#dryfarmed

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

#knowyourfarmer @dirtygirlproduce #dryfarmed #earlygirltomatoes #yesplease #organic #tomatolove #octoberstyle #inseasonnow #lifedoesnotsuck (at Ferry Building Farmers Market) https://www.instagram.com/p/B3h_SzMn8Ds/?igshid=12u0uzwwhyj8o

#knowyourfarmer#dryfarmed#earlygirltomatoes#yesplease#organic#tomatolove#octoberstyle#inseasonnow#lifedoesnotsuck

1 note

·

View note

Photo

@ClineCellars 2016 Ancient Vines Mouvèdre Rosé (SRP $17): What better way to beat the summer heat than with a splash of this dry rosé from Cline Family Cellars. Made from century-old, dry farmed Mouvèdre grapes, this rosé is made from fruit grown on historic Oakley vineyard picked specifically for this wine — i.e., not the by-product of red wine production. Salmon-pink in color with cooper hues, flavors of fresh red berries complement notes of white stone fruit followed by a delicate jolt of peppery spice. A tasty refresher for summer day fun: be it poolside, beach, picnic under a shade tree, or backyard cookout. Other info: ABV 13%, screw cap enclosure. To learn more, visit their website clinecellars.com. #ClineCellars #dryfarmed #Mouvèdre #rosé #drinkpink #ContraCosta #wine #wineblogger #winewriter #winelover #myvinespot

#clinecellars#winelover#dryfarmed#drinkpink#wine#mouvèdre#wineblogger#rosé#myvinespot#contracosta#winewriter

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

11 year-old #Gravenstein on #P18. #dryfarming #notill #nospray #organicorchard #vulturehill https://www.instagram.com/p/CLvRuCJlVPm/?igshid=191dial1mwxx1

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dry Farms Wines produces wine that is both natural and healthy, as well as delicious. You should get sugar-free and low-alcohol wines to keep your wellbeing as good as possible. So grab the 15% Off on Dry Farm Wines Discount Code

0 notes

Photo

Finally a wine that fits the KETO lifestyle. The @seccowineclub team recently … Finally a wine 🍷 that fits the 🍳KETO 🥓lifestyle. The @seccowineclub team recently launched an absolute game changer with PALO61 wines (red, white and rose).

#ad#aseccowineclub#atkinsdiet#banting#dryfarm#familyownedwinery⠀#finally#fits#healthywine#Keto#ketocommunity#ketodiet#ketofam#ketogenic#ketogenicdiet#ketogeniclifestyle#ketolife#ketosis#ketowine#lifestyle#lowcarbdiet#lowcarbfeed#lowcarbfood#lowcarblife#lowcarblifestyle#lowcarbliving#lowcarbs#naturalwine#nosugarwine#organicwine

0 notes

Photo

Look who we caught up with at the #Phoenix #SkyHarbor airport! It’s the famous #Hopi #farmer - #grower @sueksek Follow her amazing @instagram account. #farming #dryfarming #Arizona (at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport) https://www.instagram.com/p/BvkotzMH79m/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=8zezu9wgmeup

0 notes

Photo

Look who we caught up with at the #Phoenix #SkyHarbor airport! It’s the famous #Hopi #farmer - #grower @sueksek Follow her amazing @instagram account. #farming #dryfarming #Arizona (at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bvkol9cny3i/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1pgqd92ogkjkl

0 notes

Photo

Statice/ bachelors buttons/ strawflower lookin' good if you ignore the weeds. These guys have only been watered once since getting transplanted and I'm quite impressed that they're still showing no signs of stress. They'll be used in garlic braids, garlands, everlasting bouquets, wreaths and smudge sticks this fall when I have time for fun things like that. #sunandbeefarm #dryfarming #flowerfarm

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thinking about bugs and prairies today, as one does. Still impressive, to me, that ecological imperialism, Indigenous dispossession, unsustainable agriculture, and soil degradation was so intense that a single species of insect could go from a population of trillions during one summer, darkening the sky across the entirety of the Great Plains and potentially weighing 28 million tons, to completely extinct less than 20 years later. (The specific reason for the sudden extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust is, famously, still a mystery, though.) Like the passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, and American bison, the locust is a famous casualties of US imperial expansion of the 19th century. I know that the locust swarms of the 1870s are already well-known from their portrayal in media at the time and in popular fiction in later decades, but it’s the ecological relationships of the locust which still fascinate me. It’s unclear to what extent riparian deforestation and local bison extinction affected the locust.

