#portrait of a young man by richard dadd

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

men's fashion + art

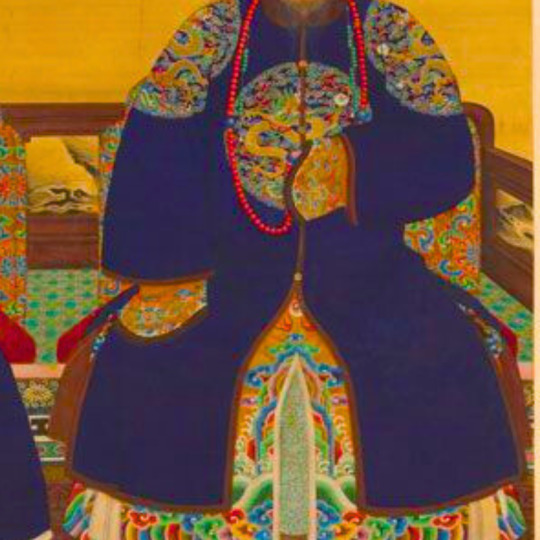

#stanislaw czachorski by wladyslaw czachorski#gustav pongratz by vlaho bukovac#william b ogden by anders zorn#sir william edward parry by sammuel drummond#harry melvill by jacques-emile blanche#arthur atherley as an etonian by thomas lawrence#james hazen hyde by theobald chartran#portrait of a young man by richard dadd#gorchakov by bogdanov-belsky#anthony ashley-cooper by francis grant#prince george by john lucas#unknown english nobleman by unknown artist#edward phelips iv by bartholomew dandridge#portrait of count of provence by francois-hubert drouais#portrait of gerolamo giustiniani by unknown#portrait of a man with florence in the background by louis gauffier#portrait of daniel sanxay by joseph highmore#portrait of marc-conrad buisson#portrait of amaro guedes pinto by antonio manuel da fronseca#retrato de jose maria benitez bragana by rafael tegeo#louis-auguste schwiter by eugene delacroix#infante charles of spain by juan pantoja de la cruz#white tie by j.c. leyendecker#portrait of ludwik wodzicki by henryk siemiradzki#portrait of jan dzierzyslaw tarnowski by kazimierz pochwalski#scroll of yinti prince xun and his wife#portrait of the hong merchant mowqua by unknown#portrait of an egyptian by franz xaver kosler#moroccan portraits by josep tapiro i baro#portrait of a young black man italy by alessandro longhi

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

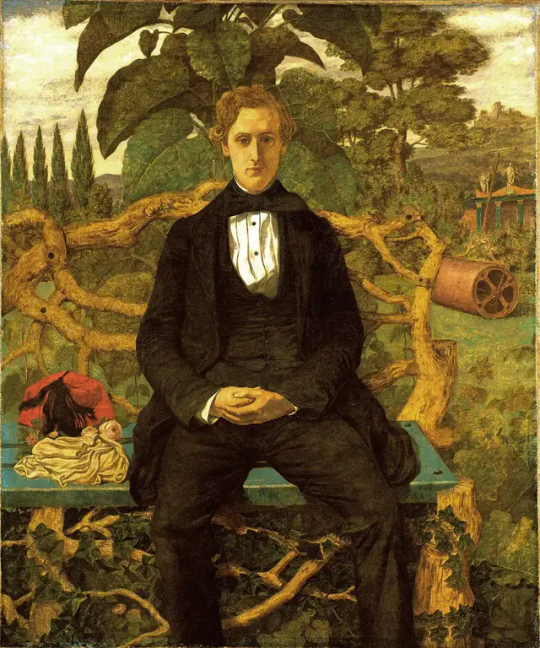

Portrait of a Young Man by Richard Dadd, 1853

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Dadd. “Portrait of a Young Man”, 1853, Oil on Canvas, Tate Museum, London.

0 notes

Photo

Richard Dadd [1817 – 1886]

Portrait of a Young Man [1853]

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dadd’s Murder: The Frightful Tale Behind the Famous Fairies

To look at a piece by English painter Richard Dadd is to be transported to another world. Known for his scenes of fairies, supernatural beings, and images of the far east, Dadd crafted his paintings meticulously with a level of detail that leaves the human eye both stunned and deeply engaged, digging through the image and uncovering new elements with every glance. Trained and awarded for his works of art, it is surprising to hear just how (and potentially why) much of his art came to be. There is a chance we may have never been given many of his works of art if it had not been for a single night of madness and bloodshed.

