#girmit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

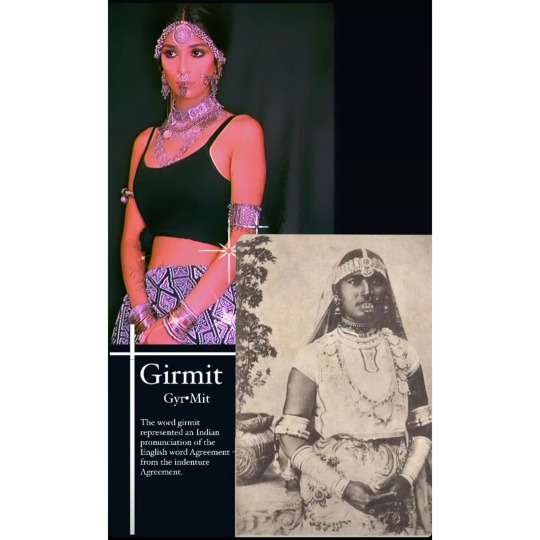

'The word girmit represented an Indian pronunciation of the English word "agreement" - from the indenture "agreement" of the British Government with labourers from the Indian subcontinent.

The agreements specified the workers' length of stay in foreign parts and the conditions attached to their return to the British Raj.'

From Girmitiyas on Wikipedia

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girmitiyas

#girmit#agreement#words#word#language#agreements#workers#meanings#meaning#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Better than bhel puri: Girmit or mandakki

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Post coup trauma – thirty-seven years on.

May 14th 1879, the Leonidas landed on Fiji’s shores with the first ‘batch’ of Indian indentured labourers, brought to toil on sugar plantations. After the Leonidas, 87 ships brought over 60, 000 indentured labourers to Fiji, whose children would become the first generation of an ethnic group known as Indo – Fijians.

May 14th 1987, Fiji: Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka was responsible for a racially fuelled coup in Fiji. After which many Indo Fijians including my parents emigrated to New Zealand.

In 2022, Sitiveni Rabuka was elected as the Prime Minister of Fiji. My mother felt uneasy about this. The trauma and undercurrents of 1987 has never gone away.

A lifetime has gone by since 1987, perhaps it is time to think about how past decisions now affect the diaspora?

Above: Attendees at the May 14th ‘Fiji Girmit Remembrance Day,’ Auckland. [Original image by Aaisha Khan]

vimeo

Audio DUR: 0.09 seconds.

Contact details of interviewee: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Ministry committed to representation of women - FBC News

The Ministry of Public Enterprises aims to promote the representation of women at ... Suva City comes to life with Girmit float procession ...

0 notes

Quote

Between 1838 and 1917, over one million Indian immigrants were taken from villages of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu, for indentured labourership. These included Hindus across castes and Muslims as well. They were often called Girmityas after the term, girmit, which was the Indian way of pronouncing the word, agreement. More pejoratively, they were called Coolies. The immigrants, however, often did not know that they were migrating to a different country. “Some thought they were leaving Calcutta and going to Madras or Mauritius,” said Vinay Harrichan, 24, host and producer of The Cutlass podcast, which focuses on the history and experiences of the Indo-Caribbean community. “They thought they would be able to bring back riches and gold for their families and that they were going away for only a few years,” he adds. This deception was intentionally fueled by the recruiters who brought these villagers to Calcutta. Some were even kidnapped and forced to go against their will.

Garima Garg, ‘A Voyage Less Ordinary’, India/भारत

#Garima Garg#India/भारत#India#Indian immigrants#indentured labour#Uttar Pradesh#Bihar#Tamil Nadu#Hindus#Muslims#Girmityas#girmit#Coolies#Calcutta#Madras#Mauritius#Vinay Harrichan#The Cutlass#Indo-Caribbean community#kindap

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

the story of Mahadeo:

'I was sixteen when I came to Fiji. I was unmarried and an orphan; my parents had died in some epidemic. In India I had made a living out of grazing cattle and getting food and a place to stay but no money in. return. I lived a life which was not one of great hardship except when there was sickness about. I used to get sores but there were no doctors there to provide treatment.

