#edward iv by unknown artist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

men's fashion + art

#stanislaw czachorski by wladyslaw czachorski#gustav pongratz by vlaho bukovac#william b ogden by anders zorn#sir william edward parry by sammuel drummond#harry melvill by jacques-emile blanche#arthur atherley as an etonian by thomas lawrence#james hazen hyde by theobald chartran#portrait of a young man by richard dadd#gorchakov by bogdanov-belsky#anthony ashley-cooper by francis grant#prince george by john lucas#unknown english nobleman by unknown artist#edward phelips iv by bartholomew dandridge#portrait of count of provence by francois-hubert drouais#portrait of gerolamo giustiniani by unknown#portrait of a man with florence in the background by louis gauffier#portrait of daniel sanxay by joseph highmore#portrait of marc-conrad buisson#portrait of amaro guedes pinto by antonio manuel da fronseca#retrato de jose maria benitez bragana by rafael tegeo#louis-auguste schwiter by eugene delacroix#infante charles of spain by juan pantoja de la cruz#white tie by j.c. leyendecker#portrait of ludwik wodzicki by henryk siemiradzki#portrait of jan dzierzyslaw tarnowski by kazimierz pochwalski#scroll of yinti prince xun and his wife#portrait of the hong merchant mowqua by unknown#portrait of an egyptian by franz xaver kosler#moroccan portraits by josep tapiro i baro#portrait of a young black man italy by alessandro longhi

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

taylor swift lyrics x colors x textiles in art – red

Fifteen – Fearless // Augusta of Bavaria with Her Children – Andrea Appiani ❤️ Love Story – Fearless // Portrait of a Prussian Prince – Unknown Artist ❤️ Red – Red // Apples – Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin ❤️ All Too Well – Red // Birdsong – Károly Ferenczy ❤️ All Too Well – Red // Portrait of a Lady – John Opie ❤️ The Moment I Knew – Red // Portrait of Sophia Hedwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg – attributed to Wybrand de Geest ❤️ Nothing New – Red // Sibylla Palmifera – Dante Gabriel Rossetti ❤️ Blank Space – 1989 // Tomaž Hren – unknown artist ❤️ Style – 1989 // Ernest Amadej Tomaž Attems – unknown artist ❤️ Wildest Dreams – 1989 // A Vision of Fiametta – Dante Gabriel Rossetti ❤️ New Romantics – 1989 // Portrait of Armand Gaston Maximilien de Rohan – Hyacinthe Rigaud ❤️ End Game – Reputation // A Genoese Lady with Her Child – Anthony van Dyck ❤️ I Did Something Bad – Reputation // Marie-Adélaïde de France – Johann Julius Heinsius ❤️ Look What You Made Me Do – Reputation // Infanta Isabel of Spain – Carlos Luis de Ribera y Fieve ❤️ Daylight – Lover // Self-Portrait – Gwen John ❤️ the lakes – folklore // Maria Amalia of Saxony – Anton Raphael Mengs ❤️ gold rush – evermore // Barine – Edward Poynter ❤️ Maroon – Midnights // Margaret “Peg” Woffington – unknown artist ❤️ Maroon – Midnights // Portrait of Marchessa Marianna Florenzi – Joseph Karl Stieler ❤️ Maroon – Midnights // Henry IV, King of France in Armor – Frans Pourbus the Younger ❤️ Maroon – Midnights // Elizabeth I as a Princess – attributed to William Scrots ❤️ The Great War – Midnights // Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge with Her Children – Melchior Gommar Tieleman

#fearless#fearless taylor swift#red#red taylor swift#red taylor’s version#1989#1989 taylor swift#reputation#reputation taylor swift#lover album#lover taylor swift#folklore#folklore album#folklore taylor swift#folklore ts#evermore taylor swift#evermore ts#evermore#evermore album#midnights#midnights album#taylor swift midnights#midnights taylor swift#taylor swift#long post#taylor swift lyrics x colors x textiles in art

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Phoenix Queen — Historical & Mythological Influences on Lunaruz & Queen Relta [Part I]

Relta is heavily inspired by both Queen Mary I of England & Ireland and her half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I of England & Ireland — along with Eleanor of Aquitaine.

A quote by Queen Mary I of England & Ireland greatly inspires Relta’s outlook on her dynamic with Lunaruz. Essentially, she views herself as married to her kingdom and “mother” to her people. The quote can be found [here]

Relta’s unmarried status and refusal to marry was inspired by Queen Elizabeth I of England & Ireland, along with seeing her parents’ marriage fail and her father gaining the throne, despite her mother having been the heir to Relta’s maternal grandparents who ruled Lunaruz approximately one-hundred and fifty years before Relta’s own reign began.

Relta’s artistic talents are inspired by a young Queen Mary I of England and Ireland, as she was: a known polyglot; skilled dancer; skilled musician; and decent politician.

Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine’s influence on Relta’s Phoenix Queen verse include: (1) she rules a duchy in her own right in otherwise unclaimed territory near Lunaruz, aside from being heir to the throne of Lunaruz; (2) she ruled Lunaruz as regent during her father’s last ten years of reign; (3) Relta ruled in her own right without a spouse, though she did have lovers.

The myth of [Atalanta] partially inspires Relta’s determination for being an independent ruler, along with Queen Elizabeth I’s insistence upon being “The Virgin Queen”. She doesn’t want to be ruled by a man, having suffered a bit under her father’s reign’s later years as he’d become more…misogynistic admittedly, even toward Relta and her younger half-sister, Aislin.

Like Queen Elizabeth I, Relta’s claim to be an unwed queen was questioned. She was believed to have married one of her lovers in secret, like Queen Consort Elizabeth Woodville and King Edward IV had before their official wedding. It was untrue, as Relta would never risk being tied to a male consort who could usurp her. However, she exchanged non-binding, and platonic, vows with one of her close friends as to ensure the woman was protected in court despite not gaining power from the vows.

Relta’s fears of losing lovers also stemmed from many myths she learned in childhood, along with seeing her parents’ “divorce” at a young age. It influenced her avoiding “falling in love” and acting on it in an official, legal way.

Relta also related to Mary, Queen of Scots, in being the sole heir, and a woman, with her mother supposedly having neared the age in which women stopped bearing children when Relta was born. Relta’s half-sister, Aislin, is not a legitimate heir despite Relta declaring Aislin’s eventual children in line for the throne.

Unknown to Relta, her father had a number of illegitimate children, including a son who he tried marrying to Relta to give the son legitimacy. Fortunately, Relta saw the resemblance and cornered her father on the topic and sent her illegitimate half-brother packing in shame. King Henry VIII had tried the same with one of his bastards and Princess Mary (future Queen Mary I).

Relta is, surprisingly, fond of children and very maternal - similarly to Queen Mary I. She often dotted on her ladies-in-waitings’ children, spoiling the children of those close to her. She secretly wished to be a mother herself, but the implications of a father would have undermined her sole claim to the throne.

