#folk music history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

And with that, the bracket comes to an end with The Turtle Dove as the top song in the TURN fandom.

Thank you all for participating!

youtube

#turn music bracket#turn washingtons spies#turn amc#turn: washington's spies#music history#folk music history#18th century music#folk music#the turtle dove#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Discover the magic of A Complete Unknown, James Mangold’s biopic of Bob Dylan starring Timothée Chalamet. From Dylan’s rise in the 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene to his controversial electric transition at the Newport Folk Festival, this film captures the music, relationships, and cultural upheaval of a generation. With stunning performances by Chalamet, Edward Norton, Monica Barbaro, and Elle Fanning, this cinematic journey is not to be missed. Join us as we break down the film’s highlights, its flaws, and its unforgettable moments.

#bob dylan biopic#timothée chalamet bob dylan#a complete unknown review#james mangold movies#folk music history#greenwich village folk scene#elle fanning suze rotolo#monica barbaro joan baez#bob dylan newport folk festival#bob dylan electric guitar#movie reviews 2024#best biopics of 2024#music history movies#iconic bob dylan moments#james mangold director#Youtube

0 notes

Text

the appalachian murder ballad <3 one of the most interesting elements of americana and american folk, imo!

my wife recently gave me A Look when i had one playing in the car and she was like, "why do all of these old folk songs talk about killing people lmao" and i realized i wanted to Talk About It at length.

nerd shit under the cut, and it's long. y'all been warned

so, as y'all probably know, a lot of appalachian folk music grew its roots in scottish folk (and then was heavily influenced by Black folks once it arrived here, but that's a post for another time).

they existed, as most folk music does, to deliver a narrative--to pass on a story orally, especially in communities where literacy was not widespread. their whole purpose was to get the news out there about current events, and everyone loves a good murder mystery!

as an aside, i saw someone liken the murder ballad to a ye olde true crime podcast and tbh, yeah lol.

the "original" murder ballads started back across the pond as news stories printed on broadsheets and penned in such a way that it was easy to put to melody.

they were meant to be passed on and keep the people informed about the goings-on in town. i imagine that because these songs were left up to their original orators to get them going, this would be why we have sooo many variations of old folk songs.

naturally then, almost always, they were based on real events, either sung from an outside perspective, from the killer's perspective and in some cases, from the victim's. of course, like most things from days of yore, they reek of social dogshit. the particular flavor of dogshit of the OG murder ballad was misogyny.

so, the murder ballad came over when the english and scots-irish settlers did. in fact, a lot of the current murder ballads are still telling stories from centuries ago, and, as is the way of folk, getting rewritten and given new names and melodies and evolving into the modern recordings we hear today.

305 such scottish and english ballads were noted and collected into what is famously known as the Child Ballads collected by a professor named francis james child in the 19th century. they have been reshaped and covered and recorded a million and one times, as is the folk way.

while newer ones continued to largely fit the formula of retelling real events and murder trials (such as one of my favorite ones, little sadie, about a murderer getting chased through the carolinas to have justice handed down), they also evolved into sometimes fictional, (often unfortunately misogynistic) cautionary tales.

perhaps the most famous examples of these are omie wise and pretty polly where the woman's death almost feels justified as if it's her fault (big shocker).

but i digress. in this way, the evolution of the murder ballad came to serve a similar purpose as the spooky legends of appalachia did/do now.

