#courtier of edward iv

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Family of Queen Katherine: Sir William Parr of Kendal

Impaled arms of Parr and FitzHugh, Hampton Court Palace Pedigree window of Katherine Parr. Sir William Parr of Kendal (1434-bef. 26 February 1484[2, see notes]/Autumn 1483[1]) KG was a courtier and soldier best known for being the grandfather of Queen Katherine Parr, Lady Anne Herbert, and William, 1st Marquess of Northampton. His granddaughter would become the sixth and final queen of King Henry…

View On WordPress

#1st Baron Parr#Alice Neville#Anne Parr#baron parr of kendal#baron vaux of harrowden#courtier of edward iv#Elizabeth FitzHugh#family of Warwick#family of warwick the kingmaker#favorite of Edward IV#FitzHugh#grandfather of Catherine Parr#grandfather of Katherine Parr#House of York#jane colt#joanna trustbut#lady alice fitzhugh#lady cheney#lady cheyney#lady to Queen Anne Neville#lord vaux of harrowden#Lord Warwick#Richard III#sir thomas more#soldier#War of the Roses#william parr#William Parr of Kendal

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The end of Anne Boleyn marks the more sinister transformation in Henry's kingship which underlay his solemn protestations of spiritual headship and godly reform. Nobody could now call him to account in the sacred or secular realm, and although it goes too far to say that his will was law, since some respect was still due to the judicial process, the legal travesty of Anne's trial and execution shows what his unchecked authority could achieve. It also illustrated the forces which Henry had unleashed by breaking with Rome. From this point onwards, political division would be matched by a level of ideological division previously unknown. Anne had been backed by those who supported religious reform and sneered at papal pretension; her fall was hastened by the efforts of those whose loyalties lay with Princess Mary and the Catholic past. Cromwell had slipped adeptly (and temporarily) from the former group to the latter, and such political reinventions were to remain common, but many continued to be fired by strong religious convictions, allowing religious division to exacerbate political tensions to a dangerous extent." (Henry VIII, Lucy Wooding)

+

"For all Henry's protestations of the contrary, the atmosphere at his court in his final years was almost as unsettled and claustrophobic as during the Wars of the Roses. John Husee answered the charge that he no longer sent reports of state affairs to the Lisles by explaining, 'I thereby might put myself in danger of my life...for there is divers here that hath been punished for reading and copying with publishing abroad of news; yea, some of them are at this hour in the Tower.' Civil order was maintained, but only because Henry sold the bulk of the confiscated monastic lands at rock-bottom prices to willing purchasers to create a whole new class of property-owners with a vested interest in the status quo. Spies and informers stalked the country, safe-conducts were needed to travel abroad and the posts were intercepted-- no one felt completely safe." (Hunting the Falcon, Fox&Guy).

#yeah...this was the watershed moment#this is why these three are the tudor historians i tend to reccomend the most; they have the clearest vision of tudor politics imo#it wasn't the gm which was the turning point that made court divisions worse than ever before. it was may 1536- which made this a reality#things that make you go hmmm.#and i do agree with fox/guy here but i think they argued this better with different examples in different sections#(the atmosphere which led to rebellion; etc.#the Lisle quote is a good piece to support this argument#but spies and informers in the country and safe conducts needed is...slippery#this was also the case during his father's reign. and edward iv's. and many abroad. so . like... )#and i do think the 'almost' is also key here. i wouldn't agree with this at certain points . or 'as much' which has been argued.#bcus for all the conflict hviii did avoid civil war. so...#it isn't to say all was or would be rosy had anne remained queen either. but it is to say as wooding argued...#that this shattered his image and credibility and no one escaped. like...i think it's just interesting to think about#how the exeter conspiracy would've shaped out in the context of the boleyn faction's survival. and how interesting it is#that all their enemies perished at the expense of this man's paranoia . that they had to face the fate they believed their own#enemies deserved...the same scaffold. the same terror .#also some of the jury who condemned them facing execution soon themselves#all just very indicative of how cutthroat courtier ambition was#you could hack and hack and hack away at all the vines but it still might not prevent them from growing back and strangling you instead

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy Guide to the Death of Monarchs

(no, unfortunately this is not a how to guide. Special Branch can now unhitch from outside my house)

To quote The Lion King... The Circle of Life. Monarchs are born, they live, they die. But what exactly happens when a monarch dies?

Dying

The monarch is on their deathbed. Their family, their friends, their advisers (their bit on the side sometimes) are lingering in the room or in the corridor. But of course, death isn't always expected. Usually, if the death is sudden, such as during a military campaign or an assassination, there is a scramble to preserve the news of the death for a time in order to make the necessary arrangements.

Causes of Death

"... Let us sit upon the ground. And tell sad stories of the death of kings; How some have been deposed; some slain in war, Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed; Some poison'd by their wives: some sleeping kill'd; All murder'd," - William Shakespeare, Richard II.

Monarchs die like everybody else. They can die from anything. Disease (Alexander the Great), death at war (Richard I), assassination (Philip III of Macedonia), old age (Elizabeth II), starvation (Richard II), misuse of a hot poker (Edward II), murder at the hands of family (Edward V), childbirth (Jadwiga of Poland), accident (William of Orange... Pussy) , poison (Emperor Claudius) or on the toilet (George II). The death of a monarch is something at will be contested sometimes. If the body is not seen, there may be a belief that they live on. If the monarch dies suddenly, there may be rumours of foul play. No matter how a monarch dies, it will lead to uneasiness.

After Death

The steps after the monarch dies, usually include securing the next heir, proclaiming them to the people, and then working toward a clean succession. This time is delicate, it can be the breeding ground of coups and treacheries. Any claim other than the designated heir must be silenced by the proclaimation of the next sovereign as soon as possible. Child monarchs are extremely at risk during this period as the adults around them will seek to take custody of them. They who hold the monarch hold the power. It is imperative that the heir be notified at once so the stability of the kingdom can be assured.

The X is dead, Long Live the Next Guy

Once they breathe their last, all attention will turn to the next monarch or the scramble to find one. Be it by succession by blood or an election, the designated successor will immediately (even in the absence of a coronation) become the next monarch. Likely they will have been near their predecessor, either at their bedside or at least in shouting distance. But if they are away, they will quickly return to claim their throne. Without delay. Elizabeth II was actually on royal tour when she recieved news her father had died, leading to a hasty scramble back home.

When things don't go according to plan

The monarch passes away. There are tears. Sometimes. There are sometimes coups as I mentioned. Young would be monarchs could be kidnapped, eg. Edward V. Another heir claims the throne instead of the designated heir, eg Lady Jane Grey and King Stephen. Monarchs who die on battlefields can have their bodies stolen (James IV of Scotland) or thrown into a ditch with their crown snatched (Richard III). The death of a monarch is a delicate time and dangerous for all royal family members. In some instances, it would lead to murder. If a son of a previous Ottoman Sultan wished to be the next Sultan, they would order the mass murder of their brothers upon their father's death - usually death by strangulation.

Funeral

The funeral of the monarch is something that is usually planned from day one. There would be some sort of plan in place for the funeral, the when, the where and the how. The monarch might know these plans but the upper rank of courtier and aides would know. Funerals would follow a certain pattern, likely adapting from previous funerals. They would be a public, a lavish ceremony that would see to the closure of businesses, entertainment venues, the arrival of foreign dignitaries and a long procession of the body surrounded by military forces, watched over by the grieving public. If they actually liked the monarch. Some deaths of Kings were met without any sadness such as George IV. There might also be lavish games thrown in the monarch's honour.

Mourning

Mourning is the period of time that the country, the court and royal family grieves publicly. It can last a week or so, like today. Or up to a year. In China, sometimes mourning lasted 3 years or more. Mourning period often came with strict rules about what one could do or dress in. In Edwardian times, there were stages in mourning. Full mourning could last up to a year, with women wearing black with very little ornament and widows covering their hair with bonnets of veils. Second mourning (6-9 months), women's clothes could be adorned with trimming and finally half mourning is the 3-6 month period where colour started to be reintroduced, restricted at first to greys and mauves. There would be no balls, no parties, no sporting during the deepest part of mourning.

