#even in other decadent imperial societies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I hate that fuckin post that’s like “actually it’s not useful to say westerners enjoy a level of luxury never before imagined in human history because um. Kings didn’t have to worry about the rent” and like. Well actually I don’t know if you know this but historical rulers sort of did have a rent to worry about called the national treasury and oftentimes they’d just be straight up killed if that shit was empty but also like. I dunno like you live in a world where at literally any moment you can choose to be entertained by nearly any piece of media or culture we know of, you can eat literally any kind of food you’ve ever wanted year round with no interruptions, and also for the first time in human history getting a boo-boo isn’t just a guaranteed death sentence. Like yeah you may have to pay for these things but these are still luxuries. They are still offered to you. You think fuckin Richard the Lionheart could hop in a car, drive 15 minutes, and eat some Chinese food? You live in the most luxury-filled, convenience focused society in human history you need to start being cognizant of that.

#like do you know how offended people would get if I told them something like Starbucks would be un fathomable#hey side note why did autocorrect fuck up unfathomable’s formatting like that#anyways unfathomable to literally any human in history#but it is! it is unimaginable#that level of constant continuous access to what had been a luxury good#there’s not an equivalent#even in other decadent imperial societies#they didn’t have the access#the convenience#the sheer glut of options or the access to technology that we do#I’m not trying to guilt people because whatever but like. you should be aware.

579 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where I’m at, personally, is that I think voting when you have the franchise is a civic responsibility.

If you’re from the USA and currently possess a vote, you do in fact have a duty to use it in the way that will do the most good to the most people. The weight of imperialism does not lift that burden, it multiplies it. You are determining how much funding UN famine relief may get and whether distant countries will be invaded and you cannot shrink from that. No amount of whinging about your red state (states flip all the time—Virginia was ruby red a few decades ago!) or your misplaced guilt can change that. Everyone from the dawn of time has lived with hands soaked in blood, being part of a society means being complicit in horror, you can become paralyzed by that or you can start to work to save people.

(If a single person is protected by a Harris presidency who’d die under Trump then you actually do have a moral obligation to help them. Failing in that task is, in my opinion, selfishness. Sometimes sympathetic selfishness: people who have lost family due to the incompetence of the best option have the right to shrink back from necessary choices. Humans grieve. That just means everyone further out in the circles of tragedy needs to develop some risk assessment skills and vote on their behalf.)

If you’re in Britain or Brasil or the EU or Georgia or Aotearoa the same holds true. The global community remains a community in which every country impacts the other, no nation lacks some dispossessed minority which needs to be protected. Voting is always important and you never get to slack off. Even if your vote is diluted or subverted you have to try. There is no winning the task of creating a better world, you’re going to keep doing it for the rest of your life.

I believe all this is true and I also believe that Tumblr is the worst possible environment to convince anyone of their truth. It’s probably not possible to harangue anyone into taking moral action. The disappointment of a stranger rarely motivates anyone! But one does have to speak up periodically, so here’s my general plea: Vote. It’s quite literally the bare minimum.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mand'alor the Pretender, Mand'alor the Resurgent: Boba Fett as the Leader of the Mandalorians in the Expanded Universe

Hello everyone! It's Syn with yet another Expanded Universe deep-dive, this time into the reign of Boba Fett as Mand'alor as portrayed in Boba Fett: A Practical Man and throughout the Legacy of the Force series of novels. Fett was indeed made Mand'alor some decades after the events of the Original Trilogy and this post will examine how he became ruler, his actions as leader, and how his reign connects with Mandalorian mythology regarding the relationship between Mandalore the planet and Mand'alor the ruler. I hope you enjoy!

Heir of the True Mandalorians

To understand how Boba Fett became Mand'alor, it's important to first understand his family background. Indeed, Boba was not the first Fett to be named Mand'alor; his father, Jango, also held the title during the tumultuous Mandalorian Civil War. Specifically, Jango served as the Mand'alor of the True Mandalorians, or Haat Mando'ade, a Mandalorian faction established by reformer Jaster Mereel that emphasized honorable conduct and strong community bonds. They were opposed in the civil war by the Death Watch, or Kyr'tsad, a Mandalorian splinter group that espoused ideals of Mandalorian supremacy and rule by brutality. The True Mandalorians would later be massacred by the Jedi in the Battle of Galidraan, and Jango, the sole survivor, would largely withdraw from Mandalorian society and quietly abdicate his claim as Mand'alor.

Despite their relatively short span of existence in Mandalorian history, the True Mandalorians had an outsized effect on Mandalorian cultural identity, with many Mandalorians adopting their tenets and valorizing their struggle against both Death Watch and the Jedi. Furthermore, as Mandalorian society became more suppressed and scattered following the Imperial occupation of Mandalore during the Galactic Civil War, some looked to the history of the True Mandalorians as a source of national pride and a symbol of renewed Mandalorian unity and prestige.

One such believer in the True Mandalorian cause was Fenn Shysa, who served as Mand'alor during and after the Imperial occupation of Mandalore. Widely adored for his charm and affability, Shysa nonetheless was determined to see the true heir of the Haat Mando'ade take the throne: none other than Boba Fett. Despite Boba's status as a Mandalorian being contested by many clans due to what was perceived as his dishonorable behavior, failure to uphold the Resol'nare, and the fact that he'd never completed his verd'goten due to his father's premature death, Shysa believed that Boba could serve as a powerful symbol for both the scattered Mandalorian people and the rest of the galaxy as both the heir to the True Mandalorian cause and a notorious warrior the galaxy-over.

Unfortunately for Shysa, Boba had no interest in taking up the mantle of Mand'alor. In light of Boba's unwillingness, Shysa pursued other leads for potential heirs of the True Mandalorian title, including Jango's sister Arla (who unfortunately had been rendered mentally unfit after her prolonged and torturous captivity under the Death Watch) and even one of Jango's clones, Spar, whom Shysa may or may not have presented to the galaxy as Boba Fett himself.

Yet, Shysa would eventually get his wish, though at a very high price. With a bounty placed on his head by Boba's former tutor, the Kaminoan Taun We, Shysa would come face-to-face with Boba himself on the planet Shogun. Despite being hired to kill Shysa, Boba would, due to events that are never fully explained, end up on the same side as him against an attack of Sevvet mercenaries. With the two of them overpowered, Shysa sacrificed his life to protect Boba and ordered Boba to kill him and take his place as Mand'alor. Indebted to Shysa for saving his life and unwilling to let him fall into the hands of the notoriously sadistic Sevvets, Boba would honor both of Shysa's requests.

Though it cost him his life, Shysa would see his ambition through in the end: the heir of Jango Fett now held the title of Mand'alor.

The Pretender Years: Mandalorian Deception During of the Yuuzhan Vong War

Boba's first test as Mand'alor would come fairly soon after he had taken power: an invasion by an extragalactic army known as the Yuuzhan Vong. These invaders intended to conquer the galaxy and either destroy, convert, or enslave all sentient life within it—but to do this effectively, they needed help. Namely, they needed denizens of their target galaxy to help them gather intelligence and do sensitive infiltration work that they themselves would be unable to carry out. For this, they approached a peoples whom they had found to be notorious for their mercenary natures, led by a man equally notorious for working with the worst of the worst: the Mandalorians and their Mand'alor Boba Fett.

While meeting with Boba and his second-in-command, Goran Beviin, aboard one of their ships, the Yuuzhan Vong commander Nom Anor presented their terms: work for the Yuuzhan Vong or be exterminated. Anor also made sure to present Boba and Beviin with two prisoners they had already taken, a Human and a Twi'lek male, outfitted with gruesome, surgically-implanted torture devices to demonstrate what would be in store for their people should they resist.

Deciding then and there that he despised the Yuuzhan Vong and that he'd do whatever was necessary to destroy them, Boba feigned indifference and, much to Anor's surprise, demanded a higher price: amnesty to the entire Mandalore sector, both during and after the invasion. Finding himself unable to sway Boba despite his repeated threats, Anor eventually agreed to the deal, buying Boba and Beviin much-needed time to prepare the Mandalorian people for their great deception.

