#feminist spatial theory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Philosophy of the Eyes

The philosophy of the eyes explores the significance of vision as a primary means of perceiving and interacting with the world. It examines the relationship between sight, knowledge, beauty, and perception, and how the eye symbolizes awareness, truth, and consciousness in philosophical and cultural contexts. Vision has often been privileged in both epistemology (theory of knowledge) and aesthetics due to its ability to capture detail, distance, and spatial relationships, but the philosophy of the eyes also delves into its limitations and subjective nature.

Key Themes in the Philosophy of the Eyes:

Vision and Knowledge:

Sight is often seen as the primary sense through which humans gain knowledge about the external world. In many philosophical traditions, vision is closely linked with truth and clarity. The empirical tradition, especially in philosophy of science, relies heavily on what can be observed and measured visually.

However, philosophers such as Plato and Descartes have also questioned whether sight alone can lead to true knowledge, highlighting how the senses can deceive. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave suggests that what we see is often just shadows of the truth, while the real understanding comes from intellectual insight rather than sensory perception alone.

Eyes and the Mind:

The connection between the eye and the mind is central to many philosophical discussions, particularly in epistemology and phenomenology. The eye is not just a passive receptor but interacts with the mind to interpret and make sense of the visual stimuli it receives.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a key figure in phenomenology, emphasized how vision is embodied, meaning that seeing is not merely a function of the eyes but involves the whole body and consciousness. Our perception is shaped by our experiences, biases, and embodiment.

The Eye as a Symbol of Consciousness:

In various philosophical traditions, the eye symbolizes awareness and the mind’s ability to see beyond the physical world. The "third eye" in Eastern philosophy represents spiritual insight and higher consciousness. The eye of Horus in Egyptian mythology symbolizes protection and divine perception.

The eye is often used as a metaphor for the intellect, reason, or the soul. Descartes' "Cogito" (I think, therefore I am) exemplifies how self-awareness, akin to the eye seeing itself, is central to human consciousness.

Vision and Ethics:

The eye is central in discussions about ethical perception, or moral seeing. Seeing others, particularly in a Levinasian sense, involves recognizing the ethical demands they place on us. The act of looking at another can signify recognition, respect, or objectification.

The concept of "the gaze" has been discussed in existentialism and feminist theory. Jean-Paul Sartre argued that the gaze of others can objectify us, reducing our freedom. Laura Mulvey, in feminist film theory, discusses the "male gaze," where the act of looking is tied to power dynamics and objectification.

Eyes and Aesthetics:

The eyes are key in aesthetic philosophy, as vision is a primary way we engage with art, beauty, and nature. Visual beauty, both natural and created, is often one of the first experiences that lead to reflection on aesthetics.

The role of sight in aesthetic experience can raise questions about how we distinguish between superficial beauty and deeper, more significant forms of artistic or natural beauty.

Illusion and Reality:

The eyes are often associated with the concept of illusion, prompting philosophical reflections on the difference between what is seen and what is real. Philosophers from Plato to Kant have explored how vision can deceive, raising doubts about its reliability as a source of knowledge.

Optical illusions serve as practical examples of how the mind interprets visual information in ways that may not correspond to reality, challenging the assumption that “seeing is believing.”

Vision and the Sublime:

The eye’s capacity to perceive vastness and grandeur is tied to the concept of the sublime in philosophy. Experiencing vast landscapes, the night sky, or immense natural phenomena through vision often invokes feelings of awe and transcendence.

Philosophers like Kant have explored how the sublime reveals the limits of human perception, as what we see can overwhelm the senses and exceed comprehension, leading to both fascination and terror.

Vision, Time, and Memory:

Sight is also closely linked with time and memory. Our eyes capture moments that we store in memory, giving us access to the past. Philosophical inquiries into how memory works often involve visual recollections.

Henri Bergson discussed the relationship between perception, memory, and time, proposing that vision is one way we navigate the tension between the present moment and our past experiences.

Power and Surveillance:

In modern philosophy, particularly with thinkers like Michel Foucault, the eye is linked to power, especially in the context of surveillance. Foucault’s concept of the panopticon highlights how being under constant watch shapes behavior and exerts control over individuals, leading to philosophical discussions about the ethical implications of being seen.

The "eye of authority" also raises questions about who has the power to look, who is watched, and how vision is used to enforce social norms and hierarchies.

Eyes and Empathy:

Eyes are windows to emotional understanding and empathy. The ability to make eye contact and read emotions through facial expressions plays a key role in interpersonal relationships. Seeing another’s pain or joy can evoke empathy, leading to discussions in ethics about the moral obligations we have to others when we recognize their emotional states.

The philosophy of the eyes is rich and multifaceted, spanning discussions on perception, knowledge, aesthetics, ethics, and power. The eye symbolizes both the potential and the limitations of human understanding, as it is a primary means through which we engage with the world, yet it is also capable of deception and subjective interpretation. The eye's importance in human experience is reflected in its central role in philosophy, whether in understanding reality, contemplating beauty, or navigating social and ethical relationships.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ontology#metaphysics#psychology#Vision and Knowledge#Perception and Reality#Aesthetics of Sight#Ethics of Seeing and the Gaze#The Eye and Consciousness#Optical Illusions and Deception#Surveillance and Power#The Sublime and Vision#Memory and Time through Sight#Eye Contact and Empathy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog post 10/3

How does Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg challenge traditional feminist ideas about technology and identity?

Haraway’s cyborg challenges traditional feminist ideas by rejecting binary divisions such as nature vs. technology or male vs. female. Instead of seeing technology as something inherently oppressive or liberating, she advocates for a hybrid approach that navigates shifting boundaries. Her concept of the cyborg emphasizes partial connections and interconnectedness, arguing against universal theories or "perfect communication." By doing so, Haraway moves beyond essentialist notions of identity, offering a more flexible and inclusive framework that acknowledges how gender, race, and class intersect in relation to technology.

Why does Haraway distance herself from the term "cyberfeminism," and how does she critique its popular interpretation?

Haraway distances herself from "cyberfeminism" because the term, as popularly interpreted, often simplifies her complex ideas about the relationship between technology and feminism. While cyberfeminism focuses on how technology can offer women freedom in areas like identity and sexuality, Haraway is critical of how these narratives can overlook issues of race, colonialism, and class. She argues that many mainstream feminist movements and technological discourses marginalize women of color, failing to address how these groups are affected by the same systems of power. Haraway’s critique is that cyberfeminism, in its popular form, risks celebrating the empowerment of a privileged few while ignoring the structural inequalities that affect others

3. How did Pokémon GO expose racial and economic inequalities in the U.S., and why was this significant?

Pokémon GO revealed the entrenched racial and economic disparities in the U.S. by making players navigate both virtual and real-world spaces, often forcing minority players into uncomfortable or dangerous situations. For example, Black and Asian American players faced suspicion or violence in predominantly white neighborhoods. These incidents highlighted the persistence of de facto segregation and racial inequality, showing that even seemingly innocent games could be influenced by real-world social dynamics. The game's requirement for boundary-crossing, whether geographical or social, underscored how race remains a deeply ingrained factor in how people experience public spaces, challenging the notion that games are merely escapist or free from societal issues

4.What is "ludo-Orientalism," and how does it apply to the experience of Asian Americans in Pokémon GO?

"Ludo-Orientalism" refers to how games, through their design, marketing, and cultural rhetoric, reinforce racial hierarchies and perceptions of foreignness, particularly in relation to Asians and Asian Americans. In Pokémon GO, this dynamic is evident in how Asian Americans were perceived as outsiders, with the game reifying racial boundaries and spatial dislocation. Even though the game itself is Japanese in origin, the Asian American experience of being treated as perpetual foreigners—despite citizenship or birthplace—became a model for how all minority players were made to feel "othered" within the game's framework. This experience of otherness reflects the broader societal stereotypes and misperceptions of Asians in America, where they are both seen as model minorities and potential threats, depending on the context.

Kolko, B. E. (2000). Race in cyberspace.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Care to Cure and Back

Under the umbrella of the LINA platform a program From Care to Cure and Back was initiated by Ana Dana Beroš in collaboration with the Association of Architects of Istria (DAI-SAI). "Treat, cure and give care again", is the idea behind this program, says Ana Dana and stress how important is to deal with experimental publishing practices in architecture.

