#first quarto hamlet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

An AMENDED Rundown on the Absolute Chaos That is First Quarto Hamlet

O, gather round me, my dear Shakespeare friends And let me tell to ye a tale of woe. It was a dark and drizzly winter night, When I discovered my life was a lie... This tale is a tragedy, one of Shakespeare sources turned into gardening websites, "misdated" quartos, and failed internet archives. It is also a story of the quarto itself, an early printing of our beloved Danish Prince's play, including an implied Hamlet/Horatio coffee date, weird and extremely short soliloquies, and Gertrude with a hint of motivation and autonomy.

But let us start from the beginning. Long ago, in the year of our lord 2022, I pulled a Christmas Eve all-nighter to bring you this post: https://www.tumblr.com/withasideofshakespeare/704686395278622720/a-rundown-on-the-absolute-chaos-that-is-first?source=share

It was popularish in Shakespeare circles, which is why I am amending it now! I returned to it tonight, only to discover a few problems with my dates and, more importantly, a mystery in which one of my sources miraculously turned into a link to a gardening website...

Anyhow, let us begin with the quarto! TL;DR: Multiple versions of Hamlet were printed between 1603 and 1637 (yes, post-folio) with major character and plot differences between them. The first quarto (aka Q1) is best known for its particular brand of chaos with brief soliloquies, an extra-sad Hamlet, some mother-son bonding, weird early modern spelling, and deleted/adapted scenes with major influences on the plot of the play!

A long rundown is included below the cut, including new and improved sources, lore, direct quotes, and my own interpretations. Skip what bores you! And continue... if thou darest!

What is the First Quarto? Actually, what is a quarto?

Excellent questions, brave Hamlet fan! A quarto is a pamphlet created by printing something onto a large sheet of paper and then folding it to get a smaller pamphlet with more pages per big sheet (1). First Quarto Hamlet was published in 1603 and then promptly lost for an entire two centuries until it was rediscovered in 1823 in the library of Sir Henry Bunbury. Rather than printed from a manuscript of Shakespeare, Q1 seems like it may be a memorial reconstruction of the play by the actor who played Marcellus (imagine being in a movie, memorizing the script to the best of your ability, writing it down, and then selling "your" script off to the print shop), but scholars are still out on this (2).

Are you saying that Hamlet comes with the stageplay equivalent of a “deleted scenes and extra credits” movie disc?

Yep, pretty much! In fact, there are even more of these! Q2 was printed in 1604 and it seems to have made use of Shakespeare's own drafts, and rather than being pirated like Q1, it was probably printed more or less with permission. Three more subsequent quartos were published between 1611 and 1637, but they share much in common with Q2. The First Folio (F1) was published in 1623 and its copy of Hamlet was either based on another (possibly cleaner but likely farther removed from Shakespeare's own text) playhouse manuscript (2, 3). It was an early "collected works" of sorts--although missing a few plays that we now consider canon--and is the main source used today for many of the plays!

The versions of the play that we read usually include elements from both Q2 and F1.

So... Q1? How is it any different from the version we all know (and love, of course)? What do the differences mean for the plot?

We’ll start with minor differences and build up to the big ones.

Names and spellings

Most of the versions of Shakespeare's plays that we read today have updated spellings in modern English, but a true facsimile (a near-exact reprint of a text) maintains the early modern English spellings found in the original text.

For example, here is the second line of the play transcribed from F1:

Francisco: Nay answer me: stand and vnfold your selfe.

For the most part, however, the names of the characters in these later versions (ex: F1) are spelled more or less how we would spell them today. This is not so in Q1.

Laertes is “Leartes”, Ophelia is “Ofelia”, Gertrude is “Gertred” (or sometimes “Gerterd”), Rosencrantz is “Rossencraft”, Guildenstern is “Gilderstone”, and my favorite, Polonius gets a completely different name: Corambis.

(This goes on for minor characters, too. Sentinel Barnardo is “Bernardo”, Prince Fortinbras of Norway is “Fortenbrasse”, Voltemand and Cornelius--the Danish ambassadors to Norway--are “Voltemar” and “Cornelia” (genderbent Cornelius?), Osric doesn’t even get a name- he is called “the Bragart Gentleman”, the Gravediggers are called clowns, and Reynaldo (Polonius’s spy) gets a whole different name--“Montano”.)

2. Stage directions

Some of Q1's stage directions are more detailed and some are simply non-existent. For instance, when Ophelia enters singing, the direction is:

Enter Ofelia playing on a Lute, and her haire downe singing.

But when Horatio is called to assist Hamlet in spying on Claudius during the play, he has no direction to enter, instead opting to just appear magically on stage. Hamlet also doesn't even say his name, so apparently his Hamlet sense was tingling?

3. Act 3 scene reordering

Claudius and Polonius go through with the plan to have Ophelia break up with Hamlet immediately after they make it (typically, the plan is made in early II.ii and gone through with in III.i, with the players showing up and reciting Hecuba between the two events). In this version, the player scene (and Hamlet’s conversation with Polonius) happen after ‘to be or not to be’ and ‘get thee to a nunnery.’ I’m not sure if this makes more or less sense. Either way, it has a relatively minimal impact on the story.

4. Shortened lines and straightforwardness

Many lines, especially after Act 1, are significantly shortened, including some of the play's most famous speeches.

Laertes’ usually long-winded I.iii lecture on love to Ophelia is shortened to just ten lines (as opposed to the typical 40+). Polonius (er... Corambis) is still annoying and incapable of brevity, but less so than usual. His lecture on love is also cut significantly!

Hamlet’s usual assailing of Danish drinking customs (I.iv) is cut off by the ghost’s arrival. He’s still the most talkative character, but his lines are almost entirely different in some monologues, including ‘to be or not to be’! In other spots, however, (ex: get thee to a nunnery!) the lines are near-identical. There doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to where things diverge linguistically, except that when Marcellus speaks, his lines are always correct. Hm...

5. The BIG differences: Gertrude’s promise to aid Hamlet in taking revenge

Act 3, scene 4 goes about the same as usual with one major difference: Hamlet finishes off not with his usual declaration that he’s to be sent for England but with an absolutely heart-wrenching callback to act 1, in which he echoes the ghost’s lines and pleads his mother to aid him in revenge. And she agrees. Here is that scene:

Note that "U"s are sometimes "V"s and there are lots of extra "E"s!

