#doomer fallacy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Changing perspectives on children’s vulnerability

Are children “naturally” vulnerable, or is their vulnerability socially constructed — And most importantly, does it matter?

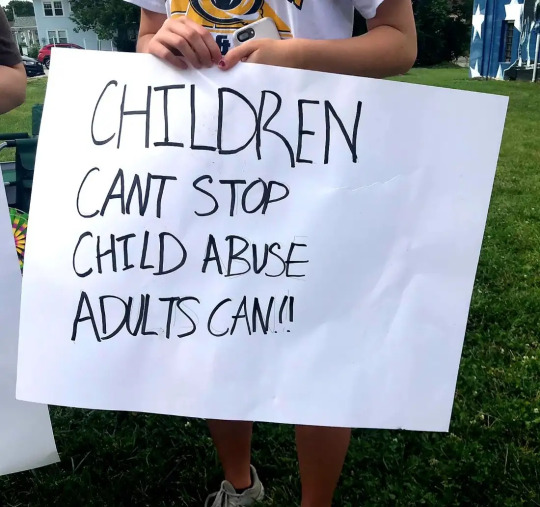

One of the main objections to the liberation of young people is that freedom is dangerous because children are “vulnerable.” But what are they vulnerable to?

Abuse.

And who is perpetrating this abuse?

The data tells us that it’s parents and guardians.

It appears, then, that parental power and authority don’t protect children; they imperil them. This should be hardly surprising, since total control of another human being is so easy to exploit.

It’s undeniable that children’s position in society is at least partly responsible for children’s vulnerability, which is often claimed is simply natural. But some might argue it couldn’t be otherwise — that the abolition of that authority would make things worse, that child abuse from parents and guardians is the inevitable result of children’s natural dependence (the childish dependency/adult independence binary has begun to be challenged by the concept of interdependence [Cockburn, 1998]), and most importantly that it is rare rather than normalized (when statistics and well, the fact that children are the only people that is legal to hit in the US tell us otherwise). Therefore, the only way to “keep children safe” is to restrict their freedom.

Let us set aside the radical thesis presented by Tal Piterbraut-Merx in a 2020 article that children aren’t vulnerable, but oppressed. Even if it was true that all children were inherently more vulnerable than all adults, does this justify stripping them of their rights?

In these discussions, the adult abuser is made to disappear; they’re all centered on the child. As if child abuse wasn’t an adult problem. As if it is children that have to be punished by loss of freedom because adults mistreat them. The assumption is that to abuse the vulnerable is human nature, and segregation of the vulnerable is the only way to keep them safe. Our adultcentric society is portrayed as the standard and the only way things could and should be.

Jens Qvortrup wrote in 2005 about children and the public space:

Although the reduction in traffic fatalities is of course welcome, is it permissible to suggest that the price for the positive result is by and large paid by children in terms of a decrease in their freedom of independent mobility? The price was certainly not paid by adults in terms of adapting to children’s needs, or in acceding to their legitimate demands to be able to use the city as if it was theirs as well.

He also pointed out how concern over “children’s safety” is used as a mask for misopedia:

The introduction of curfew bills in both the USA and the UK may be interpreted in the same way. Under the pretext of a wish to protect young children from danger, they are not permitted to be outside during specified periods, typically during the hours of darkness. It is however well known that these measures towards children are most welcomed by many adults who see themselves as disturbed by children.

- Studies in Modern Childhood

I would think that if a group of people is unable to exist alongside another group of people that is, as it is argued, naturally more vulnerable physically and mentally, without causing them harm, it is their freedom that should be restricted.

Of course, we cannot reduce this argument simply to adult oppression of children; both Qvortrup’s example and the inability of most parents to relate to children as equals are consequences of capitalism that we can hardly hope to abolish in a capitalist society.

But the fact that not only do adults put no effort to accommodate children’s needs (natural or socially constructed they be) in our current society, they also aggressively deny the oppression of children, remains.

