#florida adoption home study

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Luxury Modern Kitchen Design: A Blend of Functionality and Elegance

Creating a luxury modern kitchen design is an exciting journey that combines cutting-edge aesthetics with high functionality. Modern kitchens are more than cooking spaces; they’re central hubs of the home, reflecting personal style and taste. Whether you’re in a bustling urban apartment or a sprawling suburban house, a well-designed luxury kitchen can elevate your daily experience.

The materials used in a luxury modern kitchen design set the tone for its overall aesthetic and durability.

A luxury kitchen is an investment in both style and functionality. Whether you’re entertaining guests or enjoying a quiet evening, the right design will ensure the kitchen remains the heart of your home.

#florida adoption home study#affordable adoption home study#adoption home study#large luxury kitchen design

0 notes

Text

Good News - August 15-21

Like these weekly compilations? Tip me at $kaybarr1735 or check out my new(ly repurposed) Patreon!

1. Smart hives and dancing robot bees could boost sustainable beekeeping

“[Researchers] developed a digital comb—a thin circuit board equipped with various sensors around which bees build their combs. Several of these in each hive can then transmit data to researchers, providing real-time monitoring. [… Digital comb] can [also] be activated to heat up certain parts of a beehive […] to keep the bees warm during the winter[…. N]ot only have [honeybee] colonies reacted positively, but swarm intelligence responds to the temperature changes by reducing the bees' own heat production, helping them save energy.”

2. Babirusa pigs born at London Zoo for first time

“Thanks to their gnarly tusks […] and hairless bodies, the pigs are often called "rat pigs" or "demon pigs” in their native Indonesia[….] “[The piglets] are already looking really strong and have so much energy - scampering around their home and chasing each other - it’s a joy to watch. They’re quite easy to tell apart thanks to their individual hair styles - one has a head of fuzzy red hair, while its sibling has a tuft of dark brown hair.””

3. 6,000 sheep will soon be grazing on 10,000 acres of Texas solar fields

“The animals are more efficient than lawn mowers, since they can get into the nooks and crannies under panel arrays[….] Mowing is also more likely to kick up rocks or other debris, damaging panels that then must be repaired, adding to costs. Agrivoltaics projects involving sheep have been shown to improve the quality of the soil, since their manure is a natural fertilizer. […] Using sheep instead of mowers also cuts down on fossil fuel use, while allowing native plants to mature and bloom.”

4. Florida is building the world's largest environmental restoration project

“Florida is embarking on an ambitious ecological restoration project in the Everglades: building a reservoir large enough to secure the state's water supply. […] As well as protecting the drinking water of South Floridians, the reservoir is also intended to dramatically reduce the algae-causing discharges that have previously shut down beaches and caused mass fish die-offs.”

5. The Right to Repair Movement Continues to Accelerate

“Consumers can now demand that manufacturers repair products [including mobile phones….] The liability period for product defects is extended by 12 months after repair, incentivising repairs over replacements. [… M]anufacturers may need to redesign products for easier disassembly, repair, and durability. This could include adopting modular designs, standardizing parts, and developing diagnostic tools for assessing the health of a particular product. In the long run, this could ultimately bring down both manufacturing and repair costs.”

6. Federal Judge Rules Trans Teen Can Play Soccer Just In Time For Her To Attend First Practice

“Today, standing in front of a courtroom, attorneys for Parker Tirrell and Iris Turmelle, two transgender girls, won an emergency temporary restraining order allowing Tirrell to continue playing soccer with her friends. […] Tirrell joined her soccer team last year and received full support from her teammates, who, according to the filing, are her biggest source of emotional support and acceptance.”

7. Pilot study uses recycled glass to grow plants for salsa ingredients

“"We're trying to reduce landfill waste at the same time as growing edible vegetables," says Andrea Quezada, a chemistry graduate student[….] Early results suggest that the plants grown in recyclable glass have faster growth rates and retain more water compared to those grown in 100% traditional soil. [… T]he pots that included any amount of recyclable glass [also] didn't have any fungal growth.”

8. Feds announce funding push for ropeless fishing gear that spares rare whales

“Federal fishing managers are promoting the use of ropeless gear in the lobster and crab fishing industries because of the plight of North Atlantic right whales. […] Lobster fishing is typically performed with traps on the ocean bottom that are connected to the surface via a vertical line. In ropeless fishing methods, fishermen use systems such an inflatable lift bag that brings the trap to the surface.”

9. Solar farms can benefit nature and boost biodiversity. Here’s how

“[… M]anaging solar farms as wildflower meadows can benefit bumblebee foraging and nesting, while larger solar farms can increase pollinator densities in surrounding landscapes[….] Solar farms have been found to boost the diversity and abundance of certain plants, invertebrates and birds, compared to that on farmland, if solar panels are integrated with vegetation, even in urban areas.”

10. National Wildlife Federation Forms Tribal Advisory Council to Guide Conservation Initiatives, Partnerships

“The council will provide expertise and consultation related to respecting Indigenous Knowledges; wildlife and natural resources; Indian law and policy; Free, Prior and Informed Consent[… as well as] help ensure the Federation’s actions honor and respect the experiences and sovereignty of Indigenous partners.”

August 8-14 news here | (all credit for images and written material can be found at the source linked; I don’t claim credit for anything but curating.)

#hopepunk#good news#honeybee#bees#technology#beekeeping#piglet#london#zoo#sheep#solar panels#solar energy#solar power#solar#florida#everglades#water#right to repair#planned obsolescence#trans rights#trans#soccer#football#recycling#plants#gardening#fishing#whales#indigenous#wildlife

135 notes

·

View notes

Note

what’s the girls relationship like with uncle (grandpa?) wayne?

yesss we love Grandpa Wayne 🥹

Wayne was actually the first person to know about Moe (and the only person, for a little while, because privacy is a big deal w/foster kids and the Party is notably god-awful at keeping things on the DL so Steve and Eddie didn’t loop everyone in until the adoption was complete).

Wayne was the first one to meet Moe, the first to hold her. Wayne proudly wrote the reference letter they’d needed as part of their home study to adopt her.

Wayne came up to Massachusetts from Indiana to take care of Moe while Steve and Eddie were in the NICU with Robbie.

Wayne was Eddie’s first call when Hazel was born.

When the girls are very little (toddlers/early elementary school) he’s still living in Indiana (he's in a silent feud with Hopper over who can stand to stay in Hawkins the longest). The feud only comes to an end because, when Steve’s dad passes in 2009, Eddie gets freaked out and basically insists that Wayne move closer to them.

Wayne isn’t even all that bummed about losing to Hop because it means he gets to spend more time with the grandkids. He absolutely rubs this in at any opportunity, and Hopper and Joyce make the move up north only a year or two later (Hop claims it was unrelated).

The girls adore him. He’s steady and reliable and always down for a good card game (he teaches them how to play poker just a little bit too young) and he shows up to every play and recital and all the important sports games, and he can roast their dad like nobody's business.

He has a particularly special bond with Hazel, who, like him, loves nature and being outside. They go birdwatching and fishing together (catch and release, obviously, because Hazel wouldn’t stand for anything else) and take day trips to nearby national parks and botanical gardens.

Hazel goes to Florida for college, pursuing a degree in zoology at one of the best programs in the country, and they joke that Wayne should be awarded an honorary BS with how much of her coursework Hazel relays to him (she calls him after practically every lecture). Eddie has to fight tooth and nail to keep him from moving back down to Florida to join her there.

#eddie takes actual offense to the florida thing#that only makes sense if you’ve read the series tho oop#i did write Wayne’s adoption reference letter but not sure if/when that would ever see the light of day#steddie#liv’s steddie dads verse#steddie dads#steve harrington#eddie munson#wayne munson

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

20k Words Masterlist

Act Naturally (ao3) - jestbee

Summary: Phil has a quiet life studying film at university and some small dreams of being a director he’s mostly ignoring, but his whole life is turned upside down when his roommate signs him up for a game show and he meets the famously arrogant movie star Daniel Howell

all signs point to yes (ao3) - vvelna

Summary: After being fired from his job at a coffee shop in Gatwick Airport, Dan impulsively hops on a flight to Orlando, Florida, where he’s taken in by a family on holiday.

