#cops 1922

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Buster’s Best Loved Stunts

Steamboat Bill Jr. 1928

Two tons of house front falls on top of Buster in what is surely his most famous stunt, if not the most famous stunt of all time. His salvation comes in the form of a small upstairs window, wider than his shoulders by only a couple of inches.

Were he to fail to stand exactly where the nails that had been driven into the ground to mark the spot, were he to move forward even slightly, he would be killed instantly.

Co-director Chuck Reisner couldn’t bear to witness the scene. “My father, who was a very religious man, a Christian Scientist, had a practitioner up there,” his son, Dean, remembered, “and they were praying all day because here comes this stunt and my father couldn’t bear to see it. He and the practitioner were off praying in one corner and waiting to find out whether Buster came through it or not.

“Two extra women on the sidelines fainted,” Keaton said in 1930, relishing the memory, “and the cameramen turned their backs as they ground out the film.” The thrilling shot came off beautifully. “But it’s a one-take scene and we got it that way. You don’t do those things twice.” He would later claim that the house scene was one of his "greatest thrills," before noting, "I was mad at the time, or I would never have done the thing."

Cops 1922

Although by his own admission Buster only ever had one day of schooling, he must have learned a little about physics along the way.

I don’t know how else he was able to convince himself that he could perform this iconic stunt Cops without ripping his arm out of its socket.

No special affects were used here, and no camera trickery either. Just incredible timing, incredible strength and somehow managing to factor his height and weight with the speed of the car and deciding to risk it.

The Navigator 1924

This scene was originally intended to be filmed in a swimming pool, but Buster wanted deeper water, so after destroying an indoor pool in Riversdale California by over-filling it with water and cracking the bottom, he decided to film in Lake Tahoe where the water was deep, very clear but very cold. Buster could only stay underwater for a few minutes at a time.

As always Buster insisted on doing it himself despite the dangers and even had a special divers helmet made with a clear front screen so that the audience could see his face and know he wasn’t cheating them.

The General 1926

In what filmmaker James Blue would call “a moment of almost almost pathetic beauty,” Buster sits dejectedly on the coupling rod that connects the great metal wheels of the General and remains there, frozen in place, as the engine begins to move towards the tunnel. For this stunt Buster only had to sit very still, but as with the Steamboat Bill stunt, it also required nerves of steel.

“I was running the engine myself all through the picture. I could handle that thing so well I was stopping it on a dime. But when it came to the shot, I asked the engineer whether we could do it. He said “there’s only one danger. A fraction too much steam and the wheel spins, and if it spins it will kill you then and there”. We tried it four or five times and in the end the engineer was satisfied that he could handle it. So we went ahead and did it”

Our Hospitality 1923

Two stunts could have resulted in Buster’s death in Our Hospitality.

The film climaxes in a daring rescue of the heroine Virginia, whose boat is being swept downstream through the rapids. As usual, Buster had refused to use a double. As a safety precaution, wire was attached to his body and to make sure he would stay within camera range.

When the cameras started to roll, he plunged into the fierce current of the Truckee River and began to swim. A few seconds later, the wire snapped and he shot forward, tumbling over rocks and boulders, swallowing great mouthfuls of foam as he was borne toward the rapids. It took all his strength to maneuver himself to the river's edge so that he could grab an overhanging branch.

The cameraman did as was always ordered to by Buster and kept filming. When he was found ten minutes later, Buster lay in the underbrush along the riverbank facedown in the mud, his feet still dangling in the water. He did not move when they pulled him out. His first words as he lifted his head were: "Did Nate see it” Nate was Natalie Talmadge his wife and co star. She had seen it.

The footage of the accident was used in the final film.

Back in Hollywood, he completed the rescue sequence on the lot. A waterfall was constructed over the swimming pool. To create the distant valley below the falls, a miniature set was planted with hundreds of tiny trees. As Virginia's boat plunges over the falls, Willie uses a rope to swing out over the waterfall and grab her at the last moment. Although a dummy was substituted for Natalie, Buster performed the dangerous stunt himself. Hanging upside down underneath the waterfall, he swallowed so much water that a doctor was called to give him first aid.

