#entablature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fame and Erato, Muse of Love Poetry

Artist: Sebastiano Conca (Italian, 1680-1764)

Date: c. 1725

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States

Description

The precise subject of this painting is not clear, but it appears to represent the Muses of epic and lyric poetry, Calliope and Erato. The figure on the right, Erato, is identified by her lyre—the attribute of the Muse of lyric and amorous poetry. The figure on the left is more difficult to identify because Conca did not follow closely the standard representations of allegorical figures. The presence of the globe and of the compass held by the winged goddess are attributes of Urania, the Muse of astronomy, while the book and crown of laurel are attributes of Calliope, the muse of epic poetry.

#allegorical art#allegorical scene#muses#epic poetry#lyric poetry#globe#compass#winged goddess#urania#muse of astronomy#book#laurel wreth#calliope#muse of epic poetry#female figures#putti#mantle#cloud#golden crown#blue mantle#lyre#gold circlet#neoclassical architecture#fluted columns#entablature#open book#painting#oil on canvas#fine art#oil painting

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Entablature.]

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sun Room Medium Mid-sized contemporary sunroom design idea

0 notes

Photo

Traditional Sunroom An illustration of a mid-sized traditional sunroom style

0 notes

Text

Contemporary Sunroom - Medium

Mid-sized contemporary sunroom design idea

0 notes

Photo

Sun Room Medium Mid-sized contemporary sunroom design idea

0 notes

Text

Fantasy Guide to Interiors

As a followup to the very popular post on architecture, I decided to add onto it by exploring the interior of each movement and the different design techniques and tastes of each era. This post at be helpful for historical fiction, fantasy or just a long read when you're bored.

Interior Design Terms

Reeding and fluting: Fluting is a technique that consists a continuous pattern of concave grooves in a flat surface across a surface. Reeding is it's opposite.

Embossing: stamping, carving or moulding a symbol to make it stand out on a surface.

Paneling: Panels of carved wood or fabric a fixed to a wall in a continuous pattern.

Gilding: the use of gold to highlight features.

Glazed Tile: Ceramic or porcelain tiles coated with liquid coloured glass or enamel.

Column: A column is a pillar of stone or wood built to support a ceiling. We will see more of columns later on.

Bay Window: The Bay Window is a window projecting outward from a building.

Frescos: A design element of painting images upon wet plaster.

Mosaic: Mosaics are a design element that involves using pieces of coloured glass and fitted them together upon the floor or wall to form images.

Mouldings: ornate strips of carved wood along the top of a wall.

Wainscoting: paneling along the lower portion of a wall.

Chinoiserie: A European take on East Asian art. Usually seen in wallpaper.

Clerestory: A series of eye-level windows.

Sconces: A light fixture supported on a wall.

Niche: A sunken area within a wall.

Monochromatic: Focusing on a single colour within a scheme.

Ceiling rose: A moulding fashioned on the ceiling in the shape of a rose usually supporting a light fixture.

Baluster: the vertical bars of a railing.

Façade: front portion of a building

Lintel: Top of a door or window.

Portico: a covered structure over a door supported by columns

Eaves: the part of the roof overhanging from the building

Skirting: border around lower length of a wall

Ancient Greece

Houses were made of either sun-dried clay bricks or stone which were painted when they dried. Ground floors were decorated with coloured stones and tiles called Mosaics. Upper level floors were made from wood. Homes were furnished with tapestries and furniture, and in grand homes statues and grand altars would be found. Furniture was very skillfully crafted in Ancient Greece, much attention was paid to the carving and decoration of such things. Of course, Ancient Greece is ancient so I won't be going through all the movements but I will talk a little about columns.