Ana Dana Beroš at the Publishing Acts: The Publishing School Pedagogies of Care in Rijeka (2020). | Photo © Matija Kralj Štefanić

She is referring how care was and is missing in the formal education of architecture, in the form of a humanistic way of thinking and asking background questions, which primarily concern the users of buildings. With the construction of the state, public projects fell into the background. It became clear that we must learn from our own history, repair, preserve and take care together, and not build unnecessarily.

How will architecture change in the future?

ADB: It will change drastically. I ask myself all the time is it ethical to build anymore? Or should we be focusing on “the great repair” of the broken world? Or is it broken architecture, or mankind, or more than human environment? This question are arising because we were witnessing for more than half of century the capitalist modernity, with its emphasis on innovation, growth, and progress, its economic system based on consumerism and wasteful use, and profligacy, has led to a ruthless exploitation of humans and nature.

Architecture has played a huge small part in this, as the statistics on greenhouse gas emissions and construction and demolition waste prove. As a counter-strategy to capitalism’s creative destruction, we should focus on the repair, in which nurturing and maintenance that should become the key strategies for the action.

Publishing Acts I-II-III (2017-2020) | Photo © Matija Kralj Štefanić, collage Ana Dana Beroš

This is not just mine thinking, the notions of care in architecture have been part of many international exhibitions starting from the Critical Care at the Architektur Zentrum in Viena curated by Elke Krasny and Angelika Fitz, the term The Great Repair was used by Milica Topalović and her team at ETH, then are here Pedagogies of the Broken Planet. This is how I see the future.

What does your critical spatial practice include?

ADB: My critical spatial practice has components of artistic research, documentary filmmaking, curating, publishing/broadcasting, exhibition design, activism and post-disciplinary de-schooling. This is work that overlaps, diverges, converges, runs in parallel, in circles, and in many cases came before and goes beyond.

A whole multitude of practitioners and theorists have been developing work in an expanded field such as this, quite different perhaps from the one Rosalind Krauss identified in 1979. Critical spatial practice was coined by the theorist Jane Rendell in 2000s as a helpful way of describe projects located between art and architecture, that both critiqued the sites into which they intervened as well as the disciplinary procedures through which they operated.

LINA - DAI-SAI programme From Cure to Care and Back. | Photo © Ana Dana Beroš

Taking into account the wide spectrum of intellectual fields close to architecture and space - from urban anthropology to human geography - I consider connecting architecture with feminist theory crucial for the development of critical spatial practices. Gender-based analysis of architecture, its multiple forms of representation, where subjects and spaces are viewed as performatives and constructs, is aimed primarily at questioning the world around us.

Moreover, critical spatial practices are necessarily self-critical and tend to change society, in contrast to orthodox architectural practices that seek to maintain and strengthen the existing social and spatial order of inequality.

How is the LINA platform important for your development on architecture of care?

ADB: I have started Architecture of Care actually developing through the concept of Pedagogies of Care within the predecessor platform to LINA, the former Future Architecture. The Publishing School: Pedagogies of Care is an exploration on how we learn and produce knowledge collectively through emancipatory practices of care. The program builds upon the three Publishing Acts and their collective efforts in shaping unordinary publications, unlikely publics and unorthodox spatial imaginaries.

Publishing Acts, The Publishing School -Pedagogies of Care (Rijeka, 2020). | Design © Marin Nižić

Can radio become again a media for architecture (like in the time of Wright) and in which way you work with it?

ADB: Regarding the radio, as a powerful architectural tool, or to the media that architecture uses, I can agree with many who say that architecture has nowadays become transmedial. We don’t create only in the offline dimension, in concrete and brick, but in the online sphere as well. All media are allowed, or rather necessary, to attain goals of architecture. I have been involved in radio forever as been working for Croatian radio HR3, I have been developing the Radio Schools with artists during the Pedagogies of Care. As our colleagues from dpr-barcelona we claim to this cover that radio is louder than bombs that relates to their motto.

Beside radio you work is also dedicated on documentary film?

ADB: My documentary work is dedicated both to architecture and migration topics. Within the Croatian Architects’ Association I have been leading, then co-leading a documentary project Man and Space and working as a scriptwriter on long feature documentaries dedicated to the life achievement laureates.

Geotrauma - Ana Dana Beros and Matija Kralj Štefanić at the V Magazine. | Foto © Marija Gašparović

In pluriannual research on the relational reading of migrant bodies and migrant territories, conducted together with the artistic partner and cinematographer Matija Kralj Štefanić, we have been departing from nonrepresentational theories, the practices of witnessing that produce knowledge without contemplation. The experimental documentary trajectory builds on previous investigations in the Mediterranean: in reception camps (Contrada Imbriacola, Lampedusa), hotspots (Moria, Lesbos), makeshift camps (Idomeni, Greece), urbanized camps (Dheisheh, Palestine), city refugees (Mardin, Turkey), and, recently, in the Balkans, where we live.

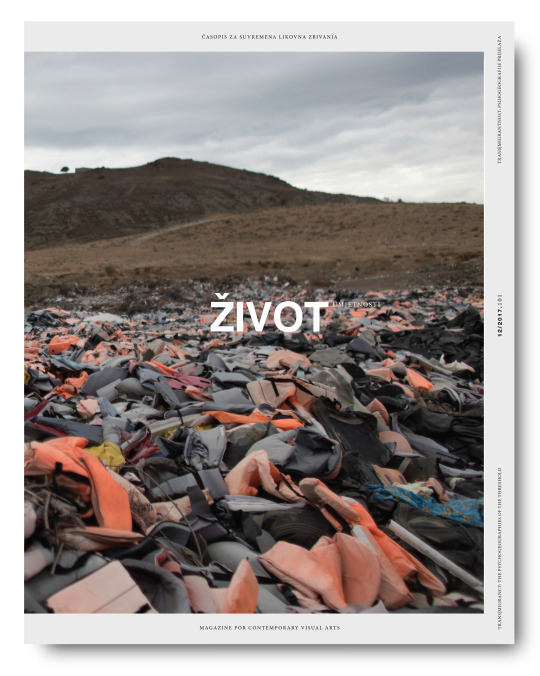

Transmigrancy - Life of Art Magazine, 101-2017 edited by Ana Dana Beroš: Geotrauma. Photo © Matija Kralj Štefanić (design bilic mueller studio)

We refined methods of producing critical, nonrepresentational images, and of gathering and documenting evidence found in borderscapes, in order to make a transmedial and migratory archive, a border documentarism, that is in constant articulation. After the pandemic, from mute images of migrants’ residuals that speak for themselves, we have started creating a polyphony of protagonists of migrant origin and those involved in the No Border movement in a documentary series Three-Voiced: Stories on the Move, broadcast in Croatia. As a contemporary response to the rise of fascist phenomena in Europe, In the era of fetishizing borders and territorialization of bodies, it was crucial to start resonating in a new voiced register for topics that are not heard, or rather systematically not listened to in our societies.

It is just one of many attempts at confronting structures of silencing, asking: Can we, through collective vibration, transform silence into a path of newfound hope and solidarity?

How Intermundia opened an important topic of transmigration in Europe?

ADB: Back in 2014, Intermundia research project questioned alternating border-scapes of trans-European and intra-European migration. The focus was put on the Italian island of Lampedusa, metonymy for contemporary Western conditions of confinement. For me, back then it was clear that the dominant discourses on illegal migration obscure the role of international migration as a regulatory labour market tool. It was important to stress that migrants must be conceived primarily as workers, not only as immigrants. It seemed that, in the pre-pandemic times of constant mobility, involuntary territorial shifts of the precarious workers was parallel to the detention of undesired migrants.

Intermundia at the Venice Biennial in 2014. | Foto © Ana Opalić

Instead of observing Lampedusa as a consolidated institution of the waiting room, as a jailed zone in the middle of conflict, Intermundia attempted a post-human perspective in order to investigate the ambivalent state of in-betweenness. I was aware of the impossibility of cultural translation of such a condition, the understanding of the Other, so the project Intermundia, exhibited and awarded at the Architecture Biennial in Venice 2014, challenged visitors to immerse themselves into a coffin-like light and sound installation. Inducing Verfremdungseffekt, the project asked for solemnity and re-action, and not simply empathy.

I am not sure Intermundia opened the important topic of migration in Europe, but for sure it was a predecessor to the summer of migration in 2015, with the great influx of migrants, refugees and the formation of the so-called Balkan Route.

