#farmer adoption of technology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why Kenya's Agritech Startups Struggle to Penetrate the Market Despite Strong Investment

Discover why Kenya’s agritech startups struggle with market penetration despite strong investment, and explore how regulatory challenges and fragmented services hinder growth in the sector. Kenya’s agritech industry faces hurdles beyond funding, including complex regulations and data security concerns. Learn how startups can overcome these challenges to scale and succeed. Uncover the key barriers…

#agricultural technology Kenya#agritech ecosystem#agritech innovation challenges#agritech investment Kenya#agritech market penetration#agritech partnerships#Agritech Startups#AI in farming#climate resilience farming#data privacy in agriculture#data security agritech.#digital agricultural transformation#digital farming tools#digital financial services for farmers#farmer adoption of technology#fragmented service providers#IoT in agritech#Kenya agritech challenges#Kenya’s digital ecosystem#Mercy Corps AgriFin#public sector data in agriculture#regulatory barriers agritech#small-scale farming Kenya#smart farming Kenya#stakeholder engagement in agritech#sustainable agriculture Kenya#tech solutions for farmers#technology adoption barriers#technology-driven agriculture

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

#Here’s a **YouTube video description** tailored to your agricultural video:#---#**Description:**#Welcome to our video on **empowering Indian farmers**! 🌾#In this video#we explore the **future of farming in India**#focusing on **sustainable practices**#**water conservation techniques**#and the **latest agricultural technologies** that can help you boost productivity and protect the environment. We’ll also highlight **gover#making it easier to adopt new tools and methods for growing better crops.#🚜 **What You’ll Learn:**#- How to implement **sustainable farming practices** like crop rotation#organic farming#and natural pest management.#- The importance of **water conservation** and how technologies like **drip irrigation** and **rainwater harvesting** can make a huge diffe#- How **technology** can transform your farm with tools like **mobile apps**#**drones**#and smart sensors to monitor crop health and improve yields.#- **Government schemes and subsidies** that can help you invest in new technologies and improve your farm’s output.#Whether you’re a seasoned farmer or new to agriculture#this video will provide valuable insights and tips to help you grow your farm sustainably and increase your income. Together#we can create a **brighter future for Indian agriculture**!#🌱 **Stay tuned and subscribe** for more tips on modern farming and how to make your farm more efficient and profitable.#**#SustainableFarming#IndianFarmers#WaterConservation#AgriTech#FarmingTips#IndianAgriculture

1 note

·

View note

Text

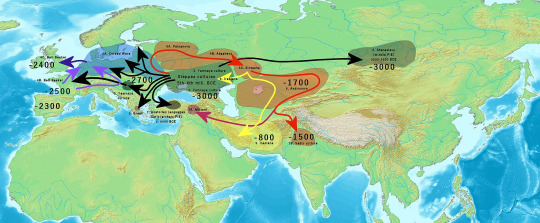

finally watched barbie last night. i think it was refreshing to see gerwig's exploration of population exchange in europe during the chalcolithic age. barbies are clearly coded to be early european farmers, living in a comfortable yet stagnant environment of europe at the tail end of the ice age, with a culture revolving around female fertility (notice the second character introduced is a pregnant barbie). the second sequence shows up ken(gosling)'s enterance into the story on beach, mirroring the arrival of western steppe herder cultures as glaciers in europe retreated.

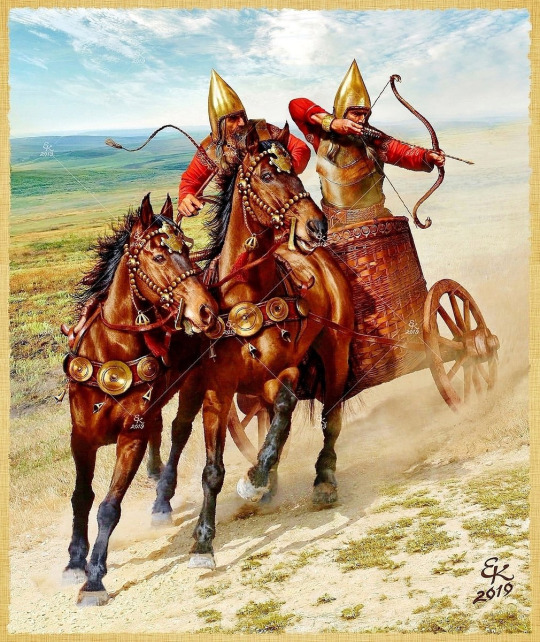

once barbie and ken venture into the "real world" (prohpetic vision of the bronze age), ken adopts advanced technologies like the horse (horse), patriatrchy (worship of a male solar deity), and cars (the wheel, expoundable into the horse-driven chariot). his donning of the fringe jacket and cowboy hat stir within the audience a yearning for westward expansion, from the pontic steppe through the pannonian basin and beyond.

ken transforming barbieland into the kendom mirrors the replacement of early european farmer (vinča, varna cultures etc.) with corded ware and bell beaker cultures, settled iterations of the kens' previously pastoral culture. the only barbie not assimilated into the new cultral zeitgeist is weird barbie (basques), herself a cultural isolate even compared to other barbies pre-invasion.

the final battle scene between the two ken factions places particular focus on archery, hallmark of the mongol civilization, which was the last of the steppe invasions of europe. notice in this situation, gerwig's bravery in correctly having ken (asian) represent the kingdom of hungary (asian), whereas ken (gosling) is of course the ever-lasting scythian spirit emanating from the steppe. some scholars have suggested the light-blue void where the last battle takes place to be a metaphor tengri.

some other stuff happened as well but i didn't really get how that fit into the greater story i guess. what was the deal with the old jewish lady LOL !

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

some of my six of crows modern headcanons xx

nina and inej are taylor swift and phoebe bridgers best friends

inej is vegan and i will not be explaining myself

matthias’ snapchat username is matthiashelvqr but jesper’s is animal_loverjes123 because he made it when he was nine

wylan is scared of planes but not helicopters

jesper is scared of helicopters but not planes

nina and inej listened to midnights together when it was first released

jesper got matthias into star wars

jesper loves the prequels and clone wars, matthias prefers the original trilogy and rogue one

both nina and jespers first bi panic was watching pirates of the caribbean

kaz has a secret fear of escalators so he always takes the stairs even though it actively causes him more pain

kaz and wylan watch criminal minds together in silence, but they both say the line about tracy lambert together

matthias falls asleep to animal documentaries narrated by david attenborough

inej jesper and nina are big greys anatomy fans

wylan’s first crush was teenage simba

matthias plays rugby

they have a book club (audiobook for wylan)

they read the acotar series and all had vastly different opinions

nina was an avid zoella watcher

kaz doesnt pay for any streaming services but has all of them anyway, jesper also doesn’t pay but uses everyone elses

matthias pays for the netflix account though

him and nina share one profile and everyone else has their own profile

nina cried when they took new girl off netflix

kaz says he prefers dc over marvel just to cause conflict

jesper read percy jackson growing up and still has the same battered copies he read as a kid in his room no matter where he lives

nina was a harry potter reading child and also still has her original copies of the books

HARRY POTTER REWATCH MOVIE NIGHTS!!!!

wylan is a secret marauders stan

nina jesper inej and wylan are all marauders era fans but wylan is soooo much worse

wesper = wolfstar

jesper’s favourite movie is the breakfast club

kaz says his favourite movie is fight club but it’s actually fantastic mr fox

kaz follows six people on instagram: inej and all the members of one direction

he does that to piss the others off

jesper went viral on tik tok one time

matthias loves oasis (both the band and the drink)

nina fought for eras tour tickets and managed to get them all tickets

kaz is going as reputation (his usual attire) jesper as lover, wylan as evermore, inej as speak now (she got the speak now dress), matthias as debut (they got him a cowboy hat) and nina as red.

