#from the book by l. frank baum (1900)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Judy Garland

(No.67-70)

The Wizard of Oz dir. Victor Fleming | 1939

#judy garland#the wizard of oz#1939#dir: victor fleming#gorgeous american singer#actress#christmas classic#from the book by l. frank baum (1900)#webfiles#1930's#technecolor#musical#old hollywood

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

So... Wicked is coming back in style. And as such I need to make a little informative post.

Because since as early as my arrival onto the Internet, in the distant years of the late 2000s, a lot of people have been treating Wicked as some sort of "official" part of the Oz series. As part of the Oz canon or as THE "original" work everything else derives from (literaly, some people, probably kids, but did believe the MGM movie was made BASED on Wicked...) And as an Oz fan, that bothers me.

[Damn, ever since I watched Coco Peru's videos her voice echoes in my brain each time I say this line.]

So here's a few FACTS for you facts lovers.

The Wicked movie that is coming out right now (I was sold this as a series, turns out it is a movie duology?) is a cinematic adaptation of the stage musical Wicked created by Schwartz and Holzman, the Broadway classic and success of the 2000s (it was created in 2003).

Now, the Wicked musical everybody knows is itself an adaptation - and this fact is not as notorios, somehow? The Wicked musical is the adaptation of a novel released in 1995 by Gregory Maguire, called Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. A very loose and condensed adaptation to say the least - as the Wicked musical is basically a lighter and simplified take on a much darker, brooding and mature tale. Basically fans of the novel have accused the musical of being some sort of honeyed, sugary-sweet, highschool-romance-fanfic-AU, while those who enjoyed the musical and went to see the novel are often shocked at discovering their favorite musical is based on what is basically a "dark and edgy - let's shock them all" take on the Oz lore. (Some do like both however, apparently? But I rarely met them.)

A side-fact which will be relevant later, is that this novel was but the first of a full series of novel Oz wrote about a dark-and-adult fantasy reimagining of the land of Oz - there's Son of a Witch, A Lion Among Men, Out of Oz, and more.

However the real fact I want to point out is that Maguire's novel, from which the musical itself derives, is a "grimmification" (to take back TV Tropes terminology) of the 1939 MGM movie The Wizard of Oz. The movie everybody knows when it comes to Oz, but that everybody forgets is itself the adaptation of a book - the same way people forget the Wicked musical is adapted from a novel. The MGM movie is adapted from L. Frank Baum's famous 1900 classic for children The Wonderful Wizard of Oz - and a quite loose adaptation that reimagines a lot of elements and details.

Now, a lot of people present Maguire's novel as being based/inspired/a revisionist take on Baum's novel... And that's false. Maguire's Wicked novel is clearly dominated by and mainly influenced by the MGM movie, with only a few book elements and details sprinkled on top. Mind you, the sequels Maguire wrote do take more elements, characters and plot points from the various Oz books of Baum... But they stay mostly Maguire's personal fantasy world. Yes, Oz "books" in plural - because that's a fact people tend to not know either... L. Frank Baum didn't just write one book about the Land of Oz. He wrote FOURTEEN of them, an entire series, because it was his most popular sales, and his audience like his editor pressured him to produce more (in fact he got sick of Oz and tried to write other books, but since they failed he was forced to continue Oz novels to survive). Everybody forgot about the Oz series due to the massive success of the starter novel - but it has a lot of very famous sequels, such as The Marvelous Land of Oz or Ozma of Oz (the later was loosely adapted by Disney as the famous 80s nostalgic-cursed movie Return to Oz).

So... To return to my original point. The current Wicked movies are not directly linked in any way to Baum's novel. The Wicked musical was already as "canon" and as "linked" to the MGM movie as 2013's Oz The Great and Powerful by Disney was. As for Maguire's novel, due to its dark, mature, brooding and more complex worldbuilding nature, I can only compare it to the recent attempt at making a "Game of Thrones Oz" through the television series Emerald City.

The Wicked movies coming out are separated from Baum's novel at the fourth degree. Because they are the movie adaptation of a musical adaptation of a novel reinventing a movie adaptation of the original children book.

And I could go even FURTHER if you dare me to and claim the Wicked movies are at the 5TH DEGREE! Because a little-known-fact is that the MGM movie was not a direct adaptation of Baum's novel... But rather took a lot of cues and influence from the massively famous stage-extravaganza of 1902 The Wizard of Oz... A musical adaptation of Baum's novel, created and written by Baum himself, and that was actually more popular than the novel in the pre-World War II America. It was from this enormous Broadway success (my my, how the snake bites its tail - the 1902 Wizard of Oz was the musical Wicked of its time) that, for example, the movie took the idea of the Good Witch of the North killing the sleeping-poppies with snow.

#oz#wicked#the land of oz#the wonderful wizard of oz#the wizard of oz#the life and times of the wicked witch of the west#musical#broadway#history of broadway#l. frank baum#mgm movie#MGM's the wizard of oz#the wicked witch of the west#gregory maguire#wicked musical#history of oz#oz adaptations

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The BFG by Roald Dahl (1982)

Captured by a giant! The BFG is no ordinary bone-crunching giant. He is far too nice and jumbly. It's lucky for Sophie that he is. Had she been carried off in the middle of the night by the Bloodbottler, the Fleshlumpeater, the Bonecruncher, or any of the other giants-rather than the BFG-she would have soon become breakfast.

When Sophie hears that they are flush-bunking off in England to swollomp a few nice little chiddlers, she decides she must stop them once and for all. And the BFG is going to help her!

Graceling Realm by Kristen Cashore (2008-2022)

Graceling tells the story of the vulnerable-yet-strong Katsa, who is smart and beautiful and lives in the Seven Kingdoms where selected people are born with a Grace, a special talent that can be anything at all. Katsa's Grace is killing. As the king's niece, she is forced to use her extreme skills as his brutal enforcer. Until the day she meets Prince Po, who is Graced with combat skills, and Katsa's life begins to change. She never expects to become Po's friend. She never expects to learn a new truth about her own Grace--or about a terrible secret that lies hidden far away . . . a secret that could destroy all seven kingdoms with words alone.

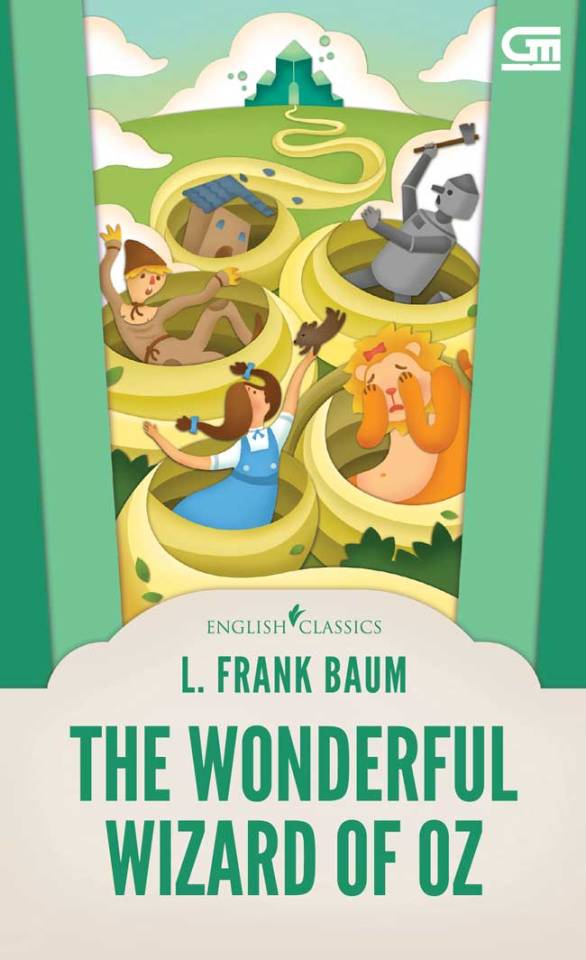

Oz by L. Frank Baum (1900-1920)

Join Dorothy and her little dog Toto on the yellow brick road, as they set off to explore the magical Land of Oz. Can they find the Wizard, defeat the Wicked Witch of the West, and return to Kansas?

Stardust by Neil Gaiman (1997)

Catch a fallen star . . .

Tristran Thorn promised to bring back a fallen star. So he sets out on a journey to fulfill the request of his beloved, the hauntingly beautiful Victoria Forester--and stumbles into the enchanted realm that lies beyond the wall of his English country town. Rich with adventure and magic, Stardust is one of master storyteller Neil Gaiman's most beloved tales, and the inspiration for the hit movie.

