#clues to cultural nuances in folklore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

With my memory triggered by this Tumblr Poll (about Doctor Who OCs),

I went looking through old LiveJournal/Dreamwidth posts, to see if I'd posted any actual excerpts of my "Project" novel to my character Eloise out of the Fandom Space, and reposition her within her own, original, universe.

Along the way, I found this drawing of her, in her Non-Fandom character form, along with some stuff about my Project (from 2015):

Excerpt of a comment I left:

And for this endeavor, I've decided to go back to the folk tradition as my 'canon' -- in so doing, I noticed two primary constants:

1) in every aspect except human standards of "beauty," the Scandinavian Trolls and the Celtic Fey are near-perfect analogs of each other, in terms of their "ecological niche."

2) The trolls that appear in stories that have humans protagonists who are peasants and farmers are portrayed as honorable (if potentially dangerous) neighbors and partners to humans. When the human protagonists are merchants, or otherwise verging on "middle-class," trolls are depicted as evil and violent -- and swindlers, such as you see in "Billy Goats Gruff" (the troll in that story has planted himself under a human-constructed bridge -- presumably in, or very near, a town -- as opposed to a cave in a mountain gorge).

#image description in alt#folklore trolls#my own drawing#clues to cultural nuances in folklore#Who's telling the story? Who's the audience?#Early-Stage Capitalism#The three billy goats gruff

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore: Music

Link: Disclaimer regarding D&D "canon" & Index [tldr: D&D lore is a giant conflicting mess. Larian's lore is also a conflicting mess. There's a lot of lore; I don't know everything. You learn to take what you want and leave the rest]

Useful for bards and priests, one assumes. I had to look up so many songs I'd never heard of to have a clue what half the comparisons were...

Musical education in the Realms (plus what the core Colleges (Lore and Valor) translate to in the Realms (where they aren't called that))

Musical vocabulary

Instruments

Music itself, including: operatic, 'symphonic'-ish, renaissance-style, hymns, 70s folk bands, and 70s rock music. [Popular music | Hymns | Opera | Demihuman traditions] (we got music that sounds like Leonard Cohen, Sinéad O'Connor, 70s folk music, 50s folk music, ELO, Genesis...)

Education

The majority of trained musicians, including bards, start off being apprenticed to accomplished bards willing to tutor, and some seek out Bardic Colleges. The exact focus, quality and curriculum varies by the institution.

To be admitted one must have some experience performing, and be able to pass an audition. They will perform before one of the master bards of the college, as well as one 'invisible' listener they're unaware of. Both masters must agree that the candidate is worth teaching or not for admission, if they don't agree further auditions will follow until they do agree on a verdict.

'Low-order' colleges generally concentrate on mastery of pitch, timbre and nuance. Students are taught to sing scales and perfectly duplicate overheard notes and tunes with their voice, as well as memorizing a set of tunes on a range of instruments to familiarise themselves with different keys and methods. The crafting and repair of one form of instrument is also part of the training.

'High-order' colleges offer a wider range of instruments and repertoire, teaching the history behind the music and lyrics, as well as some language tutoring - not necessarily to speak the language, but to be able to sing such songs perfectly.

New students to any college will be taught the basics in classes at first, but very soon will be passed onto a tutor for one-on-one tutoring.

Pretty much all official colleges in the Realms would make you a College of Lore bard in core DnD terms.

What is called The College of Valor does not actually involve colleges, and is found amongst warrior cultures like Orcs or the Illuskan Northmen, Uthgardt and Reghed: skalds - warrior poets, lorekeepers and clan storytellers.

The most prestigious colleges are the College of Fochlucan in Silverymoon, an ancient bardic tradition which I assume from the name is supposed to be from Ffolk tradition (the Moonshaes). This college has close ties to the Harpers, though most members will stress that their mission and activities are separate to avoid being targeted by the Harpers' enemies.

The College of the Herald is also found in Silverymoon and was founded by a Harper in 922 DR to preserve history. The college maintains a strict neutrality towards the conflicts of the world, and its focus is on preservation of history, folklore and legend over music.

The College of New Olamn, once Ollamh, another ancient bardic tradition, is in Waterdeep, established in 1366 by wealthy patrons of the arts.

On a less formal level, priests of Milil are charged with spreading music and teaching as many as possible to play and sing, and followers of EIlistraee are to 'nurture beauty, music, the craft of making musical instruments, and song wherever they find it.'

Vernacular

'Minstrelsy' is a term for live music, not including hymns and holy music. Recorded music does exist, though mostly in the form of spells that exist to capture and play the song back on command. People like to use them for study, meditation, fun, etc. If you don't have access to magic, due to cost or general mistrust of the stuff, the Gondians have invented music boxes. You can also get those jewellery boxes with the spinning dancer that play music when they open.

A 'song' is monophonic performance or piece, consisting pof a single vocalist with no instrumental accompaniment.

'Allsong' is the term for polyphonic pieces; covering vocals with instrumental accompaniment, multiple singers such as choirs, and orchestras.

'Newclang' is recent music that starts playing with or breaking conventions. May be viewed as a brilliant invention or modern pop garbage, depending on your tastes.

'song-cycles': 'extended stories told by ballads being sung in a particular sequence. Most of these are 'later inventions,' concocted by a minstrel or bard stringing together their personal favourites (or tunes that they could perform well, and that were popular with paying audiences) into a story of sorts, and then knitting them together with altered lyrics, additional linking songs, and sometimes short spoken-word orations, into the tale of one hero's life, or a romance, or the reign of a villainous king, or the saga of a fearsome dragon or other predatory monster (and its eventual defeat).'

If the performance is 'wordless' then there are no sung lyrics. There might be vocalisations along with the music, but as per the name, no words.

The concept of sorting music into genres apparently hasn't much occurred to anybody yet; music is music in most people's eyes. Historical music trends are named after popular artists of the time. Still you have lammuer (slow waltzes), whirls (reels) and tonsets (courtly formal dances).

There is no standard agreed upon scale that is used by the whole of the Realms.

-

Instruments

The instruments most frequently seen in the hands of common minstrels are lutes and harps. Bells, clapping or stamping one's feet, rhythm sticks and a small wooden pipe akin to a penny whistle serve as accompaniment, and for major percussion instruments you have hand drums and 'great drums' (kettle drums).

Ocarinas, kazoos and mouth harps are pretty common.

Yarting: An acoustic guitar, basically, with origins in Amn and Calimshan, but variations exist everywhere.

Songhorn: Recorders

Straele: A violin-like instrument, shaped a bit like a metronome and played cradled in one arm (preferably while sitting).

Great staele: Cellos and basses

Drone: A large, stationary double-reed instrument with a bladder and several mouthpieces, played by multiple musicians and sounding either like the drones of a bagpipe or an organ or synthesizer.

Jassaran: a crude 'keyboard-and-wires' instrument invented in Sembia that sounds something like a harpsichord.

Artang: A dulcimer, though artangs are only plucked or bowed.)

Shawm: A gnomish instrument that's something like an oboe or bassoon in form. There's also a bellows powered variant.

Zulkoon: A Thayan pump organ. Pipe organs also exist.

Tantan: tambourines. Popular with halflings.

Longhorns: flutes

'Birdpipes' or Shalm: pan pipes. Most popular with Lliirans and elves, particularly copper and green elves.

Tocken: carved oval bells set to hang so that they can be lightly struck. Instruments such as this are found in subterranean cultures (Dwarves and goblins, mostly). The sound echoes through the structures.

Glaur: Basically a trumpet (more specifically it sounds like a renaissance instrument called a serpent), shaped something between a cornucopia and a saxophone.

Gloon: Much like a glaur, but lacking in valves and it produces a markedly mournful sound.

'Whistlecanes' or thelarr: The bane of parents. Basically just a cut reed you can whistle with. People like to give them to children, who do as children do and proceed to give everybody ear aches from badly played instruments.

