#deconstructive interrogation of law

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Saul Newman - Derrida’s Deconstruction Of Authority

Title: Derrida’s Deconstruction Of Authority Author(s): Saul Newman Date: 2001 Topics: authority critique deconstruction Derrida language post-anarchism post-structuralist Notes: Originally appeared in Philosophy & Social Criticism, vol 27, no 3. Source: Retrieved on September 14, 2009 from www.infoshop.org Saul Newman Derrida’s Deconstruction Of Authority Abstract: This article explores the…

#absolute break#absolute transgression#anti-authoritarian politics#anti-authoritarian thought#authenticity#authoritarian identity#authoritarianism#authority#authority of law#beyond being and becoming#beyond good and evil#beyond truth and error#binary hierarchy of speech/writing#binary opposition#binary structures#classical revolutionary politics#contaminated#death of Man#deconstruction#deconstruction is a strategy of responsibility to the excluded other#deconstructive interrogation of law#deconstructive politics#Derrida’s an-archy#différance#differance#discourse of emancipation#discourses of domination#dispersing the subject into fragments and effects of discourses#displacement#double writing

1 note

·

View note

Text

Saul Newman - Derrida’s Deconstruction Of Authority

Title: Derrida’s Deconstruction Of Authority Author(s): Saul Newman Date: 2001 Topics: authority critique deconstruction Derrida language post-anarchism post-structuralist Notes: Originally appeared in Philosophy & Social Criticism, vol 27, no 3. Source: Retrieved on September 14, 2009 from www.infoshop.org Saul Newman Derrida’s Deconstruction Of Authority Abstract: This article explores the…

#absolute break#absolute transgression#anti-authoritarian politics#anti-authoritarian thought#authenticity#authoritarian identity#authoritarianism#authority#authority of law#beyond being and becoming#beyond good and evil#beyond truth and error#binary hierarchy of speech/writing#binary opposition#binary structures#classical revolutionary politics#contaminated#death of Man#deconstruction#deconstruction is a strategy of responsibility to the excluded other#deconstructive interrogation of law#deconstructive politics#Derrida’s an-archy#différance#differance#discourse of emancipation#discourses of domination#dispersing the subject into fragments and effects of discourses#displacement#double writing

1 note

·

View note

Text

Year 4560. Contact war.

current year 4578. Interview of klokian heavy mechanized frontline support unit 681th divison.

specie: kloakian. Name: Rak’zaer crasl.

I remember the first war we had with the humans clear as day. I think the whole galaxy does. While war isn’t something new to us since the galactic council are well, what they say peace keepers but they work more to keep the status quo between all the species which is a constant struggle of making sure the more malevolant empires dont do anything rash. It’s a constant struggle between border frictions, rebellions and sometimes civil war. safe to say galactic scale politics are a complete mess and sometimes well…let’s just say things can get disturbing.

the first contact war is a great example and one we all learnt from dearly. When the graktukian empire discovered that one of their holy worlds as they call it had been colonized they were not happy at all. Standard procedure would be to contact this new specie and inform them that they had to leave the planet. What we were not aware off was that the empire had taken matter into their own hands and eradicated the settlement using a specialised deconstruction lance, breaking the humans and their buildings down into their molecular structure.

We later heard that they had captured some what they call heretics and after vigorious interrogation they found out that they were a specie called ”homo sapien” or ”human”. With the Grantukian empire being very influential both politically and militairily they somehow managed to get the council to overlook this breach of galactic law due to the humans ”defiling their holy world”. Still think it’s valorkian Dungbeetle behavior.

Especially when they decided to declare a fullblown war with the new ’human’ specie. A war that cost them a bit over sixty planets before a truce were declared. The humans only lost ten, six of which were captured planets they took from the Graktuka.

I was on about three planets the humans invaded, but the planets they were defending? There’s a reason why i have prosthetic leg arm, and three prosthetic organs.

Human space technology is rather primitive by our standards, they’re slow dont have shields and instead rely on thick hull instead off energy based kinetic impact shields. So how did they defeat Top of the line Graktukian destroyer fleets? You see Graktukian ships are not in anyway weak. But most of the ships fleets they they have are categorized as a striker fleet, fast manouverable, small and very dangerous if they got up close because they would drop EMP class K bombs. Their tactic was to get up close shields up and get into middle of the fleet, drop the bombs and move away to get into position to fire their lance weaponry from afar.

what they didn’t expect were that a human railguns completely ignored shields. While their hull wasn’t thin it did not hold up when what was essentially a volley of needle shaped projectiles going close to light speed pierced their hull nearly cutting their ships in half.

I’ve read their reports of that first engagement and the amount of energy generated by the human ships were that of a red giant sun. How they managed to get the literal power of the sun into their primitive ships without causing a black hole is still baffling to me. Their space technology is rather primitive but their energy generation is on a whole other level compared to ours. We guess that those ships have to be simple so that the Miniature star they have onboard dont implode on itself due to overuse. Given their reputation i would assume they learnt that the hard way. And the radiation their miniature star generators acted as a natural form of isolation for energy meaning they were EMP immune unless you managed to get directly in said ship.

When we found out that they essentially destroyed an entire Graktukian striker fleet, the Graktukian high nobolity realized that they needed help. I know there was some very foul play involved to get the council onboard with this but noone has any evidence. Mostly because they were declared heretics and died under a number of incidents. This went on and on. with some big victories for us destroying their main dreadnought fleets utilizing classified weapons managed to siege high value planets.

At this point we were not aware that humans were a predator specie, when we made it onto the planet via translocation beacons because planetfall by conventional means were deemed impossible due to the quite honestly unhealthy amount of surface to air weaponry, which put most fortress worlds seem like a agricultural world.

Even via translocation the initial forces were ambushed and only by sheer coincidence did they manage to set up a very rudimentary ground only when the kinetic shield generators were set up. Even then we lost over 20 000 militairy personell in just 3 weeks. We managed to overwhelm their defences by saturated orbital bombardment. Even then, they managed to ambush and raid numerous of our operation bases.

I deployed on the 4th week on the planet. In all my cycles of service i have never witnessed such chaos, supply lines cut off, ammunitions sabotagued. Once the shield generator broke down and the Shield gen mechanic tried to fix it but we had to request another one because the damn thing was sabotaged, never seen a mechanic that angry and baffled before.

about 8 years of us going back and forwards between occupying system and taking it back both sides were exhausted from war, in total about 300 billion casulties were documented.

It was a bloody war, and i am glad we managed to negotiate a cease fire. fragile as it was. I dont know how i feel about fighting for what effectively was a mistake that the humans had no way of knowing of. I’m just saying alot of things were off about that war and i’m not sure if we were on the rightside in that war. Maybe i’m just growing to be more critical of it all.

interview concluded

#humans are space orcs#long reads#this is a sequal to my humans are poets as well as warmonger post#hope you enjoy(ed) reading this :)

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The surge of anti-Semitism is a symptom of the decay of democratic habits, a leading indicator of rising authoritarianism. When anti-Semitism takes hold, conspiracy theory hardens into conventional wisdom, embedding violence in thought and then in deadly action. A society that holds its Jews at arm’s length is likely to be more intent on hunting down scapegoats than addressing underlying defects. Although it is hardly an iron law of history, such societies are prone to decline. England entered a long dark age after expelling its Jews in 1290. Czarist Russia limped toward revolution after the pogroms of the 1880s. If America persists on its current course, it would be the end of the Golden Age not just for the Jews, but for the country that nurtured them.

I also began my undergraduate studies in the late-'90s, just a few short blocks from Columbia University. My memories of the time and place are not so rosy as are Mr. Foer's. I remember a humanities lecture being disrupted by a student revolt because it focused on the Holocaust. This was back when everything was called a "Holocaust" except the actual Holocaust, and unsurprisingly the Holocaust was equated with New York State's prison system. Bad as carceral culture is, it is not the Holocaust. Columbia had its LaRouchists camped forever outside. Friends at CCNY were taught that people like me were fake Jews and responsible for slavery by faculty approved by the likes of Leonard Jeffries. Academia, even then, was a setting where antisemitism retained respectability, provided it was couched in radical enough theory and jargon.

