#given that he /did/ have provincial-level prominence

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

you've mentioned places like great lakes and new westminster. are these states or provinces, or just general regions? how is sunderland divided administratively?

Yes, hello, these are provinces and Sunderland has ten of them! They look like this (roughly, it's a work in progress)

The ten provinces are:

Alexandria, Algonquin, Cheyenne, Danforth, Great Lakes, Iroquois, Lakota, Missoria, and New Westminster

Each province is represented by a provincial government and they are considered to have shared sovereignty with the federal government. Each province has a Governor-General, who represents the Crown aka Louis V. Each province has a certain amount of MPs (Members of Parliament) who sit in either the House of Commons (lower chamber) or the Senate (upper chamber). MPs represent the legislative interests of their provinces and municipalities at the federal level. There is a fixed number of twenty senators (two from each province), who are appointed by the King on the advice of his prime minister, while members of the House of Commons are elected directly in federal elections, with the number of MPs depending on the population of their province, the larger the province the more seats they have in the House of Commons.

In Sunderland, you don't vote for the prime minister directly, you vote for them through your MPs. So, if the potential prime minister (the party leader) belongs to the Liberal party, you vote for the Liberal MP representing your area, if that Liberal MP wins they have a seat in the House of Commons. If a majority of the MPs in the House are of a certain party (the main two being Liberals and Tory Conservatives), their party leader becomes Prime Minister with a majority government. If a party wins the most seats but fails to hold a majority, this is called a minority government and the ruling party has less absolute authority and will have to coalition-build with other parties in order to get things done. So, it's extremely important that the Prime Minister and his Ministers are supported by their MPs in the House of Commons, this is something Sunderland's current prime minister is struggling with. MPs can resign, retire, switch parties, or die on a whim, so the amount of power a government has can fluctuate.

The Senate is more of the wild-west as Louis is free to appoint to whoever he wishes for whatever reason he wants (on the advice of the prime minister, but he can ignore the advice). The general rule is that these people have to be of noteworthy public standing, but they don't have to be politicians. They can be activists, lawyers, civil servants, etc. If the King tries to appoint a friend or a family member, nothing but public outrage can stop him. So, naturally, Louis doesn't appoint friends or family and has grilled James and later Nicholas on this being something you should never do as King. Louis's Daddy James II didn't have the same restraint. . . Nor did King Nicholas (removing the leftists meant sacking the senate against them) . . . Or King George who fought tooth and nail to have his moronic son-in-law appointed to the Senate in 1898 . . . but it's not a corrupt system at all, I swear . . .

The Senate has the job of approving the potential laws (bills) passed to them by the House of Commons, in short: if they dislike it, they send it back or veto it, if they like it, they'll hand it over the Louis for royal assent. Believe it or not, the fact that there is an unelected body, that serves until the age of SIXTY-FIVE, picking and choosing what laws get greenlit has caused SCANDALS, with the protests happening in this post being triggered by the Senate rejecting an affordable housing bill forwarded by the Liberals in the House.

Until 1999, those appointed to the Senate were given a title of nobility, typically an Earldom or a Dukedom if The King thinks you're a really good boy. The families of Irene and Tatiana are descended from prominent Senators, this is where their family titles originated from. This tradition ended when the first woman was appointed to the Senate in 1999, since women can't inherit noble titles, Louis stopped the practice altogether, instead of . . .y'know, just getting Parliament to allow women the ability to hold noble titles suo jure. Louis can technically still hand out noble titles, but he informally agreed to stop granting titles to non-family members. People at the time viewed this as him becoming more egalitarian and progressive for the new millennia, but in reality, he was just keeping his crop of aristocrat ass-likers more exclusive. So, now your senators aren't literal dukes and earls . . . yay, progress?

Finally: The "commander-in-chief" of a province is called the premier. Think of him like a governor in the United States. These guys are elected through provincial elections and they form their own legislative bodies to handle provincial legislation (healthcare, education, etc.). They operate largely independently from the federal government and have historically resisted federal micro-management.

If you're familiar with American geography or history, you'll know that the provinces have Indigenous names (Cheyenne, Lakota, Missouria, Iroquois, Algonquin) and others are named after royalty (Alexandria and Louisia) and prominent figures/locations (New Westminster, Danforth) . . . the implications of these names say a lot about Sunderland's history.

Hopefully, I'll be able to update my map soon, hope you enjoyed the political lesson.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rí, or commonly ríg is an ancient Gaelic word meaning “King/Ruler”, and while the modern Irish word is still the same the modern Scots word is rìgh; Rí has the same meaning as the Sanskrit raja, and the Latin rex/regis for comparison.

There were multiple levels of Rí; rí benn (king of peaks) or rí tuaithe (king of a single tribe) was commonly a petty king of a single territory, who held no legal authority outside of that territory. The size of the territory may differ but an example of what I mean would be Umhaill, which had 20 rulers, including the famous Grace O’Malley

Rí buiden (king of bands), also rí tuath (king of [many] tribes) was a regional King to which several other territories and rí benn were subordinate. While still a “petty king” in a sense, a rí tuath (also known as a ruirí or “overking” though apparently a ruirí was also superior to a rí tuath so /shrugs/) was capable of getting provincial-level prominence, and in some rare cases even a provincial kingship (more on that in a bit). Regardless, he was considered fully sovereign in any case. Examples of a rí tuath would be the Kings of Breifne or the Kings of Moylurg

And then we have the rí ruirech, the “king of over-kings”. These were the provincial Kings that ruled over the provinces of Ireland; Munster, Connacht, Leinster, Ulster and Mide (according to the Ulster legends these were the main five). These kings were also referred to as ri bunaid cach cinn ("ultimate king of every individual") which is one heck of a mouthful

And, finally, we have the ard rí; the High King (of Ireland), the supreme ruler of all provinces, who answered to no higher authority (except the Gods probably lol). Now in theory the rí ruirech were subordinate to the High King, however the power of the High King varies considerably in Irish stories and Mythology, and he was usually no more than a figurehead.

According to tradition, the High King was crowned on the Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) upon the Hill of Tara in Meath, Leinster. When a candidate for the throne stood upon it, the monument would let forth a loud roar of joy. Supposedly this monument ended up getting split in half by Cu Chulainn (he used his sword uwu) when it didn’t recognize Cu’s chosen candidate as the High King. Said chosen candidate was his foster-son, Lugaid Riab nDerg (there’s a lot of incest involved with this guy’s story just a warning, but hey at least it’s all consensual?) though he did end up becoming a High King after this event, proooobably because nobody wanted to get on Cu’s bad side lmao. Regardless, Lia Fáil never roared again except under Conn of the Hundred Battles

(Also as an aside, there’s a lot of conflicting thoughts about Lugaid, as there are multiple Lugaid’s in the mythos and supposedly this Lugaid ruled for over 20 years which can’t be possible considering that Cu dies when he was 17 but was also there when Lugaid died. [Also this is where the “pissing contest” story came from though it wasn’t Cu doing the pissing it was a bunch of women anyWAY]

Granted though there are two separate stories about his death but again there is some debate over whether the second story was actually him or if he simply got confused with a separate, minor character from the Ulster Cycle who was associated with Cu Chulainn. Fun times for us mythos bitches I guess)

#mythology#history#random facts#this one fits all three because I have The Range#Fionn was probably a ri tuatha#given that he /did/ have provincial-level prominence#but was not a provincial king himself#also he had multiple tribes/clans within his fianna soooo

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

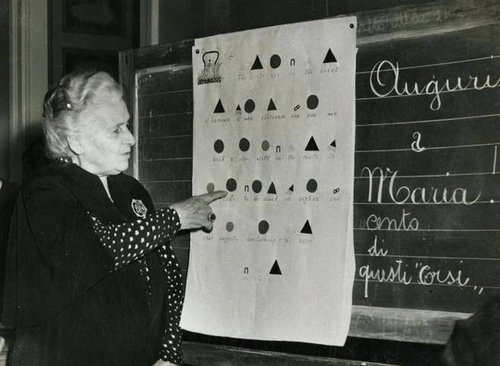

Maria Montessori

“Do not tell them how to do it. Show them how to do it and do not say a word. If you tell them, they will watch your lips move. If you show them, they will want it to do it themselves.”