What does architecture mean to you?

ADB: I dare to say that the fundamental task architecture has is to articulate spatial thinking, thinking capable of asking questions about burning issues of our society in a different way, hence of also creating a different reality. Architecture must offer a space for understanding of the existential condition of an individual and of society, and must also construct a foundation for a life with dignity. We know who we are, and where we belong, precisely through human constructions, both material and intellectual.

Intermundia "Io sono Africanicano". | Photo © Ana Dana Beroš

Ana Dana Beroš (b. 1979) is an architect based in Zagreb, but often explores contested borderscapes of Europe and beyond. Co-founder of ARCHIsquad - Division for Architecture with Conscience and its educational program UrgentArchitecture in Croatia. Her interest is architectural theory, experimental design and publishing as spatializing practice led her to co-found Think Space (2010-2015) and Future Architecture (2016-2021) international platforms, and currently LINA (2022-2025). The LINA member DAI-SAI ongoing project From care to cure and back, under her curation, explores critical architectural heritage on the case of The Children’s Maritime Health Resort of Military Insured Persons in Krvavica, and encourages transformation of both material and immaterial environments from spaces of a common disease into places of common healing. Her project Intermundia on trans- and intra-European migration was a finalist for the Wheelwright Prize at GSD Harvard, and received a Special Mention at the XIV Venice Architecture Biennale curated by Rem Koolhaas (2014). In her pluriannual research and relational reading of migrant bodies and migrant territories, she departs from non-representational theories, the practices of “witnessing” that produce knowledge without contemplation. The fragments of the migratory archive, a border documentarism formed together with the filmmaker and cinematographer Matija Kralj Štefanić, have been made public in different forms and formats, exhibitions and publications (2016-2022) – and lately within a documentary series Three-voiced: Stories on the move (2022-).

Here You can listen to the WELTRAUM interview

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trans-Spaces:

Reviewing the Application of Queer Theory and Gender Studies in the Design of Transitional Spaces.

This literature review will examine and analyse the existing contemporary literature relevant to applications of queer theory and gender studies in the architectural discipline, whilst identifying a further need to focus on transitional spaces. The aim in applying queer theory and gender studies as a theoretical approach in the design of transitional spaces is to create public accessibility and inclusivity. The discussion will summarise and critique queer and gender-diverse approaches to architecture, and the design of public-facing transitional spaces, before justifying the need for further research.

Debates, Controversies and Foundations:

Early applications of feminist and queer theory in the late 20th Century focused on cis-women, lesbians and gay men - such as in the 1999 text Gender Space Architecture, Betsky’s Queer Space, and Sander’s Stud - inadvertently excluding gender-diversity (Betsky, 1997; Borden et al., 1999; Sanders, 1996). There was a shift in seminal formulations of a distinctly trans-theory by Halberstam and Nagoshi & Brzuzy, theorising broader representations of transgender lives (Halberstam, 2005; Nagoshi et al., 2014). Crawford attempted to remedy “architectural theory’s marginal treatment of transgender” lives, with hesitancy amidst debate regarding the theorisations of lived-experiences subject to “erasure, murder, violence and ridicule in public space” (Crawford, 2016; Moore & Castricum, 2020). Furman and Mardell’s archival examination of criminal records further highlights the erasure of queer spatial history and need for safety (Furman & Mardell, 2022). Queer theory and gender studies is inherently politically charged, foregrounded in the debate of public bathrooms as an intersection of architecture and gender-diversity; with practice-based interventions such as ‘Stalled!’ attempting to find gender-neutral solutions (Jess Berry et al., 2020; Sanders, 2017). Literature further debates the risk of elevating the fluidity of queer people to unrealistic levels of ability to challenge structural institutions, underpinned by the paradoxical nature of a queer methodology (Crawford, 2016; Jobst & Stead, 2023). The literature presents a post-modern understanding of a queer methodology, encompassing non-normative sexualities, trans-, gender-diverse and gender-non-conforming identities, with ‘queer’ shifting from a noun, into a verb; ‘to queer’ or ‘queering’ meaning “to unsettle established relations and norms” of society and the architectural discipline (Jobst & Stead, 2023). It is commonly argued queering involves challenging and rethinking conventional disciplinary methods and approaches; seen in the use of experimental writing, case-studies, archival and practice-based research.

Queering Architecture: Gender Performativity

Judith Butler - considered a founder of gender studies - first introduced the theory of gender as a continual social performance in 1990, resulting in a paradigm shift (Butler, 2006). Butler rejected gender as a fixed natural reality; finding gender is constructed by repetitive acts which create reality; upheld by institutions of patriarchy and biological essentialism (Butler, 2006). Laqueur further supported Butler, finding ‘biological sex’ lacked empirical evidence and perpetuated the oppression of women as less than, or opposite to men (Laqueur, 1992). Ahmed’s later dissertation on queer phenomenology found lived experiences to be performed by the orientation of bodies in space, “shaped by histories,” the repetition of interactions, and the spatial production of “straight tendencies,” or cis-heteronormativity, foregrounding discussions of gender performativity within architecture (Ahmed, 2006).

Within literature there is acknowledgment of architecture as an upholder of normative gender and sexuality, with debate regarding architecture’s repetitive performance of “longstanding essentialism,” and the further need for queering to subvert social constructions (Angelopoulou, 2017). The much-cited thesis Behind Straight Curtains first explored the performance of gender in architecture through a theatrical interpretation of case-studies (Bonnevier, 2007). Caldwell and Smitheram find that if gender is performed; then a space free from institutions, and experienced as queer is also performed through a “collaboration between bodies, materials and forces” (Caldwell & Smitheram, 2023). Canl1 further envisions space as “constantly being reperformed,” with the ability to subvert “gender-charged” power structures by instead performing queer modes of being in a “dissident form of world-making” (Canl1, 2023). It is generally agreed that architecture is subject to and maintains the continual social performance of gender, with queering aiming to dismantle cis-heteronormativity and patriarchy associated with constructions of binary gender.

Resistance to Binary Oppositions and Cis-Heteronormativity

Eve Sedgwick, regarded as a pioneer of queer theory, supports Butler’s theory of gender performativity finding the performance of normalised binary categorisations of sexuality and gender underpin Western society, highlighting socio-political fragmentation due to regulation within institutions such as architecture, leading to marginalisation’s of queerness and gender-diversity (Butler, 2006; Sedgwick, 1990). A queering of architecture aims to resist authoritative binary definitions of sexuality and gender, and associated cis-heteronormativity, leading to the deconstruction of various binaries - from Halberstam’s theorising of queer time as moving “beyond the binary division of flexibility or rigidity” and resisting “institutions of family, heterosexuality and reproduction,” to Herring’s challenging of the urban and rural binary, or “metronormativity,” present within discussions of queering cities (Halberstam, 2005; Herring, 2010).

Ahmed suggests the bodily occupation of space reproduces and affects the performance of social binaries, with spaces historically orientated around a standardised straight cis-body; proposing queering can radically “reorder” these standards to form new modes of inhabitation (Ahmed, 2006). Vallerand further explores the performance of social binaries in domesticity, using case-studies to reveal a coinciding spatial binary of private and public; proposing a “blurring” can resist binary gender roles within the home; supported by Queering the Interior (Gorman-Murray & Cook, 2020; Vallerand, 2020). Gough further explores gay clubs as case-studies, proposing a “transing of gender” and architecture can deconstruct essentialist binary definitions of gender and sexuality, and subsequent constructed architectural boundaries (Gough, 2017). Further literature supports this queer deconstruction of architectural boundaries alongside social binaries in considering the wall as a spatial binary. Canl1 makes the comparison between the division of space with walls, to the barriers faced by queer identities, supported by Crawford arguing “the demarcation of spatial boundaries plays out disproportionately on transgender people and others” (Canl1, 2023; Crawford, 2016). Caldwell and Smitheram, in their practise-based research, theorise the wall as a political force used to “control and orientate our bodies” and “divide people up;” denoting ideas of access and belonging, whilst speculating a blurring of “social and spatial binaries,” within a “nesting of scales” using alternatives, such as the curtain (Caldwell & Smitheram, 2023).

