#fdr presidential library

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Can you recommend any active history blogs?

I don't follow all that many blogs, so I'm sure some of my readers can share their recommendations in the replies. Of the blogs that I do follow, here are a few activate sites that regularly update with some great material:

•The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (@richardnixonlibrary)

•The California State Library (@californiastatelibrary)

•The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library (@fdrlibrary)

•Today's Document from the National Archives (@todaysdocument)

•The National Archives (@usnatarchives)

I really wish that the LBJ Library (@lbjlibrary) still updated their Tumblr regularly because they used to post some interesting stuff. The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum (@fordlibrarymuseum) has also been inactive for a few months, but they were one of my favorite things to see on my dashboard when they posted regularly. A few years ago, the National Archives actually started an awesome Tumblr called Our Presidents (@ourpresidents) that was like the mothership for all of the other Presidential Library blogs in the NARA's Presidential Library system. It was a GREAT idea and one of my favorite blogs, but it just stopped posting a couple years ago. I wish they would get that one going again. I think those inactive sites still have their old posts and archives available, so you can still go back and see what we're missing.

Like I said, I'm sure some of my readers have better suggestions than I do about this that they can share in the replies, so what are some of your favorite history blogs?

#History#Presidential History#National Archives and Records Administration#National Archives#NARA#Presidential Libraries#Presidential Library System#History Blogs#Nixon Library#Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum#California State Library#Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library#FDR Library#Today's Document#LBJ Library#Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum#Our Presidents

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know World War II was going on and he probably didn't have the energy to spend on this, but it's a travesty that history doesn't actually have a photograph of FDR wearing this.

I've been reading a lot about President Ford lately, and after seeing some of the photos of what they were wearing in the White House in the mid-70s, this vest wouldn't have been out of place then.

Luella Smith of Inglewood, California sent Franklin Roosevelt this handmade button vest on January 3, 1944. In a letter that accompanied her gift she noted: “I want you to have your picture made in it and a photo sent to me to put on my stand so that I can admire my boy in the White House, I know you are busy but it sure would make me happy."

See more on our website: https://fdr.artifacts.archives.gov/objects/30602/button-vest

#FDR#Franklin D. Roosevelt#Presidents#History#FDR Library#National Archives#NARA#Presidential Libraries

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Eleanor Roosevelt with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, courtesy of the FDR Presidential Library & Museum, via Wikipedia Commons]

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

December 10, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Dec 10, 2024

Today is Human Rights Day, celebrated internationally in honor of the day seventy-six years ago, December 10, 1948, when the United Nations General Assembly announced the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

In 1948 the world was still reeling from the death and destruction of World War II, including the horrors of the Holocaust. The Soviet Union was blockading Berlin, Italy and France were convulsed with communist-backed labor agitation, Greece was in the middle of a civil war, Arabs opposed the new state of Israel, communists and nationalists battled in China, and segregationists in the U.S. were forming their own political party to stop the government from protecting civil rights for Black Americans. In the midst of these dangerous trends, the member countries of the United Nations came together to adopt a landmark document: a common standard of fundamental rights for all human beings.

The United Nations itself was only three years old. Representatives of the 47 countries that made up the Allies in World War II, along with the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, and newly liberated Denmark and Argentina, had formed the United Nations as a key part of an international order based on rules on which nations agreed, rather than the idea that might makes right, which had twice in just over twenty years brought wars that involved the globe.

Part of the mission of the U.N. was “to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small.” In early 1946 the United Nations Economic and Social Council organized a nine-person commission on human rights to construct the mission of a permanent Human Rights Commission. Unlike other U.N. commissions, though, the selection of its members would be based not on their national affiliations but on their personal merit.

President Harry S. Truman had appointed Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of former president Franklin Delano Roosevelt and much beloved defender of human rights in the United States, as a delegate to the United Nations. In turn, U.N. Secretary-General Trygve Lie from Norway put her on the commission to develop a plan for the formal human rights commission. That first commission asked Roosevelt to take the chair.

“[T]he free peoples” and “all of the people liberated from slavery, put in you their confidence and their hope, so that everywhere the authority of these rights, respect of which is the essential condition of the dignity of the person, be respected,” a U.N. official told the commission at its first meeting on April 29, 1946.

The U.N. official noted that the commission must figure out how to define the violation of human rights not only internationally but also within a nation, and must suggest how to protect “the rights of man all over the world.” If a procedure for identifying and addressing violations “had existed a few years ago,” he said, “the human community would have been able to stop those who started the war at the moment when they were still weak and the world catastrophe would have been avoided.”

Drafted over the next two years, the final document began with a preamble explaining that a UDHR was necessary because “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,” and because “disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.” Because “the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,” the preamble said, “human rights should be protected by the rule of law.”

The thirty articles that followed established that “[a]ll human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights…without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status” and regardless “of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs.”

Those rights included freedom from slavery, torture, degrading punishment, arbitrary arrest, exile, and “arbitrary interference with…privacy, family, home or correspondence, [and] attacks upon…honour and reputation.”

They included the right to equality before the law and to a fair trial, the right to travel both within a country and outside of it, the right to marry and to establish a family, and the right to own property.

They included the “right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion,” “freedom of opinion and expression,” peaceful assembly, the right to participate in government either “directly or through freely chosen representatives,” the right of equal access to public service. After all, the UDHR noted, the authority of government rests on the will of the people, “expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage.”

They included the right to choose how and where to work, the right to equal pay for equal work, the right to unionize, and the right to fair pay that ensures “an existence worthy of human dignity.”

They included “the right to a standard of living adequate for…health and well-being…, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond [one’s] control.”

They included the right to free education that develops students fully and strengthens “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Education “shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.”

They included the right to participate in art and science.

They included the right to live in the sort of society in which the rights and freedoms outlined in the UDHR could be realized. And, the document concluded, “Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.”