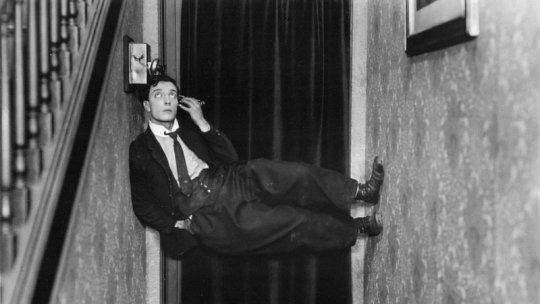

Sherlock Jr. 1924

The film critic David Thomson described Keaton's style of comedy thusly: "Buster plainly is a man inclined towards a belief in nothing but mathematics and absurdity ... like a number that has always been searching for the right equation”

Many of Buster’s stunts comprised of a perfect combination of “mathematics and absurdity” including this stunt from Sherlock Jr. which involved his holding onto an upright roadblock gate that swings down, with him jumping onto an oncoming car at the right moment. It has an almost James Bond like quality of humour and coolness about it.

Seven Chances 1925

Buster did not want to do Seven Chances. He was not happy with the script but was compelled to make it as the studio had already bought it.

At the first test screening he was disappointed by how disengaged the audience were. The only time they seemed to perk up was towards the end of the movie. He is being chased by the pack of brides and runs down the side of a hill to get away when some boulders start falling behind him. He manages to dodge them just in time.

Buster took note of this reaction and just went with it. He had papier-mâché boulders made in various sizes and created a whole new scene carrying on from that point. It is one of the most memorable moments in the whole movie.

Although the boulders were fake, due to the size of some of them if they’d hit him they would no doubt have caused some damage. Buster had to be super fast and super nimble to avoid getting hit. Fortunately he was both.

I sometimes wonder if this scene influenced the famous boulder scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Sherlock Jr. 1924

"Of course all my weight pulls on the rope, and I pull the spout down and it drenches me with water. I didn't know how strong that water pressure was. Well, it just tore my grip loose as if I had no grip at all and dropped me the minute it hit me. And I lit on my back with my head right across the rail right on my neck. It was a pretty hard fall, and that water pushed me down....I had a headache for a few hours.... I said, 'I want a drink.' I turned at the next block coming back from location-it was out there in the [San Fernando] Valley someplace. I went in to see Mildred Harris, Charlie Chaplin's first wife, and I went into her house and she gave me a couple of stiff drinks. During Prohibition, see, when you couldn't just stop anyplace to get a drink. So, that numbed me enough that I woke up the following morning, my head was clear and I never stopped working”.

-Buster Keaton

Reader, he’d broken his neck.

Three Ages 1923

“So, my scene was that with the cops chasing me, I took advantage of the lid of a skylight and laid it over the edge of the roof to use as a springboard. I backed up, hit it, and tried to make it to the other side, which was probably about eighteen feet. Well, I misjudged the spring of that board and didn’t make it. I hit flat up against the other set and fell to the net, but I hit hard enough that I jammed my knees a little bit, and hips and elbows and I had to go home and stay in bed for about three days. And, of course, at the same time, me and the scenario department were a little sick because we can’t make that leap. That throws the whole chase sequence, that routine, right out the window. So the boys the next day went into the projecting room and saw the scene anyhow, ’cause they had it printed to look at it. Well, they got a thrill out of it, so they came back and told me about it. I say ‘Well, if it looks that good let’s see if we can pick it up this way: The best thing to do is to put an awning on a window, just a little small awning, just enough to break my fall.’ ’Cause on the screen you could see that I fell about sixteen feet. I must have passed two stories. So now you go in and drop into something just to slow me up, to break my fall, and I can swing from that onto a rainspout, and when I get a hold of it, it breaks and lets me sway out away from the building hanging onto it. And for a finish, it collapses enough that it hinges and throws me down through a window a couple of floors below. Well, when this pipe broke and threw me through the window, we went in there and built the sleeping quarters of the fire department with a sliding pole in the background. Well, it ended up…It was the biggest laughing sequence in the picture…because I missed it in the original trick.”