Montessori’s Life

Maria Montessori was born on August 31, 1870, in the provincial town of Chiaravalle, Italy, to middle-class, well-educated parents. Her father, Alessandro Montessori, 33 years old at the time, was an official of the Ministry of Finance working in the local state-run tobacco factory. Her mother, Renilde Stoppani, 25 years old, was well educated for the times and was the great-niece of Italian geologist and paleontologist Antonio Stoppani.

When she was 12, her parents moved to Rome and encouraged her to become a teacher, the only career open to women at the time. While she did not have any particular mentor, she was very close to her mother who readily encouraged her. She also had a loving relationship with her father, although he disagreed with her choice to continue her education.

She was first interested in mathematics, and decided on engineering, but eventually became interested in biology and finally determined to enter medical school. Facing her father's resistance but armed with her mother's support, Montessori went on to graduate with high honors from the medical school of the University of Rome in 1896. In so doing, Montessori became the first female doctor in Italy.

On March 31, 1898, her only child – a son named Mario Montessori was born. Mario Montessori was born out of her love affair with Giuseppe Montesano, a fellow doctor who was co-director with her of the Orthophrenic School of Rome.

Montessori died of a cerebral hemorrhage on May 6, 1952, at the age of 81 in Noordwijk, South Holland, Netherlands, receiving in her later years’ honorary degrees and tributes for her work throughout the world.

Montessori’s Careers

From 1896 to 1901, Montessori worked with and researched so-called "phrenasthenic" children—in modern terms, children experiencing some form of mental retardation, illness, or disability. She also began to travel, study, speak, and publish nationally and internationally, coming to prominence as an advocate for women's rights and education for mentally disabled children.

Montessori continued with her research at the University's psychiatric clinic, and in 1897 she was accepted as a voluntary assistant there. As part of her work, she visited asylums in Rome where she observed children with mental disabilities, observations which were fundamental to her future educational work. She also read and studied the works of 19th-century physicians and educators Jean Marc Gaspard Itard and Édouard Séguin, who greatly influenced her work. Also in 1897, Montessori audited the University courses in pedagogy and read "all the major works on educational theory of the past two hundred years".

In 1897 Montessori spoke on societal responsibility for juvenile delinquency at the National Congress of Medicine in Turin. In 1898, she wrote several articles and spoke again at the First Pedagogical Conference of Turin, urging the creation of special classes and institutions for mentally disabled children, as well as teacher training for their instructors. She joined the board of the National League and was appointed as a lecturer in hygiene and anthropology at one of the two teacher-training colleges for women in Italy.

Montessori became the director of the Orthophrenic School for developmentally disabled children in 1900. There she began to extensively research early childhood development and education. Montessori began to conceptualize her own method of applying their educational theories, which she tested through hands-on scientific observation of students at the Orthophrenic School. Montessori found the resulting improvement in students' development remarkable. She spread her research findings in speeches throughout Europe, also using her platform to advocate for women's and children's rights.

Montessori was named director of the State Orthophrentic School in 1889. She worked with the children there for two years. All-day she taught in the school and then worked preparing new materials, making notes and observations and reflecting on her work. These two years she regarded as her "true degree" in education. To her amazement, she found these children could learn many things that had seemed impossible. This conviction led Montessori to devote her energies to the field of education for the remainder of her life.

Montessori’s Contributions to Education

The Montessori Method

In her book she outlines a typical winter's day of lessons, starting at 09:00 am and finishing at 04:00 pm:

9–10. Entrance. Greeting. Inspection as to personal cleanliness. Exercises of practical life; helping one another to take off and put on the aprons. Going over the room to see that everything is dusted and in order. Language: Conversation period: Children give an account of the events of the day before. Religious exercises.

10–11. Intellectual exercises. Objective lessons interrupted by short rest periods. Nomenclature, Sense exercises.

11–11:30. Simple gymnastics: Ordinary movements done gracefully, the normal position of the body, walking, marching in line, salutations, movements for attention, placing of objects gracefully.

11:30–12. Luncheon: Short prayer.

12–1. Free games.

1–2. Directed games, if possible, in the open air. During this period the older children, in turn, go through with the exercises of practical life, cleaning the room, dusting, putting the material in order. General inspection for cleanliness: Conversation.

2–3. Manual work. Clay modeling, design, etc.

3–4. Collective gymnastics and songs, if possible in the open air. Exercises to develop forethought: Visiting, and caring for, the plants and animals.

She felt by working independently children could reach new levels of autonomy and become self-motivated to reach new levels of understanding. Montessori also came to believe that acknowledging all children as individuals and treating them as such would yield better learning and fulfilled potential in each particular child. She began to see independence as the aim of education, and the role of the teacher as an observer and director of children's innate psychological development.

She also knew that, in order to consider these developments as representing universal truths, she must study them under different conditions and be able to reproduce them. In this spirit that same year, a second school was opened in San Lorenzo, a third in Milan, and a fourth in Rome in 1908, the latter for children of well-to-do parents. By 1909, all of Italian Switzerland began using Montessori's methods in their orphan asylums and children's houses.

Word of Montessori's work spread rapidly. Visitors from all over the world arrived at the Montessori schools to verify with their own eyes the reports of these "remarkable children." Montessori began a life of world travel - establishing schools and teacher training centers, lecturing, and writing. The first comprehensive account of her work, The Montessori Method, was published in 1909.

In 1915, Montessori returned to Europe and took up residence in Barcelona, Spain. Over the next 20 years, Montessori traveled and lectured widely in Europe and gave numerous teacher training courses. Montessori education experienced significant growth in Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

Montessori’s Significant Awards & Legacy

In 1949, the first training course for birth to three years of age, called the Scuola Assistenti all'infanzia (Montessori School for Assistants to Infancy) was established. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Montessori was also awarded the French Legion of Honor, Officer of the Dutch Order of Orange Nassau, and received an Honorary Doctorate of the University of Amsterdam. In 1950 she visited Scandinavia, represented Italy at the UNESCO conference in Florence, presented at the 29th international training course in Perugia, gave a national course in Rome, published a fifth edition of Il Metodo with the new title La Scoperta del Bambino (The Discovery of the Child), and was again nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1951 she participated in the 9th International Montessori Congress in London, gave a training course in Innsbruck, was nominated for the third time for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Maria Montessori and Montessori schools were featured on coins and banknotes of Italy, and on stamps of the Netherlands, India, Italy, Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Montessori’s Works & Writings

Montessori published a number of books, articles, and pamphlets during her lifetime, often in Italian, but sometimes first in English. However, many of her later works were transcribed from her lectures, often in translation, and only later published in book form.

Montessori's major works are given here in order of their first publication, with significant revisions and translations:

(1909) Il Metodo della Pedagogia Scientifica applicato all'educazione infantile nelle Case dei Bambini

revised in 1913, 1926, and 1935; revised and reissued in 1950 as La scoperta del bambino

(1912) English edition: The Montessori Method: Scientific Pedagogy as Applied to Child Education in the Children's Houses

(1948) Revised and expanded English edition issued as The Discovery of the Child

(1950) Revised and reissued in Italian as La scoperta del bambino

(1910) Antropologia Pedagogica

(1913) English edition: Pedagogical Anthropology

(1914) Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook

(1921) Italian edition: Manuale di pedagogia scientifica

(1916) L'autoeducazione nelle scuole elementari

(1917) English edition: The Advanced Montessori Method, Vol. I: Spontaneous Activity in Education; Vol. II: The Montessori Elementary Materia

(1922) I bambini viventi nella Chiesa

(1929) English edition: The Child in the Church, Maria Montessori’s first book on the Catholic liturgy from the child’s point of view.

