#conall cernach

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

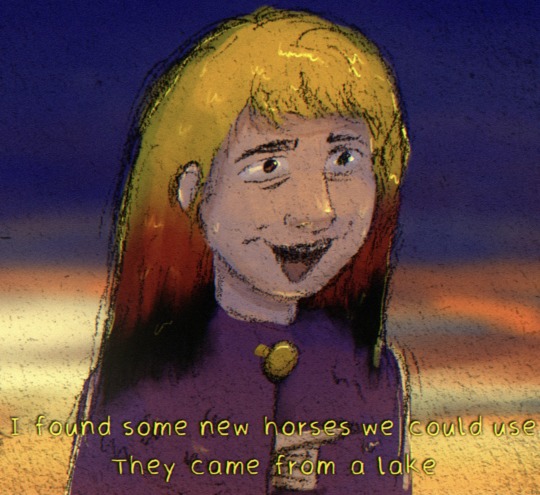

Cu Chúlainn is having a really bad day

Cu chúlainns horse are usually just described like normal horses traditionally but I decided to have fun and make it look slightly aquatic

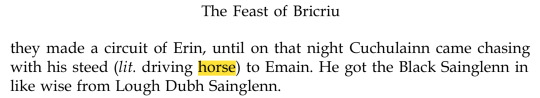

Bonus (Conall’s Horse)

um

horses aren’t supposed to have a hounds head wth sharp teeth and ave the ability to kill people

#tw blood#comic#tain bo cuailnge#irish mythology#art#cú chulainn#the tain#conall cernach#lake horse#dog headed horse#for context the lake horses are in theory normal looking roses. Conall’s gore hound horse#well the name says it all…#laeg mac riangabra#laeg#dog headed horse dripping red with gore#fergus

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Conall Cernach#Conall Cearnach#this is so dumb and niche smh#rotating him in my brain atm#Ulster Cycle

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about Conall digging Cú Chulainn's grave (and Emer's... and in a fair universe it would also be Fer Diad's and Láeg's...) and I need a Hamlet-style gravedigger soliloquy from him about—

actually, you know what, post cancelled, I just remembered a major feature of Deargruathar Chonaill Cernaigh / Laoidh na gCeann is indeed Conall talking to Cú Chulainn's head, and declaiming variously about a wide range of other heads, which would have skulls in them, because heads do, typically. We have no shortage of Conall soliloquising over dead people. That's the entire point of the text.

Having said that, it would be kind of funny to have a scene where he's bitching about how many people insisted on being buried with Cú Chulainn because it's too much digging.

#conall cernach#oidheadh con culainn#laoidh na gceann is literally 'the lay of the heads'#in my defence it is 00:25am

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

In transactions of the killkenny archaeological society volume 1-2 1853 , Eugene O kearney known forger writes that there exists a manuscript called "achievements of the seven celebrated irishman in the East under command of Royal champion Conall Kernach" he writes not about the manuscript but about an interperlation. Of the manuscript content all he says is that the interperlation occurs after Manannan mac Lir instructs Cuchulainn to use Gae Bolg crafted from a serpent that lived in Loch-na-niath near Manannans house in Armenia". It seems to be the origin for Lady Gregory mentioning it.

Do you think the manuscript exists or existed ? If nor was it just a forgery and how much damage do you think O'kearney did to irish folklore

What a profoundly interesting question! Thank you for bringing this to my attention Anon!

I generally don't deal with material after the 16th century asides from short dalliances here and there, so I had not heard of this O'Kearney before (for those curious, he appears to have used a pen name, Nicolás Ó Cernaigh, and this is the article anon is referring to).

I can't really say anything definitive (.i. beyond my vibes on the matter) in regards to the possibility if this manuscript existed or not. It is just very outside my wheelhouse. While some of the material O'Kearney puts forward in his note appears plausible based on some of the things I know about the Ulster Cycle in the 19th century (ex: the description of the gáe bolga sounds a lot like the 'stingray spear' idea that has been discussed by Edward Pettit's 'Cú Chulainn's gae bolga: from harpoon to stingray spear,' Studia Hibernica 41 (2015): 9-48) or earlier (the idea that Conall is operating outside Ireland kicks around in medieval Ireland, which I discussed in my MA thesis on the topic), it could simply be him incorporating actual folk material into his fiction to give it plausibility.

What I would say is that how he is representing buada here is pretty weird. Unless there was a significant change in how they were being imagined in the late Early Modern heroic cycles, it looks like a red flag to me. I can't think of any objects being ascribed buada, and the buada we do see are... not supernatural powers? I suppose some of them might be (the buada of seeing in TBDD for instance is pushing it), but a lot of them are just 'this person ROCKS at this thing'. It looks like he is interpreting it as a word like 'enchantment' or something, which is not what I would be used to with the medieval material. However, it is very possible for terms like this to experience shifts. If you are in the International Celtic Congress this year, you will hear me talk about clessa and how they change over time in the tradition.

Further, again, I am a medievalist so maybe this isn't as odd to a late early modernist, but this interpolation being in Latin seems super weird?

[A further detail, @irelandseyeonmythology just noted to me that it looks like there's a very basic translation issue. The title of the manuscript, according to this gentleman, was 'an t-oc(h)tar Gaedil', and somehow took that to mean seven and not eight. They similarly noted that the use of Latin seems really odd for the period.]

