#cerveza orval

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

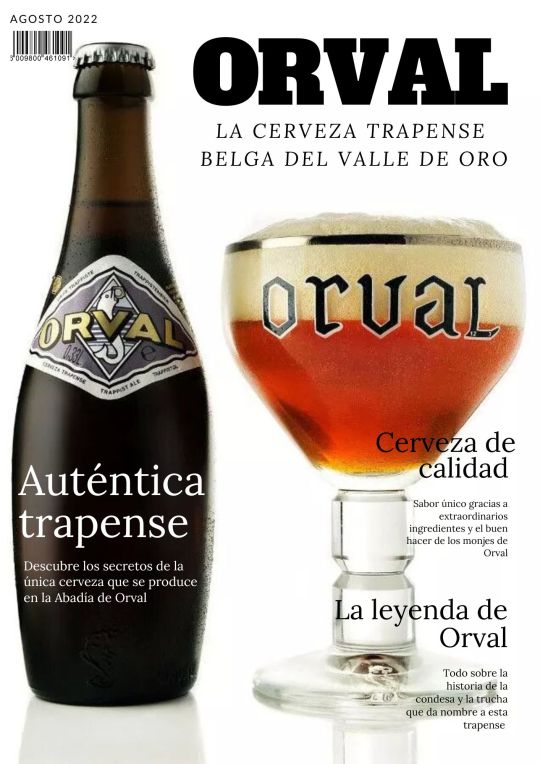

Orval es la única cerveza que se elabora en la cervecería d la Abadía de Orval. Esta trapense es considerada una de las mejores cervezas belgas, con una puntuación de 99/100 en Ratebeer.Esta Pale Ale se elabora con malta pálida y una pequeña cantidad de malta caramelo.

Se utilizan lúpulos Hallertau, Styrian Goldings y Strisselspalt para el amargor y el aroma. Su proceso de maduración le añade un toque frutal, además de un gran equilibrio y complejidad. El resultado es una extraordinaria cerveza de aroma y sabor únicos.

El diseño de la Abadía de Orval también es digno de mención. Esta fue diseñada por el arquitecto Henry Vaes y se construyó sobre las ruinas de la anterior abadía. Vaes también diseñó la botella de Orval y su copa.

https://www.bodecall.com/blog/orval-cerveza-trapense-belga/

#orvault#cerveza orval#orval beer#biere orval#cerveza belga#biere belge#cerveza trapense#trappist beer#orval

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Hva Såå !? (Mikkeller - Danemark) - grâce à “Mikkeller Beer Mail” -

“Our tribute to the mighty Orval! Notes of belgian yeast and what the beer geeks call funk presents itself to the nose. Flavors are of a yeasty backbone, a tad of spice and lingering bitterness from the hops.”

“Notre hommage à la puissante Orval ! Des notes de levure belge et ce que les geeks de la bière appellent funk se présentent au nez. Les saveurs balancent entre le caractère de la levure, un soupçon d'épices et l’amertume persistante du houblon.”

Hva såå !? = Alors quoi !?

#biere#bière#beer#Bier#cerveza#cerveja#birra#öl#olut#øl#boisson#drink#Danemark#Denmark#Danmark#alorsquoi#Hvasåå#Orval

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cerveza Orval, clásica entre las clásicas, es una cervecería trapista belga situada en los muros de la Abbaye Notre-Dame d'Orval en la región Gaume de Bélgica. La cervecería produce dos cervezas, ambas con el sello de autenticidad trapista llamadas Orval y Petite Orval. Aunque el monasterio es anterior la fábrica actual es del siglo XX y la receta de la cerveza es de 1931. Se distingue del resto de cervezas trapistas por inusual sabor y aroma producido por una cepa de levadura, Brettanomyces lambicus. Cerveza con lúpulos de la variedad Hallertau, Styrian Goldings y Strisselspalt, este último de origen francés. Un gran clásico entre las cervezas trapenses. País: Bélgica Estilo: Abadía Alc: 6.2% La etiqueta de la cerveza muestra una trucha con un anillo de oro en la boca, y rinde homenaje a la leyenda en la que se inspira la fundación de la Abadía de Orval. #retobeer #cerveza #cervezaartesanal #cervezas #birra #beer #beerlover #beerstagram #beertime #cerveja #bier #cervesetatime #bier #biere #starköl #pivo #cervezaartesana #cervesa #ipa #ipalover #øl #ipafan #ipabirra #trapa #trapense — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/CgTH6W5