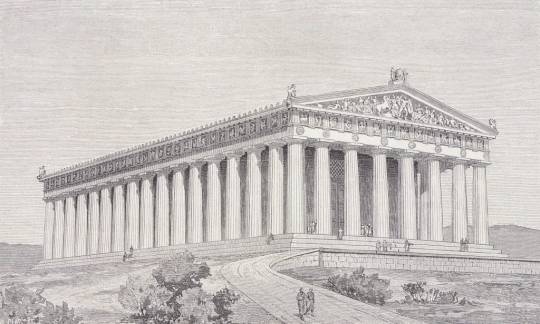

Doric: Doric is the oldest of the orders and some argue it is the simplest. The columns of this style are set close together, without bases and carved with concave curves called flutes. The capitals (the top of the column) are plain often built with a curve at the base called an echinus and are topped by a square at the apex called an abacus. The entablature is marked by frieze of vertical channels/triglyphs. In between the channels would be detail of carved marble. The Parthenon in Athens is your best example of Doric architecture.

Ionic: The Ionic style was used for smaller buildings and the interiors. The columns had twin volutes, scroll-like designs on its capital. Between these scrolls, there was a carved curve known as an egg and in this style the entablature is much narrower and the frieze is thick with carvings. The example of Ionic Architecture is the Temple to Athena Nike at the Athens Acropolis.

Corinthian: The Corinthian style has some similarities with the Ionic order, the bases, entablature and columns almost the same but the capital is more ornate its base, column, and entablature, but its capital is far more ornate, commonly carved with depictions of acanthus leaves. The style was more slender than the others on this list, used less for bearing weight but more for decoration. Corinthian style can be found along the top levels of the Colosseum in Rome.

Tuscan: The Tuscan order shares much with the Doric order, but the columns are un-fluted and smooth. The entablature is far simpler, formed without triglyphs or guttae. The columns are capped with round capitals.

Composite: This style is mixed. It features the volutes of the Ionic order and the capitals of the Corinthian order. The volutes are larger in these columns and often more ornate. The column's capital is rather plain. for the capital, with no consistent differences to that above or below the capital.

Ancient Rome

Rome is well known for its outward architectural styles. However the Romans did know how to add that rizz to the interior. Ceilings were either vaulted or made from exploded beams that could be painted. The Romans were big into design. Moasics were a common interior sight, the use of little pieces of coloured glass or stone to create a larger image. Frescoes were used to add colour to the home, depicting mythical figures and beasts and also different textures such as stonework or brick. The Romans loved their furniture. Dining tables were low and the Romans ate on couches. Weaving was a popular pastime so there would be tapestries and wall hangings in the house. Rich households could even afford to import fine rugs from across the Empire. Glass was also a feature in Roman interior but windows were usually not paned as large panes were hard to make. Doors were usually treated with panels that were carved or in lain with bronze.

Ancient Egypt

Egypt was one of the first great civilisations, known for its immense and grand structures. Wealthy Egyptians had grand homes. The walls were painted or plastered usually with bright colours and hues. The Egyptians are cool because they mapped out their buildings in such a way to adhere to astrological movements meaning on special days if the calendar the temple or monuments were in the right place always. The columns of Egyptian where thicker, more bulbous and often had capitals shaped like bundles of papyrus reeds. Woven mats and tapestries were popular decor. Motifs from the river such as palms, papyrus and reeds were popular symbols used.

Ancient Africa

African Architecture is a very mixed bag and more structurally different and impressive than Hollywood would have you believe. Far beyond the common depictions of primitive buildings, the African nations were among the giants of their time in architecture, no style quite the same as the last but just as breathtaking.

Rwandan Architecture: The Rwandans commonly built of hardened clay with thatched roofs of dried grass or reeds. Mats of woven reeds carpeted the floors of royal abodes. These residences folded about a large public area known as a karubanda and were often so large that they became almost like a maze, connecting different chambers/huts of all kinds of uses be they residential or for other purposes.

Ashanti Architecture: The Ashanti style can be found in present day Ghana. The style incorporates walls of plaster formed of mud and designed with bright paint and buildings with a courtyard at the heart, not unlike another examples on this post. The Ashanti also formed their buildings of the favourite method of wattle and daub.