(why do we have those urban legends and oral traditions warning yall out of the woods? to keep babies from gettin lost n dying in them. i know it's a fun tiktok trend rn to tell tale of spooky scary woods like there's really more haints out here than there are anywhere else, but that's a rant for another time too ain't it)

so, the aforementioned little sadie (also known as "bad lee brown" in some cases) was first recorded in the 1920s. i'm also plugging my favorite female-vocaist cover of it there because it's superior when a woman does it, sorry.

it is a pretty straightforward murder ballad in its content--in the original version, the guy kills a woman, a stranger or his girlfriend sometimes depending on who is covering it.

but instead of it being a cautionary 'be careful and don't get pregnant or it's your fault' tale like omie wise and pretty polly, the guy doesn't get away with it, and he's not portrayed as sympathetic like the murderer is in so many ballads.

a few decades after, women started saying fuck you and writing their own murder ballads.

in the 40s, the femme fatale trope was in full swing with women flipping the script and killing their male lovers for slights against them instead.

men began to enter the "find out" phase in these songs and paid up for being abusive partners. women regained their agency and humanity by actually giving themselves an active voice instead of just being essentially 'fridged in the ballads of old.

her majesty dolly parton even covered plenty of old ballads herself but then went on to write the bridge, telling the pregnant-woman-in-the-murder-ballad's side of things for once. love her.

as a listener, i realized that i personally prefer these modern covers of appalachian murder ballads sung by women-led acts like dolly and gillian welch and even the super-recent crooked still especially, because there is a sense of reclamation, subverting its roots by giving it a woman's voice instead.

meaning that, like a lot else from the problematic past, the appalachian murder ballad is something to be enjoyed with critical ears. violence against women is an evergreen issue, of course, and you're going to encounter a lot of that in this branch of historical music.

but with folk songs, and especially the murder ballad, being such a foundational element of appalachian history and culture and fitting squarely into the appalachian gothic, i still find them important and so, so interesting

i do feel it's worth mentioning that there are "tamer" ones. with traditional and modern murder ballads alike, some of them are just for "fun," like a murder mystery novel is enjoyable to read; not all have a message or retell a historical trial.

(for instance, i'd even argue ultra-modern, popular americana songs like hell's comin' with me is a contemporary americana murder ballad--being sung by a male vocalist and having evolved from being at the expense of a woman to instead being directed at a harmful and corrupt church. that kind of thing)

in short: it continues to evolve, and i continue to eat that shit up.

anyway, to leave off, lemme share with yall my personal favorite murder ballad which fits squarely into murder mystery/horror novel territory imo.

it's the 10th child ballad and was originally known as "the twa sisters." it's been covered to hell n back and named and renamed.

but! if you listen to any flavor of americana, chances are high you already know it; popular names are "the dreadful wind and rain" and sometimes just "wind and rain."

in it, a jealous older sister pushes her other sister into a river (or stream, or sea, depending on who's covering it) over a dumbass man. the little sister's body floats away and a fiddle maker come upon her and took parts of her body to make a fiddle of his own. the only song the new fiddle plays is the tale about how it came to be, and it is the same song you have been listening to until then.

how's that for genuinely spooky-scary appalachia, y'all?

#appalachia#appalachian murder ballads#murder ballads#appalachian music#appalachian culture#appalachian history#appalachian#appalachian folklore#appalachian gothic#tw violence against women#cw violence against women#cw murder#tw murder#folk music#folk#txt

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

george harrison and stevie nicks, 1977.

#vintage#60s 70s 80s 90s#retro#history#vintage photography#hollywood#vintage aesthetic#film#1970s#70s aesthetic#70s music#70s fashion#stevie nicks#stevie nicks aesthetic#george harrison#the beatles#folk music#70s#it actually might be 78 or 79 but most sources say 77

640 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Performers In Country, Bluegrass, & Folk Music

Books:

Hidden in the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music by Diane Pecknold {2013}

Country Soul: Making Music And Making Race In The American South by Charles L. Hughes {2015}

The Banjo: America’s African Instrument by Laurent Dubois {2016} x

Pride: The Charley Pride Story by Charley Pride & Jim Henderson {1994}

Deford Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music by David C. Morton & Charles K. Wolfe {1991}

My Country: The African Diaspora’s Country Music Heritage by Pamela E. Foster {1998}

My Country, Too: The Other Black Music by Pamela E. Foster {2000}

Say It One More Time For The Brokenhearted by Barney Hoskyns {1987}

African Banjo Echoes In Appalachia: A Study of Folk Traditions by Cecelia Conway {1995}

