A Women's History Month project of the Feminist Task Force of the American Library Association

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Link

In honor of her five decades of service to Jersey City, the city's library was renamed the Priscilla Gardner Main Library at a ceremony Tuesday.

"What I am beyond grateful the mayor has chosen to recognize me, I simply worked to serve as the best library director for our community and never imagined being recognized in this way," Gardner said. "It is my hope that the work I started lives on, and the Jersey City community continues to have endless access to free resources through the Jersey City Free Public Library."

Another link from AL Direct (9/17/19)

#tumblarians#women's history#library history#jersey city#priscilla gardner#priscilla gardner main library#jersey city free public library#public librarians#library directors#new jersey#new jersey history#women of library history#women's history wednesday

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Resolution on Renaming the Melvil Dewey Medal” passes in ALA Council

ALA has not issued a press release about this (yet?), but it appears briefly in the American Libraries coverage of the Council meeting.

CD #50, “Resolution on Renaming the Melvil Dewey Medal,” which came out of work done by the Feminist Task Force, has passed.

Folks working on the resolution have also compiled a selected bibliography of primary and secondary sources discussing Dewey’s anti-Semitism, racist exclusion, and ongoing sexual misconduct.

“A ‘Private’ Grievance against Dewey,” found in American Libraries over twenty years ago (Jan 1996, Vol. 27 Issue 1, p62-64), by WoLH profile subject Clare Beck, is among the sources listed.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley

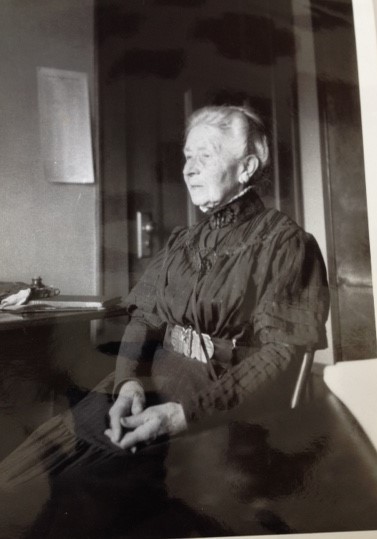

President Roosevelt himself took this photograph of Daisy Suckley in the White House as she went through various papers, February 10, 1942. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

This post was written by Keith Muchowski, an Instruction/Reference Librarian at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) in Brooklyn, New York. He blogs at thestrawfoot.com.

Margaret Suckley was an archivist at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York from 1941 to 1963. But she was much more than that.

“Daisy” Suckley, as she was known to friends and family, was born in Rhinebeck, New York in 1891 and grew up on Wilderstein, the family estate on the Hudson River not far from the Roosevelts’ own Springwood in Hyde Park. This was a small, rarefied world and in the ensuing decades Daisy saw sixth cousin Franklin’s rise to prominence. She eventually became one of his closest friends and confidants, sharing the good times and the bad with the country’s only four-term president. Ms. Suckley was there for Franklin in the 1920s when he was struck paralyzed from the waist down with polio, knew him during his years in Albany when he was New York governor and he became a national figure, attended the presidential inaugural in 1933 in the depths of the Great Depression, offered a discreet and comforting ear during the dark days of the Second World War when, as commander-in-chief, he made difficult and lonely decisions affecting the lives of millions around the world. Finally, Daisy was one of the inner circle present in Warm Springs, Georgia when the president died in April 1945. Roosevelt was inscrutable to most—some called him The Sphinx—but if anyone outside his immediate family knew him, it was Margaret “Daisy” Suckley.

Ms. Suckley (left) in Roosevelt's private office at the presidential library with actress Evelyn Keyes, and Library Director Fred Shipman. Ms. Keyes is holding the album-version of Ms. Suckley's book The True Story of Fala, October 31, 1946. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

There were perks to being Roosevelt’s close friend. The two enjoyed picnics and country drives. Both loved to dish the gossip about Washington politicos and the Hudson River Valley families they had known for decades. Daisy helped President Roosevelt design his Hyde Park retreat, Top Cottage. She enjoyed the “Children’s Hour” afternoon breaks when Roosevelt would mix cocktails for himself and his friends to unwind. There were getaways at Shangri-La, the rustic presidential retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains known today as Camp David. She attended services at Hyde Park Church with the First Family, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth when the royals visited in 1939. It was she who gave him Fala, the Scottish Terrier to whom he was so attached after receiving the pooch as a Christmas gift in 1941.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood at a podium on the grounds of his family home in Hyde Park and dedicated the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library on June 30, 1941. He was still in office at the time, having won re-election to an unprecedented third (and eventually fourth) term seven months previously. Roosevelt clearly believed that libraries and archives were themselves exercises in democracy in these years when fascism was spreading around the world. Ever the optimist even as World War Two raged in Europe and the Pacific, Roosevelt declared “It seems to me that the dedication of a library is in itself an act of faith. To bring together the records of the past and to house them in buildings where they will be preserved for the use of men and women in the future, a Nation must believe in three things. It must believe in the past. It must believe in the future. It must, above all, believe in the capacity of its own people so to learn from the past that they can gain in judgment in creating their own future.” Then he quipped to the two thousand gathered about this being their one chance to see the place for free.

Roosevelt had been an unrepentant collector since his earliest boyhood days, with wide-ranging interests especially in naval history, models ships, taxidermy, philately, books on local history, political ephemera, and—probably above all—anything related to the Roosevelt clan itself. His eight-years-and-counting administration had already produced reams of material via the myriad alphabet soup New Deal agencies that had put millions of Americans to work during the Great Depression. It was becoming increasingly obvious in that Summer of 1941 that the United States would likely become entangled in the Second World War; as Roosevelt well understood, that would mean even more documents for the historical record.

Presidential repositories of various incarnations were not entirely new. George Washington had taken his papers with him back to Mount Vernon after his administration for organization. Rutherford B. Hayes, Herbert Hoover, and even Warren G. Harding had versions of them. Nora E. Cordingley (featured in a March 2018 Women of Library History post) was a librarian at Roosevelt House, essentially a de facto presidential library opened in 1923 at Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace on Manhattan’s East 20th Street whose papers and other materials eventually moved to Harvard University’s Houghton and Widener Libraries. What was new about Franklin Roosevelt’s creation was its codification of what is today’s presidential library system. Roosevelt convened a committee of professional historians for advice and consultation, raised the private funds necessary to build the library and museum, urged Congress to pass the enabling legislation, involved leading archive and library authorities, and ultimately deeded the site to the American people via the National Archives, which itself he had signed into being in 1934.

The academic advisors, archivists, and library professionals at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library were all important, indeed crucial, to the professionalization and growth of both the Roosevelt site and what would become the National Archives and Records Administration’s Office of Presidential Libraries. However, Roosevelt understood in those early that he also needed someone within his museum and library who knew him deeply and understood the nuances of his life and long career. That is why he turned to Ms. Suckley, securing her a position as junior archivist in September 1941 just months after the opening. The library was very much a working place for the president, who kept an office there, where—unbeknownst to museum-goers on the other side of the wall—he might be going through papers with Daisy, entertaining dignitaries while she looked on, or even making decisions of consequence to the war. Ms. Suckley worked conscientiously, even lovingly, in the presidential library, going through boxes of photographs and identifying individuals, providing dates and place names that only she would know, filling in gaps in the historical record, sorting papers, and serving in ways only an intimate could. The work only expanded after President Roosevelt died and associates like Felix Frankfurter and others donated all or some of their own papers. The work also became more institutionalized and codified. Other Roosevelt aides took on increasingly important roles after the president’s death in 1945. More series of papers became available to scholars in the 1950s and 60s as the Roosevelt Era receded from current events into history. Through it all Daisy Suckley continued on for nearly two more decades until her retirement in 1963.