Relta also had a fear of dying in childbirth, as Queen Consort Elizabeth of York with her final child by King Henry VII did, and considered adoption, yet feared a conspiracy against her to put an enemy’s child on the throne after her, or claiming she was secretly the mother.

Relta studied the queen consorts who came before her, not only in Lunaruz but in similar (culturally) nations/kingdoms, and was slightly paranoid she would die and be replaced like many other queen consorts had been.

#V: the phoenix queen#v: phoenix queen#Muse: Relta#headcanons#headcanon: Relta#v: medieval fantasy#mobile post#Childbirth death tw#death tw#incest tw

1 note

·

View note

Text

Elizabeth Woodville, Queen Consort of Edward IV of England.

Artist and date unknown.

Elizabeth Woodville (1437-1492) was renowned for her beauty, but did not hail from a great aristocratic family. Indeed, her parents had caused a huge scandal when they married because her mother, Jacquetta of Luxemburg, should not have done so without royal consent (that’s another story for another time). When Edward IV married Elizabeth in 1464, he was the first king in four centuries to marry one of his subjects, the act of which also provoked public concern and condemnation. Their union earned Elizabeth the moniker ‘The White Queen’ in reference to the emblem of the white rose sometimes associated with the Yorkist branch of the Plantagenet royal family, yet she herself had grown up in a Lancastrian background.

I’ve been listening to a couple of videos about her life on a YouTube history channel sent to me by my friend Gareth - just listening to it is emotionally draining; for her experiencing it, day in, day out, must have felt as though she was going through a living Hell. A teenage bride and mother, widowed with two sons in her early twenties, she probably thought things were on the up when she married the King of England three years later. However, her life was to be deeply and tragically affected by the ongoing 'Wars of the Roses' (1455–1487), the battle for the throne that raged and wrought destruction between the two aforementioned branches of the royal family.

The marriage was immediately unpopular on account of Elizabeth’s background, and her being several years older than her new husband, plus her previous status as a widowed mother of two, possessing no royal dowry, but nevertheless the couple stayed together for just short of twenty years and produced ten children. Events remained far from stable throughout their marriage, though. Most shocking was the disappearance of two of the children who became known as the two ‘Princes in the Tower’ (Edward V, who was due to be crowned, and his brother, Richard of Shrewsbury) and were presumed to have been murdered. Elizabeth’s son by her first marriage, Richard Grey, was executed that same year (1483) and she’d already lost her father and brother over a decade earlier, executed in 1469, after a Yorkist defeat.

Edward, whose love for Elizabeth was much-celebrated though not imbued with fidelity, had died aged 40, probably of ill health, also in 1483. Within the space of three and a half months, she had lost her husband, three of her sons and another brother. After Edward’s death, Elizabeth had to stand by while her brother-in-law, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, whom it’s suspected had arranged the murder of her two boys, was crowned King Richard III, and declared that her marriage to Edward IV had been invalid, their children illegitimate and saw to it that she’d receive no further income.

How on earth did she cope with so much grief and fear and uncertainty? Remember, she spent altogether a total of nine years in the state of pregnancy and risked her life twelve times in the event of childbirth. She outlived two husbands, six of her twelve children, and twelve of her thirteen siblings. In the earlier days of her marriage, she’d been powerless to assist while her mother was accused by her in-laws of witchcraft (of which she was later exonerated) and she finally lost her mother in 1472, when Jacquetta died of ill health in her mid-fifties. Elizabeth was around the same age herself when she too died from ill health. Yet at least she lived to see her daughter, Elizabeth of York, become Queen Consort of England when she married King Henry VII (Henry Tudor). This happy, loving marriage brought peace to the country at last, as it finally united the two warring factions of the Yorkists and the Lancastrians.

Needs checking!

The video about the life of Elizabeth Woodville is in two parts - the first part can be accessed via the link here. It’s a pity the videos are interrupted with adverts, otherwise it’s a good listen. Warning: the fact that they all have the same names (Edward, Richard, Elizabeth, Margaret, etc) will slowly drive you insane! Plus the story itself is very, very complicated…

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

TEN

In the far-off days, when Superstition, in close association with the ‘evil sister’ of Ignorance, walked abroad in the land, the south-western district of Scotland shared very largely in the beliefs and terrors embraced under the general descriptive term of witchcraft. Active interference in the routine of daily life on the part of the Prince of Darkness and his agencies was fully believed in.

J. MAXWELL WOOD, Witchcraft and Superstitious Record in the South-Western District of Scotland (1911)

TWO SIBLINGS ZOOM along a zipwire, smiling and laughing in the mid-day sun while the grown-ups sit on benches with ice creams. Chaffinches chirp cheer into Silvercraigs park in the artist’s town of Kirkcudbright on a glorious Spring Saturday full of light; but something very dark happened here. Elspeth McEwan, who had tried to live a free-spirited life communing with nature in the Galloway countryside, was strangled and burned at the stake where caravans now sit. A spiritual woman, she healed with herbs and had a way with animals, but Scotland’s satanic panic was at full pelt, and there are many column yards in old records that tell of the holocaust that a paranoid, misogynistic and propagandist Church meted out to so-called witches. She was executed in August 1698 and, while she burned, her executioner, William Kirk, drank a pint of ale that cost the burgh two Scots shillings. The provost pocketed £2, 16 shillings for his input. They spent two pounds on peat and coal to burn her, one Robert Creighton received eight shillings for beating the drum, Andrew Aitken pocketed £1, 4 shillings for ‘ane tarr barle’, and Hugh Anderson got six shillings for carrying the ‘peits and colls’. Such was the arithmetic of municipal murder.

Before the world enlarged for rural communities many people thrived on stories of ghosts, warlocks, witches, kelpies, spunkies, carlins, and brownies. Cattle were protected with pieces of rowan wood as charms against witchcraft. Long before television and the internet, most Scottish folk believed in tall tales and added to them around a cottar’s ingle or in one of the inns. At a time when the Church played God, devils appeared as hares or crows. Witches were seen going through keyholes or riding on broomsticks. Odd-looking people, eccentrics, loners, herbalists and nonconformists were all fair game to individuals who took a dislike to them and accused them of having the evil eye. Disgruntled cottagers would blame an easy target when livestock died or were ill.

Daniel Defoe had passed through Kirkcudbright in 1725 and moaned about local indolence: ‘Here is a harbour without ships, a port without trade, a fishery without nets, a people without business.’ If the gentry, over whom Defoe fawned, had concentrated on economic development rather than the murder and persecution of vulnerable and innocent souls, the English spy and provocateur might have left a more meaningful reportage.

Defoe passed by long before Kirkcudbright was talked of as ‘the St Ives of Scotland’. Artists, notably the so-called Glasgow Boys, were drawn to the light of the harbour town and it inspired them to paint rural subjects in the open air. In 1901 Edward Hornel bought Broughton House in Kirkcudbright and lived there the rest of his days. His house and library are now administered by the National Trust for Scotland. Jessie M King also made her home in Kirkcudbright and Charles Oppenheimer, William Mouncey, and several other artists had strong local connections.