Although eight countries abstained from the UDHR—South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and six countries from the Soviet bloc—no country voted against it, making the vote unanimous. The declaration was not a treaty and was not legally binding; it was a declaration of principles.

Since then, though, the UDHR has become the foundation of international human rights law. More than eighty international treaties and declarations, along with regional human rights conventions, domestic human rights bills, and constitutional provisions, make up a legally binding system to protect human rights. All of the members of the United Nations have ratified at least one of the major international human rights treaties, and four out of five have ratified four or more.

Indeed, today is the fortieth anniversary of the U.N.’s adoption of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, more commonly known as the United Nations Convention Against Torture (UNCAT), which follows the structure of the UDHR.

The UDHR remains aspirational, but it is a vital part of the rules-based order that restrains leaders from human rights abuses, giving victims a language and a set of principles to condemn mistreatment. Before 1948 that language and those principles were unimaginable.

In a proclamation today, the White House recommitted to “upholding the equal and inalienable rights of all people.” It noted that in the U.S., the Biden administration established “the White House Gender Policy Council to advance the rights and opportunities of women and girls across domestic and foreign policy [and] rejoined the United Nations Human Rights Council to highlight and address pressing human rights concerns.” It has “worked to protect the rights of LGBTQI+ people” and to expand “accessibility for people with disabilities.” Crucially, the administration has also worked to stop the misuse of commercial spyware, which has enabled human rights abuses around the world as authoritarian governments surveil their populations, and to fight back against transnational repression targeting human rights defenders.

At the State Department, Under Secretary of State Uzra Zeya, Assistant Secretary of State Dafna Rand, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken honored eight individuals with the Human Rights Defender Award. The recipients came from Kuwait, Bolivia, the Kyrgyz Republic, Burma, Eswatini, Ghana, Colombia, and Azerbaijan and defend migrant workers, LGBTQ+ individuals, women, democracy.

Their stories underlined both that the fight for human rights is universal and that it requires courage. One recipient’s award was delivered in absentia because he is imprisoned. Another award was posthumous—the recipient was murdered last year.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Human rights#Letters from An American#heather cox richardson#state department#women#UDHR#history#American History#FDR

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Book - Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, from FDR through Clinton

Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington James Kirchick Adult History, 2022, 848 pg history of gay men (and women) within Washington / American government during the Lavender Scare

For decades, the specter of homosexuality haunted Washington. The mere suggestion that a person might be gay destroyed reputations, ended careers, and ruined lives. At the height of the Cold War, fear of homosexuality became intertwined with the growing threat of international communism, leading to a purge of gay men and lesbians from the federal government. In the fevered atmosphere of political Washington, the secret “too loathsome to mention” paradoxically held enormous, terrifying power.

Utilizing thousands of pages of declassified documents, interviews with over one hundred people, and material unearthed from presidential libraries and archives around the country, Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, from FDR through Clinton is a chronicle of American politics like no other.

View On WordPress

#secret city#james kirchick#2020s#800 pg#adult books#history#lgbt nonfiction#lgbtqia#nonfiction#queer books#daily book#lgbt history#gay history

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

What To Do in a Gas Attack : FDR Presidential Library : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

0 notes

Text

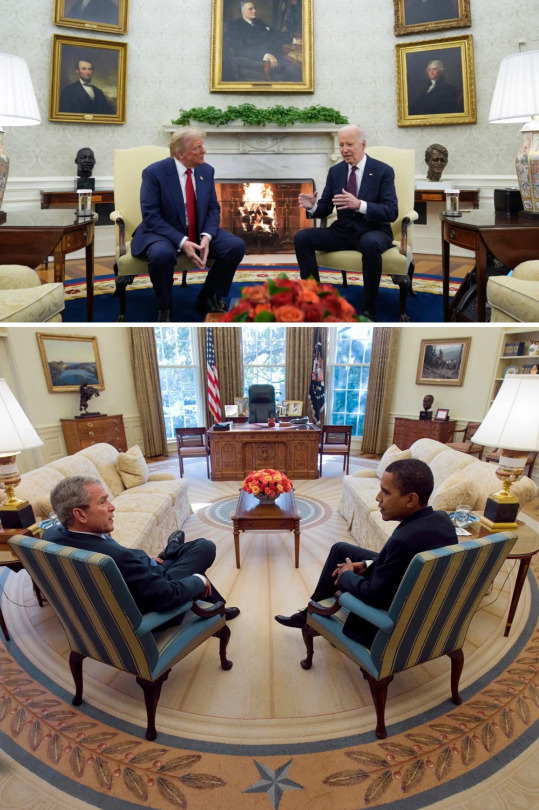

President-elect Donald Trump and War Criminal President Barack Obama shake hands after a meeting in the Oval Office, 10 November 2016. Photograph: Win McNamee/Getty Images

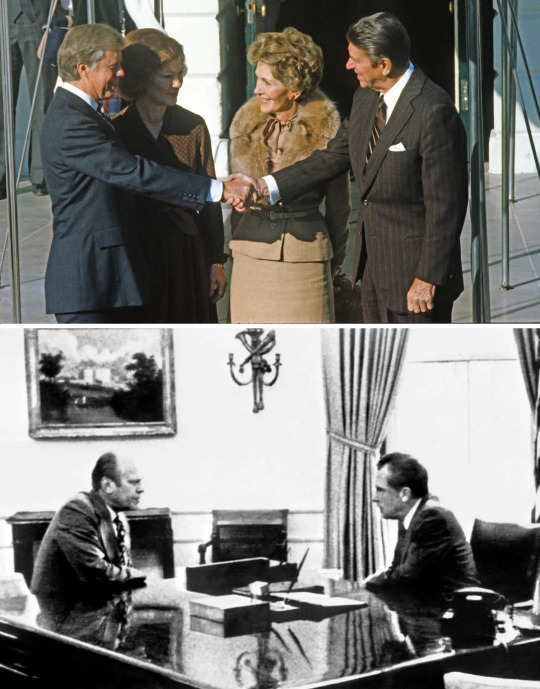

US Presidential Transition Meetings Through The Years – In Pictures

It is Traditional in the US for the Outgoing President to Receive the President-Elect at the White House Before their Inauguration to Prepare for a Smooth Transition. Donald Trump Broke with this Tradition in 2020 in Disputing the Election Result. As Trump meets Joe Biden in 2024, we Take a Look Back at Past Transition Meetings

