#garnette cadogan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Überlebender und Zeuge

James Baldwin wäre in diesem Jahr 100 Jahre alt geworden. Der Kulturjournalist René Aguigah erschließt sein Werk so greifbar und lebendig wie niemand zuvor. Sein Porträt ist neben der wachsenden Gesamtausgabe die perfekte Einladung, sich in ein Werk zu vertiefen, dass einem immer wieder den Atem nimmt. Continue reading Überlebender und Zeuge

#Ann Petry#Audre Lorde#Barry Jenkins#Beyonce#Charles Dickens#Daniel Schreiber#Dick Fontaine#Dominique Haensell#Elmar Kraushaar#featured#Fran Ross#Franz Kafka#Garnette Cadogan#Gayl Jones#Henry James#Honoré de Balzac#James Baldwin#Jana Pareigis#Janelle Monáe#Jay Z#Jesmyn Ward#Langston Hughes#Louise Meriwether#Madonna#Malcolm X#Martin Luther King jr.#Medgar Evers#Miriam Mandelkow#Mithu Sanyal#Morrissey

0 notes

Text

Coffee Break Chat 10/16:

youtube

This week’s talk: What no one had told me was that I was the one who would be considered a threat... OURfest • The Radical Left • Decided Voters • Brandishing

Special Guests: Steven Gross - Associate Professor at Temple School of Theater, Film, & Media Arts

"When some university staff members found out what I’d been up to, they warned me to restrict my walking to the places recommended as safe to tourists and the parents of freshmen. They trotted out statistics about New Orleans’s crime rate. But Kingston’s crime rate dwarfed those numbers, and I decided to ignore these well-meant cautions. A city was waiting to be discovered, and I wouldn’t let inconvenient facts get in the way. These American criminals are nothing on Kingston’s, I thought. They’re no real threat to me.

What no one had told me was that I was the one who would be considered a threat." - Garnette Cadogan

Wednesday virtual coffee break with guest speakers, general chat, and social interaction for all of us social animals avoiding interaction.

Join us live on Facebook • YouTube • Twitter • Twitch • Blue Sky • Live Push

Let's meet up for coffee!

0 notes

Quote

Serendipity, a mentor once told me, is a secular way of speaking of grace; it’s unearned favor. Seen theologically, then, walking is an act of faith. Walking is, after all, interrupted falling. We see, we listen, we speak, and we trust that each step we take won’t be our last, but will lead us into a richer understanding of the self and the world.

Garnette Cadogan, “Walking While Black”

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

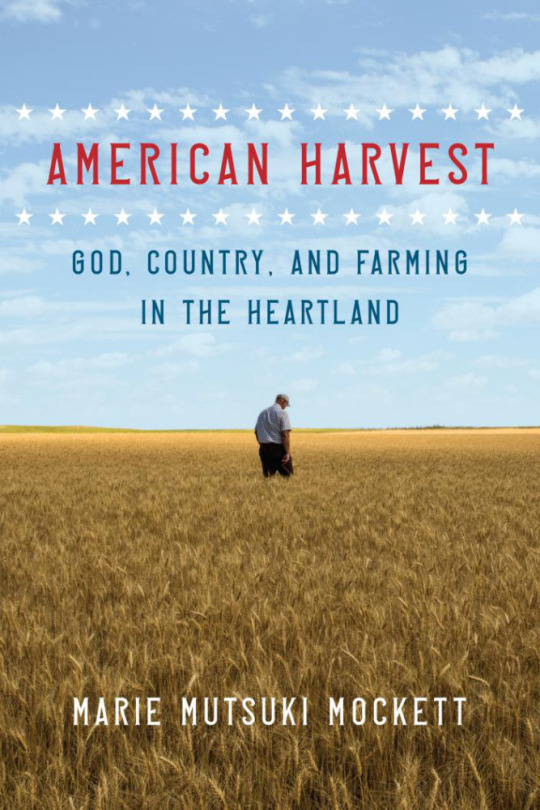

Listening as an act of love: Marie Mutsuki Mockett in conversation

This is an excerpt of a free event for our virtual events series, City Lights LIVE. This event features Marie Mutsuki Mockett in conversation with Garnette Cadogan discussing her new book American Harvest: God, Country, and Farming in the Heartland, published by Graywolf Press. This event was originally broadcast live via Zoom and hosted by our events coordinator Peter Maravelis. You can listen to the entire event on our podcast. You can watch it in full as well on our YouTube channel.

*****

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: You don't see me talking about love or the importance of love very much. Maybe I would have a larger Instagram account if I constantly put up memes about love. I should probably do that.

I consider [American Harvest] to be an investigation of something that I didn't understand and that I thought was important. So I asked questions and wanted to try to answer those questions by talking to people who were very different than I am. To sit with them and find out what their genuine experience in the world is, and then see if I could answer some of the questions that I have.

I did not tell myself, "This is a book about love," or "You must employ love." I also didn't spend a lot of time saying to myself, "This is a book that's going to require you to be brave." I just really was trying to focus on the questions that I had and on my curiosity. I was trying to pinpoint, when I'm in a church, when I'm in a farm, when I'm around a situation that I don't understand, what's actually happening. And that was really what I was trying to do and how I was trying to direct my attention.

Garnette Cadogan: But love comes up a lot in the book. And for you, a lot of it has to do with listening. In many ways, this book is a game of active listening, and listening--as you've shown time and again--is fundamentally an act of love.