Puck by Richard Dadd.

Dadd was born in Chatham, Kent, England on August 1st 1817, one of seven children raised by his chemist father after the early death of his mother. His artistic talents were recognized early on in life and before the age of twenty Dadd developed a reputation that many artists could only dream of. He received artistic training at the prestigious Royal Academy of the Arts, his work was exhibited, and in the late 1830s Dadd formed an exclusive “club” with well-known fellow artists Augustus Egg, Alfred Elmore, William Powell Frith, Henry Nelson O'Neil, John Phillip and Edward Matthew Ward. This group, called “The Clique”, rejected the pretentious world of academic art and formed a sketching club where the members would all sketch the same subject matter and have their pieces judged by ���non-artists.” He was young, extremely talented, and poised to become one of the greatest names in art, then he took a trip.

In July 1842 Dadd was approached by Sir Thomas Phillips, a Welsh lawyer, politician, and the former mayor of Newport. Phillips was about to embark on an extensive ten-month excursion through parts of Europe, Greece, Turkey, Syria, and Egypt and he wanted the young artist to accompany him. The pair traveled their course with Dadd filling sketchbooks with drawings that he intended to paint once he returned home. The scenes of the far and middle east pressed themselves deeply into the mind of Dadd, but their impression became much more serious than mere images etched in his books. The entire excursion was ten months long but during the last leg in December the pair was traveling up the Nile when Dadd’s personality suddenly took a dramatic shift. The painter was suddenly agitated, violent, and his words became increasingly nonsensical, loosely threaded together with ramblings about Egyptian gods. It was said he was suffering from sunstroke but Phillips was afraid of his traveling companion and they eventually parted ways with Dadd returning home in the spring of 1843. When he returned home he got out of the sun, but his unsettled mind did not dissipate. He was diagnosed with having an “unsound mind” and he and his family relocated to the rural village of Cobham hoping the change in scenery would right Dadd’s mental anguish.

Self portrait of Richard Dadd, 1841.

The family had hopes but on the evening of August 29th 1843 the seriousness of Dadd’s mental state became crystal clear. After convincing his father to go for a walk with him in Cobham Park the young artist snapped and attacked, first punching his father in the head, then unsuccessfully slashing his throat before finally stabbing him in the chest killing him. When the deed was done Dadd raised his arms and yelled to the sky “Go, and tell the great god Osiris that I have done the deed which is to set him free.” He fled the park and began on what he felt was his next mission, to get to Europe and kill Ferdinand I, the Emperor of Austria. He didn’t make it to Austria, but he did get to France and almost killed another person with a razor along the way. August 30th 1843 was Richard Dadd’s last night as a free man. He was arrested and confessed to murdering his father.

If anyone was hoping for clarity once Dadd was arrested they were severely let down once he began explaining his actions. According to the painter, his father was an evil stand-in, the devil, his real father was the Egyptian god Osiris, and he was following instructions to kill this impostor. In his own words, Dadd was “the son and envoy of God, sent to exterminate the men most possessed with the demon.” Upon his arrest he was held in the French asylum at Clermont for ten months before he was finally taken back to England where he faced trial and was committed to the criminal wing of the Bethlem Royal Hospital, now notoriously known as Bedlam.

The exterior of Bethlem Royal Hospital circa 1828.

The image of Victorian-era asylums is often one of cold stagnating cruelty, but it was during his commitment that Dadd began to truly flourish. Hospital reports tell of a man that remained incoherent and delusional with one report from March 21, 1854 stating that “For some years after his admission he was considered a violent and dangerous patient, for he would jump up and strike a violent blow without any aggravation, and then beg pardon for the deed.” But, still able to somehow draw on his artistic past, he was given supplies and encouraged to paint. He threw himself into it with all of his being. Here in the asylum he was free from the opinions and constraints of the fine art world that bred him, here he was able to paint and create his own unfiltered works, a direct line into his deeply scarred mind.