Buried Country: The Story of Aboriginal Country Music by Clinton Walker {2015}

Hoedowns, Reels, And Frolics: Roots And Branches Of Southern Appalachian Dance - Phil Jamison {2015}

Black Country Music: Listening For Revolutions by Francesca T. Royster {2022}

Well Of Souls: Uncovering The Banjo's Hidden History by Kristina R. Gaddy {2022}

Documentary:

Rhythm, Country & Blues {1994}

Waiting In The Wings: African Americans In Country Music 1, 2, 3 {2004}

The Banjo Project {2011}

Les Blank: Always For Pleasure

American Epic {2017}

Charley Pride: I’m Just Me {2019}

CDs:

American Epic: The Collection {5 CD box set - 2017}

From Where I Stand: The Black Experience In Country Music {3 CD box - 1998 / 4 CD Box - 2024}

Articles:

Linda Martell {March 1970 / Ebony} Ruby Falls Nisha Jackson {June 14, 1987 / Chicago Tribune} Color Them Country: The Black Women Of Country Music {2019} Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne - x Lesley Riddle {2017} Henry Glover - 1, 2, 3, 4 Sun, Sea and Stetsons: Why St. Lucia loves country and western music {2014} Country Music Is Hugely Popular In Africa. But It’s Nearly All Imported {2017} That Ain't My Song On The Jukebox {1997} Black Hillbilly {2015} Rural Black String Band Music {1980} McDonald Craig {1982} African Bluegrass

Youtube

Shemekia Copeland - Drivin’ Out Of Nashville {2015} Shirley Caesar - No Charge {1983} McDonald Craig - Pistol Packing Papa / Saddie Brown {2010} Donna Summer & Eddie Rabbitt - Medley {1983} Minnie Riperton - It’s So Nice (To See Old Friends) {1974} Nisha Jackson - Alive And Well {1987} A Taste Of Honey - Leavin’ Tomorrow {1982} Miko Marks & The Resurrectors - Whiskey River {2021} The Pointer Sisters - Fairytale / Live Your Life Before You Die {1974 / 1975} Chapel Hart - Country Paradise {2020} Margie Joseph - Touch Your Woman {1975} Rufus & Chaka Khan - I Finally Found You {1973} Patti LaBelle - Country Christmas {1990} Etta Baker & Cora Phillips - Jaybird March {2005} Beyoncé & Dixie Chicks - Daddy Lessons {2016} Sunny Daye - I’m Already There / Sin Wagon {2007 / 2011} Cynthia Mae Talley - Change Of Heart {2010} Frankie Staton - Rhinestone Cowgirl {1999} Toshi Reagon - Mountain Top {2002} Linda Martell - Bad Case Of The Blues {1970} Nell Carter - So Long Dude {1972} Smokey Robinson & Dolly Parton - I Know You By Heart {1987} B. B. King - Alexis’ Boogie {1971} Uncle John Scruggs - Little Log Cabin In The Lane {1928} Sananda Maitreya (Terence Trent D'Arby) - I Still Love You {1993} George W. Johnson - The Laughing Song {1897} Johnnie Taylor - Party Life {1970} Sir Mix-A-Lot - Square Dance Rap / Buttermilk Biscuits {1985 / 1988} Parliament - Little Ole Country Boy {1970} Commodores - Sail On {1979} Michael Jackson - For The Good Times {1984} Stevie Wonder - Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours) {2007} Joe Tex - Grandma Mary {1969} Richie Havens - The Key {2008} Seckond Chaynce - Write This Down {2017} Bad Bascomb - Black Grass {1972} O. B. McClinton - albums / Talk To My Children’s Mama {1977} Big Al Downing - I Ain’t No Fool / Beer Drinkin’ People {1979} Otis Williams And The Midnight Cowboys - Mule Skinner Blues {1971} Whistler’s Jug Band - Foldin’ Bed {1930} Virginia Kirby - Faded Rose {1977} The Nairobi Wranglers - The Legend Of The Black Cowboy & His Music {1980}