Queene Alas, it is the weakenesse of thy braine, Which makes thy tongue to blazon thy hearts griefe: But as I haue a soule, I sweare by heauen, I neuer knew of this most horride murder: But Hamlet, this is onely fantasie, And for my loue forget these idle fits. Ham. Idle, no mother, my pulse doth beate like yours, It is not madnesse that possesseth Hamlet. O mother, if euer you did my deare father loue, Forbeare the adulterous bed to night, And win your selfe by little as you may, In time it may be you wil lothe him quite: And mother, but assist mee in reuenge, And in his death your infamy shall die. Queene Hamlet, I vow by that maiesty, That knowes our thoughts, and lookes into our hearts, I will conceale, consent, and doe my best, What stratagem soe're thou shalt deuise. Ham. It is enough, mother good night: Come sir, I'le prouide for you a graue, Who was in life a foolish prating knaue. Exit Hamlet with [Corambis/Polonius'] dead body. (Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

Despite having seemingly major consequences for the plot, this is never discussed again. Gertrude tells Claudius in the next scene that it was Hamlet who killed Polonius (Corambis, whatever!), seemingly betraying her promise.

However, Gertrude’s admission of Hamlet’s guilt (and thus, betrayal) could come down to the circumstance she finds herself in as the next scene begins. There is no stage direction denoting her exit, so the entrance of Claudius in scene 5 may be into her room, where he would find her beside a puddle of blood, evidence of the murder. There’s no talking your way out of that one…

6. The BIGGEST difference: The added scene

After Act 4, Scene 6, (but before 4.7) comes this scene, in which Horatio informs Gertrude that Hamlet was to be executed in England but escaped:

Enter Horatio and the Queene. Hor. Madame, your sonne is safe arriv'de in Denmarke, This letter I euen now receiv'd of him, Whereas he writes how he escap't the danger, And subtle treason that the king had plotted, Being crossed by the contention of the windes, He found the Packet sent to the king of England, Wherein he saw himselfe betray'd to death, As at his next conuersion with your grace, He will relate the circumstance at full. Queene Then I perceiue there's treason in his lookes That seem'd to sugar o're his villanie: But I will soothe and please him for a time, For murderous mindes are alwayes jealous, But know not you Horatio where he is? Hor. Yes Madame, and he hath appoynted me To meete him on the east side of the Cittie To morrow morning. Queene O faile not, good Horatio, and withall, commend me A mothers care to him, bid him a while Be wary of his presence, lest that he Faile in that he goes about. Hor. Madam, neuer make doubt of that: I thinke by this the news be come to court: He is arriv'de, obserue the king, and you shall Quickely finde, Hamlet being here, Things fell not to his minde. Queene But what became of Gilderstone and Rossencraft? Hor. He being set ashore, they went for England, And in the Packet there writ down that doome To be perform'd on them poynted for him: And by great chance he had his fathers Seale, So all was done without discouerie. Queene Thankes be to heauen for blessing of the prince, Horatio once againe I take my leaue, With thowsand mothers blessings to my sonne. Horat. Madam adue. (Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

First of all, the implication of Hamlet and Horatio's little date in the city is adorable ("Yes Madame, and he hath appoynted me / To meete him on the east side of the Cittie / To morrow morning.") It reads like they're going out for coffee!

And perhaps more plot relevant: if Gertrude knows of Claudius’s treachery ("there's treason in his lookes"), her death at the end of the play does not look like much of an accident. She is aware that Claudius killed her husband and is actively trying to kill her son and she still drinks the wine meant for Hamlet!

Now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for! My thoughts! Yippee! On Gertrude: WOW! I’m convinced that she is done dirty by F1and Q2! She and Hamlet have a much better relationship (Gertrude genuinely worries about his well-being throughout the play.) She has an actual personality that is tied into her role in the story and as a mother. I love Q1 Gertrude even though in the end, there’s nothing she can do to save Hamlet from being found out in the murder of Polonius and eventually dying in the duel. Her drinking the poisoned wine seems like an act of desperation (or sacrifice? she never asks Hamlet to drink!) rather than an accident.

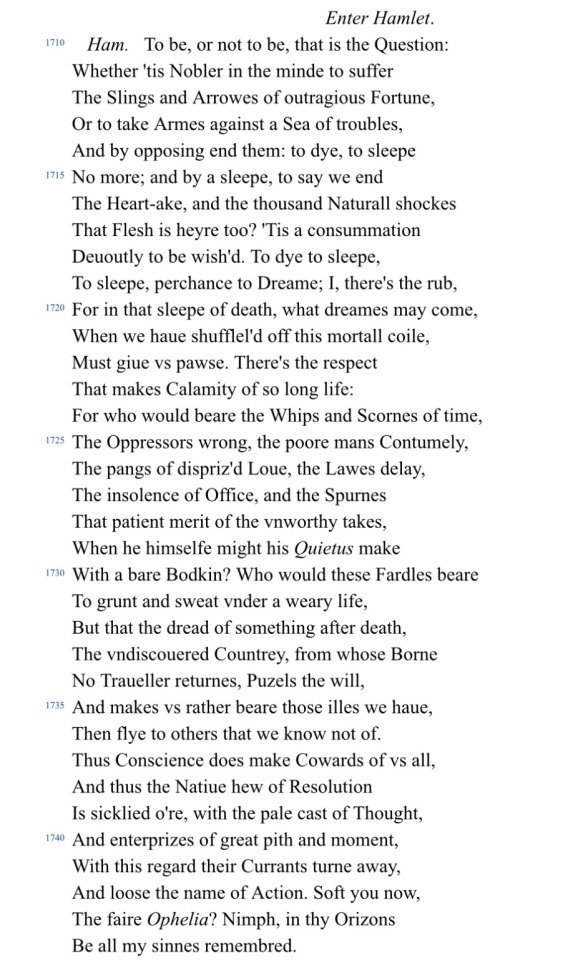

On the language: I think Q1′s biggest shortcoming is its comparatively simplistic language, especially in 'to be or not to be,' which is written like this in the quarto:

Ham. To be, or not to be, I there's the point, To Die, to sleepe, is that all? I all: No, to sleepe, to dreame, I mary there it goes, For in that dreame of death, when wee awake, And borne before an euerlasting Iudge [judge], From whence no passenger euer retur'nd, The vndiscouered country, at whose sight The happy smile, and the accursed damn'd. But for this, the ioyfull hope of this, Whol'd beare the scornes and flattery of the world, Scorned by the right rich, the rich curssed of the poore? The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd, The taste of hunger, or a tirants raigne, And thousand more calamities besides, To grunt and sweate vnder this weary life, When that he may his full Quietus make, With a bare bodkin, who would this indure, But for a hope of something after death? Which pusles [puzzles] the braine, and doth confound the sence, Which makes vs rather beare those euilles we haue, Than flie to others that we know not of. I that, O this conscience makes cowardes of vs all, Lady in thy orizons, be all my sinnes remembred. (Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

The verse is actually closer to perfect iambic pentameter (meaning more lines have exactly ten syllables and consist entirely of iambs--"da-DUM") than in the Folio, which includes many 11-syllable lines. The result of this, however, is that Hamlet comes across here as considerably less frantic (those too-long verse lines in F1 make it feel like he is shoving words into too short a time, which is so very on-theme for him) and more... sad. Somehow, Q1 Hamlet manages to deserve a hug even MORE than F1 Hamlet!