You decided to go and follow wheat farmers and move along in their regimens and cycles and rituals, and not only the rituals of labor, but rituals of worship, rituals of companionship, and issues of community. When did you begin to understand what is the real task of listening? Because in the book, time and again, you remind us that there are so many places in which there is this huge gap, or this huge chasm, in our effort to understand each other.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: Well, that is where love comes in. Because that is the only reason why you would spend time listening to people or talking to people. What would be the motivation for trying to be open to others? Why should you be open to others? We don't have to be. So why should one be?

And you're right that things do get reduced down to this question of love. I had always heard that Christianity was the religion of love. And that love was one of the things that was unique about Christ's message. I didn't really grow up with any one religion. Also, my mother was from Japan, so I also grew up always hearing about how for a long time, the word love didn't really exist in Japanese. There really is no way to say “I love you.” Linguists still debate whether or not you can say "I love you" in Japanese and there are ways in which people say it, but it doesn't have the same history, and it doesn't have the same loaded meaning that it does in Western English.

So I was aware from a really early age, because I heard my parents and other people talk about this, that this question of love was very much a part of Western culture and that it originated from Christianity. And I really wondered what does that mean? And if it means anything, is there anything to it? And if there is, what is it? And there's a scene in the book where I talk about my feeling of disappointment that no one had ever purchased me anything from Tiffany, the jewelry store, because if you live in New York City, you're constantly surrounded by Tiffany ads. When you get engaged, you can get a Tiffany box. And then on your birthday, you can get a Tiffany box. And then in the advertisements, the graying husband gives the wife another Tiffany box to appreciate her for all the years that she's been a wife and on and on. I know that that has nothing to do with love. I know that that that's like some advertiser who's taken this notion of love and then turned it into some sort of message with a bunch of images, and it's supposed to make me feel like I want my Tiffany ring (which I've never gotten). That's not love. But is there anything there? And that was definitely something that I wanted to investigate.

I think I started to notice a pattern where I was going to all of these churches in the United States, and I'm not a church going person. And the joke that I tell is that I decided to write American Harvest partly because I wasn't going to have to speak Japanese. I could speak English, which is the language with which I'm most comfortable. But I ended up going to all these churches, and I couldn't understand what anybody was saying. I would leave the church and Eric, who is the lead character, would say, "What do you think?" And I would say, "I have no idea what just happened." And so it took time for me to tune in to what the pastors were saying, and what I came to understand is that there were these Christian churches that emphasized fear, and churches that didn't emphasize fear. And then I started to meet people who believe that God wants them to be afraid and people who are motivated by fear or whose allegiance to the church comes from a place of fear, in contrast to those who said, "You're not supposed to be afraid. That's not the point." That was a huge shift in my ability to understand where I was, who I was talking to, and the kinds of people that I was talking to, and why the history of Christianity mattered in this country.

Garnette Cadogan: So you started this book, because you said, "Oh, I only need one language." And then you ended up going to language training.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: I needed so many different languages! I mean, even this question of land ownership that we're talking about: I feel like that's a whole other language. There are places in the world and moments in history where people didn't own land. It didn't occur to them that they had to own the land themselves. So what's happening when we think we have to? Like with timeshares. I'm really serious. What need is that fulfilling? And you don't need to have a timeshare in Hawaii, where you visit like one week out of the entire year, right? So what need is that fulfilling?

Garnette Cadogan: Rest? Recreation? I’m wondering . . . has the process of living, researching, and writing this book changed you in any way? And if so, how?

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: I mean, absolutely, but it's so hard to talk about. I think that I have a much better and deeper understanding of the history of our country, and a much greater understanding of the role that race plays in our country. A deeper understanding of the tension between rural and urban, and also of our interdependence, which is something I sort of knew, but didn't completely know. And why just kicking out a bunch of states or getting rid of a bunch of people isn't actually an answer to the tension that we've faced. And it's because there's this great interdependence between people. So understanding all of that and realizing how intractable the problem is, oddly, has made me feel calmer about it. Because I realize it isn't as simple as if I just do "X" everything will be fine. I think, when you feel like, "If I just master the steps, if I can just learn this incantation, then everything will be fine," I think when you live that way, it's very frustrating. And I realized the problems are deeper than that. And some of the problems the United States is facing are problems that exist all around the world. I mean the urban rural problems: it's a piece of modernization. It doesn't just affect our country, it affects many countries.

Garnette Cadogan: You know, we've been speaking about land, God, country, Christianity, urbanity, and in this book, a lot of it is packed in through this absolutely wonderful man, Eric, and his family. Part of what makes it compelling and illuminating is we get a chance to understand so much through this wonderful, generous, and beautiful man, Eric. For those who haven't read it yet, tell us about Eric, and why Eric was so crucial to understanding in so much of what you understood, and also some of the changes that you went through.

Marie Mutsuki Mockett: He's a Christian from Pennsylvania. He’s a white man who’s never been to college, but has a genuine intellectual curiosity, although not immediately apparent in a way that would register to us. Because we're at an event that's hosted by bookstore. So when we think of intellectual curiosity, probably the first thing that any of us would do would be to reach for a book, right? That's not what he would do. He wouldn't reach for a book, he would find someone to talk to. He's a person who is very much about the lived experience. But he was very open to asking questions and trying to understand other people's experiences and how the world works, and he was very concerned.

He was the person who told me in early 2016 that he thought that Trump would probably win, when none of us thought that this was possible. And he said this is because we don't understand each other at all. And he's a very open-hearted, very generous person. And you see him change over the course of the book.

