#emperor tai’an

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Grand Eunuch’s first appearance

#xiao se#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#jin xuan#zhuo qing#the blood of youth#少年歌行#shao nian ge xing#dashing youth#少年白马醉春风#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#my gifs

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Population: 5,635,000

The submitter commented, “the famous taishan (tai mountain) is located there, but no foreigners seem to ever go there. nevertheless, taishan is a important historical site, the emperor used to climb to the top each year to pray for good fortune, and many people still climb it today. wish more people knew about it, the city is nice and the mountain is cool (although it takes around 6 hours to climb)”

1 note

·

View note

Text

When it comes to surviving multiple emperors, there are a few important traits to have:

1. Lack of loyalty

Loyalty leads to willingness to keep an emperor alive and even dying for him. Dying, of course, goes against the goal of survival. The Emperor being alive for a long time goes against the goal of there being multiple emperors.

2. Cunning

Being cunning is essential to the eunuch’s survival. He needs to know what words to say and when not to say them. He needs to know how to make himself valuable. He needs to know when things aren’t going his way and who to turn to when that happens.

3. Ambition

The eunuch needs to want things. To hide away wealth, to make connections, to be respected. He needs to have the determination to plot, to do whatever footwork necessary to get what he wants. This may make survival more difficult, but it’s priceless in stirring things up for the multiple emperors objective.

So, applying this to some of my favorite eunuchs…

Gao Zhan: smart, but too loyal and not ambitious. He’ll serve his emperors as long as he lives, and he’ll do it well. Too well for there to be much turnover on the throne.

Jin Xuan: cunning and ambitious, but, complicated as his loyalties are, there is only one emperor that Emperor Mingde will allow him to serve—and it’s him.

Zhuo Qing: ambitious and cunning, but only plots against Emperor Tai’an in small ways while taking large risks for him—like facing off against the Immortal Li Changsheng. After Emperor Tai’an’s death, Zhuo Qing is only thirty-six years old and has nothing holding him back but the mausoleum he’s forced to guard. He definitely has potential, but things…didn’t work out.

Finally, we have Jin Yan. He’s cunning, he’s ruthless, he’s greedy. He lies and he charms. He has a martial brother who doesn’t even share the same shifu but is still willing to die for him. He does a rebellion’s worth of footwork just to get what he wants. Failure though it was, it worsened the emperor’s mental and physical condition, but instead of Emperor Mingde punishing him, he lets him live happily ever after with his loyal shixiong. Even when Jin Yan loses, he wins.

They foil plots against them for breakfast, receive a bit of light bribery for lunch, and finish off the day with widescale manipulation.

These characters may nominally be servants, but they hold all the power in the Palace and are going to live long, long lives.

Write-ins, propaganda, and images are welcome!

#Jin Yan truly has what it takes to stir things up and not die by the end#he could speedrun at least four emperors if he knew there was a competition#jin yan#the blood of youth#eunuchs#propaganda#poll

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tongdian: The Grand Teacher (

[From Tongdian 20. Small text sections moved to the end as lettered end notes]

The Grand Teacher太師

The Grand Teacher is an ancient office. In the time of Zhou of Yin, the Son of Ji箕子 was it.

In the time of King Wu of Zhou there was the Grand Noble太公, in the time of King Cheng there was the Noble of Zhou 周公, both were Grand Teachers. When the Noble of Zhou passed away, the Noble of Bi畢公 replaced him.

Qin and the beginning of Han both were without it. Arriving at Emperor Ping’s 1st Year of Yuanshi [1 AD], they set it up, using Kong Guang to occupy it with golden seal and purple ribbon, his rank was above of Grand Tutor. The Grand Guardian was secondary to Grand Tutor[a]. During Han’s Eastern Capital, it was again abolished. At the beginning of Emperor Xian, Dong Zhuo became Grand Teacher. When Zhuo was executed, it was again abolished.

In the age of Wei they did not set it up.

At the beginning of Jin, when they set up the Three High Nobles三上公, since Emperor Jing’s taboo was shi師 they set up a Grand Steward太宰 and used it to replace the name of Grand Teacher[b], its rank added to the Three Ministers[c].

Later Wei, Northern Qi, Later Zhou, Sui and Great Tang all had it[d].

[a]Kong Guang was Grand Teacher and Wang Mang was Grand Tutor. Guang regularly claimed illness, and did not dare to be equal with Mang. The Empress Dowager decreed: “Order the Grand Teacher to be not at court, and bestow a numinous long-life cane. The Prefect of the Yellow Gates黃門令 is to, inside of the Grand Teacher’s department where he sits, set up a table. The Grand Teacher enters inside of the department employing the cane, and bestowed as food the seventeen things.”The “seventeen things” was food prepared from seventeen kinds of things. “Numinous long-life” is a name for wood.

[b]The Book of Jin says: In Emperor Hui’s 1st Year of Tai’an [302 AD], “used the King of Qi, Jiong, as Grand Teacher”. Must at the time have been an error in compiling the accounts.