0 notes

Photo

Cerveja Orval - Bret Ale - Cervejaria Brasserie d'Orval - ABV: 6.2% . Ame ou odeie ! No meu caso, paixão !!! 🍺🍺🍺🍺🍺 . Cerveja exótica de cor âmbar, levemente turva, ótima formação de espuma e estabilidade. Aroma e sabor de notas animalescas e selvagem intenso da levedura. Amargor médio-baixo. Corpo médio-baixo. Boa carbonatação. Final seco. Bom drinkability. . . #beerme #beer #beerporn #beers #beerstagram #instabeer #beergeek #beerlover #craftbeer #craftbeers #cerveja #cervejadeverdade #cervejeirov8 #breja #bebamenosbebamelhor #sommelier #sommelierdecerveja #fanaticbeer #beeroftheday #cheers #cervejaartesanal #craftbeerporn #craftbeerlover #bier #birra #cerveza #invasãocervejeira #invasaocervejeira #unidospelacerveja #beersnob (em Casa da Família Mopar)

#unidospelacerveja#craftbeerporn#cerveza#instabeer#beers#breja#cervejeirov8#cervejaartesanal#invasaocervejeira#cervejadeverdade#craftbeerlover#beerporn#beer#cheers#sommelierdecerveja#birra#beersnob#fanaticbeer#beerme#beerstagram#craftbeer#beeroftheday#bebamenosbebamelhor#craftbeers#cerveja#bier#invasãocervejeira#beergeek#sommelier#beerlover

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bastogne Pale Ale #bastogne #paleale #belgianipa #belgium #beerporn #beer #bier #birra #cerveza #beermoment #beertime #instabeer #beerstagram #malt #malto #water #acqua #lievito #yeast #luppolo #hop #brewery #orval #belleau #vauxsursure

#instabeer#beerstagram#malt#brewery#beerporn#beertime#malto#acqua#paleale#hop#belgianipa#beer#lievito#cerveza#bastogne#beermoment#orval#luppolo#yeast#birra#belgium#belleau#vauxsursure#bier#water

0 notes

Text

¿Te gusta la cerveza?ABADIA ORVAL es para ti.

¿Te gusta la cerveza?ABADIA ORVAL es para ti.

ABADIA ORVAL – BÉLGICA

<img data-attachment-id="1888" data-permalink="http://www.levoyagedunpapillon.com/2017/05/te-gusta-la-cervezaabadia-orval-es-para-ti/img_4301-jpg/" data-orig-file="http://www.levoyagedunpapillon.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/img_4301.jpg" data-orig-size="3717,3024" data-comments-opened="1" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"2.2","credit":"","camera":"iPhone…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

112 Orval

Une trappiste belge très réputée qui m’a beaucoup déçue. A retester...

http://www.orval.be/en/8/Brewery https://www.ratebeer.com/beer/orval/835/ http://www.lantredebiere.com/biere-orval-c2x20762173

0 notes

Text

¿Sabías que Orval es la única cerveza que produce la cervecería del monasterio de Orval? además, esta cerveza trapense se produce con una cepa de levadura única que le aporta su aroma y sabor tan característicos.