The Mandalorian people would pretend to be traitors to their galaxy, serving the Yuuzhan Vong as spies and mercenaries—and all the while, they would sabotage the Yuuzhan Vong and funnel intelligence regarding their movements and tactics to New Republic command.

Under Boba, the Mandalorians would keep up this facade for much of the war, their intelligence proving instrumental in combating the invaders even while much of the galaxy believed them to be conspirators with the Yuuzhan Vong. Only towards the end of the war did their deception become known to the Vong, who responded with vicious, razed-earth attacks on the planet of Mandalore, not only killing its people but also carpet-bombing much of the planet's surface and poisoning the soil in an effort to render the planet uninhabitable.

Despite the heavy toll taken by the Mandalorians during the war, with their help, the galaxy was able to turn back the Yuuzhan Vong invasion and emerge victorious—though the challenges facing Mandalore and its people were still far from over.

Mandalore Resurgent: Post-War Aftermath and Policies

Following the war against the Yuuzhan Vong, Mandalore would find itself in a precarious position. With a third of its population destroyed, its industrial infrastructure in shambles, and much of its arable land poisoned, it was unclear whether the planet could even support its surviving clans. In addition, the Mandalorian deception that had proved so instrumental in turning the tide against the Yuuzhan Vong had worked a little too well; most of the galaxy still viewed the Mandalorians as traitors who had only turned against their Yuuzhan Vong handlers at the last minute. As a result, Mandalore was offered no aid whatsoever from the Galactic Alliance (formerly the New Republic) following the war in spite of the planet's dire straits.

Faced with these circumstances, Mand'alor Boba Fett pursued policies focusing on the internal restoration of Mandalore, including:

An immediate order for two million Mandalorians living in diaspora to return to Mandalore to help rebuild the planet. All returning Mandalorians were eligible receive an allotment of land, provided they agreed to restore it. Boba knew this was possible because he had seen Beviin, a farmer by trade, restore the land on his own farm.

Mandalore's official neutrality in the ongoing civil war between the Galactic Alliance and the Corellian Confederation. Individual Mandalorians were free to offer their mercenary services to whichever side they wished, but it was to be understood that Mandalore itself had no official involvement in the dispute.

The increased importation of food to Mandalore to feed the population until such a time that the planet's farming and infrastructure could sustain itself once more. Both Fett himself and the chief of MandalMotors would donate heavily to pay for these imports.

In addition to these policies, Mandalore would also benefit from a lucky break discovered more than a decade after the end of the Yuuzhan Vong war: a massive motherlode of beskar unearthed by the Yuuzhan Vong's extensive bombing of the planet. This discovery was extremely significant following the Imperial occupation of Mandalore, as it was believed that the Empire had completely strip-mined the planet bare of its beskar deposits. With both sides of the galaxy's newest civil war scrambling for weapons and armor, this newly discovered beskar would prove a massive economic windfall for the struggling Mandalorians, and also serve as the catalyst for MandalMotors creating the first-ever beskar-plated starfighter, the Bes'uliik.

Mirrored Destinies: Connection to Mandalorian Mythology

As an ending note to this lore post, I'd like to share a piece of Mandalorian mythology and how we see it exemplified in Boba's rule as Mand'alor. According to this belief, the fate of Mand'alor the leader and Mandalore the planet are inextricably tied; the two are synonymous to the point where, if something happens to one, whether for good or ill, one expects to see it reflected in the other. And this is absolutely the case in Boba's story.

Consider: when Boba first becomes Mand'alor, he finds himself leading a planet still recovering from Imperial rule. It is largely believed to have been robbed of its defining resource, its beskar, and thus, its soul has been stolen. Similarly, Fett himself is perceived to have "sold his soul" to the Imperials. He is the heir of the Haat Mando'ade, someone who is meant to embody the Mandalorian ideal as expressed by his grandfather Jaster Mereel, but that hope for him appears to have been in vain. He is isolated from the Mandalorians and has spent much of the past few decades at the beck and call of their enemies. He, like Mandalore, has enriched the Empire at the expense of his people.

Then, the Yuuzhan Vong War happens. Mandalore the planet is poisoned and no longer self-sustaining. Coincidentally, soon after the end of the war, Fett finds out that he is dying of a terminal genetic illness due to his cloned DNA. Both he and Mandalore are dying together.

But he doesn't go down without a fight. He learns to rely on others, such as Beviin, Mirta, and the other Mandalorians. With them, he is able to find a cure and begin the process of recovery. And, just like its Mand'alor, Mandalore is able to come back from the brink by the same means. It needs others to care for it, to restore it. Only then can it become a viable homeland once more.

Finally, after all that misfortune and suffering—because of the misfortune and suffering—both the planet and the man are revealed to not be so bereft and without soul as originally thought. In the crater of Yuuzhan Vong desolation, a new motherlode of beskar is found. In the midst of illness, war, and grief, something like a true Mandalorian is found—someone who cares for his people, his clan, and his planet. Both Mand'alor and Mandalore thus go through an arc of loss, desolation, interdependence with others, and finally, resurgence and rebirth. In this way, Boba Fett embodies the myth of the inextricable connection between Mandalore the planet and Mand'alor the man.

#boba fett#boba fett meta#star wars#star wars meta#mandalorians#mandalorian meta#sweu#star wars expanded universe#REJOICE!! OVERLY-LONG LORE POST BE UPON THEE!!#this was originally just gonna be the last section about how boba and the planet mandalore have similar arcs but#i could not stop myself from adding more context

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Confession time - I find Miles Wei’s character more interesting that Li Xian’s.

It’s honestly The Double again for me - a female centric narrative about a driven woman with a terrible weak ex and a powerful new dude - and I find myself much more interested in the bad dude than the good one.

OK, before people come for my head, this doesn’t mean I find Peony husband a better person than the Envoy or that I ship him with FL (no thank you!), I just find him more interesting as a character for the same reason that I found Shen Yurong more interesting in The Double (tho in The Double, it was exacerbated by the fact that SYR and Princess Wanning actors gave the best performances in the drama - the mains were great but those two were another level. Here I don’t think Husband is giving a better performance than Envoy.)

You never truly know how Husband would act and which way he’d jump. He’s not the noble main character bound by the narrative restrictions (and censorship restrictions) within a certain path. And that is what makes him interesting to me - the complexity but also the uncertainty. I mean both actual MLs of The Double and Peony have a bit of an edge - Duke Su is dramatic and ruthless and starts out using FL and Envoy is dramatic, standoffish from FL and seemingly corrupt. But it’s a cdrama in this era, not a decade plus ago, we all know every minute they are actually good guys - no, Envoy is not actually corrupt and Duke Su is not actually murder happy - the former is saving the bribes for the people of treasury or w/e, Duke Su only kills death penalty people and both are super super duper loyal to the crown and of course would save the FL if she really needed it.

That makes them great husband material but it removes a lot of the tension I find interesting. No, a character does not need to be dark and/or unhinged for me to find them interesting - I loved 17 in LYF and am loving XXC in The Blossoming Love and those two are utter Boy Scouts - but it is hard to do in such a way they grab me.

Meanwhile secondaries are out there running free of confines of the moral messages which gives them an edge.

In the olden days, you could have MLs which were like this (I am thinking of Glamorous Imperial Concubine - the deliciousness of it was that Kevin Yan started ready willing and able to harm FL for his goals, not to mention all the “proper” historicals - think of Three Kingdoms or Advisors’ Alliance - those were not romantic heroes in traditional sense or a more recent example of Goodbye My Princess or Siege in Fog - except their inability to let FL go it was anything goes for those MLs) but for obvious reasons, this doesn’t happen much any more - the closest we’ve come recently is Kunning and Blossom and I adored both - there a lot of tension was that even after we realized MLs would die for FL, you often had no idea how they’d jump for other reasons and it gave us tension.