The denizens of present-day Kirkcudbright recently converted a disused primary school into a ‘dark sky planetarium’ for skygazers. We saunter from there down a pleasant peninsula of old woodlands carpeted with hyacinths and campions. A woman in jodhpurs walks an unknown breed of dog on the longest lead I’ve ever witnessed and mouths a hello. The peninsula divides the bays of Manxman’s Lake and Goat Well Bay in the estuary of the River Dee. Up in the wild blue, two buzzards claim the sky, soaring on the thermals past bulging birches and born-again oaks on the peninsula of St Mary’s Isle, where John Paul Jones tried to kidnap the Earl of Selkirk and Burns first spoke his ‘Selkirk Grace’.

The ancient name of St. Mary’s Isle was Trayl, but it was renamed after a priory was built by Fergus, First Lord of Galloway, in the 12th century, and dedicated to St. Mary. There is very little left of the priory; all the buildings were removed long ago for Selkirk’s mansion and pleasure grounds.

Lord Cockburn called Kirkcudbright ‘the Venice of Scotland’, although he preferred it at high tide rather than in ‘a world of squelch’. But the tide is low as we traipse, and it looks splendid. A single red kite floats above as we munch oatcakes and gaze out at Little Ross Island lighthouse, whose keeper, Hugh Clark, was murdered by his colleague, Robert Dickson. According to M. M. Harper in his Rambles in Galloway (1876), there is a cavern or underground chamber on the islet, and King William’s fleet anchored in the bay out there on its passage to Ireland.

A stroll among the requiescats in Kirkcudbright cemetery reveals the grave of Billy Marshall, the king of the gypsies, who is said to have lived till he was 120. People still place pennies on top of gravestone, along from Scotland’s most southerly pagan Viking grave. Here lie rich merchants, Covenanters and benefactors, five of the 501 victims of the torpedoing of RMS Leinster in 1918, and also local boy John McClure, who became an admiral in the Chinese Navy during the first Sino-Japanese war.

From his cell in Newgate prison in the 1790s travel writer Robert Heron, who was Burns’s first biographer, hailed Gatehouse-of-Fleet one of the finest villages in Scotland. Nowadays it is within an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is itself an Outstanding Conservation Area. It is hard to credit that the gentry spent a century or so trying in vain, via cotton mills, breweries and a shipyard, to turn Gatehouse, which the Cromwellian spy Thomas Tucker had described in 1655 as ‘not worth the nameing’ into a new Glasgow. It has a medieval fortress on its doorstep, an imposing greystone streetscape, a sylvan scarf of woodland, and a decent-sized hill next door. Even Cockburn admitted 40 years after Heron’s Scottish tour, that (although it was ‘too visibly the village at the Great Man’s Gate’) Gatehouse was clean and comfortable. He added: ‘.... with its wood, its well-kept home ground, its varied surfaces, its distant bounding hills and its obvious extensive idea of a great and beautiful domain it is one of the finest in Scotland.’

Cardoness Castle, an impressive 15th-century tower, which stands prominently on a bluff off the A75 just outside Gatehouse, has a chilling history. For generations it was held by the McCulloch family, who were notoriously lawless. The McCullochs, descendants of a king of the Britons of Strathclyde, were engaged in a vendetta with the Gordon family. Sir Godfrey McCulloch murdered William Gordon and fled to France. But he was finally tracked to a house in Edinburgh where he was masquerading as a Mr Johnstone; he was brought to justice after 13 years at large and was one of the last people to be executed on the Iron Maiden, a Scottish version of the guillotine. (There is a fanciful tale that a gnome saved him from the executioner.)

Until November 12th, 1909, a famous beech tree stood in the castle park, but it was destroyed in a storm. The MacCullochs had planned to cut it down in 1800, but there was considerable protest and the poet Thomas Campbell penned a poem he called The Beech Tree’s Petition. It was reprieved – for Nature eventually to take its course.

Thomas Carlyle is reputed to have told Queen Victoria that the road from Creetown to Gatehouse of Fleet was the most beautiful in her kingdom, and the road back was second best. Sir Walter Scott, the man who invented Scottish tourism, gathered a lot of smuggling tales and myths in these parts, many of them from Joseph Train, an exciseman, who worked in Dumfries and Galloway.

In 2012 archaeologists unearthed artefacts that proved that Trusty’s Hill, near Gatehouse, was the site of a sixth-century royal stronghold. Historians had hitherto assumed that the lost Dark Age kingdom of Rheged had been in Cumbria. Here was evidence that Galloway was at the heart of Rheged, the post-Roman Brythonic kingdom that was part of the Hen Ogledd of the Old North.

Gatehouse is the Kippletringan of Guy Mannering, and Dirk Hatterick’s cave is on the nearby Heughs of Barholm, which you can reach through Ravenshall Wood from a layby on the A75. (Cockburn called the cave ‘a narrow, wet, dirty slit in a rock, produced by the washing away of the loose matter between two vertically laminated rocks, and answering Scott’s scenery in no one respect, either outside or in’.) Scott had based Hatterick on the real-life Captain Yawkins, a vicious Manx pirate who operated along the Solway.

Burns is reputed to have written ‘Scots Wha Hae’ at the Murray Arms Hotel; much of John Buchan’s The Thirty-nine Steps was based on the moors beyond Gatehouse; Dorothy L Sayers based The Five Red Herrings in the town, and a John Buchan trail has been established in the area.

The demon drink was a frequent cause of moral concern among ministers and other moralisers in those days. Not so with the more proletarian Heron, who observed: ‘Tippling houses are wonderfully numerous. I was informed by the excellent Exciseman of the place [Gatehouse], that no fewer than 150 gallons of whisky alone had been consumed here for the last six months.’

But Heron’s fondness for liquor shortened his life and impoverished him, which is why he had been imprisoned in Newgate for debt.

The bohemian maverick Alexander Trocchi had an addictive personality too. That future bad boy of the literary world, and pornographer, was evacuated to Galloway during the war, to be schooled at what is now Gatehouse’s Cally Palace Hotel. Hugh McMillan, author of McMillan’s Galloway, told me Trocchi might have been expelled but for the fact that his great-uncle Tito was a cardinal on the shortlist to succeed Pope Pius XI.

‘He became obsessed with the number of UFO sightings in the area and, with a group of mates, started a secret society to discuss and speculate about them,’ said McMillan. ‘They dressed in tin foil suits and formed a ‘Martian Party’, which romped home in the school elections, beating Labour to a distant second.

‘Due to his many escapades, Trocchi nearly left school without the vital leaving certificate, but the headmaster relented and stuffed it through the bus window as he was leaving for Glasgow. I’m presuming that it’s easier to commemorate Jim Barrie because he didn’t pimp his wife out for heroin like Trocchi. However, a plaque would be the least we could do.’

Another obscure Galloway anecdote: if you walk the old railway line between Creetown and Gatehouse of Fleet you will come upon a bridge on which one Polish Joe, a refugee mason, inscribed the name of Hitler and a coffin when he repaired the bridge on August 15th, 1940.