This sort of thing is, of course, the problem with forgers and other forms of academic dishonesty. The moment someone dabbles in it, every piece of their work is now under extreme scrutiny and can't receive the benefit of the doubt. While, personally, I would love for there to be an entire manuscript about Conall (though I would find it strange for there to be a single-text manuscript, unless that was a popular thing in the late Early Modern Irish period or something?), I would have to say that we should assume that this is a fiction. Especially as he (seems to?) be trying to use the interpolation as part of a defense against accusations that he was making things up.

I am, of course, not a folklorist. I'm a medievalist. So, I can't really say anything in regards to the damage he has done to Irish folklore. I would leave any true judgement to an actual folklorist, rather than myself who has no qualifications to make such a call. However, if my wholly unqualified opinion on this is of interest, based on my experience, there's a long list of people I would put ahead of him.

[Again, a further detail, @irelandseyeonmythology noted that it looks like this idea didn't have much traction, as there is only one reference to this article, found in vol. 15-16 of The Modern Language Review (p. 78)]

Anyways, all of that aside, thank you for asking me about this! What a lovely way to conclude my weekend. This was really interesting!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanservant: Conall Cernach (Rider)

(Art by me, I liked this sketch so much it motivated me to finish this profile)

Conall Cernach

Class: Rider

True Name: Conall Cernach

Gender: Male

Source: Irish Mythology (Ulster Cycle)

Region: Ireland (Ulster)

Alignment: Chaotic Good

Height: 6’3ft/182.88cm

Weight : 212lbs/96.16kg

Parameters

Strength: B

Endurance: A

Agility: C

Mana: C

Noble Phantasm: B

Luck: E

Class Skills

Riding B

While skilled from fighting in a chariot as a warrior of the Red Branch was expected to be. However, he is at his best whenever he is riding with only his most famous steed, the monstrous Derg Drúchtach.

Magic Resistance D

Magic Resistance that cancels single action skills. Conall is not particularly experienced in regards to magic, so his rank in Magic Resistance is not particularly high.

Personal Skills

Battle Continuation A

A skill based entirely around survival. Even when one receives deadly injuries, they may continue to fight on so long as they do not receive a decisive fatal blow. No matter how severely injured, Conall Cernach will continue to fight on.

There is a slight difference between Conall’s “Battle Continuation A” and the same-ranked skill possessed by his cousin -- Cu Chulainn. If Cu Chulainn’s Battle Continuation represents “Never giving up no matter what”, Conall’s simply represents a man blessed with overwhelming toughness.

Bravery B

Gives one the ability to negate any type of mental interference, as well as increase one’s melee damage. A simple, but effective skill.

Headhunter A+

One of the most pervasive aspects of Conall Cernach was his claiming of the heads of his enemies. This penchant has been engraved into Conall Cernarch’s legend, manifesting as a skill that decreases the defenses surrounding an enemy servant’s neck when faced with Conall Cernarch.

Noble Phantasms

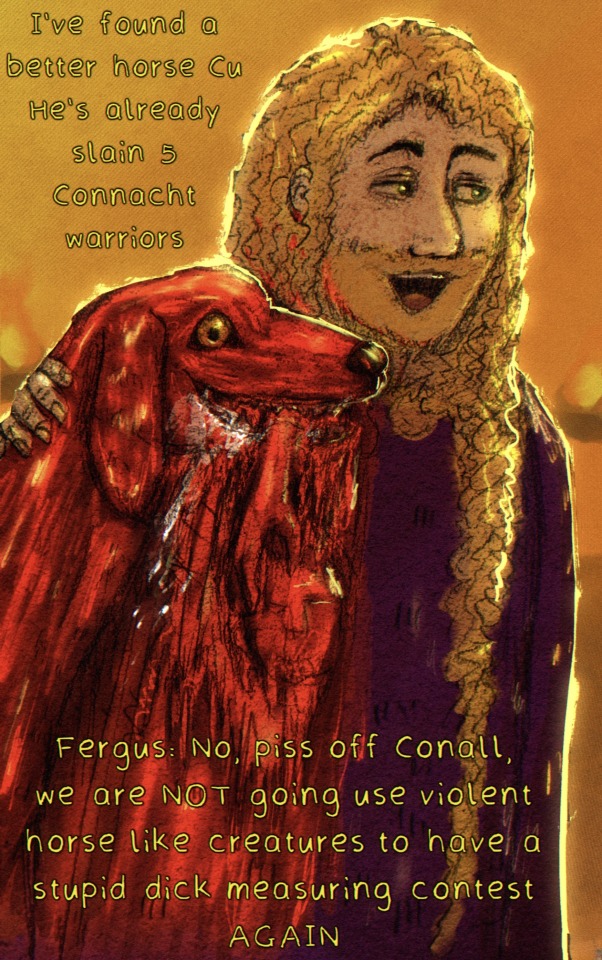

Derg Drúchtach: Bloody Hound of SidheRank: B+

Classification: Anti-Unit

The dog-headed horse of Conall Cernarch. Its name means “Dripping Red”, likely a tribute to the gore it would frequently end up covered in. It ran fast enough that the debris it kicked up appeared to be a flock of ravens, and drooled so ferociously that when it ran it looked like a snowstorm followed Derg Drúchtach. In battle, Derg Drúchtach would viciously maul Conall’s opponents and aid his rider, acting as one being at times.

By revealing Derg Drúchtach’s true name, Conall imbues another ability into his mount: the ability to [consume] opponents. While Derg Drúchtach is no stranger to biting or mauling opponents, [consuming] an opponent will lead to Conall gaining the abilities of whatever Derg Drúchtach consumed. If Derg Drúchtach is killed, Conall will lose the abilities he gained from Derg Drúchtach’s [consumptions].