(1923) Das Kind in der Familie (German)

(1929) English edition: The Child in the Family

(1936) Italian edition: Il bambino in famiglia

(1934) Psico Geométria (Spanish)

(2011) English edition: Psychogeometry

(1934) Psico Aritmética

(1971) Italian edition: Psicoaritmetica

(1936) L'Enfant(French)

(1936) English edition: The Secret of Childhood

(1938) Il segreto dell'infanzia

(1948) De l'enfant à l'adolescent

(1948) English edition: From Childhood to Adolescence

(1949) Dall'infanzia all'adolescenza

(1949) Educazione e pace

(1949) English edition: Peace and Education

(1949) Formazione dell'uomo

(1949) English edition: The Formation of Man

(1949) The Absorbent Mind

(1952) La mente del bambino. Mente assorbente

(1947) Education for a New World

(1970) Italian edition: Educazione per un mondo nuovo

(1947) To Educate the Human Potential

(1970) Italian edition: Come educare il potenziale umano

1 note

·

View note

Link

When Indonesia’s New Order regime met its end in May 1998, I was a PhD student researching Indonesian opposition movements while teaching Indonesian language and politics at a university in Sydney. Along with other lecturers and students, I watched the live broadcast of Suharto’s resignation speech, listening to the words of one of our colleagues as she translated the president’s fateful words for Australian TV. Clustered around a television screen in a poky AV lab, everyone present felt awed by the immensity of what we were witnessing, relieved that a dangerous political impasse had been broken, and nervously hopeful about the future after so many long years of political stagnation.

The extraordinary achievements of political reform in the years that followed formed one of the great success stories of the so-called “third wave” of democratisation—the worldwide surge of regime change that began in Southern Europe in the mid-1970s and then spread through Latin America, Africa and Asia. The post-Suharto democracy has now lasted longer than did Indonesia’s earlier period of parliamentary democracy (1950–1957), and the subsequent Guided Democracy regime (1957–65). While it still has another dozen years to pass the record set by Suharto’s New Order, Indonesian democracy has proved that it has staying power.

What few would question, though, is that the quality of Indonesia’s democracy was a problem from the beginning—and that under President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) democratic quality has begun to slide dramatically.

Earlier this year, the Economist Intelligence Unit gave Indonesia its largest downgrading in its Democracy Index since scoring began in 2006. With a score of 6.39 out of a possible maximum of 10, the country is now bumping down toward the bottom of the index’s category of “flawed democracies”, on the verge—if it sinks just a little lower—of crossing into the category of “hybrid regime”. This downgrading of Indonesia’s position follows similar drops for the country in other democracy indices like the Freedom in the World surveycompiled by Freedom House.

Indonesia’s trajectory is not bucking the global trend. Around the world, democracy is in retreat. Freedom House says democracy is facing “its most serious crisis in decades”, with 71 countries experiencing declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2017 and only 35 registering gains, making 2017 the twelfth year in a row showing global democratic recession.

Unlike during an earlier era of military coups, today the primary source of democratic backsliding is elected politicians. Leaders such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán undermine the rule of law, manipulate institutions for their own political advantage, and restrict the space for democratic opposition. Elected despotism is, increasingly, the order of the day. Indeed, as I argue here, the primary threat to Indonesia’s democratic system today comes not from actors outside the arena of formal politics, like the military or Islamic extremists, but the politicians that Indonesians themselves have chosen.

Eroding democracy, in democracy’s name

Over recent years, successive central governments have introduced restrictions on democratic rights and freedoms in Indonesia. This process began during the second term of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono presidency, which began in 2009, but has accelerated significantly since the election of Jokowi in 2014.

The immediate backdrop to some of the most regressive moves has been the contest between Jokowi and his Islamist and other detractors, especially in the wake of the mobilisations against the Chinese Christian governor of Jakarta, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok).

In July 2017, Jokowi issued a new regulation, subsequently approved by the national legislature, that granted the authorities sweeping powers to outlaw social organisations that they deemed a threat to the national ideology of Pancasila. The new law actually built on an earlier, somewhat less harmful version issued during the Yudhoyono presidency. The government quickly took advantage of the law to outlaw Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia, a large Islamist organisation that, while openly rejecting pluralism and democracy, has also pursued its goals non-violently.

At the same time, several critics of President Jokowi have been arrested on charges of makar, or rebellion (though it appears the authorities may not be proceeding with these cases). The government has coercively intervened in the internal affairs of Indonesia’s political parties so as to attain a majority in parliament. A prominent media mogul supportive of anti-Jokowi political causes was slapped with what appeared to many to be politically-motivated criminal investigations. Foreign NGOs and funding agencies face an increasingly restrictive operating climate.

Meanwhile, the military has been brought back into governance, at least at the lowest levels of the state, with the government reinstituting the Suharto-era of babinsa—junior officers assigned to villages—and promoting military involvement in non-security related functions as fertiliser distribution.

A related source of decline in the quality of Indonesia’s democracy, meanwhile, is intolerant attitudes toward religious and other social minorities, alongside narrowing public space for critical discussion of religious topics, and the growing ascendancy of religious conservatism in social and political life.

A few years ago, religious minorities such as Shia Muslims and members of the Ahmadiyah sect were the most frequent target of violent attack and restrictions; recently, the country has been gripped by an anti-LGBT panic. It is possible that Indonesia will soon criminalise homosexuality. At a time when many third-wave democracies, notably those in Latin America, are becoming more respectful of the rights of homosexuals and other sexual minorities, Indonesia is moving in the opposite direction.

While none of these government measures has in itself been a knockout blow against freedom of expression and association, taken together they constitute a significant erosion of democratic space. As the global democracy indices recognise, it already makes no sense to speak of Indonesia as being a full, or liberal, democracy. These developments point toward, at best, Indonesia’s becoming an increasingly illiberal democracy, where electoral contestation continues as a foundation of the polity, but coexists with significant restrictions on political and religious freedoms, and where the rights of at least some minority groups are not protected.

Defying the odds

But the picture is not unremittingly gloomy. Indonesia has a long way to go before it sinks to the level of Russia or even Turkey, and it is worth pausing to contextualise the recent trends in the context of the achievements of Indonesian democracy over the last 20 years.

Many of these gains remain firmly established. Democratic electoral competition has become an essential part of Indonesia’s political architecture. Apart from sporadic calls to do away with direct elections of regional heads (pilkada), no mainstream political force calls openly for electoral mechanisms to be replaced with a rival organising principle. Even when the authoritarian populist Prabowo Subianto ran for the presidency in 2014, he had to disguise his anti-democratic impulses with talk of returning to Indonesia’s original 1945 Constitution—i.e. the version of the constitution that the Suharto regime had relied upon, but which seems attractive to many Indonesians because it resonates with Indonesia’s nationalist history.

Public opinion surveys demonstrate continuing strong support both for democracy as an ideal, and for the democratic system actually practised in Indonesia. Moreover, Indonesia still has a relatively robust civil society and independent media, at least in the major cities. Political debate on most topics remains lively. For example, it is generally easy for critics of President Jokowi to express their views loudly and directly—not something that can be done in most of Indonesia’s ASEAN neighbours. Indeed, some of the recent attempts to curtail free speech has been prompted by concerns about the ease with which so-called “fake news”, conspiracy theories and wild rumours circulate through social media.