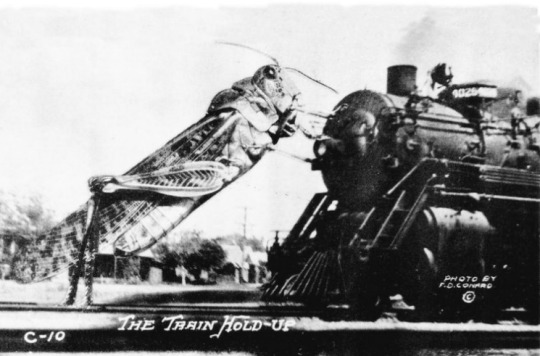

Here, Rocky Mountain locusts are depicted as a manifestation of ecological resistance against homesteading and settler-colonial industrial agriculture.

The “The Train Hold-Up” is an 1870s photo graphic dramatizing how locusts were interfering with empire’s resource extraction and westward expansion, with a photo by F.D. Conard.

The cartoon grasshopper-man comes from 1875, and is held at Kansas State Historical Society.

The cartoon is a depiction of the locust swarms of 1874-1875; by artist Henry Worrall, via Kansas State Historical Society.

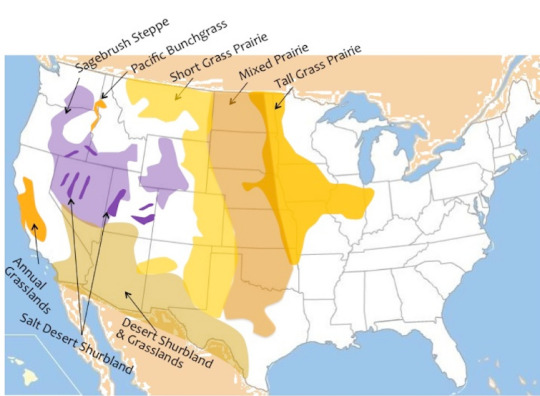

[Photo of Rocky Mountain locust. Via Wikimedia, public domain. And, a map of the suspected distribution range of the species, which forms a neat outline of the combined area of the Great Plains and the sagebrush steppe of the northern Great Basin and Columbia Plateau.]

Leading up to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, there were 3 other catastrophic droughts which devastated the Intermountain West and High Plains during the Euro-American land-grabbing campaigns of the 19th century, all due to Euro-American devegetation, agriculture, and Indigenous dispossession. Environmental historians tend to distinguish the 3 events as: “the Civil War drought” of the mid-1850s through the mid-1860s; the La Nina-influenced event of the 1870s; and the late-1880s and 1890s drought with blatantly clear connections to localized bison extinction, violence against Natives, colonial homesteading, and unsustainable dryfarming practices. (The Homestead Act passed in 1862, and all 3 of these drought periods correspond with the incredible intensification of US homesteading between 1860 and the 1890s.) And during the 1870s drought, the Rocky Mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus) might have achieved its largest historical population size. In 1877, the US government established the Entomological Commission, partially to address the vast swarms of locusts which would blacken the sky. The State of Missouri legally required citizens to commit at least one day each week to killing locusts. Extrapolations at the time proposed that, in 1875, 3.5 trillion locusts covered the American West. Then, suddenly, the Rocky Mountain locust went entirely extinct, with the last living locusts collected in 1902.

[Not a bad map of grasslands, steppe, and desert regions of the US. By Karen Launchbaugh, via Wikimedia.]

An 1888 engraving held at Minnesota Historical Society, which depicts a mid-1870s swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts.

