#dutch chintz fabric

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Beige Chintz Dress, ca. 1780, Dutch.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#beige#Chintz#cotton#womenswear#extant garments#dress#1780#1780s#1780s Netherlands#1780s dress#1780s extant garment#V&A

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since spring is here

My favorite thing about making a fan concept of Dmtnt musical adaptation is the flowers/spring symbolisms

Costumes

I realized that some of my costumes have floral details.

I will use these three as examples

Daffodils on Will's coat symbol of new beginnings

Cherry blossom on Elizabeth's vest symbol renewal, new beginnings, and rebirth

Most of Carina's costumes are floral pattern designs.

This pattern is called chintz

This pattern has several details and it shows Carina's true character

Red details of chintz shows Carina's suffering

And butterfly symbol of growth. Same goes to flowers. Flowers had a lot ot symbolisms. Carina's character development is like a flower

Bird details shows that she's free like a bird

Fun fact: did you know chintz was banned by British parliament in first half of 18th century due to economic concerns of trading chintz fabric from India.

Spring Uprising

The name of the event of the show Spring Uprising is about resistance against tyranny and oppression.

The season of spring is the symbol of new beginnings

A lot over revolutions like American Revolution wanted to start new beginnings after British rule of America

A lot of revolutionists using flowers as symbol like red carnation.

Daisy as a symbol of resistance that was actually used in Dutch resistance against occupiers. I find out that's perfect to use this flower for my concept

Crystal

The Crystal was replaced from Poseidon's trident in my concept

If you're a Sailor Moon fan, you know the legendary silver crystal.

I've drawn inspirations from that magical crystal

The Crystal is a shape of a lotus flower. Lotus is the symbol of rebirth and resilience

The musical of Dmtnt will be about resistance and new beginnings

#dmtnt musical#pirates of the caribbean#potc#dmtnt#dead men tell no tales#carina smyth#will turner#elizabeth swann

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

there is a Japanese word for chintz (as in the fabric), namely 更紗 (サラサ sarasa), which comes from Portugese saraça.

my dictionary does not have an etymology, but the use of a kanji transliteration and the Portugese link suggest it could date back to the brief period in the 1500s when Portugese traders visited Nagasaki and even briefly held a lease on it. that ended when the Tokugawa government, which had just emerged as the victor of the Sengoku period, became convinced that these traders were the first wave of a European invasion. they suppressed Catholicism in Japan and banned all foreign visitors except the Dutch, who were only permitted to land at Nagasaki.

(I think more precise history could probably be gleaned if I spent some time translating the linked JP wiki article, which is decently long.)

the history of chintz in Europe is not the same of course, but there is a slight similarity in that as imported 'calico' fabrics became popular, countries like England and France moved to ban them (with certain loopholes). but the connotation of 'tacky, tasteless' doesn't carry over I'm pretty sure.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been really warm here, so I needed to feel cool for a bit. I made an 18th century wrapping gown out of this beautiful Dutch chintz fabric a while ago and could not feel any cooler.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Vlisco Group designs, produces and distributes fashion fabrics, especially of the African wax print style, for the West and Central African market and African consumers in global metropolitan cities. Founded in Helmond, the Netherlands, in 1846, the Vlisco Group and their fabrics have grown into an essential part of African culture, receiving widespread attention from the art, design and fashion worlds. Vlisco Group's brand portfolio consists of four brands: Vlisco, Woodin, Uniwax and GTP. The company's head office, as well as the design and production facilities for the Vlisco brand, are located in Helmond. For the other brands these facilities are based in Ghana and Ivory Coast. The Vlisco Group has eight sales offices in numerous African countries and around 2,700 employees (900 in The Netherlands and 1,800 in Africa).

History

Vlisco textile with crystals

Vlisco Group was founded in 1846, when Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen bought an existing textile printing factory and named it P. Fentener van Vlissingen & co., aiming to produce and sell hand printed fabrics in- and outside of the Netherlands.[1]: 27 Originally, production included handkerchiefs, bedspreads, chintz and furniture fabrics. In the second half of the 19th century, Fentener van Vlissingen started exporting imitation batiks to what was then called the Dutch East Indies after he was told by his uncle that there was a pressing need for affordable fabrics. Thanks to the invention of roller printing, it was possible to recreate the batik look a lot less labour-intensively, which meant that Fentener van Vlissingen could produce it quicker and sell it cheaper than local craftsmen could. This was also its only selling point, as the Indonesians did not care for the too even look of the imitation batiks.[1]: 28–30