Nubian Architecture: Nubia, in modern day Ethiopia, was home to the Nubians who were one of the world's most impressive architects at the beginning of the architecture world and probably would be more talked about if it weren't for the Egyptians building monuments only up the road. The Nubians were famous for building the speos, tall tower-like spires carved of stone. The Nubians used a variety of materials and skills to build, for example wattle and daub and mudbrick. The Kingdom of Kush, the people who took over the Nubian Empire was a fan of Egyptian works even if they didn't like them very much. The Kushites began building pyramid-like structures such at the sight of Gebel Barkal

Japanese Interiors

Japenese interior design rests upon 7 principles. Kanso (簡素)- Simplicity, Fukinsei (不均整)- Asymmetry, Shizen (自然)- Natural, Shibumi (渋味) – Simple beauty, Yugen (幽玄)- subtle grace, Datsuzoku (脱俗) – freedom from habitual behaviour, Seijaku (静寂)- tranquillity.

Common features of Japanese Interior Design:

Shoji walls: these are the screens you think of when you think of the traditional Japanese homes. They are made of wooden frames, rice paper and used to partition

Tatami: Tatami mats are used within Japanese households to blanket the floors. They were made of rice straw and rush straw, laid down to cushion the floor.

Genkan: The Genkan was a sunken space between the front door and the rest of the house. This area is meant to separate the home from the outside and is where shoes are discarded before entering.

Japanese furniture: often lowest, close to the ground. These include tables and chairs but often tanked are replaced by zabuton, large cushions. Furniture is usually carved of wood in a minimalist design.

Nature: As both the Shinto and Buddhist beliefs are great influences upon architecture, there is a strong presence of nature with the architecture. Wood is used for this reason and natural light is prevalent with in the home. The orientation is meant to reflect the best view of the world.

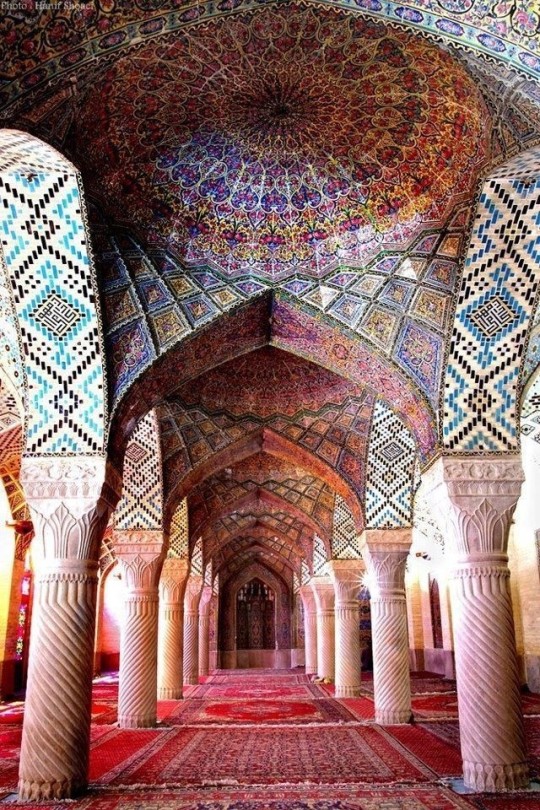

Islamic World Interior

The Islamic world has one of the most beautiful and impressive interior design styles across the world. Colour and detail are absolute staples in the movement. Windows are usually not paned with glass but covered in ornate lattices known as jali. The jali give ventilation, light and privacy to the home. Islamic Interiors are ornate and colourful, using coloured ceramic tiles. The upper parts of walls and ceilings are usually flat decorated with arabesques (foliate ornamentation), while the lower wall areas were usually tiled. Features such as honeycombed ceilings, horseshoe arches, stalactite-fringed arches and stalactite vaults (Muqarnas) are prevalent among many famous Islamic buildings such as the Alhambra and the Blue Mosque.

Byzantine (330/395–1453 A. D)

The Byzantine Empire or Eastern Roman Empire was where eat met west, leading to a melting pot of different interior designs based on early Christian styles and Persian influences. Mosaics are probably what you think of when you think of the Byzantine Empire. Ivory was also a popular feature in the Interiors, with carved ivory or the use of it in inlay. The use of gold as a decorative feature usually by way of repoussé (decorating metals by hammering in the design from the backside of the metal). Fabrics from Persia, heavily embroidered and intricately woven along with silks from afar a field as China, would also be used to upholster furniture or be used as wall hangings. The Byzantines favoured natural light, usually from the use of copolas.