Derg Geis: Oh Brother, Vengeance Shall be Mine

Rank: A

Classification: Anti-Army

The promise made by Conall Cernarch and Cu Chulainn to avenge each other if one died. It ended up being Conall Cernarch who had to fulfill that promise. Fueled by duty and rage at the passing of his cousin alike, Conall rampaged through Ireland, killing every man involved in the conspiracy to kill Cu Chulainn (only its organizer, Medb, was spared his wrath) -- taking the head of each and every one. By the time the sun set on that day, Conall had killed thousands.

A Noble Phantasm made by swearing a promise with another being - they can be human or servant. Thus, the Noble Phantasm is activated, and its power is technically bestowed onto both parties. When one party in the promise dies, the other is granted the power to [avenge them]. An adaptive ability that allows someone to track down the killer of whoever the other person who swore the promise was, and gain abilities best suited to killing them. The avenging party also gains an EX ranked [Battle Continuation] skill until their promise is completed. The longer the promise goes without being fulfilled, the more ranks in [Mad Enhancement] will slowly be gained, until the user of [Derg Geis] becomes little more than a beast focused slowly on vengeance.

Personality

Shockingly businesslike. While somewhat flippant in attitude and manner of speech, Conall is at his core a “professional”. He approaches situations with his own talents driving his thought process and his objective driving his decisions. In spite of his professional demeanor, his sense of timing is horrid and he has a tendency to be late when it matters the most.

A trait he did not have in life but possesses now as a servant is a violent aversion to not keeping track of your allies, and a cautious hesitation to allow allies to go into situations alone.

For all his attempts at professionalism, Conall loves a good brawl just as much as his cousin, and is prone to losing himself in the thrill of a fight.

Motive and Attitude towards Master

Fitting with his professional personality, Conall is courteous and loyal to his master, willing to follow any orders as they come without much complaint. In spite of his obedient nature in regards to masters, he’ll still maintain his casual speech pattern and will not wait to be asked for advice before making his thoughts on how things should proceed to be known.

Conall admits that his wish is a foolish one. He wants to make a wish on behalf of a person who he knows well enough to know doesn’t care. But even so, Conall wishes that his chariot would have been just a bit faster that day, that he could have climbed that hill earlier. That just once, he had not been late when it had mattered.

Historical Depiction

The second greatest hero of the Ulster Cycle in Irish Mythology, and the last surviving member of the Knights of the Red Branch.

When he was born, the druid Cathbad (who would later go on to prophesy the short and glorious life of Conall's young cousin Cú Chulainn), prophesied that Conall would sleep every night with the head of a Connachtmen under his knee. For this prophecy, his uncle, Cet Mac Magach tried to kill the baby Conall by stamping on his neck. The attempt failed, but Conall bore a crooked neck as a reminder of Cet's actions for most of his life.

Conall Cernarch was reared alongside Setanta on the plans of Muirthemne, and, being the older of the two, left to join their uncle Conchobar in Emain Macha earlier. There, he quickly endeared himself to the Knights of the Red Branch, and rose through their ranks -- although not with the speed his cousin later would.

Conall’s life was one marred by failure.

One of his first great adventures would be carried out alongside his uncle and soon to be lifelong enemy Cet. He was set to defend the High King of Ireland Conare, but failed, although he fought valiantly and killed many of those who wished to attack Conare.

Later, Conall would stumble upon the battle between Conchobar and the sons of Uisliu over Deirdre of the Sorrows. In the confusion of the battle, Conall dove into it and ended up killing the son of Fergus who was protecting the sons of Uisliu and Deirdre. In a panic, Conall killed one of Conchobar’s sons, and hurriedly fled the scene.

It was after fleeing that Conall encountered Cu Chulainn, returning back to Emain Macha after both his training with Scathach and retrieving Emer from her father, and explained to him what happened.

Conall’s life would not entirely be one of failure. He showed outstanding performance in skirmishes against Connacht, easily fulfilling the prophecy about “sleeping every night with a Connachtman’s head under his knee”, and even upstaged his rival Cet Mac Magach at a feast turned dangerous competition between Connacht and Ulster, tossing the head of one of Cet’s comrades Anulan at him in order to counter Cet’s assertion that Conall would have surely been defeated if Anulan were there.

Eventually, Conall took to traveling, seeing the rest of the British Isles outside of Erin. During one of these travels, the conspiracy to kill Cu Chulainn was put into action. Conall, sensing something was amiss, hurried back to Ireland, and only just did not make it in time to aid Cu Chulainn in his final battle. It was at this point that Conall would enact his grand vengeance for his cousin, slaughtering his way across Erin in pursuit of everyone involved in the conspiracy. He returned the heads of his victims to Emer, and then erected a grave for Cu Chulainn and Emer.

Eventually, Conall would meet Cet Mag Macach in what would be their final battle, and Conall Cernach defeated his rival at long last.

With nothing else to do, Conall would, in a great irony, seek hospitality from Medb and Ailill of Connacht to house him in his final days. The fire for adventures had burned out in Conall, and he spent most of his days maintaining the equipment of Connachtment and entertaining the youths by telling them how he killed their fathers. Medb would eventually enlist Conall in order to kill Ailill for both his scheme to kill Fergus, and also for taking lovers aside Medb. Conall did the deed, and was promptly chased down by Connachtmen. Conall made a great last stand, killing many Connachtmen, but was eventually forced to cross a tainted river, violating his Geass, and causing him to be paralyzed until the Connachtmen could chop Conall to pieces.

Relationships

Cu Chulainn

Conall’s younger cousin and foster brother. The two are quite close friends, having made a promise to avenge the other in real life. Although Conall feels a strong sense of protectiveness towards his younger cousin, amplified by his failure to save them during their lifetimes, Conall respects Cu Chulainn as a fellow warrior and champion enough to not let it show too much.