------

On the presumed ecological relationships of the locusts:

From Hopkins’s academic review of Lockwood’s Locust (2004): The Rocky Mountain locust was once the most abundant insect on the Great Plains. In years of peak populations, Lockwood calculates, its numbers rivaled bison populations in both biomass and consumption of forage. Before the plains were settled, periodic swarms of migrating locusts were part of the natural rhythm of the grasslands, particularly during years of drought. That situation had changed by the mid-1870s, however, when farmers and ranchers occupied much of the Great Plains. A drought of several years' duration triggered a massive outbreak of locusts that swept over an immense area, destroying much of the agricultural production and bringing famine to many settlers. [...]

Several theories to explain the extinction -- and one positing that the locust was still alive, masquerading as an extreme migratory form of a common related grasshopper -- were put forward over the years. [...] One of the most interesting of these theories was that the ecology of the locust was somehow linked to the great herds of bison, and that the extermination of the latter from most of its range brought about the extinction of the former. These two major and competing grazers had coexisted on the plains for thousands of years, so the idea was advanced that the bison somehow altered the ecology of the grasslands to favor reproduction and survival of the locust. Another theory was that the planting of alfalfa throughout the locust's breeding area in the latter part of the 19th century could have played a role in the insect's extinction; alfalfa, which is palatable to grasshoppers, was shown in laboratory studies to be deleterious to the growth of the insect's immature stages. [End of excerpt.]

Bison near Yellowstone, and a look at some lower-elevation sagebrush habitat. [Photo by J!m P/eaco for National Park Service.]

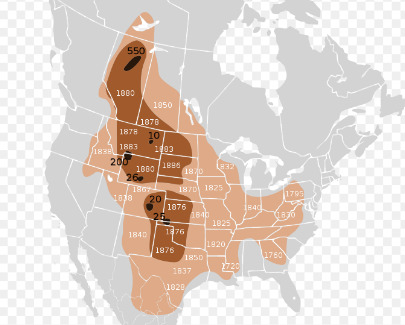

Here’s a look at the contraction of American bison distribution until 1890. [By Cephas, via Wikimedia.]

---

Some entomologists think that smaller-scale Euro-American devegetation of riparian woodlands and soils - along streams and rivers - might’ve been the major cause of sudden extinction. (Riparian corridors in dryland ecosystems like Great Basin sagebrush steppe or shortgrass prairie can be especially susceptible to damage from the arrival of Euro-American settlers and water diversion for cattle rangeland.) Lockwood and other modern entomologists have also proposed that the locust, for reproduction, relied specifically on the riparian corridors and forests of the valleys of the Yellowstone region and southwestern Montana.

A basic summary of potential ecological influences on the extinction, from the abstract of “A Solution for the Sudden and Unexplained Extinction of the Rocky Mountain Grasshopper (Orthoptera: Acrididae).” Lockwood and Debrey: Within the region that this species occupied in the late 1800s, oviposition and early nymphal development occurred almost exclusively in riparian habitats. Intensive anthropogenic effects (i.e., tillage; irrigation; loss of the beaver; and introduction of cattle, plants, and birds) were associated with virtually the entire range of M. spretus in the late 1800s. We suggest that localized agricultural destruction of the insect's habitat and the introduction of exotic species caused the extinction of M. spretus. [End of excerpt.]

Thing I did:

Riley’s illustration of Rocky Mountain locust reproduction, from a report to the Missouri General Assembly, 1874. Via University of Missouri W.R. Enns Entomology Museum.

The specific element of ecological degradation which led to extinction might technically be a “mystery,” but settler-colonial agriculture and homesteading are the clear culprits.