Con una puntuación casi perfecta de 99/100 en Ratebeer, es considerada por muchos una de las mejores cervezas del mundo

Más sobre esta cerveza belga en nuestro blog 👉 https://www.bodecall.com/blog/orval-cerveza-trapense-belga/

#orval#cerveza trapense orval#cerveza belga orval#cerveza belga#cerveza online#cerveza#bier#beer#biere

0 notes

Text

Puerto Rican Craft Brewers Are Jumping Hurdles to Catch Up With the Mainland

As recently as five years ago, the terms “craft beer, “microbrew,” or even “cerveza artisanal” were not commonplace in Puerto Rico. They still aren’t: Costly import taxes, regulatory roadblocks, and natural disasters make running any business here challenging, let alone one most Puerto Ricans don’t see as a necessity.

But thanks to establishments like La Taberna Lúpulo bar in Old San Juan, recognition of small-batch brewing is growing. To enter Lúpulo, meaning “hop” in Spanish, is to encounter the unexpected: Coolers are stuffed with the likes of Orval, and taps flow with Bell’s Hopslam. Co-owner Zalika Guillory has worked hard to get the most sought-after mainland craft brands and Trappist imports from Europe. Mostly, though, she wants to show off local brands, which she pours on 40 to 60 percent of the bar’s 38 taps.

“It’s important for Puerto Ricans to know people here are contributing [to the beer scene] and doing it in a way that’s uniquely Puerto Rican,” Guillory says. Lúpulo, along with the island’s 13 craft breweries, is doing just that.

While Guillory and a handful of fellow publicans are properly serving and promoting their island’s offerings, owners of craft breweries here struggle mightily to compete with imports and the commonwealth’s main mass-produced lager, Medalla Light.

“The U.S.-based craft products brought down to the island are way cheaper to produce,” Juan Cruz, owner of Zurc Bräuhaus Craft Beers brewery in Caguas, says. “And paperwork is time consuming in multiple orders of magnitude higher than it should be.”

Puerto Rican brewers incur prohibitive expenses to get supplies onto the island and to distribute beer to 5,000 licensed retail outlets within its borders. Adding to their troubles, small brewers contend that public officials, used to dealing with “big pharma” and — before it moved off-island — big agriculture, remain suspicious and restrictive toward small businesses like theirs.

To craft their Helles lagers, passion fruit IPAs, and coffee stouts, Puerto Rican brewers have to import nearly every ingredient, including grains and hops, as well as equipment. No inputs, save for some fruit and vegetable adjuncts, grow locally.

THE HIGH COST OF DOING BUSINESS

On top of normal freight costs comes the Jones Act, signed in 1920, which requires that all goods shipped between U.S. ports be transported on vessels that are built, owned, and operated by U.S. citizens. This creates a scenario where shipping companies can charge higher rates because of lack of competition. Thus, a cottage brewer on a U.S. island looking to procure modest orders of Idaho barley and hops pays an elevated price to have those ingredients shipped (one study found it costs twice as much to ship a container to Puerto Rico from Florida than from a foreign port). Add an 11.5 percent port tax, and beer gets pricey real quick.

Still, Lúpulo’s Guillory says a standard keg (15.5 gallons) of California’s Russian River costs $180 in states where it’s sold, while liquid made in San Juan can carry up to a $160 price tag per sixtel (5.16 gallons). Why? Guillory says Puerto Rico pays more than mainlanders for transportation, fuel, water, electricity, and interest rates. “And in terms of keeping beer cold, we’re in the tropics,” she says.

This partially explains why, according to wholesaler Joey Maldonado, local brew only comprises 1.2 percent of Puerto Rico’s beer market, which Cruz says translates to $17 million in annual economic impact. This contribution is in stark contrast to mainland states. Even Wyoming, which reaps less from its craft brewing industry than any other state, posted a $192.6 million direct contribution last year.

Despite the nearly negligible competition, the big guys are playing the price-war game to maintain dominance. “You can find Medalla at one buck, Heineken, two for $3,” says Maldonado, who sells crafts and locals through a distributor called Ballester Hermanos. “I’ve never seen that before.”