All We Seem to Do Is Talk About Sex (ao3) - truerequitedlove

Summary: In which Dan’s got a boyfriend and a tongue piercing, and Phil’s got a weed hookup and an anxiety disorder. In high school, they were labeled “bad influences on each other,” maybe that would never go away.

because we are fools (ao3) - queerofcups

He realizes it calmly at first, and then suddenly with more clarity. He’s in love with Phil. But he absolutely cannot be in love with Phil.

Breathe Fire Into My Heart (ao3) - Finally_Facing_Failure

Summary: Dan Howell lives in a world were dragons fly the skies, with riders on their backs. He has to train to become a rider, even though he doesn’t want to. The upside? A boy named Phil who trains beside him.

Chance (ao3) - cafephan

Summary: Phil Lester is a nobleman in the country of Bennia, and his family must put forward a suitor for the Princess’ hand in marriage later in the month. During his last night in Manchester, he encounters charismatic Dan Howell, resulting in them both taking a chance.

Devotion (ao3) - roryonice

Summary: Dan is a ballerina who’s practicing for an audition at Julliard, but he’s afraid of performing in front of other people. He meets Phil, who’s gathering photos for his art portfolio, and Phil helps Dan come out of his shell in an interesting way.

Do You Know How in Love With You I Am (Please Notice) (ao3) - phantasticworks

Summary: Dan works at a small paper company, but the brightside to this boring career is that his best friend Phil is just a few feet away at reception. The downside to this is that he’s hopelessly, irrevocably in love with said best friend. Oh, and Phil is engaged, too.

Feel Good Inc. - melancholymango

Summary: Dan is your local sexually ambiguous religious boy. Phil is your local bad boy that sleeps with anyone that’ll have him and sins as if second nature. Then there’s also the poor original character that gets caught between them and their ridiculous amount of sexual tension. Threesomes, eh?

from up here you can’t beat the view (just watch me now) (ao3) - kishere, maybeformepersonally

Summary: It’s 2009 and Dan finds Phil on the internet when a well-meaning mate of his recommends him to a certain site she likes. Dan quickly becomes a fan: watching Phil’s videos religiously and interacting with him on his socials. And, soon enough, Phil starts noticing him. A familiar enough story on the surface but here’s the catch: Phil has never been involved with YouTube. Phil is a camboy.

I Choose You (ao3) - Phandiction

Summary: Phil’s parents have decided to adopt and Phil’s thrilled to finally have a brother. When he meets Dan they hit it off but little did he know his parents had decided to bring home a little girl instead. Phil spends the next nine years visiting Dan at the orphanage. One day Dan unexpectedly goes outside the lines of friendship and Phil isn’t sure if he’s ready for that.

i feel a kick down in my soul (ao3) - chickenfree

Summary: “I’m going to obliterate you,” he says, taking a few long steps towards Phil.

Phil runs. It takes him a minute to realize the ball is in the opposite direction.

I Found (ao3) - wildflowerhowell

Summary: Dan Howell and Phil Lester hate each other, and everyone at the Ida Gatley school of dance knows it. So what happens when the two are paired together to choreograph and perform a duet at England’s most renowned contemporary dance competition?

I’m A Stitch Away From Making It (And A Scar Away From Falling Apart) - waverlysangels

Summary: Dan Howell is ‘the next big thing’ and Phil Lester is not good for publicity, will the increasing fame create tensions that simply cannot be overcome?

i will follow where this takes me (ao3) - curiosityandrain

Summary: Dan has a great life, he has an amazing job as a photographer and he lives in New York. Phil is an independent filmmaker who hires Dan to be his cinematographer for his upcoming feature film after his usual cinematographer was involved in an accident. The two hit it off and become instant friends. Weeks of working together everyday helps develop their friendship and slowly but surely, Dan realises his feelings for Phil run deeper than just friendship. The only problem is, Phil’s taken.

knight of wands (ao3) - dizzy

Summary: Some days are just boring.

(And some aren't.)

Love That Passes (Is Enough) (ao3) - nihilist_toothpaste

Summary: Phil is a sad divorcee who lives in a mansion. Dan starts as a nervous and weirdly loud law student hired to work part-time as Phil's poolboy-slash-housekeeper and turns into so much more.

Just go with me on this.

More at Eleven (ao3) - TwistedRocketPower

Summary: Phil Lester, the most beloved meteorologist at Southeast News, isn't sure of many things in his life. One thing he is sure of, however, is that he absolutely hates the new entertainment news anchor, Dan Howell.

No Angels (ao3) - ahsuga, danthrusts

Summary: Dan and Phil are detectives investigating the ongoing murders of citizens throughout London

Project Poliwag (ao3) - natigail

Summary: Phil hadn't intended for his garden to become a haven for rescued Pokémon, but it had happened accidentally. This particular rescue wasn't that different, even though he had never rescued 117 Pokémon at once before. But he couldn't leave the Pokémon eggs to be destroyed, and he was willing to raise a whole army of Poliwag on his own if he must.

What Phil hadn't counted on was a stranger with a lost look in his eye turning up on his doorstep and offering to help with the project.

Something So Strong (ao3) - Allthephils

Summary: Dan and Phil were the best of friends with some incredible benefits. Over a decade apart did nothing to weaken the bond between them but rekindling their friendship isn’t as simple as it should be.

The Parent Trap (ao3) - starsatellite

Summary: Alexandra Lester and Charlotte Howell are in for a big surprise at their summer camp when they realize they have the same face. After, literally, putting the pieces together they find out the big secret their parents hid from them when they were born. Now, all they want is to set them back up again - but these things aren’t always so easy.

(There’s Gotta Be) More To Life (ao3) - DisasterSoundtrack

Summary: Dan Howell finally gets a dog he dreamt of. Walking the dog every morning, he discovers many things about his neighbourhood, but, above all, one particularly attractive dad.

Unraveling - yuurisnice

Summary: Dan knew he was different from other children very early on. He never lost his ‘imaginary friends’, they only became a more integral part of his life. Living with his illness is never easy and with a secret as large as his, cracks are bound to appear. While he isn’t ashamed of his DID, he knows the consequences of telling the wrong people.

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

This Tumblr Ask is mostly an excuse to interact with another human. I hope you don’t mind.

Would you say Mormonism has a better history of changing entrenched stances than other religions?

Of the religions which don’t currently perform same sex marriages, which do you think will start in the next 100 years?

Who would you guess is going to be the central orbit in your afterlife: you or your husband?

Over the past 20 years, Salt Lake City Utah has had some of the best numbers regarding changes in racial diversity and home prices in the nation. A generation ago this relationship (then known as “White Flight”) was a major and very sad problem many municipalities faced. Is Mormonism in Florida making lives better for Black people?

These are interesting questions.

—————————

Would you say Mormonism has a better history of changing entrenched stances than other religions?

Mormonism believes in on-going revelation, and its top leader is considered to be a prophet and we also have apostles. In other words, the structure is one which suggests change is an ongoing feature of this church. Compared to where the LDS Church was in 1830 or even 1960, much has changed.

Despite this, it seems to me to be slower than others when it comes to reconsidering "entrenched stances." It didn't allow full participation by Black members until 1978. Every few years it seems to take another small step or two towards equality for women, but the slow pace of change makes it feel like it's falling further behind much of Christendom.