-

Music

With a note that a lot of the following kind of applies to the Sword Caoast, Heartlands, Cormyr, Dalelands and etc. Different regions of Faerûn have different music. The kind of Thayan music you'd hear in alehouses in East Faerûn, for example, apparently sounds like this. (Songs with such tunes are called 'thaeraeden,' or 'life laments', and the lyrics are often melancholy questions and challenges. Usually break up songs and unrequited love, the usual.)

So, switching out more modern instruments like drumkits and electric guitars, this is the kind of music you'd apparently expect to hear from minstrels, street and tavern performers and etc. This is basically turning on the radio:

Popular ballads and songs sound something like:

These: X, X, X, X,

Stuff like Leonard Cohen. X

1970s folk music, like Steeleye Span and Maddie Prior. Like the Prickle Eye Bush X, X.

Tongue-in-cheek songs like the Irish Ballad are popular with the working class. I feel like that one specifically would be popular with drow and Bhaalspawn, personally.

'Easy listening' being played in the background while you're passing the evening at a tavern sounds like standard Renaissance fare like Packington's Pound and My Thing is My Own.

Dance music would sound something like this: X

The kind of music you're likely to hear at an upper class party is going to be bringing in musicians and possibly orchestras and dancing. Stuff like this: X, X, X, X,

Orchestral music doesn't utilise strings very much, and prefers to use vocalisation in its place. You generally get more stuff like this.

-

The Opera

Inasfar as I can tell, the opera is exactly what you expect.

The most famous/popular operas include:

'the War of Three Castles:' Featuring a bunch of kings throwing their sons and daughters off to lead armies against each other. Disaster strikes, two princes and a princess are trapped in a tomb in the Underdark and a love triangle ensues. The princess decides fuck that nonsense, she will have both or neither but she's not having this drama, and they work out a polyamorous relationship, and agree that they will go home and have a 'marriage of three crowns' where they all marry each other, even if their fathers may try to stop them or execute them for it. Then they get back up there, discover that their fathers have been killed turning the entire region into a war torn region. They recover what is left, and they get married and unite their kingdoms in peace and like happily ever after.

'Alvaericknar:' The lovable rogue archetype who shares his name with the title bites off more than he can chew trying to rob a lich - who kills him. But he's prepared for that, and due to ensuring that the lich killed him in a spot that would set of several enchantments he manages to come back as undead, and proceeds to continue his hijinks. 'As an undead, he goes right on being a swindling, fun-loving rascal, only now he doesn’t need food or drink or shelter.'

'Downdragon Harr': An evil sorceress turns a princess into a dragon, uses magic to disguise herself as the princess, murders the king and takes over the kingdom. Her first decree is to have every dragon in the kingdom slain (all dragons are played by bassi profundi). A knight with a magic sword wounds the princess in her dragon form, and the enchantment on the blade breaks the spell on her. They fall in love via duet, and then go to the most ancient wyrm in the land (the titular Harr), wake him from his centuries long slumber and use him as their steed to fly off and challenge the sorceress. 'She sees their approach and uses mighty sorcery, that drains the life from most of her courtiers and all of her guards, to slay the dragon as it dives down on the castle—but in death, it slays her, crashing into the castle and crushing her to pulp under its great bulk as it slides to a (dead) stop. (It sings in death, and so does the queen from somewhere under it.) The princess and the knight begin their happy rule, and wedded bliss, atop the carcass of the great dragon.'

One suspects dragons do not care overmuch for this opera.

-

Hymns:

Religious music is typically plainchant, a form of music that usually consists purely of vocals (typically a solitary singer). There is no set rhythm, as the song consists of singing prayers and religious verse. Sometimes there's the occasional accompaniment from a instrument, such as an organ, or a slow heavy drum beat, in the case of Banite hymns.

They can be more complex: polyphonic hymns involve 'two or more singers or instrumentalists playing independent melodic lines at the same time.'

The hymns of most faiths sound most akin to Gregorian chanting. At its softest and most elaborate, you get something that sounds something like a simplified Enya song.

-

Elves

Ah yes, the mysterious and magic melodies of the Tel'Quessir...

Which apparently sound a lot like, say, Don't Bring Me Down, Land of Confusion, Domino Medley, Mr Blue Sky...

They also have your Enya and Loreena McKennit type stuff.

Replace the guitar with a harp, maybe throw in a flute, that's elven music. It's rock. Elven instruments are the only instruments thus far capable of sustain. The effects on the vocals can be replicated by elves, who have a strange quirk with their vocal chords where they can produce two notes/sounds at once, distorting their voice in a way that's similar. Some have a genetic quirk that allows them to sort of say 'two things at once.' Generally elves prefer softer singing voices.

Elven musical performances feature galadrae - three dimensional illusions depicting scenes to go along with the song, not dissimilar to what one might see at a modern concert. Generally the theme is the history/story behind the piece.

Common elven folk songs are apparently these: Laeryn's Lament My Love Green And Growing Blood of My Sisters The Moondapple Stag Knights On The Ride Thorn Of Rose Winterwillow [an instrumental] Greenhallow Mantle Stone Fall, Tree Rise The Lady Laughing

-

Dwarves

Dwarves like drums and metallic percussion for their music, and vocals tend to be plainsong.

Large clanholds with volcanic vents may build giant complex pipe organs.

'...usually dwarves play piano-like personal instruments (strings hit with hammers; hitting things with hammers is the dwarven way). Most such dwarf instruments look more like an accordion (small portable keyboard) and have metal strings.'

-

Gnomes

Gnomes like drones and oboes (or shawms, I guess). Traditionally, history and lore has been an oral tradition kept by women, so it wouldn't surprise me if some lorekeepers sing it.

-

Halflings

Halflings are apparently known for their comic, and usually bawdy, operas, which are popular with gnomes and dwarves. Titles include 'Ravalar’s Roister In The Cloister; Yeomen, Bowmen, and The Taming Maiden; The Seven Drunken Swordswingers Of Silverymoon; The Haunted Bedpan; The Laughing Statue Of Beltragar; and The Night Six In-Use Beds Fell Into The Castle Moat.'

Outside of that their music overlaps a lot with human music trends.

-

Orcs and goblins

Heavy drumbeats, gongs, warhorns and rhythmic shouting/chanting.

-

Dragonborn

Nothing outside of BG3 that I see, so I'd go with what the game says: throat singing.

#Music on Toril: apparently a grab bag of genres where the 1400s and the 70s collided#'The Prickle Eye Bush' is going to be in my head for a while...#lore stuff#long post

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghosts and Confusion

A common motif in literature, folklore, and cultural traditions worldwide is the notion that ghosts cause bewilderment. Frequently, we portray this perplexity as both situational and psychological, stemming from the ghost's ambiguous character and capacity to disrupt reality's normal flow. By definition, ghosts are in a state of transition, caught between the material and the immaterial, between life and death. For individuals who come into contact with them, this ambiguous nature tends to cause confusion. Ghosts are known to manipulate perception in order to cause confusion. People who experience ghosts frequently describe seeing brief shadows, hearing unexplained noises, or experiencing unexplainable sensations. These nuanced and frequently contradictory experiences make it difficult for people to trust their own senses, leading them to question the difference between reality and imagination. This loss of confidence can turn into anxiety or paranoia, particularly if the spectral activity gets more intense or invasive.

The ghost's motivations, which are frequently ambiguous, contribute to this misunderstanding in another way. Often, people depict ghosts as mysterious spirits, while live individuals typically dictate their actions by observable objectives or feelings. Their communication styles are usually vague and indirect, even if they may seem to be asking for assistance, issuing a warning, or seeking retribution. For example, a ghost may appear as an eerie presence in a particular place, leave perplexing clues, or repeatedly relive horrific experiences. Such behavior forces witnesses to piece together scattered data, leading to doubt and mental strain. Ghosts' challenge to the distinction between the natural and the supernatural may exacerbate confusion. Ghosts can validate long-held concerns or beliefs for those who believe in them, but for skeptics, an encounter could result in a radical rethinking of how they perceive the world. People may feel disoriented and uncertain of what to do as a result of cognitive dissonance, which occurs when the mind finds it difficult to reconcile an inexplicable experience with accepted reasoning or science.