Embodiment of Queer and Gender-Diverse Lived Experiences

Gender performativity and resistance to binary oppositions and cis-heteronormativity in a queering of architecture is commonly underpinned by the embodiment of queer and gender-diverse lived and bodily experiences. Early theorisations of trans-theory, such as that of Halberstam and Nagoshi & Brzuzy, emphasised “the significance of the transgender body” as fluidly embodying resistance to normalised social binaries; foregrounding the self-construction of identity as core to challenging social constructions (Halberstam, 2005; Nagoshi et al., 2014). Canl1 and Ahmed consider the spatial embodiment of socially-constructed binaries to be through the “lived experience of inhabiting a body” in space; with interactions between objects, such as skin and surface, contributing to the normalised exclusion of ‘othered’ bodies (Ahmed, 2006; Canl1, 2023). Canl1 further finds this co-creation of normative identity and space can become “penetrable, diffusive and processual” in a reimagination of architecture as the embodiment of queerness, therefore in a constant state of becoming and transformation (Canl1, 2023). Crawford supports this discussion considering archival narratives of queer “agency, experiences and resistances to human actors” embodied within modernist architecture, examining the “fluidity of the trans body” as a “model” for the transformation of architectural conventions (Crawford, 2016). This concept is reinforced in Angelopoulou’s interdisciplinary case-study research, speculating the queering of architecture is through destabilising acts of “dis/continuity” in the design process, found in the medical transformation of transgender bodies, or “trans-modification,” relating surgical cuts, to cuts in architectural drawings, software and structures (Angelopoulou, 2017). It is widely debated that it is the embodiment of queer and gender-diverse narratives of lived experience within the transgender body and its uses of space that challenges conventions of architecture, gender, and sexuality leading to both bodily and architectural transformations.

Transitional Spaces:

Existing literary discussions of transitional spaces are foregrounded by movement and negotiation of behaviours through and beyond the public and private binary, heralding the queer deconstruction of social binaries. Kimmel’s case-study research employs a critical lens to analyse the social and spatial “requirements and impacts of” of transitional spaces, namely the threshold (Kimmel, 2021). It is accepted that the threshold links “public space with publicly accessible buildings,” acting as a spatial boundary creating “material enclosures” navigating tensions within society enacted between the interior and exterior, whilst aiming to resist the “homogenisation of space” (Kimmel, 2021; Lathouri, 2019). Lathouri’s archival research further finds - using a political lens to propose contemporary applications - that transitional spaces deal with “the space-in-between,” interacting with boundary thresholds and generating liminal experiences of “interiority and proximity” that negotiate individual and collective modes of being and usage (Lathouri, 2019). Similarly, Kimmel finds as “enhancers of social interactions” demarcating “broader socio-political contexts in public and private space” - transitional spaces have the ability to “orchestrate different behaviours” related to status, power and control; delineating experiences of segregation and marginalisation, whilst contributing to the “publicness” of adjacent spaces as reflections of social conditions (Kimmel, 2021). Lathouri further argues transitional spaces are “a condensed expression of human life itself” as they reconsider the relationship between human agency and social structures and construct social reality (Lathouri, 2019). There is agreement that the “recalibration of boundaries” within transitional spaces becomes a socio-political site of resistance, constructing “alternative social…patterns” related to public “access and visibility,” finding a greater impact upon marginalised “communities that are usually invisible” with encounter and connection encouraging sociability, diversity, and “public life” (Kimmel, 2021; Lathouri, 2019).

Queering Transitional Spaces: Liminality: Subverting Binaries

Literature regarding transitional spaces find them to be “small theatres of social life,” performing social constructs of gender and sexuality within liminal movement between binaries such as the public and private (Kimmel, 2021). It is further theorised that transitional spaces negotiate the individual and collective, with queer spatial embodiments establishing self-constructed experiences as integral to the subversion of socially-constructed norms (Lathouri, 2019; Nagoshi et al., 2014). Therefore, the queering of transitional spaces can be justified in the connection between transitional spaces’ theorised liminality and queer approaches to subverting spatial and social binaries. Moore and Castricum further suggest queering architecture requires “looking inside the liminal spaces between the repressive binaries we are forced into by hetero and cisnormativity” proposing a need for further practise-based speculation of transitional spaces as a microcosm of social institutions such as gender and sexuality (Moore & Castricum, 2020).

Transformative Potential

The ability of transitional spaces to modify behaviours; found by Kimmel, can be linked with the transformative potential of body and architecture in mutual co-creation; found in the consideration of lived experiences and bodily occupations in queering architecture (Kimmel, 2021). Canl1 considers the “transformative potential of queerness” in its fluidity; akin to Kimmel and Lathouri’s consideration of transitional spaces as sites of change, with the ability to encourage alternative modes of usage and sociability, such as a queer experience (Canl1, 2023; Kimmel, 2021; Lathouri, 2019). Canl1 further contemplates the domestic corridor as a transitional or “liminal space between worlds” where transformation takes place, arguing the “in-betweenness” creates possibilities heralding Lathouri and Kimmel’s findings that transitional spaces are “sites of intimacy, socialisation and interaction” (Canl1, 2023; Kimmel, 2021; Lathouri, 2019). The justification for the application of queer and gender-diverse approaches in transitional spaces can be found in Canl1’s finding that marginalised people reside in transitional spaces as they are in a “constant state of displacement,” finding comfort in decentralised and destabilised public places where boundaries and identities are blurred, such as transitional spaces (Canl1, 2023). However, contemporary literature is yet to take the consideration of the transitional space out of the domestic and into the public scale, with a queering lending itself to the blurring of scales as seen in Caldwell and Smitheram (2023). Crawford’s proposal of “transing” justifies the further speculation of a queer transformation in the public realm, considering the collaboration and movement that can happen “across bodies, buildings and milieus” in an act similar to that theorised by Lathouri as experiences of movement transform relationships and boundaries within transitional spaces (Crawford, 2016; Lathouri, 2019) There is a present lack of explicit consideration of queer lived experiences and gender-diverse bodies in transitional spaces, therefore, research is required regarding the processes involved in designing transitional spaces as the site of queering and transformative potential.

Inclusivity and Accessibility

A need to focus on the design of transitional spaces with a queer and gender-diverse approach persists; with an aim to foster “inclusive, participatory, safe and accessible” public spaces, as suggested by Contentious Cities, consistent with debates regarding the embodied transformative potential of queer lived experiences, and the advent of liminality within transitional spaces to subvert spatial and social binaries (Jess Berry et al., 2020). Kimmel’s consideration of status, power and control within transitional spaces and the focus on “publicness” indicates an awareness of accessibility and inclusivity issues and need for further application of queer and “gender-sensitive participatory design” processes; such as that used by Kalm and Bawden as “an equalising force used to create spaces…of inclusion” and address power dynamics (Kalms & Bawden, 2020; Kimmel, 2021). Jobst and Stead establishes a connection between queering and concepts introduced by Kimmel, in the advocacy of queering the interior and exterior binary as a “container of private and public voids” which provides visibility and access to spaces where sexuality and gender “resides and enacts itself” without delving further or explicitly exploring transitional space design (Jobst & Stead, 2023; Kimmel, 2021).

There is a clear need to apply queer and gender-diverse approaches to the design of transitional spaces in processes and practices beyond the bathroom and domestic applications; to foster inclusivity and accessibility foregrounded by safety, visibility and participation that starts with queer and gender-diverse lived experiences and extends to all marginalised communities in their transformative potential and subversion of binaries.

