#even machiavelli suggesting that lucrezia and juan were having an affair and cesare murdering him for it is a tea beyond delicious

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

— Cesare Borgia: The Machiavellian Prince, Carlo Beuf (1942)

#even machiavelli suggesting that lucrezia and juan were having an affair and cesare murdering him for it is a tea beyond delicious#while i personally don't buy into the narrative that cesare killed juan for many reasons. i love indulging them because they are sooo fun#lucrezia giovane (1974) save meee they were the only media who made juan x lucrezia affair happen + giving us jealous murderous cesare </3#and only los borgia (2006) were brave enough to make the cesare/sancha/juan triangle happen#carlo beuf#cesare borgia the machiavellian prince#the borgias#cesare borgia#niccolo machiavelli#machiavelli#borgias#borgia#historical figures#history#literature#italian renaissance#words#the borgia family#tb text post

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

In the 3rd season of Borgia Faith & Fear, Della Rovere tells Lucrezia "of all the Borgias, I think you are the most dangerous", I find it funny bc I don't remember Lucrezia was being especially threatening to DR there. Do you think this phrase could be applied to Lucrezia? In which cases could she (always seen as tragic & passive)have been more "dangerous" or influential than the almighty Rodrigo and the energetic Cesare? Perhaps in things related to diplomacy and behind-the-scenes maneuvering?

Oh, this scene! it was a good one. And no, she wasn’t being especially threatening to DR there, not in an obvious, male way, which tends to be more overt, but she was kinda being it in a female way, which tends to be more covert, and which can be more dangerous at times because you don’t see it coming, and that I believe, was the point of the scene. DR clearly saw the threat in Rodrigo and Cesare, but he never saw it in Lucrezia, until that moment. That was when he realized that behind her mask of beauty, charm and piety, laid an very intelligent and diplomatic woman, who knew how to use her feminine charms to get what she wanted, and that indeed made her more dangerous than her male relatives, who in Fontana’s version, are uncharacteristically unstable, obvious in their plans, and openly and stupidly confrontational with their enemies. In this world, Della Rovere was used to that, but he wasn’t used to the tactics Lucrezia was employing there, so he was definitely like: hmmm, I need to be careful here, more than ever before djsdjdsjdsj. And yes, anon, I do think this phrase could be applied to historical Lucrezia, despite the insistence of Borgian scholars to keep fallaciously reducing her to a tragic, passive figure, who was only a victim of "patriarchy" and "the terrible, ambitious men" in her family, looool. Much like it happens with Cesare, Lucrezia's historical material, her actions, do not support the majority of the claims made about her and the overall presentation of her historical figure, on the contrary, it constantly heavily points towards different conclusions about her character, her life, and most of all: her family dynamics with her beloved father and brothers. I think it must be understood that Lucrezia seems to have had a preference for the incognito way of doing politics, and to not treat it as a lesser form of doing politics, because in truth, it is very wise, also. She was as intelligent, politically cunning, ambitious and pragmatic as her family, and other noblewomen of her times, but she does not seem to have wanted to broadcast that to the world, she doesn't seem to have had any desire to let others perceive her as a political player, perhaps because she was aware it brought more disadvantages than advantages, man or woman, once you were perceived by others as a political threat, it made you an easy target for violence, and it added an extra difficulty in making political moves without being noticed, (and the element of suprise, of secrecy, is one of the key factors of successsful policies or of achieving a certain political goal) Lucrezia witnessed that first hand, with Juan being murdered, Rodrigo and Cesare having various murder attempts to their person over the years they were in power, and with their every move constantly being watched, their words and actions scrutinized by their contemporaries. Lucrezia had no need for that, so the lack of records about her private life (even Gregorovius in the end admits nothing is known about her private life while she was in Rome) and of her political side does look like it was partly like her own doing. A deliberate effort into making herself as unnoticeable as possible where political affairs were concerned, simultaneously always taking great care in her appearance in public, from her dressings, to her hair, to her walk, to her speech. She always presented herself as the beautiful, graceful, fashionable, joyful, and pious daughter of the Pope. This presentation does contain a certain political tactic, or dissimulation to it, much like the one made by Cesare to Machiavelli, or Rodrigo to the Venetian orators and ambassadors, with his seemingly honest talk with them, like they were close friends, when that was far from being the case. And here's the thing: it is quite obvious this presentation worked to her advantage, according to the historical records, most people who met her, especially men, fell for it, (even her biographers to this day do) and they all appear to have never seen it past what she presented to them, in that way, she could,

and did, obtain what she wished from them: eulogies praising her virtues (a good and necessary PR the rest of her family should probably have paid as close attention to as she seems to have done tsc tsc), beautiful love poems, and of course valuable information and people who felt so attached to her person they were willing to help her in her political and romantic intrigues.

