#central america and south america are different continents.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

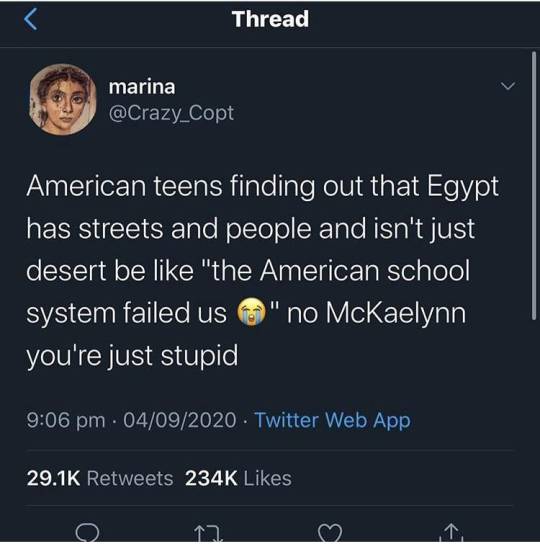

Text

People have asked me if brazil is like. Forest cabins with wild animals walking around.

Sure there's capybaras that live in the riverbank that runs along one of São Paulo's biggest avenues, but like. Avenues. With buildings. The subway. Literally landscaped like New York.

#also there is one or another comic that places mayan pyramids in the amazon rainforest.#not even the same continent my dude.#central america and south america are different continents.#meh#brazil mentioned#sort of

110K notes

·

View notes

Text

Euphorbia euphoria

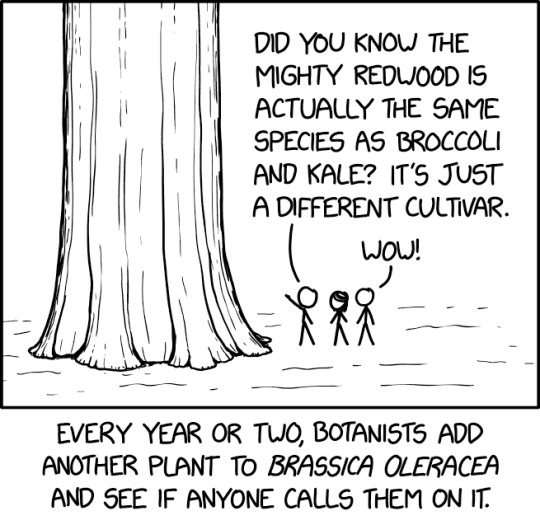

Was sent this by a friend:

which is a reference to this:

namely, the fact that the wild mustard Brassica oleracea, once domesticated, produced a bewildering variety of vegetables by selecting each cultivar for a different part (cabbages from terminal buds, Brussels ssprouts from lateral buds, broccoli and cauliflower from flower buds, kale from leaves, and so on), all of them still being technically part of the same species, Brassica oleracea var. whatever.

Now, as far as I know, nobody has bred B. oleracea into a tree. But there is, not quite a single species, but a genus, that has gotten pretty close to that kind of internal morphological diversity:

Behold Euphorbia, the genus of spurges, counting over 2000 species (that nevertheless are often capable of interbreeding) scattered throughout all continents:

Euphorbia dendroides (Mediterranean)

The poinsettia, Euphorbia pulcherrima (Central America)

Euphorbia actinoclada (East Africa)|, one of the many cactus-like species (cacti proper are all American species except one, so if you see a cactus-like plant in an African or Asian deserts, odds are it's actually a kind of euphorbia)

Euphorbia trigona (Central Africa)

Euphorbia myrsinites (Southeast Europe)

Euphorbia obesa (South Africa)

Euphorbia ferox (South Africa)

Euphorbia ampliphylla (East Africa) (source)

Euphorbia aphylla (Canary Islands)

Euphorbia helioscopia (Eurasia and Africa)

And so on, and so on...

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

re: latinoamerican/hispanic/south american discourse

out of nowhere but i see this often enough online and it bugs me

people fight because the terms latino, south-american, and hispanic, all mostly overlap but the definitions are slightly different and exclude slightly different people.

South-America: Countries from the South American continent. Does not include Mexico and Central America.

Hispanic: Countries and people that speak Spanish. Includes Spain, does not include Brazil.

Latino: This one is the trickiest because the definition is a bit vague, and that creates conflict. Mostly, latinoamerican countries mean the ones conquered by Spain and Portugal, so Mexico and everything south of it. No, I know French is a latin language but it does not include the French colonies (source: I'm from Québec. We do not consider ourselve latinos. Only pedantic people in Youtube comments use this as a gotcha.)

Mostly, it means a culture, but that's also tricky because even though there are similarities, of course Mexico and Chile won't have the same culture. And as I understand, the Carribean coutries are even more unique, but there's a history of racism in the latino community that tends to exclude them and that's not cool. And of course, Indigenous people can decide to call themselve latinos if they want to, or not, and that's alright.

So, you have this mass of countries, cultures, and people, that do have similar traits, but are also different enough to argue about everything. Just ask them what is the word for a drinking straw.

I think the problem is that the world tends to put us all in the same basket. Africa has to live with that too, but I'm starting to hear more and more "Ok but which African country, you can't just say someone is 'from Africa'". And I feel like people understand now that "the Orient" is not a thing and I do see people say that all Asian countries are not the same. Of course there's still a long way to go, but I don't even hear that when talked about Latinoamerica.

And! Mostly, what enrages me, is that we are not kind between ourselves, or with our diaspora! Every day I see comments saying you're not a real latino of you don't speak perfect Spanish, if you don't dance, if you can't recognize a bachata from a salsa, if this, if that.

Colonization, slavery, and then US imperialism fucked up most of our countries, installing dictators and fucking up the economy. Of course you will have a massive exile, and our people will be spread across the world. Of course you will have second generations immigrants that only have what their parents taught them for crumbs of the culture. Of course you will have children that will struggle to speak Spanish because they don't use it everyday, and calling abuelita once a month is not enough to keep a language.

These immigrants, these children, will be told all their lives that they don't belong to the country they now live in. Please don't tell them they don't belong in the culture they had to leave too.

What I mean with all this: The world brushes off too easily, and we deserve to be treated with more respect. But before we come to that, we need to respect each other, and celebrate our differences instead of using them to determine who is and who isn't part of the club.

There may be a lot of differences between me, a pale skinned, black haired, Chilean immigrant in Québec who speaks mostly French; and a Black Puerto Rican who lived in their country their whole life; and a white and blonde Mexican who now lives in the US but still grew up in Quintana Roo; and kids all over that don't really care for their parent's music or food because they got their own things going on; and people who struggle to learn and keep Spanish and Portugese.

But if we decide to all call ourselves latinos, then that's what we are, and that means we're family.

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

In English, North America and South America are two different continents but in Spanish they’re just one continent and continents are a made up concept and what constitutes as a continent has no useful definition that fits all of our regular lists of continents and why are Europe and Asia and Africa three different continents in the first place and is Australia actually just a very big island?

Anyways that’s why I don’t type things like USAmerican because in English they’re just Americans but I understand why some people do get annoyed with that but at the same time I’ve seen zero Spanish speakers in my personal life argue for speaking that way in English and I guess my point is that we should probably be more aware of how certain people see themselves and be respectful of that but also at the same time I’m an English speaking person in an English speaking country and if I use America to refer to what we call The Americas in my everyday life people will assume I’ve made a mental typo or that I’m being contrarian and if I tried to make that a thing in my everyday speech patterns I’d come off as a pretentious idiot. If I’m speaking Spanish that’s a different story. Then yeah there’s other words for US Americans like estadounidense. Or famously gringo, more colloquially.

I’m not looking to start arguments here. Like I said I totally get why people make that distinction. But there’s also like the nuances of the lived reality of living in certain cultural contexts that I think people forget about.

I’m not here to tell you to not make that distinction in your speech. I’m not even here to tell you that you’re not allowed to be frustrated about it. I’m just here to explain why I don’t do that and why most English speaking people don’t and why it’s not inherently malicious when people do. Like if someone fully dismisses your perspective on the issue and how you view your own identity yes they’re the asshole. But also generally in English it’s The Americas or North, Central, and South America. And yes maybe that’s stupid but so is the existence of Europe as a concept and we all seem to believe that Europeans are a real thing.

And to reiterate. I’m not trying to tell anybody how to speak or how to feel here. Just trying to insert some nuance into this conversation. Because people I call Americans and you might call USAmericans are only gonna call ourselves Americans. That’s just how we view ourselves, how we understand our own identity as a nation. And some people will be jerks about it. But many of us are also just living in the world we live in, referring to ourselves in the way we always have, not aiming to tell anyone else how they ought to view themselves.

I’m American. Soy estadounidense. Some stuff unfortunately gets lost in translation.

Also continents don’t exist. If we try to get rid of the concept of continents we’d all be too confused at all times to have these disagreements. Confusion superiority. We go by tectonic plates. California is on the same continent as Japan now.

