#d'aulnoy fairytales

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Names in fairytales: Prince Charming

Prince Charming has become the iconic, “canon” name of the stock character of the brave, handsome prince who delivers the princess and marries her at the end of every tale.

But... where does this name comes from? You can’t find it in any of Perrault’s tales, nor in any of the Grimms’, nor in Andersen - in none of the big, famous fairytales of today. Sure, princes are often described as “charming”, as an adjective in those tales, but is it enough to suddenly create a stock name on its own?

No, of course it is not. The name “Prince Charming” has a history, and it comes, as many things in fairy tales, from the French literary fairytales. But not from Perrault, no, Perrault kept his princes unnamed: it comes from madame d’Aulnoy.

You see, madame d’Aulnoy, due to literaly helping create the fairytale genre in French literature, created a trend that would be followed by all after her: unlike Perrault who kept a lot of his characters unnamed, madame d’Aulnoy named almost each and every of her characters. But she didn’t just randomly name them: she named them after significant words. Either they were given actual words and adjectives as name, such as “Duchess Grumpy”, “Princess Shining”, “Princess Graceful”, “Prince Angry”, “King Cute”, “Prince Small-Sun”, etc etc... Either they were given names with a hidden meaning in them (such as “Carabosse”, the name of a wicked fairy which is actually a pun on Greek words, or “Galifron”, the name of a giant which also contains puns of old French verbs). So she started this all habit of having fairytale characters named after specific qualities, flaws or traits - and among her characters you find, in the fairytale “L’oiseau bleu”, “The blue bird”, “King Charming” (Roi Charmant). Not prince, here king, though he still acts as a typical prince charming would act - and “Charming” is indeed his name.

And this character of “King Charming” actually went on to create the name we know today as “Prince Charming”. It should be noted that, while a lot of d’Aulnoy’s fairytales ended up forgotten by popular culture, some of her stories stayed MASSIVELY famous throughout the centuries and reached almost ever-lasting fame in countries other than France: The doe in the woods, The white cat, Cunning Cinders... and the Blue Bird, which stays probably the most famous fairytale of madame d’Aulnoy ever. It even was included in Andrew Lang’s Green Fairy Book.

And speaking of Andrew Lang, he is actually the next step in the history of “Prince Charming”. He translated another fairytale of madame d’Aulnoy prior to Blue Bird. In Lang’s “Blue Fairy Book”, you will find a tale called “The story of pretty Goldilocks”. This is a VERY bad title-translation of madame d’Aulnoy “La Belle aux Cheveux d’Or”, “The Beauty with Golden Hair”. And in it the main hero - who isn’t a prince, merely the faithful servant to a king - is named “Avenant”, which is a now old-fashioned word meaning “a pleasing, gracious, lovely person - someone who charms with their good looks and their grace”. When Andrew Lang translated the name in English, he decided to use “Charming”. At the end of the tale, the hero ends up marrying the Beauty with Golden Hair, who is a queen, so he also becomes “King Charming” - but the fact Avenant is a courtly hero who does several great deeds and monster-slaying for the Beauty with Golden Hair, a single beautiful queen, all for wedding reasons, ended up having him be assimilated with a “prince” in people’s mind.

And all in all, this “doubling” of a fairytale tale hero named “Charming” in Andrew Lang’s fairytales led to the colloquial term “Prince Charming” slowly appearing...

Though what is quite funny is the difference between the English language and the French one. Because in the English language, “Prince Charming” is bound to be a proper, first name - due to the position of the words. It isn’t “a charming prince”, but “prince Charming” - and again, it is an heritage of madame d’Aulnoy’s habit of naming her characters after adjectives. But in French, “Prince Charming” and “a charming prince” are basically one and the same, since adjectives are placed after the names, and not the reverse. So sometimes we write “Prince Charmant” as a name, but other times we just write “prince charmant”, as “charming prince” - and this allows for a wordplay on the double meaning of the stock name.

#fairy tales#fairytales#prince charming#fairytale archetype#french fairytales#madame d'aulnoy#d'aulnoy fairytales#andrew lang#lang fairy books#names in fairytales

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

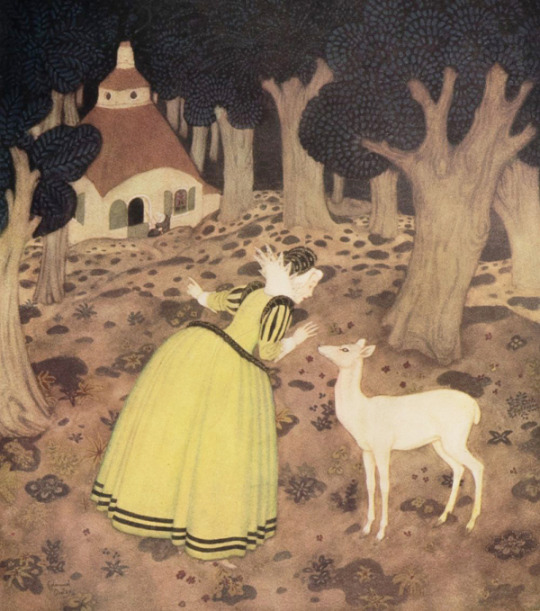

The Fairy of the Desert crashes Princess Toute-Belle's wedding.

Art by Walter Crane for The Yellow Dwarf by Madame d'Aulnoy.

#fairies#fairytales#madame d'aulnoy#walter crane#the fairy of the desert#and yes the turkeys breathe fire#that is a look and she is serving

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

A piece of my soul dies every time someone assumes that Disney owns the entire concept of fairytales. Like people please read about a version that isn't from fucking Disney I promise you it's not hard to do.

I swear to god if I see another Cinderella's stepsister named Anastasia-

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fantasy read-list: B-2

Part B: The First Classical Fantasy

2) On the other side, a century of France...

As I said in my previous post, for this section I will limit myself to two geographical areas: on one side the British Isles (especially England/Scotland), and now France. More specifically, the France of fairytales!

Maybe you didn’t know, but the genre of fairy tales, and the very name “fairy tale” was invented by the French! Now, it is true that fairytales existed long before that as oral tales spread from generations to generations, and it is also true that fairy tales had entered literature and been written down before the French started to write down their own... But the fairytale genre as we know it today, and the specific name “fairy tale”, “conte de fées”, is a purely French AND literary invention.