Nevertheless, this speech doesn't hit the way it does in later printings and I have to say I prefer the Folio here.

On the ending: The ending suffers from the same effect ‘to be or not to be’ does--it is simpler and (imo) lacks some of the emotion that F1 emphasizes. Hamlet’s final speech is significantly cut down and Horatio’s last lines aren’t quite so potent--although they’re still sweet!

Horatio. Content your selues, Ile shew to all, the ground, The first beginning of this Tragedy: Let there a scaffold be rearde vp in the market place, And let the State of the world be there: Where you shall heare such a sad story tolde, That neuer mortall man could more vnfolde. (Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

Horatio generally is a more active character in Q1 Hamlet. This ending suits this characterization. He will tell Hamlet’s story, tragic as it may be. It reminds me a bit of We Raise Our Cups from Hadestown. I appreciate that this isn't a request but a command: put up a stage, I will tell this story. Closing notes: After over a year, it was due time this post received an update. My main revisions were in regard to source verification. Somehow, in the last year or so, one of my old sources went from linking to a PDF of Q1 to a garden website (???) and some citations were missing from the get-go as a result of this being an independently researched post that involved pulling an all-nighter on Christmas Eve (but no excuses, we need sources!)

I have also corrected some badly worded commentary implying that the Folio's verse is more iambic pentameter-y (it's not; in fact, Q1 tends to "normalize" its verse to make it fit a typical blank verse scheme better than the Folio's does--the lines actually flow better, typically have exactly ten syllables, and use more iambs than Q1's) as well as that the spelling in the Folio is any more modern than those in Q1 (they're both in early modern English; I was mistakenly reading a modernized Folio and assuming it to be a transcription--nice one, 17-year-old Dianthus!) Additionally, I corrected the line breaks in my verse transcriptions and returned the block quotations to their original early modern English, which feels more authentic to what was actually written. A few other details and notes were added here and there, but the majority of the substance is the same.

Overall, if you still haven't read Q1, you absolutely should! Once you struggle through the spelling for a while, you'll get used to it and it'll be just as easy as modern English! If you'd prefer to just start with the modern English, I have also linked a modern translation below (source 5). And finally, my sources! Not up to citation standards but very user-friendly I hope... 1. Oxford English Dictionary 2. Internet Shakespeare, Hamlet, "The Texts", David Bevington (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_TextIntro/index.html) 3. The Riverside Shakespeare (pub. Houghton Mifflin Company; G.B. Evans, et al.) 4. Internet Shakespeare, First Quarto (facsimile--in early modern English) (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1/complete/index.html) 5. Internet Shakespeare, First Quarto (modern English) (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1M/index.html)

And here conclude we our scholarly tale, Of sources, citation, and Christmastime too, Go read the First Quarto! And here, I leave you.

#shakespeare#hamlet#first quarto#first quarto hamlet#classic literature#revisions#hey look at me#having some scholarly merit#i have so much left to learn#which is a darn good thing#how else would i spend my evenings?#the worst part about this#is that it all started because i thought a got a date wrong#but it turns out i didn't#so HA!#but then i realized i got everything else wrong so....#corrections it is!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

can't believe im discovering new shakespearian insults. 'god bless you prince hamlet!' 'god bless you too, because your ass stinks!'

#it is literally 'your balls stink'#mmaybe i wont translate it literally#hamlet posting#first quarto#marlocandia.txt#marlo's art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

first quarto hamlet my beloved…

#he is such a little shit (affectionate)#to me he seems younger than in some of the other versions#maybe it’s because the language is more simple#but i feel like he’s also more angsty and kind of blunt#instead of ‘i did love you once’ he says ‘i never loved you’#which sounds like something a bitter teenager would say#hamlet#first quarto

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Without the First Folio, we would have been stuck with the text of Hamlet as it appears in the “Second Quarto”, a cheap version probably rushed out to counter the success of a pirated edition, the notorious “First Quarto” of 1603. Even the Second Quarto suffers from typesetting errors—among the most egregious, its version of this monologue. Had they been working from the Second Quarto, Tennant and Essiedu would have graced the RSC stage lamenting the Almighty’s opposition not to self-slaughter—but to seale-slaughter.

As the Shakespearian scholar Jonathan Bate has observed, “ecclesiastical law as shaped by the Bible says nothing about the clubbing of baby seals.” We have yet to see a conservationist production of Hamlet take advantage of this variant (although its time will surely come). Thanks to the First Folio, it is the slaughter of the self, not the seal, that preoccupies modern Hamlets on stage.

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#first folio#hamlet#bad quarto#second quarto#seale slaughter#baby seals

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"'To be, or not to be, aye there's the point?' You stupid monkey!"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other source of “unauthorized” Elizabethan theater was minor actors recreating the scripts and publishing unauthorized version of them from memory. Except that it seems like Shakespeare’s minor actors were only given the scripts for the scenes they were actually in, so the rest of the play gets really messy really fast.

The funniest example is the probable origin of the (in-)famous “bad quarto” of Hamlet - published very shortly after the play’s first run, nearly 20 years before the “authorized” first folio was produced. It’s believed that this version was created by the actor who played Marcellus, an extremely minor role in the play.

We think this because the scenes in which that character is in (+ the Mousetrap, in which the actor probably played one of the in-universe performers) are pretty close to the “official” version of the play, with almost all of Marcellus’ lines exactly correct.