Setanta

He has no such restraint when it comes to his cousin's younger self, openly acting like a protective older brother to the younger Irishman.

Medb

The queen who housed Conall in his final days. Conall treats Medb like a former client, respectful, but not too eager to continue interacting with her if she cannot provide him with incentive.

Bibliography

The Tain, translated by Thomas Kinsella

Early Irish Myths and Sagas, translated by Jeffery Gantz

The Wooing of Emer, translated by Kuno Myer

Cuchulainn of Muirthemne, Lady Augusta Gregory

Oxford Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, James Mackillop

Myths and Legends of the Celts, James Mackillop

Goire Conaill Chernaig i Crúachain ocus Aided Ailella ocus Conaill Chernaig, Translated by Kuno Myer, via celt.ucc.ie

The Deaths of the Sons of Usnach, translated by Eleanor HullThe Last Hero of Ulster: An Alternative to the Heroic Biography Tradition of Conall Cernarch, by Emmet Taylor

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#medieval irish#cu chulainn#conall cernach#technically there are two horses that came out of two lakes#medieval polls

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Who’s your favorite mythological hero?”

“Conall Cernach”

“Well I like Achilles and not just cause he’s strong I think he’s—“

“Conall :)”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source: The Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend by Miranda J. Green (1992)

0 notes

Text

ALSO while we're here

i like to imagine conall cernach there like "please stop playing FMK with my relatives, i canNOT keep avenging people, thanks"

"next time can you kill someone i'm not related to or in a position of responsibility towards in any way. cheers"

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paxuson Part 1: Introduction and Comparison of Cognates

A god of bidirectionality, of liminanlity, paths, doorways, travelers, wealth, shepherds, animals, and fertility. His name means "protector" and his direct linguistic cognates are Pan and Pushan.

Pan, Lord of the Wilds

Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, rustic music and impromptus, and companion of the nymphs. He is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, wooded glens, and often affiliated with sex; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring. His origin and source of worship was in Arcadia, an isolated mountainous region of the Peloponnese whose culture is . It is believed that Hermes was originally an epithet of Pan who split off early on and becomes a separate deity associated with boundaries, roads, travelers, merchants, thieves, athletes, shepherds, commerce, cunning, and messages.

Both Hermes and Pan have myths putting in them in relation to Apollon. Hermes is characterized as being nurtured by Apollon who acts as a sort of patron to the young god. Pan and Apollon had a famed music competition in the myth of Midas. Given that we have established Apollon as a cognate of Rudlos, lets keep this in mind.

Pushan by OverlySarcasticProductions

Pushan, The Far-Roaming Shepherd

God of meetings, marriages, journeys, roads, fertility, sheep, and cattle. He is called to stir sexual desire in the bride on her wedding day. He is often seen as a solar deity, although this is connected to his shepherd aspect pretty explicitly.

He was a psychopomp, conducting souls to the other world. He protects travelers from bandits and wild beasts, and protects men from being exploited by other men. He is a supportive guide, a "good" god, leading his adherents towards rich pastures and wealth. His chariot is pulled by goats.

While there are multiple versions of the tale, it is commonly said that Rudra knocks out Pushan's teeth at the Daksha yajna, although he doesn't seem to be the target of his rage.

Cernunnos, The Horned Lord

Cernunnos, A Gaulic deity, whose name is probably more accurately rendered as *Karnonos, meaning "Horned Lord". Through the Pillar of the Boatmen, the name "Cernunnos" has been used to identify the members of an iconographic cluster, consisting of depictions of an antlered god (often aged and with crossed legs) associated with torcs, ram-horned (or ram-headed) serpents, symbols of fertility, and wild beasts (especially deer).

Ceisiwr Serith has an excellent dissection of symbols and character in his Youtube video essay, Cernunnos: Looking Every Which Way. Cernunnos has been variously interpreted as a god of fertility, of the underworld, wealth and trade, and of bi-directionality. Cernunnos has been tentatively linked with Conall Cernach, a hero of medieval Irish mythology, and some later depictions of cross-legged and horned figures in medieval art.

Kurunta, The Deer Hunter

His name seems to be cognate with Hittite Kurunta. His sacred animal is the stag, although this was not exclusive to him. He is commonly depicted standing on a stag, and Hittite texts identify the god standing on the stag as the god of the countryside. In Yazilikaya, a tutelary god of nature (likely Kurunta as the god is accompanied by the antler sign) is depicted with only a crook. There are also parallels with Kurunta following behind a storm god, as seen in a sea of Mursili III and a relief from Aleppo. There are also depictions of Kurunta holding a bow and arrows, which outside of due to him being a tutelary god also connects him to hunting. The hunting aspect was also emphasized by Tudhaliya IV.

Pashupati, Shiva of the Animals

Over in India, particularly in the east, another cognate of Rudlos, The mighty Rudra, is widely known by his epithet and avatar, Pashupati, who may be related to Paxuson. The name means "Lord of the Animals". While he may be related to the pre-Indo-Aryan deity depicted on the eponymous Pashupati seal of the Indus Valley Civilization discovered in modern day Pakistan, I believe he may be a reflex, or at least influenced by, the PIE deity in question.

In the Atharvaveda, the fourth Veda and one of the later additions to Vedic literature, Rudra is described to be the lord of the bipeds and the quadrupeds, including creatures that inhabited the earth, woods, the waters, and the skies. His lordship over cattle and other beasts denoted both a benevolent and destructive role; he slew animals that incurred his wrath, but was also kind to those who propitiated him, blessing them with health and prosperity. He is also seen a tutelary deity, of the nation of Nepal in particular.

