#elizabethan garters

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

you know it's a serious research day when

#good omens#shakespeare#hard times#costume design#elizabethan clothing#yep research#elizabethan garters

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week I posted the final part of my Shakespearean-era fic:

I fully admit I went overboard on the footnotes, references, and dirty Elizabethan poetry, and I would DO IT AGAIN.

omg it’s FAN FICTION FRIDAY

Reblog and promote a fic of yours <3

#didn't go too far with the smut tho#the smut looks A-OK to me!#fan fiction friday#my fic#good omens fanfiction#aziraphale and crowley#aziracrow#twelfth night#shakespearean#elizabethan garters#yellow stockings#not canon compliant#not AU either tho#ineffable husbands

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Burton Constable Hall

Hi guys!!

I'm sharing Burton Constable Hall. This is the 19th building for my English Collection.

I decorated most of the house ground floor, for reference.

History of the house: Burton Constable Hall is a large Elizabethan country house in England, with 18th- and 19th-century interiors.

Despite its apparent uniformity of style, Burton Constable has a long and complicated building history. The lower part of the north tower, built from limestone, is the oldest part of the house to survive and dates to the 12th century, when a medieval pele tower served to protect the village of Burton Constable from the time of the reign of King Stephen. In the late 15th century a new brick manor house was built at Burton Constable, eventually replacing Halsham as the family's principal seat. In the 1560s Sir John Constable embarked on the building of the Elizabethan prodigy house that stands today. This incorporated remains of the earlier manor house along with the addition of the new range containing a Great Hall, which rose the full height of the building and was top-lit by a lantern, along with a Parlour, Chambers and South Wing.

By the 18th century, the Great Hall must have seemed old fashioned, and a surviving design of c. 1730 suggests that Cuthbert Constable intended to completely remodel the interior. However, it appears that remodelling was not undertaken until the 1760s when his son William Constable commissioned a number of architects for designs. These included John Carr, Timothy Lightoler and Capability Brown. The decorative plasterwork was executed by James Henderson of York. At this time, Constable also acquired the plaster figures of Demosthenes and Hercules with Cerberus, and plaster busts of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus and the Greek poet Sappho, from the sculptor John Cheere. Above the fireplace is a carving of oak boughs and garlands of laurel leaves, crowned by the Garter Star, surrounding the armorial shield of the Constable family in scagliola by Domenico Bartoli.

The dining room was substantially remodelled by William Constable in the 1760s, who commissioned designs from Robert Adam, Thomas Atkinson, and Timothy Lightoler (who won the commission). The ceiling draws on contemporary interest in the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, with plasterwork by Giuseppe Cortese. The overmantel plaque of Bacchus and Ariadne riding on a panther was modelled on famous antique cameos illustrated in Pierres Antiques Gravées, published 1724 by Philip, Baron von Stosch and Bernard Picart. This room was again redecorated in the 19th century.

Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burton_Constable_Hall

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This house fits a 50x50 lot.

I only decorated some of the important rooms. All the rest of the house is up to your taste to decor.

Hope you like it.

You will need the usual CC I use:

all Felixandre cc

all The Jim

SYB

Anachrosims

Regal Sims

King Falcon railing

The Golden Sanctuary

Cliffou

Dndr recolors

Harrie cc

Tuds

Lili's palace cc

Please enjoy, comment if you like the house and share pictures of your game!

Follow me on IG: https://www.instagram.com/sims4palaces/

@sims4palaces

Download: https://www.patreon.com/posts/112319879

Public: 21/10/2024

#sims 4 architecture#sims 4 build#sims4#sims 4 screenshots#sims4building#sims 4 historical#sims4play#sims4palace#sims 4 royalty#ts4#ts4 download#ts4 simblr#ts4 gameplay#ts4 screenshots#sims 4#the sims 4#sims#simblr#sims 4 gameplay#my sims#the sims#sims build#sims 4 simblr

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's Talk Costuming: It'd take a miracle to get anyone to see Hamlet

Huzzah huzzah, we return to the Renaissance for part two! You can click here to see my analysis of Aziraphale's costume through the lens of Elizabethan sumptuary laws, aka our angel is a bit of a fop and we love him for it. As a reminder (or if you don't feel like reading the other at all) we're towards the end of the Elizabethan period, around 1599-1601, and England is protestant now!

Guys I absolutely love these costumes. Chronologically, this is the first time we get to see Crowley being stylish. I mean you could count Bildaddy as being... something, but I'm not sure I'd I would not consider it to be vogue or on trend. It is, as I pointed out for Az, highly indicative of his building an identity on and appreciation for Earth.

Silhouette-wise, he's pretty on the nose, and he continues to follow the trends to some degree for many centuries up until around Y2K. He's learning to blend in with the humans and properly enjoy what they bring to the table: clothes, wine, plays, et cetera.

He's not particularly ostentatious, especially standing next to Aziraphale, but his costume speaks more to a quiet luxury. Black, for example, was a very expensive color to dye things, and the buttons and leather accents betray some level of fashion sense.

( The Royal Progress Of Queen Elizabeth I, 1740)

I think one of my favorite things about this costume is the way they took all these elements of the period and then just had them... in black. Even the little ribbon garters on the stockings! It's one of his rare outfits that's entirely and exclusively black and I love that for him. There's a variety of materials, leather detailing and buttons for example, giving the garments a lot of texture and detail nonetheless (and keeping him from looking like a black void on camera). From the first season, this is one of my favorite fits.

According to this article, these costumes are actually borrowed from the Globe's costume archives! Which makes a lot of sense looking at them, they're very elaborate and theatrical, plus I just have a soft spot for costume collections and things that have been worn for multiple productions over time and the way it ties theatre and people and artsists together. Plus, look at those shoes!!!