References: Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/4/monograph/book/70074 Angelopoulou, A. (2017). A Surgery Issue: Cutting through the Architectural Fabric. FOOTPRINT, Trans-Bodies / Queering Spaces(21), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.7480/footprint.11.2.1899 Betsky, A. (1997). Queer space: Architecture and same-sex desire (First edition). William Morrow and Company, Inc. http://www.gbv.de/dms/weimar/toc/198223609_toc.pdf Bonnevier, K. (2007). Behind Straight Curtains: Towards a queer feminist theory of architecture [KTH]. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-4295 Borden, I., Penner, B., & Rendell, J. (1999). Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unisa/detail.action?docID=169967 Butler, J. (2006). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203824979

Caldwell, A., & Smitheram, J. (2023). Blurring Binaries: A Queer Approach to Architecture through Embodied Connection. The International Journal of Architectonic, Spatial, and Environmental Design, 17(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1662/CGP/v17i02/151-167 Canl1, E. (2023). Notes from transient spaces, anachronic times: An architextural exercise. In Queering Architecture: Methods, Practices, Spaces, Pedagogies. Bloomsbury Visual Arts. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350267077 Crawford, L. (2016). Transgender Architectonics: The Shape of Change in Modernist Space. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315550039 Furman, A. N., & Mardell, J. (Eds.). (2022). Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTQ+ Places and Stories. RIBA Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003297499 Gorman-Murray, A., & Cook, M. (Eds.). (2020). Queering the Interior. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003086475 Gough, T. (2017). Trans-architecture. FOOTPRINT, Trans-Bodies / Queering Spaces(21), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.7480/footprint.11.2.1900 Halberstam, J. (2005). In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unisa/detail.action?docID=2081650 Herring, S. (2010). Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism. New York University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unisa/detail.action?docID=866116

Jess Berry, Timothy Moore, Nicole Kalms, & Gene Bawden (Eds.). (2020). Contentious Cities | Design and the Gendered Production of Space | Jes (1st ed.). https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781003056065/contentious-cities-jess-berry-timothy-moore-nicole-kalms-gene-bawden Jobst, M., & Stead, N. (Eds.). (2023). Queering Architecture: Methods, Practices, Spaces, Pedagogies. Bloomsbury Visual Arts. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350267077 Kalms, N., & Bawden, G. (2020). Lived experience: Participatory practices for gender-sensitive spaces and places. In Contentious Cities. Routledge. Kimmel, L. (2021). Architecture of Threshold Spaces: A Critique of the Ideologies of Hyperconnectivity and Segregation in the Socio-Political Context. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003133889 Laqueur, T. (1992). Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Harvard University Press.

Lathouri, M. (2019). IMAGINING THE SPACE-IN-BETWEEN: The Elaboration of a Method. Arhitektura, Raziskave, 2019, 173-191,268. Moore, T., & Castricum, S. (2020). Queering architecture: Simona Castricum and Timothy Moore in conversation. In Contentious Cities. Routledge. Nagoshi, J. L., Nagoshi, C. T., & Brzuzy, S. (2014). Gender and Sexual Identity: Transcending Feminist and Queer Theory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8966-5 Sanders, J. (Ed.). (1996). Stud: Architectures of Masculinity. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003014720 Sedgwick, E. K. (1990). Epistemology of the closet (Updated ed. / preface by the author.). University of California Press. Vallerand, O. (2020). Unplanned Visitors: Queering the Ethics and Aesthetics of Domestic Space. McGill-Queen’s University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unisa/detail.action?docID=6944697

0 notes

Text

Patrick Gray, John D. Cox - Shakespeare and Renaissance Ethics-Cambridge University Press (2014).pdf Paul Cefalu - Revisionist Shakespeare_ Transitional Ideologies in Texts and Contexts (2004).pdf Paul Raffield, Gary Watt - Shakespeare and the Law (2008).pdf Paul Yachnin, Jessica Slights - Shakespeare and Character_ Theory, History, Performance and Theatrical Persons (2009).pdf Penny Gay - The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare's Comedies (Cambridge Introductions to Literature)- (2008).pdf Peter G. Platt - Shakespeare and the Culture of Paradox (Studies in Performance and Early Modern Drama) (2009).pdf Peter Holbrook - Shakespeare's Individualism (2010).pdf Profiling Shakespeare-Routledge.pdf Rebecca Ann Bach - Shakespeare and Renaissance Literature before Heterosexuality (2007).pdf Richard Dutton, Jean E. Howard - A Companion to Shakespeare's Works, The Poems, Problem Comedies, Late Plays -Wiley-Blackwell (2003).pdf Richard Dutton, Jean E. Howard - A Companion to Shakespeare's Works_ The Comedies -Wiley-Blackwell (2003).pdf Richard Dutton, Jean E. Howard - A Companion to Shakespeare's Works_ The Tragedies -Wiley-Blackwell (2005).pdf Robert H. Bell (auth.) - Shakespeare’s Great Stage of Fools-Palgrave Macmillan US (2011).pdf Robert Weimann - Author’s Pen and Actor’s Voice_ Playing and Writing in Shakespeare’s Theatre-Cambridge University Press (2000).pdf Robertson - Montaigne and Shakespeare.epub Robin Bates - Shakespeare and the Cultural Colonization of Ireland (Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory) (2007).pdf Roslyn Lander Knutson - Playing Companies and Commerce in Shakespeare's Time (2001).pdf Russell Jackson - The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film, 2nd Edition (Cambridge Companions to Literature) (2007).pdf Russell West - Spatial Representations and the Jacobean Stage_ From Shakespeare to Webster (2002).pdf Saddleback Educational Publishing - Shakespeare Made Easy, Julius Caesar-Saddleback Educational Publishing (2006).pdf Sarah Werner - Shakespeare and Feminist Performance_ Ideology on Stage -Routledge (2001).pdf Stanley Stewart - Shakespeare and Philosophy (Routledge Studies in Shakespeare)-Routledge (2009).pdf Steven Adler - Rough Magic_ Making Theatre at the Royal Shakespeare Company (2001).pdf Steven Adler - Rough Magic_ Making Theatre at the Royal Shakespeare Company-Southern Illinois University Press (2001).pdf Taylor G., Jowett J., Bourus T., Egan G. (General Editors) - The New Oxford Shakespeare. The Complete Works. Modern Critical Edition - 2016.pdf Tetsuo Kishi, Graham Bradshaw - Shakespeare In Japan (2005).pdf Tiffany Stern - Making Shakespeare_ From Stage to Page (Accents on Shakespeare) (2004).pdf Tom MacFaul - Poetry and Paternity in Renaissance England_ Sidney, Spenser, Shakespeare, Donne and Jonson-Cambridge University Press (2010).pdf Tom McAlindon - Shakespeare Minus ’Theory’-Routledge (2016).pdf

0 notes

Text

Aledis the Blue Yorkie

Meet Aledis, a Littlest Pet Shop OC (original character) that I created on October 2019. Before I could tell information about this character, I like to say what I have done on February 2, 2024 in the morning. Initially, I was going to archive more files that I considered necessary and that were only found in a desktop computer that used to run Windows 7. Unfortunately, when I started up said desktop computer, I found out that it has been broken down sometime after the end of support of the Professional and Enterprise volume licensed versions, making most of them lost media. What a pity that I couldn't archive them before that software rot!

In compensation of what happened to the older computer, I had to write the following information of this original character from memory:

Name: Aledis

Age: More or less the same as Brown Yorkie

Species: Dog (Yorkshire Terrier)

Gender: Cisgender female

Personal gender pronoun: She/Her

Alignment: Social good

Likes: Literature (especially fiction books and poems), rationalism, science (especially physics) and art

Dislikes: Pseudoscience, fringe theories, blockchain and similar concepts, negative evaluation

Description: Aledis is a blue-furred Yorkshire Terrier that is commonly seen wearing a wreath of flower in her left ear and a green bandana in one of her forelegs. She also has a white star-shaped birthmark that is slightly hidden in her neck's fur. Namewise, Aledis' attitude is described as being intelligent, innovative, progressive, adventurous, and slightly rebellious. As a result, Aledis herself is feminist and will fight for animal rights. Despite being a ratter, Aledis can spare the lives of rodents, including mice and rats. However, she has fear of negative evaluation and a slight spatial anxiety. In some occasions, she is able to take one for the team when necessary. She is depicted as the cousin of Brown Yorkie and is rational enought to be skeptical about magic and paranormal events.

Biography: Aledis was born in Pets Plaza (a place that is found exclusively on the 2008 video game adaptation of Littlest Pet Shop) along with her two siblings. One day, Aledis was suddenly become displaced from her original dimension. To make matters worse, she discovers that the planet she is sent to, the Glade of Dreams, contains hostile beings that are more dangerous compare to that of her native parallel world. In order to deal with it, Aledis uses the survival skills her mother taught earlier. During the journey, she meets a like-minded dweller of the Glade of Dreams that she befriends. Eventually, both of them are sent to a more peaceful world and, over time, she befriends two more female nonhuman characters from different parallel universes.

If anyone asks when Aledis appeared for the first time, the earliest drawings featuring her were first posted on Rayman Pirate Community, as I have a currently inactive account and Aledis used to be the co-mascot of this account along with a Rayman OFC (original female character). As drawn in an approximately five-year-old paper, she originally looked like this in an old artstyle:

Yes, the older picture is a model sheet in the form of traditional art, and it is written in Spanish. By January 2023, I have improved this art style to the current one (such as the digital art I have made for Aledis) so that I removed these drawing quirks found on her head for consistency. Therefore, it's time to give her a chance to make a comeback.