matthias secretly cried over the how to train your dragon ending

matthias and inej read a lot of classics and share their collection, they both annotate the books as well and enjoy seeing what the other has written

kaz has a do not disturb sign on his bedroom door like in a hotel and puts it on the door handle even when he’s not in there

kaz is weirdly good with technology

jesper collects mugs

kaz and inej steal pint glasses from pubs

when inej and nina listened nothing new on red(tv) they lost their minds

kaz loves boygenius

matthias and wylan love modern family, wylan’s favourite character is gloria and matthias’ is jay

jesper loves formula 1 and its the only sport he’ll watch

nina and matthias play animal crossing together

kaz terrors jesper on terraria

when they play minecraft functionally, inej is the builder, jesper is the farmer, matthias and wylan mine, kaz has netherite armour in like half an hour and nina collects flowers and tames animals

when they play minecraft disfunctionally they just blow shit up

kaz plays the guitar

inej DEVOURED the cruel prince series

zoya and genya are nina’s foster/adoptive sisters

wylan is scared of clowns and is like that one episode of new girl when nick has to go into the haunted house

whenever jesper does something stupid or doesnt do something or whatever he says ‘#yolo’ and moves on and it drives kaz insane

jesper has muggies of everyone

inej takes 0.5 pictures of everyone when theyre sleeping without them knowing

matthias loves the hunger games series

kaz regularly predicts major global events

wylan loves breaking bad

#six of crows#six of crows headcanons#six of crows spin off#PLEASE#nina zenik#inej ghafa#kaz brekker#wylan van eck#jesper fahey#jesper llewellyn fahey#matthias helvar#helnik#kanej#wesper#shadow and bone#shadow and bone season 2#shadow and bone cast#spin off pls#zoya nazyalensky#genya safin#modern au#modern six of crows#six of crows modern au#soc

499 notes

·

View notes

Text

Innovative business models for small scale solar powered irrigation

If rolled out at scale, solar-powered irrigation systems hold huge potential. They work for smallholder farmers, who account for 80% of sub-Saharan Africa’s farms, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. But they also displace expensive and polluting diesel pumps and can, if managed correctly, contribute to efforts to manage scarce water resources well for the long term.

Chiefly, there is the issue of affordability. Farmers need to be able to pay the upfront cost of a solar-powered irrigation system and to pay for the duration of its use. When compared with the diesel-fueled irrigation pumps many farmers use today, the total lifetime cost of solar powered irrigation systems can be substantially lower. We estimate farmers can save 40% to 60% on irrigation costs.

As we see across the off-grid solar sector, adopting a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) approach – or, in our case, pay-as-you-grow – has the benefit of allowing farmers to pay for their systems over time, as their income increases due to better harvests.

Moving on from affordability, maintenance is the next key challenge, particularly in remote and rural areas where farms can be hard to reach and the availability of trained technicians is limited. By managing the lifecycle of pumps from design through manufacture, finance, installation, and maintenance, companies can work with farmers to ensure that pumps are able to continue to function in often challenging local conditions, season after season.

Internet-of-things (IoT)-enabled technology enables trained teams to monitor pump performance and conduct maintenance remotely. This is complemented by strategically located sales and service centers and a distributed team of field engineers able to rapidly respond to maintenance issues, expand local capacity and minimize downtime for farmers reliant on irrigation for successful harvests.

Again, solar-powered irrigation has an advantage over diesel pumps in that their fuel source is abundant and locally available. Fewer moving parts also make solar-powered irrigation systems less liable to break down than their diesel counterparts.

Source

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.5 What about the lack of enclosures in the Americas?

The enclosure movement was but one part of a wide-reaching process of state intervention in creating capitalism. Moreover, it is just one way of creating the “land monopoly” which ensured the creation of a working class. The circumstances facing the ruling class in the Americas were distinctly different than in the Old World and so the “land monopoly” took a different form there. In the Americas, enclosures were unimportant as customary land rights did not really exist (at least once the Native Americans were eliminated by violence). Here the problem was that (after the original users of the land were eliminated) there were vast tracts of land available for people to use. Other forms of state intervention were similar to that applied under mercantilism in Europe (such as tariffs, government spending, use of unfree labour and state repression of workers and their organisations and so on). All had one aim, to enrich and power the masters and dispossess the actual producers of the means of life (land and means of production).

Unsurprisingly, due to the abundance of land, there was a movement towards independent farming in the early years of the American colonies and subsequent Republic and this pushed up the price of remaining labour on the market by reducing the supply. Capitalists found it difficult to find workers willing to work for them at wages low enough to provide them with sufficient profits. It was due to the difficulty in finding cheap enough labour that capitalists in America turned to slavery. All things being equal, wage labour is more productive than slavery but in early America all things were not equal. Having access to cheap (indeed, free) land meant that working people had a choice, and few desired to become wage slaves and so because of this, capitalists turned to slavery in the South and the “land monopoly” in the North.

This was because, in the words of Maurice Dobb, it “became clear to those who wished to reproduce capitalist relations of production in the new country that the foundation-stone of their endeavour must be the restriction of land-ownership to a minority and the exclusion of the majority from any share in [productive] property.” [Studies in Capitalist Development, pp. 221–2] As one radical historian puts it, ”[w]hen land is ‘free’ or ‘cheap’. as it was in different regions of the United States before the 1830s, there was no compulsion for farmers to introduce labour-saving technology. As a result, ‘independent household production’ … hindered the development of capitalism … [by] allowing large portions of the population to escape wage labour.” [Charlie Post, “The ‘Agricultural Revolution’ in the United States”, pp. 216–228, Science and Society, vol. 61, no. 2, p. 221]

It was precisely this option (i.e. of independent production) that had to be destroyed in order for capitalist industry to develop. The state had to violate the holy laws of “supply and demand” by controlling the access to land in order to ensure the normal workings of “supply and demand” in the labour market (i.e. that the bargaining position favoured employer over employee). Once this situation became the typical one (i.e., when the option of self-employment was effectively eliminated) a more (protectionist based) “laissez-faire” approach could be adopted, with state action used indirectly to favour the capitalists and landlords (and readily available to protect private property from the actions of the dispossessed).

So how was this transformation of land ownership achieved?

Instead of allowing settlers to appropriate their own farms as was often the case before the 1830s, the state stepped in once the army had cleared out (usually by genocide) the original users. Its first major role was to enforce legal rights of property on unused land. Land stolen from the Native Americans was sold at auction to the highest bidders, namely speculators, who then sold it on to farmers. This process started right “after the revolution, [when] huge sections of land were bought up by rich speculators” and their claims supported by the law. [Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 125] Thus land which should have been free was sold to land-hungry farmers and the few enriched themselves at the expense of the many. Not only did this increase inequality within society, it also encouraged the development of wage labour — having to pay for land would have ensured that many immigrants remained on the East Coast until they had enough money. Thus a pool of people with little option but to sell their labour was increased due to state protection of unoccupied land. That the land usually ended up in the hands of farmers did not (could not) countermand the shift in class forces that this policy created.

This was also the essential role of the various “Homesteading Acts” and, in general, the “Federal land law in the 19th century provided for the sale of most of the public domain at public auction to the higher bidder … Actual settlers were forced to buy land from speculators, at prices considerably above the federal minimal price.” (which few people could afford anyway). [Charlie Post, Op. Cit., p. 222] This is confirmed by Howard Zinn who notes that 1862 Homestead Act “gave 160 acres of western land, unoccupied and publicly owned, to anyone who would cultivate it for five years … Few ordinary people had the $200 necessary to do this; speculators moved in and bought up much of the land. Homestead land added up to 50 million acres. But during the Civil War, over 100 million acres were given by Congress and the President to various railroads, free of charge.” [Op. Cit., p. 233] Little wonder the Individualist Anarchists supported an “occupancy and use” system of land ownership as a key way of stopping capitalist and landlord usury as well as the development of capitalism itself.