#music#country music#bluegrass#folk music#records#country#Black history#1930s#1940s#1950s#1960s#1970s#1980s#1990s#book#Linda Martell#Ruby Falls#Tracy Chapman#Joan Armatrading#Mickey Guyton#Odetta#Beyoncé#The Supremes#Diana Ross#The Pointer Sisters#Millie Jackson#Tina Turner#Charley Pride#Sammy Davis Jr.#Nat King Cole

451 notes

·

View notes

Note

may i ask the definition of country music? i wanna win a debate against my sister….

Country Music is what happens when Folk Music ferments. It has existed in seven distinct generations:

1920-1930, in which people with fiddles sang about farm animals

1930-1950, where cowboys were also invited

1950-1970, in which Nashville took over

1970-1990, in which Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton ruled the Earth

1990-2000, when Trucks and Drinking were valued above all

2000-2020, when you got shot if you didn't mention 9/11

2020-Present, a time of people mostly just wishing Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton still ruled the Earth.

Country Music may also at times involve a "Banjo."

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bob Dylan at a press conference, Mayfair Hotel, London, May 3 1966. Photographed by Tony Gale

my favourite twink

#bob dylan#folk music#folk#music#60s#1960s#photography#history#culture#musicposting#musicians#conference#london#england#1966#vintage photos#1960s music#vintage#1960s vintage#sixites#60s men#swinging 60s#60s music#60s icons#people#blues music#blues rock#rock#ppl#photos

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

People who only wanted to hear a cheerful children's song learning about Joan Petit:

Joan Petit quan balla ("When Joan Petit dances") is a traditional Catalan children's song that lists a series of parts of the body to move in the dance. Here's a video where you can hear it and see how it's danced: people hold hands and move in a circle and sing "when Joan Petit dances, he dances with his..." and add a body part, then repeat the chorus. Each time, the body parts add up on a list that gets longer and longer and the dancers have to remember and dance in order.

Like it happens with other elements of Catalan folk culture, it's shared with our sister nation, Occitania. Occitans also sing it, with the same melody, the same dance, and the same lyrics as the Catalan song but with the lyrics in Occitan language instead of Catalan. However, in Occitania it's more common to remember who the song is talking about, which is mostly unknown in Catalonia.

Joan Petit was an Occitan farmer. In the year 1643, he led the Croquant Rebellion against the king of France Louis XIV's strong taxation of poor people to gather money for war. Joan Petit was captured and tortured on the breaking wheel. The reason why the song lists body parts is in reference to this torture method of smashing all body parts slowly making its way to the head. The story was quickly told all through Occitania and even crossed the Pyrenees, and the memory of Joan Petit and his rebellion still lives on in Occitania. Maybe that's why the Occitan song, by changing only a few notes at the end of the sentences, sounds much sadder than the Catalan version.

One of the most iconic Occitan bands, Nadau, wrote a song explaining Joan Petit's life. Under the cut you can listen to the song and read the English translation of the lyrics.

youtube

Occitan lyrics and English translation:

En país de Vilafranca / Que s'i lhevèn per milièrs / Contra lo gran rèi de França / En mil shèis cents quaranta tres. Mes òc, praubòt, mes òc praubòt / En mil shèis cents quaranta tres. In the place of Vilafranca / they rose up by the thousands / against the great king of France / in 1643. But yes, poor things, but yes, poor things / in 1643.

Entà har guèrra a la talha / Qu'avèn causit tres capdaus, / L'un Laforca, l'aute Lapalha, / Joan Petit qu'èra lo tresau. Mes òc, praubòt, mes òc, praubòt, / Joan Petit qu'èra lo tresau. To wage war on the taxes / they chose three captains: / one of them was Laforca, the other Lapalha / the third one was Joan Petit. But yes, poor thing, but yes, poor thing / the third one was Joan Petit.

