#drosscape

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Cerberus #catsgrams #catsofinstagram #cats #catslover #urbancat #urbanexploration #urbananimals #drosscape #animalphotography #originalphotographer #lensbrnetwork #lensculture #italiapm #mobilephotography #samsungmobile (presso Rome, Italy) https://www.instagram.com/p/CaCQFavsQHQ/?utm_medium=tumblr

#catsgrams#catsofinstagram#cats#catslover#urbancat#urbanexploration#urbananimals#drosscape#animalphotography#originalphotographer#lensbrnetwork#lensculture#italiapm#mobilephotography#samsungmobile

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anti-Lawn & the Necessity of Gardening - 01 / ???

Deterritorialization through urban gardening

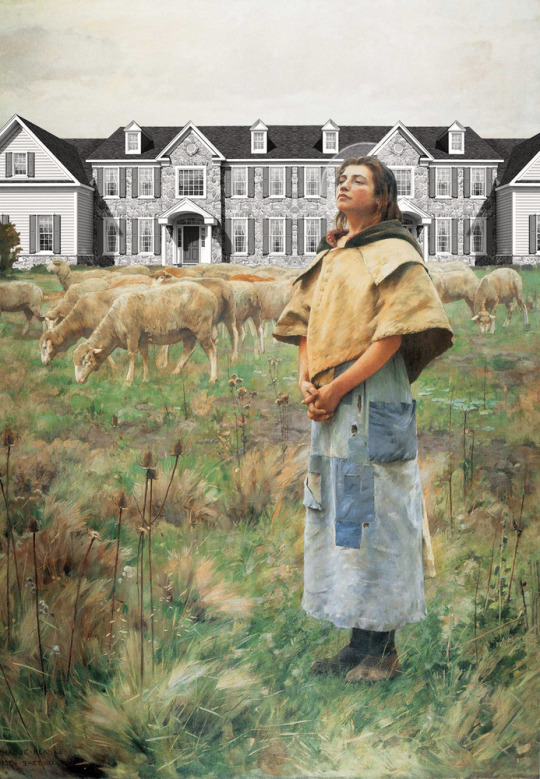

Krumwiede, Kieth. A Good Shepherd, Freedom Land. 2016. In Kieth Krumwiede, Atlas of Another America, 197. Zurich: Park Books, 2016.

“The gardener's generous gesture of free planting has a long history, in which it is often possible to identify a radical critique of private property interwoven with a statement of communal interest, mutual aid and cooperation. This is less to do with a demarcated territory of the (private, domestic) garden. George McKay, Radical Gardening, 155.

The American suburban lawn is an extension of territorial claims within suburban housing, acting as a cultural medium to present certain values and maintain the status quo of grasping some sort of ‘American Dream’:

If I keep a clean lawn then I am a respected member of the community, I look down on those who haven’t mowed their lawn.

As a uniform plane the lawn provides a medium for non-productive landscaping namely for poaceae or gramineae AKA grass, providing no positive ecological, social, or economic value; with its costs and effects on the environment being a driver of climate change. (1) Kentucky Bluegrass is currently the main ecology of a sub-urban biota, being the most prominent and most fertilized crop in North America. The species is so prominent and a defining feature of suburban lawns it’s hard to think of it as being anything other than native, however blue grass is an invasive species that is a remnant of settler colonialism’s ties to the biota and the frontier; having been brought and mixed into the existing biota by early European colonizers. (2)

Deterritorialization of the sub-urban lawn would require a disruption of the existing fabric through an insertion / replacement of blue grass with native plantings. The ideology of ‘every lawn is a farm’ needs to be adopted. I mainly pull on the images of Keith Krumweide’s Atlas of Another America, as a reimagining of suburbia. While Krumweide’s main fictional endeavors revolve around developing the single family home into communal super homes; the pastoral themes and romanticized paintings that serve as the backdrop for these homes are white and settler colonialism in nature, however his representations still address the environment in which suburbia is placed. While a full productive farm in a sub-urban would be radical and a worthy goal in its own right, it’s limited to those who can afford to own the existing territory.

For this experiment we must turn to the drosscape found within the urban fabric, where the lawn is still an ever present medium, making up public parks, institutions, and multi-family housing complexes that continue to promote sub-urban ecology. The seed bomb becomes an indistinct and affordable method to practice anti-lawn methodologies. A seed bomb, aka a seed ball, is a self-contained weapon used by guerrilla gardeners, containing seeds and compost that can be throw on lawns.

Recipe (3)

Start with three parts dried compost, one part seeds, five parts soil and one or two parts water.

Sift the dry ingredients together, add the water and roll the mixture into balls. Let them dry for one or two days.

The preferred seeds are native to Minnesota, including sunflowers, black-eyed Susans, coneflowers and clover.

Initial test coming soon. Recommendations and tips are encouraged.