This change in the appropriation of land had significant effects on agriculture and the desirability of taking up farming for immigrants. As Post notes, ”[w]hen the social conditions for obtaining and maintaining possession of land change, as they did in the Midwest between 1830 and 1840, pursuing the goal of preserving [family ownership and control] .. . produced very different results. In order to pay growing mortgages, debts and taxes, family farmers were compelled to specialise production toward cash crops and to market more and more of their output.” [Op. Cit., p. 221–2]

So, in order to pay for land which was formerly free, farmers got themselves into debt and increasingly turned to the market to pay it off. Thus, the “Federal land system, by transforming land into a commodity and stimulating land speculation, made the Midwestern farmers dependent upon markets for the continual possession of their farms.” Once on the market, farmers had to invest in new machinery and this also got them into debt. In the face of a bad harvest or market glut, they could not repay their loans and their farms had to be sold to so do so. By 1880, 25% of all farms were rented by tenants, and the numbers kept rising. In addition, the “transformation of social property relations in northern agriculture set the stage for the ‘agricultural revolution’ of the 1840s and 1850s … [R]ising debts and taxes forced Midwestern family farmers to compete as commodity producers in order to maintain their land-holding … The transformation … was the central precondition for the development of industrial capitalism in the United States.” [Charlie Post, Op. Cit., p. 223 and p. 226]

It should be noted that feudal land owning was enforced in many areas of the colonies and the early Republic. Landlords had their holdings protected by the state and their demands for rent had the full backing of the state. This lead to numerous anti-rent conflicts. [Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 84 and pp. 206–11] Such struggles helped end such arrangements, with landlords being “encouraged” to allow the farmers to buy the land which was rightfully theirs. The wealth appropriated from the farmers in the form of rent and the price of the land could then be invested in industry so transforming feudal relations on the land into capitalist relations in industry (and, eventually, back on the land when the farmers succumbed to the pressures of the capitalist market and debt forced them to sell).

This means that Murray Rothbard’s comment that “once the land was purchased by the settler, the injustice disappeared” is nonsense — the injustice was transmitted to other parts of society and this, the wider legacy of the original injustice, lived on and helped transform society towards capitalism. In addition, his comment about “the establishment in North America of a truly libertarian land system” would be one the Individualist Anarchists of the period would have seriously disagreed with! [The Ethics of Liberty, p. 73] Rothbard, at times, seems to be vaguely aware of the importance of land as the basis of freedom in early America. For example, he notes in passing that “the abundance of fertile virgin land in a vast territory enabled individualism to come to full flower in many areas.” [Conceived in Liberty, vol. 2, p. 186] Yet he did not ponder the transformation in social relationships which would result when that land was gone. In fact, he was blasé about it. “If latecomers are worse off,” he opined, “well then that is their proper assumption of risk in this free and uncertain world. There is no longer a vast frontier in the United States, and there is no point crying over the fact.” [The Ethics of Liberty, p. 240] Unsurprisingly we also find Murray Rothbard commenting that Native Americans “lived under a collectivistic regime that, for land allocation, was scarcely more just than the English governmental land grab.” [Conceived in Liberty, vol. 1, p. 187] That such a regime made for increased individual liberty and that it was precisely the independence from the landlord and bosses this produced which made enclosure and state land grabs such appealing prospects for the ruling class was lost on him.

Unlike capitalist economists, politicians and bosses at the time, Rothbard seemed unaware that this “vast frontier” (like the commons) was viewed as a major problem for maintaining labour discipline and appropriate state action was taken to reduce it by restricting free access to the land in order to ensure that workers were dependent on wage labour. Many early economists recognised this and advocated such action. Edward Wakefield was typical when he complained that “where land is cheap and all are free, where every one who so pleases can easily obtain a piece of land for himself, not only is labour dear, as respects the labourer’s share of the product, but the difficulty is to obtain combined labour at any price.” This resulted in a situation were few “can accumulate great masses of wealth” as workers “cease … to be labourers for hire; they … become independent landowners, if not competitors with their former masters in the labour market.” Unsurprisingly, Wakefield urged state action to reduce this option and ensure that labour become cheap as workers had little choice but to seek a master. One key way was for the state to seize the land and then sell it to the population. This would ensure that “no labourer would be able to procure land until he had worked for money” and this “would produce capital for the employment of more labourers.” [quoted by Marx, Op. Cit., , p. 935, p. 936 and p. 939] Which is precisely what did occur.

At the same time that it excluded the working class from virgin land, the state granted large tracts of land to the privileged classes: to land speculators, logging and mining companies, planters, railroads, and so on. In addition to seizing the land and distributing it in such a way as to benefit capitalist industry, the “government played its part in helping the bankers and hurting the farmers; it kept the amount of money — based in the gold supply — steady while the population rose, so there was less and less money in circulation. The farmer had to pay off his debts in dollars that were harder to get. The bankers, getting loans back, were getting dollars worth more than when they loaned them out — a kind of interest on top of interest. That was why so much of the talk of farmers’ movements in those days had to do with putting more money in circulation.” [Zinn, Op. Cit., p. 278] This was the case with the Individualist Anarchists at the same time, we must add.

Overall, therefore, state action ensured the transformation of America from a society of independent workers to a capitalist one. By creating and enforcing the “land monopoly” (of which state ownership of unoccupied land and its enforcement of landlord rights were the most important) the state ensured that the balance of class forces tipped in favour of the capitalist class. By removing the option of farming your own land, the US government created its own form of enclosure and the creation of a landless workforce with little option but to sell its liberty on the “free market”. They was nothing “natural” about it. Little wonder the Individualist Anarchist J.K. Ingalls attacked the “land monopoly” with the following words:

“The earth, with its vast resources of mineral wealth, its spontaneous productions and its fertile soil, the free gift of God and the common patrimony of mankind, has for long centuries been held in the grasp of one set of oppressors by right of conquest or right of discovery; and it is now held by another, through the right of purchase from them. All of man’s natural possessions … have been claimed as property; nor has man himself escaped the insatiate jaws of greed. The invasion of his rights and possessions has resulted … in clothing property with a power to accumulate an income.” [quoted by James Martin, Men Against the State, p. 142]

Marx, correctly, argued that “the capitalist mode of production and accumulation, and therefore capitalist private property, have for their fundamental condition the annihilation of that private property which rests on the labour of the individual himself; in other words, the expropriation of the worker.” [Capital, Vol. 1, p. 940] He noted that to achieve this, the state is used:

“How then can the anti-capitalistic cancer of the colonies be healed? . .. Let the Government set an artificial price on the virgin soil, a price independent of the law of supply and demand, a price that compels the immigrant to work a long time for wages before he can earn enough money to buy land, and turn himself into an independent farmer.” [Op. Cit., p. 938]

Moreover, tariffs were introduced with “the objective of manufacturing capitalists artificially��� for the “system of protection was an artificial means of manufacturing manufacturers, or expropriating independent workers, of capitalising the national means of production and subsistence, and of forcibly cutting short the transition … to the modern mode of production,” to capitalism [Op. Cit., p. 932 and pp. 921–2]

So mercantilism, state aid in capitalist development, was also seen in the United States of America. As Edward Herman points out, the “level of government involvement in business in the United States from the late eighteenth century to the present has followed a U-shaped pattern: There was extensive government intervention in the pre-Civil War period (major subsidies, joint ventures with active government participation and direct government production), then a quasi-laissez faire period between the Civil War and the end of the nineteenth century [a period marked by “the aggressive use of tariff protection” and state supported railway construction, a key factor in capitalist expansion in the USA], followed by a gradual upswing of government intervention in the twentieth century, which accelerated after 1930.” [Corporate Control, Corporate Power, p. 162]

Such intervention ensured that income was transferred from workers to capitalists. Under state protection, America industrialised by forcing the consumer to enrich the capitalists and increase their capital stock. “According to one study, if the tariff had been removed in the 1830s ‘about half the industrial sector of New England would have been bankrupted’ … the tariff became a near-permanent political institution representing government assistance to manufacturing. It kept price levels from being driven down by foreign competition and thereby shifted the distribution of income in favour of owners of industrial property to the disadvantage of workers and customers.” This protection was essential, for the “end of the European wars in 1814 … reopened the United States to a flood of British imports that drove many American competitors out of business. Large portions of the newly expanded manufacturing base were wiped out, bringing a decade of near-stagnation.” Unsurprisingly, the “era of protectionism began in 1816, with northern agitation for higher tariffs.” [Richard B. Du Boff, Accumulation and Power, p. 56, p. 14 and p. 55] Combined with ready repression of the labour movement and government “homesteading” acts (see section F.8.5), tariffs were the American equivalent of mercantilism (which, after all, was above all else a policy of protectionism, i.e. the use of government to stimulate the growth of native industry). Only once America was at the top of the economic pile did it renounce state intervention (just as Britain did, we must note).