# If we really want to go back to the very roots of fairy tales in literature, the oldest fairytale text we have still today, it would be a specific segment of Apuleius’ The Golden Ass (or The Metamorphoses depending on your favorite title). In it, you find the Tale of Psyche and Cupid, and this story, which got MASSIVELY popular during the Renaissance, is actually the “original” fairytale. In it you will find all sorts of very common fairytale tropes and elements (the hidden husband one must not see, the wicked stepmother imposing three impossible tasks, the bride wandering in search of her missing husband and asking inanimate elements given a voice...), as well as the traditional fairytale context (an old woman telling the story to a younger audience to carry a specific message). In fact, all French fairytale authors recognized Psyche and Cupid as an influence and inspiration for their own tales, often making references to it, or including it among the “fairytales” of their time.

# The French invented the genre and baptized it, but the Italian started writing the tales and began the new fashion! The first true corpus, the first literary block of fairytales, is actually dating from the 16th century Italy. Two authors, Straparola and Basile, inspired by the structure, genre and enormous success of Boccace’s Decameron, published two anthologies respectively titled, Piacevoli Notti (The Facetious Nights) and the Pentamerone, or The Tale of Tales. These books were anthologies of what we would call today fairytales, stories of metamorphosed princes, and fairies, and ogres, and magical animals, and bizarre transformations, and curses needing to be broken, and damsels needing to be rescued... In fact, these books contain the “literary ancestors” and the “literary prototypes” of some of the very famous fairytales we know today. The ancestors of Sleeping Beauty (The Sun, the Moon and Thalia), Cinderella (Cenerentola), Snow-White (Lo cuorvo/The Raven), Rapunzel (Petrosinella) or Puss in Boots (Costantino Fortunato, Cagliuso)...

However be warned: these books were intended to be licentious, rude and saucy. They were not meant to be refined and delicate tales - far from it! Scatological jokes are found everywhere, many of the tales are sexual in nature, there’s a lot of very gory and bloody moments... It was basically a series sex-blood-and-poop supernatural comedies where most of the characters were grotesque caricatures or laughable beings. We are far, far away from the Disney fairytales...

# The big success and admiration caused by the Italian works prompted however the French to try their hand at the genre. They took inspiration from these stories, as well as from the actual oral fairytales that were told and spread in France itself, and turned them into literary works meant to entertain the salons and the courts. This was the birth of the French fairytale, at the end of the 17th century - and the birth of the fairytale itself, since the name “fairy tale” was invented to designate the work of these authors.

The greatest author of French fairytale is, of course, Charles Perrault with his Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passé (Stories or Tales of the Past), mistakenly referred to by everyone today as Les Contes de Ma Mère L’Oie (Mother Goose Fairytales - no relationship to the Mother Goose of nursery rhymes). Charles Perrault is today the only name remembered by the general public and audience when it comes to fairytales. He is THE face of fairytales in France and part of the “trio of fairytale names” alongside Grimm and Andersen. He wrote some of the most famous fairytales: Sleeping Beauty, Puss in Boots, Cinderella... He also wrote fairytales that are considered today classics of French culture, even though they are not as well known internationally: Donkey Skin, Diamonds and Toads or Little Thumbling. The first Disney fairytale movies (Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella) were based on his stories!

But another name should seat alongside his. If Charles Perrault was the father of fairytales, madame d’Aulnoy was their mother. She was for centuries just as famous and recognized as Charles Perrault - when Tchaikovsky made his “Sleeping Beauty” ballet, he made heavy references to both Perrault and d’Aulnoy - only to be completely ignored and erased by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for all sorts of reasons (including the fact she was a woman). But Madame d’Aulnoy had stories translated all the way to Russia and India, and she wrote twice more fairytales as Perrault, and she was the author of the very first chronological French fairytale! (L’Ile de la Félicité, The Island of Felicity). Her fairytales were compiled in Les Contes des Fées (The Tales of Fairies), and Contes Nouveaux, ou Les Fées à la mode (New Tales, or Fairies in fashion) - and while for quite some times madame d’Aulnoy fell into obscurity, many of her tales are still known somehow and stayed classics that people could not attribute a name to. The White Doe (an incorrect translation of “The Doe in the Wood), The White Cat, The Blue Bird, The Sheep, Cunning Cinders, The Orange-Tree and the Bee, The Yellow Dwarf, The Story of Pretty Goldilocks (an incorrect translation of “Beauty with Golden Hair”), Green Serpent...

A similar warning should be held as with the Italian fairytales - because the French fairytales aren’t exactly as you would imagine. These fairytales were very literary - far away from the short, lacking, simplified folklore-like tales a la Grimm. They were pieces of literature meant to be read as entertainment for aristocrats and bourgeois, in literary salons. As a result, these pieces were heavily influenced (and heavily referenced) things such as the Greco-Roman poems, or the medieval Arthuriana tales, and the most shocking and vulgar sexual and scatological elements of the Italian fairytales were removed (the violence and bloody part sometimes also). But it doesn’t mean these stories were the innocent tales we know today either... These fairytales were aimed at adults, and written by adults - which means, beyond all the cultural references, there are a lot of wordplays, social critics, courtly caricatures and hidden messages between the lines. The sexual elements might not be overtly present for example, but they are here, and can be found for those that pay attention. These stories have “morals” at the end, but if you pay attention to the tale and read carefully, you realize these morals either do not make any sense or are inadequated to the tales they come with - and that’s because fairy tales were deeply subversive and humoristic tales. People today forgot that these fairytales were meant to be read, re-read, analyzed and dissected by those that spend their days reading and discussing about it - things are never so simple...

# While Perrault and d’Aulnoy are the two giants of French fairytales, and the ones embodying the genre by themselves, they were but part of a wider circle of fairytale authors who together built the genre at the end of the 17th century. But unfortunately most of them fell into obscurity... Perrault for example had a series of back-and-forth coworks with a friend named Catherine Bernard and his niece mademoiselle Lhéritier, both fairytale authors too. In fact, the “game” of their “discussion through their work” can be seen in a series of three fairytales that they wrote together, each author varying on a given story and referencing each-other in the process: Catherine Bernard wrote Riquet à la houppe (Riquet with the Tuft), Charles Perrault wrote his own Riquet à la houppe in return, and mademoiselle Lhéritier formed a third variation with the story Ricdin-Ricdon. Other fairytale authors of the time include madame de Murat/comtesse de Murat, mademoiselle de La Force, or Louise de Bossigny/comtesse d’Auneuil. Yes, the fairytale scene was dominated by women, since the fairytale as a genre we perceived as “feminine” in nature. There were however a few men in it too, alongside Perrault, such as the knight de Mailly with his Les Illustres Fées (Illustrious Fairies) or Jean de Préchac with his Contes moins contes que les autres (Fairy tales less fairy than others).

A handful of these fairytales not written by either Perrault or d’Aulnoy ended up translated in English by Andrew Lang, who included them in his famous Fairy Books. For example, The Wizard King, Alphege or the Green Monkey, Fairer-than-a-Fairy (The Yellow Fairy Book) or The Story of the Queen of the Flowery Isles (The Grey Fairy Book).