#deity worship#pagan#pagan revivalism#paganism#pie paganism#pie pantheon#pie polytheism#pie reconstructionism#pie religion#proto indo european paganism#hellenic worship#hellenic deities#hellenic polytheism#hellenic pagan#hellenic polythiest#hellenism#hellenic paganism#hellenic devotion#celtic paganism#celtic polytheism#celtic deities#celtic gods#gaulish paganism#gaulish polytheism

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

my man is SUFFERING

(to note, in the siege of Howth, the charioteer isn’t named but in bricriu’ s feast it’s Idh who is Conall charioteer

Idh may also be Láegs brother in later texts

#art#comic#irish mythology#cú chulainn#laeg mac riangabra#laeg#idh#idh the charioteer#conall#conall cernach

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Green spring: Cernunnos

CERNUNNOS

Category: Gallic mythology

When people talk about the Celtic myths, they tend to focus solely on the insular Celts – the Irish legends, the Welsh tales… And they tend to forget that there was a whole other branch of Celts – the continental Celts, of which the most famous were the Gallic Celts, the inhabitants of Gaul (aka, current France). And the Gallic tribes had their own religion and mythology, which despite having a few common points with the insular Celts, also had a lot of differences, to the point it forms a very unique Celtic mythology…

But unfortunately, a Celtic mythology of which we know barely anything. For you see, the Gallic mythology was one of the least preserved of the Celtic mythologies. No Gallic literature of any form was preserved, and no Gallic tale was kept alive in medieval times (unlike the insular Celts). Due to the many differences and uniqueness between the Gallic religion and the insular Celts, trying to reconstruct the first solely based on the second is difficult and hazardous. And the main problem is that Gaul was conquered, colonized and absorbed by the Roman Empire at quite an early age and with a terrifying success, which means that a lot of the original Gallic culture was completely erased, or syncretized with the Roman one. As a result, a good part of what we know about ancient Gaul today comes from the treaties, books and observations made by the Roman themselves – and from the well-preserved “Gallo-Roman” era, where Gaul was just another province of the Roman Empire. For older times, we can only rely on archeological proofs and evidences, to try to discover and understand what the ancient Gallic mythology was about…

Which leads us to Cernunnos, THE most famous Gallic god. He is one of those Gallic deities that are completely unique to Gaul, and do not have any equivalent among the insular Celtic myths (even though some people claim Conall Cernach of Irish legends might be a cultural cousin, it is a very light theory based on very few and non-conclusive evidence), and he is a fascinating and very popular figure, to the point he is often included among the more well-known insular Celtic gods as if he was part of them. Of course, his adoption by neo-paganism (and Wicca in particular) helped boost even further this reputation. Remember the “Horned God” of the Wicca? Well originally, this was Cernunnos. Just Cernunnos. Before the neo-pagans rose up, there was only one pagan “Horned God” or “Horned One” known by this name – and it was Cernunnos (or Carnonos) whose very name contains the Gaulish word for “horn”. Heck, due to his unique nature, people even think that he is more than just a continental specificity – people theorize and claim that Cernunnos is actually a proto-Celtic god, a god from the original, primitive Celtic pantheon before it split up in all the different tribes and people we know today.

But enough history lessons – who, or what, was Cernunnos?

Well, as I said, we actually don’t know much about him. In fact we probably know less about him than any other Gallic god… It is a very strange fact that one of the most famous deities of the Gallic pantheon is the one we actually have the less about. As I said, no Gallic or Gaulish literature about him was kept, he doesn’t have any insular Celts counterpart, and even more fascinatingly he isn’t talked about by the Romans at all, who didn’t include him in their new, re-forged Gallo-Roman pantheon. When the Romans made lists of Gallic gods and syncretized them with their own, Cernunnos was absent. Or maybe he was here, but unnamed – you see, there is a strong theory that Cernunnos was actually present in those texts, but left unnamed, because in these lists formed by the Romans, there is an unnamed god mentioned and seen by the Romans as bearing at the same times attributes related to Mercury and Dis Pater. (I invite you to check my posts about them in my “Roman gods are not Greek gods” series). And from what evidence we have, Cernunnos was a psychopomp and/or chthonic deity (Dis Pater) who was also strongly associated with wealth (Mercury). So this deity might – just might – be him. But again, we are not sure.

So if nobody seems to talk or know about him… How do we even know he exists? We know this thanks to a lot of archeological evidences that clearly state he existed in the ancient Gallic religion. One such evidence is the Pillar of the Boatmen/Pilier des Nautes/Nautae Parisiaci. This monument, a column erected by Gallo-Romans on the location of current-day Paris, is one of the most importance sources when it comes to the Gallic gods since it depicts on several lines physical representations of both Roman and Gallic gods, with their names. It is unclear if the pillar actually tried to equate the Roman and Gallic deities (as in, showing them by side to say “Hey, this deity in Gaulish is this one in Latin”) or if it actually simply listed the Gallo-Roman pantheon formed by the union of the two religions, but on it, alongside Roman gods (Jove, Castor and Pollux, Volcanus, Fortuna) and other Gallic gods (Esus, Smertrios, Tarvos Trigaranos), Cernunnos appears, his name written under the depiction of a man with stag’s antlers on his head, from which hangs two torcs.