The subject matter of his work ranged from those directly in front of him to intensely intricate fantasy worlds. In 1852 he painted a portrait of his doctor which now hangs in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and it was in the 1850s that he began painting a series of thirty-three watercolor drawings titled Sketches to Illustrate the Passions. These pieces, with titles that run the spectrum of emotion including Pride, Love, Jealousy, Disappointment, Agony-Raving Madness, and Murder, offer their viewer a totally unhindered glimpse into the perceptions of Dadd regarding human emotion, and quite possibly the difficulty he had processing his circumstances.

Dadd’s portrait of his doctor Alexander Morrison, now belonging to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Agony-Raving Madness by Richard Dadd, 1854.

In 1855 Dadd began work on another project, the precisely executed and unbelievably intricate The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke. Meticulously rendered in nearly 3D realism, the painting depicts the actions surrounding the feller about to cleave a hazelnut with his ax to provide a new carriage for Queen Mab. This was not the first time Dadd painted the fairy world, but this work stands out from his previous projects. The style is markedly different and The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke was actually painted for the head steward at Bethlem Royal Hospital, George Henry Haydon, who was deeply impressed by Dadd’s artistic ability and requested a fairy painting of his own. The painter worked on the scene diligently for nine years, inscribing the back of the canvas with the words “The Fairy-Feller's Master-Stroke, Painted for G. H. Haydon Esqre by Rd. Dadd quasi 1855–64.” Even after nearly a decade of work, Dadd considered it an unfinished piece with the background of the lower left corner left only sketched in. Today The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke is considered to be Dadd’s masterpiece.

The Fairy Fellers' Master-Stroke. 1855–64. Oil on canvas. 54 × 39.5 cm. Tate Gallery, London.

Although it was never clearly stated, a possible reason why this work that Dadd spent nine years on was left incomplete may lay in its “finish” year of 1864. It was in this year that Dadd was transferred to a new facility, Broadmoor, Britain’s first hospital for the criminally insane. Although he never revisited the fairy feller with a brush, the scene and its players remained in Dadd’s mind well after he entered the gates of his new home in Broadmoor. The artist took up a pen and in January 1865 he completed Elimination of a Picture & its Subject—called The Fellers' Master Stroke, an elaborate written account where each character inside his painting is given a name and a role in an accompanying story infused with references to Shakespeare and British folklore.

Dadd would never see the outside of Broadmoor. In his twenty-two years inside its walls he never expressed regret, never apologized for killing his father, and never escaped his delusions. As documented in notes taken inside the hospital during his care, October 24th 1865 reports “No change” and even thirty-four years after murdering his father he still spoke of the need to set Osiris free. And yet, despite his deep illness he painted constantly, his ability to take the images from his eyes and mind and masterfully bring them to life never leaving him.

Richard Dadd painting while institutionalized.

Painting until he physically could no longer manage the task, Richard Dadd died on January 7th 1886 “from an extensive disease of the lungs” which was more than likely tuberculosis. He was sixty-eight years old and had spent forty-two of his years committed to an institution. He was buried in the Broadmoor cemetery.

After his death Dadd remained nearly unknown until the 1960s and 1970s when his work experienced a revival, fueled by his story and the ability to portray him as the epitome of the tragic artist. His story and the recognition of his astonishing talent has carried him through the decades and today some of the many works of Richard Dadd have found homes at a number of prestigious art institutions including the Tate Britain, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

Looking at pieces like The Fairy Fellers' Master-Stroke can invoke images of charming whimsy and pure fantasy, a stark contrast to its origin story involving a brilliant mind turned to madness, murder, and the cold walls of Broadmoor.

You can read the full text of Elimination of a Picture & its Subject—called The Fellers' Master Stroke (1865) here.

#HushedUpHistory#featuredarticles#history#arthistory#BritishHistory#BristishArt#Britisharthistory#Faries#FairyArt#RichardDadd#TrueCrime#FamousMurder#FamousBritishCrime#art#BritishPainters#Britishmedicalhistory#Bedlam#BedlamAsylum#Broadmoor#asylum#artist#painter#madness#tragictale#tragedy#torturedartist#artstories#storybehindthepainting#famouspaintings#FairyFellersMasterStroke

0 notes

Text

Richard Dadd, Portrait of a Young Man, 1853

10 notes

·

View notes