Yes, Jews are the canaries in the coal mine when it comes to liberal backsliding, the first to be othered, antisemitism the first bigotry to be destigmatized. But it has likewise been a very long time since American academia has been committed to the liberal project; longer than I've been alive, I'd reckon. My experience is of an academic humanities and some social sciences mobilized to problematize, deconstruct, and dismantle liberalism; of instructors who had appointed themselves radicalizers and indoctrinators, not critical guides in teaching how to think, how to interrogate all texts.

This conflict between the university's traditional liberal role of hosting reasoned debate among a diversity of ideas, and faculty and students who wish to create intellectual monocultures of goodthink on campus, will ultimately cause the collapse of the Ivory Tower. It has for too long tolerated doctrines intolerant of dissent or argument. The Fourth Estate tried to hold the lines of liberal democracy, until the internet democratized media and the mob went where it could find the maximum bias confirmation, be pointed towards the old classic villains to explain all personal and social failings. Now both demagogical extremes may blame different Jews, but in the end, they both blame Jews for America's problems. And where are our old defenders? Where have they ever been? Have we ever had defenders?

In 1968, when a local New York City public school board tried to fire an almost-entirely Jewish group of teachers, who defended them? The largely Jewish-led union. But unions don't care as much about Jews anymore, not when they're more preoccupied with international events than with the welfare of their members here at home - just ask the Jewish teachers harassed and threatened at Hillcrest and Origin High Schools how vocal their union has been in their defense, and against DOE attempts to whitewash bias incidents.

American Jews sought influence in our liberal environment for our own protection, but that liberalism has required us to cede some influence to those who also know marginalization. At the local level, this has made us again vulnerable.

That said, liberalism is a mixed blessing for Jews. It offers us the opportunity for individual advancement as far as our talents will allow, without having to renounce our Jewish identity. Yet at the same time, Jewish identity isn't really individual, it's grounded in community, in family and public ritual. At heart, ours is a tribal and insular culture. The more we're accepted, the more diffuse our connection to the community becomes; when under disability and persecution, we huddle together and renew our dedication to our people and to the intergenerational transfer that is our future. Whatever happens in America, we will survive - Am Yisrael hai. American liberal democracy, and that of any country that turns on its Jews? About that I'm not so sanguine.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

@protectmypeople ://

—☾—

The crowns of ancient maples are wet and black under the scratched mauve hull of sky. A sky ruled by the dark moon. The underbrush holds its breath. The wind howls with wolves, and blows through the open window of a stolen 1994 Dodge Ram Van, where the unconscious threat bound to the scaffold of a deconstructed car seat stirs to gold dice clinking on the rearview mirror.

Tang of rubber and pine, stale wax paper. Piles of books and yellowed, mummified gazettes, husks of flora suspended from a wire stabbed and stretched across the foam ceiling. The emptiness and fullness of a stranger's makeshift living space; the foam board and sleeping bag rolled into the shape of a body and folded into the backseat to make room for his.

The way the stranger hunches, his broad yet hollowed shape, he could be an iron fixture built into his vehicle. Only his scleras seem visible, the hard black shells within them, glinting out from the dark like the slightly upturned blades of bowie knives.

Many minutes pass before his mouth moves, and the stranger's voice is a molasses, a low and gentle timbre that drips between great pauses. Yet his interrogation begins without ceremony.

"What was your car doing parked outside this trail for three nights?"

The threat can't answer gagged. Makes muffled sounds the stranger seemingly deciphers.

"I know." The stranger pauses. "You weren't pursuing me. You have no idea who I am. Agent…"

He jimmies the badge. Brown gloves, stained thumbs—"B-E-L-L-A-M-Y. Special Agent Bellamy Blake. Issued in Washington D.C.."—and drops it onto the crease between Blake's thighs.

"What were you doing, Special Agent Blake? You have no jurisdiction here."

'Here' could mean the van or the dark of the woods. By the furor lurking under his stoic face, the stranger refers to something far beyond the laws of man, let alone New England.

"We're interstates." He lifts his head, parting his lips to lap at some potent, arcane power in the stormy air. A long pause. "Between New Hampshire and Massachusetts. An old college friend of yours lives there. The Ren told me. Hm."

His belief is so strong and permeable, this Ren seems to form in the small, cold pit of the van, dangling its hooked arm from the driver’s side window. With a strange, stilted gulp, the stranger sifts through rubbish. His hide-brown fingers pull a map from its contents, point to a speck of green among a topographical lexicon of tiny hand-drawn symbols.

"Mm." The stranger leans to expunge the balled-up t-shirt and tape from the mouth of the threat. His body musky and warm, his waffle shirt somewhat tacky to the touch, ripe with the earth, as if he'd clambered out of a shallow grave. "You have to answer my question now."

#protectmypeople#m. au | murder!kylo: the dice killer#closed starter#thread tbd#queue de la k#edited: for quality assurance

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

What to expect after critical race theory

After critical race theory, the discourse might continue to evolve in several directions. Here are a few potential paths:

Intersectionality: Intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, explores how different forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, classism, etc., intersect and influence each other. It examines the interconnected nature of various social identities and how they shape individuals' experiences.

Decolonial Theory: This theory focuses on challenging colonial structures and ideologies, particularly in the context of post-colonial societies. It critiques the ongoing impacts of colonialism on social, economic, and political systems, and advocates for decolonizing knowledge, institutions, and practices.

Feminist Theory: While critical race theory intersects with feminist theory, there's room for deeper exploration of gender dynamics within racial discourse. Feminist theory examines power imbalances related to gender and advocates for gender equality and the dismantling of patriarchal structures.

Transnationalism: This perspective looks beyond national borders to examine how global processes, such as migration, globalization, and transnational social movements, shape racial dynamics. It explores how racial hierarchies operate on a global scale and how people navigate multiple identities across different contexts.

Critical Whiteness Studies: This field interrogates the construction and perpetuation of whiteness as a social category and power structure. It examines how whiteness intersects with other social identities and privileges, and it seeks to deconstruct the norms and assumptions associated with whiteness.

Legal Studies: Given critical race theory's roots in law, further exploration within legal studies could involve examining how laws and legal systems perpetuate or challenge racial inequalities. This could include discussions on racial disparities in policing, incarceration, access to justice, and the impact of legal rulings on marginalized communities.

These directions are not mutually exclusive, and scholars often draw on multiple theoretical frameworks to analyze complex social issues. Additionally, the evolution of critical race theory itself will likely continue as scholars engage with new developments, challenges, and perspectives in the study of race and racism.

Co-opting these issues for self-serving or harmful purposes, such as promoting a discriminatory agenda or exploiting marginalized communities for personal gain would be highly unethical and harmful. Here's how one might hypothetically attempt to do so

Misrepresentation: Misrepresent the goals and principles of social justice movements to advance a different agenda. This could involve distorting the meaning of terms like "equality" and "justice" to promote discriminatory or oppressive policies under the guise of promoting fairness or meritocracy.

Divide and Conquer: Exploit divisions within marginalized communities or between different social justice movements to undermine solidarity and collective action. This could involve pitting marginalized groups against each other or co-opting leaders to advance a divisive agenda that serves the interests of the oppressor.

Tokenism: Tokenize members of marginalized communities by giving them superficial representation or visibility without addressing the underlying power structures or systemic inequalities. This could involve using diversity initiatives or symbolic gestures to create the illusion of progress while maintaining the status quo.

Gaslighting and Discrediting: Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation that seeks to make individuals doubt their own experiences and perceptions. Those seeking to adversely take over social justice issues might engage in gaslighting by denying the existence of oppression or blaming marginalized communities for their own marginalization. They may also discredit activists and scholars by attacking their credibility or spreading misinformation.