— Matt Fidler | Wednesday 13 November 2024

Top: The president-elect, Donald Trump, and War Criminal & Genocidal President Joe Biden talking in the Oval Office of the White House, 13 November 2024. Photograph: Evan Vucci/AP

Bottom: Two War Criminals: President George W Bush and President-elect Barack Obama meet in the Oval Office, 10 November 2008. Photograph: Eric Draper/Reuters

President-elect Bill Clinton is greeted by War Criminal President George Bush (Now Resting, Rotting and Burning 🔥 in Hell Forever) at the White House, 18 November 1992. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

President-elect War Criminal President George Bush (Now Resting, Rotting and Burning 🔥 in Hell Forever) and President Ronald Reagan, accompanied by their wives, head for the Oval Office, 9 November 1988. Photograph: Bettmann archive

Top: President Jimmy Carter and President-elect Ronald Reagan shake hands in front of their wives on the White House’s South Portico, 20 November 1980. Photograph: Arnie Sachs/Consolidated News Pictures/Getty Images

Bottom: Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon talk in the Oval Office about the transition of power prior to Nixon’s resignation after the Watergate scandal, 9 August 1974. Photograph: Consolidated News Pictures/AFP/Getty Images

Top: President-elect Richard Nixon and President Lyndon B Johnson confer on the orderly transition of power, 12 December 1968. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

Bottom: President Dwight D Eisenhower greets President-elect John F Kennedy on the North Portico of the White House, 6 December 1960. Photograph: Bettmann archive

Top: Vice-president Harry S Truman and President Franklin D Roosevelt, 1945. When Roosevelt died in office in 1945, Truman took over. Photograph: Universal history archive/Getty Images

Bottom: President-elect Franklin D Roosevelt holds a telegram of congratulations from President Herbert Hoover, 8 November 1932. The transition between Hoover and Roosevelt was not a smooth one, with FDR refusing Hoover’s requests for meetings to calm investors amid a financial crisis. Photograph: Bettmann archive

President Thomas Woodrow Wilson, left, and his successor, President Warren G Harding, in the back of a carriage on inauguration day, 1921. Photograph: Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images

President William Howard Taft (left) and his successor, Thomas Woodrow Wilson, in Washington, 23 March 1913. Photograph: Trampus, from L’Illustrazione Italiana/Bibioteca Ambrosiana/De Agostini/Getty Images

An illustration of the former first lady Julia Dent Grant entertaining President Rutherford B Hayes and his wife at a party in the White House after Hayes’s inauguration, 1877. Photograph: Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images

#US 🇺🇸 News 📰 🗞���#US 🇺🇸 Politics#Miscellaneous Photographs | US Presidents#Gallery#Matt Fidler#US Presidential Transition Meetings#Tradition#Outgoing President#President-Elect#White House#Inauguration#Smooth Transition#Election Result

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

FDR Library_The Herald Statesman_Yonkers, NY 5July1940. Casual mention of first presidential library. Controversial talking points and reading matter !

0 notes

Text

• [W]e have invited battle. We have earned the hatred of entrenched greed. The very nature of the problem that we faced made it necessary to drive some people from power and strictly to regulate others. —Franklin D. Roosevelt

State of the Union – 03 January 1936 FDR Presidential Library & Museum State of the Union – 03 January 1936 Congressional Record January 3, 1936 Vol. 80, Part 1 — Bound Edition State of the Union – 03 January 1936 Congressional Record January 3, 1936 Vol. 80, Part 1 — Bound Edition (at Internet Archive)

1 note

·

View note

Text

'Oppenheimer, the movie about J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project, is a great film, extraordinary, as most movie reviews are accurately saying, and so, so important.

Causing the formation of the Manhattan Project was a letter from Long Island, New York to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was signed by Albert Einstein who spent summers in New Suffolk on Long Island, New York.

It was 1939 and the splitting of the atom—fission—had been done the year before in Germany. The Einstein letter said: “This phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable—though much less certain—that extremely powerful bombs of this type may thus be constructed.”

The aim of the Manhattan Project was to fight fire with fire—to use fission to create an atom bomb before Hitler and the Nazis did.

Einstein in the end regretted the letter. “If I had known that the Germans would not succeed in constructing the atom bomb, I never would have moved a finger,” he wrote in his 1950 book Out of My Later Years.

I first saw the two-page letter as a boy on a family trip to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, next to what was FDR’s home, in upstate Hyde Park. It was there in a glass display cabinet. My sense: what an important letter!

Written on its upper right: “Albert Einstein, Old Grove Road, Nassau Point, Peconic, Long Island, August 2nd, 1939.” Below and to the left was to whom it was addressed: “F.D. Roosevelt, President of the United States, White House, Washington, D.C.”

On a personal note, Nassau Point is seven air miles from where my wife and I have lived for nearly 50 years, a hamlet called Noyac on Long Island’s South Fork, across Little Peconic Bay from New Suffolk.

Oppenheimer takes place largely in Los Alamos, New Mexico where the main work of the World War II crash program was done. Why then was it called the Manhattan Project? Its initial headquarters in 1942 was in Manhattan at the North Atlantic Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. General Leslie Groves, its director, was in the Corps.