Indian Interiors

India is of course, the font of all intricate designs. India's history is sectioned into many eras but we will focus on a few to give you an idea of prevalent techniques and tastes.

The Gupta Empire (320 – 650 CE): The Gupta era was a time of stone carving. As impressive as the outside of these buildings are, the Interiors are just as amazing. Gupta era buildings featured many details such as ogee (circular or horseshoe arch), gavaksha/chandrashala (the motif centred these arches), ashlar masonry (built of squared stone blocks) with ceilings of plain, flat slabs of stone.

Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526): Another period of beautifully carved stone. The Delhi sultanate had influence from the Islamic world, with heavy uses of mosaics, brackets, intricate mouldings, columns and and hypostyle halls.

Mughal Empire (1526–1857): Stonework was also important on the Mughal Empire. Intricately carved stonework was seen in the pillars, low relief panels depicting nature images and jalis (marble screens). Stonework was also decorated in a stye known as pietra dura/parchin kari with inscriptions and geometric designs using colored stones to create images. Tilework was also popular during this period. Moasic tiles were cut and fitted together to create larger patters while cuerda seca tiles were coloured tiles outlined with black.

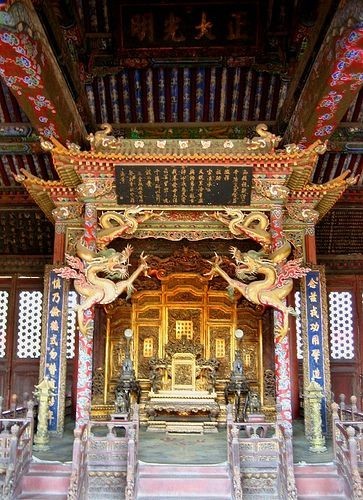

Chinese Interiors

Common features of Chinese Interiors

Use of Colours: Colour in Chinese Interior is usually vibrant and bold. Red and Black are are traditional colours, meant to bring luck, happiness, power, knowledge and stability to the household.

Latticework: Lattices are a staple in Chinese interiors most often seen on shutters, screens, doors of cabinets snf even traditional beds.

Lacquer: Multiple coats of lacquer are applied to furniture or cabinets (now walls) and then carved. The skill is called Diaoqi (雕漆).

Decorative Screens: Screens are used to partition off part of a room. They are usually of carved wood, pained with very intricate murals.

Shrines: Spaces were reserved on the home to honour ancestors, usually consisting of an altar where offerings could be made.

Of course, Chinese Interiors are not all the same through the different eras. While some details and techniques were interchangeable through different dynasties, usually a dynasty had a notable style or deviation. These aren't all the dynasties of course but a few interesting examples.

Song Dynasty (960–1279): The Song Dynasty is known for its stonework. Sculpture was an important part of Song Dynasty interior. It was in this period than brick and stone work became the most used material. The Song Dynasty was also known for its very intricate attention to detail, paintings, and used tiles.

Ming Dynasty(1368–1644): Ceilings were adorned with cloisons usually featuring yellow reed work. The floors would be of flagstones usually of deep tones, mostly black. The Ming Dynasty favoured richly coloured silk hangings, tapestries and furnishings. Furniture was usually carved of darker woods, arrayed in a certain way to bring peace to the dwelling.

Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD): Interior walls were plastered and painted to show important figures and scenes. Lacquer, though it was discovered earlier, came into greater prominence with better skill in this era.

Tang Dynasty (618–907) : The colour palette is restrained, reserved. But the Tang dynasty is not without it's beauty. Earthenware reached it's peak in this era, many homes would display fine examples as well. The Tang dynasty is famous for its upturned eaves, the ceilings supported by timber columns mounted with metal or stone bases. Glazed tiles were popular in this era, either a fixed to the roof or decorating a screen wall.