That Fentener van Vlissingen's fabrics came to West Africa is rather logical. Once the Dutch East Indies banned imitation batiks, Fentener van Vlissingen had to search for a new market to sell his goods. Since the start, the company has produced and sold hand-printed textiles both domestically and abroad. Around 1852, the VOC Dutch East Indies trade routes became involved in the export of the hand-printed Vlisco fabrics. The fabrics were used for bartering during stopovers in Western Africa. Since the Dutch had been dealing in European luxury goods with West-Africans since the Late Middle Ages, it seemed a logical step to move selling activities to that region. Another reason is that the fabrics sold in Indonesia had become popular among the Belanda Hitam, Ghanaian soldiers who served in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army and returned home between 1837 and 1872.[1]: 30

By the time the 20th century rolled around, West- and Central Africa were growing into a booming textile market and by the 1930s the 'wax hollandais' cloth's designs were being adapted to local tastes.[2]

In 1927 the company changed its name to Vlisco, a contraction of Vlissingen & co., but the fabrics were by then widely known as 'Dutch Wax' or 'Wax Hollandais', and those names stuck. During World War II, production was stopped and the finished fabrics could not be shipped to the African markets. The African fabric markets were starved of Dutch Wax for the entirety of the war and when in 1945 Vlisco managed to send a shipment of a fabric called 'Six Bougies' , it was an immediate success.[1]: 30 So much so, that from 1963 onwards, all Vlisco fabrics have the text 'Guaranteed Dutch Wax Vlisco' stamped on the side, because the fabrics were and still are widely counterfeited.

Unlike the Vlisco brand, the entire process – from design to production and distribution – for the Woodin, Uniwax and GTP brands takes place in Africa. When, in the mid-1960s, the import duties on printed textiles were doubled in several Western African countries, a percentage of imports were replaced by local production. This led to the establishment of the GTP (Ghana Textiles Printing Company) brand in 1966, with production taking place at a factory in Ghana, and the establishment of Uniwax in 1970, with production facilities in the Ivory Coast (Koert van, Robin, Dutch Wax Design Technology: van Helmond naar West-Afrika, 2008). The pan-African brand Woodin has been produced in both the GTP and Uniwax factories since 1985. Furthermore, Vlisco made a historical decision in 1993 by abandoning hand printing, to be able to produce fabric on a larger scale.[3]

Over time, The Vlisco brand has developed a highly sophisticated production process, whereby the fabric goes through 27 treatments, both by machine and by hand, and takes two weeks to produce. This process is a closely guarded secret. Since 2006, the company has been aiming at high end markets and is currently preparing to release a ready to wear fashion line.[4]

The Vlisco Group carries four brands: Vlisco, Woodin, Uniwax and GTP. Each of these brands has its own style, brand identity and consumer target group. Four times a year, the Group launches a new collection of fashion fabrics under their premium luxury flagship brand Vlisco, designed and produced in Helmond. Since it was established in 1846, Vlisco designs and fabrics, have grown to become an essential part of African style culture, with deep-rooted influences across all layers of society. Uniwax and GTP are designed and produced in Ivory Coast and Ghana and focus on the growing middle class in West and Central Africa. Woodin is the smallest, but fastest-growing brand in Vlisco Group's brand portfolio. At this moment, 60% of the population in West- and Central Africa is under 25 years old. This segment is growing, extremely connected via social media and mobile devices and show fast changes in consumer behavior regarding to lifestyle, fashion and media usage. The lifestyle brand Woodin focusses on this consumer group.

Postcolonial criticism

Critics, such as Tunde Akinwumi, feel that Vlisco's origins are misleading, especially since the company profiles itself as the 'originator of African Wax'. Akinwumi's 2008 article, 'The "African Print" Hoax', argues that producers of African prints mislead customers by pretending to sell authentic African designs, while they are in fact based on Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Arabic and European imagery. Therefore, he advocates a new African aesthetic, based on traditional African fabrics, such as kente, adire, aso oke and bogolanfini, and expresses hope that textile producers and governments will support this cause and help change Africa's image to a more authentic one.

In his book Vlisco, Jos Arts, however, represents the counter critics, who are of the opinion that critics like Akinwumi have misunderstood a main principle of fashion, namely that it is subject to constant change and therefore even though Vlisco's fabrics were initially not authentically African, the century-long process of appropriation and mutual influence ensures that it has become so.[5]: 92

In the realms of art, Vlisco fabrics are extensively used by British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, who dresses headless mannequins in baroque gowns and suits, to challenge Western colonial history.[5]: 10

Symbolism

Vlisco fabrics are given an interesting form of symbolism, which allows African women to speak out, yet stay silent. Once a fabric has been designed and shipped, it is given a name which often ties into local sayings by the saleswomen. An example of this is a fabric with a print of open bird-cages and two birds flying out, that goes by the title "Si tu sors, je sors" (You leave, I leave), which means to say "If you think this marriage is something you can take and leave as you please, I will do the same." Other fabrics are known as 'Come to my bedroom wearing your slippers' or 'Kofi Annan's brain". What is important to consider in all this is that this kind of symbolism is only possible both because the messages are open to multiple interpretations and the fabrics are worn as dresses, and no one can divorce or attack a woman for wearing a pretty dress.