He called me the other day. He said, "I've been hearing a lot about violence against Asian Americans." He's met a couple of my friends. He wanted to know, "Are they all right?" And then he said, "I just want you to know that we talk about racial justice all the time in church," because of course, that's the way that he processes life's difficult questions: through church. And I was kind of moved by that, because one of the points that American Harvest makes is that these difficult questions don't get talked about in church. And he said, "I just want you to know this is something that we talk about." So you see him really develop and change as a result of his exposure to me and to seeing how I move through space versus how he moves through space. And it's a big leap of imagination for people to understand that other people have other experiences that are legitimate and real. It seems to be one of the most difficult things for people to understand, but he really made a great effort to do that. And I think that’s kind of extraordinary.

***

Purchase American Harvest from City Lights Bookstore.

youtube

#Marie Mutsuki Mockett#Garnette Cadogan#City Lights LIVE#author interviews#city lights bookstore#graywolf#nonfiction#american harvest#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Serendipity

Serendipity, a mentor once told me, is a secular way of speaking of grace; it’s unearned favor. Seen theologically, then, walking is an act of faith. Walking is, after all, interrupted falling. We see, we listen, we speak, and we trust that each step we take won’t be our last, but will lead us into a richer understanding of the self and the world.

Garnette Cadogan, “Walking While Black”

#serendipity#garnette cadogan#walking while black#lithub#austin kleon#grace#philosophy#eternal faith#trust

0 notes

Link

My love for walking started in childhood, out of necessity. No thanks to a stepfather with heavy hands, I found every reason to stay away from home and was usually out—at some friend’s house or at a street party where no minor should be— until it was too late to get public transportation. So I walked. The streets of Kingston, Jamaica, in the 1980s were often terrifying—you could, for instance, get killed if a political henchman thought you came from the wrong neighborhood, or even if you wore the wrong color. Wearing orange showed affiliation with one political party and green with the other, and if you were neutral or traveling far from home you chose your colors well. The wrong color in the wrong neighborhood could mean your last day. No wonder, then, that my friends and the rare nocturnal passerby declared me crazy for my long late-night treks that traversed warring political zones. (And sometimes I did pretend to be crazy, shouting non sequiturs when I passed through especially dangerous spots, such as the place where thieves hid on the banks of a storm drain. Predators would ignore or laugh at the kid in his school uniform speaking nonsense.)

I made friends with strangers and went from being a very shy and awkward kid to being an extroverted, awkward one. The beggar, the vendor, the poor laborer—those were experienced wanderers, and they became my nighttime instructors; they knew the streets and delivered lessons on how to navigate and enjoy them. I imagined myself as a Jamaican Tom Sawyer, one moment sauntering down the streets to pick low-hanging mangoes that I could reach from the sidewalk, another moment hanging outside a street party with battling sound systems, each armed with speakers piled to create skyscrapers of heavy bass. These streets weren’t frightening. They were full of adventure when they weren’t serene. There I’d join forces with a band of merry walkers, who’d miss the last bus by mere minutes, our feet still moving as we put out our thumbs to hitchhike to spots nearer home, making jokes as vehicle after vehicle raced past us. Or I’d get lost in Mittyesque moments, my young mind imagining alternate futures. The streets had their own safety: Unlike at home, there I could be myself without fear of bodily harm. Walking became so regular and familiar that the way home became home.

The streets had their rules, and I loved the challenge of trying to master them. I learned how to be alert to surrounding dangers and nearby delights, and prided myself on recognizing telling details that my peers missed. Kingston was a map of complex, and often bizarre, cultural and political and social activity, and I appointed myself its nighttime cartographer. I’d know how to navigate away from a predatory pace, and to speed up to chat when the cadence of a gait announced friendliness. It was almost always men I saw. A lone woman walking in the middle of the night was as common a sight as Sasquatch; moonlight pedestrianism was too dangerous for her. Sometimes at night as I made my way down from hills above Kingston, I’d have the impression that the city was set on “pause” or in extreme slow motion, as that as I descended I was cutting across Jamaica’s deep social divisions. I’d make my way briskly past the mansions in the hills overlooking the city, now transformed into a carpet of dotted lights under a curtain of stars, saunter by middle-class subdivisions hidden behind high walls crowned with barbed wire, and zigzag through neighborhoods of zinc and wooden shacks crammed together and leaning like a tight-knit group of limbo dancers. With my descent came an increase in the vibrancy of street life—except when it didn’t; some poor neighborhoods had both the violent gunfights and the eerily deserted streets of the cinematic Wild West. I knew well enough to avoid those even at high noon.

I’d begun hoofing it after dark when I was 10 years old. By 13 I was rarely home before midnight, and some nights found me racing against dawn. My mother would often complain, “Mek yuh love street suh? Yuh born a hospital; yuh neva born a street.” (“Why do you love the streets so much? You were born in a hospital, not in the streets.”)

* * * *

I left Jamaica in 1996 to attend college in New Orleans, a city I’d heard called “the northernmost Caribbean city.” I wanted to discover—on foot, of course—what was Caribbean and what was American about it. Stately mansions on oak-lined streets with streetcars clanging by, and brightly colored houses that made entire blocks look festive; people in resplendent costumes dancing to funky brass bands in the middle of the street; cuisine—and aromas—that mashed up culinary traditions from Africa, Europe, Asia, and the American South; and a juxtaposition of worlds old and new, odd and familiar: Who wouldn’t want to explore this?

On my first day in the city, I went walking for a few hours to get a feel for the place and to buy supplies to transform my dormitory room from a prison bunker into a welcoming space. When some university staff members found out what I’d been up to, they warned me to restrict my walking to the places recommended as safe to tourists and the parents of freshmen. They trotted out statistics about New Orleans’s crime rate. But Kingston’s crime rate dwarfed those numbers, and I decided to ignore these well-meant cautions. A city was waiting to be discovered, and I wouldn’t let inconvenient facts get in the way. These American criminals are nothing on Kingston’s, I thought. They’re no real threat to me.