#Fantasy Guide to death of a monarch#Death of Monarchs#writing#writeblr#writing resources#writing reference#writing advice#writer#spilled words#writer's problems#writer's life#Writing guide#Writer research#Writer resources#Royal funeral#Royalty#Royal#Royalty and nobility

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTOR

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … January 6

1367 – Richard II of England (d.1400), born Prince Richard of Bordeaux was the second, but only surviving child, of Edward, Prince of Wales (also known as the Black Prince and the eldest son and heir of King Edward III) and his wife, in Bordeaux, Gascony, where the Black Prince was serving at the time. At the age of four, Richard became second in line to the throne upon the death of his elder brother, Edward of Angouleme, and heir apparent when his father, the Black Prince, died five years later (1376). Richard was dubbed a Knight of the Garter by his grandfather only months before the old king died on June 21, 1377. With the death of Edward III, Richard ascended the throne as King Richard II at the young age of ten.

Richard was deemed fit to govern and a series of councils were set up to conduct business in the king's name for the next three years. When the first of these councils met, not only was John of Gaunt, Richard's powreful uncle left out, but also the king's other remaining uncles, Edmund of Langley and Thomas of Woodstock, the Earls of Cambridge and Buckingham respectively. But although John of Gaunt had no official title in Richard's government, he was to remain a leading and influential political figure for nearly the entire reign, though he and the king would not be without their differences.

The young Richard managed to weather a number of crises, including the Peasant's Revolt at the ripe old age of 14. During the following years, the king gradually came of age and moved closer to reaching his majority reign. It was also during this period that he began to come under the influence of a small group of courtiers that were to greedily consume all of his attentions. This group consisted of three primary figures: Sir Simon Burley, the king's tutor since he was a young child; Michael de la Pole, the king's chancellor and Earl of Suffolk after 1385; and Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, whom Richard would ultimately upgrade to Marquis and, soon after, Duke of Ireland.

Richard's close friendship to DeVere was disagreeable to the political establishment. This displeasure was exacerbated by the earl's elevation to the new title of Duke of Ireland in 1386. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham suggested the relationship between the king and DeVere was of a homosexual nature, possibly due to a resentment Walsingham had toward the king.

On top of this, it was also wondered whether Richard was a homosexual since he never bore any children. When thinking of the reign of Richard II, it is difficult not to compare it with that of his great-grandfather, Edward II (another supposed homosexual). Like Edward, Richard had difficulty making decisions for himself and came to be dependent on a small group of favorites for advice, usually bad advice, to run the realm.

This reliance on favorites turned the nobility against him, and he was eventually deposed by Henry IV, and died in captivity in 1400.

1412 – Joan Of Arc, Roman Catholic Saint and national heroine of France (this is a legendary date) (d.1431); Joan wore men's clothing between her departure from Vaucouleurs and her abjuration at Rouen. This raised theological questions in her own era and raised other questions in the twentieth century. The technical reason for her execution was a biblical clothing law. The nullification trial reversed the conviction in part because the condemnation proceeding had failed to consider the doctrinal exceptions to that stricture.

Doctrinally speaking, she was safe to disguise herself as a page during a journey through enemy territory and she was safe to wear armor during battle. The Chronique de la Pucelle states that it deterred molestation while she was camped in the field. Clergy who testified at her rehabilitation trial affirmed that she continued to wear male clothing in prison to deter molestation and rape. Preservation of chastity was another justifiable reason for cross-dressing: her apparel would have slowed an assailant, and men would be less likely to think of her as a sex object in any case.

She referred the court to the Poitiers inquiry when questioned on the matter during her condemnation trial. The Poitiers record no longer survives but circumstances indicate the Poitiers clerics approved her practice. In other words, she had a mission to do a man's work so it was fitting that she dress the part. She also kept her hair cut short through her military campaigns and while in prison. Her supporters, such as the theologian Jean Gerson, defended her hairstyle, as did Inquisitor Brehal during the Rehabilitation trial.

Because Joan wore men's clothes and armor, scholars have speculated about her gender identity and sexuality. Did Joan wear male apparel because she was transgendered? Or did she do so in order to be taken seriously by the men whose support she needed to carry out the orders given by her visions? Was Joan a lesbian or bisexual, if those English terms may be applicable to a French woman living almost six hundred years ago? What relationship did her gender expression have with her sexuality? What about Joan's emphasis throughout her life on her virginity?

It is difficult adequately to address these personal issues based on the historical evidence that we now possess. It is clear, however, that Joan's cross-dressing was a significant part of her life, and that as a cross-dressed warrior and military leader she was venerated by French royalty, soldiery, and peasantry alike.

1854 – English fictional detective, born; What!? Sherlock Holmes? Why include the famous, hawk-nosed detective, a figment of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's fertile imagination? Why? Because almost no one realizes that Sherlock Holmes, whom his creator almost named "Sherinford," was Gay.

He was, of course, the first consulting detective, a vocation he followed for 23 years. In January 1881, he was looking for someone to share his new digs at 221B Baker Street, and there being no personal ads in the Village Voice or The Advocate (remember those?) in those days, a friend introduced him to Dr. John H. Watson.

Before agreeing to share the flat, the two men, immediately attracted to one another, listed their respective character deficiencies. Holmes admitted to smoking a smelly pipe, although he didn't mention that he was a frequent user of cocaine. Watson owned up to a peculiar habit of leaving his bed at odd hours of the night.

"I have another set of vices," he admitted, but, then, so did Sherlock. The two became friends and roommates for the rest of their lives. For the sordid details of the famous marriage of true minds that followed, read Rex Stout's astonishing "Watson Was Woman," in which the famous creator of Nero Wolfe (himself hardly a paragon of butch studliness) reveals that Watson and Holmes were the most extraordinary Gay team in sleuthing history.

In 1971, The Traveller's Companion, Inc., an affiliate of Olympia Press, published a book based on the assumption that Holmes and Watson were lovers: The Sexual Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. Claiming to be from a newly-discovered secret cache of John Watson's papers, the book retells, very erotically, some of the original stories. It is hard-core gay porn at its best!

1961 – Bill Hayes is an American non-fiction writer and photographer. He has written four books – Sleep Demons, Five Quarts, The Anatomist, and Insomniac City – and has produced one book of photography, How New York Breaks Your Heart. His freelance writing has appeared in a number of periodicals, most notably The New York Times.

Hayes was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the fifth of six children, five of them girls. He remains close with his sisters. His mother Jean was an artist; his father John a military man who had lost an eye as a paratrooper in the Korean War. When Bill was three, the family moved to Spokane, Washington, where his father bought a Coca-Cola bottling plant. His mother opened an art school, where Hayes learned to develop and print film. Hayes was close with his maternal grandmother, Helen, from the age of eleven until he left home for college. In high school, Hayes was drawn to the writing of Joan Didion. Hayes attended Santa Clara University in California.

Hayes knew he was gay at a young age, though he had relationships with women in high school and college. He came out at age 24, and considers his orientation to be a core part of his identity.

Hayes' father never accepted him as a gay man and did not maintain a relationship with him, but when John Hayes developed dementia, he came to believe Bill was an old Army friend, and spoke with him warmly. Bill's mother also suffered with dementia until her death in 2011.

Hayes lived in San Francisco for many years, where he worked at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. His partner of sixteen years was HIV-positive. In 2009, Hayes moved to New York City, where he had a relationship with neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks, until the latter's death in 2015. Hayes' experiences in New York and his six-year relationship with Sacks are the subject of his book Insomniac City.

Hayes has described his adult life as "colored by death" – the deaths he dealt with in his AIDS Foundation work, the sudden death of his longtime partner in San Francisco, and later the death of his partner Oliver Sacks.

1965 – Bjørn Lomborg is a Danish author and adjunct professor at the Copenhagen Business School as well as President of the Copenhagen Consensus Center. He is former director of the Danish government's Environmental Assessment Institute (EAI) in Copenhagen. He became internationally known for his best-selling and controversial book, The Skeptical Environmentalist (2001), in which he argues that many of the costly measures and actions adopted by scientists and policy makers to meet the challenges of global warming will ultimately have minimal impact on the world’s rising temperature.

