#djerba jews

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jewish Bridal Jewelry in Djerba

"Jewish brides on the island of Djerba were covered from head to toe in multiple layers of jewelry, creating a dazzling effect. The headgear (kufiya), composed of gold disks resembling coins, identified them as married women and distinguished them from their Muslim neighbors. The kufiya was part of the women's trousseau and was considered their own property, and they could use the gold disks in times of personal distress.|||The jewelry is typically adorned with motifs of barley seeds, fish, birds, and hamsas, believed to ensure the women’s fertility and ward off the evil eye; especially prominent is the crescent – a symbol of strength and renewal – whose two horns are attributed with the power to strike the evil eye."

#jewish history#tunisia#tunisian jews#djerba#djerba jews#bridal jewelry#jewish wedding#swana jews#mizrahi jews

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

1. Djerba, an island off the coast of Tunisia, Africa, stands like a citadel among an ocean of unrest. Besides being home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, Djerba is also one of the only Jewish communities living in a Muslim-dominated region. Locals work side-by-side and in relative harmony with their Muslim neighbors, speaking the local language of Arabic.

2. As equally fascinating as the age and locale of this 2,500-year community is the people’s ancestry. The unique community has been dubbed “The Island of Kohanim (priests)” since approximately 80% of the community is descended from priests, according to the biography From Djerba to Jerusalem. According to the book, following the destruction of the First Temple, the high priest Tzadok, along with his fellow Kohanim, escaped to this distant Island and settled there. Locals maintain that the priests carried a stone with them from the altar of the destroyed Temple, and incorporated it into the building of the famous synagogue, the El Ghriba synagogue.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish bride and her mother in Djerba, Tunisia, 1983

The Tunisian Jewish bride was hennaed first by her mother-in-law, and then the following day again by a professional artist. The bride would sleep with the henna and strings overnight. In the morning, the women come to the bride’s house to check if the henna came out nicely; if it is good, they kiss her fingers and praise her beauty. If the colour is not strong enough, then they henna her again; all in all, the bride is hennaed about four or five times over the course of a week. The Jews of Djerba continued this tradition well into the 20th century.

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

el ghirba synagogue in djerba, tunisia. when exactly it was founded is unknown, but it may date to the 6th century bce, making it the oldest functioning synagogue in africa (and possibly in the world). it's associated with toshavi jews, the maghrebi jewish community which predated the arrival of and was eventually absorbed by expelled sephardic jews.

#tunisia#architecture#interior#worship#jewish#sephardic#my posts#yes this is the synagogue there was a shooting in a few months ago#please dont yell at me for not mentioning it in the post

438 notes

·

View notes

Note

"indigenous tunisian jews" 💀 help

i said this in another post i need to find but trying to apply indigenous/settler dynamics to TUNISIA out of all places... a lot of non-livornese jews were sephardic as well n a lot of those that werent were arabized, not "indigenous". like there r amazigh tunisian jews (they r more prevalent in morocco n algeria) but they r a small minority. even the jewish community of djerba, which is the oldest jewish community in tunisia and one of the oldest jewish communities in the world, were said to arrive either following the carthaginian conquest (9th century bc), or fleeing after the destruction of the first temple (6th century bc), and werent from the "indigenous" amazigh population. trying to fit pre-french-colonialism tunisians into indigenous/settler dichotomy is insane considering the nature of the carthaginian, roman, vandal, byzantine, arab and ottoman conquests n taking into account arabization and such. like amazigh tunisians r v much indigenous but its impossible to say who the 'settlers' r using this dichotomy.

it showcases such a misunderstanding on how minority communities, esp those descended from immigrants, esp jewish communities, survive culturally and historically. like imagine calling greek or bulgarian or romanian sephardim racist colonizers, even tho its a similar case there too. but didnt u know that whenever a person from "europe" moves to "non europe", nomatter how or when in history, its inherently bad and colonialist.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jews of Djerba. Blue Bride, by Keren T. Friedman (Djerba, Tunisia, 1983)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last night I posted this then deleted it as I was told it was not a terror attack but turns out it might have been.

Last night in a synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia, where many tourists go annually to celebrate Lag Ba'Omer, 2 Jews and a security guard were murdered. One of the Jews living in Tunisia was an Israeli citizen.

The terrorist was an officer, affiliated with the National Guard naval center, who first turned his service weapon on a colleague, before grabbing more bullets and making his way to the synagogue.