Inkworld by Cornelia Funke (2003-2023)

One cruel night, Meggie's father reads aloud from a book called INKHEART-- and an evil ruler escapes the boundaries of fiction and lands in their living room. Suddenly, Meggie is smack in the middle of the kind of adventure she has only read about in books. Meggie must learn to harness the magic that has conjured this nightmare. For only she can change the course of the story that has changed her life forever.

Ella Enchanted by Gail Carson Levine (1997)

At birth, Ella is inadvertently cursed by an imprudent young fairy named Lucinda, who bestows on her the "gift" of obedience. Anything anyone tells her to do, Ella must obey. Another girl might have been cowed by this affliction, but not feisty Ella: "Instead of making me docile, Lucinda's curse made a rebel of me. Or perhaps I was that way naturally." When her beloved mother dies, leaving her in the care of a mostly absent and avaricious father, and later, a loathsome stepmother and two treacherous stepsisters, Ella's life and well-being seem to be in grave peril. But her intelligence and saucy nature keep her in good stead as she sets out on a quest for freedom and self-discovery as she tries to track down Lucinda to undo the curse, fending off ogres, befriending elves, and falling in love with a prince along the way. Yes, there is a pumpkin coach, a glass slipper, and a happily ever after, but this is the most remarkable, delightful, and profound version of Cinderella you'll ever read.

The Witches by Roald Dahl (1983)

This is not a fairy-tale. This is about real witches. Real witches don't ride around on broomsticks. They don't even wear black cloaks and hats. They are vile, cunning, detestable creatures who disguise themselves as nice, ordinary ladies. So how can you tell when you're face to face with one? Well, if you don't know yet you'd better find out quickly-because there's nothing a witch loathes quite as much as children and she'll wield all kinds of terrifying powers to get rid of them.

The Kane Chronicles by Rick Riordan (2010-2012)

Since their mother's death, Carter and Sadie have become near strangers. While Sadie has lived with her grandparents in London, her brother has traveled the world with their father, the brilliant Egyptologist, Dr. Julius Kane. One night, Dr. Kane brings the siblings together for a "research experiment" at the British Museum, where he hopes to set things right for his family. Instead, he unleashes the Egyptian god Set, who banishes him to oblivion and forces the children to flee for their lives. Soon, Sadie and Carter discover that the gods of Egypt are waking, and the worst of them--Set?has his sights on the Kanes. To stop him, the siblings embark on a dangerous journey across the globe -- a quest that brings them ever closer to the truth about their family, and their links to a secret order that has existed since the time of the pharaohs.

Discworld by Terry Pratchett (1983-2015)

In the beginning there was… a turtle.

Somewhere on the frontier between thought and reality exists the Discworld, a parallel time and place which might sound and smell very much like our own, but which looks completely different.

Particularly as it’s carried through space on the back of a giant turtle.

It plays by different rules. But then, some things are the same everywhere. The Disc’s very existence is about to be threatened by a strange new blight: the world’s first tourist, upon whose survival rests the peace and prosperity of the land.

Unfortunately, the person charged with maintaining that survival in the face of robbers, mercenaries and, well, Death, is a spectacularly inept wizard…

Daughter of Smoke & Bone by Laini Taylor (2011-2014)

Around the world, black handprints are appearing on doorways, scorched there by winged strangers who have crept through a slit in the sky.

In a dark and dusty shop, a devil's supply of human teeth grown dangerously low.

And in the tangled lanes of Prague, a young art student is about to be caught up in a brutal otherwordly war.

Meet Karou. She fills her sketchbooks with monsters that may or may not be real; she's prone to disappearing on mysterious "errands"; she speaks many languages—not all of them human; and her bright blue hair actually grows out of her head that color. Who is she? That is the question that haunts her, and she's about to find out.

When one of the strangers—beautiful, haunted Akiva—fixes his fire-colored eyes on her in an alley in Marrakesh, the result is blood and starlight, secrets unveiled, and a star-crossed love whose roots drink deep of a violent past. But will Karou live to regret learning the truth about herself?

#best fantasy book#poll#the bfg#graceling realm#oz#stardust#inkworld#ella enchanted#the witches#the kane chronicles#discworld#daughter of smoke and bone

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

WELCOMES YOU TO THE LAND OF OZ WITH THE HAPPIEST SMILE YOU'VE EVER SEEN.

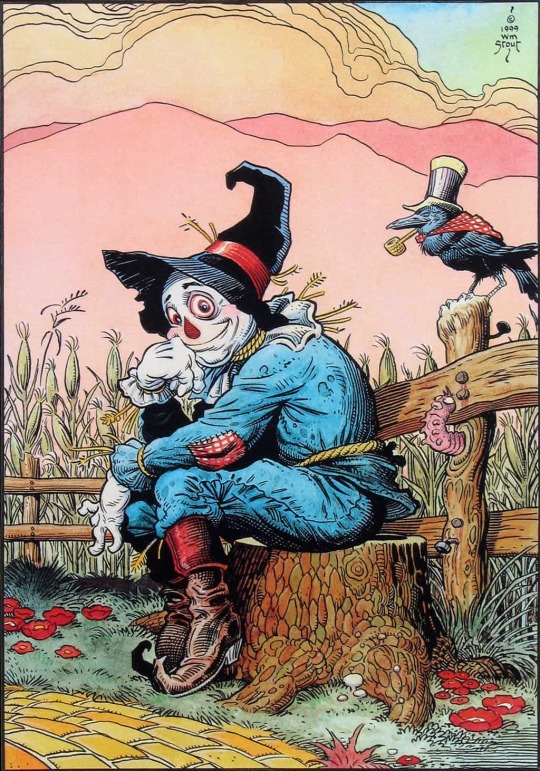

PIC(S) INFO: Resolution at 1024x1462 (2x) -- Spotlight on the Scarecrow of Oz, ink and watercolors on board, original and a close-up version, from the American children's literature classic, "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" (1900) by L. Frank Baum. Artwork by William Stout.

"When I was a boy I was tremendously interested in scarecrows. They always seemed to my childish imagination as just about to wave their arms, straighten up and stalk across the field on their long legs. I lived on a farm, you know. It was natural then that my first character in this animated life series was the scarecrow, on whom I have taken revenge for all the mystic feeling he once inspired."

-- LYMAN FRANK BAUM, a.k.a., L. Frank Baum (1856–1919), American author and creator of the "Land of Oz" books

Source: www.americanlegacyfinearts.com/artwork/scarecrow-of-oz.

#Scarecrow of Oz#Scarecrow#Land of Oz#Oz books#Oz#L. Frank Baum#Fantasy#Fantasy Art#Lyman Frank Baum#Books#William Stout Artist#William Stout#Kids books#Wonderful Wizard of Oz#The Scarecrow of Oz#Kidcore#The Scarecrow#William Stout Art#Vintage Kidcore#American Art#Americana#Watercolors#Watercolor Art#Illustration#Oz Series of Books#Children's Literature#American Style#Oz Series#Children's books#Vintage Illustration

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

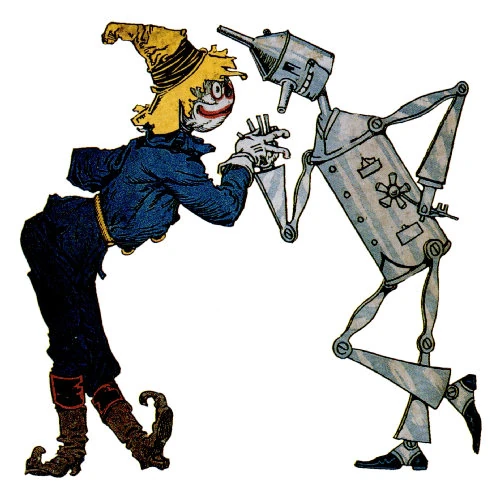

the Scarecrow & the Tin Woodman

from the Wizard of Oz series by L. Frank Baum (1900-1920)

propaganda (quotes from the books) below the cut

The Marvelous Land of Oz:

"I shall return with my friend the Tin Woodman," said the stuffed one, seriously. "We have decided never to be parted in the future."

Little Wizard Stories - The Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman:

"There lived in the Land of Oz two queerly made men who were the best of friends. They were so much happier when they were together that they were seldom apart."

The Tin Woodman of Oz:

"Beside [the Tin Woodman], in a chair of woven straw, sat his best friend, the Scarecrow of Oz. At times they spoke to one another of curious things they had seen and strange adventures they had known since first they two had met and become comrades. But at times they were silent, for these things had been talked over many times between them, and they found themselves contented in merely being together."

The Tin Woodman does not love his fiancée but feels obliged to marry her: "I believe it is my duty to set out and find her. Surely it is not the girl's fault that I no longer love her, and so, if I can make her happy, it is proper that I should do so."

After discovering that his fiancée had married someone else, he gladly returns home with "his chosen comrade, the Scarecrow."

#“friends of dorothy”#this started as a bit of a joke but honestly I've convinced myself while finding these quotes#the wizard of oz#l frank baum#oz series#tin woodman#tinman#scarecrow#< turns out that's also a batman character. whatever#polls#queer#classic literature#new post

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mystery of John Burr the Chestnut Man

The Land of Oz is a series with many an obscure characters - most people could probably tell you about Dorothy, the Tin-Man, the Lion, and the Scarecrow, but how many know of Ozma? Or Tik-Tok? What of Professor H.M. Wogglebug T.E.? And that's just scratching the surface, considering there are so many books (around 40 considered "Canonical"), and then beyond that there are characters who pop up in works connected to Oz... and then there's the case of John Burr the Chestnut Man. Who the Hell is he?

Well, first, some context:

In the year 1900, L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, complete with illustrations from W.W. Denslow. Due to their collaborative efforts on the book, it was agreed that both men should have the rights to the characters and various elements within the first book. This arrangement may sound a bit unusual, but really it should be fine as long as Denslow and Baum don't have some sort of falling out.

Guess what happened in 1902 while they were working on the Wizard of Oz Stage Musical?

So, Denslow and Baum went their separate ways, with Baum going on to write "The Marvelous Land of Oz", while Denslow continued illustrating for books such as "The Pearl and the Pumpkin". He also worked on a small book called "Denslow's Scarecrow and the Tin-Man", featuring a short story about the duo getting into some hijinx after deciding they were tired of working endlessly on the Wizard of Oz stage show - I'm sure he wasn't working through anything there.

Around the time Marvelous Land got published, he also worked on a newspaper series called "Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz" which served both to promote the sequel and increase the reach of the Oz brand. It's also one of the few remaining artefacts of a time when Baum really wanted Professor Wogglebug to be the mascot of the Oz series, but that's a discussion for another time.

Denslow sees this and thinks "Well, I'll show him! I'll make my own newspaper series!" and so we got Denslow’s Scarecrow and the Tin-Man (yes he used the same name as he did for the book - he also split that book into two halves and published them in the newspaper series, so that’s confusing). Unlike Baum's strip, this series mainly stuck to the events of the 1902 stage musical, so Dorothy never left Oz and is also referred to as Dorothy Gale (a name Baum wouldn't use in prose until Ozma of Oz) or Dotty (her show-exclusive nickname). The first story also makes reference to a Good Witch covering the poppy field with snow, which didn't happen in the book but did happen in the musical. Other than this though, they keep references deliberately vague - no mention is made of King Pastoria II, Cynthia Synch, or Dorothy’s pet cow, Imogene (who replaces Toto in the stage musical - similarly, this series makes no reference to Toto). It’s interesting to see an Oz-related work be influenced by a very popular adaptation other than the MGM movie.

Okay, but who is John Burr the Chestnut Man?

John Burr is introduced in the second story in the Scarecrow and Tin-Man series, and immediately he raises questions. Apparently, he's the Fairy Godfather of the Scarecrow (which possibly links him to the Scarecrow's 1902 musical origin wherein he comes to life because Dorothy wished for a friend, but this isn't made explicit) and possibly the Tin-Man. It's not clear. The Scarecrow and the Tin-Man are joined at the hip for most of this series though, so it hardly matters. In his first appearance, he transports the Scarecrow, Tin-Man, and the Cowardly Lion down to Earth, making him one of the most powerful characters in the series at this point.

Later in the series, he hands the Scarecrow and the Tin-Man "Magic Passes" because nobody will tell these poor guys how money works, so they just keep stealing things (relatedly, the Scarecrow and the Tin-Man book I mentioned earlier where they're performing in the musical mentions that the two just aren't paid for their work... again, I'm sure Denslow wasn't working through anything there)... and that's it. That's all we know of him. He enters the narrative, fulfils this oddly powerful role for someone who isn't even hinted at in anything prior and is then forgotten about entirely.

Also, he sells chestnuts, that's why he's the chestnut man.

[Honestly, the funniest thing about this whole situation to me is that Denslow's Scarecrow and the Tin-Man series is just significantly better than Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz - better art and the writing is just very charming - both are probably equally racist though, so be warned if you want to seek these out].

#Land of Oz#w w denslow#John Burr the Chestnut Man#l frank baum#mop's inane ramblings#the wizard of oz

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

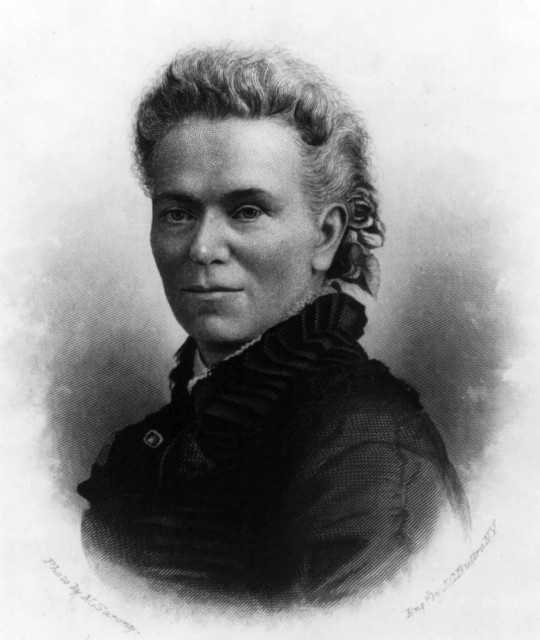

The Wizard of Oz series is centered around powerful girls and women, something unfortunately still unusual today. It was even more so when it was published in 1900. Matilda Joslyn Gage, was a huge influence on her son-in-law Frank Baum, and instrumental in the book being published.

The article below calls her a radical feminist, but they do NOT mean a terf.

They mean the same thing I thought the term meant when I first heard it - a fierce believer in feminism.

AFAIK there's no record of her ever mentioning trans people, but given her activism against organized religion as a source of prejudice, and for multiple oppressed groups of people, I definitely think she would have supported queer rights.

The Wizard of Oz film, and the novels that inspired it, were deeply influenced by the ideology of radical feminist Matilda Joslyn Gage. Gage may be best known as the mother-in-law of Oz novelist L. Frank Baum, but more importantly, she was an activist, who would be considered as radical in our day as she was in hers. “[Gage was] the woman who was ahead of the women who were ahead of their time,” Gloria Steinem said in Ms. Amongst her many accomplishments, Gage wrote the first three volumes of The History of Women’s Suffrage, alongside with her contemporaries, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Unlike these women, who both opposed the 15th Amendment, Gage sheltered runaway slaves in her childhood and married homes. In her final years, Gage became a treasured ally to local native American tribes, who adopted her as one of their own.

Mrs. Gage railed against religious leaders and politicians for a living and was so controversial and so scary to some that she was deemed ‘an infidel,’ her activities called ‘satanic.” That Gage is not better known to modern Americans is the result of deliberate actions taken by Anthony to distance the movement from Gage’s radical ideas, namely that the church’s hierarchies were inherently oppressive to women. As historian Sara Egge wrote, “Anthony in particular recognized that claiming her as central to the woman suffrage narrative was too dangerous.” Gage’s radicalism evidently rubbed off on her son-in-law. According to Schwartz, Baum became the outspoken secretary of his local Equal Suffrage Club, writing in a newspaper editorial, “We must do away with sex prejudice and render equal distinction and reward to brains and ability, no matter whether found in man or woman.”

Baum took inspiration from Gage’s politics, and in turn, she encouraged him to write down the spellbinding stories he told her grandchildren. In one instance, as Schwartz noted, Gage sent her son-in-law a newspaper ad for a story contest, writing on the enclosure, “Now you are a good writer and I advise you to try. Of course, you have but a little time, but ideas may flow.” In time, Baum would write The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, but in 1893, seven years before his book, Gage published Women, Church and State, a 500-page treatise which detailed why the church’s hierarchies were inherently oppressive to women. In a lengthy chapter titled “Witchcraft,” Gage argued the church affixed the label “witch” to any “wise, or learned woman,” a practice she traced from the middle ages to puritan Massachusetts.

Source. The bolding is mine.

I think Gage would have loved Elphaba! :)

ETA: I now love the name Gage for someone regardless of gender. :)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

the wonderful wizard of oz taken from the 1900 l. frank baum book.

there’s a cyclone coming.

are you a real witch?

tell me something about yourself, and the country you came from.

i could carry you in my basket.

you’ve had plenty of time already.

there are worse things in the world than being a scarecrow.

it was a good fight, friend.

don’t try, my dear.

i’m awfully sorry for you.

i see a little cottage at the right of us, built of logs and branches.

why don’t you run and jump?

if you come in this yard i will bite you.

one would almost suspect you had brains in your head, instead of straw.

my darling child! where in the world did you come from?

you’re more than that. you’re a humbug.

it must be inconvenient to be made of flesh, for you must sleep, and eat and drink.

run fast, and get out of this deadly flower-bed as soon as you can.

if you have, you ought to be glad, for it proves you have a heart.

there is no place like home.

i’ve been groaning for more than a year, and no one has ever heard me before or come to help me.

brains are the only things worth having in this world, no matter whether one is a crow or a man.

if you wish, i will go into the forest and kill a deer for you.

here is another space between the trees.

well, that’s respect, i expect.

experience is the only thing that brings knowledge, and the longer you are on earth the more experience you are sure to get.

all you need is confidence in yourself.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

New sounds ✨

REFERENTIAL rings in the new year with a 2 parter on the latest film adaptation of Act 1 of Wicked, just in time for the digital release!

For the musical nerds who'd find themselves awake at 2 am listening to Elphaba and Glinda riff and high note compilations

PART 1

Wicked - 'The Music'

Welcome back to the ‘Session of The Witch’!

[an ongoing miniseries of episodes diving into the resurgence of witches in pop culture fiction and their thematic relationship to this moment in feminism, womanhood, queerness, misogynoir (and musicals!]

I’m joined by returning guest Miss Sundi to talk about the 20 year history Wicked the musical and its most recent film adaptation!

Directed by Jon M. Chu, ‘Wicked: Part 1’ is a film adaptation starring Cynthia Erivo as Elphabaand Ariana Grande as Glinda..

The original musical featured music and lyrics by Stephan Schwartz, book by Winnie Holzmanand starred Idina Menzel as Elphaba and Kristin Chenoweth as Glinda. The musical itself was an adaptation of Gregory Macguire’s 1995 revisionist retelling of L. Frank Baum’s Wicked Witch of the West character (renamed Elphaba in tribute) from 1900’s Wonderful Wizard of Oz children’s novel.

Part 1 - 'The Music'

We recap of the story of Act 1 + a music commentary delving into the music of the musical track by track and note by note!

+

A recap

Mother Schwartz

The Glinda and Elphaba binary

Motifs

Glinda's double speak

Optional notes

Making Good

Jonathan Bailey is thriving

Back phrasing

High stamina 'I want' songs

LAR

Sharon D. Clarke

Fresher's week at Shiz

The Mics are on

Nessa Um Nessa

Madame Morrible's DBS

Men singing

Sopranos and Belters

BALLGOWN!

Mindful riffing

Lesbianism

Colours('Colors')

Musical Lesbianism

[Part 2 - 'The Movie'

A conversation about the history of the book, the shows musical origins and more of our thoughts on the recent film adaptation.]

___

This one is for the musical nerds who found themselves awake at 2 am listening to Elphaba and Glinda high note compilations.

___

Hosted and produced by Dr. Khaliden Nas.

Music by PamperedFists & Anzahlung.

All videos edited by Victor Alexander.

Podcast Artwork by Valentine M. Smith.

Keep up to date with Dr. Khaliden Nas by checking out www.alsopurple.com Follow me @AlsoPurp on all socials.

Find out more about REFERENTIAL’s upcoming episodes on www.alsopurple.com/citations

Thank you for listening!

Leave the pod a rating to help other people find the show!

#Ariana grande#Cynthia erivo#wicked#podcast#nessarose#madame morrible#the wizard of oz#dorothy gale#shiz#defying gravity#music commentary#reaction#review#recap#pop culture#idina menzel#kristin chenoweth#Jon chu#for good#movie#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Search of a Myth

Anthropologists have been complaining about the Myth of Barter for almost a century. Occasionally, economists point out with slight exasperation that there’s a fairly simple reason why they’re still telling the same story despite all the evidence against it: anthropologists have never come up with a better one.[72] This is an understandable objection, but there’s a simple answer to it. The reasons why anthropologists haven’t been able to come up with a simple, compelling story for the origins of money is because there’s no reason to believe there could be one. Money was no more ever “invented” than music or mathematics or jewelry. What we call “money” isn’t a “thing” at all, it’s a way of comparing things mathematically, as proportions: of saying one of X is equivalent to six of Y. As such it is probably as old as human thought. The moment we try to get any more specific, we discover that there are any number of different habits and practices that have converged in the stuff we now call “money,” and this is precisely the reason why economists, historians, and the rest have found it so difficult to come up with a single definition.

Credit Theorists have long been hobbled by the lack of an equally compelling narrative. This is not to say that all sides in the currency debates that ranged between 1850 and 1950 were not in the habit of deploying mythological weaponry. This was true particularly, perhaps, in the United States. In 1894, the Greenbackers, who pushed for detaching the dollar from gold entirely to allow the government to spend freely on job-creation campaigns, invented the idea of the March on Washington—an idea that was to have endless resonance in U.S. history. L. Frank Baum’s book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which appeared in 1900, is widely recognized to be a parable for the Populist campaign of William Jennings Bryan, who twice ran for president on the Free Silver platform—vowing to replace the gold standard with a bimetallic system that would allow the free creation of silver money alongside gold.[73] As with the Greenbackers, one of the main constituencies for the movement was debtors: particularly, Midwestern farm families such as Dorothy’s, who had been facing a massive wave of foreclosures during the severe recession of the 1890s. According to the Populist reading, the Wicked Witches of the East and West represent the East and West Coast bankers (promoters of and benefactors from the tight money supply), the Scarecrow represented the farmers (who didn’t have the brains to avoid the debt trap), the Tin Woodsman was the industrial proletariat (who didn’t have the heart to act in solidarity with the farmers), the Cowardly Lion represented the political class (who didn’t have the courage to intervene). The yellow brick road, silver slippers, emerald city, and hapless Wizard presumably speak for themselves.[74] “Oz” is of course the standard abbreviation for “ounce.”[75] As an attempt to create a new myth, Baum’s story was remarkably effective. As political propaganda, less so. William Jennings Bryan failed in three attempts to win the presidency, the silver standard was never adopted, and few nowadays even remember what The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was originally supposed to be about.[76]

For state-money theorists in particular, this has been a problem. Stories about rulers using taxes to create markets in conquered territories, or to pay for soldiers or other state functions, are not particularly inspiring. German ideas of money as the embodiment of national will did not travel very well.

Every time there was a major economic meltdown, however, conventional laissez-faire economics took another hit. The Bryan campaigns were born as a reaction to the Panic of 1893. By the time of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the very notion that the market could regulate itself, so long as the government ensured that money was safely pegged to precious metals, was completely discredited. From roughly 1933 to 1979, every major capitalist government reversed course and adopted some version of Keynesianism. Keynesian orthodoxy started from the assumption that capitalist markets would not really work unless capitalist governments were willing effectively to play nanny: most famously, by engaging in massive deficit “pump-priming” during downturns. While in the ’80s, Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the United States made a great show of rejecting all of this, it’s unclear how much they really did.[77] And in any case, they were operating in the wake of an even greater blow to previous monetary orthodoxy: Richard Nixon’s decision in 1971 to unpeg the dollar from precious metals entirely, eliminate the international gold standard, and introduce the system of floating currency regimes that has dominated the world economy ever since. This meant in effect that all national currencies were henceforth, as neoclassical economists like to put it, “fiat money” backed only by the public trust.

Now, John Maynard Keynes himself was much more open to what he liked to call the “alternative tradition” of credit and state theories than any economist of that stature (and Keynes is still arguably the single most important economic thinker of the twentieth century) before or since. At certain points he immersed himself in it: he spent several years in the 1920s studying Mesopotamian cuneiform banking records to try to ascertain the origins of money—his “Babylonian madness,” as he would later call it.[78] His conclusion, which he set forth at the very beginning of his Treatise on Money, his most famous work, was more or less the only conclusion one could come to if one started not from first principles, but from a careful examination of the historical record: that the lunatic fringe was, essentially, right. Whatever its earliest origins, for the last four thousand years, money has been effectively a creature of the state. Individuals, he observed, make contracts with one another. They take out debts, and they promise payment.

The State, therefore, comes in first of all as the authority of law which enforces the payment of the thing which corresponds to the name or description in the contract. But it comes doubly when, in addition, it claims the right to determine and declare what thing corresponds to the name, and to vary its declaration from time to time—when, that is to say it claims the right to re-edit the dictionary. This right is claimed by all modern States and has been so claimed for some four thousand years at least. It is when this stage in the evolution of Money has been reached that Knapp’s Chartalism—the doctrine that money is peculiarly a creation of the State—is fully realized … To-day all civilized money is, beyond the possibility of dispute, chartalist.[79]

This does not mean that the state necessarily creates money. Money is credit, it can be brought into being by private contractual agreements (loans, for instance). The state merely enforces the agreement and dictates the legal terms. Hence Keynes’ next dramatic assertion: that banks create money, and that there is no intrinsic limit to their ability to do so: since however much they lend, the borrower will have no choice but to put the money back into some bank again, and thus, from the perspective of the banking system as a whole, the total number of debits and credits will always cancel out.[80] The implications were radical, but Keynes himself was not. In the end, he was always careful to frame the problem in a way that could be reintegrated into the mainstream economics of his day.

Neither was Keynes much of a mythmaker. Insofar as the alternative tradition has come up with an answer to the Myth of Barter, it was not from Keynes’ own efforts (Keynes ultimately decided that the origins of money were not particularly important) but in the work of some contemporary neo-Keynesians, who were not afraid to follow some of his more radical suggestions as far as they would go.

The real weak link in state-credit theories of money was always the element of taxes. It is one thing to explain why early states demanded taxes (in order to create markets.) It’s another to ask “by what right?” Assuming that early rulers were not simply thugs, and that taxes were not simply extortion—and no Credit Theorist, to my knowledge, took such a cynical view even of early government—one must ask how they justified this sort of thing.

Nowadays, we all think we know the answer to this question. We pay our taxes so that the government can provide us with services. This starts with security services—military protection being, often, about the only service some early states were really able to provide. By now, of course, the government provides all sorts of things. All of this is said to go back to some sort of original “social contract” that everyone somehow agreed on, though no one really knows exactly when or by whom, or why we should be bound by the decisions of distant ancestors on this one matter when we don’t feel particularly bound by the decisions of our distant ancestors on anything else.[81] All of this makes sense if you assume that markets come before governments, but the whole argument totters quickly once you realize that they don’t.

There is an alternative explanation, one created to be in keeping with the state-credit theory approach. It’s referred to as “primordial debt theory” and it has been developed largely in France, by a team of researchers—not only economists but anthropologists, historians, and classicists—originally assembled around the figures of Michel Aglietta and Andre Orléans,[82] and more recently, Bruno Théret, and it has since been taken up by neo-Keynesians in the United States and the United Kingdom as well.[83]

It’s a position that has emerged quite recently, and at first, largely amidst debates about the nature of the euro. The creation of a common European currency sparked not only all sorts of intellectual debates (does a common currency necessarily imply the creation of a common European state? Or of a common European economy or society? Are these ultimately the same thing?) but dramatic political ones as well. The creation of the euro zone was spearheaded above all by Germany, whose central banks still see their main goal as combating inflation. What’s more, tight money policies and the need to balance budgets having been used as the main weapon to chip away welfare-state policies in Europe, it has necessarily become the stake of political struggles between bankers and pensioners, creditors and debtors, just as heated as those of 1890s America.

The core argument is that any attempt to separate monetary policy from social policy is ultimately wrong. Primordial-debt theorists insist that these have always been the same thing. Governments use taxes to create money, and they are able to do so because they have become the guardians of the debt that all citizens have to one another. This debt is the essence of society itself. It exists long before money and markets, and money and markets themselves are simply ways of chopping pieces of it up.

At first, the argument goes, this sense of debt was expressed not through the state, but through religion. To make the argument, Aglietta and Orléans fixed on certain works of early Sanskrit religious literature: the hymns, prayers, and poetry collected in the Vedas and the Brahmanas, priestly commentaries composed over the centuries that followed, texts that are now considered the foundations of Hindu thought. It’s not as odd a choice as it might seem. These texts constitute the earliest known historical reflections on the nature of debt.

Actually, even the very earliest Vedic poems, composed sometime between 1500 and 1200 bc, evince a constant concern with debt—which is treated as synonymous with guilt and sin.[84] There are numerous prayers pleading with the gods to liberate the worshipper from the shackles or bonds of debt. Sometimes these seem to refer to debt in the literal sense—Rig Veda 10.34, for instance, has a long description of the sad plight of gamblers who “wander homeless, in constant fear, in debt, and seeking money.” Elsewhere it’s clearly metaphorical.

In these hymns, Yama, the god of death, figures prominently. To be in debt was to have a weight placed on you by Death. To be under any sort of unfulfilled obligation, any unkept promise, to gods or to men, was to live in the shadow of Death. Often, even in the very early texts, debt seems to stand in for a broader sense of inner suffering, from which one begs the gods—particularly Agni, who represents the sacrificial fire—for release. It was only with the Brahmanas that commentators started trying to weave all this together into a more comprehensive philosophy. The conclusion: that human existence is itself a form of debt.

A man, being born, is a debt; by his own self he is born to Death, and only when he sacrifices does he redeem himself from Death.[85]

Sacrifice (and these early commentators were themselves sacrificial priests) is thus called “tribute paid to Death.” Or such was the manner of speaking. In reality, as the priests knew better than anyone, sacrifice was directed to all the gods, not just Death—Death was just the intermediary. Framing things this way, though, did immediately raise the one problem that always comes up, whenever anyone conceives human life through such an idiom. If our lives are on loan, who would actually wish to repay such a debt? To live in debt is to be guilty, incomplete. But completion can only mean annihilation. In this way, the “tribute” of sacrifice could be seen as a kind of interest payment, with the life of the animal substituting temporarily for what’s really owed, which is ourselves—a mere postponement of the inevitable.[86]

Different commentators proposed different ways out of the dilemma. Some ambitious Brahmins began telling their clients that sacrificial ritual, if done correctly, promised a way to break out of the human condition entirely and achieve eternity (since, in the face of eternity, all debts become meaningless.)[87] Another way was to broaden the notion of debt, so that all social responsibilities become debts of one sort or another. Thus two famous passages in the Brahmanas insist that we are born as a debt not just to the gods, to be repaid in sacrifice, but also to the Sages who created the Vedic learning to begin with, which we must repay through study; to our ancestors (“the Fathers”), who we must repay by having children; and finally, “to men”—apparently meaning humanity as a whole, to be repaid by offering hospitality to strangers.[88] Anyone, then, who lives a proper life is constantly paying back existential debts of one sort or another; but at the same time, as the notion of debt slides back into a simple sense of social obligation, it becomes something far less terrifying than the sense that one’s very existence is a loan taken against Death.[89] Not least because social obligations always cut both ways. Especially since, once one has oneself fathered children, one is just as much a debtor as a creditor.

What primordial-debt theorists have done is to propose that the ideas encoded in these Vedic texts are not peculiar to a certain intellectual tradition of early Iron Age ritual specialists in the Ganges valley, but that they are essential to the very nature and history of human thought. Consider for example this statement, from an essay by French economist Bruno Théret with the uninspiring title “The Socio-Cultural Dimensions of the Currency: Implications for the Transition to the Euro,” published in the Journal of Consumer Policy in 1999:

At the origin of money we have a “relation of representation” of death as an invisible world, before and beyond life—a representation that is the product of the symbolic function proper to the human species and which envisages birth as an original debt incurred by all men, a debt owing to the cosmic powers from which humanity emerged.