[c]When Li Xiong of Shu usurped the title, at the time Fan Changsheng drove from Xishan in a plain carriage to go to Chengdu. Xiong designated Changsheng as Grand Teacher of Heaven and Earth天地太師, and ennobled him Captain of Xishan.

[d]During the Tianbao era [742 – 756] and earlier, only used its office to present to Zhongni, and to Zhangsun Zhen, Wu Shiyue武士彠, Dou Yi, Wei Xuanzhen, Zhang Shuo, and Pei Guangting, and that is all. 彠 is pronounced you憂+ fu縛

[Baxter & Sagart: 彠: not listed. yōu憂: (‘- + -juw A). fù縛: (b- + -jak D).

From there we should get (‘- + -jak D) which results in modern yuē.]

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taishan (1)

I recently had occasion to learn the Chinese vocabulary of noise, inconvenience, and complaint. An apartment below us in our building is undergoing an ambitious and extremely thorough renovation, resulting in deafening noise levels. Thank goodness, I have noise-cancelling headphones, but sometimes even Stevie Ray Vaughn’s amplified electric guitar cannot drown out the jack hammer. At those times, I would storm to the management office (guǎnlǐ chù) and complain (tóusù) that the noise (chǎo) of the demolition (chāi fángzi) had gotten too bad (tài bú hǎo le), especially the drilling (zuǎn kǒng). And I would insist that they tell me until when (dào shénme shíjiān) this madness (#@*!) was supposed go on, so I could come up with a plan to stay sane. After I’ve had my say, they would usually tell me something about a fast approaching end of the project, but nothing would change.

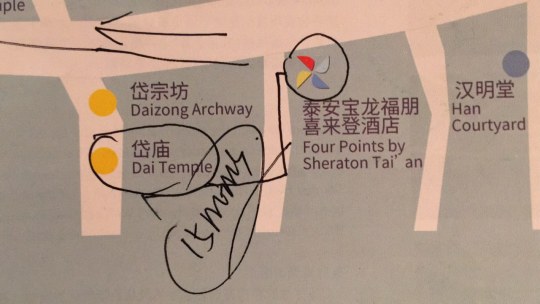

So, one day when it got particularly annoying, I decided to take a hike—literally. To plot my escape, I pored over a map of China, crossing it with my bucket list of places to go hiking. I quickly narrowed it down to one location which, though more than 800 km away (roughly the distance from Switzerland to Holland), was located along the high-speed train line to Beijing, which means that traveling would be less than four hours. Soon, I held the ticket to Tai’an in my hands and busied myself with booking accommodations.

The hiking destination, Taishan, is one of the five holy mountains of China. Some consider it to be the most important of the five mountains. My sense is that this judgment is influenced more by worldly than spiritual considerations. Indeed, being located relatively near Beijing, the place was favored by frequent visits from the emperors. This, in turn, means that the mountain received a rather lavish amount of resources for development. For instance, by the standards of hiking trails, the path they beat up to the Heavenly Gate on the top of the mountain looks rather like a superhighway--a multilane stairway to heaven!

This was not a point of attraction for me, but I figured that there might be alternative routes to go.

But before I get to the hiking portion of the report, I want to clarify that this was my first solo trip in China. In a sense, it was the final exam to see if I was ready to graduate from my “survivor Chinese” level. But early on in my stay at Tai’an, I had reason to suspect misunderstandings because the prices I heard seemed to be wrong, making me wonder if I had my numbers all mixed up. But then I realized that the dollar (or rather kuai/yuan) simply stretched much farther here than in Shanghai. For instance, my large, well-appointed room at the Sheraton set me back all of $73.

The bathroom even fancied a large picture window with a mountain view next to the tub. Another example: a fancy retractable aluminum hiking pole with spring shocks cost just 20 kuai (or $3). In the US, you would not even get the hand strap on said hiking pole for that amount. In many regards, Shanghai is as expensive—or even more expensive—than major Western cities, but Tai’an is in a different league. Here, I noticed a certain financial insouciance that would be unthinkable in places like Shanghai: One lady who wanted to sell me a tourist map told me it was 8 kuai ($1.30), but when I wasn’t bargaining, she voluntarily lowered the prince to 5 kuai. I ended up giving her 6 to play her game of defeating each others’ expectations. For a moment I felt like I was in a Monty Python scene.

People here also don’t charge Westerners more than they do locals. By contrast, in Shanghai even native-born Chinese like my wife (who are considered as “returnees”) are charged more than died-in-the-wool Shanghainese at the fish market and other bargain-intensive places. But along the path up to Taishan, I bought a bag of local herb tea for 5 kuai, and as I walked away, I saw the sign board in Chinese characters that did indeed list the price as 5 kuai per baggy.

Finally, to top it off, when I stepped on a bus for a few stops but did not have the 2 kuai exact change required for the fare, an elderly lady nonchalantly handed me two 1-kuai pieces. Since I didn’t want to be remembered in this town as another dirt-poor Westerner spooning off the locals, I insisted that she keep my 5 kuai bill, which she did, but only reluctantly. In any case, this aspect made me feel perfectly comfortable as the sole Westerner in this place.