When he reached the area, he began shooting wildly at security units stationed at the synagogue, who responded with gunfire, killing him. The synagogue was locked down and those inside were kept secure.

Baruch Dayan Ha'Emet

Aviel Hadad and his cousin Ben Hadad are the 2 Jews who were murdered in Tunisia last night by the terrorist.

May their memories be for a blessing

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

(JTA) – A historic but defunct synagogue in Tunisia was reduced to rubble on Tuesday amid mass rioting after an explosion in Gaza that Hamas blamed on Israel.

Hundreds of people were filmed setting fire to a synagogue in the central Tunisian city of Al Hammah in the hours after the explosion, at a Gaza City hospital where Hamas said many people died. Videos that circulated widely on social media showed people planting Palestinian flags and chipping away at the synagogue building’s stone walls, all without any police intervention.

Some users shared the video of the arson alongside a “#Palestine” hashtag. A video taken Wednesday shows heavy damage to the site, including to the fenced-off grave of a 16th-century rabbi that been a historic pilgrimage site for some Jews.

The incident, which has deprived Al Hammah of a key vestige of its Jewish past, comes amid attacks on other Jewish and Israeli sites around the world — including Germany, France, Portugal, China, and Australia — as Israel retaliates in the Gaza Strip following Hamas’ sweeping, deadly attack on Israel Oct. 7.

Protests against Israel ramped up Tuesday night after the hospital explosion. Dozens of rioters targeted the Israeli embassy in Amman, Jordan. Riots also broke out in Palestinian areas of the West Bank, Hebrew media reported.

Israeli and U.S. officials said they believed with near certainty that the blast was caused by an errant rocket fired by Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

The Al Hammah synagogue was not an active site of worship, as no Jews live in the city; however, it is the site of the tomb of 16th-century Kabbalist Rabbi Yosef Ma’aravi. The same site was previously damaged during the 2011 Arab Spring protests, which were not about Israel.

The American Jewish Committee denounced the vandalism in a statement.

“We are horrified by the burning and destruction of the Al Hammah synagogue in Tunisia,” the group said on X, adding that it was “closely monitoring the situation” and in touch with Tunisian Jewish community leaders.

Tunisia’s small Jewish population of around 1,000 also contended with a deadly terrorist attack earlier this year when a gunman stormed a synagogue on the island of Djerba. Five people died, including two Jewish pilgrims who had traveled to the area from Israel and France, and wounding several others.

In response to the Djerba attack, Tunisia’s president, Kais Saied, pledged he would increase security for the country’s Jewish residents. Saied also drew criticism for using the occasion of the attack to criticize Israel.

Since the latest explosion of violence in Israel and Gaza, Tunisians have taken to the streets in large numbers to support Palestinians. Tunisian schoolchildren have saluted the Palestinian flag, and Saied has pledged to stand by Palestinians while continuing to snuff out any talk of normalization with Israel, a path that four Arab countries took in 2020.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the History and Experience of Tunisian Jews

SONY DSC This year’s El Ghriba pilgrimage celebration on the island of Djerba will be subdued, with festivities limited to the El Ghriba synagogue itself. This comes in the wake of the tragic events in Gaza, creating an understandably somber atmosphere. The presence of Jews in Tunisia dates back over 2,000 years, with their population peaking at over 100,000 in the mid-20th century. Their…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

George Ashford

10/11/2023

Reflection

Traveling through Tunisia, I saw the marks of the many cultures that have found a home here throughout history. A Roman coliseum. Amazigh villages carved into the desert. A Sunni mosque made of Roman columns and a Shi'a fortress guarded by Ottoman cannons. The monumental art-deco and brutalist structures of the capital. An ancient synagogue rumored to contain stones from another, even more ancient temple that stood where Abraham obeyed and Isaac was spared. They tell a story that spans thousands of years, a story of colonization, assimilation, war, and the advent of a nation.

One part of the story begins on the island of Djerba. The Ghriba Synagogue, purportedly the oldest Jewish site in Africa, sits near the center. No one knows for certain how old it is, but legend has it that the high priests of the Temple Mount fled to Djerba after Nebuchadnezzar and the Bablylonians sacked Jerusalem, carrying a stone and a door from the First Temple to build anew. As he shows us around a traditional Amazigh house, dug two stories deep into the soft desert dirt, a light-eyed man in a baseball camp explains that his people were once Jewish. That is why they sheltered Jews during the holocaust, he says, pointing to a metal helmet from WWII hung on a stick bannister. With a few exceptions, the Amazigh are not Jewish anymore, as evidenced by the woman in hijab who serves us tea while we watch the sunset wash over the small circle of sky visible from the open pit at the center of the house, but the man is proud to tell us that they once were. He is staking a claim to Tunisia’s story, reminding us that it began before the Arabs arrived, and that his ancestors were here before Islam. Although he does not make it a point to tell us, they were here before Judaism too.