While victim-blaming has become increasingly problematic in relation to adult victims of violence, it’s the norm when it comes to child victims. No one contextualizes child abuse as one of the many expressions of adult supremacy; if anything, it is used to argue why children should be subordinated to adults. Hence why there is this false dilemma between liberation and protection, used to discredit liberationist arguments (or, less often, protectionist ones). Children need both types of rights expanded; perhaps for children of different ages, one or the other should be emphasized more (protection rights for younger children, and liberty rights for older children and teenagers). But just like adult citizens, they need both. You can’t be safe if you’re not free. And of course the reverse is also true; before profound social changes in the ways adults relate to children, equal rights would just give adults new avenues to exploit children.

But there is an important problem with the “rights” approach in general.

As Marx knew, individual rights under a capitalist society lead to inequality. In an adultcentric society, “rights” for children are an empty concept. Not only are they always determined by adults, they are the rights adults think children should be “given” by them. But as pointed out in this blog post, what is needed is not liberty rights, but liberation:

Merely demanding “equal rights” for youth is incomplete. Even if equal rights were achieved, that framing allows those with power to dictate the terms of oppression while justifying the status quo because everyone is now “equal.” That won’t do. It won’t lead to liberation. If youth have “equal rights” but are still stuck within broader oppressive structures, then we have failed.

Our society is structured to privilege the needs of adults over those of children; whether this produces their vulnerability or simply exploits it is not as important as one might think. What is important is that it paints segregating one-third of the population as just because adults cannot be expected not to abuse their (cultural or natural) power.

#repost of someone else’s content#medium repost#Alba M.#paternalism#adultism#childism#child abuse#youth rights#youth liberation#theory#ontogeny vs sociogeny#doomer fallacy#biology is not destiny#if nature is unjust change nature#FAQ#101#important

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

98% of all anti-suicide messaging is literally just the gambler's fallacy, but if you follow their logic to its logical conclusion and point out it can go the other way, they'll just call you a doomer

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m not sure why I re-created an account on here. I was addicted to this app ten years ago, but I’m not desperate for a community these days. I think I want to find avenues to keep writing, and physical journaling while appealing in theory isn’t something I realistically find time for. So I think I’ll try to deliberately reflect here while I’m preoccupied with my phone and want to stop scrolling headlines. I want to remain mood-resistant to the news cycle and the masses of reactionary or illiterate or tone-deaf or bigoted or logically fallacious people commenting on every single post with their doomer takes and their optimistic takes and their nihilist memes. Crushing overload at one’s fingertips every day. And I know I do better without it, or with less at least. I don’t like knowing I’m doing something I don’t enjoy and I’ve finally gained better presence to recognize these things. 31. 32 in a few months. It is what it is.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The core mistake the automation-kills-jobs doomers keep making is called the Lump Of Labor Fallacy. This fallacy is the incorrect notion that there is a fixed amount of labor to be done in the economy at any given time, and either machines do it or people do it – and if machines do it, there will be no work for people to do.

Why AI Will Save the World | Andreessen Horowitz

0 notes

Text

So, I won't engage with everything you said, because I recognize that my ability to speak with a sufficiently meaningful amount of knowledge on some of the biological stuff is dubious. Like you said:

I somewhat disagree (modulo nobody really knowing what they're talking about)

That's probably just what it comes down to. Most sci-fi speculation runs afoul of this problem eventually. So consider the following parts as being mainly speculative, and then I'll stand a little more assertively on some other stuff later:

Part of it is just that I don’t see much reason to think of human intelligence as a ‘difference in kind’ rather than a ‘difference in degree’; there are a few specific neurological structures that are rare in other species, but afaik none that are entirely unique. This is something I could easily be wrong about

This is something I've thought about a lot, too.

On one hand, I have argued that the "Universe of the Mind" is actually much smaller than a lot of people assume, because given the common ground of the physical reality we share, many abstract principles which interpret and value that reality are convergent from different viewpoints. For instance, this is partly the reason why I do not share in all the doomerism about AI becoming hellbent on destroying humanity because of our inefficiency to a hypothetical AI's hypothetical goals. I think any highly-sapient being would be very likely to value other intelligent life, even of an inferior degree. (This is when most AI doomerists reveal that they don't actually believe in AI and are actually worried about us creating a Universe-swallowing version of Clippy, the Microsoft Office helper bot, i.e. an all-powerful idiot. But that's a conversation for another day...)