Selective Solidarity: Selectively support only those aspects of social justice that align with one's own interests or agenda while ignoring or opposing other forms of oppression. This could involve co-opting language or symbols associated with social justice movements to gain legitimacy or popularity while actively working against the goals of those movements.

0 notes

Text

Gosh so much all of this.

Like hell, even without getting into super serious stuff can we deconstruct the idea of "Patrol"? Because if the heroes whole plan is running/swinging around roof tops looking for petty crime to stop then they are wasting resources & time. Even if you take that kind of crime very seriously, the actual chances of running across it are extremely small.

On more serious levels there's the obvious glorification of violence and frequent dehumanization of criminals. Like withhow brutal Batman often is, slamming a muggers face into a wall so hard it creates a blood splatter or casualling torturing people for information.

Please no on start on "That's not the real Batman, mine befriends petty criminals" yeah yeah so does this version, sometimes, when the wind is right and the mood takes him. Brutality is as much a part of Batman's mythos as kindness or hope is and that's at best

Let alone the a recurring "This massive violation of morality, privacy, law is OK because its necessary" which has implications! Its not even that I'm strictly against exploring such ideas either, I'm not a pacifist or intrinsically against characters pushing the envelope when they feel its necessary but what that means, what comes of it, what that says about them matters.

Then there's stuff like, OK so your vigilante wants to tackle stuff like corruption and murder and so on? The police, the government, big corporate groups, all fit within their criteria, but fighting them puts your hero on the side that is breaking the law, How do they handle essentially becoming a rebel, how do they handle tackling a problem that doesn't have a neat easy "Toss-em in a cell" solution?

Hell, can we deconstruct what the prison industrial complex is in some countries, let alone how US-Centric stuff like this tends to be. Or how most super heroes actively collaborate with the police and what that tends to mean, or how they often exist in such a way that they seem to prop up the status quo.

Thematically this can make sense in a setting where the default is "Good" and villainous elements disrupt it, so the duty of those with power is to restore things. But that only works in fantasy, if you apply it to reality then heroes become a functional enabler of often very corrupt or abusive systems over a force to help.

Deconstructing super heroes doesn't even have to be about "Heroes bad actually". Plus you can interrogate what it means to actually slip the bonds of a normal and perceived safe existence. What drives a person to go to these extreme, what lets them operate like this, if they can at all. & if they can how does that work?

There's so much to deconstruct about heroes more interesting than "What if this one powerful guy who was good was evil this time?"

Why is it whenever people "deconstruct" superheroes it's never a criticism of any of the many things actually wrong with the genre? Like there's never any shots taken at the women in refrigerators thing or the total lack of meaningful stakes or the static characters or the bloated, convoluted clusterfuck storytelling or the desperate appealing exclusively to shitlord teenaged boys. Instead every single time it's just "get this... what if Superman were a baby killing rapist? IS YOUR MIND BLOWN YET?! It is so clever because normally he is not that."

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drug Offenses and Legal Strategies: A Comprehensive Guide for Criminal Lawyers

Drug crimes require a strategic and subtle approach from criminal lawyers, who steer a complex legal landscape to secure favorable client outcomes. This comprehensive guide delves into the intricacies of drug-related cases and explores unique legal strategies to empower a criminal lawyer in Florida in their defense efforts.

1. Deconstructing Drug Offenses:

Drug-related charges contain a range of crimes, ranging from possession to trafficking and driving under intoxication, each holding separate legal implications. A holistic interpretation of the charges and their potential consequences is the basis for crafting a robust defense strategy.

2. Constitutional Vigilance:

Unraveling the constitutional fabric of the case is paramount. A criminal lawyer meticulously examines search and seizure procedures, probing for any violations of the Fourth Amendment. Successfully questioning the legitimacy of proof compilation can greatly dilute the prosecution's case.

3. Chain of Custody Scrutiny:

A microscopic examination of the chain of custody is indispensable. Lawyers meticulously analyze evidence handling, searching for any irregularities that could doubt the seized materials' reliability. Any breaks in the chain can be strategically exploited in the defense.

4. Harnessing Expert Testimony:

Leveraging expert witnesses, such as forensic chemists or toxicologists, adds a powerful dimension to the defense. Their discernment of the nature and quantity of the substance can be key in introducing reasonable doubt. Expert testimony serves as a formidable tool in challenging the prosecution's evidence.

5. Intent and Knowledge Emphasis:

Interrogating the prosecution's ability to prove intent or knowledge is a strategic pivot. A top criminal lawyer dissects the evidence to determine if the client knowingly possessed or intended to distribute the controlled substance. Creating doubt on these pivotal elements can reshape the trajectory of the case.

6. Exploring Diversion Programs:

Innovative defense extends to advocating for diversion programs and alternative sentencing options like a family lawyer. By emphasizing rehabilitation over punitive measures, the legal experts seek avenues such as drug courts or rehabilitation programs, which are particularly advantageous for non-violent offenders scuffling with substance abuse issues.

7. Strategic Plea Negotiations:

The negotiation process is an art and takes center stage in drug offense cases. Criminal attorneys carefully evaluate the strengths and drawbacks of the case, leveraging this insight to secure favorable plea deals. Reduced charges, minimal sentencing, or count dismissals become apparent through adept negotiation. It is a similar approach that a family lawyer adopts.

8. Crafting Sentencing Mitigation:

A renowned criminal lawyer presents compelling mitigation factors as the case progresses to sentencing. Showcasing the client's guilt, positive societal contributions, or proof of rehabilitation efforts can convince the court's perspective during sentencing, potentially leading to more lenient or tolerant outcomes.

In conclusion, the defense of clients in drug offense cases requires a dynamic and creative approach. Armed with a deep understanding of legal nuances and a strategic mindset, criminal lawyers can navigate the challenges posed by drug-related charges. By weaving together constitutional scrutiny, expert insights, and innovative defense strategies, lawyers can forge a path to success in these intricate legal battles. SPB Law presents the best legal assistance and court representation in diverse criminal cases. The top legal firm is the ultimate destination to hire a reputed criminal and family lawyer in Florida.

0 notes

Note

1/2 i think the thing that makes it harder to engage with race in supernatural (at least for me, idk abt white fans) is that at the end of the day, the actors are white. the characters are white. the writers are white. there's no such thing as race-coding the way there is with gender or queerness. like, we talk about how supernatural accidentally gave us some (poor, but doesn't-matter-bc-it's-still-fun) queer rep and we can take that and deconstruct it and project/investigate the inherent

2/2 queerness that main(!) characters have and we can even speculate about [GUNSHOT] and we get something out of it! something good and fun! but engaging with race on supernatural.. like, what is there to get? examining the way poc are treated is just traumatic (again, at least for me), and thinking about people using it as tumblr brain food when it's actually emblematic of white supremacy narratives being upheld and /real/ actors of color constantly being sidelined just. does not sit right with me

i understand what ur coming from and i absolutely didnt mean to say that anybody especially not white fans should take the racism in supernatural lightly or use it as “brain food.” its absolutely a serious matter! but race is present in the text from premise to execution to audience and the fact is that valid readings of the text MUST include a reading of race, white supremacy, and eugenics. no, its not a fun topic to think about, and it’s one that maybe people are scared to address bc they’re worried abt being canceled or whatever, but the fact is that when you engage w deeply racist media such as supernatural you cant in good conscience say Well it bothers me to examine the presence of race in this story so i’m going to focus on analyzing aspects of the text that are more fun for me.

this DOES NOT MEAN that anybody (ESPECIALLY not white people) should take racism lightly. it doesn’t mean they should turn it into an abstract intellectual exercise. it definitely doesn’t mean that white people should feel that they have the same expertise in deconstructing characters and narratives of color as they do in deconstructing female or lgbt characters and narratives. what it DOES mean is that race MUST play a part in how you read the text. people who claim to engage with supernatural on a deeper level (and by that i mean people who regularly read/post meta or talk about “the secret good supernatural in our heads”) MUST ALSO engage with racism. it isn’t enough to say Yeah supernatural is racist but i’m still going to enjoy and consume and create transformative fan content that replicates the racism embedded in supernatural. christianity as the underpinning law of the supernatural universe, monsters as inherently Other and in need of extermination, the consistent sidelining and villainizing of characters of color, these are all things that people need to start interrogating, and interrogation of these things HAS to become a part of mainstream fan culture in the same way interrogation of, for example, dean’s relationship to masculinity and femininity/castiel’s relationship with gayness and authority and free will/sam’s relationship with monstrosity as a function of lgbt coding has become a part of mainstream fan culture.

because the fact is that That is what engaging critically with a racist text MEANS. it doesn’t mean acknowledging that it’s racist as lip service and then moving on. if race is not an active and ongoing part in fan discussion and analysis of the show, then fans are not engaging critically, they are just consuming and excusing a racist text. either you’re actively discussing and pushing against racism in supernatural, or you’re accepting it. and honestly if, for whatever reason, you aren’t comfortable with interrogating the element of race in supernatural and integrating it into your analysis of the show, you really should just not engage with supernatural.