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

some notes on specifically "middle eastern" (mashriqi + iran, caucuses, and turkey) jewish communities/history:

something to keep in mind: judaism isn't "universalist" like christianity or islam - it's easier to marry into it than to convert on your own. conversions historically happened, but not in the same way they did for european and caucasian christians/non-arab muslims.

that being said, a majority of middle eastern jews descend from jewish population who remained in palestine or immigrated/were forced (as is the case with "kurdish" jews) from palestine to other areas and mixed with locals/others who came later (which at some point stopped). pretty much everywhere in the middle east and north africa (me/na) has/had a jewish population like this.

with european jews (as in all of them), the "mixing" was almost entirely during roman times with romans/greeks, and much less later if they left modern-day greece/italy.

(none of this means jewish people are or aren't "indigenous" to palestine, because that's not what that word means.)

like with every other jewish diaspora, middle eastern jewish cultures were heavily influenced by wherever they ended up. on a surface level you can see this in things like food and music.

after the expulsion of jews from spain and portugal, sephardim moved to several places around the world; many across me/na, mostly to the latter. most of the ones who ended up in the former went to present-day egypt, palestine, lebanon, syria, and turkey. a minority ended up in iraq (such as the sassoons' ancestors). like with all formerly-ottoman territories, there was some degree of back and forth between countries and continents.

some sephardim intermarried with local communities, some didn't. some still spoke ladino, some didn't. there was sometimes a wealth gap between musta'arabim and sephardim, and/or they mostly didn't even live in the same places, like in palestine and tunisia. it really depends on the area you're looking at.

regardless, almost all the jewish populations in the area went through "sephardic blending" - a blending of local and sephardic customs - to varying degrees. it's sort of like the cultural blending that came with spanish/portugese colonization in central and south america (except without the colonization).

how they were treated also really depends where/when you're looking. some were consistently dealt a raw hand (like "kurdish" and yemenite jews) while some managed to do fairly well, all things considered (like baghdadi and georgian jews). most where somewhere in between. the big difference between me/na + some balkan and non-byzantine european treatment of jews is due to geography - attitudes in law regarding jews in those areas tended to fall into different patterns.

long story short: most european governments didn't consider anyone who wasn't "christian" a citizen (sometimes even if they'd converted, like roma; it was a cultural/ethnic thing as well), and persecuted them accordingly; justifying this using "race science" when religion became less important there after the enlightenment.

most me/na and the byzantine governments considered jews (and later, christians) citizens, but allowed them certain legal/social opportunities while limiting/banning/imposing others. the extent of both depend on where/when you're looking but it was never universally "equal".

in specifically turkey, egypt, palestine, and the caucuses, there were also ashkenazi communities, who came mainly because living as a jew in non-ottoman europe at the time sucked more than in those places. ottoman territories in the balkans were also a common destination for this sort of migration.

in the case of palestine, there were often religious motivations to go as well, as there were for some other jews who immigrated. several hasidic dynasites more or less came in their entirety, such as the lithuanian/polish/hungarian ones which precede today's neutrei karta.

ashkenazi migration didn't really happen until jewish emancipation in europe for obvious reasons. it also predates zionism - an initially secular movement based on contemporaneous european nationalist ideologies - by some centuries.

most ashkenazi jews today reside in the us, while most sephardic or "mizrahi" jews are in occupied palestine. there, the latter outnumber the former. you're more likely to find certain groups (like "kurds" and yemenites) in occupied palestine than others (like persians and algerians) - usually ones without a western power that backed them from reactionary antisemitic persecution and/or who came from poorer communities. (and no, this doesn't "justify" the occupation).

(not to say there were none who immigrated willingly/"wanted" to go, or that none/all are zionist/anti-zionist. (ben-gvir is of "kuridsh" descent, for example.) i'm not here to parse motivations.)

this, along with a history of racism/chauvinism from the largely-ashkenazi "left", are why many mizrahim vote farther "right".

(in some places, significant numbers of the jewish community stayed, like turkey, tunisia, and iran. in some others, there's evidence of double/single-digit and sometimes crypto-jewish communities.)

worldwide, the former outnumber the latter. this is thought to be because of either a medieval ashkenazi population boom due to decreased population density (not talking about the "khazar theory", which has been proven to be bullshit, btw) or a later, general european one in the 18th/19th centuries due to increased quality of life.

the term "mizrahi" ("oriental", though it doesn't have the same connotation as in english) in its current form comes from the zionist movement in the 1940s/50s to describe me/na jewish settlers/refugees.

(i personally don't find it useful outside of israeli jewish socio-politics and use it on my blog only because it's a term everyone's familiar with.)

about specifically palestinian jews:

the israeli term for palestinian jews is "old yishuv". yishuv means settlement. this is in contrast to the "new yishuv", or settlers from the initial zionist settlement period in 1881-1948. these terms are usually used in the sense of describing historical groups of people (similar to how you would describe "south yemenis" or "czechoslovaks").

palestinian jews were absorbed into the israeli jewish population and have "settler privilege" on account of their being jewish. descendants make up something like 8% of the israeli jewish population and a handful (including, bafflingly, netanyahu and smoltrich) are in the current government.

they usually got to keep their property unless it was in an "arab area". there's none living in gaza/the west bank right now unless they're settlers.

their individual views on zionism vary as much as any general population's views vary on anything.

(my "palestinian jews" series isn't intended to posit that they all think the same way i do, but to show a side of history not many people know about. any "bias" only comes from the fact that i have a "bias" too. this is a tumblr blog, not an encyclopedia.)

during the initial zionist settlement period, there were palestinian/"old yishuv" jews who were both for zionism and against it. the former have been a part of the occupation and its government for pretty much its entire history.

some immigrated abroad before 1948 and may refer to themselves as "syrian jews". ("syria" was the name given to syria/lebanon/palestine/some parts of iraq during ottoman times. many lebanese and palestinian christians emigrated at around the same time and may refer to themselves as "syrian" for this reason too.)

ones who stayed or immigrated after for whatever reason mostly refer to themselves as "israeli".

in israeli jewish society, "palestinian" usually implies muslims and christians who are considered "arab" under israeli law. you may get differing degrees of revulsion/understanding of what exactly "palestine"/"palestinians" means but the apartheid means that palestinian =/= jewish.

because of this, usage of "palestinian" as a self-descriptor varies. your likelihood of finding someone descendent from/with ancestry from the "old yishuv" calling themselves a "palestinian jew" in the same way an israeli jew with ancestry in morocco would call themselves a "moroccan jew" is low.

(i use it on here because i'm assuming everyone knows what i mean.)

samaritans aren't 'jewish', they're their own thing, though they count as jewish under israeli law.

#jewish#mizrahi#palestinian jews#info#my posts#repost with more info#sorry if this isn't the best time to post it (?) then again this is my blog and i'm not indebted to anyone so (shrugs)#i've been seeing a lot of misinfo too so