On the other hand, I know just enough about animals from my personal experiences with them to understand the fallacy of anthropomorphizing them. If you think human diversity is something, consider how vastly different the experience of reality is for an animal from another species! And that's just from larger animal species here on Earth; it barely scratches the surface of advanced (multicellular) life in general on Earth, to say nothing of other possibilities for life.

My reconciling / unifying view on this is that sentience is the key: our sensory experiences in our physical bodies. Notwithstanding the hypotheticals of creating artificial life, all life as we know it thus far is defined in its nature, perception, and behavior of the world through two things: Its environment, and its body. The environment to some extent we share in common: terrestrial gravity and weather conditions for land-dwelling species, the consumption of common energy sources as food (the whole reason something like fruit exists, after all!).

But our bodies can be very different, even though, within the grand scheme of all possible life, terrestrial bodies are quite similar. But consider, if you will, how much of our lives is defined by our bisymmetry; and then consider a relatively intelligent being like an octopus who has considerably more limbs to work with. Or a quadriped like a dog to our apish biped bodies, or a bird such as a crow who has wings to fly—relatively intelligent creatures who have no hands. Think about how different reality is when you have no hands, but do have a pair of wings.

We share in common the constraints of biology and environment: We hunger; we play; we explore; we hoard shinies. But what of our art? Our philosophy? Our descriptions of living? These would be quite divergent I think. Even among species as relatively close to as as dogs and crows are. So imagine just how divergent the full breadth of possibility is, in these respects? It all comes down to the sentience that derives from our physical bodies. I think life as we know it requires a physical body. And, by the same token, when speculating machine life, or "energy" life, I think this only opens the door to even further divergence and alienness.

I agree with you to some extent: There is a question of degrees. We deal with this question within our own species, not only with children and the elderly and the mentally impaired but also with differing levels of intelligence among otherwise-healthy individuals.

But I do think there is also a question of kind. Certain functions, like the perception of space or the ability to compute arithmetic, we would expect to be convergent. But the full range of possible physical behaviors in the Universe is, I think, broad enough to justify the claim that different kinds of intelligence, fundamentally, are at least possible.

I went looking in my original post to see what you might have been responding to / disagreeing with. I think it's this part:

I think of the development of human-like intelligence as "merely one pathway out of possible untold myriads."

To clarify, what I meant by that is not that "human-type" intelligence is one possible evolutionary pathway out of myriads, but that "intelligence at all," at a scale of human capability or higher, is one pathway out of myriads. I was pointing out that virtually all the species on this planet don't rely on being "smart" in order to survive and propagate. The species that do are, numerically anyway, statistically insignificant.

Feel free to correct me if this is not what you were replying to with your above remark.

A simple matter of increasing brain volume, in other words, and our capacity for abstraction and complex language just falls out when you add a bunch more neurons to the existing neurological anatomy of great apes.

I don't know how persuasive I find this. Crow brains are very small compared to ours, physically. Blue whale brains are several times larger than ours. Both species are notably intelligent, but there is no semblance of a linear (or logarithmic) relationship. I don't think intelligence is a simple matter of brain volume.

Maybe you were talking in terms of the baseline for a given species? Maybe you would say that if blue whale brains got another several times larger then they too would uplift into what you might characterize as human-scale intelligence? I don't know that I'd disagree with that, but I don't think I would be ready to commit to agreeing with it either.

Part of it, also, is that the currently leading theory for the evolution of human intelligence is that it wasn’t strictly speaking a response to exogenous forces. We didn’t need our big brains to evade saber-toothed tigers or find edible berries; rather, it was a product of sexual selection and intra-tribal competition that became a runaway selective force. In other words, human intelligence is in its evolutionary function a kind of plumage.

I like your description at the end of brains as plumage! =D

But this is where my own intellectual depth is the shallowest, so I don't think I will venture to say anything substantive.