#buster keaton#silent movies#comedy#1920s#silent film#silent comedy#1920s cinema#golden age of hollywood#hollywood#slapstick#stunts#stuntman#stunt master#sherlock jr#cops#cops 1922#the navigator#Sherlock Jr.#silent era#silent movie stars#three ages#seven chances#our hospitality#natalie talmadge

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buster Keaton with his tie mustache disguise (and Virginia Fox) Cops (1922) & Hard Luck (1921)

#buster keaton#1920s#1920s hollywood#silent film#silent comedy#silent cinema#silent era#silent movies#pre code#pre code hollywood#pre code film#pre code era#pre code movies#damfino#damfinos#vintage hollywood#black and white#buster edit#slapstick#old hollywood#virginia fox#cops#hard luck#1921#1922

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cops, 1922

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nabat" anarchists in prison, 1922 - photo found in the archives of the Security Service of Ukraine in Kyiv.

via Philip Ruff

#nabat#anarchism#anarchist#prison#1922#history#ukraine#kyiv#kyiv ukraine#161#1312#class war#anti capitalism#antinazi#anti colonialism#anti cop#anti colonization#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#incarceration#incarcerated people#incarcerated women#antifascist#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

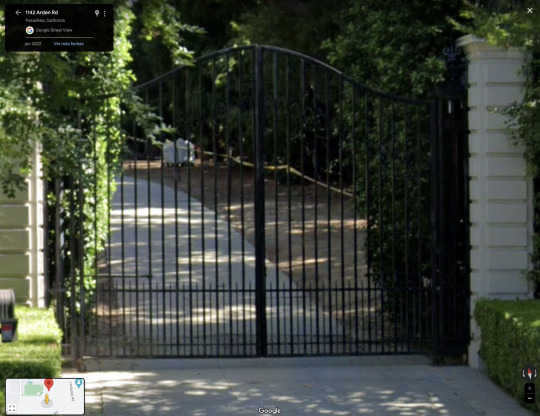

Cops Edward F. Cline, Buster Keaton. 1922

Mansion gate 1145 Arden Rd, Pasadena, CA 91106, USA See in map

See in imdb

#edward f. cline#buster keaton#cops#virginia fox#gate#madison heights#pasadena#california#united states#movie#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#silent cinema#1922

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Film I Watch In 2023:

87. Cops (1922) -- a rewatch

#cops#buster keaton#cops (1922)#2023filmgifs#my gifs#totally made my Murrican rellos watch a Keaton#cos they asked who was on my tee#and had never heard of him

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Buster Keaton & Eddie Cline’s “Cops” March 11, 1922.

#Buster Keaton#Eddie Cline#Edward F. Cline#Cops#Cops (1922)#1922#Twenties#Silent Film#Comedy#Short Film#3/5

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 10th National Umbrella Day casts a little shade on February 10th. The day honors one of the world's most useful inventions, the umbrella!

#national umbrella day#february 10th#charlie chaplin#“pay day”#1922#belgian postcard#circa 1934#“between showers”#1914#ford sterling#chester conklin#keystone cop

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

COPS! (1922) dir. Edward F. Cline & Buster Keaton THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 (2014) dir. Marc Webb

#angelslatte#filmedit#copsedit#spidermanedit#marveledit#tasm2edit#gifs**#misc parallels#spiderman parallels#cops!#the amazing spider-man 2#the young man#buster keaton#edward f. cline#spider-man#peter parker#andrew garfield#marc webb#marvel

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Buster Keaton's brilliant solo comedy shorts on Criterion Channel and free on Kanopy

Buster Keaton was arguably the cinema’s first modernist: an old fashioned romantic with a 20th century mind behind the deadpan visage. His films brim with some of the most breathtaking stunts and ingenious gags ever put on film, all perfectly engineered to look effortless. It all began with his first solo flights: 19 short films that he made between 1920 and 1923. Though he did not take director…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

121 Words & Phrases for Dying

A remarkable creativity surrounds the vocabulary of death. The words and expressions range from the solemn and dignified to the jocular and mischievous.