(Interesting side note is something like Eternal Brotherhood where even until the last episode, in terms of romance, I could not tell how Xiu would react to Ning - he was a very good person but the tension in the narrative came from his immense damage - every scene between them crackled with whether his feelings would win or his issues - it was constantly his issues but in every scene I kept going…but what if? That’s good acting and writing! But then there was the other tension because what Xiu was dedicated to was brotherhood and his platonic ideal of what a just society should be - which put him on a collision course with the wishes of his heart, and his friends and even the ruler - it gave uncertainty also. That’s a hard balancing act.)

Anyway this is a ramble so I will finish this failed attempt at an essay by saying - if cdrama rules allowed mains more edge and uncertainty, I’d probably be (even) more interested but as is, much as I love the mains, I often end up more drawn to secondaries in terms of interest.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think autistic primarchs would present very differently than in a baseline human. Its so much easier to cover up or explain away.

Like if Mortarion goes semi- verbal, he still sounds normal. But very stilted for a primarch. Its different from when I can only maybe say three words at a time. Usually I can only go "I don't know" or "no", or "go away". For him it's still full length sentences, like "I think I just need to be alone now". That can easily be explained to be exhaustion. But in reality he can't vocalize anything more complex right now.

Guilliman has be scripting since a child but no one notices. He just has over 100 scripts memorized for any occasion. Any question or change in the conversation. He already has a script lined up. He's capable of memorizing it. Conversations happen so naturally, you can't even tell the difference.

Even the way they stim can be so different to a baseline. Probably in ways a baseline can't comprehend. Traits like increased pattern recognition are standard in a primarch. All primarchs are far more "higher functioning" than any baseline.

Being behind their brothers developmentally by a few weeks is nothing compared to a baseline. What's walking at two months when most humans are closer to a year old when they start. Sure the other primarchs were walking much sooner. Some right out of the pod. But they often reached adulthood far sooner than any human. What constitutes a development delay to a primarch. If an apothecary can't tell what's a high blood pressure level in Guilliman. How can you tell?

Exhaustion that so many autistic face is so off from a baseline. They need less sleep. They can go through periods without rest for far longer. I think in cases like Mortarion, he can just push through an autistic burnout. Sure he's a bit more irritable, among other things. But hey, the point of a shutdown won't hit him till a few decades later. So therefore he must have high energy levels then even his brothers. Despite the toll on his mental health. Plus their recovery times are far shorter. Guilliman needs just a few days to feel normal after a year long campaign after all. Doesn't matter how he was acting prior. Any strange behavior can be hand waved away.

Mental conditioning can be used to suppress sensory overload. No point in having your super solider curl up screaming because he has super hearing. And you threw him into an active warzone. Lets make sure you can't process that information in way that would harm you. (Plus I think as a rule primarchs have a tendency to be more sensory seeking than sensory avoidant.)

Hell even their positions in the imperial society could make it easier to mask. If Perturabo wants something done in a certain way, you are going to do it that way. You're just some 25 year old iron warrior or serf that needs to follow command. Plus you don't know best compared to a primarch.

Of course they mask in typical ways. Mortarion hasn't rocked when upset since he was young. Because Nacrae told him that he should avoid such weakling behavior. Or still show more obvious traits like Dorn's flatter speaking style. (IDK how true this is but everyone says this and I'm not too familiar with Dorn to say otherwise.)

Also I like to imagine that the Emperor intentionally placed Autism into some of his designer babies. Thinking he could "avoid all the negatives but only gain those traits that would benefit them greatly." Only for his patience to slowly be drained. Like Perturabo having a meltdown while Dorn is trying to get the two of them to work together. But he's lost the ability to mask what little he does. And is just going, "We are to conclude this activity in an hour. I have to calibrate the ships sensors in an hour and half. You have already wasted 10 minutes. We must refocus so we can conclude in an hour..."

The problem start when understanding what's going on under the surface. Or when you start comparing them to their brothers. But hey you're below understanding what a primarch is thinking. And all the primarchs are little off. They're demigods. What makes these one's so different. Doesn't help they themselves won't consider it themselves. Or even be insulted by the implication. I'm not an invalid. Don't be ridiculous.

(I used Perturabo, Dorn, and Guilliman here because they're the common ones head cannoned as autistic. I went with Mortarion as well because I decided to just go with it. I know him the best. Plus this is all just headcannon. Just to be clear. Reasoning being his kids tend to present with a flat personality anyways. Also heard Mortarion was always behind his brothers, so developmental delays?? Idk yet where they got that in lore yet. Trying to get through all the books is a lot. Plus his other strange behaviors. But it could just be poor socialization as a child mixed with mental illness. Could also just be all three too. But more than these four could be autistic is my point. Sorry if this post was rambling or unclear. Or if anyone has done this before. I just wanted to get my thoughts out on the subject.)

#roboute guilliman#rogal dorn#perturabo#mortarion#primarch#horus heresy#warhammer 40k#slight ableism

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why The Tau Were Never 'Too Good' For 40k

The Tau were added midway through Warhammer 40,000's 3rd edition, though according to some records the idea had been floating around since Laserburn. In the twenty years since their introduction to the 41st millennium, the Tau have remained one of the most consistently reviled and hated aspect of 40k lore, with all complaints around them boiling down to one core issue: they're too good for 40k. By that, people mean that they are too morally good to fit within the grimdark narrative of the 41st millennium. This has always been the primary complaint levied at them, since they were first introduced in 2001. And GW has seemingly agreed with them, and spent the last 20 years trying to inject grimdarkness into the Tau Empire.

The first attempt to grimdarkify the Tau came very early on, with the Tau campaign in Dawn of War: Dark Crusade

It's explained how in the decade following Tau victory on Kronus the remaining human population was subjugated, oppressed, forced to give up their culture, and eventually simply sterilized and allowed to die off naturally to create a Tau and Kroot ethnostate on Kronus. It explains this over images of prisoners of war being fed to Krootox in prison camps and humans huddling together in slums.

This is obviously a departure from the image of the Tau as it was established in Codex: Tau (3rd Edition), as that codex makes explicit mention of the Tau trading and making alliances with frontier human colonies. This is also a departure from... common sense. Why exactly would the Tau accept Kroot, Vespid, Nicassar, Demiurg, Tarellians and many others into their ranks but then arbitrarily draw the line at humans?

This would become a pattern that I like to call "The Grimderp Tau Cycle." It's not exactly a stretch to say that the Tau are easily the most morally good society in the 41st millennium. Their tolerance toward other species alone makes them head and shoulders above almost any other species in the galaxy. So to remind people that there are no good guys in the 41st millennium and that this is a very serious and grimdark setting that you need to take seriously because there are no good guys or whatever, GW will occasionally have the Tau commit a completely out of character, random, and nonsensical atrocity. This was also seen at the end of In Harmony Restored, the short story that came out alongside 8th edition's Psychic Awakening: The Greater Good.

For context, In Harmony Restored is a short story about a group of Gue'vesa soldiers (human auxiliary troops fighting in the Tau military) performing a desperate defensive rearguard action to halt an Imperial advance long enough for Tau reinforcements to come and smash the delayed invasion force. The Gue'vesa are able to do this, though at great sacrifice to themselves, and then when the reinforcing army does arrive and makes quick work of the Imperial army they then continue on to butcher the Gue'vesa soldiers who performed this valiant holding action for... Seemingly no reason? Assuming the Tau forces thought they were more Astra Militarum soldiers, the Gue'vesa step out of cover pleading for mercy, only to be gunned down. With one of the Gue'vesa at the end noting that the language one of the Battlesuit pilots is using is very reminiscent of the way the Imperium talks about those they've labeled undesirables.

The message here is clear: these humans betrayed the Imperium in order to escape from the Imperium's genocidal regime... Only to end up in the equally merciless clutches of an equally ruthless oppressor. But, from a lore standpoint, that defeats the entire purpose of the Tau. It makes them wholly indistinct and, frankly, boring. But that doesn't even scratch the surface of how stupid this is, because it has clearly been stated in the past that the Tau do not hold bigotries toward client species on the basis of their faiths. And that makes sense.