The story of how several scientists, like Einstein refugees from the Nazis, found Einstein on the North Fork of eastern Long Island is amazing. It has been told by the late British journalist Alistair Cooke. Cooke gave this account over BBC radio as part of his “Letter from America” series. (Cooke incidentally had a home in Cutchogue on the North Fork.)

“Well, it began, on a drenching hot day in midsummer 1939 with two men, two refugees getting up in the morning and getting out a map and deciding to drive to the end of Long Island,” Cooke related. He said these “these two refugees, both Hungarians who had been run out of their labs in Germany, heard through the underground of their old friends who’d fled to various countries of Europe, two things. One was that there had been a secret meeting of German physicists, in Berlin, and that Germany had, quite suddenly and secretly, forbidden all exports of a certain kind of ore from the occupied country of Czechoslovakia.”

The ”ore” was uranium.

“These two refugees wondered, if the American State Department had any notion what the coincidence of these two items could signify.” But they were concerned that “if they had gone in person to the State Department or the White House they would quite likely have been waved away, or locked up as nuts.”

One of the scientists “remembered the old man, another refugee, but better known.”

This was Einstein.

“He might carry a little weight,” Cooke went on. “That was it, get to the old man, tell him what was meant by the equation: one secret meeting plus one export ban. But where was the old man? Well, one of them had heard that he was down at the end of Long Island, summering in a cottage rented from a local doctor. Doctor... doctor... wait a minute, Moore that was it? But now the place.”

One of the scientists “remembered all this, but couldn’t recall the name of the nearest village,” said Cooke. “Now Long Island is 120 miles long and full of place names. And the English names might be forgettable enough to a couple of Hungarians, but how about the Indian names? Aquebogue and Noyac and Mattituck and Ronkonkoma…and the like.”

One scientist said it was spelled “with a ‘P.’ They saw a name 90 miles down the island on the map in red letters, ‘Patchogue, that's it, that's the one.’ So they drove off. And they got out, and they asked in stores and petrol stations, ‘Anybody know the whereabouts of Doctor Moore's cottage?’ Nobody had ever heard of him. They got into the car again and sweated over the map.” Then still driving they neared a bay—Peconic Bay—and one scientist said: “Could it be Peconic?”

“’That’s it,’ cried the other, ‘now I remember.’”

And they drove on. “Less than two miles from Peconic” they came to Cutchogue and “saw a boy…standing on a corner with a fishing rod in his hand. The old man [Einstein] was a great fisherman. ‘Sure, said the little boy,’ he lives in Doctor Moore’s cottage.’” The boy “climbed” into the scientists’ “car and he led them there. The old man [Einstein] came out in his slippers and they told him their news. And they had a hot hour explaining to him what it all [the splitting of the atom in Germany] meant or could mean.”

There was a second visit, Cooke related, by Leo Szilard, one of the scientists on the first trip, and this time Szilard was with Edward Teller, yet another refugee.

A ”bold and simple letter” had been drafted, noted Cooke. Einstein signed it. “The president got the letter.” And that led to the Manhattan Project.

To listen to the full broadcast, go to https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00fks6t.

In a book I wrote, Cover Up; What You Are Not Supposed to Know About Nuclear Power, published in 1980, I present a facsimile of much of the Einstein letter and discuss it and the Manhattan Project. Through the years since, nuclear technology has been a focus of mine and I’ve written more than a thousand articles and additional books and have been the presenter of many TV programs on the subject.

In 1999 I went to Los Alamos for an event in which the Nuclear Free Future Awards for that year were presented. I had been invited to be a member of a panel of judges for the award given to people involved in education about and also challenging nuclear technology.

The setting of the awards ceremony was right out of the Manhattan Project, literally.

Claus Biegert, head of the Nuclear Free Future Awards program, arranged for it to be held in Fuller Lodge, a main building among the original structures used by the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos. Among those present was Peter Oppenheimer, son of J. Robert Oppenheimer and an opponent of nuclear weapons who warmly welcomed Biegert to Fuller Lodge. There are several scenes in Oppenheimer filmed in the Fuller Lodge.

I stayed at a motel in Los Alamos a few blocks aways—a motel the halls of which were lined with photographs of nuclear bombs exploding with their mushroom clouds.

The morning after the ceremony, I had breakfast at the motel at a table with Arlo Guthrie, involved in the awards program and long a musical advocate of peace. And here we were in a building glorifying nuclear bombs. But glorification of nuclear weapons has been and is still going on especially in places like Los Alamos that are involved in their production, thus having a vested interest

Not only did Einstein regret his signing the letter—he called it, too, “one great mistake in my life”—but Szilard was also left with deep concerns about a future in which nuclear weapons would proliferate.

Szilard in 1945 put together a petition to President Truman signed by 70 other Manhattan Project scientist asking the president not to use the atomic bomb on Japan without first giving Japan the opportunity to surrender and further declaring: “The development of atomic power will provide the nations with new means of destruction. The atomic bombs at our disposal represent only the first step in this direction, and there is almost no limit to the destructive power which will become available…”

Truman never saw the letter before the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with accounts saying its delivery to him was blocked by Groves and Secretary of State James Byrnes.

Meanwhile, Teller then and through his life believed nuclear war was feasible and winnable. He led the development of an even more powerful nuclear weapon than the atomic bomb—what he called the “super,” the hydrogen bomb. His conflict with Oppenheimer over this is repeated throughout the Oppenheimer film.

I had a run-in with Teller in requesting the use in Cover Up of passages from one of his books that claimed “we can survive” nuclear war. I was told no. I quoted from it anyway.

Go see the brilliant Oppenheimer film.

Can the nuclear weapons genie be put back in the bottle? Chemical weapons were outlawed—put back in the bottle—through a set of international treaties after World War I in which their terrible consequences were demonstrated. The vehicle today for eliminating nuclear weapons is the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, passed at the United Nations by a vote of 122 nations in 2017. It is now backed by two-thirds of the world’s nations and is international law.