Old English

swelt/forswelt ⚜ give up the ghost ⚜ dead ⚜ i-wite

wend ⚜ forworth ⚜ go out of this world ⚜ quele ⚜ starve

c.1135 — 1600s

die (c.1135) ⚜ fare (c.1175) ⚜ end; let; shed (one’s own) blood (c.1200)

yield (up) the ghost (c.1290) ⚜ take the way of death (1297)

die up; fall; fine; leave; spill; tine (c.1300)

leese one’s life-days (c.1325) ⚜ part (c.1330)

flit (c.1340) ⚜ trance; pass (1340) ⚜ determine (c.1374)

disperish (c.1382) ⚜ be gathered to one’s fathers (1382)

miscarry (c.1387) ⚜ go; shut (1390)

expire; flee; pass away; seek out of life; sye; trespass (c.1400)

decease (1439) ⚜ ungo (c.1450) ⚜ have the death (1488)

vade (1495) ⚜ depart (1501) ⚜ pay one’s debt to nature (c.1513)

galp (1529) ⚜ go west (c.1532) ⚜ pick over the perch (1532)

die the death (1535) change one’s life; jet (1546)

play tapple up tail (1573) ⚜ inlaik (1575) ⚜ finish (1578) ⚜ relent (1587)

unbreathe (1589) ⚜ transpass (1592) ⚜ lose one’s breath (1596)

go off (1605) ⚜ make a die (of it) (1611) ⚜ fail (1613)

go home (1618) ⚜ drop (1654) ⚜ knock off (c.1657) ⚜ ghost (1666)

go over to the majority (1687) ⚜ march off (1693)

bite the ground/sand/dust; die off; pike (1697)

1700s — 1960s

pass to one’s reward (1703) ⚜ sink; vent (1718) ⚜ demise (1727)

slip one’s cable (1751) ⚜ turf (1763) ⚜ move off (1764)

kick the bucket (1785) pass on (1805) exit (1806)

launch into eternity (1812) ⚜ go to glory (1814) ⚜ sough (1816)

hand in one’s accounts (1817) ⚜ croak (1819)

slip one’s breath (1819) ⚜ stiffen (1820) ⚜ buy it (1825)

drop short (1826) ⚜ fall a sacrifice to (1839)

go off the hooks (1840) ⚜ succumb (1849) ⚜ step out (1851)

walk (forth) (1858) ⚜ snuff out (1864) ⚜ go/be up the flume (1865)

pass out (c.1867) ⚜ cash in one’s checks (1869) ⚜ peg out (1870)

go bung (1882) ⚜ get one’s call (1884) ⚜ perch (1886) ⚜ off it (1890)

knock over (1892) ⚜ pass in (1904) ⚜ the silver cord is loosed (1911)

pip (out) (1913) ⚜ cop it (1915) ⚜ stop one (1916) ⚜ conk (out) (1918)

cross over (1920) ⚜ kick off (1921) ⚜ shuffle off (1922)

pack up (1925) ⚜ step off (1926) ⚜ take the ferry (1928)

meet one’s Maker (1933) ⚜ kiss off (1945)

have had it (1952) ⚜ crease it (1959) ⚜ zonk (1968)

The list displays a remarkable inventiveness, as people struggle to find fresh forms of expression.

The language of death is inevitably euphemistic, but few of the verbs or idioms shown here are elaborate or opaque.

In fact the history of verbs for dying displays a remarkable simplicity: 86 of the 121 entries (over 70%) consist of only one syllable, and monosyllables figure largely in the multi-word entries (such as pay one’s debt to nature).

Only 16 verbs are disyllabic, and only 3 are trisyllabic (determine, disperish, miscarry), loanwords from French, and along with expire, trespass, and decease showing the arrival of a more scholarly vocabulary in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Even the euphemisms of later centuries have a markedly monosyllabic character.

Some constructions evidently have permanent appeal because of their succinct and enigmatic character, such as the popularity of ‘____ it’ (whatever the ‘it’ is): snuff it, peg it, buy it, cop it, off it, crease it, have had it.

It’s possible to see changes in fashion, such as the vogue for colloquial usages in "off" in the middle of the 18th century (move off, pop off, pack off, hop off ).

And styles change: we no longer feel that "pass out" would be appropriate on a tombstone. But some things don’t change. Pass away has been with us since the 14th century. And, in a usage that dates back to the 12th, we still do say that people, simply, died.

Source ⚜ More: Word Lists ⚜ Notes & References ⚜ Historical Thesaurus

#writing reference#writeblr#dark academia#spilled ink#langblr#literature#writers on tumblr#linguistics#writing prompt#poets on tumblr#poetry#writing prompts#language#words#creative writing#writing inspiration#writing resources

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

#buster keaton#silent movies#cops 1922#the high sign 1920#the haunted house#my wife’s relations#hats#hang up your hat#comedy#1920s#silent film#silent comedy#1920s cinema#golden age of hollywood#hollywood#slapstick

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buster Keaton Cops (1922)

#buster keaton#1930s#1910s#1920s#1920s hollywood#silent film#silent comedy#silent cinema#silent era#silent movies#pre code#pre code hollywood#pre code film#pre code era#pre code movies#damfino#damfinos#vintage hollywood#black and white#buster edit#slapstick#old hollywood#cops#1922

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

My alternate universe fantasy colonial Hong Kong is more authoritarian and just as racist but less homophobic than in real life, should I change that?