Romanesque (6th -11th century/12th)

Romanesque Architecture is a span between the end of Roman Empire to the Gothic style. Taking inspiration from the Roman and Byzantine Empires, the Romanesque period incorporates many of the styles. The most common details are carved floral and foliage symbols with the stonework of the Romanesque buildings. Cable mouldings or twisted rope-like carvings would have framed doorways. As per the name, Romansque Interiors relied heavily on its love and admiration for Rome. The Romanesque style uses geometric shapes as statements using curves, circles snf arches. The colours would be clean and warm, focusing on minimal ornamentation.

Gothic Architecture (12th Century - 16th Century)

The Gothic style is what you think of when you think of old European cathedrals and probably one of the beautiful of the styles on this list and one of most recognisable. The Gothic style is a dramatic, opposing sight and one of the easiest to describe. Decoration in this era became more ornate, stonework began to sport carving and modelling in a way it did not before. The ceilings moved away from barreled vaults to quadripartite and sexpartite vaulting. Columns slimmed as other supportive structures were invented. Intricate stained glass windows began their popularity here. In Gothic structures, everything is very symmetrical and even.

Mediaeval (500 AD to 1500)

Interiors of mediaeval homes are not quite as drab as Hollywood likes to make out. Building materials may be hidden by plaster in rich homes, sometimes even painted. Floors were either dirt strewn with rushes or flagstones in larger homes. Stonework was popular, especially around fireplaces. Grand homes would be decorated with intricate woodwork, carved heraldic beasts and wall hangings of fine fabrics.

Renaissance (late 1300s-1600s)

The Renaissance was a period of great artistry and splendor. The revival of old styles injected symmetry and colour into the homes. Frescoes were back. Painted mouldings adorned the ceilings and walls. Furniture became more ornate, fixed with luxurious upholstery and fine carvings. Caryatids (pillars in the shape of women), grotesques, Roman and Greek images were used to spruce up the place. Floors began to become more intricate, with coloured stone and marble. Modelled stucco, sgraffiti arabesques (made by cutting lines through a layer of plaster or stucco to reveal an underlayer), and fine wall painting were used in brilliant combinations in the early part of the 16th century.

Tudor Interior (1485-1603)

The Tudor period is a starkly unique style within England and very recognisable. Windows were fixed with lattice work, usually casement. Stained glass was also in in this period, usually depicting figures and heraldic beasts. Rooms would be panelled with wood or plastered. Walls would be adorned with tapestries or embroidered hangings. Windows and furniture would be furnished with fine fabrics such as brocade. Floors would typically be of wood, sometimes strewn with rush matting mixed with fresh herbs and flowers to freshen the room.

Baroque (1600 to 1750)

The Baroque period was a time for splendor and for splashing the cash. The interior of a baroque room was usually intricate, usually of a light palette, featuring a very high ceiling heavy with detail. Furniture would choke the room, ornately carved and stitched with very high quality fabrics. The rooms would be full of art not limited to just paintings but also sculptures of marble or bronze, large intricate mirrors, moldings along the walls which may be heavily gilded, chandeliers and detailed paneling.

Victorian (1837-1901)

We think of the interiors of Victorian homes as dowdy and dark but that isn't true. The Victorians favoured tapestries, intricate rugs, decorated wallpaper, exquisitely furniture, and surprisingly, bright colour. Dyes were more widely available to people of all stations and the Victorians did not want for colour. Patterns and details were usually nature inspired, usually floral or vines. Walls could also be painted to mimic a building material such as wood or marble and most likely painted in rich tones. The Victorians were suckers for furniture, preferring them grandly carved with fine fabric usually embroidered or buttoned. And they did not believe in minimalism. If you could fit another piece of furniture in a room, it was going in there. Floors were almost eclusively wood laid with the previously mentioned rugs. But the Victorians did enjoy tiled floors but restricted them to entrances. The Victorians were quite in touch with their green thumbs so expect a lot of flowers and greenery inside. with various elaborately decorated patterned rugs. And remember, the Victorians loved to display as much wealth as they could. Every shelf, cabinet, case and ledge would be chocked full of ornaments and antiques.