As per usual, the two costumes compliment each other beautifully. Their historic costumes highlight their narrative foiling of each other in a slightly different way than their modern ones do. Most notably here, at the Bastille, and in Edinburgh, their clothing has a lot to say, were they human, about both social and economic class. We see Crowley demonstrating a significantly higher level of class awareness than Aziraphale, both in their dialogue (virtues of poverty) and in their dress (Aziraphale showing up to revolutionary era Paris in full aristocratic style). Here, in the Elizabethan era, Crowley blends in much better than his angelic counterpart (see again my analysis of Aziraphale's costume in this scene).They really don't look, to your average human unaware, like they belong together. If they weren't staring at each other with puppy dog eyes, it might would be rather believable that they're not friends.

(Portrait of Sir Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury, circa 1613-1614)

I also found this incredibly slutty portrait while I was researching for this post, which bears similarities to Aziraphale's dress, so I figured y'all might enjoy seeing it.

For further reading: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1577/clothes-in-the-elizabethan-era/

Please note that I did write all of this intermittently over several days, and though I've done my best to proofread I'm rather tired so if it's not perfect just look the other way

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

What then was Hatton’s position within the small group of men who formed Elizabeth’s key policy advisors? The current orthodoxy, as we have seen, is that the leading ministers of the 1570s and 1580s were largely united in pursuing the same goals, in particular the promotion of Protestantism. Superficially, this is fair: they clearly did work together with little obvious animosity for long periods. Yet if, as this book argues, Hatton’s attitudes, in religion at least, differed significantly from his colleagues, did this lead to dissent or acrimony between them, as comparable situations did in the 1560s or the 1590s? Were their relations genuinely amicable, or merely politely cautious? In general, there is very little evidence of active hostility, something helped both by Hatton’s genial personality and by ministers’ awareness that the Queen disliked discord. Hatton participated in the solidarity among senior ministers which marked mid-Elizabethan politics. He did many favours for them. His early encounters with Burghley, for example, were very respectful, with each taking advantage of the other’s influence with the Queen and the administrative machinery, respectively. They continued to exchange cordial letters, discussing policy and building projects and wearily complaining about the burdens of office and ‘our troblesome courtinge life’, as Hatton once put it. There are similar signs of regard with Leicester. Hatton gave Leicester two fine suits of armour, one of which Leicester left back to him. Leicester also made Hatton an overseer of his will, and left him ‘one of my greatest basons and ewers gilte with my best George and garter not doubting but he shall shortly enjoye the wearing of it and one of his Armors he gave me’. Quite likely Leicester hoped that Hatton would help to protect his widow, whom the Queen notoriously loathed. More persuasive are several very cordial, sympathetic letters between them. Hatton wrote a genuinely sympathetic and poignant letter of comfort on the death of Leicester’s son, Lord Denbigh, in 1584.

Neil Younger, Religion and politics in Elizabethan England: The life of Sir Christopher Hatton

#Neil Younger#non-fiction#Christopher Hatton#William Cecil#Robert Dudley#Elizabeth's council#but I must warn you this book highlights not cooperation and cordiality but disagreements between them#it's Hatton vs trio Burghley Leicester and Walsingham in this book

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

decided to go with the nt twelfth night since it's fun and complements ayli and i don't have the capacity for lear yet

i watched half of this during the lockdown?

i don't know why i never finished it since i've got a crush on everyone

even though it uses the same plot device 12th night is so much gayer than ayli

possibly bc the scenes of extended wooing are between olivia and cesario/viola whereas in ayli they're between rosalind/ganymede and orlando

i love andrew aguecheek so much he's too pure

never over the nt's sets like holy shit

orsino is just so hard not to make a dick the orsino here is trying so hard but it's such an uphill battle against that text

greig has no right to get away with half the choices she makes but somehow she just does

also here for feste as i remember them, which is goofy and witty yet but also mean

sebastian and feste blindly wandering into a gay bar where drag queen is singing "to be or not to be" feels 100% in character for this production

there's just like a lot to unpack with the malvolio gender bending here

i forgot the sudden nose dive this play does into making all its characters question their sanity

they are very much playing this as sebastian is gay but nothing makes sense and olivia is kind and safe after everything he's been through that he's like why not i'll marry you

which already breaks my heart for antonio

(i am been savoring and slowly working my way through emma smith's lectures on shx's plays and the question she tackles for 12th night is why does antonio exist and functionally makes the argument that he has no structural purpose in the plot and therefore his existence is to make gender and sexuality issues more ambiguous...she also brings up some really interesting lenses to think about the text re: how gender and sexuality would have been thought of and perceived differently by an elizabethan audience)

12th night also reads as gayer i think because no one retains control over the reality confusion and gender chaos at the end

in ayli rosalind is the ring leader and orchestrates everyone into their happy endings and maintains control over the narrative even down to the epilogue with the audience

in 12th night literally no one has any clue what's going least of all sebastian and viola/cesario

and the meeting of the twins grounds it all with its heart wrenching -ness

and then they really went for the pathos with malvolia

which honestly feels like the right choice here

okay the twins swapping at then end was also inspired

i had to look it up bc it did not occur to me until the "to be or not to be" song that not all the songs were from the text

which makes me wonder where the text malvolia sings in the garters comes from?

but that ending song is the original one and it is quite melancholy

#shx really was like here's a show for the gays but good luck tetris-ing it into a proper happy end#who am i kidding all the shx plays are for the gays#they're ours hands off

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1/26/2024-1/30/2024: Twelfth Night

Hey, it's Twelfth Night! The play that insists that cross-gartering is HILARIOUS. That's certainly one thing that benefits from watching, as opposed to reading. Although if the production isn't set firmly in Elizabethan times, they probably have to strain a bit to justify regular garters, let alone crossing them up.

Here's what I find interesting about this (very funny) play. It combines three different comedic techniques that Shakespeare had previously employed one at a time.

The Comedy of Errors is a play where the comedy comes from people confusing twins for each other. As You Like It derives its comedy from cross-dressing. The Merry Wives of Windor is about gulling.