# These people were however only the first wave, the first generation of what would become a “century of fairytales” in France. After this first wave, the publication of a new work at the beginning of the 18th century shook French literature: Antoine Galland translation+rewriting of The One Thousand and One Nights, also known later as The Arabian Nights. This work created a new wave and passion in France for “Arabian-flavored fairytales”. Everybody knows the Arabian Nights today, thanks to the everlasting success of some of its pieces (Aladdin, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Sinbad the Sailor, The Tale of Scheherazade...), but less people know that after its publication in France tons of other books were published, either translating-rewriting actual Arabian folktales, or completely inventing Arabian-flavors fairytales to ride on the new fashion. Pétis de la Croix published Les Milles et Un Jours, Contes Persans, “The One Thousand and One Days, Persian tales” to rival Galland’s own book. Jean-Paul Bignon wrote a book called Les Aventures d’Abdalla (The Adventures of Abdalla), and Jacques Cazotte a fairytale called La Patte de Chat (The Cat’s Paw). I could go on to list a lot of works, but to show you the “One Thousand and One” mania - after the success of 1001 Nights and 1001 Days, a man called Thomas-Simon Gueulette came to bank on the phenomenon, and wrote, among other things, The One Thousand and One Hours, Peruvian tales and The One Thousand and One Quarter-of-Hours, Tartar Tales.

# Then came what could be considered either the second or third “wave” or “generation” of fairytales. It is technically the third since it follows the original wave (Perrault and d’Aulnoy times, end of the 17th) and the Arabian wave (begining of the 18th). But it can also be counted as the second generation, since it was the decision in the mid 18th century to rewrite French fairytales a la Perrault and d’Aulnoy, rejecting the whole Arabian wave that had fallen over literature. So, technically the “return” of French fairytales.

The most defining and famous story to come of this generation was, Beauty and the Beast. The version most well-known today, due to being the shortest, most simplified and most recent, was the one written by Mme Leprince de Beaumont, in her Magasin des Enfants. Beaumont’s Magasin des Enfants was heavily praised and a great best-seller at the time because she was the one who had the idea of making fairytales 1- for children and 2- educational, with ACTUAL morals in them, and not fake or subversive morals like before. If people think fairytales are sweet stories for children, it is partially her fault, as she began the creation of what we would call today “children literature”. However Leprince de Beaumont did not invent the Beauty and the Beast fairytale - in truth she rewrote a previous literary version, much longer and more complex, written by madame de Villeneuve in her book La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins (The Young American Girl and the sea tales). Madame de Villeneuve was another fairy-tale author of this “fairytale renewal”. Other names I could mention are the comtesse de Ségur, who wrote a set of fairytales that were translated in English as Old French Fairytales (she was also a defender of fairytales being made into educational stories for children), and mademoiselle de Lubert, who went the opposite road and rather tried to recreate subversive, comical, bizarre fairytales in the style of madame d’Aulnoy - writing tales such as Princess Camion, Bear Skin, Prince Glacé et Princesse Etincelante (Prince Frozen and Princess Shining), Blancherose (Whiterose)...

Similarly to what I described before, a lot of these fairytales ended up in Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books. Prince Hyacinth and the Dear Little Princess, Prince Darling (The Blue Fairy Book), Rosanella, The Fairy Gifts (The Green Fairy Book)...

# The “century of fairy tales” in France ended up with the publication of one specific book - or rather a set of books. Le Cabinet des Fées, by Charles-Joseph Meyer. As we reached the end of the 18th century, Meyer noticed that fairy tales had fallen out of fashion. None were written anymore, nobody was interested in them, nothing was reprinted, and a lot of fairytales (and their authors) were starting to fall into oblivion. Meyer, who was a massive fan of fairytales, hated that, and decided to preserve the fairytale genre by collecting ALL of the literary fairytales of France in one big anthology. It took him four years of publication, from 1785 to 1789, but in a total of forty-one books he managed to collect and compile the greatest collection of French literary fairytales that was ever known - even saving from destruction a handful of anonymous fairytales we wouldn’t know existed today if it wasn’t for his work. In a paradoxical way, while this ultimate collection did save the fairytale genre from disappearing, it also marked the end of the “century of fairytales”, as it set in stone what had been done before and marked in the history of literature the fairytale genre as “closed off”. All the French fairytales were here to be read, and there was nothing more to add.

Ironically, Le Cabinet des Fées itself was only reprinted and republished a handful of times, due to how big it was. The latest reprints are from the 19th century if I recall correctly - and after that, there was a time where Le Cabinet was nowhere to be found except in antique shops and private collections. It is only in very recent time (the late 2010s) that France rediscovered the century of fairytales and that new reprints came out - on one side you have cut-down and shortened versions of Le Cabinet published for everybody to read, and on the other you have extended, annotated, full reprints of Le Cabinet with additional tales Meyer missed that are sold for professional critics, teachers, students and historians of literature. But the existence of Le Cabinet, and Meyer’s great efforts to collect as much fairytales as possible, would go on to inspire other men in later centuries, inciting them to collect on their own fairytales... Men such as the brothers Grimm.

#fantasy literature#fantasy read-list#fantasy reading list#fairy tales#fairytales#history of fairy tales#french literature#the one thousand and one nights#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#italian fairy tales#the century of fairytales#evolution of fairytales

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evil fairies: madame d'Aulnoy

When it come to evil fairies, however, the fairytale author to go to is madame d'Aulnoy. Fairies were her preferred antagonists, and so her several dozens of fairytales offer a large cast of wicked deformed fairies, of good fairies turned vengeful and bitter, and of fairies that just happen to be villains because they are the godmothers of the wrong people...

#madame d'aulnoy#d'aulnoy fairytales#illustrations#evil fairies#fairies in fairytales#french fairytales

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY 50TH COMIC!!!! <3

The tale that the Charming parents hail from is unknown, but I do recall seeing something about their tale involving an ogre. Since it's obviously not Puss in Boots, the most likely candidate for their tale in my opinion is The Bee and the Orange Tree, a somewhat obscure late 17th century French fairytale by Madame d'Aulnoy featuring a prince rescuing a princess from her ogre foster parents. I decided to headcanon this as the tale of the Charming parents, with the father being Prince Aime and the mother being Princess Aimee and Darling being expected to inherit her mother's role.

Also, I love Maddie silently judging you in the last panel. Maddie knows what you did last night...

#source: kimbbearly on tumblr#creator: yours truly#images from: youtube printscreen#ever after high#incorrect quotes#daring charming#darling charming#maddie hatter#the bee and the orange tree#headcanons

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

So thought you might like to know a bit about Madame d'Aulnoy

She was a slightly rebellious author from the 1600s, and she's where the term Prince Charming came from, and the very title of Fairy Tale came from her.

