#exponent ii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Spiritual Nature of All Things

Kaylee McElroy is a physicist and wrote this intriguing article for Exponent II. There are two passages from the article that really resonated with me.

The first passage gives an explanation for how those who are on the outer edges of an entity don't have the same experience as those in the center. The relationship they have is different from those in the center. Those in the center have their bonding needs met while those on the edges do not. For those on the margins of the LDS Church, they may try to make a more comfortable relationship by going to a different congregation than they're assigned, by changing how they think about the teachings which are difficult for them, by asking to be released from a calling, and by separating themselves from the church. The same molecule/individual will act differently in different structures because their relationships within that structure is different.

The second quote gives an example that sex/gender is not a clear binary in nature that is separate and distinct. If this is created by God, then perhaps God's idea of sex/gender isn't so narrow as we teach in church and politics.

————————————————————

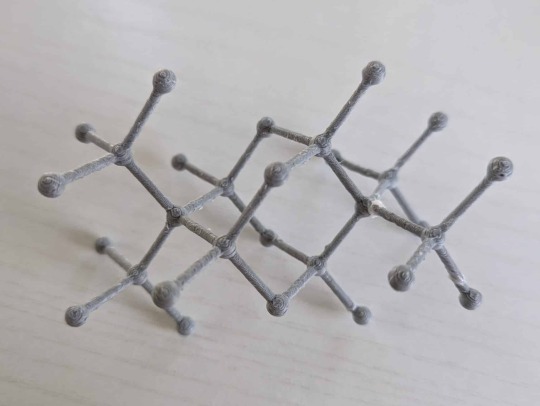

One familiar form of carbon is diamond. If you have a diamond ring, the diamond is made of carbon atoms. The carbon atoms in the middle are all bonded to four other carbon atoms. The crystal structure looks like this:

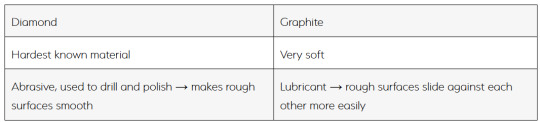

These bonds are very strong and they are equally strong in all directions. This makes diamond the hardest natural material.

Another familiar form of carbon is graphite. The “lead” in a pencil isn’t made out of the element lead. The lead of a pencil is graphite, which is another form of carbon. These carbon atoms are arranged in sheets of hexagons. The bonds between the carbon atoms in an individual sheet are very strong. The bonds between the sheets are weak, so the sheets slip against each other which allows you to make marks on a piece of paper.

Graphite and diamond are both made of the exact same element, but the atoms are arranged in a different structure. The structural difference gives these two materials very different properties. The exact same element can have opposite properties when it is in a different structure.

I’m going to make a kind of silly analogy: You are a carbon atom. You will behave differently when you are in different social structures. You will behave differently when you are in different spiritual structures. I’m going to say that the church is like diamond. It can look very pretty. It can be hard to alter. The atoms on the surface of a diamond are in energetically unfavorable positions. Atoms in the center of the diamond are bonded to four other carbon atoms. Atoms on the surface are not. They may only be bonded to two other carbons. They want to have more bonds so they can be more comfortable. The surface atoms may deform the lattice structure to stay on. They may skitter along the surface hoping to find a better spot with a ledge. They may pop off the surface altogether and may or may not ever get back on. Carbon atoms on the surface of a diamond will readily bond to other atoms like hydrogen or oxygen. These surface bonds affect the properties of the crystal. Depending on what the carbon bonds to, the surface may be hydrophilic or hydrophobic, insulating or conducting. The surface of a diamond can be engineered to meet specific needs.

It’s energetically unfavorable to be at the boundary of the church too. Some of us are engaged with the church, but feel discomfort. Some of us have found church engagement untenable for whatever mix of reasons. I want to suggest that you can engineer your church relationship to meet your life’s needs. People at the boundaries of the church have extra influence with how the church interacts with the outside world. You can decide what that looks like for you.

—————————

At some point though, this gender binary wasn’t big enough for me. I took my older daughters to do baptisms at the temple. I stayed outside with my youngest. It was a beautiful summer day and she didn’t want to go in the stake center to play with the other kids, so we spread a blanket under a tree and played games. She wondered about a maple spinner that whirled down next to us so we started talking about plant reproduction. There were daylilies all around the temple, so we dissected one. We stained our fingers with the pollen from the anthers of the stamen. We felt the sticky stigma and looked for the ovary in the pistil. She was amazed that the flowers could be boys and girls at the same time! There is an artificial binary inside the temple. One of my daughters had told me that it seemed wrong to her that women have to be baptized for women and men have to be baptized for men. The natural world, with all its varieties of God’s creations, shows us so many other ways of being.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific - Part 23

[ First | Prev | Table of Contents | Next ]

II - Dialectics

In the meantime, along with and after the French philosophy of the 18th century, had arisen the new German philosophy, culminating in Hegel.

Its greatest merit was the taking up again of dialectics as the highest form of reasoning. The old Greek philosophers were all born natural dialecticians, and Aristotle, the most encyclopaedic of them, had already analyzed the most essential forms of dialectic thought. The newer philosophy, on the other hand, although in it also dialectics had brilliant exponents (e.g. Descartes and Spinoza), had, especially through English influence, become more and more rigidly fixed in the so-called metaphysical mode of reasoning, by which also the French of the 18th century were almost wholly dominated, at all events in their special philosophical work. Outside philosophy in the restricted sense, the French nevertheless produced masterpieces of dialectic. We need only call to mind Diderot's Le Neveu de Rameau, and Rousseau's Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes. We give here, in brief, the essential character of these two modes of thought.

When we consider and reflect upon Nature at large, or the history of mankind, or our own intellectual activity, at first we see the picture of an endless entanglement of relations and reactions, permutations and combinations, in which nothing remains what, where and as it was, but everything moves, changes, comes into being and passes away. We see, therefore, at first the picture as a whole, with its individual parts still more or less kept in the background; we observe the movements, transitions, connections, rather than the things that move, combine, and are connected. This primitive, naive but intrinsically correct conception of the world is that of ancient Greek philosophy, and was first clearly formulated by Heraclitus: everything is and is not, for everything is fluid, is constantly changing, constantly coming into being and passing away. [A]

But this conception, correctly as it expresses the general character of the picture of appearances as a whole, does not suffice to explain the details of which this picture is made up, and so long as we do not understand these, we have not a clear idea of the whole picture. In order to understand these details, we must detach them from their natural, special causes, effects, etc. This is, primarily, the task of natural science and historical research: branches of science which the Greek of classical times, on very good grounds, relegated to a subordinate position, because they had first of all to collect materials for these sciences to work upon. A certain amount of natural and historical material must be collected before there can be any critical analysis, comparison, and arrangement in classes, orders, and species. The foundations of the exact natural sciences were, therefore, first worked out by the Greeks of the Alexandrian period [B], and later on, in the Middle Ages, by the Arabs. Real natural science dates from the second half of the 15th century, and thence onward it had advanced with constantly increasing rapidity. The analysis of Nature into its individual parts, the grouping of the different natural processes and objects in definite classes, the study of the internal anatomy of organized bodies in their manifold forms — these were the fundamental conditions of the gigantic strides in our knowledge of Nature that have been made during the last 400 years. But this method of work has also left us as legacy the habit of observing natural objects and processes in isolation, apart from their connection with the vast whole; of observing them in repose, not in motion; as constraints, not as essentially variables; in their death, not in their life. And when this way of looking at things was transferred by Bacon and Locke from natural science to philosophy, it begot the narrow, metaphysical mode of thought peculiar to the last century.

[A] Unknown to the Western world until the 20th-century, the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu was a predecessor of or possibly contemporary to Heraclitus. Lao Tzu wrote the renowned Tao Te Ching in which he also espouses the fundamental principles of dialectics.

[B] The Alexandrian period of the development of science comprises the period extending from the 3rd century B.C. to the 17th century A.D. It derives its name from the town of Alexandria in Egypt, which was one of the most important centres of international economic intercourses at that time. In the Alexandrian period, mathematics (Euclid and Archimedes), geography, astronomy, anatomy, physiology, etc., attained considerable development.

