fixes the first fusion of "genealogical" and "tree" in Latin in 1312 by Bernard Gui, a Dominican inquisitor and bishop in the south of France, who wrote a history of the French kings.That means that in the latest wave of Vatican digitizations, special interest attaches to a 1369 translation of this work into French by Jean Golein.

This forms the second part of the codex Reg.lat.697, which can now be consulted online. La Généalogie des Roys de France commences at folio CXIIr. Note the flowers and tendrils which indicate that the idea of arbre is already playing on the minds of the artists. As one sees in the example below, the main line of kings is at centre-page, descending page by page through the book, and little roundel-link stemmata of each king's non-monarchical relatives are set off to one side.

This is not Golein's autograph of course. That, according to Delisle, is in the parliamentary library in Paris. The first part of the Vatican codex contains Golein's French rendering of the Flores chronicorum, also by Bernard Gui, which is a history since the time of Jesus of the popes and Roman emperors. Reg.lat.697 is wonderfully illuminated and offers us this notable conclave of cardinals:

The full list of digitizations this week (lacking 25 extra items that slipped online on Friday morning as I was finishing) follows:

Borg.copt.67,

Borg.sir.16,

Chig.C.VIII.230, with fine initials and miniatures including this Annunciation (though I could have sworn this angel has a horn!)

Ott.lat.1302,

Reg.lat.652,

Reg.lat.653,

Reg.lat.654,

Reg.lat.659,

Reg.lat.660,

Reg.lat.664,

Reg.lat.676,

Reg.lat.678,

Reg.lat.691,

Reg.lat.697, translation into French by Jean Golein of the Flores chronicorum of Bernard Gui (above)

Reg.lat.707,

Reg.lat.709,

Reg.lat.725,

Reg.lat.731,

Reg.lat.735,

Reg.lat.737,

Reg.lat.740,

Reg.lat.746,

Reg.lat.759,

Reg.lat.761,

Reg.lat.766,

Reg.lat.770,

Reg.lat.803,

Reg.lat.864,

Reg.lat.880,

Reg.lat.882,

Reg.lat.888,

Reg.lat.891,

Reg.lat.913,

Reg.lat.935, Reuilion

Sbath.251,

Urb.lat.843.pt.1,

Urb.lat.843.pt.2,

Vat.gr.1312.pt.1,

Vat.gr.1312.pt.2,

Vat.lat.1299, Expositio in Iohannem, anon.

Vat.lat.1302,

Vat.lat.1310,

Vat.lat.1317,

Vat.lat.1325,

Vat.lat.1382, Bottoni, Glossa Ordinaria, with some fine arbor juris diagrams, one of which has this interesting detail in the bottom panel:

Vat.lat.1384,

Vat.lat.1389,

Vat.lat.1430,

Vat.lat.1436,

Vat.lat.1445,

Vat.lat.1451,

Vat.lat.1453,

Vat.lat.1455,

Vat.lat.1481, Priscian

Vat.lat.1483, Priscian

Vat.lat.1543, Macrobius

Vat.lat.1547, Macrobius, commentary on Dream of Scipio

Vat.lat.1567, Homer, Iliad, in Lorenzo Valla translation to Latin

Vat.lat.1587, Horace, works, 12th century

Vat.lat.1591, Horace, poetry

Vat.lat.1599, Ovid

Vat.lat.1604, Ovid, Fasti, 12th century

Vat.lat.1605, Ovid, 15C

Vat.lat.1618, Statius, Achilleidis

Vat.lat.1623, Lucan, Civil Wars

Vat.lat.1642, Seneca, tragedies

Vat.lat.1643, Seneca, tragedies

Vat.lat.1654,

Vat.lat.1681, Boninius Mombrizio

Vat.lat.1687, Cicero, letters

Vat.lat.1690, Cicero, letters, dated 1462

Vat.lat.1692, Cicero, letters, 15C

Vat.lat.1693, Cicero, rhetorical works

Vat.lat.1702, Cicero, rhetorical works

Vat.lat.1712, Cicero, rhetorical works

Vat.lat.1714, Ad Herennium

Vat.lat.1718, Ad Herennium

Vat.lat.1724, Cicero, De finibus bonorum et malorum

Vat.lat.1726, Cicero, De finibus bonorum et malorum

Vat.lat.1727, Cicero, De finibus bonorum et malorum

Vat.lat.1728, Cicero, Tusculan Disputations

Vat.lat.1733, Cicero, Tusculan Disputations

Vat.lat.1734, Cicero, De Officiis

Vat.lat.1739, Cicero, philosophy

Vat.lat.1740, Cicero, philosophy

Vat.lat.1741, Cicero, Scipio's Dream, plus anonymous works bound in back

Vat.lat.1744, Cicero, speeches

Vat.lat.1745, Cicero, speeches

Vat.lat.1748, Cicero, speeches

Vat.lat.1751, Cicero, speeches, dated 1452

Vat.lat.1753, Cicero, speeches

Vat.lat.1755, Cicero, speeches

Vat.lat.1756, Cicero, speeches

Vat.lat.1758, Cicero, philosophical works, 15C

Vat.lat.1759, Cicero, philosophical works, 15C

Vat.lat.1760, Cicero On Laws, Plutarch Lives in Brutus translation

Vat.lat.1761, Quintilian

Vat.lat.1763, Quintilian

Vat.lat.1764, Quintilian

Vat.lat.1765, Quintilian

Vat.lat.1768, Quintilian

Vat.lat.1771, Quintilian speeches, dated 1459

Vat.lat.1774, Quintilian speeches, dated 1455

Vat.lat.1776, Latin panegyrics

Vat.lat.1777, Pliny the Younger, Letters, 15C

Vat.lat.1779, Josephus in Rufinus Latin translation

Vat.lat.1782, Phalaridis et Bruti epistulae

Vat.lat.1784, Poggio Braccolini: De varietate fortunae (On the Vicissitudes of Fortune, 1447)

Vat.lat.1786, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pius II), many key writings

Vat.lat.1789, Epistulae 1-119 of Marsilio Ficino, as later published - Rome Reborn

Vat.lat.1799, Thucydides, Peloponnesian Wars, Lorenz Valla's Latin translation; dated 1452

Vat.lat.1800, ditto

Vat.lat.1810, Polybius, 15C

Vat.lat.1826,

Vat.lat.1829, Aulus Hirtius, Caesar's Commentaries on the Gallic War, 15C

Vat.lat.6719,

Vat.lat.13619,

Vat.lat.14749,

This is Piggin's Unofficial List number 117. If you have corrections or additions, please use the comments box below. Follow me on Twitter (@JBPiggin) for news of more additions to DigiVatLib.

Delisle, L. "Notice sur les manuscrits de Bernard Gui," in Notices et extraits des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale et autres bibliothèques, XXVII, 2 (1879), 169-455. https://archive.org/

Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. L’ombre des ancêtres. Paris: Fayard, 2000.

via Blogger http://ift.tt/2txtzjT

0 notes

Photo

rapid fire

'The Smithfield Decretals' (Decretals of Gregory IX with glossa ordinaria), Toulouse ca. 1300, illuminations added in London ca. 1340

BL, Royal 10 E IV, fol. 122r

850 notes

·

View notes

Text

Logos Free Book of the Month for June 2020 - Ancient Christian Commentary on Mark (Second Edition)

Logos Free Book of the Month for June 2020 - Ancient Christian Commentary on Mark (Second Edition) -

The theme of the Logos Free Book of the Month promotion is reading Scripture with the church fathers. Logos is offering two volumes of The Ancient Christian Commentary series from IVP Academic. There are now 29 volumes in the series. From IVP Academic’s website,

The ACCS is a postcritical revival of the early commentary tradition known as the glossa ordinaria,a text artfully elaborated with…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Appello ai Cardinali di Santa Romana Chiesa. Errore del papa sulla pena di morte

Il sito statunitense “LifeSiteNews” promuove un appello, ripreso da numerosi siti cattolici, firmato da numerose personalità del mondo accademico, religioso e culturale, rivolto ai cardinali della Chiesa romana perché consiglino il Pontefice regnante di ritirare dal Catechismo la variazione aggiunta qualche giorno fa in tema di pena capitale. Anche noi lo riproponiamo ai nostri lettori insieme alla lista dei primi firmatari, tra cui la mia.

Nota: gli studiosi, sacerdoti e laici, che desiderino firmare l'Appello possono presentare il loro nome e le credenziali a questo indirizzo email: [email protected]. Una volta verificati, i nomi verranno aggiunti all'elenco dei firmatari.

Papa Francesco ha modificato il Catechismo della Chiesa cattolica nel senso che «la pena di morte è inammissibile perché attenta all'inviolabilità e alla dignità della persona ». Questa affermazione è stata compresa da molti, sia dentro che fuori la Chiesa, come un insegnamento che la pena capitale è intrinsecamente immorale e quindi è sempre illecita, anche in linea di principio.

Sebbene nessun cattolico in pratica sia obbligato a sostenere l'uso della pena di morte (e non tutti i sottoscrittori la sostengono), insegnare che la pena capitale è sempre un male intrinseco contraddirebbe la Scrittura. Che la pena di morte possa essere un mezzo legittimo per assicurare la giustizia retributiva è affermato in Genesi 9: 6 e in molti altri testi biblici, e la Chiesa sostiene che la Scrittura non può insegnare l'errore morale. La legittimità in linea di principio della pena capitale è anche insegnamento coerente del magistero per due millenni. Contrastare la Scrittura e la tradizione su questo punto metterebbe in dubbio la credibilità del magistero in generale.