Moreover, it is worth emphasising that many of the very people who pose the greatest threat to Indonesian democracy—its elites—have in fact bought into the new system. Elites throughout the country have benefited from the new opportunities for social mobility and material accumulation they have been able to secure through elections and decentralisation.

A recent survey of members of provincial parliaments, conducted by Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI) in cooperation with the Australian National University, shows that while Indonesia’s regional political elites are certainly illiberal on many issues, they are strongly supportive of electoral democracy as a system of government. Indeed, on many questions their views are markedly moredemocratic than the general population.

For example, when asked to judge on a 10-point scale whether democracy was a suitable system of government for Indonesia, the average score provided by these parliamentarians was 8.14—not far from the maximum score of 10 for “absolutely suitable”, and a full point higher than the 7.14 given by respondents in LSI’s most recent general population survey in which the same question was asked. Likewise, these legislators were considerably less likely to support military rule or rule by a strong leader than were the population at large.

These responses are significant, because democracy is not simply a system favouring protection of civil liberties and ensuring accountability of officials to the public (areas where Indonesia has, to spin it positively, a mixed record). It is also a means of ensuring regular and open competition between rival political elites.

Viewed in this light—as a means of regulating elite circulation—Indonesian democracy looks more robust. Though elite buy-in does not preclude continuing erosion of civil liberties at the centre, or guarantee protection of unpopular minorities, it does pose a considerable obstacle to the return of a command-system of centralised authority such as that which ruled Indonesia under the New Order.

A consolidated low-quality democracy?

It is in no small part due to this elite support for the status quo—in part begrudging and contingent, but nevertheless real—that Indonesian democracy has proven resilient to potential spoilers. This resilience is in itself an important achievement: there is a body of scholarly literature that suggests that once a country has experienced democratic rule for a lengthy period—one scholar, Milan Svolik, puts the figure at 17–20 years—it is very unlikely to regress toward outright authoritarianism.

Moreover, Indonesia’s present backsliding—as with the wider global trend—can arguably be viewed in part as a retreat that comes after a democratic high water mark is reached. If the last century is any guide, democratic progress and regression come in worldwide waves: the third wave of democratisation which began in the 1970s was preceded by two earlier waves that came in the wake of World War I and World War II. In both periods, many of the newly democratic regimes that were established in the wake of the breakup of multinational and colonial empires did not last long. But in each case, these retreats were superseded by new waves of democratisation.

Obviously, we need to be cautious when thinking about future trends. We are in the midst of a new world-historic transition and we do not know whether we are merely at the start of the worldwide retreat of democracy, or already near the turning of the authoritarian tide.

Most worryingly, some of the ingredients giving rise to democratic weakening in the current period are new, and do not yet show signs of abating. Strikingly, for the first time in decades, there are signs of weakness in advanced democracies—both in terms of declining popular support for democracy as measured in some opinion polls, and in the election of would-be autocrats such as Donald Trump. Wealth inequality in many countries is reaching levels not seen since the dawn of the age of mass democracy a century ago, with the result that the growing political dominance of oligarchs—a major focus of academic analysis in Indonesia—is a worldwide trend. Meanwhile, new communication technologies of the internet and social media are opening up participation in political debate, but also driving a polarisation that undermines a shared public sphere and delegitimises opponents.

The forces conspiring to undermine democracy globally, the resulting unsupportive international climate for Indonesia’s democratic revival, plus the growing signs of democratic decline in the country itself, should make us cautious about celebrating the twentieth anniversary of reformasi with a tone of triumph.

Nevertheless, it is worth viewing contemporary predicaments from the perspective of those of us who watched Suharto resign 20 years ago. Back then, as we watched Suharto read out his speech, my friends and I mixed astonishment, excitement and relief with genuine anxiety about what was in store for Indonesia. Many expert commentators were very sceptical of the notion that Indonesia could become a successful democracy. Some urged caution, pointing to the acrimony that had dogged Indonesia’s earlier democratic experiment in the 1950s, and highlighting the under-development of civilian politics and the continuing influence of the armed forces.

Indonesian democracy exceeded most expectations back then. It might just do so again.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evil Canadians

[[This is an excerpt of an alternate history role playing game that involved psychics, wizards, and a cold war that never ended I wrote in between 2002-2004. This is an edited part of the section about Canada that several Canadian friends asked to see...]]

Canada is the world’s second largest country and occupies most of the North American Land mass, sharing with the United States of America what was once the world’s longest undefended border. Though not extensively militarized until the Russo-American War, going as far back as the early 1990s many of the border provinces coming under control of the Dominion Unity Party (DUP) began paramilitary patrols to augment the official border crossing points. Canada was settled as British and French colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. France surrendered to Britain its colony of New France, an area that composes present-day Quebec and Ontario at the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

----

The Ungava Incident

For almost forty years United States Air Force Strategic Air Command (SAC) nuclear-armed bombers flew armed over Canadian territory near the Arctic Circle on routine patrols. These aircraft, by the 1980s aging B-52s with a host of electrical problems, flew from bases within the Continental United States, looped over the northern reaches of Canada, and than landed again at their bases in middle America. Twice in the 1960s SAC B-52 on similar routes crashed with nuclear weapons on foreign soil. The first occurred on January 17, 1966 near Palomares, Spain during an in-flight refueling accident, three bombs were scattered over farmer’s fields and one in the ocean. All four were recovered and the residents of the small Spanish town paid nearly $800,000 in compensation. Just over two years later on January 22, 1968 another B-52 crashed near Thule Air Force Base, Greenland after a fire broke out in the navigator’s compartment. Three hydrogen bombs were scattered across the ice, and one melted through and sunk to the bottom of Baffin Bay, unrecoverable. The incident over Greenland, a Danish possession, caused massive protests in Denmark, and briefly strained relations between the two countries.

These were nothing in comparison to the December 12, 1984 explosion of at least one (though some theorize that it may have been as many as three) hydrogen bomb over the Ungava Peninsula, in northern Quebec. The explosion vaporized the B-52 that the bombs were believed to have come from, killing the crew, and making investigation of the cause of the explosion nearly impossible. Because the region was sparsely populated, mostly by isolated fishing villages, no one knows exactly how many people died, though estimates by both the Canadian and United States governments place the direct death toll from the explosion to be around 450. This does not include the thousands of cases of radiation poisoning from fallout in Quebec, the Hudson Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as fisheries in the North Atlantic and as far away as western Europe.

The United States Air Force immediately sent teams to help relocate survivors and those in the worst affected areas, but the estimated $4,000,000 in compensation has been considered inadequate and insulting by many Canadians and some of those eligible for settlements have refused them in favor of civil suits filed in American courts against the Air Force. The Department of Defense has attempted to have the suits thrown out citing national security concerns, but several Federal judges have kept it alive, even after decades of delay. The mysterious deaths of one of those judges, and of a prominent Ungava survivors advocate are widely suspected to be the result of U.S. military covert operatives.

The Reagan administration dismissed concerns that the incident might permanently soured relations with the northern neighbor. Other American observers wondered though, as nearly fifty percent of Canadian Air Force personnel were recalled from joint programs such as the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). Though many of those same officers returned in the following years, but military cooperation between the neighbors has never been the same. Polls carried out in the United States ten and twenty years after the incident show close to forty percent of the American people did not even know that it had occurred, and listed Canada as one of the United States’ closest allies around the world.

-----

The Friendly Dictatorship?