I think the reason for this church being slow to progress forward is that it raises questions about the role of the prophet and apostles. If the past leaders were wrong about race or the inclusion of women, what might the current leaders be wrong about? Undermining the authority & teachings of past leaders calls into question the authority & teachings of the current leaders. Can I disregard what they're saying on LGBTQ+ topics because I believe there'll be further revelation and change, even if the current leaders say that the current teachings won't change, just like the past leaders said there wouldn't be change?

The current workaround is that doctrine doesn't change, but policies do. While I know many consider the LDS Church's teachings on gender and marriage to be doctrine, they have changed many times and therefore I think of them as policies.

—————————

Of the religions which don’t currently perform same sex marriages, which do you think will start in the next 100 years?

One of the ways churches create an identity for themselves is by what they stand for. They also can define themselves by what they are against. Unfortunately, for hundreds of years Christianity has adopted being anti-gay/anti-queer as part of the definition of what it means to be Christian. Changing this identity is difficult.

There are Christian denominations wrestling with accepting same-sex marriages. Changing their stance has roiled their denominations. While many are thrilled, some traditionalists are alarmed & dismayed and whole congregations vote to leave that particular denomination.

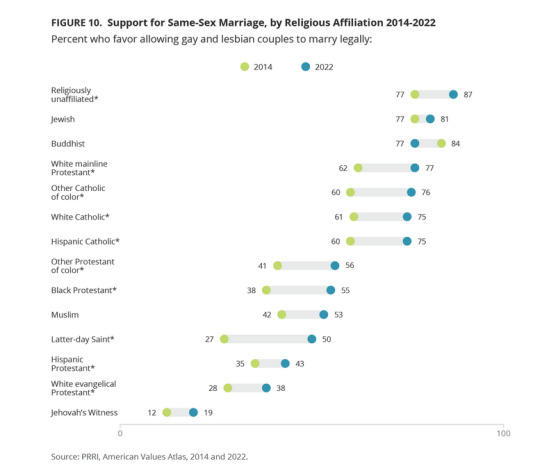

I think this study showing the changing acceptance of gay marriage by religions in the United States is fascinating. I think it predicts most religions in the United States will ultimately accept queer people and same-sex marriages.

This chart shows that the Latter-day Saints moved the most in the past 8 years, from 27% to 50%. This is very much related to LGBTQ+ members coming out, especially teenagers and those in their 20's. Also, we have had a wave of adults who came out & left their mixed-orientation marriages. It's been a big, messy process, but now it seems most everyone knows or is related to a Mormon/ex-Mormon who is out as LGBTQ+. Which underlines that when people actually know queer folks and hear our stories, it changes hearts.

—————————

Who would you guess is going to be the central orbit in your afterlife: you or your husband?

Gosh, I don't know how to answer this. I'm not sure what this means to be the "central orbit" of my afterlife.

Considering I'm single and don't have a husband, I will have to say that it won't be my husband. Although, if I'm lucky, maybe one day my marriage status will change

—————————

Over the past 20 years, Salt Lake City Utah has had some of the best numbers regarding changes in racial diversity and home prices in the nation. A generation ago this relationship (then known as “White Flight”) was a major and very sad problem many municipalities faced. Is Mormonism in Florida making lives better for Black people?

It's interesting you speak of Salt Lake City as racially diverse. When I visit, I notice the lack of such diversity. I suppose compared to where it was, it is becoming more diverse, but so is the United States.

Utah is the 34th most racially and ethnically diverse state in the nation, putting it in the bottom half of states. Forty percent of the state’s growth since 2010 has come from racial and ethnic minority populations, who are expected to account for one in three Utahns by 2060. In contrast, it is projected by 2040 that the United States is expected to have no race or ethnic demographic which is more than 50% of the population, making us a majority minority nation.

So yes, Salt Lake City and Utah are becoming more diverse, but still lags far behind the United States as a whole.

As for your question whether Mormonism in Florida is making lives better for Black people, I don't think so. I also wouldn't say we're making life worse.

I know we have talked about being more welcoming of Black people and have had some committees in my local area to discuss what changes we can make in our congregations or what contribution we can make to the Black community in the area. I'm not aware of any sustained efforts to make changes or to partner with local organizations.

Our congregations in Florida may look more diverse than the average congregation in Utah, but typically they're not as diverse as the neighborhoods where we are located. We have much room for improvement in making a space where all feel welcome and that this is their spiritual home.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Leor Sapir

Published: Jun 28, 2023

A growing number of countries, including some of the most progressive in Europe, are rejecting the U.S. “gender-affirming” model of care for transgender-identified youth. These countries have adopted a far more restrictive and cautious approach, one that prioritizes psychotherapy and reserves hormonal interventions for extreme cases.

In stark contrast to groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which urges clinicians to “affirm” their patient’s identity irrespective of circumstance and regards alternatives to an affirm-early/affirm-only approach “conversion therapy,” European health authorities are recommending exploratory therapy to discern why teens are rejecting their bodies and whether less invasive treatments may help.

If implemented in American clinics, the European approach would effectively deny puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to most adolescents who are receiving these drugs today. Unlike in the U.S., in Europe surgeries are generally off the table before adulthood.

Why are more countries turning their backs on what American medical associations, most Democrats and the American Civil Liberties Union call “medically necessary” and “life-saving” care? The answer is that Europeans are following principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM), while Americans are not.

A bedrock principle of EBM is that medical recommendations should be grounded in the best available research. EBM recognizes a hierarchy of information. The expert opinion of doctors, for example, even when based on extensive clinical experience, furnishes the lowest quality — meaning, least reliable — information. Slightly higher on the information pyramid are observational studies. Systematic reviews of evidence, meanwhile, furnish the highest quality evidence. They follow a rigorously developed, reproducible methodology. They do not cherry-pick studies with convenient results, but instead consider all the available research.

Most importantly, systematic reviews don’t merely summarize the conclusions of available studies on a question of interest. Instead, they assess the strengths and weaknesses of these studies to determine the reliability of their findings. To do this, systematic reviews typically use the GRADE system (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) and rank the quality of evidence as “high,” “moderate,” “low” or “very low.”

Systematic reviews by EBM experts in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom have concluded that there are serious gaps in the evidence base for sex modification in minors. The U.K. systematic reviews found the available research to be of “very low” quality — meaning that there is very low certainty that an observed effect, like reduced suicidality, is due to the intervention, and therefore the studies’ claimed results are unlikely to represent the truth.

Importantly, even the famous Dutch study that is said to be the “gold standard” of research in this area received a rating of “very low” due to serious methodological problems. Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare has said that the risks of treating gender dysphoric minors with hormonal interventions “currently outweigh the possible benefits.”

Last year, Florida’s health authorities commissioned what is known as an “umbrella review,” or a systematic overview of systematic reviews, from independent experts at McMaster University, home of EBM. Unsurprisingly, that overview came to the same conclusion: There is no reliable evidence that youth transition improves mental health outcomes.

Because U.S. medical groups don’t always use EBM, their conclusions can be based on studies whose fatal flaws are overlooked or ignored. Consider, as an example, a study done at Seattle Children’s Hospital and published last year. The study’s authors reported that use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones was associated with 60 percent lower odds of depression and 73 percent lower odds of suicidality. Leading mainstream publications, including Scientific American and Psychology Today, celebrated the findings. More recently, major U.S. medical associations cited the study in federal court proceedings.

But a careful look at the study’s data shows that the kids who received hormonal interventions did no better by the end of the study than at the beginning. The researchers’ claim about improvement was based on the fact that the kids in the control group, who received psychotherapy but not hormones, got worse relative to the hormone group. But even this isn’t accurate, as 80 percent of the control group dropped out by the end of the study, and a likely reason for this dramatic loss to follow-up is that many or perhaps all of the non-hormone-treated kids improved without “gender-affirming” drugs. It’s quite possible that if the researchers had followed up with all the participants, we’d see this study become Exhibit A in the case against pediatric sex changes.