But the rest of the play….uh…well…

“Official” Version - First Folio Facsimile of Hamlet:

The “Bad Quarto” Version:

One of my favourite bits of media history trivia is that back in the Elizabethan period, people used to publish unauthorised copies of plays by sending someone who was good with shorthand to discretely write down all of the play's dialogue while they watched it, then reconstructing the play by combining those notes with audience interviews to recover the stage directions; in some cases, these unauthorised copies are the only record of a given play that survives to the present day. It's one of my favourites for two reasons:

It demonstrates that piracy has always lay at the heart of media preservation; and

Imagine being the 1603 equivalent of the guy with the cell phone camera in the movie theatre, furtively scribbling down notes in a little book and hoping Shakespeare himself doesn't catch you.

#i love the first quarto version of to be or not to be so much#it’s so terrible - like a drunk person trying to recall the lines just from pop culture osmosis#bad folio my chaotic beloved#hamlet#‘i mary there it goes…’#i should qualify that this is all technically only a THEORY and there’s still some debate among Shakespeare scholars#But it’s a pretty widely accepted theory

166K notes

·

View notes

Text

“To be, or not to be, I there's the point,

To Die, to sleepe, is that all? I all:

No, to sleepe, to dreame, I mary there it goes,

For in that dreame of death, when wee awake,

And borne before an euerlasting Iudge,

From whence no passenger euer retur'nd,

The vndiscouered country, at whose sight

The happy smile, and the accursed damn'd.

But for this, the ioyfull hope of this,

Whol'd beare the scornes and flattery of the world,

Scorned by the right rich, the rich curssed of the poore?

The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd,

The taste of hunger, or a tirants raigne,

And thousand more calamities besides,

To grunt and sweate vnder this weary life,

When that he may his full Quietus make,

With a bare bodkin, who would this indure,

But for a hope of something after death?

Which pusles the braine, and doth confound the sence,

Which makes vs rather beare those euilles we haue,

Than flie to others that we know not of.

I that, O this conscience makes cowardes of vs all,

Lady in thy orizons, be all my sinnes remembred.”

Hamlet, First Quarto (1603)

#incorrect literature quotes#shakespeare#hamlet#bad quarto#first quarto#i rise from the dead to bring you the stupidest version of hamlet there is

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hamlet’s Age

Not to bring up an age-old debate that doesn’t even matter, but I have been thinking recently how interesting Hamlet’s age is both in-text and as meta-text.

To summarize a whole lot of discussion, we basically only have the following clues as to Hamlet’s age:

Hamlet and Horatio are both college students at Wittenberg. In Early Modern/Late Renaissance Europe, noble boys typically began their university education at 14 and usually completed at their Bachelor’s degree by 18 or 19. However, they may have been studying for their Master’s degrees, which was typically awarded by age 25 at the latest. For reference, contemporary Kit Marlowe was a pretty late bloomer who received a bachelor’s degree at 20 and a master’s degree at 23.

Hamlet is AGGRESSIVELY described as a “youth” by many different characters - I believe more than any other male shakespeare character (other than 16yo Romeo). While usage could vary, Shakespeare tended to use “youth” to mean a man in his late teens/very early 20s (actually, he mostly uses it to describe beardless ‘men’ who are actually crossdressing women - likely literally played by young men in their late teens)

King Hamlet is old enough to be grey-haired, but Queen Gertrude is young enough to have additional children (or so Hamlet strongly implies)

Hamlet talks about plucking out the hairs of his beard, so he is old enough to at least theoretically have a beard

In the folio version, the gravedigger says he became a gravedigger the day of Hamlet’s birth, and that he’s be “sixteene here, man and boy, thirty years.” However, it’s unclear if “sixteene” means “sixteen” or “sexton” (ie has he worked here for 16 years but is 30 years old, or has he been sexton there for thirty years?)

Hamlet knew Yorick as a young child, and the gravedigger says Yorick was buried 23 years ago. However, the first quarto version version of Hamlet says “dozen years” instead of “three and twenty.” This suggests the line changed over time. (Or that the bad quarto sucks - I really need to make that post about it, huh…)

Yorick is a skull, and according to the gravedigger’s expertise, he has thus been dead for at least 7-8 years - implying Hamlet is at least ~15yo if he remembers Yorick from his childhood

One important thing sometimes overlooked - Claudius takes the throne at King Hamlet’s death, not Prince Hamlet. That is mostly a commentary on English and French monarchist politics at the time, but it is strange within the internal text. A thirty year old Hamlet presumably would have become the new monarch, not the married-in uncle (unless Gertrude is the vehicle through which the crown passes a la Mary I/Phillip II - certainly food for thought)

Honestly, Hamlet is SO aggressively described as being very young that I’m fairly confident the in-text intention is to have him be around 18-23yo. Placing his age at 30yo simply does not make much sense in the context of his descriptors, his narrative role, and his status as a university student.

However, it doesn’t really matter what the “right” answer is, because the confusion itself is what makes the gravedigger scene so interesting and metatextual. We can basically assume one of the following, given the folio text:

Hamlet really is meant to be 30yo, and that was supposed to surprise or imply something to the contemporary audience that is now lost to us

Older actors were playing Hamlet by the time the folio was written down, and the gravedigger’s description was an in-text justification of the seeming disconnect between age of actor and description of “youth”

Older actors were playing Hamlet by the time the folio was set down, and the gravedigger’s description was an in-text JOKE making fun of the fact that a 30-something year old is playing a high-school aged boy. This makes sense, as the gravedigger is a clown and Hamlet is a play that constantly pokes fun at its own tropes and breaks the fourth wall for its audience

The gravedigger cannot count or remember how old he is, and that’s the joke (this is the most common modern interpretation whenever the line isn’t otherwise played straight). If the clown was, for example, particularly old, those lines would be very funny

Any way you look at it, I believe something is echoing there. It seems like this is one of the many moments in Hamlet where you catch a glimpse of some contemporary in-joke about theater and theater culture* that we can only try to parse out from limited context 430 years later. And honestly, that’s so interesting and cool.

*(My other favorite example of this is when Hamlet asks Polonius about what it was like to play Julius Caesar in an exchange that pokes fun of Polonius’ actor a little. This is clearly an inside-joke directed at Globe regulars - the actor who played Polonius must have also played Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s play, and been very well reviewed. Hamlet’s joke about Brutus also implies the actor who played Brutus is one of the main cast in Hamlet - possibly even the prince himself, depending on how the line is read).