The Prime Minister of Canada has what are often considered extraordinary powers in comparison to other western leaders. Because of a system of strict party discipline within the Canadian House of Commons, an elected member faces great difficulty in voting against the party line (set by the Prime Minister). If any member of the Prime Minister’s governing party votes against any new legislation, he or she may be expelled from the party. An expelled member must sit as an independent, without the right to ask a question, raise any issue before the Parliament, and stands little chance of winning re-election without the party’s resources. These measures mean that members of the governing party almost always follow the will of the Prime Minister. This was best exemplified by former Prime Minster, Pierre Trudeau, who referred to the backbenchers of the (than ruling) Liberal party as “trained seals” and the opposition backbenchers as “noblies when they are fifty yards away from the House of Commons.” The lack of checks and balances as theoretically seen within the US system has lead some to question such power, especially with the unexpected term of Walter Bechmann’s Dominion Unity Party, which has held the office since 2003

The major counterbalance to the power of the Prime Minster of Canada are near autonomous powers of the provincial premiers. They are required to agree to any constitutional change, and must be be consulted over new domestic initiatives within their area of responsibility. Unsurprisingly, traditionally the most difficult primeir to deal with has been the Priemer of Quebec.

The Rise of the DUP

Traditionally there have been two major national parities within Canada, the Liberal Party of Canada, the Conservative Party of Canada (or predecessors under other names), with a large regional party the Bloc Québécois following behind. None of these players took much notice as a small upstart, the Dominion Unity Party (DUP), began to win power on the provincial level in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Rising out of the movements collectively known as “Prairie Socialists” the DUP advocated traditional values, wide ranging social programs, a strong military, and a resistance to what they characterized as the cuddling of the Quebec separatists by Ottawa.

The economic and ecological disaster that was the Ungava Incident, the lack luster American response, and Ottawa’s inability to force the issue lead to a growing sense that Canada had seeded too much of its responsibilities to the United States. If Ottawa would not keep the French in line, or Washington from walking all over the country, than someone would. And that someone, the DUP claimed, was them. Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s the DUP gained control of all of Western Canada on the Provincial level, and became the official opposition party after the collapse of the Progressive Conservatives.

Who done it?

The leak of the incriminating file on Liberal Party funding to the CBC have become the Deep Throat of Canadian political history. Both their origins and even their authenticity have been vigorously questioned (and denied). Some leading theories include:

That the deputy prime minister leaked the documents in an effort to force Chrétien to resign in favor of former finance minister Paul Martin. He was taken by surprise when Martin did not win the election and has dropped out of public life.

The Bloc Québécois leaked them after obtaining them by means unknown. Thinking that they would have an easier time working with a Conservative government, or at least a better chance of winning the next independence referendum, it blew up in their face when instead of getting the Tories they ended up with their worst nightmare.

One of the Canadian intelligence or security services leaked the document—the finger is usually pointed at the FSS—either out of patriotism or out of cynical and very illegal manipulation of the political process.

One thing is clear to those that are familiar with Jean Chrétien. Few believe that he actually knew about the dirty dealings with the American companies. If the documents were legitimate to begin with.

----

The government of Jean Chrétien came under fire in 2003 as documents began to surface in the press linking the Liberals to campaign funding directly by American corporations with ties to the Department of Defense. The implication being, though never quite proven, that an agreement was in the works to arrange for the Ungava lawsuits to be settled or dropped entirely in return for the illegal funds. The exact origins of the leaked documents have never been established. So angry was the Canadian electorate that not only were the Liberals swept from power, but the Conservatives also took a major loss, leaving the last man standing, the quiet and boring former Premier of Saskatchewan, Walter Bechmann.

Following the election night carnage as the Liberals went from holding a long-standing majority to six seats, barely half what would be needed for official party recognition on the federal level. Still weakened from their collapse under Kim Campbell in 1993, the Conservatives held only 20 seats. And with the effective merger of the New Democratic Party into the DUP, the official opposition party was the separatist Bloc Québécois. Given the DUP’s strong anti-French stances it has made for ugly fighting in Parliament, but with little effect on Prime Minister Bechmann’s policy goals.

Most observers speculate that after years of Liberal rule with virtually no other option, the image of the effective, hard working, non-flaboyant man from Saskatchewan has endeared Beckman with the Canadian people. While the more conspiracy minded suggest that the inability of the other national parties to organize may be linked to more sinister interference. The Bloc, always willing to scream about government and DUP misdoings, points to the Canadian Federal Security Service, which had long been battling Quebec nationalists and had closely allied themselves with the DUP on its rise.

The French Question

Conflict between Canada’s Francophone minority and Anglophone majority is hardly new, though the extensive efforts made on behalf of the federal government to help preserve the French language and French Canadian culture is relatively recent. Unfortunately equalizing language and granting Quebec some special status has not stopped an upswing in separatist activity, violent and non-violent. The first eruption of what have been several decades of sustained violence began on October 5, 1970 with a string of bombings, kidnappings, bank robberies, and attempted assassinations, all the work of a Marxist-Leninist group, Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ).

Like many similar groups, West Germany’s Red Army Faction, Italy’s Red Brigade, and the American Weather Underground, the FLQ was made up primarily of middle class born again radicals who would not hesitate to attack the class structure as much as the Anglos. Two weeks into the emergency Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau ordered the Army into the streets to enforce Martial Law in Quebec under the controversial War Measures Act. The overwhelming force, mass arrest of those associated with the FLQ (and their families), and the stretching of the organization’s resources beyond what they could handle for all practical purposes destroyed the organization. The deaths of some of the detainees in the custody of the army and RCMP, and the disappearance of others have left a sinister note over the ending of the emergency. Rumors still surface decades later of prominent Quebecois, made to disappear during the period, in the custody of particularly vindictive elements of the government.

The next wave of extreme violence occurred in 1990 when a new group, calling itself the Armée de Libération du Québec (ALQ) and trading on the reputation of their similarly named predecessor began targeting Java Works, a nation wide specialty coffee chain which like many corporations continued to use its English name in Quebec. Well-dressed young people, of an age to be university students, used automatic rifles to commit mass murder of the patrons and employees at one Saint-Georges shop. Similar attacks followed within days, with brutality and efficiency associated to a particular terrorist leader soon identified as Amanda Legardeur, the daughter of an upper class Montreal family.

Though relatively brief, the spree lasted just over a month; the brutality displayed cleared the fence sitters out of the way, leaving only those who would clearly choose between a sovereign and independent Quebec, and a united Canada. That was of course, what Legardeur had intended, and the cultivation of a young woman who looked similar to her so that she could shoot her in the head to fake her own death was a small price to pay in her game. It took CSIS and FSS nearly a decade to agree that she was indeed, still alive, though once they had, her legend grew even more. Today she is the most wanted woman in Canada, believed to be not only armed, but possessing the organization and leadership skills to make her a one person national security threat.

In response to the perceived failure of the moderates, the increasing violence of the extreme separatists, and what many particularly among the rank and file of the ruling DUP see as excessive allowances to the French, there has been a backlash. With only the exception of the United States, the primary focus of the Canadian Federal Security Service—the most ruthless, and effective of the competing agencies—has been what is internally called “the French Question.” Some wonder though, if repressive and often highly illegal methods will only divide the country more, just as they did for the British in Northern Ireland.

The federal government believes—not without reason—that the violent separatists are being backed by east bloc communist countries that would use an independent Quebec as a base of operations on the Americans doorstep. Unwilling to see the country torn apart, or to be used by either superpower in cynical games of brinksmanship, the Canadian government has begun to look at solving all their problems on a larger scale.

American Relations

The Canadian government, and to some extent the Canadian people, have understood the true form of the American government longer than any other county in the world. For them it is like having a window on the great superpower, seeing more up close in American news and American television—not to mention in frequent visits to the states to avoid high Canadian taxes—than anyone in the United Kingdom or the Europe ever does. And certainly more than anyone ever gets to see of the Americans’ rival the Soviet Union.