Similar problems exist in studies purporting to show a rate of transition regret of less than 1 percent. The true rate of regret is not known and won’t be known for years to come. The claim that gender dysphoric teens are at high risk of suicide if not given access to “gender-affirming” drugs and surgeries is likewise baseless and irresponsible. In February, Finland’s top expert in gender medicine emphasized this point to the country’s liberal newspaper of record.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ main statement on gender medicine, authored by a single doctor while still in his residency, is not a systematic review. The author himself has conceded as much. A later published peer-reviewed fact check found the AAP statement to be a textbook example of cherry-picking and mischaracterization of evidence.

The World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) says in its latest “standards of care” that a systematic review of evidence is “not possible.” Instead, WPATH used a “narrative review,” which has a high risk of bias according to EBM because it doesn’t utilize a reproducible methodology. England has broken from WPATH, and the director of Belgium’s Center for Evidence-Based Medicine has said he would “toss them [WPATH’s guidelines] in the bin.” In the U.S., WPATH’s standards are widely accepted as authoritative.

The U.S. Endocrine Society has relied on two systematic reviews in developing its own guideline. But these reviews were not for mental health benefits, and in any case the Endocrine Society ranks the quality of evidence behind its own recommendations as “low” or “very low.”

All other U.S. medical groups cite these three sources when assuring the public about “gender-affirming care,” thus creating an illusion of consensus around “settled science.”

Earlier this year, an investigative report in the prestigious British Medical Journal concluded that although pediatric gender medicine in the U.S. is “consensus-based,” it is not “evidence-based.” Gordon Guyatt, distinguished professor in the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact at McMaster University, Ontario, and one of the founders of EBM, recently called American guidelines for managing youth gender dysphoria “untrustworthy.”

Consensus can be produced by misguided empathy, ideological capture or political pressures. Consensus can also be manufactured. The new president of the American Medical Association (AMA) has said there should be “no debate” when it comes to offering kids “gender-affirming” drugs and surgeries.

Yale School of Medicine’s Dr. Meredithe McNamara calls the questioning of the evidence behind pediatric sex changes “science denialism.” Her protest is ironic. Science is a process of ongoing inquiry and debate, not a set of predetermined conclusions. Science depends on skepticism, especially about sensitive subjects. True science denialism means restricting rational, evidence-based debate — exactly what McNamara and the AMA’s new president want to do.

Their calls are bearing fruit. Just this month, gender activists successfully pressured a medical journal to retract a paper whose conclusions they found inconvenient. The ongoing campaign to suppress scientific debate allows a pseudo-consensus to emerge around “gender-affirming care.”

Put simply, pediatric gender medicine in the U.S. is out of control. Medicalization of gender diversity in children is a fast-growing industry that shows no signs of self-correction. Doctors and therapists who practice “affirmative” medicine consistently demonstrate ignorance about EBM principles and deceive the public about the grim realities behind the euphemism “gender-affirming care.”

A Reuters investigation last year interviewed providers at 18 pediatric gender clinics and found that none were doing comprehensive mental health assessments and differential diagnosis. Those who promote and practice “gender-affirming care” themselves tell us that their approach is child-led. “Gatekeeping” of medical transition, they insist, is pointless, even “dehumanizing.”

The author of the AAP’s position paper on gender medicine has said that a “child’s sense of reality” is the “navigational beacon to orient treatment around.” The director of the gender clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital has admitted that they give out puberty blockers “like candy.” Even the founding psychologist of that clinic has warned that kids are being inappropriately “rushed toward the medical model.”

Why the U.S. has become an outlier on pediatric transgender medicine is a complicated question, but at least part of the answer is that European welfare states have centralized health bureaucracies and public health insurance. Before medicines can be approved for state funding, their evidence base needs to be evaluated. The American health care system is more vulnerable to profit motives, activist doctors and political pressures. Medical associations claim to advocate for patient health but can have other motives as well.

The situation is so dire that when pediatric gender medicine experts in other countries want to defend their practices before a skeptical public, they sometimes say that at least they are not as bad as the Americans. That is one kind of American exceptionalism we can do without.

==

[A] “child’s sense of reality” is the “navigational beacon to orient treatment around.”

Holy shit.

How can you claim that it's "settled science" and "consensus," and then leave everything up to the most immature, most depressed, most anxious, least experienced person in the room?

There are no grown ups in charge.

#Leor Sapir#gender ideology#genderwang#queer theory#medical corruption#medical scandal#gender affirming#sex trait modification#gender affirming care#affirmation model#affirmation#weak evidence#poor evidence#evidence based medicine#settled science#religion is a mental illness

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

A town called Prose is home to || Cailan Williams || who is a || thirty one || year old, || cis man ||. They work as || veterinarian || and live in || Drew Drive||. in Prose, they’re known as the || Sean Teale || lookalike. || he/him || They were confused and startled by the recent news.

tw death, tw accident

Cailan known as Cal was born and raised in Florida. Having a love for the beach, the sun and spending so much of his life outdoors. Growing up, he was always a confident and outgoing young man. He knew what he wanted out of life. He was talkative, adventurous, and could never sit still for long. He has a good sense of humour and enjoys making others laugh. From a young age, he was always climbing things, playing baseball and other sports, teaching himself instruments and building things with his own hands. He liked to be on the go, and he liked to be busy and that has never really changed into his adult life.

As a child like many others at that age, Cailan thought he was invincible. Throughout elementary school, he liked to push boundaries and he was often getting himself in trouble, even when he didn't mean to. Though overall, he was a kindhearted and empathetic child despite his playful and reckless ways. He had plenty of friends and showed he was a loyal and good young person. Cailan is also very smart and excelled when it came to his school work, with a real strength for maths and science. His parents knew he needed to be kept busy during his childhood and gave him plenty of opportunities, whether that be sports, drama club and even going on hiking trails.

His parents loved him, despite the many times they were called into school for him pulling a prank or telling a teacher they had the wrong answer. He was close to his dad, and enjoyed working on cars with him and playing sports together. He also learned to cook with his mom and grandmother.

Though his life took a turn for the worst at just fifteen years old when a tragic accident happened. Cailan and his friend went climbing without safety gear and got into some trouble at the top of the cliff. When the rock crumbled, the boys fell. Cailan managed to hold on, but his best friend fell and all Cailan could do was watch. That memory has stayed with him into his adult life and Cailan still feels guilty, blaming himself for what happened.

For a while, Cailan let his rebellious side take over, messing about and getting himself into trouble throughout high school. The loss of his best friend had hit him hard and the young man acting out. Though in his last year of high school, finding a hurt dog out on a run knocked some sense into him and ended up showing Cailan where he wanted his life to be. He took the dog home, made sure he got medical help and looked after him. Eventually adopting the dog as his own. He knew from that moment, he wanted to be a vet, he had always loved science and had empathy for those around him. And he began working hard in school again and securing a place at Cornell University for veterinary science when he was eighteen.

Throughout the rest of high school he became closer to his family and they managed to keep him on track. He made a new group of friends and had a teenage girlfriend. He was a regular teen, despite the moments alone where the loss of his friend still hurt him more than he would ever admit to anyone. He enjoyed moving away for college. He liked the independence and meeting new people. Despite the partying and the messing about, he excelled and put everything into his studies.

Cailan works hard and he gives life his all. He's a jokester and friendly to everyone he meets though he's never really let anyone too close. He’s afraid of losing people, afraid of them seeing his vulnerabilities. The job in Prose was not one he was looking for, but everything seemed to fall into place. When the small town in New Hampshire was looking for a replacement for the retiring old owner, it felt like the perfect opportunity and it soon felt like home. He liked the small community and he enjoyed people's animals who he saw regularly.