@floatyhands asked:

I’m a Hongkonger working on a magical alternate universe dystopia set in what is basically British colonial Hong Kong in the late 1920s. My main character is a young upper middle-class Eurasian bisexual man. I plan to keep the colony’s historical racial hierarchy in this universe, but I also want the fantasy quirks to mean that unlike in real life history, homosexuality was either recently decriminalized, or that the laws are barely enforced, because my boy deserves a break. Still, the institutions are quite homophobic, and this relative tolerance might not last. Meanwhile, due to other divergences (e.g. eldritch horrors, also the government’s even worse mishandling of the 1922 Seamen's Strike and the 1925 Canton-Hong Kong Strike), the colonial administration is a lot more authoritarian than it was in real history. This growing authoritarianism is not exclusive to the colony, and is part of a larger global trend in this universe. I realize these worldbuilding decisions above may whitewash colonialism, or come off as choosing to ignore one colonial oppression in favor of exaggerating another. Is there any advice as to how I can address this issue? (Maybe I could have my character get away by bribing the cops, though institutional corruption is more associated with the 1960s?) Thank you!

Historical Precedent for Imperialistic Gay Rights

There is a recently-published book about this topic that might actually interest you: Racism And The Making of Gay Rights by Laurie Marhoefer (note: I have yet to read it, it’s on my list). It essentially describes how the modern gay rights movement was built from colonialism and imperialism.

The book covers Magnus Hirschfeld, a German sexologist in the early 1900s, and (one of) his lover(s), Li Shiu Tong, who he met in British Shanghai. Magnus is generally considered to have laid the groundwork for a lot of gay rights, and his research via the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was a target of Nazi book-burnings, but he was working with imperial governments in an era where the British Empire was still everywhere.

Considering they both ended up speaking to multiple world leaders about natural human sexual variation both in terms of intersex issues and sexual attraction, your time period really isn’t that far off for people beginning to be slightly more open-minded—while also being deeply imperialist in other ways.

The thing about this particular time period is homosexuality as we know it was recently coming into play, starting with the trial of Oscar Wilde and the rise of Nazism. But between those two is a pretty wildly fluctuating gap of attitudes.

Oscar Wilde’s trial is generally considered the period where gay people, specifically men who loved men, started becoming a group to be disliked for disrupting social order. It was very public, very scandalous, and his fall from grace is one of the things that drove so many gay and/or queer men underground. It also helped produce some of the extremely queercoded classical literature of the Victorian and Edwardian eras (ex: Dracula), because so many writers were exploring what it meant to be seen as such negative forces. A lot of people hated Oscar Wilde for bringing the concept to such a public discussion point, when being discreet had been so important.

But come the 1920s, people were beginning to wonder if being gay was that bad, and Mangus Hirschfeld managed to do a world tour of speaking come the 1930s, before all of that was derailed by wwii. He (and/or Li Shiu Tong) were writing papers that were getting published and sent to various health departments about how being gay wasn’t an illness, and more just an “alternative” way of loving others.

This was also the era of Boston Marriages where wealthy single women lived together as partners (I’m sure there’s an mlm-equivalent but I cannot remember or find it). People were a lot less likely to care if you kept things discreet, so there might be less day to day homophobia than one would expect. Romantic friendships were everywhere, and were considered the ideal—the amount of affection you could express to your same-sex best friend was far above what is socially tolerable now.

Kaz Rowe has a lot of videos with cited bibliographies about various queer disasters [affectionate] of the late 1800s/early 1900s, not to mention a lot of other cultural oddities of the Victorian era (and how many of those attitudes have carried into modern day) so you can start to get the proper terms to look it up for yourself.