#witchcraft#superstition#Kirkcudbright#execution#daniel defoe#glasgow boys#jessie m king#st mary's isle#little ross#murder#billy marshall#gatehouse#rheged#trocchi

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is one of my favourites! Look at all that blue and gold!

The Wilton Diptych, by an unknown artist, c. 1395–1399.

The diptych was painted for King Richard II of England, who is depicted kneeling before the Virgin Mary and child. The figures standing beside him are (left to right) King Edmund the Martyr, King Edward the Confessor, and the patron saint, John the Baptist.

Richard II was crowned King of England in 1377 at the age of ten years old and his reign was to last for 22 years. He was the grandson of war-hungry Edward III, his father, Edward, the Black Prince having died before he could inherit the throne himself. Richard was more interested in the arts; another fact about him is he was 29 years old when he married the six-year old Isabella of Valois to cement political allegiance between England and France. (He had been married previously to Anne of Bohemia, who died age 28 possibly from the plague).

I'm sketchy about what happened during Richard’s reign to cause him to be deposed in 1399. He was succeeded by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, who was crowned Henry VI the same year. I'll find out more about this painting - I have info in loads of books and will add something here later. Also need to read up on Shakespeare's history plays about both Richard II and Henry IV.

EDIT: Richard was imprisoned and died, either by murder or through self-starvation, in Pontefract Castle in 1400.

See episode 415: 'The Murder of Richard II' by Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook from 'The Rest is History' podcast (link here).

0 notes

Photo

Classic art \ historical painting + colours \ yellow

1/?

next : blue

#art#history aesthetics#classic painting#classic art#historical painting#my edit#carl vilhelm holsøe#george frederic watts#john atkinson grimshaw#jean honoré fragonard#marguerite gérard#edward iv by unknown artist#edward iv#ferdinand knab#jacques-louis david#random aesthetics#history edit#aesthetics#+classicpainting

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unknown Woman thought to be Catherine Woodville, date and artist Unknown.

Sister to Elizabeth Woodville, Queen Consort of Edward IV. In turn making her the maternal aunt to Elizabeth of York, Queen Consort to Henry VII.

First the Duchess of Buckingham by her first marriage to Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham. Through this marriage she was the mother to Edward, 3rd Duke of Buckingham*, Elizabeth, Countess of Sussex, Henry, Earl of Wiltshire and Anne, Countess of Huntingdon**.

Second the Duchess of Bedford and Countess of Pembroke by her second marriage to Jasper Tudor, Duke of Bedford and Earl of Pembroke making her the aunt of King Henry VII by marriage. No issue came from this union.

Her third marriage was to Richard Wingfield no titles were granted to him on the occasion of their marriage. No issue came from this union.

*Edward, Duke of Buckingham was executed by Henry VIII. **Also known as Anne Hastings upon her marriage, she was the rumoured mistress of Henry VIII and possibly William Compton.

#portrait#historyedit#Catherine Woodville#original edit#edit#possibly a portrait based off an original of her sister

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ELIZABETH WOODVILLE (c.1437–1492), 2nd Foundress of Queens' College, Wife of Edward IV.

Oil on canvas, unknown artist, Queen’s College, University of Cambridge

#historyedit#artedit#history#elizabeth woodville#15th century#the wars of the roses#medieval#the middle ages#women in history#art#always and forever queen

154 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon (1535–1595). Unknown artist.

He was the eldest son of Francis Hastings, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon, and Catherine Pole. Through his mother, he was descended from George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, who was a brother of King Edward IV. This gave him some claim to the throne.

#kingdom of england#house of plantagenet#house of york#english aristocracy#henry hastings#earl of huntingdon#house of hastings

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The True Story Behind James Cameron’s Titanic

https://ift.tt/3shvKln

James Cameron’s 1997 blockbusting tearjerker, Titanic, puts an epic love story in the middle of the greatest maritime disaster in the history of the North Atlantic. On April 15, 1912, midway through its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg. Because of a severe shortage of lifeboats, 1,517 people died. In the weeks which followed, the luxury liner was said to have been billed as “unsinkable,” but that claim had never been made until after the nautical disaster.

This and other myths have lived on, thanks particularly to Cameron’s romantic (and often fanciful) movie. And yet, not all truths have been lost at sea.

Jack and Rose

Jack Dawson, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, and Rose DeWitt Bukater, played by Kate Winslet as a young woman and Gloria Stuart when elderly, are a myth. They are fictional characters. Jack wasn’t slipped $20 for rescuing Rose, and never taught her how to spit off the side of a ship like a man. But there was a member of the Titanic crew named Joseph Dawson. Born in Dublin, Joseph Dawson worked as a coal trimmer, evening out piles of coal which were shoveled into the ship’s furnaces.

Rose DeWitt-Bukater is the first film character portrayed by two actors who were both nominated for an Academy Award. Winslet was nominated as Best Actress, and Stuart was nominated as Best Supporting Actress. Rose is modeled on Beatrice Wood, who did not travel on the Titanic. Born in San Francisco to wealthy parents, her coming out party was cancelled the same year the Titanic sank.

Beatrice joined the French National Repertory Theatre under the stage name Mademoiselle Patricia, playing more than 60 roles before she was noticed by artist Marcel Duchamp. She was well known by artists during the Dada period, and lived long enough to be invited by James Cameron to the opening of Titanic.

Captain Edward John Smith

Before skippering the Titanic, Capt. Edward John Smith (Bernard Hill) spent 40 years at sea without major incidents. Smith had been working on boats since he was a teenager. He earned a master’s certificate, which is required to serve as captain, in 1875. He became a junior officer with the White Star Line in 1880. He commanded his first ship in 1887. Like many veteran captains, he occasionally ran ships aground, and was captain of the Olympic when it collided with the British cruiser Hawke off the Isle of Wight in 1911, a year before he helmed the Titanic.

The Titanic received iceberg warnings several days into its maiden voyage. Smith adjusted the course but reportedly did not decrease speed. He was away from the bridge when the ship struck an iceberg. The first damage report, from Fourth Officer Joseph G. Boxhall (Simon Crane), found no damage. But a closer inspection from the Titanic’s designer Thomas Andrews (Victor Garber), found five of the ship’s 16 watertight compartments were flooded. The Titanic could have stayed afloat with up to four flooded compartments. At about midnight, Andrews reported the ship would founder within 60 to 90 minutes. Smith gave orders to uncover the lifeboats and alert the passengers at 12:05 a.m.

Because of some of the reported incidents, some historians wonder whether Smith was in a state of shock at the news. Crewmen didn’t lower the lifeboats until 12:45 a.m., and only because Second Officer Charles Lightoller (Jonny Phillips) reminded the captain to give the order.

Smith’s final moments are unknown. Early newspaper reports alleged he shot himself with a pistol. Several witnesses claimed to have seen him swim to a nearby lifeboat with an infant in his arms before swimming back to the Titanic. Some witnesses said he was swept off deck by a wave, others believed he made it to an overturned lifeboat. Smith’s body was never found.