Preoccupati per questa grave e scandalosa situazione, desideriamo esercitare il diritto affermato dal Codice di diritto canonico della Chiesa, che al canone 212 afferma:

§2. I fedeli hanno il diritto di manifestare ai Pastori della Chiesa le proprie necessità, soprattutto spirituali, e i propri desideri. §3. In modo proporzionato alla scienza, alla competenza e al prestigio di cui godono, essi hanno il diritto, e anzi talvolta anche il dovere, di manifestare ai sacri Pastori il loro pensiero su ciò che riguarda il bene della Chiesa; e di renderlo noto agli altri fedeli, salva restando l'integrità della fede e dei costumi e il rispetto verso i Pastori, tenendo inoltre presente l'utilità comune e la dignità della persona.

Siamo guidati anche dall'insegnamento di San Tommaso d'Aquino, che afferma:

"Quando ci fosse un pericolo per la fede, i sudditi sarebbero tenuti a rimproverare i loro prelati anche pubblicamente" e, citando Agostino (Glossa ordinaria su Galati, 2, 11), prosegue: "Pietro stesso diede l'esempio ai superiori di non sdegnare di essere corretti dai sudditi, quando capitasse loro di allontanarsi dalla retta via". ( Summa Theologiae, Parte II-II, Domanda 33, Articolo 4, ad 2)

Pertanto il sottoscritto formula il seguente appello:

Alle reverendissime eminenze, i cardinali della santa Chiesa romana. Dal momento che è una verità contenuta nella parola di Dio, e insegnata dal magistero ordinario e universale della Chiesa cattolica che i criminali possono legittimamente essere messi a morte dal potere civile quando ciò sia necessario per preservare il giusto ordine nella società civile, e dal momento che il presente pontefice romano ha più di una volta manifestato il suo rifiuto di insegnare questa dottrina, e ha invece portato una grande confusione nella Chiesa sembrando contraddirlo, inserendo nel Catechismo della Chiesa Cattolica un paragrafo che farà sì, e già sta facendo sì che molte persone, sia credenti che non credenti, suppongano che la Chiesa consideri, contrariamente alla parola di Dio, che la pena capitale è intrinsecamente malvagia, noi facciamo appello alle Vostre Eminenze affinché consiglino Sua Santità che è suo dovere porre fine a questo scandalo, e ritirare questo paragrafo dal Catechismo, e insegnare la parola di Dio senza adulterazioni; e osiamo dichiarare la nostra convinzione che questo è un dovere che Vi impegna seriamente, di fronte a Dio e di fronte alla Chiesa.