Son, Jiahn. 2020. “Lawn Maintenance and Climate Change - Psci.” Princeton University. The Trustees of Princeton University. May 20, 2020. LINK

Duble, Richard L. n.d. Kentucky Bluegrass. Texas Cooperative Extension. Accessed May 18, 2022. LINK

Shaw, Bob. 2015. “Guerrilla Gardeners Take over Plots of City Land: What's a Seed Bomb?” Twin Cities. Pioneer Press. November 12, 2015. LINK

#garden#seed bombs#writers#architecture#collage#plants#flowers#wildflowers#arch#places#modern architecture#radicalization#territory#territoires#colonialism#notes

98 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America, Project Projects, 2006, Art Institute of Chicago: Architecture and Design

Architecture Purchase Account Fund Size: 31 × 19 × 2.5 cm (12 1/4 × 7 1/2 × 1 in.) Medium: Book

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/239153/

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fourth Year Undergrad, Estevan Casteneda, teaches us about #drosscapes last night during the Student Scholarship Pecha Kucha Presentations #cppla #celebrate60cppla #cppla60 #pechakucha #scholarship #presentations (at Cal Poly Pomona College of Environmental Design)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Drosscape

Rust Belt

The Rust Belt is a region of the United States, made up mostly of places in the Midwest and Great Lakes. Rust refers to the deindustrialization, or economic decline, population loss, and urban decay due to the shrinking of its once-powerful industrial sector. The term gained popularity in the U.S. in the 1980s.

The Rust Belt begins in western New York and traverses west through Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, and the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, ending in northern Illinois, eastern Iowa, and southeastern Wisconsin. Previously known as the industrial heartland of America, industry has been declining in the region since the mid-20th century due to a variety of economic factors, such as the transfer of manufacturing further West, increased automation, and the decline of the US steel and coal industries. While some cities and towns have managed to adapt by shifting focus towards services and high-tech industries, others have not fared as well, witnessing rising poverty and declining populations.

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl, also known as the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s; severe drought and a failure to apply dryland farming methods to prevent wind erosion (the Aeolian processes) caused the phenomenon. The drought came in three waves, 1934, 1936, and 1939–1940, but some regions of the high plains experienced drought conditions for as many as eight years. With insufficient understanding of the ecology of the plains, farmers had conducted extensive deep plowing of the virgin topsoil of the Great Plains during the previous decade; this had displaced the native, deep-rooted grasses that normally trapped soil and moisture even during periods of drought and high winds. The rapid mechanization of farm equipment, especially small gasoline tractors, and widespread use of the combine harvester contributed to farmers' decisions to convert arid grassland (much of which received no more than 10 inches (250 mm) of precipitation per year) to cultivated cropland.

During the drought of the 1930s, the unanchored soil turned to dust, which the prevailing winds blew away in huge clouds that sometimes blackened the sky. These choking billows of dust – named "black blizzards" or "black rollers" – traveled cross country, reaching as far as the East Coast and striking such cities as New York City and Washington, D.C. On the Plains, they often reduced visibility to 1 meter (3.3 ft) or less.

Drosscape

Drosscape is an urban design framework that looks at urbanized regions as the waste product of defunct economic and industrial processes. The concept was realized by Alan Berger, professor of urban design at MIT, and is part of a new vocabulary and aesthetic that could be useful for the redesign and adaptive re-use of ‘waste landscapes’ within urbanized regions.

According to Berger, drosscape, as a concept, implies that dross, or waste, may be "scaped", or resurfaced, and reprogrammed for adaptive reuse. Berger goes on to explain that this phenomenon emerges from two primary processes. Firstly, Drosscape surfaces as a byproduct of rapid urbanization and horizontal growth urban sprawl. Secondly, these spaces arise as a consequence of defunct economic and production systems. For urban planners, architects and other design professionals, drosscape may offer another creative way to envision space and landscape design in a city. According to Berger, “Adaptively reusing this waste landscape figures to be one of the twenty-first century’s great infrastructural design challenges.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

The video game apocalypses are already here

Early on in the zombie film 28 Days Later, Cillian Murphy wanders out of hospital after waking from a month-long coma and crosses a deserted Westminster Bridge. The roads and pavements are empty and strewn with litter, all the while the gothic Palace of Westminster looms over the bewildered Murphy, now a sightseeing tourist in post-apocalyptic London. Understandably, there has always been a lot of interest in how this iconic scene was filmed. How was such a busy landmark in the capital entirely emptied of people? The answer was fairly simple: they filmed it at 5am on a Sunday in the middle of summer.

Today, there would be no need for such ingenuity. In the heat of a global pandemic, central areas of London are almost entirely abandoned (except on Thursdays when crowds congregate, zombie-like, to clap for carers on the very same bridge). Photographers from around the world have already been documenting cities under lockdown – a deserted Times Square, a lonely Eiffel Tower, a vacant Piccadilly Circus, its Coca-Cola billboard eerily replaced with the deadpan face of a monarch. It could be an image captured from the upcoming Watchdogs: Legion, or the location of a horrifying shoot-out in the new Call of Duty: Modern Warfare.