I know there’s a certain… mistrust of specifically queer media analysts on YouTube in the current. Well. Plagiarism/fact-creation scandal (if you don’t know about the fact-creation, check out Todd in the Shadows). I recommend Kaz because they have citations on screen and in the description that aren’t whole-cloth ripped off from wikipedia’s citation list (they’ve also been published via Getty Publications, a museum press).

For audio-preferring people (hi), a video is more accessible than text, and sometimes the exposure to stuff that’s able to pull exact terms can finally get you the resources you need. If text is more accessible, just jump to the description box/transcript and have fun. Consider them and their work a starting place, not a professor.

There is always a vulnerability in learning things, because we can never outrun our own confirmation bias and we always have limited time to chase down facts and sources—we can only do our best and be open to finding facts that disprove what we researched prior.

Colonialism’s Popularity Problem

Something about colonialism that I’ve rarely discussed is how some colonial empires actually “allow” certain types of “deviance” if that deviance will temporarily serve its ends. Namely, when colonialism needs to expand its territory, either from landing in a new area or having recently messed up and needing to re-charm the population.

By that I mean: if a fascist group is struggling to maintain popularity, it will often conditionally open its doors to all walks of life in order to capture a greater market. It will also pay its spokespeople for the privilege of serving their ends, often very well. Authoritarians know the power of having the token supporter from a marginalized group on payroll: it both opens you up directly to that person’s identity, and sways the moderates towards going “well they allow [person/group] so they can’t be that bad, and I prefer them.”

Like it or not, any marginalized group can have its fascist members, sometimes even masquerading as the progressives. Being marginalized does not automatically equate to not wanting fascism, because people tend to want fascist leaders they agree with instead of democracy and coalition building. People can also think that certain people are exaggerating the horrors of colonialism, because it doesn’t happen to good people, and look, they accept their friends who are good people, so they’re fine.

A dominant fascist group can absolutely use this to their advantage in order to gain more foot soldiers, which then increases their raw numbers, which puts them in enough power they can stop caring about opening their ranks, and only then do they turn on their “deviant” members. By the time they turn, it’s usually too late, and there’s often a lot of feelings of betrayal because the spokesperson (and those who liked them) thought they were accepted, instead of just used.

You said it yourself that this colonial government is even stricter than the historical equivalent—which could mean it needs some sort of leverage to maintain its popularity. “Allowing” gay people to be some variation of themselves would be an ideal solution to this, but it would come with a bunch of conditions. What those conditions are I couldn’t tell you—that’s for your own imagination, based off what this group’s ideal is, but some suggestions are “follow the traditional dating/friendship norms”, “have their own gender identity slightly to the left of the cis ideal”, and/or “pretend to never actually be dating but everyone knows and pretends to not care so long as they don’t out themselves”—that would signal to the reader that this is deeply conditional and about to all come apart.

It would, however, mean your poor boy is less likely to get a break, because he would be policed to be the “acceptable kind of gay” that the colonial government is currently tolerating (not unlike the way the States claims to support white cis same-sex couples in the suburbs but not bipoc queer-trans people in polycules). It also provides a more salient angle for this colonial government to come crashing down, if that’s the way this narrative goes.

Colonial governments are often looking for scapegoats; if gay people aren’t the current one, then they’d be offered a lot more freedom just to improve the public image of those in power. You have the opportunity to have the strikers be the current scapegoats, which would take the heat off many other groups—including those hit by homophobia.

In Conclusion

Personally, I’d take a more “gays for Trump” attitude about the colonialism and their apparent “lack” of homophobia—they’re just trying to regain popularity after mishandling a major scandal, and the gay people will be on the outs soon enough.

You could also take the more nuanced approach and see how imperialism shaped modern gay rights and just fast-track that in your time period, to give it the right flavour of imperialism. A lot of BIPOC lgbtqa+ people will tell you the modern gay rights movement is assimilationalist, colonialist, and other flavours of ick, so that angle is viable.

You can also make something that looks more accepting to the modern eye by leaning heavily on romantic friendships that encouraged people waxing poetic for their “best friends”, keeping the “lovers” part deeply on the down low, but is still restrictive and people just don’t talk about it in public unless it’s in euphemisms or among other same-sex-attracted people because there’s nothing wrong with loving your best friend, you just can’t go off and claim you’re a couple like a heterosexual couple is.

Either way, you’re not sanitizing colonialism inherently by having there be less modern-recognized homophobia in this deeply authoritarian setting. You just need to add some guard rails on it so that, sure, your character might be fine if he behaves, but there are still “deviants” that the government will not accept.