Except that I will say that, if this is true, then societal and social forces have long since disrupted it as a highly-valuable signal.

Also this is a good chance for me to brush off Toggle's Law, which I'm still quite fond of.

I enjoyed this post and will perhaps respond to it later!

One quick thing that comes to mind for me is that I might compare what you call the "encryption" of bioavailable energy to the natural progression of the life cycle of a star: burning hydrogen at the beginning and for much of its life, and generating all of this "waste" helium that can't be used, until suddenly, by the star's own nature, the shortage of hydrogen causes the helium to naturally and inevitably become usable, and on up through the elements all the way to iron. Similarly, it makes me think of the reaction chains in nuclear fission, with radioactive decay undergoing multiple stages, all with their own potential utility. As with fusion, conversion uses up a lot of energy (making it unavailable afterwards), but there's still a lot of energy there. Likewise, the production of coal or peat ultimately serves the entropy effect (as you note), but retains a great deal of energy nevertheless.

The creation of fancy and/or rare molecules through biological processes, and the gradual sequestration of energy-dense biomatter in environments not conducive to life, strike me as "byproducts" of a planetary ecosystem (that is, an ecosystem situated on an active planet) which, in time, become reused by that ecosystem, as ecosystems are always trying new things and often eventually tap into fruitful pathways.

To that point, I am continually surprised that no microbes have evolved yet to digest plastic in a wide latitude of environments (a true Monkey's Paw solution to the plastics problem), but you make a good point when you say:

We had a big potential energy source literally just lying around for several hundred million years, which is biology’s favorite thing ever, but it turns out that the easiest way to turn that in to more biology was through the intermediary of intelligence, rather than (as one might naively expect) a super fancy microbe or something.

Just because a "fruitful pathway" as I called it is possible doesn't mean that natural selection will find it in a timely manner, if ever. Your quote here expresses this well, albeit indirectly.

Anyway, I more or less agree with your observation here:

But anyway, I started to think about human intelligence in those terms and I think actually it’s somewhat true in an interesting way.

I think you're onto something at least partially. As you pointed out, we wouldn't be here without (biologically speaking) species that came before us to fill the atmosphere with molecular oxygen and (sociologically speaking) to stuff our rocks with the coal and oil that permits our population to exist at such a scale and with such mobility, and thus you and me to exist as we do.

In a mature biosphere, the marginal utility of intelligence must increase with time.

To the extent that intelligence can look for fruitful pathways deliberately, and thereby potentially more efficiently than natural selection, I think you are quite right!

I guess I replied to it now! 😅

And now back to your actual post:

All that is required is a slow, secular trend in evolution towards adaptive flexibility and overall capability (e.g., more effective vascular systems, or hox genes, or other adaptations that increase the range of viable body plans). The same, I would expect, is true of cognitive capacity.

Perhaps. I'm not completely sold. With the sole, asterisk-laden exception of humanity, I don't see any strong argument that highly-intelligent species are doing especially well compared to the rest of life on Earth, and I don't take it as a given that natural selection couldn't successfully deemphasize / render less intelligent a species which had formerly developed a noteworthy amount of intelligence. but this is probably an area where there is lots more existing data than I am aware of, and so I don't really want to make any bold statements.

Okay, switching topics, here is where I get more assertive:

I do, respectfully, disagree that civilization elsewhere in the Milky Way would be hard to notice.

You go on to say:

For a "near" (call it an approximately Star-Trek-like) future, I'd agree with you; space stations, directed tight-beam communications, modestly sized ships and megastructures, planet-based cities or a few ring stations, sure, I'll happily agree that these could be missed by the best telescopes of today. But that's an imagined future of, what, a few hundred, a few thousand years from now maybe? What about fifty million? Are we to imagine that the future will hit a space-ships-and-interstellar-governments stage and then just stay there until the stars burn out, that there's nothing else beyond that?

There are a few different things to disentangle here which should be considered separately. I had said, as a relevant afterthought to my main post:

I wouldn't put much stock in the fact that there is currently no evidence for the existence of other advanced life.