(Sidebar: "Gulling" is "tricking somebody into doing something dumb." That someone is a "gull". It's all over The Merry Wives of Windsor, and also the Ben Jonson play Every Man in His Humour, to which Merry Wives bears a lot of similarities. Shakespeare was an actor in Every Man in His Humour, so I think there's a straight line here)

And in Twelfth Night, all three happen. In the duel scene, all three happen at the same time. A cross-dressed character is gulled into a duel, and then her twin swaps in to cause confusion. I think it's really interesting to view Twelfth Night as an evolution of these three other comedic styles.

Some other comedies (Love's Labour's Lost, The Taming of the Shrew, and Much Ado About Nothing) derive their comedy from two characters battling each other with escalating verbal pyrotechnics in multiple scenes. There's obviously some of that in any Shakespeare play, but they feel like their own subgenre.

And speaking of genres, I'm going to have some things to say about the very concept in five days, I bet.

Anyway, Twelfth Night is great.

Next up: Troilus and Cressida

0 notes

Text

Good morrow and well met, for we have scraped together 8 of the dirtiest bawdy (bardy) moments from ol' Shakey-pants' work.

Don't act so surprised. It's always been about the dick jokes, y'all. Do you know us but at all?

So, adjust your ruff, pull up your cross-gartered stockings, and let's get the fuck into it.

1. Much Ado About Nothing

Right from the title we’re dealing in double entendres. ‘Nothing’ is Elizabethan slang for vagina so it basically means: “a lot of fuss about pussy”. Cool.

Then almost immediately, our first introduction to one of the protagonists alludes to him being a walking venereal disease: “If he have caught the Benedick, it will cost him a thousand pound ere a' be cured.”

In return, Benedick swears he will never “hang my bugle in an invisible baldrick” and on it goes for 5 acts. Even BeneDICK’s eventual declaration of love includes a sex pun. “I will live in thy heart, die (orgasm) in thy lap, and be buried in your eyes.” Stay classy, guys.

2. Romeo & Juliet

Just your regular tween romance in which thirteen-year-old Juliet monologues repeatedly about how much she wants to get Ro-Ro into her bed. Even the classic ‘a rose by any other name’ speech includes the line: “nor hand, nor foot, nor arm, nor any other part belonging to a man” fnar fnar.

Oh, and she also dies (slang for orgasm) asking for his ‘happy dagger’ to rust inside her ‘sheath’. Yeah yeah, it’s a tragedy, but it’s also sex ‘n’ death right to the end.

3. Twelfth Night

Malvolio is the king of (accidental?) debauchery. While reading a (forged) letter from the lady he fancies, he declares: “By my life, this is my lady’s hand. These be her very C’s, her U’s and (N) her T’s, and thus makes she her great P’s.” Yes, that is how you spell **** and we’ll let you figure out the P bit.

He’s also responsible for the most misquoted line by wannabe motivational speakers everywhere: “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness THRUST upon ‘em.”

Yes, he’s talking about his dick.

4. Hamlet

To be or not to be whatever, but just imagine trying to sneak ‘c*ntry matters’ past the censors today:

HAMLET: Lady, shall I lie in your lap? OPHELIA: No, my lord. HAMLET: I mean, my head upon your lap. OPHELIA: Ay, my lord. HAMLET: Do you think I mean country matters? OPHELIA: I think nothing, my lord. HAMLET: That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs

Reminder that ‘nothing’ also means vagina. That’s a double whammy in the space of 7 lines. Kudos, sir.

5. Sonnet 20

Elizabethans loved a nice bit of androgyny, and never more so in this poem whereby Shakey talks in detail about how his (male) patron is soooo pretty and delicate and feminine AF and he’s super totally into that even though nature added ‘one thing to my purpose nothing’ (psst he’s talking about the guy’s cock) and ‘prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure’ (still talking about cock) but that’s ok cos all the laydeez will ‘use’ his ‘treasure’ (cock).

Mm hmm.

Cue all the old man scholars arguing for several hundred years that there was absolutely nothing gay about any of this lol bless.

6. The Taming of the Shrew

An otherwise irredeemable play contains this arse-licking zinger:

PETRUCHIO: Who knows not where a wasp does wear his sting? In his tail. KATHARINA: In his tongue. PETRUCHIO: Whose tongue? KATHARINA: Yours, if you talk of tails: and so farewell. PETRUCHIO: What, with my tongue in your tail?

No further comments, your honour.

7. Henry V

Ok, buckle in for some Franglaise as the French Princess Catherine practices her English in preparation for marrying Henry, mispronouncing various body parts in a hilarious display of casual xenophobia. But the tables turn beautifully and profanely when she asks her maid the English word for ‘robe’ and is told ‘coun’ (gown) which sounds a lot like… uh… See you next Tuesday.

Yep. Shakespeare really got the future queen of England to say c*nt live on stage. Bravo.

8. Titus Andronicus

Aaaaand possibly the first recorded ye olde yo mama joke:

CHIRON: Thou hast undone our mother. AARON: Villain! I hath done thy mother!

Boom boom. Because he had sex wtih her. It’s about sex. It’s a sex joke. Okay cool. Bye.