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley lived for twenty-eight more years after her retirement, turning her attention to the preservation of her ancestral home there on the Hudson but never forgetting Franklin. In those later years when reporters, historians, and the just plain curious curious showed up at Wilderstein and inevitably asked if there was any more to tell about her friendship with Franklin Roosevelt she always gave a wry smile and demure “No, of course there isn��t.” After her death at the age of ninety-nine in June 1991 however a trove of letters and diaries was found in an old suitcase hidden under her bed there at Wilderstein. A leading Roosevelt scholar edited and published a significant portion of the journals and correspondence in 1995 to great public interest. While it is still unclear if there was every any romantic involvement between Franklin and Daisy—as some have speculated for decades—the letters do provide a deeper, more nuanced portrayal of their relationship and show just how close the two were. Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have been The Sphinx to many, hiding his feelings behind a veneer of affability and bonhomie. To his old neighbor, distant cousin, discreet friend, loyal aid, and steadfast curator Margaret Suckley, he showed the truer, more vulnerable side of himself.

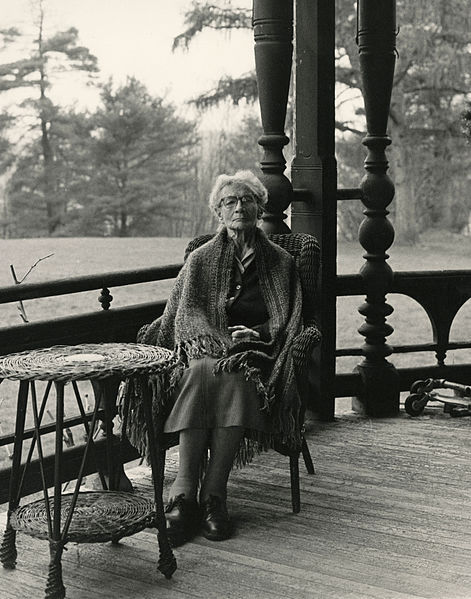

Ms. Suckley later in life at Wilderstein, 1988. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

Further reading:

Hufbauer, Benjamin. “The Roosevelt Presidential Library: A Shift in Commemoration.” American Studies, vol. 42, no. 3, Fall 2001, pp. 173–193.

Koch, Cynthia M. and Lynn A. Bassanese. “Roosevelt and His Library, Parts 1 & 2.” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 2001, Web.

McCoy, Donald R. "The Beginnings of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library," Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives, vol. 7, no. 3, Fall 1975, pp. 137-150.

Persico, Joseph E. Franklin & Lucy: President Roosevelt, Mrs. Rutherford, and the Other Remarkable Women in His Life. Random House, 2008.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Closest Companion: The Unknown Story of the Intimate Friendship between Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Suckley. Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

#women's history#library history#tumblarians#daisy suckley#fdr#margaret suckley#archivists#presidential collections#new york history#fdr presidential library#women of library history

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

Stokes was no stranger to television and its role in molding public opinion. An activist archivist, she had been a librarian with the Free Library of Philadelphia for nearly 20 years before being fired in the early 1960s, likely for her work as a Communist party organizer. From 1968 to 1971, she had co-produced Input, a Sunday-morning talk show airing on the local Philadelphia CBS affiliate, with John S. Stokes Jr., who would later become her husband. Input brought together academics, community and religious leaders, activists, scientists, and artists to openly discuss social justice issues and other topics of the day.

(via AL Direct, 5/3/2019)

#marion stokes#women's history wednesday#women's history#library history#philadelphia#free library of philadelphia#archivists#public librarians#tv history#television history#feminism#women of library history

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

This blog post from the ALA Archives at the University of Illinois Archives highlights the work of librarians Glyndon Flynt Greer and Mable McKissick, two of the founders of the Coretta Scott King Book Awards:

It was founded by librarians Glyndon Flynt Greer and Mable McKissick, and publisher John Carroll during the 1969 American Library Association Annual Conference in Atlantic City. According to McKissick, “We [her and Greer] met at the booth of John Carroll. Since it was the day before the Newbery/Caldecott awards, the discussion turned to Black authors …”(2) and their lack of representation. It is reported that Carroll overhead the conversation and asked, “Then why don’t you ladies establish your own award?”(3)

#women's history#library history#coretta scott king book awards#women's history wednesday#csk50#glyndon flynt greer#mable mckissick#john carroll#american library association#book awards#ala archives

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camilla Leach

Today’s post, entitled “Camilla Leach: A sophisticated spitfire (1835-1930)”, comes from Paula Seeger, Design Library, University of Oregon, with significant contributions from Ed Teague, Retired Director of Branch Libraries, University of Oregon. All photos are courtesy of University of Oregon Libraries.

Summary

Ultimately known for her role as the founding librarian-manager of the Design (formerly Architecture and Allied Arts) Library at the University of Oregon, Miss Camilla Leach left a legacy of caring for student success and ambition throughout her long career. Only in the last third of her life did she find a role in the library, with the majority of her time spent in the classroom or dormitory, supervising and guiding the lives of young adults, especially girls. Miss Leach constantly updated her position during a long career trajectory, never losing her love of the arts and French culture and design. She travelled to Paris in her 30s, was committed to the plight of French orphans during WWI, and translated Auguste Racinet’s L’Ornement Polychrome (Paris, 1869-73) for the benefit of the students of the University of Oregon. This fascination with French culture and artistry bestowed an air of sophistication to Miss Leach. Combined with her “go-getter” determination that impressed the administration and faculty, Miss Leach’s keen observational skills and broad knowledge let her anticipate the needs and interests of her loyal colleagues and patrons. This unique mix allowed Miss Leach to win over those who doubted she could take an active role in organizing a new library and departmental administration office at the age of 79. Even though she “retired” twice from the libraries at the University, Miss Leach remained active in the community and social circles, giving talks on the relation of art to library work to civic groups into her 90s. Piecing together her history, as well as reflecting on her legacy, is a worthy exercise that re-emphasizes a lifelong commitment to arts education and wisdom born from the strength of longevity.

Background and Early Career

Miss Leach’s history has been difficult to completely trace. We assume certain facets of her life and try to fill the gaps within her story for which we do not yet have evidence, such as Miss Leach’s education and much of her early life. While we know she was born in Rochester, New York in 1835, and there are some accounts of her attending East Coast schools, we next find definitive mention of her in 1855. While still living at home in New York, her profession was listed as “teacher” at age 19 in the New York state census of 1855, indicating she began her teaching career early. Using broad searches of historical newspapers, we can see that she travelled south and west, taking a position at a teaching college in 1859. Her title was Governess and assistant teacher of the “English branches” at East Alabama Female College (also called “Tuskegee Female College” at its founding in 1854, later “Huntingdon College” after the institution moved to Montgomery). By 1865, she arrived in Chicago and was granted a teaching certificate to teach at a number of public schools including Skinner school and the main Chicago High School. It is during this time Miss Leach was elected to be “Professor of Rhetoric and English Literature” at the high school and a wage dispute was noted (1870):

Miss Camilla Leach was recently elected professor of English literature in the Chicago high school, but the board of education refuses to pay her over $1000 for work for which her male predecessor received $2,200.1

It is unknown whether this dispute led to her resignation, but shortly after, in 1871, Miss Leach applied for a passport to travel to Europe to study art and visited Paris in 1871-72, becoming well-versed in French art and architecture. After Europe, she returned to a position as a high school teacher in St. Louis in 1872-73, and was announced as a teacher at the Washington school for Minneapolis Public Schools in 1878. Another newspaper account in August 1878 mentioned that she was an art instructor in a Placerville, CA, ladies’ seminary and private school (TAE Academy). Having settled in Oakland, CA, from 1879-89, Miss Leach taught drawing and French at the Snell Seminary, a “boarding and day school for girls” that operated from 1878-1912. While at the Snell Seminary, Miss Leach perhaps learned more about opportunities that could be found in Oregon. During her tenure, one of the Seminary’s founders, Dr. Margaret Snell, began an affiliation with Oregon State University (then called the Corvallis College and the State Agricultural College of Oregon) through a Corvallis resident who happened to be staying in the Oakland area caring for an ailing relative. Dr. Snell went on to found the department of “Household Economy and Hygiene in the Far West,” the first in the western U.S. and went on to a great legacy at Oregon State.3

Perhaps also influenced by Dr. Snell’s continuing education in the East, Miss Leach attended Bryn Mawr with “Hearer” status in 1889-902 and it is assumed that this is where she completed her education about “library methods”. Returning to California, Miss Leach was introduced as Mistress of Roble Hall, a ladies’ dormitory at Stanford University in 1891, the first year Stanford started enrolling students. After administrative and facility restructuring, she was let go from Stanford in 1892, heading north to Portland, OR.