What no one had told me was that I was the one who would be considered a threat.

Within days I noticed that many people on the street seemed apprehensive of me: Some gave me a circumspect glance as they approached, and then crossed the street; others, ahead, would glance behind, register my presence, and then speed up; older white women clutched their bags; young white men nervously greeted me, as if exchanging a salutation for their safety: “What’s up, bro?” On one occasion, less than a month after my arrival, I tried to help a man whose wheelchair was stuck in the middle of a crosswalk; he threatened to shoot me in the face, then asked a white pedestrian for help.

I wasn’t prepared for any of this. I had come from a majority-black country in which no one was wary of me because of my skin color. Now I wasn’t sure who was afraid of me. I was especially unprepared for the cops. They regularly stopped and bullied me, asking questions that took my guilt for granted. I’d never received what many of my African American friends call “The Talk”: No parents had told me how to behave when I was stopped by the police, how to be as polite and cooperative as possible, no matter what they said or did to me. So I had to cobble together my own rules of engagement. Thicken my Jamaican accent. Quickly mention my college. “Accidentally” pull out my college identification card when asked for my driver’s license.

My survival tactics began well before I left my dorm. I got out of the shower with the police in my head, assembling a cop-proof wardrobe. Light-colored oxford shirt. V-neck sweater. Khaki pants. Chukkas. Sweatshirt or T-shirt with my university insignia. When I walked I regularly had my identity challenged, but I also found ways to assert it. (So I’d dress Ivy League style, but would, later on, add my Jamaican pedigree by wearing Clarks Desert Boots, the footwear of choice of Jamaican street culture.) Yet the all-American sartorial choice of white T-shirt and jeans, which many police officers see as the uniform of black troublemakers, was off limits to me—at least, if I wanted to have the freedom of movement I desired.

In this city of exuberant streets, walking became a complex and often oppressive negotiation. I would see a white woman walking toward me at night and cross the street to reassure her that she was safe. I would forget something at home but not immediately turn around if someone was behind me, because I discovered that a sudden backtrack could cause alarm. (I had a cardinal rule: Keep a wide perimeter from people who might consider me a danger. If not, danger might visit me.) New Orleans suddenly felt more dangerous than Jamaica. The sidewalk was a minefield, and every hesitation and self-censored compensation reduced my dignity. Despite my best efforts, the streets never felt comfortably safe. Even a simple salutation was suspect.

One night, returning to the house that, eight years after my arrival, I thought I’d earned the right to call my home, I waved to a cop driving by. Moments later, I was against his car in handcuffs. When I later asked him—sheepishly, of course; any other way would have asked for bruises—why he had detained me, he said my greeting had aroused his suspicion. “No one waves to the police,” he explained. When I told friends of his response, it was my behavior, not his, that they saw as absurd. “Now why would you do a dumb thing like that?” said one. “You know better than to make nice with police.”

* * * *

A few days after I left on a visit to Kingston, Hurricane Katrina slashed and pummeled New Orleans. I’d gone not because of the storm but because my adoptive grandmother, Pearl, was dying of cancer. I hadn’t wandered those streets in eight years, since my last visit, and I returned to them now mostly at night, the time I found best for thinking, praying, crying. I walked to feel less alienated—from myself, struggling with the pain of seeing my grandmother terminally ill; from my home in New Orleans, underwater and seemingly abandoned; from my home country, which now, precisely because of its childhood familiarity, felt foreign to me. I was surprised by how familiar those streets felt. Here was the corner where the fragrance of jerk chicken greeted me, along with the warm tenor and peace-and-love message of Half Pint’s “Greetings,” broadcast from a small but powerful speaker to at least a half-mile radius. It was as if I had walked into 1986, down to the soundtrack. And there was the wall of the neighborhood shop, adorned with the Rastafarian colors red, gold, and green along with images of local and international heroes Bob Marley, Marcus Garvey, and Haile Selassie. The crew of boys leaning against it and joshing each other were recognizable; different faces, similar stories.

I was astonished at how safe the streets felt to me, once again one black body among many, no longer having to anticipate the many ways my presence might instill fear and how to offer some reassuring body language. Passing police cars were once again merely passing police cars. Jamaican police could be pretty brutal, but they didn’t notice me the way American police did. I could be invisible in Jamaica in a way I can’t be invisible in the United States. Walking had returned to me a greater set of possibilities.

And why walk, if not to create a new set of possibilities? Following serendipity, I added new routes to the mental maps I had made from constant walking in that city from childhood to young adulthood, traced variations on the old pathways. Serendipity, a mentor once told me, is a secular way of speaking of grace; it’s unearned favor. Seen theologically, then, walking is an act of faith. Walking is, after all, interrupted falling. We see, we listen, we speak, and we trust that each step we take won’t be our last, but will lead us into a richer understanding of the self and the world.

In Jamaica, I felt once again as if the only identity that mattered was my own, not the constricted one that others had constructed for me. I strolled into my better self. I said, along with Kierkegaard, “I have walked myself into my best thoughts.”

* * * *

When I tried to return to New Orleans from Jamaica a month later, there were no flights. I thought about flying to Texas so I could make my way back to my neighborhood as soon as it opened for reoccupancy, but my adoptive aunt, Maxine, who hated the idea of me returning to a hurricane zone before the end of hurricane season, persuaded me to come to stay in New York City instead. (To strengthen her case she sent me an article about Texans who were buying up guns because they were afraid of the influx of black people from New Orleans.)