China also been began development in natural sciences in the third century B.C.E.

[ First | Prev | Table of Contents | Next ]

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

On January 7th 1661, six ‘grave makers’ were paid £18 Scots for ‘raising’ the "mangled torso" of James Graham, Marquess of Montrose.

The Great Montrose, as he was known by his supporters, was renowned for his tactical genius on the battlefield during the civil wars that cost King Charles I both crown and head. Although Montrose would die as a royalist he first entered the lists in the 1630s’ as part of the Covenanters who were resisting Charles I attempts to impose a religious governance on Scotland, which according to legend was kicked of by Edinburgh’s Jenny Geddes in St Giles Cathedral.

Montrose as Covenanter was a moderate and afetr the Bishops War he became a leading exponent of the pro-reconciliation faction, bitterly opposed by the chief of the Campbell clan, who Graham distrusted, and rightly so.

The two became the opposing poles for the ensuing civil war in Scotland, at once a local clan war that would end up involving Ireland and England. Although Montrose, now King Charles’s lieutenant-general in Scotland, could hold his own on the battle fields he cherry picked skilfully using the hills and Glens to his advantage, as other great generals, Wallace and Bruce had centuries before.

Grahams luck came to an end when he was betrayed, taken to Edinburgh and exxecuted for treason in May 1650, while his limbs were distributed for exhibition in Glasgow, Stirling, Perth and Aberdeen. A family member arranged for Montrose’s heart to be removed surreptitiously from his torso after its burial and to be sent – after embalming – to his son in the Netherlands

After the restoration of Charles II in 1660 prompted the king to turn the tables on the Covenanters. In an upsurge of Royalist popular sentiment, Montrose was rehabilitated in a public ceremony in which his mangled corpse was disinterred and reunited with his head, heart and limbs, all of which were recalled from their various locations. In 1661, he was given a splendid funeral and reburied in St. Giles’ Cathedral, where his tomb can be viewed today, and more often than not, you will see a floral tribute to the man, such is the regard he is still held in.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fragmenta Vitae (II)

art creds: drosaxx on twt

Albedo x Lumine

❝ After albedo inevitably loses control, he pays the highest price by killing the person dearest to him. He will try to make amends by making use of his darkest alchemical knowledge. ❞

Cw: death, murder, mourning, obsession, blood, dead body, angst

n/a: It was REALLY hard to envision a possible Neo-Khaenri’ah--- I had to ask for help from CHATgpt chat because worldbuilding and I don’t get along very well-- However, it's still fun to imagine an alternative version of future Teyvat :D. Of course, I want to clarify once again that this story takes place in an AU set after the end of the game canon story. The war ended with Lumine’s death, who had to face Albedo as her final challenge, concluding with her death (poor Aether, he's now sad and alone-) I hope this point is clear enough (feedbacks are much appreciated), anyway, many more characters and lore have to appear yet. BTW!!! Rhinedottir is such an interesting character, I can't wait for her to officially appear in game. I need more Khaenri’ah and its people's lore. I also like to imagine Albedo and Lumine like this in my story: (also see below)

word count: 4473

Teyvat was progressively evolving. After the last great war, nations were getting back on their feet, mainly through mankind aid. Years passed quickly, evolution just as rapid through the succession of generations. The conflict against the Heavenly Principles and the Abyss Order ended in glory, imprinted as one of the most tragic and grandiose events in history, though, of course within a cost; many creatures fell, whole systems were destroyed. Celestia, the ever present force that loomed over Teyvat for centuries, was no longer a forced control in the skies. The shackles imposed by the gods had been broken, and in their absence, humanity seized control of its own destiny. Finally, with the divine rule gone, the world no longer belonged to the heaven's thrones, but to those who roamed the earth.

Khaenri’ah, once the cursed nation led by no deity, raised again, reborn from its own ashes it shone more beautifully and majestically than ever. Now, Neo-Khaenri’ah flourished in this new era, becoming a beacon of innovation, a testament to what a civilization could achieve when unburdened by the interference of higher powers.

Towering spires of brass and steel, adorned with intricate engravings of their lost history. All around were scattered floating platforms powered by etheric energy, defying gravity through advanced machinery, gears and cogs embedded into buildings, constantly turning like the beating heart of the city. Stained glass windows gracefully depicted past legends, illuminated by phosphorescent gas lamps. Walking through its streets seemed to cross another reality entirely. The technological industry was the most advanced in Teyvat, just as it used to be; a blend of alchemical engineering and steam powered innovation, automaton workers with intricate filigree plating, operating complex machinery. Airships and mechanical chariots could be spotted gliding through the sky, their engines humming with a mix of steam and arcane energy. Institutions were instituted “Aetheric Conduits”: massive pipelines running through the city, distributing power to homes, factories, and vehicles, along the “Luminary Core”, a vast central generator, pulsing like a mechanical heart, the key to Neo-Khaenri’ah’s survival.

Khaenri’ah became a meritocratic society, led by the monarchy and its council, established by exponents who rose trough their intellect. Guilds of artificers, inventors, and scholars, each competing to push the boundaries of technology. There was a certain reverence for lost knowledge, with grand libraries housing texts preserved from even before the cataclysm. Progress swept across the land, driven by the minds of those who had long been denied the chance to create freely.

Among them was the Kreideprinz Albedo.

With Celestia’s threats no longer hanging over his head, the former alchemist could finally push the limits of his knowledge without restraint, although aware that every mystical force must have boundaries. The Art of Khemia, once a forbidden and dangerous craft, was now his to explore without fear, along with several other alchemists and scientists who enjoyed playing with reality’s restrictions. Albedo could have become a feared and respectable figure in his new life, after all, he had full faculties on that matter, but the latter rather opted to open a humble alchemical emporium in the new nation of Khaenri'ah. Yet, despite the infinite possibilities before him, his focus remained singular: Lumine.

The mysterious outlander returned to him, yet not entirely. Lumine’s soul was there, but incomplete. Her body was perfect, yet empty of the memories that made her who she once was. Sometimes, looking at her, Albedo saw the woman he madly loved years before, other times, he saw a stranger who was still learning about the world all around them. And still, he fully dedicated himself to her. Under his wing and guidance, Lumine had to learn everything from the beginning: language, culture, even the simplest of concepts, everything was foreign to her. The young girl observed the world with the wide eyed wonder of a child, yet there was something different about her. She was not like an ordinary newborn soul, she learned quickly, her mind grasping ideas at a speed that defied nature, absorbing knowledge as if it had always been within her, merely waiting to be unlocked. Still, the process was slow, but Albedo was patient. He became Lumine’s guide, her mentor, her anchor in a world that should have somehow been familiar but was now entirely unknown. He spoke to her with gentle tones, enunciating words with care, repeating phrases until they took root in her mind. Then, one day, she spoke her first word. It was clumsy, a fusion of syllables that didn’t quite fit together; a muddled attempt at “Master” and “Albedo.” The pronunciation was incorrect, but the intent was clear. Albedo froze, for a moment, he simply stared, as if doubting his own hearing. Then, slowly, his expression softened, his lips parting in a quiet exhale of astonishment. A small, genuine smile ghosted across his face.

“You’re learning.” The blonde man murmured, his voice barely above a breath.

Encouraged from his tender expression, Lumine repeated his name again, slowly, carefully, guiding her tongue toward the correct sounds. Her attempts were hesitant at first, imperfect, but persistent. Every time she spoke, Albedo listened intently, his eyes filled with quiet admiration. It became a game between them, a ritual of sorts where Lumine would try, and Albedo would correct, and no matter how garbled the result, he never expressed frustration. There was no impatience in that kind man, only quiet encouragement and the deep, unspoken warmth of someone who was simply grateful to hear her voice at all. With time, Lumine’s vocabulary expanded. Simple words became full sentences, fragmented thoughts became coherent ideas, and through it all, Albedo remained at her side, watching as his most successful creation rebuilt herself from the pieces of a past she could not recall.