Miss Leach stayed five years in Portland working as a private tutor and head of a private school, perhaps of her own creation, within a wealthy businessman’s household. These many years spent as an educator, administrator, and overall caregiver of young student lives had now prepared Miss Leach for a more significant career transition as she was recruited by the University of Oregon in 1897 to become their first dual registrar-University librarian, beginning her new role in libraries. It is unknown what motivated this career change for Miss Leach at about age 60--or age 50: In subsequent census records Miss Leach somehow gets ten years younger.

University of Oregon Career

In 1897, the University of Oregon in Eugene recruited Miss Leach to be the school’s first registrar while also serving as the University’s librarian in a combined position. The dual job was split in 1899, when Miss Leach became “only” the University librarian and, later, the school’s first art librarian. She contributed to the school’s publications, offering a review of Bryn Mawr and several original pieces of poetry for the University’s yearbook and monthly journals. The University originally had a small library collection, based mainly upon generous donations from professors before state allocations were negotiated, and the collection was relocated several times before the first purpose-built library opened in 1906. In 1912, Miss Leach retired from her library position, but continued to teach in the art school as a drawing instructor and teacher of art history, which she continued throughout her next role. At the time of her “retirement” as a reference librarian from the main library, the local newspaper told of her reputation:

Miss Leach is perhaps better known than any other one character upon the Oregon campus during this time. She knew personally every student from freshman to senior, and has hundreds of sincere friends among the Oregon graduates all over the state.4

Resistant to fully retiring, and beloved by faculty and students, Miss Leach continued to work in the new main library until 1914 when, at the age of 79 years, she became the founding librarian and administrative assistant at the new School of Architecture and Allied Arts. Her transfer to the new location was met with doubt by the founding Dean of the school, Ellis F. Lawrence, who was resistant to hiring a 79-year-old to the post. He expressed his doubts to the University President, and was reassured that Miss Leach could hold her own and make worthy contributions. Dean Lawrence described his first meeting with her as particularly memorable:

When I [met] her at the first staff conference I was very conscious that there was a divine fire in the proud little figure before me. It was shining through the brightest pair of the darkest eyes I have ever felt boring into my soul. After listening to my outline of procedure and objectives, Miss Camilla leaned over the table and in the snappy, crisp utterance I was later to know so well, she said, “Sir, I was teaching art before you were born.” If she had said ‘thirty years before you were born’, I feel sure she would have been within the truth. Naturally I thought – here is a Tartar to deal with, and anticipated plenty of excitement. Little did I know how deliciously that excitement was to be; how surprising and invigorating it could be! Miss Camilla was placed in charge of the Art Library. Before I knew it she had that department functioning more efficiently than I had thought possible, even in my fondest dreams. But her work did not stop there. She became our matriarch, tradition builder, exemplar of manners, personnel officer – and very much in evidence as advisor to the Dean.5

Indeed, students took to calling her the “Mother of Our Library” and Aunt Psyche (Pidgy), a

[G]uiding spirit since its inception….All of us have been visited by her kindly interest, -- the serious have been led to that exact niche where Volume X lies; the frivolous (and everyone knows that some of us often go to the library on missions quite foreign to study), -- we have been ushered into her acquaintance by the sharp tap of her pencil or by the censure of her warning nod. But however that may be, each of us, as we step out into the world, is to carry a pleasant recollection of Miss Camilla Leach.6

Another story of Miss Leach helping students, while displaying her expertise in French architecture, is noted in the Eugene Guard newspaper from Saturday, April 20, 1918: A girl on campus had a friend stationed in France, but the US military would not reveal the location. The girl’s friend sent her a photo with a cathedral in the background. The girl didn’t recognize it but another friend suggested she take it to Miss Leach, the art librarian. Sure enough, Miss Leach immediately identified the cathedral and the girl was able to locate her military friend.7

In addition to her teaching, library, and administrative duties, Miss Leach consulted with library colleagues and was in attendance at the earliest foundational meetings of the Oregon Library Association (1904). Her attendance at local arts events is well-documented in the local newspapers, as are the frequent talks she would give to local civic organizations (one titled “The Relation of Art to Library Work”), and her reputation as a fine sketch and free-hand artist was known throughout the Northwest.

Philosophy of Academic Rigor and Student Advocacy

Miss Leach had a sense of humor that she rarely indulged, but there were certain topics that were sure to raise her ire. In one instance, as regaled by Dean Lawrence in his memorial writing, a painting professor teaching Civilization and Art Epochs was discussing symbolism with his class. It was reported that he used the example of the serpent, once a symbol of wisdom, but over the years mixed together with many ingredients and encased in a skin, much like a sausage. This description, when relayed to an incensed Miss Leach, caused her to question why culture and wisdom should be treated with levity. She often wondered why artists and architects could not have higher academic standards. Dean Lawrence described her struggle with the habits of scholarship:

Knowledge was to her the basis of her philosophy and conduct, though she little knew how much her intuitions and her fine intellectual common-sense tempered that knowledge. … [T]he idiosyncrasies of the creative artists often irked her. Yet she came to participate valiantly in the methods of the School which called for the freedom necessary to bring out the creative urge in each student.8

To demonstrate how Miss Leach advocated for her students, Dean Lawrence told of a new student who worked extremely hard and produced decent results for one who had no artistic background, which thrilled Miss Leach. However, after flunking out at the end of the term, causing the student to leave without even a good-bye, Miss Leach arrived at the Dean’s office, furious at a system that would let go of a potential genius and lobbied on his behalf. She urged the Dean to reconsider the student’s case and bring it before the Faculty. Together they won the case and the student was reinstated and went on to “make good,” much to the satisfaction of Miss Leach.

Legacy

Miss Leach completed a handwritten history of the University of Oregon in 1900, likely one of the first written of the 24-year old institution, with a volume still found in the library’s Special Collections and University Archives department. During her time at UO, Miss Leach, along with other library and University staff, were interested in caring for French children affected by the war, particularly in 1919. This seems entirely appropriate and in line with Miss Leach’s fascination with French culture and arts.

Camilla Leach finally truly retired in 1924, primarily due to declining health after a fall, and losing her eyesight. She moved back east and died in Jonesville, Michigan (near Battle Creek) in 1930, while staying with a relative. Dean Lawrence wrote a tribute to Miss Leach after her death, describing her ultimately as an “exquisite cameo who was classic in her perfection.” He noted that she was in the process of translating Auguste Racinet’s L’Ornement Polychrome (Paris, 1869-73) for the benefit of the students. The Racinet volume can still be found among the collections of today’s Design Library, which in 1992 was the focus of an expansion of Lawrence Hall, the home of the College of Design.

There are several other books still containing the bookplates indicating they were purchased with the fund set up for the “Camilla Leach Collection of Art Books,” a special collection in the University Library that remained well after Miss Leach’s death. The fund, set up in 1923, was described as a perpetual fund designed for purchasing art books from the interest earned each year. Mrs. Henry Villard, widow of one of the pioneer founders of the University, donated and suggested that a portion of the yearly endowment to the libraries from the Villard gift should be set aside to build up the Leach fund. There are several newspaper accounts of faculty members, and their families, donating books and financial support to the fund. In addition to books purchased, over the years as Miss Leach’s history became better known, library staff have unofficially named a two-story reading room the “Camilla Leach Room” in her honor. The room enables study and research and is used to present selections from the library’s collection of artist’s books, rare books, and other artifacts.