Over the years though, at least from the American side, this familiarity has bread contempt. Washington sees Ottawa, and more importantly in the Americans case, the Pentagon sees them as a joke. The quaint socialist country to the north whose military is more focused on tracking down stray penguins and who police and intelligence services can be characterized by The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show’s Dudley Do-Right. The fact that there are no penguins in Canada has not entered into the American’s calculations. The American public’s view is not much more nuanced, seeing their continental neighbors as unerringly polite, and with the firm belief that every Canadian citizen can kill, skin, and gut a grizzly bear with their bare hands.

The view south from Ottawa is quite a bit more nuanced, though the Canadians have learned a hard lesson about the sometimes friendly sometimes vicious pit-bull they have been planted next to. The the view has been common enough going all the way back to repeated American invasions during the War of 1812, it came to a nasty point when the indifference which the American military seemed to treat the accidental nuking of their country. As one Strategic Air Command general at the Ungava Board of Inquiry commented to another when he did not know that his microphone was on, “All they have are trees and rocks up there, what’s the big deal?”

A firm belief has developed, especially among the security and intelligence communities (with the notable exception of CSIS, who have a close working relationship with the Americans) that there is indeed a major military and security threat to Canada, the Canadian way of life, and even the lives of every Canadian citizen.

Their neighbors to the south.

A Fair Deal, an Even Playing Field, a Slippery Slop—The Canadian Psychic Experiments

Like many countries around the world the Canadians are intimately familiar with the uses and abuses of the paranormal within the intelligence community. As a commonwealth country they have long been familiar with the sorcerer viziers that have advised the crown for centuries. However as with many things that come with the British heritage, the mother country has far more use of the community than the former imperial possessions.

The ruling DUP have an innate distrust of sorcerers owing to a distrust of anything supernatural that gives one man an advantage over another. It is a political, philosophical, and religious distrust that has placed the country’s small sorcerer community at odds with the government… though not yet at war. The leading wizard in the country is the queen’s representative, and a master of the mysteries of the mind, Karen Clarke. She has focused primarily on checking the power of Prime Minister Beckmann and the agenda that most people have not yet discovered behind the party and by extension the government’s actions.

The difficulties between the sorcerers and the government are nothing though, in comparison to the outright war that has been declared on psychic talent within the Dominion. The idea that among the citizens exist a population—small as it may be—who can commit the worst violations on a person’s mind and body without any control by rule or law offends the prairie socialists very nature. In the view of the party psychics are to be monitored, controlled, and eventually eradicated from society as a threat to the rest of the human race.

Most within the power structure would chose to do this through “curing” the afflicted, many of whom themselves would gladly submit at first for any chance to lead a normal life. The main arm of this goal, like so many other things within the party’s plans, has been the Canadian Federal Security Service (FSS). The service itself though, has mixed feelings about the mission. Those that know the ultimate goal also know that enemy countries, particularly the communist nations, have been using their own psychics against Canada. The cleverest among them have begun to play both sides against the middle.

Section C of the FSS has been responsible for the beginnings of an extensive tracking network that will eventually use the DNA markers to identify psychics. Or so they hope. One problem they have discovered—and one that the Soviets have been independently finding at the same time—is that the genes that control psychic gifts are not in the same place for each subset of gifts. The genetic code that turns on a telepath’s ability to read minds is not the same gene that allows a remote viewer to see beyond his body or a pyrokinetic’s ability to set the world ablaze. Complicating matters even farther, some suspect that multiple genes can trigger psychic powers.

In addition to the genetic studies, extensive drug trials have been carried out in an attempt to dampen or control psychics so that they can be returned to society and not imprisoned for life. Unfortunately, as the Americans discovered almost half a century before, psychoactive drugs are themselves a tricky business. It is difficult to determine outside of the subject’s self-reporting if the drug has dampened the powers. The only way of independently determining any drugs affects has been testing on pyrokinetics and telekinetics, whose powers manifest physically. This can be very dangerous, as many test subjects react badly to the conditions within Section C’s hospitals. If not outright killed by the psychics (which usually results in the death of the psychic), the staff often report frightening and wild displays of power as the scared and often mentally ill telekinetic or pyrokinetic looses the concentration and control needed to keep their world together.

As of now, there is no effective drug therapy to control psychic talent.

Those Who Serve

A relative few Canadian psychics are employed by the FSS to battle those of other nations in order not to leave the country vulnerable to attack. This was made abundantly clear during the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics when several east bloc psychics were brought into the country in order to give their athletes an edge in the medal count. The scheme was discovered when a West German coach who had escaped the East recognized a Stasi colonel who had tortured his brother to death among the East German Olympic Committee’s figure skating staff. After a confrontation the night before the figure skating long program, both the West German coach and the East German psychic were expelled from the country.

Unlike the Americans, who rarely use government psychics and have left the practice entirely to corporations and other private enterprises, and the Soviets who have fostered a system of the widespread utilization of psychics, the Canadians keep their mental attack dogs on a very short leash. Each psychic has a strong willed normal agent, known within the community as a Controller (telepaths often have two to prevent one from falling under the spell of their charge). This officer is responsible for all operations that the psychic is used in, and in the field has the authority to summarily eliminate any that become impossible to control. As could be expected, a physical psychic (telekinetics and pyrokinetics) or a mental specialist like a telepath is much harder to control than even the most powerful remote viewer or precognitive.

The Personalities Involved

Her Excellency, the Right Honourable Karen Mendelsen-Clarke, Governor General and Commander-in-Chief in and over Canada. A Vancouver born academic with impeccable credentials, her recent appointment by the Queen as her representative in Canada caused a near constitutional crisis as it went against the advise of Prime Minister Bechmann. The Queen’s growing concern about Bechmann’s politics and leadership of the country led her to appoint Clarke, a Cambridge educated sorcerer with a specialization in the powers of the mind. Publicly she is polite and friendly to the PM, but privately she has been hard nosed and difficult, threatening to withhold royal consent from legislation and implying that she might dismiss several of his ministers. In an unprecedented step, she has also formed her own guard battalion for protection after a suspicious car accident nearly took her life. With the traditions of the reactivated Black Watch (Royal Highlanders of Canada), they are seen by the DUP as her private army and viewed with great suspicion. She is divorced with no children.

The Right Honorable Walter Bechmann, Prime Minister of Canada, Leader of the Dominion Unity Party. A long time provincial politician in his home province of Saskatchewan, he served for nearly a decade as a Progressive Conservative backbencher in the provincial assembly before recognizing a wave of political change in time to ride it to the top. He ended up sweeping the Provincial Party elections when the DUP was first created and then surprisingly took the DUP to the top spot in Saskatchewan. Eventually the Party attained national membership, and gained power in other provinces. After several years as the Premier of Saskatchewan, he retired from politics briefly, before coming back for Federal politics to become the national leader for the party. Often seen in the press as bland and dense, he is actually an astute observer and can be very charismatic when he wants to be. And he usually wants to be charismatic in private. During Question Period many a young MP have learned to underestimate the old man at their peril. He has a wife and three daughters.

David Cherier, Premier ministre du Québec, leader of the Parti Libéral du Québec. A lawyer by trade, David Cherier specialized in defending those swept up in various federal anti-terrorism sweeps. He was first elected to Parliament as Progressive Conservative before returning to Quebec to become the Minister for Natural Resources. Hard work, competence and charm brought him to the head of his party and with the PLQ’s win in elections to the position of Quebec Premier. Though not a separatist himself, he is a strong Quebec nationalist, and has fought vigorously against the policies of Walter Bechman in his attempt to roll back concessions made to Quebec. His sometimes ally in this has been Governor General Clarke, but she has also sided with the prime minister when it suited her. He is generally considered a good man, if relatively unsophisticated when matching wits with the PM. There have been three assassination attempts on Cherier’s life, one when he was Minister for Natural Resources, presumably by separatist groups such as the ALQ, though they have not claimed responsibility.