#my writing i guess#rocky mountain locust extinction#insects against empire#tidalectics#ecologies#multispecies#indigenous

287 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🎶I like big butts and I cannot lie...🎶 #tomatoporn #dryfarmed #bestsh$tever #lunch #youcaneattheselikeanapple #sweetasF😋 #local

0 notes

Photo

Non-irrigated vines make some phenomenal wines! Seriously.. #latinosporelvino #manhattan #organic #wine #vino #oregon #willamettevalley #eolaamityhills #eveshamwood #pinotnoir #dryfarmed #nonirrigated (at Washington Heights, New York)

#nonirrigated#manhattan#pinotnoir#willamettevalley#eveshamwood#dryfarmed#wine#eolaamityhills#vino#oregon#organic#latinosporelvino

0 notes

Photo

Two 10 year-olds. One is 5’ tall now, the other is a #Gravenstein on #P18 rootstock, dry-farmed since planting in 2010. . .#orcharding #dryfarming #vulturehill https://www.instagram.com/p/B8gquvTp17V/?igshid=14mckz9c9t8df

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dry Farm Wines Gives Us Reason To Celebrate This Holiday Season

The holiday season is all about celebrating, and we believe that the best way to celebrate is to raise a glass of special wine.

It is great that Dry Farm Wines has developed personalized gift options that allow you to send a complete selection of wines in the amount of 3, 6, or 12 bottles directly to your recipient’s door. You can also choose the option of one order or short-term monthly membership twice a month, three times a month or a month to get the maximum gift. Just choose your favorite type of wine (cabernet or rose maybe?) And choose your favorite delivery method, from quarter to monthly.

DryFarm Wines is committed to changing the way you think about pure wine by finding it only in family-owned, small and organic areas. Each bottle is independently tested in the lab to ensure the strongest standards, including organic / organic farming practices. Wines are not mixed with sugar and wines have low levels of alcohol to reduce the side effects caused by drinking too much alcohol.

Their strong wine-making process involves the use of grapes grown naturally / biodynamically and tested in the laboratory for hygiene. Wines do not contain sugar, and they do not contain harmful additives. What makes Dry Farm Wines different and unique, as the name implies is harvested dry, without irrigation on small family farms. They also contain a small amount of sulfite, and they are boiled using traditional, wild yeast. It is also known that the Solvang Valley includes arable vineyards. You can book a tour with Artisan Excursion Wine Tours to check out.

0 notes

Photo

Nothing beats enjoying a little red wine after a long day! But it took me a long… Nothing beats enjoying a little red wine 🍷after a long day! But it took me a long time to find one that fits un...my low carb lifestyle.

#after#atkinsdiet#beats#day#dryfarm#enjoying#familyownedwinery#healthywine#Keto#ketocommunity#ketodiet#ketodrinks#ketofam#ketoforbeginners#ketofriendly#ketogenic#ketogenicdiet#ketogeniclifestyle#ketojourney#ketolife#ketosis#ketowine#little#long#LOWCARB#lowcarbdiet#lowcarbfood#lowcarblife#lowcarblifestyle#lowcarbliving

0 notes

Photo

Another thing to do during free time at a family reunion is visit new friends in the vicinity. Meagan and I took a drive to @freshfuturefarm to visit the farm and the grocery store. I attended the conference the farm hosted a few months ago. It was well attended and very informative. Later Tony and I were at the same table with Germaine while attending a farm workshop in Orangeburg. We follow them on social media and enjoy seeing their successes. Well, seeing the farm and everything firsthand was a treat. We met the family before they completed their chores for the day. This farm and store is a source of encouragement and hope for this community without other sources of fresh produce or another nearby grocery store. We appreciated the time to walk and chat with the family. Many blessings to y’all as you continue your work, we look forward to seeing more of the fruit of your labor. #farmer #farmfamily #farming #farmstore #farmersmarket #bananatree #bananatrees #garden #gardens #communitygarden #communitygardens #hens #art #murals #chopanddrop #bananaleaves #northcharleston #fooddessert #sustainableagriculture #scblackfarmersconference #blackfarmers #dryfarming (at Fresh Future Farm) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bz6un9OgHbZ/?igshid=19w6vs7c7cp9x

#farmer#farmfamily#farming#farmstore#farmersmarket#bananatree#bananatrees#garden#gardens#communitygarden#communitygardens#hens#art#murals#chopanddrop#bananaleaves#northcharleston#fooddessert#sustainableagriculture#scblackfarmersconference#blackfarmers#dryfarming

0 notes

Photo

First #flowers first #tomatoes accidentally got the same angle! #happy #garden #berkeley #california #dryfarmed #drygarden

0 notes