Not only does this contradict previous lore, not only does it render the Tau a boring palette swapped version of the Imperium, it also just defies practical sense. If you're a race like the Tau, who expand primarily through ingratiating yourself with other races and convincing them to join your collective, you'd naturally want as few barriers between potential client races and joining as possible. No human colony is going to voluntarily join the Greater Good if the Tau's version of the Greater Good happens to require that the human population of that planet lose all sense of their heritage and culture through forced reeducation and the abandonment of their faith, and in the long term for that human population to slowly go extinct through gradual forced sterilization and confinement to ghettos and slums.

It's deeply stupid, lazy writing on the part of GW to repair the image of the Tau in the eyes of a fandom who accused the faction of being "too good." Except, uhm, here's the thing: the Tau were never too good to begin with. Lets rewind back to 3rd Edition's Tau Codex, our first introduction to the Tau in the 40k universe. From the very beginning it was very clear that the Utopian idealism of the Tau Empire held beneath the surface a significantly more sinister and malevolent nature, and it all roots from the mysterious and enigmatic fifth caste of Tau Society: the Ethereals.

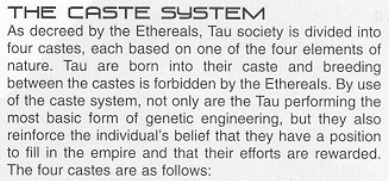

In 3rd Edition, the Ethereals are spoken of more like mythological beings than the slightly mundane way they exist in modern 40k. All we know about them out of this book is that they are the autocratic leaders of the Tau Empire who inspire radical devotion among the Tau, though are rarely seen or heard from. They reorganized Tau society with pursuit of the Greater Good in mind first. But the specifics of what that means matters a lot. Tau are born into a caste that roughly determines, from birth, what role in society that person will fulfill. Those born into a caste are not allowed to have children with members of other castes, are not allowed to take up any job or position that contradicts the societal purpose of their caste, and generally lack self-determination in regards to things like career choice.

so, bam, the setup for Tau as a flawed and morally ambiguous faction are already present. They're a faction who fight for a better future, for a galaxy where all can exist in harmony with one another, so long as that harmony is kosher by the standards of the Ethereal caste. In that sense they're somewhat similar to the Dominion from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. A multispecies interstellar collective who seek to create a galaxy harmoniously unified... in service to the Founders. Just taken from this vision of the Tau Empire, they're already an autocratic dictatorship who fight in the name of an ideology that declares itself to be for the greater good of all who ascribe to it while also relying on the assumption that the tyrannical power of the Ethereals must inherently be for the Greater Good. I reject the idea that the Tau were ever "too good" for 40k. Rather that they were written with a realistic level of nuance, with an understanding that dictatorships are built upon cognitive dissonance, not on perfectly consistent virtues.

TL;DR THEY'RE NOT FUCKING COMMUNISTS, THEY LITERALLY HAVE A CASTE SYSTEM, WHAT THE FUCK ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT?!

#warhammer40k#warhammer#warhammer 40k#t'au empire#t'au#fire warrior#in this essay i will#wargaming#warhammer lore

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

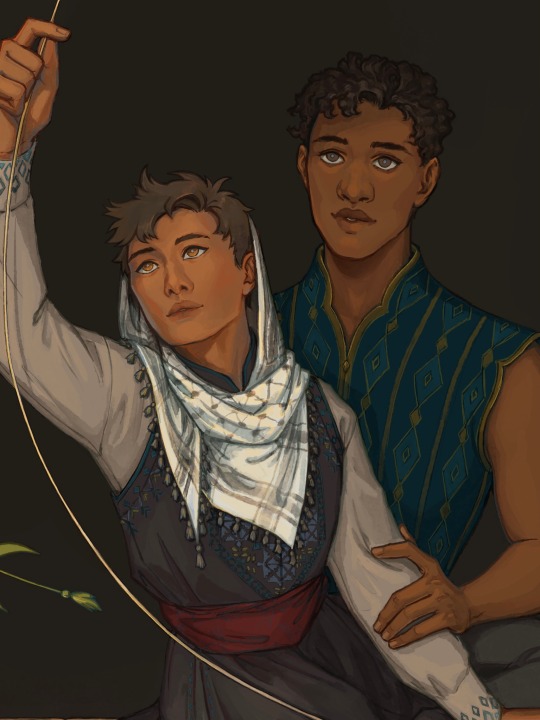

[image ID] Iris, a brown-skinned young man, perches on a windowsill, flying a kite with a long green tail with stylized pennants resembling the Palestinian olive-leaf motif. A black and white kufiya is wrapped loosely around his shoulders, and his black tunic is adorned with tatreez. Crow, a darker-skinned brown man in a dark teal sleeveless shirt, stands behind Iris with his hand resting gently on Iris’s arm. [end ID]

Ceasefire now. End the occupation. Free Palestine.

Context under the cut:

These are my characters Iris (with the kite) and Crow (behind him). I started writing about them a few years ago, and their story takes place in the same world as Fox and Hemlock’s. Stars in the Dark is about being diaspora in a multicultural society, how a gilded cage is still a cage and slavery remains slavery even if it is not named such, and about the weight of a ruler’s legacy.

Iris and Crow’s story takes place a few decades prior, while Mahjuren is not a kingdom but an empire.

This time, the focus is on Iris, one of the last surviving members of an indigenous nomadic minority within Mahjuren. His clan was massacred when he was a child, and his identity as a member of that clan was erased by assigning him a new surname that roughly translates to “of nothing and nowhere.” Other clans are under constant threat from imperial raids that gleefully commit similar massacres with total impunity.

As Iris grows up, every aspect of his life is rigidly dictated by his “savior” who took him in after the massacre. Who he meets, what he learns, where he goes, his meals, his hobbies, and even his relationships are subjected to scrutiny and control.

One of the major events in the story is when Iris is assigned to travel to a certain city for the first time, a trip that is typically given as a reward to novices for becoming journeymen and one that Iris was originally denied. The day he and Crow arrive happens to be the Festival of Kites, and the scene in which Iris plays with a stolen kite is the first moment when Iris is permitted unfettered, childlike joy.

~~

If you read all that, you’ll notice some striking similarities to Palestinian history. None of this was intentional—my original inspiration was North Asian and North American indigenous peoples. Before the genocide in Gaza, I thought maybe my writing of Iris’s childhood was a bit unbelievable, acceptable for a fantasy protagonist but not entirely realistic. I don’t think that anymore. In the past hundred days, we’ve witnessed families wiped out, children kidnapped by colonizers, zionist soldiers laughing as they attempt to destroy an entire society.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why the new fluff in 40k undermines the setting: part 2, what is, and why it is bad

Continuing from the previous post, where we've established the basic themes of the setting and explored how the Imperium exemplifies them, this one deals with the setting's developments over the last two decades consistently undermining said themes.

One great issue are of course the Tau, who use the AI (and it's never corrupted by the taint of Chaos), develop and easily produce new tech, and enjoy effortless interstellar logistics (handwaved away as being "slower" than the Imperium's warp jumps, but that supposed slowness is not causing them any trouble whatsoever).

An example of the Tau, human collaborationists, and AI interacting in the works of superfeyn

That's bad enough on its own, so 40k fluff over the years has made numerous attempts to somehow balance the obvious superiority of their society. Xenology made the furthest strides, in establishing that the Ethereals exert mind control over the rest of the castes using the hormones they secrete, turning the utopia into a dystopia effortlessly. The Tau DoW ending claimed that the Tau sterilised the human populations they conquered. Both sources, of course, aren't canon. Black Library is arguably isn't canon, either, but I've tales retold from it of the Tau not just using human collaborationist units, but, say, recultivating the Imperial hive worlds. And that majorly undermines the core themes of the setting: if human populations can't exist in the Imperium without the constant threat of errant psykers opening a doorway to the Warp for a daemonic incursion to pour through, why can they under the Tau, who are warp-insensitive and thus have no way either to discover the threat or counter it? The same goes for the hives: the Imperium has to milk its worlds for all they're worth to counter the multitude threats from all directions, why don't the Tau? Why are the rules of the setting different for the Tau and the Imperium?