Per tota l'Occitania, / Que'us aperavan croquants, / N'avèn per tota causida, / Que la miseria o la sang. Mes òc praubòt, mes òc praubòt / Que la miseria o la sang. In all Occitania / they called them the Croquants / they didn't have any other choice / than either misery or blood. But yes, poor thing, but yes, poor thing / than misery or blood.

E qu'estón per tròp d'ahida / Venuts per los capulats, / Eths que vivèn de trahida, / Çò qui n'a pas jamei cambiat. Mes òc praubòt, mes òc praubòt, / Çò qui n'a pas jamei cambiat. And because they trusted too much / they were sold by the powerful / [the powerful] lived only of betrayal / a thing that has never changed. But yes, poor thing, but yes, poor thing / a thing that has never changed.

Que'us hiquèn dessús l'arròda, / E que'us croishín tots los òs, / D'aqueth temps qu'èra la mòda / De's morir atau, tròç a tròç. Mes òc praubòt, mes òc praubòt, / De's morir atau, tròç a tròç. They put them on the wheel / and they crushed all their bones. / At that time, it was trendy / to die like this, bit by bit. But yes, poor thing, but yes, poor thing / to die like this, bit by bit.

E qu'estó ua triste dança, / Dab la cama, e lo pè, e lo dit, / Atau per lo rei de França, / Atau que dançè Joan Petit. Mes òc praubòt, mes òc praubòt, / Atau que dançè Joan petit. And it was a sad dance / with the leg, the foot, the finger, / and thus, for the king of France, / danced Joan Petit. But yes, poor thing, but yes, poor thing / thus danced Joan Petit.

E l'istuèra qu'a hèit son viatge, / Qu'a pres camins de cançons, / Camin de ronda taus mainatges, / Mes uei que sabem, tu e jo. Mes òc praubòt, mes òc praubòt, / Mes uei que sabem, tu e jo And the history took its journey / it took paths of songs / and tales for children / but today we know, you and I. But yes, poor thing, but yes, poor thing / but today we know, you and I.

#coses de la terra#joan petit#música#arts#nadau#catalan#occitan#occitania#occitanie#folk music#folk songs#traditional song#traditional music#història#history#french history#world music#other countries

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

Song of the Day

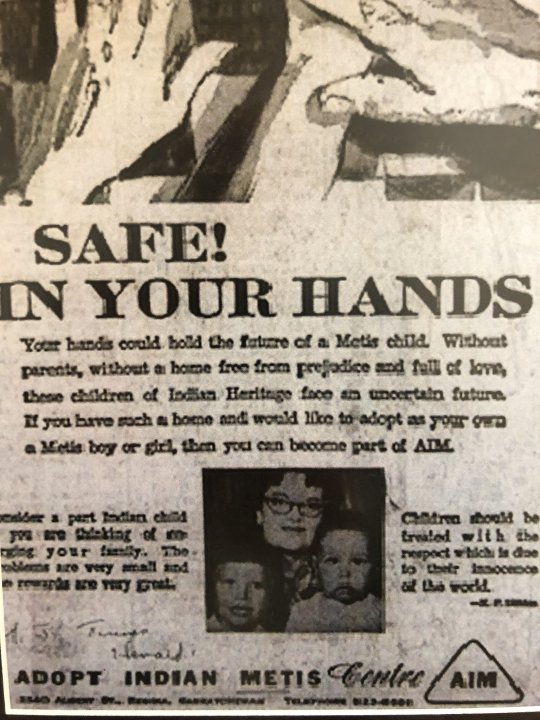

"Call of the moose" Willy Mitchell, 1980 As you might know, September 30th is Truth and Reconciliation day (more commonly known as Orange Shirt Day), a national day in Canada dedicated to spreading awareness about the legacy of Residential schools on Indigenous people. Instead of just focusing on a song, I also wanted to briefly talk about the history of the sixties scoop and its influence on Indigenous American music and activism.