Payment of this debt, which can however never be settled on earth—because its full reimbursement is out of reach—takes the form of sacrifices which, by replenishing the credit of the living, make it possible to prolong life and even in certain cases to achieve eternity by joining the Gods. But this initial belief-claim is also associated with the emergence of sovereign powers whose legitimacy resides in their ability to represent the entire original cosmos. And it is these powers that invented money as a means of settling debts—a means whose abstraction makes it possible to resolve the sacrificial paradox by which putting to death becomes the permanent means of protecting life. Through this institution, belief is in turn transferred to a currency stamped with the effigy of the sovereign—a money put in circulation but whose return is organized by this other institution which is the tax/settlement of the life debt. So money also takes on the function of a means of payment.[90]

If nothing else, this provides a neat illustration of how different are standards of debate in Europe from those current in the Anglo-American world. One can’t imagine an American economist of any stripe writing something like this. Still, the author is actually making a rather clever synthesis here. Human nature does not drive us to “truck and barter.” Rather, it ensures that we are always creating symbols—such as money itself. This is how we come to see ourselves in a cosmos surrounded by invisible forces; as in debt to the universe.

The ingenious move of course is to fold this back into the state theory of money—since by “sovereign powers” Théret actually means “the state.” The first kings were sacred kings who were either gods in their own right or stood as privileged mediators between human beings and the ultimate forces that governed the cosmos. This sets us on a road to the gradual realization that our debt to the gods was always, really, a debt to the society that made us what we are.

The “primordial debt,” writes British sociologist Geoffrey Ingham, “is that owed by the living to the continuity and durability of the society that secures their individual existence.”[91] In this sense it is not just criminals who owe a “debt to society”—we are all, in a certain sense, guilty, even criminals.

For instance, Ingham notes that, while there is no actual proof that money emerged in this way, “there is considerable indirect etymological evidence”:

In all Indo-European languages, words for “debt” are synonymous with those for “sin” or “guilt”, illustrating the links between religion, payment and the mediation of the sacred and profane realms by “money.” For example, there is a connection between money (German Geld), indemnity or sacrifice (Old English Geild), tax (Gothic Gild) and, of course, guilt.[92]

Or, to take another curious connection: Why were cattle so often used as money? The German historian Bernard Laum long ago pointed out that in Homer, when people measure the value of a ship or suit of armor, they always measure it in oxen—even though when they actually exchange things, they never pay for anything in oxen. It is hard to escape the conclusion that this was because an ox was what one offered the gods in sacrifice. Hence they represented absolute value. From Sumer to Classical Greece, silver and gold were dedicated as offerings in temples. Everywhere, money seems to have emerged from the thing most appropriate for giving to the gods.[93]

If the king has simply taken over guardianship of that primordial debt we all owe to society for having created us, this provides a very neat explanation for why the government feels it has the right to make us pay taxes. Taxes are just a measure of our debt to the society that made us. But this doesn’t really explain how this kind of absolute life-debt can be converted into money, which is by definition a means of measuring and comparing the value of different things. This is just as much a problem for credit theorists as for neoclassical economists, even if the problem for them is somewhat differently framed. If you start from the barter theory of money, you have to resolve the problem of how and why you would come to select one commodity to measure just how much you want each of the other ones. If you start from a credit theory, you are left with the problem I described in the first chapter: how to turn a moral obligation into a specific sum of money, how the mere sense of owing someone else a favor can eventually turn into a system of accounting in which one is able to calculate exactly how many sheep or fish or chunks of silver it would take to repay the debt. Or in this case, how do we go from that absolute debt we owe to God to the very specific debts we owe our cousins, or the bartender?

The answer provided by primordial-debt theorists is, again, ingenious. If taxes represent our absolute debt to the society that created us, then the first step toward creating real money comes when we start calculating much more specific debts to society, systems of fines, fees, and penalties, or even debts we owe to specific individuals who we have wronged in some way, and thus to whom we stand in a relation of “sin” or “guilt.”

This is actually much less implausible than it might sound. One of the puzzling things about all the theories about the origins of money that we’ve been looking at so far is that they almost completely ignore the evidence of anthropology. Anthropologists do have a great deal of knowledge of how economies within stateless societies actually worked—how they still work in places where states and markets have been unable to completely break up existing ways of doing things. There are innumerable studies of, say, the use of cattle as money in eastern or southern Africa, of shell money in the Americas (wampum being the most famous example) or Papua New Guinea, bead money, feather money, the use of iron rings, cowries, spondylus shells, brass rods, or woodpecker scalps.[94] The reason that this literature tends to be ignored by economists is simple: “primitive currencies” of this sort is only rarely used to buy and sell things, and even when they are, never primarily to buy and sell everyday items such as chickens or eggs or shoes or potatoes. Rather than being employed to acquire things, they are mainly used to rearrange relations between people. Above all, to arrange marriages and to settle disputes, particularly those arising from murders or personal injury.

There is every reason to believe that our own money started the same way—even the English word “to pay” is originally derived from a word for “to pacify, appease”—as in, to give someone something precious, for instance, to express just how badly you feel about having just killed his brother in a drunken brawl, and how much you would really like to avoid this becoming the basis for an ongoing blood-feud.[95]

Debt theorists are especially concerned with this latter possibility. This is partly because they tend to skip past the anthropological literature and look at early law codes—taking inspiration here, from the groundbreaking work of one of the twentieth century’s greatest numismatists, Philip Grierson, who in the ’70s, first suggested that money might first have emerged from early legal practice. Grierson was an expert in the European Dark Ages, and he became fascinated by what have come to be known as the “Barbarian Law Codes,” established by many Germanic peoples after the destruction of the Roman Empire in the 600s and 700s—Goths, Frisians, Franks, and so on—soon followed by similar codes published everywhere from Russia to Ireland. Certainly they are fascinating documents. On the one hand, they make it abundantly clear just how wrong are conventional accounts of Europe around this time “reverting to barter.” Almost all of the Germanic law codes use Roman money to make assessments; penalties for theft, for instance, are almost always followed by demands that the thief not only return the stolen property but pay any outstanding rent (or in the event of stolen money, interest) owing for the amount of time it has been in his possession. On the other hand, these were soon followed by law codes by people living in territories that had never been under Roman rule—in Ireland, Wales, Nordic countries, Russia—and these are if anything even more revealing. They could be remarkably creative, both in what could be used as a means of payment and on the precise breakdown of injuries and insults that required compensation:

Compensation in the Welsh laws is reckoned primarily in cattle and in the Irish ones in cattle or bondmaids (cumal), with considerable use of precious metals in both. In the Germanic codes it is mainly in precious metal … In the Russian codes it was silver and furs, graduated from marten down to squirrel. Their detail is remarkable, not only in the personal injuries envisioned—specific compensations for the loss of an arm, a hand, a forefinger, a nail, for a blow on the head so that the brain is visible or bone projects—but in the coverage some of them gave to the possessions of the individual household. Title II of the Salic Law deals with the theft of pigs, Title III with cattle, Title IV with sheep, Title V with goats, Title VI with dogs, each time with an elaborate breakdown differentiating between animals of different age and sex.[96]

This does make a great deal of psychological sense. I’ve already remarked how difficult it is to imagine how a system of precise equivalences—one young healthy milk cow is equivalent to exactly thirty-six chickens—could arise from most forms of gift exchange. If Henry gives Joshua a pig and feels he has received an inadequate counter-gift, he might mock Joshua as a cheapskate, but he would have little occasion to come up with a mathematical formula for precisely how cheap he feels Joshua has been. On the other hand, if Joshua’s pig just destroyed Henry’s garden, and especially, if that led to a fight in which Henry lost a toe, and Henry’s family is now hauling Joshua up in front of the village assembly—this is precisely the context where people are most likely to become petty and legalistic and express outrage if they feel they have received one groat less than was their rightful due. That means exact mathematical specificity: for instance, the capacity to measure the exact value of a two-year-old pregnant sow. What’s more, the levying of penalties must have constantly required the calculation of equivalences. Say the fine is in marten pelts but the culprit’s clan doesn’t have any martens. How many squirrel skins will do? Or pieces of silver jewelry? Such problems must have come up all the time and led to at least a rough-and-ready set of rules of thumb over what sorts of valuable were equivalent to others. This would help explain why, for instance, medieval Welsh law codes can contain detailed breakdowns not only of the value of different ages and conditions of milk cow, but of the monetary value of every object likely to be found in an ordinary homestead, down to the cost of each piece of timber—despite the fact that there seems no reason to believe that most such items could even be purchased on the open market at the time.[97]

There is something very compelling in all this. For one thing, the premise makes a great deal of intuitive sense. After all, we do owe everything we are to others. This is simply true. The language we speak and even think in, our habits and opinions, the kind of food we like to eat, the knowledge that makes our lights switch on and toilets flush, even the style in which we carry out our gestures of defiance and rebellion against social conventions—all of this, we learned from other people, most of them long dead. If we were to imagine what we owe them as a debt, it could only be infinite. The question is: Does it really make sense to think of this as a debt? After all, a debt is by definition something that we could at least imagine paying back. It is strange enough to wish to be square with one’s parents—it rather implies that one does not wish to think of them as parents any more. Would we really want to be square with all humanity? What would that even mean? And is this desire really a fundamental feature of all human thought?