This is actually the second main “evidence” of Cernunnos’ presence: his physical depiction on various Gallic or Gallo-Roman items. His name is also written in some Gaulish inscriptions here and there, but it is rarer (beyond the pillar above, his name was also found in three other inscriptions so far). Cernunnos’ portraits were far more widespread – for example another famous depiction of him is present on the Gundestrup cauldron, a silver cauldron on which he appears as a man with antlers, sitting, holding in his right hand a torc, and in his left hand a horned serpent. To his left is a stag with antlers similar to his, and all around them are various other figures – canine and felines beasts, some sort of bovines, as well as a human riding a dolphin. There is also between the antler a sort of tree-like motif, but it is unclear if it is supposed to be a real tree growing between his antlers, or just some standard “background ornament”.

I’m not going to list you all the apparitions of Cernunnos, but overall a pretty clear imagery of the god is formed. Cernunnos appeared as a horned man, most of the time his horns being the antlers of a stag (though in very rare cases, he has ram-horns). He is usually seen with a torc, one of the most famous Gallic ornaments – sometimes he has it around his neck, sometimes in his hand, sometimes on his antlers. He is usually seated, but in a very specific position which has been pointed out as a “yoga position”, “yogi position”, “Buddhic position”, that is to say sitting cross-legged. Sometimes Cernunnos will appear as a beardless youth, other times as a bearded man; similar, while often he is depicted with only one head, sometimes he will have two face (like the Roman Janus) or with three faces (making him similar to the figure of Lugus/Lud). Cernunnos is usually depicted surrounded by animals, though one creature in particular is often present with him – the “ram-headed snake”, a very specific creature of Gallic mythology. Cernunnos often holds a bag from which spills either coins or food.

- - - - - -

With such an imagery and just a name to go by (which itself merely means “horned one” or “horned god”), we can only speculate and theorize about who Cernunnos was.

Here are the main points so far: Cernunnos seems to have been a god of nature. His half-human half-animal nature, coupled with the fact he is usually depicted by various beasts of different species, make people think that he is a manifestation of an ancient religious motif and archetype, the “Lord of the Animals” or “Lord of the Wild Things”, a figure usually seen sitting peacefully among wild animals, or holding by the horns two savage beasts on each side. On top of being a god of nature and animals, the fact he is usually seen holding a bag of coins or a bag of food (or is in the presence of a woman figure holding a basket filled with food, and more rarely he is even vomiting coins onto the world) also identifies him as some sort of god of wealth and/or abundance – which does explain why he appeared on the “Pilier des nautes”, which was a pillar tied to merchant-sailors and fluvial commerce (hence its name, “Boatmen Pillar”). In fact, it is pretty clear that Cernunnos seems to have embodied the two sides of “fertility”, on one side the natural abundance of the natural world of beasts and fruits, on the other side the material wealth one had to gain in a more urban and Romanized world.

Though his presence on the Boatmen Pillar also led some people to flat out interpret him as a god of travel and commerce, rather than just wealth itself (again, in Gaul, travel by the various rivers of France was the main way of doing commerce, and so most boat-travels were about selling or buying something). A fun fact is how people can sometimes have two completely opposite interpretations of him: for example, while some experts and future neo-pagans interpreted him as a form of aggressive, wild, dominating, genetic power of vigor and fecundity, other people rather point out that he seems to be a peaceful entity and “quiet” god, sitting cross-legged among animals and offering gifts – even going as far as to say that his half-human half-animal nature might mean he was a god of meditation, or a mediator/negotiating figure, trying to unite both sides of the world – a more peaceful idea of the “god of fruitfulness”, that brings fruits through union rather than an “aggressive vigor”.

Some people also argue that Cernunnos might have been a seasonal god of the Celts – for the antlers typically fall during winter and grow back during hotter seasons. The Celts considered there was only two seasons a year, one bright, one dark – summer and winter. And the fact Cernunnos is a nature-god of abundance, depicted with usually giant or massive antlers seem to indicate he might be an embodiment of the “bright season”/Celtic summer. Though other point out that there are similar or alternate depictions of Cernunnos, but with smaller protuberance on his head (or figures seated and dressed like him, but missing antlers), and they theorize that maybe Cernunnos, just like the real stags, also lost his antlers yearly before they regrew, and thus interpret him as a god embodying the very Gallic seasonal cycle, rather than just one season.

Oh yes, and there is one last theory about Cernunnos identity… You see, when Julius Caesar described the religion of Gaul, he mentioned that the Gaul people considered a specific god as their father and ancestor – and he called this deity by the Roman name of “Dis Pater”, a Roman god equated with Pluto, and considered to be an underworld deity of wealth. This led some people to theorize that Cernunnos might be the Gallic Dis Pater Caesar talked about – pointing out his association with wealth, and the fact that he wears some of the most iconic pieces of outfit worn by the Gaul people themselves (mainly the torc, and the breeches). As such, some wonders if Cernunnos wasn’t the “father-god” of the people of Gaul, worshiped as the common ancestor of all…

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking ahead to my next conference paper, which is in about three weeks... any good Conall Cernach art out there?

(When I finally finish my OCC translation, I think I will celebrate by commissioning some art of a few scenes from it, because they are tragically under-illustrated.)

#conall cernach#ulster cycle#medieval irish#irish mythology#conall cearnach#in case the glide vowels make a difference to tag reach

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! When researching Conall I read some description of him (can't remember what or where) where they described his one black eye as being completely black (as in, the iris and the sclera are both black), but in all other descriptions (mainly thinking of Da Derga's Hostel, the retelling of Conall's death by Candlelit tales pod, and the Championship of Ulster) where he is described with one black and one blue eye (just the iris I assume?). What are your thoughts on the completely black sclera?