How quickly reality can be made to look like fiction. We’re used to seeing images of ruination and abandonment. There’s a long artistic tradition fascinated with crumbling visions. From European obsessions with classical antiquity to Romanticism’s love for gothic castles and abbeys. In games this enthusiasm plays out within the realms of the medieval fantasy epic – The Elder Scrolls, Dark Souls or The Witcher series’ many deteriorating structures often echo the work of 18th and 19th century painters like JMW Turner, Caspar David Friedrich or John Constable.

In 2014 the Tate Britain ran an exhibition entitled Ruin Lust, which is as apt a name as any for this seemingly innate desire to witness mournful kinds of destruction. More recently, we’ve become fascinated with modern, urban ruins. Culture has spent decades recovering from pictures of catastrophic devastation caused by the World Wars, and several more bracing itself for nuclear devastation. Slowly, decaying stone towers, ancient keeps and overgrown amphitheaters have been swapped out for bombed cities, abandoned factories, and rotting shopping malls.

Games are just as obsessed with representations of contemporary ruin, and there’s obviously a real pleasure to be found in exploring them. Take Fallout 76, a game whose greatest asset was always its environment: a detailed recreation of a West Virginia left behind. Its map is a patchwork of ruined modernity, all rusted mining facilities, luxury high-rises, highway mega stops and middle-class gallerias. Amongst the genuine Appalachian wilderness are various concrete flyovers and tarmac runways – the in between, suburban spaces that recall the drosscapes and edgelands of a J.G. Ballard novel. These are “large tracts of abused” and wasted land on the periphery: “contaminated industrial sites, mineral workings, garbage dumps, container stores, polluted river banks.” Whilst real landscapes may not have been razed by nuclear bombs, they are surely still contaminated.

The Division series is another game invested in this sort of apocalyptic imagery. Its abandoned New York and Washington, D.C has been overturned, not by zombies, but by a devastating pandemic. Quite uncannily, just as real banks are currently disinfecting their notes in fear of the coronavirus’ ability to persist on paper surfaces, the spread of The Division’s deadly pathogen is caused by this very phenomenon. The irony of a globe ravaged by a virus that attaches itself to capital – a sickness travelling on top of a sickness.

Outside of games there’s a boom in documenting all kinds of disintegrating architecture, a growing interest in things like ghost towns and unfinished structures, and even a rise in activities like rooftopping, skywalking and urban spelunking. Whilst intrepid urban explorers jump barriers and sift through reality’s ruins, games allow us to do something similar within increasingly sophisticated virtualities. And yet whilst the real world seems to be filled with opportunities to delve into and examine real ruins and zones of abandonment, games often tend towards fictional extremes. Try and count how many big-budget titles are future-orientated or out-right post-apocalyptic and you’ll quickly lose count. But what seems increasingly apparent – particularly amidst the ongoing pandemic, and widespread environmental collapse – is that for many of us the apocalypse has already arrived. To rejig an oft-quoted line from the father of cyberpunk, William Gibson: “the [apocalypse] is already here – it’s just unevenly distributed.”

We see urban destruction all around us in our daily lives. Another way of looking at all this ruination is as a continuation of Gothic aesthetics. Gothic art and literature was very much about how old, medieval forms were superseded by industrialisation, and how often these ancient things rise up and return to haunt us. Today, the process continues, except instead we are witnessing more industrial elements of capitalism being replaced by newer, more “advanced” post-industrial forms. Instead of ruined castles we get the shells of factories and derelict public housing. Instead of paintings of Tintern Abbey, we get haunting photographs of post-industrial Detroit.

We’re often dreaming of post-apocalypses, waiting for that big moment or cut-off point – for the bomb to drop. But ruins are all around us. Photographers like Matthew Christopher and Seph Lawless have spent years documenting contemporary ruins with their cameras. Christopher’s book series, Abandoned America, looks at a wide range of shattered dreams – everything from derelict schools and universities, to old hospitals and asylums, and even the shattered visages of humongous presidential busts. Seph Lawless has similarly recorded the slow ruination of American capitalism. His books on dilapidated theme parks and abandoned malls are the perfect environmental inspiration for video games. His ghostly images highlight the destructive, self-cannibalising energies of contemporary economic systems. As people like Dan Bell pick through the debris of shuttered shopping centres in his Dead Mall video series, we can begin to appreciate the fact that when even the greatest symbols of 20th century consumerism are left to rot, nothing is sacred.

When it’s not ruins left by American capitalism, it’s spectral images coming out of post-Soviet areas that catch our eye. One of the greatest game series involving urban exploration, STALKER, is based on the very real ruins that surround the Chernobyl Power Plant. Outside of this one specific zone, we see wreckage turned aesthetic in various “Cosmic Communist Constructions”, such as those photographed by Frédéric Chaubin or Rebecca Litchfield.