Lomborg spent a year as an undergraduate at the University of Georgia, earned an M.A. degree in political science at the University of Aarhus in 1991, and a Ph.D. degree in political science at the University of Copenhagen in 1994.

Lomborg is gay and a vegetarian. As a public figure he has been a participant in information campaigns in Denmark about homosexuality, and states that "Being a public gay is to my view a civic responsibility. It's important to show that the width of the gay world cannot be described by a tired stereotype, but goes from leather gays on parade-wagons to suit-and-tie yuppies on the direction floor, as well as everything in between".

1968 – Today is the birthday of the Hungarian politician Gábor Szetey. Szetey is the former Secretary of State for Human Resources, a role he held since July 2006. He is a member of the Hungarian Socialist Party.

Szetey publicly declared that he was gay at the opening night of Budapest's Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, on July 6, 2007. He is the first LGBT member of government in Hungary, and the second politician to come out, after Klára Ungár. Szetey's coming out came at the end of a speech on equality and tolerance:

"When we can be proud of being Hungarian, Romanian, Jewish, Catholic, Gay or Straight... If we can be proud of our differences, we will be proud of our similarities. I believe in God. And I believe that all men and women have the right to love and be loved. Everywhere. Love has no party preference. Neither does happiness or choosing a partner. So: I am Szetey Gábor . I am European, and Hungarian. I believe in God, love, freedom, and equality. I am the Human Resources Secretary of State of the Government of the Republic of Hungary. Economist and HR director. Partner, friend, sometimes rival. And I am Gay."

!n the audience was Klára Dobrev, the wife of Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, as well as four other members of the Hungarian cabinet. The Prime Minister supported Szetey on his blog and called for public debate about same-sex relationships in Hungary. Hungary currently recognises same-sex registered partnerships. After the coming out of Mr. Szetey, the Parliament adopted the Registered Civil Union Act, which came into force 1 January 2009.

In a subsequent interview, Szetey declared:

"There is a small but vocal group of right-wing extremists which is intent on offending everyone... According to a survey, 51 percent of the respondents thought my speech was courageous and that it would improve the situation for homosexuals. It's strange that the conservatives, who attach such great importance to neighboring states giving their Hungarian minorities equal rights, couldn't care less about equal rights in their own country."

1976 – Today's the birthday of child actor Danny Pintauro. Pintauro played Jonathan Bower, son of Angela Bower in the series 'Who's the Boss' from 1984 till 1992. He was born as Daniel John Pintauro in Milltown, New Yersey, USA. Pintauro studied English and drama at Stanford University.

Pintauro first appeared on the television soap opera As the World Turns as the original Paul Ryan and in the film Cujo, but he came to prominence on the television series Who's the Boss?. After the conclusion of that series, he was less frequently cast. Pintauro went on to act in stage productions like The Velocity of Gary and Mommie Queerest. He also worked as a Tupperware sales representative and as of 2013, he was managing a restaurant in Las Vegas.

In 1997, in an interview with the National Enquirer tabloid, Pintauro declared that he is gay.

Pintauro (R) with husband Wil Tabares

In April 2013 he was engaged to his boyfriend, Wil Tabares, and they married in April 2014.

In 2015, Pintauro revealed in an interview with Oprah Winfrey that he has been HIV positive since 2003. He also disclosed that he had previously been addicted to methamphetamine.

2015 – Florida recognizes same-sex marriages.

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry VII of England

Henry VII of England ruled as king from 1485 to 1509 CE. Henry, representing the Lancaster cause during the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE), defeated and killed his predecessor the Yorkist king Richard III of England (r. 1483-1485 CE) at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 CE. Known as Henry of Richmond or Henry Tudor before he was crowned, Henry VII was the first Tudor king. Despite having to deal with three pretenders to his throne and two minor rebellions, Henry's reign was largely peaceful and prosperous as, like a master auditor, he steadily increased the health of the state's finances. The king died of ill health in April 1509 CE and was succeeded by his eldest surviving son, Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE).

The Lancastrian Claim

Richard III was one of England's most unpopular kings, and he was accused of being involved in the murder of the two sons of his brother Edward IV of England (r. 1461-70 & 1471-83 CE) who disappeared from the Tower of London. Richard, having eliminated his nephews, made himself king in 1483 CE. His reign would be short and troubled; it was brought to an end by the rise of Henry Tudor, at the time better known as Henry, Earl of Richmond.

Henry was born on 28 January 1457 CE in Pembroke Castle, the son of Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond (l. 1430-1456 CE). Henry was the grandson of the Welsh courtier Owen Tudor (c. 1400-1461 CE) and Catherine of Valois (l. 1401 - c. 1437 CE), the daughter of Charles VI of France (r. 1380-1422 CE), former wife of Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422 CE) and mother of Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71 CE). Henry Tudor's mother was Margaret Beaufort (l. c. 1441-1509 CE), the great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and son of Edward III of England (r. 1312-1377 CE). It was not much of a royal connection, especially as some regarded the Beaufort's as illegitimate, but it was the best the Lancastrians could hope for as their dynastic dispute with the House of York, the Wars of the Roses, rumbled on. Thus, Henry Tudor, returning from exile in Brittany, became the figurehead of the Lancastrians who aimed to topple the Yorkist king Richard III.

Henry Tudor wisely allied himself with the alienated Woodvilles, family of Elizabeth Woodville (l. c. 1437-1492 CE), the wife of Edward IV. Other allies included such powerful lords as the Duke of Buckingham who were not happy with King Richard's distribution of estates, and anyone else keen to see Richard III receive his just deserts. These allies even included the new king across the Channel, Charles VIII of France (r. 1483-1498 CE). The first move by the rebels proved premature and poorly planned so that Henry's invasion fleet was put off by bad weather and Buckingham was captured and executed in November 1483 CE.

Continue reading...

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Henry Tudor meet Elizabeth of Edward IV of England and York in house of york?

Hello, I'm not sure I understand your question. Are you asking if Henry Tudor ever met Edward IV and Elizabeth of York whilst Edward was still king? It's impossible to know, but there might actually be a possibility that Henry met Edward IV (less likely he met Elizabeth imo). To be clear, this is a personal theory based on some of the testimonies given for Henry and Elizabeth's marriage dispensation in 1486.

William, earl of Nottingham (64 years old): 'says that he has known the aforesaid prince Henry well for twenty years and more, and the said lady Elizabeth for sixteen years' => That means he knew Henry since at least 1466, and Elizabeth since 1470/1.

Sir Richard Croft (54 years old): 'says and answers that he has known king Henry well for twenty years, and the said lady Elizabeth for sixteen years' => Again, that means he knew Henry since at least 1466 and Elizabeth since 1470/1.

Sir William Tyler (43 years old): 'says that he has known prince Henry [now king] well for twenty years, and the lady Elizabeth for twelve years' => That means he knew Henry since at least 1466 and Elizabeth since 1470/1.

Those two dates are relevant to the Yorkist establishment (hold this thought). I think it's possible those three men first met Elizabeth of York as she fled with her mother and siblings in 1470 to the Tower and then to Westminster Abbey, or they might have met her in 1471 when Edward IV returned and rescued his family from sanctuary. I don't know exactly what kind of ceremonies were held after Edward's triumph over the Lancastrians but it's possible Elizabeth was present on those occasions.

Some of the other witnesses said they knew Henry for sixteen/fifteen years as well — specifically Christopher Urswyck (Margaret Beaufort's confessor) and Sir William Knyvett. It would make the most sense for the majority of people to say they knew Henry since 1470/1, considering Henry Tudor came to London during the readeption of his uncle Henry VI, and would have met the courtiers at that time. But those three people* — the Earl of Nottingham, Sir Richard Croft and Sir William Tyler — said they knew Henry at least since 1466. What was Henry Tudor doing in 1466?

At that time Henry was a 9 year-old in the custody of William Herbert, an important representative of the Yorkist king in Wales described as 'King Edward's master-lock'. It's possible William Berkeley (later Earl of Nottingham), Sir Richard Croft and William Tyler all knew Henry from visiting the Herberts in Rhaglan Castle**, though it's impossible to say if they had any degree of personal friendship with the Herberts. In 1466 there was however an event that was of importance for both the Herberts and Edward IV.