#shakespeare#dick jokes#much ado about nothing#romeo & juliet#twelfth night#hamlet#sonnet 20#the taming of the shrew#henry V#titus andronicus

93 notes

·

View notes

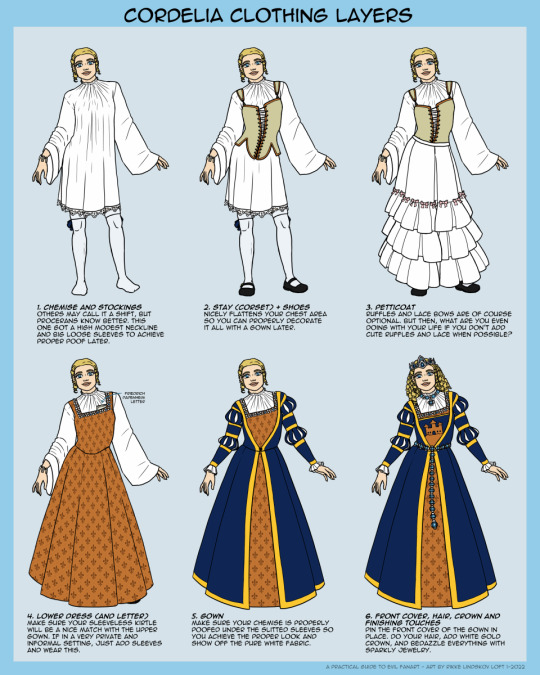

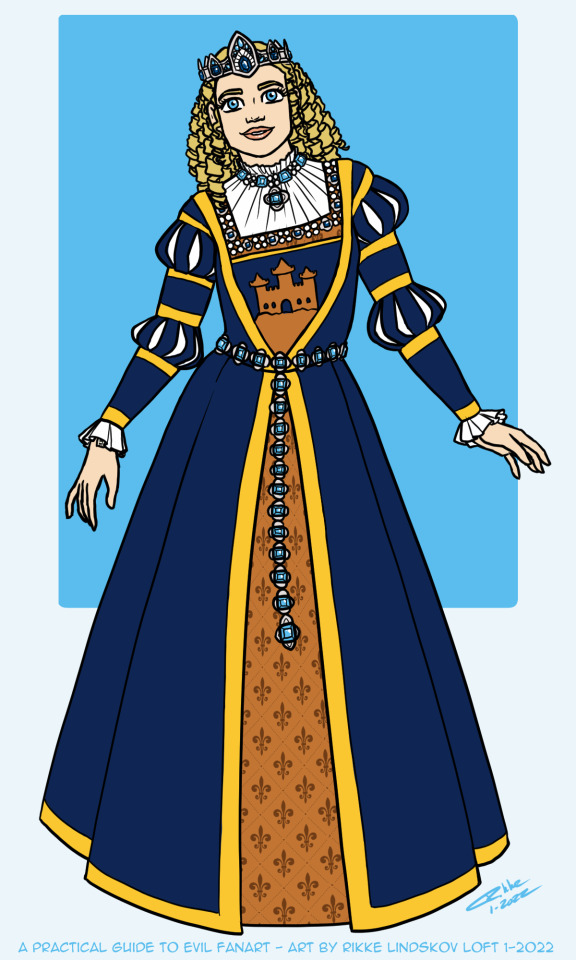

Photo

Cordelia clothing layers. (A practical Guide to Evil fanart)

Honestly, this one is all for me, and I geeked out. So, first of all, this is fantasy. I combined a lot of different historical inspirations from approximately the same century, to get the look I wanted.

This is roughly based on elements from Saxon Cranach dresses from between 1510 and 1540, as well as some Tudor and Elizabethan inspirations taken from around 1530 to 1580. The stay in particular is from the later part of the 16th century. Seeing how we know from Hakram’s excellent reading choices Procerans uses corsets – but everything else about them scream Renaissance inspiration – I figured we’d be talking early stays, that still are well within the Renaissance setting. Rather than much later Victorian corsets.

The ruffled petticoat might actually be the biggest historical deviation away from the general time period used for inspiration. They had petticoats around that century, but not with the ruffles. It just seemed so very, very Proceran. So yeah, one of biggest fantasy part in this due to being very out of time: The fluffy ruffled petticoat! Totally on par with the rest of Guide where one of the most modern parts also is the lace panties. ;)

More geeking out beneath the cut

1. Chemise and stockings. The stockings would be made from very finely knitted silk. Much more comfortable than is you sew stockings from fabric. The go above the knees and are fastened with lace garters.

Not pointed out on the image is the ratling tooth bracelet given to Cordelia by Friedrich Papenheim when she was quite young. In fact, she was so young it probably is a bit too small for her wrist now. Digging into it beneath her fancy sleeves.

2. Stays or corsets was used for quite a few centuries with very different goals. The early stays actually was not trying to give you a sexy hourglass figure. Rather the opposite, really. They worked to flatted out your chest into an – at the time extremely fashionable - cone shape. Body ideals change a lot in fashion…

3. I took a vote on Discord if Cordelia should be in white or blue. 3 voted for white. 13 for blue. And a couple of wonderfully mad souls started to argue for pastel pink to match Cat’s soon to be pastel fashion choices. These pink bows are for you lot. They may be hidden, but they’re there.

4. Lower dress and letter. Well, technically the letter from Friedrich Papenheim goes between the stay and the lower dress (called a kirtle). I figured it’d be much safer between these two pretty even and stiff layers, than if it went under the stay. Not sure what Cordelia is going to do now that she has two letters that are extremely near and dear to her. Double up on letters worn over her heart? Also, honestly Cordelia, you’re a weird and non-fashionable item short from Friedrich to form a proper rule of three.

5. Gown: If you look very closely, the bracelet is still just visible from beneath a sleeve.

6. Finishing touches: So yeah, the front part of the gown being pinned in place with needles is not something I’m making up. Someone not familiar with this style of fashion is in for a potentially pointy surprise if making a successful pass at a Proceran noble lady.

#a practical guide to evil#pgte#cordelia hasenbach#fanart#crown#fashion design#clothing design#artists on tumblr#gwennafran art

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is the plot of the merry wives of windsor?

The play is nominally set in the early 15th century, during the same period as the Henry IV plays featuring Falstaff, but there is only one brief reference to this period, a line in which the character Fenton is said to have been one of Prince Hal's rowdy friends (he "kept company with the wild prince and Poins"). In all other respects, the play implies a contemporary setting of the Elizabethan era, c. 1600.