The two other major releases haven't brought quite the same big problems to the setting as the Tau. The Newcrons have simply moved them to become one more civilisation competing with the Imperium on peer terms, except with superiour technology. Similarly, the release of the Adeptus Mechanicus as a separate army hasn't changed much, except for undermining the setting a bit by turning its themes to eleven, a certain distance past verisimilitude. The Skitarii have their legs below the knee cut off and replaced by cybernetic implants, to symbolically reference the cohorts of Mars wearing their legs raw (recall that humans the Imperium has in abundance, yet technology is rare and hard to replicate), and have their eyelids cut off for teh evilz lul. Oh, and of course, the Mechanicus have a perpetual motion machine.

But these all pale compared to the recent (well, two years ago now) release of the Leagues of Votann, formerly known simply as the Squats. You see, the Squats are an offshoot of Humanity, except they still have fully functional STCs (the Holy Grail of the Adeptus Mechanicus that will supposedly reverse the Humanity's technological degradation), they have fully functional superhuman AIs undisturbed by the Iron Men rebellion (and, same as the Tau, somehow not susceptible to daemonic possession), they innovate and easily produce their products, they have 100% reliable means of interstellar FTL travel and communication, and unlike the Tau, they can even harness the powers of the Warp for their combat Psykers, except it's all perfectly safe and doesn't run the risk of daemonic incursion. Plus they can mass-produce genetically optimised clones, except they're not locked into what they're optimised for and instead are free to choose their job (again, unlike the caste system of the Tau).

And by this moment, one has to wonder: how the hell can the Imperium even exist with peer competitors like that? The Leagues of Votann are better off strategically than the mainstay of Humanity in each and every way, literally in everything that matters in war - how are they not the dominant human civilisation in the Galaxy? Why does the Imperium even trudge on, when it could've been easily replaced by the superior Squats wearing fur coats over spacesuits?

One could argue the Emperor and his gang of hyperviolent psychos presented a threat to the Squats during the Great Crusade era, but they apparently never got to meet them, and it's been ten thousand years since the Emperor ascended to the Golden Throne, removing himself from the picture. Why have the Leagues of Votann not been expanding exponentially into the Imperial space, if all the limiters and checks that cripple the mainstay humanity simply do not apply to them?

Frankly speaking, I feel that these two taken together - the Tau, and particularly the Squats, - kill the setting by utterly demolishing its basic themes. What's the point of sacrificing for the Imperium, and tolerating its oppressive policies designed to sustain at least something during the millennia of total war, when there are alternatives - even alternative human civilisations, - that suffer from none of its problems?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 Book Review #50 – The Gold Eaters by Ronald Wright

This was the rare book I had literally never heard of before opening it - a birthday gift from a friend, and the rare one not resulting from some sort of conversation about what books we’ve been meaning to read. It’s the first historical fiction I’ve read in year and years, so I can’t really say how it stands in terms of the rest of the genre. Reading it for myself, I had a great time – though the book did seem confused about which part of ‘historical fiction’ it actually cared about.

The book (primarily) follows Waman, an adolescent boy just coming of age in a nowhere coastal village on the edge of the ascendant and seemingly world-spanning Inca Empire, the demands and products of which are the only outside intrusions upon his life. Feeling stifled at home after his father returns from a period of conscription building roads and bridges in the highlands, he runs away to have some adventures and become a man on a trading ship. And in a stroke of truly cosmic misfortune, on his first voyage they run into a scouting expedition run by one Francisco Pizarro, investigating rumours of a strange land called Peru and its cities of gold.

Waman is abducted and conscripted into service as the Spaniards guide and interpreter. He spends the next decades of his life with an unwilling front-row seat to History unfolding, making and losing friends and endlessly searching for his family and childhood love as the whole world is overthrown again and again around him.

The great strength of the book, I think, is how it manages to portray the civilizations of the past as both familiar and awe-inspiring. The Spanish and Inca Empires are both portrayed almost like fictional kingdoms in a fantasy novel, simultaneously defamilirized and made new and strange, and presented from the point of view of someone whose ideas of normal are at least as strange to us as any of the peoples he meets. More than that, it never stops feeling like a world where people actually lived and worked, one that made sense on a human scale where all its inhabitants could find a place for themselves (or else be forced into one). It was never exactly confusing either -even if it does feel a bit like cheating to jump between points of view to ensure there’s a wide-eyed foreigner needing things explained to them wherever it’s required.

Wright is apparently a historian by trade, and has mostly previously written nonfiction. Given the sheer cornucopia of details about both daily life and the exact sequences of events that led to Spanish dominion, I entirely believe it.

As history, the two things that I most took away from the reading experience were the portrayal of the Inca at their peak as a really vital, world-shaping imperial society on the one hand, and just how drawn out and contingent the process of conquest was, on the other. The book does a great job getting across just how incredible the road- and bridge-building projects and the great imperial cities were, and how rich and organized a society it was (without ever entirely falling into portraying the Inca as some prelapsarian utopia, either, which is how a great many works in the general space seem to screw this up). It then also does an excellent job getting across just how apocalyptic the smallpox epidemic that swept through the empire was, and how ruinous the wars of succession that followed. Pizarro triumphed because he was facing an empire that was a death-choked ruin at war with itself, manipulating and extorting an emperor with many enemies and not much way in the way of skills or legitimacy except that everyone ahead of him was dead.

The other thing that did strike me is that – the historical narrative as I have always received it is that the Spanish conquered their American empire in one single, cataclysmic moment of contact, disease and violence and simple shock leaving them ruling the better part of a continent before anyone even realized what was happening. Which I’d intellectually known was false, but the book really does an amazing job dramatizing the fact that the building of the Spanish empire was a multi-decade – multi-generational, really – affair, and far more a matter of politics and logistics than initial shock an awe.

My main complaint with the book is the matter of genre – it spent the entire back half continuously changing its mind about what it wanted to be. Is this Waman’s story, a man coming of age and scrambling to form a life for himself as the tides of history destroy and remake his world around him and buffet him hither and yon? Or is he just a convenient POV to what’s essentially a rationalized history of (the initial chapters of) the fall of the Inca, improbably standing at the side of and sharing drinks with one famous personage after another to hear their thoughts and see their pivotal deeds? The book never quite settles on an answer, and so Waman’s own arc and personal concerns shift from feeling like thin connective tissue to the emotional core of the story and back several times. The issue gets worse in the latter parts of the book, where it just outright shifts into omniscient exposition of historical events at times.

Also on goodreads this is tagged as a romance and – okay so there is a romance in this book. But it’s the third or fourth most important relationship at most. For the vast majority of the page count it’s just a childhood crush Waman nurses as motivation to get home. If you come in expecting this is mostly be a love story you are going to have a bad time.

But yeah! I should read more historical fiction.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I’ll never be able to forget my own experience pushing my college to divest......I’ll never forget the look I got from one administrator as I entered their building. We had been camped outside for two weeks at that point, and even though the woman who saw me had no idea who I was, she knew exactly who I was. She knew my presence, our presence, meant disruption. And few things are more sacred to the neoliberal institution than avoiding disruption, even when the status quo is harmful investment in fossil fuel corporations, or genocide. And so my presence scared this administrator, and the cops were there within minutes. The feeling of being a student and having the university resort to violence rather than speak with you is immensely hard to forget.

But so too are the broader lessons I learned in student organizing. The feelings are indelible, and yet the bigger picture, the structural knowledge you receive when you go up against a large and powerful institution, stuck with me too. .... I had learned that universities didn’t quite work the way I had imagined. Growing up they had seemed to me, from a distance, to be centers of knowledge and places where life looks a little more like it’s supposed to; people pursue learning and community and aren’t as constrained by work and stress. And there’s a significant kernel of truth to that, but behind the facade is a power structure that cares infinitely more about investments and real estate than the student body. That truth has become more and more real over time, and has been violently laid bare by the boards and administrations themselves in recent weeks. ...

The impact of protest right now matters immensely. It’s impossible to quantify how important it would be if the movement for a Free Palestine in the West built enough power to force our countries to stop funding ethnic cleansing, to stop arming genocide, to stop supporting apartheid. The lives that have been lost are irreplaceable, and the lives that could be saved are invaluable. And, at the same time, we’re seeing millions of people, young and old and everything in between, change in profound ways. In that fact lies the reality that Gaza and Palestinians and this movement we’re seeing all around us are altering the future just as they work to alter the present.