(I'm sorry if this post is a bit stifled or weird, I had a few reflexive Ctl-Z's that have had me rewriting chunks of this post several times) Heya!

As far as I am aware, that description of Conall is only found in that portion of Togail Bruidne Da Derga (which, for those unfamiliar, I provide an excerpt from Stoke's translation) that you mention. ‘There I beheld in a decorated room the fairest man of Erin's heroes. He wore a tufted purple cloak. White as snow was one of his cheeks, the other was red and speckled like foxglove. Blue as hyacinth was one of his eyes, dark as a stag-beetle's back was the other. The bushy head of fair golden hair upon him was as large as a reaping-basket, and it touches the edge of his haunches. It is as curly as a ram's head. If a sackful of red-shelled nuts were spilt on the crown of his head, not one of them would fall on the floor, but remain on the hooks and plaits and swordlets of that hair. A gold hilted sword in his hand; a blood-red shield which has been speckled with rivets of white bronze between plates of gold. A long, heavy, three-ridged spear: as thick as an outer yoke is the shaft that is in it. Liken thou that, O Fer rogain!’

Now, this is a very interesting description. What stands out to me is the description of his curly hair catching nuts, which is obviously connected to descriptions elsewhere of warriors' hair (or in one instance, a boar's razorback) being so spiky that falling apples are spiked on it. And then, a similar description appears in Fled Bricrenn (which I'm assuming is the Championship of Ulster you mention there?) which I will provide the incomplete ITS translation (which you can read in full here).

The scribe of Fled Bricrenn is probably borrowing from Togail Bruidne Da Derga or from another earlier source (which Togail Bruidne Da Derga would also be drawing on), because we know that whoever composed this story originally was very well versed with Ulster Cycle material. For example, the description of Bricriu's Hall is based on the description of Conchobar's Hall in Tochmarc Emire. If we look at the death of Conall Cernach (Aided Ailella 7 Chonaill Chernaig, which has been edited and translated by my Academic Big Sister for her PhD right here) we can see that there is no reference to Conall's eyes (similarly, the older translation by Meyer also doesn't have this detail). So, what appears to be the case is Candlelit Tales was expanding on the actual source material by incorporating elements from other stories. But, on to your question: What do I think about this eye? Well, because I am an academic I will apologize that before we get to my thoughts, we must cover the previous scholarship on the topic. This has only been discussed once, in an article entitled 'Portraits of the Ulster hero Conall Cernach: a case for Waardenburg’s syndrome?' in Emania 20 (2006) pages 75-80, by William Sayers. As you likely can guess based on the title, in this article Sayers argues that this description of Conall is modeled on Waardenburg's Syndrome. Now, of course, this isn't impossible. However, I am generally of the opinion that attempting to diagnose historical or literary figures is a very challenging thing to do. While it can certainly be done (particularly when combined with archaeological finds), when dealing with a literary figure we would need to take into account contemporary medical knowledge, and I'm unsure if we have any examples of medieval Ireland being aware of such a syndrome. If they were, we should be interpreting it through their medical knowledge rather than our own. That aside, I actually do have my own opinion on the matter. I think this is an artistic flourish intended to communicate how terrific (in both senses) Conall is, which I would argue is apparent when we take into account another notable example of a described heroic body. As mentioned above, this description of Conall is already incorporating visual elements from the 'Apple Hair' scenes in other stories. And then, we can take into account descriptions such as this of Cú Chulainn from O'Rahilly's Translation of Táin Bó Cúailnge Recension 1: ‘In the chief place in that chariot is a man with long curling hair. He wears a dark purple mantle and in his hand he grasps a broadheaded spear, bloodstained, fiery, flaming. It seems as if he has three heads of hair, to wit, dark hair next to the skin of his head, blood-red hair in the middle and the third head of hair covering him like a crown of gold. Beautifully is that hair arranged, with three coils flowing down over his shoulders. Like golden thread whose colour has been hammered out on an anvil or like the yellow of bees in the sunshine of a summer day seems to me the gleam of each separate hair. Seven toes on each of his feet; seven fingers on each of his hands. In his eyes the blazing of a huge fire. His horses' hoofs maintain a steady pace.'

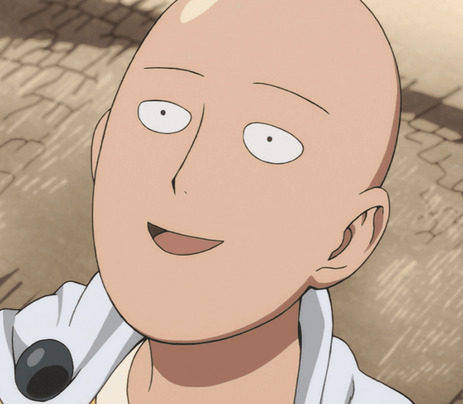

Now, this scene (another example of it is found in Recension 2 but it is different in some elements) often confuses people I am teaching this material. This is supposed to be a description of how wonderful or beautiful Cú Chulainn is, but his body appears strange or different. Burning eyes, seven toes, seven fingers. In Recension 2 he has four multi-coloured dimples, seven pupils in each eye, so on and so forth. This doesn't seem beautiful, it seems... awesome, both in the more recent positive sense, and the older more 'overwhelming' sense. I have been asked before if Cú Chulainn always looks like this, or if this is a transformation, or something else. And, well, it is not entirely clear. We have descriptions of Cú Chulainn where this clearly isn't the case and others where it isn't established. For Conall, we don't get many descriptions of his complete body (as an adult, we have one of him as an old man which is quite different). What we can say, though, is it clashes with the idealized flawless heroic body discussed by McMannus (McMannus, Damian, 'Good-Looking and Irresistible: the Hero from Early Irish Saga to Classical Poetry,' Éiru 59 (2009): 57-109). With this in mind, I think that these scenes aren't really literal, but more figurative descriptions going into luscious, awesome, terrific depth to establish the seriousness of the moment, the glory of the hero, and so on. The hero isn't as much transformed as being cast in a different light to communicate the moment. And this! I have a great analogy for. In animation, artists often distort or change a character to similarly communicate 'feeling' in the moment. Take three examples from the television show One Punch Man, all of the same character, Sitama.