Falstaff arrives in Windsor very short on money. He decides that, to obtain financial advantage, he will court two wealthy married women, Mistress Ford and Mistress Page. Falstaff decides to send the women identical love letters and asks his servants – Pistol and Nym – to deliver them to the wives. When they refuse, Falstaff sacks them, and, in revenge, the men tell the husbands Ford and Page of Falstaff's intentions. Page is not concerned, but the jealous Ford persuades the Host of the Garter Inn to introduce him to Falstaff as a 'Master Brook' so that he can find out Falstaff's plans.

Meanwhile, three different men are trying to win the hand of Page's daughter, Anne Page. Mistress Page would like her daughter to marry Doctor Caius, a French physician, whereas the girl's father would like her to marry Master Slender. Anne herself is in love with Master Fenton, but Page had previously rejected Fenton as a suitor due to his having squandered his considerable fortune on high-class living. Hugh Evans, a Welsh parson, tries to enlist the help of Mistress Quickly (servant to Doctor Caius) in wooing Anne for Slender, but the doctor discovers this and challenges Evans to a duel. The Host of the Garter Inn prevents this duel by telling each man a different meeting place, causing much amusement for himself, Justice Shallow, Page and others. Evans and Caius decide to work together to be revenged on the Host.

When the women receive the letters, each goes to tell the other, and they quickly find that the letters are almost identical. The "merry wives" are not interested in the ageing, overweight Falstaff as a suitor; however, for the sake of their own amusement and to gain revenge for his indecent assumptions towards them both, they pretend to respond to his advances.

This all results in great embarrassment for Falstaff. Mr. Ford poses as 'Mr. Brook' and says he is in love with Mistress Ford but cannot woo her as she is too virtuous. He offers to pay Falstaff to court her, saying that once she has lost her honour he will be able to tempt her himself. Falstaff cannot believe his luck, and tells 'Brook' he has already arranged to meet Mistress Ford while her husband is out. Falstaff leaves to keep his appointment and Ford soliloquizes that he is right to suspect his wife and that the trusting Page is a fool.

When Falstaff arrives to meet Mistress Ford, the merry wives trick him into hiding in a laundry basket ("buck basket") full of filthy, smelly clothes awaiting laundering. When the jealous Ford returns to try and catch his wife with the knight, the wives have the basket taken away and the contents (including Falstaff) dumped into the river. Although this affects Falstaff's pride, his ego is surprisingly resilient. He is convinced that the wives are just "playing hard to get" with him, so he continues his pursuit of sexual advancement, with its attendant capital and opportunities for blackmail.

Again Falstaff goes to meet the women but Mistress Page comes back and warns Mistress Ford of her husband's approach again. They try to think of ways to hide him other than the laundry basket which he refuses to get into again. They trick him again, this time into disguising himself as Mistress Ford's maid's obese aunt, known as "the fat woman of Brentford". Ford tries once again to catch his wife with the knight but ends up hitting the "old woman", whom he despises and takes for a witch, and throwing her out of his house. Having been beaten "into all the colors of the rainbow", Falstaff laments his bad luck.

Eventually the wives tell their husbands about the series of jokes they have played on Falstaff, and together they devise one last trick which ends up with the Knight being humiliated in front of the whole town. They tell Falstaff to dress as "Herne, the Hunter" and meet them by an old oak tree in Windsor Forest (now part of Windsor Great Park). They then dress several of the local children, including Anne and William Page, as fairies and get them to pinch and burn Falstaff to punish him. Page plots to dress Anne in white and tells Slender to steal her away and marry her during the revels. Mistress Page and Doctor Caius arrange to do the same, but they arrange Anne shall be dressed in green. Anne tells Fenton this, and he and the Host arrange for Anne and Fenton to be married instead.

The wives meet Falstaff, and almost immediately the "fairies" attack. Slender, Caius, and Fenton steal away their brides-to-be during the chaos, and the rest of the characters reveal their true identities to Falstaff.

Although he is embarrassed, Falstaff takes the joke surprisingly well, as he sees it was what he deserved. Ford says he must pay back the 20 pounds 'Brook' gave him and takes the Knight's horses as recompense. Slender suddenly appears and says he has been deceived – the 'girl' he took away to marry was not Anne but a young boy. Caius arrives with similar news – however, he has actually married his boy. Fenton and Anne arrive and admit that they love each other and have been married. Fenton chides the parents for trying to force Anne to marry men she did not love and the parents accept the marriage and congratulate the young pair. Eventually they all leave together and Mistress Page even invites Falstaff to come with them: "let us every one go home, and laugh this sport o'er by a country fire; Sir John and all".

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still obsessed. (you know it's a serious research day when, PART 2)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

ON BEING COLORFUL

by Alexander Freeling

Only some colors are colorful. To be full of color implies intensity and saturation. This is why colorful also means to be bright, lively, and expressive. It can also be euphemistic: if my language is a bit coarse, you might call it colorful, though if it was really improper you could say that I was being blue.

Yet most blues are not colorful. The common tones are pale washes like an English sky, and deep blues from royal to midnight navy. In clothing, product and industrial design, the ubiquity of blue makes it a commonplace if not a default. Jeans, my favorite coffee mug, the ink in most of my pens. The abundance of blues makes them behave almost like greyscale in menswear: turn up in navy denim, a pale blue Oxford, and a mid-blue windbreaker and nobody bats an eye. Swap it out for banana yellow chinos, a lemon shirt, and buttercup raincoat and you’re immediately third-rate British superhero Bananaman. (Cancel that: I checked, and his outfit is largely blue.)

To dress colorfully is to announce yourself. In Elizabethan England, a 1574 statute insisted that purple silk, gold cloth, and sable furs were reserved for the king or queen’s immediate family, though you could enjoy purple discretely (lining your cloak, say) as a duke, marquise, or earl. Crimson or scarlet velvet was similarly restricted (though here the guest list stretched to lower end aristocrats: viscounts, barons, Knights of the Garter, and members of the Privy Council). In practice, these laws were frequently ignored and impossible to enforce: call it desperate social climbing or dressing for the job you want. But whether legitimate or simulated, color asserts status. (The decidedly less fabulous successor to the crimson velvet doublet is the brick red chino, beloved summertime garb of plump, bourgeois middle England.)