One of the many driving forces changing how people across the globe think, not only about Zionism but about imperialism and society at large, is the simple fact that we cannot unsee what we have seen. ...Decades of propaganda began to fracture in recent years, and shattered in recent months. But it’s more than that – for millions of people across the world there’s also no unseeing U.S. complicity. There’s no unseeing how Israel and the U.S. are virtually alone at the UN, on the world stage, working to protect a genocidal state and enable a genocide again and again. Even as Israel kills yet another UN worker, bringing the total to 190 slain employees of the United Nations, the enabling and participation in Israel’s genocide continues.

People cannot simply forget these actions, these choices that the U.S. and Israel make day after day. I say that as a hope more than as a fact. ...And while students are not facing repression that can be compared to what the Black Panthers and others have faced, they are repeatedly facing mass violence from the state as well as vigilantes. They have also seen how little their schools care about them, how little their government cares about them, and how deeply invested our entire system is in war and imperialism.

..Students who have been attacked, and people everywhere who have seen horrors in Gaza beyond our comprehension, cannot simply forget. We’ve seen how violence abroad is connected to fascism at home. We’ve seen how Israel’s genocide in Gaza is connected to the war machine here in the United States. We’ve seen how it all comes together in a society structured to deprive the many so the few can hoard wealth and resources. Whatever comes next, there’s no turning back. We will struggle towards a better system, both because we want to see it come into existence and because we don’t have the option to return to a healthy status quo. We can’t turn back to the society we might be nostalgic for. That world doesn’t exist anymore; a new one must be built."

#palestine#free palestine#gaza#isreal#genocide#colonization#apartheid#american imperialism#us politics#police state#solidarity#gaza solidarity encampment#solidarity encampments#student protests#student activism#settler colonialism#settler violence#imperialism#us imperialism

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Countries that weaken or stop their net zero and climate actions may be consigning their populations to decades of preventable illness.

Gains from net zero are often presented as global benefits and mainly for future generations. But less fossil fuel use also means less air pollution which results in local health gains right away.

For example, rapid health gains are predicted from policies for US net zero by 2050. By 2035, between 4,000 to 15,000 fewer US residents would die annually from air pollution, saving the US economy $65bn to $128bn, with even greater benefits thereafter.

A study, led by Imperial College London, has found that there are large health gains from UK net zero actions.

Dr Mike Holland, who was part of the study team, said: “Fundamental changes required for net zero will bring long lasting benefits to UK health. Or turn that around. If we don’t take the net zero path, we will be sicker. This would be a double own goal on both climate and health.”

The researchers looked at the net zero pathways for transport and buildings in the UK’s sixth carbon budget. Health improvements came about from less air pollution and also increased exercise from more walking, cycling and e-biking.

Some gains would be expected straight away, as air pollution decreased. These include fewer new cases of asthma in children and adults, as well as reduced hospital admissions for breathing and heart problems. This is consistent with recent health improvements that followed Bradford’s clean air zone and others around Europe.

Fewer strokes and heart attacks would emerge more slowly over five years as air pollution started to reduce. For lung cancer, the reduction in cases would be expected to lag air pollution improvements by six to 20 years.

But the gains would not stop in 2060. Children born in the 2050s would suffer from fewer air pollution illnesses as they grew up and aged as adults. Although less certain than the other illnesses studied, the greatest long-term gains could be in cases of dementia.

Prof Christian Brand, part of the study team, said: “If transport decarbonisation focuses mainly on commuting, how much health improvement and emissions reduction are we leaving on the table? Without policies that support all forms of mobility – especially the short, everyday trips that reduce car dependency – are we missing a crucial opportunity to maximize the full benefits of net zero?”

Participation is key to maximising these gains across society, especially amongwomen and older people. The study found that people walking or cycling for transport could expect to an average of five and half months longer life expectancy, and a healthier life.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I'm a leftist because I can plainly see that capitalism sucks, but I have a really hard time pinning down what I think we should replace it with because I have "agrees with the last theory I read" disease. (Or, more embarrassingly, "agrees with the last Post I read.")

Something I've been wondering about recently is what's the point of planning and arguing over what happens after the revolution anyway? The chances of a successful worker's revolution in my lifetime, let alone the next few decades, feels vanishingly small. The preconditions just feel so far away.

Is there really value in committing to a specific ideology right now, or is it sufficient to say the anarchist future and the ML future (and even, like, the DemSoc future) sound better than what we have now, and require many of the same preconditions, so let's work towards those shared goals now and figure out what comes after in a few decades when the groundwork is actually laid?

i agree with you that i don't think a genuine revolutionary situation will arise (at least, not in the imperial core) within our lifetimes. i also agree that there is a meaningful degree to which the theoretical differences between marxist-leninists & anarchists are far enough from being present and pressing concerns that they should in almost all cases be working together and employing similar tactics and action.

however, i do think there is a value to having an ideological framework: it keeps you consistent. if your ideology is vague and empty, you're liable to (intentional or unintentional) opportunism--you will fill in the gaps or approach new ideas with the default positions, the ones that require the least divergence from hegemonic cultural norms and values.

that sounds a bit ideological-jargony so i'll phrase it another way: if you grow up in a [joker voice] society, you're going to grow up with a lot of assumptions! like, 'cops reduce crime', for example. and if you don't have an underlying theory of capitalist society and how it functions, then it's entirely possible to realize (through experience or analysis) that capitalism is bad and that our society is inherently unjust, but continue thinking 'cops reduce crime' because that's just the default cultural position you grew up with. these two things are pretty impossible to reconcile, right--because of course the actual purpose of cops is to enforce private property rights and maintain the capitalist system of economic relations--but if you don't have a full theoretical framework of capitalism & society that you can use to analyse things, that incoherence is very easy to let slip by!

i also want to say that while i think that anarchists & marxist-leninists (and all other revolutionary) communists share common goals and functionally very similar political projects for our forseeable lifetime, there is a meaningful difference between these two and the 'demsocs' you mentioned. not an uncrossable gulf by any means in terms of working together and forging political alliances--but the steps one takes to agitate and organize the working class in anticipation of a future revolutionary situation, however distant, are imo very functionally different to the steps one takes to advocate for social reform within liberal legislatures. rosa luxemburg put it well when she said there is nothing reformist about supporting trade unions, welfare legislation, as a vehicle for revolutionary class struggle--but when you take these things as ends themselves, i.e., as viable methods for resolving the contradictions of capitalism, you become unable to use them as such a vehicle.

but, yeah. tldr; i think it is far from the most important thing (the most important thing is to be a principled anti-capitalist & anti-imperialist--these are the two litmus tests for whom i can consider a political ally), but it is useful to have an underlying political framework rather than a collection of individual positions, because the latter can lead to contradictory and self-defeating worldviews and political programs

398 notes

·

View notes

Text

In August, 2022, six months after Russian troops invaded Ukraine, a cultural festival named Traditions was held outside Moscow, at the onetime summer retreat of Alexander Pushkin. The star speaker was Alexander Dugin, a scholar and a prominent proponent of the war who has been called the prophet of the new Russian Empire. In his book “Being and Empire” (2023), which runs to a Heideggerian length of seven hundred and eighty-four pages, Dugin characterizes Russia as nothing less than “the last place of the true subject of history in time and space.” His lecture at the festival, “Tradition and History,” was as sprawling as its title suggested. Sitting under a canopy, he extemporized on the seasonal labors of the Russian peasantry, finding in the pre-modern past the “secret center” of the nation’s spiritual life.

For Dugin, the greatest enemy of Russia is liberalism, which he has defined as the “false premise that a human is a separate, autonomous individual—a selfish animal seeking its own benefit. And nothing more.” He has written that “such a liberal person—completely detached from God, history, and society; from the people and culture; from the family and loved ones; from collective morality and ethnic identity—does not exist; and if they do exist, they ought not to.”

After the talk, some members of the audience gathered around Dugin. A young man asked, “This liberalism thing—is it possible that concealed within it is some link to the Lord that will take it and bring it down?”