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

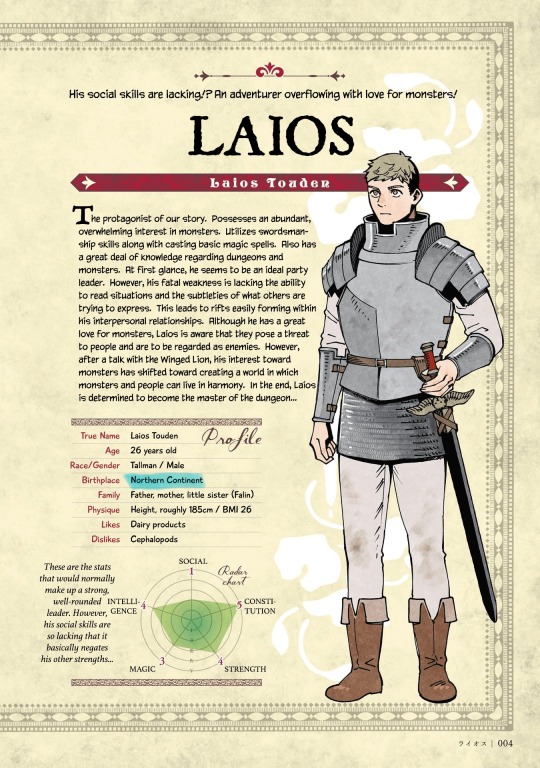

gonna be annoying about dumb world building shit for 5 seconds ok so

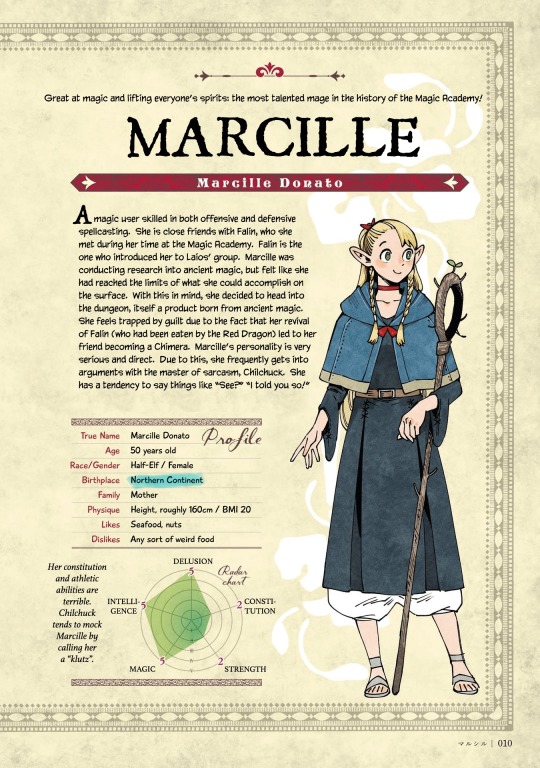

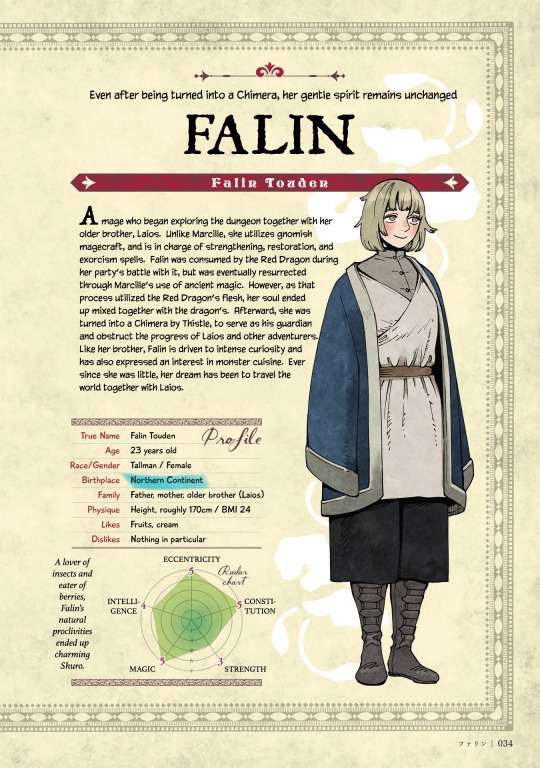

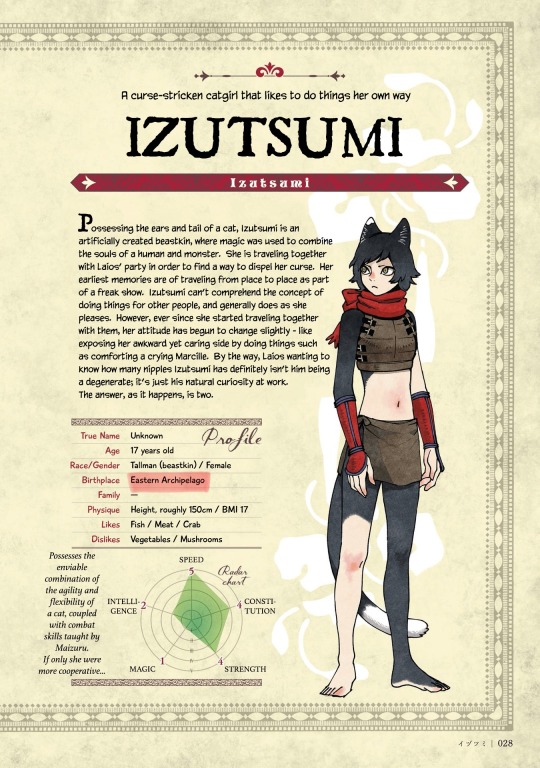

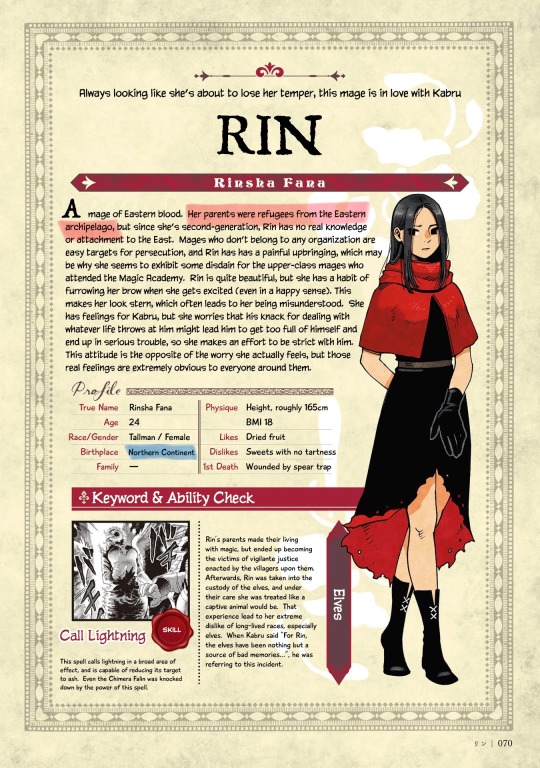

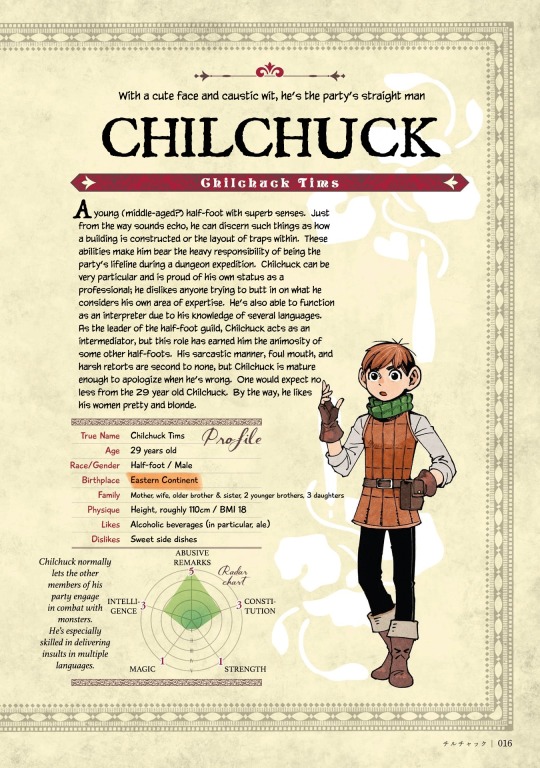

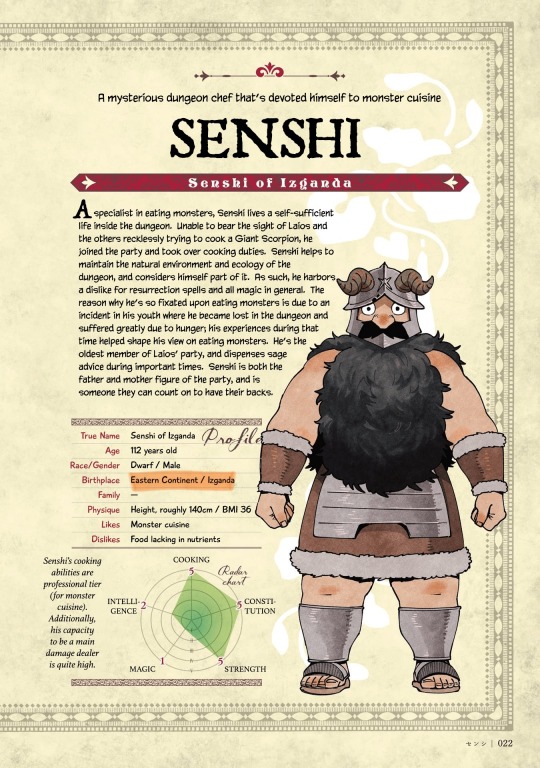

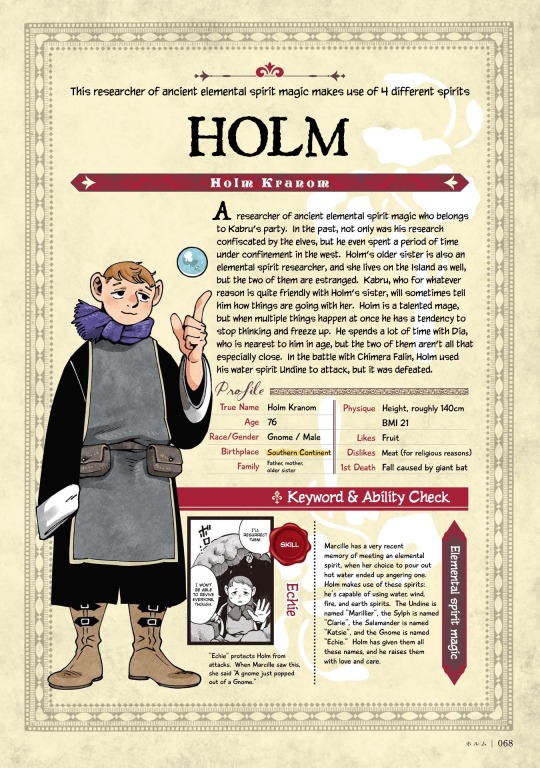

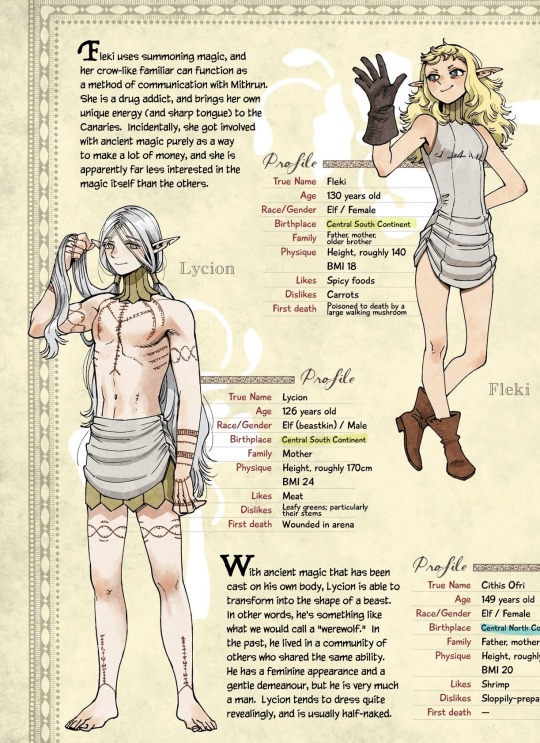

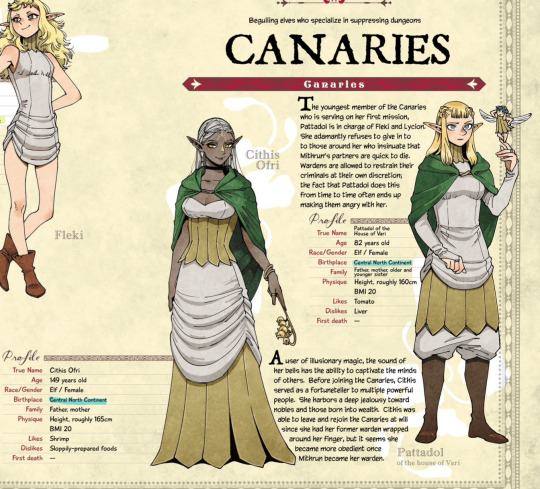

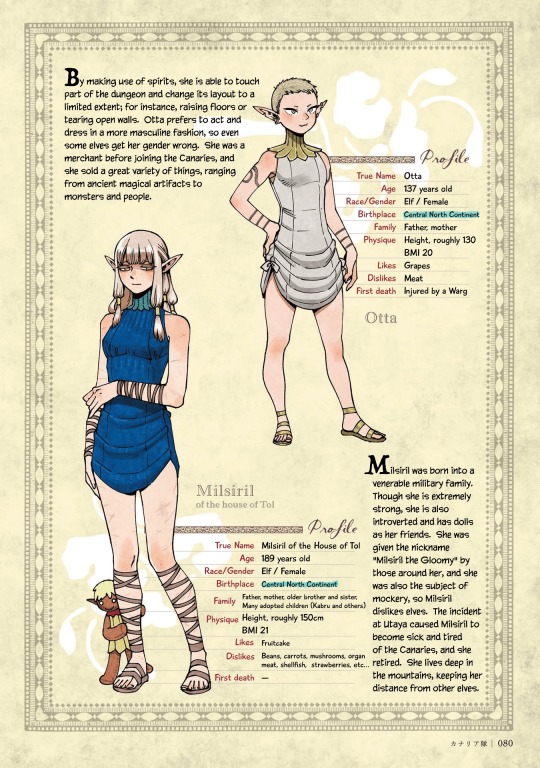

The northern continent is pretty clearly Europe, Marcille is Italian, and I think it’s sort of implied that Falin and Laios are like. Scandinavian?