Representatives for Medalla didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Brewers did get some relief last summer, when former governor Ricardo Rosselló signed an excise tax reduction into law. Put into effect Oct. 1, the new law drops the per-gallon tax from an exorbitant $2.55 to $0.95. Cruz, who led lobbying efforts for the bill, hopes the new rate will raise annual economic impact to $261 million. “It’s a step into the right direction and will give us a fairer competitive profit margin versus imported products,” he says.

The bill succeeded because in a unique display of solidarity, 11 craft brewers formed a loose association in 2018, and seven producers later brewed their first collaboration to raise money to fund some of their lobbying activities.

TACKLING REGULATORY HURDLES

In the summer of 2017, Jose Luis Diaz Vazquez and his wife, Sarahil Nieves, spent their life savings to upgrade the cramped 2.5 barrel nano-brewery they own in their mountainous hometown of Utuado. Two months later, in September 2017, Hurricane Maria hit. “We lost everything that we had,” he says. “We lost all the beer, grains, hops, and all four fermenters. We were prepared for everything except a disaster like this.”

Despite long stretches without electricity, water, telecommunications, a working generator, or access in and out of town, the owners of REBL Brewery produced a batch of beer within two months. Then, Diaz Vazquez says, “In May 2018, things were sort of back to normal. In November 2018, we were seeing things getting better.”

Then, in December of 2018, “Hacienda gave us another hurricane,” Diaz Vazquez says, referring to Departamento de Hacienda, Puerto Rico’s tax agency regulating alcohol production. Hacienda shut REBL down for three months while the agency updated its accounting system, according to Diaz Vazquez.

Two emails requesting comment from Hacienda went unanswered.

“When we finally got approved, we had to dump what was in the fermenter,” Diaz Vazquez says. Given that Hacienda agents have to be on site whenever product gets packaged or leaves the building, and that they hold the keys to open locked fermenters, timing can be critical. Multiple brewers say that they have been forced to dump spoiled batches waiting for agents to visit.

But as the aftermath of Hurricane Maria showed, Puerto Ricans are nothing if not optimistic and scrappy, and no breweries closed permanently because of the storm — or due to regulatory hurdles. As craft breweries emerged from the literal muck to present post-storm beers, bar owners have shown gratitude and loyalty. Diaz Vazquez says patrons of one bar cheered when he delivered the first keg of his flagship, Kasiri IPA, in early 2019.

Rhaiza Casiano Pabón, of the Cabo Rojo-based brewery Pura Vida, says when she hosts bar events, her beer sells out in less than two hours. Pura Vida, like most of the others, doesn’t have a tasting room, and none of Puerto Rico’s craft breweries can yet afford to sell on the mainland. So for now, the success of Puerto Rico’s craft breweries is totally reliant on local support. “The bars [here] try to give us an opportunity,” Pabón says. “They are open minded to the fact that people want to try craft beers.”

The article Puerto Rican Craft Brewers Are Jumping Hurdles to Catch Up With the Mainland appeared first on VinePair.

Via https://vinepair.com/articles/puerto-rican-craft-beer/

source https://vinology1.weebly.com/blog/puerto-rican-craft-brewers-are-jumping-hurdles-to-catch-up-with-the-mainland

0 notes

Text

Puerto Rican Craft Brewers Are Jumping Hurdles to Catch Up With the Mainland

As recently as five years ago, the terms “craft beer, “microbrew,” or even “cerveza artisanal” were not commonplace in Puerto Rico. They still aren’t: Costly import taxes, regulatory roadblocks, and natural disasters make running any business here challenging, let alone one most Puerto Ricans don’t see as a necessity.