The treaty bans the use, development, testing and production of nuclear weapons and also prohibits threats to use them. However, the nine countries that now possess nuclear weapons—which include the U.S., Russia and China—are not supporting the treaty.'

#Oppenheimer#The Manhattan Project#Albert Einstein#Cover Up; What You Are Not Supposed to Know About Nuclear Power#Leslie Groves#Peter Oppenheimer#Fuller Lodge#Los Alamos#President Truman#Edward Teller

0 notes

Text

Quercus pacis

Late October 1955 Eleanor Roosevelt was flying from Columbus to Chicago in route to Burlington, Iowa. As she recounted in her syndicated column My Days—“We flew rather low and were able to see the wonderful Ohio farming country. How wise they have been everywhere to keep their wood lots on every farm—and along the rivers and along the roads, too, there seemed to be rows of trees everywhere. It is flat land and from the air it looks like good land.”

The wisdom she saw below perhaps carried with it memories of the recklessness culminating two decades before over farmlands west of Ohio, where neither tree nor grass was left to hold the earth to the ground so that instead earth became air and this air became brutal as it blew over, through and into everything it crossed. “Field Are ROBBED of Fertility by MISUSE” a poster shouted from the depths of a Dust Bowl fissure, desiccated roots hanging overhead like stitches ripped out prematurely.

But Eleanor, FDR and thousands of farmers saw that crisis through, aided as much by payments and policy as by plants, especially the millions and millions (and millions) of trees planted for the Great Plains Shelterbelt. In time the earth settled, and it could be called “good land” again. The threat to this goodness in 1955 was not so much aridity and erosion as it was atomic. Roosevelt’s travels in late October were in sponsorship of the United Nations— celebrating its tenth anniversary that month. Trees were to play a part in spreading the peace this organization was hoped to ensure across and between lands. In her U.N. Day column, Roosevelt quoted Senator Arthur Vandenberg:

"The United Nations is our only chance to keep faith with those who have borne the heat of battle. You cannot plant an acorn and expect an oak unless you plant the acorn. In the charter, we undertake to plant the roots of peace. No one can say with finality how they will flower, but I know without roots there will be no flowers. I prefer the chance rather than no chance at all."[1]

These metaphorical oaks were becoming material ones outside the furrows and grounds of texts, as elsewhere on UN Day trees were being planted across the country in big northern towns like Bridgeport, Connecticut and, apparently, very small southern towns like Scotland Neck, North Carolina. The two planted here are water oaks (Quercus nigra). Were they chosen specifically for their acorn-to-tree symbolism, or because they grow so well in coastal plains? Whatever number of these UN trees were planted nationally, certainly it was far below the number planted in Shelterbelt, but even so I suppose the hope was (is?) that together their boughs would provide a windbreak against the gales of war, strife and ignorance which so often perpetuate each other at the expense of peace.

The words on the stone tablet are still as legible as the water oaks are still lush and live, yet I wonder how viable the meaning of either of them remains— is an oak still a promise of the grander of growth, is an intergovernmental organization still a prospect for peace? Or perhaps the insensitivity to plants called “plant blindness”[2] is not unrelated to an insensitivity to peace (local, regional, or global); neither seem much noticed until they are cut down—the task is to make both sensible before that occurs. I can’t say with finality if this is truly possible, but I’ll take my chance in trying to do so rather than take no chance at all.[3]

[1] Eleanor Roosevelt, "My Day, October 24, 1955," The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Digital Edition (2017), accessed at: https://www2.gwu.edu/~erpapers/myday/displaydoc.cfm?_y=1955&_f=md003311.

[2] Though effective as a term, it might be more sensitive to call it plant insensitivity, for vision is not the only means to engage plants and not all have vision to sense plants.

[3] Images:

Fields Are Robbed of Fertility by Misuse. 1935. Richard H. Jasen, poster on wove paper. FDR Presidential Library.

Plains farms need trees Trees. 1940c. Joseph Dusek, silkscreen poster. Library of Congress.

0 notes

Note

At the FDR Presidential Library, I read that the British press considered it crass and undignified for the Roosevelts to share hotdogs with the King and Queen of England when they visited Hyde Park. Are there any other fun anecdotes about Presidents serving the wrong food to dignitaries?

FDR also served them beer with their hot dogs! From the accounts that I've read, King George VI enjoyed them and asked for more. Queen Elizabeth (that's the Queen Mother -- Elizabeth II's mom) had to ask for directions about how to eat the hot dogs, but apparently ended up using a knife and fork. Apparently, the King and Queen really appreciated the lack of formality in their visit to Hyde Park because it came on the heels of a very formal, month-long state visit to Canada. President Roosevelt and King George even went swimming together a couple of times in FDR's pool and went for a ride in FDR's custom-made car that allowed him to control everything with his hands due to his disability.

Off the top of my head, I can't think of any incidents where Presidents served the wrong type of food to guests. I'm sure it has probably happened over the years, but State Dinners are pretty meticulously planned by protocol officials on both ends. One story that I always liked was President Reagan noting in a diary entry that Prince Charles (now King Charles III) was served tea during a visit to Washington but had absolutely no idea what to do with it because it was served with a tea bag.

From Reagan's diary entry on May 1, 1981:

"Highlight was noon visit by Prince Charles. He's a most likeable person. The ushers brought him tea -- horror of horrors they served it our way with a tea bag in the cup. It finally dawned on me that he was just holding the cup & then finally put it down on a table. I didn't know what to do. Mike [Deaver] escorted him back to the W.H. and apologized. The Prince [said], 'I didn't know what to do with it.'"

#History#Presidents#Presidential History#Franklin D. Roosevelt#FDR#State Dinners#Presidential Protocol#King George VI#Prince Charles#King Charles III#Ronald Reagan#President Reagan

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yeah, but how did he do in the 1937 competition?