In Kairouan, conquests are layered onto one another in the very foundations of the city. As we look out over the massive cisterns that held the water for the ascendant Umayyad caliphate’s first outpost in the region, we learn that it gets its name from the Arabic word for a military caravan. The outpost was to protect the new settlers from the Amazigh, who staged a series of successful rebellions before being defeated and gradually converting to Islam. We do not have to explore Kairouan for long, however, to see that the The Umayyads were not the first conquerors to make their mark here. The columns of the majestic Great Mosque of Kairouan are carved in the Greco-Roman style, clearly repurposed from older buildings. Some of the stones in the outer wall have latin writing on them. 70 kilometers away, closer to the coast, the towering Roman amphitheater in El-Jem testifies more explicitly to the power of the empire that counted this part of North Africa among its first and hardest won territories.

After El-Jem, we stop in Mahdia. The insurgent Fatimid caliphate, tracing their lineage back to the Prophet’s daughter, founded the city as their first capital a few hundred years after the Umayyads founded Kairouan. They would go on to capture Egypt and the rest of North Africa from the ruling Abbasid dynasty, spelling the end of a united Arab empire in the Mediterranean. We walk along the parapet of a fortress looking out over bright blue ocean on three sides. We imagine seeing

ships coming over the horizon and scrambling to man the defenses, as so many must have over the centuries. Genoese, Norman, Spanish, French, and Ottoman raiders all came by sea to Mahdia, its well-fortified harbor making it a prime toehold for a long line of would-be conquerors.

The latest conqueror in that line is most visible in Tunis, where art-deco facades adorn the most prominent buildings in the city center. It is also audible in the French words and accent woven into Tunisia’s unique dialect of Arabic. Tunis also, however, tells of something new. Hulking government buildings and hotels made from the ubiquitous concrete of the late 20th century overlook Habib Bourguiba Avenue. They proclaim the sovereignty of a people that is not quite of the ancient desert tribes nor any of their conquerors. Our professor points out the site of famous protests where Tunisians proclaimed a more personal form of sovereignty, demanding political freedom and economic opportunity and getting at least the former.

Tunisia is an Arab country. Hearing the language and the call to prayer every day make that clear, and Kairouan tells the story of how it became so. It is not, however, a solely Arab country, just as the story of Kairouan is not Tunisia’s only story. Djerba, El-Jem, Tunis, Mahdia, and the Amazigh villages tell other stories about Tunisia, stories that include elements of the French story, the Jewish story, the Ottoman story, the Roman story, and the story of the Amazigh. With revolution for national, and then for personal independence as the most recent chapters, they weave together into one, rich, cohesive, Tunisian story. It has been a fascinating story to learn these past few months, and I look forward to someday knowing it in more detail.

Expressions

One of the most common Tunisian expressions is to say صحة when someone is eating, gets out of the shower, or buys new clothes. The response is يا أتك صحة. The expression literally translates just to ‘health,’ and expresses encouragement of healthy activities like eating.

ما يْحِس بِالجمْرة كان الّي يعْفِس عْليها is a less common Tunisian proverb that translates literally to ‘only he who walks on embers can feel it.’ It expresses the idea that one should not judge or criticize the struggles of someone else, since it is impossible to know what they are really going through.

Photos

أركان رومانية في جامع قيروان الأكبر

George Ashford

10/11/2023

Reflection

Traveling through Tunisia, I saw the marks of the many cultures that have found a home here throughout history. A Roman coliseum. Amazigh villages carved into the desert. A Sunni mosque made of Roman columns and a Shi'a fortress guarded by Ottoman cannons. The monumental art-deco and brutalist structures of the capital. An ancient synagogue rumored to contain stones from another, even more ancient temple that stood where Abraham obeyed and Isaac was spared. They tell a story that spans thousands of years, a story of colonization, assimilation, war, and the advent of a nation.