The process of Residential schooling in Canada existed well before the '60s, but the new processes of the sixties scoop began in 1951. It was a process where the provincial government had the power to take Indigenous children from their homes and communities and put them into the child welfare system. Despite the closing of residential schools, more and more children were being taken away from their families and adopted into middle-class white ones.

Even though Indigenous communities only made up a tiny portion of the total population, 40-70% of the children in these programs would be Aboriginal. In total, 20,000 children would be victims of these policies through the 60s and 70s.

These adoptions would have disastrous effects on their victims. Not only were sexual and physical abuse common problems but the victims were forcibly stripped of their culture and taught to hate themselves. The community panel report on the sixties scoop writes:

"The homes in which our children are placed ranged from those of caring, well-intentioned individuals, to places of slave labour and physical, emotional and sexual abuse. The violent effects of the most negative of these homes are tragic for its victims. Even the best of these homes are not healthy places for our children. Anglo-Canadian foster parents are not culturally equipped to create an environment in which a positive Aboriginal self-image can develop. In many cases, our children are taught to demean those things about themselves that are Aboriginal. Meanwhile, they are expected to emulate normal child development by imitating the role model behavior of their Anglo-Canadian foster or adoptive parents."

and to this day indigenous children in Canada are still disproportionately represented in foster care. Despite being 5% of the Total Canadian population, Indigenous children make up 53.8% of all children in foster care.

I would like to say that the one good thing that came out of this gruesome and horrible practice of state-sponsored child relocation was that there was a birth of culture from protest music, but there wasn't. In fact, Indigenous music has a long history of being erased and whitewashed from folk history.

From Buffy Saint-Marie pretending to be Indigenous to the systematic denial of first nations people from the Canadian mainstream music scene, the talented artists of the time were forcibly erased.

Which is why this album featuring Willy Mitchell is so important.

Willy Mitchell and The Desert River Band

This Album was compiled of incredibly rare, unheard folk and rock music of North American indigenous music in the 60s-80s. It is truly, a of a kind historical artifact and a testimony to the importance of archival work to combat cultural genocide. Please give the entire thing a listen if you have time. Call of the Moose is my favorite song on the album, written and performed by Willy Mitchell in the 80s. His Most interesting song might be 'Big Policeman' though, written about his experience of getting shot in the head by the police. He talks about it here:

"He comes there and as soon as I took off running, he had my two friends right there — he could have taken them. They stopped right there on the sidewalk. They watched him shootin’ at me. He missed me twice, and when I got to the tree line, he was on the edge of the road, at the snow bank. That’s where he fell, and the gun went off. But that was it — he took the gun out. He should never have taken that gun out. I spoke to many policemen. And judges, too. I spoke with lawyers about that. They all agreed. He wasn’t supposed to touch that gun. So why did I only get five hundred dollars for that? "

These problems talked about here, forced displacement, cultural assimilation, police violence, child exploitation, and erasure of these crimes, still exist in Canada. And so long as they still exist, it is imperative to keep talking about them. Never let the settler colonial government have peace; never let anyone be comfortable not remembering the depth of exploitation.

Every Child Matters

#orange shirt day#truth and reconciliation#first nations#song of the day#indigenous folk#canadian history#sixties scoop#indigenous music#folk#folk revival#folk music#folk rock#60s#willy mitchell#song history#60s country#80s music#protest folk#music history#residential schools#american folk#american folk revival#Spotify

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

The story of the first Led Zeppelin concert recording

Led zeppelin is a diamond of Rock music- the purest water

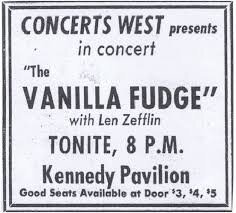

The first ("known to science") Led Zeppelin concert recording appeared back in the period when not everyone could even immediately remember their name, and the team's debut record has not yet been released. On December 30, 1968, Led Zeppelin opened for the Americans from New York, Vanilla Fudge, who were at the peak of their popularity that year.