0 notes

Text

How Gaul ‘Barbarians’ Influenced Ancient Roman Religion

The continental neighbors of the Romans, the Gauls were considered barbaric entities which the Republic and Empire attempted to colonize multiple times. Caesar’s numerous conquests on the mainland allowed for constant military encampment within Gaul, resulting in a need to bring the Gallic religion under some kind of Roman control. This culminated in what is now known as the Gallo-Roman religion, an amalgamation of the two faiths.

Caesar’s Gallic Wars

Stretching through modern day France and Spain, the Romans came into contact with the Gauls consistently throughout their history, most prominently when Julius Caesar made it his mission to dominate the tribes on the coast of the English Channel. In doing so, he paved the way for two marches on the British Isles, most notably his infamous "crossing the Rubicon," though both times he failed to conquer the Insular Gauls.

‘Vercingetorix Throws Down His Arms at the Feet of Julius Caesar’ (1899) by Lionel Noel Royer. ( Public Domain ) The painting depicts the surrender of the Gallic chieftain after the Battle of Alesia - 52 BC.

However, Caesar conquered much of Gaul during his Gallic Wars , so the Roman military often made their home in various Gallic territories—both for the battles, and to keep the Roman power in place following their victories. Because of this, it is believed that the Roman soldiers needed a way to worship their own gods and goddesses in this new territory.

Assimilating the Gods of the Gauls

One of the ways in which they accomplished this, also desiring to prevent overwhelming resistance from the native Gauls, was through assimilation, wherein the gods of the Gauls were likened to the Roman gods . This act is known as translation.

It is important to understand that the gods of the Gallic religion were not the same as those of the Romans. The Romans believed, like the Greeks , that their gods were idealized humans—they not only took human shape but also participated in various forms of human interaction and experience. That is to say that they loved, argued, took revenge, etc.

The Gallic gods, on the other hand, were representational deities —manifestations of the natural world. Not anthropomorphic, the springs and rivers and mountains and forests were worshipped as supernatural beings - but did not to take on human form. Worship, therefore, took place at the specific locations, and there were few—if any—specific temples dedicated to these natural forces.

A druid and warriors in Gaul. ( Erica Guilane-Nachez /Adobe Stock)

Gallic art reveals their belief in the gods quite clearly as, before the Romanization of the region, the gods were merely depicted as a consolidation of geometric shapes and stylized forms rather than bodily representations. Epona, for example, the goddess of horses in the Gallic faith, was often represented as a horse by the natives rather than as a woman.

It was only when she was adopted by the Romans, one of the few deities taken from the Gauls and fully translated into the Roman pantheon, that she was depicted as a woman on a horse, riding into battle, alongside the Roman armies. Without the Roman influence, Epona would have remained a metaphor in art rather than a woman.

Epona, a resulting goddess from the Gallo-Roman fusion, was "the sole Celtic divinity ultimately worshipped in Rome itself." ( THIERRY /Adobe Stock)

Gallic Gods Renamed by the Romans

According to one of his written accounts, Caesar's Gallic Wars describes five primary gods of the Gallic religion. Their names, however, were given as those of five Roman gods: Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, Apollo, and Minerva. This was undoubtedly because the Romans associated the Gallic gods with their known Roman gods, believing—in a way—that all other pantheons were merely misnamed versions of their own.

With their legions spread throughout Gaul, and desiring to worship their native gods anyway, it was not all that difficult to associate the two faiths and thus retitle the Gallic deities. Adding a Roman epithet to the Gallic name allowed the two faiths to blend in such a way that the Gauls could still refer to their own gods while venerating those of Rome. This move was then followed by artistic integration, similar to the Roman adoption of Epona.

The Celtic gods soon began to take on human forms, forms similar to the depiction of their Roman counterparts in the empire. There is no known definite iconography that the Gauls had for their gods, so transforming the metaphorical images was not very difficult. Lugh, the god of light, soon came to look like Mercury; the protector Nodens began to hold the sword and helmet of Mars; Sulis became known for armor that looked eerily similar to Minerva's, and so on.

The five "primary" Gallic gods became very Roman in their appearance, thereby allowing the Gauls to continue to worship their deities in a Roman guise. This anthropomorphism was furthered by the Romans coupling the Gallic and Roman gods, creating intercultural relationships to reflect what was happening among the humans. Roman gods were given Gallic wives in the native regions, further cementing the idea in the minds of the Gauls that the Romans were there to stay.

Political Motives for Religious Integration

Though the Gallic-Roman integration was mostly spearheaded by the religious desires of the Roman legions, it is important to understand the ways in which this integration allowed the Romans to expand their empire with little resistance. By associating Roman gods with the native Gallic ones, the Romans were actually quite clever—instead of making the Gauls feel as though their religion was being forcibly removed, the Romans chose to show their "take-over" as a unification of ideas instead.

A votive offering to an unnamed Gallo-Roman deity. (Siren-Com/ CC BY SA 3.0 )

This attempt was undoubtedly intended to help prevent rebellions, as threatening the belief system of another culture can have drastic effects, and the Gauls were already seeing a shift in their political system with the coming of Rome.

Integrating religions allowed for an assumed level of respect between cultures (whether or not it was truly meant) and it created an idea that the gods wanted such an action to occur, as they themselves were merging with one another. Art was the fiercest tool the Romans had at their disposal when the Gallic Wars were won, and they did a very good job of merging the two faiths to show a false equality among cultures.

Top Image: Gallo-Roman mosaic on a wall in Saint Romain en Gal, France . The Gallo-Roman religion is an amalgamation of the Gaul and Roman faiths. Source: Ricochet64 /Adobe Stock

Caesar, Julius. Gallic Wars . trans. W. A. Macdevitt (Wilder Publications: Virginia, 2009.)

Castleden, Rodney. The Element Encyclopedia of the Celts (HarperCollins: United Kingdom, 2012.)

Green, M. Gods of the Celts (Sutton Publishing Limited: United Kingdom, 1986.)

Henig, Martin. A Handbook of Roman Art: A comprehensive survey of all the arts of the Roman world (Cornell University Press: New York, 1983.)

Rodgers, Nigel. Life in Ancient Rome People and Places (Hermes House: London, 2006.)

Salway, Peter. Roman Britain: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2002.)

Scott, Sarah and Jane Webster. Roman Imperialism and Provincial Art (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2003.)

Wolf Gregg, Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge 1998.)

This content was originally published here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seamus Deane, Heroic Styles: The Tradition of an Idea [Field Day Pamphlet, No. 4] (Derry: Field Day 1984).

It would be foolhardy to choose one among the many competing variations [ways of reading - Irish literature and history - Romanticism, Victorianism, Modernism; Idealist, Radical, Liberal] and say that it is true on some specifically historical or literary basis. Such choices are always moral and/or aesthetic [5].

What I propose […] is that there have been for us two dominant ways of reading both our literature and our history. One is “Romantic”, a mode of reading which takes pleasure in the notion that Ireland is a culture enriched by the ambiguity of its relationship to an anachronistic and a modernist present [sic]. The other is a mode of reading which denies the glamour of this ambiguity and seeks to escape from it into a pluralism of the present. The authors who represent these modes most powerfully are Yeats and Joyce respectively. The problem which is rendered insoluble [5] by them is the North. In a basic sense, the crisis we are passing through is stylistic. That is to say, it is a crisis of language - the ways in which we write it and the ways in which we read it. In a culture like ours, ‘tradition’ is too easily taken to be an established reality. We are conscious that it is an invention, a narrative which ingeniously finds a way of connecting a selected series of historical figures or themes in such a way that the pattern or plot reveal to us becomes a conditioning factor in our reading of literary works. (p.5-6.)