1 note

·

View note

Text

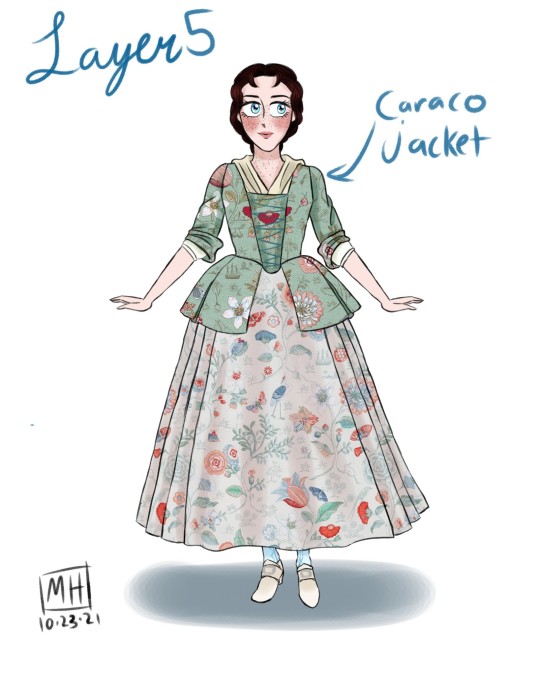

M-P Goes all Crafty : WIP - The "Chintz in Bloom" Francaise

Pic heavy below the cut!

Hello again, friends! I thought I'd update with a few picture of my progress on the "Chintz in Bloom" robe francaise I'm currently making.

This hasn't gone as quickly as I would have liked, but that's namely down to one thing: the weather. It's been so darn hot this summer that even the thought of sitting in front of a warm sewing machine has made me want to melt into a puddle - so progress has definitely been restricted to 'when I can bear to machine-sew.'

I also ran into a difficulty that meant it took twice as long because of the fabric I'd used. If it had been silk, I wouldn't have needed to line the overgown - but, for my sins, I used cotton print. And I wanted to be able to pull the skirts up through the pockets, like this, to turn it into a walking dress AS WELL as an elegant formal gown.

Problem is, if you do that with an unlined quilting cotton, you get the ugly plain underside punched up through the pocket slits, which makes it just look... unfinished, and kinda cheap looking. . I still wanted that beautiful deep red! So, back to the fabric store to find a deep burgundy cotton lining that matched - and close enough that it wouldn't clash with the print. But the result is looking nice.

I've also added a lovely pink and burgundy fly- trim to the edge of my cotton ruffles. This wasn't on the original gown's trimmings; but as my fabric has a smaller, busier pattern than the original silk, the ruffle on the petticoat just wasn't showing up, and I wanted it to stand out a bit.

You can now see the trim much better - and I think when it's added to the sleeves and stomacher as well as the side of the overgown, it should look very nice and appropriately 1760s.

- hearty thanks to @tockamybeloved and her own beautiful silk creations, by the way - I'd have never have got up the courage to make a robe francaise without you!

#mp goes all crafty#wip#my sewing#my historical costuming#my 18th century sewing#18th century sewing#historical costuming for fun#robe francaise#work in progress#chintz:cotton in bloom#chintz gown#dutch chintz fabric#sacque gown#sack-back gown#watteau gown#robe a la francaise#18th century fashion#18th century style#rococo#18th century styling

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I remain so amazed that Indian cloth was such a desirable and much-traded item that it became a staple of local folk dress in the Netherlands! Of course, chintz was popular in many places, but it's so fascinating to me that it took on this very local character here.

The Cloth that Changed the World: India’s Painted and Printed Cottons

Now open at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, ON and running through September 6, 2021 is a show that reminds us that global trade is nothing new although its latest developments often surprise us. This show traces cotton cloth made in India and traded around the world all over Asia, Europe, and the Americas. You see here a photograph of a woman’s jacket which made in southeast India and worn in Hindeloopen, Friesland in Holland in the 18th Century. Such a lively pattern and such a long way to travel.