In these scenes, the character Sitama isn't 'transforming'. These changes in his body aren't something 'seen' by people inside the story world. It is a visual effect intended to communicate things to us, the audience. In the first, we have a standard illustration of Sitama. In the second, a serious moment where we see him putting his complete effort into something. In the last, a comic moment. I think these descriptions of Conall, Cú Chulainn, and other ones for other heroes are similar to this. They're intended to communicate the feeling, the sense, and the emotion in the moment, rather than something we are intended to understand is how they 'always' look. However! What remains in this is to ask, if this is some sort of literary trick to communicate tone or feeling or the like, what do the individual parts mean? What's with the Apple-Hair stuff? Why the fire in the eyes? Why the seven fingers? So on and so forth. Well, a lot of this is lost to us, but parts we can identify. Personally, I think the Apple-Hair thing is a reference to Boar's Razorbacks (in the scene with Conall, this is being riffed on and changed to work with curly hair) connecting warriors to boar. The 'fire in the eyes' thing is just an Indo-European motif for warriors (see: McCone, Kim, 'Warrior's Blazing Heads and Eyes, Cú Chulainn and Other Firy Cyclopes, 'Bright' Balar, and the Etymology of Old Irish Cáech 'One Eyed',' Zeitshrift fur Celtische Philogie 69 (2022): 183-200). Exactly what the situation with Conall's eye is, I'm unsure. But, I think it exists within the broader literary tradition as a 'tone setter' rather than necessarily a literal fact of his appearance.

And all of that to say! What do I think of the difference between Conall having a black Iris v. a fully black eye? The one text of which I'm aware where it is mentioned doesn't clearly state what it means in regards to the eye. In the original language (Knott's edition) it reads: duibithir druimne duíl in t-súil aile. I think both interpretations of the eye are valid, but I expect that it is just intended to be 'iris' based on the description of Étaín's blue eyes at the start of the text using a similar grammatical construction (glasithir buga na dí súil, compare with the description of Conall's blue eye, glaisidir buga indala súil).

#mythology#celtic#irish mythology#celtic mythology#cu chulainn#celtic myth#conall cernach#medieval irish

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually let me pull up the list of Servants I've made in the past, just to name some names and let everyone know what kind of maniac you're dealing with...

Percival, Loki, Sun Tzu, Ahab, Hecate/Circe, Ajax, Hammurabi, Benjamin Franklin, Genghis Khan, Mansa Musa, Lilith, Nostradamus, Guy Fawkes, H. H. Holmes, Eve, Rapunzel, Baba Yaga, Abe no Ariyo, Dorian Gray, Clovis, Puck, Merovech, Conomor, Theseus, Aesop, Akhenaten, Ching Shih, Davy Jones, Henry Hudson, Pierrot, Lost Mariner, Hel, Hodr, Asushunamir, Conall Cernach, Rhea Silvia, Bao Si, Scipio Africanus, Tullus Hostilius, Demetrius, Flavius Aetius, Louis XIV / Prisoner In The Iron Mask... I don't think that's every Servant I've made but here we fucking are at least 40 names later.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

16 and 22?

you can't understand why so many people like this thing (characterization, trope, headcanon, etc)

You know, usually I think I can understand WHY people might be drawn to a certain character or characters, even when I don't agree with it. (I mean. We survived Vikings fandom together back in the day -- so many men who I personally did not understand the appeal of paired with some of the most jawdropping, astonishing women who were entirely underwritten and then unceremoniously tossed away.)

But...in reality...since I'm on the Shakespeare Salt Train...Mercutio. I have never fully understood the Mercutio love. I have TRIED, I have come CLOSE to understanding the Mercutio love, but I just. Can't. My life would probably be easier if I could, but I just. Cannot.

...likewise for Cú Chulainn. Misogynistic asshole bitch who abuses the women in his life and doesn't even appear as much in the Ulster Cycle as Conall Cernach but, hey, he's the standard that we judge ALL IRISH HEROES OFF OF, because have we MENTIONED that the ENTIRETY of medieval Irish literature is the CÚ CHULAINN SHOW? HAVE WE MENTIONED THAT CÚ CHULAINN IS THE GREATEST OF THE IRISH HEROES, BECAUSE I DON'T BELIEVE WE HAVE YET. WE'VE ONLY BEEN ANALYZING HIM SINCE THE CELTIC REVIVAL, I THINK WE NEED TO KEEP STRESSING THAT HE. IS. IRELAND'S. GREATEST. HERO. And he isn't even a DILF to compensate for it like Fionn.

...I'm fine, I don't feel any amount of professional rage over this, I'm FINE.

your favorite part of canon that everyone else ignores

I really, really wish that more people did work with Makt Myrkanna or the Swedish translation when they're discussing Dracula. I get why the DON'T, but there's so much fascinating stuff. Though I'm kind of GLAD they didn't because I ended up kind of disappointed by how Dracula Daily evolved, even though I kind of predicted it. Like, this is something that's still mostly MINE and a few others'.

6 notes

·

View notes