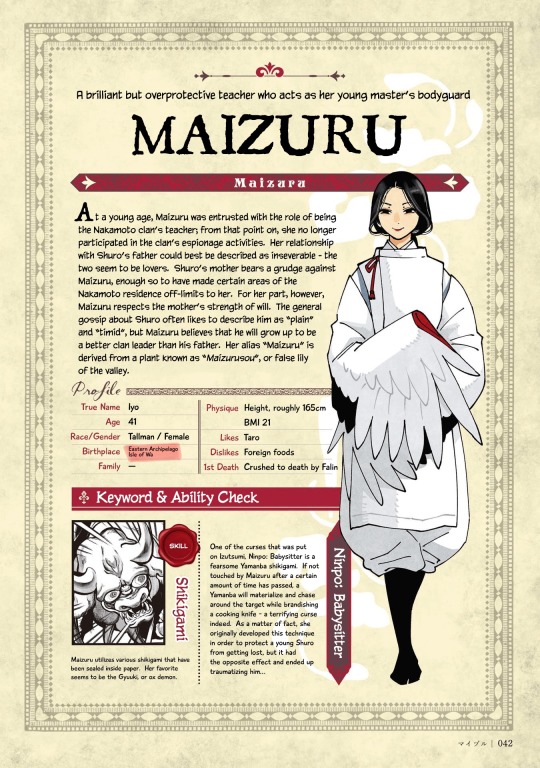

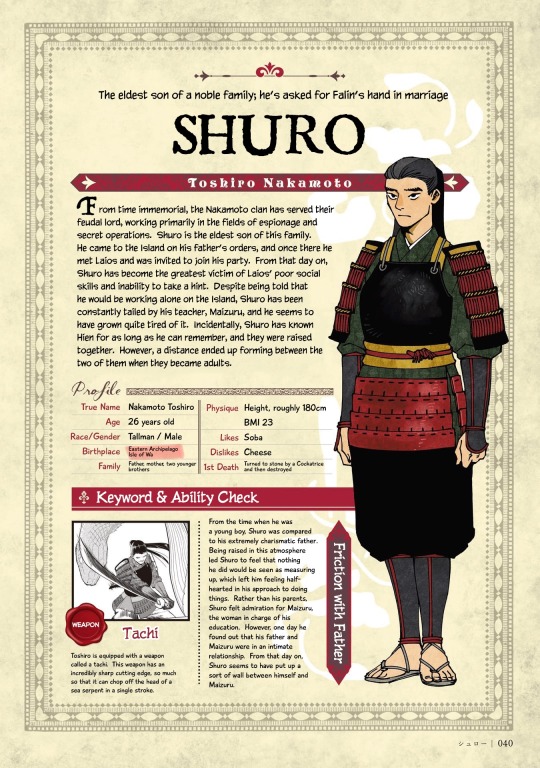

And the eastern archipelago is pretty clearly East Asia. The isle of wa, based on its cultural food, is probably Japan.

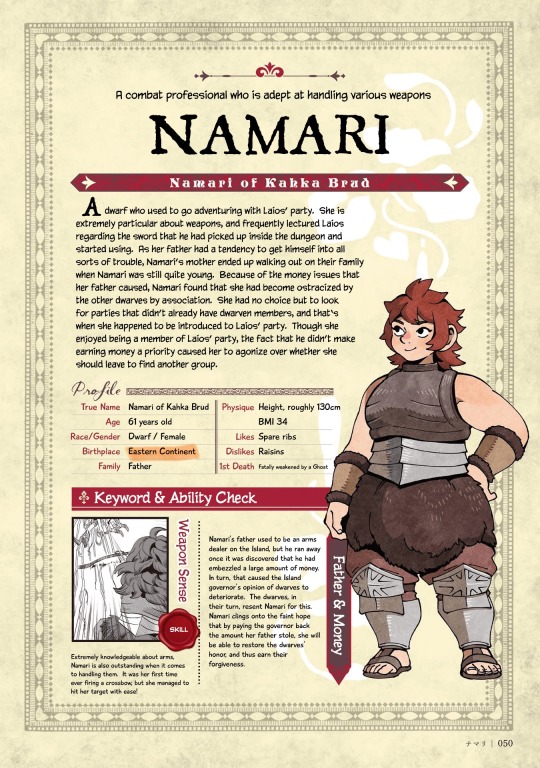

So I assume the eastern continent all of Asia? A lot of people see Senshi as West Asian, so that would check out. Namari and Chilchuck are also presumably from some area of Asia.

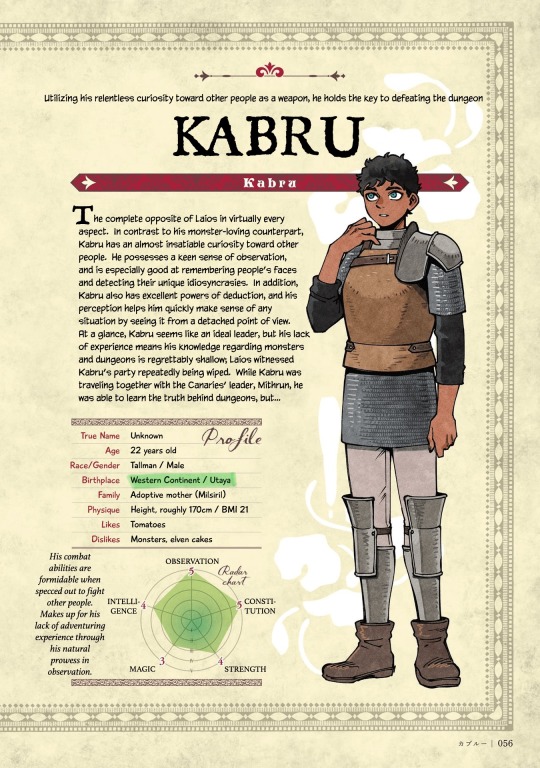

The western continent could be Africa or maybe Oceania?. I saw a theory that Kabru was South Asian, but since that would be included in the Eastern continent I’m not sure anymore.

Southern continent, I’m not sure. I could see that being North America? That’s a total guess, though.