In that year William Herbert married his eldest son and heir to Mary Woodville, the king's sister (in-law) in a ceremony that took place in Windsor Castle, one of the king's residences. It was apparently such a great event a Welsh poet later praised it in one of his poems dedicated to Willaim Herbert:

The foremost king of Britain and its realm / Gave his sister to him / He held a great wedding-feast in Windsor / For this man, in his royalty / A generous feast for our lord who is of our tongue, / May he be seen again as a prince!

This is pure speculation but I ask myself: is it possible William Herbert took his whole family to Windsor, including his ward Henry Tudor, for his son's wedding feast? If so, many Yorkist partisans such as the Earl of Nottingham and Sir Richard Croft would have had the opportunity to meet Henry on that occasion — in turn, Henry would have had the opportunity to at least see King Edward. Of course there's no way to really know that whilst no concrete evidence comes up, but it's fascinating to think Henry might have seen/know Edward IV.

This isn't taking into account, for example, the possibility that Edward IV might have visited William Herbert at Raglan in one of his travels, to which Henry would have seen him as well. A royal visit to Raglan is the only way I can think of that Henry might have seen Elizabeth of York, as she was only merely a few months-old at the time of her aunt's wedding in Windsor, and would not have attended the ceremony. Furthermore, if Henry and Elizabeth had been present on the same occasion/wedding the three witnesses above would have given the same number of years for knowing them both***, which was not the case.

However, I think a royal visit from Edward IV to Raglan is less likely, given it was not documented anywhere, not even in Welsh poetry, and William Herbert was enough of a patron to have this visit documented in that way. So all in all, I think it's very unlikely Henry Tudor ever met Elizabeth of York before 1485, though I think there's a slight chance that he have met Edward IV in 1466. Again, this is all pure speculation, though.

_____________

* It's important to notice that all three were Yorkist partisans: Sir Richard Croft fought at Mortimer’s Cross, Towton and Tewkesbury on Edward IV's side — he and his brother were tutored with or were the one who tutored Edward whilst Earl of March and his brother Edmund in Ludlow*. Apparently the letter Edward and Edmund jointly wrote to their father Richard of York complained about Sir Richard Croft and his brother. The Crofts were neighbours of the Mortimers, which then encompassed Richard of York and his sons. The Battle of Mortimer's Cross took place on Croft soil. Sir Richard's wife Eleanor ran the household of Edward Prince of Wales, Edward IV's son, and his younger brother (also called Richard Croft) was one of Edward's tutors in Ludlow. Henry VII later made Sir Richard Croft his treasurer, and also made him Prince Arthur’s steward in Ludlow later on.

William Berkeley was created Baron Berkeley by Edward IV and became one of his privy councillors in 1482/3. He might have been the same William Berkeley, knight of the Body, who was attainted in Richard III’s Parliament and joined Henry in exile. It would be weird for the act in Parliament not to mention his title, though, since he was created Earl of Nottingham two days after Richard III was declared king. Either William Earl of Nottingham or this other William Berkeley, knight of the Body, hosted Margaret of York when she visited England in 1480.

** It would be really awkward if William Berkeley (later Earl of Nottingham) was intimate enough to visit the Herberts, considering he killed in battle William Herbert's son-in-law, Thomas Talbot, 2nd Baron/Viscount Lisle (Margaret Herbert's husband) after Lisle challenged him to a trial of arms over the Berkeley lands in 1470. Lisle had been Herbert's ward in the same way Henry Tudor had been. His wife Margaret Herbert miscarried a boy shortly after his death. I believe this is the dowager Viscountess of Lisle that Henry granted a financial settlement in 1492.

*** For example, Sir William Knyvett said he knew Elizabeth of York from the day of her birth 🥺 (and had known Henry for fifteen years, that is, since 1470/1 the Readeption years).

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know that there is another saying about the first encounter between Edward and Elizabeth, besides the common one where Elizabeth's knife was aimed at him, that Edward IV used a knife to force Elizabeth Woodville to become his woman? What is the source that I haven't found?

It was Dominic Mancini who was in London during the events of 1483 in his "Usurpation of Richard III" wrote that Edward wielded a dagger at Elizabeth :

«[W]hen the king first fell in love with her beauty of person and charm of manner, he could not corrupt her virtue by gifts or menaces. The story runs that when Edward placed a dagger at her throat, to make her submit to his passion, she remained unperturbed and determined to die rather than live unchastely with the king. Whereupon Edward coveted her much the more, and he judged the lady worthy to be a royal spouse who could not be overcome in her constancy even by an infatuated king.»

The version of events where Elizabeth was wielding the dagger on the king to defend her honor was written by an italian Antonio Cornazzano in 1468. in his poem “La Regina d’ingliterra” Cornazzano states that, Elizabeth refused to become Edward’s mistress and was ultimately rewarded for her virtue by becoming his queen; the virtuous Elizabeth brought a dagger to the meeting, with which she threatened to slay herself rather than to sacrifice her virtue. It is worth mentioning that Cornazzano was poet and a courtier of the Duke Francesco Sforza, but he has never himself been in England and weather he heard the actual story at the Duke's court or being poet made some literally embellishments when the news that the King of England married his a widow from his own country rather than a foreign princess came about Europe we don't know. Actually Mancini might have been acquainted with the fellow Italian's work and incorporated the story with a dagger in his own manuscript but with a different twist.

Also these two are the only "sources" that mention the coercion on behalf of Edward or dagger of any kind. Other accounts simply have Edward falling in love, without going after Elizabeth’s virtue.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Refusing to adhere to the rules of the royal funeral had consequences, often immediately. The embalming stipulations in De Exequiis Regalibus were clearly disregarded by Edward IV when arranging for the exequies of Henry VI, oft referred to as Henry of Windsor. The 1910 tomb opening offers the physical evidence for this, but there is also narrative and financial evidence that corroborates the accusation of poor handling. The interval between Henry’s death and burial in May 1471 was only three days, as he died at the Tower of London. Henry was paraded with an open visage, so that he could be identified. According to Warkworth’s Chronicle, Henry’s body, while coffined, left blood on the ground, once at St Paul’s and once at Blackfriars. “Cruentation” was the medieval urban legend in which a victim always bled in the presence of his murderer. Henry theoretically bled in the presence of the pro-Yorkist courtiers and the royal house. Bleeding after death was also considered a sign of a martyr, and Henry quickly acquired a saintly following.65 The report of blood might be dismissed as pro-Lancastrian propaganda, but given the condition of Henry’s remains in 1910 and the stipulations of medieval preservation, the “bleeding” may have been the result of a poor embalming. The costs of Henry’s embalming were also low, as most of the money designated for his funeral was for the guarding of the corpse. Only £15 3s 6½d, given to Hugh Brice, was set aside for clergy, cloth, spices (the item that implied embalming), torches for the escort to St Paul’s and to Chertsey, and other items, such as the unmentioned embalmer himself. There was an additional payment of £9 10s 11d to Richard Martyn for twenty-eight yards of Holland linen and other items related to Henry’s exit from the Tower, including the soldiers’ salary for escort. Henry IV had spent far more than this amount caring for Richard’s body in 1400 compared to what Edward IV spent in 1471 for Henry’s body. In 1377, £21 had been spent solely upon the embalming of Edward III. The poor condition of Henry’s bones partially reflect the initial lack of a lead coffin—a measure recommended by the prescriptive texts the Liber Regie Capelle and the Household Articles. His exposure to the populace of London, the financial accounts, and the presence of tissue and hair clinging to the skull indicate that Henry was embalmed, though poorly. The body did not withstand the centuries, or even the days before burial.

Anna M. Duch, "'King By Fact, Not by Law': Legitimacy and exequies in medieval England", Dynastic Change: Legitimacy and Gender in Medieval and Early Modern Monarchy (Routledge 2020)

#henry vi#edward iv#henry iv#richard ii#i would also like to point out that henry v's reburial of richard ii showed a lot more care than richard iii's#it was during henry vi's translation to windsor that his body was dismembered and put inside a small lead chest and one arm lost#with pig bones mixed in#(which is ironic given how hard the r3 society went in on how r3's body should be laid out properly and NOT IN A BOX#...maybe they should have treated his body the way he treated henry vi's. clearly he had no problem with it.)#historian: anna m. duch#the death of henry vi#duch makes a point that henry and r3's burials were less concerned with proper kingly ritual because#they had been attainted by their successors and thus not only denied their kingship but also their noble status#fair point but counterpoint: henry vi deserved better

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before he married Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, King George III set his sights on marrying Lady Sarah Lennox, the daughter of Charles Lennox, the 2nd Duke of Richmond. Lord Bute, the King's advisor, reportedly vetoed the engagement. Why was Lord Bute against Lady Lennox as a royal bride?