This all can be observed in various occasions during her lifetime: The writings of Ariosto and other intellectuals about her, the passionate love poems and letters of Bembo, the documented actions of both the Marquis of Mantua, and Ercole Strozzi concerning her. And we have the very interesting words of one of spies of Isabella d'Este, known as il Prete, whom she sent to Rome with the precise task of him learning every detail about Lucrezia, but when he met with her, he ended up disclosing more about his mistress to her than of actually learning anything significant about her, and in one of his reports to Isabella he says: "She[Lucrezia] is a lady of keen intelligence and perspicacity...” and in another one he writes: “one had to have one’s wits about one when speaking with her..." And as far as influence goes, there is certainly material indicating she did had a strong influence with her father, and it can only be speculated with her brothers, (although I think she did to a certain extent, I think it is undeniable that her contemporaries were aware she was the darling of the family, and to offend her in any way would immediately put them in disfavour with Rodrigo, Cesare and Juan, they spoiled her a lot, and were very protective of her) but it is noted Lucrezia was the constant recipient of petitions to Rodrigo, of various sorts, which implies they saw her as the best intermediary between them and the Pope, in order for them to get their wishes granted. Not Cesare, not Juan. So within the family, her influence can be supported by the evidence, and outside the family the evidence is way more limited, but considering all this, I don't think it would be far-fetched to say that not only it does seem she played a bigger role in the politics than it is usually conceded to her, but that she very well could have been more dangerous, more influential at times than Rodrigo and Cesare, only behind the scenes, as it really does appear to have been her MO. For all of the excellent diplomacy and political skills Rodrigo and Cesare had, they were still men, men at the front stage of power nonetheless, which caused other men to be more guarded in their presence, even if they felt dazzled by Cesare or Rodrigo's strong allure, however, with Lucrezia, I think it was a different story. She had the same mental and political capabilities they had, in fact, I'd argue there is much indicating she learned a lot from them, but all of that came under, was deliberately hidden by her, by the feminine cover, which both made these traits and her being perceived as a threat a lot harder, if not impossible, to detect. Which naturally, as seen above, prompted men, perhaps also women (although Isabella d'Este would not be included in this list jdsjdsj, for I think apart from her personal prejudices against Lucrezia and her family, she also recognized from the get-go the political shrewdness in Lucrezia since she was also a shrewed political woman herself), to lower their guards around her, and speak more freely, and here I believe, Lucrezia had a bigger room to be influential with them, engaging in diplomatic conversations, suggesting ideas about a particular political situation, asking something from them, and that being more well received than it would have been if it had been otherwise proposed or offered by her father and brother, and perhaps even her husbands.

#ask answered#anon ask#lucrezia borgia#house borgia in fiction#house borgia in history#cesare/rodrigo and lucrezia are my favorite trio in history#and they deserve soooooo much more than it is given to them#it's unfortunate#:(#and in some ways lucrezia def. reminds me of livia drusilla tbh#bc she really seemed to know how to work around obstacles and more often than not getting what she wanted#and/or what was in her and her's family advantage#i often see her as the renaissance livia drusilla alas without her octavian djsjdsjs#but as i said for cesare in it being hard to find a livia drusilla so it is to find an octavian#only very few lucky people do

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Were the Borgias Really so Bad?

Alexander Lee attempts to rescue the Borgias from their baleful reputation.

youtube

Renaissance Italy was dominated by rich and powerful families whose reputations have been shaped by the many dark and dastardly deeds they committed. In quattrocento Florence, the Medici bought, bribed, and blackmailed their way to the top; in Rimini, the Malatesta flitted continually between self-destructive megalomania and near psychopathic brutality; and in Milan, the Sforza were every by as infamous for their sexual proclivities as they were for their political ruthlessness. But in this devilish roll-call of nefarious names, none sends such a chill up the spine as that of ‘Borgia’.