This #LeapDay be sure to get in your practice for the running high kick! FDR placed first in this Groton School competition in 1897.

#Oops...I did it again#Too soon?#FDR was a great President and doesn't deserve my inappropriate jokes#Also...I love the FDR Library and they have the best Tumblr of any Presidential Library

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Eleanor Roosevelt with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, courtesy of the FDR Presidential Library & Museum, via Wikipedia Commons]

* * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

December 10, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

Seventy-five years ago today, on December 10, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly announced the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

At a time when the world was still reeling from the death and destruction of World War II, the Soviet Union was blockading Berlin, Italy and France were convulsed with communist-backed labor agitation, Arabs opposed the new state of Israel, communists and nationalists battled in China, and segregationists in the U.S. were forming their own political party to stop the government from protecting civil rights for Black Americans, the member countries of the United Nations nonetheless came together to adopt a landmark document: a common standard of fundamental rights for all human beings.

The United Nations itself was only three years old, having been formed in 1945 as a key part of an international order based on rules on which nations agreed, rather than the idea that might makes right, which had twice in just over twenty years brought wars that involved the globe. In early 1946 the United Nations Economic and Social Council organized a nine-person commission on human rights to set up the mission of a permanent Human Rights Commission. Unlike other U.N. commissions, though, the selection of its members would be based not on their national affiliations but on their personal merit.

President Harry S. Truman had appointed Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of former president Franklin Delano Roosevelt and much beloved defender of human rights in the United States, as a delegate to the United Nations. In turn, U.N. Secretary-General Trygve Lie from Norway put her on the commission to develop a plan for the formal human rights commission. That first commission, in turn, asked Roosevelt to take the chair.

“[T]he free peoples” and “all of the people liberated from slavery, put in you their confidence and their hope, so that everywhere the authority of these rights, respect of which is the essential condition of the dignity of the person, be respected,” a U.N. official told the commission at its first meeting on April 29, 1946. Their work would establish the United Nations as a centerpiece of the postwar rules-based international order.

The U.N. official noted that the commission must figure out how to define the violation of human rights not only internationally but also within a nation, and must suggest how to protect “the rights of man all over the world.” If a procedure for identifying and addressing violations “had existed a few years ago,” he said, “the human community would have been able to stop those who started the war at the moment when they were still weak and the world catastrophe would have been avoided.”

Drafted over the next two years, the final document began with a preamble explaining that a UDHR was necessary because “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,” and because “disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.” Because “the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,” the preamble said, “human rights should be protected by the rule of law.”

The thirty articles that followed established that “[a]ll human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights…without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status” and regardless “of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs.”

Those rights included freedom from slavery, torture, degrading punishment, arbitrary arrest, exile, and “arbitrary interference with…privacy, family, home or correspondence, [and] attacks upon…honour and reputation.”

They included the right to equality before the law and to a fair trial, the right to travel both within a country and outside of it, the right to marry and to establish a family, the right to own property.

They included the “right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion,” “freedom of opinion and expression,” peaceful assembly, the right to participate in government, either “directly or through freely chosen representatives,” the right of equal access to public service. After all, the UDHR noted, the authority of government rests on the will of the people, “expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage.”

They included the right to choose how and where to work, the right to equal pay for equal work, the right to unionize, and the right to fair pay that ensures “an existence worthy of human dignity.”

They included “the right to a standard of living adequate for…health and well-being…, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond [one’s] control.”

They included the right to free education that develops students fully and strengthens “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Education “shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.”

They included the right to participate in art and science.

They included the right to live in the sort of society in which the rights and freedoms outlined in the UDHR could be realized. And, the document concluded, “Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.”

Although eight countries abstained from the UDHR—six countries from the Soviet bloc, South Africa, and Saudi Arabia—no country voted against it, making the vote unanimous. The declaration was not a treaty and was not legally binding; it was a declaration of principles.

Since then, though, the UDHR has become the foundation of international human rights law. More than eighty international treaties and declarations, along with regional human rights conventions, domestic human rights bills, and constitutional provisions, make up a legally binding system to protect human rights. All of the members of the United Nations have ratified at least one of the major international human rights treaties, and four out of five have ratified four or more.

The UDHR is a vital part of the rules-based order that restrains leaders from human rights abuses, giving victims a language and a set of principles to condemn mistreatment, language and principles that were unimaginable before 1948.

But the UDHR remains aspirational. “As we look at the first 75 years of the UDHR,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said today, “we recognize what we’ve accomplished in this time, but also know that much work remains. Too often, authorities fail to protect or—worse—trample on human rights and fundamental freedoms, often in the name of security or to maintain their grip on power. Whether arresting and wrongfully detaining journalists and dissidents, restricting an individual’s freedom of religion or belief, or committing atrocities and acts of genocide, violations and abuses of human rights undermine progress made in support of the UDHR. In the face of these actions, we must press for greater human rights protection and promote accountability whenever we see violations or abuses of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

“On its 75th anniversary, the UDHR must continue to be our guiding light as we strive to create the world in which we want to live. Its message is as importa

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#United Nations#UDHR#Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)#history#human rights#Eleanor Roosevelt

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

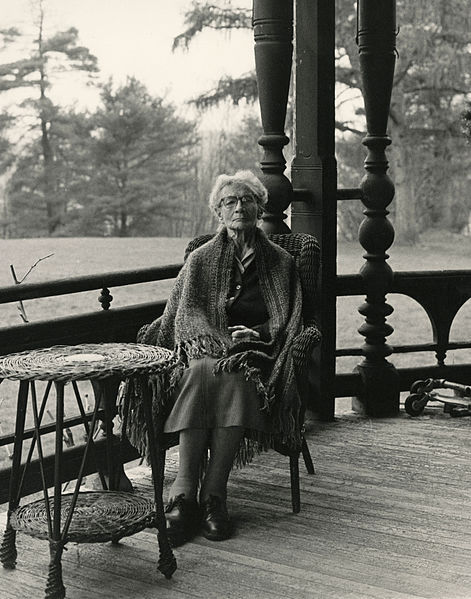

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley

President Roosevelt himself took this photograph of Daisy Suckley in the White House as she went through various papers, February 10, 1942. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

This post was written by Keith Muchowski, an Instruction/Reference Librarian at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) in Brooklyn, New York. He blogs at thestrawfoot.com.