He is now thirty one and a pretty good veterinary doctor. He has worked in the small town hospital for a couple of years now. He’s in a settled place and is genuinely happy with where his life is at. He knows he is an attractive man, he likes to flirt, he likes to make people laugh but he keeps himself out of trouble most of the time. He enjoys going out on his bike, he goes camping with his friends quite often and he likes to keep fit. He still likes to be on the go, always running, boxing and messing around with a football. Though he has his quiet moments just watching a sad movie when no one is around. He’s a dog lover and it is something that keeps him company after his long working days. He’s a friendly, happy guy, that despite everything, tries to see the best in the world.

#bio page#tw accident#tw death#about page#intro#proseintro#bioacal#yes this is an essay#i can't help myself

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

FULL NAME: Josephine "Joey" Fernando - Rivera

GENDER: demi woman

PRONOUNS: she / her

AGE + BIRTHDAY: 25, April 29th

LENGTH OF TIME IN FAIRFORD: Until she was 18, then recently returned in the past month

HOUSING: Mountainside

OCCUPATION: Bartender at Daring Daiquiri

warnings for teenager pregnancy , running away , abandonment , adoption

TEEN PREGNANCY / joey's story starts with her mother: raised by a single mom in the heart of vegas, her father nowhere to be found. sin city took a toll on joey's mother, isabela, and she became pregnant with joey very quickly as a teenager with a boy in her class.

RUNNING AWAY / instead of telling her mother, isabela and joey's father ran away ... within vegas and it's surrounding areas. it was easy to get lost within the lights and the tourists that packed the streets on a summer day. joey's dad found a slew of jobs that was enough to purchase a run down van, and they would park it behind his workplace.

ABANDONMENT / they lasted for a few months. isabela was 6 months pregnant, and joey's father promised to return to the small van they had been living in but never did. isabela was 18 and alone with nothing but herself. during this time, isabela decided to move north. she hitchhiked and caught rides with drivers from nevada to washington, settling in seattle and attempting to make a life for her now - smaller family.

josephine was born in the early hours of april 29th, surrounded by only her mother and the nurses. it was only hours later that joey would be placed into foster care. it would be best for the both of them.

ADOPTION / immediately was sent to live with a family from near - birth until she was 6. it was only foster care, never an actual adoption, and unfortunately the couple who were raising joey broke up --- them choosing to relinquish her back into care.

this is how she landed in her fathers ( bastian and his husband's ) care. call her cliche, but she considers this one of the best moments of her life and will happily encourage adoption, no matter how hard people think it is or the misconceptions.

childhood stuff ....

always the active child. always doing stuff, probably the one bouncing off the walls every day all day. did all the extra curriculars. tried out for sports, dance recitals, etc.

was a Soccer Superstar from ages 8 to 17, where she played goalie and offense.

diagnosed with adhd when she was around 12, and has been taking medication for it ever since. though she tries not to classify herself as a "stereotype", mostly because she hates that feeling of being put in a box.

used to follow bastian around and "help" on his odd jobs, despite not actually helping. grew up to be semi - handy with tools and all sorts of things.

bye fairford ....

she loves her family, but joey is definitely someone who does not settle down. she wanted to spread her wings so to speak, so she went to eckered college in florida on a soccer scholarship, right on the seaside to study archology, mostly because she thought it was funny and that she thought digging up dinosaurs was cool. fulfilling a kid pipe dream and all that, y'know?

her freshman year, one of her roommates + said roommates boyfriend were in a band, that needed a drummer. joey didn't know how to drum. she thought it would be easy. so she said she could do it.

particualry awful the first few tries, she found her way after practice. and the band was born.

they were actually semi - decent, despite the rocky start. they grew in the florida scene and joey thought they were going to make it big. they were selling out small venues, word gets around, they had a spotify and soundcloud. big stuff.

after they graduated, she was left with few options because the band ... dismantled and joey didn't really have any reason to stay in florida. she stayed for about two years before deciding she needed to come back home. it was different without her friends being able to do what they used to. it was all fun and games.. now it's over.

everyone grew up -- a few of the band members were engaged, others were too busy with their actual careers, child and more to carry on with the band. joey's just the drummer. she can't run the whole show by herself.

hiii ....

has returned to fairford after around 7 years to live full time, not counting vacations / family visits during holidays.

lives in a run down fixer upper in mountainside she got for cheap, and is slowly working on fixing it up as she has the time and energy. it's good stress relief and frankly she's kinda good at it. has an eye for design and all that. she loves sims.

is a bartender a few nights a week at the daring daqiuri. she's not a huge people person so it isn't her favorite thing in the world, but she's funny and charming in a fucked up way so people kind of like her, she hopes.

has a bit of resentment to her friends and it shows. the band is definitely tainted, bitter and angry about it. she thought they were in this together. the big leagues. but they all decided to .. quiet. she doesn't think she could ever forgive them for it, despite that being a bit... not rational.

other stuff

has never met her mother and doesn't have anything of hers. has vague memories of her previous foster parents before her dads, some photos and mementos but that's about it. she's curious but also terrified as to what she might find. it's not out of the question, but she's not going to chase a dream she wants crushed.

had a bit of a wild child streak in her teenage years. definitely did things she wouldn't supposed to ...... and dealt with the consequences.

she's sexually fluid and has been with anyone who she's found attractive. it doesn't matter to her -- she cares more about the connection than anything else.

kind of guarded and jaded, but if she loves you, she fucking looooves you. puppy dog kind of love.

ONLY GOES BY JOEY......... JOSEPHINE WILL NOT BE PRETTY

wcs

siblings!!! let her be a bad influence pls pls pls pls

perhaps people from florida who somehow moved to fairford?

an ex from high school: i think it'd be really fun to have this bc i imagine it like they were truly like in loooove and what not, except joey broke it off right before she left for college.

ex friends from fairford??? or maybe they kept it touch idk

new friends:DD

regulars at daring daqiuri who make her hate her life less.. they have a ball

hook ups / flings

enemies!!!

maybe. banter - relationships. they pick on each other so bad but it's all laughs .. or is it?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 1, 1966, a baby girl is born in Norfolk, Virginia. Her mother names her Melanie Lynn. She is placed in foster care for two months to make sure she has no medical issues. Then she is adopted by a couple who live a hundred miles away.

On a day in 1970, a baby girl is born in Incheon, South Korea, a port city just west of Seoul. Her mother names her Eun-hee. Eun-hee lives with her mother and her mother’s parents in Incheon until she is three years old. When she is nearly six, she is sent to adoptive parents in America.

On September 18, 1985, a baby girl is born in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Her mother does not give her a name. The mother relinquishes her at birth to an adoption agency. The mother is asked if she wants to hold the baby and says no.

One evening in December, 2021, Deanna Doss Shrodes had come home from work. The TV was tuned to a news segment about the oral arguments at the Supreme Court for the case that challenged Roe v. Wade. Deanna is a pastor and a director of women’s ministries at a Pentecostal church in Florida. She is opposed to abortion, and was glad that Roe might soon be overturned. But then Amy Coney Barrett asked about “safe haven” laws, which permit a mother who doesn’t want to keep her baby to drop it off anonymously in a deposit box at a hospital or a fire station.

Why, Barrett wanted to know, didn’t safe-haven laws remove the burden that was allegedly being imposed upon a woman who couldn’t obtain an abortion? The woman wouldn’t be forced to be a parent, and the baby could be adopted. At this point, Deanna became so upset that she stopped listening.

Deanna is adopted, and she has spent much of her life grappling with the emotional consequences of that. She believes that a child who starts life in a box will never know who they are, unless they manage somehow to track down their anonymous parents. It distresses her that many of her fellow-Christians, such as Barrett, talk about adoption as the win-win solution to abortion, as though once a baby is adopted that is the end of the story. If someone says of Deanna that she was adopted, she corrects them and says that she is adopted. Being adopted is, to her, as to many adoptees, a profoundly different way of being human, one that affects almost everything about her life.