The curators tell us that the show “explores how over thousands of years India’s artisans have created, perfected and innovated these printed and painted multicoloured cotton fabrics to fashion the body, honour divinities, and beautify palaces and homes.” And they come all the way up to the present day.

If you can’t make it, there is a book, plus multiple features on line for you to enjoy with images and more.

For more information and tickets, go here: https://www.rom.on.ca/en/exhibitions-galleries/exhibitions/the-cloth-that-changed-the-world-indias-painted-and-printed

#chintz#sits#fabric#fashion history#fabric history#indian printed cotton#dutch regional dress#frisian costume#dutch clothing

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

I got inspired by the Indigo exhibit at the Albuquerque museum, or more accurately my annoyance at their absolute lack of any mention of chintz in the Indian part of the exhibit, given what a central rule chintz and the European colonial thirst for it, played in the colonization of India, and the textile industry there on out. Like, if you're going to talk about the role of Indian textiles in the brutal colonization of India, and famines in the subcontinent, and you don't talk about chintz, it's a really major omission.

But anyway, since I was thinking about chintz and colonialism, it's natural that my mind turned to the American colonial period. And, shoving the brutality of that project aside, much as I am shoving aside the brutality of the process of acquiring chintz in the first place, I designed some 18th century printed cotton jacket and skirt combinations that would have been worn by middle class and relatively well off women in the English colonies as everyday wear. Initially, in in the late 17th and early 18th century, chintz, which was both from very far away, and also labor intensive to produce, highly skilled labor intensive at that, was an extremely expensive trade good, and might serve as a wealthy woman's best best dress. But as the century wore on, slave plantations in the colonies began to produce cheaper cotton, and imitation chintzes began to appear, the price came down. Nonetheless, chintz and other printed cottons remained extremely fashionable, and I would go so far as to call it the it fabric of the 18th century.

The primary influence on colonial American fashion in the English colonies, was of course English fashion, and English preferred light colored and white background floral chintzes, with relatively small patterns, and so three of these jacket and skirt combinations fit that pattern. However, there was another more localized influence on American colonial dress, in the former Dutch colony of New York, where some of the Dutch influence remained. The Dutch went wild for chintz with red backgrounds, so I included one skirt of that type. I have to confess it's my favorite.

All four jackets have low necklines filled in with a kerchief, as was fashionable at the time, and all four open in the front, and would have been pinned closed with small straight pins which would have attached the edges of the jacket not only to each other, to the wearer's stays, which at the time, were used to give women a flat fronted, somewhat conical shape.

And a bonus, I made American girl doll Felicity's original school outfit, which is also the same kind of jacket/skirt combination, though it has a higher neckline, and laces up the front instead of being pinned.

Codes:

My creator code: MA-1880-6637-0176

Blue: MO-5P4Y-M4NK-JF32

Red: MO-WXRF-T1NG-2M61

Green: MO-CNDT-8PVG-10SL

Dutch red and blue: MO-4N5G-T77R-GXBF

Felicity's school outfit: MO-LCB2-GV8V-8K67

14 notes

·

View notes

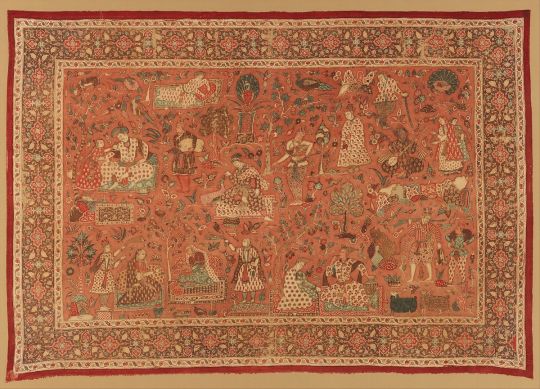

Photo

beautifull #Palampore from Coromandel Coast, 1720-1750 this was for Dutch market? many such Textile fabric designed & exported to Europe from India with fame came rivalry & in UK once #chintz was banned Though छींट is often heard word but real is not popular in India at present, I guess? Given by G. P. Baker at @V_and_A https://t.co/IZYZvVWDAI https://www.instagram.com/p/CVdOdlkhltD/?utm_medium=tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Carina’s dress 2.0

Here’s the another outfit with a calico jacket for my first redesign

Calico jacket that both lower and middle class women wear in 18th century as an everyday jacket. The combination of jacket and petticoat were at least common in that time. They like to mixed and match the outfit.

Chintz fabric was popular in Europe in late 17th and 18th century. They were imported from India. Chintz was often used for curtains, furnishing fabrics, and bed hangings and covers. It suggested that wearing chintz as clothes began when chintz fabrics were replaced and given to maidservants, who handmade their dresses from chintz and also, they were first worn as linings

I took inspirations from the Dutch women’s fashion in 18th century. Bc Dutch women’s fashion are mostly chintz.