My point was that we haven't been looking very long, and we also haven't been looking very well. I said:

We'd either need to improve our detection capabilities by many orders of magnitude, or continue our present detection efforts for many orders of magnitude longer than our present efforts have lasted, or a combination of both.

What you are saying at can be looked at from either side of the equation:

If you're saying that if we give humanity fifty million years, then humanity will be able to much more confidently assess whether or not other advanced civilizations exist in the Galaxy (and perhaps even in the Local Group), I think that's an easy "yes" from me.

But if you're saying "Given that the Galaxy is more than 50 million years old, why don't we see signs of advanced civilizations right now?" then I would refer you to my original statement that we haven't been looking very long or very well.

If it's out there to be found—I think it probably isn't; but if it is—it could be right under our noses. It could be everywhere!

Laypeople flatly do not understand the present-day capabilities of astronomy. The pictures we see in movies and video games are meaningless. Contemporary astronomical data, coming through telescopes and particle detectors, is exceedingly...let's call it "rough." And I don't just mean that the raw data can be utterly daunting to look at (though it absolutely can!); what I really mean is that the data are thin. Incomplete. Filled with uncertainty.

The best way I know of to illustrate this, and the reason why I said that there could be an advanced civilization in our own Solar System and we wouldn't necessarily know about it, is that our own Solar System is still largely a mystery to us. Just a few months ago we got a study saying that Neptune might be a completely different shade of blue from what we thought. A little farther back there was a big question about the atmospheric composition of Venus and whether it might be a sign of life. There are tons of menacing asteroids we don't know about yet, along with many orders of magnitude more non-menacing ones. We still don't understand basic questions about the boundary of the Solar System.

This is all right here in our own celestial back yard. Looking farther afield, while our great telescopes show us all kinds of stars and nebulae and other wonders, there are many others that we can't see yet. Some that we won't be able to see at all for a long time due to intervening objects. Just a couple weeks ago I read a report suggesting that our preordained collision with Galaxy Andromeda a few billion years from now might not happen even remotely as has been thus far anticipated—if at all!

If stars, which are literally burning balls of fire with the mass of solar systems, are difficult to see, then what of artificial activities? I'm pretty well-versed in some of the marvelous science-fiction spectacles of possible technologies. I have a lot of fun with that stuff in Galaxy Federal! But a lot of it simply wouldn't be visible from very far away unless you were looking very hard for it, i.e. with good equipment over a sustained time period. If, at this moment, the Galaxy actually were full of advanced spacefaring civilizations, there might be no indication of it to us within our present means of detection. In many cases this would even hold true if we were specifically to point our telescopes in exactly the right direction. There just isn't enough light to capture the nuances of artificial structures and modifications of celestial bodies.

So far, the best we can do is rule out the super-duper conspicuous stuff within a relatively close interstellar radius. And generally speaking, an advanced civilization is not going to be broadcasting evidence of itself that is deliberately as conspicuous as possible. They would only do that if it were efficient, or if they had specific reason to.

I recognize that I'm not necessarily disagreeing with you; I'm only pointing out that it is much harder than most people realize to presently see the likely signs (at least those signs which we know of to look for) of an advanced civilization at virtually any distance at all. We don't even know what's going on in our own Oort Cloud, or what color Neptune is.

So, if an advanced species is out there, we probably wouldn't know about it at present.

Anyway, I'll close out by quoting this from you:

Considered in geologic time, we ourselves are in the early stages of a massive explosion that is going to ripple through the universe around us and leave it utterly new; intelligence is simply too powerful a force for us to imagine that it is already in equilibrium with the cosmos. We are, for obvious reasons, anchored in a mentality in which we struggle against nature, tiny creatures wresting our preferences from an indifferent world inch by inch and fighting entropy and death the whole way. But that's because we're still small, and new. It won't always be thus.

I love this! This is the optimistic dreamer's gaze that I admire. I hope you're right! I hope that that future comes to pass in some form, and that it will be a world people want to live in, and other life thrives in.