#im concluding with the general you not pointed at the asker specifically#and this answer is a general answer bc this is something that ive been meaning to articulate and post#it's not aggressive towards you the asker at all im actually really glad you sent this because i HAVE noticed the response ur talking abt#as in white people saying things like yeah race in supernatural is a critical perspective on it that we can joke abt and take lightly just#like gender and sexuality perspectives#so thank you for asking#asks#this is okay to rb btw i actually want people to rb this

238 notes

·

View notes

Text

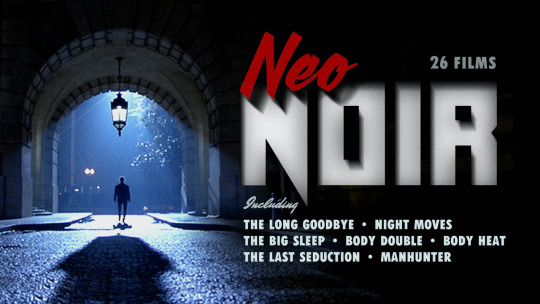

Thoughts on: Criterion's Neo-Noir Collection

I have written up all 26 films* in the Criterion Channel's Neo-Noir Collection.

Legend: rw - rewatch; a movie I had seen before going through the collection dnrw - did not rewatch; if a movie met two criteria (a. I had seen it within the last 18 months, b. I actively dislike it) I wrote it up from memory.

* in September, Brick leaves the Criterion Channel and is replaced in the collection with Michael Mann's Thief. May add it to the list when that happens.

Note: These are very "what was on my mind after watching." No effort has been made to avoid spoilers, nor to make the plot clear for anyone who hasn't seen the movies in question. Decide for yourself if that's interesting to you.

Cotton Comes to Harlem I feel utterly unequipped to asses this movie. This and Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song the following year are regularly cited as the progenitors of the blaxploitation genre. (This is arguably unfair, since both were made by Black men and dealt much more substantively with race than the white-directed films that followed them.) Its heroes are a couple of Black cops who are treated with suspicion both by their white colleagues and by the Black community they're meant to police. I'm not 100% clear on whether they're the good guys? I mean, I think they are. But the community's suspicion of them seems, I dunno... well-founded? They are working for The Man. And there's interesting discussion to the had there - is the the problem that the law is carried out by racists, or is the law itself racist? Can Black cops make anything better? But it feels like the film stacks the deck in Gravedigger and Coffin Ed's favor; the local Black church is run by a conman, the Back-to-Africa movement is, itself, a con, and the local Black Power movement is treated as an obstacle. Black cops really are the only force for justice here. Movie portrays Harlem itself as a warm, thriving, cultured community, but the people that make up that community are disloyal and easily fooled. Felt, to me, like the message was "just because they're cops doesn't mean they don't have Black soul," which, nowadays, we would call copaganda. But, then, do I know what I'm talking about? Do I know how much this played into or off of or against stereotypes from 1970? Was this a radical departure I don't have the context to appreciate? Is there substance I'm too white and too many decades removed to pick up on? Am I wildly overthinking this? I dunno. Seems like everyone involved was having a lot of fun, at least. That bit is contagious.

Across 110th Street And here's the other side of the "race film" equation. Another movie set in Harlem with a Black cop pulled between the police, the criminals, and the public, but this time the film is made by white people. I like it both more and less. Pro: this time the difficult position of Black cop who's treated with suspicion by both white cops and Black Harlemites is interrogated. Con: the Black cop has basically no personality other than "honest cop." Pro: the racism of the police force is explicit and systemic, as opposed to comically ineffectual. Con: the movie is shaped around a racist white cop who beats the shit out of Black people but slowly forms a bond with his Black partner. Pro: the Black criminal at the heart of the movie talks openly about how the white world has stacked the deck against him, and he's soulful and relateable. Con: so of course he dies in the end, because the only way privileged people know to sympathetize with minorities is to make them tragic (see also: The Boys in the Band, Philadelphia, and Brokeback Mountain for gay men). Additional con: this time Harlem is portrayed as a hellhole. Barely any of the community is even seen. At least the shot at the end, where the criminal realizes he's going to die and throws the bag of money off a roof and into a playground so the Black kids can pick it up before the cops reclaim it was powerful. But overall... yech. Cotton Comes to Harlem felt like it wasn't for me; this feels like it was 100% for me and I respect it less for that.

The Long Goodbye (rw) The shaggiest dog. Like much Altman, more compelling than good, but very compelling. Raymond Chandler's story is now set in the 1970's, but Philip Marlowe is the same Philip Marlowe of the 1930's. I get the sense there was always something inherently sad about Marlowe. Classic noir always portrayed its detectives as strong-willed men living on the border between the straightlaced world and its seedy underbelly, crossing back and forth freely but belonging to neither. But Chandler stresses the loneliness of it - or, at least, the people who've adapted Chandler do. Marlowe is a decent man in an indecent world, sorting things out, refusing to profit from misery, but unable to set anything truly right. Being a man out of step is here literalized by putting him forty years from the era where he belongs. His hardboiled internal monologue is now the incessant mutterings of the weird guy across the street who never stops smoking. Like I said: compelling! Kael's observation was spot on: everyone in the movie knows more about the mystery than he does, but he's the only one who cares. The mystery is pretty threadbare - Marlowe doesn't detect so much as end up in places and have people explain things to him. But I've seen it two or three times now, and it does linger.

Chinatown (rw) I confess I've always been impressed by Chinatown more than I've liked it. Its story structure is impeccable, its atmosphere is gorgeous, its noirish fatalism is raw and real, its deconstruction of the noir hero is well-observed, and it's full of clever detective tricks (the pocket watches, the tail light, the ruler). I've just never connected with it. Maybe it's a little too perfectly crafted. (I feel similar about Miller's Crossing.) And I've always been ambivalent about the ending. In Towne's original ending, Evelyn shoots Noah Cross dead and get arrested, and neither she nor Jake can tell the truth of why she did it, so she goes to jail for murder and her daughter is in the wind. Polansky proposed the ending that exists now, where Evelyn just dies, Cross wins, and Jake walks away devastated. It communicates the same thing: Jake's attempt to get smart and play all the sides off each other instead of just helping Evelyn escape blows up in his face at the expense of the woman he cares about and any sense of real justice. And it does this more dramatically and efficiently than Towne's original ending. But it also treats Evelyn as narratively disposable, and hands the daughter over to the man who raped Evelyn and murdered her husband. It makes the women suffer more to punch up the ending. But can I honestly say that Towne's ending is the better one? It is thematically equal, dramatically inferior, but would distract me less. Not sure what the calculus comes out to there. Maybe there should be a third option. Anyway! A perfect little contraption. Belongs under a glass dome.