One part of the story begins on the island of Djerba. The Ghriba Synagogue, purportedly the oldest Jewish site in Africa, sits near the center. No one knows for certain how old it is, but legend has it that the high priests of the Temple Mount fled to Djerba after Nebuchadnezzar and the Bablylonians sacked Jerusalem, carrying a stone and a door from the First Temple to build anew. As he shows us around a traditional Amazigh house, dug two stories deep into the soft desert dirt, a light-eyed man in a baseball camp explains that his people were once Jewish. That is why they sheltered Jews during the holocaust, he says, pointing to a metal helmet from WWII hung on a stick bannister. With a few exceptions, the Amazigh are not Jewish anymore, as evidenced by the woman in hijab who serves us tea while we watch the sunset wash over the small circle of sky visible from the open pit at the center of the house, but the man is proud to tell us that they once were. He is staking a claim to Tunisia’s story, reminding us that it began before the Arabs arrived, and that his ancestors were here before Islam. Although he does not make it a point to tell us, they were here before Judaism too.

In Kairouan, conquests are layered onto one another in the very foundations of the city. As we look out over the massive cisterns that held the water for the ascendant Umayyad caliphate’s first outpost in the region, we learn that it gets its name from the Arabic word for a military caravan. The outpost was to protect the new settlers from the Amazigh, who staged a series of successful rebellions before being defeated and gradually converting to Islam. We do not have to explore Kairouan for long, however, to see that the The Umayyads were not the first conquerors to make their mark here. The columns of the majestic Great Mosque of Kairouan are carved in the Greco-Roman style, clearly repurposed from older buildings. Some of the stones in the outer wall have latin writing on them. 70 kilometers away, closer to the coast, the towering Roman amphitheater in El-Jem testifies more explicitly to the power of the empire that counted this part of North Africa among its first and hardest won territories.

After El-Jem, we stop in Mahdia. The insurgent Fatimid caliphate, tracing their lineage back to the Prophet’s daughter, founded the city as their first capital a few hundred years after the Umayyads founded Kairouan. They would go on to capture Egypt and the rest of North Africa from the ruling Abbasid dynasty, spelling the end of a united Arab empire in the Mediterranean. We walk along the parapet of a fortress looking out over bright blue ocean on three sides. We imagine seeing

ships coming over the horizon and scrambling to man the defenses, as so many must have over the centuries. Genoese, Norman, Spanish, French, and Ottoman raiders all came by sea to Mahdia, its well-fortified harbor making it a prime toehold for a long line of would-be conquerors.

The latest conqueror in that line is most visible in Tunis, where art-deco facades adorn the most prominent buildings in the city center. It is also audible in the French words and accent woven into Tunisia’s unique dialect of Arabic. Tunis also, however, tells of something new. Hulking government buildings and hotels made from the ubiquitous concrete of the late 20th century overlook Habib Bourguiba Avenue. They proclaim the sovereignty of a people that is not quite of the ancient desert tribes nor any of their conquerors. Our professor points out the site of famous protests where Tunisians proclaimed a more personal form of sovereignty, demanding political freedom and economic opportunity and getting at least the former.

Tunisia is an Arab country. Hearing the language and the call to prayer every day make that clear, and Kairouan tells the story of how it became so. It is not, however, a solely Arab country, just as the story of Kairouan is not Tunisia’s only story. Djerba, El-Jem, Tunis, Mahdia, and the Amazigh villages tell other stories about Tunisia, stories that include elements of the French story, the Jewish story, the Ottoman story, the Roman story, and the story of the Amazigh. With revolution for national, and then for personal independence as the most recent chapters, they weave together into one, rich, cohesive, Tunisian story. It has been a fascinating story to learn these past few months, and I look forward to someday knowing it in more detail.

Expressions

One of the most common Tunisian expressions is to say صحة when someone is eating, gets out of the shower, or buys new clothes. The response is يا أتك صحة. The expression literally translates just to ‘health,’ and expresses encouragement of healthy activities like eating.

ما يْحِس بِالجمْرة كان الّي يعْفِس عْليها is a less common Tunisian proverb that translates literally to ‘only he who walks on embers can feel it.’ It expresses the idea that one should not judge or criticize the struggles of someone else, since it is impossible to know what they are really going through.