Perhaps the most touching of Miss Leach’s legacy is how she influenced her initial detractors. Dean Lawrence fancied himself a bit of a creative writer, and one can find several complete and incomplete short stories and novella manuscripts among his personal writings in the archives of the University of Oregon Libraries. In addition to the 6-page memorial tribute that Lawrence penned that was devoted to Miss Leach (excerpted above), one can also read an incomplete 60-page murder-mystery novella. The protagonist who is able to solve the case faster than the sheriff? A Miss Marple-like character named “Miss Camilla Chaffin” described as wearing a Paisley shawl, lace collar, and a lavender ribbon in her hair. She was the “oldest of the old-timers” and was friendly with the “dear old doddering Dean.”9

As we piece together Miss Leach’s legacy, her strength is revealed in her loyal determination to provide the best resources and environment for students in order to nurture their creativity and scholarly output. Her ability to expose interests, and proactively anticipate the materials needed for letting those interests flourish, were among her special gifts to the students she served and the colleagues she assisted. Her legacy continues today in the resources and services that are at the forefront of today’s Design Library.

Notes

1 “Untitled News Article,” Weekly Oregon Statesman, March 18, 1870, 3.

2 Program, Bryn Mawr College, p. 252. Accessed through Google Books.

3 “The 'Apostle’ of Fresh Air...Margaret Comstock Snell (1844-1923)” George Edmonston Jr., OSU Alumni Association, undated. http://www.osualum.com/s/359/16/interior.aspx?sid=359&gid=1001&pgid=536

4 “Veteran U.-O. Librarian Retires with Honor,” Oregon Daily Journal, October 4, 1912.

5 Ellis F. Lawrence, “Miss Camilla – A Portrait” (Eugene, Ore., 1930), in Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers, Ax 056, Box 13, Special Collections and University Archive of the University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, 2.

6 “Miss Camilla Leach,” in Oregana, 1912 vol., 23.

7 “Censor Sleeps on Job,” Eugene Guard, April 20, 1918, 4.

8 Ellis F. Lawrence, “Miss Camilla – A Portrait” (Eugene, Ore., 1930), in Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers, Ax 056, Box 13, Special Collections and University Archive of the University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, 4-5.

9 Ellis F. Lawrence, “The Red Tide,” in Ellis Fuller Lawrence papers, Special Collections and University Archive of the University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, also in Harmony in diversity : the architecture and teaching of Ellis F. Lawrence, edited by Michael Shellenbarger, Eugene, Or. : Museum of Art and the Historic Preservation Program, School of Architecture and Allied Arts, University of Oregon, 1989.

Other sources consulted

● 1903 Webfoot (University of Oregon Yearbook)

● Bishop’s Oakland Directory for 1880-81 "Containing a business directory, street guide, record of the city government, its institutions, etc." (varies). "Also a directory of the town of Alameda" (issues for <1880-81-> also include Berkeley). Compiled by D.M. Bishop & Co. Description based on: 1876-7. Published: San Francisco : Directory Pub, Co., <1880-> Open Library OL25463540M. Internet Archive bishopsoaklanddi187778dmbi. LC Control Number 11012620. https://archive.org/details/bishopsoaklanddi188081dmbi (Listed as teacher at Snell’s Seminary)

● “Board of Education,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1865, 4.

● “Board of Education,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 22, 1878, 4.

● “East Alabama Female College,” South Western Baptist, November 17, 1859, 3.

● “Former Undergraduates That Have Not Received Their Degrees,” in Program Bryn Mawr College, 1903-04, 1906, 283, https://books.google.com/books?id=GKRIAQAAMAAJ.

● “General Register of the Officers and Alumni 1873-1907,” vol. 5, no. 4, University of Oregon Bulletin (Eugene, Ore.: University of Oregon, 1908), http://hdl.handle.net/1794/11152.

● “Gift of $100 Received,” Eugene Guard, November 6, 1924, 12.

● Henry D. Sheldon, The University of Oregon Library 1882-1942, Studies in Bibliography, No. 1 (Eugene, Ore.: University of Oregon, 1942), http://hdl.handle.net/1794/23064.

● "New York State Census, 1855," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9BPY-97K6?cc=1937366&wc=M6G3-GZ7%3A237407901%2C237457701 : 22 May 2014), Orleans > Kendall > image 15 of 40; county clerk offices, New York. (teacher at 19)

● “Salary Dispute,” The Illinois [Chicago] Schoolmaster A journal of educational literature and news v. 4 1871, 260 https://ia601409.us.archive.org/5/items/illinoisschoolma41871gove/illinoisschoolma41871gove.pdf

● “SPOTLIGHT ON A LEGACY: Treasures of the Design Library” Ed Teague, 2014, https://library.uoregon.edu/design/century

● “TAE Academy,” Placerville Mountain Democrat, August 10, 1878, n.p.

● "United States Census, 1900," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MSDX-B6R : accessed 15 April 2018), Camilla Leach in household of Mary E Cox, South Eugene Precincts 1 and 2 Eugene city, Lane, Oregon, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 112, sheet 8A, family 162, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,241,348. (age = ten years younger)

● “Untitled News Piece,” Eugene Guard, May 1, 1928, 6. – Talk “Relation of Art to Library Work”

● “What’s in a Name? Design, and Library” Ed Teague, Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Sept. 12, 2017. http://www.acsa-arch.org/acsa-news/read/read-more/acsa-news/2017/09/12/what-s-in-a-name-design-and-library

#women's history wednesday#women of library history#oregon history#university of oregon#tumblarians#camilla leach#academic librarians#design librarians#design library#library history

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miriam Wood

Today’s post was submitted by Bel Outwater, Library Manager at the Auburn Public Library in Auburn, Georgia. She says “My library would not exist without [Miriam Wood’s] efforts, and I cannot count the number of lives she has touched.” The image above shows Miriam Wood sitting in the current Auburn Library.

Miriam Louise Wood was born July 30, 1930 to Rainey and Daisy Wood in Auburn, Georgia. She was the only girl with three brothers. She loved to read, and would sit for hours on the steps of the old Auburn School in the summer, waiting for the bookmobile lady in her big Buick to come by and check out books to Auburn’s children.

This small child’s love of books would grow into a big dream of access to books for all of Auburn. In 1991, Miriam and local Reverend Joan Biles started a book depository with Piedmont Regional Library System. It had a $100 annual budget and was located in a trailer behind the Methodist Church (now the Seventh Day Adventist Church). It quickly outgrew the space and a new location was sought. In 1995 it was moved into a small house without heat or air conditioning. Local support and continued growth of the library enabled a new location in 1997 into Auburn’s former post office building, the 1,134 square foot J.D. Withers Building. It received full library service status in 1999, and its first four computers through the Gates Foundation in 2000. 2001 began the process of fundraising for a new, dedicated library building that was brought to fruition in 2007. The Auburn Public Library is a beautiful 6,100 square foot building located in downtown Auburn next to the children’s park. Recognizing that this building would not exist without the dream and passion of Miriam Wood, her likeness is engraved on a plaque on the outside of the building.

Above: Auburn Library Manager Julia Simpson (l), Mayor Linda Blechinger (c), and Miriam Wood (r) at Miriam Wood Day

In addition to founding the library, Miriam helped create the Auburn Museum. She was an amateur historian, a member of the Barrow County Historical Society, and one of the last members of the original Auburn Township. She taught in Dacula, Georgia for many years. On May 2, 2015, Auburn’s Mayor Linda Blechinger declared that day “Miriam Wood Day” at the city’s annual “History and Heroes” festival, recognizing Miriam’s role as both historian and hero. She passed away in June 2018.

The results of her efforts are reflected in users of the library and in the hearts of those fortunate enough to have worked side by side with her. Miriam Wood was a fierce champion of literacy and a passionate historian. She was a wonderful co-worker and an even better friend. The world is a little less bright without her light shining, but her dream lives on.

Above: Miriam at the library in 2004

#women of library history#women's history wednesday#georgia history#library history#tumblarians#miriam wood#auburn#auburn georgia#library founders

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

María Teresa Márquez and CHICLE: The First Chicana/o Electronic Mailing List

This piece by Miguel Juárez is reprinted, with permission, from Mujeres Talk, where it was posted in 2014.