It is impossible to imagine a family more heavily tainted by the stains of sin and immorality, and – as even those who have not seen the eponymous television series will know – there is scarcely one of their number who does not seem to be cloaked in an aura of iniquity. The founder of the family’s fortunes, Alfons de Borja (1378-1458) – who reigned as Pope Callixtus III – was decried even by his closest allies as the “scandal of [his] age” for his monstrously corrupt ways. His nephew, Rodrigo (1431-1503) – who he himself elevated to the cardinalate, and who would be elected Pope Alexander VI in 1492 – was reputed to be even worse. Accused of buying the papacy, he would later be besmirched by rumours so severe that the Venetian diplomat Girolamo Priuli felt able to claim he had “given his soul and body to the great demon in Hell”. Indeed, as the papal master of ceremonies, Johann Burchard, was to contend in the middle of Alexander’s reign:

There is no longer any crime or shameful act that does not take place in public in Rome and in the home of the Pontiff. Who could fail to be horrified by the…terrible, monstrous acts of lechery that are committed openly in his home, with no respect for God or man? Rapes and acts of incest are countless…[and]great throngs of courtesans frequent St. Peter’s Palace, pimps, brothels, and whorehouses are to be found everywhere!

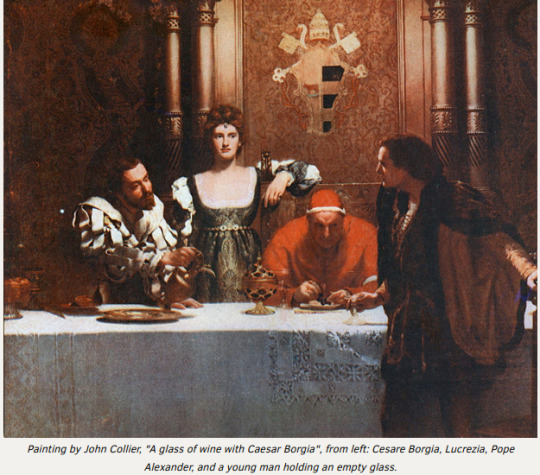

But worse still was the reputation of Alexander’s children, and Burchard’s blithe comment that they were “utterly depraved” barely begins to cover the crimes with which they were associated in the contemporary imagination. Lucrezia (1480-1519) – with whom the pope was reputed to have slept – was cast not only as a whore, but also as a poisoner, a murderer, and a witch. And Cesare (1475/6-1507) – the most handsome, dashing, and despicable Borgia of all – was widely believed to have killed his elder brother Juan in a fit of jealousy, bedded his sister, and embarked on a campaign of slaughter and conquest aimed at carving a kingdom out of the scattered states of Northern Italy.

Confronted with so comprehensively damning a portrait, it is difficult to believe that the Borgias could have been any more dreadful if they had tried. But precisely because the impression conveyed by contemporary accounts is soutterly dreadful, it is equally difficult not to question whether such a terrible reputation was entirely justified. Were the Borgias really all that bad?

As with most things that are supposed to have happened behind the scenes in the shadowy world of Renaissance Rome, certainty is often elusive, and it is a challenging task to separate the evidential wheat from the gossipy chaff when sifting through the documents which have survived. Yet despite this, there is enough to suggest that the Borgias weren’t quite the one-dimensional evil-doers they first appear to have been.

On the one hand, they certainly weren’t the demonic arch-villains they have been painted as. For all of the vividness with which observers such as Burchard, Priuli, Machiavelli, and Guicciardini described the Borgias, it is clear that at least some of the family’s unenviable reputation was entirely undeserved. The charge of incest, for example, seems to be without any solid basis in fact. So too, the suggestion that Lucrezia was a poisoner is grounded more on salacious gossip and the hysterical accusations of a divorced husband than on reliable evidence.

Although thrice married – each time for political reasons – she was, by all accounts, a highly cultured and intelligent figure who was admired and respected by contemporaries such as the poet Pietro Bembo, and who was never seriously associated with any misdeeds. But equally untenable is the claim that Cesare killed his brother. Not only was there little for Cesare to gain from Juan’s death, but it is even arguable that – since Cesare was compelled to set aside his cardinal’s hat to assume Juan’s secular roles - the family’s long-term position was weakened so severely that he could not have been unaware of the risks.