I came to Fiji because I was lured. I met a man who asked me if I was looking for work. I answered in the affirmative and he told me that I would have to go by train from place to place carting and unloading goods. When I was offered the job I did not go back to tell anybody, I accepted it. I had nothing, neither money nor kinsmen.

I travelled a day and a night before arriving in Calcutta. There were a lot of people at the depot there; men, women and even children. I stayed there for a week and was examined medically. All one did at the depot was to eat and stay in one’s own place. Blankets were provided for sleeping. There persons of all castes ate and mixed together, unlike in the village where people of different castes ate separately. I was told the distance from Calcutta to Fiji. wanted work and I would have come had I been accurately informed that it was a month’s journey by sea. I was also told that I would get twelve annasa day.

There were around 200 migrants on my ship. I had quite a good trip and did not bet sick. On board we were required to scrub the ship each day. I was busy for about half an hour performing this chore. Some people sang and danced.

Once we reached Fiji I was sent to Cuvu via Lautoka. In Cuvu we were given our work tools. I was set the task of cutting grass, a chain long and a chain wide. In this work of weeding we often pulled out the grass and our hand- used to get cut. If we did not finish our task our money was not paid because we had not completed our work. We also had to dig drains: for this purpose we were paired off, one new and one old hand. The old hand with me refused to show me how to dig drains. The sardar told me that I had made a mess. My shipmate, who made a similar blunder, was given a thrashing by the overseer.

Sardars used to give the task. If we did not complete them thesardars used to give us a rough time. If one could not do one ‘s work, then one got a beating. I was beaten by sardars but never was I able to beat up one of them. I do not recollect anyone on my estate hitting a sardar or an overseer.

There was a South Indian with us. He used to do a lot of singing and dancing but he was not able to work and he used to get a terrible beating from the overseer. So he took off into the bush and hanged himself. I know of two persons who committed suicide because they could not do the work and were regularly beaten by the overseer.

The sardars used to wake us up at 2am. At 3am we had to line up and go to our task. One had to fill up one’s billy-can with food and pick up one’s tools and then move out. They gave us a very rough time in those days.

We used to think of home. But what was the purpose of it. Home was so far away and if we wanted to go we could not because we had no money. I saved no money during my indenture. Besides, in any case I had nobody in India, so for me there was no place or person to return to.

I once stayed in hospital because I had a sore on my leg. I was well treated there. The doctor there suffered hardship sometimes. He often used his own money to feed people.

During week-ends I used to visit time-expired migrants living in the neighbourhood. There were a lot of Indians nearby who were devoted cultivators. And I used to spend a lot of time at my friend’s place. I used to spend all day there and then return in the afternoon to my room. The ‘free’ were very good to us; they used to give us milk, yoghurt and food, in return we used to help these people a little with their work.

When we first saw Fijians we called them junglees. Some of the Indian indentured labourers from the early times used to regard them as such.

We used to get a holiday for Holi but not for Diwali. Those who knew how to read and write sometimes taught us to do likewise.

Hindus and Muslims got on well. They did not fight. There was no conflict over Muslims slaughtering cows. Each person ate his own food. We went to each other’s place and were not concerned about any religious taboos.

Once I was urinating outside the toilet, the overseer,, apparently, caught me in the act through his binoculars from his bungalow. He came down to the stables and called me out. Then he locked me in a room and asked why I had urinated outside and not in the toilet; he then beat me by kicking me all over the place. This is how we suffered during the indenture period.'

http://girmit.org/the-girmitiya-stories/mahadeo/

more about Fiji Indian Indenture: TheIndentureHistory (ig)

#indentured labour#indentured servitude#indentured servant#indentured#indenture#girmit#fiji girmit#girmityas#girmitya#fiji#fiji indian#fijian indian#indo fijian#coolie#coolies#india