I’m not kidding, I didn’t see another Westerner here, and the scarcity of my kind showed in the behavior of the locals: I lost count of how many times I had my picture taken with enthusiastic Chinese who just wanted to be seen with a wàiguó rén (foreigner).

What this meant to them was not entirely clear to me…maybe they considered me exotic. Or I appeared to them as a kind of walking status symbol. This sort of treatment (which scholars would call “reverse othering”) didn’t bother me at all since I obviously derived not disadvantage from it. On the contrary, I reaped a tangible benefit from the attention I was getting: I’m not saying that I was feed like an animal at a petting zoo, but the locals did show a strong proclivity to hand me edibles for free. It started on the way up when a fellow hiker, who kept pace with me, spontaneously offered me half of his freshly purchased cucumber. For a moment I hesitated because of food safety concerns but then I bit into it, and the cold bursting freshness was a sheer delight to my parched mouth.

Later on, a group of women picnicking right on the steps of the stair path held out their bag of freshly baked sponge cake to me and let me grab a couple. Another guy I chatted with for about half an hour using my stumbling Chinese rewarded me for my effort with a whole pack of cookies. During our conversation, he told me, he’d spotted me five hours earlier down at the middle point of the hike. That’s how much I obviously stuck out there.

But as good as folks here are in the friendly-overtures department, giving directions is not their forte. The concierge at the Tai’an Sheraton usefully told me that the Dai Temple—the town’s main attraction, beside the mountain—was a mere 15 minutes down the road. I naturally thought that most people’s 15 minutes was my 10. But the “map” the concierge handed me turned out to be equivalent to an imaginative child’s drawing: It bore only a slight resemblance to the actual lay of the land.

It took me almost one hour to reach the Dai Temple, for it was over two miles away, and I took a few wrong turns. I was again surprised the next day when at the conclusion of my hike I ended up at the foot of the mountain looking for local transportation. I asked some people at a store about the location of the bus stop to return to Tai’an, but they looked at me as if I were asking where the launch pad to the moon was. I know the word for bus stop (chē zhàn) and the question word “where” (zài nǎlǐ), so that was not the problem. Anyway, they could not help me, but when I kept walking down the road, I spotted the bus stop merely two blocks further. Fortunately, the little confusion did not prevent me from being back at the Sheraton in time to order a taxi to take me to the train station. At least the taxi driver had a decent sense of orientation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#zhuo qing#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#dashing youth#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#少年白马醉春风#my gifs

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#zhuo qing#dashing youth#少年白马醉春风#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#leon gifs dashing youth#my gifs

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Is there anything else His Majesty needs?”

#zhuo qing#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#dashing youth#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#少年白马醉春风#fanart#ship art#shipping#my art

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yan Su & Jiang Kai as Zhuo Qing & Xiao Zhongjing in Dashing Youth 少年白马醉春风 (2024) and as Yang Su & Yuwen Hu in Queen Dugu 独孤皇后 (2019)

#yan su#jiang kai#zhuo qing#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#yang su#yuwen hu#dashing youth#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#少年白马醉春风#queen dugu#独孤皇后#my gifs

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Their dynamic is so intriguing already

#zhuo qing#emperor tai’an#xiao zhongjing#dashing youth#少年白马醉春风#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#leon gifs dashing youth#my gifs

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emperor Tai’an highlights in Dashing Youth episode 30

#he’s shaping up to be such a fun and fascinating character#amazing performance#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#zhuo qing#dashing youth#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#少年白马醉春风#my gifs#leon gifs dashing youth

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A game between an emperor and his eunuch

#I’m screaming#this is everything I wanted#Zhuo Qing finally gets to sit across from him#they’re playing my favorite game#Xiao Zhongjing is smirking#so much#my heart is melting#the way he looks at him#going insane#aaaaah#zhuo qing#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#dashing youth#少年白马醉春风#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#leon gifs dashing youth#my gifs

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emperor Tai’an in Dashing Youth episode 16

#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#dashing youth#少年白马醉春风#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#leon gifs dashing youth#my gifs

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“As His Majesty wishes.”

#emperor tai’an#xiao zhongjing#zhuo qing#dashing youth#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#少年白马醉春风#fanart#shipping#ship art#my art

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tea with Emperor Tai’an 🫖

Bonus smirk:

#going absolutely insane over them#again#the way Zhuo Qing immediately goes from cowering to helping him with the teapot#even when he’s afraid and defeated his first instinct is to serve his emperor#aaaaah#and the fond smile Xiao Zhongjing has while Zhuo Qing is pouring the tea#my heart#💜#zhuo qing#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#the young brewmaster's adventure#少年白马醉春风#shao nian bai ma zui chun feng#my gifs

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Even the man who nailed his older brother to death on the city walls needs to get nailed sometimes.

#xiao zhongjing#emperor tai’an#zhuo qing#dashing youth#少年白马醉春风#art#ship art#fanart#my art#small fandom summer

3 notes

·

View notes