Ex

I headcanon Carina look up the fashion plates of Dutch ladies wear these. She thought she find them more appealing to her. So, she copies and dressed like a Dutch woman rather than an English woman.

#pirates of the caribbean#potc#carina smyth#carina barbossa#max draws#potc redesigns#I accidentally delete this while tried to rb and thers so much error ugh#and i repost this

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

D'Artagnan

"Clothing for children and infants in mid to late 18 century

#1 Infant's dress with a pattern of delicate floral sprays in blue, red, lavender, and brown on white. The skirt is gathered into a yoke, which has a draw-string neckline, with short sleeves; open down the back.

Made in .Indian late 18th century cotton mordant paired and dyed technique is mordant painted and dyed and resist dyed (chintz) on plain weave © Cooper Hewitt

#2. Swiss child's dress, possibly for a one to two year old, linen with floral embroidery, Basel mid-18th century. © HMB museum CH

#3 Dutch dress monohrome Indian chintz made 1750- 1775, Dress made 1750 - 1775 Friesland © Regional Costumes in the Netherlands.

#4 Baby jacket , 1750-1800. From the collection: Regional Costumes in the Netherlands. . ©Nederlands Openluchtmuseum

#5 back #4 Baby jacket , 1750-1800. From the collection: Regional Costumes in the Netherlands. . ©Nederlands Openluchtmuseum