Colors signal local affiliations, meaning that a shade can be neutral in one place and highly partisan in the next. (I remember yellow scarf getting me misidentified as a home fan in one English town; try a bright green or orange outfit in Belfast to experience the more serious version.)

People are also professionally colorful. Yellow rainwear is handy for sailors since it’s easily visible if you fall overboard. In 1974, London Fire Brigade introduced bright yellow pants to their uniform for similar reasons. There are red coats in old-world military uniforms thanks to the pitched battles of the Napoleonic era, where quick identification was life and death.

Above all, to be colorful is to say: “I am here.” This can be daring, aggressive, or simply jubilant; it can signal group affiliation or individuality. It can be thoroughly social (wanting to turn heads) or wholly self-absorbed (the absent-minded professor in an all-mauve outfit; the child fixated on orange). Men tend to be uneasy about color because they don’t want to stick out (this is why uniforms are fine, however garish), and they don’t want to draw the gaze of others (women, I suspect, don’t have this uneasiness because they know they’ll be scrutinized either way).

To be colorful is to speak freely. To be overheard, in contexts not of your choosing. Sometimes it pays to keep your peace. But before you commit to a monochrome life of Swedish minimalism or endless grey t-shirts, it’s worth finding your voice.

My friend Mordechai Rubinstein sees color everywhere. In chips of paint, nail polish, and the patina of old trucks, he once told me. His photographs home in on the glint of purple socks, a yellow vest, or paint-spattered overalls. What’s exceptional is that the colors hardly ever screech: they’re joyous, sincere, and utterly unforced. Being colorful, done right, is not shouting but singing.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historic Royal Signatures

Edward VI

Edward, born in 1537 was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, and England's first monarch to be raised as a Protestant. His mother died of postnatal complications less than two weeks after the birth of her only child.

Edward was CHRISTENED on 15 October, with his half-sisters, the 21-year-old Lady Mary (later Mary I) as godmother and the 4-year-old Lady Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I)carrying the chrisom; and the Garter King of Arms proclaimed him as Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester.

At the age of four, he fell ill with a life-threatening "quartan fever", but, despite occasional illnesses and poor eyesight, he enjoyed generally good health until the last six months of his life.

From the age of six, Edward began his formal EDUCATION under Richard Cox and John Cheke, concentrating, as he recalled himself, on "learning of tongues, of the scripture, of philosophy, and all liberal sciences". He received tuition from Elizabeth's tutor, Roger Ascham, and Jean Belmain, learning French, Spanish and Italian. In addition, he is known to have studied geometry and learned to play musical instruments, including the lute and the virginals. He collected globes and maps and, according to coinage historian C. E. Challis, developed a grasp of monetary affairs that indicated a high intelligence. Edward's religious education is assumed to have favoured the reforming agenda. His religious establishment was probably chosen by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a leading reformer. Both Cox and Cheke were "reformed" Catholics or Erasmians and later became Marian exiles.

Both Edward's SISTERS were attentive to their brother and often visited him – on one occasion, Elizabeth gave him a shirt "of her own working". Edward "took special content" in Mary's company, though he disapproved of her taste for foreign dances; "I love you most", he wrote to her in 1546

On 1 July 1543, Henry VIII signed the Treaty of Greenwich with the Scots, sealing the peace with Edward's betrothal to the seven-month-old MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS. The Scots were in a weak bargaining position after their defeat at Solway Moss the previous November, and Henry, seeking to unite the two realms, stipulated that Mary be handed over to him to be brought up in England. When the Scots repudiated the treaty in December 1543 and renewed their alliance with France, Henry was enraged. In April 1544, he ordered Edward's uncle, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, to invade Scotland. Mary later married the Dauphin of France, Francis.who later became King Francis II.

On 28 January 1547, Henry VIII died, the ten year old Edward, became Edward VI.

Although Edward reigned for only six years and died at the age of 15, his reign made a lasting contribution to the English Reformation and the structure of the Church of England. The last decade of Henry VIII's reign had seen a partial stalling of the Reformation, a drifting back to more conservative values. By contrast, Edward's reign saw radical progress in the Reformation. In those six years, the Church transferred from an essentially Catholic liturgy and structure to one that is usually identified as Protestant. In particular, the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer, the Ordinal of 1550, and Cranmer's Forty-two Articles formed the basis for English Church practices that continue to this day.

In February 1553, at age 15, Edward fell ill. When his sickness was discovered to be terminal, he and his Council drew up a "Devise for the Succession", to prevent the country's return to Catholicism. Edward named his first cousin once removed, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir, excluding his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth. This decision was disputed following Edward's death, and Jane was deposed by Mary nine days after becoming queen. During her reign, Mary reversed Edward's Protestant reforms, which nonetheless became the basis of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement of 1559.

https://linktr.ee/britishmonarchy.co.uk

#ladyjanegrey#House of grey#Queen of England#The queen#History#English monarchy#English history#Tudor history#Tudors#Tudor#Fun facts#Interesting facts#Royal Family#Royal#BritishMonarchy

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shaksperes

The way in which it all works into ordinary books is this. The compilers of dictionaries, catalogues, compendiums, vade-mecums, and the like, the writers of newspaper paragraphs and literary announcements, are not only a most industrious, but a most accurate and most alert, race of men. They are ever on the watch for the latest discovery, and the last special work on every conceivable topic.