But thanks to establishments like La Taberna Lúpulo bar in Old San Juan, recognition of small-batch brewing is growing. To enter Lúpulo, meaning “hop” in Spanish, is to encounter the unexpected: Coolers are stuffed with the likes of Orval, and taps flow with Bell’s Hopslam. Co-owner Zalika Guillory has worked hard to get the most sought-after mainland craft brands and Trappist imports from Europe. Mostly, though, she wants to show off local brands, which she pours on 40 to 60 percent of the bar’s 38 taps.

“It’s important for Puerto Ricans to know people here are contributing [to the beer scene] and doing it in a way that’s uniquely Puerto Rican,” Guillory says. Lúpulo, along with the island’s 13 craft breweries, is doing just that.

While Guillory and a handful of fellow publicans are properly serving and promoting their island’s offerings, owners of craft breweries here struggle mightily to compete with imports and the commonwealth’s main mass-produced lager, Medalla Light.

“The U.S.-based craft products brought down to the island are way cheaper to produce,” Juan Cruz, owner of Zurc Bräuhaus Craft Beers brewery in Caguas, says. “And paperwork is time consuming in multiple orders of magnitude higher than it should be.”

Puerto Rican brewers incur prohibitive expenses to get supplies onto the island and to distribute beer to 5,000 licensed retail outlets within its borders. Adding to their troubles, small brewers contend that public officials, used to dealing with “big pharma” and — before it moved off-island — big agriculture, remain suspicious and restrictive toward small businesses like theirs.

To craft their Helles lagers, passion fruit IPAs, and coffee stouts, Puerto Rican brewers have to import nearly every ingredient, including grains and hops, as well as equipment. No inputs, save for some fruit and vegetable adjuncts, grow locally.

THE HIGH COST OF DOING BUSINESS

On top of normal freight costs comes the Jones Act, signed in 1920, which requires that all goods shipped between U.S. ports be transported on vessels that are built, owned, and operated by U.S. citizens. This creates a scenario where shipping companies can charge higher rates because of lack of competition. Thus, a cottage brewer on a U.S. island looking to procure modest orders of Idaho barley and hops pays an elevated price to have those ingredients shipped (one study found it costs twice as much to ship a container to Puerto Rico from Florida than from a foreign port). Add an 11.5 percent port tax, and beer gets pricey real quick.

Still, Lúpulo’s Guillory says a standard keg (15.5 gallons) of California’s Russian River costs $180 in states where it’s sold, while liquid made in San Juan can carry up to a $160 price tag per sixtel (5.16 gallons). Why? Guillory says Puerto Rico pays more than mainlanders for transportation, fuel, water, electricity, and interest rates. “And in terms of keeping beer cold, we’re in the tropics,” she says.

This partially explains why, according to wholesaler Joey Maldonado, local brew only comprises 1.2 percent of Puerto Rico’s beer market, which Cruz says translates to $17 million in annual economic impact. This contribution is in stark contrast to mainland states. Even Wyoming, which reaps less from its craft brewing industry than any other state, posted a $192.6 million direct contribution last year.

Despite the nearly negligible competition, the big guys are playing the price-war game to maintain dominance. “You can find Medalla at one buck, Heineken, two for $3,” says Maldonado, who sells crafts and locals through a distributor called Ballester Hermanos. “I’ve never seen that before.”

Representatives for Medalla didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Brewers did get some relief last summer, when former governor Ricardo Rosselló signed an excise tax reduction into law. Put into effect Oct. 1, the new law drops the per-gallon tax from an exorbitant $2.55 to $0.95. Cruz, who led lobbying efforts for the bill, hopes the new rate will raise annual economic impact to $261 million. “It’s a step into the right direction and will give us a fairer competitive profit margin versus imported products,” he says.

The bill succeeded because in a unique display of solidarity, 11 craft brewers formed a loose association in 2018, and seven producers later brewed their first collaboration to raise money to fund some of their lobbying activities.