Filters in the way of technologically advanced life in the universe and how likely I think they are

1. Abiogenesis (4.4-3-8 billion years ago): Total mystery. The fact that it happened so quickly on Earth (possibly as soon as there was abundant liquid water) is a tiny bit of evidence for it being easy. Amino acids and polycyclic hydrocarbons are very common in space, but nucleotides aren't, and all hypothetic models I've seen require very specific conditions and a precise sequence of steps. (It would be funny if the dozen different mechanisms proposed for abiogenesis were all happening independently somewhere.)

2. Oxygenic photosynthesis (3.5 billion years ago) (to fuel abundant biomass, and provide oxygen or some other oxidizer for fast metabolism): Not so sure. Photosynthesis is just good business sense -- sunlight is right there -- and appeared several times among bacteria. But the specific type of ultra-energetic photosynthesis that cracks water and releases oxygen appeared only once, in Cyanobacteria. That required merging two different photosynthetic apparati in a rather complex way; and all later adoptions of oxygenic photosynthesis involved incorporating Cyanobacteria by endosymbiosis. For all that it's so useful, I don't know if I'd expect to see it on every living planet.

3. Eukaryotic cell (2.4 billion years ago?): Probably the narrowest bottleneck on the list. Segregated mitochondria with their own genes and a nucleus protecting the main genome are extremely useful both for energy production (decentralized control to maximize production without overloading) and for genetic storage (less DNA damage due to reactive metabolic waste). But there's a chicken-and-egg problem in which incorporating mitochondria to make energy requires an adjustable cytoskeleton, but that consumes so much energy it would require mitochondria already in place. Current models have found solutions that involve a very specific series of events. Or maybe not? Metabolic symbiosis, per se, is common, and there may have been other ways to gene-energy segregation. On the other hand, after the origin of eukaryotes, endosymbiosis occurred at least nine more times, and even some bacteria can incorporate smaller cells.

4. Sexual reproduction (by 1.2 billion years ago): Without meiotic sex (combining mutations from different lineages, decoupling useful traits from harmful ones, translating a gene in multiple way), the evolution of complex beings is going to be painfully slow. Bacteria already swap genes to an extent, and sexual recombination is bundled in with the origin of eukaryotes so I probably shouldn't count it separately (meiosis is just as energy-intensive as any other use of the cytoskeleton). Once you have recombination, life cycles with spores or gametes and sex differentiation probably follow almost inevitably.

5. Multicellularity (800 million years ago?): Quite common, actually. Happens all the time among eukaryotes, and once in a very limited form even among bacteria. Now we'd want complex organized bodies with geometry-defining genes, but even that happened thrice: in plants, fungi, and animals. As far as I know, various groups of yeasts are the only regressions to unicellularity.

6. Brains and sense organs (600 million years ago): Nerve cells arose either once or twice, depending on whether Ctenophora (comb-jellies) and Eumetazoa (all other animals except sponges) form a single clade or not. Some form of cellular sensing and communication is universal in life, though, so a tissue specialized for signal transmission is probably near inevitable once you have multicellular organisms whose lifestyle depends on moving and interacting with the environment. Sense organs that work at a distance are also needed, but image-forming eyes evolved in six phyla, so no danger there (and there's so many other potential forms of communication!). Just to be safe, you'll also want muscles and maybe mineralized skeletons on the list, but I don't think either is particularly problematic. An articulated skeleton is probably better than a rigid shell, but we still have multiple examples of that (polyplacophorans, brittle stars, arthropods, vertebrates).

7. Life on land (400 million years ago): (Adding this because air has a lot more oxygen to fuel brains than water (the most intelligent aquatic beings are air-breathers), and technology in water has the issue of fire.) Plenty of animal lineages moved on land: vertebrates, insects, millipedes, spiders, scorpions, multiple types of crabs, snails, earthworms, etc. Note that most of those are arthropods: this step seems to favor exoskeletons, which help a great deal in retaining water. Of course this depends on plants getting on land first, which on Earth happened only once, and required the invention of spores and cuticles. (Actually there are polar environments where all photosynthesis occurs in water, but they are recently settled and hardly the most productive.)