This wasn’t a hard sell: I wanted to be in a place where I could travel by foot and, more crucially, continue to reap the solace of walking at night. And I was eager to follow in the steps of the essayists, poets, and novelists who’d wandered that great city before me—Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Alfred Kazin, Elizabeth Hardwick. I had visited the city before, but each trip had felt like a tour in a sports car. I welcomed the chance to stroll. I wanted to walk alongside Whitman’s ghost and “descend to the pavements, merge with the crowd, and gaze with them.” So I left Kingston, the popular Jamaican farewell echoing in my mind: “Walk good!” Be safe on your journey, in other words, and all the best in your endeavors.

* * * *

I arrived in New York City, ready to lose myself in Whitman’s “Manhattan crowds, with their turbulent musical chorus!” I marveled at what Jane Jacobs praised as “the ballet of the good city sidewalk” in her old neighborhood, the West Village. I walked up past midtown skyscrapers, releasing their energy as lively people onto the streets, and on into the Upper West Side, with its regal Beaux Arts apartment buildings, stylish residents, and buzzing streets. Onward into Washington Heights, the sidewalks spilled over with an ebullient mix of young and old Jewish and Dominican American residents, past leafy Inwood, with parks whose grades rose to reveal beautiful views of the Hudson River, up to my home in Kingsbridge in the Bronx, with its rows of brick bungalows and apartment buildings nearby Broadway’s bustling sidewalks and the peaceful expanse of Van Cortlandt Park. I went to Jackson Heights in Queens to take in people socializing around garden courtyards in Urdu, Korean, Spanish, Russian, and Hindi. And when I wanted a taste of home, I headed to Brooklyn, in Crown Heights, for Jamaican food and music and humor mixed in with the flavor of New York City. The city was my playground.

I explored the city with friends, and then with a woman I’d begun dating. She walked around endlessly with me, taking in New York City’s many pleasures. Coffee shops open until predawn; verdant parks with nooks aplenty; food and music from across the globe; quirky neighborhoods with quirkier residents. My impressions of the city took shape during my walks with her.

As with the relationship, those first few months of urban exploration were all romance. The city was beguiling, exhilarating, vibrant. But it wasn’t long before reality reminded me I wasn’t invulnerable, especially when I walked alone.

One night in the East Village, I was running to dinner when a white man in front of me turned and punched me in the chest with such force that I thought my ribs had braided around my spine. I assumed he was drunk or had mistaken me for an old enemy, but found out soon enough that he’d merely assumed I was a criminal because of my race. When he discovered I wasn’t what he imagined, he went on to tell me that his assault was my own fault for running up behind him. I blew off this incident as an aberration, but the mutual distrust between me and the police was impossible to ignore. It felt elemental. They’d enter a subway platform; I’d notice them. (And I’d notice all the other black men registering their presence as well, while just about everyone else remained oblivious to them.) They’d glare. I’d get nervous and glance. They’d observe me steadily. I’d get uneasy. I’d observe them back, worrying that I looked suspicious. Their suspicions would increase. We’d continue the silent, uneasy dialogue until the subway arrived and separated us at last.

I returned to the old rules I’d set for myself in New Orleans, with elaboration. No running, especially at night; no sudden movements; no hoodies; no objects—especially shiny ones—in hand; no waiting for friends on street corners, lest I be mistaken for a drug dealer; no standing near a corner on the cell phone (same reason). As comfort set in, inevitably I began to break some of those rules, until a night encounter sent me zealously back to them, having learned that anything less than vigilance was carelessness.

After a sumptuous Italian dinner and drinks with friends, I was jogging to the subway at Columbus Circle—I was running late to meet another set of friends at a concert downtown. I heard someone shouting and I looked up to see a police officer approaching with his gun trained on me. “Against the car!” In no time, half a dozen cops were upon me, chucking me against the car and tightly handcuffing me. “Why were you running?” “Where are you going?” “Where are you coming from?” “I said, why were you running?!” Since I couldn’t answer everyone at once, I decided to respond first to the one who looked most likely to hit me. I was surrounded by a swarm and tried to focus on just one without inadvertently aggravating the others.

It didn’t work. As I answered that one, the others got frustrated that I wasn’t answering them fast enough and barked at me. One of them, digging through my already-emptied pockets, asked if I had any weapons, the question more an accusation. Another badgered me about where I was coming from, as if on the fifteenth round I’d decide to tell him the truth he imagined. Though I kept saying—calmly, of course, which meant trying to manage a tone that ignored my racing heart and their spittle-filled shouts in my face—that I had just left friends two blocks down the road, who were all still there and could vouch for me, to meet other friends whose text messages on my phone could verify that, yes, sir, yes, officer, of course, officer, it made no difference. For a black man, to assert your dignity before the police was to risk assault. In fact, the dignity of black people meant less to them, which was why I always felt safer being stopped in front of white witnesses than black witnesses. The cops had less regard for the witness and entreaties of black onlookers, whereas the concern of white witnesses usually registered on them. A black witness asking a question or politely raising an objection could quickly become a fellow detainee. Deference to the police, then, was sine qua non for a safe encounter.

The cops ignored my explanations and my suggestions and continued to snarl at me. All except one of them, a captain. He put his hand on my back, and said to no one in particular, “If he was running for a long time he would have been sweating.” He then instructed that the cuffs be removed. He told me that a black man had stabbed someone earlier two or three blocks away and they were searching for him. I noted that I had no blood on me and had told his fellow officers where I’d been and how to check my alibi—unaware that it was even an alibi, as no one had told me why I was being held, and of course, I hadn’t dared ask. From what I’d seen, anything beyond passivity would be interpreted as aggression.