Yet sometimes, in the quiet hours of the night, flickers of that lost life would surface. Memories would come in brief, fleeting bursts, too fast to grasp, too distant to understand. They struck without warning, leaving Lumine disoriented, shaken. And when they did, Albedo was always there, steady, unmovable. He would not let the love of his life fall again, he would be whatever she needed him to be; a teacher, a guardian, a friend. And no matter how long it took, he would not stop until she would've reclaimed what was hers.

Lumine was an endless source of curiosity. Everything fascinated her, every strange instrument in Albedo’s lab, every chemical reaction, the shimmering liquids in glass vials, the intricate symbols etched into his research notes, every scrap of knowledge she could pry from his mind. Even the simple act of speaking was still new to her, and though her words sometimes tumbled out in a peculiar, mismatched way, that young woman was relentless in her questioning.

"Why is this bubbling?"

"What happens if I mix these?"

"Why do you look like that when you think?"

It never ended.

At first, Albedo found her enthusiasm endearing, even oddly amusing, answering her with the patience of a seasoned teacher. But it didn’t take long for him to realize that Lumine’s curiosity was boundless, not just in the things she wished to learn, but in the attention she demanded. When he needed to focus on his experiments, to carefully measure reagents or record delicate results, Lumine was still there, demanding his care. And when she didn’t get it?

That woman hated being ignored. If Albedo ever dared to turn his focus elsewhere, she would make sure to drag it back to her, one way or another. It started with insistent tugging at his sleeve, then persistent questioning, her voice growing louder and more urgent the longer he failed to respond. And when those didn’t work? Then came the destruction; glass shattered, papers scattered, carefully calibrated instruments knocked askew, ink splattered across his carefully recorded notes. Delicate equipment, pieces he had spent weeks, if not months refining suddenly found itself striked to the ground in the wake of her frustration. If he turned his back for too long, Lumine would throw a tantrum, huffing and stomping as if she could will his focus back onto her. And when tantrums alone didn’t work, the mess she brought escalated, spilling liquids, toppling beakers, sometimes even outright grabbing his work and flinging it aside. If denied attention, Lumine didn’t simply sul; she retaliated.

The first few times, Albedo tried to reprimand her, using a pondered authority. His voice had taken on that careful, measured sternness he used when scolding Klee for her reckless explosions, whenever her enthusiasm turned reckless when his younger sister was younger.

"Lumine, you can’t break things just because you want my attention."

But the golden haired woman only glared up at him, her chestnut eyes gleaming with defiance. Then, the next time the alchemist ignored her for too long, she broke something more valuable, as if testing whether his rules truly applied to her or not. That discipline only fueled the rebellion. If he told her not to do something, Lumine would do it twice as much, staring at him defiantly as if daring him to stop her. Eventually, Albedo had to accept a painful truth: Lumine would never change. It became clear, after a handful of ruined experiments, that reprimanding her was a fruitless endeavor. No amount of logical explanation, no carefully worded reasoning about the importance of patience, would ever deter her. No explanation of "This experiment is important, please be patient." would ever stop her. She was a force of nature, one that he simply had to work around. Lumine was not one to wait. She was not one to be ignored. The lab, once an orderly sanctuary of precision, slowly became something else. A disaster zone. Cabinets missing their doors, papers littering the floor, bits of broken glass swept hastily into corners, stacks of notes displaced, fragile instruments set aside where they were less likely to be destroyed, shelves rearranged to keep the most breakable items out of reach. Albedo could only sigh as he salvaged what he could, shaking his head at the wreckage left in her wake.

The wise alchemist had to resort to the same ploy he used with Klee many years earlier: hanging a sign on the door of the workshop while he was working, so Lumine could understand that there was a reason if the door was locked. At first she threw tantrums, screaming like a child, then her tactic became destroying the rest of the house. Albedo, worried that Lumine could even get to the point of hurting herself if left unsupervised for too long, came up with the idea of leaving her some “homework”, something to study and with keeping herself busy while he had to work. Against all his expectations, Lumine was quite intrigued by the topics he assigned her. She tried her best to meet her master's expectations, completing all the work Albedo assigned her. Using this strategy, Lumine learned a lot of valuable information with such incredible speed in a brief amount of time.

Despite all the mess, despite the frustration, there was something almost… endearing about it. Albedo always found himself making allowances for that girl. Despite all her chaos, Lumine listened. Every answer the Kreideprinz gave, every patient explanation about why a chemical changed color, why certain metals conducted energy, why the stars burned in the sky or the mysteries of the constellations, she absorbed it all, like a sponge drinking in water. As much as she craved his attention, Lumine also craved knowledge. Albedo found himself, more often than not, pausing his work to explain things, answering her endless stream of "why's" and "how's," knowing full well that in the moment he'd have stopped, something else would end up broken. Lumine was exhausting,unpredictable, at times infuriating, she was also impossible to ignore. But for all the mess she caused, she always listened.

Despite that funny, somehow warm routine, Albedo never allowed himself peace. His mind, ever restless, was consumed by a singular obsession: restoring Lumine’s memories. He spent countless hours in his lab, eyes scanning over research notes, fingers stained with ink as he scribbled theories and calculations. Every failed attempt only spurred him to push harder, to delve deeper into the mysteries of the Art of Khemia, as if somewhere within its forbidden knowledge lay the key to bringing Lumine back in full to him. His work became his existence, his thoughts endlessly circling the same question: Where had he gone wrong? Lumine was alive, her body was whole, her soul tethered to this world, but she was not the same. The spark that once defined her was dimmed, flickering in and out of reach. Her gaze, though filled with curiosity, lacked recognition. And Albedo, no matter how much he tried to convince himself otherwise, could not accept it. It was like she wasn't the same person he fell in love with decades ago, but every time he chased away this thought.

The experiments were meticulous, precise, driven by an urgency he could not shake. Potions, rituals, alchemical transmutations, each test carried out with the utmost care, each failure met with gritted teeth and renewed determination. At first, Albedo was careful to shield Lumine from the weight of his desperation. He spoke to her in soft reassurances, masking his exhaustion behind a calm demeanor. But no amount of control could hide the dark circles beneath his teal eyes, the rigid set of his jaw whenever an experiment yielded nothing but silence. Lumine watched him with quiet confusion, sensing the depth of his frustration but not fully understanding it. She would tilt her head, studying him as her master paced the lab, muttering theories under his breath. Occasionally, she would reach out, fingers brushing against his sleeve in a tentative attempt to pull him from his thoughts.

"Why do you look so sad?" She once asked, her voice uncertain, as if she was struggling to grasp the meaning of the question herself.

Albedo had frozen at her words, staring at her as if she had struck him. Then, with a forced smile, he merely shook his head and returned to his work.

It wasn’t just her memories that were missing. The realization crept in slowly, dread settling deep within Albedo’s bones. Lumine’s soul itself was fractured, as if some vital pieces had been left behind, lost in the void between life and death. He had brought her back, but not completely. She was like a mirror that had been shattered and imperfectly pieced together, some fragments forever gone. The weight of it was crushing. His mind refused to accept the possibility that this was irreversible. There had to be a way. There had to be something he hadn’t considered yet. He worked harder, slept less, ate only when his body became exhausted. Even when his hands trembled from exhaustion, even when the ink on his pages blurred from tired eyes, he continued.

But for all his efforts, Lumine remained the same. Despite it all, she sought him out. Even without her memories, without the experiences that had once shaped her, Lumine was drawn to him. When Albedo disappeared into his work for too long, she would come find him. She would sit in the lab, watching him with patient, quiet fascination, or tug at his sleeve when he had gone too long without acknowledging her presence. She did not know why she trusted that man, only that she did, he was all she ever had, her only family. Perhaps, on some level, something in her remembered. Or perhaps it was simply that Albedo, for all his silence and brooding intensity, was a constant, a presence that felt safe. She did not understand the grief in his eyes when he looked at her like that, she did not understand the weight that lonely alchemist carried in his heart. But she stayed by his side nonetheless.

When Rhinedottir, Albedo's mother and creator, discovered what her former apprentice had done, her reaction was anything but simple.