8. Human-like intelligence (a few million years ago?): There seems to a be a general trend in which the max intelligence attainable by animals on Earth has increased over time. There's quite a lot of animals today that approach or rival apes in intelligence: elephants, toothed cetaceans, various carnivorans, corvids, parrots, octopodes, and there's even intriguing data about jumping spiders. Birds seem to have developed neocortex-like brain structures independently. Of course humans got much farther, but the fact that even other human species are gone suggests that a planet is not big enough for more than one sophont, so the uniqueness of humans might not necessarily imply low probability. (We seem to exist about halfway through the habitability span of Earth land, FWIW.) The evolution of sociality should probably be lumped here: we'll want a species that can teach skills to its offspring and cooperate on tasks. But sociality is also a common and useful adaptation: many species on our list (octopodes are a glaring exception) are intensely social and care for their offspring. I mentioned above that the land-step favors exoskeletal beings, which in turns favors small size; but the size ranges of large land arthropods and very intelligent birds overlap, so that's not disqualifying.

9. Agriculture and urban civilization (11,000 years ago): Agriculture arrived quite late in the history of our species, but when it arrived -- i.e. at the Wurm glaciation -- it arrived independently in four to eight different places around the world, in different biogeographic realms and climates, so I must assume that at least some climate regimes are great for it (glacial cycles are a minority of Earth's history; but did agriculture need to come after glaciations? Maybe a shock of seasonality did the trick). And once you have agriculture, complex urbanized societies follow most of the time, just a few millennia later. Even writing arose at least three times (Near East, China, and Mexico), and then spread quickly.

10. Scientific method and industrialization (300 years ago): We're getting too far from my expertise here, but whatever. The Eurasian Axial Age suggests that all civilizations with a certain degree of wealth, literacy, and interconnection will spawn a variety of philosophies. Philosophical schools that focus on material causes and effects like the Ionians or Charvaka have appeared sometimes, but often didn't win over more supernaturalist schools. Perhaps in pre-industrial times pure materialism isn't as useful! You may need to thread a needle between interconnected enough to exchange and combine ideas, and also decentralized enough that the intellectual elite can't quash heterodoxy. As for industrialization, that too happened only once, though that's another case in which the first achiever would snuff out any other. I hear Song China is a popular contender for alternative Industrial Revolutions (with coal-powered steelworks!); Imperial Rome and the Abbasid Caliphate are less convincing ones. For whatever reason, it didn't take until 18th century Britain.

11. Not dying randomly along the way: Mass extinctions killing off a majority of species happened over and over -- the Permian Great Dying, the Chicxulub impact, the early Oxygen Crisis -- but life has always rebounded fairly quickly and effectively. It's hard enough to sterilize an agar plate, let alone a planet. Disasters on this scale are also unlikely to happen in the lifespan of planet-bound civilizations, unless of course the civilizations are causing them. A civilization might still face catastrophic climate change, mega-pandemics, and nuclear war, not to mention lesser setbacks like culture-wide stagnation or collapse, and I couldn't begin to estimate how common, or ruinous, they would actually be.

****

I have no idea how common the origin of life is, but the vast majority of planets with life will only have bacterial mats and stromatolites. Of the tiny sliver that evolved complex cells, a good chunk will have their equivalents of plants and animals, most of which may have intelligent life at least on primate- or cetacean-level at some later point. At any given time, a tiny fraction of those will have agricultural civilizations, at an even tinier fraction of that will have post-industrial science and technology. Let's say maybe 1 planet with industrial technology out of 100 with agriculture, 100,000 with hominid-level intelligence, 10 million with animal-like organisms, 100 millions with complex cells, and 10 billions with life at all?

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pigeon Mail anyone? Pigeon Mail? Perhaps Crows? I'd personally really enjoy that, that would be so cool.