So, the first thing to mention is that it was fairly normal to be against a monarch marrying a subject, particularly in England. This was rare in post-conquest English history, and would be mainly associated with some not-great periods/events - Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, which played into the civil wars between the houses of York and Lancaster, and of course most of the wives of Henry VIII and their sad fates. The proper thing for a monarch or even an heir to do was to marry someone else considered royalty in order to strengthen an international alliance and to prevent an imbalance of power in the aristocracy.

Another aspect of the situation was influence. As a young man of about 20 with little experience, George depended greatly on his mother (the dowager Princess of Wales who would never get to be queen herself, whose only hope of being in any kind of power was through her son) and Lord Bute (formerly George's tutor, definitely close to the princess, possibly her lover). If George was married to and infatuated with Lady Sarah Lennox, he would obviously listen to her above all others. A dutiful international match, on the other hand, could eventually produce companionate love but was unlikely to rupture George's interest in listening to those around him. This was particularly a concern because her brother-in-law was Henry Fox, a Whig politician and so Bute's opponent - as a queen consort with her husband's ear, she could have funneled information and opinions from Fox directly to the king, and Fox did promote the match for this reason.

However, we need to be careful in assuming a grand passion and broken hearts. Sources differ on the extent to which George was fixed on Lady Sarah - some say that he was forcibly detached from her by Bute's manipulation, others that he understood the problems with marrying a subject very well himself and would never have done it. We have an account of George making statements implying that he wanted to make Sarah his queen and her turning him down as directly as politeness and subjecthood allowed (ie, by not saying anything) ... from Henry Fox's memoir of the period, not exactly neutral, but at the same time it suggests that a major bar to the marriage was that she simply did not entertain the king's affections.

The 1837 memoir of Sarah's son, Captain Napier, likewise passes down accounts that George liked her and tested the waters but was shut down at first by her own refusal to engage; then after Sarah broke her leg and George had an opportunity to be kind to her rather than just flirtatious, she did accept a second offer of marriage (Napier says), but ...

Then came all the arts and intrigues of courtiers, of clashing interests, of politicians and ministers; then arose the pride and fears of family, then envy, hatred, and malice, and all uncharitableness reared their secret heads while they openly bedecked themselves in smiles and flattery.

Bute et al., of course. Still, according to Napier's recounting of what his mother told him, she was not in love with the king, and in the end she was more upset about the way he never let on that he was secretly contracting a marriage with Charlotte until it was officially announced, letting her think they were still engaged, than she was about actually not getting married to him. Supposedly she was also more upset about her pet squirrel's death around the same time. (Fox agrees with that, btw.)

From a letter by Lady Sarah Lennox to her friend, Lady Susan Fox Strangeways (best name), July 1761:

To begin to astonish you as much as I was, I must tell you that the --- is going to be married to a Princess of Mecklenburg, & that I am sure of it. There is a Council to morrow on purpose, the orders for it are urgent, & important business; does not your chollar rise at hearing this; but you think I daresay that I have been doing some terrible thing to deserve it, for you won't be easily brought to change so totaly your opinion of any person; but I assure you I have not. I have been very often since I wrote last, but tho' nothing was said, he always took pains to shew me some prefference by talking twice, and mighty kind speeches and looks; even last Thursday, the day after the orders were come out, the hipocrite had the face to come up & speak to me with all the good humour in the world, & seemed to want to speak to me but was afraid. There is something so astonishing in this that I can hardly believe, but yet Mr Fox knows it to be true; I cannot help wishing to morrow over, tho' I can expect nothing from it. He must have sent to this woman before you went out of town; then what business had he to begin again? In short, his behaviour is that of a man who has neither sense, good nature, nor honesty. I shall go Thursday sennight; I shall take care to shew that I am not mortified to anybody, but if it is true that one can vex anybody with a reserved, cold manner, he shall have it, I promise him. Now as to what I think about it as to myself, excepting this little revenge, I have almost forgiven him; luckily for me I did not love him, & only liked him, nor did the title weigh anything with me; so little at least, that my disappointment did not affect my spirits above one hour or two I believe. I did not cry, I assure you, which I believe you will, as I know you were more set upon it than I. The thing I am most angry at is looking so like a fool, as I shall for having gone so often for nothing, but I don't much care; if he was to change his mind again (which can't be tho') & not give me a very good reason for his conduct, I would not have him, for if he is so weak as to be govern'd by everybody, I shall have but a bad time of it.

This is followed a week later by an account of how she was freezing cold to him when he spoke to her at court, and her desire to be asked to be train-bearer at the coronation because "it's the best way of seeing the Coronation".

As for asking her to be a bridesmaid, Fox suggests that it would have "seem'd affected" to neglect her: she was enough of a fixture among the unmarried, high-ranking women at court that she merited being asked, and if he hadn't asked her after dumping her it would have looked like a very deliberate snub. Both Fox and Napier agree that she took it very mildly and wasn't bitter about appearing as bridesmaid rather than bride, and Napier says that while Charlotte was very gracious about it, George stared at Sarah through the ceremony. Sarah's letters explain that she thought turning down the offer might have opened her up to gossip - "I was always of the opinion that the less fuss or talk there is of it the better." (Her sister Caroline was very much against her accepting, and they fought about it; Sarah was pretty angry to overhear Caroline complaining about it to a friend outside the family and asked Susan, who was also against it, to keep her opinions to herself because she was sick of being criticized over the decision.) It was after the ceremony that Sarah was mistaken for Charlotte by John Fane, 7th Earl of Westmoreland, who was 75 at the time, hadn't been to court since Queen Anne's time as he was a Jacobite, and could barely see - since she was first bridesmaid, she was at the head of the line and was dressed very richly, so it wasn't so strange for him to make the mistake. Napier attributes her correction to embarrassment rather than fear of Charlotte.

You can find the primary sources I referred to reprinted together in the early twentieth century, which is very handy. It's interesting to read Fox's and Napier's recounting of events for posterity, which strongly uphold Sarah's virtue and wisdom, and compare them to Sarah's actual letters, which show a real human personality so much more strongly. Unfortunately, the letters skip from August to October in 1761, so we can't read Sarah's own description of the wedding and coronation, which took place in September!

(reposted from AskHistorians)

#history#royal history#18th century#georgian#non fashion#coping with professional disappointment by writing mega answers on AH

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

I hate to know some lists of York parties that tried to rescue the prince in the tower and then joined Tudor in exile …

Can you give an example of the Yorkists who defected to Henry Tudor after the crisis in 1483? (other anon ask).

The handiest list of the Yorkist who joined Henry VII is the Wikipedia page of the ill-named Buckingham's rebellion. Some names aren't what I would qualify as 'Yorkist' as Reginald Bray who clearly rebels because Henry Tudor was the son of his liege, Margaret Beaufort, but most of them are Edwardian servants.

We do not know who attempted to rescue the Princes in the Tower in summer 1483. Maybe some of them are on that list, maybe they aren't, we don't know.

But a typical Yorkist rebel could be Giles Daubeney, who's a small landowner in the South-West and esquire of the king's body (basically a mix of courtier and servant and sometimes bodyguard). He rebelled in 1483 very probably at disgust for Richard III's usurpation and the murder of his nephews.

Another one is Robert Willoughby, who was High Sheriff of Cornwall, then High Sheriff of Devon and High Steward of the duchy of Cornwall. He is more dangerous than Daubeney to the extent that he is very connected in the South-West: an already prominent landowner who married an heiress and have a firm institutional position through offices in the duchy of Cornwall who's a major asset of the Crown. His support means a lot.

101 people were attainted at Richard's only parlement. Some of them are Woodvilles, others are connected through familial links to Henry Tudor but most are gentrymen who served Edward IV in the South-West/South-East.