According to some stories, spirits purposefully employ confusion as a means of achieving their objectives. In order to confuse their targets and make it harder for them to resist or flee, they may manipulate time, space, or memory. For instance, a ghost might create an endless number of hallways in a house, guide a person in circles, or alter their perception of time, leaving them in a state of confusion. These strategies can increase a person's level of fear and vulnerability, making them more vulnerable to the ghost's control. In the end, ghosts' perplexity is more about a deeper existential uneasiness than it is about dread or misdirection. Ghosts serve as a reminder of death, unresolved trauma, and the unknown. Their capacity to obscure reality reflects humanity's inability to understand the mysteries of life. Real or imagined, they represent the chaos that lurks just beneath the surface of everyday life, making people wonder about themselves and their environment.

0 notes

Note

Do you know of any books that are good at introducing folklore from Asian cultures or African cultures without subscribing to exoticism? I have found it stupidly difficult at times because the translations and available art work is often fairly "generic" to expected cultural signifiers and they lack the cool aspect I would expect from ie a good British anthology of being cognizant of interesting regional nuances or specific regional denizens. Or just a name of a translator you trust would be good! Someone who has a good body of work to start working through

Sadly this is something I'm still struggling with myself!

In pursuit of my own heritage I've been searching for folklore from Curaçao and West Africa, but it's very difficult to gauge which translations and collections are faithful to their sources. (Or what their sources even are.)

Any culture that you did not grow up in and that you do not speak the language of will be difficult to study. When I read a text translated from Mandarin or Swahili I have no way of looking at the original to see if they did a good job and I won't be able to pick up on out of place details that would alert a person more familiar with the culture that there has been meddling.

I will tell you what I try to look for, but I'm afraid it stays a struggle:

Try to find collections where the author was part of the culture the stories originate. A good starting place is just googling "famous folklorist/fairy tale collector" for the place or people you're looking for. Or "preserving x oral tradition/folklore". Once you've found someone, you have to hope their works were translated into a language you can read.

Try to find works written by someone who spoke the language of the culture of origin. This is often easier to find among scientific articles on culture and folklore, but those do tend to be harder to read.

Search for folklore from a specific geographical area or cultural group, anyone bothering to narrow that down has done more work than someone making a huge collection.

Check if the names in the text haven't been translated. Obviously they need to be romanized, but that doesn't mean Japanese heroes are suddenly called Thomas. Original names of certain foods or plants are also a good indication.

Check if there are footnotes and/or a glossary with cultural explanations. This shows that the writers were invested in getting across more than the translation could hold.

If there is an introduction or afterword, scan those for clues on the author's position. Respect for a culture will show, so will sensationalism or exoticism.

Keep in mind most translators continually have to choose between staying close to the source and being easily understood. Especially if they want their works to be accessible to children they may go for the latter. When a translation says "fairy" or "mermaid" it may just be the closest equivalent for that culture, so stay mindful of that.

If you can find a collection that actually gives a source for each story, hold that book tight and never let it go.

I'm hesitant to give you titles of books. What passes my "probably pretty faithful" test may not pass yours. Also some of the best books I've been able to find that include clear sources for their tales from India, China, Suriname and Indonesia are in Dutch. Just like my one book of Antillian Nanzi stories and a pretty decent collection West African tales.

You're right it is stupidly difficult, but there are definitely people out there preserving their cultures and also translators doing their best to help spread their work further! I hope this will at least be somewhat helpful in finding them ^^;

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, @tonyglowheart , here is that promised response:

@three--rings already brought up some points I was going to mention so I’ll skip over going into detail on those and just say that I agree with the use of caution and thoughtfulness in approaching works produced by other cultures (of whatever language), and I, too, love a mash-up of MDZS and CQL for ideal storytelling. Accepting genre tropes in general is really important as well. I once showed my grandfather a piece of my writing based on pulp adventure stories like Indiana Jones and his main reaction was “All these secret chambers and codes and gadgets, isn’t that all very convenient?” and I just had to shrug and say, that’s the genre, it’s part of what makes it fun to read. Also, based on reading about various medicinal histories I’ve been exploring, I can say that the coughing up blood thing is a trope based in Ancient China’s traditional medicine. Lots of pre-understanding-of-blood-circulation societies thought expelling old or stale blood was important for the body (possibly based on how menses works and reflected in Western medicine’s several-century-long obsession with bloodletting), and I recently read that having it caught in your chest and needing to cough it up was part of China’s take on things. I’m still not sure about all the other face bleeding, but if it’s not actually based in something historical it seems like a reasonable extension for the genre.

Okay, so the thing I want to respond to most is the translation bit, because I… okay. I understand that people are going to find works in translation less accessible than works written in a language they can read, and especially works written in their native language and of their own culture. Because obviously there are a ton of underlying ideas that inform word choice and symbolism and character arcs that most people just don’t really think about until they make a serious study of writing or literature (or they travel and learn more about other languages and literature traditions). On a linguistic studies level, language literally shapes the way humans in different cultures think, and what they pick out as important (an academic article that compares English and Chinese specifically can be found here). Even the distinctions between British English and American English, on a word choice and theme or syntax level, can have an impact. I have seen it turn kids off a book, because there are just too many elements they don’t get (this is, for example, why there are two English versions of Harry Potter). Same thing with different decades even. I’m talking about kidlit and YA here because that’s a lot of what I work with, but in that realm, the way we approach stories today is just incredibly different from how they were approached even 50 years ago, even in the same language and the same country. Think Judy Blume or The Dark is Rising vs Diary of a Wimpy Kid or Percy Jackson. And I’m fascinated by those changes, and by the effects of culture and bias on translations (I am extremely hyped to read Emily Wilson’s Odyssey translation, for example), so I tend to approach them as puzzles, where I’m reading the work, but also looking for clues that will tell me more about both the translator and the author to hang in balance. I enjoy that part, and I enjoy figuring out aspects of the two languages that can contribute to how a translation evolves.

I’m a language and literature nerd, and I know not everyone is going to take the approach I do. I’m not going to fault anyone for saying they don’t enjoy or can’t get into a translation. That’s a perfectly valid opinion. Reducing a work to its translation and judging it only on that impression of it, however, seems pretty shortsighted to me. Here are some things that I think are important to keep in mind when reading a Chinese work in translation, just based on my own extremely limited knowledge:

1. In Chinese storytelling it’s an established practice to reference idioms, poetry, folklore and historic events as a sort of shorthand for evoking the proper tone. Chinese writing tends to be extremely allusive, and much more understated than what we’re used to in English-language storytelling. We can see hints of this in some of the MDZS translator notes, and it’s likely that this difference feeds into a lot of dissatisfaction with the translation. Either the allusions are not translated in a way that adds meaning for an English-speaking reader, or the standards for detail are different. Indirectness and subtly are huge parts of Chinese literature, and so different words or scenes will have very different connotations for Chinese vs. English speaking audiences. And this isn’t even touching on the use of rhyme and rhythm in Chinese writing, which are all but impossible to translate a lot of the time, or the often extremely different approaches to “style” and “genre” between the languages (an interesting article on comparative literature is here at the University of Connecticut website). Given this knowledge, it’s entirely possible that, for example, the smut scenes are more effective in Chinese than in the English translation. In fact, I find it difficult to believe it would be popular enough to get multiple adaptations and a professional publishing run if they weren’t. In translation, smut is a lot like humor: every culture approaches it a little differently. Unless a translator is familiar with both writing traditions and the relevant genres (or they have editors or sensitivity readers who can offer advice), something is going to get lost in the process. And sometimes that something is what at least one of the involved cultures would consider to be the most important part. It’s unfortunate, but it happens.