Photos

أركان رومانية في جامع قيروان الأكبر

كنيس الغريبة في جربة

كنيس الغريبة في جربة

0 notes

Text

Tunisian authorities downplay significance of Djerba synagogue attack

The attack of May 9 near the Ghriba synagogue on the island of Djerba, in which two Jewish pilgrims and three members of the Tunisian security forces were killed Tunisian President Kais Saied has denied that the attack of May 9 was anti-Semitic. Authorities have sought to downplay its wider significance, in a statement lacking transparency. “They speak of anti-Semitism, while the Jews were…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

7 October distances young Jews from their Maghrebi roots

Most Jews in France have North African roots, and there has been a tendency among the young generation to re-connect with Tunisian, Algerian and Moroccan culture. But the 7 October massacre has created a cleavage with non-Jewish Maghrebi friends, Slate reports. The situation in Tunisia can only deteriorate further as its president, Kais Sayed, reinforces his holdon power.

The annual Ghriba pilgrimage, already scaled down in 2023, was shattered by a terrorist attack

This is the case of Diane’s paternal family, who lived in Tunisia for fourteen generations. Through her daily Arabic words, her grandmother triggered a deep awareness in Diane a few years ago. Her family’s history is much more “oriental” than French. In search of her origins, Diane went to Tunisia in May 2023. She realized that her family’s values - the warmth of human relationships, the attention paid to the well-being of others – inhabit Tunisian society.

At the Jewish cemetery of Borgel, in Tunis, Diane meditates on the tomb of her ancestors. “I also wanted to finally discover the places where my parents had grown up. I was trying to rebuild an identity.” Tears interrupt her story. In Sephardic Jewish families, the attraction of the youngest to the country of origin often meet disapproval from their parents. For Diane’s mother, her daughter’s journey was painful.

Confirming her mother’s anxieties, an attack was committed at the same time on the Tunisian island of Djerba. On 9 May 2023, a radicalized Tunisian policeman carried out an attack near the Ghriba synagogue in the midst of the annual Jewish pilgrimage. He killed four people. Diane was there, as was Sarah, who survived the shooting. A convert to Islam twelve years ago, this Jewish-Tunisian has several identities. “But this anti-Semitic attack reinforced my Jewishness, as if I was lashing out in self-defence,” the young woman says.

For many Jewish-Tunisians, the trauma of the Ghriba is mixed with that of 7 October 2023. On that day, Hamas fighters killed more than 1,200 Israelis, the majority of them civilians. According to the United Nations, militias from Hamas, the Palestinian Islamist movement, committed rape, including gang rape.

The shock of the massacre and its perception in Tunisia inflicted a second wound on Emmanuelle, a French Jewish-Tunisian. “In a crazy joy, Tunisian youth seem to have experienced this event as a great evening of national liberation for the Palestinians,” she sighs. “I understand the solidarity with the Palestinian people very well,” she adds. “But I believe that it masks a great hatred towards the Jews.”

A hatred that seems to grow in tandem with the bombs raining down on the Gaza Strip. On 17 October 2023, in southeastern Tunisia, the El-Hamma synagogue was reduced to ashes, causing shock among the Jewish-Tunisian diaspora, which is very connected on social media. Mikhael, 40, also thought he would make Tunisia his second family. “But I understood the message that my mother and her parents received when they fled this country: ‘We don’t want you here. Without you, it’s better…'” His maternal family left Tunisia in 1968, after individuals tried to burn down the family home.

Today, the anti-Semitism observed among some Maghrebis is born from a combination of factors: rejection of the existence of Israel, coupled with a confusion between Israel and Jewishness. But by proclaiming itself the representative of the Jews of the world, Israel has greatly reinforced this confusion, remarks the Franco-Tunisian historian Sophie Bessis. Anti-Zionism – seeing the establishment of a Jewish state as a historic mistake– exists in the spectrum of Jewish opinion. But it remains a minority view.

“Dissociating Jewishness from Israel is complicated,” the people we interviewed confirm. Most of them remain attached to Israel. “My father always said: ‘The fate of the Jews is is that they may have to leave at any moment.’ And Israel appeared to be the only place where we would be protected,” explains Diane.

Online, the Israeli flag displayed by Mikhael on his profile picture creates a gulf with most Internet users of Maghrebi origin. Fellow citizens, to whom “I nevertheless feel culturally so much closer than to other French people,” he admits. By way of explanation, he cites couscous, sacred to him or indeed his family. But that’s not all. In Quranic recitations, Mikhael finds the sounds of the Sephardic liturgy. An avowed “Zionist”, he loves the Arabic language to the point of listening to the surahs of the prophet Muhammad in his car.

Read article in full (French)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Jews of Djerba, Tunisia, 1981. Photographed by Jan Parik.