This is not to suggest that government aid was limited to tariffs. The state played a key role in the development of industry and manufacturing. As John Zerzan notes, the “role of the State is tellingly reflected by the fact that the ‘armoury system’ now rivals the older ‘American system of manufactures’ term as the more accurate to describe the new system of production methods” developed in the early 1800s. [Elements of Refusal, p. 100] By the middle of the nineteenth century “a distinctive ‘American system of manufactures’ had emerged . .. The lead in technological innovation [during the US Industrial Revolution] came in armaments where assured government orders justified high fixed-cost investments in special-pursue machinery and managerial personnel. Indeed, some of the pioneering effects occurred in government-owned armouries.” Other forms of state aid were used, for example the textile industry “still required tariffs to protect [it] from … British competition.” [William Lazonick, Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, p. 218 and p. 219] The government also “actively furthered this process [of ‘commercial revolution’] with public works in transportation and communication.” In addition to this “physical” aid, “state government provided critical help, with devices like the chartered corporation” [Richard B. Du Boff, Op. Cit., p. 15] As we noted in section B.2.5, there were changes in the legal system which favoured capitalist interests over the rest of society.

Nineteenth-century America also went in heavily for industrial planning — occasionally under that name but more often in the name of national defence. The military was the excuse for what is today termed rebuilding infrastructure, picking winners, promoting research, and co-ordinating industrial growth (as it still is, we should add). As Richard B. Du Boff points out, the “anti-state” backlash of the 1840s onwards in America was highly selective, as the general opinion was that ”[h]enceforth, if governments wished to subsidise private business operations, there would be no objection. But if public power were to be used to control business actions or if the public sector were to undertake economic initiatives on its own, it would run up against the determined opposition of private capital.” [Op. Cit., p. 26]

State intervention was not limited to simply reducing the amount of available land or enforcing a high tariff. “Given the independent spirit of workers in the colonies, capital understood that great profits required the use of unfree labour.” [Michael Perelman, The Invention of Capitalism, p. 246] It was also applied in the labour market as well. Most obviously, it enforced the property rights of slave owners (until the civil war, produced when the pro-free trade policies of the South clashed with the pro-tariff desires of the capitalist North). The evil and horrors of slavery are well documented, as is its key role in building capitalism in America and elsewhere so we will concentrate on other forms of obviously unfree labour. Convict labour in Australia, for example, played an important role in the early days of colonisation while in America indentured servants played a similar role.

Indentured service was a system whereby workers had to labour for a specific number of years usually in return for passage to America with the law requiring the return of runaway servants. In theory, of course, the person was only selling their labour. In practice, indentured servants were basically slaves and the courts enforced the laws that made it so. The treatment of servants was harsh and often as brutal as that inflicted on slaves. Half the servants died in the first two years and unsurprisingly, runaways were frequent. The courts realised this was a problem and started to demand that everyone have identification and travel papers.

It should also be noted that the practice of indentured servants also shows how state intervention in one country can impact on others. This is because people were willing to endure indentured service in the colonies because of how bad their situation was at home. Thus the effects of primitive accumulation in Britain impacted on the development of America as most indentured servants were recruited from the growing number of unemployed people in urban areas there. Dispossessed from their land and unable to find work in the cities, many became indentured servants in order to take passage to the Americas. In fact, between one half to two thirds of all immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants and, at times, three-quarters of the population of some colonies were under contracts of indenture. That this allowed the employing class to overcome their problems in hiring “help” should go without saying, as should its impact on American inequality and the ability of capitalists and landlords to enrich themselves on their servants labour and to invest it profitably.

As well as allowing unfree labour, the American state intervened to ensure that the freedom of wage workers was limited in similar ways as we indicated in section F.8.3. “The changes in social relations of production in artisan trades that took place in the thirty years after 1790,” notes one historian, “and the … trade unionism to which … it gave rise, both replicated in important respects the experience of workers in the artisan trades in Britain over a rather longer period … The juridical responses they provoked likewise reproduced English practice. Beginning in 1806, American courts consciously seized upon English common law precedent to combat journeymen’s associations.” Capitalists in this era tried to “secure profit … through the exercise of disciplinary power over their employees.” To achieve this “employers made a bid for legal aid” and it is here “that the key to law’s role in the process of creating an industrial economy in America lies.” As in the UK, the state invented laws and issues proclamations against workers’ combinations, calling them conspiracies and prosecuting them as such. Trade unionists argued that laws which declared unions as illegal combinations should be repealed as against the Constitution of the USA while “the specific cause of trademens protestations of their right to organise was, unsurprisingly, the willingness of local authorities to renew their resort to conspiracy indictments to countermand the growing power of the union movement.” Using criminal conspiracy to counter combinations among employees was commonplace, with the law viewing a “collective quitting of employment [as] a criminal interference” and combinations to raise the rate of labour “indictable at common law.” [Christopher L. Tomlins, Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic, p. 113, p. 295, p. 159 and p. 213] By the end of the nineteenth century, state repression for conspiracy was replaced by state repression for acting like a trust while actual trusts were ignored and so laws, ostensibly passed (with the help of the unions themselves) to limit the power of capital, were turned against labour (this should be unsurprising as it was a capitalist state which passed them). [Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 254]

Another key means to limit the freedom of workers was denying departing workers their wages for the part of the contract they had completed. This “underscored the judiciary’s tendency to articulate their approval” of the hierarchical master/servant relationship in terms of its “social utility: It was a necessary and desirable feature of the social organisation of work … that the employer’s authority be reinforced in this way.” Appeals courts held that “an employment contract was an entire contract, and therefore that no obligation to pay wages existed until the employee had completed the agreed term.” Law suits “by employers seeking damages for an employee’s departure prior to the expiry of an agreed term or for other forms of breach of contract constituted one form of legally sanctioned economic discipline of some importance in shaping the employment relations of the nineteenth century.” Thus the boss could fire the worker without paying their wages while if the worker left the boss he would expect a similar outcome. This was because the courts had decided that the “employer was entitled not only to receipt of the services contracted for in their entirety prior to payment but also to the obedience of the employee in the process of rendering them.” [Tomlins, Op. Cit., pp. 278–9, p. 274, p. 272 and pp. 279–80] The ability of workers to seek self-employment on the farm or workplace or even better conditions and wages were simply abolished by employers turning to the state.

So, in summary, the state could remedy the shortage of cheap wage labour by controlling access to the land, repressing trade unions as conspiracies or trusts and ensuring that workers had to obey their bosses for the full term of their contract (while the bosses could fire them at will). Combine this with the extensive use of tariffs, state funding of industry and infrastructure among many other forms of state aid to capitalists and we have a situation were capitalism was imposed on a pre-capitalist nation at the behest of the wealthy elite by the state, as was the case with all other countries.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking ahead 20 years, many farmers will have to take land out of agriculture to comply with the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), 2014 legislation that has required counties to implement groundwater management plans throughout California. As a result of SGMA, AFT estimates 4 percent, or 212,000 acres, of cropland in the San Joaquin Valley alone could be permanently retired and 27 percent intermittently fallow. Conservation groups hope to see some of that land become part of corridors for native plants, waterways, and wildlife, but farmers are also looking to agrivoltaics opportunities.

Agrivoltaics may also help conserve water. “The shade that is created by the solar panels, in areas that receive more sun than plants need for their photosynthesis, reduces the heat stress on those crops, makes them healthier, and makes them require less water,” Abou Najm said. “Agrivoltaics is more than just a dual production of food and energy on the same plot of land—it maximizes the synergy between the two.”