These days we take e-mail and electronic lists for granted, but imagine a world where there is no e-mail or exchange of information like we have now? That was the world for Humanities Librarian María Teresa Márquez at the University of New Mexico (UNM) Zimmerman Library and creator of CHICLE, the first Chicana/o electronic mailing list created in 1991, to focus on Latino literature and later on the social sciences. [1] Other Chicano/Latino listservs include Roberto Vásquez’s Lared Latina of the Intermountain Southwest (Lared-L) [2] created in 1996, and Roberto Calderon’s Historia-L, created in March 2003. [3] These electronic lists were influential in expanding communication and opportunities among Chicanas/os. CHICLE, nevertheless, deserves wider recognition as a pioneering effort whose importance has been overlooked.

In many instances the Internet revolution was shepherded by librarians in their institutions. Libraries and librarians were early adopters of this new technology. Márquez used computers and e-mail in her work in the Government Information Department at UNM. However, it was in the Library and Information Science Program at California State University, Fullerton, where she first learned about and used computers in a federally-funded program in the 1970s that sought to increase the number of Mexican American librarians. At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Márquez earned a Certificate of Advanced Study in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science, where she learned more about computers and databases.

In April 1991, Márquez attended the Nineteenth Annual Conference (Los Dos Méxicos) of the National Association of [Chicana and ] Chicano Studies (NACS) in Hermosillo, Sonora, México. One of the panels, moderated by Professor Francisco Lomelí, University of California, Santa Barbara, presented papers on “Literatura Chicana.” While discussing the topic, scholars raised problems encountered in communicating with each other and in sharing information on new publications and current research. Márquez volunteered to create a listserv or electronic mailing list and explained how it could be of use in keeping scholars informed. At UNM, she developed the list and Professor Erlinda V. Gonzales-Berry, then a faculty member in the UNM Spanish Department, coined its name-CHICLE (which translates into gum in Spanish). CHICLE stood for Chicana/Chicano Literature Exchange.

According to Márquez, most faculty members were not willing to join CHICLE, citing no experience with computers nor did they wish to consider its potential use in academic work. Yet, Márquez launched CHICLE with eight subscribers. She attended numerous academic conferences to distribute fliers and talk to people about the list and recruit subscribers. Furthermore, she attempted to impress upon her listeners the need to be at the forefront of technology, but Márquez said she had few takers. Believing in the importance of the list and in this new form of communication, she persevered and she states: “One day, all of a sudden, membership went up to 800!” As more institutions and faculty members started using computers, the list exploded in the number of subscribers.

The idea for the list evolved from Márquez’s work in a library setting that was used to basically communicating internally. At first Márquez sent out all of the information on the list because she had most of it. She would use librarian’s tools and lists of new books, information of upcoming conferences, calls for papers, and articles that would be of interest, but she received very little in return. The list was limited to her contributions in its early years. Later, as the number of subscribers in the social sciences increased the list moved away from literature. Numerous topics were discussed over the list’s ten–year history (1991-2001), but eventually its popularity led to its demise. Subscribers often stated that the list contained too much information and was time consuming.

Among the active subscribers to CHICLE was archivist Dorinda Moreno, [4] who later went on to work with Lared as well as with Dr. Robert Calderón‘s Historia-L. Moreno contributed history-related information. In contrast to Márquez’s effort, Calderón changed his list to a closed list with a finite number of subscribers where he posted items of interest to the Chicano/a academic community, as opposed to CHICLE which was an open forum. [5] Initially CHICLE was designed as an open forum to encourage broad participation. Dr. Tey Mariana Nunn, now Director and Chief Curator of the Art Museum and Visual Arts Program at the National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum in Albuquerque, played a large role in promoting the list in its early days. Nunn was a graduate work-study student. Additionally, Renee Stephens, now at San Francisco State University, then a graduate work-study student at UNM, was also editor for the list, a task inherited from Janice Gould. All these women were instrumental in the success of CHICLE. Eventually, the expansion of the Internet eclipsed Chicana/o listservs.

When CHICLE began, Márquez acted as the sole moderator, but over time, as it gained popularity, she trained students to run it. The popular list existed until her funding to hire work-study students ran out. Her institution was reluctant to provide further support. CHICLE was not considered an appropriate academic part of Márquez’s professional responsibilities. Management of the list competed with duties at the library and as subscriptions grew, it became overwhelming and difficult. Márquez who often managed the list on her own time, stated she would have continued the list but that it would have required more energy than she was willing to invest. When Márquez decided it was time to move on and discontinue the list, she approached the UNM Technical Center to store the CHICLE files. The Center claimed it did not have sufficient storage space for her files. As news of CHICLE’s imminent shutdown spread, people volunteered to keep the list going but were deterred by the amount of work entailed.

Dr. Diana I. Rios, who has a joint appointment in the Department of Communication and El Instituto at the University of Connecticut among others, made attempts to create an archive of CHICLE. She made copies of conversations via cut and paste. There were attempts to incorporate CHICLE into another list but Ríos did not want that to happen. Eventually, Latino literary blogs such as Pluma Fronteriza [6] and La Bloga [7] emerged to continue where CHICLE left off.

After CHICLE, Márquez took her energy and enthusiasm in supporting Latina/o students and created a program called CHIPOTLE. [8] She used CHIPOTLE to familiarize Chicana/o rural students with the academic environment and to reach out to surrounding communities. Via grant and affiliated department funded sponsorship, Márquez would take posters and boxes of books by Chicana/Chicano writers to give to students when she visited Hispanic-dominate schools. As part of CHIPOTLE, she created a forum to bring Latina/o speakers into the library and encouraged Latina/o students to utilize the research resources available to them. She directed two programs funded by Rudolfo Anaya: Premío Aztlán and Critica Nueva. Premío Aztlán recognized emerging Chicana/o writers and Critica Nueva was an award honoring the foremost scholars who produced a body of literary criticism based on Chicana/o literature. For many years, Márquez was the only Latina librarian at the University of New Mexico University Libraries. Presently, she is an Associate Professor Emerita. No Latina/o librarians have been hired since her retirement.

In the era of search engines, web browsers, blogs, wiki’s, intranets, and social media, it is important to recognize the efforts of a pioneering Chicana librarian and a pioneering electronic list that was a unique cultural creation. It was given life by so many who read it, posted on it, and worked on it. CHICLE brought many voices together and established a foundation for the future. As Márquez stated, “CHICLE was the catalyst for many things.” [9]

Notes

[1] María Teresa Márquez, interview by the author, Albuquerque, April 28, 2007.

[2] Lared Latina of the Intermountain Southwest, was established in the Spring of 1996 by Roberto Vásquez, as a World Wide Web Forum, for the purpose of disseminating socio-political, cultural, educational, and economic information about Latinos in the Albuquerque/Santa Fe Metro area and the Intermountain Region which includes Metropolitan Areas such as the Salt Lake City/Ogden region, Denver, Phoenix, Tucson, Boise, Las Vegas and Reno, Nevada, accessed January 30, 2014: http://www.lared-latina.com/bio.html.

[3] Dr. Roberto R. Calderón, interview by the author, College Station, Texas, December 20, 2007. Historia-l, focused on Chicano/a history, started as “96SERADC” with 200 subscribers in May 1996 and continued through October 1997. Originally housed at the University of Washington, it helped mobilize the first Immigrant Rights March on Washington, D.C., held on Saturday, October 12, 1996. The march had upwards of 50,000 participants, half of whom were Latina/o college students from across the country. The listserv list then changed venues and was housed at the University of California at Riverside becoming “2000SERADC,” from November 1997 through August 1999, at which point the listserv list was discontinued. This twice-named listserv list project lasted three-and-a-half-years.

[4] Dorinda Moreno, Chicano/native Apache (Mother, Grandmother, Great Grandmother) has worked bridging Elders, Women of Color, Inter-generational networks and alliances, with a focus on non-racist, non-sexist (LGBT community), non-toxic–Chicano/a, Mexicano/a, Latino/a, Indigenous communities, projects and networks that give voice to under-represented groups and enable feminist empowerment through social change networks and innovations. As an early Web pioneer and archivist, she has been actively using the Internet since 1973.

[5] Calderón interview.