Two aside here:

I'm happy to receive asks but answers will be quite slow/non-existent until march for professional reasons

Buckingham's rebellion is quite ill-named considering his uprising was the weakest, that he was isolated amongst rebels and that historians still speculate on whether it was another uprising with different objectives but opportunistically chose to rise simultaneously with the Edwardian Yorkists.

#war of the roses#Buckingham's rebellion#who really should have another name#Richard III#Edwardian servants

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry VI issued 21 deprivation orders, all of which were revoked; Edward IV had 140 people stripped and 86 overthrown; Richard III deprived 99 of 100 reversals; Henry VII, 138, 52 Reversal

John Bell, the main rebel in Kent County, according to the royal indictment, served from November 1483 to 1484.

William Bampton was nominated in January 1484 in Richard III's parliament for the Salisbury Uprising and was nominated elsewhere on October 18, 1483.

William Baskett, a gentleman, was awarded the Order of Salisbury in the Parliament of Richard III in January 1484 for his involvement in the Salisbury Uprising, and received the Order of Salisbury elsewhere on October 18, 1483.

Geoffrey Beauchamp was one of the main rebels accused by Lord Scrope on November 13, 1483 in Bodmin.

Richard Beauchamp, Lord Saint Amand, was awarded in January 1484 in the Parliament of Richard III for his uprising in Newbury, Berkshire, and other places on October 18, 1483 Roger Torkots' stepson.

Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, was elected in the third act of Parliament by Richard III in January 1484. The mother of the king's great rebel and traitor. She wrote a letter to Henry, telling him to start a war. She donated a large amount of money on charges of treason in London and other places, conspired to destroy the king and assist Buckingham. She was handed over to her husband Thomas Stanley for care.

William Berkeley, Knight of the Body, was awarded in January 1484 in Richard III's council for his uprising on October 18, 1483 in Newbury, Berkshire, and other places He has served as a police officer in Southampton and Winchester. In 1480, when Margaret of York visited England, he received her. He is suspected of colluding with Southampton Mayor Walter Mitchell, and his relative Edward is a town official. Joined the exiled Henry Tudor.

John Bevean, a gentleman, won an award in the Parliament of Richard III in January 1484 due to the Salisbury Uprising, and was awarded elsewhere on October 18, 1483.

James Blount, a police officer stationed in Hams, is a descendant of the York family who served Edward IV and fought for him to regain the throne.

He was the warden of John de Vere, Earl of Oxford. John de Vere was a stubborn Lancastrian who had been imprisoned in the Hams garrison on orders from Edward IV since 1475. On October 29, 1484, Richard III heard of a conspiracy to rescue him and ordered Oxford to return. However, James Blount and John Fortescue, the porter from Calais, defected to Henry Tudor and took Oxford with them. In December, Lord Darnham, the Governor of Calais, attacked and occupied Hams, imprisoning several people, including Brent's wife. In January 1485, Oxford and others returned to Hams to rescue them. In the ceasefire agreement, the Calais army allowed dissatisfied individuals to leave. They joined the ranks of Henry Tudor.

[Haha] [Haha] [Haha] [Haha] [Haha] [Haha] It's so funny

In January 1484, John Boutayne, a royal guard, was awarded a prize in Richard III's council for his uprisings in Kent and Surrey, Maidstone, Gravesend, Guilford, and other places from October 18 to October 25, 1483.

He was sent to Kent by John Howard, Duke of Norfolk and a staunch supporter of Richard III, to quell the uprising. However, during the riots at Gravesend Market on October 13, 1483, he killed 'Mr. Mobley'.

Under the rule of Edward IV, there were 40 body attendants; 24 people are from the south. Among these 24 people, 11 rebelled. Among the remaining 13 people, 5 lost their peace committee, and 2 rebelled in 1484.

Under the rule of Edward IV, there were 24 body knights; 10 people are from the south. Six out of ten people rose in 1483.

50% of Edward IV's Southern knights and attendants (17 out of 34 courtiers) led the uprising.

From 1478 to 1482, 48% of the people who served as sheriffs in 14 counties under Edward IV rebelled in 1483; 35% of security commissioners rebelled.

40% of southern judges and sheriffs rebelled.

35% of the security commissioners selected by Richard rebelled. This proportion has risen to 61%, including those who stepped down directly after the uprising.

Out of the 10 magistrates elected in November 1482, 4 rebelled.

0 notes

Text

HENRY HAD LEARNED THE FUNDAMENTALS of his bride to be. He knew that she was the sole legitimate heir to her father’s crown, and that she was his acting regent, for reasons Henry did not understand. He had been told that she was a bright young woman, and had been educated in a way not dissimilar to himself.

Henry did not, of course, know much of her as a person. He hoped they would get along well; or, at least, that they could grow to. He was not so foolish as to imagine it would be love at first sight, as in the love of King Edward IV & his queen, Elizabeth Woodville. Still, Henry would like their marriage to at least have a foundation in mutual respect, if nothing else.

“I am sure the princess will be grateful of your well wishes,” Henry answered, with a reserved smile. Henry had a fierce loyalty to his sister, Mary. He cared for the Princess Elizabeth as well- very much, in fact- but his relationship with her mother made that relationship rather more complicated. “She spoke highly of you upon her return.”

Feeling foolish for not having done so earlier, Henry extended an arm to the Princess Relta. “I do hope you will find yourself happy here,” he said, blushing to his cheeks. Henry spoke quietly; loud enough for his betrothed to hear, certainly, but not loud enough for the nosy courtiers nearby. “If there is anything you should want, you need only ask. Anything in my power to make you happy, I intend to do.”

@officerwaltons continued from [here]

HENRY HADN’T TAKEN PART in the marriage treatise that had brought the Princess Relta to England, which was the custom. His father’s marriages aside, English royals did not traditionally make love matches. Perhaps the most recent of the sort was his great-grandparents, King Edward IV and his queen, Elizabeth Woodville. Henry held no boyish fantasies of such a romance; he preferred, actually, to have it arranged by others.

He had seen enough of what love matches brought- beheading, orphaned children, and tattered lives. An alliance, Henry thought, was much simpler.

“Princess,” the young man bowed to his betrothed. “It is an honor to welcome to you to my father’s court. Did you journey well?”

Much as Relta loathed the idea of an arranged marriage — or marriage at all — she knew she had to do this for England and Lunaruz alike.

Word was that Crown Prince Henry Tudor was a good man, less lustful and foul tempered than his father. She recalled his mother’s motto — humble and loyal. Would the prince wish that behavior of Relta as well? She couldn’t help but wonder about it, for she was loyal to Lunaruz above all else, even her father.

“Your Highness,” she curtseyed back out of respect, “It is an honor to be welcomed here, and fortunately yes,” she responded with a kind smile. “It seems that your god and mine smile upon our union by granting me safe passage,” the princess added.

Relta was arguably Henry’s equal, being her father’s only legitimate heir and also his current regent to balance out the bloodlust of his in his later years. She knew this, yet would play the part expected of a future English queen — humble and kind.

No, that could not be her motto, even if it was the role she played. She was destined and true, as she’d insisted was her motto since she was a young teenager. Perhaps this Prince Henry would accept her for such, even if she doubted they’d be a love match. Friends she could stomach, as long as both proved loyal.

“I met your sister once, Princess Mary, upon her traveling to Lunaruz. She told me a bit about your customs when we got time together,” Relta informed Henry, having enjoyed Mary’s company. “I hope she fairs well in her marriage,” Relta added, hoping extending a kindness to his legitimate sister would benefit her.

Relta had always admired what she’d read of Catherine of Aragon, but knew she could not be an obedient or subservient queen, or one who’d kneel and beg at her husband’s feet. Hopefully, she prayed, Prince Henry would understand the fire that burned in Relta since she discovered she was heir to Lunaruz.