Not only that, but she wrote a story where a woman had disguised herself as a male knight, and women, including a queen, had fallen in love with her not knowing she was a woman. Only downside is when she revealed herself to be a woman, she married a king.

But hey! The mother of the Prince Charming title and the Fairytale name also wrote of a knightly woman and kinda women falling for women! Just thought you'd like to know about that!

Ooooh you're right! I DO like to know about Madame d'Aulnoy!!

So this is who we have to thank for having Princess Charming these days! Thank you, Madame d'Aulnoy!

Women are still falling for knight women these days, all is good 🥰💘

And thank you, anon, for interesting message, will definitely read up more on her!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was thinking about the difference between the British "fairy" and the French "fée", and suddenly the perfect comparison struck me.

The "fairy" from British folklore is basically Guillermo del Toro's take on the fair folk, trolls, goblins and other fairies in his movies, from "Pan's Labyrinth" to "Hellboy II". You know, all those weird monsters and bizarre critters with strange laws and customs, living half-hidden from humans, and coming in all sorts of shapes and sizes and sub-species and whatnot. Almost European yokai.

But the "fée" of French legend and literature? The fées are basically Tolkien's Elves. Except they are all female (or mostly female).

Because what is a "fée"? A fée is a woman taller and more beautiful than regular human beings. She is a woman who knows very advanced crafts and sciences, and wields mysterious unexplained powers. She is a woman who lives in fabulous, strange and magical places. She is a woman with a natural knowledge or foresight of the past and the future, and who can appear and disappear without being seen. Galadriel as she appears in The Lord of the Rings is basically the best example I can use when trying to explain to someone what a "fée" in French folklore and culture actually is.

(As a reminder: the fées of France are mostly represented by the Otherwordly Ladies of the Arthurian literature - Morgane, Viviane, bunch of unnamed ladies - or by the fairy godmothers of Perrault or d'Aulnoy's fairytales, to give you an idea of how they differ from the traditional "fae" or "fair folk". All female, and more unified, and so human-like they can pass of or be taken for humans. The "fées" are cultural descendants of the nymphs and goddesses and oracles/priestesses of Greco-Roman-Germanic-Gallic mythologies. That's why they are so easily confused with witches when they turn evil, and when Christianity arose most fées were replaced by the figure of the Virgin Mary, the most famous "magical beautiful otherwordly woman" of the religion)

#fairies#fée#french folklore#french legends#european folklore#fairy#fair folk#tolkien's elves#elves#fées

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

While I'm at it, I want to precise something about the language of these 17th century fairytales like Perrault and d'Aulnoy.

There is something that might be confusing to foreigners not speaking French - that is confusing even to modern-day French folks unaware of the 17th century complexities - but that might be even more confusing for Americans and other people used to a very specific word... "Race".

Race pops up regularly in Perrault's and d'Aulnoy's fairytales, and I do not know how the word was translated in English, but the word "race" of these tales does NOT translate as modern day "race". Yes, race in the racist sense of today did exist by the 17th century... But it was a minor usage not very widespread nor common. What the French word "race" actually refers in these stories is... bloodline.

"Race" was for example used very regularly when princes or princesses speak of their family or ancestors. A princess' "race" means her royal house and royal ancestors. To "perpetuate the race" simply means "having an heir", as simple as that. It is by extension that "race" went from "a specific family or bloodline" to "a specific ethnicity or species". Think of the old house of "house". Like... House Lannister in Game of Thrones? In Perrault's text, it would have been written "the race of the Lannisters".

This is a point I myself came across when doing my paper about ogres, because when talking about the mother of the prince from Sleeping Beauty, Perrault specifies she is "de race ogresse". Today we can understand it as "she was an ogress" or "she was of the ogre species" and it does work since ogres are not human beings in popular culture... But Perrault's original text is much more subtle than that - because remember, in Perrault's fairytales ogres are ambiguously humans or half-humans - and what he actually meant was "she was of ogre bloodline".

By extension, and that was another point of my paper, it is a common part of ogre lore that ogres are always about family. This is why for example the mad clan of "Texas Chainsaw Massacre" is a good example of modern-day ogres: ogres always have a wife, sons, daughters, brothers or sisters somewhere. Perrault's ogres are a bloodline that seemingly mixes and mingles itself with nobility and royalty, and we have an ogre who has seven daughters ; madame d'Aulnoy presents us clans of ogres also with half a doen kids and who are focused on getting grandchildren. And this is even present in the uerco/orco lore of Basile's Pentamerone - for example in "The Golden Root" where the heroine has to fight or win the heart of an entire clan of ogres, mother, aunt, son and daughters (plus baby cousin thrown in a burning oven).

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now that our visual novel Chronotopia: Second Skin has been released, we’re starting an event called ✨Fairytale Friday✨. Every Friday, we’ll discuss a tale from the game’s archives! 😃

Today it's Princess Rosette (by Madame d'Aulnoy).

Princess Rosette is a capricious girl. She doesn't want to marry anyone but "the King of Peacocks 👑🦚".

Her brothers still go to the trouble of finding him & negotiating said wedding. The King agrees, he just wants to be sure she's **that** beautiful 👸.

Of course her evil nurse has to plot her death even though her plan is very stupid 💀. The Peacock King is MAD 😡.

Rosette doesn't die BTW. They throw her mattress overboard but, plot twist, it's made of phoenix feathers so it floats. And then fishes carry the bed 🐟.

A peasant rescues her but she can't possibly eat regular food so her magic dog steals the King's lunch as it's the only food good enough for her 🙃. That's how he ends up finding Rosette. And the brothers are freed! Happy end, yay.

I decided to make Fleur's family the opposite of that specific character. "Golly, my food can't possibly be good enough for your Majesty" became "We only have that so you'd better not be finicky". Rosette kinda pisses me off, to be honest 😅.

💜You can buy Chronotopia on Steam💜

#visual novel#traumendes madchen#chronotopia#fairytale#fairy tales#folktales#fairytale friday#princess rosette#the king of the peacocks

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your favorite fairy tale? Did you have a different favorite when you were a kid?

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (and all adjacent monster groom fairytales lmao), is the obvious, but I also have a soft spot for Red Riding Hood (from a more horror perspective rather than the romance angle some retellings do that i feel...feelings about), Bluebeard's Bride, and The White Cat by Madam d'Aulnoy!