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Being a Bengali I've had Jhaalmuri or puffed rice with spices as one of our staple evening snacks in Calcutta. Yesterday, I discovered something very similar. The word is 'Girmit'. A dish from North Karnataka consisting of puffed rice with spices along with a Mirchi Bhajji that's fried chilli. Different place different names but same concept same taste. Loved it! ♥️ . . . . . . . . #girmit #puffedrice #spices #karnataka #karnatakatourism #karnataka_ig #bangalore #northkarnataka #flavours #flavor #food #discovery #bangalore_insta #bangaloregram #bangaloreinstagrammers #bengalurudiaries #bengaluru_nodi #bengaluru_diaries #karnatakafood #tastebuds #basavanagudi #fooddiaries #karnatakadiaries #culture #Calcutta #Kolkata #chilli #concept #names #places #taste (at Basavanagudi) https://www.instagram.com/p/BncZEASni5e/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=ya2c1dl5t4td

#girmit#puffedrice#spices#karnataka#karnatakatourism#karnataka_ig#bangalore#northkarnataka#flavours#flavor#food#discovery#bangalore_insta#bangaloregram#bangaloreinstagrammers#bengalurudiaries#bengaluru_nodi#bengaluru_diaries#karnatakafood#tastebuds#basavanagudi#fooddiaries#karnatakadiaries#culture#calcutta#kolkata#chilli#concept#names#places

0 notes

Photo

GIRMIT- A POPULAR SNACK OF NORTH KARNATAKA https://ift.tt/RftlmP9

0 notes

Text

everytime I see Hindus in America being purely romantic about their religious community as being like “immigrant” and hence “innocent” it’s like...the temple my parents went to was built under the financial auspices of fracking money. smdh and now literal girmit indentured labor of Dalits (I don’t think it’s been on this scale before). fucking wake up.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Making Journey part 3. Key Information

Key points and information for Girmitiya Collage

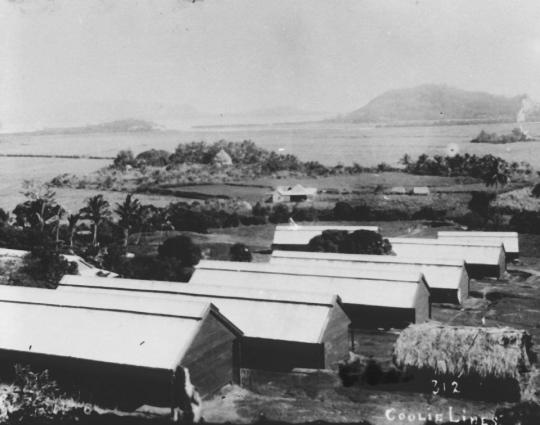

‘The Coolies lived in tin shacks called limes, built-in long rows beside the plantation. It housed about 3 individual men or one man and his entire family’ (Coolies).

‘Many diseases such as cholera, malaria and typhoid wiped out hundreds of Indians’ (Coolies).

60,965 Indians were transported to British Fiji from a period of 1879 til 1920, 41 years (History).

‘1879, The ship set sail in Calcutta on March 03 and arrived in Fiji on May 14, with 373 male and 149 female labourers’ (History).

1882, Colonial Sugar Refining (CSR) company of Australia sets up its first sugar mill in Nausori. Second migrant ship arrives in Fiji’ (History).

The indenture was a traumatic experience for all those helpless Indians, living in confined spaces with people from different religions dialects from India who could understand each other.

Keywords

Girmit. (agreement)

Girmitya.

Nausori (Fijian City).

Calcutta (Indian city).

Colonial Sugar Refining (CSR).

Black birding (using deception or kidnapping people to work as slaves labourers).

Coolies.

Indenture.

Indentured labourers.

Image source: http://girmitiya.girmit.org/new/index.php/rare-images/.

Works Cited:

Coolies: How British Reinvented Slavery. BBC Four Corners Documentary, 2002

History. New Girmit.org,http://girmitiya.girmit.org/new/index.php/history/. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Rare Images. New Girmit.org, http://girmitiya.girmit.org/new/index.php/rare-images/. Accessed 4 May 2021.