As time and history moves on, it doesn’t just produce physical ruin, but various ghosts and phantasms that seem to haunt our cultural imagination. Adventure games like Disco Elysium, Kentucky Route Zero and Night in the Woods have all been particularly successful in leaning into this idea of a contemporary Gothic. In Night in the Woods, the town of Possum Springs contains a number of boarded-up and closed-down stores. The game’s declining mall and disused rail system all stem from the loss of industry and severe economic depression. Likewise, the first act of Kentucky Route Zero has you exploring an abandoned mine, whilst Disco Elysium features areas like the Doomed Commercial Area, a shuttered factory, a derelict pier, and even an old ruined sea fort. Sometimes these places are physically haunted within the game’s fiction, other times there is simply an eerie absence of the human – the ghosts are all shattered dreams and failed utopias mixed up amidst the physical rubble.

We often hear about defunct things being assigned to the “garbage heap of history”, but the truth is history itself is one giant dustbin. We needn’t look to the far future to find striking examples of ruin, only to the past. All over the world there are structures abandoned or doomed to unfinished states. Take Hashima Island, perhaps most well known for its appearance in the James Bond film Skyfall. Commonly known as “Battleship Island”, the place was a centre of industrialisation (and forced labour) until its closure in the 70s. Other ghost towns like Varosha, an abandoned seaside quarter in the Cypriot city Famagusta, Fordlândia in the middle of the Amazon rainforest, and even Pripyat – a place we’re all exceptionally familiar with – show us what might be left behind when disaster strikes. We might also cast our eyes towards more modern ghost cities. Much has been made of places like Ordos, a modern metropolis that seemed to suddenly spring up from the deserts of China’s Inner Mongolia. Similarly, drone footage of incomplete luxury housing developments in Turkey, and the unfinished tower blocks of Iran’s Pardis (Paradise), are all evidence of the physical effects of ongoing economic crises.

As we hurtle towards the future, civilisation will no doubt accumulate even larger piles of physical rubbish. Our leftovers are already considerable, and we need never look far for it. There are abandoned pockets and ruined zones in each and every city in the world. And with evidence of the apocalypse all around us, it’s no wonder games both highlight this damage as well as take things to their logical extreme, where capital cities are entirely emptied and the planet is irreversibly scarred.

from EnterGamingXP https://entergamingxp.com/2020/05/the-video-game-apocalypses-are-already-here/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=the-video-game-apocalypses-are-already-here

0 notes

Text

Theory Week 6: Ecologies, Corporate Landscapes

Jean Baudrillard - “Maleficent Ecology” (1994?) Brett Milligan - “Corporate Ecologies” (2010) David Gissen - “The Preservation of Disability” lecture at UT CoAD, Oct 08, 2018

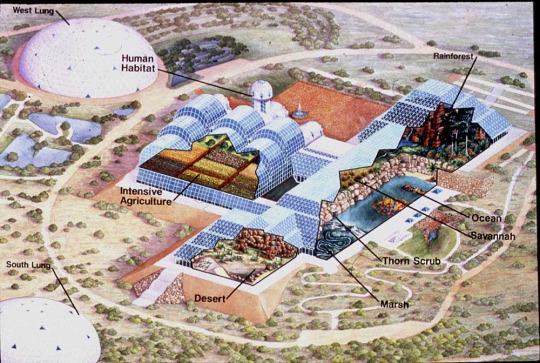

Picture from Alan Berger’s book, copied from https://ahbelab.com/2017/01/11/a-quommentary-about-the-drosscape-manifesto/

REFLECTION

I am stuck between the rather pragmatic examples of poor corporate landscapes (e.g. MVVA’s General Mills design being scrapped and replaced by turf) and the rather metaphysical ideas of waste (production of waste, producing human waste, human race as waste). To reiterate my optimism, although we should continue to acknowledge the production of one-time-goods and products meant for short-term consumption, waste still can be considered a building block and a tool. In this we confront idealized landscapes (and of the human form). Waste and wasteful landscapes, then, can be used as critical tools for evaluating and hopefully provoking the idea of the picturesque landscape (and the classical form). I am unsure how to understand Budrillard’s comments about liberation and its dangers (about eliminating the delineation between subject and object) but for now, I will chalk that up to spooky metaphysics talk. Perhaps those ideas will mean more at a later time, during a technology discussion, or other encounters of the distinctions between subject and object.