[6] Pluma Fronteriza began as a printed newsletter, then became a blog and currently has a companion site on Facebook: Accessed February 8, 2014: http://plumafronteriza.blogspot.com/

[7] La Bloga hosts various bloggers who write on Latino/a literature. Accessed February 8, 2014: http://labloga.blogspot.com/

[8] According to the Memidex Online Dictionary and Thesaurus, Chipotle comes from the Nahuatl word chilpoctli meaning “smoked chili pepper” is a smoke-dried jalapeño, accessed January 30, 2014, http://www.memidex.com/chipotles.

[9] Márquez interview.

Miguel Juárez is a faculty member in the Department of History at the University of Texas in El Paso (UTEP), where he earned a doctorate in Borderlands History. He has a Masters in Library Science (MLS) degree from the State University of New York at Buffalo and a Masters of Arts (MA) in Border History from UTEP. In 1997, he published the book: Colors on Desert Walls: the Murals of El Paso (Texas Western Press). Miguel has curated numerous exhibits, as well as written articles in academic journals, newsletters, and newspapers focusing on librarianship, archives, and the cultural arts. From 1998 to 2008, Miguel worked as an academic librarian at the following institutions and centers: State University of New York at Buffalo; Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona; Texas A&M in College Station, TX; and the Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC) at UCLA. He is also co-editor with Rebecca Hankins of the upcoming book Where Are All the Librarians of Color? The Experiences of People of Color in Academia, part of the Series on Critical Multiculturalism in Information Studies of Litwin Books. The author would like to thank María Teresa Márquez, Dr. Roberto Calderón, Dorinda Moreno, Dr. Tey Mariana Nunn, Renee Stephens, Rebecca Hankins and Dr. Diana Ríos for making suggestions and recommendations for this article. This work is part of a larger body of research on Chicana/o electronic and digital projects during the advent of the Internet.

#women of library history#women's history wednesday#women's history#library history#tumblarians#María Teresa Márquez#university of new mexico#new mexico history#chicle#mailing lists#latinx librarians#latina librarians#california state university fullerton

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome back to WoLH!

Welcome to another year of Women of Library History posts! Our first post will go up tomorrow (March 1st), and then we will have a post scheduled for every other Wednesday. Our goal for 2019 is to keep posts going all year, rather than only posting in March.

Submissions are still being accepted for 2019--please see our Call for Submissions for details.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women of Library History Returns!

We are now accepting submissions for year seven of Women of Library History in 2019.

There are a few ways you can get involved:

1. You can submit a full post, following our Call for Submissions.

2. We have a list of potential subjects who have been suggested by readers or located in the history of the Feminist Task Force newsletter. If you’re interested in doing some research and writing a post (or multiple posts) from this list, please e-mail Katelyn at womenoflibraryhistory at gmail.

3. Encourage a friend or colleague to write a post for us!

See our 2019 Call for Submissions for more details.

This year, we are planning to accept & run posts throughout the year, rather than focusing only in March. However, we definitely need some posts to get going in March--if you need a deadline to motivate you, let me suggest February 11th (next Monday)!

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

While I was at the agency (there were several in the 60s) they asked what else I could do. I answered with the confidence of a 20 year old that I liked library work.( I had shelved books for work study.) They sent me off to Scituate Junior High where the only question the principal asked was, "What is that box for?" It was the card catalog and I got the job. The librarians at my college were horrified and had me drive to New Jersey for a week of information packed sessions.

from “One Lucky Librarian” by Pat Keogh, retired school librarian, 2016 recipient of the Peggy Hallisey Lifetime Achievement Award (Massachusetts School Library Association), and past president of Wondermore.

Pat passed away on May 2, 2018; I came across her obituary in The Horn Book Magazine (July/August 2018).

#librarians#tumblarians#library history#women's history#card catalogs#school librarians#massachusetts#massachusetts history#wondermore#scituate junior high#weston public schools#women of library history

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

Over at the Horn Book, Roger Sutton has written tributes to five of his mentors: Betsy Hearne, Hazel Rochman, Lillian N. Gerhardt, Zena Sutherland, and Pomona Public Library children’s librarian (and retired Mansfield Public Library director) Louise Bailey:

Louise changed that: she was young, smart, tenacious, and politically engaged. And so good with kids: I remember one boy, Kenny, who was a habitué of the library not because he was a great reader but because his home life was unbearable. One week he was tremendously excited because a TV crew had come to shoot video of his karate class for some local-interest feature, and he must have told Louise and me a hundred times to remember to tune in. We did–and, heartbreakingly, no Kenny appeared in the footage. The next day, he asked Louise, so hopefully, if she had spotted him in the segment, maybe in the background. “No, Kenny,” she said gently, “I didn’t.” Telling lies to the young is wrong, Yevtushenko told us, and Louise was and is ferociously devoted to both the young and the truth.

In tagging this post, I notice that we had a post way back in 2013 about Clara Webber, who was the children’s librarian at the Pomona Public Library from 1948 to 1970.

#tumblarians#women's history#library history#louise bailey#pomona public library#california history#pomona#mansfield public library#connecticut history#mansfield#children's librarians#youth services librarians#library directors#women of library history

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbara Williams Jenkins, Ph.D.

This post was written by Dr. Theodosia T. Shields & Doris Johnson and submitted on behalf of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. Last year’s post on Amanda Rudd was also brought to us by BCALA.

For over forty years Dr. Barbara Williams Jenkins greatly contributed to the library profession on a local, regional and national level. Even after retiring, she continues to contribute to her beloved profession.

Barbara was born in Union, South Carolina but grew up in Orangeburg, South Carolina, where she received her high school diploma from Wilkinson High School. She graduated from Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina, with a B.A. degree and earned a MSLS from the University of Illinois, Urbana, IL. Her post-Master’s work included advance study at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Atlanta University and Clemson University. These subsequent educational experiences were followed by her studying and receiving her Ph. D. in Library and Information Sciences from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick in 1980.

Her professional career began in her hometown of Orangeburg as a Reserve and Circulation Librarian at South Carolina State in 1956. After serving in this role for two years, she became the Reference and Documents Librarian. This was followed by her becoming Library Director at South Carolina State in 1962 where she served until 1987. In 1987 she was promoted to Dean of Library and Information Services at South Carolina State. She served as Dean until her retirement in 1997.

During her tenure at South Carolina State (now known as South Carolina State University), Barbara served with distinction in all roles. At the only public supported Historically Black College and University in South Carolina, Barbara worked diligently to provide leadership on the campus, in the state and beyond. She was an advocate for the library program.

Some of the leadership roles that she assumed included the following: the first African American President of the South Carolina Library Association 1986-1987; Southeastern Library Association- College Section Director 1978 – 1980; American Library Association Council 1978-1982; Association of National Agricultural Library, Inc. 1890 Land -Grant Library Directors’ Association Tuskegee University (President 1979-85); American Library Association Black Caucus – Chairperson 1984-85, Southeastern Library Network ( SOLINET) - Board of Directors 1989-92; and South Carolina Governor’s Conference on Library and Information Services (1978 – 1979) and National Endowment for the Humanities – Evaluator – 1979. In 1969 she served as a Library Evaluator – Institutional Self- Study for the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). She continued to serve in this capacity until her retirement in 1997. She also served on the College Consulting Network in 1991 and served until retirement.

Because of her love of African American history and her passion for preserving that history, she was a member of the African-American Heritage Council and the Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation. As a collector of African American history and a researcher, she played a significant role in the establishment of the institution’s historical collection. Her work extended beyond campus by her affiliation with the South Carolina Archives & History Commission. She was instrumental in locating and identifying campus historical sites and buildings in Orangeburg along with providing training sessions on how to preserve this history. Her actions led to her becoming a charter member of the South Carolina African American Heritage Commission.

For her service to the campus community and beyond, she received many accolades and awards during her career. She received the “Boss of the Year Award” in 1980 from the Orangeburg Chapter of the Professional Secretaries International; 1890 Land-Grant Director’s Association Award 1978-84; President’s Award, South Carolina Library Association, 1987; South Carolina State College Distinguished Service Award, 1991; SOLINET Board of Directors Service Award, 1992 and the college’s First President’s Service Award in 1997. Additionally, on February 27,2000 at the Founders’ Day program, Dr. Leroy Davis, President of South Carolina State University bestowed upon Dr. Jenkins the first emeritus award.