Because that’s, in the end, one of the core tenants that makes a government colonial: its acceptance of groups is frequently based on how closely you follow the rules and police others for not following them, and anyone who isn’t their ideal person will be on the outs eventually. But that doesn’t mean they can’t have a facade of pretending those rules are totally going to include people who are to the left of those ideals, if those people fit in every other ideal, or you’re safe only if you keep it quiet.

~ Leigh

#colonialism#colonization#worldbuilding#alternate history#history#lgbt#china#hong kong#british empire#ask

590 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edna May Oliver (Alice in Wonderland; Murder on a Honeymoon)— we're so back it's her time to shine shes scrungly to me for her snark and unique face. i called her the womens equivalent of the weird little guy when i submitted her for the main tournament and i was so right to say that. she used it to her advantage in her comedic performances, though her comments on her looks often came across as self defacing, commenting for example that despite her musical talents she never pursued theatre or opera primarily because "[with a horse face like mine] what else can i do but play comedy" well i just think shes swell is the thing! her performances as hildegarde withers give scrungle to me not due to appearance or weirdguy swag or the standard scrungly vibes i think most people judge characters by, but from the characters delicate balancing act between "NOT made for an investigative career" and "extremely fucking good at noticing details and therefore being SUITED for investigation"

Max Schreck (Nosferatu)—He played Count friggin' Orlok in Nosferatu (the 1922 unlicensed adaptation of Dracula)! One of the most iconically scrungly performances in cinema history, with his ratlike face, claw-like hands, and jerky, stilted body language, Schreck was so convincing that people speculated he really was a vampire, a theory that was later adapted into 2000's Shadow of the Vampire feat. modern scrungly actor Willem Dafoe as vampire!Schreck. Schreck was scrungly in other movies, too, e.g. as The Sinister Conspirator in The Finances of the Grand Duke, but Orlok is by far his most significant, well-known and easily-viewable performance, and it's such a landmark that that alone should be enough to place him as one of the top-ranked scrungly actors of all time.

This is round 2 of the contest. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. If you're confused on what a scrungle is, or any of the rules of the contest, click here.

[additional submitted propaganda + scrungly videos under the cut]

Edna May Oliver:

This woman's energy in literally all of her films is INSANE. Yeah she loves fiercely but boy is she also ready to kill. In A Tale of Two Cities (1935) she literally fights a woman to the death. She also played a female sleuth in the 1930s which I think is pretty fucking neat :)

youtube

EDNA MY LOVE. a character actress extraordinaire and iconic female weird little guy (actually she was tall and spindly but weird little guy is a state of mind yn). she was frequently found in 30s and 40s movies playing a spinter aunt or something of that ilk, who was not about to take anybody's nonsense and had cutting retorts to spare. she also starred in a series of murder mysteries in which she is a DELIGHT as schoolteacher turned amateur detective hildegard withers, who waltzes in does the cops' jobs better than them and wears some really great hats. she pops up a lot in adaptations of classic literature, playing lady catherine de bourgh in pride and prejudice, the nurse in romeo and juliet, the red queen in the 1933 alice in wonderland which has an insane cast loaded with vintage scrunglers, aunt trotwood in david copperfield and others, but she was equally at home in modern comedies. whoever she was playing you know she probably had some hard truths and/or sharp witticisms to drop on everybody around her with her distinctive vocal delivery, or just volumes to speak with her terrifically expressive face.

youtube

Max Schreck:

Most scrungly onscreen vampire has gotta be Count Orlock, (and the second is Willem Dafoe playing Max Shreck playing Count Orlock, so technically he takes up both the top spots)

Bizarre, fun, can’t look away - Literally blinks once

youtube

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buster Keaton

Born Joseph Francis Keaton on October 4, 1895, was an American director and actor who became famous for various comedy scenes that are still repeated in films today. You may recognize him from the nickname "the man with the stone face". He is known as a director, screenwriter and actor in famous silent comedies such as "The General" and "The Navigator".