2. Chinese grammar is slightly different from English grammar (and I’m focusing on Mandarin as the common written language here. For anyone interested, a very basic rundown of major differences is available here). Verb tenses and concepts of time work differently. Emphasis is marked differently – in English we tend to put the most importance on the start of a sentence, while in Chinese it’s often at the end. Sentences are also often shorter in Chinese than in English, and English tends to get more specific in our longer sentences. From what I understand, it’s also a little more acceptable to just drop subjects out of a sentence, and that is more likely to happen if someone is attempting to be succinct. I’ve been told that it’s especially common in contentious situations, as part of an effort to distill objections or arguments down to an essential meaning (if I’m wrong about this or there’s more nuance to it, I’m happy to learn more). As one example of how this affects translation, let’s take that and look at Lan Wangji’s dialogue. I’m willing to bet that most of his words are direct translations, or as direct as the translator could manage. But his words don’t work the same way in English that they do in Chinese. If you continuously drop subjects and articles (Chinese doesn’t have articles) out of a character’s speech in English, they start to sound like they have issues articulating themselves, and I see that idea reflected in fic a lot. The idea that Lan Wangji just isn’t comfortable talking or can’t say the words he means is all over the place, but I don’t think the audience was intended to take away the idea that Lan Wangji speaks quite as stiltedly as he comes off in the English translation. He’s terse, yes. But I at least got the impression that it’s more about choosing when and how to speak for the best effectiveness than anything else, because so many of his actual observations are quite insightful and pointed, or fit just fine syntactically within the conversation he’s part of.

3. Chinese is both more metaphorical and more concrete than English in some ways. In English we use a lot of abstract words to represent complex ideas, and you just have to learn what they mean. In Chinese, the overlap of language and philosophy in the culture results in four-character phrases of what English would generally call idioms. Some examples I found: “perfect harmony” (水乳交融) can be literally translated as “mixing well like milk and water” and “eagerly” (如饥似渴) is read as “like hunger and thirst.” If these set phrases are translated to single word concepts in English, we can lose the entire tone of a sentence and it’ll feel much more flat and... basic, or uninspired. The English reader will be left wondering where the detailed descriptive phrase is that adds emotion and connotation to a sentence, when in the actual Chinese those things were already implied.

As translations go, MDZS in particular is an incredibly frustrating mixed bag for me, partially because of the non-professional fan translation, and partially because my knowledge of Chinese literature and especially Cultivation novels is so minimal as to be nearly non-existent. But I have enough exposure to translations in general and Chinese language and literature in particular that I could tell there were things I was missing. The framework of the plot and scenes was too complete for me to ever be able to say that any particular frustration I had was due to the author, not the translator. There’s a big grey area in there that’s difficult to navigate without knowing both languages and the norms of the genre extremely well. At one point I was actually able to find multiple translation for a few of the chapters and I loved that. It was really cool to see what changed, and what remained essentially the same, and I was actually really surprised to find that rant you mention, because to me, more translations is always better. I think it was probably about wanting to corral an audience, and possibly also about reducing arguments from the audience about whether a translation was “wrong” or “right.” And that is an issue that’s going to crop up more in online spaces than it has traditionally. Professional translators don’t have to potentially argue with every single reader about their word choice. But then, professional translators also tend to have a better grasp of both the cultures they’re working with as well, and be writers of some variety in their own right, and while I can’t know how fluent (linguistically or culturally) the ExR translator was at the time, the translator’s notes lead me to believe that at minimum their understanding of figurative language use was incomplete. So I can’t fault people for not enjoying the translated novel as much as CQL, for example, because it can be quite choppy and much of the English wording feels like a sketch of a scene rather than something fleshed out fully, but I don’t think it’s fair to apply that impression to MXTX herself or the novel as a whole in Chinese.

More about ExR: I also got the sense that they have a strong bl and yaoi bias as you mentioned, mostly from the translator’s notes. And in general, okay, that’s fine, they’re working with a particular market of fans and I’m just not as much a part of that market. I knew going in that I wasn’t the target audience. I’m okay with that. What I was less okay with was getting to the end and reading the actual author’s notes in translation and finding that the author herself expressed a much more nuanced, considerate, and balanced approach to the story and her writing process than I had been led to believe by the translation and the translator’s notes. And so when people want to criticize the author for things that happen in the translation…. I just think it’s very important to remember that the translator is also a factor, as is the influence of the cultivation genre, and the nature of web novels, and the original intended audience. As you said, white western LGBT people were never the intended recipients of this work. It comes from a totally different context. But I think it’s also important to remember that, again as you noted, it wasn’t first written as a professional work. It was literally a daily-updated webnovel, which works a lot more like a fanfic than a book in terms of approach. And on top of that, it was the author’s second novel (if I’m reading things correctly) and one that they experimented with a lot of new elements in. Those elements earn a lot of forgiveness and benefit of a doubt from me.

About MXTX herself: Most of the posts or references to posts that I’ve seen that judge or dismiss her have to do with the stated sexuality of characters who are not Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji. And it just kinda baffles me, because this is fandom. Most of us spend our time writing about characters who are stated to be straight all the time. Why is anyone getting up in arms about this? How can anyone in fandom just summarily dismiss an author for producing original work that centers around a gay relationship when that’s… literally what most of us write, to some extent or another? Again, I’m not saying there’s aren’t aspects that can be criticized in her stories, but the hypocrisy is kind of amazing. I think that fandom, as a culture overall, has issues with treating gay men and their relationships as toys rather than people, and individuals can address their own behavior on that as they learn and grow. That doesn’t mean that every work about gay men having sex is fetishistic, and honestly I’d say that the translator demonstrates more of that attitude than the actual story ever does. The smut is such an incredibly tiny part of the world, plots and character arcs in MDZS that it could be taken out without significantly changing the main narrative very easily. That’s… not fetishistic. That’s smut as part of an overarching romance plot.

Which leads me to the tropes discussion. Yes, obviously there are tropes in MDZS. There are tropes in every story. It’s not a failing, it’s part of writing. Are some of those tropes BL or Yaoi tropes? Sure. Wei Wuxian denying his own sexuality for much of the novel and his tendency toward submission and rape fantasy are some of the very first tropes mentioned in relation to the genre. That Wei Wuxian just sort of seamlessly moves from “pff, I’m NOT a cutsleeve, I’m just acting like one” to shouting “Lan Zhan, I really want you to fuck me” in front of friends, enemies and family without much of a process for dealing with the culture of homophobia around him also seems to be characteristic of the genre. But I think that’s about where it ends. You and @three--rings both made some good points about the nature of the actual relationship, which I agree with: There’s not much of a power play element, or an assigned gender roles element. They’re both virgins who only partially know what they’re doing from looking at illustrations of porn, and they do enthusiastically want to have sex with each other. They’re just bad at negotiating their kinks clearly and could use a decent sex ed manual. The trope I actually have the most issue with is the use of alcohol. I personally despise the trope of “I’ll get someone drunk on purpose for reasons that benefit me personally,” due to my own real life experiences. But it’s an exceedingly common trope in Western media (Idk about Chinese media, but my guess would be it exists there too), and it’s not exclusive to mlm smut scenarios. It’s pretty much everywhere. And, thankfully, Wei Wuxian does seem to eventually realize that he’s fucking things up by using it. That said, despite knowing what happens to him when he drinks, La Wangji keeps doing it. So they’re both contributing to that mess, no matter how much I dislike that it exists, and the narrative doesn’t actually condone it. No one says “Oh, Wei Wuxian, that’s such a good idea, that’s definitely something you should keep doing.” He is consistently warring with himself over it but unable to resist. It’s still dubcon and manipulation, and I certainly understand people not wanting to read it. I just also think that reducing the entire relationship down to “bad, terrible, fetishistic BL tropes” requires the reader to ignore large parts of the story and pretty evident intent on the parts of both the characters and the author.