#6 Pair of infant shirts, made with distinct printed fabrics, are said to have been worn by Mary Arnold of Newport, circa 1776. Both shirts are made of plain weave fabrics, held together by tiny overcast stitches, and are fully lined with a fabric that is probably linen. Both also most likely employ variations of block printing, a common means of transferring designs to fabrics during the 18th century. Printed textiles became popular with the import of block-printed cottons from India, and European imitations of Indian block-printed designs and techniques followed in large quantity.Upon closer examination, both shirts exhibit interesting methods of construction; the “pieced” nature of each garment, particularly seen where patterns do not align (see details), suggests that stray scraps of fabric were used, perhaps from an older garment that had fallen into disrepair. This was a common practice, as textiles were some of the most valuable items purchased in an 18th century household.© Newport Historical Society RI

~~~ooo~~~

Eighteenth-century babies often wore shirts with an open front, which were folded across and held in place by a petticoat worn over it. A longer dress, or “bed gown,” was worn over the petticoat, and a folded cloth called a “pilcher” covered the diaper; caps, sometimes more than one, covered the baby’s head. Babies and young children also wore support garments such as stays over their clothing as it was believed to have positive healthful effects

Love D'Artagnan xxx".

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sits

Oost-West Relaties in Textiel East-West relationships in textiles

Ebeltje Hartkamp-Jonxis

Uitgeverij Waanders, Zwolle 1987, 216 pages, 93 text ill.in col. & b/w, Dutch, Isbn 978-9066300835

euro 70,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Catalogue of an important exhibition of imported chintz from the Far East by the Dutch East India Company at Haags gemeentemuseum/Groninger Museum. Description of the technical, economic, historical and cultural aspects of the cotton fabric from India and Ceylon

20/11/19

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter:@fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

tumblr: fashionbooksmilano

designbooksmilano

#Sits#chintz#indian textiles#Dutch East India Company#textiles history#textile design inspirations#textiles exhibition catalogue#textiles books#fashion history#fashion inspirations#fashion books#fashionbooksmilano

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

Architecture is suffering a crisis of confidence. More and more mainstream figures in the field are admitting that the profession has lost its way. As I previously mentioned, Frank Gehry, the world’s most famous architect, recently said that “98% of everything that is built and designed today is pure sh*t. There’s no sense of design, no respect for humanity or for anything else.” Architectural thought-leaders seconded and thirded him. And he’s since been fourthed by another.

…

And now The New York Times, the ultimate arbiter of elite opinion, recently published an op-ed that declared, “For too long, our profession [architecture] has flatly dismissed the general public’s take on our work, even as we talk about making that work more relevant with worthy ideas like sustainability, smart growth and ‘resilience planning.’” The authors are not kooks on the fringe but architect Steven Bingler and Martin C. Pedersen, former executive editor of Metropolis magazine, both of them very much in the establishment.

The authors observe that self-congratulatory, insulated architects are “increasingly incapable … of creating artful, harmonious work that resonates with a broad swath of the general population, the very people we are, at least theoretically, meant to serve.” Bingler and Pedersen note that this has been a problem for over forty years (my emphasis), and that things are even worse today.

As a case in point, they mention the 2007 “Make It Right” charity program, founded by amateur architect and furniture designer Brad Pitt. The program invited firms, most of them avant-garde, to design housing for poor New Orleanians whose homes were destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. The architecture world was exhilarated: The initiative was to be a showcase for how the best contemporary design could improve lives.

The predictable result was weird, sometimes discomforting houses of non-native motley futuristic design that have virtually no relation to each other or the beloved historic architecture of the city. A story in The New Republic called the 90-some houses a waste of money and a distracting sideshow: The homes were expensive to build ($400,000 on average) and the high-tech fabrication has made them expensive to fix; mold has grown on the untested experimental materials, and the eco-wood decks and stairs are already rotting. The neighborhoods are wastelands—failures of urban planning that isolate residents from social networks and public services.

…

While most of the architectural establishment has responded to the op-ed with noticeable silence, Mark Lamster, architecture critic for the Dallas Morning News, did bravely publish a post on Facebook in which he began by quoting the opinion piece: “We’ve taught generations of architects to speak out as artists, but we haven’t taught them how to listen.” Lamster then commented, “super-smart nyt op-ed from Martin Pedersen and steven bingler [sic].”

What is most telling, however, is the vitriolic response the op-ed triggered in Aaron Betsky. Called “one of the 21st century’s architectural power brokers,” Betsky is the former head of the Cincinnati Art Museum, and was director of the 2008 Venice International Architecture Biennale, the most important architecture show in the world. An architectural priest and patrician, he is to the profession what The New York Times is to the chattering classes: a voice of the high-status quo. Indeed, he writes for Architect, the official magazine of the AIA.

Betsky rained down on Bingler and Pedersen with ridicule and scorn: Their piece was “so pointless and riddled with clichés as to beggar comprehension.” He summarized their position: “we have three of the standard criticisms of buildings designed by architects: first, they are ugly according to what the piece’s authors perceive as some sort of widely-held community standard (or at least according to some 88-year old ladies); second, they are built without consultation; third they don’t work.”

Yet Betsky then admitted, “All those critiques might be true.” They are irrelevant, he claims, since architecture must be about experimentation and the shock of the new. (Why this should be the case he does not say.) And sometimes designers must stretch technology to the breaking (or leaking) point: “The fact that buildings look strange to some people, and that roofs sometimes leak, is part and parcel of the research and development aspect of the design discipline.” Ever brave, he is willing to let others suffer for his art.