Keaton was born into a vaudeville family in Piqua, Kansas. His name Joseph didn't come out of nowhere, it was a family tradition from his father's side. The nickname Buster was invented by Harry Houdini (a friend of his parents) when little Buster fell down the stairs and instead of crying or reacting in any way, he got up and moved on (The nickname was also a reference to the fact that he often caused trouble as a child). At the age of three, Keaton began performing with his parents in The Three Keatons. He first appeared on stage in 1899 in Wilmington, Delaware. The act was mainly a comedy sketch. Despite his run-ins with the law, Keaton was a rising and relatively well-paid theater star. He stated that he learned to read and write late and was taught by his mother. When he was 21, his father's alcoholism threatened the reputation of the family actor, 20, so Keaton and his mother Myra went to New York, where Keaton's career quickly moved from vaudeville to film. Keaton served with the American Expeditionary Forces in France in the United States Army's 40th Infantry Division during World War I. His unit remained intact and was not broken up to provide replacements, as had been the case with some other late-arriving divisions. While in uniform, he contracted an ear infection that permanently damaged his hearing. Keaton was such a natural in his first film, "Butcher Boy," that he was hired on the spot. Finally, he asked to borrow one of the cameras to see how it worked. He took the camera back to his hotel room, where he disassembled and reassembled it by morning. He appeared in a total of 14 Arbuckle shorts, running into 1920. They were popular, and contrary to Keaton's later reputation as "The Great Stone Face", he often smiled and even laughed in them. In 1920, The Saphead was released, marking Keaton's first starring role in a feature-length feature film. After Keaton's successful collaboration with Arbuckle, Schenck gave him his own production unit, Buster Keaton Productions. He made a series of 19 two-reel comedies, including One Week (1920), The Playhouse (1921), Cops (1922), and The Electric House (1922).

The more adventurous ideas called for dangerous stunts, performed by Keaton at great physical risk. During the railroad water-tank scene in Sherlock Jr. (gags written by Clyde Bruckman), Keaton broke his neck when a torrent of water fell on him from a water tower, but he did not realize it until years afterwards. A scene from Steamboat Bill, Jr. required Keaton to stand still on a particular spot. Then, the facade of a two-story building toppled forward on top of Keaton. Keaton's character emerged unscathed, due to a single open window. The stunt required precision, because the prop house weighed two tons, and the window only offered a few inches of clearance around Keaton's body. The sequence furnished one of the most memorable images of his career. Aside from Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), Keaton's most enduring feature-length films include Three Ages (1923), Our Hospitality (1923), The Navigator (1924), Sherlock Jr. (1924), Seven Chances (1925), The Cameraman (1928), and The General (1926). The General, set during the American Civil War, combined physical comedy with Keaton's love of trains, including an epic locomotive chase. Employing picturesque locations, the film's storyline reenacted an actual wartime incident. Though it would come to be regarded as Keaton's greatest achievement, the film received mixed reviews at the time. It was too dramatic for some filmgoers expecting a lightweight comedy, and reviewers questioned Keaton's judgment in making a comedic film about the Civil War, even while noting it had a "few laughs." it was an expensive dud, His distributor, United Artists, insisted on a production manager who monitored expenses and interfered with certain story elements. Keaton endured this treatment for two more feature films, and then exchanged his independent setup for employment at Hollywood's biggest studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Keaton's loss of independence as a filmmaker coincided with the coming of sound films (although he was interested in making the transition) and mounting personal problems, and his career in the early sound era was hurt as a result.

I guess that's it for Buster's success.

Keaton died of lung cancer on February 1, 1966, aged 70, in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles. Despite being diagnosed with cancer in January 1966, he was never told he was terminally ill. Keaton thought that he was recovering from a severe case of bronchitis. Confined to a hospital during his final days, Keaton was restless and paced the room endlessly, desiring to return home. In a British television documentary about his career, his widow Eleanor told producers from Thames Television that Keaton was up out of bed and moving around, and even played cards with friends who came to visit the day before he died. He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Hollywood Hills, California.

Keaton was presented with a 1959 Academy Honorary Award at the 32nd Academy Awards, held in April 1960. Keaton has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: 6619 Hollywood Boulevard (for motion pictures); and 6225 Hollywood Boulevard (for television).

Three Ages (1923)

Our Hospitality (1923)

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

The Navigator (1924)

Seven Chances (1925)

The Cameraman (1928)

Go West (1925)

Battling Butler (1926)

The General (1926)

College (1927)

Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928)

Spite Marriage (1929)

-¤-

67 notes

·

View notes