SYNOPSIS

Jean Baudrillard’s “Maleficent Ecology” (1994?) is a difficult text to work through for it compares the matter of new ecologies, specifically BIOSPHERE 2, to the very extinction of the human race. He starts with observations of history that once there was a law protecting the rights of something, it was only the announcement of its end. When laws to preserve and protect nature set in place that it is its death sentence, and Baudrillard marks the defend for human rights as the death sentence to humanity. In the process accompanied by idealization and promotion, Baudrillard says, the human culture has become adapted to creating waste. By creating hyper centers, the surrounding becomes wasteful. Absolute liberation, perhaps like what Frampton suggested, was a trick upon nature and upon human race, and by giving nature the same rights that were given to wasteful humans, the balance and distinction between subject and object becomes upset, and human race has now set itself for elimination. In Biosphere 2, set up in 1991 in Oracle Arizona, Baudrillard criticizes the enterprise as a typical American construction. It is “an experimental attraction” rather than an experimentation per se, set up on a “gigantic hypothetical error.” The error here, Baudrillard continues, is assuming the natural response to life is self-preservation and the instinct for survival. However, the compliment to life is death; and death always must accompany life; and by focusing solely on life mankind has invited death upon itself in this artificial dome. Baudrillard further comments that artificial creations that was to defy evolution, aka death of certain species in some kind of progression, is “specious,” meaning it is superficially plausible but just wrong. (Perhaps this part will come back in a later time.)

Brett Milligan’s “Corporate Ecologies” (2010), on the other hand, was a straight forward and well written exploration of the term. In essence, Milligan suggests that the term should be used beyond Google and Facebook campuses, but be a vehicle to describe the extremely modern landscape of “geographically dispersed systems that occupy and transform landscapes in specific, [standardized,] modular ways at an unprecedented range of scales.” Milligan draws from landscape ecology, urban ecology, and studies about ecological footprints to identify and summarize the landscape of metabolism + material/energy flow. The design question and the resulting landscape is one that corporations have colonized (happy Columbus Day!). Again, to further continued themes of “second modernity” (Roener van Toorn, “No More Dreams?”) and “global ‘somethings’” (theme that appeared as far back as Michael Speaks’ “Theory Was Interesting...”) we see evidences if “late stage capitalism” (don’t remember whom to attribute) as Milligan points out that a handful of corporations are “more productive” (economically) than nations. {Note: Aug 2, 2018 Apple surpassed $1 trillion in worth; Amazon followed in Sep 4, 2018.} Thus, corporate life has an extreme power of influence and it is reflected by its massive scale of transformation upon the landscape. These activities are transurban, where urban is defined by “activities and material flows that form and sustain human inhabitation.” (8) Then, transurban means that these corporate landscapes go beyond the urban area - where typically there is a density of human habitation - and affects peripheral and distant landscapes (e.g. sprawl and global networks). The corporate landscapes, outside of the heart it supports, exhausts productive capabilities. The end result, Milligan calls, is a post-corporate landscape - which is a stage before the typical reclamation / reprogramming of the site, where it is abandoned with residues of the very activity that ended it. These sites are specifically chosen, thus there is competition among these sites. The chosen sites then are homogeneously treated and similar landscapes are left behind across the globe. Regarding economy of scale: for bigger production leads to lower costs of production, there is an endless greed for growth. Corporate entities, then, desire to brand itself, and the brand is carved permanently into the landscape (until further transformation). Meanwhile, at corporate headquarters, the process of production is obscured and absent, and traditional design and works of landscape architects display beautiful facades that work as a hallmark for the brand of the company (“ecology of psychological persuasion”, “corporate propaganda”).

SYNTHESIS

Without a doubt, Milligan’s outline for the corporate landscape - that for a concentrated urban area, ‘nature’ is endlessly converted into energy to sustain it; and like the surroundings of a highway, what is not the product of concentrated effort, it becomes waste. However, as honestly depressing as Baudrillard’s 1994 work is, 2018 is a place to be optimistic about the situations that we’ve found ourselves in. Alan Berger’s “Drosscape” (2007) essay calls the decentralized American landscape as a “waste landscape” and identified { 1. horizontal urbanism (sprawl) and 2. abandoning the land } as the two causes for that phenomenon. Rather than considering wasteful production as abnormal (like Baudrillard), Berger identified waste as a natural product of the city (“manifestation of industrial processes that naturally produce waste” - rather than defining as the given habitat of people). Waste, then, is an indicator of healthy growth of the city. It is only “in situ of growth and maintenance” and only waits to be incorporated into the new design. This all aligns very well with the CoAD Lecture this week by David Gissen, the famed author of /Subnature/. His lecture, “The Preservation of Disability” offers a manifesto for preservation+reconstruction+et al.. The background for Gissen’s argument is that the strategies employed to provide access to people with disabilities (based on disability studies) expands their access to space (a location and place to physically experience the artifact). His argument, then, is to intensify and employ those strategies to provide access to time (history) to all visitors. To build up to this argument, Gissen gave us a brief overview of disability theories. For a long time, the [medial] (eugenics) model held disabled forms (and subsequently modern art) to be an offense to classical aesthetics and form. The following [social] model overturned the wrongness of the bodies to wrongness of society; that disabilities do not define people, but those obstacles are formed by society. As Gissen pointed out, both of these views held disability and debilitation to be inherently unwhole (lacking) and that they were deviant of classical and idealized form (like modern art). The following [critical] model challenged that idealization and classical-form-norms. Giseen’s work combines this model and goes further, again, and subscribes to a practice model that heightens the experienced history of an artifact, and wishes to present that as an experience of the artifact, rather than the static idealized form that is ‘visitor-appropriate.’ Towards the end of the lecture, Giseen talked about fragments and ruins and compared them to dust ; that the reaction to debilitated artifacts should not be woe, but similar to an attitude that looks at a brick (a building material). Anyway, the point of all of this was to say that for Gissen, waste, residual, and artifacts are not only proof of a suicidal race, but also holds immense potential for further projects.