Central Northern continent is probably equivalent to Central/Eastern Europe, I could see that.

Anyways that’s just my interpretation, if you have a different interpretation please please share it please I love world building I love correlating fantasy geography to real geography.

74 notes

·

View notes

Note

Feel like dropping the rant about how "pre-written records = prehistory" is not a good way of conceptualizing history? It's not my area at all so I'm fascinated.

Hah absolutely

It’s a mix of semantics, and word connotations, and the way history gets presented, and tbh legacies of racism.

So. Part of it comes from the distinctions between the academic field and practice of history, and the academic field and practice of archaeology. The practice of history means analyzing the past through written texts and records; the practice of archaeology means analyzing the past through the material remains left behind. This is fine. It refers to the way you approach information about the past and what tools and theories you use to do so. I have no problem with this part!

Of course, it starts to get more complicated when you also have classicists (who study ancient Greek and Roman history primarily through texts but also incorporate some aspects of archaeology) and Assyriologists (ditto but for Mesopotamia), which have their roots in old-school European practices of formal education. There’s also historical archaeology, which is primarily archaeology but incorporates written records of the time and place for a fuller picture, or uses archaeology to complicate or fill gaps in the records. Historical archaeology is a practice that can be applied to any place and time with historical records, but primarily it refers to archaeology of the Americas post-European colonialism.

These refer to the ways we study the past. Where I start to disagree is when these terms get applied to the past itself.

Historians study history through written texts, so there is often a delineation where history = the presence of written texts, and prehistory = before that. And I have problems with that delineation of time.

For one thing, the connotations of the terms. History, in common use, is important, it’s everything that built the world we live in and led to where we are now. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. While prehistory conjures images of dinosaurs, or cavemen. It implies that the things that happened in it aren’t as important as the things that happened once history proper started. It also feels very, very old—it feels weird to call, say, the Inca empire prehistoric, when the Inca Empire is younger than Oxford University and the first Inca emperor was crowned in Peru after the Norman Invasion of England in 1066—something nobody calls prehistoric.

Because that brings up a more objective issue with splitting time into “history” and “prehistory”: writing was invented at different times in different places, and used to different extents. Writing was first invented in Mesopotamia in the Early Bronze Age, about 5,000 years ago. It was probably independently invented in Egypt shortly afterward, and was independently invented in China 3400 years ago, and in Central America about 2500 years ago. Writing spread across Asia, India, North Africa, Europe, and Mexico/Guatemala; it was not used in North America, South America, southern Africa, Australia, most parts of Polynesia, Micronesia, Australia, or New Zealand at all until European contact. According to the written records definition, this means history starts in very different times in these different places. Not only does this unbalance what we think of as “history” a lot, it ends up discounting or minimizing these people’s own ways of reckoning history, making their history start when Europeans arrived.

This is an incredibly dismissive way to consider whole continents’ worth of people and cultures! It turns them into a “people without history,” and implies that whatever they were doing before Europeans (or Chinese, Indians, or North Africans depending on the region, but mostly Europeans) doesn’t really matter to what happened since. If anything happened at all in that “time before history”; a common perspective of both early colonists and modern pop-history in places like the American West or Australia is that the people there have been living the exact same way for thousands of years, unchanging since the Stone Age. Only upon contact with Europeans did anything change and “history” start. This is hugely dismissive of these people’s autonomy and their past. (You’ll notice it’s a lot of people who suffer from racism who are denied the title of “history”!) It’s also just not true.

I’m an archaeologist who studies the US Southwest/Mexican Northwest region; I focus on Arizona and New Mexico in the 1000s–1400s AD. And one of the things that opened my mind so much in studying the US southwest was just how much things changed from decade to decade and century to century in the past, the same way they did anywhere else in history at this time. There was no written history in this part of the world, but what we do have is very precise tree-ring dates. Using tree rings, we can date when this or that building was built down to the precise year. And because it’s a desert, things preserve well for a long time, so we have lots of ancient tree-ring dates. Because of this, we can see how art styles, architectural styles, settlement patterns, family organization, farming practices, religion, politics, and cultural interactions changed over the past four thousand years. And we can see that they did change, and sometimes they changed slowly and sometimes they changed rapidly. People did things. They had new ideas, they formed new political organizations and adopted new religions, they came together and broke apart, they developed new art styles and new technologies, elite lineages controlled the social order until their power fractured, people moved into new places and adapted their old practices to what they found there, or developed new ones… and because of tree-rings and desert preservation, archaeologists can see it in ways we can’t in cooler and wetter environments. This is history. This is people doing things, shaping the physical and social landscape for the centuries that followed.

And of course, Pueblo and Diné and Apache and O’odham people of the Southwest have their own oral histories that overlap with these archaeological studies. This is true in many, many places that did not traditionally use writing. They can’t be discounted just because they weren’t written down.

So to me, history = writing and prehistory = before writing is a false dichotomy that’s unhelpful at best and racist at worst. To me, history starts when people become socially organized enough that they care about what happened before, what happened where, and why it’s important, and what it means. Every culture has history, whether they wrote it down or not. Studying it may not always be suited to the skillset of historians, but that doesn’t mean it’s not history.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to write European characters for Americans (and for everyone else, but especially for Americans):

Rule number one: Europe is a continent, not a country. No, European countries are not like American states. They are all totally autonomous and may be massively different even when they are neighbours. So everything I tell you might not be the case in every country in Europe or not in all parts of all countries!

-not everyone owns a car and many people prefer public transport or bicycles over driving, especially in north western Europe. Places that cannot be reached by foot exist, but are rare.

- Euros are the currency in most countries, but not in all. Im countries poorer than the EU average, Euros might be accepted, too, in richer countries they will not be. Cents and 1€ & 2€ are coins, the rest are notes. The notes don't all have the same sizes! Cash payment is favored in some parts of Europe, card in others. Debit cards are way more common than credit cards!

- Eastern European countries are way poorer than Western European ones. You see a lot of people moving west for work. People from Western Europe hardly ever move to an Eastern European country.

- In Northern and Central Europe, pretty much everyone younger than let's say 70 speaks at least a decent English. Millennials and Zoomers often also speak French or Spanish. In Southern Europe, the younger generations usually speak English, but elderly people are usually monolingual. In Eastern Europe, German and Russian are common second languages, often even more common than English.

- in an elevator, people usually lean against the walls and look into the middle. Standing in the middle and facing the door is uncommon. Unlike in America, you keep your fork always in the same hand and do not move it to the other hand during the meal.

- Northern and Western European countries have got a lot of foreign citizens. South Asians, Africans, Caribbeans and other Europeans are typical in the UK, Arabs and Africans in France, Arabs and Latinos in Spain, Africans in Italy, Turks, Poles, Arabs and Russians in Germany, Arabs and South Asians in the Nordics. Eastern European countries are way whiter and their foreign population mostly consists of people from neighbouring countries.

- some countries prefer their local cuisine, others prefer international food. If a country has got a world-famous cuisine, it probably belongs in the first category, if not in the second.

- With the exception of a few countries (Ireland, Finland and the Baltics), football is the number one sport. Every country has got a national professional league, but especially people from smaller countries often support a team from another country, usually from England or Spain. Women's football is way smaller than in the US and is often ignored or forgotten. Even though each of these has got at least a small fan base in Europe, you cannot expect people to know anything about NBA, NFL, NHL or MLB. Other notable team sports are handball, basketball, ice hockey and rugby, but this depends very much on the country.

- in most countries, sports clubs play a huge role, and school and especially university sports teams hardly exist.

- colleges don't really exist in most countries. If you're going for an academic degree, you'll go to a university, for other careers you'll usually get trained by your company and acquire some kind of diploma. I actually never really understood the difference between a college and a university and so do probably most people here. Studying is not free in every country, but public universities are usually very cheap and under 1000€ per year. Applications for universities are way easier than in the US and usually free. Many people go to university in their hometown. It is not common to move out from home before your early twenties, especially in Southern and Eastern Europe, unless you go studying in a different city. Students live with their parents, in a flat share, with their partner, very rarely alone or in a student's residence. They do NOT share their bedroom with anyone and fraternities or soririties in an American sense do not exist in any country I know.

- Windows can and will be opened frequently. Air conditioning is common only in the Mediterranean and is used to cool down the room, not to let fresh air in. For that purpose, we open the window.

- for distances of a few hours, Europeans either take the car or the train. You can reach every major European city by train, but this doesn't mean the train service is always good. For longer distances, flights are common.

- Germany is always less modern and the Baltics are always more modern than you expect.

- Europeans are just as political as Americans, but every country has got a great variety of different political parties, even though usually 1-3 of them dominate the political landscape. "Liberal" means "center-right" in Europe. Leftists would define themselves as socialists, social-democrats, communists or anarchists. Most countries have at least one conservative AND one extreme right party.

- You can't just fire someone for no reason in most European countries. You'll often have to pay them at least a few monthly salaries as compensation. Every country has got universal health care, though it isn't always good or accessible, and it does NOT depend on your employment. The number of sick days is not limited and even though some countries work even more hours than America, people usually can't be contacted by their employer in their free time.

- the EU is often criticised, but mostly viewed as positive. National laws may not break European law and you see EU flags on many public buildings.