Elenco dei firmatari

Hadley Arkes

Edward N. Ney Professor in American Institutions Emeritus

Amherst College

Joseph Bessette

Alice Tweed Tuohy Professor of Government and Ethics

Claremont McKenna College

Patrick Brennan

John F. Scarpa Chair in Catholic Legal Studies

Villanova University

J. Budziszewski

Professor of Government and Philosophy

University of Texas at Austin

Isobel Camp

Professor of Philosophy

Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas

Richard Cipolla

Priest

Diocese of Bridgeport

Eric Claeys

Professor of Law

Mason University

Travis Cook

Associate Professor of Government

Belmont Abbey College

S. A. Cortright

Professor of Philosophy

Saint Mary’s College

Cyrille Dounot

Professor of Legal History

Université Clermont Auvergne

Patrick Downey

Professor of Philosophy

Saint Mary’s College

Eduardo Echeverria

Professor of Philosophy and Theology

Sacred Heart Major Seminary

Edward Feser

Associate Professor of Philosophy

Pasadena City College

Alan Fimister

Assistant Professor of Theology

St. John Vianney Theological Seminary

Luca Gili

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

Université du Québec à Montréal

Brian Harrison

Scholar in Residence

Oblates of Wisdom Study Center

L. Joseph Hebert

Professor of Political Science

St. Ambrose University

Rafael Hüntelmann

Lecturer in Philosophy

International Seminary of St. Peter

Fr. John Hunwicke

Priest

Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham

Robert C. Koons

Professor of Philosophy

University of Texas at Austin

Peter Koritansky

Associate Professor of Philosophy

University of Prince Edward Island

Peter Kwasniewski

Independent Scholar

Wausau, Wisconsin

John Lamont

Fellow of Theology and Philosophy

Australian Catholic University

Roberto de Mattei

Author

The Second Vatican Council: An Unwritten Story

Robert T. Miller

Professor of Law

University of Iowa

Gerald Murray

Priest

Archdiocese of New York

Lukas Novak

Lecturer in Philosophy

University of South Bohemia

Thomas Osborne

Professor of Philosophy

University of St. Thomas

Michael Pakaluk

Professor of Ethics

Catholic University of America

Claudio Pierantoni

Professor of Medieval Philosophy

University of Chile

Thomas Pink

Professor of Philosophy

King’s College London

Andrew Pinsent

Research Director of the Ian Ramsey Centre

University of Oxford

Alyssa Pitstick

Independent Scholar

Spokane

Donald S. Prudlo

Professor of Ancient and Medieval History

Jacksonville State University

Anselm Ramelow

Chair of the Department of Philosophy

Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology

George W. Rutler

Priest

Archdiocese of New York

Matthew Schmitz

Senior Editor

First Things

Josef Seifert

Founding Rector

International Academy of Philosophy

Joseph Shaw

Fellow of St Benet’s Hall

University of Oxford

Anna Silvas

Adjunct Senior Research Fellow

University of New England

Michael Sirilla

Professor of Dogmatic and Systematic Theology

Franciscan University of Steubenville

Joseph G. Trabbic

Associate Professor of Philosophy

Ave Maria University

Giovanni Turco

Associate Professor of Philosophy

University of Udine

Michael Uhlmann

Professor of Government

Claremont McKenna Collegre

John Zuhlsdorf

Priest

Diocese of Velletri-Segni

Dame Colleen Bayer DSG

,

Founder, Family Life International NZ

James Bogle Esq.

, TD MA Dip Law, barrister (trial attorney), former President FIUV, former Chairman of the Catholic Union of Great Britain

Fr. John Boyle JCL

Judie Brown, President, American Life League

Fr. Michael Gilmary Cermak

MMA

Fr. Linus F Clovis

, Ph.D, JCL, M.SC., STB

Hon. Donald J. Devine

, Senior Scholar, The Fund for American Studies

Dr. Maria Guarini

, editor of the website

Chiesa e postconcilio

John D. Hartigan

, retired attorney and past member, Public Policy Committee of the New York State Catholic Conference

Dr. Maike Hickson

, journalist

Dr. Robert Hickson

, Retired Professor of Literature and Strategic-Cultural Studies

Fr. Albert Kallio

, Professor of Philosophy at Our Lady of Guadalupe Monastery, New Mexico

Fr. Serafino M. Lanzetta

STD

Dr. Robert Lazu,

Independent Scholar and Writer

Dr. James P. Lucier

, Former Staff Director, U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

Dr. Pietro De Marco

, former professor of Sociology of Religion, University of Florence

Dr. Joseph Martin

, Associate Professor of Communication, Montreat College

Dr. Brian McCall

, Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and Associate Director of the Law Center, Orpha and Maurice Merrill Professor in Law, University of Oklahoma

Fr. Paul McDonald

, parish priest of Chippawa, Ontario

Dr. Stéphane Mercier

, former lecturer in Philosophy at the Catholic University of Louvain (Belgium)

Fr. Alfredo Morselli

, SSL, parish priest in the diocese of Bologna

Maureen Mullarkey

, Senior Contributor,

The Federalist

Fr. Reto Nay

Dr. Claude E. Newbury

M.B., B.Ch., D.T.M&H., D.O.H., M.F.G.P., D.C.H., D.P.H., D.A., M. Med; Former Director of Human Life International in Africa south of the Sahara

Giorgio Nicolini

, Writer, Director of Tele Maria

Dr. Paolo Pasqualucci

, retired Professor of Philosophy, University of Perugia, Italy

Prof. Enrico Maria Radaelli

, Philosopher

Richard M. Reinsch II

, Editor, Law and Liberty

R. J. Stove

, Writer and Editor

Fr. Glen Tattersall

, Parish Priest, Parish of Bl. John Henry Newman, archdiocese of Melbourne; Rector, St Aloysius’ Church

Dr. Thomas Ward

, Founder of the National Association of Catholic Families and former Corresponding Member of the Pontifical Academy for Life

Fr. Claude Barthe

, Diocesan priest

Donna F. Bethell

, J.D. Washington, DC

Prof. Michele Gaslini

, Professor of Public Law at the University of Udine

Brother Andre Marie

, M.I.C.M., MA (Dogmatic Theology), Prior of Saint Benedict Center, New Hampshire

Fr. John Osman

, diocese of Birmingham, England

Fr. Alberto Strumia

, retired professor of Mathematical Physics, University of Bari, Italy

Guillaume de Thieulloy

, PhD in political science, editor of the French Blog Le Salon Beige

Marco Tosatti

, Journalist, Vatican observer

Christine Vollmer

, former member of the Pontifical Council for Family and the Pontifical Academy for Life

0 notes