Night Moves (rw) Ah yeah, the good shit. This is my quintessential 70's noir. This is three movies in a row about detectives. Thing is, the classic era wasn't as chockablock with hardboiled detectives as we think; most of those movies starred criminals, cops, and boring dudes seduced to the darkness by a pair of legs. Gumshoes just left the strongest impressions. (The genre is said to begin with Maltese Falcon and end with Touch of Evil, after all.) So when the post-Code 70's decided to pick the genre back up while picking it apart, it makes sense that they went for the 'tecs first. The Long Goodbye dragged the 30's detective into the 70's, and Chinatown went back to the 30's with a 70's sensibility. But Night Moves was about detecting in the Watergate era, and how that changed the archetype. Harry Moseby is the detective so obsessed with finding the truth that he might just ruin his life looking for it, like the straight story will somehow fix everything that's broken, like it'll bring back a murdered teenager and repair his marriage and give him a reason to forgive the woman who fucked him just to distract him from some smuggling. When he's got time to kill, he takes out a little, magnetic chess set and recreates a famous old game, where three knight moves (get it?) would have led to a beautiful checkmate had the player just seen it. He keeps going, self-destructing, because he can't stand the idea that the perfect move is there if he can just find it. And, no matter how much we see it destroy him, we, the audience, want him to keep going; we expect a satisfying resolution to the mystery. That's what we need from a detective picture; one character flat-out compares Harry to Sam Spade. But what if the truth is just... Watergate? Just some prick ruining things for selfish reasons? Nothing grand, nothing satisfying. Nothing could be more noir, or more neo-, than that.

Farewell, My Lovely Sometimes the only thing that makes a noir neo- is that it's in color and all the blood, tits, and racism from the books they're based on get put back in. This second stab at Chandler is competant but not much more than that. Mitchum works as Philip Marlowe, but Chandler's dialogue feels off here, like lines that worked on the page don't work aloud, even though they did when Bogie said them. I'll chalk it up to workmanlike but uninspired direction. (Dang this looks bland so soon after Chinatown.) Moose Malloy is a great character, and perfectly cast. (Wasn't sure at first, but it's true.) Some other interesting cats show up and vanish - the tough brothel madam based on Brenda Allen comes to mind, though she's treated with oddly more disdain than most of the other hoods and is dispatched quicker. In general, the more overt racism and misogyny doesn't seem to do anything except make the movie "edgier" than earlier attempts at the same material, and it reads kinda try-hard. But it mostly holds together. *shrug*

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (dnrw) Didn't care for this at all. Can't tell if the script was treated as a jumping-off point or if the dialogue is 100% improvised, but it just drags on forever and is never that interesting. Keeps treating us to scenes from the strip club like they're the opera scenes in Amadeus, and, whatever, I don't expect burlesque to be Mozart, but Cosmo keeps saying they're an artful, classy joint, and I keep waiting for the show to be more than cheap, lazy camp. How do you make gratuitious nudity boring? Mind you, none of this is bad as a rule - I love digressions and can enjoy good sleaze, and it's clear the filmmakers care about what they're making. They just did not sell it in a way I wanted to buy. Can't remember what edit I watched; I hope it was the 135 minute one, because I cannot imagine there being a longer edit out there.

The American Friend (dnrw) It's weird that this is Patricia Highsmith, right? That Dennis Hopper is playing Tom Ripley? In a cowboy hat? I gather that Minghella's version wasn't true to the source, but I do love that movie, and this is a long, long way from that. This Mr. Ripley isn't even particularly talented! Anyway, this has one really great sequence, where a regular guy has been coerced by crooks into murdering someone on a train platform, and, when the moment comes to shoot, he doesn't. And what follows is a prolonged sequence of an amateur trying to surreptitiously tail a guy across a train station and onto another train, and all the while you're not sure... is he going to do it? is he going to chicken out? is he going to do it so badly he gets caught? It's hard not to put yourself in the protagonist's shoes, wondering how you would handle the situation, whether you could do it, whether you could act on impulse before your conscience could catch up with you. It drags on a long while and this time it's a good thing. Didn't much like the rest of the movie, it's shapeless and often kind of corny, and the central plot hook is contrived. (It's also very weird that this is the only Wim Wenders I've seen.) But, hey, I got one excellent sequence, not gonna complain.

The Big Sleep Unlike the 1946 film, I can follow the plot of this Big Sleep. But, also unlike the 1946 version, this one isn't any damn fun. Mitchum is back as Marlowe (this is three Marlowes in five years, btw), and this time it's set in the 70's and in England, for some reason. I don't find this offensive, but neither do I see what it accomplishes? Most of the cast is still American. (Hi Jimmy!) Still holds together, but even less well than Farewell, My Lovely. But I do find it interesting that the neo-noir era keeps returning to Chandler while it's pretty much left Hammet behind (inasmuch as someone whose genes are spread wide through the whole genre can be left behind). Spade and the Continental Op, straightshooting tough guys who come out on top in the end, seem antiquated in the (post-)modern era. But Marlowe's goodness being out of sync with the world around him only seems more poignant the further you take him from his own time. Nowadays you can really only do Hammett as pastiche, but I sense that you could still play Chandler straight.

Eyes of Laura Mars The most De Palma movie I've seen not made by De Palma, complete with POV shots, paranormal hoodoo, and fixation with sex, death, and whether images of such are art or exploitation (or both). Laura Mars takes photographs of naked women in violent tableux, and has gotten quite famous doing so, but is it damaging to women? The movie has more than a superficial engagement with this topic, but only slightly more than superficial. Kept imagining a movie that is about 30% less serial killer story and 30% more art conversations. (But, then, I have an art degree and have never murdered anyone, so.) Like, museums are full of Biblical paintings full of nude women and slaughter, sometimes both at once, and they're called masterpieces. Most all of them were painted by men on commission from other men. Now Laura Mars makes similar images in modern trappings, and has models made of flesh and blood rather than paint, and it's scandalous? Why is it only controversial once women are getting paid for it? On the other hand, is this just the master's tools? Is she subverting or challenging the male gaze, or just profiting off of it? Or is a woman profiting off of it, itself, a subversion? Is it subversive enough to account for how it commodifies female bodies? These questions are pretty clearly relevant to the movie itself, and the movies in general, especially after the fall of the Hays Code when people were really unrestrained with the blood and boobies. And, heck, the lead is played by the star of Bonnie and Clyde! All this is to say: I wish the movie were as interested in these questions as I am. What's there is a mildly diverting B-picture. There's one great bit where Laura's seeing through the killer's eyes (that's the hook, she gets visions from the murderer's POV; no, this is never explained) and he's RIGHT BEHIND HER, so there's a chase where she charges across an empty room only able to see her own fleeing self from ten feet behind. That was pretty great! And her first kiss with the detective (because you could see a mile away that the detective and the woman he's supposed to protect are gonna fall in love) is immediately followed by the two freaking out about how nonsensical it is for them to fall in love with each other, because she's literally mourning multiple deaths and he's being wildly unprofessional, and then they go back to making out. That bit was great, too. The rest... enh.

The Onion Field What starts off as a seemingly not-that-noirish cops-vs-crooks procedural turns into an agonizingly protracted look at the legal system, with the ultimate argument that the very idea of the law ever resulting in justice is a lie. Hoo! I have to say, I'm impressed. There's a scene where a lawyer - whom I'm not sure is even named, he's like the seventh of thirteen we've met - literally quits the law over how long this court case about two guys shooting a cop has taken. He says the cop who was murdered has been forgotten, his partner has never gotten to move on because the case has lasted eight years, nothing has been accomplished, and they should let the two criminals walk and jail all the judges and lawyers instead. It's awesome! The script is loaded with digressions and unnecessary details, just the way I like it. Can't say I'm impressed with the execution. Nothing is wrong, exactly, but the performances all seem a tad melodramatic or a tad uninspired. Camerawork is, again, purely functional. It's no masterpiece. But that second half worked for me. (And it's Ted Danson's first movie! He did great.)