- if someone owns a gun, they are a hunter, a cop, a soldier or a gangster.

- parties start and end way later than in the US. In most countries, no club will close before 3am and you don't arrive at the club before midnight. Sometimes you can party until 8 or even 10 am.

- it is common to cross an international border for shopping if products are cheaper in the other country.

- people are less religious than in America. Even in the most hardcore Catholic or Orthodox regions, you don't see shit like in the US. People there might be frantically kissing some Saint's painting, but they don't believe Jesus died for their right to own a gun or stuff.

Feel free to add some!

#writing#writing advice#how to write#writing tips#tips for writers#how to write Europeans#writers on tumblr#writing help#writing resources#writing characters

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

North American countries anon here.

No, I am not from an English-speaking country. I was taught at school about two continents: North and Sourh America. I am aware that there is a region Central America. But no continental models have Central America as a different continent. There are different conventions about continents, of course. But none of them have Americas divided into three continents. My question was about the continent North America. Whether or not you think Central America is a separate region, there is a convention about either both Americas being one continent, or North and South being two.

FYI

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

"While the North American colonists identified with the chosen people who sailed across the Atlantic to conquer the promised land, to be wrested from its unauthorized inhabitants and cleansed of their presence, the Latin American revolutionaries, in the wake of their argument with Spain, tended to denounce the genocidal practices of the conquistadores, Spanish in particular and European in general. Here too the road had been indicated by the black slaves of San Domingo who, after having broken with Napoleonic France and defeated its attempts to re-conquer it and reintroduce slavery, had assumed the Indian name of Haiti. ... Thanks to the politico-social homogeneity (strengthened by the availability of land and westward expansion) of its dominant class, and thanks also to the confinement of much of the ‘dangerous classes’ in slavery, the North American republic soon succeeded in achieving a stable structure. It took the form of a ‘master race democracy’ and a racial state, based on the rule of law within the white community and among the chosen people. The situation in Latin America was very different: between liberal beginnings and radical outcomes, the revolution had mobilized a front stamped with profound social and ethnic contradictions. Thus two contrasting ideas of liberty confronted one another: one calls to mind the English gentleman determined to dispose freely of his servants; the other ultimately refers to the struggle that had put an end to black slavery in San Domingo-Haiti.

Around 1830 the American continent presented a rather telling picture. While it had disappeared in a considerable part of Latin America, slavery remained in force in the European colonies, including British and Dutch ones, and above all in the United States. We can say that from the slave revolution onwards there developed a pent up confrontation, a kind of cold war, between San Domingo and the United States. On one side, we have a country that saw ex-slaves in power, authors of a revolution that was possibly unique in world history; on the other, a country almost always led in the early decades of its existence by slave owning presidents. ... Once the new revolutionary power had consolidated itself, it was a constant concern of the United States, where not a few ex-colonists took refuge, to overthrow or at least isolate it through a cordon sanitaire. It would be dangerous, observed Jefferson in 1799, to enter into commercial relations with San Domingo. That would result in ‘black crews’ disembarking in the United States, and these emancipated slaves could represent ‘combustion’ for the slaveholding South. On the basis of such concerns, South Carolina banned the entry into its territory of any ‘man of colour’ from San Domingo or any of the other French islands, which might in some way have been infected by the new, dangerous ideas of liberty and racial equality. Regardless of commercial exchanges, stressed influential political figures in the North American republic, by its very example the island risked challenging the institution of slavery far beyond its borders. ... Only after the end of the Civil War did the United States agree to open diplomatic relations with Haiti. But it was a move bereft of any warmth, and in fact functional for a project of ethnic cleansing. The idea, also entertained by Lincoln, of depositing on the island of black power the ex-slaves, who were to be deported from the republic that continued to be inspired by the principle of white supremacy and purity, had not yet been abandoned.

Hence a distinguished historian of slavery has appropriately warned against the tendency ‘to confuse liberal principles with antislavery commitment.’ ... Lincoln himself initially conducted the Civil War as a crusade against rebellion and separatism, not for the abolition of slavery, which could continue to survive in states loyal to central government. It was only later, with the recruitment of blacks into the Union army and hence with the direct intervention of slaves and ex-slaves in the conflict, that the civil war between whites was transformed into a revolution, conducted partly from above and partly from below, making the abolition of slavery inevitable." Domenico Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History, trans. Gregory Elliot (2011)

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do any ungulates have any meaning? Like specific types of deer?

Deer and other types of ungulates have often been used as symbols, both cross-culturally and in literature. They’re fascinating creatures with a variety of habitats that exist both in the wild and in domesticated settings, so can be used in several different ways within a narrative depending on the type of meaning you wish to convey.

For this answer, we’ll focus mainly on deer, as covering all ungulates (which includes all animals with hooves ranging from horses to hippopotami) might make this answer far, far too long.

The general symbolism of deer

If we take deer at face value, some of the first imagery that will come to mind are grace, elegance, gentleness, and innocence. They can also be alert and vigilant, with a deep, mysterious connection to the wild. For this reason, many cultures (and writers) ascribe spiritual and mystical associations with them. They can also represent a connection to the supernatural, and the otherworld.

Writers will often use them as messengers or familiars, creating a bridge between the real and the fae. They can also represent growth and rebirth, as they shed their antlers, which grow again.

The cultural significance of deer

The cultural significance of deer and other ungulates have similarities but aren’t always identical. In indigenous native groups across North America, for instance, there are different traditions and stories associated with them. The Lakota believed that deer were guides on life’s journey but could also lead men astray. The Cherokee story of the Little Deer, on the other hand, sees the Deer Spirit enacting vengeance on hunters who don’t show deer the proper respect, and hunt them needlessly.

In Celtic mythology, white stags were often messengers to the underworld, and deer could shapeshift both at will and through enchantment. Arthurian legend also had a white stag as a symbol of the hunt, representing man’s neverending quest for spiritual enlightenment. And in Germanic cultures, the deer represented both the hunt and kingship.

In Hindu mythology, the goddess Saraswati is associated with a red deer and can take its form. As the goddess of learning, red deer and their hides have also taken on this meaning. In Shinto tradition, deer are messengers of the gods, and in Chinese mythology, the Fuzhu is a mythical deer with four horns that appears during periods of flood.

Specific types of deer and their symbolism

If we look at specific types of deer, then there are some general patterns that emerge in their symbolism.

White-tailed deer are native to North America, Central America, and South America. They are often associated with purity and innocence, a connection to the spirit world, and respect for the natural order.

Red Deer are native to most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, parts of western Asia, and the Atlas Mountains of Northern Africa. They are the only living species of deer to live on any part of the African continent. They have associations with royalty and kingship, as well as the hunt. They are often used on coats of arms as a symbol of nobility.

Reindeer (Caribou) have close connections to winter due to our modern Christmas traditions. But they also have great cultural significance in Arctic and subarctic cultures. They are native to the Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. They are known for their endurance and adaptability, as well as safe journeying and strength in harsh conditions.

Fallow Deer are known as peaceful and gentle. They are widespread in England, Wales, Ireland and southern Scotland but are an introduced species. Some studies suggest they are only native to Turkey. The fallow deer is probably what you picture when someone says the words “doe-eyed.” They are associated with grace and beauty and often appear in post-Norman mediaeval literature.

Moose (Elk) are considered symbols of strength, resilience, and adaptability. They are large, with imposing antlers which is what makes them such an iconic image. They are native to North America, Canda, and Northern Eurasia, but they are also associated (by name only) with the Irish Elk, an extinct giant deer known for the enormous span of its antlers (a disproven urban legend claims that the Irish Elk went extinct because its antlers grew too wide and heavy for its head and neck to support it).

How deer are used in certain genres

In Fantasy, deer are often magical creatures or shapeshifters. They can be spirit guides or familiars, often appearing to characters in dreams. The white stag and the brown doe are two often-used images in these settings.

In Romance novels, deer are often used as symbols of love and courtship. Deer-like descriptions are often used when describing characters, and hunting metaphors are often used to represent the romantic pursuit.

In Horror and Thriller novels, encounters with deer are often uncanny and frightening. They are used as harbingers of the supernatural, appear in dreams as a sign or portent of something to come, and often subvert traditional deer symbolism for dramatic effect.

In Literary Fiction, deer are often used as metaphors for the human experience. They can be used to represent character growth or epiphanies by exploring the relationship between mankind and nature.

How can you use deer symbolism in your own writing?

Deer can be used as the basis for a theme or motif in your work. They also offer tried-and-tested ways of incorporating visual storytelling into your imagery by using well-known associations.

Cultural considerations are good to consider in advance of incorporating symbolism. If you want to borrow from existing cultural traditions, then it’s essential to make sure you research and respect those cultural beliefs. Avoid appropriation, and be sure you strike the right balance between traditional symbolism and personal interpretation. There is nothing wrong with interpretation, but it is important to be respectful when borrowing from another person’s culture.

There are also new and interesting ways you can use your own experiences to develop your own symbolism. You can use deer as a symbol to explore themes of conservation and environmental protection. In Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel, she uses deer as a symbol of the return of nature in a post-human world. They can also be used to comment on urban expansion and habitat loss, and with enough research, you can use a scientific understanding of their behaviours to build your own mythology.