At no point did Betsky consider the actual human beings, the unwilling guinea pigs who live in the houses. He implicitly says of the poor residents: Do their roofs leak? Let them buy buckets. And as for sickness-inducing mold, there’s Obamacare for that. Betsky also does not consider what a leaky roof means to people whose prior homes were destroyed by water. The architects, having completed their noble experiments, effectively say like the arrogant King Louis XV of France: “Après moi, le deluge” [After me, the flood]. No wonder architects have an image problem.

Betsky also would not appear to care that some of the new houses look like they have already been damaged by a flood. As he wrote in May, “Buildings under decay are much sexier than finished ones, perhaps because they remind us of our own mortality.” It logically follows that the “decaying” Katrina houses are simulated ruin porn, a pleasing mix of sex and death. He had previously said that the decay of New Orleans even prior to the hurricane could seem “elegant” to some. One of his favorite architects, the Dutch firm MVRDV, proposed a Make It Right house that looked like a trailer broken in two, and another one that looked like a house piled on top of a house.

…

Modernist architecture, like Modern art, has tended to be a revolt against bourgeois taste (and values): If granny, abuelita, or bubbe is for it, they’re against it. But if bourgeois taste is bad—all that chintz and those lace curtains, those cushy sofas, that flag flown from the front porch—just imagine what architects think of the working class and poor. If the architects had their way, elevator music in New Orleans public housing would be screeching Stockhausen, not native Louis Armstrong or Fats Domino. Modernists have no room for harmony, rhythm, or soul; they are high-culture elitists, not multiculturalists who celebrate class and ethnic diversity.

Many leading 20th-century architects, including Philip Johnson and Mies van der Rohe, were openly disdainful of the public’s preferences. On occasion they evinced subtle and overt racism. In 1913, in one of the most influential essays in the history of Modernist architecture, “Ornament and Crime,” [PDF] the Austrian architect Adolf Loos declared that modern man (read: white northern Europeans) must go beyond what “any Negro” could achieve in design, and strip away all that is superfluous, all that is morally and spiritually polluted. It is Papuans and other primitives who, like innocent children, ornament themselves with tattoos. Loos’ race has superseded them: “the modern man who tattoos himself is either a criminal or a degenerate.” The same held for ornament in architecture. (To this day, architects—who continue to believe they are the vanguard of civilization’s progress—find ornament retrograde. Yet ordinary people stubbornly continue to adorn themselves with cosmetics, jewelry, and, yes, tattoos.)

In the 1920s, during the time he was a member of the French Fascist party, the seminal architect Le Corbusier said he was disgusted by the “zone of odours, [a] terrible and suffocating zone comparable to a field of gypsies crammed in their caravans amidst disorder and improvisation.” He also chimed in with Loos: “Decoration is of a sensorial and elementary order, as is color, and is suited to simple races, peasants, and savages… The peasant loves ornament and decorates his walls.”

…

Betsky, to his credit, doesn’t pretend that architects should even try to make outreach. Showing little sympathy for democracy, he says that appeals to the public are “mystical.” The people—the 99%—do not deserve a seat at the table. Yet Betsky would have us believe that he and the architecture he supports are “progressive.”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silks Through the Silk Road

by Kishore

The Silk Road earned its name from Chinese silk, as it is a highly demanded commodity that merchants transported along these trade routes. The increased political stability and advances in technology caused an increase in these trades.

Silk Road is an ancient and historically important trade route, through which carpets and other textiles from various parts of Asia have been traded. It promoted commerce and travel between India, China, Central Asia and Europe, and fostered cultural interaction. By the 15th century, the Western world was interested in Oriental carpets made in major carpet-weaving centers in Turkey and exported them to Europe and then to America.

Carpet with Palm Trees, Ibexes, and Birds

late 16th–early 17th century

Silk was considered to be one of the most luxurious commodities traded along the many routes of the Silk Road. But Silk was not the only one traded and silks were not the most important of all exchange goods.

Since the 19th century, archaeologists have discovered textile fragments which were made of fibers such as cotton and wool from places around the Taklamakan Desert in Central Asia.

Even though silk was indeed highly demanded and frequently traded ware that lends the Silk Road its name, clothing and fabrics that are made from other materials were also exchanged along these routes and established a part of the broader network of cross-cultural interactions which took place within the field of textile production and design.

“To follow the Silk Road is to follow a ghost. It flows through the heart of Asia, but it has officially vanished leaving behind the pattern of its restlessness: counterfeit borders, and unmapped peoples. The road forks and wanders wherever you are. It is not a single way, but many: a web of choices.”

- Colin Thubron

Types of wool traded through the Silk Road:

Felted wool: It was said to be used in making clothes and furnishing, such as carpets, saddle blankets and hats for both aesthetic and functional purposes.

Woven wool: Generally woven fabrics were stronger and thicker than non-woven fabrics. These were used in making sweaters, curtains etc.

Trade of Indian textiles through the Silk Route:

Spices and textiles were the principal commodities in the International commerce of the pre-industrial era. India is particularly known for the quality of its textiles. In 1600 the British East India Company received its charter, and two years later the Dutch East India Company was also founded. These agencies purchased textiles in India for gold and silver, exchanged them for the spices grown in Malay Islands, and sold these spices in Europe and Asia. Soon the Indian textiles were exported directly to Europe, where they had become highly popular. Some of the Indian textiles even got their names translated into English: Calico, Pajama, Gingham, Dungaree, Chintz, and khaki.