As a kid I LOVED Sleeping Beauty solely because the Disney movie was my all-time favorite movie growing up😭😭🥺

Thank you for the ask!!❤❤

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magical summer: The seven-league boots

THE SEVEN-LEAGUE BOOTS

Category: French fairytales

The seven-league boots (in French “Les bottes de sept lieues”) are a very famous European magical item, that were invented by Charles Perrault for his also very famous “Mother Goose Tales”.

The seven-league boots most famously appear in the fairytale “Hop O’ My Thumb” (Le Petit Poucet) : they belong to the large and wealthy ogre in whose house Hop O’ My Thumb and his six brothers end up after being abandoned by their parents. When the little boys manage to escape the house without being eaten (but not before tricking the ogre into devouring his own daughters), the ogre puts on these magical boots to hunt them down – because their power is that, by just doing one step, the person wearing them can cross seven leagues in total. A league (or “une lieue” in the original French) was an old measurement system of France, that basically covered the distance a man could cross in one hour (roughly 4-5 kilometers), so in total the boots allowed in one step to cross either 28-35 kilometers, either the equivalent of seven hours of walk. Well the exact number of meters the boots allow to cross is not important (as the number “seven” is just a thematic number in this fairytale, the same way there are seven little boys lost in the woods and the ogre has seven daughters) – overall the idea is that the seven league boots allow you to advance very fast on very long distances.

With these boots the ogre easily catches up to the boys, but hopefully for them the ogre is just a lazy glutton/drunkard all these efforts of walking outside his house tire him, so he falls asleep beneath a tree near them. Hop O’ My Thumb then quickly steals the ogre’s boots away and puts them on his own feet. The boots magically shrink to his size so that they would fit (and Hop O’My Thumb is named like that because he is REALLY small, so small people he was literally named after a thumb), and he uses them to cross the country – as his brothers go back home (since now the ogre is powerless and they can easily escape), Hop O’ Thumb uses the boots to go back to the ogre’s house to trick his wife into believing her husband was taken hostage during a war and she needs to give him all of their treasure to pay the ransom. Then he returns to his home with the boots, gives the treasure to his parents so his poor family would become rich – and much later he uses his magical boots to deliver messages to and for the king, becoming the official royal messenger.

Charles Perrault also used the seven-league boots in another one of his fairytales, “Sleeping Beauty”, even though nobody remembers this because they are used in one line, as a little “funny eater egg” detail (so that those that read Hop O’ My Thumb would just wink and nod upon hearing about the boots in Sleeping Beauty) : basically, when the princess pricks her finger and falls asleep, the good fairy godmother that changed the death spell into a sleeping spell is warned of the event by a dwarf wearing the seven-league boots.

Given the French fairytales of the 17th century were actually a distraction and game of small social and literary circles, it makes sense that the other fairytale writers and tellers of the time would reuse and play with the concept : as a result, when Madame d’Aulnoy wrote her fairytale “The orange-tree and the bee”, she had her own ogre (called Ravagio) use seven-league boots to hunt down his adoptive daughter who eloped with the prince he intended to eat for supper.

As you might know, the French fairytales became so popular that they poured into the other cultures of Europe, and so the seven-league boots became an iconic and recurring element in posterior fairytales of other cultures. The seven-league boots almost made it into the Grimm’s fairytales when they included a variation of Hop O’ My Thumb named “Okerlo” (an attempt to translate in German the term “ogre”), but they then removed the tale from their next edition of their tales because they realized it was a French tale, not a German one – but you can still find the “meilenstiefel” or “mile-boots” in the “Sweetheart Roland” story ; and magical travelling shoes in “The King of the Golden Mountain”. They also entered deeply German culture and literature by being featured in the story “Peter Schlemihl” alongside other popular elements of fairytales ; and then being used in the “Faust” play of Goethe. The boots can also be found back in several Finnish and Estonian fairytales under the name “boots of seven Scandinavian miles” (seistsemän peninkulman saappaat, or seitsmepenikoormasaapad) ; we also have in Norway the “femten fjerdinger” boots – the boots of fifteen fjerdinger, roughly 34 kilometers) that pop up in “Soria Moria Castle”. And while not exactly a copy of the seven-league boots, fast-travelling shoes do also appear in various English fairytales, such as in Tom Thumb (in which he has shoes that allow him to travel anywhere) or in Jack the Giant-Killer (an ogre has “shoes of swiftness”).

- - -

But in truth it is hard to say where Perrault's influence stop and traditional folklore begins, because there ARE magical shoes of travel in a lot of folkloric traditions and fairytales that Perrault's own tales couldn't have influenced. For example there is an Hungarian tale called Zsuka and the Devil which has the devil keep "sea-striding shoes" - but here we can draw a parallel as the tale is Hop O' Thumb but with a woman instead of a boy and a devil instead of an ogre. However, when it comes for example to the "sapogi-skorokhody" or "fast-walker boots" that appear in the Slavic fairytales, the link could be harder if not impossible to make. You see, Charles Perrault didn't "invent" the shoes that make you hyper fast or allow you to travel supernaturally. He just kept a tradition that existed before - dating back to Ancient Times, with Hermes and Perseus' flying shoes for example, or the "shoes of speed" of Loki in Norse mythology. It is a recurring element of folklore that does pop up everywhere, the same way his writing of "Hop O' My Thumb" was actually a rewrite and adaptation of a recurring traditional fairytale which had many different regional versions in France. BUT here is the thing: Perrault reinvented this archetype with the iconic name of "X measure boots" or "V measure shoes" - and this is why it is much easier to trace back Perrault's influence on fairytales that use shoes named "the 10 miles boots" or something similar. It is commonly theorized that Charles Perrault found the idea of naming these magical boots as such, because in France at the time (aka 17th century France) by reusing an actual expression of the time: the boots of post-boys at the time were commonly referred to as "seven-league boots". It was a reference to all the road and travels post-boys had to do between two coach inns (in truth it was more like four or five leagues, but anyway). Charles Perrault thought it would be funny to take back this traditional expression and apply it literaly in his fairytales. One last point might also be drawn to the importance of boots in Perrault's fairytales, as they are also a symbol of wealth and social ascension. Boots weren't worn by peasants or low-class, except if they were messengers or domestics to wealthy people : boots were usually worn by precisely these wealthy or upper-class people, either for horse-riding or for the hunt. And in both Hop O' My Thumb and another one of Perrault's fairytale, Puss in Boots, having boots also means for who wears it obtaining riches and a higher social status. In the case of Hop O' My Thumb, the titular little boy steals the boots from a very wealthy giant that has everything in abundance (tons of foods, a big treasure, a vast house, lots of daughters) and once obtained, he uses them first to make his family rich, then to find a high-positioned and well-paid job. Conclusion: if you want to become high-class, get boots.