The cryptic alchemist returned to the nation she had lived in for many centuries ago, after the war against the gods ended and Khaenri’ah got as stable as before. Although the relationship between her and Albedo, “her most successful son”, has always been complicated, the two had learned to coexist almost peacefully together. Both were highly respected alchemists in their homeland, each working on their own projects, though often combining their miraculous faculties. Rhinedottir saw Albedo as a man now, he learned a great deal from her teachings and became an alchemist in her own wake. Despite Rhinedottir being as cold as ever, she was more than satisfied with how far her best creation had come. Albedo, who had always longed to be reunited with her, learned to acknowledge his master's mistakes, without ignoring that this woman was the closest family he could ever have. The homunculus was silently grateful for his creator eventually coming back, and while her attitude was as icy as ever, something changed. Rhinedottir knew how to show that she was still a mother, even if in her own way.

Despite being aware of the witch's vast knowledge, Albedo had always kept his greatest plan a secret from her, even though she herself could have been able to help him with her wealthy skills. But he couldn't imagine her fury when she’d found out, after all, there was a part of him that still feared her reaction and judgment, however inevitable.

But now the woman stood just before him, in the middle of his lab. Eyes narrowed, her presence as imposing as ever. The silence between them stretched thick with tension. When Rhinedottir finally spoke, her voice was laced with both disapproval and something more, something contemplative. "You used the Art of Khemia… to create life. Without my knowledge. Without my guidance." Shock and fury battled for dominance in her expression, yet beneath the surface, a more subtle emotion flickered, one that Albedo recognized all too well. A hint of pride, the same rare light that rarely manifested back in the days when he was still an apprentice seeking alchemy mentorship, when he was still learning about the world in the early years of his long existence. Rhinedottir's words were measured, but there was no mistaking the sharp edge to them. The Kreideprinz had expected her anger, and he was not disappointed. The older alchemist continued, stepping forward, her gaze scrutinizing her child like one of her unfinished experiments, a feeling that Albedo already knew too well. "Do you even understand what you’ve done? Do you understand the consequences you may have unleashed?"

Albedo, ever composed, stood his ground. He did not flinch under her scrutiny, though he could feel the weight of it pressing down on him. Of course he had already anticipated this reaction. "I understand perfectly," The man replied evenly, though a part of him wondered if he truly did. "I took every precaution-"

"Precaution?" Rhinedottir’s scoff was bitter. "You dare speak of precautions when you tamper with the fundamental laws of existence? I taught you to be cautious, to understand the seriousness of the Art of Khemia, and yet you…" She exhaled sharply, shaking her head, her voice no less serious. She was furious. Yes, Albedo knew she would be, but there was something else in her gaze. Beneath the indignation, beneath the rebuke, was a glimmer of something almost… admiring. "You wielded it with reckless abandon. You ignored the risks. You defied discipline, and for what? Love? Grief?"

Albedo’s hands clenched at his sides. He had nothing to say to that. No words that would make her understand. But she already did. Rhinedottir studied her perfect creation for a long moment, her expression unreadable. Then, slowly, her lips curled, not quite into a smile, but into something close.

"Impressive…" The woman murmured, almost to herself, while watching the other homunculi in the room next Albdo’s lab, from the crack in the door she could glimpse Lumine dancing with a broom, humming a playful tune to herself as she was immersed in her little world. That sentence sent a shiver through Albedo. It was not a compliment, not exactly. It was an acknowledgment, a grudging respect for the audacity of what he had done, for the skill it required. But the moment passed, and her expression hardened once more.

"Listen to me, Albedo." Rhinedottir’s tone was firm, brooking no argument. "You will take responsibility for what you have created. This is not an experiment you can discard when it becomes inconvenient." Sounded almost hilarious, said by her, the same woman who had abandoned him, as well as her other “failed” experiments. But albedo did not dare to protest about it.

The younger alchemist bristled at her implication. "I never intended-"

"Ensure that Lumine is safe." Rhinedottir interrupted. "That she is stable, that she does not become… something beyond your control." The implications of those words were clear, after all, they both were homunculi. It was a brilliant paradox; an artificial being created by another artificial being, a synthetic life generated by another synthetic one. A snake biting its own tail.

Albedo met her gaze, his resolve unwavering. "I will."

A beat of silence passed between mother and son, heavy with unspoken words, but clear as if they had been shouted. Then, with a final glance at him, in one last, lingering moment of scrutiny, Rhinedottir turned away.

"See that you do." She warned, and just like that, the woman made it clear that their conversation was over. Albedo lowered his head slightly, not daring to twist the finger in the wound any further.

Before leaving the alchemist's emporium, Rhine stood in front of Lumine, deeply staring into her golden eyes as the girl returned the glare with puzzled look, only able to produce a confused sound back. For a moment, albeit very brief, Rhinedottir's eyes softened before lending a hand on Lumine’s shoulder. Perhaps for a moment the alchemist Gold remembered something, although distant. Then she turned away, enveloped in her icy aura as ever as the sound of her heels followed her out of the door.

Albedo kept standing there for a little more after his master had left, his thoughts a whirlwind of guilt, defiance, and something else. He couldn't help but think about that look, somehow... proud? He had never seen her like that in his entire life. Something that felt an awful lot like vindication.

Once they were both alone Lumine approached her teacher with uneven steps, her voice carrying a peculiar lilt as she spoke. "AU-be-do!" The girl enunciated in a funny, exaggerated way. "Who was that odd person who just passed by?"

Albedo turned toward her, an amused yet still shaken expression crossing his face. He recognized that she was referring to Rhinedottir, but for a brief moment he hesitated. How could he explain her in a way that Lumine would understand? The alchemist studied her face, innocent yet inquisitive, her wide eyes filled with curiosity rather than wariness. With a small sigh, he finally answered. "That woman… is someone very important to me. Her name is Rhinedottir, and she's the one who created me."

Lumine blinked, tilting her head as she processed his words. "Important…" She hummed back, repeating the word as if tasting it on her tongue, though the sentence remained incomplete in her mind.

Albedo nodded, a faint smile tugging at his lips at her attempt to grasp the concept. "Yes, important." He clarified gently. "She's my creator, and she taught me many things." For a moment, Albedo considered how much he should tell her. Lumine was technically still mentally young, how much of his past, of Rhinedottir’s role, could she truly comprehend?

Lumine’s expression remained thoughtful as she repeated his words, albeit with a furrowed brow. "She created you…" Her small fingers fiddled with the hem of her skirt before looking up again. "Then… Why was she angry?"

There it was. The question Albedo had been dreading. She was referring to Rhinedottir’s earlier fury, the way her sharp words had lashed at him like a whip, it was obvious that from the other room Lumine had heard something, after all, she wasn’t any fool. The blonde man let out a slow breath, trying to choose his words carefully. "It’s… complicated." His voice waw measured. "My master was angry because she was worried about me. She didn’t want me to do certain things because they could be dangerous…"

Lumine’s frown deepened, confusion flickering across her features. Albedo hesitated before bringing himself closer to her. "She’s just… protective, I suppose. The way a mother would be angry if her child did something reckless."

For a few moments, the younger homunculi remained silent, processing his words, when she spoke her voice was serious. "And what did you do wrong? Do I have to be angry too?"

Albedo let out a small laugh at her question, shaking his head. There was something both endearing and worrisome about her directness. His hand reached out, fingers ruffling through her hair in a familiar, affectionate gesture. Lumine, for once, didn’t push him away. "No, no, you don’t have to be angry… " He reassured her, his tone gentle. "I did something I shouldn’t have, and that’s why she was upset. But you haven’t done anything wrong, my dear. Don’t worry, alright?" Albedo's voice was softer now. "Just focus on learning and growing."

Lumine nodded solemnly, as if absorbing his words like a sacred promise. Then, with a shift in mood, she looked up at him with wide eyes.

"Would you give me a hand with that book you gave me to read?"

Albedo’s smile widened at the request. It pleased him to see her so eager to learn. "Of course, my dear." The Kreideprinz replied, settling beside her. "I’d be glad to help. What part are you having trouble with?"