A poem like “Ancestral Houses” owed its force to the vitality with [which] it offers a version of Ascendancy history as true in itself. The truth of this historical reconstruction of the Ascendancy is not cancelled by our simply saying No, it was not like that. For its ultimate validity is mythical, not historical. In this case, the mythical element is given prominence by the meditation on the fate of an originary energy which becomes so effective that it transforms nature into civilisation, and is then transformed itself by civilisation into decadence. The poem, then, appears to have a story to tell, and, along with that, an interpretation of the story’s meaning. It operates on the narrative and on the conceptual planes and at the intersection of these it emerges, for many readers, as a poem about the tragic nature of human existence itself. Yeats’s life, through the mediations of history and myth, becomes an embodiment of essential existence.

The trouble with such a reading is the assumption that this or any other literary work can arrive at a moment in which it takes leave of history or myth (which are liable to idiosyncratic interpretation) and becomes meaningful only as an aspect of the ‘human condition’. This is, of course, a characteristic determination of humanist readings of literature which hold to the ideological conviction that literature, in its highest forms, is non-ideological. It would be perfectly appropriate, within this particular frame, to take a poem by Pearse - say, “The Rebel” - and to read it in the light of a story - the Republican tradition from Tone, the Celtic tradition from Cuchulainn, the Christian tradition from Colmcille - and then reread the story as an expression of the moral supremacy of martyrdom over oppression. But as a poem, it would be regarded as inferior to that of Yeats. Yeats, stimulated by the moribund state of the [6] Ascendancy tradition, resolves, on the level of literature, a crisis which, for him, cannot be resolved socially or politically. In Pearse’s case, the poem is no more than an adjunct to political action. The revolutionary tradition he represents is not broken by oppression but renewed by it. His symbols survive outside the poem, in the Cuchulainn statue, in the reconstituted GPO, in the military behaviour and rhetoric of the IRA. Yeats’s symbols have disappeared, the destruction of Coole Park being the most notable, although even in their disappearance one can discover reinforcement for the tragic condition embodied in the poem. The unavoidable fact about both poems is that they continue to belong to history and to myth; they are part of the symbolic procedures which characterise their culture. Yet, to the extent that we prefer one as literature to the other, we find ourselves inclined to dispossess it of history, to concede to it an autonomy which is finally defensible only on the grounds of style.

The consideration of style is a thorny problem. In Irish writing, it is particularly so. When the language is English, Irish writing is dominated by the notion of vitality restored, of the centre energised by the periphery, the urban by the rural, the cosmopolitan by the provincial, the decadent by the natural. This is one of the liberating effects of nationalism, a means of restoring dignity and power to what had been humiliated and suppressed. This is the idea which underlies all our formulations of tradition. Its development is confined to two variations. The first we may call the variation of adherence, the second of separation. In the first, the restoration of native energy to the English language is seen as a specifically Irish contribution to a shared heritage. Standard English, as a form of language or as a form of literature, is rescued from its exclusiveness by being compelled to incorporate into itself what had previously been regarded as a delinquent dialect. It is the Irish contribution, in literary terms, to the treasury of English verse and prose. Cultural nationalism is thus transformed into a species of literary unionism. Sir Samuel Ferguson is the most explicit supporter of this variation, although, from Edgeworth to Yeats, it remains a tacit assumption. The story of the spiritual heroics of a fading class - the Ascendancy - in the face of a transformed Catholic ‘nation’ - was rewritten in a variety of ways in literature - as the story of the pagan Fianna replaced by a pallid Christianity, of young love replaced by old age (Deirdre, Oisin), of aristocracy supplanted by mob-democracy. The fertility of these rewritings is all the more remarkable in that they were recruitments by the fading class of the myths of renovation which belonged to their opponents. Irish culture became the new property of those who were losing their grip on [7] Irish land. The effect of these rewritings was to transfer the blame for the drastic condition of the country from the Ascendancy to the Catholic middle classes or to their English counterparts. It was in essence a strategic retreat from political to cultural supremacy. From Lecky to Yeats and forward to F. S. L. Lyons we witness the conversion of Irish history into a tragic theatre in which the great Anglo-Irish protagonists — Swift, Burke, Parnell — are destroyed in their heroic attempts to unite culture of intellect with the emotion of multitude, or in political terms, constitutional politics with the forces of revolution. The triumph of the forces of revolution is glossed in all cases as the success of a philistine modernism over a rich and integrated organic culture. Yeats’s promiscuity in his courtship of heroic figures — Cuchulainn, John O’Leary, Parnell, the 1916 leaders, Synge, Mussolini, Kevin O’Higgins, General O’Duffy— is an understandable form of anxiety in one who sought to find in a single figure the capacity to give reality to a spiritual leadership for which (as he consistently admitted) the conditions had already disappeared. Such figures could only operate as symbols. Their significance lay in their disdain for the provincial, squalid aspects of a mob culture which is the Yeatsian version of the other face of Irish nationalism. It could provide him culturally with a language of renovation, but it provided neither art nor civilisation. That had come, politically, from the connection between England and Ireland.

All the important Irish Protestant writers of the nineteenth century had, as the ideological centre of their work, a commitment to a minority or subversive attitude which was much less revolutionary than it appeared to be. Edgeworth’s critique of landlordism was counterbalanced by her sponsorship of utilitarianism and “British manufacturers”; Maturin and Le Fanu took the sting out of Gothicism by allying it with an ethic of aristocratic loneliness; Shaw and Wilde denied the subversive force of their proto-socialism by expressing it as cosmopolitan wit, the recourse of the social or intellectual dandy who makes [8] such a fetish of taking nothing seriously that he ceases to be taken seriously himself. Finally, Yeats’s preoccupation with the occult, and Synge’s with the lost language of Ireland are both minority positions which have, as part of their project, the revival of worn social forms, not their overthrow. The disaffection inherent in these positions is typical of the Anglo-Irish criticism of the failure of English civilisation in Ireland, but it is articulated for an English audience which learned to regard all these adversarial positions as essentially picturesque manifestations of the Irish sensibility. In the same way, the Irish mode of English was regarded as picturesque too and when both language and ideology are rendered harmless by this view of them, the writer is liable to become a popular success. Somerville and Ross showed how to take the middle-class seriousness out of Edgeworth’s world and make it endearingly quaint. But all nineteenth-century Irish writing exploits the connection between the picturesque and the popular. In its comic vein, it produces The Shaughran and Experiences of an Irish R.M.; in its Gothic vein, Melmoth the Wanderer, Uncle Silas and Dracula; in its mandarin vein, the plays of Wilde and the poetry of the young Yeats. The division between that which is picturesque and that which is useful did not pass unobserved by Yeats. He made the great realignment of the minority stance with the pursuit of perfection in art. He gave the picturesque something more than respectability. He gave it the mysteriousness of the esoteric and in doing so committed Irish writing to the idea of an art which, while belonging to “high” culture, would not have, on the one hand, the asphyxiating decadence of its English or French counterparts and, on the other hand, would have within it the energies of a community which had not yet been reduced to a public. An idea of art opposed to the idea of utility, an idea of an audience opposed to the idea of popularity, an idea of the peripheral becoming the central culture - in these three ideas Yeats provided Irish writing with a programme for action. But whatever its connection with Irish nationalism, it was not, finally, a programme of separation from the English tradition. His continued adherence to it led him to define the central Irish attitude as one of self-hatred. In his extraordinary “A General Introduction for my Work” (1937), he wrote: