#françois guizot

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Battle of Agincourt by Alphonse de Neuville

#alphonse de neuville#art#battle of agincourt#azincourt#france#medieval#middle ages#chivalry#knights#knight#cavalry#hundred years war#french#english#england#history#europe#european#horses#armour#mediaeval#nobility#françois guizot

581 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vercingetorix Before Caesar, illustration by Alphonse de Neuville for The History of France: From the Most Remote Times to 1789 by François Guizot (1872)

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Guizot on Progress as the Measure of Civilization

Friday 04 October 2024 is the 237th anniversary of the birth of François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (04 October 1787 – 12 September 1874), who was born in Nîmes, France, on this date in 1787, and who went on to hold many of the highest political offices in France.

Guizot led a long and eventful life that involved both extensive literary work and engagement with the political life of his time. His histories of European civilization and French civilization are distinctive in their transmutation of the Enlightenment theme of progress, which Guizot re-interprets in the light of nineteenth century experience.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Text post: https://geopolicraticus.substack.com/p/guizot-on-progress-as-the-measure

Video: https://youtu.be/a0jFYDbEhis

Podcast: https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/NlEPhXairNb

#philosophy of history#youtube#François Guizot#progress#Enlightenment#civilization#Protestantism#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Little Beggar, c. 1808-09, Napoleonic era

By Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot, French

The Little Beggar is one of the earliest known works by the artist, who arrived in Rome a few months after her professor, Guillaume Guillon-Lethière, had been appointed director of the Academy of France in its new home in the Villa Medici. The subject is exceptional in showing a beggar in such a compassionate light; while he is clearly asking the viewer for money, he is a sympathetic, not a threatening figure, reflecting a significant change of attitude towards the less fortunate.

Literature

François Guizot, De l’état des Beaux-Arts en France et du Salon de 1810, Paris, Maradan, 1810, p. 99

Pierre François Gueffier, Entretiens sur les ouvrages de peinture, sculpture et gravure, exposés au Musée Napoléon en 1810, Paris, Gueffier jeune, 1811, p. 157

C. P. Landon, Salon de 1810, p.104

Paul Menoux, Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot, Catalogue Raisonné, Paris, Arthena (to be published).

TEFAF Maastricht

#Hortense Haudebourt-Lescot#Le Petit Mendiant#TEFAF Maastricht#TEFAF#maastricht#19th century#napoleonic era#napoleonic#art#women artists#neoclassical#1808#1809#19th century art#female artists#female painters#women in art#auction#auctions

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the early twentieth century, Henry Goodell, president of what was then the Massachusetts Agricultural College, celebrated "the work of these grand old monks during a period of fifteen hundred years. They saved agriculture when nobody else could save it. They practiced it under a new life and new conditions when no one else dared undertake it." Testimony on this point is considerable. "We owe the agricultural restoration of a great part of Europe to the monks," observes another expert. "Wherever they came," adds still another, "they converted the wilderness into a cultivated country; they pursued the breeding of cattle and agriculture, labored with their own hands, drained morasses, and cleared away forests. By them Germany was rendered a fruitful country." Another historian records that "every Benedictine monastery was an agricultural college for the whole region in which it was located.”1 Even the nineteenth-century French statesman and historian François Guizot, who was not especially sympathetic to the Catholic Church, observed: "The Benedictine monks were the agriculturists of Europe; they cleared it on a large scale, associating agriculture with preaching.”2

- Thomas E. Woods Jr., Ph.D., “How the Monks Saved Civilization,” How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization

—

1. Alexander Clarence Flick, The Rise of the Medieval Church (New York: Burt Franklin, 1909), 216.

2. See John Henry Cardinal Newman, Essays and Sketches, vol. 3, Charles Frederick Harold, ed. (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1948), 264-65.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of France from the earliest times to 1848 / by M. Guizot amd Madame Guizot de Witt ; translated by Robert Black.

Description

Tools

Cite this

Main AuthorGuizot, (François), M. 1787-1874.Related NamesBlack, Robert, 1830?-1915. Witt, (Henriette Elizabeth), Madame de 1829-1908. Language(s)English PublishedNew York : J. B. Alden, 1884. SubjectsFrance > France / History. NoteIncludes index in vol. 8. Physical Description8 v. : ill., plates, ports. ; 20 cm.

APA Citation

Guizot, M. (François)., Black, R., Witt, M. de (Henriette Elizabeth). (1884). The history of France from the earliest times to 1848. New York: J. B. Alden

1 note

·

View note

Text

O surgimento da impressão em meados do século XV foi um evento de grande ruptura para o mundo ocidental. Seu impacto, extremamente amplo, prenuncia o nascimento de uma cultura impressa que ainda permanece, pois estabelece as condições para o nascimento da mídia, tem implicações na vida social, na história das línguas, das ciências, da educação, das artes gráficas, entre outros. Mas o que, de fato, sabemos sobre a invenção de Gutenberg, e por que meios, essa tecnologia foi aperfeiçoada a ponto de permitir o estabelecimento de um novo ecossistema de comunicação, produção e circulação de textos e, consequentemente, de ideias? Desta forma, o CPF Sesc promove a palestra, que abordará a extraordinária história do livro, da invenção da escrita à revolução digital. Realizada por ocasião do lançamento do livro História do Livro e da Edição, publicação em coedição pelas Edições Sesc e Ateliê Editorial. Data: 18/09/2023 Dias e Horários: Segunda, 19h30 às 21h30. Curso Presencial Inscrições a partir das 14h do dia 28/8, até o dia 18/9. Enquanto houver vagas. Local Rua Dr. Plínio Barreto, 285 - 4º andar} Bela Vista - São Paulo. Grátis Palestrantes Marisa Midori Deaecto Professora livre-docente em História do Livro na Escola de Comunicações e Artes (ECA-USP). Doutora Honoris Causa pela Universidade Eszterházy Károly, Eger (Hungria). Autora de “Império dos Livros - instituições e práticas de leituras na São Paulo oitocentista” (Edusp/Fapesp, 2011; 2019), vencedor do prêmio Jabuti da CBL (1º lugar em Comunicação) e o Prêmio Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, pela Fundação Biblioteca Nacional do Rio de Janeiro na categoria melhor ensaio social. Publicou, recentemente, “História de um livro. A Democracia na França, de François Guizot” (Ateliê Editorial, 2021) e organizou a edição bilíngue de “Bibliodiversidade e preço do livro. Da Lei Lang à Lei Cortez. Experiências e expectativas em torno da regulação do mercado editorial (1981-2021)” (Ateliê Editorial, 2021). Yann Sordet Historiador do livro e curador geral de bibliotecas na França (Paris). Formou-se na École Nationale des Chartes (turma de 1997), depois na École Nationale Supérieure des Sciences de l'Information et des Libraries (ENSSIB). Foi curador do Departamento de Manuscritos e Livros Raros da Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (1998-2009), e, desde 2011, é diretor da Biblioteca Mazarina, a biblioteca pública mais antiga da França. Desde 2021, é Diretor Geral das Bibliotecas do Institut de France. Suas pesquisas concentram--se na história das bibliotecas e da bibliofilia, nas práticas bibliográficas, nos incunábulos, na produção e distribuição de livros sobre espiritualidade nos tempos modernos, bem como em edição de música. Lecionou história da edição na Universidade de Paris XIII (1999-2006) e história das bibliotecas na École Pratique des Hautes Etudes (2007-2009). É encarregado pelos cursos de formação na área patrimonial junto à ENSSIB. É editor-chefe da revista Histoire et Civilisation du Livre. Publicou recentemente História do Livro e da Edição: Produção e Circulação, Formas e Mutações (Paris, Albin Michel, 2021, posfácio de Robert Darnton), atualmente em tradução no Brasil. (Foto: Acervo Pessoal) Sobre o CPF Sesc Com uma programação bastante diversa, o Centro de Pesquisa e Formação do Sesc São Paulo (CPF Sesc), localizado na Bela Vista, promove uma série de encontros, cursos, vivências, lançamentos de livros, ciclos, seminários e outras atividades. Muitas dessas atrações, que acontecem de forma presencial ou online, têm entrada gratuita e outras custam até R$50. As inscrições podem ser no site do CPF Sesc ou presencialmente na unidade. Serviço Centro de Pesquisa e Formação – CPF Sesc Rua Dr. Plínio Barreto, 285 – 4º andar. Tel: 3254-5600 Programação completa em https://centrodepesquisaeformacao.sescsp.org.br/

0 notes

Text

wikipedia fact

He had an unusually strong and fascinating personality -- I never met anyone even remotely coming close to what he was like. Just to give you an idea: he was all that one might associate with François Guizot, very much aloof, very intelligent, both impossible to get close to and yet very much accessible and blessed with the rhetorical powers of a Pericles. If he had decided for a political career, the recent history of my country would have been completely different from what it is now. It rarely happened, but if he really felt that this was necessary he could raise a rhetorical storm blowing away everything and everybody. Indeed, when thinking of him, I never am sure what impressed me most, his scholarship or his personality. He was a truly wonderful man.

0 notes

Text

“Le Quai d’Orsay”

Le quai d'Orsay court le long de la Rive Gauche de la Seine, embrassant la totalité du 7ème arrondissement (bien avant la répartition actuelle des arrondissements de Paris, actée en 1860). De fait, les travaux de construction du quai d'Orsay débutent en 1707, lors de la présidence du Parlement de Paris par le Prévôt des Marchands de l'époque: Charles Boucher, seigneur d'Orsay, qui lui laissa son nom. Bien plus tard, deux parties du quai furent renommées, à l'ouest quai Branly en 1941, à l'est quai Anatole-France en 1947. Depuis, la première adresse officielle du quai d'Orsay devient le Palais Bourbon, siège de l'Assemblée nationale. Séparé de celui-ci par l'Hôtel de Lassay, résidence du président de l'Assemblée, se trouve un bâtiment voué à abriter les services diplomatiques et des relations extérieures de la France : l'Hôtel du ministre des Affaires étrangères.

Le ministère des Affaires étrangères trouve son origine en 1547, lors de la nomination par le roi Henri II de Claude de l'Aubespine comme secrétaire d'Etat des Affaires étrangères. Passant de ministère des Relations extérieures à celui des Affaires étrangères (aléatoirement, en fonction des changements de gouvernements), ce ministère régit la politique extérieure de la France ainsi que ses relations avec les autres États, via ses représentations diplomatiques implantées à l'étranger que sont ambassades et consulats. La construction de cet Hôtel abritant ses services fut décidée par le ministre François Guizot dès 1844, sous la Monarchie de Juillet. Retardés par la révolution de 1848, les travaux sont finalement achevés en 1856, sous le Second Empire, ce qui explique son style dit "Napoléon III", adapté par son architecte Jacques Lacornée. Destiné à accueillir souverains et diplomates étrangers, une grande attention a été apportée à sa décoration, intérieure comme extérieure, souhaitant être représentative du faste de la France. Ses salons d'apparat, au lustre (et aux lustres!) éclatant(s), accueillirent nombre de délégations, sous un Second Empire finissant puis sous 3 républiques lui succédant. En 1856, le Traité de Paris, mettant un terme à la Guerre de Crimée, fut signé dans la "galerie de la Paix". En 1938, des salles de bains royales sont créées dans le "Style paquebot" (inspiré par l'architecture de luxe des transatlantiques de l'Entre-Deux-Guerres), dernière expression -avant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale- du mouvement Art Déco, à l'occasion de la visite du roi George VI et de son épouse la reine Elizabeth. Le 9 mai 1950, Robert Schuman (alors ministre des Affaires étrangères de la IVème République), prononça au salon de l'Horloge sa fameuse déclaration éponyme, considérée depuis comme l'acte fondateur de la construction européenne. Chaque année, le 9 mai est d'ailleurs fêté comme étant la "Journée de l'Europe".

Sa façade, héritière du précédent style néoclassique (en vogue sous la Restauration monarchique puis sous Louis-Philippe), nous présente moult colonnes engagées et pilastres ioniques, soutenant un attique plat, inspiré des toits-terrasses des palais italiens. Côté jardin (bordé par la rue de l'université), sa façade s'inspire de l'architecture palladienne. Côté Seine (Quai d'Orsay, sic), quinze médaillons en marbre blanc, nus aujourd'hui, sont des témoins de l'adjonction de la construction européenne au ministère des Affaires étrangères. En effet, en 1995, l'Europe étant constituée alors de 15 états-membres, quinze bas-reliefs en marbre furent créés, représentant chacun un des pays membres de l'U.E. L'élargissement de l'Europe à d'autres États, dès 1997, rendirent caduque ce nombre de quinze; ils furent alors déposés, chacun ayant été offert à l'ambassade française correspondante sur le territoire de ces dits (quinze) États. Le ministère se nomme officiellement depuis "de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères".

La cocarde diplomatique française, aux cercles concentriques "Bleu-Blanc-Rouge", arborant le sigle R.F. (République Française), est présente partout sur le bâtiment, ainsi que sur son portail, comme à chaque entrée d'ambassade ou de consulat français à l'étranger.

Par métonymie, le "Quai d'Orsay" est devenu l'appellation consacrée de la diplomatie française. Une célèbre bande-dessinée prit ce nom (sous-titrée Chroniques diplomatiques), co-écrite en 2010/11 par l'ancien diplomate Antoine Baudry, adaptée au cinéma par Bertrand Tavernier en 2013, avec Thierry Lhermitte dans le rôle-titre, pastiche assumé du ministre Dominique de Villepin, d'une décade antérieure.

A l'extrémité orientale de la grille de l'Hôtel se trouve un monument dédié à Aristide Briand, qui exerça (entre autres charges gouvernementales d'importance) plusieurs mandats de ministre des Affaires étrangères sous la IIIème République, notamment dans les années 20, où il déploya toute son énergie dans la réconciliation entre les nations belligérantes, au sortir de la Première Guerre Mondiale. Récipiendaire du Prix Nobel de la Paix en 1926 pour son rôle joué dans les Accords de Locarno, appliquant le concept de sécurité collective en Europe, il fut également, avec l'américain Frank Billings Kellogg, à l'origine du Pacte de Paris, signé en cet Hôtel le 27 août 1928, dans le même salon de l'Horloge qui connaîtra le déclaration Schuman en 1950. Visant à mettre la guerre "hors-la-loi", ce pacte inspira à l'Etat ce monument, orchestré par l'architecte Paul Bigot, réunissant les ciseaux de Paul Landowski pour la sculpture en ronde-bosse représentant "la Paix entre les Nations" et d'Henri Bouchard pour le bas-relief sur plaque de bronze, montrant "La procession des Nations", conduite par la France, écoutant le message de conciliation d'Aristide Briand, à droite au premier plan. Ce groupe sculpté pour la paix, inauguré en 1937, ne fut représentatif que d'une courte période d'illusion de paix, dûe à un diplomate utopiste à la construction idéaliste finalement freinée par la crise économique de 1929, puis par la montée des totalitarismes en Europe au début des années 30... Nous connaissons la suite... Mais la paix, malgré tout, fut finalement restaurée sur le territoire français dès juin 1944. Après quatre longues années d'occupation, Paris est finalement libérée le 25 août, au prix de nombreux actes de guerre héroïques, notamment lors des rudes combats pour la libération du ministère, tenu par les nazis. Cinq soldats français de la 2ème D.B. trouvèrent ici la mort dans l'explosion du char "Quimper". Le prix de la liberté...

Crédits : ALM's

#monument#ministre#ministère#affaires étrangères#diplomatie#relations extérieures#Aristide Briand#François Guizot#Traité de Paris#Pacte de Paris#Robert Schuman#Second Empire#République Française#architecture#sculpture#cocarde#photo#photooftheday#bas-relief#paix#liberté#libération#accords#Europe#bande-dessinée#photography#cinéma#7ème#Quai d'Orsay#médaillon

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PICK A DECADE → the 1830s (requested by musicalheart168)

#musicalheart168#historyedit#perioddramaedit#*decades#mine#*#louis philippe i#adolphe thiers#françois guizot#EH who would have bet that LP's son got even the tiniest portrayal#before napoleon's does#*slams the head on the wall*#blood tw#death tw

446 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Histoire générale de la civilisation en Europe est un livre écrit par l'historien, homme politique et académicien français François Guizot.

0 notes

Text

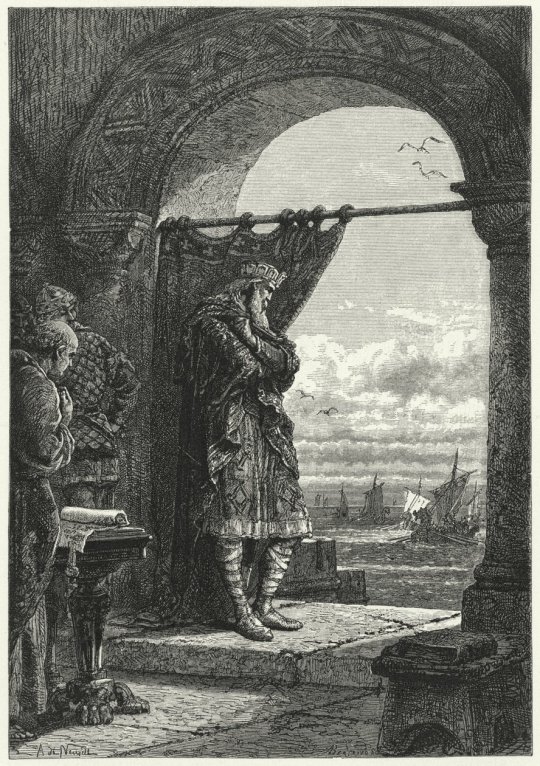

Charlemagne anxiously observes the approach of ships carrying Norman raiders by Alphonse de Neuville

#alphonse de neuville#art#charlemagne#normans#raiders#francia#france#paris#french#vikings#viking#franks#frankish#germanic#carolingian#history#medieval#middle ages#europe#european#viking age#mediaeval#norman#pirates#marauders#raid#holy roman empire#holy roman emperor#françois guizot#carolingian empire

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday, Marshal Soult!

This is probably a rather weird birthday post. Also, it has little to do with Napoleon. But as it sums up Soult’s life in a way, I do find it strangely appropriate: Soult’s letter of resignation to King Louis Philippe (quoted and translated from L. Muél, »Gouvernements, ministères et constitutions de la France«, 2nd edition, Paris 1891, and the memors of François Guizot).

Soult-Berg (Tarn), 15 September 1847.

Sire,

I was at the service of my country, sixty-three years ago, when the old monarchy was still standing, before the first glimmers of our national revolution. A soldier of the Republic and a lieutenant of the Emperor Napoleon, I took part unceasingly in this immense struggle for the independence, liberty and glory of France, and I was one of those who supported it until the last day. Your Majesty deigned to believe that my services could be useful in the new and no less patriotic struggle which God and France have called upon her to wage for the consolidation of our constitutional order; I thank Your Majesty for this. It is the honour of my life that my name thus occupies a place in all the military and civil activities which have assured the triumph of our great cause. Your Majesty's confidence supported me in the last services which I tried to render. My devotion to Your Majesty and to France is absolute; but I feel that my strength betrays this devotion. May Your Majesty allow me to devote what is left of it to recollection, having reached the end of my laborious career. I have dedicated to you, Sire, the activity of my last years; give me the respite from my old services, and allow me to deposit at the foot of Your Majesty's throne my resignation from the presidency of the Council with which Your Majesty had deigned to invest me. I shall enjoy this repose amidst the general safety which Your Majesty's firm wisdom has given to France and to all those who have served your Majesty and who love him. My gratitude for Your Majesty's kindnesses, my wishes for His prosperity and that of His august family will follow me in this rest until my last day; they will not cease to equal the unalterable devotion and the profound respect with which I am

Sire, of Your Majesty, the most humble and obedient servant,

Maréchal Duc de Dalmatie.

At the time he wrote this, Soult was 78 years old. He would live for another three years. As to Louis Philippe’s July Monarchy, it would last for another five months after Soult’s resignation – it’s almost as if everybody had just waited for him to leave. In February 1848, the monarchy was overthrown, and the Second French Republic installed - who, another four months later, would bloodily oppress the workers’ uprisings, killing 5,000 and incarcerating over 10,000, and who in December of the same year 1848 already would elect a certain Louis Napoléon Bonaparte as president, thus paving the way for the Second Empire.

Soult died six days before future Napoleon III’s coup d’état.

By the way, his letter of resignation would be commented on in a book called »Histoire de la révolution de 1848 et de la présidence de Louis-Napoléon«, Paris 1850, as follows:

[…] On September 19 the Moniteur published long awaited news: in a letter to the king, in which the courtier can be found in its entirety, Marshal Soult resigned from his functions as president of the council, justifying his decision on the grounds of his old age and his urgent need to rest in the general safety that the wisdom of Louis Philippe had given to France! This meant closing with a lie a career which had originally been glorious, but which had been seriously compromised by a passion for gain, by a restless ambition and by servile complacency.

#napoleon's marshals#not the prettiest birthday present#jean de dieu soult#letter of resignation#four eras ancien regime revolution empire july monarchy#happy birthday marshals

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Có câu nói nào thực sự khiến bạn khắc cốt ghi tâm không?

1. Dazai Osamu《Chim di cư》:

“Người nhạy cảm sẽ thông cảm được với đau khổ của người khác, tự nhiên sẽ không thể tùy tiện mà thẳng thắn. Cái gọi là thẳng thắn, thực ra chính là bạo lực.”

2. Giáo sư của trường kinh doanh Havard nói với những học sinh tốt nghiệp về việc kiên trì ước mơ:

Nếu bạn muốn làm việc mình thích, thì họp lớp sau 5 năm tốt nghiệp, bạn đừng đi, bởi vì lúc đó bạn đang ở thời khắc gian khổ nhất, mà bạn học của bạn, phần nhiều là đang ở công ty lớn một một bước lên mây. Tương tự họp lớp 10 năm, bạn cũng đừng đi. Thế nhưng, họp lớp 20 năm, bạn có thể đi, bạn sẽ thấy, những người kiên trì ước mơ và những người nước chảy bèo trôi, cuộc đời sẽ có gì khác nhau.

3. Nguyên nhân bạn mơ hồ là do đọc sách quá ít mà nghĩ quá nhiều. -Dương Giáng

4. Cái gọi là trưởng thành, chính là độc lập về cuộc sống, có suy nghĩ và năng lực độc lập để tự mình phấn đấu. Cái gọi là chín chắn, chính là tự mình loại bỏ được sự ngạo mạn bên trong và thành kiến bên ngoài. — Thạch Thuật Tư

5. Bạn hỏi tôi có sự tiến bộ nào ư? Tôi bắt đầu trở thành người bạn của chính mình. — Alain de Botton

6. Một đời này của chúng ta rất ngắn, chúng ta cuối cùng rồi sẽ mất đi, vì vậy đừng ngại mà dũng cảm hơn một chút. Yêu một người, trèo một ngọn núi, theo đuổi ước mơ. Có rất nhiều việc không có câu trả lời.

7. Bạn mới 25 tuổi, bạn có thể trở thành bất cứ người nào mà bạn muốn. —《 Vững bước 》

8. Bất hạnh của tôi, hoàn toàn là do tôi thiếu năng lực từ chối. Tôi sợ một khi từ chối người khác, sẽ để lại trong lòng nhau một vết nứt vĩnh viễn không có cách hàn gắn được.

— Dazai Osamu《 Thất lạc cõi người 》

9. Bạn có thể có tất cả, nhưng không thể đồng thời. — Marilyn Monroe

10. Học tập không phải để hùng biện hay bác bỏ, cũng không phải để cả tin hay hùa theo, mà để suy xét và cân nhắc. — Francis Bacon

11. Quan trọng nhất là, đầu tiên chúng ta phải lương thiện, thứ hai phải trung thực, tiếp theo mới là sau này vĩnh viễn không được quên nhau. — Dostoevsky

12. Nếu bạn có thể trong lúc lãng phí tìm được niềm vui, thì đó không phải lãng phí thời gian.

— Bertrand Russell

13. Ngoài thanh xuân trong tay, bạn cái gì cũng không có, nhưng chính những thứ ít ỏi trong tay b��n này, quyết định bạn là người như thế nào.

—J.M.Coetzee

14. Chỉ thông minh thôi chưa đủ, còn cần có đủ sự thông minh để tránh thông minh quá mức.

15. Tôi có lẽ sẽ nói với bạn, nhất thiết đừng kết hôn, trừ phi bạn không kìm lòng được, trừ phi bạn thực sự say mê. Đó mới là toàn bộ ý nghĩa của cuộc sống. — Robert Frost

16. Nếu ai cũng có thể hiểu bạn, thì bạn đã trở nên bình thường đến mức nào rồi.

17. Một trong những biểu hiện của một người trưởng thành, chính là hiểu rõ 99% những chuyện xảy ra với mình hàng ngày, những lời của người khác căn bản không có ý nghĩa. — Mark Bauerlein

18. Tiện tay nhấn like là đạo đức tốt. — Lỗ Tấn

19. Khi bạn già rồi, nhìn lại một đời, sẽ phát hiện: Khi nào ra nước ngoài học tập, khi nào quyết định làm công việc đầu tiên, vào lúc nào lựa chọn được đối tượng để yêu đương, khi nào kết hôn, thực ra đều là bước ngoặt của cuộc đời. Chỉ là lúc đó đứng ở ngã ba đường, nhìn thấy phong ba bão táp, ngày mà bạn đưa ra quyết định, ở trên nhật ký, vô cùng lặng lẽ và tầm thường, lúc đó còn tưởng rằng là một ngày bình thường trong cuộc đời của mình.

— Đào Kiệt

20. Tôi quay rất nhiều bi kịch, nhưng các bạn đều nói đó là hài kịch. — Châu Tinh Trì

21. Tôi dùng tất cả sức lực, sống một đời bình thường. —《 Mặt trăng và đồng xu 》

22. Lời nói dối tệ hại nhất, chính là người bạn yêu tin tưởng lời nói dối của bạn. —《 Horace and Pete 》

23. Hôm nay không muốn chạy, vì vậy mới chạy. Đây mới là cách suy nghĩ của người chạy đường dài. — Murakami Haruki

24. Con người sở dĩ lời nói chính xác, là vì hiểu biết quá ít. — François Guizot

25. Người ta thường nói thời gian có thể thay đổi rất nhiều thứ, nhưng trên thực tế phải do chính bạn thay đổi những thứ đó. — Andy Warhol

26. Tôi càng cô độc, càng không có bạn bè, càng không có sự ủng hộ nào, tôi càng phải tôn trọng bản thân mình hơn. — Charlotte Brontë

27. Tất cả đau khổ của con người, về bản chất đều là sự căm phẫn về những thứ bản thân không làm được. — Vương Tiểu Ba

28. Chúng ta chỉ là quá bận mà thôi, bận đến mức những chuyện tốt đẹp lướt qua người mà cũng không hay biết.

29. Khi tôi vẫn còn trẻ, chưa có sự từng trải, bố tôi dạy bảo tôi một câu, đến bây giờ tôi vẫn nhớ mãi không quên. 'Mỗi khi con muốn phê bình người khác', ông ấy nói với tôi 'con phải nhớ, tất cả mọi người trên thế giới này, không phải ai cũng có điều kiện tốt giống như con.'

— F. Scott Fitzgerald《 Gatsby vĩ đại 》

30. Cuộc sống chẳng có ý nghĩa gì cả, nhưng nếu sống thì có lẽ sẽ gặp được những chuyện có ý nghĩa, giống như anh gặp được đoá hoa đó, giống như anh gặp được em. —《 Naruto 》

Nguồn: Zhihu | Kim Anh dịch

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

François Guizot saying "Get rich, then you can vote" has the same energy as Yzma saying "Maybe you should have thought about that before becoming peasants!"

#french history#discoveries from my history teacher's university Western Civilization textbook that she lent me#reading this is so fun#also I feel very academic#francois guizot#is that even a tag on tumblr???

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

François-Pierre-Guillaume Guizot, Honoré-Victorin Daumier, 1827, Art Institute of Chicago: European Painting and Sculpture

Gift of Samuel and Marie Louise Rosenthal - Rosenthal-Daumier Collection Size: H. 21.3 cm (8 3/8 in.) Medium: Bronze

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/152772/

3 notes

·

View notes