On purity culture: Yeah, that’s obviously been cropping up all over the place the past several years (I have indeed been in marvel for ages :P). It does seem like there are places in fandom (to some degree any fandom), where “I don’t like how this idea was executed in this context” gets conflated with “This entire work is terrible,” which is a disservice to everyone involved. I agree that there are many things that can be legitimately criticized in MDZS, but I also just… really don’t understand where this attitude comes from that because something is not perfect, it’s trash. Wasn’t fandom essentially invented out of the desire to respond to canon? To make it more your own? Isn’t picking out the parts you like and ignoring the bits you don’t (or writing around the bits you hate until you can fit them in a shape you like better) pretty much what all fic is about? Aren’t those holes people are sticking their fingers into and complaining about opportunities for more fan content? But even more than “purity culture” I would term it “entitlement culture,” because a lot of it seems to be about the idea that media should fit into and support a certain set of beliefs at all times. A lot of fandoms are no longer an atmosphere of “I don’t like the way this is presented so I’m going to create my on version that works for me.” Instead there’s a growing element of “I don’t like the way this is presented so that means it’s wrong and bad and the original creator should admit that it’s wrong and bad and fix it to satisfy me.” And honestly? That’s just sad to me. More and more, we’re not having a conversation with canon, or even with each other. We’re not building what we want to see we’re just… tearing other people down. I really don’t understand what anyone finds fun in that, and I’m going to do my best to keep creating the things I actually do want to see instead.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

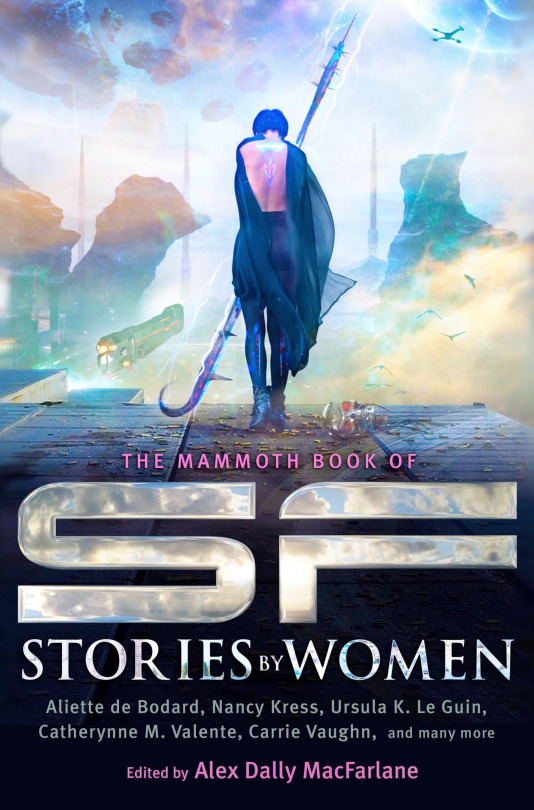

The Mammoth Book of SF Stories by Women – Review

Edited by Alex Dally MacFarlane 2014, Running Press Paperback, 512 pages, $17.50 CAD

Rating: ★★★☆☆

Good: Great diversity, showcases excellent talent Bad: Not all stories are a worthwhile read

In her introduction to The Mammoth Book of SF Stories by Women, Alex Dally MacFarlane does a good job of laying down the purpose of the collection. She is not looking to change the sexism that festers within the writing industry, but is instead interested in building on a rich history of women writers in science fiction, demonstrating what female authors are able to do. Though if given the chance, I'm sure the authors in this anthology would see women given their rightful place as prestigious members of the industry. While things are rarely that easy, the stories collected here speak for themselves as to what women can accomplish when given the chance. I don’t think every story in this collection is worthwhile, but I also think that shouldn’t be taken as a slight against female authors, as I found many to be engaging reading experiences. I also would like to preface by saying I’m not generally a fan of short story collections; it takes me too long to read them, and I find myself cheated if a short story isn’t as good as I expected. I tried my best to not let this influence my opinions, but I may be harsher on some entries in this collection as a result.

To give each author the attention that is due to them, I will be reviewing each story on its own, and then conclude with my opinion on the anthology as a whole.

[ ! ] Spoiler Warning

Girl Hours

by Sofia Samatar, 2011 Rating: ★★★★☆

Girl Hours is a short poem written in reverse chronological order about the life of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, a woman computer from the 1870's. Being based on true events and taking the form of a poem, it has little to do with science fiction, though it is still an interesting read. As with most poems, word choice is limited, putting much of the onus on the reader to establish themes and timing. I normally find this pretentious, but I enjoyed the format in this instance. Girl Hours is one of the few stories I have read multiple times out of pure enjoyment, as its structure allowed for reading front-to-back as well as back-to-front, letting the reader to experience the poem differently each time.

Link to Poem

Excerpt from a Letter by a Social-realist Aswang

by Kristin Mandigma, 2007 Rating: ★★☆☆☆

Excerpt from a Letter by a Social-realist Aswang is an interesting take on socialist mindsets. The text itself is enjoyable in its tone, but fails to make a lasting impression on me. I would have liked to see more of the world than what was presented, as the piece consists only of its namesake: an excerpt from a letter by an Aswang. While I find gaps in a narrative to generally be a good thing, it can be frustrating when that gap is too wide—as if the author is expecting the reader to fill in the majority of the worldbuilding for them. The strength of Excerpt from a Letter by a Social-realist Aswang is in its lighthearted tone, which Kristin Madigma uses to criticize socialist mindsets through the writings of the author-character. The aswang rambles about communist ideals and writes degrading comments about capitalism—like any good neo-communist. The fact that the author-character is an aswang adds onto the ridiculousness of the situation, as they include activities such as the consumption of capitalist children in their socialist portfolio. Excerpt from a Letter by a Social-realist Aswang is a fun little piece that would benefit from an expanded narrative, and I felt that it was ultimately forgettable in its details.

Link to Short Story

Somadeva: A Sky River Sutra

by Vandana Singh, 2010 Rating: ★★★☆☆

Indian culture has never been something I’ve personally found interesting. As Somadeva: A Sky River Sutra relies heavily on cultural artifacts and historical persons from India, I often felt lost in its many references. I think Vandana Singh did a good job of explaining the most relevant parts to her story, but the folklore is far too complex and I do not have the desire to investigate it further. I thoroughly enjoyed the themes, as Singh builds stories within stories within stories, creating her own mini-compilation of folktales and adventures. Narration is well done, as is the imagery, which accurately describes how time-lost souls would search for meaning in a world where memory is fleeting at best. However, there was a bit too much going on and it ends a bit abruptly for my taste; I would have preferred some kind of conclusion, even if it did not conclude with the protagonists’ journey. I am sure those interested in Indian culture will find this story much more compelling than I did, but the themes are strong enough to hold up the story on their own.

Link to Short Story

The Queen of Erewhon

by Lucy Sussex, 1999 Rating: ★★☆☆☆

I’ll be honest in that reading The Queen of Erewhon was like reading Shakespeare from the future—and not in a good way. If you’ve ever had to read Shakespeare in its raw, historically-correct format, you may have had some issues understanding some of the nuances inherit from the time period in which is was written. Something similar is the case with The Queen of Erewhon. Lucy Sussex keeps shifting between two different narratives: one that details the protagonist’s journey to uncover a story about two women falling in love, and the actual story of these two women falling in love. On its own this was confusing enough; there is no clear delineation between when one narrative starts and another one ends. I kept having to stop reading to reorient myself whenever this switch occurred. My confusion was aggravated further by Sussex’s rich, almost overpowering politics and worldbuilding. Every other passage contains extensive amount of exposition that dilutes the purpose of the story. I normally don’t enjoy unfiltered politics in fiction, and The Queen of Erewhon has some of the worst examples of this. And yet, despite my difficulties, I did enjoy the story’s themes and—once I had finally gotten used to the format—I even enjoyed the narrative itself. But the experience of reading The Queen of Erewhon was a hassle. I found myself often taking breaks throughout my reading and it felt like I was putting more work into understanding the story than actually enjoying it.

Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s Day

by Tori Truslow, 2010 Rating: ★★☆☆☆

Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s Day is more of an interesting read than it is entertaining. Tori Truslow goes at great lengths to present the narrative in the format of a biography and to incorporate passages from Shakespeare at multiple levels in the prose. She succeeded in creating a realistic description of a fictional man and his adventures through the fae world. I could easily see this faux-excerpt as coming from a full volume detailing the life of Elijah Willemot Wynn. The world was a little difficult to grasp at first, but I found myself well immersed thanks to Truslow’s decision to write her short story in a non-fiction style. It made the story feel grounded and real. My only issue with Tomorrow is Saint Valentine’s Day was the inclusion of poetry and Shakespeare, which seemed out of place to me. It’s as if Truslow wanted to offset the dry, non-fiction aspects of the story with more whimsical passages. These passages—more than anything else—broke my immersion in the narrative. I don’t think they should have been omitted though, as these poetic passages are integral to the narrative she’s woven. I just wonder if it could have been handled better; perhaps if the author of the biography had spent more time analyzing the poems and references to Shakespeare, it would feel more grounded and less eccentric.

Spider the Artist

by Nnedi Okorafor, 2011 Rating: ★★★★★

Nnedi Okorafor tackles a lot of issues in Spider the Artist: domestic violence, the exploitation of third world countries, environmentalism and machine sentience. Normally, I would find so many topics packed into a short story overwhelming. But Okorafor managed to create a relatable and realistic protagonist in Eme, to the point I felt deeply connected to Eme as she wrestled with her identity in this broken world. If I have one criticism, it is how quickly the story resolves itself; it feels as though in one moment Eme is discovering who she is, and the next she is in the middle of a war. I don’t think the strength of Spider the Artist is the issues it tackles or the ideas it presents. Instead, it is strongest when we get to live life through Eme’s eyes. As such, I wish we could have spent more time with her. I would be interested in reading more from Okorafor, especially if she has longer works of fiction.

Link to Short Story

The Science of Herself

by Karen Joy Fowler, 2013 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

The Science of Herself is an interesting read—even leading me to research further into Mary Anning following my reading. However, the frequent name drops and descriptions of pre-Victorian era England bored me. I am not a fan of historical fiction, so this just wasn’t for me. Also, while I think it’s important to highlight people like Mary Anning lest we forget what she and other women in history have done, I don’t think stuffing thirty persons into a short story is the best way to do so, especially if the reader is unfamiliar with the subject matter.

Link to Short Story

The Other Graces

by Alice Sola Kim, 2010 Rating: ★★★★☆

The best part of The Other Graces is its inclusion of wacky, weird and wonderful science fiction shenanigans—specifically, in the form of a multidimensional, time-travelling network of singular consciousness which inhabits the minds of two versions of the protagonist for the purpose of ensuring the future of the younger protagonist, while simultaneously allowing the narrator to speak to the reader and the protagonist. And surprisingly, this multidimensional consciousness is rarely the focus of attention. There are some clues as to the ethical implications of using such a technology, and it is used at times as a metaphor for mental health issues, but these themes are glossed over in favour of plot. I feel that Alice Sola Kim handled all of this well, as it can be easy to be swept up in the majesty of one’s own conceptualization; too often I see entire storylines devoted to explaining how the author’s futurology would function and how it would impact society. The Other Graces manages to introduce an otherworldly concept like multidimensional consciousness while focusing on character, anchoring the reader in what would otherwise be a strange experience.

I also appreciated the way Kim presented Grace and her life as a person of Asian descent living in poverty. In some instances, I felt she may have over-characterized how downtrodden Grace was in her attempt to reset expectations about lower-class Asian-Americans. I understand that the fetishization of the exotic and status prejudice are big issues for minority groups; racists seem to think that people of different cultures are simultaneously privileged, yet inferior to them. However, I find this kind of negative language off-putting, as if unhealthy habits and subpar living conditions are a mark of pride for the character. There is no shame in what we can’t reasonably control, but doesn’t mean we can’t strive to be better. Grace certainly feels she can do better for herself; I just wish less time was spent on self-depreciation. I understand that others may be able to identify with her self-loathing, but it may also help to normalize negativity in like-minded readers.

Boojum

by Elizabeth Bear & Sarah Monette, 2008 Rating: ★★★★☆

Boojum is a combination of the familiar and the surreal, meant to dazzle and confuse, to entertain yet left wanting more. I don’t have a lot to say beyond the fact it’s a great example of what a short story should strive for. Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette weave an interesting, futuristic take on Lovecraftian and pirate lore—two genres of speculative fiction I have had a long-time love-hate relationship with. I’ve always enjoyed the aesthetics of Lovecraft, but could never get past how ridiculous and pompous it is. By the same token, I enjoy the aesthetic and romance of pirate stories, but I sometimes feel that authors rely too much on nautical know-how to carry the narrative rather than good characterization. My criticisms of these subgenres could also be applied to Boojum, though to a lesser extent. I think what saves Boojum to me is its excellent pacing and narrative structure, focusing on the way Black Alice interacts with the world, rather than having the story focus on the world itself. And so I can look past some of my issues to enjoy Boojum for what it is: a fun space-pirate story with minor horror elements.

Link to Short Story

The Eleven Holy Numbers of the Mechanical Soul

by Natalia Theodoridou, 2014 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

The Eleven Holy Numbers of the Mechanical Soul skirts the edge between surreal and survival thriller, dipping its toes in both genres without commiting to either. I found the references to holy numbers and the fluctuating perspectives more distracting than compelling; it felt as though the author was trying too hard to add a mystical element to the story, in an attempt to elevate the story beyond being just science-fiction. It also never felt as though anything was at stake, with survival elements acting more as padding than anything compelling. Part of me wonders if this was all intentional, as if Natalia Theodoridou wants the reader to ask questions rather than just passively experiencing the story. Where exactly is Theo? Is he on a habitable planetoid? Are the machines sentient? Or are they just machinations of Theo’s engineering mind? Is he waiting for something? Will someone ever come? These questions are an undercurrent to the events in the story, and are what occupied my thoughts following my reading. However, there’s little substance to the story itself. In my opinion, Theodoridou excels at building a rich world around her characters, but I was not a fan of how she structured her narrative.

Link to Short Story

Mountain Ways

by Ursula K. Le Guin, 1996 Rating: ★★★★★

Unfortunately, I never had much exposure to Ursula K. Le Guin in my childhood, and it’s only recently that I’ve begun to hear how much she has contributed to literature. Her talent is obvious in Mountain Ways; after what I felt was a rocky start, I was fully immersed in her story. She places the focus on the characters, and the way they interact and change with the world, rather than on the world itself. Characters act like real people, with goals, flaws, worries and emotions. The world feels real and makes sense within the rules set by Le Guin. My only criticisms lie in the story’s beginning and ending. While I understand the necessity of explaining the complex marriage practices of the culture in Mountain Ways, I’m always wary when an author feels the need to address the reader directly regarding their world’s lore. It should instead be understood naturally through the interactions between characters, as they navigate their world and come to understand it. Although, her warning regarding the complexity of the ki’O’s marriage practices is well-founded; I often found myself confused when it came to marriage terminology, especially once genders were falsified. As for the ending, the conflict felt forced and unresolved. It’s as if the narrative could not end without some kind of conflict—as though Le Guin did not feel confident enough in her characters being influenced by anything but spurned love or misplaced anxiety. I felt betrayed that Shahes became so emotional, stubborn and unreasonable towards the end—especially after displaying such conviction, passion and determination up until then. Her stubbornness seems like a natural extension of her character, but she quickly became shallow and unlikable.

Perhaps this change in Shahes was what Le Guin was aiming for from the beginning. The change in narrative focus from Shahes to Enno/Alka is evidence of this. Beginning as a secondary character, Enno/Alka slowly turns into the protagonist, while simultaneously growing closer to the other members of their sedoretu and experiencing a rift with Shahes. I believe this change in focus is what kept me invested in the story, as I quickly latched onto Enno/Alka where previously I had difficulty feeling connected to Shahes near the beginning.