Ahhh, but this raises lots of good points, but you know, this kinda falls into the mental trap of the iCloud Fallacy, as I call it. Basically it believes that The Internet is some ethereal plane that is being conquered and colonized like it's a New New World we have just discovered, when really it's simply a highly complicated information and communication bank built out of cables and boxes all across the world, not a new landmass, but something greater, the culmination of all of human culture ingenuity and chaos, not new things, but what already exists further explored made easier and more accessible than ever, a development and upgrade to our already existing world, not a new world entirely. Another dimension unlocked. The thing is, your very limited view of the internet, is not the whole internet! Not by a long shot. There is an entire web out there completely untouched by corporations, which is mostly why you never hear about them.

Adding on to that, the concerns of AI agents can be easily dismissed with simple logic, you can logically deduce whether someone is a bot or not, and it is a skill you can train. There will never be robots indistinguishable from humans, because if there was, no one would know they were bots, not even their creators, as long as someone out there knows, the possibility to distinguish them exists. The fear of AI agents is not something that should be put much stock into, as the offensive technology is being made, defensive technology is developed in response, AI is not the nuke of the internet, (that nuke hasn't been invented... yet).

Just like the alternative to a McDonalds burger can be make your own burger, the alternative to the internet can be make your own internet. Don't want to buy heavily processed mixed meat of a thousand tortured cows? Buy locally from butchers and farmers who are transparent with their practices! Don't want to rent a server from a predatory server running business that wants to harvest your sites data? Don't! Run your own server or get in touch with groups of individuals dedicated to hosting their own servers in retaliation against the homogenization and monopolization of the internet.

I honestly just cannot stand this traditionalist/doomer mentality going around about abandoning the internet because it's infected or bad now, have you actually looked outside your doors?! The real world is just as bad and difficult to exist in, and part of the reason for that is because we've given it up! We can't make the same mistake with the internet and in fact taking back the web is the first step to taking back the world because of how foundational the web is to the world.

The alternative to "the internet" is a "local" internet. You don't have to disconnect from the web entirely, it's not the only option to escape the coming hell. You in fact simply missed a step there. You don't necessarily have to get into contact with your local community if you can just get into contact with like minded individuals and build your own internet community! All it takes is some initiative and head strength to get going.

There's specifically 3 videos I watched recently that really got me thinking about this in particular and helped culminate into these thoughts and responses. Those videos would be

A. The Web has lost its Soul - LOVEWEB

B. Stop using Fandom

and C. How Can We Bear to Throw Anything Away?

They're all incredibly relavent to my major point, but the tip of that point is no, you don't have to do that, but you do have to follow that spirit, just not in that exact way and in fact it would be better if you did not do that, did not give up humanities most powerful tool to the corporations and forfeit instant telecommunication and the foundations of so many communities and modern cultures, you're simply letting the corpos win by giving up the internet.

All that AI stuff and how capitalists attempt to use it makes me think we're going to start going offline. Let me explain.

The major thing is that labour is done by people, not by CEOs. They would yell at top of their lungs that they are the ones who make innovations possible, that the world would fall apart without their holy guidance. But at the end of the day they need us more than we need them. Otherwise they wouldn't put so much effort into suppressing unions, enforcing corporate culture that makes it somehow inappropriate to discuss your paychecks, feeding so much to police and army instead of really meaningful things such as health care and education, and so on and on and on. People who have other choices don't exchange their life for a possibility of having a decent income given by the army. They want us poor, sick and lonely.

That's here we go to the AI topic. I've come across a TikTok of a black woman who has exposed a business account using an AI model of a non-existent black person to disguise as a black owned businesses. Which means there's no real person from a marginalized group who's going to benefit from the sales. But there are people who want to make money on the people who belong to the said marginalized group.

The real power the working class has is ability to withdraw our labour. And now these guys at the top are desperately trying to deprive us of this power by replacing us with AI surrogates. Surrogates which would write scripts for the shows, do advertising, teach, play, design, draw, supposedly create things out of basically nothing. And you don't have to pay them, try to tame them, listen to their demands, consider their needs, put an effort into controlling them. Cause they aren't alive and have no needs and wants. Which brings me to the idea that we'll need to go offline and share our ideas in person, do things on material storage mediums and finally socialize and build meaningful connections within communities

16 notes

·

View notes