“I explain to friends that in order to be adopted you first have to lose your entire family,” Deanna said. “And they’ll say, Well, yes, but if it happens to a newborn what do they know? You were adopted, get over it. Would you tell your friend who lost their family in a car accident, Get over it? No. But as an adoptee you’re expected to be over it because, O.K., that happened to you, but this wonderful thing also happened, and why can’t you focus on the wonderful thing?”

There are disproportionate numbers of adoptees in psychiatric hospitals and addiction programs, given that they are only about two per cent of the population. A study found that adoptees attempt suicide at four times the rate of other people.

“A big thing that adoptees get frustrated by is when people say that adopting kids is no different,” Deanna said. “You know, if they say, I don’t feel any differently about my biological kids than my adopted kids, I’m just a mom, we’re just a family. That is not true.” How many parents tell their adopted children, I love you as if you were my own? And how many of those children wonder, Am I not your own?

One day, when she was very little, Deanna was playing hide-and-seek with her sister. She wriggled underneath her parents’ bed to hide, and in the darkness she felt something hard and cold, made of metal. She pulled it out from under the bed and saw that it was a box. She opened it, and found a piece of paper with her name on it. The language on the paper was confusing, but she understood that it said that Melanie Lynn Alley, born in 1966, had become Deanna Lynn Doss.

Melanie Lynn Alley was another person, but also, somehow, herself. Deanna already knew that she was adopted, but she hadn’t known that she’d had another name. Was Melanie Lynn Alley the person she would have become if her birth mother had kept her? It felt as though Melanie was a part of her, but a part that she couldn’t see, that existed next to her, or behind her, like the ghost of a twin.

“Some people have no issues at all with being an adoptee,” Deanna said. “They’re happy as a lark. They don’t feel the pain, for whatever reason. But there are others who haven’t come out of the fog, or they don’t think they’re in a fog, or whatever. And they join one of the adoptee groups and they go, What’s wrong with all you people? I’m so happy, I’m so grateful, I don’t see what you’re upset about. That will create an explosion of people going, Why are you even here? This is a support group, not a place to come and talk about how happy you are.”

“Coming out of the fog” means different things to different adoptees. It can mean realizing that the obscure, intermittent unhappiness or bewilderment you have felt since childhood is not a personality trait but something shared by others who are adopted. It can mean realizing that you were a good, hardworking child partly out of a need to prove that your parents were right to choose you, or a sense that it was your job to make your parents happy, or a fear that if you weren’t good your parents would give you away, like the first ones did. It can mean coming to feel that not knowing anything about the people whose bodies made yours is strange and disturbing. It can mean seeing that you and your parents were brought together not only by choice or Providence but by a vast, powerful, opaque system with its own history and purposes. Those who have come out of the fog say that doing so is not just disorienting but painful, and many think back longingly to the time before they had such thoughts.

Some adoptees dislike the idea of the fog, because it suggests that an adoptee who doesn’t feel the way that out-of-the-fog adoptees do must be deluded. And it’s true; many out-of-the-fog adoptees do believe that. They point out that a person can feel fine about their adoption for most of their life and then some event—pregnancy, the death of a parent—will reveal to them that they were not fine at all. But there are many others who reject this—who aren’t interested in searching for their birth parents, and think about their adoption only rarely in the course of their life.

Although she found her birth mother decades ago, Deanna feels she came out of the fog more recently, because she hadn’t realized how many other adoptees were going through the same things she was. She and her husband had gone to see a movie about a girl who finds out that she is adopted at the age of nineteen. Deanna wept with fury during the movie, and when she discovered afterward that her husband didn’t understand what she was crying about, despite having been married to her since she was twenty years old, she went online and discovered that there were dozens, maybe hundreds, of Web sites on which adoptees were talking to each other.

It was a wild ferment of rage and pain, support groups and manifestos. Some adoptees were posting about lies and secrets: altered documents and birth dates; paperwork they’d been told was lost in a fire or a flood (so many fires and floods); birth parents they’d been told were dead but weren’t; things they’d been told about their past that the person who told them couldn’t possibly know. Others were arguing about whether there was such a thing as a primal wound—whether a baby bonded in utero with its mother and felt abandoned if it were given up, even if it were handed over in the delivery room. Some had found their birth parents and were in the middle of whatever that was; some were still searching and needed advice about DNA or genealogy; many were waiting to search until their adoptive parents died, for fear of hurting them. They were looking for pieces of their lives or their selves that were missing, or had been falsified or renamed, trying to fit them to the pieces they had.

There isn’t a single adoptee movement—the community is too heterogeneous for that. There is the older generation, the so-called Baby Scoop Era adoptees, such as Deanna—the mostly white children of the four million or so unmarried women who gave babies up for adoption between the end of the Second World War and the passing of Roe v. Wade. Many of those adoptions were forced, and almost all were closed—the identities of the birth parents and the adoptive names of their children were kept secret, making it very difficult for the parents and the children to find one another. There is the youngest generation, some of whom have open adoptions and have always known their birth parents, posting on adoptee TikTok. For some reason, it seems the vast majority of adoptees in the forums online are women.

One thing almost everyone agrees on is that adult adoptees should have the unrestricted right to see their original birth certificates, rather than only the “amended” ones with the names of their adoptive parents (but this is the law in only a dozen states). Many adoptees condemn international adoption, which cuts children off from their native cultures more drastically than any other kind and makes it unlikely that they will ever find, much less know, their birth parents. (Rates of international adoption by Americans have plummeted in recent years, down ninety-three per cent since 2004.) Some adoptees want to end adoption altogether, although most believe that there are situations in which it is the best option. More want to end transracial adoption—to return adoption, in some ways, to its modern beginnings.

A hundred years ago, adoption agencies tried to match children and parents so precisely that they could pass as a biological family. If parents wished to keep the adoption a secret, from the child or from the world, they could plausibly do it. Then, in the nineteen-fifties, some agencies set about persuading white parents to adopt children of color, with campaigns such as “Operation Brown Baby.” The campaigns were successful—by the start of this decade, nearly three-quarters of adoptees of color were adopted into white families. Four generations of parents loved children of races different from their own. In much of the adoption world, whose foundational premise is that love is stronger than biology, color-blindness still seemed like a precious and viable ideal. But then the adopted children grew up and some of them—though by no means all—believed that love was not enough.

Many adoptees feel that the way we understand adoption has been dominated by the perspectives of adoptive parents. Birth parents are less often heard from, though almost anyone can understand the grief of a parent who gives up a child for adoption (one study found more than ninety per cent of those who are denied an abortion keep their child rather than give it up). But understanding how adoption can affect an adoptee is more difficult, because adoptees, and the various kinds of adoptions, are so different from one another.

You can divide adoption into three main categories: plausibly invisible adoptions, such as Deanna’s, in which a child is adopted by parents of the same race; transracial adoptions; and international adoptions. Each of these has its own complexities and problems, and each is now going through a new reckoning.

Joy Lieberthal grew up just outside New York City; she had three younger sisters, all adopted from Korea, like herself. Her father was Jewish, her mother Catholic; Joy and her sisters were raised Catholic. When Joy first met her parents, she spoke no English, but she went straight into first grade and learned the language in three months. Once she spoke English, her mother would tell her stories about how Joy had behaved when she first arrived from Korea—how, when her father came home from work, she ran to pull off his jacket and shoes and take his briefcase and sit him down and give him a massage and sing for him. How, when her mother was mopping the kitchen floor, Joy gestured for her to stop, that she would do it—she ran to fetch a rag and scrubbed the floor on her knees until it was so clean you could eat off it, then wrung out the cloth so thoroughly that when she was done the cloth was dry.

Joy’s earliest memory was of leaving her mother’s parents’ house in Korea. She remembered being in the back seat of a car, banging on the window and crying, as somebody in the car rolled the window up. She could see her grandparents standing outside their house, also crying, waving goodbye. She knew that later she had lived in an orphanage for a year and a half, but she didn’t remember it well. She remembered that it had been cold—it was in the mountains. She remembered a river where she had washed her clothes and cleaned rice. She could picture the room she had slept in, with sunlight coming in.