Agrivoltaics stand to assist Central Valley farms in myriad ways, said Dahlquist-Willard. Larger farms that adopt agrivoltaics could potentially benefit smaller ones by alleviating pressure on regional groundwater. At the same time, farmers with less land are more likely to consider agrivoltaics than converting entirely to solar. “For a small farm—say 10, 20, 30 acres—if you convert your whole farm to solar, you’re quitting farming. Nobody does that when farming is their only source of income,” she said.

Abou Najm published a theoretical study looking at how to grow crops—including lettuce, basil, and strawberries—under solar panels in a way that maximized productivity. He found that the blue part of the light spectrum is best filtered out to produce solar energy, while the red spectrum can be optimized to grow food; this requires a specific type of panel that’s less common but available. His follow-up research involves expanding the types of crops and conducting field trials.

U.C. Davis is filling a necessary gap in California research, though many other studies have been conducted nationally and internationally documenting crop yields under panels. Scientists have found agrivoltaics can improve the efficiency of the panels, and increase water-use efficiency, soil moisture content, and crop yields. In one cherry tomato study, production doubled under the panels and water-use efficiency was 65 percent greater.

Researchers from California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo are also documenting the benefits of grazing under solar panels in California, supporting research worldwide. They are studying the benefits of sheep grazing on two solar installations, Gold Tree Farm and Topaz Solar Farm. There, they’ve found that the solar arrays can offer synergistic benefits for the sheep and the grasslands. Compared with pastures outside the solar panels, the shaded grasses have higher water content, greater nitrogen content, and lower non-digestible fiber.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

OC Masterpost

hihi! having to redo this because my previous one got borked, and posting it publicly so that i can link it easier without redirect issues (^^ゞ y'know how tumblr is, etc etc.

warning: this post is very long and has multiple images! (and speaking of those images, this site was used to create the tokens seen below.)

◈ Elder Scrolls

Rildras Moon-and-Star

Male, he/him

Dunmer

The Nerevarine, Nerevar reborn

Father of Vedyra, grandfather of Vedathyr, son of Nedrala and Azura

Former husband of Dagoth Ur

Husband of Voralen

May be a demiprince, but hates the daedra (and admittedly also the aedra) with all his heart

Sword warrior and destruction caster

Retired to a life of being a mushroom farmer after raising his daughter to adulthood

#oc moon and star (tag is attached to post)

Dagoth Vedyra

Female, she/her

Dunmer

Scion of House Dagoth and Founder of the reborn House Dagoth

Daughter of Rildras and Dagoth Ur, mother of Vedathyr and Strides-Through-Ashes, granddaughter of Nedrala and Azura

Arcanist

Scholar with a focus on the dwemer, especially their disappearance

#oc vedyra (tag is attached to post)

Dagoth Vedathyr

Male, he/him

Dunmer

Heir to House Dagoth

The Last Dragonborn

Member (not the leader!) of the Companions, werewolf

Dual-handed warrior

Son of Vedyra, grandson of Rildras and Dagoth ur, great-grandson of Nedrala and Azura

Mercenary much to his pleasure, legendary figure of history much to his displeasure

#oc vedathyr (tag is attached to post)

Voryn Voralen

Male, he/him

Dunmer

The Sharmat, Voryn Dagoth reborn

Father of Vedyra, grandfather of Vedathyr

Husband of Moon-and-Star

#oc voralen (tag is attached to post)

Nedrala

Female, she/her

Dunmer

Ashlander exile from the Urshilaku Tribe

Former consort and chosen of Azura

Potter by trade

Mother of Rildras, grandmother of Vedyra, great-grandmother of Vedathyr

No tag yet

Strides-Through-Ashes | Dagoth Nehota

Female, she/her

Argonian

Found by Vedyra as an abandoned egg

Shadowscale aspirant, assassin

Adopted daughter of Vedyra, biological parents unknown

Member of House Dagoth

No tag yet

Dagoth Tsabi

Female, she/her

Khajiit

Found by one of Vedyra's scouts as the sole survivor of an ambushed khajiiti caravan

Vedyra's apprentice for dwemer studies

Illusion and restoration caster

Scholar with a focus on dwemer technology

No tag yet

Dagoth Nenyael

Female, she/her

Altmer

Joined House Dagoth after being abandoned as a teenager by her family in Morrowind following a tryst with a dunmer boy that resulted in a pregnancy

Mother of Cyrellas

Vedyra's apprentice for arcane studies

Arcanist

Scholar with a focus on Apocrypha and Hermaeus Mora

No tag yet

Dagoth Cyrellas

Male, he/him

Altmer and Dunmer

Born into the reborn House Dagoth

Son of Nenyael

No tag yet

Dagoth Dralyn

Male, he/him

Dunmer

Was once a of House Redoran, but was exiled for sympathizing with Vedyra's desire to rebuild House Dagoth; was subsequently welcomed into the House Dagoth Reforged with open arms

Restoration caster

Dabbles in a little bit of every trade that he can get his hands on

No tag yet

Lyrius | Wades-Through-Deep-Waters

Male, he/him

Altmer

Hero of Kvatch

Listener of the Dark Brotherhood

Was adopted by two argonian fishermen after his parents died in a shipwreck off the coast of the Black Marsh

Has worshiped Sithis since he was very young, as that his adopted parents worshiped Sithis

Dual dagger fighter

Accidental daedric prince

Lover of Lucien Lachance

#oc lyrius (tag is attached to post)

Kanbael

Male, he/him

Dunmer

Vestige

Champion of Vivec

Nightblade, dual-hand wielder nonetheless

Devout believer in the Tribunal

Part of the Thieves Guild

No tag yet

Konahrik

Nonbinary, they/them

Atmoran Nord

Other names include Hlirlef, Malaar, Silkoraav, Sosaalkro

Dragon Priest dedicated to Vulthuryol

Partner of Miraak

#oc konahrik malaar (tag is attached to post)

Rhoinuthal

Nonbinary, he/him

Dwemer

Full name is Rhoinuthal Du-Izvunrynn Ryunzcharn Khouthld Krevratch Nchul-Irhabgar Badrunz Anchamgar Chradzech; "Rho" for short

Cousin of Dumac

#oc rhoinuthal (tag is attached to post)

Kyzuzgnak

Male, he/him

Dwemer

Bodyguard of Rhoinuthal

#oc kyzuzgnak (tag is attached to post)

◈ Dungeons & Dragons

Vesper Dysgeyma

Nonbinary, they/he

Tiefling (Mammon)

Demigod of Umbra, god of the dead and dusk

College of Spirits bard

Lawful neutral

Joined the party to help them kill a despot king seeking immortality, stayed for the food

#oc vesper (tag is attached to post)

◈ Dragon Age

Talasan Mahariel

Male, he/him

Dalish elf

Hero of Ferelden (main)

Lover of Zevran

Father of Kieran and the glorious Barkspawn

Two handed weapon warrior

Brokered for peace between the Dalish and the werewolves

Sided with the mages

Sided with Prince Bhelen and Paradon Caridin

Saved Connor with the Circle of Magi's help

#oc talasan mahariel (tag is attached to post)

Andromache Surana

Female, she/her

Circle elf

Hero of Ferelden

Lover of Leliana

Spirit healer and blood mage

Brokered for peace between the Dalish and the werewolves

Sided with the mages

Sided with Prince Bhelen and Paragon Caridin

Sacrificed Isolde to save Connor

#oc andromache surana (tag is attached to post)

◈ Baldur's Gate 3

Vharis Zhendiae

Male, he/him

Drow

Dark Urge

Paladin of Vengeance

Lover of Astarion

Rejected the Urge

Twin brother of Luminara (my boyfriend's Dark Urge, who is not listed here for the reason of not being my OC)

#oc vharis zhendiae (tag is attached to post)

Red

Nonbinary, they/them

High elf

Dark Urge

Assassin rogue

Lover of Karlach

Rejected the Urge

No tag yet

Not yet added:

Dragon Age: Garrett Hawke; Inquisitor Athevera Lavellan; Inquisitor Ilrian Lavellan, Rook

Mass Effect: Ariane Shepard

Baldur's Gate 3: Azran, Serene

#salem chatter#long post ₁⁞³—©#oc vedyra#oc vedathyr#oc lyrius#oc vesper#oc talasan mahariel#oc andromache surana#oc vharis zhendiae#oc moon and star#oc konahrik malaar#oc voralen#oc rhoinuthal#oc kyzuzgnak

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from Grist:

A growing number of companies are bringing automation to agriculture. It could ease the sector’s deepening labor shortage, help farmers manage costs, and protect workers from extreme heat. Automation could also improve yields by bringing greater accuracy to planting, harvesting, and farm management, potentially mitigating some of the challenges of growing food in an ever-warmer world.