It is not to be expected that they can go very deeply into each matter themselves; but the latest spelling, the last new commentary, or the newest literary ‘ find,’ is eminently the field of their peculiar work. To them, the man who has abolished the ‘ Battle of Hastings ’ as a popular error must know more about history than any man living; and so, the man who writes Shakspere has apparently the latest lights on the Elizabethan drama. Thus it comes that our ordinary style is rapidly infiltrated with Karls and JE If reds, and Senlacs, Qurans, and Shaksperes; till it becomes at last almost a kind of pedantry to object.

How foolish is the attempt to re-name Shakespeare him-self by the aid of manuscripts ! As every one knows, the name of Shakespeare may be found in contemporary documents in almost every possible form of the letters. Some of these are — Shakespeare, Schakespere, Schakespeire, Shakespeyre, Chacsper, Shakspere, Shakespere, Shakespeere, Shackspear, Shakeseper, Shackespeare, Saxspere, Shack- speere, Shaxeper, Shaxpere, Shaxper, Shaxpeer, Shaxspere, Shakspeare, Shakuspeare, Shakesper, Shaksper, Skackspere, Shakspyr, Shakspear, Shakspeyr, Shackspeare, Shaxkspere, Shackspeyr, Shaxpeare, Shakesphere, Sackesper, Shackspare turkey sightseeing, Shakspeere, Shaxpeare, Shakxsper; Shaxpere, Shakspeyr, Shagspur, and Shaxberd. Here are forty of the contemporary modes of spelling his name. Now are the facsimi- lists prepared to call the great poet of the world by whichever of these, as in a parish election, commands the majority of the written documents? So that, if we have at last to call our immortal bard, Chacsper, or Shaxper, or Shagspur, we must accept it; and in the mean time leave his name as variable as ever his contemporaries did?

Various ways

Shakespeare no doubt, like most persons in that age, wrote his name in various ways. The extant autographs differ; and the signature which is thought to be Shakspere, has been simply misread, and plainly shows another letter. The vast preponderance of evidence establishes that in the printed literature of his time his name was written — Shakespeare. In his first poems, Lucrece and Venus and Adonis, he placed Shakespeare on the title-page So it stands on the folios of 1623 and 1632.

So also it was spelled by his friends in their published works; Ben Jonson, by Bancroft, Bamefield, Willobie, Freeman, Davies, Meres, and Weever. It is certain that his name was pronounced Shake-spear (i.e., as *Shake ‘ and Spear’ were then pronounced) by his literary friends in London. This is shown by the punning lines of Ben Jonson, by those of Bancroft and others; by Greene’s allusion to him as the only Shake-scene; and, lastly, by the canting heraldry of the arms granted to his father in 1599: — ‘In a field of gould upon a bend sables a speare of the first: with crest a ffalcon supporting a speare.’

It is very probable that this grant of arms, about which Dethick, the Garter-King, was blamed and had to defend himself, practically settled the pronunciation as well as the spelling. It is probable that hitherto the family name had not been so spelt or so pronounced in Warwickshire. It is possible that Shake-speare was almost a nick-name, or a familiar stage-name; but, like Erasmus, Melancthon, or Voltaire, he who bore it carried it so into literature. For some centuries downwards, the immense concurrence of writers, English and foreign, has so accepted the name. A great majority of the commentators have adopted the same form: Dyce, Collier, Halliwell-Phillipps, Staunton, W. G. Clark. No one of the principal editors of the poet writes his name ‘Shakspere But so Mr. Furnivall decrees it shall be.

One would have thought so great a preponderance of literary practice need not be disturbed by one or two signatures in manuscript, even if they were perfectly distinct and quite uniform. Yet, such is the march of palaeographic purism, that our great poet is in imminent danger of being translated into Shakspere, and ultimately Shaxper.

0 notes

Photo

Shaksperes

The way in which it all works into ordinary books is this. The compilers of dictionaries, catalogues, compendiums, vade-mecums, and the like, the writers of newspaper paragraphs and literary announcements, are not only a most industrious, but a most accurate and most alert, race of men. They are ever on the watch for the latest discovery, and the last special work on every conceivable topic.

It is not to be expected that they can go very deeply into each matter themselves; but the latest spelling, the last new commentary, or the newest literary ‘ find,’ is eminently the field of their peculiar work. To them, the man who has abolished the ‘ Battle of Hastings ’ as a popular error must know more about history than any man living; and so, the man who writes Shakspere has apparently the latest lights on the Elizabethan drama. Thus it comes that our ordinary style is rapidly infiltrated with Karls and JE If reds, and Senlacs, Qurans, and Shaksperes; till it becomes at last almost a kind of pedantry to object.

How foolish is the attempt to re-name Shakespeare him-self by the aid of manuscripts ! As every one knows, the name of Shakespeare may be found in contemporary documents in almost every possible form of the letters. Some of these are — Shakespeare, Schakespere, Schakespeire, Shakespeyre, Chacsper, Shakspere, Shakespere, Shakespeere, Shackspear, Shakeseper, Shackespeare, Saxspere, Shack- speere, Shaxeper, Shaxpere, Shaxper, Shaxpeer, Shaxspere, Shakspeare, Shakuspeare, Shakesper, Shaksper, Skackspere, Shakspyr, Shakspear, Shakspeyr, Shackspeare, Shaxkspere, Shackspeyr, Shaxpeare, Shakesphere, Sackesper, Shackspare turkey sightseeing, Shakspeere, Shaxpeare, Shakxsper; Shaxpere, Shakspeyr, Shagspur, and Shaxberd. Here are forty of the contemporary modes of spelling his name. Now are the facsimi- lists prepared to call the great poet of the world by whichever of these, as in a parish election, commands the majority of the written documents? So that, if we have at last to call our immortal bard, Chacsper, or Shaxper, or Shagspur, we must accept it; and in the mean time leave his name as variable as ever his contemporaries did?

Various ways

Shakespeare no doubt, like most persons in that age, wrote his name in various ways. The extant autographs differ; and the signature which is thought to be Shakspere, has been simply misread, and plainly shows another letter. The vast preponderance of evidence establishes that in the printed literature of his time his name was written — Shakespeare. In his first poems, Lucrece and Venus and Adonis, he placed Shakespeare on the title-page So it stands on the folios of 1623 and 1632.