The venue was Gonzaga University in the American city of Spokane (Washington State), it is, remarkably, considered Catholic, and named after a saint named Aloysius Gonzaga of the Jesuit Order, the patron saint of youth and students. If they only knew what Led Zeppelin's lyrics might be about! A concert was held in one of the buildings on campus, to be precise, in the John F. Kennedy Pavilion (built in 1965). By the way, it was cold sub-zero weather outside.

This is what John F. looks like. The Kennedy Pavilion is equipped.

And so inside in 1965.

The cheapest concert ticket cost three dollars (now, and the most expensive - five

The setlist of the performance was as follows:

"Train Kept A Rollin'"

"I Can't Quit You"

"As Long As I Have You"

"Dazed And Confused"

"White Summer"

"How Many More Times"

"Pat's Delight"

As you can see, of the seven tracks, only three will be released on the debut album in just two weeks. Such a number of "non-album" tracks speaks to the level of musicians who enjoyed live performances rather than playing a standard set of songs.

The concert was recorded by the simplest amateur method on a cassette, so the recording quality is far from ideal, and sometimes you can even hear a hell of a mess.

youtube

A very funny story is also connected with this concert - Led Zeppelin was named Len Zefflin in an advertisement. One can only guess why the band's name has been distorted so much.

That's how you imagine American students waking up with a hangover and asking,

"Well, how was Len Zefflin yesterday?"

#Youtube#Led Zeppelin#robert plant#jimmy page#john bonham#blues rock#folk music#heavy metal#john paul jones#the yardbirds#music#my music#music love#musica#history music#rock music#rock#rock photography

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black people#black community#black art#original photographers#black culture#artwork#graphic design#black family#black power#black history#black woman#black panther#black music#black kids#black folks#black man#black#black turtle in#black tumblr

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music of TURN

Round 28

The Turtle Dove

4.03: Blood for Blood

youtube

Jock O'Hazeldean

1.08: Challenge

youtube

#turn music bracket#turn: washington's spies#turn amc#turn washingtons spies#the turtle dove#jock o'hazeldean#18th century music#music history#folk music history#folk music

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

in the first half of the 20th century (and probably before, but that's when this music started being recorded in audio) there were quite different "rules" around switching pronouns when playing songs originally from the perspective of another gender. it was not inherently queer to sing songs from a cross-gender perspective, but it might have given people a way to express themselves or to feel seen

i yap about this a lot but finally made some playlists

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth Cotten playing banjo for a segment in a TV series. (1985)

Song is called Georgie Buck, which is an old traditional folk tune. She was around 92 years old when this was recorded.

Source: Aly Bain's Down Home

#Music#Music history#Elizabeth Cotten#Elisabeth cotten#Blues#Old blues#Blues history#banjo player#Banjo#History#Blues players#Folk songs#Traditional folk songs

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

cork mountain games // aldeias do xisto, portugal // february 2024 // ©

#my photos#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#photography#travel#photooftheday#europe#portugal#entrudo#carnaval#lousa#aldeias do xisto#mountains#folk music#mascaras#masks#midwinter#folk festival#folk art#culture#history#portuguese culture#effigy#the spirits of winter#spring festival#possibly one of the best festivals i have ever been to

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know it's Gordon Lightfoot's time right now, but I want to shine a light on another bard of the Great Lakes: Lee Murdock.

youtube

He does a fantastic version of 'Red Iron Ore' followed by a cover of 'The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald'. (Also on Spotify).

#lee murdock#great lakes#music#maritime history#the wreck of the edmund fitzgerald#red iron ore#folk music#lee murdock is so underrated#and i'm not just saying that because he made a war of 1812-themed album

23 notes

·

View notes