Another way to put this would be: Are primordial-debt theorists describing a myth, have they discovered a profound truth of the human condition that has always existed in all societies, and is it simply spelled out particularly clearly in certain ancient texts from India—or are they inventing a myth of their own?

Clearly it must be the latter. They are inventing a myth.

The choice of the Vedic material is significant. The fact is, we know almost nothing about the people who composed these texts and little about the society that created them.[98] We don’t even know if interest-bearing loans existed in Vedic India—which obviously has a bearing on whether priests really saw sacrifice as the payment of interest on a loan we owe to Death.[99] As a result, the material can serve as a kind of empty canvas, or a canvas covered with hieroglyphics in an unknown language, on which we can project almost anything we want to. If we look at other ancient civilizations in which we do know something about the larger context, we find that no such notion of sacrifice as payment is in evidence.[100] If we look through the work of ancient theologians, we find that most were familiar with the idea that sacrifice was a way by which human beings could enter into commercial relations with the gods, but that they felt it was patently ridiculous: If the gods already have everything they want, what exactly do humans have to bargain with?[101] We’ve seen in the last chapter how difficult it is to give gifts to kings. With gods (let alone God) the problem is magnified infinitely. Exchange implies equality. In dealing with cosmic forces, this was simply assumed to be impossible from the start.

The notion that debts to gods were appropriated by the state, and thus became the bases for taxation systems, can’t really stand up either. The problem here is that in the ancient world, free citizens didn’t usually pay taxes. Generally speaking, tribute was levied only on conquered populations. This was already true in ancient Mesopotamia, where the inhabitants of independent cities did not usually have to pay direct taxes at all. Similarly, as Moses Finley put it, “Classical Greeks looked upon direct taxes as tyrannical and avoided them whenever possible.[102] Athenian citizens did not pay direct taxes of any sort; though the city did sometimes distribute money to its citizens, a kind of reverse taxation—sometimes directly, as with the proceeds of the Laurium silver mines, and sometimes indirectly, as through generous fees for jury duty or attending the assembly. Subject cities, however, did have to pay tribute. Even within the Persian Empire, Persians did not have to pay tribute to the Great King, but the inhabitants of conquered provinces did.[103] The same was true in Rome, where for a very long time, Roman citizens not only paid no taxes but had a right to a share of the tribute levied on others, in the form of the dole—the “bread” part of the famous “bread and circuses.”[104]

In other words, Benjamin Franklin was wrong when he said that in this world nothing is certain except death and taxes. This obviously makes the idea that the debt to one is just a variation on the other much harder to maintain.

None of this, however, deals a mortal blow to the state theory of money. Even those states that did not demand taxes did levy fees, penalties, tariffs, and fines of one sort or another. But it is very hard to reconcile with any theory that claims states were first conceived as guardians of some sort of cosmic, primordial debt.

It’s curious that primordial-debt theorists never have much to say about Sumer or Babylonia, despite the fact that Mesopotamia is where the practice of loaning money at interest was first invented, probably two thousand years before the Vedas were composed—and that it was also the home of the world’s first states. But if we look into Mesopotamian history, it becomes a little less surprising. Again, what we find there is in many ways the exact opposite of what such theorists would have predicted.

The reader will recall here that Mesopotamian city-states were dominated by vast Temples: gigantic, complex industrial institutions often staffed by thousands—including everyone from shepherds and barge-pullers to spinners and weavers to dancing girls and clerical administrators. By at least 2700 bc, ambitious rulers had begun to imitate them by creating palace complexes organized on similar terms—with the exception that where the Temples centered on the sacred chambers of a god or goddess, represented by a sacred image who was fed and clothed and entertained by priestly servants as if he or she were a living person. Palaces centered on the chambers of an actual live king. Sumerian rulers rarely went so far as to declare themselves gods, but they often came very close. However, when they did interfere in the lives of their subjects in their capacity as cosmic rulers, they did not do it by imposing public debts, but rather by canceling private ones.[105]

We don’t know precisely when and how interest-bearing loans originated, since they appear to predate writing. Most likely, Temple administrators invented the idea as a way of financing the caravan trade. This trade was crucial because while the river valley of ancient Mesopotamia was extraordinarily fertile and produced huge surpluses of grain and other foodstuffs, and supported enormous numbers of livestock, which in turn supported a vast wool and leather industry, it was almost completely lacking in anything else. Stone, wood, metal, even the silver used as money, all had to be imported. From quite early times, then, Temple administrators developed the habit of advancing goods to local merchants—some of them private, others themselves Temple functionaries—who would then go off and sell it overseas. Interest was just a way for the Temples to take their share of the resulting profits.[106] However, once established, the principle seems to have quickly spread. Before long, we find not only commercial loans, but also consumer loans—usury in the classical sense of the term. By c2400 bc it already appears to have been common practice on the part of local officials, or wealthy merchants, to advance loans to peasants who were in financial trouble on collateral and begin to appropriate their possessions if they were unable to pay. It usually started with grain, sheep, goats, and furniture, then moved on to fields and houses, or, alternately or ultimately, family members. Servants, if any, went quickly, followed by children, wives, and in some extreme occasions, even the borrower himself. These would be reduced to debt-peons: not quite slaves, but very close to that, forced into perpetual service in the lender’s household—or, sometimes, in the Temples or Palaces themselves. In theory, of course, any of them could be redeemed whenever the borrower repaid the money, but for obvious reasons, the more a peasant’s resources were stripped away from him, the harder that became.

The effects were such that they often threatened to rip society apart. If for any reason there was a bad harvest, large proportions of the peasantry would fall into debt peonage; families would be broken up. Before long, lands lay abandoned as indebted farmers fled their homes for fear of repossession and joined semi-nomadic bands on the desert fringes of urban civilization. Faced with the potential for complete social breakdown, Sumerian and later Babylonian kings periodically announced general amnesties: “clean slates,” as economic historian Michael Hudson refers to them. Such decrees would typically declare all outstanding consumer debt null and void (commercial debts were not affected), return all land to its original owners, and allow all debt-peons to return to their families. Before long, it became more or less a regular habit for kings to make such a declaration on first assuming power, and many were forced to repeat it periodically over the course of their reigns.

In Sumeria, these were called “declarations of freedom”—and it is significant that the Sumerian word amargi, the first recorded word for “freedom” in any known human language, literally means “return to mother”—since this is what freed debt-peons were finally allowed to do.[107]

Michael Hudson argues that Mesopotamian kings were only in a position to do this because of their cosmic pretensions: in taking power, they saw themselves as literally recreating human society, and so were in a position to wipe the slate clean of all previous moral obligations. Still, this is about as far from what primordial-debt theorists had in mind as one could possibly imagine.[108]

Probably the biggest problem in this whole body of literature is the initial assumption: that we begin with an infinite debt to something called “society.” It’s this debt to society that we project onto the gods. It’s this same debt that then gets taken up by kings and national governments.

What makes the concept of society so deceptive is that we assume the world is organized into a series of compact, modular units called “societies,” and that all people know which one they’re in. Historically, this is very rarely the case. Imagine I am a Christian Armenian merchant living under the reign of Genghis Khan. What is “society” for me? Is it the city where I grew up, the society of international merchants (with its own elaborate codes of conduct) within which I conduct my daily affairs, other speakers of Armenian, Christendom (or maybe just Orthodox Christendom), or the inhabitants of the Mongol empire itself, which stretched from the Mediterranean to Korea? Historically, kingdoms and empires have rarely been the most important reference points in peoples’ lives. Kingdoms rise and fall; they also strengthen and weaken; governments may make their presence known in people’s lives quite sporadically, and many people in history were never entirely clear whose government they were actually in. Even until quite recently, many of the world’s inhabitants were never even quite sure what country they were supposed to be in, or why it should matter. My mother, who was born a Jew in Poland, once told me a joke from her childhood:

There was a small town located along the frontier between Russia and Poland; no one was ever quite sure to which it belonged. One day an official treaty was signed and not long after, surveyors arrived to draw a border. Some villagers approached them where they had set up their equipment on a nearby hill.