#hamlet#hamlet meta#hamlet’s age#this obviously does NOT imply anything about being 30yo btw#any age is a good age to be driven to madness by guilt and grief#It’s just very usual for shakespeare to describe somebody well past their apprentice age as a ‘youth’ SO MUCH#and that makes those lines very interesting#shut up e#willy shakes#posting this while EXHAUSTED going to see a million errors and tone problems tomorrow sorry in advance yall#**very unusual#long post#posting Hamlet meta like it’s 2014 hell yeah

905 notes

·

View notes

Text

i feel like reading hamlet (quarto 1) for the first time, then rereading fun home, which prompted me to read the picture of dorian gray for the first time is my english major canon event

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

just encountered first quarto hamlet for the first time in, apparently, my life, and what the fuck. we got queen gertred. we got ofelia and leartes and their dad corambis. and how could I forget that magnificent comedy duo, rossencraft and gilderstone! this is what happens when you order shakespeare off wish dot com

#hamlet#yeah yeah yeah spelling was loosey goosey and Shakespearean canon is the result of 400 years of editorializing#but CORAMBIS…

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

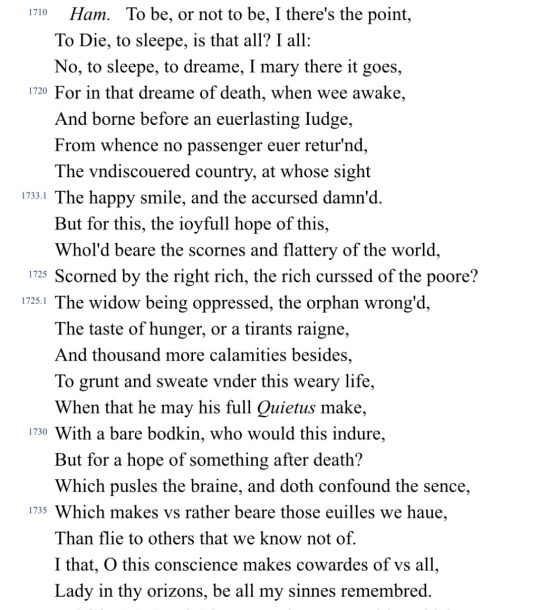

Shakespeare Weekend

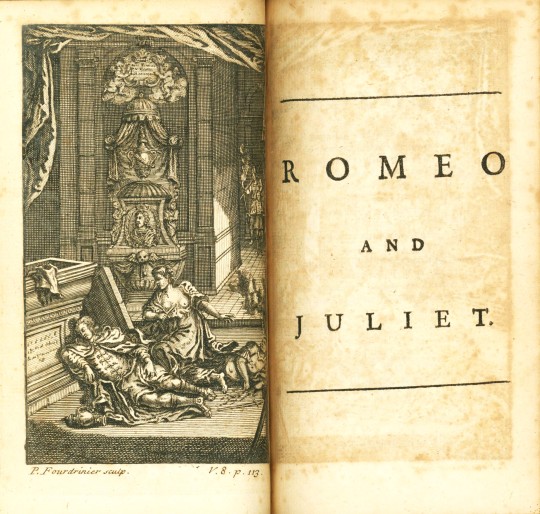

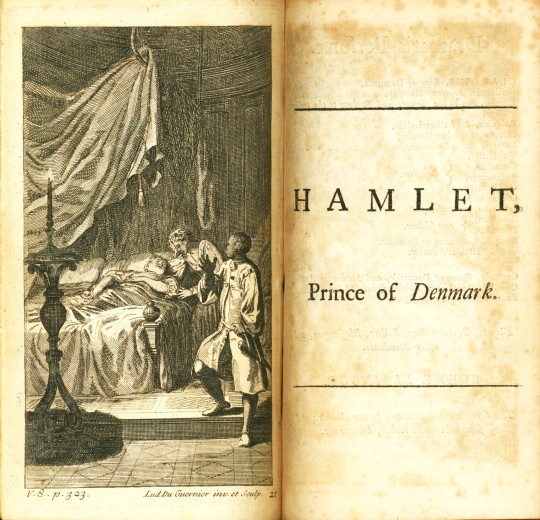

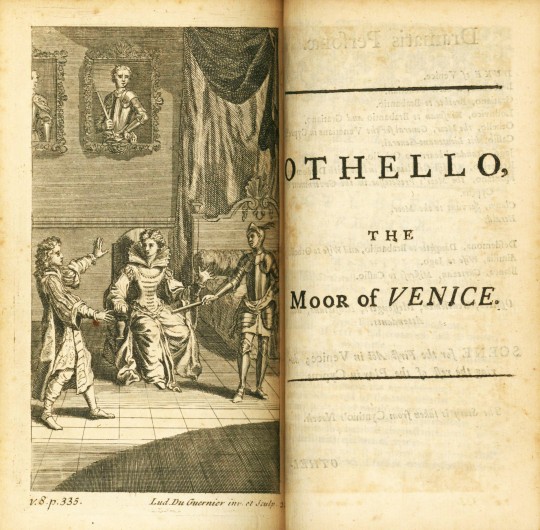

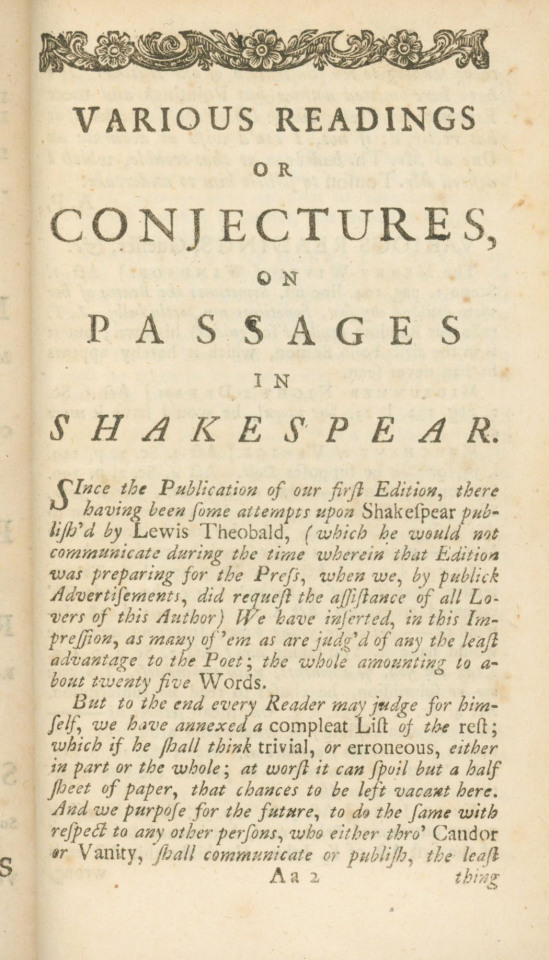

The works of Mr. William Shakespear: in ten volumes published in 1728 by Alexander Pope (1688-1744) and Dr. George Sewell (d. 1726) for Jacob Tonson (1655-1736), is considered complete in 8, 9, or 10 volumes. Pope’s second edition, as we see here, was published in 8 volumes with supplementary 9th and 10th volumes.