Much more plausible is the suggestion that Juan was killed either in an amorous adventure gone wrong, or at the instigation of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, with whom he had argued, and who was an avowed enemy of the whole family. Even less credible, however, are the piquant accounts of the Borgias’ supposedly raucous parties. The so-called “Banquet of the Chestnuts” – an all-night orgy at Apostolic Palace attended by fifty “honest prostitutes” and involving eye-popping sexual athletics – is, for example, attested only in Burchard’s memoirs, and is not only intrinsically implausible, but was also dismissed as such by many contemporaries.On the other hand, even those crimes of which the Borgias were guilty weren’t anything out of the ordinary. Indeed, when the evidence is interrogated more carefully, it is apparent that the Borgias were entirely typical of the families who were continually vying for the papal throne during the Renaissance.

They were, for example, undoubtedly guilty of both nepotism and simony. Although the sums involved were unquestionably exaggerated by contemporary chroniclers, both Callixtus III and Alexander VI bribed their way to the papacy, and used their power to advance their family as fully as possible. Alexander VI alone elevated not fewer than ten of his relatives to the College of Cardinals, and endowed others with a host of fiefdoms in the Papal States. But precisely because the papacy could so easily be misused for familial aggrandisement and enrichment, these ecclesiastical abuses were all too familiar. Though formally classed as a sin, simony was common. In 1410, for example, Baldassare Cossa borrowed 10,000fl. from Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici to bribe his way to becoming Anti-pope John XXIII, and at the conclave of 1458, Cardinal Guillaume d’Estouteville promised to distribute a vast array of lucrative benefices to anyone who would vote for him, albeit in vain. Nepotism, too, was widespread. In the early fifteenth century, Martin V had secured immense estates for his Colonna relatives in the kingdom of Naples, but within a century, nepotism had become so extreme that even Machiavelli felt obliged to attack Sixtus IV – who had elevated six of his relatives to the Sacred College – for this crime. Later, Julius II (a kinsman of Sixtus IV) acquired the duchy of Urbino for his nephew, Francesco Maria della Rovere; Clement VII made his illegitimate son, Alessandro, the first duke of Florence; and Paul III raised his bastard child, Pier Luigi Farnese, to the duchy of Parma.

Similarly, there is no doubting that Alexander VI was a lusty and sexually adventurous pope. He openly acknowledged fathering a bevy of children by his mistress, Vannozza dei Cattanei, and later enjoyed the legendary affections of Giulia Farnese, renowned as one of the most beautiful women of her day.

But here again, Alexander was merely following the norms of the Renaissance papacy, and it is telling that Pius II had no shame about penning a wild, sexual comedy called Chrysis. Popes and cardinals were almost expected to have mistresses. Julius II, for example, was the father of numerous children, and never bothered to hide the fact, while Cardinal Jean de Jouffroy was notorious for being a devotee of brothels. Homosexual affairs were no less common, and in that he seems to have limited himself to only one gender, Alexander VI almost seems straight-laced.

Sixtus IV was, for instance, reputed to have given the cardinals special permission to commit sodomy during the summer, perhaps to allow him to do so without fear of criticism, while Paul II was rumoured to have died while being sodomised by a page-boy.

Even Cesare’s deserved reputation for savage megalomania is rather less impressive when set in the context of the period. He was, of course, a ferociously ambitious figure who indulged in some pretty low tactics. Having divested himself of his cardinal’s hat, he ripped through the Romagna and Le Marche, building a vast, private fiefdom in the space of just three years. In all this, murder seemed not an occasional necessity, but an integral part of everyday existence. In 1499 alone, he ordered the assassination or execution of the Spanish Constable of the Guard, the soldier-captain Juan Cervillon, and Ferdinando d’Almaida, the cruel-minded bishop of Ceuta, and subsequently added a host of individuals such as Astorre III Manfredi to his list of victims. Later, he even slaughtered three of his own senior commanders at a dinner in Senigallia after (rightly) suspecting them of plotting against him. But from a certain perspective, all of this was only to be expected. It was quite normal for the relatives of Renaissance popes to set their sights on conquest and acquisition.

Although some ‘papal’ families – such as the Colonna – owned huge tracts of land, the majority – such as the Piccolomini and the della Rovere – started out as cash-strapped minor nobles, or – in the Borgias’ case – as landless foreigners, and popes from this latter group naturally encouraged their kinsmen to seize enough territory to put them on a par with the greatest noble houses in Italy. This meant war. And in an age in which war was the preserve of mercenaries, war meant cruelty on a grand scale. The wild, bisexual Pier Luigi Farnese, for example, was infamous for his brutality, and not only pillaged at will, but also made a habit of hunting down those men who resisted his advances. So too, Francesco Maria della Rovere, was nothing more than a soldier for hire, who ordered his troops to slaughter Cardinal Francesco Alidosi after his own failure to capture Bologna. Indeed, if anything, Cesare was unusual only in his tactical brilliance and in his comparative self-restraint.