Joseph Bruce Ismay

J. Bruce Ismay (Jonathan Hyde) was born Dec. 12, 1862, near Liverpool, England. His father was the founder of the White Star Line. Educated at Harrow and tutored in France, he travelled the world before becoming the New York company agent for White Star Line. He became head of Ismay, Imrie & Company after his father’s death in 1899, oversaw its acquisition by J.P. Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine Company in 1902, and was named president of IMM in 1904.

In 1907, Ismay met with Lord Pirrie of the Belfast shipbuilding company Harland and Wolff to discuss building a fast luxury liner with huge steerage capacity which would rival the Cunard Line’s RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania. Three ships were built, the RMS Olympic, RMS Britannic, and the pride of the fleet, the RMS Titanic. The ship was built by British White Star Lines at a cost of $10 million. It weighed 46,000 tons and was 882.5 feet long.

History puts culpability for the Titanic disaster on Ismay. He reportedly demanded the captain increase speed in spite of the iceberg warnings, but during the U.S. Senate’s Inquiry into the disaster, he testified the ship was never going at full speed and didn’t even have all of the boilers on. Ismay was the company officer who gave the order to cut the number of lifeboats onboard from 48 to the Board of Trade standard minimum of 16, plus 4 collapsible Engelhardt boats. But Ismay also helped crewmen get the lifeboats ready and convinced passengers to board the lifeboats before danger was visibly apparent. Ismay boarded Engelhardt C, the last lifeboat launched, only 20 minutes before the Titanic crashed beneath the waves.

While Ismay was attacked in the press and branded a coward for escaping while so many working-class women and children died, testimony from surviving officers exonerated his actions as in the best interest of the passengers. Ismay retired from IMM and the White Star Line in 1913.

Chief Engineer Officer Joseph Bell

Joseph Bell (Terry Forrestal) was from Farlam, Cumbria, and a family who had been farmers for generations. Born in March 1861, Joseph began his seafaring career as an apprentice engine fitter at Robert Stephensons and Co. in Newcastle. Bell joined the White Star line in 1885, serving on vessels working the waters of New Zealand and New York.

Joseph, was promoted to Chief Engineer on the Coptic in 1891 and married Maud Bates in 1893. By 1911, he was the Chief Engineer on White Star Line’s Olympic before being transferred to the Titanic. His staff consisted of 24 engineers, six electrical engineers, two boilermakers, a plumber, and a clerk. None survived the sinking.

The Unsinkable Molly Brown

Legend has it, Margaret Tobin Brown (Kathy Bates) was called “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” because she helped evacuate the ship, took up one of the oars in the lifeboat, and threatened to throw Quartermaster Robert Hichens (Paul Brightwell) overboard if he didn’t go back to the boat to save more people. The myth says the nickname was plucked from the first words she said upon landing safely in New York: “Typical Brown luck. I’m unsinkable!” But Brown actually got the tag as an insult from Denver gossip columnist Polly Pry as revenge for the story of a local hero being printed in another magazine first.

Molly Tobin was born in Hannibal, Missouri in 1867. Her Irish family was part of a wave of immigrants who came to America after the country’s industrialization. Margaret went to school until age 13 when she began working in a factory. She left in search of better work conditions. She met J.J. Brown, a mining engineer, and they were married on Sept. 1, 1886. While most of their neighbors in the Leadville, Missouri community lived in devastating poverty because of the 1893 Silver Crash, J.J. discovered gold in Ibex Mining’s Little Johnny Mine, where he was made a primary shareholder. The couple became nearly instantaneous millionaires.

Moving to Denver where the Silver Crash also took a heavy economic toll, Margaret became part of the Progressive movement, fighting for public baths, public parks, and other city improvements. The Browns separated in 1909 but never divorced. Margaret and her daughter Helen were on an extended vacation with Col. John Jacob “Jack” Astor IV and Madeleine Astor in 1912 when they heard news about a family member’s health issue at home and booked passage on the first available ship, the Titanic.

After the crash, Margaret was lowered in lifeboat number six, which was equipped to hold 65 passengers, but set off with 21 women, two men, and a twelve-year-old boy onboard. Margaret manned an oar. Her knowledge of foreign languages helped her bring passengers aboard the Carpathia, the first ship to answer the distress call. Margaret distributed blankets and supplies, and got the first-class passengers to donate money to help less fortunate passengers.

Brown continued her Progressive program, helping miners striking against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. Twenty people were killed when a battle broke out between the miners and private guards hired by the company in one of the most violent labor conflicts in American history. Once the aftermath and PR battles died down, Margaret moved into her summer home in Newport, Rhode Island where she became involved with Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, the President of the National Women’s Suffrage Association.

The two women spearheaded the National Women’s Trade Union League, which advocated for a minimum wage, an eight-hour workday, and did not distinguish between women of the upper classes and working women.

Margaret wrote newspaper articles, gave public speeches, and was drawn to the radical side of the party, which pushed for a national suffrage amendment. In July 1914, Brown and Belmont organized the Conference of Great Women, which led to Margaret’s bid for a U.S. Senator seat representing Colorado. She shifted her focus when World War I broke out, traveling to France to work for the American Committee for Devastated France.

After WWI, Molly indulged her lifelong passion for the stage, performing in plays in Paris and New York. The 1960 Broadway musical The Unsinkable Molly Brown was based on her life, Debbie Reynolds played her in the 1964 film adaptation. Brown died in her sleep on Oct. 26, 1932, at the Barbizon Hotel in New York City.

Madeleine Astor and Jacob Astor IV

Madeleine Astor (Charlotte Chatton) was five months pregnant when she boarded the Titanic in Cherbourg, France with her husband Col. John Jacob “Jack” Astor IV (Eric Braeden); her husband’s valet, and her maid and nurse. Madeleine was the daughter of William Hurlbut Force, a shipping magnate, and her family was part of Brooklyn high society. The Astors were ending their extended honeymoon which began with a trip from New York on Titanic‘s sister ship, the Olympic.

When the Titanic was sinking, Astor’s husband helped her and her maid into lifeboat four but was denied entry himself by Second Officer Lightoller, who said the boats were for women and children only. Col. Astor perished with the ship. Madeleine Astor gave birth on Aug. 14, 1912. Her late husband’s will was conditional, and when Madeleine married her childhood friend, the banker William Karl Dick, four years after the Titanic tragedy, she lost her stipend from his trust fund.

Isidor and Ida Straus

Here’s a real heartbreaker greater than even Kate and Leo. Remember the image of a couple holding each other and crying as water seeps into their cabin? They were based on the tragically real figures of Isidor and Ida Straus, two of the wealthiest people on the Titanic.