#magical summer#seven-league boots#fairytales#french fairytales#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#magical shoes#ogre

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aulnoy's famous fairytales: The White Doe (2)

Now that we made a recap for the overall story, let's look at little details here and there, shall we?

1 ) Despite this being one of the most famous and reprinted fairytales of d'Aulnoy, The White Doe/The Hind in the Woods is one of the more dated of these stories. Not just because of the problematic racist elements of "princess Black of Ethiopia", but also because this story was clearly written in honor and reference to the king of the tme, Louis 14. When the fairies create a palace for princess Desired to live into until her fifteenth birthday, and have inside of it the whole history of the world depicted by art pieces, d'Aulnoy breaks her narration to describe in a poem form the "greatest and most brilliant warrior king of History", who is not named but is very clearly Louis XIV. Earlier, when the queen visited the six fairies' palace, the fairies told her that to build it they hired "the architect of the Sun", who basically recreated "the Sun's palace" but in smaller proportions. This is an obvious reference to Versailles, the wonderful castle of the "Sun-King", Louis 14. And if this wasn't enough, there are also several explicit comparisons to an actual historical event contemporary to the story: a royal wedding. Several times throughout the narration, d'Aulnoy says that the beautiful clothes or gorgeous outfits of Desired are identical with or "right behind in term of beauty" to the outfits and jewels worn at a "certain princess" wedding. These are all comparisons made to a certain woman named Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie, who had just married the duke of Bourgogne, aka... Louis XIV's grandchild.

All of this makes the story feel very NOT "intemporal" since, if you don't have the historical context, all those moments seem a bit weird and mysterious. And yet, this fairytale stayed one of d'Aulnoy's most popular ones... My guess is that what seduced people in this story was the imagery it brought rather than the story or writing itself. People's mind and imagination were struck by the supernatural white doe a prince cannot capture, by the visual of this monstrous crayfish terrorizing a queen and fairies by cursing a baby, by the idea of a beautiful girl doomed to live in the dark until her fifteenth birthday...

In fact, the way madame d'Aulnoy writes this tale to celebrate the royal wedding might explain why the main protagonist here, Desired, has such a young age - barely fifteen. Because Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie, upon being wed to Louis XIV's grandchild, was only twelve... [Note however that madame d'Aulnoy did not condone or enjoyed at all child-weddings of this sort - she herself had suffered from an atrocious arranged wedding in her very early life, and this ended up in a complicated business of manipulations, false accusations, exiles and murders - but when you live in 17th century France, you better be a propagandist of the king, especially if you are a woman who tries to write fiction.]

2 ) The beginning of the fairytale is obviously to put in parallel with Perrault's Sleeping Beauty. Same "gift-giving christening by the fairies" scene, the same way the older and more powerful of the fairies arrives to curse the babe only to have her curse "eased" by the others, the list of gifts offered by the fairies being quite similar to the one of the Sleeping Beauty fairies - more explicitely, in the beginning of Sleeping Beauty it was explicitely said the queen visited/tried several miraculous/healing waters to try to have a baby - which is what the queen does in the beginning of this tale, except here it becomes the start of the plot.

3 ) While there is still the manichean divide typical of French literary fairytales of "good fairy and wicked fairy", here d'Aulnoy plays deliberately on the fairies ambiguity, to show that despite acting by a binary pattern, fairies stay a "gray" set of beings. For example, the Fairy of the Fountain or Crayfish Fairy, despite being one of the main antagonists, starts out in the story as a helper and a benevolent force - and in a twist, still does fulfill her role of "good fairy godmother"... but she does so to the princess Black, who is an unwilling/accidental antagonist to the hero of the tale. (A similar process, where the antagonistic fairy is just the fairy godmother of someone other than the hero, was already used by d'Aulnoy in several of her previous fairytales, including The Blue Bird). As for the six benevolent fairies, while they are all good and nice throughout the story, the narration still highlights that they have two sets of chariots, and that when angered they drive the dragons, snakes and panther-driven chariots, hinting that while they are here helpers they can become antagonists in other stories.

4 ) While there is all the racism I talked about before, it is quite interesting to see here that we have two "anti-portraits" of ugly women, meant to oppose Desired's supreme beauty, two anti-portraits that actually help us understand the beauty criteria at work in this end of the 17th century of France. For Princess Black, we see that her ugliness comes from a "dark skin", "big lips" and a "crushed, large nose" - which are, beyond traits typically "African connoted", the opposite of the French ideal of women with very pale skin, very small noses, very thin lips. But in contrast, we also have Long-Thorn who presents another set of flaws. Just like princess Black there is the nose - here too red and too hooked - but beyond that we also have added poor teeth hygiene (Long-Thorn has black and unaligned teeth), and more interestingly a body too tall and too skinny. In general, when it comes to ugliness d'Aulnoy typically invokes smallness/dwarfism or fatness/obesity, but from time to time she also insists that when a character is too tall or too skinny, they also are ugly. Because in this time era, while they wanted women tall, they still didn't want them as tall as men, and there was still a certain "interest in the curve" as without being very large or big, women needed to be plump and fleshy enough to have a body to appreciate (a bony and skinny body was not a beautiful one at the time). Of course, no need to remind you that this was a set of aristocratic ideals - because only the noble and the rich could afford to be chalk-white and "pleasantly plump".

5 ) People have noted that, funnily, the way prince Warrior falls asleep in the woods after eating apples he found there looks like a "male Snow-White". It is quite interesting because, while there probably wasn't a Snow-White reference (since it is not a typically French tale), madame d'Aulnoy had the very Christian background and culture of the apple as the "forbidden fruit" with the whole Garden of Eden story. Which leads to an interesting point...

6 ) This fairytale is a sexy tale. It is not an overtly erotic fairytale, no, but there is an obvious VERY romantic if not sexy if not erotic connotation. This however only appears in the second half of the story, when Desired becomes the White Doe. Desired, turned into a prey, and Warrior, improvising himself a hunter, those two lovers, find themselves reunited deep into the woods (the uncivilized, savage, wild world) after purposefully leaving or fleeing their respective courts (the forest is noted to be filled with dangerous predatory animals, such as bears or lions). Warrior hunts down the White Doe, not knowing that she is the girl he is in love with and obsessed over - though he also grows a fondness, familiarity and love for this white doe. And all the while, the White Doe recognizes her hunter as the one she is in love with, and having to flee from him for her life is said to be just as painful as if she was actually hit by his arrows... Madame d'Aulnoy clearly plays here on metaphors and allegories to weave a whole "game of love" or "love as the hunt", "hunt as the love" section. Warrior hunting for the White Doe, the White Doe making sure she can be hunted while never letting herself be caught, it all evokes a bizarre game of seduction. Warrior clearly treats the Doe as more than a simple pet, claiming he "loves" it and wants it to follow him everywhere and to live with him. When the Doe tricks Warrior to escape him, and Warrior complains to his friend, Becafigue jokes about the situation being like an unfaithful woman cheating on her lover - but the prince answers his joke absolutely seriously. And of course, it is after the prince and the princess spend the night together, sharing their love, in human form, that the spell is broken... [Note: In my previous recap I might have written things backward, saying the spell is broken when "night comes and nothing happens". It is the reverse - they talk all ight long together, and as the morning comes she doesn't transform. Sorry about that.]