It seems clear that the Borgias’ rather unfortunate reputation was undeserved. While some of the accusations levelled at them were simply untrue, even those crimes which they did commit were typical of the period, and paled by comparison to those of other ‘papal’ families.

Yet this leaves us with a problem. If the Borgias weren’t as bad as they may seem, why was their name so heavily tarnished? Why did observers turn on them quite so comprehensively, and what was the reason for so dramatic a smear campaign?

Although in later years, the steady worsening of the Borgias’ reputation was intimately linked to the shifting currents of Reformation and Counter-Reformation thought, there are perhaps three reasons why contemporary observers were prepared to attack them quite so viciously.

The first is simply that they were Spaniards, and as such, were yoked to shifting perceptions of Spanish influence in the Italian peninsula. Attitudes were, of course, often positive, but as a result of the involvement of Spain and the Aragonese kingdom of Naples in the affairs of Northern Italy during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, there gradually emerged a ‘Black Legend’, a virulent form of anti-Spanish propaganda which identified all things Spanish with oppression, brutality, and cruelty. The fact that the Borgias hailed from Valencia, and that Alexander VI had helped to involve the Spanish more closely in Italian affairs meant that the family was almost inevitably tarred with the same brush.

The second reason is that they were outsiders. In spite of the universality of the Church’s message, the Renaissance papacy was perceived to be an Italianinstitution, simply by virtue of the fact that the control of the Papal States gave a pontiff and his family colossal power in the Italian peninsula itself, both in terms of direct political influence, and in terms of familial aggrandizement. Whichever way you looked at it, the papacy was dominated by Italians, directed in the interest of Italian states, and misused for the benefit of Italians. The Borgias were an anomaly. It was not merely that they were not Italian (there would be only one other non-Italian pope between the end of the Great Schism in 1417 and the Sack of Rome in 1527); rather, it was that Callixtus III and Alexander VI sought to use the papacy to enrich their family at the expense of Italians. They despoiled other (Italian) families of their land and titles; they invoked the help of foreign powers; and they generally disrupted the delicate balance of power in Italy. As a consequence, it was almost natural that Italian commentators and historians – many of whom had experienced the rapaciousness of successive pontiffs – were willing to depict the Borgias inaccurately as especially corrupt and vile individuals.

The third – and most important – reason is, however, that the Borgias simply weren’t all that successful. Although it was not unusual for families to base their success entirely on papal favour, most were canny enough to limit their ambitions, to consolidate their gains gradually and to graft themselves into other more established families. In other words, they started small, played the long game and tried not to ruffle too many feathers. And, by and large, this was a technique that worked. The Piccolomini, the della Rovere, and the Farnese families all climbed the ladder slowly and effectively, and – in time – became dominant players in the game of Italian politics. This fact alone prevented anyone from taking too strong a dislike to them. You just had to get along with them. But the Borgias were different. They were too hasty, too reliant on papal authority and foreign favour, and too unwilling to respect existing patters of landed power. They were building on sand. No sooner had Alexander VI died than Cesare’s proto-kingdom imploded and he himself was betrayed by Julius II. There was nothing left, and there was no-one to turn to for help. Forced to return to Spain, Cesare – and the Borgias – had failed. And in failure, even their former friends had no hesitation in decrying them as scoundrels. Without lasting power or influence, there was nothing either to hold back the criticism or to restrain the exaggerations.

If the Borgias weren’t as bad as they have often seemed, therefore, the background to their unfortunate and ill-deserved reputation leaves us with a rather more interesting and engaging history. On the one hand, it is a tale of an obscure Spanish family determined to seek its fortune in a foreign land, set on beating the Italians at their own game, and perhaps willing to engage a little too freely in some of the more sensuous pleasures of the age. But on the other hand, it is a story of inglorious failure, dramatic defeat, and the ignominious assaults of enemies who hated outsiders – especially Spaniards – more than anything else. It is not a tale we might expect of the Borgias, but it is nevertheless a tale that is all too reflective of the amazing double-standards of the Renaissance, and is perhaps all the richer for it. Source

0 notes