As a leader and advocate for the profession, Dr. Jenkins worked diligently to share and instill these values with her staff and others in the profession. She served as a role model for many librarians.

In addition to a very active professional life, she also held memberships in many civil and social organizations including Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc. (Past Regional Director for the South Atlantic Region). She is also a member of the Williams Chapel AME Church.

She was married to the late Robert A. Jenkins and they had two children and five grandchildren. As a retiree she continues to devote her time to African American and local history. She also loves to talk about the library profession and continues to serve as a role model for librarians and aspiring librarians.

Works Cited:

“Spotlight on Dr. Barbara Williams Jenkins” http://www.scaaheritagefound.org/call_response2009fall.pdf

"Retirement: A New Beginning Reflections of Dr. Barbara W. Jenkins and Mrs. Eartha J. Corbett", June 7, 1997 Kirkland W. Green Student Center, South Carolina State University.

#tumblarians#library history#women's history#barbara williams jenkins#south carolina state#academic librarians#library administrators#south carolina history#Delta Sigma Theta#ala#solinet#bcala#women of library history#barbara w. jenkins

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lois Mai Chan

Our post today comes from Melissa Freiley, an LIS student at the University of North Texas and the library cataloging technician at Denton (TX) Indepedent School District.

“I get the biggest satisfaction from teaching,” Dr. Lois Mai Chan declared when asked about her greatest achievement in this 2014 video created by the Chinese American Librarians Association (CALA). From 1970 until 2011, Chan influenced hundreds of future catalogers as she taught cataloging at the University of Kentucky (UK) School of Library and Information Science in Lexington. But this wasn’t all she did.

Born on July 30, 1934, in Taiwan, Chan studied foreign languages at National Taiwan University and went on to earn a Master of Arts at Florida State University. In 1966, Chan began working at UK as a serials cataloger. She joined the faculty of the then-UK College of Library Science in 1970, and in 1980 became a full professor after obtaining her Ph.D. in comparative literature at UK.

Dr. Chan had a deep impact on cataloging and classification. Not only did she teach hundreds of future librarians during her forty-five years at UK, but she also wrote over sixty research articles and published over twenty books throughout her career, including the popular textbook Cataloging and Classification: An Introduction, now in its fourth edition. In 1989 she earned the Margaret Mann Citation, “the highest honor in cataloging bestowed by the American Library Association,” which has been given annually since 1951. [We just published a post about Margaret Mann, for whom the citation is named, earlier this month! --ed.] CALA awarded her the CALA Distinguished Service Award in 1992 for outstanding leadership and achievement in library science at the national and/or international level. In 2006 she received the Beta Phi Mu Award for her distinguished service in library education. During her career, she also served as a consultant to the Library of Congress and OCLC’s Faceted Application of Subject Terminology project.

Dr. Chan died on August 20, 2014, but her legacy lives on through the newly-created Lois Mai Chan Professional Development Grant, established by the Cataloging and Metadata Management Section (CaMMS) of the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services (ALCTS) in 2017. The grant seeks to assist library workers from under-represented groups who are new to the metadata field in attending the American Library Association Annual Conference. The UK Lois Mai Chan Enrichment Fund also seeks to honor Chan’s legacy by providing assistance to UK students studying library science.

Dr. Chan may have believed that luck was the reason for her success, but her hard work and passion for library science and teaching are undeniable and inspiring.

Additional sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lois_Mai_Chan

https://web.archive.org/web/20150409034813/https://ci.uky.edu/lis/remembering-lois-mai-chan

http://www.ala.org/news/member-news/2017/04/new-alcts-award-honors-lois-mai-chan

https://uknow.uky.edu/campus-news/library-school-fund-established-honor-retired-professor-lois-chan

#tumblarians#library history#women's history#lois mai chan#catalogers#dr. lois mai chan#library instructors#beta phi mu award#margaret mann citation#women of library history#university of kentucky

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Betty-Carol “BC” Sellen

This post was written by Polly Thistlethwaite, Chief Librarian, The Graduate Center, City University of New York. The photo above, taken by Liz Snyder in 2013, shows BC Sellen and Polly Thistlethwaite in New Orleans.

Betty-Carol “BC” Sellen was born 1934 in Seattle, WA. She is a librarian and a collector of American folk and outsider art and author of several resource books on the subject. She attended the University of Washington for both her Bachelor's (1956) and Master's (1959) degrees, and she earned a second Master's from New York University in 1974. She held positions of increasing responsibility in the profession, starting at the Brooklyn Public Library (1959-60), then with the University of Washington Law Library (1960-63), and finally at the City University of New York Brooklyn College Library from 1964 until her retirement in 1990 as Associate Librarian for Public Services. She resides in Santa Fe, NM, and also spends time in New Orleans, LA.

As a library school student at the University of Washington, Sellen engaged with student government to pressure the university to concern itself with housing for students of color, with particular focus on students from Africa who struggled to find places to live. A media campaign called attention to discriminatory city housing practices and forced the university to support students impacted by them.

Sellen's librarianship provided a platform for wide-ranging activism, gaining particular notoriety for her work on feminist issues in the profession. Sellen was active in the founding of the ALA Social Responsibilities Round Table, a co-founder and 1982-3 chair of the ALA Feminist Task Force, and chair of the Committee on the Status of Women in Librarianship following that.

With a cohort of librarian feminists, she organized an American Library Association Preconference on the Status of Women in Librarianship sponsored by the Social Responsibilities Round Table Task Force on the Status of Women in 1974 at Douglass College, Rutgers University. In the Introduction to the proceedings from that Preconference [1], Sellen describes initial meetings of the group with the incisive directness characteristic of her commentary:

Most of this first meeting was consumed by men telling the women how to improve themselves, and furthermore that what the profession really needed was more men to improve the image. In spite of these helpful suggestions and the scornful attitude of many male SRRT members, who fancied themselves a part of the macho left, where women’s issues were considered frivolous, the women were able to organize together and to become an active and notable presence at ALA conference meetings.

Sellen further explains her cohort’s librarian-focused strategies to “utilize talents and abilities already present among women librarians and not call up experts or ‘big names’ outside the profession” to build professional self-reliance in a likely long-term struggle against systemic oppression.

The preconference generated tangible results: a national survey about union types and priorities; a feminist librarian directory and support network S.H.A.R.E. (Sisters Have Resources Everywhere); a library education resolution presented to ALA membership directing the Committee on Accreditation to practice nondiscrimination in hiring and promotion of library school members; a statement to ALA regarding the Ford Foundation-funded Council on Library Resources to examine grant awarding and promotion practices; a variety of watchdog efforts directed at library schools, the library press, and professional journals; and the recommendation that a daily ‘sexist pig’ award be reported in the ALA Conference Cognotes publication with accompanying instruction about how to make nominations for it. The conference also generated resolutions presented to the ALA for deliberation during the 1974 Annual Conference Meeting in New York City involving accreditation, child care services, position evaluation, sexist terminology, support for affirmative action, terms of administrative appointment, and women in ALA Council positions.

Sellen was also active in New York City library politics. She was President of the Library Association of the City University of New York (LACUNY) [2] during the tumultuous years of 1969 – 71 and co-chair of the 1968 LACUNY Conference [3] New Directions for the City University Libraries that laid the groundwork for the CUNY union catalog and growth of the productive coalition of CUNY libraries. Sellen’s engagement with library politics around the country introduced varieties of library organization, policies, and political concerns into CUNY library activism.

Sellen was engaged in efforts to obtain and to maintain faculty status for CUNY librarians, to match the salaries, benefits, and prestige afforded other university faculty colleagues, achieved in 1965 [4]. In her role as president of the LACUNY Sellen encouraged librarians to publish in scholarly and literary journals as appropriate platforms for librarians’ work. She wrote Librarian/author: A Practical Guide on How to Get Published (Neal-Schuman, 1985) to further that concern.

Sellen was also a defender of academic freedom. When Zoia Horn, librarian at Bucknell College in Lewisburg, PA, was jailed for refusing to turn over library borrowing records regarding the Berrigan brothers (who were imprisoned for anti-American activities) [5], Sellen organized NYC fundraising to support Ms. Horn’s legal defense. [More from WoLH on Zoia Horn here --ed.]