Beyond the general image, if things weren't clear eough d'Aulnoy keeps addng little details that make the story even more erotic - almost scandalous. The apple section I mentionned - prince Warrior eating apples in the woods before falling deeply asleep reminds of the first human consuming the "forbidden fruit", and it is when the White Doe dares sleep near him for the first time. When the prince catches the Doe or tries to "woo" it with gifts, it is said he keeps petting it, hugging it, caressing it, kissing it - as a pet, as an animal of course, but we reader know that there is a human woman underneath this doe skin, and so the erotic content cannot be escaped. ESPECIALLY when it is said that, after running from each other all day long, both return to their respective bedrooms "sweating and panting, exhausted by the time they spent together". And don't even get me started on how the prince ends up, to conquer and tie up the doe, hitting her with a single arrow in the leg, making her bleed... This is not a fairytale safe for kids.

7 ) Speaking of love, I did not mention it in my recap, but this fairytale is one of the rare ones of d'Aulnoy to have a moral in the end. To summarize it, d'Aulnoy explains that "With the story of this princess that wanted to leave too soon the dark place a wise fairy placed her in to hide her from the sun's light - and the metamorphosis and misfortunes that resulted from it - you will find an illustration of the dangers to which a young beauty exposes herself when she enters too young, too unprepared in the world. If you were gifted with all the traits and qualities that attract love to you, you better know how to hide them, because beauty can be deadly. If you think that by making others fall in love with you, you will shield yourself from love, well know that by giving too much, you always end up taking." So yes, long story short, this is meant to be more than just a fairy love story, but a warning for girls that too young, too beautiful, too unprepared, throw themselves in the world of love, adult and serious romance, and have to be confronted with the many dangers in it.

8 ) On a more "traditional love story" side, this fairytale accumulates ALL the story devices typical of romances of the type to avoid having the two lovers meet each other. In fact, this is the entire point of this story, the apex and climax and culmination: when princess Desired and prince Warrior can finally see each other in person, and talk to each other. At first you had the exchange of portraits and the sending of ambassadors, then you had the fake princess Long-Thorn hijacking the planned meeting, then the two lovers finally got under the same roof, but not only ignored each other's existence, even when meeting each other they didn't recognize themselves thanks t the doe curse... So when they finally see themselves as humans and touch each other as humans and talk a full dialogue, the story is complete and the curse is broken

9 ) Note however that despite the seemingly virtuous and chaste moral added at the end, madame d'Aulnoy does write the character of a more proactive and manipulative princess that "plays" her male lover. It is she that is happy with his caresses and petting and allows herself to be "touched" of the sort, and it is she that sneaks up by her lover's asleep body, and again the terms of the curse are clear - by day she is forced to become a beast, and to do as beasts do, aka to wander in the woods, aka to return to the world of savagery, primal desire and bestial behavior. On the other side, something that might escape a reader at first glance is that prince Warrior is not supposed to be a "prince Charmng" of the traditional genre. As I said, we are inside d'Aulnoy's second book of fairy tales, and so she reached a point where she plays with the conventions of the genre. In the whole hunt story, we have a brutal lover who tries to kill, seriously wounds though he heals it afterward) and ties up with knots his lover, treating her like a prey and a beast (well, because she IS, but you know) - and there is also the use of the peep-hole by Becafigue that solves the whole problem indeed, but by the undignified way of spying into women's bedrooms (Becafigue had already a not so good behavior when he acted as Warrior's ambassador, encouraging Desired's parents to ignore the "powerless" and "silly fairies" and disobey Tulip's warnings - and in the world of fairy tales one should NEVER underestimate the power of fairies)

But that's just for the second part of the story. In the first part, prince Warrior's behavior is also to be criticized. In fact, it is quite ironic that he is called "Warrior" and introduced as the winner of "three battles", because the first part of his character act has him acting as un-warrior, if not un-manly as possible. He becomes a love-stricken mess, he locks himself in his room talking to a portrait, he despairs of not being able to be with his love, he spends his day dreaming, and doing nothing, and wasting away, with no appetite for anything, making himself sick over lethargy and depression - and so fragile that he can't even wait three months for his loved one to come without fearing he would die. And even worse, when his hopes and dreams of love are crushed, he acts as a selfish coward by simply abandoning his parents, his throne, his court and duties, leaving secretly at night with just one letter behind to explain everything to his parents, and isolating himself from the world in desire to just cry on his own fate forever in some isolated place... We've got some emo teen in love vbes here.

10 ) This fairytale is very "medieval" like in tone. Beyond the "fairy christening" scene that is reused everywhere ever since Perrault and inherits from similar medieval scenes, a la Perceforest, the entire topic of the hunter going after a supernatural, white animal he cannot capture is an iconic topos of medieval literature. Typically this doubles or is tied to the hunter meeting some mysterious woman in the woods, preferably near a fountain, who might take him to a wonderful palace - but this happens rather to Desired's mother, who meets a fairy at a fountain, and is then taken to the six fairies' magical castle.

11 ) In terms of folkloric inspiration, if we use the Catalogue Delarue-Tenèze (a local form of the ATU Index but exclusively covering French fairytales), this story is clearly a literary take on the story type 403, "The substituted fiancee", "The fake fiancee". More specifically, it is a literary take on the 403-B (characterized by the metamorphosis of the real fiancee replaced by a fake one), though there is one element typical of the 403-A (the fact that the prince falls in love with a portrait). While inspired by it, madame d'Aulnoy clearly adds several purely literary elements that make this story very unique. For example the scene of the "fairy-gifts" and the "fairy-curse" at Desired's birth, or the presence of a first fiancee for the prince in the person of the princess Black, two elements united by the character of the Crayfish Fairy or Fairy of the Fountain - this all comes from d'Aulnoy's mind, and is traditonnaly not found in French folktales. And this was clearly placed here only to complicate the originally straightforward story into something much more focused on a "twist-and-turn romance".