The blonde girl wasted no time in opening the book, pointing to a paragraph that had given her trouble. As Albedo guided her through the sentences, correcting her pronunciation and explaining the meanings of unfamiliar words, a sense of normalcy returned, if only briefly. He forced himself to focus on the present, to be patient as Lumine stumbled through her reading. But beneath his calm exterior, his thoughts remained tangled. The turmoil in his heart had not disappeared. Even as he sat beside his most sacred treasure, helping that innocent girl navigate the words on the page, his mind swirled with the weight of Rhinedottir’s anger, the burden of his own decisions, and the uncertainty that loomed ahead. The older alchemist's fingers tensed slightly over the edge of the book. He had told Lumine not to worry, but he knew, deep down, that things would not remain this peaceful forever.

If only Lumine could have known.

couldn't find the artist, please if you know tell me!

#albedo#genshin impact#albedo kreideprinz#albedo x reader#albedo genshin impact#albedo x traveler#albedo x lumine#albelumi#albedo fanfic#genshin x reader#genshin impact fanfics#female reader#genshin fanfic#genshin impact fanfiction#albedo x you#albedo kreideprinz fluff#albedo kreideprinz x reader#genshin x you#genshin impact x reader#genshin x y/n#genshin impact albedo#angst#genshin angst#albedo x female reader#genshin impact imagines#genshin impact scenarios#genshin impact fanfictions#✨#アルベド

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are, roughly speaking, three schools of doctrine on nuclear defense. The first and dominant is the line of thought emanating from John von Neumann, father of the computer: “Mutual assured destruction” (MAD), the certainty of catastrophic nuclear reprisal, will deter wars between nuclear-armed powers. This has in practice been the actual frame for nuclear weapons policy since the early days of the Cold War. The second line, from the physicist Herman Kahn, posits a winnable nuclear war; in the era of the nuclear submarine, a true decapitation strike seems less viable than it did in 1960.

The third accepts the premise of MAD, but inverts the conclusion: The threat of nuclear reprisal discourages nuclear war, but does not preclude the possibility of purely conventional conflict between nuclear-armed powers. An early and prominent exponent of this heterodoxy was the British Member of Parliament Enoch Powell, who believed that the drawdown of conventional military forces was based on a misguided trust in the security afforded by the bomb. Already in 1949, he wrote, “When atom bombs are a stock line in the principal arsenals of the world, the absolute certainty of reprisals reduces the likelihood of their being used, though it cannot, of course, eliminate the possibility. Nevertheless, the atom bomb in World War III may be like poison gas in World War II – a constant potential menace, but never an actual one.”

More pointedly, during a 1970 parliamentary debate, he said, “I have always regarded the possession of the nuclear capability as a protection against nuclear blackmail. It is a protection against being threatened with nuclear weapons. What it is not a protection against is war.” Powell’s view was not taken terribly seriously at the time, or after; indeed, the Thatcher government was preparing to draw down its Atlantic fleet when the Falklands War broke out, an infelicitous bit of timing on the Argentine part.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Dobrinka Tabakova : Cello Concerto: II. Longing ( String Paths 2013 ).

El segundo movimiento del Cello Concerto de Dobrinka Tabakova, titulado Longing, se presenta como una de las expresiones más refinadas del lirismo contemporáneo. Mediante un lenguaje tonal claro, pero matizado con una gran sutileza, la compositora desarrolla un discurso contenido, casi ascético, que no rehúye la emoción, sino que la depura. El violonchelo, con una voz profunda y orgánica, se mueve entre líneas amplias y silencios cargados de sentido, sostenido por una orquesta que no acompaña, sino que arropa. BBC Music Magazine subraya que Tabakova “construye paisajes emocionales que conmueven sin caer nunca en el sentimentalismo”, una cualidad que define el corazón de Longing: no es una manera de exponer el anhelo, sino una forma de traducirlo con honestidad y contención. La interpretación recogida en el álbum String Paths (ECM, 2013), bajo la producción de Manfred Eicher, potencia esta dimensión introspectiva. El sello ECM, fiel a su estética sonora, ofrece un espacio acústico en el que cada matiz, cada resonancia, adquiere un gran valor poético. La crítica de The Guardian destaca que “el sonido parece emerger del silencio con una delicadeza que conmueve por su sobriedad”, y añade que la música de Tabakova “respira como un organismo vivo, en constante tensión entre lo emocional y lo espiritual”. El violonchelo solista no se impone: fluye con serenidad, sin urgencia, revelando una interpretación que prioriza la escucha interior por encima del virtuosismo. Por su parte, Gramophone señala que “Tabakova consigue lo que muchos persiguen sin éxito: un lenguaje accesible sin concesiones, íntimo sin caer en la introspección vacía”. Esa capacidad para mantener la claridad formal mientras se alcanza una profundidad expresiva genuina es lo que convierte a Longing en un movimiento especialmente relevante dentro del repertorio concertante del siglo XXI. En un entorno musical a menudo dominado por la complejidad o la exuberancia, esta obra ofrece algo más raro: una pausa. Una invitación al recogimiento. Un lugar donde la música no se limita a sonar, sino que nos observa en silencio.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nicopeia Icon of San Mark's in Venice

Icono Nicopeia de San Marcos de Venecia

Icona Nicopea di San Marco a Venezia

The icon before the robbery. Missing are strands of pearls that hung from the round hooks on either side under the initials. The precious jewellery, later recovered, is currently on display in the Treasury of Saint Mark's.

El icono antes del robo. Faltan los hilos de perlas que colgaban de los ganchos redondos a ambos lados bajo las iniciales. Las preciosas joyas, recuperadas posteriormente, se exponen actualmente en el Tesoro de San Marcos.

L'icona prima del furto. Mancano i fili di perle che pendevano dai ganci rotondi ai lati sotto le iniziali. I preziosi gioielli, poi recuperati, sono attualmente esposti nel Tesoro di San Marco.

(English / Español / italiano)

It was probably created in the early 12th century, specifically to follow the emperor and the army on campaign. Perhaps it was made for John II himself, who spent most of his reign in the field, fighting the empire's many enemies. This icon traveled with John II and his family throughout his military campaigns. When John returned to Constantinople for a parade celebrating a military victory he gave up his gold, silver and ivory chariot and had the icon placed in a kiot (decorated theca for preserving and displaying icons) that stood in his place. The victory john was celebrating was the recapture from the Muslim Turks of the ancestral castle of the Komnenian family, Kastamon. John believed the Virgin was personally responsible for this important victory.

The icon was taken by bloodied Crusader soldiers in 1204 in hand-to-hand combat with the defenders of the city at the Pantepotes Monastery which was and the last stand of the Byzantines.Taken as spoils of war by the Venetians, the old and blind Doge Dandolo, who died in Constantinople in 1205, would immediately send the icon to Venice as the most important trophy of the destruction of Constantinople. Era il simbolo di come gli equilibri di potere si fossero appena spostati da Bisanzio sul Corno d'Oro alle lagune di Venezia, Dio aveva ora trasferito la Sua benedizione da Costantinopoli a Venezia con la forza delle armi.

In February 1438 a large delegation from Constantinople arrived in Venice headed for for a great church council negotiating the union of the churches that was held in Italy. The ancient Patriarch Joseph II along with a group of clerics and nobles visited Saint Mark's and saw the treasures that had been looted in 1204. Here is an account of the visit:

... We also looked at the divine icons from what is called the holy templon... These objects were brought here according to the law of booty right after the conquest of our city by the Latins, and were reunited in the form of a very large icon on top of the principal altar of the main choir... Among the people who contemplate this icon of icons, those who own it feel pride, pleasure, and delectation, while those from whom it was taken — if they happen to be present, as in our case—see it as an object of sadness, sorrow, and dejection. We were told that these icons came from the templon of the most holy Great Church. However, we knew for sure, through the inscriptions and the images of the Komnenoi, that they came from the Pantokrator Monastery.

***

Probablemente se creó a principios del siglo XII específicamente para seguir al emperador oriental y a su ejército en las campañas bélicas. Tal vez se hizo para el propio Juan II Comneno, que pasó gran parte de su reinado en el campo de batalla, luchando contra los numerosos enemigos del imperio; este icono viajó con Juan II y su familia durante sus campañas militares. Cuando Juan regresó a Constantinopla para un desfile en celebración de una victoria militar, renunció a su carro de oro, plata y marfil e hizo colocar el icono en un kiot (teca decorad para conservar y exponer iconos) que había en su lugar. La victoria que Juan celebraba era la reconquista del castillo ancestral de la familia Comnena, Kastamon, a los turcos musulmanes. Juan creía que la Virgen era personalmente responsable de esta importante victoria.