As such, Volume Eight includes an index of the characters, sentiments, speeches and descriptions found throughout the first eight volumes. It concludes with, in Pope’s words, “various readings and guesses” that Lewis Theobald (1688-1744) had published in 1726 as editorial amendments to the collection with the intent to “restore the true reading of Shakespeare”. In a bit of catty accusations, Pope claims Theobald had originally withheld his information at the time of the first pressing, and that he only used roughly twenty-five words of Theobald’s corrections in the second edition.

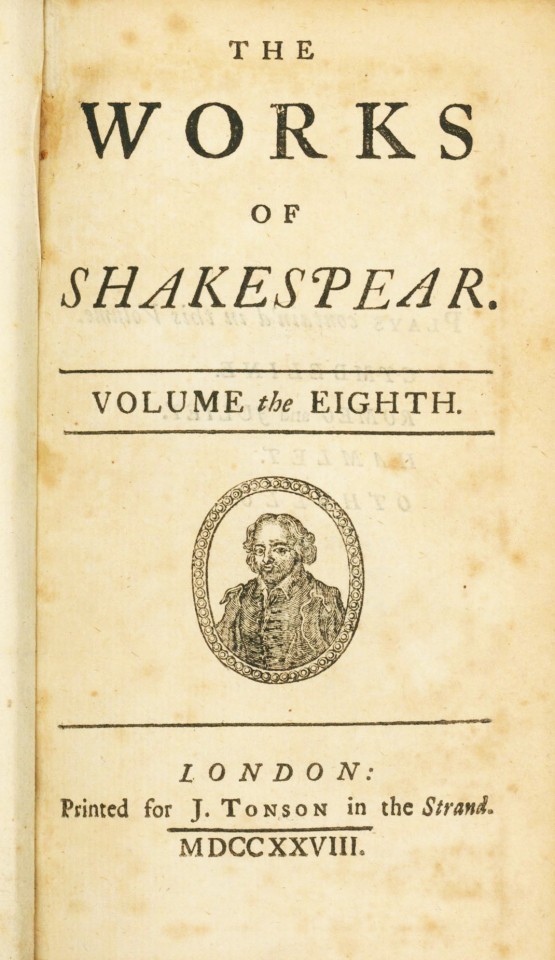

The plays within volume eight are all tragedies dealing with themes of innocence, jealousy, revenge, and fate; they include Cymbeline, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Othello. Pope notes that the story of Hamlet was not invented by Shakespeare but that its source is unclear. Regardless, Hamlet is hailed as one of the greatest plays of all time and at 29, 551 words is Shakespeare’s longest.

Pope’s editions of Shakespeare were the first attempted to collate all previous publications. He consulted twenty-seven early quartos restoring passages that had been out of print for almost a century while simultaneously removing about 1,560 lines of material that didn’t appeal to him. Scene divisions, stage directions, dramatis personae, and full-page engravings by either French artist Louis Du Guernier (1677-1716) or Englishman Paul Fourdrinier (1698-1758) precede each play.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#shakespeare weekend#william shakespeare#shakespeare#the works of mr. william shakespear in ten volumes#alexander pope#dr. george sewell#jacob tonson#lewis theobald#cymbeline#romeo and juliet#hamlet#othello#louis du guernier#paul fourdrinier#engravings

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

We all know that I am First Quarto Hamlet’s number one fan (and I’m probably the only one who thinks I don’t talk about it enough...) so I thought it was time I write out my thoughts on staging Q1′s version of act 3, scene 4, how it affects the plot, and how I understand the odd choices made by its players. Before we begin, here is a rundown on what Q1 is for the uninitiated: https://www.tumblr.com/withasideofshakespeare/704686395278622720/a-rundown-on-the-absolute-chaos-that-is-first?source=share

Another quick note: I will not be adjusting Q1 spelling for this so if it’s in quotes, the spelling errors are some dead guy’s fault. Now, here’s how I’d stage this scene! (Below the cut for your sake)

TW for murder and mention of sexual assault (mentioned by the quarto, not me!)

The first major change I’d make would be tonal. A lot of typical Hamlet productions tend to make this scene angry for Hamlet and terrifying for Gertrude, but I find that the overall tone of Q1 is more subdued. Sorry, Branagh, but no one’s screaming at each other in this production. There’s a quieter horror here. Hamlet enters Gertrude’s chamber calling to her: “Mother, mother, O are you here? How i'st with you mother?” This is significant because it almost seems like he’s let down his guard for a moment. Q1 Hamlet almost never refers to Gertrude as “mother,” only “madam,” and I like the interpretation that Claudius is behind this- Q1 Claudius has the vibes of a step-father who demands that his new wife’s kid refers to his parents as “sir” and “ma’am.” I’d want Hamlet’s tone to be familiar here. He trusts that he’s out of Claudius’s earshot and puts enough hope in Gertrude to assume she won’t rat him out. Upon arriving in her chamber, it should be clear to the audience that Hamlet has an uncanny sensation that he’s being watched. He already knows what he’s going to tell Gertrude (or at least the gist of it) and he knows that being overheard is extremely dangerous. He’s pretty frantic by this point in the play, so we get the line: “I'le tell you, but first weele make all safe.”

He seems to weigh his options through the next few lines. He looks back at the arras and guides Gertrude away from it, towards her bed. He takes a breath and draws his dagger. He has no intention to hurt his mother, but he is hoping that this half-threat will provoke any onlooker to come forward. Polonius (Corambis, whatever.) cries out from behind the arras and Hamlet whirls around and stabs him through the fabric. There’s no confusion in Hamlet’s next lines as we get in the later versions of the play, so I believe Polonius (Corambis... ugh) either falls forward and Hamlet sees his face or he manages to deduce who it is given that he just saw Claudius in another room.

Gertrude panics and tries to get up. Hamlet knows he only just has time to get a few words in to subdue her so he says the infamous “Not so much harme, good mother, As to kill a king, and marry with his brother.” She sits down again.