But many small farmers and producers across the country aren’t convinced. Barriers to adoption go beyond steep price tags to questions about whether the tools can do the jobs nearly as well as the workers they’d replace. Some of those same workers wonder what this trend might mean for them, and whether machines will lead to exploitation

On some farms, driverless tractors churn through acres of corn, soybeans, lettuce, and more. Such equipment is expensive, and requires mastering new tools, but row crops are fairly easy to automate. Harvesting small, non-uniform and easily damaged fruits like blackberries, or big citruses that take a bit of strength and dexterity to pull off a tree, would be much harder.

That doesn’t deter scientists like Xin Zhang, a biological and agricultural engineer at Mississippi State University. Working with a team at Georgia Institute of Technology, she wants to apply some of the automation techniques surgeons use, and the object-recognition power of advanced cameras and computers, to create robotic berry-picking arms that can pluck the fruits without creating a sticky, purple mess.

The scientists have collaborated with farmers for field trials, but Zhang isn’t sure when the machine might be ready for consumers. Although robotic harvesting is not widespread, a smattering of products have hit the market, and can be seen working from Washington’s orchards to Florida’s produce farms.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

XYZVerse: Pioneering the First Ever Sports Meme Coin

In the rapidly evolving world of cryptocurrency, innovation is the name of the game. Enter XYZVerse, a groundbreaking platform that has launched the first-ever sports-themed meme coin, seamlessly blending the energy of sports fandom with the dynamic world of blockchain technology. But what makes XYZVerse and its unique offering stand out in the crowded crypto landscape?

The Intersection of Sports and Crypto

Sports have always been a unifying force, rallying millions of fans worldwide around their favorite teams, players, and moments. The cryptocurrency space, on the other hand, thrives on community-driven momentum and innovation. XYZVerse leverages these two powerful elements to create a unique digital asset that appeals to both crypto enthusiasts and sports fans alike.

The XYZVerse sports meme coin is not just a token; it’s a symbol of community and shared enthusiasm. It captures the humor, passion, and camaraderie that define sports culture, embedding it into a decentralized financial ecosystem.

Features of the XYZVerse Sports Meme Coin

Community-Centric Approach The XYZVerse coin is designed to celebrate and amplify fan participation. Community members can create, share, and monetize sports-related memes, fostering creativity and engagement.

Utility and Rewards Unlike traditional meme coins, XYZVerse offers tangible benefits. Users can earn rewards by participating in events, engaging in fantasy sports leagues, or contributing to the platform’s ecosystem.

NFT Integration To add another layer of value, XYZVerse integrates NFTs (non-fungible tokens). Fans can mint unique sports moments as NFTs, trade them, or showcase them as digital collectibles within the platform.

Decentralized Governance XYZVerse empowers its community through decentralized governance, allowing token holders to vote on platform updates, partnerships, and key decisions.

The Roadmap Ahead

XYZVerse has an ambitious roadmap that promises to revolutionize the way fans interact with sports and crypto. Upcoming features include partnerships with major sports leagues, exclusive athlete collaborations, and the launch of a dedicated sports-themed metaverse.

Key Milestones:

Q4 2024, Q1 2025: Presale Launch

Kick off the presale campaign to give early investors the edge.

Q1 - Q2 2025: Token Generation & Exchange Listings

Host the Token Generation Event (TGE) and distribute $XYZ tokens to investors and X-points farmers.

Secure $XYZ listings on major cryptocurrency exchanges.

Roll out staking and liquidity mining programs for holders.

Q3 2025: Gamification & Play-to-Earn Integration

Launch the first wave of gamified products for users.

Forge partnerships with leading sports games and platforms for seamless integration.

Introduce play-to-earn features to reward active participation.

Begin developing a platform to drive crypto mass adoption.

Q4 2025: Sports Celebrity Collaborations

Partner with high-profile sports personalities to amplify reach.

Launch the XYZVerse referral program to grow the community.

Integrate $XYZ tokens for use in gaming and influencer sponsorships.

Collaborate with sports media companies to deliver exclusive content for XYZVerse users.

Why XYZVerse Matters

In a world where digital and physical experiences are increasingly intertwined, XYZVerse represents a paradigm shift. It taps into the emotional and cultural significance of sports while leveraging the transformative potential of blockchain technology. The result is a vibrant ecosystem where fans are not just spectators but active participants and stakeholders.

As the first sports meme coin, XYZVerse is more than a financial asset; it’s a movement. It’s an invitation for sports fans and crypto enthusiasts to come together, innovate, and celebrate their shared passions in a whole new way.

#XYZVerse2TheMoon #XYZVerse #XYZ

Our official links:

🌐 Website: xyzverse.io

🐦 Twitter\X: https://x.com/xyz_verse

📣 Channel: @xyzverse

📃 Docs: https://doc.xyzverse.io/

🔥Sales: @xyzverse_sales

💎Ambassador Airdrop Program: @xyzverse_ambassador_bot

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How MAJOR and STON.fi Are Redefining Blockchain Gaming and DeFi

When we talk about innovation in finance and technology, blockchain often sits at the center of the conversation. It’s like the dawn of the internet, where everyone knows it’s going to change everything, but only a few truly understand how. That’s exactly what blockchain gaming and decentralized finance (DeFi) represent today—a new frontier where creativity meets financial empowerment.

As someone deeply invested in this space, I’ve always believed in making complex concepts accessible. And when I discovered MAJOR on STON.fi, I realized it’s more than just a game or a decentralized exchange (DEX); it’s a blueprint for the future. Let me take you on a journey to understand why this is so revolutionary, with relatable analogies and clear explanations that break it all down.

A Paradigm Shift in Gaming and Finance

Picture this: in traditional gaming, you’re like a tenant in a house. You pay rent (buy the game), enjoy the amenities (play the game), but at the end of the day, you don’t own anything. Blockchain gaming flips this model on its head. It makes you a homeowner—every token you earn, every item you acquire has real-world value that you can trade or invest.

This is the core idea behind MAJOR, a ranking game built on the TON Blockchain and integrated seamlessly into Telegram. It’s not just about playing for fun; it’s about earning rewards that hold tangible value. With a user base that has grown to 32 million, MAJOR proves that gaming can be more than entertainment—it can be an investment in your financial future.

What Makes MAJOR Unique

In the world of MAJOR, every move you make counts. Players join squads, strategize, and climb global rankings, earning rewards along the way. It’s like running a small business: your decisions, teamwork, and strategy directly impact your rewards.

What’s even more impressive is how MAJOR is integrated into Telegram. Think about it—Telegram is already part of our daily lives, whether for messaging friends or joining communities. By bringing blockchain gaming into this familiar space, MAJOR eliminates the steep learning curve that often discourages newcomers. It’s like setting up a marketplace in your neighborhood rather than a remote town—convenient, accessible, and easy to adopt.

The Role of the MAJOR Token

Let’s talk about the MAJOR token, the backbone of this ecosystem. Imagine it as the currency of a bustling city where you can shop, trade, and invest. Every action in the MAJOR game—whether competing in challenges or climbing the rankings—earns you this token. And here’s the exciting part: it doesn’t just stay within the game.

The MAJOR token is available for trading and liquidity provision on STON.fi, a decentralized exchange. This means you can convert your in-game rewards into other assets or use them to generate passive income. It’s like earning frequent flyer miles that you can either redeem for a vacation or sell for cash. The flexibility is entirely yours.