Born into a Jewish family in Otterberg in 1845, back when that village was part of the Kingdom of Bavaria and Germany did not yet exist, Isidor immigrated as a child with his family to the United States. Growing up in Georgia when the Civil War broke out, he even considered joining the Confederacy before instead becoming a blockade runner for the South (think Rhett Butler). After the war, he moved to New York City where he met Ida, a fellow immigrant from the Germanic states.

In New York, Isidor worked at L. Straus and Sons, which quickly became the glass and china department at Macy’s. Yes, that Macy’s. The original one. By 1888, Isidor and his brother became partners in the first major American department store. By 1896 they owned it. Around this time, Isidor even served a single term as a Congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives.

When the Titanic hit an iceberg in 1912, Isidor and Ida were returning home after a holiday in France. As a first class passenger woman from one of the finest cabins on the ship, Ida was almost immediately offered space on a lifeboat. Isidor escorted her to it, but when it came time to get on, she refused. She wouldn’t leave her husband. Isidor was then also offered a spot on the lifeboat beside her, but he also refused, saying he would “not go before other men.”

So both of them declined the lifeboat space and instead gave it to Ida’s maid. One witness said she heard Ida say, “We have been living together for many years. Where you go, I go.” They walked off back toward the neck, never to be seen again.

And the Band Played On

The crew of the RMS Titanic took the adage “women and children first” very seriously. The Titanic‘s eight-member band, led by violinist Wallace Hartley (Jonathan Evans-Jones), never even jockeyed for position. When the band heard the ship was going down, they set up in the first-class lounge and played to keep passengers calm. As the water rose, the band moved to the forward half of the boat deck. Hartley worked for the Cunard ship line before taking the gig on the Titanic. The other band members were violinists George Alexandre Krins and John Law Hume, violist and bassist John Frederick Preston Clarke, cellists John Wesley Woodward, and Roger Marie Bricoux, and pianists Percy Cornelius Taylor and Theodore Ronald Brailey.

According to some passengers, the final song played was “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” a hymn written in 1861 by the Rev. John Dykes. Versions of this song play in the films Titanic (1953), A Night to Remember (1958) and Cameron’s Titanic. This was discounted by Colonel Archibald Gracie, an amateur historian who survived the disaster.

Read more

Movies

Saving Private Ryan: The Real History That Inspired the WW2 Movie

By David Crow

Movies

How Saving Private Ryan’s Best Picture Loss Changed the Oscars Forever

By David Crow

“I assuredly should have noticed it and regarded it as a tactless warning of immediate death to us all, and one likely to create panic,” he is quoted as saying in Steven Turner’s book, The Band That Played On: The Extraordinary Story of the Eight Musicians Who Went Down with the Titanic. He recalled that the band played cheerful songs to keep spirits up. Other survivors also reported hearing songs like “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” and “In the Shadows.”

“Nearer, My God, to Thee” was sung by passengers who survived the 1906 wreck of the SS Valencia and had been played during the impending doom on the decks of the Titanic, but those passengers who heard the song had disembarked earlier than the crew. Wireless operator Harold Bride told The New York Times he heard the song “Autumn” before the ship sank.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post The True Story Behind James Cameron’s Titanic appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3asID5P

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

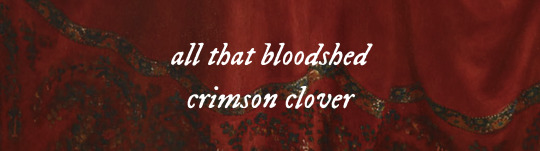

On This Day In History . 2 November 1470 . Edward V was born . 👑 Edward was born at Cheyneygates, the medieval house of the Abbot of Westminster, adjoining Westminster Abbey. His mother, Elizabeth Woodville, had sought sanctuary there from Lancastrians who had deposed his father, the Yorkist King Edward IV, during the course of the Wars of the Roses. . . About Edward; . ◼ Edward V was King of England from his father Edward IV’s death on 9 April 1483 until 26 June of the same year. He was never crowned, & his 86-day reign was dominated by the influence of his uncle & Lord Protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who succeeded him as Richard III on 26 June 1483; this was confirmed by the Act entitled Titulus Regius, which denounced any further claims through his father’s heirs. . ◼ Edward and his younger brother Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, were the Princes in the Tower who disappeared after being sent to heavily guarded royal lodgings in the Tower of London. Responsibility for their deaths was widely attributed to Richard III, but the lack of any solid evidence & conflicting contemporary accounts suggest four other primary suspects. . ◼ Along with Edward VIII, and the disputed Matilda & Jane, Edward V is one of four English monarchs since the Norman Conquest never to have been crowned. As it is generally assumed that he died close to the time of his disappearance, he is the shortest-lived male monarch in English history, his great-nephew, who was crowned Edward VI, died in his sixteenth year. . . King Edward V portrait, by Unknown artist, c.1590-1620 . . . #OnThisDayInHistory #ThisDayInHistory #TheYear1470 #KingEdwardV #EdwardV #EdwardVofEngland #KingofEngland #HouseofYork #Plantagenet #EnglishMonarchy #RoyaltyinArt #History #WarsoftheRoses #BritishMonarchy #D2Nov #EdwardIV #elizabethwoodville #otd #OnThisDay #RoyalHistory #HistoryFacts #theking #princesinthetower #toweroflondon #kingedwardiv #Edward #Royalfamily #Historicart #portraitpainting (at Westminster Abbey) https://www.instagram.com/p/CHGL_HEDouO/?igshid=c0iesuh8eywy

#onthisdayinhistory#thisdayinhistory#theyear1470#kingedwardv#edwardv#edwardvofengland#kingofengland#houseofyork#plantagenet#englishmonarchy#royaltyinart#history#warsoftheroses#britishmonarchy#d2nov#edwardiv#elizabethwoodville#otd#onthisday#royalhistory#historyfacts#theking#princesinthetower#toweroflondon#kingedwardiv#edward#royalfamily#historicart#portraitpainting

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles VII, King of France - Jean Fouquet // Edward IV Plantagenet - Unknown Artist // I've Got a Friend - Maggie Rogers

#okay I know this one's kinda silly but when I heard that line I knew I had to make this#also like I don't understand this line at all?#like imo the 15th c was not exactly fashion forward#but pop off I guess#15th century#I've got a friend#surrender#maggie rogers#art#art history#lyrics#lyric art

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, KG, KB (1535-1595). A descendant of George, 1st Duke of Clarence, the brother of King Edward IV, the blood of the Plantagenets ran in his veins and he was considered in certain quarters to have a strong claim to the throne. He was known for his Puritan sympathies and in 1586 was one of the judges of Mary, Queen of Scots, at her trial. In 1572 Elizabeth appointed him president of the Council of the North. He died on 14 December 1595. Portrait by an unknown artist.

#1500s#1500s art#the tudors#tudor#late 1500s#mid 1500s#tudor england#tudor portraits#early 1500s#portrait#mary queen of scots#elizabeth tudor#elizabeth i#queen elizabeth#lord Hastings#herny Hastings

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elizabeth of York, Queen Consort of Henry VII of England.

Artist and exact date unknown.