I also think Le Guin made the right choice in how she directly addresses sexuality and gender identity. In the world of O, the people inhabiting therein are bound together by marriage. Homosexuality seems accepted—even encouraged—and pre-marital sex is common practice. However, people are still expected to marry for the purpose of reproduction, with individuals expected to couple with a man and woman in a four-way relationship. As is the case with most stories worth being told, the main cast of characters seek to subvert these established laws through deception. While the events in the story are certainly interesting and help to build drama, there’s also a clear contrast with the gender politics and discussions of sexuality of our modern world. Mountain Ways reminds us that no matter how open and accepting your society might be, there will always be people who push the limits of what’s acceptable in the name of free love. It also reminds us that deception in relationships is difficult on individuals, and what may seem like a good idea in theory, is much more difficult in practice. I think it’s important that Le Guin does not preach free love as infallible, and helps to make Enno/Alka likeable, as they walk the line between wanting to follow their heart and following their beliefs. They are not bound by conviction, but by morality and reason.

Despite my issues with Mountain Ways’ beginning and ending, Ursula K. Le Guin lives up to her reputation by immersing the reader in her world almost effortlessly, while offering us the chance to explore important topics like sexuality and gender identity through excellent world-building. She demonstrates the power of science-fiction: the power to convey a message and discuss issues through metaphor, without being muddied by the social politics of the modern world.

Link to Short Story

Tan-Tan and Dry Bone

by Nalo Hopkinson, 1999 Rating: ★★☆☆☆

I’ll begin by saying that the dialect Nalo Hopkinson chose for Tan-Tan and Dry Bone wasn’t for me. It made it difficult for me to become immersed in the narrative from the beginning all the way to the end. I thought the dialogue—which used the same dialect—was excellent. It felt authentic, and I could listen to an entire play or film with characters speaking in this manner. However, I was quickly fatigued by the dialect’s use in the narrative, leading to me having to repeatedly re-read passages to make I understood what was going on. That being said, I did enjoy Tan-Tan and Dry Bone for what it was. Unfortunately, I didn’t get as much out of it as I think someone familiar with African culture would. To me it was a simple folktale with the purpose of representing African culture, while simultaneously conveying a message of hope for women caught in abusive relationships.

The Four Generations of Chang E

by Zen Cho, 2011 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

The Four Generations of Chang E attempts to tackle real world issues through metaphor and allegory—in this case, the issues of immigration, segregation and personal identity. I think Zen Cho tackles these issues with a grace that points to a familiarity born from experience, or at least from close study of them. However, I found the story to be rather boring overall and the metaphors a bit on the nose. Characters also felt flat and one-dimensional; caricatures of actual people rather than real people onto themselves. The focus is placed on social issues, leaving the rest of the story feeling rushed, hollow and unfinished. I can appreciate how Cho used science fiction for tackling these important issues, but I could not get immersed in the narrative itself.

Stay Thy Flight

by Elisabeth Vonarburg, 1992 Rating: ★★☆☆☆

Stay Thy Flight has a very rough opening few paragraphs. The beginning third or so presents a very difficult barrier of entry, as the author uses punctuation and fragmented phrases to represent how time passes faster for the protagonist than for the reader, before said reader has even had the chance to understand what’s happening. The sequence also lasts longer and contains more intense descriptions than I think is necessary to convey the theme of how time is fleeting. In fact—in fear of what I may have to put myself through—I even read ahead to see if I was in for a long, difficult read under this format. If I had met this story outside of this collection, I most likely would have stopped reading it after the first or second paragraph for this reason alone. Even though I love the themes that Elisabeth Vonarburg conveys, all I wanted was to finish and move on as quickly as possible. It’s a shame, since Stay Thy Flight is an excellent piece of fiction and could have stood on its own, without the need for such extravagant prose.

As an aside, I tried to find the French version of this story—titled ...suspends ton vol—but unfortunately, I could not find it published stand-alone online. It is only available as part of French short story collections, which I am not ready to purchase or find in a bookstore for the sake of my curiosity. However, I would have liked to read Stay Thy Flight in its original format, to see if the opening felt more organic in Vonarburg’s native tongue.

Astrophilia

by Carrie Vaughn, 2012 Rating: ★★★★★

Perhaps it’s a testament to the skill that Carrie Vaughn and Ursula K. Le Guin hold in writing fiction, but I feel I am quickly becoming a fan of the “lesbian farmer” trope. Astrophilia reminds me a lot of Le Guin’s entry in this collection, and Vaughn manages to capture my interest with her romance just as Le Guin was able to weave a story full of wonder, internal conflict and change. If I am honest, homosexual relationships in rustic environments have always been of particular interest to me. I think what pulls me to this trope is the atmosphere, combined with the inherit rebelliousness that the characters must adopt to make their relationship work. It’s thrilling and endearing at the same time. Add on the expectation that people must raise children once they are of age in these kinds of settings, and the field is laid out for compelling storytelling.

The romance between Stella and Andi embodies the best of this trope, and Vaughn seems to have a knack for writing a compelling romance on top of it all. I was fully invested in both characters, and the final conflict had me on the edge of my seat. I was a little disappointed in how things were wrapped up though. It felt less like an authentic conversation between adults, and more of a sermon from the author to the reader on the moral of the story. I wasn’t convinced by Toma’s change of heart; it’s not that I think a more violent end would have been more appropriate, but I feel as though Stella could have convinced him without trying to appeal to a belief he had had instilled in him since his childhood. I’ve never known someone to change their mind that suddenly, especially when they have been repeatedly challenged before. However, the rest of the story was superb, and I must also mention that I appreciate that the main source of conflict is not the topic of homosexuality itself; Vaughn chose to subvert the expectation that stories with homosexuality must ultimately contain conflict surrounding the sexuality of its characters, often ending in violence. While stories depicting the difficulties homosexual people face everyday is important, it’s also important to depict people existing outside of their sexual identity.

Link to Short Story

Invisible Planets

by Hao Jingfang, 2013 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

I think what I most disliked about Invisible Planets was its format, in that it is simply a collection of worldbuilding concepts. Invisible Planets goes so far as to separate each world into its own section, with some commentary between the narrator and a surrogate for the reader (as the narrator addresses “you” throughout the story, and “you” respond). I do not know what the intent Hao Jinfang had when writing Invisible Planets. The structure feels uninspiring and bland. The exchange between the narrator and “you” near the end of the story feels similarly uninspired, and mystically nonsensical. There was no narrative here, only a collection of ideas. While that can be fine on its own, to me it feels lazy and unfinished. It’s the equivalent of going up to a writer or director at a convention and telling them you have this great idea, but you haven’t done any actual writing. You only wrote down the idea, dusted your hands and said “Yup, that’s good.” before moving onto the next project. Each world Jingfang presents to us is interesting enough on its own to warrant in-depth exploration, but instead she chooses to present them as flat canvases with which she expects us to paint our own narrative. Invisible Planets feels like a step back from what makes science fiction literature unique—in that it can explore themes and stories untethered by the weight of the real world. What it is instead is a synopsis for a series of pulp fiction novels from the 1940’s.

Link to Short Story

On the Leitmotif of the Trickster Constellation in Northern Hemispheric Star Charts, Post-Apocalypse

by Nicole Kornher-Stace, 2013 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

From the outset, it was clear to me that On the Leitmotif of the Trickster Constellation in Northern Hemispheric Star Charts, Post-Apocalypse would be one of those stories that relied as much on flowery language as it did on weaving a compelling narrative. Combined with textbook-style prefaces, Nicole Kornher-Stace manages to craft the pinnacle of pretentiousness. It’s a shame because the story has a magnificent world and interesting characters behind all of its presentation. Kornher-Stace’s use of poetic prose and textbook-style elements confuses what ends up being a rather simple story. It’s an inspiring, deeply moving story. But I could not bring myself to care as I had to move through a veil of fog before I could enjoy it. There are times where unique formats can help to elevate a story, to enhance the message it is trying to convey. Most of the time—when an author attempts to deliver their story in a unique way—they are either experimenting or are crying for attention. I do not know which is the case for On the Leitmotif of the Trickster Constellation in Northern Hemispheric Star Charts, Post-Apocalypse, but either way, the format Korher-Stace chose detracts from the overall experience. If anything I think this story would work well as a quest in an RPG, wherein in the player would learn the fragmented history of the world through exploration, and Wasp’s character through gameplay. But it just fails in its current format to be a worthwhile piece of fiction.