The police captain said I could go. None of the cops who detained me thought an apology was necessary. Like the thug who punched me in the East Village, they seemed to think it was my own fault for running.

Humiliated, I tried not to make eye contact with the onlookers on the sidewalk, and I was reluctant to pass them to be on my way. The captain, maybe noticing my shame, offered to give me a ride to the subway station. When he dropped me off and I thanked him for his help, he said, “It’s because you were polite that we let you go. If you were acting up it would have been different.” I nodded and said nothing.

* * * *

I realized that what I least liked about walking in New York City wasn’t merely having to learn new rules of navigation and socialization—every city has its own. It was the arbitrariness of the circumstances that required them, an arbitrariness that made me feel like a child again, that infantilized me. When we first learn to walk, the world around us threatens to crash into us. Every step is risky. We train ourselves to walk without crashing by being attentive to our movements, and extra-attentive to the world around us. As adults we walk without thinking, really. But as a black adult I am often returned to that moment in childhood when I’m just learning to walk. I am once again on high alert, vigilant. Some days, when I am fed up with being considered a troublemaker upon sight, I joke that the last time a cop was happy to see a black male walking was when that male was a baby taking his first steps.

On many walks, I ask white friends to accompany me, just to avoid being treated like a threat. Walks in New York City, that is; in New Orleans, a white woman in my company sometimes attracted more hostility. (And it is not lost on me that my woman friends are those who best understand my plight; they have developed their own vigilance in an environment where they are constantly treated as targets of sexual attention.) Much of my walking is as my friend Rebecca once described it: A pantomime undertaken to avoid the choreography of criminality.

* * * *

Walking while black restricts the experience of walking, renders inaccessible the classic Romantic experience of walking alone. It forces me to be in constant relationship with others, unable to join the New York flâneurs I had read about and hoped to join. Instead of meandering aimlessly in the footsteps of Whitman, Melville, Kazin, and Vivian Gornick, more often I felt that I was tiptoeing in Baldwin’s—the Baldwin who wrote, way back in 1960, “Rare, indeed, is the Harlem citizen, from the most circumspect church member to the most shiftless adolescent, who does not have a long tale to tell of police incompetence, injustice, or brutality. I myself have witnessed and endured it more than once.”

Walking as a black man has made me feel simultaneously more removed from the city, in my awareness that I am perceived as suspect, and more closely connected to it, in the full attentiveness demanded by my vigilance. It has made me walk more purposefully in the city, becoming part of its flow, rather than observing, standing apart.

* * * *

But it also means that I’m still trying to arrive in a city that isn’t quite mine. One definition of home is that it’s somewhere we can most be ourselves. And when are we more ourselves but when walking, that natural state in which we repeat one of the first actions we learned? Walking—the simple, monotonous act of placing one foot before the other to prevent falling—turns out not to be so simple if you’re black. Walking alone has been anything but monotonous for me; monotony is a luxury.

A foot leaves, a foot lands, and our longing gives it momentum from rest to rest. We long to look, to think, to talk, to get away. But more than anything else, we long to be free. We want the freedom and pleasure of walking without fear—without others’ fear—wherever we choose. I’ve lived in New York City for almost a decade and have not stopped walking its fascinating streets. And I have not stopped longing to find the solace that I found as a kid on the streets of Kingston. Much as coming to know New York City’s streets has made it closer to home to me, the city also withholds itself from me via those very streets. I walk them, alternately invisible and too prominent. So I walk caught between memory and forgetting, between memory and forgiveness. [h/t]

#garnette cadogan#walking while black#while black#walking#literary hub#long reads#jamaica#kingston jamaica#new orleans#new york city#police brutality#police terrorism#racism#ruddy roye#boing boing

0 notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview: Garnette Cadogan

This year, our friends and PNW/NYC brethren at Tin House are curating Dear Reader, our one-night writer’s residency at Ace Hotel New York. Each month, Tin House will invite a writer to spend the night, penning a letter to an imagined audience. On a surprise date the following month, the letter will be laid bedside in each room — hand stamped and numbered — to be found and read, a hybrid between a Dear John letter, an exhibitionist missive and a time-based limited edition art object.

January’s letter-writer was Garnette Cadogan, brilliant essayist, author of “Walking While Black,” editor-at-large for Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas (co-edited by Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro), and a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia. We caught up with Garnette after his stay to talk about the exaltation of epistolary pursuits, word clouds and the inimitable kitchen counter (every writer should have one).

If you could correspond with any fictional character or literary figure via letters, who would it be? And why?

What better correspondence is there than one which makes you rip open each letter — or click open, if, like most people, email is the way you exchange letters (but, oh, the tactile joys you’re denied!) — excited at the things you’ll learn? Things you learn not only about the person writing, but also about the world, about yourself, about things you didn’t even know you’d ever have any interest in. If there’s charm and humor and brilliance and affection and playfulness in the mix, all the better. I guess, then, that I’d love to correspond with Virginia Woolf, who could be all these things and more. (I would, however, tell her to hold back on the Bloomsbury gossip; and I would hope that my criticisms of her snobbishness toward the middle-class and my stronger criticism of her more inexcusable intolerances wouldn’t make her stop writing. If so, I’d just start corresponding with George Orwell, whose life was so full of varied adventure and who had so many wise things to say about books and politics and life in general, that I would only send him letters that said “Tell me more, Eric.”)

Do you map out your writing, or do you discover your path as you go? How often does your work go in directions you never expected?