En la Cuarta Cruzada, en 1204, el icono fue tomado por los soldados cruzados tras un combate cuerpo a cuerpo con los defensores de la ciudad de Constantinopla, cerca del monasterio de Pantepotes, que constituía la última resistencia de los bizantinos. Tomado como botín de guerra por los venecianos, el anciano y ciego dux Dandolo, que murió en Constantinopla en 1205, enviaría inmediatamente el icono a Venecia como el trofeo más importante de la destrucción de Constantinopla. Era un símbolo de cómo el equilibrio de poder acababa de pasar de Bizancio en el Cuerno de Oro a las lagunas de Venecia, Dios había transferido ahora su bendición de Constantinopla a Venecia por la fuerza de las armas.

En febrero de 1438, una gran delegación de Constantinopla llegó a Venecia de camino a un gran concilio eclesiástico celebrado en Italia para negociar la unión de las iglesias. El antiguo Patriarca de la Iglesia bizantina José II, junto con un grupo de clérigos y nobles, visitó San Marcos y vio los tesoros que habían sido saqueados en 1204. He aquí un relato de la visita:

.... También hemos contemplado los iconos divinos de lo que se llama el sagrado templon...Estos objetos fueron traídos aquí según la ley del botín inmediatamente después de la conquista de nuestra ciudad por los latinos, y fueron reunidos en forma de un icono muy grande en lo alto del altar mayor del coro principal.... Entre las personas que contemplan este icono de iconos, los que lo poseen sienten orgullo, placer y deleite, mientras que los que se lo han llevado -si están presentes, como en nuestro caso- lo ven como objeto de tristeza, pena y abatimiento. Nos dijeron que estos iconos procedían del templón de la Santísima Gran Iglesia. Pero nosotros sabíamos, por las inscripciones y las imágenes de los comnenes, que procedían del monasterio del Pantocrátor.

***

Probabilmente fu creata all'inizio del XII secolo appositamente per seguire l'imperatore d'Oriente e l'esercito in campagna bellica. Forse è stato realizzato per lo stesso Giovanni II Comneno, che trascorse gran parte del suo regno sul campo, combattendo i numerosi nemici dell'impero; questa icona viaggiò con Giovanni II e la sua famiglia durante le sue campagne militari. Quando Giovanni tornò a Costantinopoli per una parata che celebrava una vittoria militare, rinunciò al suo carro d'oro, argento e avorio e fece collocare l'icona in un kiot (teca decorata per conservare ed esporre icone) che stava al suo posto. La vittoria che Giovanni celebrava era la riconquista del castello ancestrale della famiglia Comnena, Kastamon, da parte dei turchi musulmani. Giovanni credeva che la Vergine fosse personalmente responsabile di questa importante vittoria.

Nella quarta crociata, nel 1204, l'icona fu presa dai soldati crociati dopo un combattimento corpo a corpo con i difensori della città di Costantinopoli, presso il Monastero di Pantepotes che fu l'ultima resistenza dei Bizantini. Presa come bottino di guerra dai veneziani, il doge Dandolo, vecchio e cieco, che morì a Costantinopoli nel 1205, avrebbe subito spedito l'icona a Venezia come il trofeo più importante della distruzione di Costantinopoli. Era il simbolo di come gli equilibri di potere si fossero appena spostati da Bisanzio sul Corno d'Oro alle lagune di Venezia, Dio aveva ora trasferito la Sua benedizione da Costantinopoli a Venezia con la forza delle armi.

Nel febbraio 1438 una numerosa delegazione da Costantinopoli arrivò a Venezia diretta a un grande concilio ecclesiastico che si tenne in Italia per negoziare l'unione delle chiese. L'antico Patriarca della Chiesa Bizantina Giuseppe II, insieme ad un gruppo di chierici e nobili, visitò San Marco e vide i tesori che erano stati saccheggiati nel 1204. Ecco un resoconto della visita:

.... Abbiamo anche guardato le icone divine da quello che viene chiamato il sacro templon...Questi oggetti furono portati qui secondo la legge del bottino subito dopo la conquista della nostra città da parte dei Latini, e furono riuniti sotto forma di una grandissima icona in cima all'altare maggiore del coro principale.... Tra le persone che contemplano questa icona delle icone, chi la possiede prova orgoglio, piacere e diletto, mentre a chi l'ha prelevata – se è presente, come nel nostro caso – la vede come un oggetto di tristezza, tristezza e sconforto. Ci è stato detto che queste icone provenivano dal templon della santissima Grande Chiesa. Ma dalle iscrizioni e dalle immagini dei Comneni sapevamo con certezza che provenivano dal monastero del Pantocratore.

Source text extracted from: pallasweb.com

photos: pallasweb.com

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

2. Explorando la Oscuridad Interior (análisis capítulos I-V)

Hola mi gente, hoy les traigo una actualización en la que haré un breve resumen de los primeros cinco capítulos de El túnel. Además, compartiré mis impresiones sobre los personajes, los temas clave y algunos detalles que me parecieron interesantes a lo largo de la lectura.

Capitulo I

En este capítulo se introduce a Juan Pablo Castel, quien, desde el comienzo, revela que ha asesinado a una mujer llamada María Iribarne. Esta confesión inicial otorga un tono sombrío a la historia y deja entrever la personalidad del protagonista.

Al ser un capítulo introductorio, no hay mucho más que resaltar además de la personalidad obsesiva y atormentada del protagonista y la impactante revelación de su crimen, que se desarrolla en detalle más adelante en el libro.

Capitulo II

En este capítulo, Castel nos revela más sobre su forma de pensar y su estado mental, mostrando su incapacidad para conectar con los demás y su visión pesimista del mundo. Expone su lucha por encontrar sentido en su entorno y en sus relaciones, lo que muestra su creciente desesperanza y la distancia emocional que siente respecto a las personas a su alrededor.

Este capítulo y el anterior me han dejado más claro el tono que tendrá la historia del crimen, revelando la personalidad obsesiva de Castel y su visión del mundo, que no comparto. En este punto, empiezo a hacerme algunas preguntas, como qué hizo que Castel tuviera esa visión del mundo o si su crimen es alguna consecuencia de ese pensamiento.

CAPITULO III

En este capítulo Castel narra su encuentro con María, una mujer que parece ser la única capaz de comprender su visión del mundo al ver su obra. La historia se centra en la relación entre ellos y en cómo esta conexión consume cada vez mas a Castel hasta el punto de obsesionarse.

Por fin comienza la historia de cómo María y Castel se conocieron. No esperaba que Castel se obsesionara tanto con María solo por haber visto su obra, al punto de buscarla durante meses cerca del lugar donde vio su obra y dedicarse exclusivamente a hacer obras para que pueda volver a verla.

CAPITULO IV

En este capítulo Castel se encuentra con María en la calle y comienza a describir sus emociones y pensamientos con más profundidad. Castel reflexiona sobre cómo María se ha convertido en una figura central en su vida, y explora sus sentimientos de posesividad y obsesión hacia ella.

Este capítulo revela con mayor claridad la personalidad obsesiva de Castel, ya que nos detalla sus pensamientos y planes acerca de María, además de cómo piensa comportarse al verla. También profundiza en su aversión hacia los grupos sociales (algo con lo que coincido) y en su tendencia a sobrepensar las cosas.

CAPITULO V

En este capítulo Castel sigue explorando sus obsesiones y su creciente paranoia. Su relación con María se vuelve más compleja y problemática, reflejando su desesperación y su incapacidad para encontrar paz al no saber como entablar una conversación con María.

Acá nuevamente se muestra cómo Castel no puede dejar de pensar en María y en imaginar situaciones en las que hablan o se conocen. Esto me deja más preguntas, como qué va a hacer Castel para acercarse a María y por qué termina matándola, pero eso lo responderé cuando acabe el libro (supongo).