Man's Robe (Jama) with Poppies

Production of Indian textiles:

Fabrics: Wool, cotton, and silk are the three materials from which textiles are woven. Cotton plants are grown in many regions of India, where black soil availability is higher. Wild silk moths are the source of silk, which is mostly found in the central and northeastern parts of the country. The fleece of mountain goats and sheep raised in cold regions like Kashmir, Ladakh, and the Himalayas- is spun into wool.

Dyes: Being obtained from the plants and minerals native to the subcontinent, dyes are mostly available in red, blue, violet, green, yellow, and black. The blue shades were obtained from the Indigo plants which are processed and traded in the form of dried cakes. The yellow color is obtained from turmeric and black is made by mixing indigo with an acid substance such as tannin. Purple and green are made by layering yellow dyes over blue cloth.

Printing, resist dyeing, and painting: Mordant is a metallic acid, which is used as a fixative agent to combine with dye and bond onto the fiber. These mordants are also used to create patterns. Resist dyeing, also known as Batik by the Malay term.

Kalamkari: Literally it means “pen-worked”, this is a multi-step process for creating designs. At first, the cloth is stiffened by being steeped in buffalo milk and astringents and then it is dried in the sun. The black, red, brown and violet portions of the designs are outlined using a mordant, and the cloth is placed in a bath of alizarin. After that, the cloth is covered with wax, except for the parts which are to be dyed blue, and is placed in an indigo bath. Then, the wax is scraped off and the areas to be yellow or light colors are painted by hand.

Kalamkari Rumal

ca. 1640–50

Kalamkari Hanging with Figures in an architectural setting

ca. 1640–50

Weaving and Embroidery: Different patterns can be created in the process of weaving, mostly with silks. The weft threads are woven onto the loom, they combine with the warp and make patterns of extraordinary density and complexity. Another speciality of India is embroidery, in which a decorative needlework pattern is sewn onto the fabric.

Indo-China Trade:

The two Asian giants, India and China, share vast similarities in terms of history and culture. Both countries represent their unique history and old-age civilizations. The Silk Route, which is the earliest network of trade routes, served as a connection between India and China. Buddhism also spread to China and East Asia from India, through these routes. The routes were more than just trade routes, it was the carrier of innovations, inventions, discoveries, ideas and myths.

0 notes

Photo

Mario Buatta “My parents’ house was all 1930s modern, and I hated it. I spent all my time with my Aunt Mary, who was a true “Auntie Mame.” She had a wonderful house full of Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and chinoiserie furnishings, and she also had seasonal chintz slipcovers. I’ve loved the look ever since.” - Mario Buatta, Designer and the undeniable “Prince of Chintz”. Mario Buatta’s first antique, he often recounted, was an 18th-century lap desk (other accounts identify it as a Sheraton box); it cost the 11-year-old Buatta $12, and his father insisted that the relic, paid for in instalments, be fumigated before his son brought it indoors. Buatta had a hunger for gilt-framed portraits of dogs, ‘Delft’ ceramic jars and hand-painted botanical cushions by George Oakes. Not for nothing would he become the longtime chairman of the ‘Winter Antiques Show' (now the ‘Winter Show’) a sleepy event that he transformed into a high-society extravaganza akin to Paris's ‘Biennale des Antiquaires’ - and also be nicknamed the “King of Clutter”. An early influence on Buatta’s taste was his mother’s sister, Mary Mauro, who lived near the Buatta’s in a house that had been outfitted with floral fabrics and 18th-century English and French reproductions by a decorator at Manhattan’s ‘W. & J. Sloane’ department store. Old houses had fascinated Buatta from childhood - especially Staten Island’s historic Alice Austen House - an 1840s Gothic Revival remodel of a Dutch Colonial residence. Though he was encouraged at one point to become an architect, even going so far as to enrol in ‘Cooper Union’ he dropped out when his mother died at the age of 47. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWXyiTRgtAv/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Work In progress: The "Cheery In Chintz" Robe a la Francaise Project...

Hello again, friends!

With lockdown rules yo-yoing around in my area, not entirely sure if I'll get to wear this any time soon outside an impromptu photoshoot in my back garden - but what the hey, I'll share my plans any way!

There's a delightful exhibit on the history of 18th century Dutch Chintz going on display at the London Textile and Costume Museum later this year, organised by no less than the Fries Museum from Leeuwarden!

A bunch of my fellow 18th century costumers invited me along to attend in 18th century dress - ideally, of course, in chintz, to pay homage to the historic prints on show.

But after looking through my wardrobe...alas, I HAVE no floral cotton gowns to wear!

So yes, that's right, there's another project in the works...

This above delightful silk robe francaise from the Mint Museum has LONG been on my 'to make' list, because that rich red wine colour is just divine (and the talented @tockamybeloved has been really inspiring me with HER fantastic robe francaises from the American Duchess pattern. But I never thought I'd find a fabric that would come close, until i stumbled across this delightful Dutch Heritage reproduction cotton print:

Best yet, it IS an 18th century reproduction print, made by a Dutch company - so I'm honouring the historical Dutch prints by wearing a modern one. There's a really nice symmetry to that.

Not quite the same, and a tad busier (and cotton, not silk), but absolutely PERFECT for paying homage to the exhibition. Plus, cotton will be nice and cool if it's still warm when we plan to attend. If it's outrageously warm I may wear the chemise gown, but this is a nice compromise for if it's a little cooler.

We'll see how it goes - I'll post pictures as I travel along in the making process!

#mp goes all crafty#craft project#my sewing#rococo#robe francaise#historical sewing for fun#historical sewing#historical costuming for fun#historical costuming#18th century sewing#18th century costume#18th century style#18th century fashion#mint museum#chintz:cotton in bloom#fries museum#london textile museum#am i insane? possibly

16 notes

·

View notes