Body Heat (rw) Let's say up front that this is a handsomely-made movie. Probably the best looking thing on the list since Night Moves. Nothing I've seen better captures the swelter of an East Coast heatwave, or the lusty feeling of being too hot to bang and going at it regardless. Kathleen Turner sells the hell out of a femme fatale. There are a lot of good lines and good performances (Ted Danson is back and having the time of his life). I want to get all that out of the way, because this is a movie heavily modeled after Double Indemnity, and I wanted to discuss its merits before I get into why inviting that comparison doesn't help the movie out. In a lot of ways, it's the same rules as the Robert Mitchum Marlowe movies - do Double Indemnity but amp up the sex and violence. And, to a degree it works. (At least, the sex does, dunno that Double Indemnity was crying out for explosions.) But the plot is amped as well, and gets downright silly. Yeah, Mrs. Dietrichson seduces Walter Neff so he'll off her husband, but Neff clocks that pretty early and goes along with it anyway. Everything beyond that is two people keeping too big a secret and slowly turning on each other. But here? For the twists to work Matty has to be, from frame one, playing four-dimensional chess on the order of Senator Palpatine, and its about as plausible. (Exactly how did she know, after she rebuffed Ned, he would figure out her local bar and go looking for her at the exact hour she was there?) It's already kind of weird to be using the spider woman trope in 1981, but to make her MORE sexually conniving and mercenary than she was in the 40's is... not great. As lurid trash, it's pretty fun for a while, but some noir stuff can't just be updated, it needs to be subverted or it doesn't justify its existence.

Blow Out Brian De Palma has two categories of movie: he's got his mainstream, director-for-hire fare, where his voice is either reigned in or indulged in isolated sequences that don't always jive with the rest fo the film, and then there's his Brian De Palma movies. My mistake, it seems, is having seen several for-hires from throughout his career - The Untouchables (fine enough), Carlito's Way (ditto, but less), Mission: Impossible (enh) - but had only seen De Palma-ass movies from his late period (Femme Fatale and The Black Dahlia, both of which I think are garbage). All this to say: Blow Out was my first classic-era De Palma, and holy fucking shit dudes. This was (with caveats) my absolute and entire jam. I said I could enjoy good sleaze, and this is good friggin' sleaze. (Though far short of De Palma at his sleaziest, mercifully.) The splitscreens, the diopter shots, the canted angles, how does he make so many shlocky things work?! John Travolta's sound tech goes out to get fresh wind fx for the movie he's working on, and we get this wonderful sequence of visuals following sounds as he turns his attention and his microphone to various noises - a couple on a walk, a frog, an owl, a buzzing street lamp. Later, as he listens back to the footage, the same sequence plays again, but this time from his POV; we're seeing his memory as guided by the same sequence of sounds, now recreated with different shots, as he moves his pencil in the air mimicking the microphone. When he mixes and edits sounds, we hear the literal soundtrack of the movie we are watching get mixed and edited by the person on screen. And as he tries to unravel a murder mystery, he uses what's at hand: magnetic tape, flatbed editors, an animation camera to turn still photos from the crime scene into a film and sync it with the audio he recorded; it's forensics using only the tools of the editing room. As someone who's spent some time in college editing rooms, this is a hoot and a half. Loses a bit of steam as it goes on and the film nerd stuff gives way to a more traditional thriller, but rallies for a sound-tech-centered final setpiece, which steadily builds to such madcap heights you can feel the air thinning, before oddly cutting its own tension and then trying to build it back up again. It doesn't work as well the second time. But then, that shot right after the climax? Damn. Conflicted on how the movie treats the female lead. I get why feminist film theorists are so divided on De Palma. His stuff is full of things feminists (rightly) criticize, full of women getting naked when they're not getting stabbed, but he also clearly finds women fascinating and has them do empowered and unexpected things, and there are many feminist reads of his movies. Call it a mixed bag. But even when he's doing tropey shit, he explores the tropes in unexpected ways. Definitely the best movie so far that I hadn't already seen.

Cutter's Way (rw) Alex Cutter is pitched to us as an obnoxious-but-sympathetic son of a bitch, and, you know, two out of three ain't bad. Watched this during my 2020 neo-noir kick and considered skipping it this time because I really didn't enjoy it. Found it a little more compelling this go around, while being reminded of why my feelings were room temp before. Thematically, I'm onboard: it's about a guy, Cutter, getting it in his head that he's found a murderer and needs to bring him to justice, and his friend, Bone, who intermittently helps him because he feels bad that Cutter lost his arm, leg, and eye in Nam and he also feels guilty for being in love with Cutter's wife. The question of whether the guy they're trying to bring down actually did it is intentionally undefined, and arguably unimportant; they've got personal reasons to see this through. Postmodern and noirish, fixated with the inability to ever fully know the truth of anything, but starring people so broken by society that they're desperate for certainty. (Pretty obvious parallels to Vietnam.) Cutter's a drunk and kind of an asshole, but understandably so. Bone's shiftlessness is the other response to a lack of meaning in the world, to the point where making a decision, any decision, feels like character growth, even if it's maybe killing a guy whose guilt is entirely theoretical. So, yeah, I'm down with all of this! A- in outline form. It's just that Cutter is so uninterestingly unpleasant and no one else on screen is compelling enough to make up for it. His drunken windups are tedious and his sanctimonious speeches about what the war was like are, well, true and accurate but also obviously manipulative. It's two hours with two miserable people, and I think Cutter's constant chatter is supposed to be the comic relief but it's a little too accurate to drunken rambling, which isn't funny if you're not also drunk. He's just tedious, irritating, and periodically racist. Pass.

Blood Simple (rw) I'm pretty cool on the Coens - there are things I've liked, even loved, in every Coen film I've seen, but I always come away dissatisfied. For a while, I kept going to their movies because I was sure eventually I'd love one without qualification. No Country for Old Men came close, the first two acts being master classes in sustained tension. But then the third act is all about denying closure: the protagonist is murdered offscreen, the villain's motives are never explained, and it ends with an existentialist speech about the unfathomable cruelty of the world. And it just doesn't land for me. The archness of the Coen's dialogue, the fussiness of their set design, the kinda-intimate, kinda-awkward, kinda-funny closeness of the camera's singles, it cannot sell me on a devastating meditation about meaninglessness. It's only ever sold me on the Coens' own cleverness. And that archness, that distancing, has typified every one of their movies I've come close to loving. Which is a long-ass preamble to saying, holy heck, I was not prepared for their very first movie to be the one I'd been looking for! I watched it last year and it remains true on rewatch: Blood Simple works like gangbusters. It's kind of Double Indemnity (again) but played as a comedy of errors, minus the comedy: two people romantically involved feeling their trust unravel after a murder. And I think the first thing that works for me is that utter lack of comedy. It's loaded with the Coens' trademark ironies - mostly dramatic in this case - but it's all played straight. Unlike the usual lead/femme fatale relationship, where distrust brews as the movie goes on, the audience knows the two main characters can trust each other. There are no secret duplicitous motives waiting to be revealed. The audience also know why they don't trust each other. (And it's all communicated wordlessly, btw: a character enters a scene and we know, based on the information that character has, how it looks to them and what suspicions it would arouse, even as we know the truth of it). The second thing that works is, weirdly, that the characters aren't very interesting?! Ray and Abby have almost no characterization. Outside of a general likability, they are blank slates. This is a weakness in most films, but, given the agonizingly long, wordless sequences where they dispose of bodies or hide from gunfire, you're left thinking not "what will Ray/Abby do in this scenario," because Ray and Abby are relatively elemental and undefined, but "what would I do in this scenario?" Which creates an exquisite tension but also, weirdly, creates more empathy than I feel for the Coens' usual cast of personalities. It's supposed to work the other way around! Truly enjoyable throughout but absolutely wonderful in the suspenseful-as-hell climax. Good shit right here.