Edwardian/The Gilded Age/Belle Epoque (1880s-1914)

This period (I've lumped them together for simplicity) began to move away from the deep tones and ornate patterns of the Victorian period. Colour became more neutral. Nature still had a place in design. Stained glass began to become popular, especially on lampshades and light fixtures. Embossing started to gain popularity and tile work began to expand from the entrance halls to other parts of the house. Furniture began to move away from dark wood, some families favouring breathable woods like wicker. The rooms would be less cluttered.

Art Deco (1920s-1930s)

The 1920s was a time of buzz and change. Gone were the refined tastes of the pre-war era and now the wow factor was in. Walls were smoother, buildings were sharper and more jagged, doorways and windows were decorated with reeding and fluting. Pastels were in, as was the heavy use of black and white, along with gold. Mirrors and glass were in, injecting light into rooms. Gold, silver, steel and chrome were used in furnishings and decor. Geometric shapes were a favourite design choice. Again, high quality and bold fabrics were used such as animal skins or colourful velvet. It was all a rejection of the Art Noveau movement, away from nature focusing on the man made.

Modernism (1930 - 1965)

Modernism came after the Art Deco movement. Fuss and feathers were out the door and now, practicality was in. Materials used are shown as they are, wood is not painted, metal is not coated. Bright colours were acceptable but neutral palettes were favoured. Interiors were open and favoured large windows. Furniture was practical, for use rather than the ornamentation, featuring plain details of any and geometric shapes. Away from Art Deco, everything is straight, linear and streamlined.

#This took forever#I'm very tired#But enjoy#I covered as much as I could find#Fantasy Guide to interiors#interior design#Architecture#writings#writing resources#Writing reference#Writing advice#Writer's research#writing research#Writer's rescources#Writing help#Mediaeval#Renaissance#Chinese Interiors#Japanese Interiors#Indian interiors#writing#writeblr#writing reference#writing advice#writer#spilled words#writers

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Architecture Vocabulary

Arcade: a succession of arches supported on columns. An arcade can be free-standing covered passage or attached to a wall, as seen on the right.

Arch: the curved support of a building or doorway. The tops of the arches can be curved, semicircular, pointed, etc.

Architrave: the lowest part of the entablature that sits directly on the capitals (tops) of the columns.

Capital: the top portion of a column. In classical architecture, the architectural order is usually identified by design of the capital (Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian).

Classical: of or pertaining to Classicism.

Classicism: a preference or regard for the principles of Greek and Roman art and architecture. Common classicizing architecture is a sense of balance, proportion, and “ideal” beauty.

Column: an upright post, usually square, round, or rectangular. It can be used as a support or attached to a wall for decoration. In classical architecture, columns are composed of a capital, shaft, and a base (except in the Doric order).

Cornice: the rectangular band above the frieze, below the pediment.

Dome: a half-sphere curvature constructed on a circular base, as seen on the right.

Entablature: the upper portion of an order, it includes the architrave, frieze and cornice.

Frieze: the wide rectangular section on the entablature, above the architrave and below the cornice. In the Doric order, the frieze is often decorated with triglyphs (altering tablets of vertical groves) and the plain, rectangular bands spaced between the triglyphs (called metopes).

Metopes: the rectangular slabs that adorned the outside of Doric temples, just above the exterior colonnade.

Order: an ancient style of architecture. The classical orders are Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian. An order consists of a column, with a distinctive capital, supporting the entablature and pediment.

Pediment: a classical element that forms a triangular shape above the entablature. The pediment is often decorated with statues and its sides can be curved or straight.

Pronaos (pro-NAY-us): the entrance hall of a temple.

Triglyphs: a decorative element of a frieze consisting of three vertical units.

Vault: an arched ceiling usually made of wood or stone, as seen on the right.