As wife of King Henry VII, (Henry Tudor, who defeated King Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485), Elizabeth was Queen Consort of England from 1486 until her premature death in 1503. Despite marrying for pragmatic, political purposes, theirs was a loving and faithful union which lasted seventeen years, and together they produced seven children, one of who was to become one of the most notorious figures in British history - Henry VIII.

As mentioned in previous blog post, Elizabeth was the eldest child of King Edward IV and his queen consort, Elizabeth Woodville. She was not involved in political side of her role as queen (find out more about her relationship with her powerful mother-in-law, Lady Margaret Beaufort), but as a mother, endured the grief of losing her eldest son, the fifteen year old Arthur (the original suitor to Catherine Aragon) and two of her other children in infancy. Sadly, her life was yet another cut short by childbirth, just a few days after giving birth to a daughter, who also passed away. Henry VII was distraught at losing his beloved wife. She was 37.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

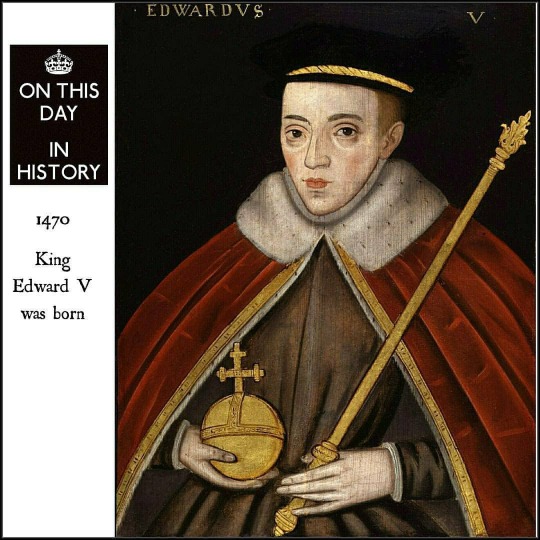

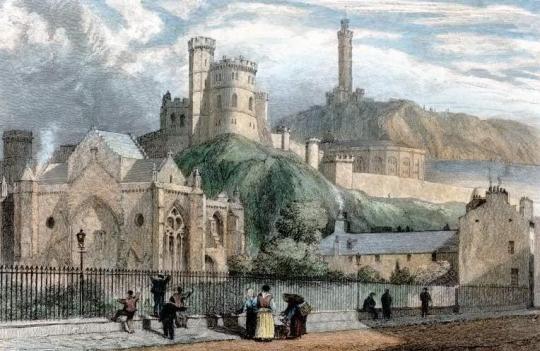

Historical Objects: The Trinity Altarpiece

(Click image for better view. Inside panels are on the right, outside on left. Source- wikimedia commons)

The Trinity Altarpiece is one of the most remarkable objects to have survived from mediaeval Scotland. Produced by Hugo van der Goes in the 1470s, this triptych would have occupied pride of place on the high altar of Trinity Collegiate Kirk in Edinburgh. Though the centre panel is now lost, the wings survive including depictions of the Holy Trinity, angels and saints. Perhaps of more interest are the contemporary historical figures depicted: on the outside of the left-hand panel is pictured the provost of Trinity kirk, Edward Bonkil; on the inside left-hand panel King James III (r.1460-1488), accompanied by a boy who may be the future James IV; and on the inside right-hand panel James III’s queen Margaret of Denmark. A precious survival from a country where only a small percentage of mediaeval art survived the iconoclasm of the Reformation, and centuries of Anglo-Scottish, religious, and civil wars, the Trinity Altarpiece gives a rare glimpse into the vibrant cultural networks of a small European kingdom and the interests of its elites.

This impressive piece was probably created by the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes, who was born in the mid-fifteenth century in the great city of Ghent, then a major European centre. Goes was first mentioned in 1467, the same year he was admitted to the painters’ guild of Ghent. Over the next decade he frequently undertook painting work (both practical and artistic) in Ghent and further afield. He served as both juror and dean of the painters’ guild during the mid-1470s, but by 1478 had retired to the Roode Klooster near Brussels, where he lived for the rest of his life. In later years one of his fellow novices at the Roode Klooster, Gaspar Ofhuys, wrote an account of Goes’ time there, which provides a valuable insight into his life and character. Goes often received visitors, including Maximilian, Archduke of Austria and other notable figures. He was also occasionally allowed to leave the monastery to undertake commissions and travel to some of the region’s cities. While returning from one such trip to Cologne, however, he suffered a fit of madness and attempted suicide. He briefly recovered only to die shortly afterwards, in 1482, tormented towards the end of his life by the thought of not finishing his art. Nevertheless he is now recognised as one of the most significant and talented Flemish painters of his time, despite his short career- and the difficulty of identifying his work.

Most identifications of Hugo van der Goes’ paintings rest on similarities with the Portinari Altarpiece, the only work confidently attributed to him. Thus many of his purported works- which include the ‘Lamentation of Christ’ (now in Vienna), the ‘Adoration of the Kings’ (or the Monforte Altarpiece, now in Berlin), and others which only survive in copies made by his followers- cannot be certainly attributed, though as yet there is no real reason to doubt the Trinity Altarpiece. In any case the Trinity panels are clearly of the highest quality and represent an important contribution to Northern Renaissance art. Moreover, their existence sheds light on the networks of artistic patronage in mediaeval Europe and the links of one particular Scottish churchman and his royal patrons.

(The Portinari Altarpiece, also by Hugo van der Goes. The centre panel flanked by the inside of two wings gives some idea of how the Trinity Altarpiece would have looked when open, before the centre panel was lost. Source Wikimedia Commons)

While they are now appreciated primarily for their artistic value, these mediaeval altarpieces also had a practical purpose. As portable religious items they helped direct the spiritual devotions of their owners, while they also had worldly usefulness, prominently displaying the patron’s political, spiritual, and social networks. In triptychs, patrons and their family members were usually represented on the inside wings, like the royal figures in the Trinity Altarpiece. Here the king and queen of Scots- James III and Margaret of Denmark- are portrayed in rich costume, accompanied by Saints Andrew and George, and a young boy who probably represents their eldest son, James, Duke of Rothesay. Despite the prominence of the royal family however, the Altarpiece may owe its origin to a very different individual. When a triptych was not in use, the inner wings would usually close over a larger centre panel (the Trinity Altarpiece’s appears to have been lost) and the outside panels were often decorated with less showy ‘grisaille’ paintings. In the Trinity Altarpiece, however, these outer panels tell us even more about the work’s provenance. Portrayed on the left outer wing is the Holy Trinity (father, son, and holy spirit) and, on the right wing, kneeling in supplication before the Trinity, a churchman whose coat of arms identifies him as Edward Bonkil, first provost of Trinity Collegiate Church in Edinburgh- the man who probably commissioned this expensive work of art.