0 notes

Text

CURIOUS

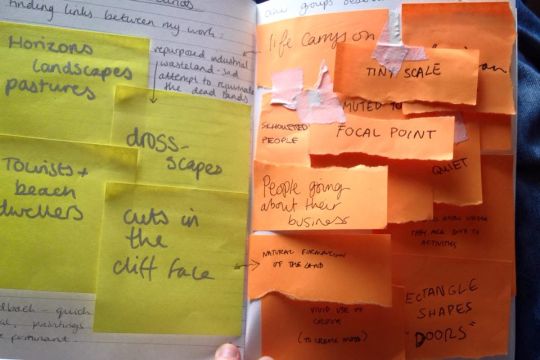

This workshop acted as an alternate form of crit for our summer work (photography and drawing over the holidays). I feel that I definitely got more out of this crit than usual, or at least took away different things than usual.

First we were asked to name and hang up our work. The space to stick up the work was small so the images had to be clustered together and overlapping in places. Because of this I had to think about how the images related to each other and sat next to each other, whilst naming the images made me consider them more as individual pieces as well as smaller, direct series.

We were asked to identify themes in our work, and write about what they said about our practice. Having to name and label my work kick-started this process. In groups we then did the same for other people’s work, and I was lucky enough to have mine written about. (Yellow sticky notes are mine, orange are the other group’s feedback).

Most of my images & paintings were of the rural Cornish landscape, mostly because I love it deeply and feel very sad when I have to be separate from it in London. Within this, the other group observed a few things such as: my images often had a small focal point which highlighted the vastness of the natural formations (cliffs, hills, etc), I often painted and photographed the horizon line (taking in a massive area), the moments seemed quiet and peaceful.

They also pointed out that there was a sense of ‘life carries on’, which links to my observation of drosscapes, re-purposed industrial wastelands which I found myself interested in. I found these areas funny because they often look very sad, and are just unsuccessful attempts to rejuvenate dead land. They also epitomise Cornwall, somewhere desperately trying to recover from a dead mining industry that scarred the landscape. Life carrying on is a more positive spin on this, and I think there is a sense of natural life persevering especially.

The next activity was to re-frame our images.

Re-framing allowed me to focus in as well as re-contextualising and de-contextualising. The torn frame was my favourite to work with as it seemed like a window giving a glimpse of the image & fitted well with the natural forms as a natural hole rather than a tool-cut one. By framing the image like this the image becomes packaged, surrounded, like a keepsake taken from the original full image. It also adds another layer, a foreground to the image, which I think worked particularly well with the last two - images which already had very defined depths.

0 notes

Text

http://twitter.com/newsuburbanism/status/853283007226142720

DROSSCAPE by Alan Berger #PDF https://t.co/32CvZzrQFp

— New Suburbanism (@newsuburbanism) April 15, 2017

from Twitter https://twitter.com/newsuburbanism April 15, 2017 at 12:24PM via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Gasometri e vulcani. Finestrino con vista #napoli #naples #napoliest #landscape #landacapes #drosscape #vesuvius #vesuviusvolcano #vesuvio #fromthetrain #fronthetrainwindow #italotreno #altavelocità #mobilephotography #lensbrnetwork #lensculture #samsunga51 #samsungmobile #italiapm (presso Naples, Italy) https://www.instagram.com/p/CdRGCy0sPea/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#napoli#naples#napoliest#landscape#landacapes#drosscape#vesuvius#vesuviusvolcano#vesuvio#fromthetrain#fronthetrainwindow#italotreno#altavelocità#mobilephotography#lensbrnetwork#lensculture#samsunga51#samsungmobile#italiapm

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America, Project Projects, 2006, Art Institute of Chicago: Architecture and Design

Architecture Purchase Account Fund Size: 31 × 19 × 2.5 cm (12 1/4 × 7 1/2 × 1 in.) Medium: Book