The Power of Liquidity Pools and Farming

Let me explain farming in simple terms. Imagine you own a piece of land. Instead of leaving it idle, you decide to rent it out to farmers. They grow crops, and you get a share of the profits. In DeFi, your “land” is your tokens, and the “farmers” are liquidity pools.

On STON.fi, you can pair MAJOR tokens with TON tokens to create liquidity pools. By doing this, you’re essentially contributing to the smooth operation of the exchange, making it easier for others to trade tokens. And the reward? You earn STON tokens as passive income.

Right now, the MAJOR/TON farming pool offers 10,000 STON tokens (worth ~$48,500) as rewards. The farming period runs until December 28, with no lock-up period for your tokens. This flexibility is a game-changer, allowing you to dip in and out without any long-term commitments.

Why This Matters for Everyone

The integration of MAJOR and STON.fi isn’t just about gaming or trading—it’s about creating opportunities. Whether you’re a gamer, a crypto enthusiast, or someone curious about blockchain, this ecosystem has something for you.

For gamers, it’s a chance to turn your skills into financial gains. For crypto investors, it’s an opportunity to diversify your portfolio with assets that have both utility and growth potential. And for beginners, it’s a gateway into the world of blockchain without the intimidation of complex setups or steep learning curves.

Real-Life Analogies for Better Understanding

If you’re new to this, think of MAJOR and STON.fi as a hybrid of a video game and a stock market. In the game, your skill and strategy determine how much you earn. On the DEX, your decisions about trading and farming determine how much you grow your assets. It’s like playing Monopoly but with real money—every property you acquire and trade has tangible value.

Another analogy: imagine a community garden. Everyone contributes seeds and tools, and at the end of the season, the harvest is shared. In MAJOR’s ecosystem, your tokens are the seeds, the liquidity pool is the garden, and the STON rewards are the fruits of your collective effort.

A Personal Perspective

When I first explored platforms like MAJOR and STON.fi, I was skeptical. It sounded too good to be true—play a game, trade some tokens, and earn real money? But as I dived deeper, I realized that these platforms are built on solid principles of blockchain technology: transparency, decentralization, and user empowerment.

I’ve seen firsthand how MAJOR transforms gaming from a time-consuming hobby into a rewarding experience. And STON.fi’s decentralized model ensures that every transaction is fair and transparent, eliminating the hidden fees and middlemen that plague traditional finance.

The Future of Blockchain Gaming and DeFi

The collaboration between MAJOR and STON.fi is more than a partnership—it’s a glimpse into the future. A future where gaming isn’t just about entertainment but also about financial inclusion. A future where DeFi isn’t just for crypto experts but for anyone willing to learn and participate.

If you’ve been on the fence about exploring blockchain, now is the time to jump in. Start small, experiment with MAJOR on Telegram, trade tokens on STON.fi, and see how these platforms can empower you. Remember, the blockchain revolution isn’t about replacing the old systems; it’s about improving them, making them more inclusive and rewarding for everyone.

In conclusion, MAJOR and STON.fi are setting a new standard in blockchain gaming and DeFi. They’re accessible, innovative, and packed with opportunities. Whether you’re here for the game, the finance, or the technology, there’s a place for you in this ecosystem. And trust me, once you experience it, you’ll never look at gaming or finance the same way again.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is this the Largest Sweet Potato in Kenya? The Inspiring Story of Manoah Kilach's 11-Kilogram Sweet Potato

In the verdant Ngata area of Nakuru County, Manoah Kilach has transformed agricultural practice through meticulous organic farming and technological innovation. A retired educator turned agricultural entrepreneur, Kilach stands as a testament to the potential of modern, sustainable farming techniques. On a sun-drenched Friday morning, Kilach proudly displayed an extraordinary achievement: an…

#agricultural innovation in Kenya#crop diversity in Kenya#crop production in Nakuru#farming education hubs#farmyard manure use#holistic farming approaches#Kabode sweet potato#Kalro farming techniques#Kenspot One#Kenyan agricultural entrepreneurs#large sweet potato yields#local farmer networks#Manoah Kilach#modern farming methods.#Nakuru farming innovations#Ngata sweet potato farming#Organic farming practices#record-breaking sweet potatoes#soil health management#soil nutrient testing#sustainable agriculture#sustainable farming practices#Sweet Potato farming in kenya#sweet potato flour production#sweet potato market in Nairobi#sweet potato nutritional benefits#sweet potato varieties in kenya#technological adoption in farming#value addition in agriculture#value-added agriculture

0 notes

Text

How Payout Solutions Drive Financial Inclusion Across Developing Economies ?

Financial inclusion is a critical driver of economic development, particularly in developing economies where access to traditional banking services remains a significant challenge. Payout solutions are emerging as transformative tools to bridge this gap, offering innovative ways to empower underserved populations and integrate them into the financial ecosystem. This article explores how payout solutions contribute to financial inclusion, their benefits, and the role of digital innovation in achieving these goals.

Understanding Payout Solutions

Payout solutions refer to systems and technologies designed to facilitate seamless, secure, and efficient payments to individuals or businesses. These solutions include a wide range of services, such as:

Payroll disbursements

Social benefit payments

Gig economy payouts

Cross-border remittances

By leveraging payout solutions, organizations can ensure timely and accurate disbursement of funds, even in areas with limited access to traditional banking infrastructure.

The Importance of Financial Inclusion in Developing Economies

Financial inclusion means providing individuals and businesses access to affordable and useful financial products and services, including payments, savings, credit, and insurance. It is vital for economic growth, as it:

Empowers Individuals: Access to financial services enables individuals to save, invest, and plan for the future.

Boosts Economic Participation: Financial inclusion integrates more people into the economy, fostering entrepreneurship and innovation.

Reduces Inequality: It narrows the gap between the privileged and underserved populations by offering equal opportunities for financial growth.

However, traditional banking systems often fall short in developing economies due to factors like limited infrastructure, high operating costs, and lack of financial literacy. Here, payout solutions offer a practical alternative.

How Payout Solutions Drive Financial Inclusion

Reaching Remote Areas Payout solutions utilize digital tools to overcome geographic barriers. Mobile-based applications and point-of-sale systems enable individuals in remote regions to access funds without needing a physical bank branch. For instance, farmers can receive subsidy payments directly into their mobile wallets, eliminating the need to travel long distances.

Enabling Faster Transactions Instant payout solutions are critical for individuals relying on timely income, such as gig workers or daily wage earners. These solutions use real-time digital solutions to ensure payments are processed instantly, helping users meet their immediate needs.

Reducing Costs Traditional banking often involves high transaction fees, making it inaccessible for low-income populations. Payout solutions streamline the process and reduce costs by leveraging digital infrastructure, making financial services more affordable.

Enhancing Security By employing secure technologies such as encryption and biometric authentication, payout solutions minimize fraud and ensure the safe transfer of funds. This builds trust among users, encouraging wider adoption.

Promoting Financial Literacy Many payout solutions integrate user-friendly platforms and educational tools to help individuals understand financial services better. This fosters confidence and encourages users to explore other financial products, such as savings accounts and microloans.

Digital Solutions Powering Payout Innovations

The role of digital solutions in advancing payout systems cannot be overstated. Technologies like mobile banking, blockchain, and artificial intelligence have revolutionized the way funds are distributed and accessed. For instance:

Mobile Wallets: These are at the forefront of digital payment solutions, enabling individuals without bank accounts to receive and spend money using their mobile devices.

Blockchain Technology: Secure and transparent, blockchain facilitates cross-border payouts with minimal fees, benefiting migrant workers sending money home.

AI and Data Analytics: These tools optimize payout processes by identifying patterns and reducing inefficiencies, ensuring smooth transactions.

Companies like Xettle Technologies are pioneering these digital innovations by providing custom payout solutions tailored to the unique needs of developing economies. Their platforms combine advanced security features with user-friendly interfaces, enabling a seamless experience for both individuals and businesses.

Case Studies: Payout Solutions in Action

Social Benefit Disbursements in India The Indian government’s Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme leverages payout solutions to deposit welfare payments directly into beneficiaries’ accounts. This has reduced leakages and ensured funds reach the intended recipients.