Source ⚜ More: Word Lists ⚜ Notes ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#writeblr#writing notes#terminology#writers on tumblr#architecture#writing prompt#poetry#literature#poets on tumblr#spilled ink#creative writing#writing reference#dark academia#light academia#lit#worldbuilding#studyblr#langblr#booklr#bookblr#word list#writing resources

711 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castlecor, Ballymahon, County Longford, Ireland,

The property was not intended to be a permanent residence but instead a hunting lodge, of two storeys with the lower floor containing kitchens and service rooms for the single Great Room above.

And what a great room it proves to be: a vast octagonal space, 42 feet across with round-headed windows on every second side and single rooms (measuring 20 by 14 feet) opening off the other four.

To heat such a substantial area, the centre of the room is taken up by a four-sided fireplace, each of them directly facing one of the windows, the light from which is reflected in mirrors set above the chimneypieces.

The structure is framed in each corner by a towering Corinthian column, these supporting a richly ornamented entablature, each having at its centre a mask of Apollo.

#art#design#architecture#history#luxury lifestyle#style#luxury house#castle#interior design#castlecor#ballymahon#longford#ireland#chimney#fresco#fireplace#lodge#great room

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

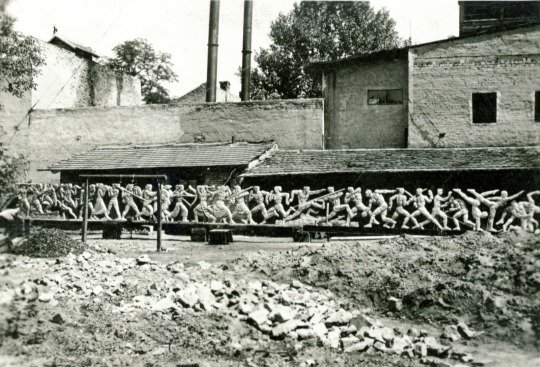

Relief by András Kocsis, which was later placed above the main entablature of the National Sports Hall (later the Gerevich Aladár National Sports Hall), Budapest, 1942. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

How This Parthenon Relief Was Torn Apart—Twice

South Metope IV is one of many sculptures from the ancient Greek temple whose fragments are scattered across the globe.

The Venetians struck the first blow. In 1687, amid the Great Turkish War, Venice’s forces rained a fusillade of cannonballs on the Ottoman-held Parthenon in Athens, Greece. The Turks had been using the Classical temple as a storage facility for their ammunition, believing it could withstand bombardment just as it had weathered history. Not so. The explosion demolished most of the Parthenon’s walls and columns, wrecking its architraves, triglyphs, and metopes.

After the blast, what remained of the Parthenon’s metopes, or relief-carved panels, were but shattered fragments. Some were picked up and reused as building material. Other parts were snatched by Western visitors eager for a piece of the temple. Thomas Bruce, Lord of Elgin, famously swung by to seize a trove of Parthenon marbles; Frenchman Louis-François-Sébastien Fauvel and Danish captain Moritz Hartmann, who was part of the Venetian fleet, also carried away their share of loot.

Amid this free-for-all, the metopes were scattered not just all over the Acropolis, but across the globe. Among them was South Metope IV, depicting a dramatic confrontation between a Centaur and a Lapith, that has been split apart for centuries.

19th-century engraving reconstructing the Parthenon in Athens at the time of Pericles.

When the Parthenon was completed in 432 B.C.E., it epitomized the height of Greek architecture—its colonnade, masonry, and magnificent frieze overseen by Phidias harmonizing in a grand tribute to the goddess Athena.

Spanning the temple’s entablature, the frieze held 92 metopes—28 facing the east and west, and 64 split evenly between the north and south sides. Each metope group, carved out of Pentellic marble, chronicles scenes from legendary clashes, often featuring two figures. The east, for example, retold the mythical clash between the Olympians and the Giants, while the north revisited the sack of Troy. The south side, meanwhile, detailed the fabled fight between the Lapiths, a Thessalian tribe, and the Centaurs who crashed the wedding feast of their king.

Metopes and reliefs on the west pediment of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece.