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/239153/

0 notes

Photo

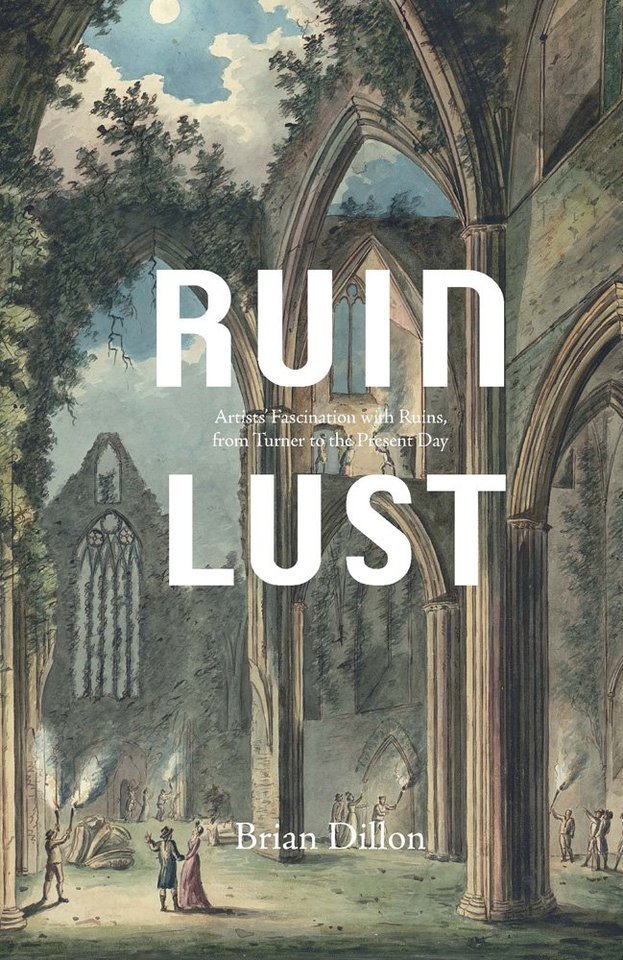

Ruin Lust Artist’s Fascination with Ruins, from Turner to the Present Day Brian Dillon

What the ruin means today:

‘A reminder of the universal reality of collapse and rot; a warning from the past about the destiny of our own or any other civilisation; an ideal of beauty that is alluring exactly because of its flaws and failures; the symbol of a certain melancholic or maundering state of mind; an image of equilibrium between nature and culture; a memorial to the fallen of an ancient or recent war; the very picture of economic hubris or industrial decline; a desolate playground in whose cracked and weed-infested precincts we have space and time to imagine a future.’ The taste for ruins is a post-medieval invention:

Ruinenlust (Ruin Lust) – German term than the scholar Rose Macaulay resurrected in her 1953 study Pleasure of Ruins. Ruins may have offered Renaissance poets, artists and architects elevating models for their own endeavours, but by the 18th century these structures and sites also looked like warnings of a sort. Doomed arrogance of our race. Piranesi – ruins are not static, ruins allow us to set ourselves loose I time, to hover among present, past and future. History of Ruin Lust:

Affinity with poetic intervention was just one of the reasons why ruins – new ruins that is – proliferated in the gardens and great estates of the 18th century: the artificial ruin stood as both inspiration and emblem of its owner’s modern sensibility. Roots in a mode of seeing – more precisely, framing the ruin in a landscape – that was directed at medieval as well as classical remains. Ornaments of time: ivy, moss and other ‘humble plants’ – evident in J.M.W. Turner, Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking towards the East Window, 1794. (Pg. 10) The triumph of nature over the relics of culture and the idea that a ‘natural’ landscape was in fact ideally set off by some reminder of human time. When later artists and writers have evoked the motif of the ruin or recalled the ruin lust of the 18th century as an antique mentality, it has been with some necessary self-awareness. The picturesque is not an aesthetic that has been easy to revisit without irony. Patrick Caulfied – Greece Expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi, 1963 – derived from a motif, the classical ruin. Moving to the 19th Century:

At the height of the ruin lust of the eighteenth century, violent catastrophe was just as essential to the elaboration of a concept of ruin as sloe and attractive desuetude. Denis Diderot, Salon of 1767 – ‘The ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes, only the world remains, only time endures.’ 19th Century – the tradition of this excitable projection of ruin into the future that we have to place the seeming proliferation of visions of destruction – especially urban destruction – that arose in British Art and Literature. Hubert Robert had painted the Louvre in ruins in 1796. The 19th century not lack for visions of future disaster and desolation: Mary Shelley’s apocalyptic novel The Last Man (1826) Richard Jefferies’s After London (1885), with its narrative of the ravaged city slowly overcome by nature.

The central ruinous motif in British art and literature of this period was by Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1840. Projected his readers forward – a traveller from New Zealand, in the midst of a vast solitude, takes his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St Pauls. A century or more after, his great niece reflected on the destruction of the capital wrought by German bombing. Rose Macaulay, Pleasure of Ruins, - ‘Ruinenlust has come full circle: we have had our fill? Surely the taste for ruins requires a degree of fantasy.’’ But such wholesome hankerings are, it seems likely, merely a phase of our fearful and fragmented age.’ Paul Nash, Totes Meer (Dead sea), 1940-1 In the final pages Macaulay wrote about the buildings left gaping but oddly ennobled by the bombs. The Prospect of an Entire City Laid to Ruin:

Classical and biblical examples provide the models for how one might look at such a scene; Rome, Pompeii, Babel, Sodom and Gomorrah. But by the middle of the century the modern city was just as apt to provide images of ruin, either in reality or in the context of anxious visions of the future. Photography was then providing new images of the old ruins more familiar from paintings and poetry. Wars of the 20th century occasioned many acts and examples of urban ruin i.e. vast ruination of Europe’s cities in the Second World War. In the second half of the century there was a good deal of artistic response to the city. The more precise failures of modernist housing complexes – hastily built and quickly neglected – may be seen in Rachael Whiteread’s Demolition series of 1996, showing the erasing of tower blocks on three estates in Hackney. ‘The spectre of the city in ruins still haunts the contemporary imagination, quickened now by the idea of ecological collapse and the depredations of more recent economic crisis’ Pg.30

Decayed Detroit – illustrates time and again the effects of global financial disaster. Becomes a terrible warning about human ambition and hubris. Discrete Object: • The ruin is at one level an object, at another a motif; it stands in relation to its surroundings. • The ruin has a dialectical relationship with the landscape. And further with mature itself; with an idea of nature and its decaying or burgeoning reality. • Georg Simmel – As the structure decays, nature begins to take the upper hand, exercising its ‘brute, downward dragging, corroding, crumbling power.’ • Natural World – is that not also subject to a type of ruination, whether by organic, geological or artificial forces? - Natural catastrophe has long been a subject of artistic representation – biblical flood, destruction of cities by volcanoes or earthquakes or more recent depredations of environmental emergency. • For the Romantics, bleak and desolate landscapes such as those of mountainous regions seemed to match on a vast, even more sublime, scale to the fabled destructions of cities. • The apparently natural world is victim of our labours, ambitions or neglect – it is possible to conceive a whole landscape turned to ruin. - Such landscapes have proliferated in British art of the past half century; poisoned land, post-industrial ruin turning back to nature, sites rendered desolate by human activity. - Geographers have begun to call such territory ‘drosscape’; many artists and writers have been seduced by the notion of ‘the zone’. - Name derived from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker – in the Zone nature and culture, landscape and ruin, begin to bleed into one another, so that we can no longer see what ruin is and what is background. - Keith Arnatt, A.O.N.B (area of outstanding Natural beauty) 1982-4

Conclusion: • The ruin lust of the 18th century begins in part in a way of thinking about – fearing and hoping for – the future. • The ruin traffics with more than one timeframe; it arrives from the past, but incomplete. It may well survive us, or slump into vacancy before our eyes. It stands as a warning for our own futures – it leaves room amongst its empty vaults and vistas, for the invention of a new future. • Perhaps most unsettling, it conjures a future past, the memory of what might have been. It is this retro-futurist aspect of the ruin that has excited the most artistic attention in recent decades – the way they haunt a present unsure if there will be a future, never mind what it might contain. Robert Smithson – given a name to this new temporal predicament among the relics of the mid-20th century architecture, infrastructure and environment; ‘ruins in reverse’. These are relics that don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built. Even the most solid and indestructible of remains could no longer be said to be themselves alone, but rather routes out of our own moment – portals into past, present and future.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Photographer Jason Orton and author Ken Worpole have spent over a decade documenting the Thames Estuary in South East England. (Photo: Jason Orton)

5 notes

·

View notes

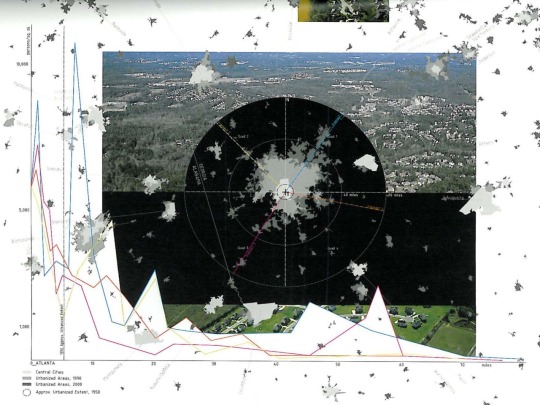

Photo

Alan Berger’s Drosscape. Atlanta transcet.

178 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kounellis out of context #mobilephotography #samsunga51 #streetphotography #urbanexploration #drosscape #waste #originalphotographer #italiapm #ig_streetphotography (presso Rome, Italy) https://www.instagram.com/p/COPQm4ihM2f/?igshid=1nzkof8f8hyhx

#mobilephotography#samsunga51#streetphotography#urbanexploration#drosscape#waste#originalphotographer#italiapm#ig_streetphotography

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fight the climate change. Cool the planet #drosscape #trash #waste #wasteland #urbanexploration #urbanwaste #fridge #instawaste #igwaste #mobilephotography #samsunga40 (presso Via di Rocca Cencia) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2gF80hC5TA/?igshid=njk20fxixqbu

#drosscape#trash#waste#wasteland#urbanexploration#urbanwaste#fridge#instawaste#igwaste#mobilephotography#samsunga40

7 notes

·

View notes