Y bueno, ese fue el análisis de los primeros cinco capítulos de El túnel, mientras avance en el libro, iré analizando algunos capítulos y tratando de resolver las dudas que me he planteado en estos capítulos.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walker Percy statue in Bogue Falaya Park, Covington, Louisiana

“A Talk with Walker Percy

Zoltán Abádi-Nagy

The Southern Literary Journal, 6 (Fall 1973)

Q: You maintain that perhaps the best way of writing about America in general is to write with authenticity about one particular part of America. By extension this means that, likewise, your attitude and reaction toward philosophical questions of universal human importance— toward the question of the human predicament, to use the term of your philosophy—will be that of an American. Is that correct?

A: I think that is true. My novels have more a European origin than American. They are so-called philosophical novels which is probably a bad word. But you know that the first half of your question is quite true. The greatest exponent of this was Faulkner who concentrated on a small village in Mississippi. It is true that I am interested in philosophical, religious issues and in my novels I use the particular in order to get at the general issues. For example, The Moviegoer is about New Orleans, one part in New Orleans, a young man in New Orleans. The conflict is a hidden ideological conflict involving, on the one hand, what I call Southern stoicism. I have an uncle whose hero was Marcus Aurelius. The other ideology is Christian Catholic. The third: the protagonist is in an existentialist predicament, alienated from both cultures.

Q: What in your view is it in America that makes an existentialist today? What facets of the American intellectual climate, of the American existence in general, are favorable to existentialist thinking?

A: I think in America the revolt is less overtly philosophical. It is a feeling of alienation from American suburban life, the suburb, the country-club, the business community. There is a difference between my protagonists and the so-called counter culture. Many young people revolt in a purely negative way, oppose their parents' culture; whereas the leading characters in my books are much more consciously embarked on some sort of search. I am telling you that because I would not want you to confuse the characters of the counter culture with my characters. One of their beliefs is that the American scene is phony, and their revolt is to seek authenticity in drugs, sex, or in a different kind of communal existence. The characters in my books are embarked on a much more serious search for meaning.

(…)

Q: Your view of life in your literary works is very close to the absurdist view, but the term 'absurd' and the whole Camus terminology hardly ever appears in your philosophical essays. Does this coincide with your preference for Marcel's Catholic version of existentialism as opposed to the post-Christian character of the meaninglessness of Sisyphus' situation?

A: Yes, that is correct. I identity philosophically with people like Gabriel Marcel. And if you want to call me a philosophical Catholic existentialist, I would not object, although the term existentialist is being so abused now that it means very little. But stylistically mainly two French novels affected me: Sartre's La Nausée and Camus' L'etranger. I agree with their novelistic technique but not with their absurdist view.

Q: Is not your third novel, Love in the Ruins, with its Layer I and Layer II—the social self and the inner, individual self—a comic attempt to solve Marcel's dilemma about this separation?

A: You are right. This is a comic device to get at what, ever since Kierkegaard, has been called the modern sickness: the disease of abstraction. I think in the novel Dr. More calls the illness angelism-bestialism. There is nothing new about this. It had been mentioned by many writers in various ways. Pascal said that man is both not quite as high as an angel and not quite as low as a beast. So Dr. More is aware of this schism in consciousness. He talks about the modem mind which, as he sees it, abstracts from the world, from itself, and manages to lose touch with reality.

(…)

Q: Much of it, especially in Love in the Ruins, seems to be a social problem viewed from an existentialist viewpoint of the human predicament. Actually, this is a kind of movement I notice in your works: an increasing awareness of how much the social predicament has to do with the human predicament. If Binx in The Moviegoer was suffocating in an adverse climate of malaise which was a social phenomenon, he was not much aware of its having to do with society; he was not concentrating on things like the social self as later Dr. More is in Love in the Ruins. Was this an intentional change on your part or was the movement towards the concept of malaise as a social product spontaneously developing through the inner logics of these relations?

A: It was a conscious change. Love in the Ruins was intended to take a certain point of view of Dr. More's and from it to see the social and political situation in America. Unlike Binx, whose difficulties were more personal, Dr. More finds himself involved in contemporary issues: the black-white conflict and the problem of science, scientific technology which is treated as a sociological reality today. Both the good and bad of it. I really use this to say what I wanted to say about contemporary issues. About polarization; there are half a dozen of them: black-white, North-South, young-old, affluent-poor, etc. And do not forget that at the end of Love in the Ruins there is a suggestion of a new community, new reconciliation. It has been called a pessimistic novel but I do not think it is. A renewed community is suggested. The suggestion is in the last scene which takes place in a midnight mass between a Christmas Saturday and Sunday. The Catholics, the Jews come to the midnight mass, also the unbelievers in the same community. The great difference between Dr. More and the other heroes is that Dr. More has no philosophical problems. He knows what he believes.

Q: Is it a religious reconciliation then?

A: Yes, that is the case. This was meant for Southerners in particular and for Americans in general.

Q: Binx in The Moviegoer and Barrett in The Last Gentleman do not seem to have the set of positive values needed for absurd creation as conceived by Camus to create their own meaning in meaninglessness. Is this connected with your idea of the aesthetic reversion of alienation, i.e. by communicating their alienation they get rid of it?

A: Yes, there is something there. In the case of Binx it is left open. The ending is ambiguous. It is not made clear whether he returns to his mother's religion or takes on his aunt's stoic values. But he does manage to make a life by going into medicine, helping Kate by marrying her. I suppose Sartre and Camus would look on this as a bourgeois retreat he had made.

Q: How do you look on it?

A: Well, I think he probably . . . as a matter of fact the last two pages of The Moviegoer were meant as a conscious salute to Dostoevski, in particular to the last few pages of The Brothers Karamazov. Very few people notice this.

Q: To me the most striking difference between the European and the American absurdist view is the ability of the American to couple the grim seriousness with hilarious humor, to turn apocalypse into farce. In comparison, Beckett, for all the grim comedy which is there, is a sheer tragic affair. Can you think of some explanation for this?

A: That is a good question and I can only quote Kierkegaard, who said something that astounded me and that I did not understand for a long time. He spoke of the three stages of existence: the aesthetic, the ethical, the religious. When you pass the first two you find yourself in an existentialist predicament which can be open to the religious or the absurd. He equated religion with the absurdity. He called it the leap into the absurd. But what he said and was puzzling to me was that, after the first two, the closest thing to the third stage is humor. I thought about that for a long time. I cannot explain it except I know it is true.

There is another explanation, too, of course. Hemingway once said: all good American novels come from one novel written by a man named Mark Twain. With Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain established the tradition of this very broad and satirical humor. I think the American writer finds it natural to use humor both in his satire and in describing even the worst predicament of his main character. In this country we call it black humor: disproportion between the gravity of the character's predicament and the hilarity of the humor with which it is treated. Vonnegut uses this a good deal.

Q: Richard B. Hauck in A Cheerful Nihilism points out how Franklin, Melville, Twain, Faulkner have shown that the response to the absurd sense can be laughter. At one point Binx becomes aware of the similarity of his predicament to that of the Jews. "I accept my exile," he says. Whether we accept this as his affirmation of life in its absurdity or not, what follows is comedy. Could you agree that this comedy as well as Franklin's, Melville's and the others' could be regarded as the absurd creation of the American Sisyphus as opposed to the serious defiance of Camus' king?

A: I do not know if I would go that far. It may be much simpler. There is an old American saying that the one way to stop crying is to laugh. Binx says, "I feel more homeless than the Jews." Between him and the Camus and Sartrean heroes of the absurd there is a difference. Camus would probably say the hero has to create his own values whether absurd or not, whereas Binx does not accept that the world is absurd; so he embarks on a search. So to him the Jews are a sign. I think he said, "Lately when I see a Jew on a street I am amazed nobody finds it remarkable. But I find it remarkable. But to me it is like seeing Friday's footprint in the beach. " Of course, he is not sure what it is the sign of. Sartre's Roquentin in La Nausée or Camus' Meursault in L'etranger would not find anything remarkable about a Jew, they would not be interested in him.

Q: In your philosophical essay, "The Man on the Train," you stress the speakability of the commuter's alienation and the fact that the commuter rejoices in this speakability. We can probably add: laughability. Incidentally, you do mention in the same article how Kafka and his friends were roaring with laughter when Kafka read his work aloud to them. Again if we had the answer to how alienation can become a laughing-matter, we would have the key to much of what is recently called black humor.