#writing tips#writeblr#creative writing#writers of tumblr#writing community#writing#writers#creative writers#writing inspiration#writerblr#writer#writerscommunity#writer stuff#ask novlr#writing advice#writing resources#writers on tumblr#writing stuff#writing asks

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who are the Mizrahim? History 101

Where do Jews come from and what is the difference between Sephardim and Mizrahim? Loolwa Khazzoom gives this succint explanation for the Jewish Virtual Library:

A Baghdadi Jewish family

Regardless of where Jews lived most recently, therefore, all Jews have roots in the Middle East and North Africa. Some communities, of course, have more recent ties to this region: Mizrahim and Sephardim, two distinct communities that are often confused with one another.

Mizrahim are Jews who never left the Middle East and North Africa since the beginnings of the Jewish people 4,000 years ago. In 586 B.C.E., the Babylonian Empire (ancient Iraq) conquered Yehudah (Judah), the southern region of ancient Israel.

Babylonians occupied the Land of Israel and exiled the Yehudim (Judeans, or Jews), as captives into Babylon. Some 50 years later, the Persian Empire (ancient Iran) conquered the Babylonian Empire and allowed the Jews to return home to the land of Israel. But, offered freedom under Persian rule and daunted by the task of rebuilding a society that lay in ruins, most Jews remained in Babylon. Over the next millennia, some Jews remained in today’s Iraq and Iran, and some migrated to neighboring lands in the region (including today’s Syria, Yemen, and Egypt), or emigrated to lands in Central and East Asia (including India, China, and Afghanistan).

Sephardim are among the descendants of the line of Jews who chose to return and rebuild Israel after the Persian Empire conquered the Babylonian Empire. About half a millennium later, the Roman Empireconquered ancient Israel for the second time, massacring most of the nation and taking the bulk of the remainder as slaves to Rome. Once the Roman Empire crumbled, descendants of these captives migrated throughout the European continent. Many settled in Spain (Sepharad) and Portugal, where they thrived until the Spanish Inquisition and Expulsion of 1492 and the Portuguese Inquisition and Expulsion shortly thereafter.

During these periods, Jews living in Christian countries faced discrimination and hardship. Some Jews who fled persecution in Europe settled throughout the Mediterranean regions of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire, as well as Central and South America. Sephardim who fled to Ottoman-ruled Middle Eastern and North African countries merged with the Mizrahim, whose families had been living in the region for thousands of years.

In the early 20th century, severe violence against Jews forced communities throughout the Middle Eastern region to flee once again, arriving as refugees predominantly in Israel, France, the United Kingdom, and the Americas. In Israel, Middle Eastern and North African Jews were the majority of the Jewish population for decades, with numbers as high as 70 percent of the Jewish population, until the mass Russian immigration of the 1990s. Mizrahi Jews are now half of the Jewish population in Israel.

Throughout the rest of the world, Mizrahi Jews have a strong presence in metropolitan areas — Paris, London, Montreal, Los Angeles, Brooklyn, and Mexico City. Mizrahim and Sephardim share more than common history from the past five centuries. Mizrahi and Sephardic religious leaders traditionally have stressed hesed (compassion) over humra (severity, or strictness), following a more lenient interpretation of Jewish law.

Despite such baseline commonalities, Middle Eastern and North African Mizrahim and Sephardim do retain distinct cultural traditions. Though Mizrahi and Sephardic prayer books are close in form and content, for example, they are not identical. Mizrahi prayers are usually sung in quarter tones, whereas Sephardic prayers have more of a Southern European feel. Traditionally, moreover, Sephardic prayers are often accompanied by a Western-style choir in the synagogue.

Mizrahim traditionally spoke Judeo-Arabic — a language blending Hebrew and a local Arabic dialect. While a number of Sephardim in the Middle East and North Africa learned and spoke this language, they also spoke Ladino–a blend of Hebrew and Spanish. Having had no history in Spain or Portugal, Mizrahim generally did not speak Ladino.

In certain areas, where the Sephardic immigration was weak, Sephardim assimilated into the predominantly Mizrahi communities, taking on all Mizrahi traditions and retaining just a hint of Sephardic heritage — such as Spanish-sounding names. In countries such as Morocco, however, Spanish and Portuguese Jews came in droves, and the Sephardic community set up its own synagogues and schools, remaining separate from the Mizrahi community.

Even within the Mizrahi and Sephardi communities, there were cultural differences from country to country. On Purim, Iraqi Jews had strolling musicians going from house to house and entertaining families (comparable to Christmas caroling), whereas Egyptian Jews closed off the Jewish quarter for a full-day festival (comparable to Mardi Gras). On Shabbat, Moroccan Jews prepared hamin (spicy meat stew), whereas Yemenite Jews prepared showeah (spicy roasted meat), among other foods.

Read article in full

The post Who are the Mizrahim? History 101 appeared first on Point of No Return. Read in browser »

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think 2 wizarding schools is enough for the Americas?

I made a post about Ilvermorny a little while ago, and one of my guesses is (based on the NA population I found) it would house over 54,000 students. Not bad, but even still I think one school for each continent isn't realistic. I could see Ilvermorny housing wizards/witches from the USA (and related territories), but not Mexico and Canada, due to their differing cultures. I'd probably make a wizarding school in Canada (I'd call it Couerderenne, or "Reindeer's Heart" in French; IDK if the name should be English or French; it's English name could be Reinheart), as well as a wizarding school in Mexico that accepted students from all over Central America (I'll call it Ventanagua, based on ventana de agua, or "water window," inspired by a Mexican belief I heard about that throwing a bucket of water out the window signifies throwing out the old year and welcoming in the new).

As for South America, I'd probably put a school in Colombia to represent Spanish-speaking wizarding communities in the continent (I'll call it Amarillaposa, based on Mariposa Amarilla, or yellow butterflies, a symbol of hope and peace in Colombia; perhaps too long a name), as well as keeping Castelobruxo in Brazil (kinda confused on why the name is Portuguese when it was founded before major Portuguese settlement), and since the other non-Spanish-speaking countries are smaller, I'd probably have them go to the schools of the colonial countries (ie Suriname students go to wizarding schools in the Netherlands, Guyana and Falkland Islands in the UK, French Guiana in France, etc.)

How do you think this would work out?

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big dinosaur news came out recently!

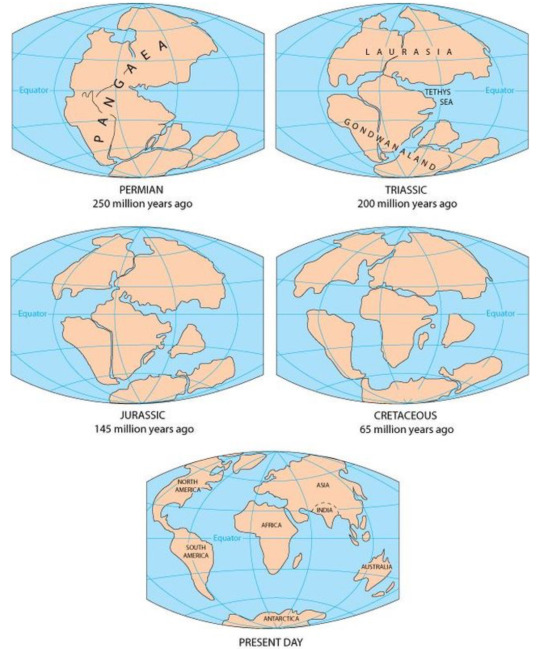

In January 1912, German geophysicist Alfred Wegener proposed an idea the scientific world thought was wack.

After scrutinizing similar-looking fossils of plants and animals on different land masses, he wondered if perhaps the continents had once been joined together before somehow separating into a new configuration.

His work was roundly scorned, and dismissed as "delirious ravings". Now, of course, the idea of continental drift is accepted as established science, with many different lines of evidence all pointing in the direction of Wegener's supercontinent, now known as Pangea.

Paleontologists have just identified another example that would have delighted the geophysicist; almost identical sets of dinosaur footprints have been found in Cameroon in Central Africa and in Brazil in South America, separated by a distance of more than 6,000 kilometers (about 3,700 miles).

These two locations define one of the last places dinosaurs could cross between the land masses freely before the continent of Gondwana – a fragment of Pangea – broke away completely, some 120 million years ago.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

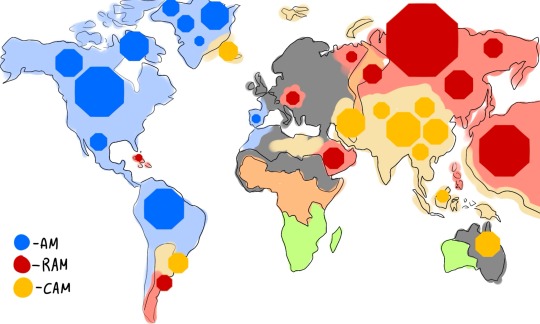

Look at the war

(can also maybe apply to the main timeline if you want)

(Very rough/sketch of the idea, mainly showing the places of the AM megastructures and honey-combs)—Takes place the height of the war—

During the war many countries fell/surrendered and got absorbed into the larger powers. Listing the different areas/territories by colour (all super brief here):

Blue — USA (new name not decided, give a suggestion if you want), was very quick to take over Canada and a large portion of South America. The AM megastructures tend to be the largest and most complex on their main land, even where the structure isn’t directly, large pipes and cables all throughout the country are visible. Due to this, a rapid industrialisation has happened and there are very few rural areas left. America’s population (like most of the other places) is also experiencing a decline. The air is extremely polluted and when close to the megastructures it’s said that the smell of burning and rotting flesh is very potent. The remaining population either remains constantly inside, moving around through tunnels, or permanently underground in the new lower cities. Notably radical religious organisations have become more frequent due to the war, mostly due to people supposedly disappearing in their sleep without a trace.