“Perhaps,” Dugin told him. “That’s why there are people who fight against the liberal world, even within the liberal world.”

“Maybe there is simply a certain substance that has flooded everything, all the brains,” the young man went on. “Then a flame is lit inside it by its offspring, which instantly turns the game upside down?”

The crowd looked befuddled, but Dugin cottoned at once. “Ah,” he said. “That would be Donald Trump!”

Everyone laughed, including Dugin’s daughter, Daria Dugina, who’d accompanied him to the event. A writer and broadcaster, Dugina also worked as a publicist and scheduler for her father. That evening, as they drove in different cars, an explosive attached to the underside of Dugina’s S.U.V. detonated. Her father got out of his vehicle as other drivers stopped. Someone taped the scene; Dugin can be seen stepping among the flaming wreckage, holding his hands to his head. The next day, Russia’s President, Vladimir Putin, sent Dugin a telegram calling Dugina’s death “a vile, cruel crime.”

An obscure Russian paramilitary group claimed responsibility for the bombing, but Moscow insisted that the order had come from Ukraine’s intelligence services. Ukraine denied the charge, but Biden Administration officials reportedly agreed with Russia. The intended victim was presumably Dugin. In some ways, he was a curious target: Dugin is not a politician or a military commander, nor does he seem to be a secret agent, despite predictable rumors to the contrary. Yet his voluminous writings, from books to online essays, have indelibly shaped Russian politics and policy. His conviction that the Russian Federation’s destiny is to become a holy empire along tsarist lines, a notion that he has been promoting for more than three decades, has been adopted by much of the Russian political élite—including by Putin himself. So has Dugin’s long-held belief that Ukraine is a proxy battlefield for a larger mortal conflict with the West. Whereas the Biden Administration opposed Russia’s imperial aggression, the Trump Administration appears willing to ratify it, if not to mimic it.

Since invading Ukraine, Putin has regularly invoked old arguments about Russia’s imperial role in the world, yet his references amount to a mercenary patchwork. In contrast, Dugin’s fluency with these arguments is as formidable as his loathing for liberalism is sincere. A close reading of his work offers an answer to the central question of the war, a question that, after three years, has still not been adequately addressed: Just why did Putin want to conquer Ukraine?

Only some of Dugin’s writing is about matters of state. Other pet subjects are literature, art, theology, music, and philosophy. He composes poetry (the not bad “In a Soviet Basement” contains the lines “He spins in a waltz, black as a cat / In his hands a Walter, in his hands a Walter / In his hands, Walter Scott”), records experimental music, and translates an array of right-wing European writers into Russian, releasing the books through his publishing house. Until 2014, he taught sociology at Moscow State University. He is not a Kremlin insider but, rather, a member of Moscow’s intelligentsia—or what now passes for it. He has written, co-written, or edited nearly a hundred books, and in his graphomania, if not in the quality of his work, he is a throwback to the Golden Age of Russian literature, in the nineteenth century. And, like the conservative Slavophile authors of that era who first formulated the nativist views that have resurged under Putin—such as the historian Mikhail Pogodin—Dugin assails the West and its values. He inveighs against democracy, secularism, individualism, civil society, multiculturalism, human rights, sexual openness, technology, scientific rationalism, and reason in general, which he rejects in favor of the mystical revelations of the Russian Orthodox Church. Although he is an avid tweeter and frequently posts on Telegram and Facebook, he claims to have no use for modernity. He once wrote that “the best course would be to eradicate the state and replace it with the Holy Empire.”

“Dugin can write a book in one night,” Marat Guelman, a former political consultant to the administration of Boris Yeltsin and a former acquaintance of Dugin’s, told me. “He is full of words.” Some of those words are sound enough. In “Templars of the Proletariat,” from 1997, Dugin observes that “the Russian national idea” is “paradoxical,” and “a colossal labor of the soul is required in order to make sense of it.” But, just when you think he is onto something serious, he says something risibly unserious. In his 2012 book, “Putin vs. Putin,” he presents pages of admissible arguments about Putin’s lack of vision for Russia’s future, only to announce, with a note of portentous climax, that Putin took office on a date predicted by Nostradamus. A critique of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, which lucidly dissects the contradictions of perestroika, is undercut by musings on the occult implications of the “characteristic mark” on the former premier’s forehead. Dugin’s Russian critics like to say that he has kasha v golove—porridge in the head. Alexander Verkhovsky, a scholar of Russian extremism, dryly told me, “His books are very impressive, especially if, when you read them, you’re not thinking much.”

Nevertheless, you can find Dugin’s latest works in Russian bookstores, and he has found some avid readers abroad. The more extreme elements of the European New Right love his disdain for democracy. His books have been translated into French, Spanish, German, Italian, and English; in the United States, at least one of them—a 2014 treatise on Martin Heidegger—was published by a company run by the white nationalist Richard Spencer. Dugin makes President Trump’s accounts of American decline seem modest by comparison. In “Being and Empire,” Dugin calls the U.S. an immoral wasteland—“the direct opposite of the Holy Empire.” (His writing is full of italics.)

Last April, Dugin was interviewed by Tucker Carlson during the pundit’s tour of Russia. The expression of amiable skepticism that Carlson had worn through an earlier interview with Putin descended into a baffled frown when Dugin told him that the triumph of Western liberalism, which promotes “individualism” and rejects all kinds of “collective identities,” had led mankind to “the historical terminal station” where all ties to the past—religion, family, nation-state—were cut and “human identity” was “abandoned.” His anti-Western militancy is so intense that the U.S. and the European Union have both placed sanctions on him.

More dramatically, Ukrainian prosecutors have charged Dugin with genocide, though he appears to have played no material role in the war. His crime is rhetorical: he argues that the destruction of Ukraine is essential to Russia’s continued existence. In his 1997 book “Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia,” which brought him to fame in his home country, he writes, “The existence of Ukraine within its current borders, and with its current status as a ‘sovereign state,’ is tantamount to delivering a monstrous blow to Russia’s geopolitical security.” Although other Russian intellectuals have called for Ukraine’s incorporation into the Russian Federation, none have done so for quite so long, or with such a murderous tone, as Dugin. “Russia can be either great or not at all,” he writes in his 2014 book “Ukraine: My War,” adding, “Of course, for greatness, people always, in all centuries, pay a very heavy price, sometimes shedding entire seas of blood.”

Putin was once known for his distaste for ideology. Just before becoming his country’s acting President, in 2000, he wrote, “I am against the restoration of an official state ideology in Russia in any form.” In the decade after he took office, whenever he did resort to violence abroad—continuing the war in Chechnya; invading Georgia, in 2008—no grand ideology lay behind it. These were acts of opportunism by a cold-eyed pragmatist. The same could be said of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, which was brazen and unlawful but also virtually bloodless, so much so that it moved Henry Kissinger to call Putin “a serious strategist.” (The mandarin of Realpolitik knew no higher praise.)

Putin’s decision, in 2022, to try to conquer all of Ukraine can’t be arrived at by extrapolating from those prior invasions. This was less the gambit of a master of Realpolitik than the reckless gamble of an ideologue, and the impulse to invade belongs to an antique tradition of Russian political thought—a messianic imperialism that originates not in the Soviet Union (which the former K.G.B. agent Putin has been accused, imprecisely, of wanting to revive) but in tsarist Russia.

Today, Putin talks like a Romanov-era zealot. This once terse apparatchik seems to have succumbed to the notion, as Dostoyevsky put it in “The Brothers Karamazov,” that “all true Russians are philosophers.” Putin has even taken to quoting Dostoyevsky; not too long ago, the idea that he’d ever read Dostoyevsky would have been laughable. Putin waxes on about the “civilizational identity” that underlies Russia’s claims to cultural dominance, and about the “historical and spiritual space” of Greater Russia, which, naturally, includes all of Ukraine. “The world has entered a period of fundamental, revolutionary transformation,” he declared in a speech several months after attempting to topple Kyiv. Russia, he said, was defending not only its national interests but also the oppressed of the world against the “Western élites” who exploited them. His country had made “a glorious spiritual choice.”