Trinity College Kirk, which stood beneath Calton Hill, was founded in 1460 as the pet project of Mary of Guelders, queen consort to James II of Scotland (1437-1460). Mary was not just the daughter of Arnold, Duke of Guelders but also the great-niece of Philip the Good, the powerful Duke of Burgundy, and as Mary was raised at her uncle’s court her marriage to James II strengthened Scotland’s traditional commercial and cultural ties with the Low Countries. A formidable woman, Mary headed the government after her husband’s premature death in 1460, as regent for her young son James III. She also had some reputation as a builder (her other major project was Ravenscraig Castle, the first castle in Scotland built specifically to withstand artillery fire, and she contributed to works elsewhere too). Though work on the church may have begun in her husband’s lifetime, it was chiefly Mary’s project and from 1460 onwards she took a keen interest in the foundation. Besides paying for its endowment and construction, she may have personally contributed to the creation of the college rules, stipulating that all the canons and boys should be capable of reading and singing in plain chant and descant, laying the foundations of Trinity’s reputation as a prestigious choral institution. Following her early death in 1463, she was also buried in the church, probably near the high altar, where the altarpiece likely stood and it has been theorised that the missing middle panel could have included a representation of the queen dowager herself, drawing attention to the church’s royal associations. However the altarpiece was painted after her death, and indeed the responsibility for commissioning this costly piece of art may not have lain with the royal family at all, although Mary’s son James III and his queen feature prominently on its inner panels. It has been argued by Lorne Campbell that we should instead look to the provost of Trinity, Edward Bonkil, portrayed on the right-hand outer panel of the altarpiece.

(Bottom left- Trinity College Kirk, as it appeared in the nineteenth century. Source- Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Bonkil had been a close servant of the late Mary of Guelders, having been personally promoted to the position of provost of her lavish foundation. After the dowager’s death, however, he seems to have gradually fallen out of favour at court and it is suggested by Campbell that he may have commissioned the altarpiece partly with a view to currying favour with the young James III. Whether this is accurate or not, it seems highly probable that Bonkil was the main driving force behind the commission- not only does he occupy a privileged position on the outer wing of the altarpiece, but his features are much more detailed and exact than those of the royal family, suggesting that they were painted from life. As a member of a prominent Edinburgh merchant family, and having possibly served on embassies to Guelders and Burgundy, Bonkil had close connections with the Low Countries. Moreover he is not recorded in Scotland between 1473 and 1476, around the time that the altarpiece may have been painted, and so he could have travelled to Flanders personally to sit for the artist. Though it did not bring him renewed royal favour, if the altarpiece was commissioned by Bonkil it not only secured his legacy but has provided us with a rare and invaluable glimpse into the tastes and cultural connections of late mediaeval Scotland’s clerical elite.

Much of the altarpiece, including the likeness of Bonkil, is believed to have been painted in Flanders by Goes, and certain sections are even adapted from other works by Flemish artists, such as the ‘Madonna in the Church’ by Jan Van Eyck, which forms the backdrop to Bonkil’s panel, and a lost work by Robert Campin which influenced the representation of the Trinity. The faces of King James III and Queen Margaret however, may have been painted over by an unknown artist upon the altarpiece’s arrival in Scotland, to lend them some realism, though they are not of such high quality as the depiction of Bonkil. The portrayal of the young Duke of Rothesay- the future James IV- is probably even less true to life, as portrayals of children in late mediaeval art were more often symbolic than realistic and it is probable that Rothesay was an infant at most at the time of the painting’s creation. His appearance may allow us to tentatively date the work however, as he was born in 1473 and described as James III’s ‘only son’ until 1478-9, and neither of his younger brothers are portrayed in the painting. This place the period of production in the mid-1470s- a rare survival then, from an otherwise shadowy period in late mediaeval Scottish history.

(Edward Bonkil, Provost of Trinity Collegiate Church, who probably commissioned the altarpiece. Source- wikimedia commons)

Despite having been painted almost a century and a half earlier however, the panels from the Trinity Altarpiece were only recorded in written sources for the first time in 1617, when they were included in an inventory taken of the possessions of Anne of Denmark, queen of James VI of Scotland (James III’s great-great grandson and by now James I of England also). The inventory of Queen Anne’s belongings was taken at the royal residence of Oatlands in Surrey, and it has been suggested that the Trinity Altarpiece was brought south after her husband’s last visit to Scotland earlier in 1617. It was to remain in England for many years thereafter, passing into the hands of Anne’s son, Charles I, by 1624, when it was erroneously described as a work by Jan van Eyck. The altarpiece was auctioned off during the Civil War but was reclaimed by the royal family after the Restoration, after which it was displayed in various English royal palaces, including Kensington and Hampton Court. In 1857, it returned to Scotland for the first time in over two hundred years when it was briefly transferred to Holyrood Palace during the reign of Queen Victoria. Over the next few decades it was shuffled around on several occasions, but was often on public display at Holyrood until 1912, when it was first briefly loaned to the National Gallery of Scotland, due to fears over its safety in the face of militant suffragette activity. In 1931, it again returned to the National Gallery, in whose care it remains today.

If anyone has a spare half an hour in Edinburgh some day, I highly recommend visiting the galleries, if only to see the Altarpiece. Flemish art of this period is both fascinating and beautiful and the Galleries are very fortunate to own a piece of such high calibre as the Trinity Altarpiece. As well as this, the culture of mediaeval Scotland has left few traces in the modern day: even the impressive Trinity Collegiate Church, the original home of the altarpiece, was largely demolished in the Victorian period to make way for Waverley Station, while many other pieces of art, books, buildings, music and historical sources have been lost to the ravages of war, iconoclasm, and time. The survival of such a beautiful and costly work as the Trinity Altarpiece, therefore, stands testament to a fascinating and complex past, as culturally vibrant as that of any other corner of mediaeval Europe, and just waiting to be uncovered.

(Source - Wikimedia commons)

Selected Bibliography:

“Charters and documents relating to the Collegiate Church and Hospital of the Holy Trinity, and the Trinity Hospital, Edinburgh, A.D. 1460-1661″, ed. J.D. Marwick

“Rotuli scaccarii regum Scotorum: the Exchequer Rolls of Scoltand”, eds. John Stuart and George Burnett, volumes 6, 7, & 8

“Hugo van der Goes and the Trinity Panels in Edinburgh”, C. Thompson and L. Campbell

“Hugo van der Goes’s Altarpiece for Trinity College in Edinburgh and Mary of Guelders, Queen of Scotland”, T. Tolley

“She is But a Woman: Queenship in Scotland, 1424-1463″, Fiona Downie

National Galleries of Scotland

#Scottish history#art history#early Netherlandish#Northern Renaissance#Flemish history#Flanders#the Low Countries#Hugo van der Goes#Edward Bonkil#Mary of Guelders#James III#Margaret of Denmark#art#historical objects#culture#fifteenth century#late middle ages#Trinity Collegiate Church#Holy Trinity#Edinburgh#Ghent#painting#James IV#Scotland and the World#religion#kirk and people#National Gallery of Scotland#Christianity#the Stewarts#Living in Medieval Scotland

26 notes

·

View notes