Red— Russia has the largest Megastructure, however due to this, it faces the most attacks. One structure notably, was built small in the ocean yet over time it grew and built itself and the area around it up, creating a false floating continent. However it is due to its creation that a large population of sea life has been erratic and floods that wiped out many coastal cities and communities. Much like America very few rural areas remain, and due to extreme climate change caused by the war, the area faces even harsher and year long winters that have spread to the rest of Europe.

Yellow— China. The AMs (CAM) are very close together here and have been designed in such a way that people are able to live within them. Due to their general closeness to each other they tend to function better in self-protection than the other AMs. It is constantly building, more and more structures as opposed to constantly developing a single one. Within China a few rural and farming communities have been preserved, however due to such a fact, those areas in particular have become targets—especially to RAM.

Orange— These are actively hostile territories (well everywhere is hostile), but life is still found. Camps are usually found scattered, yet still alined to one of the powers. Mostly these are unclaimed territories that are being fighted for.

Grey— Dead zones. Areas so destroyed and ruined by the war that they near uninhabitable and been stripped dry of resources. This is where most of the fighting has happened, in what used to be Central Europe. Majority of the people who were there are dead or have been displaced (mostly in Russia and China, with the luckier ones making it to the Common Wealth of Southern Africa) The remaining people are scattered and can be found within underground shelters. These shelters are horrific places, with few supplies, little food, and constant sickness. The people are actively hunted by all the AMs. Notably Naomi is from one of these bunkers, having been forced into one at the age of two. Nimdok too (when he was alive alreast).

Green— The commonwealth of Southern Africa (previously the African Commonwealth) A bit after the war began (post 1994) many African nations merged diplomatically in order to better conserve resources better and to be a better neutral force. However as the war progressed more and more of the continent was over taken. However in the process the remaining state has become a power in of its own. Creating a defences that work efficiently to keep the AMs out. It was chosen to sanction themselves from the world and the war. Truly wanting no part in it. Eventually Australia did join, before half was taken, but the remainder acts as a port and outlook. This is one of the few areas were “regular” human society is still found, with there being heavy laws and propaganda meant to block out information of the war. Previously they had been very open to refugees, however they would begin to refuse them as it had opened opportunities to the AMs. Ellen and Evan are both from here. Gorrister also hides within it, however he smuggles himself in and out constantly, as being a member of the peace core, he has work to do all over the remaining world.

Where everyone is from including the survivors of the og and love au:

—Gorrister from England however he fled to America, then to COSA, and eventually to Russia where he would help develop the BE virus.

-Ted, Tiffany, and Gloria are all from the USA, however Ted is an average citizen, Tiffany is a member of one of the religious groups, and Gloria is a high ranking military commander, government official and one of the reasons of AM’s existence.

-(idk where Benny is from, can’t decide lol, same with Becky)

-Nimdok and Naomi are from different parts of Europe but both find themselves in the survival bunkers

-Ellen and Evan (being siblings) are from COSA, being born where Zimbabwe used to be. Evan however would go onto explore the rest of the state, mainly in the area where South Africa had once been. Ellen would stay closer to home. (Reason as to why is that in the original and audio drama, Ellen frequently refers to life before AM, and rarely mentions the war, which could mean she either doesn’t think about it or knows very little of it)

(There’s like no world lore in the og and whilst that is kinda the point, I just wanted to build on it a little. Will be posting some concept art for this stuff soon. As usual if you have ideas or suggestions please share)

#i have no mouth and i must scream#ihnmaims#am ihnmaims#ted ihnmaims#ihnmaimsloveau#alternate reality#ellen ihnmaims#harlan ellison#gorrister ihnmaims#ihnmaims am#ihnmaims ted#ihnmaims game

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

DEVIL MONKEYS- VIRGINIA

Though South America, Central America and southern Mexico have a great diversity of primates, northern North America has none aside from humans. This is ironic given that the earliest known primate- a small, squirrel-like creature called Purgatorius- evolved on this continent. Descendants of Purgatorius and its relatives diversified into several lineages of tarsier- and lemur-like forms that inhabited North America during the warm Eocene epoch before supposedly dying out as the land grew cooler and grasslands became more abundant.

A fossil find in 1960s altered this view when molars from a lemur-like creature dubbed Ekgmowechasala (Sioux for “Little Cat Man”) were unearthed on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. This animal lived in the Oligocene, millions of years after other primates were thought to have died out, proving that at least a few of these lines had continued. Though no younger North American primate fossils have been found since, what if descendants of Ekgmowechasala survived into the present day?

In 1959 a couple by the name of Boyd were driving home near Saltville, Virginia when a strange, monkey-like beast attacked their car. They described it as having light “taffy-colored” fur with a white belly, and powerful, muscular legs. Other people in the Saltville area reported seeing a similar creature around the same time.

Then in the 1990s a woman driving on a dark Virginia backroad saw a creature run in front of her car that she described as black and sleek with a long tail, pointy ears, a short-snouted face, a man-like torso, and powerful hind legs. Though the earlier Boyd cryptid bears little resemblance to this animal- and may in fact have been a different species- both incidents have been conflated in pop culture as encounters with what have come to be called devil monkeys.

While the Virginia encounters are the most well-known sightings, devil monkeys have been seen throughout North America. Coweta County, Georgia, for example, is haunted by the Belt Road Booger, a simian creature with a “flat, beaver-like tail covered in hair”. Run-ins with the Booger began in the 1970s, many of them now believed to have been hoaxes by pranksters dressed in gorilla costumes. But other encounters have not yet been fully explained. The Belt Road Booger has become such a local sensation that a taxidermist in Newnan, Georgia even made a fake “Booger” head out of a white-tailed deer’s posterior as a decoration for a friend’s hardware store.

There is also possible photographic evidence of a devil monkey. In 1996 photos surfaced online of a strange, furry, baboon-like carcass lying along the curb of a Louisiana highway. Dubbed the Deridder Roadkill, the body bears a distinct resemblance to descriptions of these cryptids with its long snout, bushy-haired body, and ape-like feet. While some have suggested the carcass was a devil monkey, others have proposed that it could be a rougarou, dogman, or even a chupacabra. More mundane suggestions include a large Pomeranian dog, or even a prop. However, as so often happens in these cases, the body disappeared before samples could be taken, so its identity could not be proved definitively.

Devil monkeys are often said to have powerful kangaroo-like hind legs that allow them to jump huge distances. This feature has led some cryptozoologists to wonder if widely reported “phantom kangaroos” sighted throughout the US and Canada might actually be these animals.

While stories of large non-human North American primates like sasquatch and skunk apes are abundant in folklore and cryptozoology, no fossil evidence for these creatures has been found. Thus if they are real, one could argue that they likely migrated to this continent late in geological history along the same routes that humans used. Devil monkeys, on the other hand, may represent a species of home-grown North American primate possibly descended from Ekgmowechasala or similar animals.

REFERENCES

Eons. (20, November 12). What happened to primates in North America? [Video]. PBS.org. https://www.pbs.org/video/the-first-and-last-north-american-primates-dztigm/#:~:text=Why%20don't%20we%20have,and%20eventually%20they%20all%20disappeared.

Gilly, Steve. (2018, April 20). The Devil Monkey. MountainLore. https://mountainlore.net/2018/04/20/the-devil-monkey/

Grundhauser, Eric. (2016, December 22). Does America have a secret kangaroo population? Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/does-america-have-a-secret-kangaroo-population

Leftwich, Rebecca. (2023, October 30). Who put the “boo” in the Belt Road Booger? The Newnan Times-Herald. https://www.times-herald.com/news/who-put-the-boo-in-the-belt-road-booger/article_ee9d689e-770f-11ee-a003-8bb851ca9cb4.html

Lynch, Brendan M. (2023, November 6). Fossils tell tale of last primate to inhabit North America before humans. University of Kansas. https://news.ku.edu/2023/11/06/fossil-evidence-tells-tale-last-primate-inhabit-north-america-humans#:~:text=The%20first%20primates%20came%20to,about%2034%20million%20years%20ago.

Morphy, Rob. (2010, January 13). Deridder Roadkill: (Louisiana, USA). Cryptopia. https://www.cryptopia.us/site/2010/01/deridder-roadkill-louisiana-usa/

Morphy, Rob. (2010, December 6). Devil monkeys: (North America). Cryptopia. https://www.cryptopia.us/site/2010/12/devil-monkeys-north-america/

Spooky Appalachia. (2023, April 26). The story of the Virginia devil monkey. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nsv-mBSEX74

Taylor, Jr. L. B. (2012). Monsters of Virginia. Stackpole Books.

38 notes

·

View notes