Margaret Suckley was an archivist at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York from 1941 to 1963. But she was much more than that.

“Daisy” Suckley, as she was known to friends and family, was born in Rhinebeck, New York in 1891 and grew up on Wilderstein, the family estate on the Hudson River not far from the Roosevelts’ own Springwood in Hyde Park. This was a small, rarefied world and in the ensuing decades Daisy saw sixth cousin Franklin’s rise to prominence. She eventually became one of his closest friends and confidants, sharing the good times and the bad with the country’s only four-term president. Ms. Suckley was there for Franklin in the 1920s when he was struck paralyzed from the waist down with polio, knew him during his years in Albany when he was New York governor and he became a national figure, attended the presidential inaugural in 1933 in the depths of the Great Depression, offered a discreet and comforting ear during the dark days of the Second World War when, as commander-in-chief, he made difficult and lonely decisions affecting the lives of millions around the world. Finally, Daisy was one of the inner circle present in Warm Springs, Georgia when the president died in April 1945. Roosevelt was inscrutable to most—some called him The Sphinx—but if anyone outside his immediate family knew him, it was Margaret “Daisy” Suckley.

Ms. Suckley (left) in Roosevelt's private office at the presidential library with actress Evelyn Keyes, and Library Director Fred Shipman. Ms. Keyes is holding the album-version of Ms. Suckley's book The True Story of Fala, October 31, 1946. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

There were perks to being Roosevelt’s close friend. The two enjoyed picnics and country drives. Both loved to dish the gossip about Washington politicos and the Hudson River Valley families they had known for decades. Daisy helped President Roosevelt design his Hyde Park retreat, Top Cottage. She enjoyed the “Children’s Hour” afternoon breaks when Roosevelt would mix cocktails for himself and his friends to unwind. There were getaways at Shangri-La, the rustic presidential retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains known today as Camp David. She attended services at Hyde Park Church with the First Family, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth when the royals visited in 1939. It was she who gave him Fala, the Scottish Terrier to whom he was so attached after receiving the pooch as a Christmas gift in 1941.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood at a podium on the grounds of his family home in Hyde Park and dedicated the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library on June 30, 1941. He was still in office at the time, having won re-election to an unprecedented third (and eventually fourth) term seven months previously. Roosevelt clearly believed that libraries and archives were themselves exercises in democracy in these years when fascism was spreading around the world. Ever the optimist even as World War Two raged in Europe and the Pacific, Roosevelt declared “It seems to me that the dedication of a library is in itself an act of faith. To bring together the records of the past and to house them in buildings where they will be preserved for the use of men and women in the future, a Nation must believe in three things. It must believe in the past. It must believe in the future. It must, above all, believe in the capacity of its own people so to learn from the past that they can gain in judgment in creating their own future.” Then he quipped to the two thousand gathered about this being their one chance to see the place for free.

Roosevelt had been an unrepentant collector since his earliest boyhood days, with wide-ranging interests especially in naval history, models ships, taxidermy, philately, books on local history, political ephemera, and—probably above all—anything related to the Roosevelt clan itself. His eight-years-and-counting administration had already produced reams of material via the myriad alphabet soup New Deal agencies that had put millions of Americans to work during the Great Depression. It was becoming increasingly obvious in that Summer of 1941 that the United States would likely become entangled in the Second World War; as Roosevelt well understood, that would mean even more documents for the historical record.

Presidential repositories of various incarnations were not entirely new. George Washington had taken his papers with him back to Mount Vernon after his administration for organization. Rutherford B. Hayes, Herbert Hoover, and even Warren G. Harding had versions of them. Nora E. Cordingley (featured in a March 2018 Women of Library History post) was a librarian at Roosevelt House, essentially a de facto presidential library opened in 1923 at Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace on Manhattan’s East 20th Street whose papers and other materials eventually moved to Harvard University’s Houghton and Widener Libraries. What was new about Franklin Roosevelt’s creation was its codification of what is today’s presidential library system. Roosevelt convened a committee of professional historians for advice and consultation, raised the private funds necessary to build the library and museum, urged Congress to pass the enabling legislation, involved leading archive and library authorities, and ultimately deeded the site to the American people via the National Archives, which itself he had signed into being in 1934.

The academic advisors, archivists, and library professionals at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library were all important, indeed crucial, to the professionalization and growth of both the Roosevelt site and what would become the National Archives and Records Administration’s Office of Presidential Libraries. However, Roosevelt understood in those early that he also needed someone within his museum and library who knew him deeply and understood the nuances of his life and long career. That is why he turned to Ms. Suckley, securing her a position as junior archivist in September 1941 just months after the opening. The library was very much a working place for the president, who kept an office there, where—unbeknownst to museum-goers on the other side of the wall—he might be going through papers with Daisy, entertaining dignitaries while she looked on, or even making decisions of consequence to the war. Ms. Suckley worked conscientiously, even lovingly, in the presidential library, going through boxes of photographs and identifying individuals, providing dates and place names that only she would know, filling in gaps in the historical record, sorting papers, and serving in ways only an intimate could. The work only expanded after President Roosevelt died and associates like Felix Frankfurter and others donated all or some of their own papers. The work also became more institutionalized and codified. Other Roosevelt aides took on increasingly important roles after the president’s death in 1945. More series of papers became available to scholars in the 1950s and 60s as the Roosevelt Era receded from current events into history. Through it all Daisy Suckley continued on for nearly two more decades until her retirement in 1963.