Aledis the Blue Yorkie © Me (@piscessheepdog) Littlest Pet Shop © Hasbro (previously owned by Kenner)

#aledis the blue yorkie#littlest pet shop#lps art#digital art#fan art#fanart#lps oc#original character#original female character#littlestpetshop#yorkshire terrier#oc original character#dog oc

1 note

·

View note

Note

Helloww, as a fellow literature student... what's a favourite theory/critic/movement of yours?

Oh hi, what a fun question, thank you so much!!!! 🥰

I'd say I'm generally not very set on any school or theory which is most likely due to the fact that my uni isn't very keen on teaching different theories, sadly.

But I looooove anything coming out of cultural studies! So obviously feminist and gender and queer theory, but what I reeeeeaaaally love as well is spatial theory, idk if that even counts as a distinct theory tbh, but.... spaces. My beloved <3

Oh and I love theories that go a bit into sociology, like field theory, my beloved <3

As for critics, can't say I have a favorite. I mean there are the "classics" that inform lots of my views on literature, but no one I know a lot from.

As for movements!!! Honestly, anything from the 19th century on is very much my jam. I love naturalism and I love expressionism, but also lots of the smaller (sub)movements like Wiener Moderne or Dada. All in all I'm a big fan of Modernism and some of the stuff that happened like... on the brink of Modernism (depending on the definition of Modernism you wanna go by)!

1 note

·

View note

Text

_thinkMake Week 3 Reading

This week's reading was 'Only Resist - a feminist approach to critical spatial practice' by Jane Rendell. I found this text quite hard to decipher.

This key parts I picked out from this text were:

Architecture as a profession was historically ‘masculine’ and male dominated in the early 1900s and before, due to the lack of women’s right to work.

Identity is an important aspect of the human condition and so should have the space to exist.

Representation is important when making spaces.

From the text, I picked out the 5 main qualities that characterise the feminist approach to critical space practice:

Collectivity - the importance of collaboration in the creation of something. Women's voices must be heard during the design process of anything, as women are often ignored and not considered, or designed for without being consulted.

Subjectivity - life is often thought about in binary opposites, whereas most things in life are subjective and rely on contextual clues. Historically, architecture has been a men's profession and interior design was a woman's. However, this is not the case.

Alterity - the state of being 'other' or different. Intersectionality is the combination of race, class and gender and how they overlap to create further discrimination and disadvantage. It is important to consider everyone when designing something so that no one is disadvantaged.

Performativity - the interdependent relationship between certain words and actions. Using text as a platform to create performance and action allows a deeper understanding of the text, and has been developed through feminist practices.

Materiality - an object being composed of a material and its qualities. It is important to think about where materials are sourced from, and the processes that take place for that material to be where it is today. It is also important to think about what using a particular material in a design means for the human and non-human actants of the space.

The 7 words I picked out were:

Radical

Marginalisation

Historical - to archive

Critique - to critique

Intersectionality

Theory

Contribution - to provide

The drawing that I created represents the 'normal' way of doing something, and how this conflicts with a 'new' way of doing something. This relates to the idea of being radical and having new theories.

0 notes

Text

The Dead Ladies Club

“Ladies die in childbed. No one sings songs about them.”

The Dead Ladies Club is a term I invented** circa 2012 to describe the pantheon of undeveloped female characters in ASOIAF from the generation or so before the story began.

It is a term that carries with it inherent criticisms of ASOIAF, which this post will address, in an essay in nine parts. The first, second, and third parts of this essay define the term in detail. Subsequent sections examine how these women were written and why this aspect of ASOIAF merits criticism, exploring the pervasiveness of the dead mothers trope in fiction, the excessive use of sexual violence in writing these women, and the differences in GRRM’s portrayals of male sacrifice versus female sacrifice in the narrative.

To conclude, I assert that the manner in which these women were written undermines GRRM’s thesis, and ASOIAF -- a series I consider to be one of the greatest works of modern fantasy -- is poorer because of it.

*~*~*~*~

PART I: WHAT IS THE DEAD LADIES CLUB?

Below is a list of women I personally include in the Dead Ladies Club. This list is flexible, but this is generally who people are talking about when they’re talking about the DLC:

Lyanna Stark

Elia Martell

Ashara Dayne

Rhaella Targaryen

Joanna Lannister

Cassana Estermont

Tysha

Lyarra Stark

the Unnamed Princess of Dorne (mother to Doran, Elia, and Oberyn)

Brienne’s Unnamed Mother

Minisa Whent-Tully

Bethany Ryswell-Bolton

EDIT - The Miller’s Wife - GRRM never named her, but she was raped by Roose Bolton and she gave birth to Ramsay

I might be forgetting someone

Most of the DLC are mothers, dead before the series began. I deliberately use the word “pantheon” when describing the DLC because, like the gods of ancient mythology, these women typically loom large over the lives of our current POVs, and it is their deification that is largely the problem. The women of the Dead Ladies Club tend to be either heavily romanticized or heavily villainized by the text, either up on a pedestal or down on their knees, to paraphrase Margaret Attwood. The DLC are written by GRRM as little more than male fantasies and tired tropes, defined almost exclusively by their beauty and desirability (or lack thereof). They have no voices of their own. Too often they are nameless. They are frequently the victims of sexual violence. They are presented with few or no choices in their stories, something I consider to be a particularly egregious oversight when GRRM says it is our choices which define us.

The space in the narrative given over to their humanity and their interiority (their inner lives, their thoughts and feelings, their existence as individuals) is minimal or nonexistent, which is quite a shame in a series that is meant to celebrate our common humanity. How can I have faith in the thesis of ASOIAF, that people’s “lives have meaning, not their deaths,” when GRRM created a coterie of women whose main if not sole purpose was to die?

I restrict the Dead Ladies Club to women one or two generations back because the Lady in question must have some immediate connection to a POV character or a second-tier character. These women tend to be of immediate importance to a POV character (mothers, grandmothers, etc), or at most they’re one character removed from a POV character in the main story (AGOT - ADWD+).

Example #1: Dany (POV) --> Rhaella Targaryen

Example #2: Davos (POV) --> Stannis --> Cassana Estermont

*~*~*~*~

PART II: "NOW SAY HER NAME.”

Lyanna Stark, “beautiful, willful, and dead before her time.” We know little about Lyanna other than how much men desired her. A Helen of Troy type figure, an entire continent of men fought and died because “Rhaegar loved his Lady Lyanna”. He loved her enough to lock her in a tower, where she gave birth and died. But who was she? How did she feel about any of these events? What did she want? What were her hopes, her dreams? On these, GRRM remains silent.

Elia Martell, “kind and clever, with a gentle heart and a sweet wit.” Presented in the narrative as a dead mother, a dead sister, a deficient wife who could bare no more children, she is defined solely by her relationships with various men, with no story of her own outside of her rape and murder.

Ashara Dayne, the maiden in the tower, the mother of a stillborn daughter, the beautiful suicide, we get no details of her personality, only that she was desired by Barristan the Bold and either (or perhaps both) Brandon or Ned Stark.

Rhaella Targaryen, a Queen of the Seven Kingdoms for more than 20 years. We know that Aerys abused and raped her to conceive Daenerys. We know that she suffered many miscarriages. But what do we know about her? What did she think of Aerys’s desire to make the Dornish deserts bloom? What did she spend 20 years doing when she wasn’t being abused? How did she feel when Aerys moved the court to Casterly Rock for almost a year? We don’t have answers to any of these questions. Yandel wrote a whole history book for ASOIAF giving us lots and lots of information on the personalities and quirks and fears and desires of men like Aerys and Tywin and Rhaegar, so I know who these men are in a way that I don’t know the women in canon. I don’t think it’s reasonable that GRRM left Rhaella’s humanity virtually blank when he had all of TWOIAF to elaborate on pre-series characters, and he could have easily made a little sidebar on Queen Rhaella. We have a lot of dairies and letters and stuff about the thoughts and feelings of real medieval queens, so why didn’t Yandel (and GRRM) give us a little more about the last Targaryen queen in the Seven Kingdoms? Why didn’t we even get a picture of Rhaella in TWOIAF?