Because Joy was nearly six by the time she left for America, she remembered the journey. First she had been taken from the orphanage to stay for a few months in a Buddhist temple in Seoul, where nuns had trained her for her new life. They taught her how to greet her American father at the door, how to give massages, how to wash clothes and floors, how to take care of younger children, how to sing for adults. She didn’t know what her life in America was going to be like, and it seemed that the nuns didn’t know, either, so they prepared her for whatever might happen.

On the day she was to leave for America, she wore a floral dress with a peacock on it. She was given a bag that contained a pair of pajamas, a pair of shoes, a notebook, a photo album that her American parents had sent her with pictures of themselves, and a gift that she was to present to her parents when she met them. The gift was a white box containing a little drawstring coin bag made of rainbow-striped saekdong silk. There were a few other Korean kids who were on the same flight, including a little girl who would become her younger sister. One of the adults with them at the airport told her to be good, to honor her parents, and to make Korea proud.

She and the other kids walked out onto the tarmac and the plane’s engine was going and it was incredibly loud. She hated loud noises, and she covered her ears and started to cry. On the plane, her ears hurt from the pressure, and she threw up on herself, then threw up again, and her nose started to bleed. The flight to J.F.K. was twenty-six hours long, with a layover in Anchorage. She didn’t remember arriving in New York, but she had seen a photo her parents took when she got off the plane, her peacock dress torn, a bloody Kleenex sticking out of her nose, her hair crooked. Her new parents were scary. They had blue eyes—she had never seen blue eyes. Her new sister ran away in the airport and everyone was busy trying to catch her.

She didn’t remember the car ride back to her parents’ house, but she remembered waking up when they got there, and getting out of the car carrying a string of lollipops and a new doll. She and her sister were led up the stairs, and at the top was their bedroom—yellow, with patchwork bedspreads. She took off her clothes and her sister’s clothes and folded them and helped her sister to put on her pajamas. They had never slept in a bed before and kept falling off, but they slept for a long time.

Her Korean name was listed as Kim Young-ja on the paperwork her parents were given, but they named her Joy. In fact, Kim Young-ja was not Joy’s original name, either—her name was Song Eun-hee. What had happened, as Joy understood it later, was that the director of the orphanage had originally promised Joy’s parents a different girl, but had been unable to deliver her. Not wanting to lose the customers, the director said that by great good fortune she had found a second girl with the same name and birth date as the first, so Joy came to her parents with falsified documents.

Joy was a good child who took care of her younger sisters. The sisters were close, but they never really talked about being adopted. Joy didn’t wonder about her birth mother, because she had been told she was dead. She was smart and worked hard in school, though there were almost no other Asian kids there, and she was bullied. She was a cautious child who tried not to be noticed.

There was something wrong with the baby. Her legs were rigid, and one of her feet was twisted sideways. A doctor in Chattanooga gave a diagnosis of spastic quadriplegia, a kind of cerebral palsy, and said that she might never walk.

The agency transferred the baby to a foster home, and the foster parents named her Jocelyn Kate. The foster parents were young white evangelical Christians. They already had two biological children but got certified as foster parents out of a sense of mission. They fell in love with the baby. They held her and touched her and rocked her and talked to her. The baby’s tiny legs were so stiff that the foster mother had to spend several hours every day massaging them, rotating her hips and stretching out her knees, to loosen them enough to change her diaper. The foster parents wanted very badly to adopt the baby, but they had no health insurance and couldn’t afford the medical care they’d been told she would need for the rest of her life. They had her for a year.

Meanwhile, the agency was looking for adoptive parents. At first they tried for a Black family, because the baby was Black, but they couldn’t find one that could take on the baby’s medical needs. After a few months, they broadened their search. David and Teresa Burt, a white couple who had already adopted one baby with cerebral palsy, were able to take a second with similar requirements. The agency wrote that their fee was normally five thousand dollars, but since this baby had special needs they would reduce the price to fifteen hundred. If that was too much, they would take a thousand.

The Burts lived in Bellingham, Washington, a small city north of Seattle. They wanted a big family, and, influenced by the Zero Population Growth movement, they decided to adopt. They had one biological child, a daughter, when they were in their early twenties, and then David had a vasectomy.

The first child they adopted, in 1982, was a one-year-old white girl with a diagnosis of cerebral palsy, who had been born weighing less than two pounds. About a year after that, they attended an event in Seattle called Kids Fest, sponsored by the state adoption office—children played, and if a prospective parent saw a child they were interested in they could try to interact with them. The Burts adopted a white boy they saw there.

A couple of years later, Teresa saw, in a binder of kids waiting to be adopted, a photo of a Black baby girl with cerebral palsy. The baby was cute, but it was the diagnosis that caught Teresa’s eye. They knew how to take care of a kid like that; they were already set up with the equipment. When the Burts arrived to collect their new daughter from the foster home in Chattanooga, they discovered that the foster parents had named her Jocelyn Kate. But the Burts thought of her as Angela, because that was the name a caseworker had put on the paperwork, and they decided to call her that. Later, the Burts went to Kids Fest again and adopted a second Black child, and a couple of years after that they took in a pair of Black sisters from foster care in Kentucky. As it turned out, it seemed that Angela did not have spastic quadriplegia but a much milder form of cerebral palsy. Her twisted-up foot slowly turned downward, and by the time she was four she was running as well as any other child.

Bellingham was a very white place. Some remembered it having been a sundown town as late as the nineteen-seventies: anyone who wasn’t white had to leave town by nightfall. It seemed to Angela that there were almost no Black kids in her elementary school. The family stood out in other ways as well—children of different races, some with visible disabilities, and sometimes a foster kid as well. There were always physical therapists coming and going in the house, and caseworkers with clipboards. One neighbor thought it was a group home. People in the grocery store would ask Teresa where she got all those children, and would say she was a saint for taking them in. Some people called her Mother Teresa. Teresa would reject these sorts of compliments, but they still made Angela feel like a charity case.

When Angela was a child, the only place she spent any real time with Black people other than her siblings was a summer program she went to with other adoptees. At home, she had Black people on TV. She saw that Magic Johnson’s big smile looked kind of like hers and wondered if he was her birth father. She wondered if her birth mother could be Brandy, from “Cinderella.” She asked her parents about her birth parents and they gave her her adoption paperwork.

She read this over and over. At first, all she thought about was her birth mother. When she was older, the fact that she had four siblings came into focus. Deborah’s fourth child, a daughter, had also been given up for adoption, and Teresa asked the agency to contact her family, to see if the girls could be pen pals, but the family said no.

Deanna grew up next to Jones Creek, just outside Baltimore. Her father worked at a post office downtown, her mother worked at the V.A. in Fort Howard. They couldn’t have kids, so they adopted two girls from different birth mothers, Deanna and her younger sister. The Dosses were conservative Pentecostal Christians, and their lives revolved around the church. Deanna often fell asleep under a pew during revival services that lasted into the night. When she was a child, sitting alone in her grandmother’s back yard, she realized that she had a calling to the ministry.

All through childhood, she wondered about her birth parents—who they were, where they lived, whether they ever thought about her. Whenever she was in a crowd of people, like at a baseball game in the city, she would scan the faces to see if there was anyone who looked familiar. Sometimes she stood outside looking at the moon and would wonder if her birth mother, wherever she was, was looking at the same moon. Every now and then, she asked her mother about her birth parents, but she felt that the subject made her uncomfortable, so she mostly kept her questions to herself.

She went to Valley Forge, a Christian college, and met her future husband, Larry Shrodes. In 1989, Deanna gave birth to their first child, and she realized that this was the first time she had seen and touched a blood relative since her own birth. She understood more than she had before what it would be like to give up a baby. Suddenly, finding her birth mother felt urgent.