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley lived for twenty-eight more years after her retirement, turning her attention to the preservation of her ancestral home there on the Hudson but never forgetting Franklin. In those later years when reporters, historians, and the just plain curious curious showed up at Wilderstein and inevitably asked if there was any more to tell about her friendship with Franklin Roosevelt she always gave a wry smile and demure “No, of course there isn’t.” After her death at the age of ninety-nine in June 1991 however a trove of letters and diaries was found in an old suitcase hidden under her bed there at Wilderstein. A leading Roosevelt scholar edited and published a significant portion of the journals and correspondence in 1995 to great public interest. While it is still unclear if there was every any romantic involvement between Franklin and Daisy—as some have speculated for decades—the letters do provide a deeper, more nuanced portrayal of their relationship and show just how close the two were. Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have been The Sphinx to many, hiding his feelings behind a veneer of affability and bonhomie. To his old neighbor, distant cousin, discreet friend, loyal aid, and steadfast curator Margaret Suckley, he showed the truer, more vulnerable side of himself.

Ms. Suckley later in life at Wilderstein, 1988. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

Further reading:

Hufbauer, Benjamin. “The Roosevelt Presidential Library: A Shift in Commemoration.” American Studies, vol. 42, no. 3, Fall 2001, pp. 173–193.

Koch, Cynthia M. and Lynn A. Bassanese. “Roosevelt and His Library, Parts 1 & 2.” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 2001, Web.

McCoy, Donald R. "The Beginnings of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library," Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives, vol. 7, no. 3, Fall 1975, pp. 137-150.

Persico, Joseph E. Franklin & Lucy: President Roosevelt, Mrs. Rutherford, and the Other Remarkable Women in His Life. Random House, 2008.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Closest Companion: The Unknown Story of the Intimate Friendship between Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Suckley. Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

#women's history#library history#tumblarians#daisy suckley#fdr#margaret suckley#archivists#presidential collections#new york history#fdr presidential library#women of library history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

No One Used To Care About The Vice Presidency. Here's How (And Why) That's Changed.

The Second-In-Command Position Used To Be "Insignificant" But Can't Be Ignored Today

— September 13, 2024 | Kirstin Butler

Two War Criminals Still At Large: President George Walker Bush and Vice President Richard Bruce (Dickhead) Cheney in the presidential limousine, August 13, 2002. National Archives.

The vice presidency used to look dramatically different than it does today. Largely, this is because of how little definition the Founding Fathers gave to the role in the first place. “The framers of the Constitution thought very little of the vice presidency,” says Jared Cohen, author of The Accidental Presidents. “They thought even less about succession. And I think that's fascinating because people didn't live that long back then, and succession should have been a fundamental feature of how they were thinking about democracy.”

Officially, the Constitution assigned the vice president only two jobs. The first was serving as presiding officer of the Senate, where the VP has the power to cast tie-breaking votes. The second was to assume the president’s duties in the event of disability, death, or resignation. In fact, vice presidents originally had so few formal responsibilities that a member of the first U.S. Congress thought they should be compensated on a per diem basis. As a result, most early vice presidents found themselves at loose ends.

The country’s first vice president, John Adams, had a view of the role’s limits from the very birth of the republic. Referring to himself as “a mere Doge of Venice,” Adams called the position “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived.” It wasn’t until the 20th century that the role began to turn into something more.

Warren Gamaliel Harding, left, and John Calvin Coolidge Jr., right, first photographed together as Republican party nominees for the presidency and vice presidency, June 30, 1920. Library of Congress.

Warren Harding was the first president to invite his vice, Calvin Coolidge, to attend Cabinet meetings; Franklin Delano Roosevelt continued the practice with all three of his vice presidents. Nonetheless, Roosevelt’s last VP, Harry Truman, felt completely unprepared to assume the presidency when FDR died. Truman had been kept so ignorant of critical policy issues that he was only informed about the Manhattan Project upon taking the chief executive office.

“In Truman's 82 days as vice president, he didn't get a single intelligence briefing,” Cohen tells American Experience. “He'd only met FDR twice. He never stepped foot in the map room where the war was being planned. He was not briefed on the atomic bomb. He was completely out of the loop.” Once himself President, however, Truman set out to rectify the role he’d stepped into. He had Congress add the vice president to the National Security Council, while also elevating the office with a higher salary.

President Dwight David Eisenhower and Vice President Richard Milhous Nixon pose for photographers on the reviewing stand for the inaugural parade, January 20, 1953. National Archives.

Having witnessed Truman’s difficulties, next-in-line Dwight Eisenhower also wanted to make sure his potential successor was intimately involved in the ins and outs of domestic and foreign policy. Vice President Richard Nixon was invited to attend briefings alongside President Eisenhower, met with dozens of foreign leaders on his behalf, and worked on important Civil Rights legislation.

But the most significant shift in vice presidential status came when Walter Mondale assumed the office. President Jimmy Carter treated his VP as a full partner, giving him unprecedented equal access to classified materials and meeting sometimes for hours daily to discuss important developments. Mondale was also given symbolic evidence of the role’s increased importance: a permanent office in the White House, for the first time ever.

Vice President Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale and President James Earl Carter Jr. (Jimmy Carter) on their way to meet about the Iran Hostage Crisis at Camp David, Maryland. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

The Carter-Mondale model became a template for how future presidents and vice presidents worked together going forward. And while every governing partnership is different, vice presidents in the modern era have often served as confidants, advisors, and diplomats of policy—finally transforming the vice presidency into an office of greater stature.

William Jefferson Clinton (Bill Clinton) and Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (Al Gore) watch the results of the congressional vote over the North American Free Trade Agreement, November 17, 1993. Bob McNeeley, National Archives.

0 notes