#the white doe#the hind of the woods#french fairytales#literary fairytales#french fairy tales#madame d'aulnoy#d'aulnoy fairytales#fairytale analysis

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know I think its kinda perfect that of all the famous Fairytale authors that have existed, in EAH the brothers grimm are the ones who run the school as the headmasters. For a few reasons. To start, something I feel like a lot of people dont know is that historically, the real brothers grimn rarely actually wrote anything original. They mostly just took already written folktales and adapted them for print (along the way adding a few of their own things to retell it as their own version every now and then). So in the context it makes sense that they’re the ones running this school for children of famous fairytale characters from different authors.

Secondly, when you go back in history, a good amount of famous Fairytale authors you might think of (Charles Perrault, Madame d'Aulnoy, ect.) came before the Brothers Grimm. All who wrote famous Fairytales before the Brothers adapted those same stories into their collection. The main exception to this is Hans Christian Anderson who was born after the Brothers Grimn, and I’m pretty sure the only reason why his fairytales weren’t adapted by the brothers was because by the time Anderson’s stories became popular and influential, the brothers were already either retired or dead. Interestingly enough, most of the characters who appear in EAH who are part of Andersons tales didn’t show up until near the end of the show.

With that said, given that in EAH these Fairytales have been going on for generations, the same way the stories have been passed down and retold from author to author over the years in real life, I like to think that before the brothers grimn became the headmasters, there was another famous fairytale author who came before them who was in that position. Like I just imagine going a few generations back and Charles Perrault running the school. And given that after the Brothers Grimn, the next big author (that I’m aware of) was Anderson, he’s probably gonna be the next Headmaster once the grimns retire a a couple of generations later.

#ever after high#eah#fairytale#brothers grimn#charles perrault#hans christen anderson#eah headcanons

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

Moar witches

Cryptid Pet Girl

AL AZIF

The hermit witch. Her nature is secretive. Not all knowledge should be learned. This witch is the product of a girl who learned the truth. She once yearned for knowledge of a creature not many knew or believed in, but upon learning the horrid truths it said, she has sewn her eyes and ears shut. She travels her barrier constantly, never staying in one place for long. She has an ability to leave her barrier and scurry about in the real world, often in forests or caves. If one were to hear her mumblings for too long, they will surely go mad.

Fairytale Girl

SCHNEEWITTCHEN D’AULNOY

The witch of fairytales. Her nature is idealism. A witch who believes the world is purely good and just. She refuses to acknowledge the taint the world possesses and continues to sing in her barrier in whimsy. She waits for a prince to come and whisk her away to a kingdom, but this prince does not exist. She is fated, for all of eternity to sit at her meadow never moving. She is quite gullible and can be easily tricked into a trap.

AL Azif

Al can't go too far away her labyrinth when traveling to the outside world. Her most preferred area is in caves and woods! If you see her during her roam, stay still and don't breath or else she will take you away...to never be seen again (depending the cryptid that is)

Her victims are often curious explorers who heard about her and wanted to see if the rumors are true. Al herself have some appearance to her original magical girl ,but something is clearly very off about her. A ungodly combination of a cryptid and girl. Her familars are the same cryptid she once wanted to know about. They follow her...trying to whisper dark secrets to her...not knowing she can't hear them

Schneewittchen D'aulnoy

This witch often daydreams while singing and whoever enters her labyrinth...She immediately thinks it's her prince charming and immediately gets excited to meet them. Be it magical girl or not, she doesn't care. More often than not..Said victim gets scared to death and her familiars quickly take them away and buried them so not to ruin the witch's veiw on the world. Her familars' job is to do the dirty work undercover and often sing along to the witch's song.

They'll sent out invitations for a tea party in hopes to find the one for their queen. They lure them to her and see if any of those are the best fit for her. So far, they haven't found anyone and may never will...

If you say you're her prince charming...You can lead her to into a trap before killing her by others.

Her familars are really protective of her and love her with all of their hearts..

Those are so cool btw!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@dramaticbackstory replied to your post:

Do you have a bibliography of texts that helped give you this understanding? I have recently become interested in Aulnoy and the whole tradition of fairytales (and particularly women’s fairytales), so I am curious what authors and essays are engaging with them critically !

I'm replying in a separate post yet again so I can provide links, in case they might help you.

I primarily enjoyed Jack Zipes's The Irresistible Fairy Tale for a general understanding of d'Aulnoy and the writers of the time, as well as other ignored and overlooked women authors/compilers of fairy tales. He has also collected and edited 2 volumes of Laura Gonzenbach's Sicilian fairy tales (Beautiful Angiola and The Robber With A Witch's Head) and is about to release an edition of Madame d'Aulnoy's tales in English, illustrated by Natalie Frank called The Island of Happiness. My edition of d'Aulnoy stories is in Spanish though, it also has an informative introduction but I don't know if it'd be of help, it was published in Siruela's collection of fairy tales (from which I also have the Victorian fairy tales edition, since it has my girl Christina Rossetti in it) and it's called El cuarto de las hadas (my editions are older but have no changes).

Apparently, not everyone is a fan of Zipes, for what GR tells me but I found his book pretty neat. I don't agree with him at all times (especially not when it comes to Disney, but I'm used to fighting academics on Disney and fairy tales, in and out of University walls lol), but I think his stuff is well researched and beginner friendly, for an academic book. If you haven't read anything from him, The Irresistible Fairy Tale is a good compendium of a lot of different works he has done through the years and a good portion is on women who wrote/compiled fairy tales (it includes stories from Laura Gonzenbach, Božena Němcová, Nannette Lévesque and Rachel Busk).

For some immediate accessible references, there's an interesting article by Mari Ness in Tor about d'Aulnoy and some of her books are available online with English translations, such as a 1913 edition of her Court Memoirs and some abridged and edited versions of her fairy tales such as The Children's Fairy Land from 1919. There aren't a lot of videos on her, or not as many as I'd expect given her whacky life and big impact on literature, but I very much enjoyed this informative look through her life by Laetitia Miéral, a paper artist who does amazing sculptures and has several d'Aulnoy inspired figures.

For other general spaces to find annotated fairy tales and further looks on theory, I suggest Maria Tatar's Annotated Classic Fairy Tales which is an absolute gem (it has a majority of male authors, though) and SurLaLune as immediately accessible, though after the site change some features got lost.

I have another pile of recommendations for other authors or stories from specific places but I think it exceeds what you needed. I hope this somewhat helps!

(I want to clarify that my opinion on my post was my own and it's just what I take from all I've read and learned, it's not like my take was from a specific author so you can blame me for that one lol)

#I hope this is of use in some way :/#I also apologize to my followers for putting up with my long fairy tale posts#I lost like 3 followers on this but it is what it is#long post#fairy tales#dramaticbackstory#reply#ask#another tag clarification: Zipes names a myriad of contemporary female authors to d'aulnoy#but the authors I named are the ones whose stories#are featured in the book

7 notes

·

View notes