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Over the last six weeks, they have crept into our consciousness. They have inspired pity, anger, hectoring and indifference. That they lived all around us was a detail we were barely conscious of before the nation-wide lockdown was put into place. They cleaned our homes and washed our cars, served us at restaurants and eateries, sweated and slaved away in the many small and big factories and workshops that one finds all over the urban sprawls that our cities have become. Many of us were similar to them in that we too do not hail from the cities that we now live in. We, or someone in our family, had moved there to seek employment or start a business and then stayed put or ‘settled down’ as we, the well-heeled, put it. We then grew roots, purchased an apartment or built a home, sometimes two, and came to feel that we ‘belonged’. ‘They’, on the other hand, were birds of passage who did not put down roots or try to belong. Sure enough, when the lockdown was announced, and then later, extended, they sought to ‘return’ home. The stories of their journeys which have been documented in the news and on social media have been gut-wrenching. Walking or cycling for days on end, on little food and water, families and meagre possessions in tow, sometimes collapsing and dying with their destination in sight, mowed down by trucks and run over by trains, the migrants have been the lockdown’s most unforeseen casualty. A century-and-a-half ago, many Indians — indentured labourers all — made similar journeys in cattle-like conditions on steamships, hoping to find paradise in a distant land where they would have sufficient food, perhaps a plot of land and enough money to tide them through rainy days. Most ended up being cheated and denied a fair shot at life. The journeys of migrants during the lockdown mirrors those journeys across the seas. One was the shame of the British Empire, which had set out to ‘civilise’ the ‘natives’ but ended up enslaving many of them. The current dispensation has shamed the citizens of the Republic of India and the hallowed Constitution, which the citizens gave unto themselves. The system of indentured labour (a ‘second slavery’ as many scholars have rightly termed it) originated in the 1830s when slavery had run its course in most of Europe and the larger public had expressed their outrage at the persistence of such an exploitative system. The destinations for indentured labourers were the Caribbean islands, Mauritius, Africa (Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa), South America (British Guyana and Suriname), Fiji and Malaya. This system sought to legitimise itself on the back of a contract, unlike slavery, which treated human beings as commodities. That the contract specified exploitative terms — poor wages, limited or no leave, loopholes in the clauses concerning release from contract etc — was given little consideration, since the parties were entering into it ‘willingly’. But given that those who assented to this contract were unlettered men and women, mostly from India and China who did not understand the contract’s fine print, was a detail that was conveniently swept under the rug. A second slavery was thus put into practice, and in 1834, the first group of indentured labourers was shipped to Mauritius. To find workers willing to under such contracts (or ‘girmit’ – a homonym for ‘agreement’), a recruiter (‘arkati’) fanned out into India’s poorest districts painting a pretty picture of their work destination. For a desperate populace on the verge of starvation, it was a chance worth taking. Then came the process of explaining to the workers the terms of their contract — a shambolic process. Often, groups were brought in front of a magistrate who inquired if they had understood the contract, without bothering to inquire further. Coached to say ‘yes’, almost all labourers assented and placed their thumb impressions on a sheet of paper. Few knew what they were getting into. The ordeal then began. Before the advent of the railways and its penetration into the Indian heartland, labourers walked from their villages in present-day Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to Calcutta (Kolkata), where a ship awaited them. This first leg of the journey took 30 to 40 days, almost entirely on foot. Journeys from the districts of present-day Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu to Madras (Chennai) were shorter, but grueling nonetheless. Sometimes, if there were no ships ready to sail, migrants waited at the emigration depot for up to three months housed in less than favourable conditions. These potential emigrants were kept under close watch and not allowed the free run of the city. Desertion upon hearing horror tales of the ‘promised land’ was a possibility, as also the chance that they would contract contagious diseases, thereby laying waste the efforts of the ‘arkati’. Once a ship was available, a medical examination followed, and then hundreds of labourers boarded the ship. In the early years, wooden sailing vessels of teak were used. Conditions on the ships were similar to those on slave ships. Totaram Sanadhya, who spent years in Fiji, writes in Fiji Dveep mein Mere Ikkis Varsh (My Twenty-one Years in Fiji) of the cramped conditions in the ship – each person had ‘a space one and a half feet wide and six feet long’. Four ‘dog biscuits’ and ‘one-sixteenth of a pound of sugar’ (about 150 grams) were handed out on boarding, a ‘welcome package’ of sorts. The ship then sailed. On the seas, the labourers were expected to make their own meals with the provisions provided. The toilets too had to be cleaned by them, and refusal to do so resulted in beatings. Two bottles of fresh water were handed out daily. The question of asking for more water in case of need did not exist. One had to make do or suffer silently. Sea journeys ranged from ten to 20 weeks (journeys to Malaya were shorter than ten weeks). An 1878 British Guyana report records that in that year 17 ships arrived. The length of their voyage ranged from 78 to 128 days and the number of passengers varied from 493 to 652. Deaths on the ship were a common occurrence, dysentery, measles and cholera being the frequent causes. Bodies were thrown overboard when deaths took place. Perhaps a religious-minded fellow traveller uttered a short prayer. Otherwise, there was little dignity in death. In 1878, 18 deaths (including 15 children) out of a total of 611 passengers took place on the Hesperides. That the ship had taken 128 days to complete the voyage probably had something to do with it. That same year, 19 deaths took place on the Plassey, which took 92 days to complete the voyage and had embarked with 627 passengers. Still, these conditions were better than the conditions in 1856-57, when the average death rate for Indians travelling to the Caribbean was 17 percent. As many as 11 children were born on the Hesperides during the course of the sea voyage. The Plassey witnessed nine births. To begin with, most of the labourers were men. Only a few women made these journeys. How these women managed the exigencies of childbirth on board a rollicking ship with little water, food and privacy is too terrible to imagine. Given that almost every one of these ships records the deaths of children, it is perhaps fair to assume (since no clear details are available) that many of these deaths were of newborns. More horrors awaited the labourers when they reached their destinations. Poor wages, pathetic living conditions, insufficient food and the dishonouring of the terms of their contracts were commonplace. The indentured system was a system of continuous and prolonged exploitation. When the system came to an end in 1916, close to 1.5 million had made the journey. A significant number had perished en-route or in their new homes. Many stayed back after their contracts ended. A small number returned. Every single one of them had undergone untold suffering. Even as a callous government and an even more callous middle class continue to wallow in utter indifference, a tragedy has unfolded in our times which historians of the future will use to pass judgment on our generation. The indentured system was a telling comment on the tyranny of the white man, the excesses of the Empire and the blood and sweat on which the pretty structures of the West have been built. The current tragedy is our Fall from our fraudulent Garden of Eden.