So also it was spelled by his friends in their published works; Ben Jonson, by Bancroft, Bamefield, Willobie, Freeman, Davies, Meres, and Weever. It is certain that his name was pronounced Shake-spear (i.e., as *Shake ‘ and Spear’ were then pronounced) by his literary friends in London. This is shown by the punning lines of Ben Jonson, by those of Bancroft and others; by Greene’s allusion to him as the only Shake-scene; and, lastly, by the canting heraldry of the arms granted to his father in 1599: — ‘In a field of gould upon a bend sables a speare of the first: with crest a ffalcon supporting a speare.’

It is very probable that this grant of arms, about which Dethick, the Garter-King, was blamed and had to defend himself, practically settled the pronunciation as well as the spelling. It is probable that hitherto the family name had not been so spelt or so pronounced in Warwickshire. It is possible that Shake-speare was almost a nick-name, or a familiar stage-name; but, like Erasmus, Melancthon, or Voltaire, he who bore it carried it so into literature. For some centuries downwards, the immense concurrence of writers, English and foreign, has so accepted the name. A great majority of the commentators have adopted the same form: Dyce, Collier, Halliwell-Phillipps, Staunton, W. G. Clark. No one of the principal editors of the poet writes his name ‘Shakspere But so Mr. Furnivall decrees it shall be.

One would have thought so great a preponderance of literary practice need not be disturbed by one or two signatures in manuscript, even if they were perfectly distinct and quite uniform. Yet, such is the march of palaeographic purism, that our great poet is in imminent danger of being translated into Shakspere, and ultimately Shaxper.

0 notes

Photo

Shaksperes

The way in which it all works into ordinary books is this. The compilers of dictionaries, catalogues, compendiums, vade-mecums, and the like, the writers of newspaper paragraphs and literary announcements, are not only a most industrious, but a most accurate and most alert, race of men. They are ever on the watch for the latest discovery, and the last special work on every conceivable topic.

It is not to be expected that they can go very deeply into each matter themselves; but the latest spelling, the last new commentary, or the newest literary ‘ find,’ is eminently the field of their peculiar work. To them, the man who has abolished the ‘ Battle of Hastings ’ as a popular error must know more about history than any man living; and so, the man who writes Shakspere has apparently the latest lights on the Elizabethan drama. Thus it comes that our ordinary style is rapidly infiltrated with Karls and JE If reds, and Senlacs, Qurans, and Shaksperes; till it becomes at last almost a kind of pedantry to object.

How foolish is the attempt to re-name Shakespeare him-self by the aid of manuscripts ! As every one knows, the name of Shakespeare may be found in contemporary documents in almost every possible form of the letters. Some of these are — Shakespeare, Schakespere, Schakespeire, Shakespeyre, Chacsper, Shakspere, Shakespere, Shakespeere, Shackspear, Shakeseper, Shackespeare, Saxspere, Shack- speere, Shaxeper, Shaxpere, Shaxper, Shaxpeer, Shaxspere, Shakspeare, Shakuspeare, Shakesper, Shaksper, Skackspere, Shakspyr, Shakspear, Shakspeyr, Shackspeare, Shaxkspere, Shackspeyr, Shaxpeare, Shakesphere, Sackesper, Shackspare turkey sightseeing, Shakspeere, Shaxpeare, Shakxsper; Shaxpere, Shakspeyr, Shagspur, and Shaxberd. Here are forty of the contemporary modes of spelling his name. Now are the facsimi- lists prepared to call the great poet of the world by whichever of these, as in a parish election, commands the majority of the written documents? So that, if we have at last to call our immortal bard, Chacsper, or Shaxper, or Shagspur, we must accept it; and in the mean time leave his name as variable as ever his contemporaries did?

Various ways

Shakespeare no doubt, like most persons in that age, wrote his name in various ways. The extant autographs differ; and the signature which is thought to be Shakspere, has been simply misread, and plainly shows another letter. The vast preponderance of evidence establishes that in the printed literature of his time his name was written — Shakespeare. In his first poems, Lucrece and Venus and Adonis, he placed Shakespeare on the title-page So it stands on the folios of 1623 and 1632.

So also it was spelled by his friends in their published works; Ben Jonson, by Bancroft, Bamefield, Willobie, Freeman, Davies, Meres, and Weever. It is certain that his name was pronounced Shake-spear (i.e., as *Shake ‘ and Spear’ were then pronounced) by his literary friends in London. This is shown by the punning lines of Ben Jonson, by those of Bancroft and others; by Greene’s allusion to him as the only Shake-scene; and, lastly, by the canting heraldry of the arms granted to his father in 1599: — ‘In a field of gould upon a bend sables a speare of the first: with crest a ffalcon supporting a speare.’

It is very probable that this grant of arms, about which Dethick, the Garter-King, was blamed and had to defend himself, practically settled the pronunciation as well as the spelling. It is probable that hitherto the family name had not been so spelt or so pronounced in Warwickshire. It is possible that Shake-speare was almost a nick-name, or a familiar stage-name; but, like Erasmus, Melancthon, or Voltaire, he who bore it carried it so into literature. For some centuries downwards, the immense concurrence of writers, English and foreign, has so accepted the name. A great majority of the commentators have adopted the same form: Dyce, Collier, Halliwell-Phillipps, Staunton, W. G. Clark. No one of the principal editors of the poet writes his name ‘Shakspere But so Mr. Furnivall decrees it shall be.

One would have thought so great a preponderance of literary practice need not be disturbed by one or two signatures in manuscript, even if they were perfectly distinct and quite uniform. Yet, such is the march of palaeographic purism, that our great poet is in imminent danger of being translated into Shakspere, and ultimately Shaxper.

0 notes