#𝐎𝐅𝐅𝐈𝐂𝐄𝐑𝐒’ 𝐋𝐎𝐔𝐍𝐆𝐄— character interactions#muse: henry tudor#interactions: joyfulmagic#henry is such a love

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

"while anne might not have kept elizabeth beside her on a pillow under the royal canopy as a baby" ?? sorry, im lost here.

oh, sorry, that was just me referencing something else that was in the spanish chronicle that we don't have exact contemporary corroboration for.

day and night she would not let this daughter of her out of her sight. whenever the queen came out in the royal palace where the canopy was, she had a cushion placed underneath for the child [....]

so...i mean, a few issues with that, primarily that elizabeth, as was typical of royal infants, did not reside in palaces with her parents but rather in her own establishments. which they did visit frequently, but surely not with the frequency that one could claim 'day and night [anne] did not let her out of her sight'.

however, the comment they were 'very particular in rearing her', suggests overly-doting parents, perhaps publically affectionate, and that much is corroborated by chapuys, at least in regards to henry "carrying her in his arms" several days in a row. i was just making the point that we don't have a contemporary corroborating such public affection between jane seymour & mary in the same way from the SC.

#ive talked about the spanish chroncile before; it gets too many things wrong -- not just 'well who can really NEVER be sure' things like#this-- but extremely basic facts that any even palace servant would know-- that anne of cleves was the fourth wife not the fifth.#that george boleyn was a duke. that katherine parr's brother was 'lord rochford#for me to believe it was by an actual tudor courtier#more likely a merchant with a connection to the tudor court#and also that there was enough distance from these events for a mix up#i believe it was written during the reign of edward vi#anon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made this point while writing for History of Westeros the other week, but one minor aspect of the Dance of the Dragons I find interesting is the almost unconscious chromatic designations of the two factions. Despite the fact that the fifth anniversary tourney of 111 AC provided the basis for the “green” and “black” identifications of the rival court parties, Gyldayn does not actually dwell on the costume choices of queen and princess: Alicent is merely noted to have worn a green dress without any specific reason for doing so, and while Rhaenyra’s outfit colors are described as “Targaryen red and black”, there is no confirmation in the text that Rhaenyra wore these colors specifically to spite Alicent or because she knew Alicent would not also wear red and black (as indeed, we don’t even know what Alicent’s then-three children were wearing at this opening feast, nor the king, nor any other courtiers). Nor is there any obvious, exclusive, or long-lasting public/physical association with these colors for either faction: neither side took to dressing only in that color, Aegon II in fact drew on the specifically Targaryen legacy of the Conqueror in his choice of (a notably black and red) crown (after his mother had already done so with his name and possibly his marriage), and the two sides fought under “the golden three-headed dragon that Aegon had taken for his sigil” and “Rhaenyra's red dragon quartered with the moon-and-falcon of her Arryn mother and the seahorse of her late husband”.

Of course, this is not to suggest that Rhaenyra and Alicent - and, perhaps more to the point, the respective theories of succession that each woman represented - were not already at odds by 111 AC; on the contrary, the king had already fired the queen’s father, Otto Hightower, as Hand for “hector[ing]” him over the question of succession. Nor is this to suggest that the tourney was not an opportunity to express the factional dispute in a socially acceptably violent context: after all, it was Rhaenyra’s very public champion Ser Criston Cole (wearing her favor, no less) who subsequently “unhorsed all of the queen’s champions, including two of her cousins and her youngest brother, Ser Gwayne Hightower”. However, whether or not Rhaenyra and/or Alicent had intended to create a specifically “black” or “green” party, respectively, the fact that the women dressed in very different colors provided their factional supporters with a convenient shorthand for identifying themselves. In some sense, then, their factions existed almost outside the women themselves, determining how the respective members would be styled (no pun intended) without the conscious input of their ostensible leaders,

(The regular reminder that I am not talking about or analyzing That Other Show and that you can kindly leave your discussions of That Other Show out of my posts or be blocked by me.)

This discussion reminds me a bit of the Wars of the Roses. Although both the Yorkist and Lancastrian factions had heraldic associations with white and red roses, respectively, neither side used its respective rose in any sort of uniform or absolute manner (and indeed, it’s not even clear that Lancastrian forces specifically ever fought under the banner of the red rose). Various Yorkist and Lancastrian leaders instead used a variety of personal and dynastic badges over the long course of the conflict: the falcon and fetterlock of Richard, Duke of York, for example, the sun in splendor of Edward IV, the white boar of Richard III, the chained antelope of Henry VI, or the red dragon of Cadwaldr of Henry VII (to name just a very few). The designation of the sides as “warring roses” or “quarreling roses” came only after the conflict had ended (with the specific name “the Wars of the Roses” a few centuries later), the variety of battle standards forgotten in the poetic triumph of the united Tudor rose. As with the greens and blacks, the personal badges of the competitors in the Wars of the Roses were somewhat forgotten in favor of this easy shorthand, a quick and uniform way to refer to the two sides of the civil war.

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isabel of Castile and Edward IV of England

In February 1464, when Isabel was not quite thirteen years old, her brother Enrique IV of Castile accepted the English offer and agreed to give her in marriage to King Edward IV, in a gesture of political alignment between the two countries. This would at once make Isabel a queen. It might have been a generous act on Enrique’s part, to help ensure an illustrious future for his half sister. However, it is just as likely that the marital alliance was Enrique’s attempt to remove Isabel from the direct line of succession in Castile and relocate her to a distant land, particularly at a time when rumors were brewing about Princess Juana’s legitimacy. Regardless of Enrique’s motives, however, the proposition of marriage to the English king would have been appealing to most young women. The twenty two-year-old Edward of York had recently assumed the throne of England. Charming, blond, strong, and six feet four inches tall, he was intelligent, excellent at the courtly games of hunting and jousting, dressed elegantly in furs and rich jewelry, and was fond of chivalric romances. This combination of traits made him irresistible to women, upon whom the lusty young king was eager to lavish his own attentions.

Marriage to Edward would of course have been an intriguing, even dazzling, prospect for Isabel, who loved hunting and stories of courtly love. It would give her a splendid husband, make her the envy of other women, and install her as queen of a kingdom with which she had long ancestral links. Isabel believed that Spain and England had a natural dynastic affinity. Her grandmother was Catherine of Lancaster, the daughter of the famous English nobleman John of Gaunt, son of King Edward III, whose marriage to Constance of Castile had made him a contender for the throne of Castile.

Edward IV was also descended from John of Gaunt, making him a distant cousin of Isabel. If the alliance proceeded, an old family tie would be reconnected. The marriage presented some strategic opportunities for England as well. Edward’s descent from King Pedro of Castile, through Pedro’s daughter Isabel Duchess of York, already made Edward a potential claimant to the Castilian throne, and this claim would be strengthened if he were to marry Isabel. English poets were already writing doggerel extolling Edward as not just king of England and deserving of France but also the future inheritor of Spain: “Re Angliae et Franciae, I say, It is thine own, why sayest thou nay? And so is Spain, that fair country.”

Once the match was proposed, Isabel waited at home for the decision. Given the difficulties in communication at the time, messages from one court to another sometimes took months because courtiers needed to physically travel from one place to another. Finally she somehow learned, to her great disappointment, that another woman had been selected, in a most unusual way. Unbeknown to the king’s councilors, who were negotiating Edward’s marriage prospects in both France and Spain, King Edward had already impulsively married a comely widow, Elizabeth Woodville. In faraway Castile, Isabel, still a young teenager, brooded over her rejection, much later telling ambassadors that she had been passed over for a mere “widow of England,” making it clear she had harbored resentment at her rejection for the next twenty years. Like Elizabeth Woodville, she was not a woman to suffer a slight lightly or forgive easily.