Body Double The thing about erotic thrillers is everything that matters is in the name. Is it thrilling? Is it erotic? Good; all else is secondary. De Palma set out to make the most lurid, voyeuristic, horny, violent, shocking, steamy movie he could come up with, and its success was not strictly dependent on the lead's acting ability or the verisimilitude of the plot. But what are we, the modern audience, to make of it once 37 years have passed and, by today's standards, the eroticism is quite tame and the twists are no longer shocking? Then we're left with a nonsensical riff on Vertigo, a specularization of women that is very hard to justify, and lead actor made of pulped wood. De Palma's obsessions don't cohere into anything more this time; the bits stolen from Hitchcock aren't repurposed to new ends, it really is just Hitch with more tits and less brains. (I mean, I still haven't seen Vertigo, but I feel 100% confident in that statement.) The diopter shots and rear-projections this time look cheap (literally so, apparently; this had 1/3 the budget of Blow Out). There are some mildly interesting setpieces, but nothing compared to Travolta's auditory reconstructions or car chase where he tries to tail a subway train from street level even if it means driving through a frickin parade like an inverted French Connection, goddamn Blow Out was a good movie! Anyway. Melanie Griffith seems to be having fun, at least. I guess I had a little as well, but it was, at best, diverting, and a real letdown.

The Hit Surprised by how much I enjoyed this one. Terrance Stamp flips on the mob and spends ten years living a life of ease in Spain, waiting for the day they find and kill him. Movie kicks off when they do find him, and what follows is a ramshackle road movie as John Hurt and a young Tim Roth attempt to drive him to Paris so they can shoot him in front of his old boss. Stamp is magnetic. He's spent a decade reading philosophy and seems utterly prepared for death, so he spends the trip humming, philosophizing, and being friendly with his captors when he's not winding them up. It remains unclear to the end whether the discord he sews between Roth and Hurt is part of some larger plan of escape or just for shits and giggles. There's also a decent amount of plot for a movie that's not terribly plot-driven - just about every part of the kidnapping has tiny hitches the kidnappers aren't prepared for, and each has film-long repercussions, drawing the cops closer and somehow sticking Laura del Sol in their backseat. The ongoing questions are when Stamp will die, whether del Sol will die, and whether Roth will be able to pull the trigger. In the end, it's actually a meditation on ethics and mortality, but in a quiet and often funny way. It's not going to go down as one of my new favs, but it was a nice way to spend a couple hours.

Trouble in Mind (dnrw) I fucking hated this movie. It's been many months since I watched it, do I remember what I hated most? Was it the bit where a couple of country bumpkins who've come to the city walk into a diner and Mr. Bumpkin clocks that the one Black guy in the back as obviously a criminal despite never having seen him before? Was it the part where Kris Kristofferson won't stop hounding Mrs. Bumpkin no matter how many times she demands to be left alone, and it's played as romantic because obviously he knows what she needs better than she does? Or is it the part where Mr. Bumpkin reluctantly takes a job from the Obvious Criminal (who is, in fact, a criminal, and the only named Black character in the movie if I remember correctly, draw your own conclusions) and, within a week, has become a full-blown hood, which is exemplified by a lot, like, a lot of queer-coding? The answer to all three questions is yes. It's also fucking boring. Even out-of-drag Divine's performance as the villain can't save it.

Manhunter 'sfine? I've still never seen Silence of the Lambs, nor any of the Hopkins Lecter movies, nor, indeed, any full episode of the show. So the unheimlich others get seeing Brian Cox play Hannibal didn't come into play. Cox does a good job with him, but he's barely there. Shame, cuz he's the most interesting part of the movie. Honestly, there's a lot of interesting stuff that's barely there. Will Graham being a guy who gets into the heads of serial killers is explored well enough, and Mann knows how to direct a police procedural such that it's both contemplative and propulsive. But all the other themes it points at? Will's fear that he understands murderers a little too well? Hannibal trying to nudge him towards becoming one? Whatever dance Hannibal and Tooth Fairy are doing? What Tooth Fairy's deal is, anyway? (Why does he wear fake teeth and bite things? Why is he fixated on the red dragon? Does the bit where he says "Francis is gone forever" mean he has DID?) None of it goes anywhere or amounts to anything. I mean, it's certainly more interesting with this stuff than without, but it has that feel of a book that's been pared of its interesting bits to fit the runtime (or, alternately, pulp that's been sloppily elevated). I still haven't made my mind up on Mann's cold, precise camera work, but at least it gives me something to look at. It's fine! This is fine.

Mona Lisa (rw) Gave this one another shot. Bob Hoskins is wonderful as a hood out of his depth in classy places, quick to anger but just as quick to let anger go (the opening sequence where he's screaming on his ex-wife's doorstep, hurling trash cans at her house, and one minute later thrilled to see his old car, is pretty nice). And Cathy Tyson's working girl is a subtler kind of fascinating, exuding a mixture of coldness and kindness. It's just... this is ultimately a story about how heartbreaking it is when the girl you like is gay, right? It's Weezer's Pink Triangle: The Movie. It's not homophobic, exactly - Simone isn't demonized for being a lesbian - but it's still, like, "man, this straight white guy's pain is so much more interesting than the Black queer sex worker's." And when he's yelling "you woulda done it!" at the end, I can't tell if we're supposed to agree with him. Seems pretty clear that she wouldn'ta done it, at least not without there being some reveal about her character that doesn't happen, but I don't think the ending works if we don't agree with him, so... I'm like 70% sure the movie does Simone dirty there. For the first half, their growing relationship feels genuine and natural, and, honestly, the story being about a real bond that unfortunately means different things to each party could work if it didn't end with a gun and a sock in the jaw. Shape feels jagged as well; what feels like the end of the second act or so turns out to be the climax. And some of the symbolism is... well, ok, Simone gives George money to buy more appropriate clothes for hanging out in high end hotels, and he gets a tan leather jacket and a Hawaiian shirt, and their first proper bonding moment is when she takes him out for actual clothes. For the rest of the movie he is rocking double-breasted suits (not sure I agree with the striped tie, but it was the eighties, whaddya gonna do?). Then, in the second half, she sends him off looking for her old streetwalker friend, and now he looks completely out of place in the strip clubs and bordellos. So far so good. But then they have this run-in where her old pimp pulls a knife and cuts George's arm, so, with his nice shirt torn and it not safe going home (I guess?) he starts wearing the Hawaiian shirt again. So around the time he's starting to realize he doesn't really belong in Simone's world or the lowlife world he came from anymore, he's running around with the classy double-breasted suit jacket over the garish Hawaiian shirt, and, yeah, bit on the nose guys. Anyway, it has good bits, I just feel like a movie that asks me to feel for the guy punching a gay, Black woman in the face needs to work harder to earn it. Bit of wasted talent.

The Bedroom Window Starts well. Man starts an affair with his boss' wife, their first night together she witnesses an attempted murder from his window, she worries going to the police will reveal the affair to her husband, so the man reports her testimony to the cops claiming he's the one who saw it. Young Isabelle Huppert is the perfect woman for a guy to risk his career on a crush over, and Young Steve Guttenberg is the perfect balance of affability and amorality. And it flows great - picks just the right media to res. So then he's talking to the cops, telling them what she told him, and they ask questions he forgot to ask her - was the perp's jacket a blazer or a windbreaker? - and he has to guess. Then he gets called into the police lineup, and one guy matches her description really well, but is it just because he's wearing his red hair the way she described it? He can't be sure, doesn't finger any of them. He finds out the cops were pretty certain about one of the guys, so he follows the one he thinks it was around, looking for more evidence, and another girl is attacked right outside a bar he knows the redhead was at. Now he's certain! But he shows the boss' wife the guy and she's not certain, and she reminds him they don't even know if the guy he followed is the same guy the police suspected! And as he feeds more evidence to the cops, he has to lie more, because he can't exactly say he was tailing the guy around the city. So, I'm all in now. Maybe it's because I'd so recently rewatched Night Moves and Cutter's Way, but this seems like another story about uncertainty. He's really certain about the guy because it fits narratively, and we, the audience, feel the same. But he's not actually a witness, he doesn't have actual evidence, he's fitting bits and pieces together like a conspiracy theorist. He's fixating on what he wants to be true. Sign me up! But then it turns out he's 100% correct about who the killer is but his lies are found out and now the cops think he's the killer and I realize, oh, no, this movie isn't nearly as smart as I thought it was. Egg on my face! What transpires for the remaining half of the runtime is goofy as hell, and someone with shlockier sensibilities could have made a meal of it, but Hanson, despite being a Corman protege, takes this silliness seriously in the all wrong ways. Next!