A: I think you are right. In "The Man on the Train" I was talking about the aesthetic reversal: the alienated commuter feeling totally alienated when reading a book about alienation feels better because there is a communication between himself and the writer.

Q: The forms of alienation you are concerned with in your fiction are all results of the objectification, mechanization of the subjective. Does not this view meet somewhere at a point with Bergson's view of the comic as the mechanical manifested in a living human being?

A: It sounds reasonable but I cannot enlarge on that. I am not familiar enough with Bergson. But to your previous question. Let me finish. It is the first time it occurs to me. You brought it up. Maybe, a person like Sartre spent a lot of time writing in a café about alienated people, the lack of communication, etc., and yet, in doing so, he became the least alienated person in France. By writing he performs a superb act of communication for which he has many readers. So you have a complete reversal. He writes about one thing and reverses it through communication. Here we have the American writer locked in his alienation. But I can envision the American writer getting onto it; by seeing the possibility of communication, exhilaration, his alienation becomes speakable. There can be a tremendous release from that. I have never thought of this before. Nobody knows what is going on when you communicate the unspeakable. This all-important step from unspeakability to speakability is such a triumph that in his own exhilaration the American writer finds it natural to use the Mark Twain tradition of the funny, the humorous.

(…)

Q: Religion reminds me of another tendency I notice in your novels from Binx through Dr. Sutter to Dr. More: the scientist Dr. Percy showing in the novels much more than the Catholic. How would you comment on your religious presence in the philosophical essays the—whole idea of the islander opening all those bottles hoping for 'the message'—and on the absence of practical religion from the novels. I know that religion is there as a theme but with no commitment of the writer in any direction.

A: Well, that is very simple. James Joyce said that an artist must be above all things cunning and guileful and must use every trick in the bag to achieve his purpose. In my view the language of religion, the very words themselves, are almost bankrupt. If you are writing a technical article on philosophy you can use the correct word for the correct meaning. But writing a novel is something different. In my view you have to be wary of using words like 'religion,' 'God,' 'sin,' 'salvation,' ‘baptism' because the words are almost worn out. The themes have to be implicit rather than explicit. I think I am conscious of the danger of the novelist trying to draw a moral. What Kierkegaard called 'edifying' would be a fatal step for a novelist. But the novelist cannot help but be informed by his own anthropology, the nature of man. In this respect I use 'anthropology' in the European philosophical sense. Camus, Sartre, Marcel in this sense can all be called anthropologists. In America people think of somebody going out and measuring skulls, digging up ruins when you mention 'an-thropology.' I call mine philosophical anthropology. I am not talking about God. I am not a theologian.

Q: What I meant was not the question of style and technique explicit or implicit but the religious commitment which is there in your philosophical writings but absent from the novels or always left open at best.

A: As it should be left open in the novel.

(…)

Q: None of the main characters in your three books have problems in making a living. Binx is a successful broker, Barrett inherited from his father, Dr. More from his wife. Do you do this to contrast seeming affluence with emptiness under it?

A: I had not thought about it. Maybe so, maybe also to use it as a device to reinforce the rootlessness. After all if these fellows had been day-laborers working very hard they would have had no time for various speculations.

Q: Does that mean that existentialism has no comment on those who are without these economic means and consequently perhaps in a much more serious predicament—because they have no time for speculations?

A: To that Marx would have an answer, Henry Ford would have an answer, Chaplin would have another, etc. Marx invented the term alienation. . .

Q: He reinterpreted an older concept, he discovered a new explanation for alienation.

A: But it is now transferred to a different class of society in Sartre, Camus. These desperately alienated people are members of a rootless bourgeoisie, not the exploited proletariat.

Q: Your novels demonstrate that to many questions affluence is no answer. Danger of life and the saving of lives often figure in your work as in many other black humorists', too. One can think of Barth's The Floating Opera, The End of the Road, Giles Goat-Boy, Vonnegut's The Sirens of Titan, Mother Night, Cat's Cradle and others, Kesey's two novels, Pynchon's V., Heller's Catch-22 and We Bombed in New Haven, etc. Do you think that this or a similar event of great moment in one's life is necessary to awaken the existentialist hero to his absurd situation and that this somehow is needed to shock him into the feeling of necessity for 'intersubjectivity' and shared consciousness as an escape from 'everydayness'?

A: I think that touches on a subject I have been interested in for a long time—a theme I use in all my novels: the recovery of the real through ordeal. It is some traumatic experience—war, Dr. More's attempted suicide—in each case. You have the paradox here that near death you can become aware of what is real. I did not invent this. Prince Andrey lying at the Battle of Borodino and looking at the clouds, makes a discovery: he sees the clouds for the first time in his life. So Binx is the opposite of Prince Andrey: he watches the dung-beetle crawling three inches from his nose.

Q: Correct me if I overinterpret the difference but now that you make this comparison it occurs to me that perhaps there is some irony here in the way it is an opening up of vision for Andrey towards the clouds, the sky, some magnificence suggested by these, and in the way Binx zooms down on an ugly little dung-beetle.

A: Maybe there is a little twist there. But the point is that a little creature as the dung-beetle is just as valuable as a cloud.

(…)

Q: Ordeal is one existentialist solution to escape from the malaise. How effective do you think the others, rotation and repetition, can be? Is it possible that their effect can be more than temporary?

A: To use Kierkegaard's term, they are simply aesthetic relief, therefore temporary.

Q: Friedman says that distortion can be found on the front page of any newspaper in America today. It is not the black humorist who distorts; life is distorted. Does everyday American reality stir you to write with similar directness? I ask this because once in an interview you appreciated the way Dostoevski was stirred to writing by a news item in a daily paper and because once in connection with Faulkner and Eudora Welty you referred to the social involvement of the writer as useful because social likes and dislikes, you said, can be the passion and energy you write from.

A: I see what Friedman means. Right. The danger with newspapers and TV is that it is all trivial. You remember in Camus' The Fall: we spend our lifetime "fornicating and reading the newspapers.” I think the danger is that you can spend your life reading the New York Times and never get below the surface of current events; whereas in Dostoevski's case—The Possessed—the whole was inspired by a news story in a Russian newspaper. I would contrast the inveterate newspaper reader and TV watcher who watches and watches and nothing happens—he is formed by the media. Dostoevski reads one news story, gets angry and this triggers a creative process.

Q: Intersubjectivity is an escape for Binx from everydayness and the other forms of the malaise, he is certainly not formed by the media. But are his aunt's values cars, a nice home, university degree—somehow recreated through intersubjectivity so that he can go back to these formerly rejected values?

A: Yes, sure. The question is, how much? And whether he did not go a good deal beyond intersubjectivity when he regained his mother's religion. Binx says at the end that what he believes is not the reader's business, he cuts the reader loose, refuses to be edifying. This is Kierkegaard going back to Socrates, "I want no disciples."

Q: But in the next paragraph he says, "Further: I am a member of my mother's family after all and so naturally shy away from the subject of religion (a peculiar word this in the first place, religion; it is something to be suspicious of)." This means, it seems to me, that Binx definitely objects to being edifying, especially in a religious way.

A: Yes, if you like.

(…)

Q: I wonder why it is necessary to bring the mental sickness of these characters into such a sharp focus? Is it to perplex the world with the old enigma: are these sick people in a normal world or normal people in a sick world? Or is it the interest of the medical doctor? Or both?

A: It is partly therapeutic, medical interest but also goes deeper than that. The view of Pascal and some others who were interested in the human condition was that there is something wrong with mankind. So it is always undecided in my novels. This is the main question of the novels. Here is a hero who is afflicted, shows malaise, dislocation, and he is surrounded by apparently happy and sane people, particularly Dr. More, who lives in Paradise Estates. So who is crazy, the people apparently happy or those radically dislocated characters?

(…)

Q: Although I know you have been frequently asked about the position of the writer in the South, I would like to ask you to summarize your view on this question for the Hungarian reader for whom this talk is primarily intended and for whom your view of the writer in the South will be a novelty.