Sellen valued collaboration and often co-authored her academic and professional work on library salaries, alternative careers, and feminist library matters. She was a prodigious author of letters-to-the-editor of library professional publications. She wrote brief, widely-read letters for American Librarians and Library Journal on topics such as librarian faculty status, the sexist underpinnings of the librarian image problem, intellectual freedom in Cuba, sexism and salary discrimination in the library profession, suppression of gay literary identities, and on unacknowledged incidents of censorship. In 1989 she criticized appointment of Fr. Timothy Healey to head the New York Public Library on the grounds that as a CUNY administrator, prior to his NYPL appointment, Healey had systematically undermined librarians and libraries. Sellen remembered publicly that Healey, in a CUNY meeting she attended, announced that “college librarians were about as deserving of faculty status as were campus elevator operators” [6], exposing a cluster of problematic biases held by a man appointed a leading NYC cultural administrator.

In the 1970s, Sellen convinced several other librarians, including Susan Vaughn, Betty Seifert, Joan Marshall, Kay Castle, to take up residence on E. 7th Street in New York City’s East Village. She resided at 248-252 East 7th St. Sellen joined with a multi-ethnic group of residents to rehab neighborhood buildings and establish them as self-governed cooperatives. Sellen was active in the same block association that battled the drug trade that flourished in the neighborhood as early as the 1970s and continued into the 1990s [7].

In 1990 Sellen received the ALA Equality Award, commending her “outstanding contributions toward promoting equality between men and women in the library profession.” The commendation recognizes her tireless labor and sustained coalition building as a leader in several landmark conferences on sex and racial equality, and her “inspiration to several generations of activist librarians.”

Sellen’s eclectic expertise was reflected in her published works. She assembled and edited The Librarian’s Cookbook (1990). She co-authored The Bottom Line Reader: A Financial Handbook for Librarians (1990); The Collection Building Reader (1992) and What Else You Can Do with a Library Degree (1997).

In her retirement, Sellen became an accomplished collector of American folk art. She authored and co-authored several reference books on the topic, including 20th Century American Folk, Self-Taught, and Outsider Art (1993) and Outsider, Self-taught, and Folk Art: Annotated Bibliography (2002) with Cynthia Johanson; Art Centers: American Studios and Galleries for Artists with Developmental or Mental Disabilities (2008); and Self-taught, Outsider and Folk Art: A Guide to American Artists, Locations, and Resources (2016).

Footnotes

1. Marshall, Joan; Sellen, Betty-Carol (1975). Women in a women's profession: strategies: proceedings of the pre-conference on the status of women in librarianship. American Library Association.

2. Schuman, Patricia; Sellen, Betty-Carol (1970). Libraries for the 70s. Queens College, City University of New York.

3. Sellen, Betty-Carol; Karkhanis, Sharad (1968). New Directions for the City University of New York: Papers Presented at an Institute. Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York.

4. Drobnicki, John A. (2014). CUNY Librarians and Faculty Status: Past, Present, and Future. Urban Library Journal 20(1).

5. Horn, Zoia. (1995). Zoia! Memoirs of Zoia Horn, Battler for People’s Right to Know. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

6. Sellen, Betty-Carol. (June, 1989). Healy: Unequivocal Dismay. Library Journal, p. 6.

7. Pais, Josh et al. 7th Street. (2005). Video. Paradise Acres Productions.

#tumblarians#women's history#library history#betty-carol sellen#feminism#bc sellen#lacuny#cuny#new york history#new york city#activists#srrt#ftf#feminist task force#coswl#ala#american library association#preconference on the status of women in librarianship#zoia horn#ala equity award#authors#academic librarians#library activists#community activists#women of library history

16 notes

·

View notes

Link

Librarian and writer Adele Fasick revisits the life of bookseller, publisher, and librarian Elizabeth Peabody, who opened the first American kindergarten.

From her post (which also explains Peabody’s connections ot the Transcendentalists):

We have no picture of Elizabeth Peabody as a young woman, although she was well-known in Boston. As her biographer, Megan Marshall, explains, Elizabeth’s portrait was painted in 1828 by Chester Harding, a well-known portrait artist in Boston. Elizabeth was 24 years old at the time and teaching at a school she had started for girls. Instead of being pleased by the portrait, her parents were scandalized. Women of that time did not have pictures of themselves mounted on walls and displayed to others. Unlike men, women were supposed to live lives that were private and hidden from everyone except their families. Despite the prevailing customs, however, Elizabeth was destined to become a well-known figure in Boston and elsewhere during her long life.

#tumblarians#women's history#library history#elizabeth peabody#boston history#massachusetts history#boston librarians#transcendental club#women of library history

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caroline M. Hewins

Bridget Quinn-Carey, CEO of Hartford Public Library, submitted today’s post.

The image above is part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Library and Information Studies Collection.

In 1882, Caroline M. Hewins had been a librarian in Hartford for only six years when, through a fledgling group called the American Library Association, she sent a questionnaire to twenty-five libraries around the country and asked: “What are you doing to encourage a love of reading in boys and girls?” (Hog River Journal, Vol 5, No. 3, Summer 2007, “Hartford’s First Lady of the Library,” page 28.) A devoted reader since early childhood, Bostonian Hewins came to Hartford in 1876 to serve as the librarian of the Young Men’s Institute Library, then housed at the Wadsworth Atheneum and a precursor to what became the Hartford Public Library. She stayed with the library for the next fifty years, and oversaw its transformation from a small lending library that charged fees into the free Hartford Public Library, complete with its own flagship facility including a room for children.

She came from a wealthy and cultured home where books had been her magic carpet, and she wanted them to be available to children at every economic level. The Institute Library had not welcomed children, but Hewins quickly changed that, and gathered together books by Grimm, Andersen, Hawthorne, Thackeray and Dickens to furnish a corner for children. She used the power of the local press and professional library periodicals to encourage parents to bring their children to libraries, to read with them, and to choose quality books that would inspire the young imagination. The same year that she sent out the questionnaire, she published a nationally available bibliography of children’s books she loved and thought valuable. During the time when a paid subscription to the library was $3 a year to borrow one book at a time, Hewins worked with local Hartford schools to encourage subscription cards for the children, at pennies per card.

By the time the library became a free service in 1892, Hewins had already lowered the annual subscription fee to $1 and doubled the membership. Opinionated, iconoclastic and not a follower of rules others had established, she believed that children deserved better books than the formulaic and often violent Horatio Alger stories and weekly novels of the penny press. The Children’s Room she established had furniture suitable for different ages of children, pictures of flowers, lots of light and a resident dog the children had helped name. When she was not working at the library or writing for a national audience about the need for books and library settings appropriate to children, Hewins traveled. On her many trips, she wrote letters home to the children of Hartford, which the local newspapers published, and she shopped for books and dolls which she brought back to the library and shared with the children.

She collected books to be used in city classrooms, and made the library a place for book groups, theatrical skits, exhibits for parents and parties. By building connections between local school schools and the library, and between the library and the urban poor, as well as encouraging children reading for pleasure, Caroline Hewins anticipated by more than a century the common practices of today. She promoted library branches and believed that if the poor could not come to the books, the books should come to them.

Hartford Public Library’s Hartford History Center is home to her collection of more than 150 dolls, originals of some of the letters she wrote to Hartford children from Europe, correspondence and newspaper clippings, and the large collection of European and American nineteenth- and twentieth-century children’s books she acquired for the library. Scholar Leonard S. Marcus guest curated a popular Hartford History Center exhibition (December 2009 to April 2010) of fifty of Miss Hewins’s books, and is one of the nation’s leading authorities on children’s literature wrote in the accompanying catalog, “The fine collection…sampled throughout this exhibition bears witness to the adventurous spirit that powered her innovative life’s work.” (footnote page 1, catalog of exhibit.)

#tumblarians#women's studies#library history#caroline hewins#hartford public library#connecticut history#young men's institute library#children's librarians#youth services librarians#american library association#women of library history

16 notes

·

View notes