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

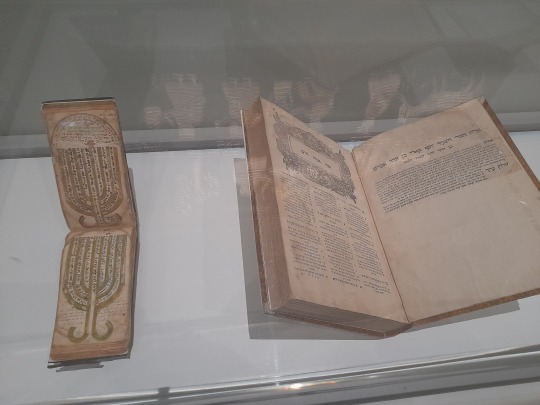

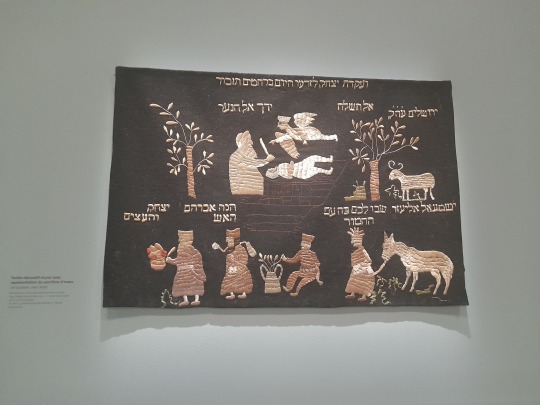

2022 : Back to the exhibition on Jews from the East.

On the way of my researches as well as my month-trip project to Mardin, I wanted to put over the light the Jewish community of Turkey and beyond.

Usually, as we talk about this community, people emphasizes Istanbul or Izmir ( where there are still an important population) . However, all the East part of the country were inhabited by Jews who share much cultural similarities with Assyrian, Aramaïc Christians populations. In this case, many of them have created together a political-cultural alliances in Israël as well as ensuring an Assyrian state.

The Jews from High Mesopotamia were completely different than those from cities such as :

They talk in Aramaïc instead of Ladino. In fact, the Jews of Istanbul are Sepharadic. Certainly, there are others from Europe and Russia so on but the majority of them are Sepharadic. By the way, " The Club", a successful serie on Netflix, recounts their history in this city.

youtube

As for the Jews from the Southern part of Turkey, I high recommend this fairly interesting book :

The anthropologist Süleyman Şanli pointed out all customs, memoirs, cultures as well as history migration of those Jews who live nowadays in Israël. I really appreciated the quality of interviews. Besides the Southern part of Turkey is the one of the famous cradle of Aramaïc identity, there are not enough researches about those populations.

Congrats to Süleyman as well as to Mardin University !

As I used to end working early Fridays, I used to follow some exhibitions in Paris to develop my culture knowledge. Plus, it sounded interesting for suggesting scholar trips relative the History/ Geography program.

At this time, I taught for the first level at High school.

One of chapter of our program concerned the Medditerrean civilisations as well as religions. As you know, I am fascinated by Aramaïc populations so that I was interested in following the exhibition of Jews from East organised by IMA.

IMA : Institut du Monde Arabe equivalent in English, The French Institute for Arabic world is still under the supervision of Jack Lang, who was the ancient Minister for Youth as well as Culture.

I was thrilled to meet Benjamin Stora, the famous historian who is good at Algerian history. He was interviewed by lots of medias to give further details and give his opinion about this exhibition.

youtube

This one lasted for a long time and plenty controversies emphasized the political dimension between Israel and the Arabic world.

By the way, this exhibition brings to my mind positive memories so that I would like to share some personal pictures.

I really appreciated the quality and varitey of pieces which were put over the light the daily lives of Jews.

My favorite ones was an audio of Jews from Lebanon who were cantiallating the Book as well as religious poems in Arabic. I haven't found it through nowaydays but you are able to listen this Passover recitation extract :

Passover Recitation Ehad Mi Yodea in Arabic - Min Yaalam UMin Yedri - Baghdad way.

Have a look at this INA documentary relative to Jews of Djerba in Tunisia.

youtube

0 notes

Text

actually this post is annoying me somewhat bc it v much treats tunisia like theres no antisemitism there and never was. it ignores why the pilgrims visiting djerba are pilgrims and not residents and going uwu the government officials and other tunisians love the jews like its not a constant hub of antisemitic hatecrimes including literally yesterday and nobody does shit

50 notes

·

View notes