“So where are we, Russia or Poland?”

“According to our calculations, your village now begins exactly thirty-seven meters into Poland.”

The villagers immediately began dancing for joy.

“Why?” the surveyors asked. “What difference does it make?”

“Don’t you know what this means?” they replied. “It means we’ll never have to endure another one of those terrible Russian winters!”

However, if we are born with an infinite debt to all those people who made our existence possible, but there is no natural unit called “society”—then who or what exactly do we really owe it to? Everyone? Everything? Some people or things more than others? And how do we pay a debt to something so diffuse? Or, perhaps more to the point, who exactly can claim the authority to tell us how we can repay it, and on what grounds?

If we frame the problem that way, the authors of the Brahmanas are offering a quite sophisticated reflection on a moral question that no one has really ever been able to answer any better before or since. As I say, we can’t know much about the conditions under which those texts were composed, but such evidence as we do have suggests that the crucial documents date from sometime between 500 and 400 bc—that is, roughly the time of Socrates—which in India appears to have been just around the time that a commercial economy, and institutions like coined money and interest-bearing loans were beginning to become features of everyday life. The intellectual classes of the time were, much as they were in Greece and China, grappling with the implications. In their case, this meant asking: What does it mean to imagine our responsibilities as debts? To whom do we owe our existence?

It’s significant that their answer did not make any mention either of “society” or states (though certainly kings and governments certainly existed in early India). Instead, they fixed on debts to gods, to sages, to fathers, and to “men.” It wouldn’t be at all difficult to translate their formulation into more contemporary language. We could put it this way. We owe our existence above all:

• To the universe, cosmic forces, as we would put it now, to Nature. The ground of our existence. To be repaid through ritual: ritual being an act of respect and recognition to all that beside which we are small.[109]

• To those who have created the knowledge and cultural accomplishments that we value most; that give our existence its form, its meaning, but also its shape. Here we would include not only the philosophers and scientists who created our intellectual tradition but everyone from William Shakespeare to that long-since-forgotten woman, somewhere in the Middle East, who created leavened bread. We repay them by becoming learned ourselves and contributing to human knowledge and human culture.

• To our parents, and their parents—our ancestors. We repay them by becoming ancestors.

• To humanity as a whole. We repay them by generosity to strangers, by maintaining that basic communistic ground of sociality that makes human relations, and hence life, possible.

Set out this way, though, the argument begins to undermine its very premise. These are nothing like commercial debts. After all, one might repay one’s parents by having children, but one is not generally thought to have repaid one’s creditors if one lends the cash to someone else.[110]

Myself, I wonder: Couldn’t that really be the point? Perhaps what the authors of the Brahmanas were really demonstrating was that, in the final analysis, our relation with the cosmos is ultimately nothing like a commercial transaction, nor could it be. That is because commercial transactions imply both equality and separation. These examples are all about overcoming separation: you are free from your debt to your ancestors when you become an ancestor; you are free from your debt to the sages when you become a sage, you are free from your debt to humanity when you act with humanity. All the more so if one is speaking of the universe. If you cannot bargain with the gods because they already have everything, then you certainly cannot bargain with the universe, because the universe is everything—and that everything necessarily includes yourself. One could in fact interpret this list as a subtle way of saying that the only way of “freeing oneself” from the debt was not literally repaying debts, but rather showing that these debts do not exist because one is not in fact separate to begin with, and hence that the very notion of canceling the debt, and achieving a separate, autonomous existence, was ridiculous from the start. Or even that the very presumption of positing oneself as separate from humanity or the cosmos, so much so that one can enter into one-to-one dealings with it, is itself the crime that can be answered only by death. Our guilt is not due to the fact that we cannot repay our debt to the universe. Our guilt is our presumption in thinking of ourselves as being in any sense an equivalent to Everything Else that Exists or Has Ever Existed, so as to be able to conceive of such a debt in the first place.[111]

Or let us look at the other side of the equation. Even if it is possible to imagine ourselves as standing in a position of absolute debt to the cosmos, or to humanity, the next question becomes: Who exactly has a right to speak for the cosmos, or humanity, to tell us how that debt must be repaid? If there’s anything more preposterous than claiming to stand apart from the entire universe so as to enter into negotiations with it, it is claiming to speak for the other side.

If one were looking for the ethos for an individualistic society such as our own, one way to do it might well be to say: we all owe an infinite debt to humanity, society, nature, or the cosmos (however one prefers to frame it), but no one else could possibly tell us how we are to pay it. This at least would be intellectually consistent. If so, it would actually be possible to see almost all systems of established authority—religion, morality, politics, economics, and the criminal-justice system—as so many different fraudulent ways to presume to calculate what cannot be calculated, to claim the authority to tell us how some aspect of that unlimited debt ought to be repaid. Human freedom would then be our ability to decide for ourselves how we want to do so.

No one, to my knowledge, has ever taken this approach. Instead, theories of existential debt always end up becoming ways of justifying—or laying claim to—structures of authority. The case of the Hindu intellectual tradition is telling here. The debt to humanity appears only in a few early texts, and is quickly forgotten. Almost all later Hindu commentators ignore it and instead put their emphasis on a man’s debt to his father.[112]

Primordial-debt theorists have other fish to fry. They are not really interested in the cosmos, but actually, in “society.”

Let me return again to that word, “society.” The reason that it seems like such a simple, self-evident concept is because we mostly use it as a synonym for “nation.” After all, when Americans speak of paying their debt to society, they are not thinking of their responsibilities to people who live in Sweden. It’s only the modern state, with its elaborate border controls and social policies, that enables us to imagine “society” in this way, as a single bounded entity. This is why projecting that notion backwards into Vedic or Medieval times will always be deceptive, even though we don’t really have another word.

It seems to me that this is exactly what the primordial-debt theorists are doing: projecting such a notion backwards.

Really, the whole complex of ideas they are talking about—the notion that there is this thing called society, that we have a debt to it, that governments can speak for it, that it can be imagined as a sort of secular god—all of these ideas emerged together around the time of the French Revolution, or in its immediate wake. In other words, it was born alongside the idea of the modern nation-state.

We can already see them coming together clearly in the work of Auguste Comte, in early nineteenth-century France. Comte, a philosopher and political pamphleteer now most famous for having first coined the term “sociology,” went so far, by the end of his life, as actually proposing a Religion of Society, which he called Positivism, broadly modeled on Medieval Catholicism, replete with vestments where all the buttons were on the back (so they couldn’t be put on without the help of others). In his last work, which he called a “Positivist Catechism,” he also laid down the first explicit theory of social debt. At one point someone asks an imaginary Priest of Positivism what he thinks of the notion of human rights. The priest scoffs at the very idea. This is nonsense, he says, an error born of individualism. Positivism understands only duties. After all:

We are born under a load of obligations of every kind, to our predecessors, to our successors, to our contemporaries. After our birth these obligations increase or accumulate before the point where we are capable of rendering anyone any service. On what human foundation, then, could one seat the idea of “rights”?[113]

While Comte doesn’t use the word “debt,” the sense is clear enough. We have already accumulated endless debts before we get to the age at which we can even think of paying them. By that time, there’s no way to calculate to whom we even owe them. The only way to redeem ourselves is to dedicate ourselves to the service of Humanity as a whole.

In his lifetime, Comte was considered something of a crackpot, but his ideas proved influential. His notion of unlimited obligations to society ultimately crystallized in the notion of the “social debt,” a notion taken up among social reformers and, eventually, socialist politicians in many parts of Europe and abroad.[114] “We are all born as debtors to society”: in France the notion of a social debt soon became something of a catchphrase, a slogan, and eventually a cliché.[115] The state, according to this view, was merely the administrator of an existential debt that all of us have to the society that created us, embodied not least in the fact that we all continue to be completely dependent on one another for our existence, even if we are not completely aware of how.

These are also the intellectual and political circles that shaped the thought of Emile Durkheim, the founder of the discipline of sociology that we know today, who in a way did Comte one better by arguing that all gods in all religions are always already projections of society—so an explicit religion of society would not even be necessary. All religions, for Durkheim, are simply ways of recognizing our mutual dependence on one another, a dependence that affects us in a million ways that we are never entirely aware of. “God” and “society” are ultimately the same.