Source:

Kirstin Downey, Isabella: The Warrior Queen

#Isabel de Castilla#Isabella of Castile#Edward I of England#Henry IV of Castile#Enrique IV de Castilla#Elzabeth Woodville#Isabel tve#The White Queen#Spanish history#English history

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

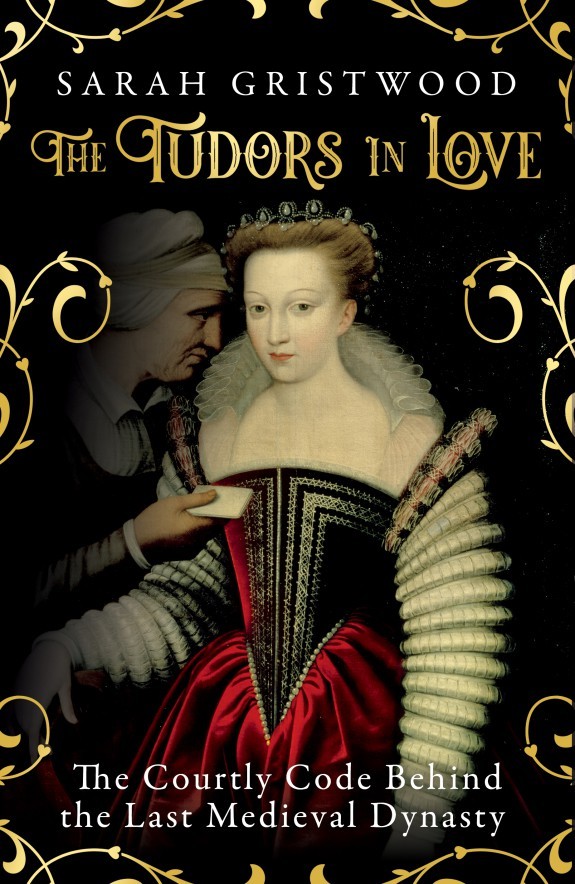

The Tudors in Love: The Courtly Code Behind the Last Medieval Dynasty, Sarah Gristwood (23 September 2021)

The dramas of courtly love have captivated centuries of readers and dreamers. Yet too often they’re dismissed as something existing only in books and song – those old legends of King Arthur and chivalric fantasy. Not so. In this ground-breaking history, Sarah Gristwood reveals the way courtly love made and marred the Tudor dynasty. From Henry VIII declaring himself as the ‘loyal and most assured servant’ of Anne Boleyn to the poems lavished on Elizabeth I by her suitors, the Tudors re-enacted the roles of the devoted lovers and capricious mistresses first laid out in the romances of medieval literature. The Tudors in Love dissects the codes of love, desire and power, unveiling romantic obsessions that have shaped the history of this nation.

Woodsmoke and Sage: The Five Senses 1485-1603: How the Tudors Experienced the World, Amy Licence (31 August 2021)

Using the five senses, historian Amy Licence presents a new perspective on the material culture of the past, exploring the Tudors’ relationship with the fabric of their existence, from the clothes on their backs, the roofs over their heads and the food on their tables, to the wider questions of how they interpreted and presented themselves, and what they believed about life, death and beyond. Take a journey back 500 years and experience the sixteenth century the way it was lived, through sight, sound, smell, taste and touch.

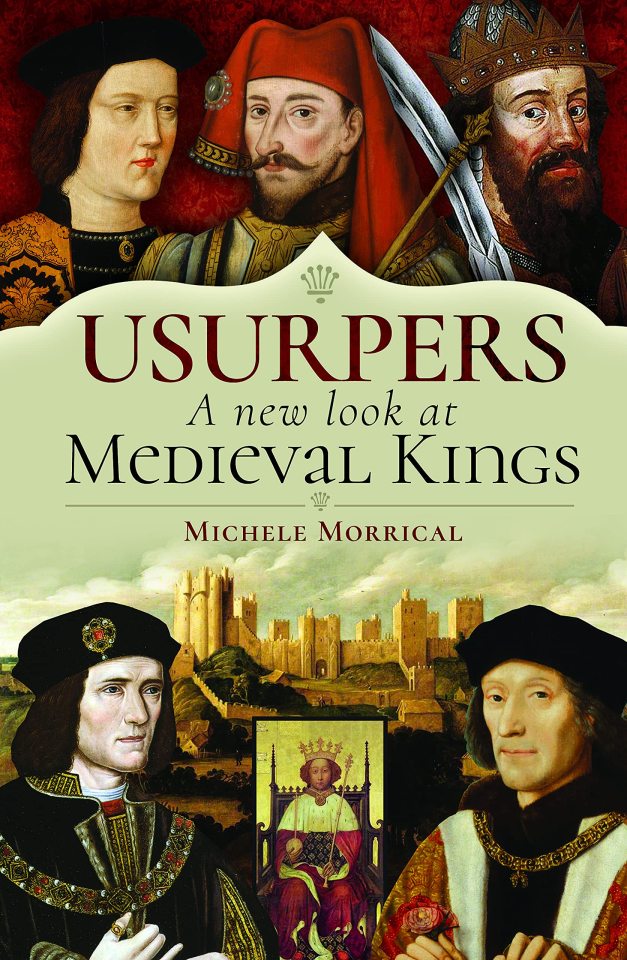

Usurpers, A New Look at Medieval Kings, Michele Morrical (30 September 2021)

In the Middle Ages, England had to contend with a string of usurpers who disrupted the British monarchy and ultimately changed the course of European history by deposing England\x27s reigning kings and seizing power for themselves. Some of the most infamous usurper kings to come out of medieval England include William the Conqueror, Stephen of Blois, Henry Bolingbroke, Edward IV, Richard III, and Henry Tudor. Did these kings really deserve the title of usurper or were they unfairly vilified by royal propaganda and biased chroniclers? In this book we examine the lives of these six medieval kings, the circumstances which brought each of them to power, and whether or not they deserve the title of usurper

The Boleyns of Hever Castle, Owen Emmerson and Claire Ridgway (1 August 2021)

In The Boleyns of Hever Castle, historians Owen Emmerson and Claire Ridgway invite you into the home of this notorious family.

Travel back in time to those 77 years of Boleyn ownership. Tour each room just as it was when Anne Boleyn retreated from court to escape the advances of Henry VIII or when she fought off the dreaded 'sweat'. See the 16th century Hever Castle come to life with room reconstructions and read the story of the Boleyns, who, in just five generations, rose from petty crime to a castle, from Hever to the throne of England.

Fêting the Queen: Civic Entertainments and the Elizabethan Progress, John Mark Adrian (30 December 2021)

While previous scholars have studied Elizabeth I and her visits to the homes of influential courtiers, Fêting the Queen places a new emphasis on the civic communities that hosted the monarch and their efforts to secure much needed support. Case studies of the university and cathedral cities of Oxford, Canterbury, Sandwich, Bristol, Worcester, and Norwich focus on the concepts of hospitality and space―including the intimate details of the built environment.

Hidden Heritage: Rediscovering Britain’s Lost Love of the Orient, Fatima Manji (12 August 2021)

Throughout Britain's galleries and museums, civic buildings and stately homes, relics can be found that beg these questions and more. They point to a more complex national history than is commonly remembered. These objects, lost, concealed or simply overlooked, expose the diversity of pre-twentieth-century Britain and the misconceptions around modern immigration narratives. Hidden Heritage powerfully recontextualises the relationship between Britain and the people and societies of the Orient. In her journey across Britain exploring cultural landmarks, Fatima Manji searches for a richer and more honest story of a nation struggling with identity and the legacy of empire.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries: A New History, James Clark (14 September 2021)

Drawing on the records of national and regional archives as well as archaeological remains, James Clark explores the little-known lives of the last men and women who lived in England’s monasteries before the Reformation. Clark challenges received wisdom, showing that buildings were not immediately demolished and Henry VIII’s subjects were so attached to the religious houses that they kept fixtures and fittings as souvenirs. This rich, vivid history brings back into focus the prominent place of abbeys, priories, and friaries in the lives of the English people.

Catherine of Aragon: Infanta of Spain, Queen of England, Theresa Earenfight (15 December 2021)

Despite her status as a Spanish infanta, Princess of Wales, and Queen of England, few of her personal letters have survived, and she is obscured in the contemporary royal histories. In this evocative biography, Theresa Earenfight presents an intimate and engaging portrait of Catherine told through the objects that she left behind.

Devil-Land: England Under Siege, 1588-1688, Clare Jackson (30 September 2021)

As an unmarried heretic with no heir, Elizabeth I was regarded with horror by Catholic Europe, while her Stuart successors, James I and Charles I, were seen as impecunious and incompetent, unable to manage their three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. The traumatic civil wars, regicide and a republican Commonwealth were followed by the floundering, foreign-leaning rule of Charles II and his brother, James II, before William of Orange invaded England with a Dutch army and a new order was imposed.

476 notes

·

View notes