“How! kill a king!“

Hamlet seems to steel his nerves and carries on, his dagger sheathed. He takes down a portrait from the wall: the royal family before things went awry. He ignores his younger self smiling back up at him and turns the painting to his mother. “Why this I meane, see here, behold this picture, It is the portraiture, of your deceased husband, See here a face, to outface Mars himselfe, An eye, at which his foes did tremble at, A front wherin all vertues are set downe For to adorne a king, and guild his crowne, Whose heart went hand in hand euen with that vow, He made to you in marriage, and he is dead. Murdred, damnably murdred”

He watches her intently, gauging her reaction just as he’d instructed Horatio to do at the play. If she’d shrunk away from her now-murderer son before, now she listens intently. He carries on, taking a gamble:

“Looke you now, here is your husband, With a face like Vulcan. A looke fit for a murder and a rape”

He isn’t entirely sure what he intends to imply, but somewhere, subconsciously, he feels he’s right. Gertrude doesn’t want Claudius. (And I think in the context of the First Quarto, he’s right.)

She pleads with him to stop. Maybe she’d suspected Claudius, maybe not. Either way, now she has to keep quiet and pretend everything’s normal with confirmation that Claudius is a killer (and so too is her son...)

The ghost appears. Gertrude shivers. She can’t see or hear it, but she feels it. Hamlet drops the painting and leaps to his feet, torn between attentiveness and terror. Guilt crashes over him. He has failed to kill Claudius. He has killed an innocent man. Hamlet tries to conceal his sobs. The ghost steps towards him, its back to the audience. Hamlet is trembling, but we can’t see his face.

The ghost steps away as instructs him to comfort his mother and we see Hamlet pressed against the wall, tears in his eyes. He turns to Gertrude, mirroring the ghost’s motion, and chokes out “How i'st with you Lady?”

She responds: “Nay, how i'st with you That thus you bend your eyes on vacancie, And holde discourse with nothing but with ayre?”

It hits him all at once. She can’t see it, she can’t hear it, it can’t vouch for him. His tears spill over.

He prays he’s wrong.

“Why doe you nothing heare?”

“Not I.”

“Nor doe you nothing see?”

Gertrude isn’t sure what to think. If the mad prince tells her to believe that Claudius killed her first husband, does she dare listen?

She responds, shakily: “No neither.”

“No, why see the king my father, my father...” Hamlet reaches out as if to touch the ghost, but it only looks back, sorrowful, and strides away, vanishing into the air.

She says he is mad. She doesn’t know if she believes it. She doesn’t know what to believe.

Hamlet returns to her side and frantically places her fingers over his wrist. His heart still beats, doesn’t it?

“Idle, no mother, my pulse doth beate like yours, It is not madnesse that possesseth Hamlet.”

He isn’t sure whether he’s convincing her or himself. Gertrude pulls him into her arms. She can’t help it. She feels the blood on his hands, sticky against her dress. She pulls him closer.

He eventually pulls away and implores her on his knees:

“O mother, if euer you did my deare father loue...” He echoes the ghost’s if thou didst ever thy dear father love... half-intentionally. If the ghost cannot speak to her, he will. He must.

“Forbeare the adulterous bed to night, And win your selfe by little as you may, In time it may be you wil lothe him quite: And mother, but assist mee in reuenge, And in his death your infamy shall die.”

The ghost asked him to leave her to heaven. He fears what her judgment might bring. He loves her. He needs her. He can’t do this alone. He’s so scared and he just wants his mother’s affirmation that everything will be alright, that she will support him, that somehow, their family can be saved. He knows he’s lying to himself, but he can’t stop.

They make eye contact. Gertrude takes a moment before nodding and longer before she speaks, but she agrees.

“Hamlet, I vow by that maiesty, That knowes our thoughts, and lookes into our hearts, I will conceale, consent, and doe my best, What stratagem soe're thou shalt deuise.”

She holds his hands for a while, but her eyes drift towards Polonius’s (Corambis’s ARGH) body and Hamlet, who was facing away from it, suddenly realizes what he’s done all over again. He scrambles to his feet and wraps it in the arras before frantically dragging it out of the room and off stage.

Gertrude doesn’t move. She sits on her bed, breathing heavily, her head still turned towards the door. The pause feels long and drawn out. Too long. She stands very suddenly and grabs a rug, placing it over the bloodstains on the floor. She hangs up the painting and as she’s centering it, Claudius enters. (The Q1 cue is: “Exit Hamlet with the dead body. Enter the King and Lordes.” There is, notably, no exit cue for Gertrude. He comes to her, not the other way around.) She turns to face him. He greets her:

“Now Gertred, what sayes our sonne-”

He notices the blood on her dress. He looks down. The rug he’s standing on is soaking through with blood.

“How... how doe you finde him?”

She stands with her back to the audience, facing him, hardly moving. The panic and shock and horror hit her all over again and she reveals all:

“Alas my lord, as raging as the sea: Whenas he came, I first bespake him faire, But then he throwes and tosses me about, As one forgetting that I was his mother: At last I call'd for help: and as I cried, Corambis Call'd, which Hamlet no sooner heard, but whips me Out his rapier, and cries, a Rat, a Rat, and in his rage The good olde man he killes.”

What else is she supposed to do in her bloodstained dress, the carpet sticky with gore, and her portrait hung sideways on the wall? Something is rotten in the state of Denmark and Claudius can’t suspect it’s her. Not yet.

#hamlet#shakespeare#first quarto hamlet#q1 hamlet#she follows through on her promise when she drinks the poison in act 5#she knows.#she'd rather it be her than hamlet#q1 KILLS me#every time.#ALFLHSLFLFSGHLSFLSFK#and uh. that's how i'd do 3.4 Q1-style

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

post going around that I'm 80% convinced is historical misinfo on a topic I've studied but I don't have the effort or certainty to dispute it.

anyway.

folio - big fancy published book of plays. shakespeare's first folio was published posthumously by his contemporaries (Ben Jackson iirc).

quarto - pamphlet lil fuckers, often published by players in the plays (this is what I'm assuming op of the post I'm not replying to is on about).

the Shakespeare we know today is a mingling of works from quartos and the first folio merged because they changed in iterations. not a jot of it was published by shakespeare.

and don't get me wrong. equating that with modern plagiarism is very very different. the printing press is a fuckin new fangled thingymabob. but stagecraft itself is much much older.

the plays changed as they were performed. things worked, things didn't. sometimes the cannons you're using for sound effects set the theatre alight and kill an audience member (you'd change that bit for sure).

I think there are four versions of hamlet, maybe three. And elements change between them. Typos and errors create new meanings. Whole speeches are added and lost.

And over four hundred years people have been in with their editing pencils editing and making things fit.