Valentines

by Shira Lipkin, 2009 Rating: ★★★★★

Shira Lipkin was able to convincingly sell what it’s like to live in the mind of a person trying to make sense of their world through the act of recording everything on paper. Acting almost like a computer, the protagonist has to constantly write down and then index things around her. I came out of Valentines thinking a lot about the human condition and how we think. It’s a simple story, but it conveys its message well. Lipkin has a good sense of detail, focusing on elements that put us in the mind of the protagonist, even if you don’t have experience with epilepsy or memory loss yourself.

Dancing in the Shadow of the Once

by Rochita Loenen-Ruiz, 2013 Rating: ★★☆☆☆

I found Dancing in the Shadow of the Once boring, as it suffers from the issue of presenting a problem, waiting for the reader to solve it and then having the characters enact the solution long after the reader has already decided what the solution should be. The problem in this case is whether Hala should stop being a cultural historian for the amusement of the colonist elite, and the solution is her no longer being in this position. As a reader, it becomes obvious in the latter half of the story that she will follow this path, all that remains is to know how she will get there. I found this tedious as the character walks methodically to the resolution, with no new developments along the way. Rochita Loenen-Ruiz also falls into a trap I often see accompanying this kind of storytelling problem: she withholds information, or only provides enough characterization to further the plot and then retroactively develops the character in the hopes of keeping things ambiguous or mysterious. I find this writing technique shows a lack of faith in the author’s own work, which didn’t help my already low opinion of the story. The only thing that kept me interested were the story’s themes of colonialism and imperialism, that were unfortunately not as prominent as I would have liked. I also enjoyed the discussions around the culture, as few as they were. Finally, one of the strongest moments in the story is the dance between Hala and Bayninan, as it becomes clear that Bayninan has romantic feelings for Hala. It’s a shame the rest of the story does not live up to the emotional impact of this moment.

Ej-Es

by Nancy Kress, 2010 Rating: ★★★★★

There’s just something about living life through a character’s perspective for a short time, to see the world as they do, to hear their thoughts, feel their doubts and experience their pain. Nancy Kress succeeds at this in Ej-Es. I was captivated throughout my reading, feeling as though I knew Mia on an intimate level, even though I only spent a short time with her. She felt like a real person; a woman tired of protocol, far from where she first began but still holding onto what she values the most. She knows her place in the world and how to navigate it, and yet comes off as vulnerable all the same. Kress managed to craft a compelling character piece, while simultaneously commenting on missionary work and how it impacts indigenous people. Kress writes wonderfully, conveying a compelling story with realistic characters and immersive narration.

Link to Short Story

The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees

by E. Lily Yu, 2011 Rating: ★★★☆☆

The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees surprised me, in that E. Lily Yu manages to weave a rather compelling fairy tale, seemingly creating it wholecloth from nothing; or at least, I have never heard of this specific folktale before. It has some of the familiar trappings of fairy tales: whimsical creatures, talking animals and a morally good ending. There’s also a good amount of commentary on imperialism and politics, without the topics being forced down the reader’s throat. The only thing I’m not too sure about is what part the anarchist bees have in the story. They don’t seem to have any impact on the story; in fact, everything is resolved without the bees doing anything at all to secure their freedom. The only explanation I have is the story must be based on real-life events of which I’m not familiar with, or its implied that while the anarchists did not survive, their ideologies will live on in this hive’s society to inform decisions in the future. Either way, I can’t shake the feeling that Yu is making reference either to either historical events or an existing fable. If this is an isolated work, free from influence, then there’s a lack of clarity and consistency in the story, with too much left up for the reader to interpret. In either case, The Cartographer Wasps and the Anarchist Bees is a great fable-like story that shows that simple, concise stories often work best to convey an author’s message.

Link to Short Story

The Death of Sugar Daddy

by Toiya Kristen Finley, 2009 Rating: ★★★★☆

I was on edge for a good part of The Death of Sugar Daddy, mostly due to the way people in the story would refer to Sugar Daddy. I felt he would end up being a pedophile or some kind of undying being—both of which may still be the case, but I’m not convinced one way or the other. This rising sense of dread transformed into a feeling of heartfelt anticipation as more and more of the world spilled out, slowly building a picture of a world wherein memory is intrinsically tied to existence. Toiya Kristen Finley does an amazing job of building the world through her characters; the protagonist and supporting characters help to build the world without acting as walking exposition dumps, with defined personalities and lives outside the context of the plot. Finley proves to me once again that character-driven narratives are the best vehicles for worldbuilding, as they allow the reader to discover the world organically instead of academically.

I also liked that Finley was able to convey African-American culture without over-the-top social commentary. There was still some underlying social commentary about the wealth disparity of African-Americans in the western world, but it was never anything significantly overt. I can normally appreciate social commentary in fiction, but the character-driven narrative of The Death of Sugar Daddy allows the characters to experience this wealth inequality instead of preaching to the reader. It’s refreshing to have something that makes you think about the issue from a human perspective instead of a political one.

Link to Short Story

Enyo-Enyo

by Kameron Hurley, 2013 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆

Some parts of Enyo-Enyo are genuinely interesting, and I think the underlying story is emotionally impactful, if not a little strange. However, any positive elements the story may have are overshadowed by its presentation—more specifically, the choice in vocabulary and the story’s narrative structure. From the first three or four paragraphs, it’s made clear to the reader that Enyo’s world is alien. This would normally be a good thing, but Kameron Hurley goes too far, and ended up alienating me with how “other” Enyo’s world is. And while I don’t have an issue with the non-linear timeline of events, it only helped to compound these issues here, making it even more difficult for me to follow what’s happening. Enyo-Enyo is a simple story told in a complicated manner—very rarely is this kind of storytelling effective, and often paints the author as pompous and shallow. It’s a shame, because I think I would have liked Enyo-Enyo if Hurley had written in a more straightforward manner.

Link to Short Story

Semiramis

by Genevieve Valentine, 2011 Rating: ★★★☆☆

The easiest way for me to sum up Semiramis is to say that it instills a feeling that something is about to happen, or that some change is about to occur, but the reader is ultimately left at the precipice of anticipation, without anything ever being resolved. I didn’t like this at first. The protagonist-narrator would always seem on the cusp of making some kind of realization before moving onto the next bit of exposition or the next source of conflict. As a result, all of the events muddle together—with no beginning, no end. But as I reflected on what Genevieve Valentine might be trying to do, I came to my own realization that a feeling of helplessness is exactly what she was trying to convey. Between the global climate crisis and the protagonist’s struggle with their duties, environment and relationships, I underwent a general feeling of unease as the events of the story unfolded. It’s almost depressing as you come to the conclusion that sometimes, things are just out of your control, and all you can do is little things to make your life worth living. The world is cruel, unforgiving and need not pay mind to every individual. Not all conflicts come to a satisfying end, and waiting for something to happen will only lead to more anxiety as time moves on without regard for each individual’s desires.

I am still unsure whether I truly enjoyed Semiramis. Despite the message she was trying to convey, I had a difficult time initially remembering the contents of the story within a day of writing this. Perhaps the effects of the story were stronger than the actual fiction, and that should point to the power of what she was trying to do.

Link to Short Story

Immersion

by Aliette de Bodard, 2012 Rating: ★☆☆☆☆