TACKLING REGULATORY HURDLES

In the summer of 2017, Jose Luis Diaz Vazquez and his wife, Sarahil Nieves, spent their life savings to upgrade the cramped 2.5 barrel nano-brewery they own in their mountainous hometown of Utuado. Two months later, in September 2017, Hurricane Maria hit. “We lost everything that we had,” he says. “We lost all the beer, grains, hops, and all four fermenters. We were prepared for everything except a disaster like this.”

Despite long stretches without electricity, water, telecommunications, a working generator, or access in and out of town, the owners of REBL Brewery produced a batch of beer within two months. Then, Diaz Vazquez says, “In May 2018, things were sort of back to normal. In November 2018, we were seeing things getting better.”

Then, in December of 2018, “Hacienda gave us another hurricane,” Diaz Vazquez says, referring to Departamento de Hacienda, Puerto Rico’s tax agency regulating alcohol production. Hacienda shut REBL down for three months while the agency updated its accounting system, according to Diaz Vazquez.

Two emails requesting comment from Hacienda went unanswered.

“When we finally got approved, we had to dump what was in the fermenter,” Diaz Vazquez says. Given that Hacienda agents have to be on site whenever product gets packaged or leaves the building, and that they hold the keys to open locked fermenters, timing can be critical. Multiple brewers say that they have been forced to dump spoiled batches waiting for agents to visit.

But as the aftermath of Hurricane Maria showed, Puerto Ricans are nothing if not optimistic and scrappy, and no breweries closed permanently because of the storm — or due to regulatory hurdles. As craft breweries emerged from the literal muck to present post-storm beers, bar owners have shown gratitude and loyalty. Diaz Vazquez says patrons of one bar cheered when he delivered the first keg of his flagship, Kasiri IPA, in early 2019.

Rhaiza Casiano Pabón, of the Cabo Rojo-based brewery Pura Vida, says when she hosts bar events, her beer sells out in less than two hours. Pura Vida, like most of the others, doesn’t have a tasting room, and none of Puerto Rico’s craft breweries can yet afford to sell on the mainland. So for now, the success of Puerto Rico’s craft breweries is totally reliant on local support. “The bars [here] try to give us an opportunity,” Pabón says. “They are open minded to the fact that people want to try craft beers.”

The article Puerto Rican Craft Brewers Are Jumping Hurdles to Catch Up With the Mainland appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/puerto-rican-craft-beer/ source https://vinology1.tumblr.com/post/189684171034

0 notes

Text

Portal Cervecero: La Cerveza de Abadía

Seguramente cuando hablamos de cerveza, se te viene a la mente inmediatamente barriles, pero sobre todo un monje elaborándola, pues déjame decirte que durante mucho tiempo y hace algunos siglos, esta bebida se hacía en monasterios y abadías. Sin embargo dentro de esta clasificación de cerveza, existen las cervezas trapenses o trapistas y estas sonlas cervezas elaboradas en los monasterios trapenses y pueden denominarse "trapenses". En algunos casos estas cervezas se hacen en monasterios o abadías que en el pasado elaboraban cerveza y que ahora encargan a algún productor no vinculado a la iglesia que se la produzca. También es común utilizar el nombre de alguna iglesia o santo para dar nombre a la cerveza. Pero en el caso de los monjes que elaboran cerveza en la actualidad, estos son de la orden Trapista y de ahí el nombre.

La cerveza de abadía se elabora basándose en las antiguas recetas que los monjes han sabido conservar hasta nuestros días. Durante la Edad Media, la cerveza era considerada más un alimento que una bebida, por lo que su elaboración y cuidado tenía un importante valor para la supervivencia de los pobladores de las abadías y de los pueblos aledaños. Algunas abadías belgas elaboran todavía estas cervezas ancestrales y han sido los monjes trapenses los que con más celo han guardado las recetas. En este tipo de cerveza se suelen encontrar denominaciones de doble o triple. Estas etiquetas no se refieren al número de fermentaciones realizadas. Las cervezas de abadía fermentan habitualmente en fermentadores durante unos 15 días, continuando la misma en los llamados tanques de guarda. Después vuelven a obtener una fermentación en botella; por lo que desarrollan 2, 3 o 4 fermentaciones, dependiendo de si contamos el tiempo pasado en el tanque como una nueva fermentación o no. En cualquier caso podemos contar con 2 fermentaciones, Las llamadas dobles suelen ser tostadas y las triples rubias.