Homicide (rw? I think I saw most of this on TV one time) Homicide centers around the conflicted loyalties of a Jewish cop. It opens with the Jewish cop and his white gentile partner taking over a case with a Black perp from some Black FBI agents. The media is making a big thing about the racial implications of the mostly white cops chasing down a Black man in a Black neighborhood. And inside of 15 minutes the FBI agent is calling the lead a k*ke and the gentile cop is calling the FBI agent a f****t and there's all kinds of invective for Black people. The film is announcing its intentions out the gate: this movie is about race. But the issue here is David Mamet doesn't care about race as anything other than a dramatic device. He's the Ubisoft of filmmakers, having no coherent perspective on social issues but expecting accolades for even bringing them up. Mamet is Jewish (though lead actor Joe Mantegna definitely is not) but what is his position on the Jewish diaspora? The whole deal is Mantegna gets stuck with a petty homicide case instead of the big one they just pinched from the Feds, where a Jewish candy shop owner gets shot in what looks like a stickup. Her family tries to appeal to his Jewishness to get him to take the case seriously, and, after giving them the brush-off for a long time, finally starts following through out of guilt, finding bits and pieces of what may or may not be a conspiracy, with Zionist gun runners and underground neo-Nazis. But, again: all of these are just dramatic devices. Mantegna's Jewishness (those words will never not sound ridiculous together) has always been a liability for him as a cop (we are told, not shown), and taking the case seriously is a reclamation of identity. The Jews he finds community with sold tommyguns to revolutionaries during the founding of Israel. These Jews end up blackmailing him to get a document from the evidence room. So: what is the film's position on placing stock in one's Jewish identity? What is its position on Israel? What is its opinion on Palestine? Because all three come up! And the answer is: Mamet doesn't care. You can read it a lot of different ways. Someone with more context and more patience than me could probably deduce what the de facto message is, the way Chris Franklin deduced the de facto message of Far Cry V despite the game's efforts not to have one, but I'm not going to. Mantegna's attempt to reconnect with his Jewishness gets his partner killed, gets the guy he was supposed to bring in alive shot dead, gets him possibly permanent injuries, gets him on camera blowing up a store that's a front for white nationalists, and all for nothing because the "clues" he found (pretty much exclusively by coincidence) were unconnected nothings. The problem is either his Jewishness, or his lifelong failure to connect with his Jewishness until late in life. Mamet doesn't give a shit. (Like, Mamet canonically doesn't give a shit: he is on record saying social context is meaningless, characters only exist to serve the plot, and there are no deeper meanings in fiction.) Mamet's ping-pong dialogue is fun, as always, and there are some neat ideas and characters, but it's all in service of a big nothing that needed to be a something to work.

Swoon So much I could talk about, let's keep it to the most interesting bits. Hommes Fatales: a thing about classic noir that it was fascinated by the marginal but had to keep it in the margins. Liberated women, queer-coded killers, Black jazz players, broke thieves; they were the main event, they were what audiences wanted to see, they were what made the movies fun. But the ending always had to reassert straightlaced straight, white, middle-class male society as unshakeable. White supremacist capitalist patriarchy demanded, both ideologically and via the Hays Code, that anyone outside these norms be punished, reformed, or dead by the movie's end. The only way to make them the heroes was to play their deaths for tragedy. It is unsurprising that neo-noir would take the queer-coded villains and make them the protagonists. Implicature: This is the story of Leopold and Loeb, murderers famous for being queer, and what's interesting is how the queerness in the first half exists entirely outside of language. Like, it's kind of amazing for a movie from 1992 to be this gay - we watch Nathan and Dickie kiss, undress, masturbate, fuck; hell, they wear wedding rings when they're alone together. But it's never verbalized. Sex is referred to as "your reward" or "what you wanted" or "best time." Dickie says he's going to have "the girls over," and it turns out "the girls" are a bunch of drag queens, but this is never acknowledged. Nathan at one point lists off a bunch of famous men - Oscar Wild, E.M. Forster, Frederick the Great - but, though the commonality between them is obvious (they were all gay), it's left the the audience to recognize it. When their queerness is finally verbalized in the second half, it's first in the language of pathology - a psychiatrist describing their "perversions" and "misuse" of their "organs" before the court, which has to be cleared of women because it's so inappropriate - and then with slurs from the man who murders Dickie in jail (a murder which is written off with no investigation because the victim is a gay prisoner instead of a L&L's victim, a child of a wealthy family). I don't know if I'd have noticed this if I hadn't read Chip Delany describing his experience as a gay man in the 50's existing almost entirely outside of language, the only language at the time being that of heteronormativity. Murder as Love Story: L&L exchange sex as payment for the other commiting crimes; it's foreplay. Their statements to the police where they disagree over who's to blame is a lover's quarrel. Their sentencing is a marriage. Nathan performs his own funeral rites over Dickie's body after he dies on the operating table. They are, in their way, together til death did they part. This is the relationship they can have. That it does all this without romanticizing the murder itself or valorizing L&L as humans is frankly incredible.

Suture (rw) The pitch: at the funeral for his father, wealthy Vincent Towers meets his long lost half brother Clay Arlington. It is implied Clay is a child from out of wedlock, possibly an affair; no one knows Vincent has a half-brother but him and Clay. Vincent invites Clay out to his fancy-ass home in Arizona. Thing is, Vincent is suspected (correctly) by the police of having murdered his father, and, due to a striking family resemblence, he's brought Clay to his home to fake his own death. He finagles Clay into wearing his clothes and driving his car, and then blows the car up and flees the state, leaving the cops to think him dead. Thing is, Clay survives, but with amnesia. The doctors tell him he's Vincent, and he has no reason to disagree. Any discrepancy in the way he looks is dismissed as the result of reconstructive surgery after the explosion. So Clay Arlington resumes Vincent Towers' life, without knowing Clay Arlington even exists. The twist: Clay and Vincent are both white, but Vincent is played by Michael Harris, a white actor, and Clay is played by Dennis Haysbert, a Black actor. "Ian, if there's just the two of them, how do you know it's not Harris playing a Black character?" Glad you asked! It is most explicitly obvious during a scene where Vincent/Clay's surgeon-cum-girlfriend essentially bringing up phrenology to explain how Vincent/Clay couldn't possibly have murdered his father, describing straight hair, thin lips, and a Greco-Roman nose Haysbert very clearly doesn't have. But, let's be honest: we knew well beforehand that the rich-as-fuck asshole living in a huge, modern house and living it up in Arizona high society was white. Though Clay is, canonically, white, he lives an poor and underprivileged life common to Black men in America. Though the film's title officially refers to the many stitches holding Vincent/Clay's face together after the accident, "suture" is a film theory term, referring to the way a film audience gets wrapped up - sutured - in the world of the movie, choosing to forget the outside world and pretend the story is real. The usage is ironic, because the audience cannot be sutured in; we cannot, and are not expected to, suspend our disbelief that Clay is white. We are deliberately distanced. Consequently this is a movie to be thought about, not to to be felt. It has the shape of a Hitchcockian thriller but it can't evoke the emotions of one. You can see the scaffolding - "ah, yes, this is the part of a thriller where one man hides while another stalks him with a gun, clever." I feel ill-suited to comment on what the filmmakers are saying about race. I could venture a guess about the ending, where the psychiatrist, the only one who knows the truth about Clay, says he can never truly be happy living the lie of being Vincent Towers, while we see photographs of Clay/Vincent seemingly living an extremely happy life: society says white men simply belong at the top more than Black men do, but, if the roles could be reversed, the latter would slot in seamlessly. Maybe??? Of all the movies in this collection, this is the one I'd most want to read an essay on (followed by Swoon).

The Last Seduction (dnrw) No, no, no, I am not rewataching this piece of shit movie.