I map out my writing in the loosest way—by writing a word cloud. I jot down the themes, questions, and problems that most intrigue me. (This is why I always begin my writing on paper; my first drafts are a bunch of words and a few questions, with lines drawn between them). I write down words that remind me of people or scenes or stories that I’d love to explore or introduce to readers. And then I start searching for a way in: I fuss over the beginning, treating it as a skeleton key that will unlock the rest of the piece. Once I know how to begin I feel confident that much else will fall in place. I then write the opener, and pull back to write a word cloud for each successive paragraph, moving from a neighborhood of words to a pathway of paragraphs.

And I’m never sure where I will go. Not true, actually — I always know where I will go before I begin writing, but I never want to end up there at the end. If I follow the route I had seen in my mind’s eye, then I feel that I have learned nothing; my writing, at the least, should be a process of discovery. Writing should teach me something new, should open doors that lead to interesting new places. This is why in the early stages I plan very little beyond putting down the ideas, moods, and characters that interest me — I’m reluctant to shut down the side routes that lead to fascinating destinations.

Dear Reader tasks you with writing for an imagined audience of strangers. How much do you think about your audience when you write? Have you ever been surprised by who is drawn to your work?

I am drawn to questions that demand patience and thoughtfulness. As I pursue these, hoping to discover stories and ideas that reveal how fascinating and irreducibly complex our world is, I hope that I’ll please myself at my most curious, most thoughtful, most compassionate. And in doing so, I pretend that I am a stand-in for an audience of thoughtful people. But I also imagine myself at my worst — impatient, lazy, obnoxious — and try to write to move this version of me to listen to the best me. So, I try to be a spectrum of readers and hope that, in satisfying the various versions of me, I’ll say something that will enrich to a variety of readers, including some not ready to give me a fair listening. But I am sometimes — too often, really, when I write — my own worst critic. When I can’t turn off Mr. Hyper-Critic, I imagine that my dear friend Becky Saletan—as good a reader as you’ll ever encounter — is my audience.

And I’m always surprised by the people who are drawn to my work. Without exaggeration, I am surprised by anyone who is drawn to my work. I’ve roamed around my own head and seen the detritus in there; since my writing is me trying to shape something coherent out of the rubbish that often passes for my thinking, I’m always taken aback when a reader tells me that my words were worth reading. Until I can read my work with the objectivity that Becky does, I’ll be constantly surprised — but it’s not such a bad thing that I’m grateful for every reader who has taken the time to read my work (including those who don’t like it but took the time to read to the end).

What's a book that you wish more people knew about?

It seems perverse to wish that a book that is well-known (in the United Kingdom, that is; far too many in the U.S. are unaware of it) were much better known by many more people, but I’m convinced that not enough of us have read Robert Macfarlane’s marvelous The Old Ways, a book he rightly describes as being about “landscape and the human heart.” It’s a beautiful—yes, that’s the word!—book about the joy and richness of encounter, the value of friendship and companionship, the beauty of nature and people who find themselves attracted to it, the importance of attentiveness and its role in deepening compassion, and the fundamental need for us to wander and wonder. Maybe one day I’ll stand on the street corner with crates of this book and hand them out to everyone who passes, shouting “Read it today, I beseech you!”

Do you have any rituals or ceremonies that accompany your writing process?

The only rituals that accompany my writing are ones that need to be quashed. After all, they are rituals of procrastination: talking to friends; reading good books on related topics; nightwalking during which I turn over ideas in my head (and, alas, turn away from my desk, to which I ought to chain myself). I have no ceremonies or requirements that accompany my writing, except that I need to have pen and paper (in any form—napkins, concert programs, even cereal boxes; I don’t write on a laptop until I have most or everything down on paper).

I do have preferences for my writing, though—the most important of which is that I love writing on a kitchen counter. I do my best work writing on a kitchen counter. In my dream office, my desk is custom-made from a kitchen counter.

This interview was simultaneously published on Tin House’s blog, along with other inspiring interviews, notes and literary ephemera.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back in 1952, the great American science fiction writer Ray Bradbury published a short story called “The Pedestrian” in a small antifascist publication. The story, which was based on Bradbury’s own experience of being hassled by the cops while walking the streets of Los Angeles, imagined a world in which automobile dominance was so complete that walking for any purpose would be seen as a sign of mental illness. We take a look back at Bradbury’s dystopian vision, and talk with four people — paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva and writers Garnette Cadogan, David Ulin and Antonia Malchik — about how walking contributes to our essential humanity, and what we lose when we build environments that make it impossible for people to walk.

an episode from the podcast The War on Cars

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walking While Black by GARNETTE CADOGAN

Walking While Black by GARNETTE CADOGAN

“My only sin is my skin. What did I do, to be so black and blue?”

–Fats Waller, “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue?”

“Manhattan’s streets I saunter’d, pondering.”

–Walt Whitman, “Manhattan’s Streets I Saunter’d, Pondering”

My love for walking started in childhood, out of necessity. No thanks to a stepfather with heavy hands, I found every reason to stay away from home and was usually out—at…

View On WordPress

#Gangs#GARNETTE CADOGAN#Life / Society#racism#reasons to stay away from home#the challenge of trying to master the rules of the streetm#understanding of African American history and culture#wrong color in the wrong neighborhood

0 notes

Photo

On May 8, we're thrilled to present our annual Nonfiction Night! Hear outstanding new work from Ben Greenman (Dig If You Will The Picture), Sarah Gerard (Sunshine State), Kristen Radtke (Imagine Wanting Only This), Garnette Cadogan (Freeman's, The Fire This Time), and Mensah Demary (VICE, Literary Hub).

As always, admission is free, drafts $5, and we’ll have a free-to-enter raffle for our authors’ incredible books. Check our Facebook event page for more information.