http://sansaartimes.blogspot.com/2020/05/migrants-across-eras-exodus-caused-by.html

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Our Fijian culture is like none other, our language is our own, created to communicate from one person to another. Our identity is our own, carrying on from generation to generation.'

credit- ig: britts__

#indentured labour#indentured servitude#indentured servant#indenture#indentured#girmit#fiji girmit#girmityas#girmitya#coolie#coolies#fiji#indo fijian#fiji indian#fijian indian#india

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

ಗಿರ್ಮಿಟ್ | Girmit recipe in kannada | Hubli-Dharwad Special Girmit

0 notes

Photo

Want to try girmit a dish which is quite common in North Karnataka then head to Dosa Adda with Coffee swada shop on high tension road Vijaynagar 2nd stage Mysuru in the evening and if you need help to get this place just send me DM I will help you out. #food #girmit #mysuru #dosaadda #chat https://www.instagram.com/p/Bp3Ot_4HMTy/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1lducar3irstn

0 notes

Text

Meri saheli magazine

Meri saheli magazinepublished this article page no 26 all such migrations were covered under the time-bound contract known as girmit act indian emigration act. however the living conditions of these indentured labourers were not better than the slaves. the second wave of migrants ventured out into the neighbouring countries in recent times as professionals artisans traders and factory workers in search of economic opportunities to thailand malaysia singapore indonesia brunei and african countries etc. and the trend still continues. there was a steady outflow of indias semi-skilled and skilled labour in the wake of the oil boom in west asia in the 1970s meri saheli magazine monthly subscription.

0 notes