#french government scholarship

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Usually when an English speaker is getting into the history of the French Revolution and wants to go beyond Wikipedia, they stumble on The Twelve Who Ruled. It’s inevitable. Since 1941 it has been a staple of lecture halls and history aficionados alike.

For me it was one of the first things I read, many years ago, and it shaped, to some extent, how I approached the period. I read it again last year, expecting to see it differently. I didn’t. It’s an old book. But still, by the standards of 21st-century historiography, largely accurate.

So since it’s a book a lot of beginners encounter, and since I’ve had half a mind to review some of the dozens of books on the French Revolution I own, I thought it would be a good place to start.

I will be assessing this book (and all others I review) on a scale from 1 to 5 in eight categories:

Before we start, remember two things:

This is my review, which means it is, by definition, biased. I try to stay as neutral as possible, but no one is fully objective.

You should never take anything as fact. I research things. I enjoy researching things. I spend far too much time researching things. But I’m human, and that means I make mistakes. Challenge everything you read, including this.

Twelve Who Ruled: An In-depth Review

Historical Accuracy

For a book published in the 1940s, Twelve Who Ruled is remarkable in how much of it remains uncontested, especially given that archival access in France was impossible during the war. Using only the printed sources available to him, Palmer built a richly detailed narrative of Year II. He avoided major factual errors and did not indulge in the lurid exaggerations or mythologising that often plagued earlier accounts of the Revolution.

On the contrary, Palmer’s portraits of key figures and events have stood the test of time. His depiction of Robespierre, for example, was unmatched in its balance, nuance and restraint when the book was published. Subsequent scholarship has generally confirmed Palmer’s factual claims. Indeed, many of his interpretations have been validated by later evidence: for instance, he is one of the first to advance the argument that the Terror’s policies were reactive responses to severe crises, rather than a premeditated program of mass violence, and that Robespierre never exercised dictatorial authority.

Eighty years later, Twelve Who Ruled still holds up as a factually sound work. Far from perpetuating discredited myths, Palmer steered a middle course, avoiding both Thermidorian clichés about a “blood-mad” Committee and hagiographic Jacobin legends.

Historiographical Position

When situating The Twelve Who Ruled within the landscape of French Revolution historiography, it is important to remember that Palmer was writing in 1941, before most of the major scholarly camps had fully taken shape. His work does not fit neatly into the classic categories of Marxist, Revisionist, or post-Revisionist schools (1), though it engaged with and later influenced those debates.

Palmer’s approach was essentially a liberal narrative of the Revolution’s most turbulent phase. He focused on the pragmatic demands of governance during an existential crisis, rather than on class struggle or ideological abstraction. This already set him apart from the Marxist tradition. His attention remained squarely on the actions and dilemmas of the twelve men on the Committee of Public Safety, and on the political and military pressures that shaped their decisions.

He also diverged from what would later become the Revisionist school. While Palmer shared their scepticism of class determinism, he did not embrace their emphasis on ideology as the primary driver. His account treats the Terror less as a product of revolutionary rhetoric than as a contingent response to internal collapse and foreign invasion. He was wary of overly ideological explanations.

In short, The Twelve Who Ruled occupies a distinctive historiographical position. As the first serious monograph on the Committee of Public Safety, it predates the Cold War polarities that shaped later scholarship. In my opinion, Palmer might best be described as a pragmatic liberal historian of the French Revolution. He did not write in the Marxist tradition of Lefebvre or Soboul (though he admired Lefebvre enough to translate his work), nor did he share the iconoclastic edge of later revisionists like Cobban or Furet (2).

Use of Primary Sources

Writing during World War II from the United States, Palmer relied entirely on published primary sources available in America. These included a wide range of printed materials: the proceedings and debates of the National Convention, official documents and reports of the Committee of Public Safety, as well as memoirs, letters, and revolutionary newspapers.

This breadth of material allowed him to reconstruct the Committee’s decisions and actions almost day by day, giving his narrative credibility. Crucially, Palmer did not confine himself to Paris. Because he was interested in the representatives on mission and provincial enforcement of the Terror, he also consulted sources on events in Lyon, Alsace, and Brittany. For its time, the study had a notably wide geographic scope.

Even so, Palmer’s research was limited to what was in print. He lacked access to unpublished archives, local records, or police files that later historians would use to deepen the field of social history. His source base is political and governmental. It reflects the perspective of the revolutionary authorities, not that of ordinary people.

In short, Palmer worked almost entirely with documents written by the deputies and officials (all men) who “ruled.” As a result, the book pays less attention to marginal voices (3). The result is a body of sources broad in political scope, if limited in social depth.

Palmer’s use of sources is generally careful and even-handed. He provides context for the material he cites and avoids cherry-picking. His work relies on French-language sources, as expected for the subject (4). While not archive-based in the modern sense, the research was solid enough that the book’s factual foundation has remained largely intact even after eighy years of further research.

Methodological Rigor

The Twelve who Ruled is not overtly theoretical; its strength lies in a coherent narrative framework and a clear analytical focus. In an era when many academic historians were often abandoning narrative and turning to structural or conceptual models, Palmer resisted the trend. He showed that storytelling, when anchored in analysis, could still carry serious weight. He did not invoke grand theories (Marxist class theory, Tocquevillian social theory, etc.), nor did he fill the text with historiographical jargon. Instead, he focused on applying a steady interpretive lens to the events of 1793–1794.

The idea that the Revolution’s survival hinged on creating a unified, legitimate, and forceful authority during the crisis is the leitmotif of the book. Every chapter, whether addressing the war effort, economic controls, or factional purges, returns to this analytical core. In methodological terms, Palmer’s approach can be described as problem-driven narrative.He identifies the central issue (governing amid chaos) and examines how various factors (personalities, ideologies, circumstances) shaped the response attempted by the Committee of Public Safety. The result is a tightly focused analysis. Despite covering a tumultuous year, the reader always understands why events unfold as they do: because the revolutionaries were trying, with varying degrees of success and virtue, to resolve the Republic’s existential crisis.

In discussing key concepts such as “revolution,” “terror,” and “virtue,” Palmer adopts sensible, if traditional, definitions. He uses the term “Terror” in his title and narrative because it was (and remains) the conventional label for the period, but he is careful to unpack what it meant in practice. He does not treat “The Terror” as a monolithic or abstract force. Instead, he breaks it down into specific policies and events (the Law of Suspects, the Revolutionary Tribunal’s activities, pressure from the sans-culottes etc.) to show how violence was implemented pragmatically, not philosophically.

Notably, Palmer did not anachronistically impose the term “Reign of Terror” on everything, he knew that the term gained currency mainly after Robespierre’s fall. His narrative implies, in line with modern findings, that the revolutionary government itself did not treat “Terror” as a coherent policy slogan (5). Palmer’s treatment of terror as a concept is methodological. He presents it as an emergency government and analyses the mechanics and morality of state violence without becoming entangled in a semantic argument.

His treatment of “revolution” and “virtue” follows the same logic. He presents the Revolution as a struggle to preserve the Republic against its enemies, even at the cost of violating some of its founding principles. He regularly cites the ideals of liberty and equality, and the 1789 Constitution, not to celebrate them but to underline the irony of their suspension “until the peace.” The term “virtue” appears mainly in the context of revolutionary rhetoric, particularly Robespierre’s vision of republican virtue. Palmer does not deliver a philosophical essay on the term. He lets Robespierre and Saint-Just speak for themselves, then examines the consequences. His analysis makes it clear that he understands Jacobin virtue as a kind of austere civic morality, which he implicitly weighs against liberal values.

Methodologically, Palmer is rigorous and consistent. He poses an implicit question: how did twelve men govern a revolution in crisis?—and answers it through a chronological but analytical narrative. His framework is free of glaring contradictions. He weaves political, military, and economic history into a single, unified argument.

The clarity of Palmer’s conceptual handling is evident in how easily the argument can be distilled. Readers never wonder what Palmer thinks the Terror was. He sees it as a revolutionary dictatorship, a term he uses without apology. It was, in some respects, effective (securing military victory), in others, creative (experimenting with democratic forms and state control), and in many, morally troubling.

Narrative Style

This is a subjective category, but one of Palmer’s greatest strengths lies in his narrative style, which is both clear and engaging. Unlike some academic history books, Twelve Who Ruled reads almost like a story, albeit a richly documented one, of a dramatic year in French history. Palmer’s prose is accessible and relatively free of jargon. He was writing for an educated audience, but not exclusively for specialists, and this shows in the readability of the text.

The story is driven by the vivid personalities of the twelve Committee members and the high-stakes drama they lived through. At times, Palmer almost novelistically follows individual members into the provinces or captures the atmosphere in the Convention, which helps the reader visualise events. This blend of narrative colour and historical evidence keeps the text grounded.

That said, the book does not read like a novel throughout. Twelve Who Ruled is densely detailed, and Palmer does not simplify the complexity of Year II. Some sections, for example those on the organisation of war production or the Committee’s internal bureaucracy, are dry and require the reader to absorb a large amount of technical information. However, these are consistently interwoven with more dramatic material such as battles, trials, and political confrontations. The balance keeps the pacing steady across the text.

Palmer is particularly effective in his character sketches. Each of the twelve becomes memorable (Carnot the stern military organiser, Barère the silver-tongued pragmatist, Saint-Just the youthful ideologue etc.) without collapsing into cliché. These almost literary portraits make the reader more invested in the unfolding story.

Perhaps most striking is the absence of pretension in Palmer’s style.His prose has a classic literary quality: measured, erudite, but never self-important. Compared to many writers of historical research, Palmer’s style is disciplined. He doesn’t try to prove his intelligence with a flood of ornate language. He simply writes well.

Originality and Contribution

Upon publication, Twelve Who Ruled was an innovative and ground-breaking contribution to French Revolutionary studies. R. R. Palmer effectively pioneered the focused study of the Committee of Public Safety, a subject that, surprisingly, had never before been treated in a comprehensive monograph. In 1941, historiography on the French Revolution was rich in general narratives and class analyses of 1789 or the broader revolutionary period, but the intense year of the Terror and its governing body had received no sustained study. Palmer filled that gap brilliantly.

By focusing on the twelve men of the Committee and examining their rule as a collective, Palmer offered a new angle. Rather than writing a biography of Robespierre or a general history of the Revolution, he did something original: a group portrait of a revolutionary government in action. This approach yielded fresh insights by highlighting the role of less-famous figures like Billaud-Varene, Lindet, the two Prieur(s) or Saint-André in winning the war and running the country.

At the time, interpretations of the Terror tended to fall into polemical extremes, either apologetic or scathing. Palmer’s contribution was to demystify the Terror. He did not glorify it or denounce it in moral absolutes. He analysed it as a political and historical reality. That stance was unusual in 1941, especially for an American historian. His work managed to synthesise insights from competing schools: it acknowledged the Terror’s necessity in context, a point later taken up by leftist historians, while also recognising its moral and strategic failures, a view more often stressed by revisionists.

This balance gave the book lasting academic value. This synthesis gave the book a lasting academic impact, as it could be read profitably by people on different sides of the interpretive spectrum.

Authorial Bias and Political Agenda

Palmer’s personal values and context inevitably informed his work, yet Twelve Who Ruled is notably measured and fair-minded, without a heavy-handed political agenda. R. R. Palmer was a liberal-democratic American intellectual, and someone who valued the ideals of the Enlightenment and constitutional government. That perspective quietly shapes the book. Palmer clearly admires certain principles of 1789 and he often reminds the reader of what was lost when the Terror regime suspended civil liberties and elections. His sympathy for liberal democracy leads him to approach the Committee of Public Safety with a critical eye, especially regarding their use of coercion and violence. He does not defend the guillotine or the repression of dissent. On the contrary, he treats those as regrettable, if at times understandable, choices.

Crucially, Palmer’s liberalism does not reduce his book to a simple anti-revolutionary stance. If anything, there is a degree of admiration for the Committee’s sense of duty and purpose, even as he remains aware of the compromises they made. He describes the Committee’s rule as a “dictatorship,” but one born of necessity, reflecting a liberal’s reluctant concession that extreme times may call for extreme measures. His relief when the Terror ends is unmistakable. The tone around Thermidor suggests a welcome return to politics as usual, though he does not spare the Thermidorians from criticism either.

Throughout, Palmer shows a clear preference for moderation. He tends to praise figures like Barère or Carnot when they show pragmatism or hesitation toward the use of violence. Barère is labelled, for instance, a “reluctant terrorist,” someone who chose expediency over fanaticism. In contrast, Palmer is more critical of those he sees as driven by ideology. Figures such as Billaud-Varenne or Collot d’Herbois are portrayed less sympathetically, as hardliners whose insistence on revolutionary purity helped drive repression too far.

Even here, Palmer does not resort to caricature. He places the actions of extremists in context, explaining their behaviour as a product of pressure rather than inherent cruelty. His bias, to the extent that it appears, leans toward moderate, pragmatic politics. He gives implicit approval when the Committee acts with competence and restraint. He shows clear discomfort when ideological rigidity overrides practical judgment.

If anything, the book carries a mild Whiggish tone (6). Palmer seems to view the Terror as a detour from the path of democratic progress, a necessary detour but a detour nonetheless. This aligns with a classical liberal reading of the Revolution, where 1789 and 1793 are seen not as a permanent rupture, but as part of the long and painful emergence of liberal democracy. In the final chapters, Palmer’s relief at the Republic’s military victories and the subsiding of emergency measures feels almost celebratory, implying a return to the Revolution’s original liberal course. Yet, he also soberly concludes with the personal tragedies of the twelve, showing that history’s verdict is complicated.

It is also worth noting what Palmer does not do. Namely, propaganda.

Twelve Who Ruled is not a cautionary tale or propaganda tract. Given that it was written in 1941, with fascism on the rise, one might expect an American liberal to use the French Terror to denounce totalitarianism. But Palmer avoids crude analogies. He lets readers draw their own conclusions. A reader in 1941 might well think of Hitler or Stalin while reading about the dangers of concentrated power, but Palmer does not push that comparison. His portrait of the Committee, a dictatorial body that nevertheless saved France, complicates any simple moral about dictatorship. The lesson is not imposed.

Suitability for Teaching or Further Research

Over the years, Twelve Who Ruled has proven highly effective for teaching the French Revolution and remains a reliable point of entry for further research. Its structured narrative and wide scope make it a strong introduction for students and general readers, while its analytical precision offers more experienced readers material for reflection and debate. Within Anglophone historiography, few works cover Year II with the same aplomb.

The book’s focus on individual leaders and specific crises helps anchor the chronology of 1793 to 1794 in something tangible and humane. Because Palmer explains context as he goes, for example by giving background on the Vendée revolt, the Federalist insurrections, and the food shortages, it allows even newcomers to the topic to grasp the wider dynamics of the period.

Its limitations are those of its time. Now more than eighty years old, the book does not reflect more recent developments in the field. Questions of gender, global context, symbolic culture, and the experience of ordinary people are not part of Palmer’s framework.

Most importantly, the book is so well-written that even someone unaccustomed to reading non-fiction will find it engaging. It does not demand specialist knowledge, but it never talks down to the reader. As an introduction to the French Revolution, it is hard to beat. Few works manage to be this serious, this readable, and this enduring at the same time. It remains a book worth reading, not just for what it says about 1793, but for how well it says it.

Notes

(1) This is worth a post of its own, but in short—and this is an extremely simplified summary—the historiography of the French Revolution can be broadly outlined as follows:

Conservative reaction (1790s to 1890s): Sees the Revolution as a catastrophe that overturned legitimate order. Authors: Edmund Burke, Hippolyte Taine, Louis de Bonald.

Liberal narrative (1820s to 1910s): Praises the moderate reforms of 1789, condemns later extremism, and stresses continuity with the Old Regime. Authors: Adolphe Thiers, Alexis de Tocqueville, François Guizot.

Radical republican and proto-socialist (1840s to 1930s): Celebrates popular egalitarianism and defends Jacobin democracy. Authors: Jules Michelet, Louis Blanc, Jean Jaurès.

Marxist classical social school (1920s to mid-1960s): Frames the Revolution as a bourgeois class struggle that abolished feudalism and views the Terror as a necessary defence. Authors: Albert Mathiez, Georges Lefebvre, Albert Soboul, Michel Vovelle.

Revisionist critique (mid-1960s to late 1980s): Rejects the class model, emphasises political contingency and the culture of violence. Authors: Alfred Cobban, William Doyle, François Furet, Simon Schama, Patrice Gueniffey.

Post-revisionist and cultural turn (late 1980s to 2000s): Combines political and social analysis, focuses on language, symbols, and local experiences. Authors: Lynn Hunt, Timothy Tackett, Jean-Clément Martin, Mona Ozouf, Roger Chartier, Peter McPhee, Hervé Leuwers.

There are also several other areas of research like Gender History and Colonial Perspectives which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s.

(2) It goes without saying that recent post-revisionist trends, including cultural and gender-focused approaches, lie outside Palmer’s scope. These methodologies only emerged decades after 1941. Palmer does not, for example, examine revolutionary festivals, political symbols, or the “culture of citizenship” as later cultural historians would.

(3) This is not unique to Palmer. Most scholarship of his time ignores marginalised groups, including women, the poor, enslaved people, and colonial subjects.

(4) PSA: if you are reading a history book on a specific country or event, and most of its sources are not in that country’s language, stop reading.

(5) Palmer does recount the demand of 5 September 1793 to make terror “the order of the day,” but he treats it as a historical moment rather than an ideological programme.

(6) Whiggish refers to a teleological view of history, typically associated with 19th-century liberal thought. It sees the past as a steady march toward progress, constitutional government, and political liberty. A “Whiggish” historian tends to interpret events as steps on the road to modern democracy, even when those steps include violent detours.

#frev#robespierre#saint just#committee of public safety#history#amateurvoltaire's reviews#lazare carnot#twelve who ruled#historiography

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Marauders

I'm full of spite. So American Marauders.

In this AU they're at a boarding school in New England (Ala Dead Poet's Society but slightly less cult-ish). This is mostly a list of their interests in the context of a high school.

James: Football quarterback. Not just because it's the stereotypical position, but because it's actually the most similar to a chaser position and also because it requires advanced knowledge of strategies and leadership skills. He'd also be into the photography and film club. I have no solid reason for this other than vibes. He feels artsy.

Remus: Astronomy club because the moon (original, I know), but also because I think he'd like the quiet and the science of it (there is science to astronomy, calculating orbits and shit). AP lit TA because I KNOW that boy would absolutely crush grading an essay or leading socractics. Similarly, he'd be a part of the school newspaper doing something creative or editorial

Sirius: Not huge on the resume booster extracurricular activities because he's spiteful of his legacy family. He probably was in the school band at the start (clarinet or French horn or something), but he'd quit in favor of guitar or bass. I think he'd join the astronomy club for an excuse to hang out with Remus, and he'd end up actually enjoying it.

Peter: This boy had a job. I feel like he has to have one for necesity purposes (work-study scholarship), but I also think he enjoys the structure of it. He'd work at the campus cafe or something similar. I feel like he'd also do something artistic sort of casually. I feel like he'd enjoy ceramics, it's very meditative. But I don't think he's really all that good at it (sorry Pete, you give me pathetic, untalented energy sometimes)

+ The girls.

Lily: Chem lab TA (I'm biased because I was a chem lab TA). She'd enjoy prepping chemicals and she responsible enough for it. She'd also enjoy the teaching and tutoring that comes with it. She's a good teacher. She'd also be a part of the school newspaper with Remus (that's how they become friends). I think she'd do something more informational or opinions based (maybe covering sports games....)

Mary: Art student. Like fine arts, not theatre. Not biased against theatre kids, it's just not her vibe, though I do think she'd help with set design and painting. In terms of art, I think she's a painter primarily but also ceramics and charcoal drawing and that kind of thing. I think she'd also be interested in some casual crafting related club like knitting or crocheting or something. Just peaceful.

Marlene: Soccer team! A striker or a midfielder I feel. It's the gayest sport I'm sorry. She's extremely committed to it, she runs cross country in the soccer off season to keep in shape. She'd probably be recruited for college. She'd probably be in the GSA (gay-straight alliance in the old days, gender and sexuality alliance in the modern day) but more casually.

Dorcas: Soccer team (also. Gay!). She'd be a goalie though. More patient, more defense oriented. I also feel like she'd be a TA for something history or debate related. I'm thinking either APUSH or perhaps a philosophy and government TA? I feel like she'd be great at that. I also feel she'd be the type with a lot of extra curriculars so perhaps a few more clubs. GSA with Marlene???

#marauders#james potter#sirius black#remus lupin#peter pettigrew#lily evans#dorcas meadowes#marlene mckinnon#mary macdonald

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today In History

Angela Davis, political activist, philosopher, academic, and author was born in Birmingham, AL, on this date January 26, 1944.

Davis knew about racial prejudice from a young age; her neighborhood in Birmingham was nicknamed “Dynamite Hill” for the number of homes targeted by the Ku Klux Klan. She also knew several of the young African American girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing of 1963.

Angela earned a scholarship to study French Literature at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. After graduation, she studied in Germany and completed a PhD in philosophy.

In 1969, Angela became a professor of philosophy at the University of California at Los Angeles. Governor of California Ronald Reagan learned about Angela’s political connections and pressured the university to fire her. Angela fought back, and took her case to court. The Supreme Court of California ruled Angela could not be banned for party affiliation. However, several months later, the university found another reason to fire her. They claimed that her comments in recent speeches were too politically incendiary.

Around the same time that Angela lost her job, she became involved in the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee. On August 7, 1970, an armed gunman and brother of one of the Soledad Brothers entered a courtroom in California and took several people hostage. An investigation revealed that the gunman used a weapon Angela bought at a pawn shop several days earlier. Distrustful of the government, Angela went into hiding. During that time, the FBI added her to the “10 Most Wanted” list. In October, she was arrested in a hotel room in New York City. She was held in jail for 18 months.

On June 4, 1972, an all-white jury found Angela not guilty on all charges. Angela said it was the happiest day of her life.

“As a black woman, my politics and political affiliation are bound up with and flow from participation in my people’s struggle for liberation, and with the fight of oppressed people all over the world against American imperialism.”

CARTER Magazine

#angela davis#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

(A print of the 1868 Battle of Ueno [source])

Okay, so this is a ways off, but what follows is an attempt to briefly outline for your enjoyment and edification what a hypothetical book by me on the Boshin War would look like.

First, it would follow Ishii Takashi's view that this was not one war, but three in one.

One side, the nascent Kyoto government, was consistent throughout. The other was not.

So we have the war from Kyoto to Edo against the former Shogunate, the war in Tohoku against the Northern Alliance, and the war in Ezo against the so-called Republic

Ōyama Kashiwa, whom I mentioned earlier, calls it "the Boshin campaign," which I think also has some utility.

I would also very sharply distinguish between the combatants fighting the Kyoto government. the Northern Alliance was not "pro-shogun," though it was allied with the former Shogunate's army

this is because of a thousand years of precedent of regional semi-autonomy. I wrote my dissertation on this. No, it doesn't matter what the tourist website you encountered told you, they're wrong.

You need to understand the Northern Fujiwara to understand the Tohoku alliance.

a longue duree perspective will likewise be necessary, because the outcome of this war, especially in the Tohoku region, was decided decades in advance, in part because of famine and depopulation.

they could never have won, not for lack of technology but because of the Tenpo Famine.

It will be brutal to write about the war, as writing about war necessarily is, because the so-called imperial army chose to exercise such brutality. They made it illegal for Aizu domain to bury its own dead, and thus so profoundly polluted the land that some Aizu survivors became Christian.

We will also need to appreciate the role of the foreign powers beyond what is normally spoken of in what English scholarship exists. the Northern Alliance petitioned the US for aid. the British were actively running guns to Satsuma. The French military mission was embedded in the Shogunate Army.

Women in combat, likewise, must be given attention, and no, I'm not simply speaking of Nakano Takeko.

Yamamoto Yae, for one, is right the hell there.

We will have to dismantle myths about the war, too, like the claim that the Tohoku alliance fought to restore the Shogun and hated guns.

But especially we will need to underline that Enomoto's government in Hakodate was. not. a. republic.

We will need to also underscore how this was significantly the samurai caste fighting itself, because there are petitions written by townsmen and farmers begging both sides to knock it the fuck off, at least long enough to bring the harvest in.

Finally, we will need to understand that the Boshin War, in a sense, didn't really end. Its survivors on all sides got tied up in different movements over the course of the Meiji era-- some were Saigo's men in the Seinan War, others were Itagaki's allies in the Freedom and Popular Rights Movement, and...

….until the 1920s, saying anything against the official imperialist line was in some cases punishable by ostracism and prison.

So, who broke through that silence? How did they do it?

We will have to give them their due.

(cough his name was Dr. Yamakawa Kenjiro and he blackmailed the imperial court into backing the fuck off cough)

#boshin war#bakumatsu#shinsengumi#japanese history#aizu domain#sendai domain#sendai#tohoku#samurai#northern alliance

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mario Jiménez

Name: Mario Antonio Jiménez Castro

Age: 52 (by 2025)

Birth date: August 30th of 1983, Ubaté, Boyacá, Colombia

Death date: January 12th of 2025, Leticia, Amazonas, Colombia

Nationality: Colombian

Residence (former): Camp General Pinilla, Colombia

Affiliations: Colombian National Army (formerly), Anti-federationists (formerly)

Rank: General

Nickname: My love (by Paula), Commander (by the Anti-federationists)

Occupation: General and consultant in the Congress (formerly), leader of the Anti-federationists (formerly)

Height: 1,85 m/ 6'0 ft

Weight: 82 Kg

Blood type: A+

Pronouns: He/him

Sexuality: Heterosexual

Languages: Spanish (native), english, french, quechua and chibcha

Affiliations:

Anti-federationists:

-Camilo Ortiz Álvarez (former right hand man/ current Commander)

Ghosts (temporary):

-Gabriel Rorke

-Elias Walker

-Thomas Merrick

-Keegan Russ

-Alex “Ajax” Johnson

Family:

-Father (redacteed) (deceased)

-Mother (redacteed) (deceased)

-Paula Rojas Vásquez (wife) (deceased)

-Juliana Jiménez Rojas (daughter)

Personality:

-Thoughtful man, charismatic and a born leader that can use a situation in his favor in a matter of minutes.

-Appears to be cold or even aggressive at first, but in reality he's a fun man, romantic husband and lovable and protective father.

-Quiet man unless someone won his trust or they’re planning something.

Biography:

He was born in Ubaté, Colombia, as the only son of a couple of farmers. For years he worked in his parents farm while going to school, but also aware that at some point…it might be taken away from them. It could be because of paramilitarism, the guerrillas, the narcos or even the government itself.

Despite that, he continued working and studying until he finished high school. Honestly he was ready to work with his parents without going to college…but as soon as the ICFES results came back, he won a scholarship. Mario was ready to deny it and stay with his parents, but his mother asked him to go and even his father gave him all their savings the day he was departing to Bogotá for college.

He studied law and worked at night to pay for his studies. It went well until his last year, when he got the notice that his parents died at the hands of the FARC. The day of his graduation…he was alone because of that.

After that he joined the Army, mostly for hunting down the guerrillas and narcos, and started his services and career there.

Some years later, he was sent to a conference in one university. There he met Paula Rojas Vásquez, a woman that was in her last year of International Studies, with who he started a long conversation after the conference. They started to speak and go for a walk every time Mario and Paula had a free day.

In the end they fell in love and married when Mario was 27, in 2000, and that same year Juliana was born. They lived in Bogotá due to their work until 2011, when Paula did some research with the university she worked at and they learnt about the Federation's real intentions. After that, hell broke loose.

The Feds attacked the universities as soon as they arrived in Bogotá. Paula died in one of those attacks, and Mario started to prepare the exodus along with many others.

Camilo and he ran away from Bogotá the night before the Feds conquered the presidential palace. They walked, with hundreds of thousands of people before parting ways with a part of them. Their group headed to the south of the country, to the rainforest.

There, they walked for even more days while Camilo, Mario and many other officers discussed what to do. In the end, despite Mario's hatred for the idea, they ended up joining the guerrillas for pure survival. And that lasted for a decade.

In 2015 he went to Caracas along with some volunteers to help killing General Almagro, where he met the Ghosts and befriended them as well.

He always stayed with the kids after their training, comforting them and distracting them from the terrified and pained screams of some women and men. And the tenth year, they had enough to take over, so he led the adults and took over the camp they were at to make it theirs.

Like that the Anti-federationists were founded with him as Commander, and for some years he was the leader and expanden their influence. Until one day in 2025, he was found and killed in Leticia by Rorke, a Ghost he once met.

Skills:

-Sniper and recon expert

-Knows guerrilla warfare and conventional tactics

-Adaptability at any environment

-Experience in urban warfare as well

-Leadership at high scale

Trivia:

-Before the Feds even existed, he loved to go and take a walk with Paula and Juliana. Mario always carried his daughter over his shoulders, teaching her some things every time she asked.

-During the years with the guerrillas, he played the guitar to calm the kids down. And even then, he was saddened when he saw the older kids looking at the door with a mix of fear, anger and disgust.

-He made the main links with people that escaped in South America during his days in the guerrillas and when they already were Anti-federationists, leaving everything ready for Camilo to start with what he planned when he replaced him.

Picrew:

Face claim:

Alejandro Aguilar

#call of duty#cod oc#oc#ocs#cod ghosts#call of duty ghosts#cod ghosts oc#cod ghosts original character#call of duty ghosts oc

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

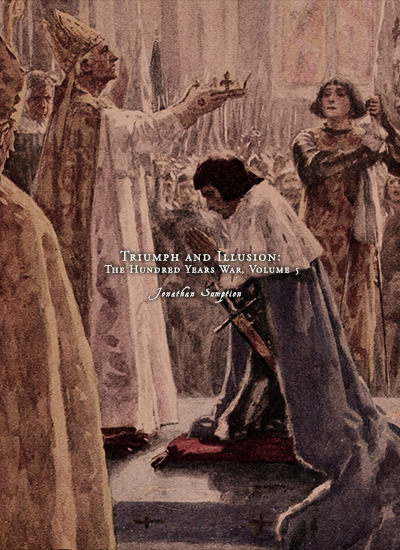

Favorite History Books || Triumph and Illusion: The Hundred Years War Volume 5 by Jonathan Sumption ★★★★☆

The wheel of fortune is one of the most ancient symbols of mankind, an image of capricious fate and the transience of human affairs. In the late middle ages it was everywhere, in illuminated manuscripts, in wall paintings and stained glass, in sermons and homilies, in poetry and prose. ‘The wheel of fortune turneth as a ball, sudden climbing axeth a sudden fall,’ wrote John Lydgate in The Fall of Princes, a work commissioned by one of the dominant figures in this history, Cardinal Henry Beaufort. The present volume traces the remarkable recovery of France in barely two decades from the lowest point of its fortunes to the dominant position in Europe which it had enjoyed before the wars with England. Sudden climbing axeth a sudden fall. These years saw the collapse of the English dream of conquest in France from the opening years of the reign of Henry VI, when the battles of Cravant and Verneuil consolidated their control of most of northern France, until the loss of all their continental dominions except Calais. This sudden reversal of fortune, inexplicable to many contemporary Englishmen, was a seminal event in the history of the two principal nation-states of western Europe. It brought an end to four centuries of the English dynasty’s presence in France, separating two countries whose fortunes had once been closely intertwined. It created a new sense of identity in both of them. In large measure, the divergent fortunes of the French and English states over the following centuries flowed from these events. The passions generated by ancient wars eventually fade, but those provoked by the wars of the English in fifteenth-century France have proved to be surprisingly durable. The foundations of scholarship on the period were laid by patriotic French historians of the nineteenth century, writing under the shadow of Waterloo and Sedan. The passage of the centuries did nothing nothing to soften their indignation about the fate of their country in the time of Henry VI and the Duke of Bedford. The extraordinary life and death of Joan of Arc defied historical objectivity until quite recently. Joan’s story became the focus of disparate but powerful political passions: nationalism, Catholicism, royalism and intermittent anglophobia. Much of what has been written falsifies history by attributing to medieval men and women the notions of another age. But myths are powerful agents of national identity. The great French historian Marc Bloch once wrote that no Frenchman could truly understand his country’s history unless he thrilled at the story of Charles VII’s coronation at Reims. Writing in the summer of 1940 in the aftermath of a terrible defeat, Bloch looked to an earlier recovery from the edge of disaster for reassurance about the survival of France. If there is a corresponding English myth, it is in the history plays of Shakespeare. The great speeches which he gave to John of Gaunt and Henry V belong to the classic canon of English patriotism. His three plays about Henry VI, a truncated story of discord at home and defeat abroad, never reach the same heights. Yet they serve to remind us that behind the clash of arms and principles were men and women of flesh and blood. I have tried at every page to remember that they were not cardboard cut-outs. They endured hunger, saddle-sores and toothache. They experienced fear and elation, joy and disappointment, shame and pride, ambition and exhaustion. At the level of government, they were trapped by the logic of war, lacking the resources to conquer or even to defend what they had, and yet unable to make peace. It was the tragedy of the English that, after an initial surge of optimism in the 1420s, they realised that the war could not be won, but were forced to fight on by the memory of Henry V’s triumphs and the incapacity of his son, until disaster finally engulfed them.

#litedit#historyedit#hundred years' war#medieval#history books#french history#english history#european history#history#nanshe's graphics

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Léon Damas (March 28, 1912 - April 22, 1978) was a poet, editor, diplomat, and cultural theorist who was born in Cayenne, French Guiana. He was the youngest of five children born to parents Ernest and Marie Aline Damas.

He left French Guiana to attend the prestigious Lycée Victor-Schœlcher. He attended the University of Paris. His scholarship was for the study of law, he developed an interest in the humanities and social sciences. Influenced by Andre Breton’s anti-colonial pamphlet Légitime Défense, by his encounters with the work of Harlem Renaissance poets like Claude McKay and Langston Hughes, and by the growing community of US Black expatriate writers and artists, he began to assert his identity as a poète Nègre.

He and Aimé Césaire met Léopold Sédar Senghor. The three founded the journal L’Étudiant Noir, called Négritude.

He was the first Black writer to address the impact of colonization on the psyche of the colonized. He introduced this colonial and postcolonial condition more than 20 years before philosopher Frantz Fanon would label such traits “the colonized personality”.

He was the author of nine other volumes, including five additional books of poetry, three essay collections, and one book of short stories. In addition to a writing career that spanned 40 years, he held several prominent and influential positions in military, diplomatic, and government organizations. He served in the French army during WWII. He was elected to the Chambre des Députés of the French National Assembly. He became the overseas editor for Radio France, a contributing editor on the board of the journal Presence Africaine, and a representative of the African Society of Culture for the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization.

He traveled extensively in Africa, Latin America, the US, and the Caribbean. He settled in DC, where he accepted a visiting professorship at Georgetown University. He was offered a permanent position at Howard University, where he remained on the faculty until his death. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

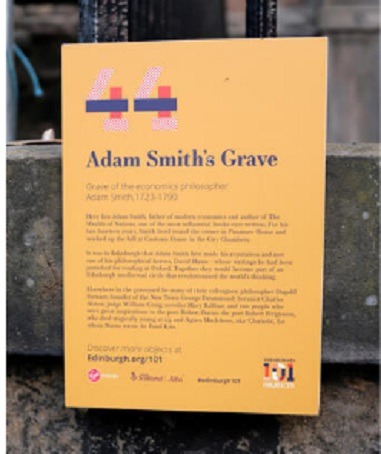

On July 17th 1790 economist, philosopher and author Adam Smith, died in Edinburgh.

Smith attended the local school where he was bought up, in Kirkcaldy, Fife before enrolling, aged 14 at Glasgow University, then a central institution in the prevailing humanist and rationalist movement which later became known as the Scottish Enlightenment. Smith cites the lively discussions led by Professor of Moral Philosophy, Francis Hutcheson, as having a profound effect on his passion for liberty, free speech and reason.

In 1740, Smith was the recipient of the Snell Exhibition, an annual scholarship allowing Glasgow University students the opportunity to take up postgraduate study at Balliol College, Oxford.

Smith’s experiences at Glasgow and Oxford were completely different. While Hutcheson had prepared his students for vigorous debate through challenging new and old ideas, at Oxford, Smith believed “the greater part of the public professors [had] given up altogether even the pretence of teaching”.

Smith was also punished for reading A Treatise of Human Nature by his later friend David Hume. Smith quit Oxford before his scholarship ended and returned to Scotland.

On his return home Adam Smith became a professor at the University of Edinburgh. It was at Edinburgh that he met David Hume.who would become one of his best friends. Over the years, Smith and Hume would discuss economics and philosophy. During this time, Smith began to formulate the ideas that would make him famous.

In 1759, Smith published The Theory of Moral Sentiments. He gained some fame for this work and was offered the job of tutor for young Duke Henry Scott. As tutor, Smith began to travel throughout much of Europe. He met many influential people including French economist Francois Quesnay and American diplomat Benjamin Franklin. Smith's theories on the economy continued to develop.

In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations. This book became the foundation of modern economics. It introduced and explained many economic concepts that are still used today. The most important idea in the book is the idea of the free market economy. This is where he proposes that the most productive economy is one that is allowed to regulate itself without government intervention.

Adam Smith died in Edinburgh, on this day in 1790. Today, he is known as the father of modern economics. The Wealth of Nations is one of the most influential books in history. Most countries throughout the world today operate a mixed economy that combines the free market described by Adam Smith with some government intervention.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A note to Donald Trump from a friend of all of ours David Suzuki.

Proud to be Canadian

David Suzuki

Thank you Mr. Trump. Canadians are already tightly bound to your country physically, economically and culturally, so your threat to absorb us as a 51st state of the United States of America, forces us to ponder our values and reasons for remaining a sovereign nation that claims to be independent.

I am a Canadian, a third generation Canadian of Japanese ancestry. My parents and I were born and raised in Canada, had never visited Japan, yet were incarcerated during World War II as “enemy aliens”. Years after the war’s end when we were still mired in poverty, a $1500 scholarship worth more than my father made in a year, made it possible for me to attend Amherst College in Massachusetts. I am forever indebted to the U.S. where I moved to in 1954 for 8 years and where I received a superb university education because foreign students were valued as contributors to the education of American students.

In my senior year, on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union shocked the world when it launched Sputnik. In the following years as the Soviets launched a series of space firsts (a dog, a man, a team, a woman), the U.S. clearly lagged behind, but the response was amazing. The U.S. government began to invest massively in science and scientists. I was a foreign student, yet whenever I expressed my interest in science I would get offers of scholarships and jobs.

Of course, in 1962, when John F. Kennedy announced the goal of reaching the moon in a decade, the Space Race was on. At the time, it wasn’t clear how to do it or how much it might cost. The commitment was made and money, resources, infrastructure and humanpower were thrown in to meet the challenge. Not only did America succeed, sixty years later Nobel prizes in science continue to be disproportionately won by American scientists or researchers in the US while hundreds of unpredicted spinoffs like laptop computers, GPS and ear thermometers, resulted. It was an impressive expression of the kind of American resolve that could serve well as a model to meet the challenges of climate and ecosystem breakdown.

By the time I was doing postdoctoral work in the US in 1961, employment opportunities in universities, government and the private sector were enormous. It was a glorious time to be a scientist. Nevertheless, I chose to return to a Canada lagging far behind in support of scientists, especially in my chosen area of genetics. To my scientific colleagues, it seemed like academic suicide.

I chose to return because Canada was different, not better than the U.S., and those differences reflected values that mattered most to me. Canada had a health system available to all regardless of economic status or ability to pay. Tommy Douglas was a huge hero to me and all Canadians, a champion for the poor and disadvantaged yet his socialist party (CCF that later became the NDP), was respected and legitimate in Canada, but would have been outlawed as Communist in the US. And I was proud of the Equalization policy whereby the provinces that are better off economically share some of their wealth with those that are not doing as well.

As a biologist, I know diversity of genes, species and ecosystems, have maximized options and thus enabled life to survive and flourish in an ever changing environment. Humans have occupied many different parts of the planet because of an added level of diversity - culture. That’s why Quebec and its culture are important parts of Canada (to my great regret, I never learned to speak Japanese because my father always said “we are Canadians. If you learn a second language, it must be French”). The enormous diversity created by elevating Indigenous nations and immigrants from all parts of the world into the fabric of Canadian society provides adaptability and resilience few other countries have as we confront the ecological and economic limits we face today. That’s also why I value the National Film Board (NFB) and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) that enable us to see ourselves and the world through the lenses of a Canadian perspective and our ever evolving values.

I have never regretted my decision to return home to Canada and I thank you, Mr. Trump, for reminding me why. I hope all Canadians reflect on this country and why we will fight to preserve our differences from your great nation.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

World Braille Day

World Braille Day celebrates the birth of Louis Braille, inventor of the reading and writing system used by millions of blind and partially sighted people all over the globe.

Though not a public holiday in any country, World Braille Day provides an opportunity for teachers, charities and non-government organizations to raise awareness about issues facing the blind and the importance of continuing to produce works in Braille, providing the blind with access to the same reading and learning opportunities as the sighted.

History of World Braille Day

Louis Braille, the inventor of braille, was born in France on January 4th, 1809. Blinded in both eyes in an accident as a child, Braille nevertheless managed to master his disability while still a child. Despite not being able to see at all, he excelled in his education and received scholarship to France’s Royal Institute for Blind Youth.

During his studies, inspired by the military cryptography of Charles Barbier of the French Army, he developed a system of tactile code that could allow the blind to read and write quickly and efficiently. Braille presented the results of his hard work to his peers for the first time in 1824 when he was just fifteen years f age. In 1829, he published his first book about the system he had created, called “Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them”.

The braille system works by representing the alphabet letters (and numbers) in a series of 6 dots paired up in 3 rows. The simplicity of his idea allowed books to start being produced on a large scale in a format that thousands of blind people can read by running their fingertips over the dots. Thanks to this, blind students have the opportunity to be educated alongside their peers as well as read for pleasure just as easily as any seeing person can.

How to celebrate World Braille Day

As incredible as braille is, and as much as it offers blind and partially sighted people, braille books must stay within the country where they are produced because ofrestrictive international copyright laws. Because braille books cannot be shared across borders, the blind cannot read any books that are not produced within their own country. Unfortunately, at present only 5% of all published materials get produced in accessible formats, which means that under 10% of all blind children in developing countries go to school due to the shortage or lack of teaching materials.

The Marrakesh Treaty is the name of an international agreement finalized in June 2013 that would allow copyright exceptions for published works to be made widely available in accessible formats. The implementation of the Marrakesh Treaty will allow blindness organizations to share their resources with other organizations in developing countries that may not have the resources to produce books for their blind citizens.

Then, schools for the blind in wealthier countries would be able to send books to schools in poorer countries so blind children who cannot afford to buy braille books will still have access to the textbooks needed for them to finish school. For example, Spain’s ONCE (Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles, or The Spanish Foundation for the Blind) could make their braille library available to blindness organizations in all of the Spanish-speaking countries in South America, thus saving the costs of reproducing the exact same books for each separate country.

However, these resources can be shared only if this treaty becomes law in all of the countries around the world.

This coming World Braille Day, celebrate Louis Braille’s achievements and help millions of blind and partially sighted people everywhere by writing a letter to your government representatives encouraging them to make this treaty a reality.

Source

#Chicago by Joan Miró#World Braille Day#4 January#Chicago#Illinois#USA#summer 2019#original photography#vacation#travel#sculpture#landmark#tourist attraction#WorldBrailleDay#international day#cityscape#public art

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Anne Boleyn wasn’t exactly a Protestant as is often said but she was a Reformist. She still held on to some of the Catholic beliefs such as the doctrine of transubstantiation but rejected papal authority, promoted erastianism and worked on getting the Bible translated into vernacular English so the common people of England could read it and understand it (The Bible was released shortly after her death, with the dedication page hastily changed to Queen Jane’s name). She wanted to purify the Catholic church of things she saw as abuses (such as the extreme wealth of the Catholic Church, and excessive accumulation of wealth in general, selling salvation — literally!) and superstitions. She’s the one who introduced Henry VIII to the idea of becoming Head of the Church of England by giving him a book written by William Tyndale, Obedience of a Christian Man, with certain passages marked by the impression of her fingernail. It was a bold move because the book was banned and had been seized by the Church when they found it in her possession. Anne asked Henry to get it back for her and read it. (Anne’s brother, George Boleyn, smuggled banned religious texts for her, purchasing them on his travels to the Continent.)

Anne sheltered religious dissidents. She saved the life of the French reformer Nicolas Bourbon as she had appealed to the French royal family to spare his life as a favor to the English Queen. Nicolas Bourbon would later refer to Anne as “the queen whom God loves.” She restored Richard Herman to the membership of the English Society of Merchants, from which Cardinal Wolsey had expelled him for his involvement in translating the New Testament into English. Anne also offered safe passage to England to French humanist reformers. She paid for scholarships so Reformist scholars could attend the universities. (Many of them stayed after they graduated to teach the next generation and spread Reformist ideas.) She personally selected six of the nine bishops appointed during her reign. She was extremely charitable and generous and sew shirts for the poor. When monasteries were dissolved, Anne advocated the redistribution of their resources and wanted to use the money to fund educational programs and other charitable causes. On the other hand, Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief minister, wanted to transfer these funds to the king’s coffers.

In short, religious issues were the primary focus of the work she did during her reign. Her goal for the advancement of a more tolerant religious point of view was unusual in an age that favored rigid religious practice. It’s one of the reasons she was so deeply unpopular — she was seeding “heresy” in so many areas. Eustace Chapuys, the Imperial ambassador in England, regularly complained to his home government of “the concubine” being “the cause and nurse of the spread of Lutheranism in this country”. They were right to be alarmed; Anne Boleyn’s work helped lay the foundations of the Anglican church. It would later be expanded upon by Queen Kateryn Parr, who appointed two of Anne’s scholarship students to be the tutors of Edward VI, the first Protestant monarch.

Wow. Yeah, this is displays a lot more devotion to a certain mission and a desire to change a society or a generosity that some people tried to say Alicent displays--which was never actually spelled out or claimed even in F&B, btw!--as reason for them to believe that Alicent was a good Queen or just a good person. The whole Queens-as-leads-of-charity-and-alms thing. Can't find the post.

#ask#anne boleyn#english history#the tudors#William Tyndale#henry viii#Nicolas Bourbon#Richard Herman#Cardinal Wolsey#Thomas Cromwell#Eustace Chapuys#Kateryn Parr#Edward VI#the anglican church#english reformation#anglicanism#english queens#european queens#european history

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

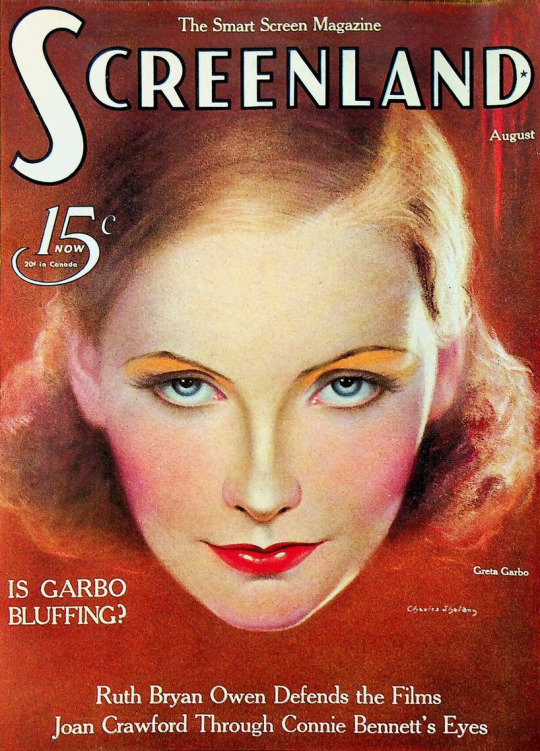

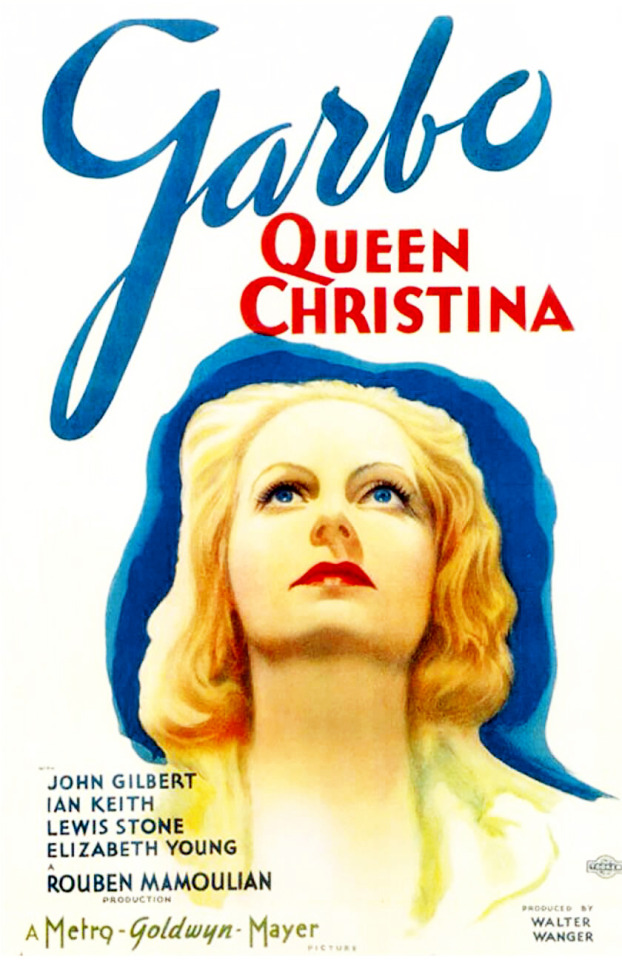

Greta Garbo - The Face of the Century

Greta Garbo (born Greta Lovisa Gustafsson in Stockholm, Sweden on 18 September 1905) was a Swedish-born actress who built her global appeal on a carefully maintained mystique during her short career. Called "The Face of the Century," she is regarded as one of the Hollywood's greatest beauties.

Garbo was born into a poor family and dropped out of school at 13 to take care of her father. His death deeply affected her and promised to make a life for herself that was void of financial hardship.

Following her father's death, Garbo worked as a salesperson at PUB department store. After modeling for the store's catalogues, she earned a more lucrative job as a fashion model, which led to a role in her first film in 1922.

She then earned a scholarship at the Royal Dramatic Training Academy, where she met Finnish director Mauritz Stiller, who became her mentor. Louis B. Mayer of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer wanted Stiller in Hollywood. The director agreed to a contract with one condition: Garbo. Reluctantly, Mayer inked her a deal, too.

She made her first MGM film in 1926, and by 1928, had become MGM's highest box-office star with A Woman of Affairs. She followed it up with several more hits, including Camille (1936). Her career slowed down in the 1940s and retired at 35.

After retiring, Garbo declined all opportunities to appear onscreen, shunned publicity, and led a private life. She died, aged 84, in New York, as a result of pneumonia and renal failure.

Legacy:

Nominated three times for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performances in Romance (1930), Camille (1936), and Two-Faced Woman (1941)

Presented an Academy Honorary Award in 1955

Received the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress twice: Anna Karenina (1935) and Camille (1936)

Won the National Board of Review Best Acting Award three times: Camille (1936), Ninotchka (1939), and Two-Faced Woman (1941)

Was the highest-paid star at MGM for most of her career

Won the Photoplay Awards - Best Performances of the Month for a record eight times: May and December 1926, February and November 1927, March and September 1928, and January and March 1929

Won Best Actress for Anna Christie (1930) and Queen Christina (1933) from Picturegoer Awards

Listed by the Motion Picture Herald as one of America’s top-10 box office draws from 1930 to 1932

Was one of the subjects of French composer Charles Koechlin's "Seven Stars Symphony" (1933)

Granted the Swedish royal medal Litteris et Artibus in 1937

Is one of the celebrities whose picture Anne Frank placed on the wall of her bedroom in the “Secret Annex” in 1942

Voted "Best Actress of the Half Century" in a 1950 Daily Variety opinion poll

Named “the most beautiful woman that ever lived” in 1954 by Guinness World Records

Given the George Eastman Award by George Eastman House in 1957

Has appeared on many postage stamps from, among others, Swedish Posten in 1980 and 2005, Correos de Cuba in 1995, Deutsche Post in 2001, US Postal Service in 2005, Poșta Română issue in 2005, and Australia Post in 2008,

Made a Commander of the Swedish Order of the Polar Star by order of King Carl XVI Gustaf in 1983

Depicted in the film Garbo Talks (1984)

Awarded the Illis Quorum by the government of Sweden in 1985

Had a star was named after her in 1985

Has appeared on commemorative coins from Germany in 1994, France in 1995, and Sweden in 2005

Ranked #38 in Empire's Top 100 Movie Stars in 1997; #25 in Entertainment Weekly’s 100 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time in 1998; #8 in Premiere's 50 Greatest Movie Stars of All Time in 2005 and #25 in 100 Greatest Performances of All Time in 2006 for Ninotchka (1939)

Has had a museum, the Garbosällskapet, dedicated to her in Högsby since 1998

Named the 5th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema in 1999 by the American Film Institute

Inducted in the Online Film and Television Association Hall of Fame in 2002

Chosen in Variety magazine's "100 Icons of the Century" in 2005

Honored by Stockholm City Council in 1992 with a square, Greta Garbos Torg, and a bust of her likeness in 2009

Honored by Norwegian Air Shuttle as its "Tail-fin Hero" on its Boeing 787 Dreamliner in 2016

Featured on 100-krona banknote by Sveriges Riksbank since 2018

Featured in an exhibit at the Postmuseum in 2005, the Belmacz in 2013, the Fotografiska in 2016, the Staley-Wise Gallery in 2016, and Galerie56 in 2023

Honored as Turner Classic Movies Star of the Month for April 2019

Honored with a statue of her, "Statue of Integrity," in 2016, located in the forest in Härjedalen

Has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7021 Hollywood Blvd for motion picture

#Greta Garbo#Garbo#The Face of the Century#La Divina#The Swedish Sphinx#Silent Films#Silent Era#Silent Film Stars#Golden Age of Hollywood#Film Classics#Old Hollywood#Vintage Hollywood#Hollywood#Movie Star#Hollywood Walk of Fame#Walk of Fame#Movie Legends#movie stars#1900s#28 Hollywood Legends Born in the 1900s

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

+ I've been busy doing extra assignments and work for another job within the government to transfer to that is much more of a better fit- my next step is to take two forty-five minute French tests, so please light a candle that my French actually holds up in a workplace capacity. 🥲

(Also, I find out about scholarships on Monday, and get my tax return coming up next week hopefully <3)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Bio

Demographics

Faceclaim: Zoe Colletti

Full name: Hope Nicole Jones

Birth date: June 16, 1999

Age: 25 years old

Zodiac: Gemini

Ethnicity: White

Nationality: American

Spoken Languages: English, non fluent French

Height: 5'3 / 160cm

Weight: 160 lbs/ 73 kilos

Eye Color: Hazel Green

Hair Color: Chestnut Brown

Identifying Marks: Freckles all over her body, most prominent on her face, arms and shoulders. A small black stick n poke butterfly tattoo on her left hip. Pierced ears.

Scars: A few she got on accident from falls and such, a large scar on her left calf from being tripped down the bleachers in high school. Small self harm scars on her thighs that have been healed for a few years. A long thin scar down her middle torso from her clavical to navel, as well as scars on her knees and elbows, courtesy of her kidnapper.

Occupation: Pharmacy Technician

Gender Identity/Pronouns: Female, she/her

Sexual Orientation: Bisexual, though she's on the ace spectrum due to trauma.

Backstory

Hope grew up in a small town in Indiana USA. Her father wasn't around much and her mom basically raised her on her own. Her brothers are both nearly a decade older than her and she was the only child in the house by the time she was 9.

She's always been interested in movies, theatre, musicals, and modeling. She'd beg her mother to buy her the magazines on the rack at the grocery store just so she could look at the pretty women.

Despite having such a high regard for herself at a young age, she was still relentlessly bullied in grade school. By the time she hit high school she became a bully herself, often talking down to others and developing a superiority complex.

Hope did have a few friends though, and doesn't consider her experience in school to be that awful. She says it could have always been worse.

She graduated on the honor roll and was class president of her senior year. Despite being able to get a free ride scholarship to Indiana University she turned it down to pursue acting. She tried online college but eventually dropped out.

She remained at her job at the local movie theatre and started to promote herself on social. This brought the attention of a Canadian man, Jonathan Weaver. Or at least that's what he called himself.

He easily manipulated her, making promises of getting her into a modeling career. He began teaching her French and would send her money to buy specific clothes to model for him. Eventually he convinced her to move to Canada.

Hope's mother begged her not to go, but of course Hope didn't listen.

When Hope stepped out of the release gate at the airport, she met the man she'd been talking to for nearly a year. He looked like how he did in the photos, and acted like how he did online.

Unfortunately for her, he drugged the bottle of water he handed to her. He led her back to his apartment, chained her to a radiator and held her captive for 2 weeks. Dressing her up, photographing her, and raping her.

Hope was able to break a pipe and get free one day while Jonathan was out of the apartment. She ran from the building begging for help, barefoot and half naked.

Something in her broke that day and while she was being questioned by police, she lied and gave them false information. Hope wanted revenge on Jonathan, and not the kind that jail time could provide.

Along the way, she started becoming interested in the websites and forums she was posted on while in captivity. Her mind further broke, and she wanted to inflict that kind of pain on others so she wouldn't have to feel it herself.

Hope began making her own content, with any poor girl she could find. She started branching out and soon began to kidnap men.

After some research and digging she found out that a man named Jonathan Weaver didn't exist; At least none that looked like the man that tortured her. The apartment she was held in was abandoned and owned by the local government. There was no trace of her kidnapper.

She remained in Canada and got her citizenship, hoping to one day run into 'Jonathan' and give him a taste of his own medicine.

She works at a shady pharmacy in a downtown area and gets away with stealing small amounts of narcotics. She's gotten good at drugging people inconspicuously and is very active in the nightlife of her city. She's a regular at most of the bars and clubs.

Personality

Good personality traits: Ambitious, confident, friendly, intelligent, loyal, persistent, imaginative, bubbly, cautious

Bad personality traits: argumentative, stubborn, perfectionist, obsessive, spoiled, deceitful, untrusting, anxious

Sense of humor: 'dark', sarcastic, and dry.

Character’s greatest fear: going through what she went through all over again.

Life philosophy: We cannot simply sit and stare at our wounds forever - Haruki Marukami

Greatest strength: Her intelligence and quick wit.

Greatest vulnerability or weakness: Her desire to be loved and her desire for revenge.

Biggest regret: Letting herself be manipulated by a man she'd met online and allowing herself to fall victim to him. She considers herself smart, and felt so stupid when she woke up in that apartment.

Character’s darkest secret: her apathy towards human life. She tries to seem compassionate but in reality she couldn't care less what happened to most people. Hope assisted her friend in committing suicide the summer before their freshman year of high school. She helped string the rope up, and pushed the bucket from under her friend's feet. Hope then cut her down and held her until she turned blue. She has had an odd relationship with death ever since.

MBTI: ENTJ (Commander) is a personality type with the Extraverted, Intuitive, Thinking, and Judging traits. They are decisive people who love momentum and accomplishment. They gather information to construct their creative visions but rarely hesitate for long before acting on them.

Character Alignment: Chaotic Neutral- A chaotic neutral character is an individualist who follows their own heart and generally shirks rules and traditions. Although chaotic neutral characters promote the ideals of freedom, it is their own freedom that comes first; good and evil come second to their need to be free.

Enneagram Type: Type 4 The Individualist- The Sensitive, Introspective Type; Expressive, Dramatic, Self-Absorbed, and Temperamental

Family and Friends

Hometown: Orleans, Indiana, USA

Current Residence: Canada

Pets: none but she'd love to have a cat, and maybe some chickens.

Mother/Relationship with her: Amazing when she was a child but once she hit high school it became somewhat strained. Hope always thought she knew what was best for herself and would ignore her mother or start small arguments over things.

Father/Relationship with him: Nonexistent. He was never around and eventually went missing. No negative feelings, just no feelings at all.

Siblings/Relationship with them: 2 brothers James and Brian, 8 and 10 years older than her. It's a pretty decent relationship with both but there's such a large age gap that they don't have much in common and don't talk outside of pleasantries and catch ups during holidays.

Spouse(s)/Relationship with them: N/A

Children/Relationship with them: N/A

Likes and Dislikes

Favorite Color: Pink, green and purple

Least favorite color: neon green

Favorite Music: pop, indie, and r&b

Least Favorite Music: Post modern country, dubstep

Favorite Food: strawberry cake, cheeseburgers, sesame chicken.

Least Favorite Food: any kind of leafy green. She is adament that she's not a rabbit. She tolerates spinach but only if it's in something like a dip or sandwich. Salads are off the table.

Favorite Genre: Romcoms, documentaries/nonfiction, horror/thriller

Least Favorite Genre: Action, sci-fi although there's exceptions to the rule. She enjoys Star Wars but doesn't like superhero movies.

Habits

Hobbies: reading, shopping, playing dress up, drawing/painting, dancing, jigsaw puzzles and watching movies

Smokes: She hates the smell of cigarettes and weed and is quick to preach the negative effects that smoking causes. She does smoke socially if it will get her close to a new victim though.

Drinks: Hope holds her alcohol well and it takes a few drinks for her to start feeling it. She really likes rum and coke, peach margaritas and lemon drop shots.

Other drugs: She steals half empty vials of morphine from her pharmacy and finds that's the only way she can sleep nowadays. She's done cocaine and molly on occasion with potential victims, but doesn't like that they skew her perception.

Nervous tics: Twirls her hair, bites her nails and picks at her skin when she's anxious or deep in thought. If she's wearing a long sleeve shirt or sweater she'll often pull the sleeves over her hands and pick at the threads.

Traits

Optimist or pessimist?: She tries to be optimistic, but sometimes all she can see is the negativities.

Introvert or extrovert?: Mostly extroverted, but she really likes her alone time too.

Daredevil or cautious?: She was always cautious, and then the one time she decided to take a risk it ended badly, so she's back to walking on eggshells again.

Logical or emotional?: She'd say that logic rules her, but she's quick to fly off the handle if she thinks someone is using her or making fun of her.

Disorderly and messy or methodical and neat?: There is a method to her chaos. It appears messy but it's definitely not dirty. She knows where everything is at and hates when people try to help her clean up.

Prefers working or relaxing?: Hates working unless it's something she wants to do. If it doesn't strike her interest then she wants no part in it.

Confident or unsure of himself/herself?: Acts confident, though there is a little insecurity deep down. Especially about her place in the world. She always trusts her intelligence though.

Animal lover?: Yes, she loves all animals especially cats.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

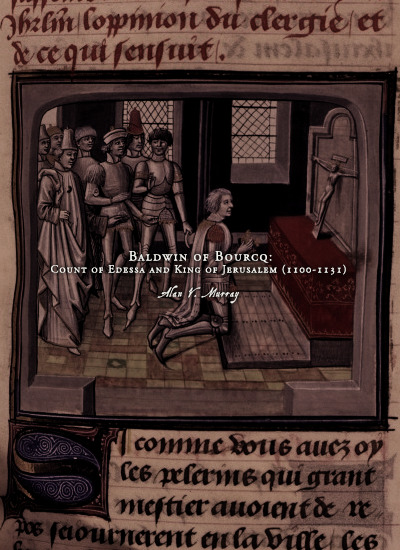

Favorite History Books || Baldwin of Bourcq: Count of Edessa and King of Jerusalem (1100-1131) by Alan V. Murray ★★★★☆

Baldwin of Bourcq first entered the historical record in 1096, when he left his home in northeastern France to join the First Crusade, the great expedition summoned in late November 1095 by Pope Urban II for the liberation of the holy sites and Christian peoples of Syria and Palestine from the domination of the Muslim Turks. After the crusaders took Jerusalem on 15 July 1099 most of them returned to their homes in the West, but a minority remained in the newly founded principalities in the Near East which came to be collectively known as Outremer, an Old French name meaning ‘[the land] beyond the sea’. Baldwin was one of those crusaders who chose to seek their fortunes in the East. In 1100 he unexpectedly succeeded to the county of Edessa, a new Christian principality carved out of territories seized from Turkish control in north-eastern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, in what is now southeastern Turkey. There he ruled over a diverse population of Armenians, Syrian Christians and immigrant Europeans for almost two decades. In 1118 he was called to take up the succession in the kingdom of Jerusalem, where he ruled for over twelve years. By the time he had reached middle age, Baldwin had gone from being a minor nobleman in France to one of only a dozen kings in Western Christendom. Until now, Baldwin’s biography has never been written. In the Middle Ages it was Godfrey of Bouillon, the first Latin ruler of Jerusalem, who rapidly came to be regarded as the great chivalric hero of the crusade, and his medieval reputation was reflected in modern historiography. Because Godfrey’s life before the crusade is reasonably well documented, it also attracted the attention of historians of Lotharingia as well as of the crusades and Outremer. By comparison his brother and successor King Baldwin I was neglected in modern scholarship, but recent research has established him as the real founder of the kingdom of Jerusalem. Whether as count of Edessa or king of Jerusalem, Baldwin II (as he is numbered in both cases) received less attention than either of his predecessors in historical research of the nineteenth and most of the twentieth centuries. However, three significant facets of his reign in Jerusalem have emerged in research of the last fifty years. Firstly, Hans Eberhard Mayer’s work on the royal chancery and the charters of the kings and queens of Jerusalem has not only provided a magnificent edition of Baldwin’s documents, but also shown how his tenure of the regency of the principality of Antioch caused significant problems for the government of his own kingdom. Secondly, prosopographical research has highlighted the importance of Baldwin’s family connections in France after he settled in the East. And thirdly, my own earlier work has made clear the importance of the attempt to depose Baldwin while he was a captive of the Turks in 1123, and the effect this had on his subsequent policies.

#historyedit#litedit#baldwin ii of jerusalem#french history#asian history#european history#medieval#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Léon Damas (March 28, 1912 - April 22, 1978) was a poet, editor, diplomat, and cultural theorist who was born in Cayenne, French Guiana. He was the youngest of five children born to parents Ernest and Marie Aline Damas.