Requisitos para una cervecería Trapense:

Para que una cerveza sea trapense debe reunir tres requisitos fundamentales:

1.-La cerveza debe ser elaborada tras los muros de una abadía trapense y por monjes trapenses, o bajo su control directo.

2.-La cervecería debe depender del monasterio y ser parte del proyecto monástico.

3.-La cervecería no obtendrá beneficios. Una parte de estos ingresos se destina a los monjes de abadía, mientras que el resto se destina a obras de caridad. Además, la publicidad debe respetar el sentido religioso en el que se elabora la cerveza.

Los estilos básicos de las cervezas trapistas son:

Blonde

Dubbel

Tripel

Quadrupel

Actualmente, 12 cervecerías en el mundo están etiquetadas como trapenses, seis en Bélgica: Achel, Chimay, Rochefort, Orval, Westmalle y Westvleteren; dos en Holanda: La Trappe y Zundert; una en Austria: StiftEngelszell; une en Italia: TreFontane; y la única integrante fuera de Europa: Spencer Saint Joshep, en Estados Unidos. Las botellas llevan el logotipo que las autentifica como Autentico Producto Trappense (AutenticTrappistProduct).

Así pues, ninguna otra cervecería que no sea una de las once ya mencionadas puede elaborar cerveza trapense. Es frecuente, no obstante, que algunas cervecerías intenten imitar los estilos de cerveza asociados a los Monjes trapenses En ese caso, las cervezas se denominan “de abadía”.

Estas cervezas son una excelente opción para estas fechas, te invitamos a probarlas.

Gustavo Aguilar e Ivan Arellano. No.1107. 301118

0 notes

Text

RT @cervezadviernes: La Cerveza del Viernes: Orval. Style: Belgian Pale Ale. Trappist. Alc. 6,2% Vol. 33cl. IBU’s 36 Brewery: Brasserie d`Orval #villersDevantOrval #Luxembourg #Belgium @nazo_da2 @RedStripeRocco @IanStew55902399 @beeryeti @HopticalA @JaNaGaLl @Rubengzamora @gabrigargar @kaluapiscis https://t.co/QibJhXQb0v

La Cerveza del Viernes: Orval. Style: Belgian Pale Ale. Trappist. Alc. 6,2% Vol. 33cl. IBU’s 36 Brewery: Brasserie d`Orval#villersDevantOrval #Luxembourg #Belgium@nazo_da2 @RedStripeRocco @IanStew55902399 @beeryeti @HopticalA @JaNaGaLl @Rubengzamora @gabrigargar @kaluapiscis pic.twitter.com/QibJhXQb0v

— Cerveza del Viernes (@cervezadviernes) October 19, 2018

via Twitter https://twitter.com/OKasionalBeer October 19, 2018 at 09:50PM

0 notes

Photo

Blueblackbeige2k13 /// @kontorasuto_ #vscocam #vsco #art #artistsoninstagram #artist #artwork #draw #drawing #illustration #black #blackwork #blackandwhite #bw #minimal #minimalism #minimaldrawing #minimalart #fukboi #ink #hashtag #ZθMBΨIПK #pk #kontorasuto #plant #cigarette #dotwork #ok (à Orval (cerveza))

#vsco#ok#minimal#blackandwhite#artist#zθmbψiпk#artwork#hashtag#vscocam#bw#black#blackwork#dotwork#drawing#plant#art#cigarette#minimalart#minimaldrawing#minimalism#draw#kontorasuto#artistsoninstagram#fukboi#illustration#pk#ink

0 notes