#brooklyn#Brooklyn Events#Brooklyn Nightlife#literature#literary#literary events#nonfiction#essays#biographies & memoirs#prince#franklin park reading series#Franklin Park#ben greenman#kristen radtke#sarah gerard#garnette cadogan#mensah demary

0 notes

Text

Blogpost #5

Towards the end of Walking While Black, Garnette Cadogan writes about how walking as a black man has made him both removed and resonant with cities that require his constant attention. This description of seeing the violence that is a part of Black life in the U.S. echoes Baldwin’s writings on truly seeing the perpetrators of racist violence: “And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage; you never had to look at me. I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can change until it is faced.” Simply moving yourself through the world, by walking or living or filming, reflects the world. They are all a kind of camera, recording the Black experience.

I Am Not Your Negro is interspersed with slow clips of empty cityscapes and landscapes deliberately moving by, as if shot by somebody staring out of the window of a rolling car or train. There isn’t a lot in these scenes, but with Baldwin’s incisive texts, they resonate with Cadogan’s truth that “monotony is a luxury”. They feel like a stroll, full of vigilance and observation.

Time is a slow moment in these pieces, but it also jumps and folds. Peck took the prophecy of Baldwin’s writing and made it into a flowing document of Blackness across American history. The Watts Protests cut to Oakland during the Holy Week Rising cut to Ferguson. Samuel L. Jackson’s bass narration, recorded in 2015, feels like a historical document, while clips of Baldwin, gesturing with his cigarette, his eyebrows raising theatrically, feel contemporary. The two Baldwins exist together and trade places.

0 notes

Text

The World Before Your Feet

The World Before Your Feet [trailer]

For over six years, and for reasons he can't explain, Matt Green, has been walking every block of every street in New York City - a journey of more than 8,000 miles.

While the project as a whole is a tad ambitious, it's a great doc, and I very much appreciate the intent of the walk. All the people he meets along the way, and the things he learns. The history, the anecdotes, the trivia. The photos he starts to collect, the barber shops, the 9/11 memorials, the plants and flowers.

When going on a city trip, I try myself to walk as much as possible since you notice and discover so many interesting things that are not covered in travel guides, and that may lead to do some more research afterwards.

Striking example for "white privilege" provided by another walker named Garnette Cadogan of Jamaican descent, who says he tries to dress and move in a "non-threatening" way to minimise the risk that he will be seen as a threat, and be harassed or assaulted because of his race.

0 notes

Text

Reading: https://lithub.com/walking-while-black/ This paper is an imitation of

Reading: https://lithub.com/walking-while-black/ This paper is an imitation of Garnette Cadogan’s ‘Walking While Black’ (Links to an external site.) essay. In writing it, you will present and argue how opinions you and others have influence behaviors, modeling after Cadogan’s writing techniques. Three revisions and a Works Cited page in MLA style are required. The experience you narrate (in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Walking had returned to me a greater set of possibilities. And why walk, if not to create a new set of possibilities? Following serendipity, I added new routes to the mental maps I had made from constant walking in that city from childhood to young adulthood, traced variations on the old pathways. Serendipity, a mentor once told me, is a secular way of speaking of grace; it's unearned favor. Seen theologically, then, walking is an act of faith. Walking is, after all, interrupted falling. We see, we listen, we speak, and we trust that each step we take won't be our last, but will lead us into a richer understanding of the self and the world. --Garnette Cadogan, "Black and Blue," in The Fire This Time

0 notes

Text

Jesmyn Ward (editor) - The Fire This Time

This was a book club selection, paired with James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. Pretty much all of us enjoyed this collection of essays, which was written post-Ferguson and as much in response to events around that time as it was to Baldwin’s book. It was interesting to see how each writer chose to interact with Baldwin, and at times devastating to see how little really has changed since Baldwin’s writing. Even moreso given the continued tragedies that have happened since this was published. A phrase comes to mind from one of the later essays by Daniel Jose Older in which he laments “the tragedy of how familiar it feels to mourn a stranger” - a feeling that has only become more familiar since this collection was published in 2016.

There are some really outstanding essays in here. I found this worked particularly well as a book club selection, because we meet weekly to discuss what we’re reading, usually assigning around 50 pages a week. This meant more time to sit with individual essays than I would have taken if reading this on my own. And as editor, Ward makes some great choices in how these are put together, sometimes in concert and sometimes in juxtaposition. There is a short piece by Isabel Wilkerson in which she lays bare the stark realities of the civil rights movement in under four pages, yet still manages to infuse historic tragedy with a call for love and a sense of hope. And the way that Ward sandwiches this short piece in between two longer pieces that thread together personal history with scholarship really worked for me.

Similarly, there was an essay by Garnette Cadogan which spoke about walking the streets of America as a Black immigrant in the U.S., which was followed by a piece by Claudia Rankine called “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning” that I found to be the most powerful piece in the collection. A friend in book club mentioned that the Cadogan showed a viewpoint that she’s read and heard before - it was familiar, but done very well. And then the Rankine went well beyond the familiar and gave a perspective that is less familiar, focusing on Black motherhood and particularly the choices that Black mothers must make when their children have been killed by racists. And I think that Ward does a great job of providing multiple viewpoints and a mixing up the tenor and tone to keep a certain flow for the reader.

In the end, my favorite essay was by Kiese Laymon, who I’ve heard a lot about but hadn’t read yet. I know everyone talks about his memoir Heavy but when I read his essay, I went ahead and bought his novel Long Division, which he talks about in the essay and sounds like a really fun read. When I mentioned that to book club folks, they were also interested, so that’s what we’ll be reading next.

0 notes