After facing calamities ranging from fire to vandalism by Christians, the metopes were finally toppled by the Venetians’ shells on September 26, 1687. In the early 19th century, South Metope IV joined some 14 others that wound up in the British Museum—but in a greatly reduced state. Where the panel once portrayed a Centaur raising a jug, ready to crash it onto a cowering Lapith vainly clutching a shield, the surviving artifact is missing both figures’ heads and part of their limbs.

The key to completing the metope, it turns out, rests in the collection of another institution: the National Museum of Denmark.

Back in 1687, army captain Hartmann snapped up the heads of a bearded man and a youth from a street vendor in Athens; he carried them home to Copenhagen where they ended up in the Royal Kunstkammer. Studies in the 1820s concluded that the heads were associated with South Metope IV. In the following decade, Denmark’s royal collection received yet another fragment linked to South Metope IV, this one shaped like a Centaur hoof.

Centaur head of South Metope IV from the Parthenon in Athens.

These heads add emotional heft to the metope. The bearded Centaur is carved with a steely gaze and his arm bent backward in preparation to strike; the young Lapith, in response, greets the incoming blow with a half-opened mouth and wide eyes. (The former relic is also covered in a mysterious brown stain that has long confounded scientists.)

And there are yet more parts to the metope. While the Danish Museum holds one of the Centaur’s hoofs, the figure’s left hind leg is all the way back in Athens, in the Acropolis Museum. South Metope IV, therefore, is “literally and metaphorically torn between London, Copenhagen, and Athens,” as George Vardas, secretary of the Australian Hellenic Council, wrote in Greek City Times—and it is not the only Parthenon sculpture to be so divided.

We have from the same figure, half of the body in Athens, half of the body in London,” said Dimitrios Pandermalis, the director of the Acropolis Museum, in 2009. “We have a body in London and a head in Athens. We have horses in London, and the tails of the horses are in Athens. It is a moral problem in art of divided monuments.”

Lapith head of South Metope IV from the Parthenon in Athens.

In 2015, the British Museum and the National Museum of Denmark collaborated on a digital reconstruction of South Metope IV, imagining how the work once appeared, complete with polychromy. But the day that the museums’ respective pieces might be physically reunited appears far off.

Both the Copenhagen and British institutions have spurned Greece’s continued appeals for the return of the Parthenon marbles. In 2023, the Danish museum’s director Rane Willerslev noted that its fragments “are of greater importance to the National Museum than if they were sent to Greece.” The U.K.’s drawn-out talks with Greece regarding the Parthenon relics, meanwhile, remain “ongoing,” according to the British Museum in 2024.

The Parthenon Gallery in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, Greece.

Perhaps the best place to see a form of the somewhat complete metope is in the Acropolis Museum, which houses a plaster cast of the South Metope IV. Installed in its Parthenon gallery, the replica affixes the figures’ heads to their bodies, leaving out their lost limbs but painting no less of an intense encounter. The museum’s aim is to eventually reunite the original elements of the Parthenon compositions. With South Metope IV, a left hind leg represents a first step.

By Min Chen.

#The Parthenon#How This Parthenon Relief Was Torn Apart—Twice#Athens Greece#marble#marble sculptures#ancient greek temple#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#greek art#ancient art#long post#long reads

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

A pair of Continental polished cast iron architectural single column Ventilo radiators

Probably Belgium

the entablature tops above six rectangular pilaster columns flanked by crowed putto caryatid draped terms, the figures with crossed arms wearing helmets, the tapering foliate lower sections with monopodium lions paw feet, all raised on corresponding rectangular plinth bases.

Bonhams

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

The caryatid is a term that in architecture refers to a female sculpture, with the appearance of a column, which holds an entablature above its head. One of the most typical examples is the tribune of the caryatids in the Erechtheion. Athens.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

once the first stage of a roman senator's life cycle is nearly complete, the larvae (colloquially known as 'tribunes') search for safe places to pupate. some burrow underground, while others hang suspended from the entablature of various temples near the centre of the city or choose an at-home pupation. they remain in their chrysalis forms for upwards of two months, during which time the senators' digestive enzymes dissolve their bodies from the inside. once they have remoulded, the senators emerge from their cocoons as fully-formed adults.

34 notes

·

View notes