The word 'bowdlerise' comes from a Victorian publishing of Shakespeare by the Bowdlers, who thought everyone should know shakespeare but wanted to censor the bits unsuitable for Victorian ethics.

Copyright is not really a thing in Shakespeare's day.

Stories are stories.

Plays consume themselves, recreate themselves. Playwriting is a more communal experience than you imagine. Strike out the tortured genius in the garret room. Put him in the theatre, among a maelstrom of voices who play the stage and know what works.

And thank fuck that quartos and folios found their way to the printing press, by any means

Writer's copyright is much younger than you'd think (Dracula had to be performed once on stage before Stoker had literary rights to it, centuries later)

anyway I did this a while ago so don't cite me lol. Might dig up my lecture notes later, if I can be fucked

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the first quarto because it reads like when a bunch of middle schoolers are forced to perform Hamlet in their English class

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just responded to one of your posts, realized it was from over 7 years ago and I’m. Not sure if you hold the same opinion as you did then, but I was about hamlet’s age. I wrote there that I had a slightly different take since I’m younger and a younger hamlet makes more sense in my eyes - authority, parents, control, choices and what you’re allowed to do, etc. - but I respect what you have to say and I don’t want to start discourse.

(Also, I’m aware that I’m probably spamming your account and I apologize for that.)

Spam away! Any meta on anything Shakespeare is my bread-and-butter by this point. I was going to do a separate post on the question of Hamlet’s age, but this will do for now.

With regards to Hamlet’s age, it’s both canonically clear and contentious. Hamlet is 30 in the Folio and Quarto 2 that have the Gravedigger’s line, “I’ve been a sexton, man and boy, for thirty years” and states clearly that he first began working on the day Hamlet himself was born (also when King Hamlet overcame Fortinbras).

The only proof of Hamlet’s being sixteen comes from Quarto 1–a.k.a the Bad Quarto, which is radically different from any other version of Hamlet, including Quarto 2 and the First Folio version.

The Bad Quarto may have been an abridged tour version for when Shakespeare’s troupe played the countryside—that is at least one plausible theory—but for the most part, critics have been reluctant to rely on the Bad Quarto completely. It’s just very, very mangled. The famous soliloquy in it begins “To be or not to be—ay, that is the point. To die, to sleep, is that all? Ay, all.”

Those that believe the Bad Quarto had it right and the Quarto and Folio are wrong believe that Shakespeare may have been making Hamlet’s age closer to the real-life age of Richard Burbage, who originated the role—the theory goes that audiences would not accept a portly 30-year-old playing a 16-year-old. Given that the Elizabethans had no problem with young boys playing girls and women and that Shakespeare’s troupe played characters of most all ages, this is really unconvincing to me.

If the Bad Quarto is indeed the correct one, then there is one logical explanation for the change: Shakespeare changed his mind. He decided not to have a sixteen-year-old Hamlet after all. It would explain why the “thirty years” line is consistent in all subsequent versions of the play and why Heminges & Condell did not change it. Either that, or the Bad Quarto transcriber simply drew on what he knew of the play or story from other sources—maybe that Ur-Hamlet supposedly written by Thomas Kyd—that did have a teen Hamlet.

So yes, young Hamlet does make sense in almost all respects (except, ironically enough, his attending university—royals had private tutors and only nobility went to university). But as far as canon goes, Shakespeare had a darker purpose in mind. Either way, it’s not as if 30 is super-old either, and in this day and age, you’ll find plenty of 30-year-olds still under their parents’ thumb.

#moonlarked#ask#hamlet#hamlet meta#william shakespeare#either that or shakespeare just erm forgot his character was a teenager#i think we overestimate the fucks shakespeare gave when it came to age

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

✨💖Positivity chain! List 5 to 10 things that make you smile and explain why! Then send this to others to let them know they make you smile✨💖

Thank you @softest-punk for sending me this ask. It made me feel warm and fuzzy. Let's see:

Dogs. Do I really need to explain why? They're dogs. They're the best. Especially the ones that let you pet them. I went to church yesterday after loooong absence. There was a dog (with his owner) sitting in a row behind me. He was a French Bulldog by the name Bear. I got to pet him. Never before had I received such a clear welcome back sign.

Libraries and bookshops. They are spaces full of books. Books I can pick up and look at and take with me if I so wish. I do love the fact that I can discover completely new things just picking a shelf at random and seeing what's there. The last time I wandered into a secondhand bookshop I found Shakespeare's Hamlet First Quarto 1603 Facsimiles. The bookseller sold it to me for 7 quid!

My friends. Both irl and online. Those people are in my life because they are awesome one way or another. Just thinking about them makes me smile. They're smart, creative, passionate, inquisitive, sometimes annoying, more often than not up for a laugh and always, always inspiring.

The moment before the performance starts. When the lights go down and the audience quietens in preparation to be transported. There's an ancient magic in that moment of stillness where we are waiting for the story to begin and anything, anything can happen.

Perfect seasonal days. It doesn't matter which season it is. I will take a snowy -20C winter's day and will enjoy it just as much as a sunny blue skied seemingly never-ending hot August afternoon.

Receiving old fashioned handwritten letters. Admittedly it has been a while. But is there anything better? Particularly in these times of instant digital communication. It's knowing that someone values you enough to go into all the effort of buying envelopes, sitting down to write and then actually going to the post office to post it. Can there be a bigger joy?

Lit candles in the evening. They make everything look more cozy, more mysterious, sort of hazy and with a hint of danger. I love the various smells they have. I love the memories they bring of childhood games where we would tell ghosts stories by candlelight or try to summon spirits.

Different colour pens. Especially if they have glitter in them. I bought a set of those on a whim and now my journal has random words in glittery purple and glittery orange. A little callback to a simple childish joy.

Making risotto. I love the whole process of standing over the pot and stirring for half an hour. I know most people find it boring. I find it meditative. Especially if there's a glass of wine and a good album playing in the background. I found Arctic Monkey's Tranquility Base Hotel And Casino works particularly well in this scenario.

Andrew Scott. Look, the man radiates joy. He's playful and ready to laugh at any moment. His acting talent is astonishing. He's not afraid to bring fashion to red carpets. He's thoughtful and sweet. He has the most gorgeous smile. What can I say, he makes me smile every time I see a photo of him.

#positivity list#they are not in order#I wrote them as they came to my head#I don't rate dogs higher than my friends#Most days anyway#I watched Sherlock at a formative age#and fell in love with a murderous psychopath

1 note

·

View note