The speech could have been written by Dugin. In “Foundations of Geopolitics,” he writes, “The Russian people certainly belong to the messianic peoples, and, like any messianic people, it has a universal, pan-human significance.” Putin has come to sound like Dugin to such an extent that Dugin has been called Putin’s Rasputin and Putin’s philosopher. “Putin’s Brain” was the headline of a Foreign Affairs profile of Dugin; “Inside ‘Putin’s Brain’ ” is the title of a recent book. All oversell the point. Putin’s telegram of condolence to Dugin notwithstanding, there is little to suggest that the two men have a personal relationship. But wars don’t arise from personal relationships. They arise from ideas—from the accretion, and corruption, of ideas over time. Putin’s assimilation of Dugin’s thinking is likely indirect, maybe even unconscious. It might be more apt to call Dugin the Russian President’s imperial id. When I asked the historian Andrei Tsygankov, the author of “Russia and the West from Alexander to Putin,” about the pair’s connection, he said, “Putin uses Dugin in the way that the tsars used the Slavophiles”—for “mobilizing the population to their cause.”

When Putin announced the start of his “special military operation” in Ukraine, on February 24, 2022, he didn’t mention that country by name until the latter half of a nearly four-thousand-word speech. The first half was taken up with excoriating the West, and especially the U.S., that “empire of lies,” for forcing the war on Russia by seeking to “destroy our traditional values and force on us their false values . . . that are directly leading to degradation and degeneration, because they are contrary to human nature.” That speech, too, could have been written by Dugin, who has written that “the entirety of Russian history is a dialectical argument with the West and against Western culture.”

Putin and Dugin came to prominence simultaneously, in the nineteen-nineties. After leaving the K.G.B., Putin became the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg, then joined the staff of President Yeltsin, who made him chief of the Federal Security Service (the K.G.B.’s successor), then Prime Minister, and eventually tapped him for the Presidency. This was one way up in post-Soviet Russia. Another was through the reactionary underground. This was Dugin’s path. February 24, 2022, can be seen as the day those two trajectories, the official and the unofficial, collided.

Putin describes himself as a “pure and utterly successful product of Soviet patriotic education” in “First Person,” a collection of interviews with him published in 2000 and the closest thing we have to an autobiography. Dugin is a more exotic specimen in Russia: a child of the sixties, almost in the same sense that Westerners would use that term. He was born in Moscow to a minor official in 1962, nine years after the death of Joseph Stalin, from whose murderous purges the Russian intelligentsia was slowly recovering. Writers and other educated élites were then “under such monstrous ideological pressure that one wonders why art and the humanities have not altogether vanished in our country,” the dissident Andrei Sakharov wrote.

Stalin suppressed Ukrainian culture and caused the death of untold numbers of Ukrainians. While Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, continued expanding the Soviet imperium, he reversed Stalin’s policy on Ukraine. Khrushchev, who grew up in Ukraine, elevated it to the status of the second most powerful Soviet republic after Russia and, in 1954, transferred Crimea to its control—an act for which Putin assails him today. He also instituted the thaw, as it was known, relaxing cultural restrictions. The year Dugin was born, Khrushchev both precipitated the Cuban missile crisis and approved the publication of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s account of a Soviet Gulag, “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich,” arguably the most subversive novel to have been legally published in the U.S.S.R. Beneath the sanctioned renaissance sprang up an illicit counterculture that defied the Soviet cult of reason with occult religion.

From this spiritualist subculture emerged the young Dugin, by all accounts unforgettably. Tall, regal, and formal looking, he looked like “a representative of a higher race,” one of his friends said. He was a walking paradox: in the aristocratic Russian manner, he wore cavalry jodhpurs and rolled his “R”s; at the same time, he adopted the style of a medieval peasant, complete with a “pudding bowl” haircut. The writer and poet Eduard Limonov recalls in his memoir “My Political Biography” that Dugin was a “plump, cheeky, belly, busty, bearded young man” who was “full of exaggerated emotions.”

While Putin got a law degree and entered the intelligence services, Dugin dropped out of aviation school and took up with a different sort of secret society: the Iuzhinskii Circle, a group of writers in Moscow’s “metaphysical underground.” The circle had been formed, in the nineteen-sixties, by Yuri Mamleev, a novelist who has noted, “We felt distinctly that there was a bottomless chasm beneath us and that the whole planet was sinking into it.” The first members of the salon gathered in Mamleev’s small Moscow apartment to listen to him read from his writings, which were too outlandish to be published even during the thaw. One novel, “Shatuny,” was regarded as a kind of sacred text. A late-twentieth-century answer to “Crime and Punishment,” it follows a half-witted, sex-crazed serial killer as he screws and slaughters his way through Russia, in an effort to glimpse his victims’ souls. Dugin said that the novel was “the secret seed of the nineteen-sixties,” writing, “It is as though what you hold in your hands is not a book, but an empty space, a black, impish vortex that can suck large objects into itself.” A similar feeling may have been induced by the circle’s initiation rites—Bacchic episodes with copious drinking and sex.

Mamleev immigrated to the U.S. in 1974, before Dugin joined the circle. When Dugin became a member, the group was meeting at the dacha of Sergey Zhigalkin, a mystical philosopher who became Dugin’s close friend. Zhigalkin told me that life in the circle was not just intellectually risky; members were in danger of being arrested or sent to a mental asylum. He said that Dugin opposed both the Soviet system and “modern civilization as a whole.” This gave Dugin a grim outlook, Zhigalkin explained: “In Russia, and America, too, we live in the paradigm of a new time: in postmodernism, which is purely earthly and has no spiritual dimension—that is the tragedy.”

Dugin began not as a writer but as a musician. He brought a guitar and an accordion to circle gatherings and performed original material. Charles Clover, who was a Financial Times correspondent in Moscow at the time, chronicles the metaphysical underground in his book “Black Wind, White Snow,” and writes that Dugin’s songs were “composed of as many antisocial elements as its creator could find.” Clover recalls, “Strumming away around a bonfire in the evening sunset, he belted out a song, ‘Fuck the Damn Sovdep.’ ” (The Soviet Deputies were the organs of local government in the U.S.S.R.) The lyrics essentially called for mass murder of the Soviet leadership: “Two million in the river / two million in the oven / Our revolvers will not misfire.” Eventually, Dugin had his own cult following. “We just fell down and worshipped him,” one acolyte told Clover. “He was like a messiah.”

Soon enough, Dugin came to the attention of Putin’s colleagues in the K.G.B. Dugin’s father—his government career hindered, or possibly ruined, by his son—may have tipped off agents. In 1983, Dugin was sent to K.G.B. headquarters after performing dissident songs at a Moscow art studio. Agents later discovered a samizdat archive of Mamleev’s writings at the home of Dugin’s parents. According to Clover, Dugin was told by his interrogator, “The U.S.S.R. will stand forever. It’s an eternal reality.”

Dugin was released after a night of questioning and started working odd jobs while exhausting library shelves. He inhaled the European canon and Eastern philosophy. M. Gessen, in their book “The Future Is History,” relates an anecdote about Dugin wanting to read Heidegger’s “Being and Time.” He couldn’t locate a Russian translation, so he tracked down a German copy—on microfilm. He retrofitted a 35-mm. hand-cranked projector on his desk. “By the time he was done with ‘Being and Time,’ Dugin needed glasses,” Gessen writes. He’d also taught himself German. He then learned English, French, and Italian, too, along with various ancient languages. He gravitated to latter-day Continental metaphysicians—Heidegger, the German radical conservatives Oswald Spengler and Carl Schmitt, the traditionalist school of René Guénon and Julius Evola—who shared a hopelessness about Western civilization, if not civilization generally, and a morbid aversion to modernity. A striking number of these thinkers were members of the Nazi Party, or were otherwise fascist. Dugin could declaim on their work for hours, and did.

“He liked to give a lecture,” Misha Verbitsky, a mathematician and a former friend of Dugin’s, told me. “He dared to think in directions where nobody else would. Like Nietzsche, I suppose. Of course, some of the directions were very unhealthy.”