Gig Economy Payments in Africa In Africa, mobile payment systems like M-Pesa facilitate payouts for gig workers, enabling them to access their earnings instantly. This has been instrumental in empowering freelancers and small business owners.

Cross-Border Remittances in Southeast Asia Migrant workers in Southeast Asia rely on digital payout solutions to send money home. These solutions are faster and cheaper than traditional remittance methods, allowing families to access funds quickly.

Challenges and Opportunities

While payout solutions hold immense promise, certain challenges persist, such as:

Limited Digital Infrastructure: Many regions lack the internet connectivity needed to support digital solutions.

Regulatory Barriers: Complex regulations can hinder the deployment of payout systems.

Low Financial Literacy: Many individuals remain unaware of how to use payout solutions effectively.

Addressing these challenges requires collaboration between governments, financial institutions, and technology providers. By investing in infrastructure, streamlining regulations, and promoting financial education, stakeholders can unlock the full potential of payout solutions.

Conclusion

Payout solutions are a cornerstone of financial inclusion in developing economies, offering accessible, affordable, and secure ways to distribute funds. By leveraging digital solutions and collaborating with innovators like Xettle Technologies, organizations can create impactful systems that empower individuals and drive economic growth. As technology continues to advance, the role of payout solutions in fostering an inclusive financial ecosystem will only grow stronger.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on veganism?

It's fine. Food is food.

At the grocery store, meat is 3x more expensive than tofu.

Jigsaw Farms in Australia is one of the most sustainable animal agriculture farms in the world. They recently discovered that even a sustainable operation hits carbon saturation after 10 years of animal agriculture. And I don't mean sustainable as an empty industry buzzword. I mean world-class sustainable agriculture recognized and monitored by ecologists. Just so you understand what that might look like, here's a description of Jigsaw:

The 3,378-hectare farm spans six titles, bought between 1996 and 2003. Hardwood timber plantations cover 295 hectares, 24 hectares is remnant forest and a further 268 hectares are set aside for biodiversity. It hosts a fine wool merino operation with about 20,000 ewes, and 550 head of cattle.

If you do absolutely everything right, you can sequester the carbon of animal agriculture for a decade. After that, no matter what you do, you will not be able to sequester more carbon than you produce. The land will be saturated.

I believe this discovery gives a road map for an ideal agricultural transition.

Let's say tomorrow the entire global animal agriculture industry, everyone from factory farms to family farms, decides to become Jigsaw. First, it would take about 5 years to transition the land and infrastructure. Then there would be about 10 years of sustainable animal agriculture. And I'll add an extra five years there to make it flexible. So that's 20 years. A 20 year transition. After that, we'll eat our last farmed animal products. And then there'd be tons of carbon-rich land that could be used for plant agriculture.

Unfortunately, humans haven't evolved a sustainable hivemind. We have massive variation in social behavior. So, with a transition like this, there will be early adopters, bandwagoners, and stragglers.

Now let's talk about fishing.

The fishing industry can theoretically be eternally sustainable. Large scale wild catch can go on forever. Farming shellfish can go on forever. Farming fish like salmon and cod is a massive ecological disaster but other forms of aquaculture are fine. We already know exactly how to run this industry in a 100% sustainable way. There's no mystery to it and all the technology is available. Unfortunately, in the fishing industry, we once again run into the problem of variation in human social behavior. There are both angels and devils who work on the ocean. And the devils are economically rewarded while the angels toil away and go bankrupt.

Sustainable food production methods are not profitable in our current economic system. It's impossible to make them profitable. Right now, there is only one way to make a profit in food production. You need to destroy the land and ocean and doom future generations to starvation. Basically, by stealing value from the future, you can make a profit and be wealthy in the present. Farmers in France have been viciously protesting for their right to steal from the future. Their government tried to regulate them into respecting the people of 2070s France. But they don't want to do it. Human variation in social behavior is very difficult to deal with.

And finally, there's hunting. Ecologically, we need hunters who are humans as well as the reintroduction and promotion of non-human predators. However, poachers and wildlife traffickers can destroy an ecosystem faster than any other industry. They can delete an entire species in less than a year. Hunting deer and rabbits is not profitable. Wildlife trafficking is extremely profitable. So once again, angels and devils and money.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet three startups, from Morocco, Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of Congo, that are harnessing technology to provide simple, viable solutions to energy and food security in Africa.

1. Meier Energy, Morocco’s standard-bearer for energy efficiency

Founded in 2020 by Fouad El Kohen, Meier Energy offers businesses tailor-made solutions to kick-start their energy transition. In just four years, it has established itself as one of the leading start-ups in Morocco and is already exporting outside the country. “It’s a young company dedicated to the development and marketing of energy efficiency, electricity and smart grid equipment,” says founder El Kohen. “Our ambition is to support the ecological transition in both Morocco and Africa.”

2. BioAni, the Ivorian start-up that wants to bid goodbye to chemical fertilisers

BioAni sells organic fertilisers produced using black soldier fly larvae, products that are much cheaper than chemical fertilisers. All that remains is for them to convince farmers to change their habits.

It all began in a garage in Abidjan’s Cocody district with food waste and a few larvae. The insects transform this bio-waste into a particularly effective organic fertiliser. Founder Arthur de Dinechin wanted to get involved in an environmental project in Africa, his adopted continent. After trying his hand at plastic recycling, his thoughts turned to agriculture.

“Here in Côte d’Ivoire, millions of people make their living from farming. There are very few resources in place to help them make a profit from this activity,” he says.

3. GreenBox, the storage solution changing Congolese farmers’ lives

GreenBox enables farmers in the Democratic Republic of Congo to store their fruit and vegetables for three weeks instead of two days, using new technology that gives farmers access to remote control of solar-powered cold rooms. These refrigerators also make it possible to establish the state of ripeness of a stored product and ensure its traceability. Its five installations, spread across as many villages, enable customers’ harvests to be monitored in real-time.

Founder Divin Kouebatouka says: “Storage is centralised for the whole village. The cold room is managed by a cooperative. We make racks available to farmers so that they can store their produce. We can’t rent to everyone, so it’s first come, first served.”

For CFA200 a day (around $0.10), farmers are provided with a locker that can hold 30kg of food. “Small farmers, our core target, can’t buy a cold room. That’s why we’ve introduced daily, weekly and monthly rates. Everyone can choose the subscription that suits them best, which is nothing compared to the value of the products they entrust to us,” says Kouebatouka. In addition to his team of 12 employees, a group of five women is responsible for the daily maintenance and management of the cold rooms.

#solarpunk#solarpunk business#solarpunk business models#solar punk#startup#reculture#africa#jua kali solarpunk#farmers#solar power

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vertical Farming Market Recent Trends and Growth Analysis Report 2024 – 2030

The global vertical farming market size is expected to reach USD USD 24.95 billion by 2030, according to a new report by Grand View Research, Inc. It is expected to expand at a CAGR of 20.1% from 2023 to 2030. Increased use of Internet of Things (IoT) sensors for producing crops is likely to spur market demand over the forecast period. Information obtained from the sensors is stored on the cloud and analyzed to perform the required actions. The growing automation in agriculture and increasing use of big data and predictive analytics for maximizing yields are also likely to drive the market.

Vertical farming is effective in ensuring stability in crop production and maintaining reliability even in adverse climatic conditions. It provides multiple benefits over the traditional farming technique, such as less use of water, the lesser need for agrochemicals, and low dependence on agricultural labor. Vertical farming makes use of metal reflectors and artificial lighting to maximize natural sunlight.

Genetically modified organisms and the environmental and health effects of pesticides and other non-natural substances that are used for increasing agricultural production have encouraged consumers to adopt organic foods. According to the Organic Trade Association, the U.S. organic industry sales increased by around 5% in 2019 owing to the increased investment in infrastructure and education. As per the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990, the handlers and growers of organic products need to comply with the regulations.

Gather more insights about the market drivers, restrains and growth of the Vertical Farming Market

Detailed Segmentation:

Market Concentration & Characteristics