She started going to meetings of the Adoptees Liberty Movement Association at a local Unitarian church. The organization had been founded in 1971 by an adoptee named Florence Fisher; Fisher had been in a car crash, and her last thought before impact was I’m going to die and I don’t know who I am. Deanna also contacted the agency that had brokered her adoption. She was told that she could petition the county court to open her records to a “confidential intermediary,” who would contact her birth mother on her behalf. She agreed, and before long the intermediary called to say that she had spoken to Deanna’s birth mother. The intermediary had told her that she would be proud of how Deanna had turned out—college educated, a pastor. The birth mother had said that she was sure she would be proud of Deanna, but she didn’t think that Deanna would be proud of her. She didn’t want to meet.

Standing holding the phone, Deanna felt her legs weaken. She thought that maybe her being a pastor had put her birth mother off—people always thought pastors were going to judge them. If only the intermediary hadn’t mentioned that. She asked if she could send her a letter, but the intermediary said no, that wasn’t allowed. Her birth mother had thirty days to change her mind. For thirty days, Deanna pleaded with God every way she knew. She fasted and prayed. But the intermediary called and told her that the answer was still no.

To be rejected by her birth mother a second time was almost more than she could take. But then, two years later, a pastor at her church told Deanna to pray about her mother again. This time, she felt God telling her that, although her birth mother had said no to the intermediary, she had not said no to her. Deanna restarted her search.

It was the early nineteen-nineties—there was no Internet that she had ready access to. But one day when she was home with the flu she saw Joseph J. Culligan, a private investigator, on a talk show. He had written a book, “You, Too, Can Find Anybody,” and guests on the show testified that, thanks to the book, they had used public information to find people for less than twenty dollars. Deanna sent Larry straight out to buy it. There were all kinds of techniques in the book, all kinds of records you could search for addresses if you had a last name—liens, leases, bankruptcies, writs of garnishment. You could write to the D.M.V. or check abandoned-property files. The best source, though, was the Death Master File, which contained the Social Security Administration’s death records since 1962. The Salvation Army’s missing-persons program told her that they knew of a source in California who could gain access to the Death Master File for only thirteen dollars. She knew that her birth mother had grown up near Richmond, Virginia. She called California and asked for records of any man in Richmond with her birth mother’s maiden name who had died within a certain period of time.

The information arrived in the mail a few weeks later—pages and pages of names. She wrote to libraries all over the city and ordered obituaries for every one of the names, looking for her mother’s father. From her adoption paperwork she knew that her maternal grandfather had been an auto mechanic with six children, and that her birth mother was the youngest. The last obituary she received in the mail was of an auto mechanic who had had six children. That gave her her birth mother’s current, married name. She dialled directory inquiries, got her mother’s number, and called her.

A machine picked up and she heard her birth mother’s voice for the first time. It was a deep, Southern voice. Deanna started crying. She called over and over. Larry came home, took one look at her, and knew instantly what had happened. At the time, they were both working as pastors at a church in Dayton, Ohio, and had two toddlers. Deanna called that evening to make sure that her birth mother wasn’t out of town; when she answered the phone, Deanna hung up. She and Larry took the kids and drove through the night to Richmond.

Deanna had been imagining this moment for years, and she knew exactly what she was going to do. She knew she had to look at her birth mother’s face at least once, so she wasn’t going to risk calling first. She had brought a camera—she would ask to take a photograph of her birth mother if it was to be the only time she saw her. The next day, in the hotel room, she changed clothes several times and settled on a pink suit. She waited until evening, walked up to her birth mother’s house, and knocked on the door.

The woman who opened the door was smiling, and blond, which took Deanna aback—the adoption paperwork had said that her hair was dark, like Deanna’s. Deanna said, Please don’t be afraid, but my name is Deanna, and I think you know who I am. The woman stopped smiling. For a long time, she stood in the doorway and stared at her. Deanna asked if she could come in.

Angela Tucker believes transracial adoption should happen only as a last resort.

Her birth mother gestured for her to sit at the kitchen table, and began nervously moving around from stove to counter and back, making coffee and picking things up and putting them down again. She said, I know you don’t understand why I made the decision I made. She started crying, and began to tell Deanna about all the mistakes she had made in her life and how sorry she was for all of them. She told her that she had made a lot of bad choices, including her relationship with Deanna’s father. She had failed in her relationship with her other children’s father, and now she was divorced. She listed other things she was ashamed of—things she’d done and things that had happened in her family.

Deanna felt God telling her, Say nothing, say nothing, just let her talk. She was terrified that something would break the spell and get her kicked out. She kept thinking, I’m still here, she hasn’t kicked me out, I’m still here.

When Deanna’s birth mother was pregnant, her parents had sent her to the Florence Crittenton Home for unwed mothers, in Norfolk, a hundred miles away. People had treated her like a whore, and she felt like a whore. Her family was mortified by her situation, and had told her that she must keep her pregnancy a secret or she would be disowned. She was told that giving up the baby for adoption and pretending the whole thing had never happened was her only chance to redeem herself. If she gave the baby up, it would be raised in a decent home, and she would be able to pass herself off as a marriageable woman. It was the right thing to do.

There was also no other option. The baby’s father had refused to marry her or help her. While she was alone in the home for unwed mothers, he just went on with his life. She lied on the adoption agency’s paperwork: she gave them a fake name for him and a fake job; she said he worked in a drugstore. She wanted to make sure that the child would never find him, or he her.

After a long time, Deanna’s birth mother stopped talking, and Deanna said, We’ve all made mistakes, but I went to Hell and back to find you, and I would go to Hell and back to find you again. At that point, her birth mother seemed to realize that Deanna was not going to reject her. She stood up from her side of the table, came over, wrapped her arms around Deanna’s head, and wailed.

When Joy went to college, at first she mostly had white friends. Then, in her second year, she became friends with a group of Black students and began to understand herself as a person of color. Later still, she made some Asian friends, and some Korean international students asked her to start an Asian student union. She felt like a fraud, as if she weren’t really Asian, but the international students accepted her as such, and thought it was fun to fill in the gaps in her knowledge. They wanted to know whether she could use chopsticks, how high her spice tolerance was. She ate with them and found that her mouth still watered when she smelled kimchi. She tried to teach herself Koreanness. She put on a fashion show, for which she learned how to wear hanbok and do a fan dance.

After she graduated, Joy decided to visit Korea. She wrote to the orphanage where she had lived and asked if they would take her on as a volunteer. They told her she was welcome. When she arrived, in the fall of 1993, everything felt very foreign. She spoke no Korean. Things smelled bad. The water was cold. What was she doing there?

She tried to compare the orphanage to her memories of it twenty years earlier. She remembered being cold all the time; now the building had indoor plumbing and central heating. She saw that the river she’d remembered washing clothes in was actually a stream. The director of the orphanage, who’d been there when Joy was a child and was now in her nineties, asked her, Are you here to meet your birth mother? Joy said, No, she’s dead, and the director said, Oh, yes, right, right, right.

After a few months at the orphanage, she felt something in her shift. She started to understand more Korean, and to speak it. She saw how hard the children worked—in school, and on the orphanage’s farm—and how much disciplinary beating and humiliation the younger ones endured at the hands of the older ones. There was little warmth or affection in the orphanage, no joking or playing games. They worked, watched TV, ate, slept. There were only a few staff members for more than fifty children, from little kids to seventeen-year-olds, and some seemed to have no interest in the children.

She also realized that none of the kids were actually orphans. They knew who their parents were, and most of them went home on national holidays. The orphanage was a combination of government boarding school and foster care—there was no American-style foster care in Korea. Usually there had been some kind of crisis in the family, like illness, or divorce, or poverty, that meant the parents couldn’t take care of their child. Most of the children thought their stay in the orphanage would be temporary, but often it wasn’t. Many became estranged from their birth families and couldn’t find them when they aged out.