Joanna Lannister, desired by both a King and a King’s Hand and made to suffer for it, she died giving birth to Tyrion. We know there was “love between” Tywin and Joanna, but details about her are few and far between. With many of these women, the scant lines in the text about them often leave the reader asking, “well, what does that mean exactly?” What does it mean exactly that Lyanna was willful? What does it mean exactly that Rhaella was mindful of her duty? Joanna is no exception, with GRRM’s teasing yet frustratingly vague remark that Joanna “ruled” Tywin at home. Joanna is merely the roughest sketch in the text, seen through a glass darkly.

Cassana Estermont. Honestly I tried to recall a quote about Cassana and I realized that there wasn’t one. She is the drowned lover, the dead wife, the dead mother, and we know nothing else.

Tysha, a teenage girl who was saved from rapers, only to be gang-raped on Tywin Lannister’s orders. Her whereabouts become something of a talisman for Tyrion in ADWD, as if finding her will free him from his dead father’s long, black shadow, but aside from the sexual violence she suffered, we know nothing else about this lowborn girl except that she loved a boy deemed by Westerosi society to be unloveable.

For Lyarra, Minisa, Bethany, and the rest, we know little more than their names, their pregnancies, and their deaths, and for some we don’t even have names.

I often include Lynesse Hightower and Alannys Greyjoy as honorary members, even though they’re obviously not dead.

I said above that the DLC are either up on a pedestal or down on their knees. Lynesse Hightower is both, introduced to us by Jorah as a love story out of the songs, and villainized as the woman who left Jorah to be a concubine in Lys. In Jorah’s words, he hates Lynesse, almost as much as he loves her. Lynesse’s story is defined by a lot of tired tropes; she is the “Stunningly Beautiful” “Uptown Girl” / “Rich Bitch” “Distracted by the Luxury” until she realizes Jorah is “Unable to support a wife”. (All of these are explained on tv tropes if you would like to read more.) Lynesse is basically an embodiment of the gold digger trope without any depth, without any subversion, without really delving into Lynesse as a person. Even though she’s still alive, even though lots of people still alive know her and would be able to tell us about her as a person, they don’t.

Alannys Greyjoy I personally include in the Dead Ladies Club because her character boils down to a “Mother’s Madness” with little else to her, even tho, again, she’s not dead.

When I include Lynesse and Alannys, every region in GRRM’s Seven Kingdoms has at least one of the DLC. That was something that stood out to me when I was first reading - how widespread GRRM’s dead mothers and cast off women are. It’s not just one mother, it’s not just one House, it’s everywhere in GRRM’s writing.

And when I say “everywhere in GRRM’s writing,” I mean everywhere. Mothers killed off-screen (typically in childbirth) before the story begins is a trope GRRM uses throughout his career, in Fevre Dream and Dreamsongs and Armageddon Rag and in his tv scripts. It’s unimaginative and lazy, to say the least.

*~*~*~*~

PART III: WHO ARE THEY NOT?

Long dead, historical women like Visenya Targaryen are not included in the Dead Ladies Club. Why, you ask?

If you go up to the average American on the street, they’ll probably be able to tell you something about their mother, or their grandmother, or their aunt, or some other woman in their lives who is important to them, and you can get an idea about who these women were/are as people. But the average American probably won’t be able to tell you a whole lot about Martha Washington, who lived centuries ago. (If you’re not American, substitute “Martha Washington” with the name of the mother of an important political figure who lived 300 years ago. I’m American, so this is the example I’m using. Also, I can already hear the history nerds piping up - sit down, you’re distinctly above average.)

In this same fashion, the average Westerosi should (misogyny aside) usually be able to tell you something about the important women in their lives. In real life history, kings and lords and other noblemen shared or preserved information about their wives or mothers or sisters or w/e, in spite of the extremely misogynistic medieval societies they lived in.

So this isn’t “OMG a woman died, be outraged!!1!” kind of thing. This isn’t that.

I generally limit the DLC to women who have died relatively recently in Westerosi history and who are denied their humanity in a way that their male contemporaries are not.

*~*~*~*~

PART IV: WHY DOES IT MATTER?

The Dead Ladies Club are the women of the previous one or two generations that we should know more about, but we don’t. We know little more about them than that they had children and they died. I don’t know these women, except through transformative fandom. I know a lot about the pre-series male characters in the text, but canon gives me almost nothing about these women.

To copy from another post of mine on this issue, it’s like the Dead Ladies exist in GRRM’s narrative solely to be abused, raped, give birth, and die, later to have their immutable likenesses cast in stone and put up on pedestals to be idealized. The women of the Dead Ladies Club aren’t afforded the same characterization and growth as pre-series male characters.

Think about Jaime, who, while not a pre-series character, is a great example of how GRRM can use characterization to play with his readers. We start off seeing Jaime as an asshole who pushes kids out of windows, and don’t get me wrong, he’s still an asshole who pushes kids out of windows, but he’s also so much more than that. Our perception as readers shifts and we understand that Jaime is so complex and multi-layered and grey.

With dead pre-series male characters, GRRM still manages to do interesting things with their stories, and to convey their desires, and to play with reader perceptions. Rhaegar is a prime example. Readers go from Robert’s version of the story that Rhaegar was a sadistic supervillain, to the idea that whatever happened between Rhaegar and Lyanna wasn’t as simple as Robert believed, and some fans even progress further to this idea that Rhaegar was highly motivated by prophecy.

But we don’t get that kind of character development with the Dead Ladies. For example, Elia exists in the narrative to be raped and to die, and to motivate Doran’s desires for justice and revenge, a symbol of the Dornish cause, a reminder by the narrative that it is the innocents who suffer most in the game of thrones. But we don’t know who she is as a person. We don’t know what she wanted in life, how she felt, what she dreamed of.

We don’t get characterization of the DLC, we don’t get shifts in perception, we barely get anything at all when it comes to these women. GRRM does not write pre-series female characters the same way he writes pre-series male characters. These women are not given space in the narrative the same way their male contemporaries are.

Consider the Unnamed Princess of Dorne, mother to Doran, Elia, and Oberyn. She was the only female ruler of a kingdom while the Robert’s Rebellion generation was coming up, and she is also the only leader of a Great House during that time period that we don’t have a name for.

The North? Ruled by Rickard Stark. The Riverlands? Ruled by Hoster Tully. The Iron Islands? Ruled by Quellon Greyjoy. The Vale? Ruled by Jon Arryn. The Westerlands? Ruled by Tywin Lannister. The Stormlands? Steffon, and then Robert Baratheon. The Reach? Mace Tyrell. But Dorne? Just some woman with no name, oops, who the hell cares, who even cares, why bother with a name, who needs one, it’s not like names matter in ASOIAF, amirite? //sarcasm//

We didn’t even get her name in TWOIAF, even though the Unnamed Princess was mentioned there. And this lack of a name is so very limiting - it is so hard to discuss a ruler’s policy and evaluate her decisions when the ruler doesn’t even have a name.

To speak more on the namelessness of women... Tysha didn’t get a name until ACOK. Although they were named in the appendices in book 1, neither Joanna nor Rhaella were named within the story until ASOS. Ned Stark’s mother wasn’t named until the family tree in the appendix of TWOIAF. And when will the Unnamed Princess of Dorne get a name? When?

As I think about this, I cannot help but think of this quote: “She hated the namelessness of women in stories, as if they lived and died so that men could have metaphysical insights.” Too often these women exist to further the male characters, in a way that doesn’t apply to men like Rhaegar or Aerys.

I don’t think that GRRM is leaving out or delaying these names on purpose. I don’t think GRRM is doing any of this deliberately. The Dead Ladies Club, imo, is the result of indifference, not malevolence.

But these kinds of oversights like the Princess of Dorne not having a name are, in my opinion, indicative of a much larger trend -- GRRM refuses these dead women space in the narrative while affording significant space to the dead/pre-series male characters. This issue, imo, is relevant to feminist spatial theory, or the ways in which women inhabit or occupy space (or are prevented from doing so). Some feminist scholars argue that even conceptual “places” or “spaces” (like a narrative or a story) have an influence on people’s political power, culture, and social experience. Such a discussion is probably beyond the scope of this post, but basically it’s argued that women/girls are socialized to take up less space than men in their surroundings. So when GRRM refuses narrative space to pre-series women in a way that he does not do to pre-series men, I feel like he is playing into misogynistic tropes and tendencies rather than subverting them.

*~*~*~*~

PART V: THE DEATH OF THE MOTHER

Given that many of the DLC (although not all) were mothers, and that many died in childbirth, I want to examine this phenomenon in more detail, and discuss what it means for the Dead Ladies Club.

Popular culture has a tendency to prioritize fatherhood by marginalizing motherhood. (Look at Disney’s long history of dead or absent mothers, storytelling which is merely a continuation a much older fairytale tradition of the “symbolic annihilation” of the mother figure.) Audiences are socialized to view mothers as “expendable,” while fathers are “irreplaceable”:

This is achieved by not only removing the mother from the narrative and undermining her motherwork, but also by obsessively showing her death, again and again. […] The death of the mother is instead invoked repeatedly as a romantic necessity […] there appears to be a reflex in mainstream popular visual culture to kill off the mother. [x]

For me, the existence of the Dead Ladies Club is perpetuating the tendency to devalue motherhood, and unlike so much else about ASOIAF, it’s not original, it’s not subversive, and it’s not great writing.

Consider Lyarra Stark. In GRRM’s own words, when asked who Ned Stark’s mother was and how she died, he tells us laconically, “Lady Stark. She died.” We know nothing of Lyarra Stark, other than that she married her cousin Rickard, gave birth to four children, and died during or after Benjen’s birth. It’s another example of GRRM’s casual indifference toward and disregard for these women, and it’s very disappointing coming from an author who is otherwise so amazing. If GRRM can imagine a world as rich and varied as Westeros, why is it so often the case that when it comes to the female relatives of his characters, all GRRM can imagine is that they suffer and die?

Now, you might be saying, “dying in childbirth is just something that happens to women, so what’s the big deal?” Sure, women died in childbirth in the Middle Ages at an alarming rate. Let’s assume that Westerosi medicine closely approximates medieval medicine - even if we make that assumption, the rate at which these women are dying in childbirth in Westeros is inordinately high compared to the real Middle Ages, statistically speaking. But here’s the kicker: Westerosi medicine is not medieval. Westerosi medicine is better than medieval medicine. To paraphrase my friend @alamutjones, Westeros has better than medieval medicine, but worse than medieval outcomes when it comes to women. GRRM is putting his finger down on the scales here. And it’s lazy.

Childbirth, by definition, is a very gendered death. And it’s how GRRM defines these women - they gave birth, and they died, and nothing else about them matters to him. (“Lady Stark. She died.”) Sure, there’s some bits of minutia we can gather about these women if we squint. Lyanna was said to be willful, and she had some sort of relationship with Rhaegar Targaryen that the jury is still out on, but her consent was dubious at best. Joanna was happily married, and she was desired by Aerys Targaryen, and she may or may not have been raped. Rhaella was definitely raped to conceive Daenerys, who she died giving birth to.

Why are these women treated in such a gendered manner? Why did so many mothers die in childbirth in ASOIAF? Fathers don’t tend to die gendered deaths in Westeros, so why isn’t the cause of death more varied for women?

And why are so many women in ASOIAF defined by their absence, as black holes, as negative space in the narrative?

The same cannot be said of so many fathers in ASOIAF. Consider Cersei, Jaime, and Tyrion, but whose father is a godlike-figure in their lives, both before and after his death. Even dead, Tywin still rules his children’s lives.

It’s the relationship between child and father (Randyll Tarly, Selwyn Tarth, Rickard Stark, Hoster Tully, etc) that GRRM gives so much weight to relative to the mother’s relationship, with notable exceptions found in Catelyn Stark and Cersei Lannister. (Though with Cersei, I think it could be argued that GRRM isn’t subverting anything -- he’s playing into the dark side of motherhood, and the idea that mothers damage their children with their presence -- which is basically the flip side of the dead mother trope -- but this post is already a ridiculous length and I’m not gonna get into this here.)

*~*~*~*~

PART VI: THE DLC AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE

Despite his claims to historical verisimilitude, GRRM made Westeros more misogynistic than the real Middle Ages. Considering that the details of their sexual violence is the primary information we have about the DLC, why is so much sexual violence necessary?

I discuss this issue in depth in my tag for #rape culture in Westeros, but I think it deserves to be touched on here, at least briefly.

Girls like Tysha are defined by the sexual violence they experienced. We know about Tysha’s gang rape in book 1, but we don’t even learn her name until book 2. So many of the DLC are victims of sexual violence, with little or no attention given to how this violence affected them personally. More attention is given to how the sexual violence affected the men in their lives. With each new sexual harassment Joanna suffered because of Aerys, we know per TWOIAF that Tywin cracked a little more, but how did Joanna feel? We know that Rhaella had been abused to the point that it appeared that a beast had savaged her, and we know that Jaime felt extremely conflicted about this because of his Kingsguard oaths, but how did Rhaella feel, when her abuser was her brother-husband? We know more about the abuse these women suffered than we do about the women themselves. The narrative objectifies rather than humanizes the DLC.

Why did GRRM’s messianic characters have to be conceived through rape? The mother figure being raped and sacrificed for the messiah/hero is an old and tired fantasy trope, and GRRM does it not once, but two (or possibly even three) times. Really, GRRM? Really? GRRM doesn’t need to rely on raped dead mothers as part of his store-bought tragic backstory. GRRM can do better than that, and he should do better. (Further discussion in my tag for #gender in ASOIAF.)

*~*~*~*~

PART VII: MALE SACRIFICE, FEMALE SACRIFICE, AND CHOICE

Now, you might be asking, “It’s normal for male characters to sacrifice themselves, so why can’t women sacrifice themselves for the messiah? Isn’t female sacrifice subversive?”

Male sacrifice and female sacrifice are often not the same in popular culture. To boil it down - men sacrifice, while women are sacrificed.

Women dying in childbirth to give birth to the messiah isn’t the same thing as male characters making some grand last stand with guns blazing to give the Messianic Hero the chance to Do The Thing. The male characters who get to go out guns blazing choose that fate; it’s the end result of their characterization to do so. Think of Syrio Forel. He chooses to sacrifice himself to save one of our protagonists.

But women like Lyanna and Rhaella and Joanna they didn’t get a choice, were afforded no grand moment of existential victory that was the culmination of their characters; they just died. They bled out, they got sick, they were murdered -- they-just-died. There was no grand choice to sacrifice themselves in favor of saving the world, there was no option to refuse the sacrifice, there wasn’t any choice at all.

And that’s key. That’s what lies at the heart of all of GRRM’s stories: choice. As I said here,

“Choice […]. That’s the difference between good and evil, you said. Now it looks like I’m the one got to make a choice” (Fevre Dream). In GRRM’s own words, “That’s something that’s very much in my books: I believe in great characters. We’re all capable of doing great things, and of doing bad things. We have the angels and the demons inside of us, and our lives are a succession of choices.” It’s the the choices that hurt, the choices where good and evil hang in the balance – these are the choices in which “the human heart [is] in conflict with itself,” which GRRM considers to be “the only thing worth writing about”.

Men like Aerys and Rhaegar and Tywin make choices in ASOIAF; women like Rhaella don’t have any choices at all in the narrative.

Does GRRM not find the stories of the Dead Ladies Club worth writing about? Was there no moment in GRRM’s mind when Rhaella or Elia or Ashara felt conflicted in their hearts, no moment they felt their loyalties divided? How did Lynesse feel choosing concubinage? What of Tysha, who loved a Lannister boy, but was gang-raped at the hands of House Lannister? How did she feel?

It would be very different if we were told about the choices that Lyanna and Rhaella and Elia made. (Fandom often speculates about whether, for example, Lyanna chose to go with Rhaegar, but the text remains silent on this issue as of ADWD. GRRM remains silent on these women’s choices.)

It would be different if GRRM explored their hearts in conflict, but we’re not told anything about that. It would be subversive if these women actively chose to sacrifice themselves, but they didn’t.

Dany is probably being set up as a woman who actively chooses to sacrifice herself to save the world, and I think that’s subversive, a valiant and commendable effort on GRRM’s part to tackle this dichotomy between male sacrifice and female sacrifice. But I don’t think it makes up for all of these dead women sacrificed in childbirth with no choice.

*~*~*~*~

PART VIII: CONCLUSIONS